Strategies to Enhance Yield of Wet-Synthesized Hydroxyapatite Nanocrystals and Consequences for Drug-Release Kinetics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

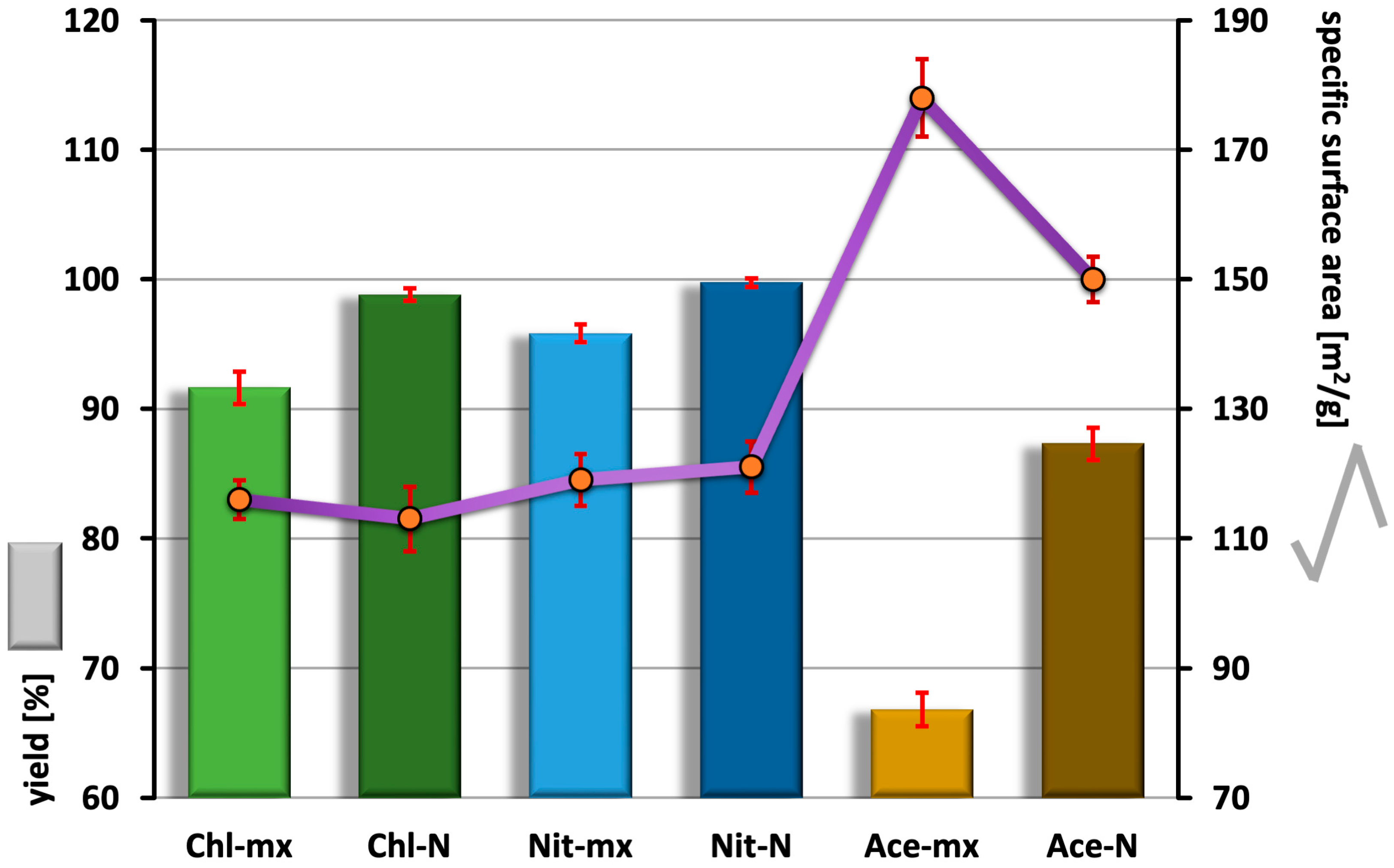

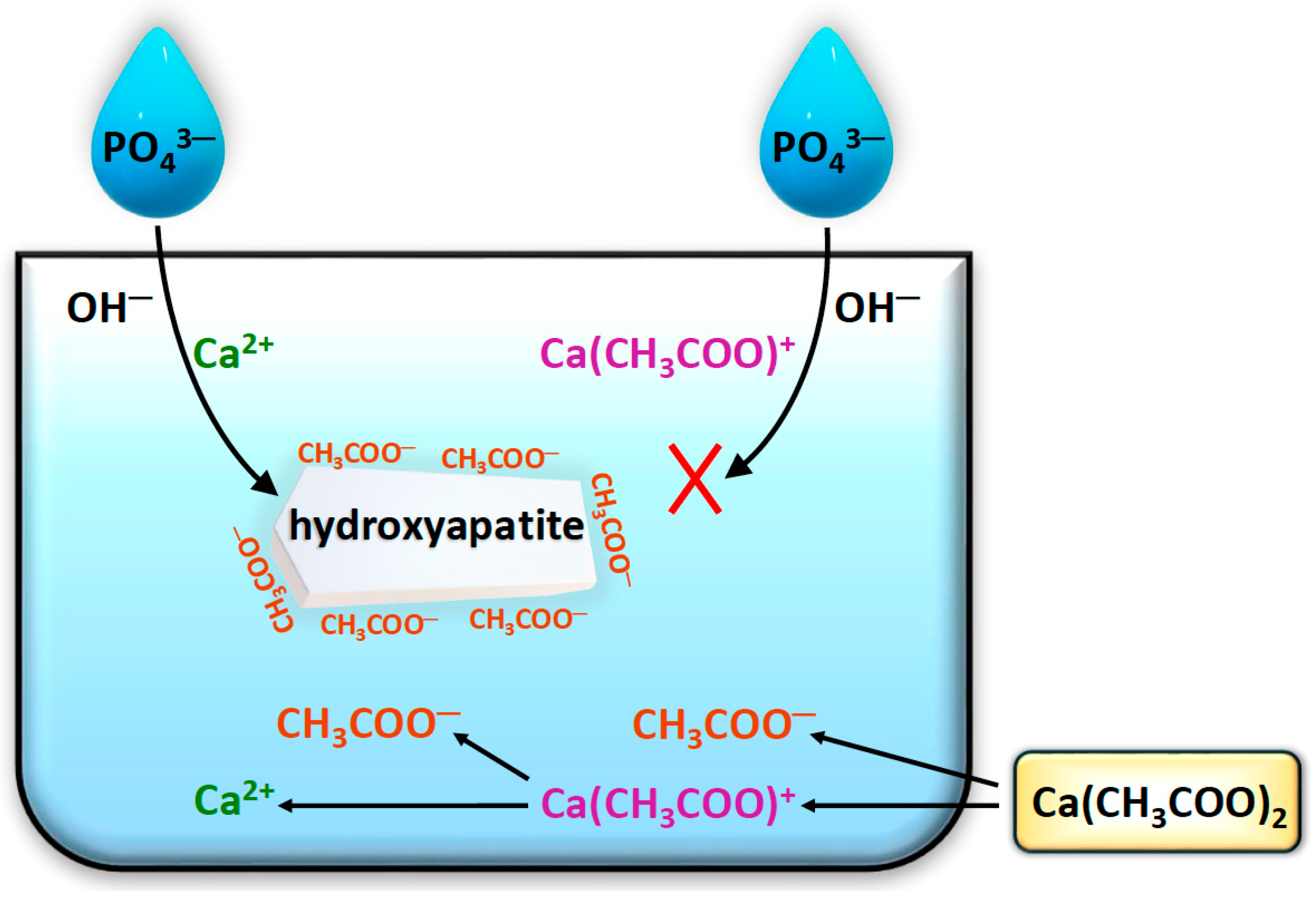

2.1. Synthesis Efficiency and Specific Surface Area

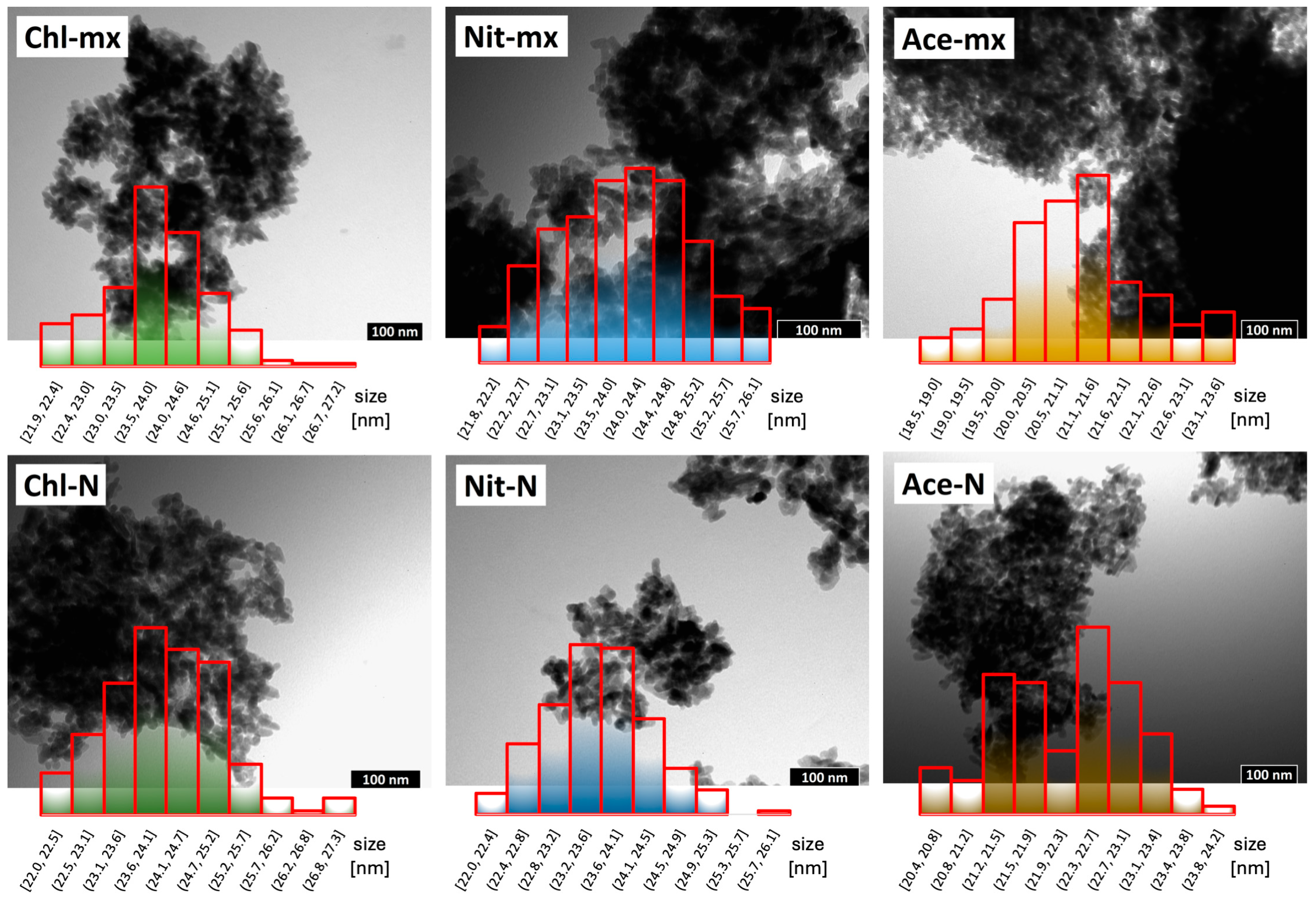

2.2. TEM Observations

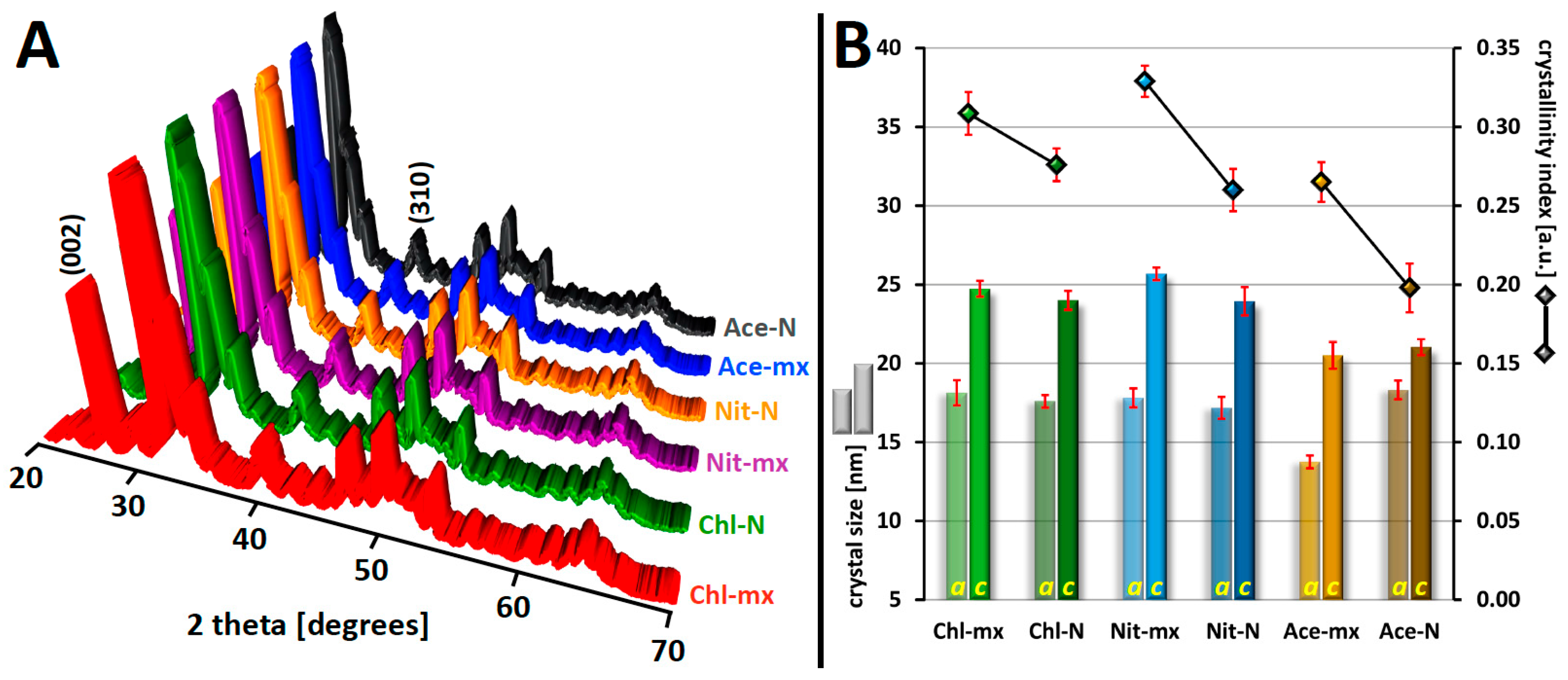

2.3. PXRD Studies: Crystallinity and Crystal Size

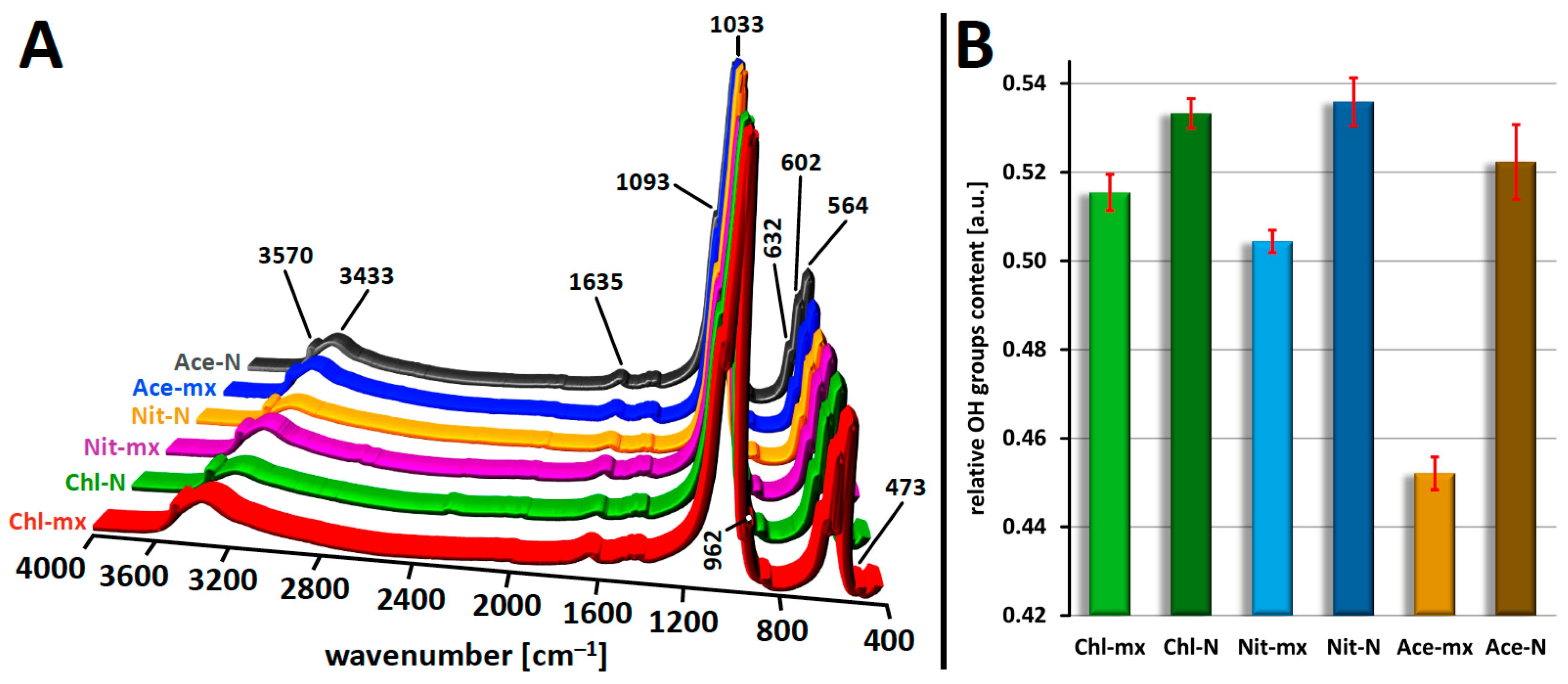

2.4. FT-IR Analysis

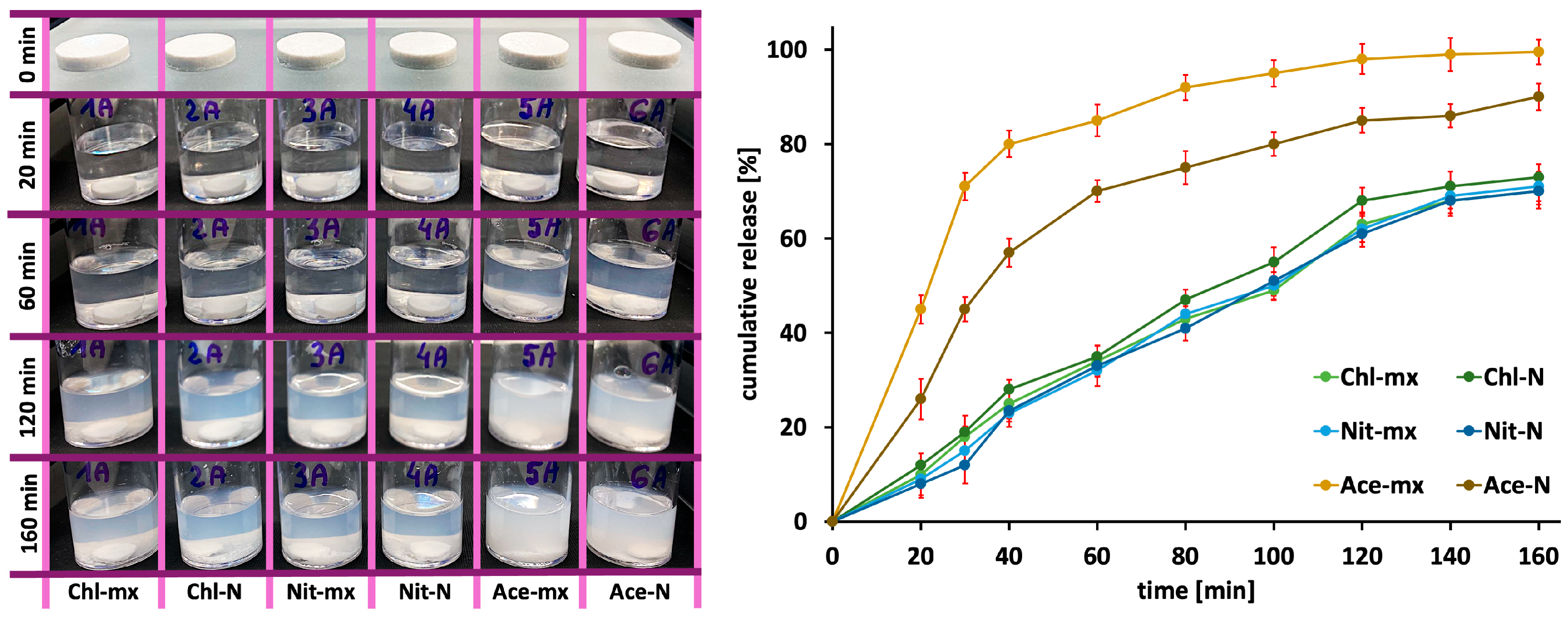

2.5. Drug Release Profiles

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis Procedure

3.2. Physicochemical Characteristics of Hydroxyapatites

3.3. Tablet Preparation and In Vitro Drug Release Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HA | hydroxyapatite |

| Chl | chloride (as calcium source) |

| Nit | nitrate (as calcium source) |

| Ace | acetate (as calcium source) |

| -mx | dynamic maturation type |

| -N | static maturation type |

| SSA | specific surface area |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller isotherm |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| PXRD | powder X-ray diffraction |

| FT-IR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| PBS | phosphate buffered saline |

References

- Kareem, R.O.; Bulut, N.; Kaygili, O. Hydroxyapatite biomaterials: A comprehensive review of their properties, structures, medical applications, and fabrication methods. J. Chem. Rev. 2024, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uskoković, V. Ion-doped hydroxyapatite: An impasse or the road to follow? Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 11443–11465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evis, Z.; Webster, T.J. Nanosize hydroxyapatite: Doping with various ions. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2011, 110, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Biphasic, triphasic and multiphasic calcium orthophosphates. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilen, R.W.N.; Richter, P.W. The thermal stability of hydroxyapatite in biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.M.; Liu, S.M.; Ko, C.L.; Chen, W.C. Advances of hydroxyapatite hybrid organic composite used as drug or protein carriers for biomedical applications: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Ma, G.; Chen, A.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, S.; Shi, Y. Additive manufacturing of hydroxyapatite and its composite materials: A review. J. Micromech. Mol. Phys. 2020, 5, 2030002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadavenkatesan, T.; Vinayagam, R.; Pai, S.; Brindhadevi, K.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Selvaraj, R. Synthesis, biological and environmental applications of hydroxyapatite and its composites with organic and inorganic coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 151, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Ruys, A.J.; Swain, M.V.; Milthorpe, B.K.; Sorrell, C.C. Hydroxyapatite-coated metals: Interfacial reactions during sintering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; He, J.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Nie, S. Fire-retardant hydroxyapatite/cellulosic triboelectric materials for energy harvesting and sensing at extreme conditions. Nano Energy 2023, 117, 108851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.Q.; Zhu, Y.J.; Chen, F. Highly flexible and nonflammable inorganic hydroxyapatite paper. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazdis, R.I.; Fierascu, I.; Avramescu, S.M.; Fierascu, R.C. Recent progress in the application of hydroxyapatite for the adsorption of heavy metals from water matrices. Materials 2021, 14, 6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.; Kini, S.M.; Selvaraj, R.; Pugazhendhi, A. A review on the synthesis of hydroxyapatite, its composites and adsorptive removal of pollutants from wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 38, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easter, Q.T. Biopolymer hydroxyapatite composite materials: Adding fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy to the characterization toolkit. Nano Sel. 2022, 3, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neacsu, I.A.; Stoica, A.E.; Vasile, B.S.; Andronescu, E. Luminescent hydroxyapatite doped with rare earth elements for biomedical applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, H.; Hwang, J.; Yeo, W.; Bang, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, T.Y.; Choi, J.S.; Han, J.W. Design strategies for hydroxyapatite-based materials to enhance their catalytic performance and applicability. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2204938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fihri, A.; Len, C.; Varma, R.S.; Solhy, A. Hydroxyapatite: A review of syntheses, structure and applications in heterogeneous catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 347, 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiume, E.; Magnaterra, G.; Rahdar, A.; Verne, E.; Baino, F. Hydroxyapatite for biomedical applications: A short overview. Ceramics 2021, 4, 542–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, D.; Vallet-Regi, M. Substituted hydroxyapatite coatings of bone implants. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 1781–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, B.S.F.; Almeida, T.S.C.; Carvalho, R.M.; Machado, C.J.; Bravo, L.G.; Elias, M.C. Dermal thickness increase and aesthetic improvement with hybrid product combining hyaluronic acid and calcium hydroxyapatite: A clinical and sonographic analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2023, 11, e5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Ochoa, S.; Ortega-Lara, W.; Guerrero-Beltran, C.E. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in drug delivery: Physicochemistry and applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu’ad, N.A.S.M.; Haq, R.H.A.; Noh, H.M.; Abdullah, H.Z.; Idris, M.I.; Lee, T.C. Synthesis method of hydroxyapatite: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 29, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Peng, W.; Xu, X.; Su, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Song, G.; Zhou, C.; et al. Synthesis and application of nanometer hydroxyapatite in biomedicine. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 2154–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.F.; Granadeiro, C.C.; Silva, M.A.; Hoyos, M.; Silva, R.; Vieira, T. An investigation of the synthesis parameters of the reaction of hydroxyapatite precipitation in aqueous media. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2008, 6, A103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.H.; de Oliveira, M.; de Freitas Souza, L.P.; Mansur, H.S.; Vasconcelos, W.L. Synthesis control and characterization of hydroxyapatite prepared by wet precipitation process. Mater. Res. 2004, 7, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelten, A.; Yilmaz, S. Various parameters affecting the synthesis of the hydroxyapatite powders by the wet chemical precipitation technique. Mater. Today Proc. 2016, 3, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronova, T.V.; Korneichuk, S.A.; Putlyaev, V.I.; Boitsova, O.V. Ceramics made from calcium hydroxyapatite synthesized from calcium acetate and potassium hydrophosphate. Glass Ceram. 2008, 65, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronova, T.V.; Shiryaev, M.A.; Putlyaev, V.I.; Murashov, V.A.; Protsenko, P.V. Ceramics based on hydroxyapatite synthesized from calcium chloride and potassium hydrophosphate. Glass Ceram. 2009, 66, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, M.; Safronova, T.; Putlyaev, V. Calcium phosphate powders synthesized from calcium chloride and potassium hydrophosphate. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2010, 101, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, S.; Altınsoy, İ.; ÇelebiEfe, G.; Ipek, M.; Özacar, M.; Bindal, C. Microwave–assisted biomimetic synthesis of hydroxyapatite using different sources of calcium. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 76, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qasas, N.S.; Rohani, S. Synthesis of pure hydroxyapatite and the effect of synthesis conditions on its yield, crystallinity, morphology and mean particle size. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2005, 40, 3187–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, A.; Yoruc, A.B.H.; Erdogan, D.C.; Dogan, M. Effect of different calcium precursors on biomimetic hydroxyapatite powder properties. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2012, 121, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepuk, A.A.; Veresov, A.G.; Putlyaev, V.I.; Tret’yakov, Y.D. The influence of NO3−, CH3COO−, and Cl− ions on the morphology of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals. Dokl. Phys. Chem. 2007, 412, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, U.V.; Rajeswari, S. Influence of calcium precursors on the morphology and crystallinity of sol–gel-derived hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. J. Cryst. Growth 2008, 310, 4601–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, R.; Mustafa, Z.; Loon, C.W.; Noor, A.F.M. Effect of calcium precursors and pH on the precipitation of carbonated hydroxyapatite. Procedia Chem. 2016, 19, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarabharathi, L.; Ponnamma, D.; Parangusan, H.; Chinnaswamy, M.; Al-Maadeed, M.A.A. Effect of anions on the structural, morphological and dielectric properties of hydrothermally synthesized hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Han, Y.; Luo, J.; Huang, M.; Zhang, B.W.; Hou, Y. Large-scale and fast synthesis of nanohydroxyapatite powder by a microwave-hydrothermal method. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13623–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourbin, M.; Brouillet, F.; Galey, B.; Rouquet, N.; Gras, P.; Abi Chebel, N.; Grossin, D.; Frances, C. Agglomeration of stoichiometric hydroxyapatite: Impact on particle size distribution and purity in the precipitation and maturation steps. Powder Technol. 2020, 360, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamieniak, J.; Bernalte, E.; Foster, C.W.; Doyle, A.M.; Kelly, P.J.; Banks, C.E. High yield synthesis of hydroxyapatite (HAP) and palladium doped HAP via a wet chemical synthetic route. Catalysts 2016, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D.N. Interaction of some coupling agents and organic compounds with hydroxyapatite: Hydrogen bonding, adsorption and adhesion. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1994, 8, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolenko, M.V.; Vasylenko, K.V.; Myrhorodska, V.D.; Kostyniuk, A.; Likozar, B. Synthesis of calcium orthophosphates by chemical precipitation in aqueous solutions: The effect of the acidity, Ca/P molar ratio, and temperature on the phase composition and solubility of precipitates. Processes 2020, 8, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukowski, S.; Sztelmach, K. The influence of single and binary mixtures of collagen amino acids on the structure of synthetic calcium hydroxyapatite as a nanobiomaterial. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23769–23777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajchel, L.; Kowalska, V.; Smolen, D.; Kedzierska, A.; Pietrzykowska, E.; Lojkowski, W.; Kolodziejski, W. Comprehensive structural studies of ultra-fine nanocrystalline calcium hydroxyapatite using MAS NMR and FT-IR spectroscopic methods. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 4818–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.E.; Awonusi, A.; Morris, M.D.; Kohn, D.H.; Tecklenburg, M.M.J.; Beck, L.W. Highly ordered interstitial water observed in bone by nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005, 20, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, Y.; Guo, Y.; Feng, X.; Wang, M.; Li, P.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Jiang, T. Are different crystallinity-index-calculating methods of hydroxyapatite efficient and consistent? New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 5723–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, M.; Palevicius, A.; Monshi, A.; Nasiri, S.; Vilkauskas, A.; Janusas, G. Comparing methods for calculating nano crystal size of natural hydroxyapatite using X-ray diffraction. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paarakh, M.P.; Jose, P.A.; Setty, C.; Christoper, G.V.P. Release kinetics—Concepts and applications. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Technol. 2018, 8, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucillo, P. Drug carriers: A review on the most used mathematical models for drug release. Processes 2022, 10, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code | Theoretical Ca/P Molar Ratio | Experimental Ca/P Molar Ratio a | Crystal Size [nm] a,b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chl-mx | 1.67 | 1.55 ± 0.04 | 23.9 ± 0.9 |

| Chl-N | 1.67 | 1.55 ± 0.05 | 24.1 ± 1.1 |

| Nit-mx | 1.67 | 1.61 ± 0.05 | 23.9 ± 1.0 |

| Nit-N | 1.67 | 1.58 ± 0.06 | 23.6 ± 0.7 |

| Ace-mx | 1.67 | 1.56 ± 0.04 | 21.5 ± 1.2 |

| Ace-N | 1.67 | 1.60 ± 0.05 | 22.2 ± 0.8 |

| Sample Code | Zero-Order Kinetics | First-Order Kinetics | Higuchi Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | R2 | R2 | K [mg/min0.5] | |

| Chl-mx | 0.9794 | 0.9872 | 0.9473 | 6.2089 |

| Chl-N | 0.9718 | 0.9862 | 0.9514 | 6.5459 |

| Nit-mx | 0.9844 | 0.9891 | 0.9360 | 6.3761 |

| Nit-N | 0.9813 | 0.9896 | 0.9298 | 6.3505 |

| Ace-mx | 0.6472 | 0.9912 | 0.8793 | 7.4598 |

| Ace-N | 0.8078 | 0.9709 | 0.9538 | 7.6634 |

| Sample Code | Calcium Source | Maturation Type |

|---|---|---|

| Chl-mx | chloride | dynamic (with mixing) |

| Chl-N | chloride | static (without mixing) |

| Nit-mx | nitrate | dynamic |

| Nit-N | nitrate | static |

| Ace-mx | acetate | dynamic |

| Ace-N | acetate | static |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krukowski, S.; Byra, N.; Adamczyk, A.; Biały, J. Strategies to Enhance Yield of Wet-Synthesized Hydroxyapatite Nanocrystals and Consequences for Drug-Release Kinetics. Materials 2025, 18, 5424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235424

Krukowski S, Byra N, Adamczyk A, Biały J. Strategies to Enhance Yield of Wet-Synthesized Hydroxyapatite Nanocrystals and Consequences for Drug-Release Kinetics. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235424

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrukowski, Sylwester, Natalia Byra, Aleksandra Adamczyk, and Jakub Biały. 2025. "Strategies to Enhance Yield of Wet-Synthesized Hydroxyapatite Nanocrystals and Consequences for Drug-Release Kinetics" Materials 18, no. 23: 5424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235424

APA StyleKrukowski, S., Byra, N., Adamczyk, A., & Biały, J. (2025). Strategies to Enhance Yield of Wet-Synthesized Hydroxyapatite Nanocrystals and Consequences for Drug-Release Kinetics. Materials, 18(23), 5424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235424