The Use of Metal Oxides (Al2O3 and ZrO2) and Supports (Glass and Kaolin) to Enhance DBD Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Conversion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

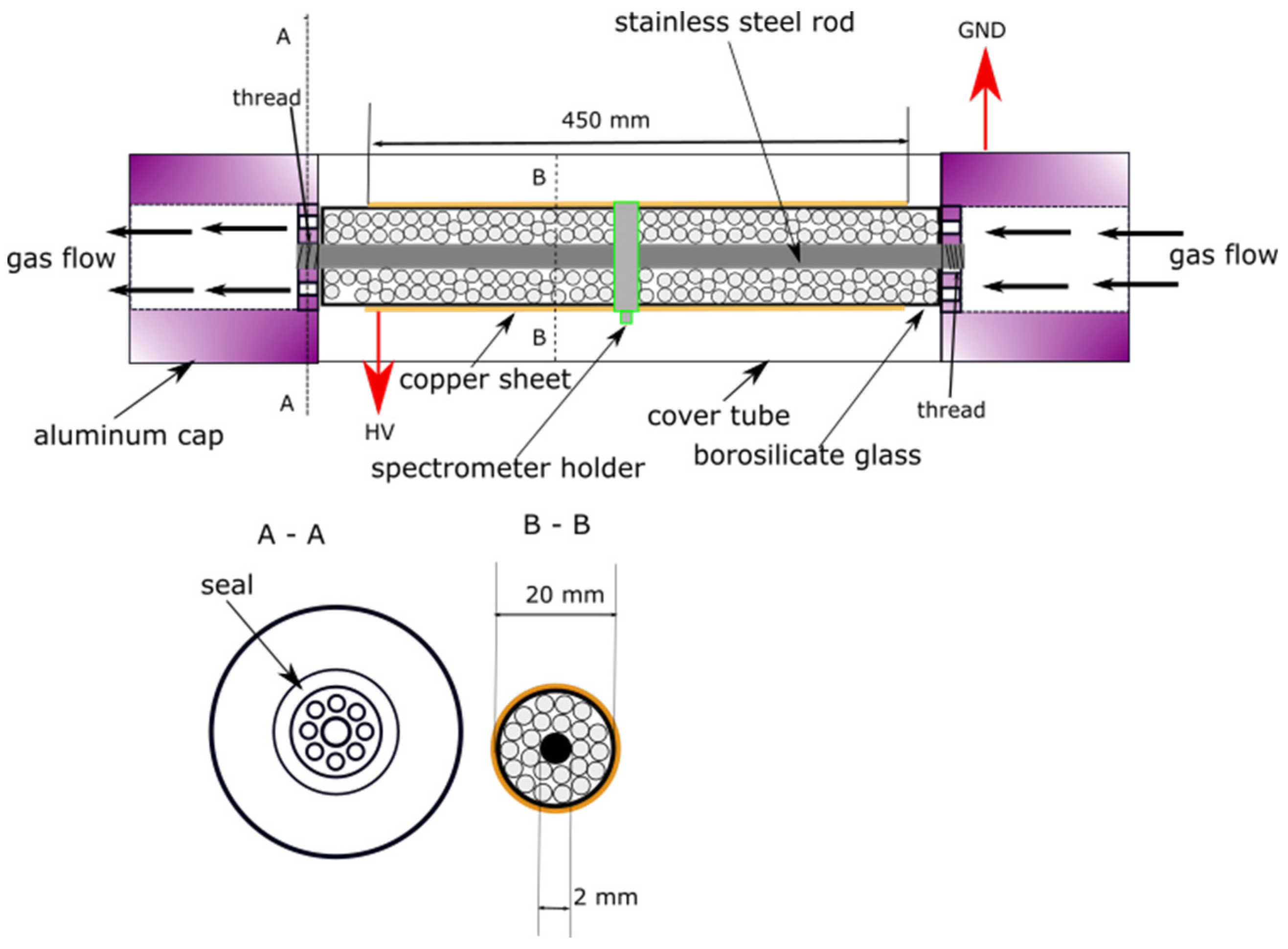

2.2.1. Characteristics of Non-Thermal Plasma Packed-Bed Reactor with Dielectric Barrier Discharge

2.2.2. Production of Kaolin Pellets

2.2.3. Surface Area and Porosity Characterization of the Kaolin Pellets

2.2.4. Chemical Composition Determination of the Packing Beads

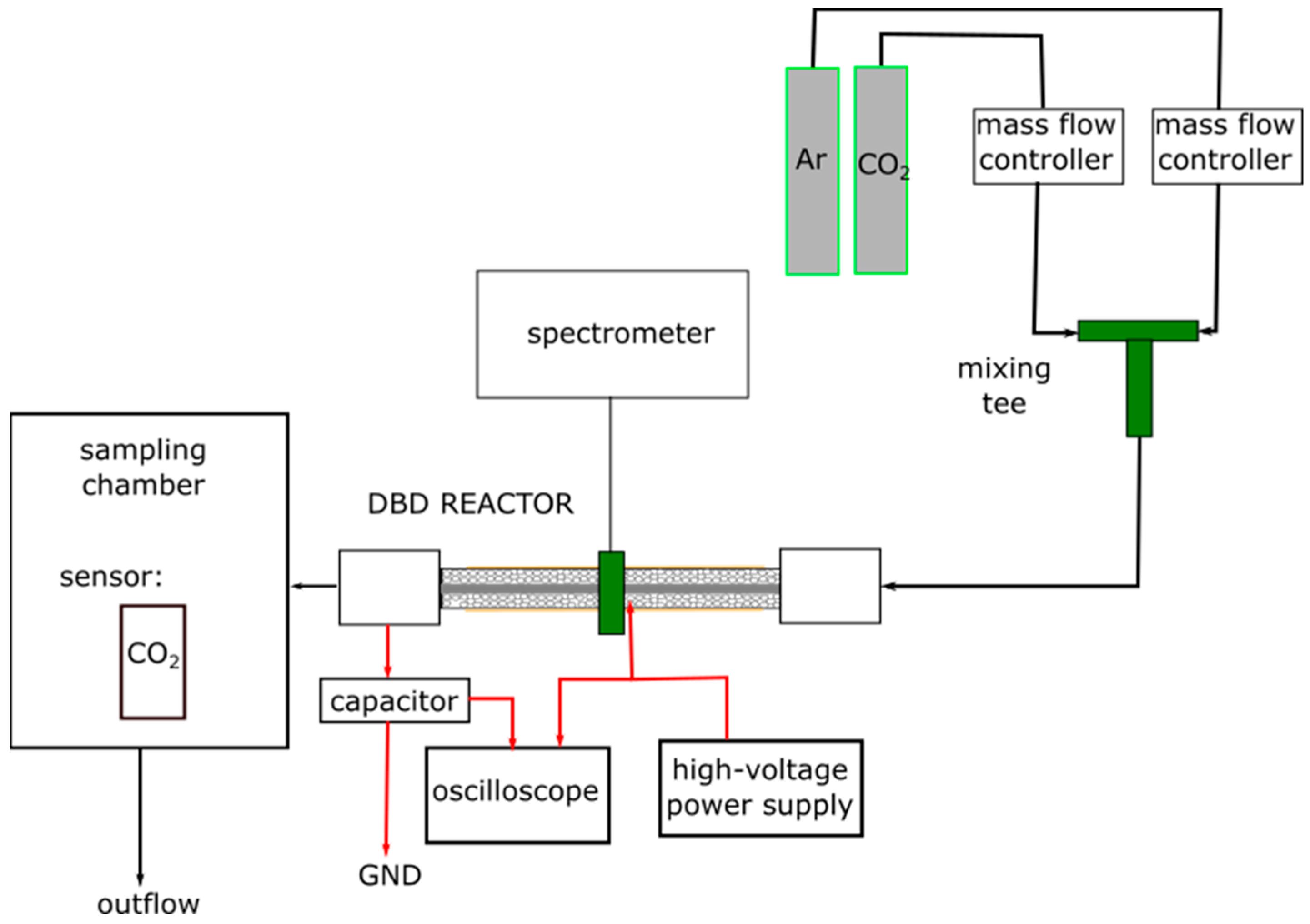

2.2.5. Experimental Setup and Procedure

2.2.6. Replicate Measurement Protocol

2.2.7. Electrical Characterization of the Discharge

2.2.8. Imaging of Discharge Propagation

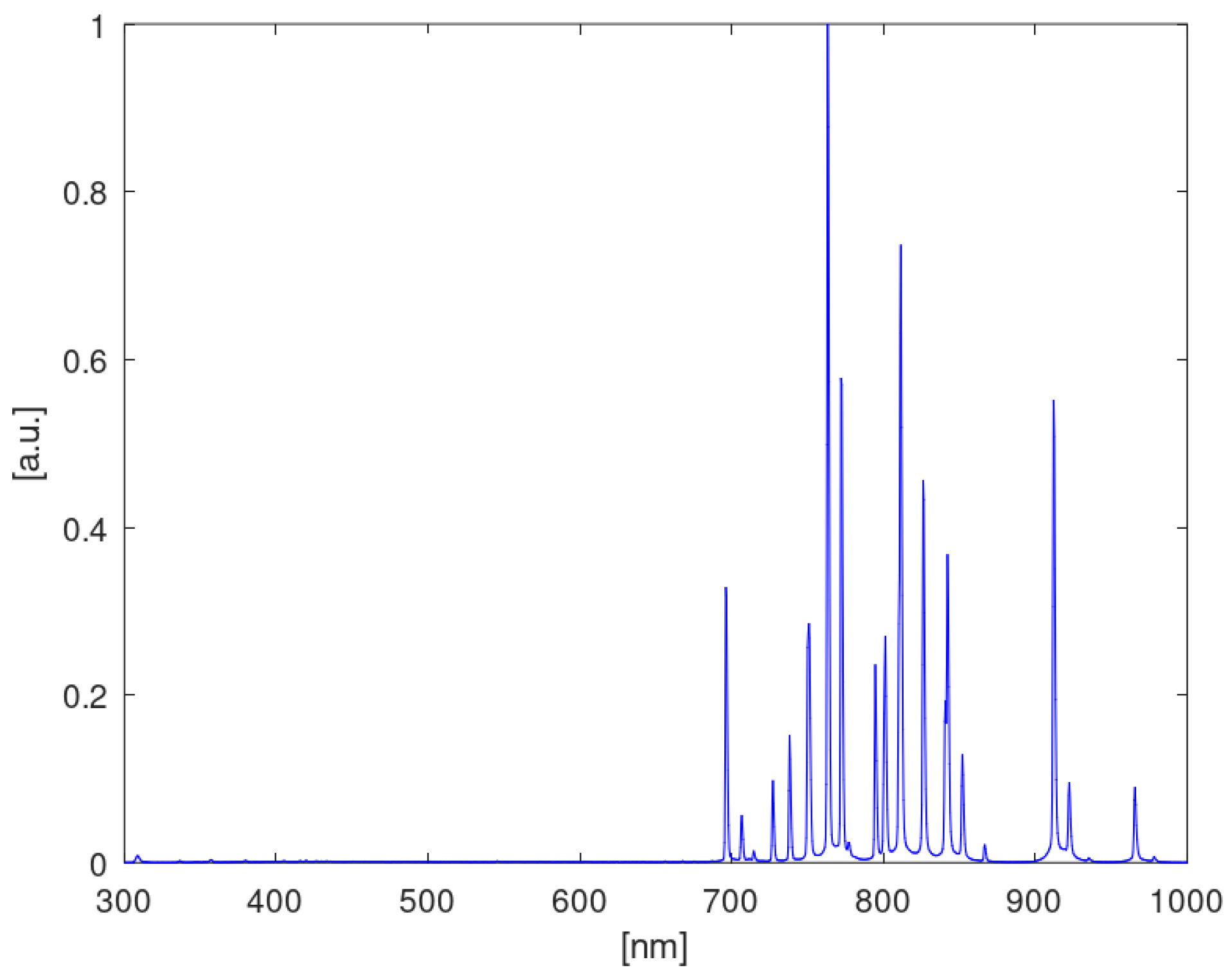

2.2.9. Spectroscopic Analysis

2.2.10. Conversion and Energy Efficiency Calculations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Specific Surface Area and Porosity Characteristics of the Kaolin Pellets

3.2. Chemical Composition Analysis of the Packing Beads

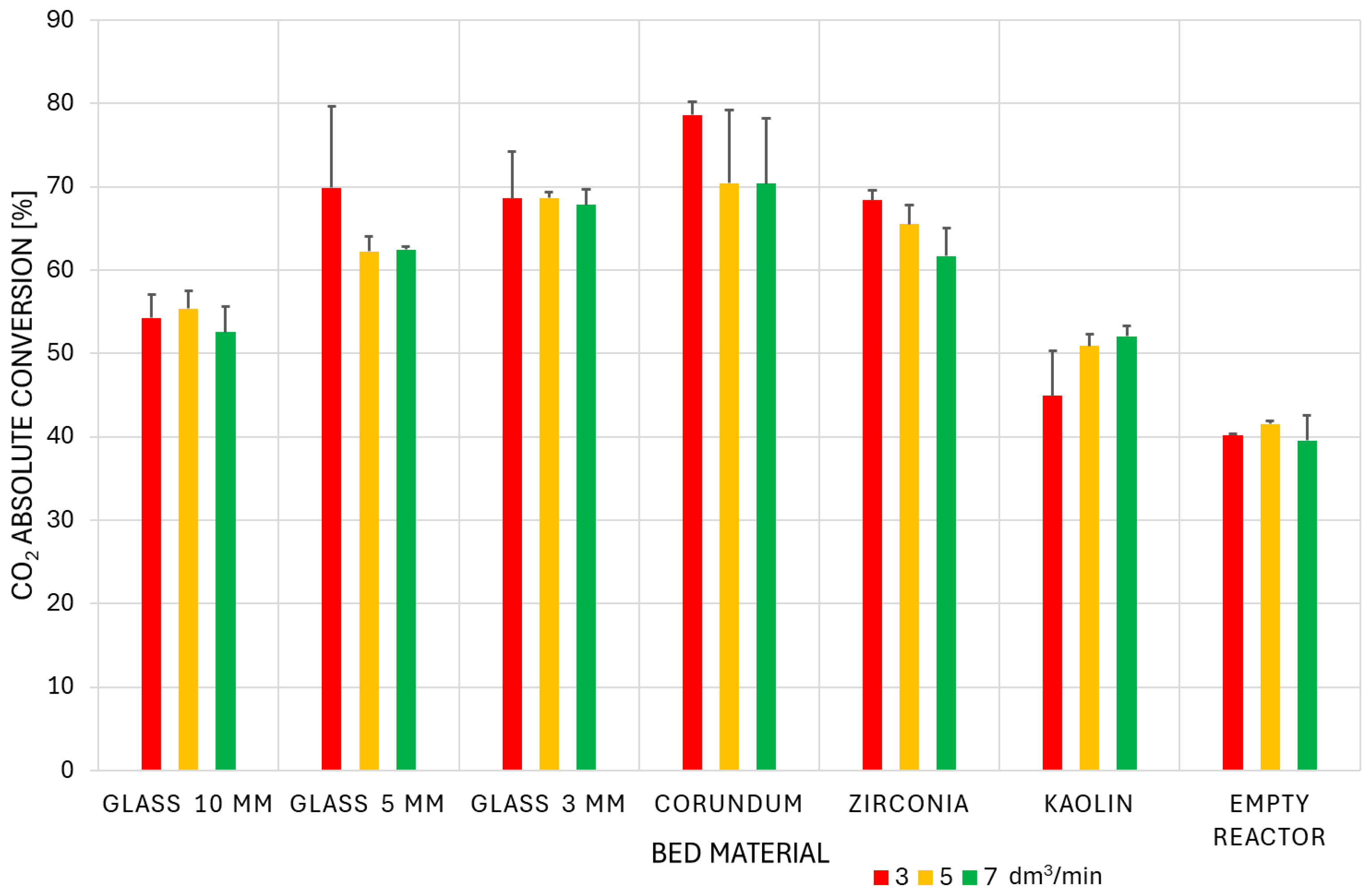

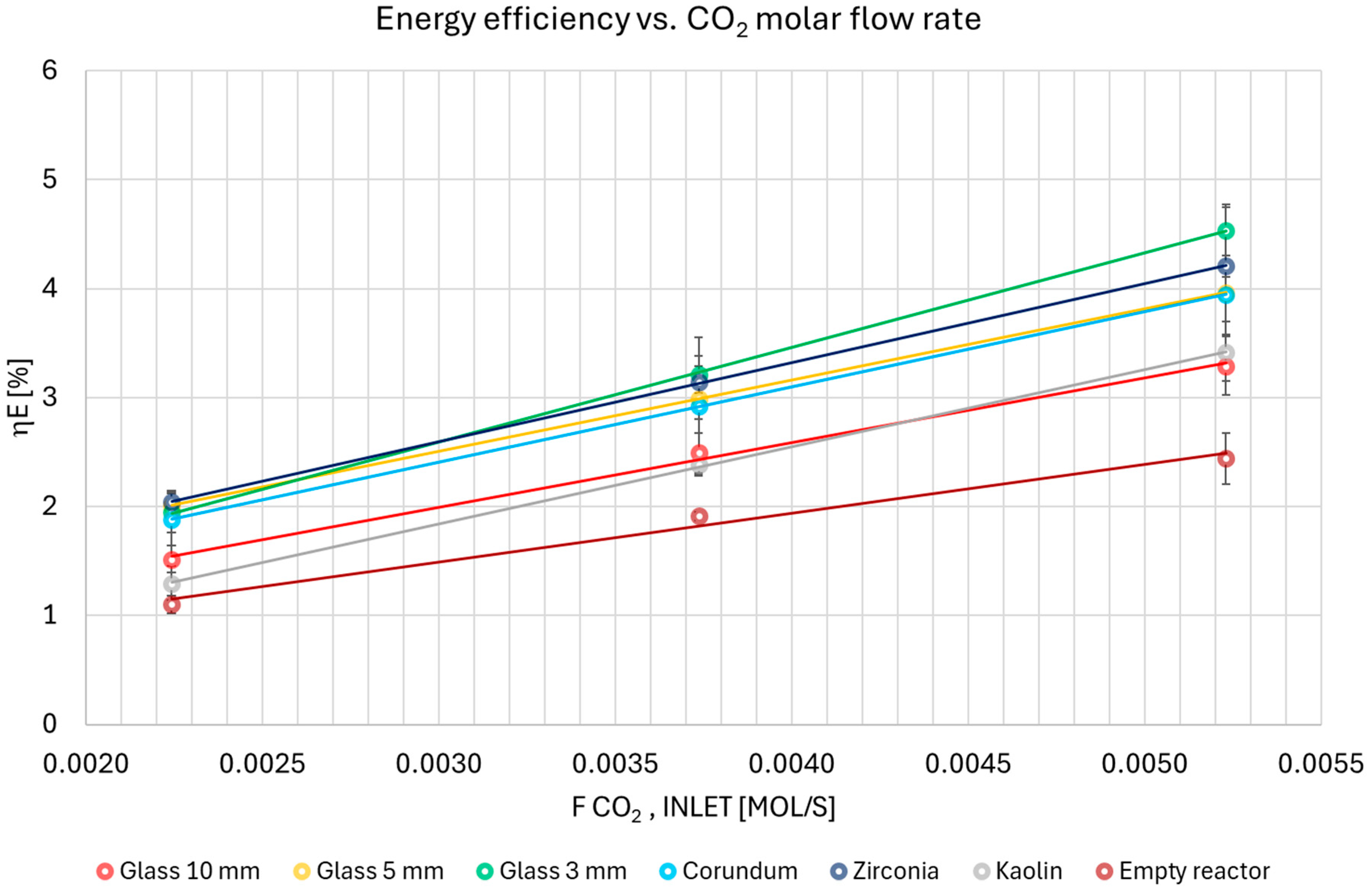

3.3. Conversion and Energy Efficiency Analysis

- For 10 mm glass, 5 mm glass, zirconia, and corundum, conversion efficiency increased. This result is consistent with the expected outcome of supplying more energy to the process.

- For the empty reactor and 3 mm glass, conversion efficiency remained constant with increasing SEI. A reasonable explanation for the constant conversion efficiency is that a mass transfer limitation becomes the dominant factor. While the energy input increases, the conversion plateaus because the rate of CO2 molecules reaching the plasma-activated sites does not increase proportionally.

- For kaolin, conversion efficiency decreased with increasing the value of the SEI parameter. This may also be due to a different discharge character in the inter-particle spaces, which could be influenced by the higher flow rate.

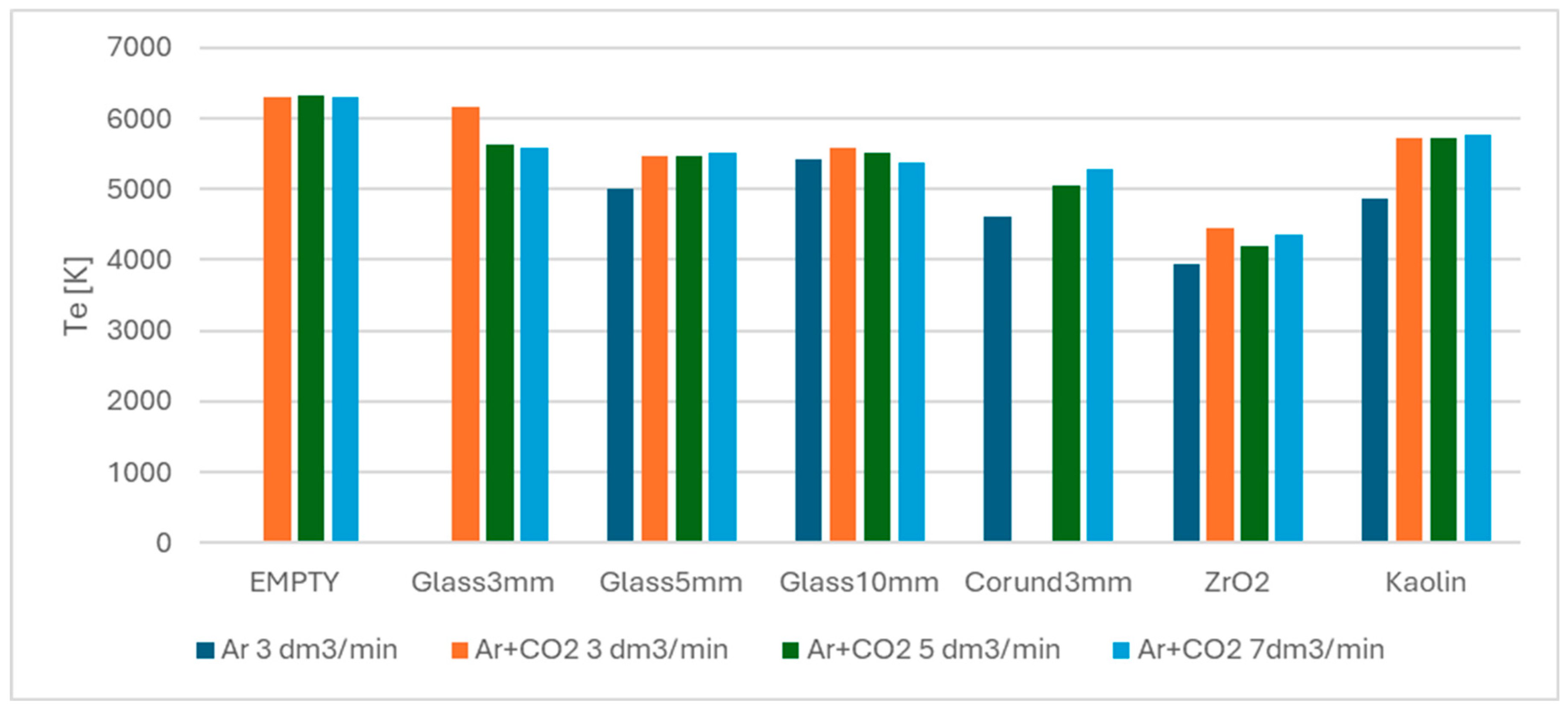

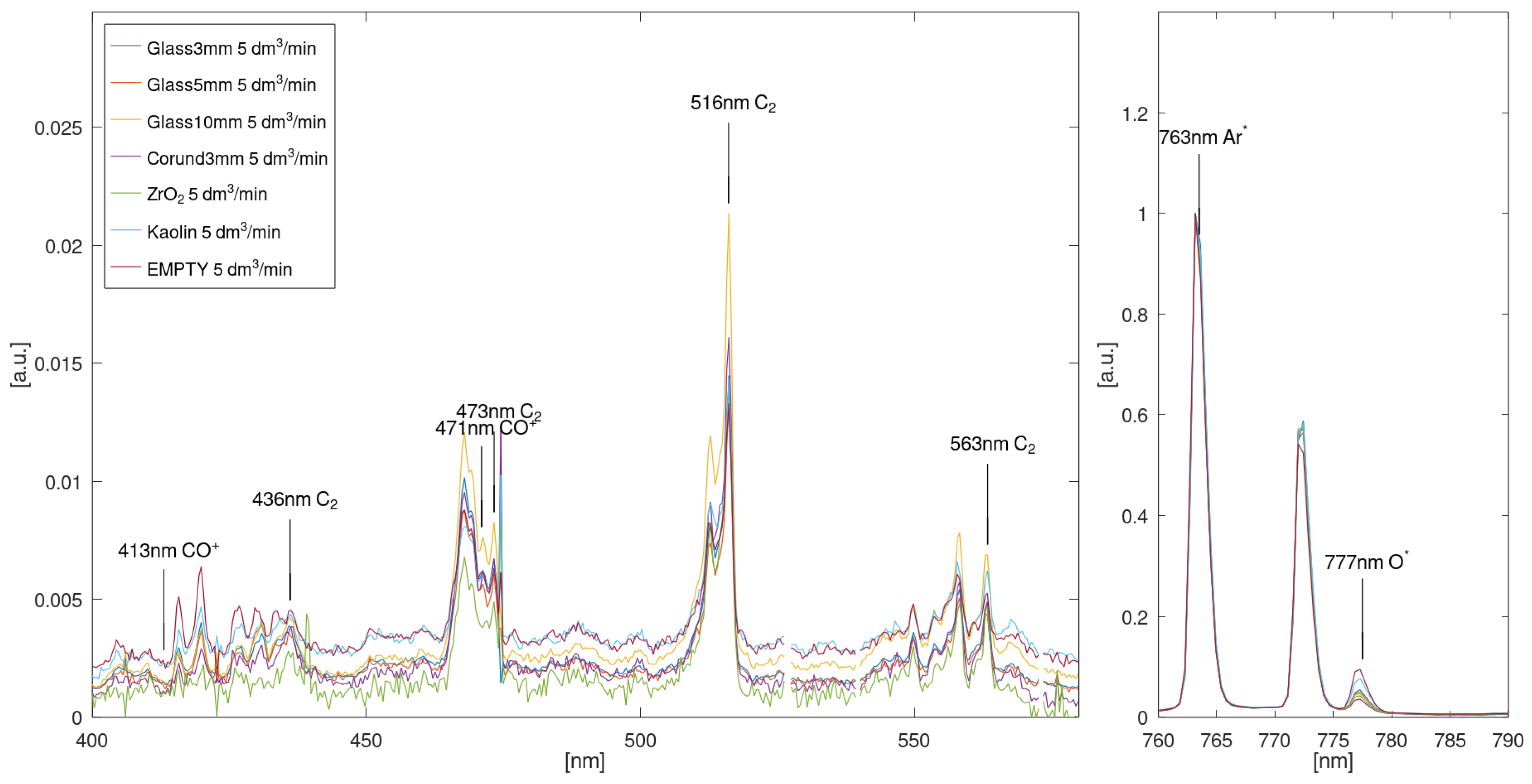

3.4. Spectroscopic Analysis of Plasma Species and Electron Temperature

3.5. Discharge Visualization and Analysis

3.6. Scaling Strategies for Industrial Packed-Bed DBD Reactors in CO2 Utilization

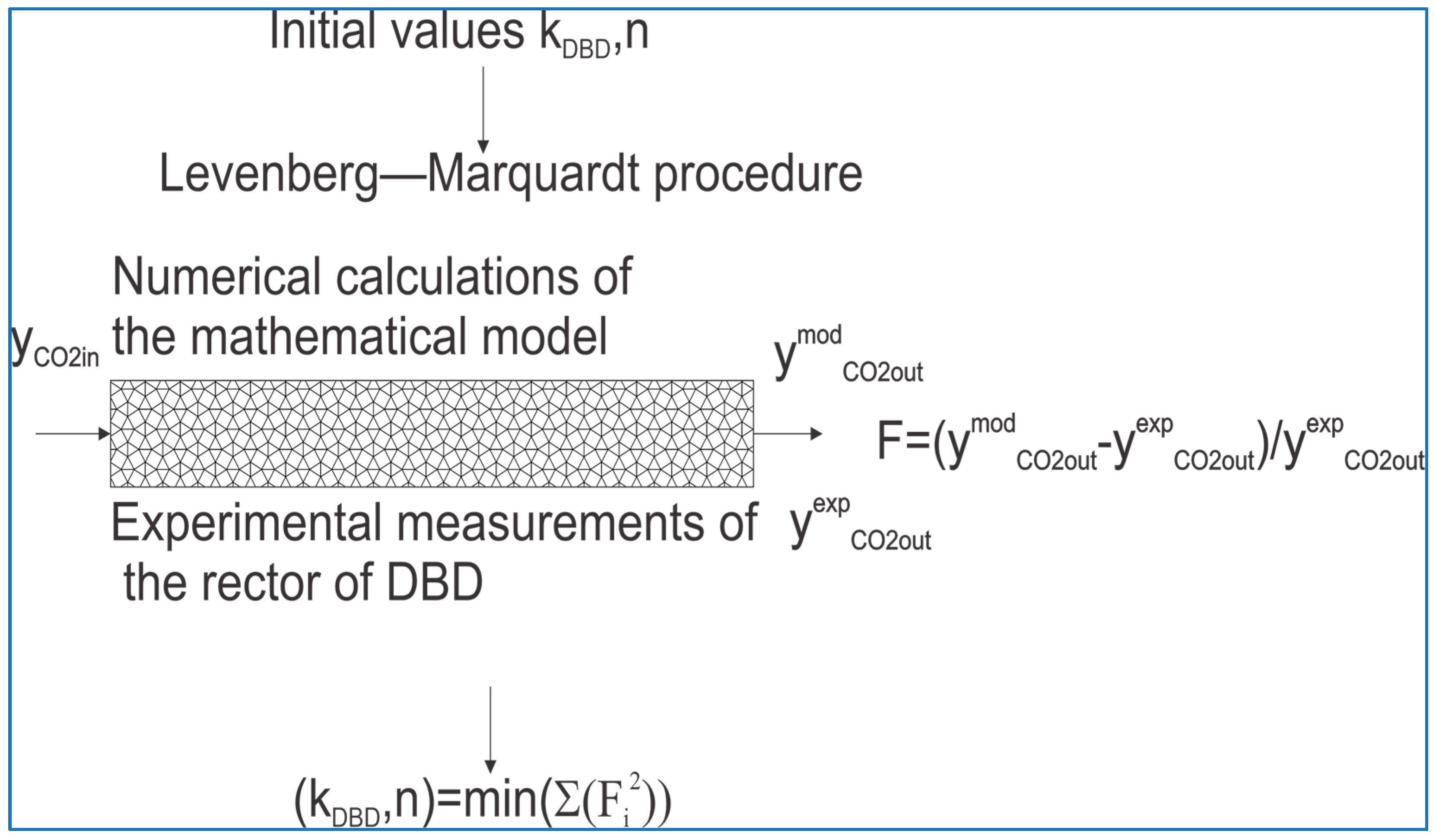

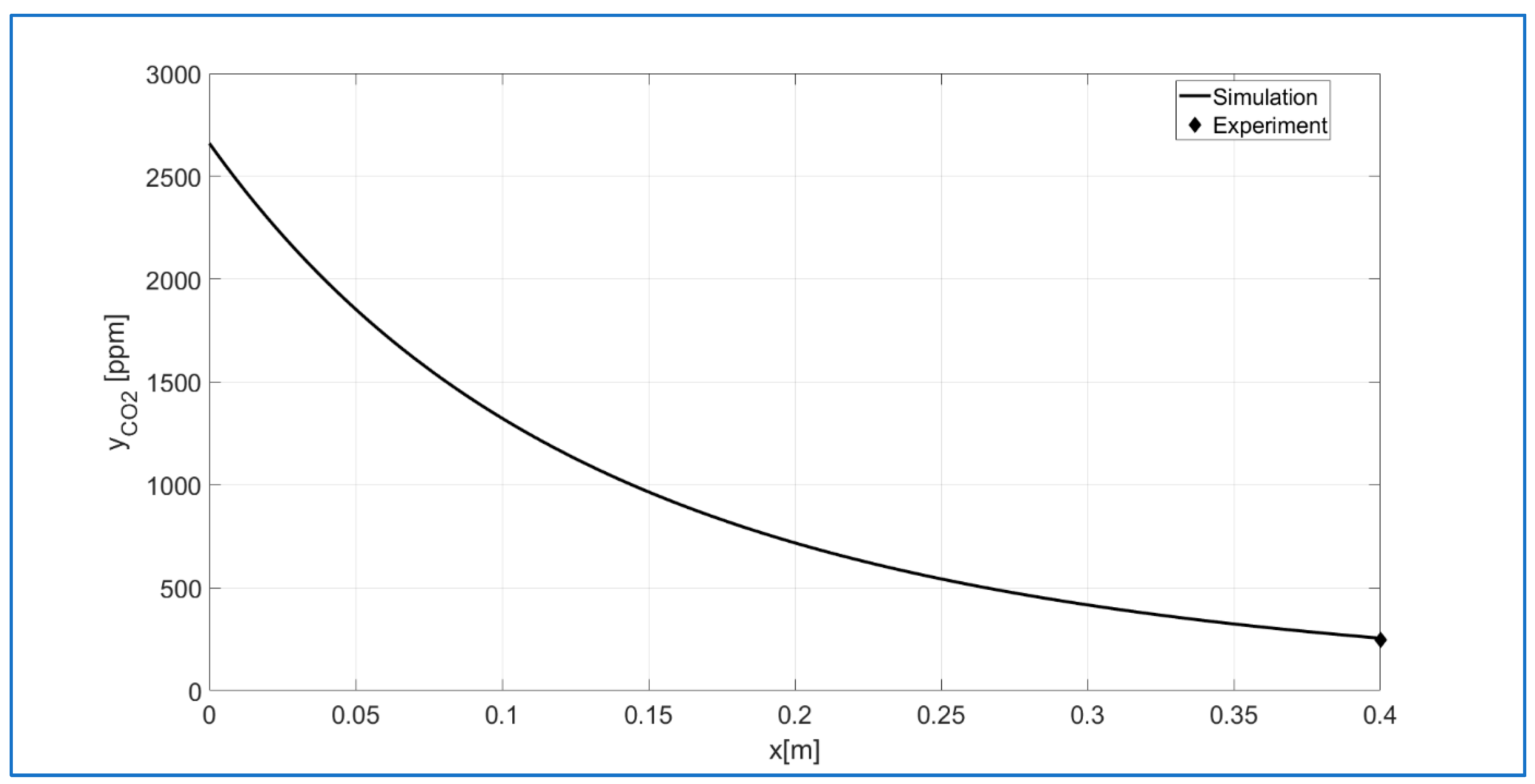

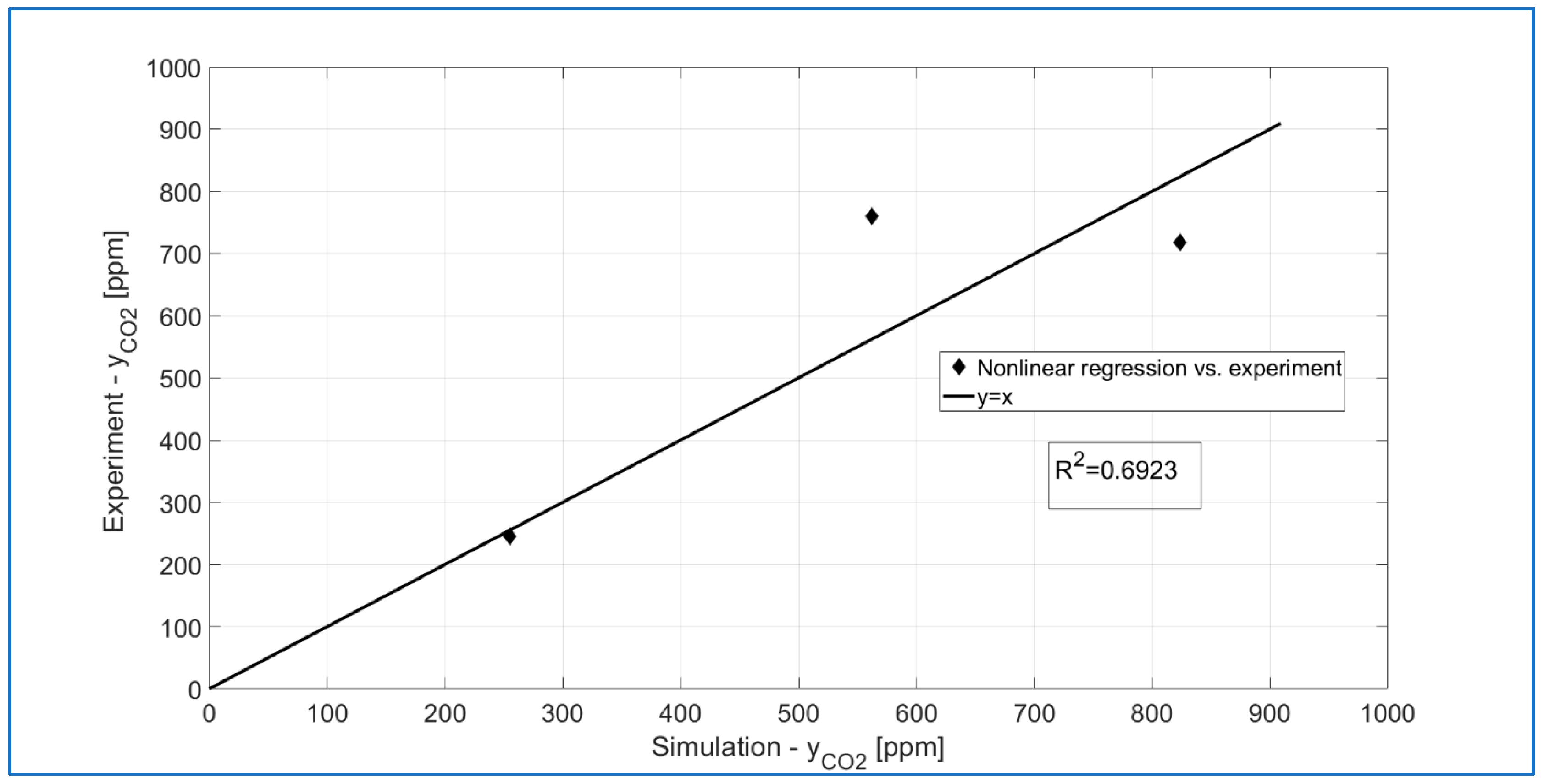

3.7. Mathematical Modeling of a DBD Plasma Reactor

- There is no internal diffusion within the pores of the packing material.

- The reaction rate is determined by the chemical reaction occurring in the plasma generation zone.

- The residence time in the reactor is on the order of several seconds, so molecular diffusion does not affect the mass transfer rate.

- Plasma is generated homogeneously throughout the reactor volume.

- The total pressure in the reactor has a constant value (P = const)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mikkelsen, M.; Jørgensen, M.; Krebs, F.C. The Teraton Challenge. A Review of Fixation and Transformation of Carbon Dioxide. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 43–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Quadrelli, E.A.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis for CO2 Conversion: A Key Technology for Rapid Introduction of Renewable Energy in the Value Chain of Chemical Industries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1711–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeckx, R.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma Technology-a Novel Solution for CO2 Conversion? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5805–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M.; Anastas, P.T.; Zimmerman, J.B. Peer Reviewed: Applying the Principles of Green Engineering to Cradle-to-Cradle Design. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 434A–441A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centi, G.; Iaquaniello, G.; Perathoner, S. Chemical Engineering Role in the Use of Renewable Energy and Alternative Carbon Sources in Chemical Production. BMC Chem. Eng. 2019, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Chen, D.; Ma, C.; Yu, F.; Dai, B. DBD Plasma-ZrO2 Catalytic Decomposition of CO2 at Low Temperatures. Catalysts 2018, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Turnhout, J.; Rouwenhorst, K.; Lefferts, L.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma Catalysis: What Is Needed to Create Synergy? EES Catal. 2025, 3, 669–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayne, S. Carbon Dioxide Splitting: A Summary of the Peer-Reviewed Scientific Literature. Nat. Preced. 2008, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lee, D.-J.; Chang, J.-S. Perspectives on Microalgal CO2-Emission Mitigation Systems—A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Angelini, A. The Use of Solar Energy Can Enhance the Conversion of Carbon Dioxide into Energy-Rich Products: Stepping towards Artificial Photosynthesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013, 371, 20120111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yan, Z.; Chen, J. Advances and Challenges for the Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to CO: From Fundamentals to Industrialization. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 20795–20816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Centi, G. Plasma Technology for CO2 Conversion: A Personal Perspective on Prospects and Gaps. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Tu, X.; Whitehead, J.C.; Centi, G.; Lefferts, L.; Guaitella, O.; Azzolina-Jury, F.; Kim, H.H.; Murphy, A.B.; Schneider, W.F.; et al. The 2020 Plasma Catalysis Roadmap. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 443001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Snyders, R.; Britun, N. CO2 conversion Using Catalyst-Free and Catalyst-Assisted Plasma-Processes: Recent Progress and Understanding. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 49, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salden, A.; Budde, M.; Garcia-Soto, C.A.; Biondo, O.; Barauna, J.; Faedda, M.; Musig, B.; Fromentin, C.; Nguyen-Quang, M.; Philpott, H.; et al. Meta-Analysis of CO2 Conversion, Energy Efficiency, and Other Performance Data of Plasma-Catalysis Reactors with the Open Access PIONEER Database. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 86, 318–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Qi, F.; Zhang, N.; Pu, Y.; Tang, X.; Huang, Q. Progress and Future of CO2 Conversion Based on Plasma Catalysis. DeCarbon 2025, 8, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Ramli, Z.A.; Pasupuleti, J.; Samidin, S.; Wan Isahak, W.N.R.; Sofiah, A.G.N.; Koh, S.P. An Overview of the Conversion Technologies of CO2 into Active CO Molecule: Reactor Engineering, Reaction Pathways, Product Purification and Upgrading. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, A. Plasma Chemistry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; ISBN 1-139-47173-2. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.; Shen, B.; Craven, M.; Wang, Y.; Kang, D.; Wu, C.; Tu, X. A Review of Non-Thermal Plasma Technology: A Novel Solution for CO2 Conversion and Utilization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 109702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, A.; Chirokov, A.; Gutsol, A. Non-Thermal Atmospheric Pressure Discharges. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2005, 38, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Cortese, M.; Renda, S.; Ruocco, C.; Martino, M.; Meloni, E. A Review about the Recent Advances in Selected Nonthermal Plasma Assisted Solid–Gas Phase Chemical Processes. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaerts, A.; Centi, G.; Hicks, J.C. Introduction to Understanding and New Approaches to Create Synergy between Catalysis and Plasma Themed Collection. EES Catal. 2025, 3, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Martín, M.; Oliva-Ramírez, M.; González-Elipe, A.R.; Gómez-Ramírez, A. Plasma Catalysis for Gas Conversion—Impact of Catalyst on the Plasma Behavior. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2025, 51, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khdary, N.H.; Alayyar, A.S.; Alsarhan, L.M.; Alshihri, S.; Mokhtar, M. Metal Oxides as Catalyst/Supporter for CO2 Capture and Conversion, Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubev, O.; Maximov, A. Hybrid Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Dissociation over Basic Metal Oxides Combined with CeO2. Processes 2023, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Kong, M.; Liu, T.; Fei, J.; Zheng, X. Characteristics of the Decomposition of CO2 in a Dielectric Packed-Bed Plasma Reactor. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2012, 32, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, I.; Uytdenhouwen, Y.; Pype, J.; Michielsen, B.; Mertens, J.; Reniers, F.; Meynen, V.; Bogaerts, A. CO2 Dissociation in a Packed Bed DBD Reactor: First Steps towards a Better Understanding of Plasma Catalysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.; Zhu, X.; He, Y.-L.; Yan, J.D.; Tu, X. Plasma-Assisted Conversion of CO2 in a Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor: Understanding the Effect of Packing Materials. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2014, 24, 015011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, T.; Elder, R.; Allen, R. Effects of Particle Size on CO2 Reduction and Discharge Characteristics in a Packed Bed Plasma Reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 293, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, B. Effect of Dielectric Packing Materials on the Decomposition of Carbon Dioxide Using DBD Microplasma Reactor. AIChE J. 2015, 61, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Tang, Q.; Yin, S.; Sato, T. Investigation of Dielectric Barrier Discharge Dependence on Permittivity of Barrier Materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 131502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Tang, Q.; Yin, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Sato, T. Decomposition of Carbon Dioxide by the Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Plasma Using Ca0.7Sr0.3TiO3 Barrier. Chem. Lett. 2004, 33, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Enhancement of CO2 Conversion Rate and Conversion Efficiency by Homogeneous Discharges. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2012, 32, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuśmierek, K.; Świątkowski, A.; Kotkowski, T.; Cherbański, R.; Molga, E. Adsorption of Bisphenol a from Aqueous Solutions by Activated Tyre Pyrolysis Char—Effect of Physical and Chemical Activation. Chem. Process Eng. 2023, 41, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskal, A.; Jagodowicz, W.; Penconek, A.; Zaraska, K. Low-Cost Sensor System for Air Purification Process Evaluation. Sensors 2024, 24, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomy, H.M.; Yasoob, N.A.; Murbat, H.H. Evaluate the Argon Plasma Jet Parameters by Optical Emission Spectroscopy. Kuwait J. Sci. 2023, 50, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassou, S.; Piquemal, A.; Merbahi, N.; Marchal, F.; Yousfi, M. Experimental Characterization of Argon/Air Mixture Microwave Plasmas Using Optical Emission Spectroscopy. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2020, 370, 111278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.S.; Atlabachew, M.; Aragaw, B.A.; Asmare, Z.G. Synthesis of Kaolin-Supported Nickel Oxide Composites for the Catalytic Oxidative Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4287–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.K.; Choi, J.-W.; Yue, S.H.; Lee, H.; Na, B.-K. Synthesis Gas Production via Dielectric Barrier Discharge over Ni/γ-Al2O3 Catalyst. Plasma Technol. Catal. 2004, 89, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, P.; Gomez, A.; Vergara, J.; Martínez, H.; Torres, C. Plasma Diagnostics of Glow Discharges in Mixtures of CO2 with Noble Gases. Rev. Mex. Fis. 2017, 63, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laer, K.; Bogaerts, A. Improving the Conversion and Energy Efficiency of Carbon Dioxide Splitting in a Zirconia-Packed Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor. Energy Technol. 2015, 3, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Lee, H.M.; Chen, S.H.; Chang, M.B. Review of Packed-Bed Plasma Reactor for Ozone Generation and Air Pollution Control. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 2122–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelschatz, U. Collective Phenomena in Volume and Surface Barrier Discharges. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 257, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemakhin, A.Y.; Zheltukhin, V.S. Mathematical Modelling of RF Plasma Flow at Low Pressures with 3D Electromagnetic Field. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 7120217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, Y.A.; Shakhatov, V.A. Decomposition of CO2 in Atmospheric-Pressure Barrier Discharge (Analytical Review). Plasma Phys. Rep. 2022, 48, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liang, J.; Wu, L.; Wu, L.; Kawi, S. Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma-Assisted Catalytic CO2 Hydrogenation: Synergy of Catalyst and Plasma. Catalysts 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewak, M. Mathematical Modelling of Fixed Bed Catalytic Reactors in the Dry Methane Reforming Process. Chem. Process Eng. New Front. 2025, 46, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, A.; Bogaerts, A.; Reniers, F. Routes to Increase the Conversion and the Energy Efficiency in the Splitting of CO2 by a Dielectric Barrier Discharge. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 084004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glass 10 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 3 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellet/bead diameter [m] | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.01 |

| Pellet height [m] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.01 |

| Number of pellets/beads [-] | 176 | 1803 | 8121 | 8117 | 7796 | 211 |

| Packing bed mass [kg] | 0.257 | 0.303 | 0.333 | 0.276 | 0.421 | 0.122 |

| Packing bed volume ×10−4 [m3] | 0.922 | 1.180 | 1.148 | 1.147 | 1.102 | 1.657 |

| Packing bed porosity [%] | 32.593 | 41.736 | 40.605 | 40.585 | 38.980 | 58.611 |

| Total surface area of pellets/beads [m2] | 0.014 | 0.035 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.055 | 0.099 |

| Concentration [wt.%] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Glass 3 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 10 mm |

| Na | 2.800 | 2.546 | 0.196 |

| Mg | 1.982 | 1.712 | 0.096 |

| Al | 1.290 | 1.126 | 0.482 |

| Si | 15.126 | 14.909 | 7.905 |

| P | 0.244 | 0.247 | 0.252 |

| Cl | 0.047 | 0.063 | 0.042 |

| K | 0.032 | 0.058 | 0.226 |

| Ca | 4.513 | 4.324 | 2.000 |

| Fe | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.079 |

| Zn | 2.297 | 1.966 | 0.001 |

| Zr | 0.090 | 0.133 | 0.078 |

| Mo | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.006 |

| Sb | 0.955 | 0.853 | 0.054 |

| Ce | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.168 |

| Ba | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.099 |

| Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Conc. [wt.%] | Compound | Conc. [wt.%] | Compound | Conc. [wt.%] |

| Mg | 0.123 | Mg | 0.299 | Mg | 0.307 |

| Al | 5.407 | Al | 25.903 | Al | 6.888 |

| Si | 16.304 | Si | 2.000 | Si | 12.623 |

| P | 0.254 | P | 0.230 | P | 0.272 |

| Cl | 0.004 | K | 0.031 | K | 1.020 |

| K | 2.211 | Ca | 0.965 | Ca | 0.924 |

| Ti | 0.063 | Fe | 0.053 | Ti | 0.140 |

| Fe | 0.191 | Y | 0.059 | Fe | 1.437 |

| Zr | 7.986 | Ni | 0.050 | ||

| Ba | 2.179 | Zr | 0.022 | ||

| Ce | 0.020 | Ba | 0.055 | ||

| Mean Specific Energy Input ± SD [kJ/mol] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q Ar [dm3/min] | Glass 10 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 3 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty Reactor |

| 3 | 27.07 ±1.72 | 26.3 ±1.46 | 26.59 ±1.45 | 31.6 ±3.95 | 31.38 ±6.08 | 26.2 ±0.78 | 27.57 ±2.03 |

| 5 | 16.36 ±1.03 | 15.35 ±0.7 | 15.75 ±0.81 | 17.75 ±3.08 | 17.14 ±3.1 | 15.75 ±0.5 | 15.99 ±0.28 |

| 7 | 11.64 ±0.66 | 11.48 ±0.77 | 10.9 ±0.49 | 13.00 ±2.19 | 11.22 ±0.25 | 11.11 ±0.44 | 11.8 ±0.3 |

| Absolute CO2 Conversion ± SD [%] | |||||||

| Q Ar [dm3/min] | Glass 10 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 3 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty Reactor |

| 3 | 54.28 ±2.73 | 69.86 ±9.77 | 68.60 ±5.67 | 78.62 ±1.61 | 68.40 ±1.19 | 44.93 ±5.32 | 40.21 ±0.11 |

| 5 | 55.35 ±2.11 | 62.24 ±1.76 | 68.63 ±0.68 | 70.43 ±8.78 | 65.50 ±2.29 | 50.86 ±1.41 | 41.52 ±0.32 |

| 7 | 52.55 ±3.11 | 62.45 ±0.35 | 67.80 ±1.83 | 70.39 ±7.8 | 61.69 ±3.34 | 52.03 ±1.29 | 39.55 ±2.99 |

| Energy Efficiency ± SD [%] | |||||||

| Q Ar [dm3/min] | Glass 10 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 3 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty reactor |

| 3 | 1.52 ±0.12 | 2.01 ±0.30 | 1.95 ±0.19 | 1.88 ±0.24 | 2.04 ±0.09 | 1.30 ±0.16 | 1.10 ±0.08 |

| 5 | 2.49 ±0.18 | 2.99 ±0.16 | 3.21 ±0.17 | 2.93 ±0.62 | 3.15 ±0.14 | 2.38 ±0.10 | 1.92 ±0.04 |

| 7 | 3.29 ±0.27 | 3.97 ±0.27 | 4.54 ±0.24 | 3.95 ±0.80 | 4.21 ±0.10 | 3.42 ±0.16 | 2.44 ±0.23 |

| Energy Cost ± SD [kJ/mol CO2 reduced] | |||||||

| Q Ar [dm3/min] | Glass 10 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 3 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty Reactor |

| 3 | 18,659.94 ±1508.86 | 14,087.05 ±2118.92 | 14,501.49 ±1435.58 | 15,038.69 ±1904.79 | 13,856.18 ±611.9 | 21,822.36 ±2665.76 | 25,647.98 ±1886.27 |

| 5 | 11,344.57 ±832.19 | 9464.71 ±510.21 | 8808.43 ±463.51 | 9671.06 ±2064.56 | 8993.76 ±405.04 | 11,880.22 ±502.56 | 14,778.02 ±295.58 |

| 7 | 8594.93 ±703.35 | 7134.93 ±482.62 | 6236.16 ±326.34 | 7166.82 ±1443.96 | 6727.48 ±158.93 | 8284.27 ±386.61 | 11,579.3 ±1112.25 |

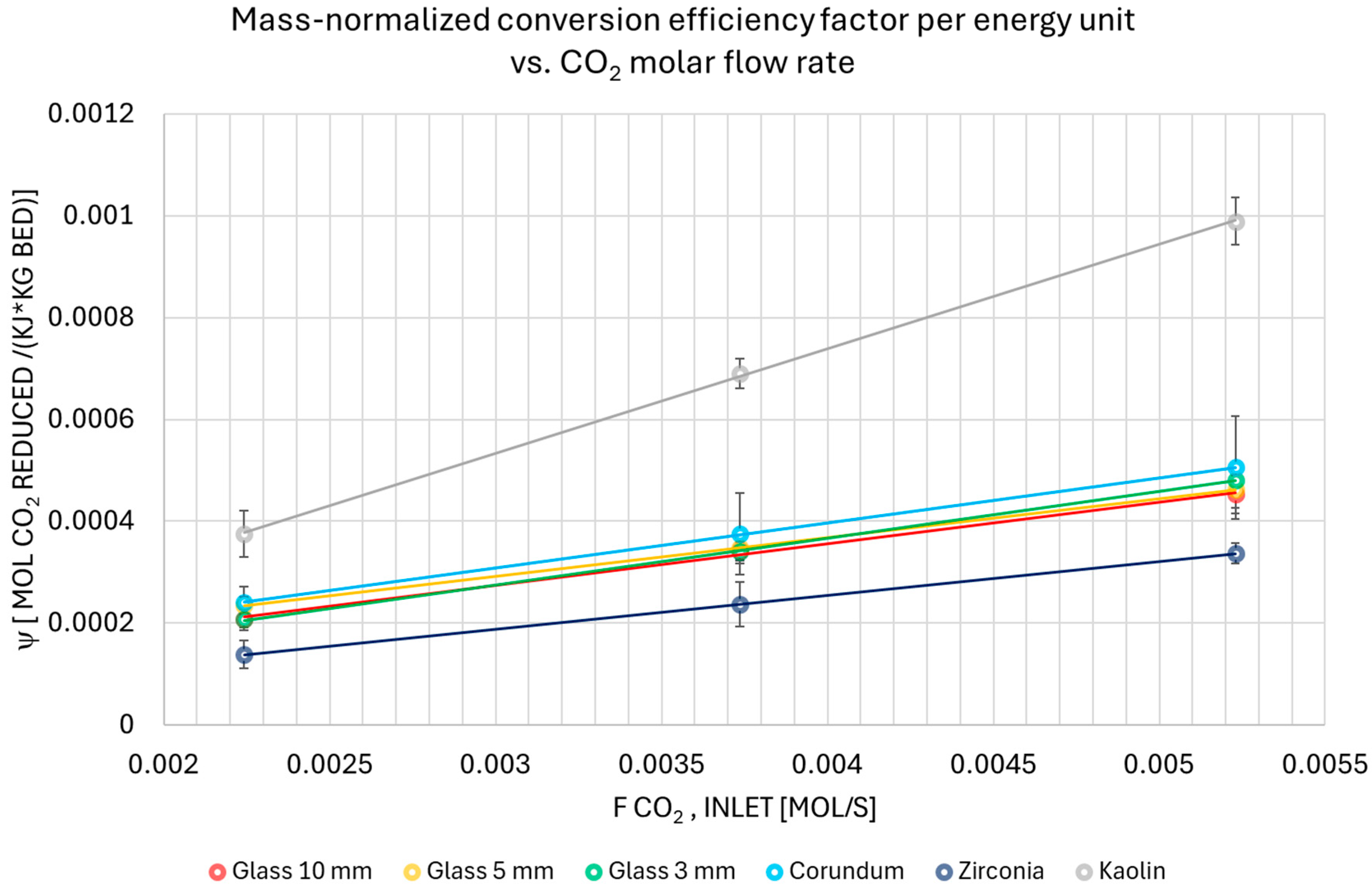

| Mass-normalized Conversion Efficiency Factor Per Energy Unit ± SD × 10−7 [mol CO2 reduced/(kJ·kg bed)] | |||||||

| Q Ar [dm3/min] | Glass 10 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 3 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty Reactor |

| 3 | 2.09 ±0.17 | 2.34 ±0.35 | 2.07 ±0.21 | 2.41 ±0.31 | 1.38 ±0.27 | 3.76 ±0.46 | NA |

| 5 | 3.43 ±0.25 | 3.49 ±0.19 | 3.41 ±0.18 | 3.75 ±0.80 | 2.37 ±0.44 | 6.9 ±0.29 | NA |

| 7 | 4.53 ±0.37 | 4.63 ±0.31 | 4.82 ±0.25 | 5.06 ±1.02 | 3.37 ±0.20 | 9.89 ±0.46 | NA |

| λ [nm] | Eu [eV] | Aul [1/s] | gu | Transition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 420.0 | 14.49 | 9.67 × 105 | 7 | 5p-4s |

| 696.5 | 13.32 | 6.39 × 106 | 3 | 4p-4s |

| 706.0 | 13.3 | 3.80 × 106 | 5 | 4p-4s |

| 842.5 | 13.09 | 2.15 × 107 | 5 | 4p-4s |

| 852.0 | 13.8 | 1.37 × 107 | 3 | 4p-4s |

| Ar 3 dm3/min | Ar + CO2 3 dm3/min | Ar + CO2 5 dm3/min | Ar + CO2 7 dm3/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empty reactor | ND | 6306 | 6335 | 6312 |

| Glass 3 mm | ND | ND | 5631 | 5575 |

| Glass 5 mm | 5003 | 6162 | 5469 | 5509 |

| Glass 10 mm | 5424 | 5587 | 5504 | 5388 |

| Corundum | 4621 | ND | 5054 | 5287 |

| Zirconia | 3946 | 4440 | 4207 | 4368 |

| Kaolin | 4871 | 5724 | 5718 | 5765 |

| Species | λ [nm] | Upper Level | Lower Level | Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO+ | 413.05 | X2Σ | A2П | No |

| C2 | 436.08 | X3Пu | A2Пg | Yes |

| CO+ | 471.01 | X2Σ | A2П | Yes |

| C2 | 473.61 | X3Пu | A3Пg | Yes |

| C2 | 516.40 | X3Пu | A3Пg | Yes |

| C2 | 563.86 | X3Пu | A3Пg | Yes |

| O2+ | 642.29 | X4Пu | b4Σ−g | No |

| O* | 777.48 | 2s22p3(4S0)3p | 2s22p3(4S0)3s | Yes |

| Species | λ [nm] | Line | Glass 10 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 3 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty Reactor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO+ | 413.05 | CO+@413.05 nm | 1.102 | 1.000 | 1.112 | 0.823 | 0.784 | 1.686 | 1.772 |

| C2 | 436.08 | C2@436.08 nm | 1.123 | 1.000 | 1.212 | 1.122 | 0.743 | 1.279 | 1.325 |

| CO+ | 471.01 | CO+@471.01 nm | 1.103 | 1.000 | 1.353 | 1.076 | 0.673 | 1.075 | 1.093 |

| C2 | 473.61 | C2@473.61 nm | 1.101 | 1.000 | 1.359 | 1.106 | 0.804 | 1.039 | 1.037 |

| C2 | 516.4 | C2@516.4 nm | 1.090 | 1.000 | 1.608 | 1.212 | 1.043 | 1.079 | 1.001 |

| C2 | 563.86 | C2@563.86 nm | 1.109 | 1.000 | 1.601 | 1.136 | 1.089 | 1.443 | 1.220 |

| O* | 777.48 | O*@777.48 nm | 1.099 | 1.000 | 0.949 | 0.727 | 0.863 | 1.561 | 1.920 |

| λ [nm] | Glass 3 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 10 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty Reactor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 413.05 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.031 | 0.025 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| 471.01 | 0.114 | 0.114 | 0.162 | 0.168 | 0.089 | 0.078 | 0.065 |

| 777.48 (O*) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| MEDIAN | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.097 | 0.100 | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.045 |

| RANK | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| λ [nm] | Glass 3 mm | Glass 5 mm | Glass 10 mm | Corundum | Zirconia | Kaolin | Empty Reactor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 436.08 | 0.070 | 0.069 | 0.088 | 0.106 | 0.059 | 0.056 | 0.048 |

| 473.61 | 0.123 | 0.123 | 0.175 | 0.186 | 0.114 | 0.082 | 0.066 |

| 516.4 | 0.265 | 0.267 | 0.453 | 0.446 | 0.323 | 0.185 | 0.139 |

| 563.86 | 0.088 | 0.087 | 0.146 | 0.136 | 0.109 | 0.080 | 0.055 |

| 777.48 (O*) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| MEDIAN | 0.105 | 0.105 | 0.161 | 0.161 | 0.112 | 0.081 | 0.061 |

| RANK | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorosz, A.; Zaraska, K.; Lewak, M.; Małolepszy, A.; Jaworski, J.; Moskal, A. The Use of Metal Oxides (Al2O3 and ZrO2) and Supports (Glass and Kaolin) to Enhance DBD Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Conversion. Materials 2025, 18, 5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235411

Dorosz A, Zaraska K, Lewak M, Małolepszy A, Jaworski J, Moskal A. The Use of Metal Oxides (Al2O3 and ZrO2) and Supports (Glass and Kaolin) to Enhance DBD Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Conversion. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235411

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorosz, Agata, Krzysztof Zaraska, Michał Lewak, Artur Małolepszy, Jakub Jaworski, and Arkadiusz Moskal. 2025. "The Use of Metal Oxides (Al2O3 and ZrO2) and Supports (Glass and Kaolin) to Enhance DBD Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Conversion" Materials 18, no. 23: 5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235411

APA StyleDorosz, A., Zaraska, K., Lewak, M., Małolepszy, A., Jaworski, J., & Moskal, A. (2025). The Use of Metal Oxides (Al2O3 and ZrO2) and Supports (Glass and Kaolin) to Enhance DBD Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Conversion. Materials, 18(23), 5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235411