Improving the Friction-Wear Properties and Wettability of Titanium Through Microstructural Changes Induced by Laser Surface Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Laser Surface Treatment Parameters

2.3. Surface Topography Observation and Roughness Measurement

2.4. Microstructure, Chemical and Phase Composition Examinations

2.5. Friction-Wear Test Parameters

2.6. Wettability Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Roughness Before and After Laser Treatment

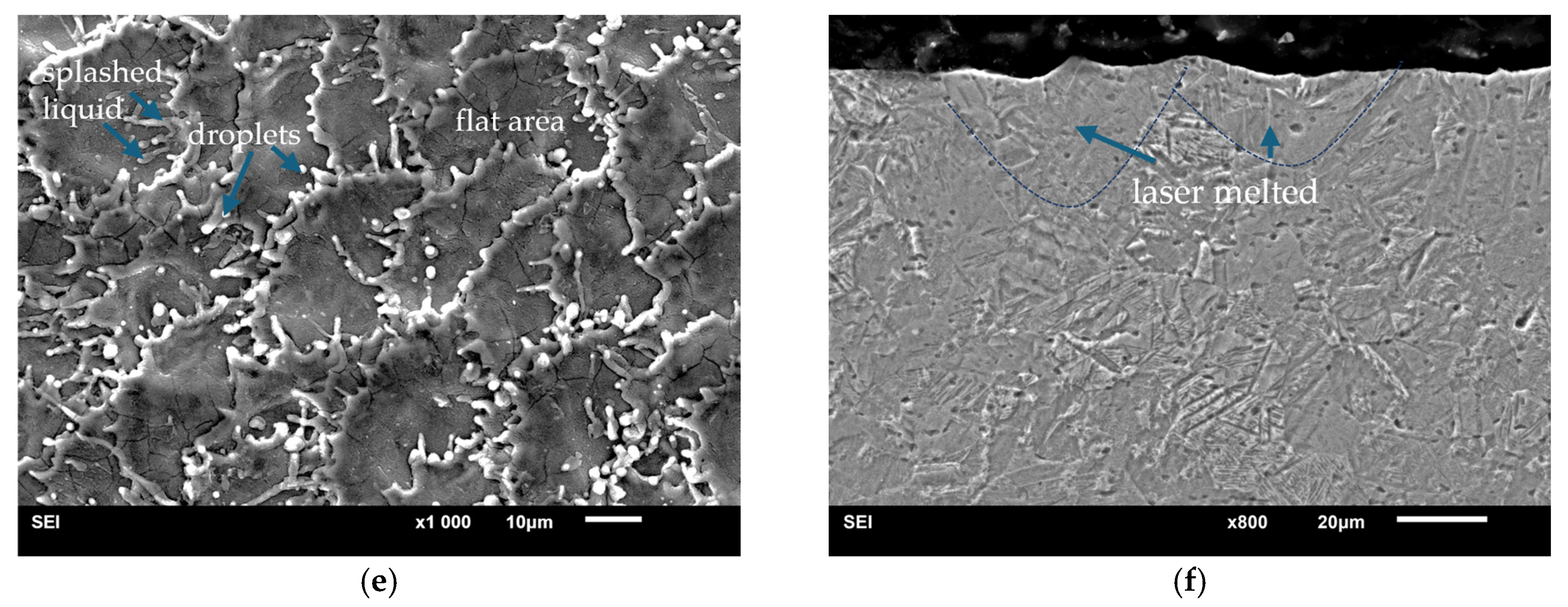

3.2. Microstructural Changes, Surface Roughness of Laser Treated Specimens

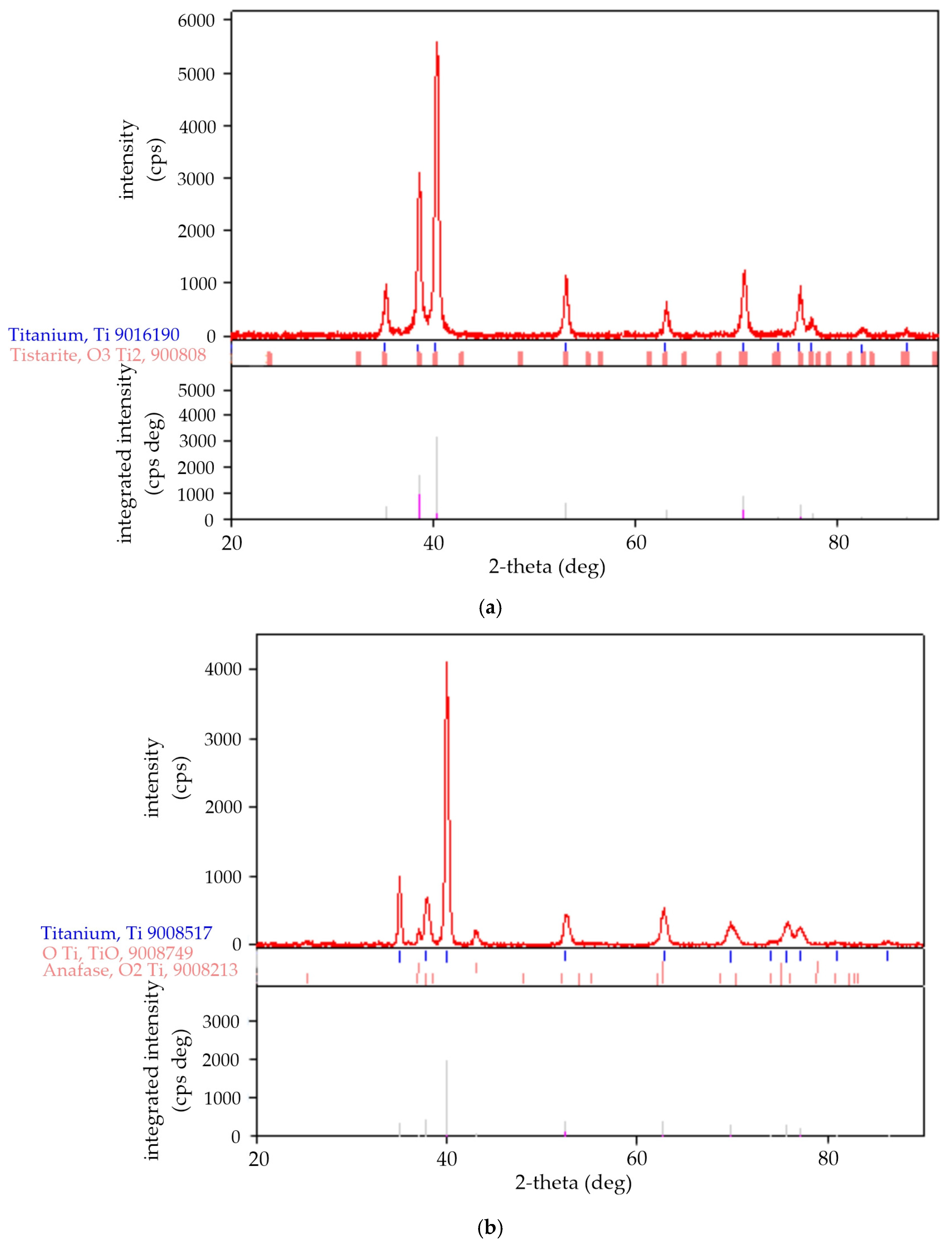

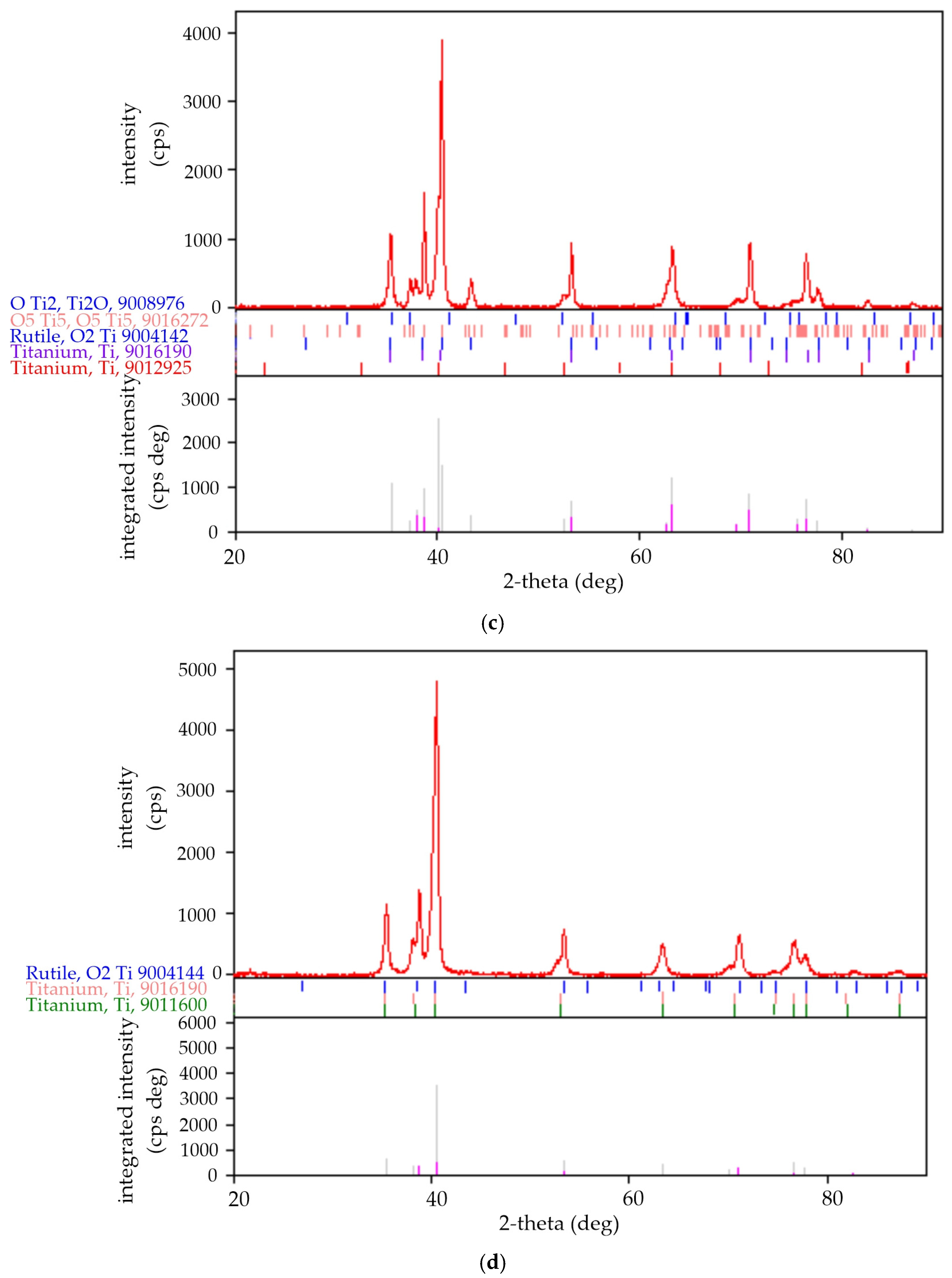

3.3. Changes in Phase Composition

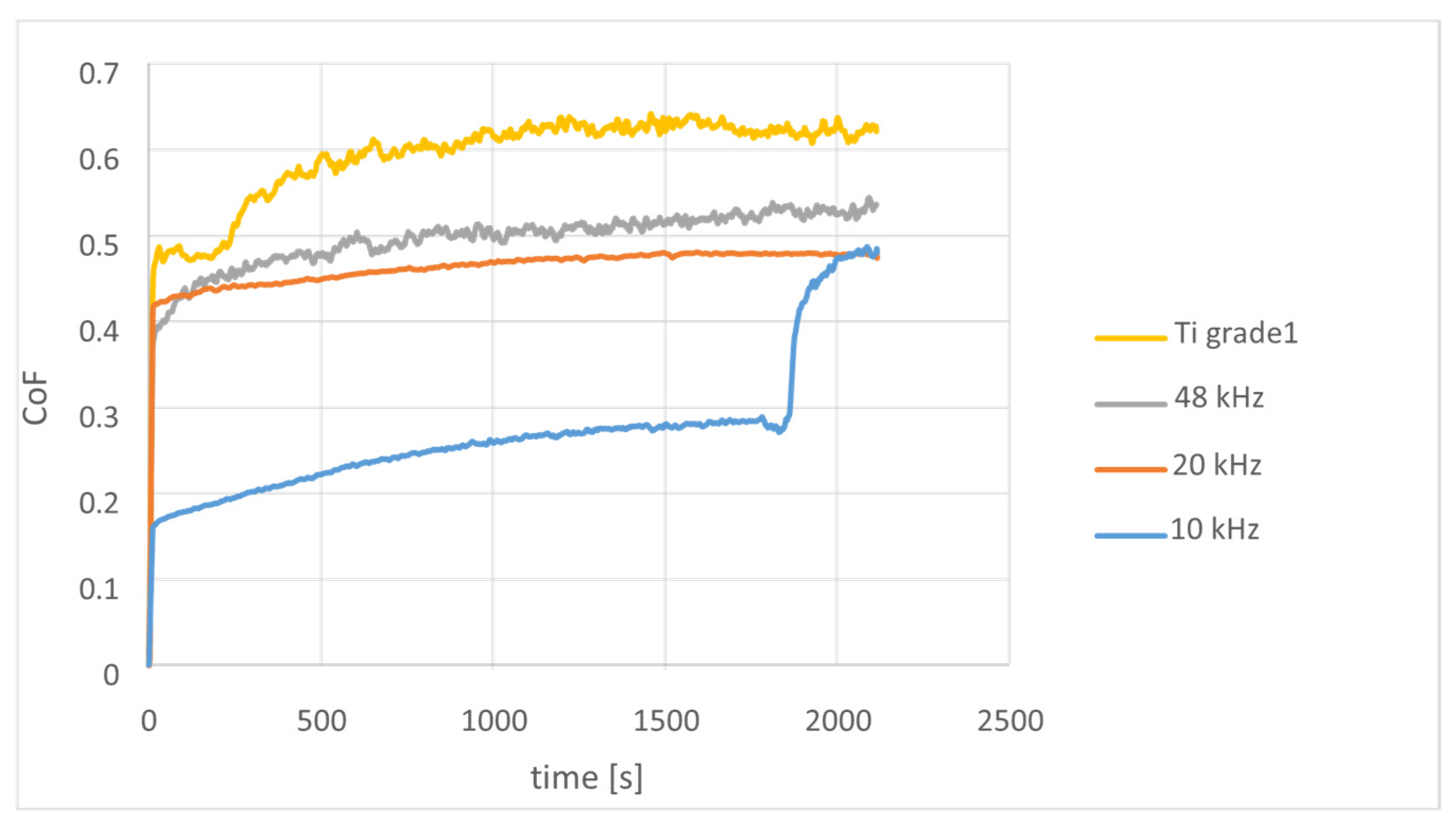

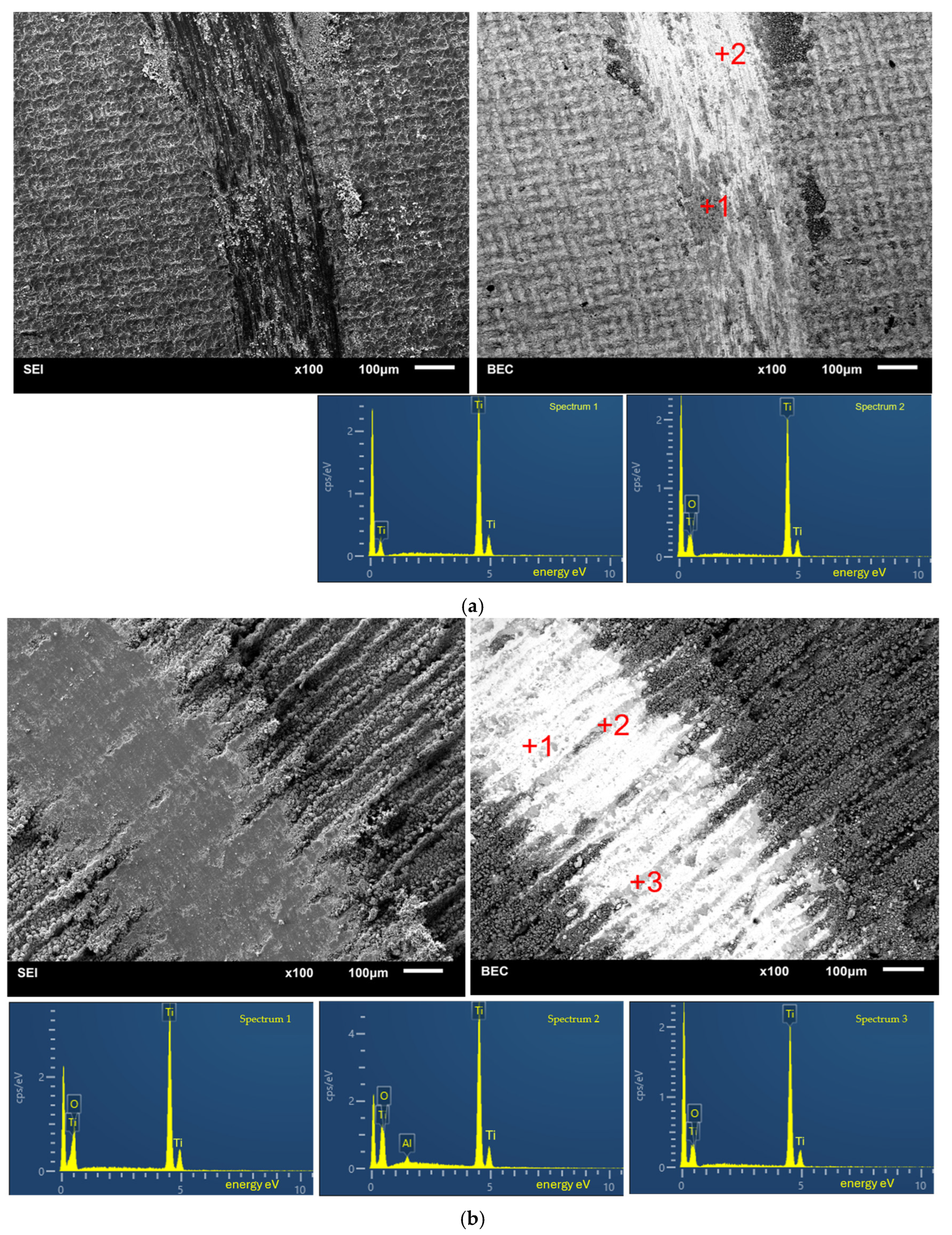

3.4. Resistance to Wear and Coefficient of Friction

- VLo—the volume of worn material calculated on the basis of measurement of the cross-sectional area of the friction path using an optical profilometer (confocal microscope), according to ISO 8295:1994 [26];

- VLm—the volume loss calculated by a difference in weight of the tested specimen before and after the friction-wear test, with respect to the theoretical density of the tested specimen, according to Equation (2).

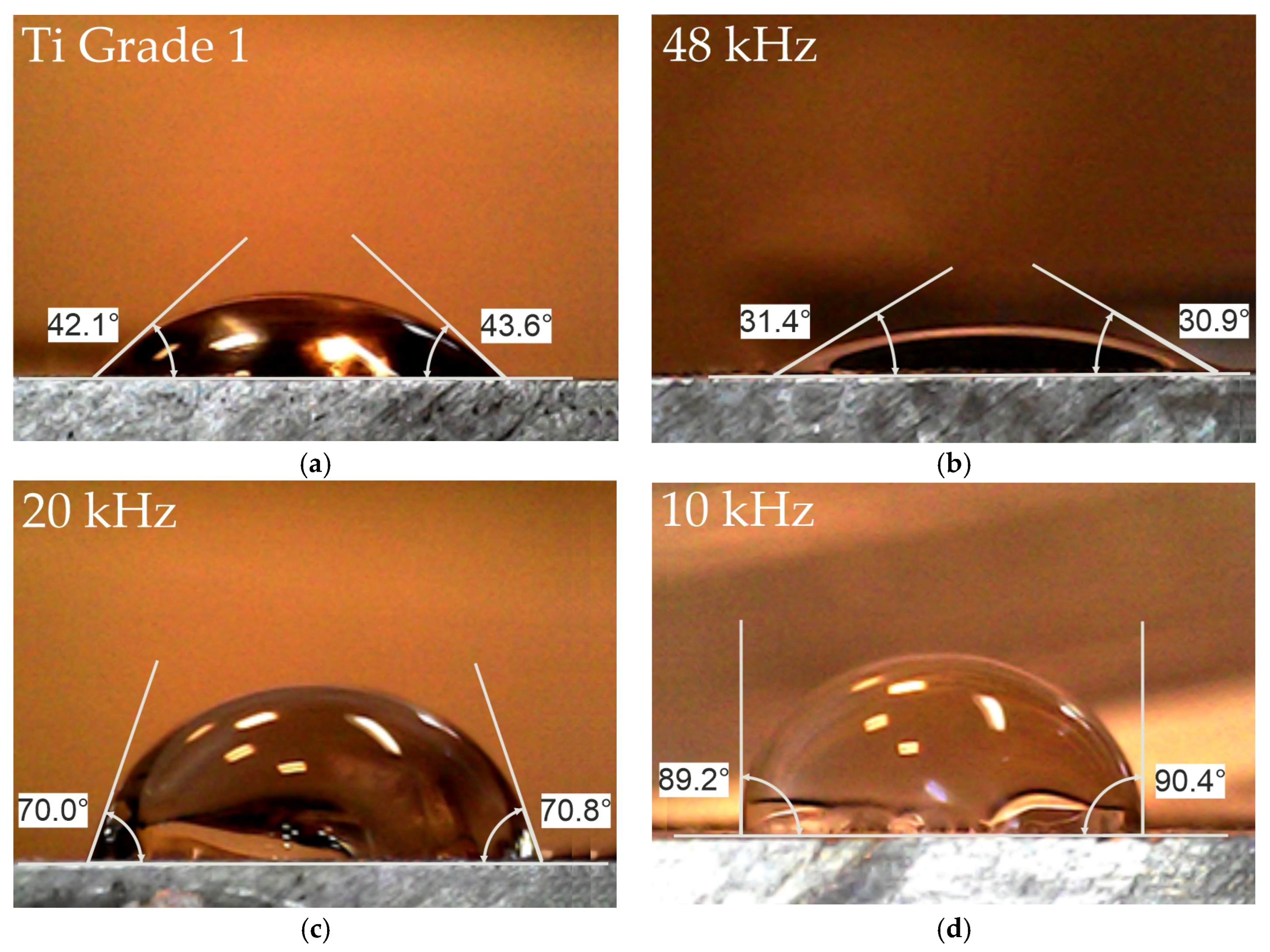

3.5. Effect of Laser Processing on the Wettability of Ti Grade 1 Surfaces

4. Conclusions

- Laser surface treatment is an effective and environmentally friendly method of increasing friction-wear properties of titanium grade 1 with respect to resistance to wear and coefficient of friction in friction contact with alumina.

- Laser treatment of Ti grade 1 carried out in air caused significant changes in the phase composition of the treated material, both in the resulting surface layer and in the subsurface area.

- In the surface layer of Ti grade 1, which is formed as a result of laser treatment in air, titanium oxides with different Ti-to-O ratios are formed. The main oxide is TiO2, which, depending on the processing parameters, can occur in the form of rutile, anatase and/or brookite in various contents.

- In the subsurface areas (under the titanium oxide layer) laser treatment causes partial phase transformation of α-Ti to β-Ti or to the martensite α′-Ti phase.

- The changes in the microstructure of Ti grade 1 in the surface layer formed during the laser treatment in air and in the subsurface heat affected zone are of key importance for the achieved improvement of friction-wear properties.

- Laser treatment of titanium surfaces carried out in air allows the wettability control in a wide range of contact angles. It was demonstrated that it is possible to obtain a superhydrophilic or hydrophobic surface, depending on the type of the surface pattern, roughness, and the phase composition of the oxides formed on it.

- Among the selected variants of laser treatment parameters of Ti grade 1, the most advantageous in terms of superphilicity is the 48 kHz variant, but it increases the surface roughness significantly.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCracken, M. Dental Implant Materials: Commercially Pure Titanium and Titanium Alloys. J. Prosthodon. 1999, 8, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.G.K.; Oh, J. Recent advances in dental implants. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 39, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, K.A.; Khan, M.M.; Dey, A.; Wani, M.F. Advancements in surface engineering: A comprehensive review of functionally graded coatings for biomaterial implants. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 19, 100509. [Google Scholar]

- Catherine, D.K.; Bin Abdul Hamid, D. The effect of heat treatment on the tensile strength and ductility of pure titanium grade 2. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 429, 012014. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Hemptenmacher, J.; Kumpfert, J.; Leyens, C. Structure and properties of titanium and titanium alloys. In Titanium and Titanium Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications; Peters, M., Leyens, C., Eds.; Willey Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Peng, X.D. Microstructure and property of vacuum thermal oxidation layer of Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. Trans. Mater. Heat. Treat. 2013, 34, 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, M.; Wen, C.; Hodgson, P.; Li, Y. Thermal oxidation behavior of bulk titanium with nanocrystalline surface layer. Corros. Sci. 2012, 59, 352–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H.; Zhong, L.; Kang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, W.; Zhenlin, L.; Xu, Y. A review on wear-resistant coating with high hardness and high toughness on the surface of titanium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 882, 160645. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.D.; Holladay, J.W. Friction and wear properties of titanium. Wear 1958, 2, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granchi, D.; Cenni, E.; Tigani, D.; Trisolino, G.; Baldini, N.; Giunti, A. Sensitivity to implant materials in patients with total knee arthroplasties. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1494–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaziem, W.; Darwish, M.A.; Hamada, A.; Daoush, W.M. Titanium-Based alloys and composites for orthopedic implants. Applications: A comprehensive review. Mater. Des. 2024, 241, 112850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jażdżewska, M.; Kwidzińska, D.B.; Seyda, W.; Fydrych, D.; Zieliński, A. Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress Measurements of Grade IV Titanium and Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-13Nb-13Zr Titanium Alloys after Laser Treatment. Materials 2021, 14, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, A.; Tosun, E.; Meral, S.E.; Baştan, F.E.; Üstel, F.; Kan, B.; Avcu, E. The effects of diode and Er: YAG laser applications on the surface topography of titanium grade 4 and titanium zirconium discs with sand-blasted and acid-etched (SLA) surfaces. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101680. [Google Scholar]

- Erinosho, M.F.; Akinlabi, E.T. Influence of laser power on the surfacing microstructures and microhardness properties of Ti-6Al-4V-Cualloys using the ytterbium fiber laser. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 596–602. [Google Scholar]

- Perriere, J.; Millon, E.; Fogarassy, E. Recent Advances in Laser Processing of Materials; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.; Srivastava, S.K.; Manna, I.; Majumdar, J.D. Mechanically tailored surface of titanium-based alloy (Ti6Al4V) by laser surface treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 479, 130560. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Shi, W.; Lin, F.; Huang, J.; Yang, C. Impact of picosecond laser surface texturing on the microstructure and corrosion resistance of micro-arc oxidation coating on Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 513, 132445. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, L.; Huang, H.; Yan, J. Fabrication of convex and concave microstructures on Ti6Al4V via nanosecond laser texturing and their distinct effects on surface wettability. J. Manuf. Proc. 2025, 152, 616–630. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM G99-05; Standard Test Method for Wear Testing with a Pin-on-Disk Apparatus. The American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Sheng, Y.; Li, W. In-situ formation of textured TiN coatings on biomedical titanium alloy by laser irradiation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 78, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hanaor, D.A.H.; Sorrell, C.C. Review of the anatase to rutile phase transformation. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 4, 855–874. [Google Scholar]

- Kofstad, P. Nonstoichiometry, Diffusion, and Electrical Conductivity in Binary Metal Oxides; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N.; Xie, R.; Zou, J.; Qin, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. Surface damage mitigation of titanium and its alloys via thermal oxidation: A brief review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2019, 58, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardowska, A.; Kusinski, J.P. Laser welding of Al-Li-Mg-Zr alloy. In Laser Technology VI: Applications; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2000; pp. 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Twardowska, A.; Morgiel, J.; Rajchel, B. On the wear of TiBx/TiSiyC z coatings deposited on 316L steel. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2015, 106, 758–763. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8295:1995; Plastics—Film and Sheeting—Determination of the Coefficients of Friction. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

- Zhu, P.; Dastan, D.; Liu, L.; Wu, L.; Shi, Z.; Chu, Q.-Q.; Altaf, F.; Mohammed, M.K.A. Surface wettability of various phases of titania thin films: Atomic-scale simulation studies. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2022, 118, 108335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, S.; Chen, Y.; Miao, X.; Lü, H.; Jiang, X. Influence of laser fluences and scan speeds on the morphologies and wetting properties of titanium alloy. Optik 2020, 224, 165443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Nouri, M.; Sabour Rouhaghdam, A. An investigation of the wettability and chemical stability of super-hydrophobic coatings on titanium. Thin Solid Films 2022, 762, 139541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition [% wt.] | Tensile Strength TSt [MPa] | Yield Strength YS [MPa] | Hardness HRC/HRB | Young Modulus E [GPa] | Density d [g/cm3] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | Fe | O | C | N | H | |||||

| 99.5 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.080 | 0.030 | 0.015 | 240 | 172 | 70/120 | 105 | 4.51 |

| Specimen | Sz [µm] | Sa [µm] | Surface Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti grade 1 | 20.4 ± 2 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | Scratches of different depths and directions left after grinding |

| 48 kHz | 65.4 ± 6 | 10.1 ± 1.5 | Strongly developed ‘peak and valley’ surface, droplets and pores |

| 20 kHz | 44.1 ± 5 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 3D patterned surface, ripples and splashes |

| 10 kHz | 18.1 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.02 | Homogeneously distributed cavities (pits) after ablation with minor melting at the edges of the pathways |

| Specimen | Phase Name | Content [% wt.] | Space Group | a, b, c [Å] | Volume [Å3] | Card Number | Calc. Density [g/cm3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti grade 1 untreated | α-Ti | 99.0 | 194: P63/mmc, hex. | 2.95, 2.95, 4.679 | 35.265 | 9016190 | 4.508 |

| Tistarite Ti2O3 | 1.0 | 167: R-3c, hex. | 5.11, 5.11, 14.006 | 316.867 | 9008082 | 4.519 | |

| 48 kHz | α-Ti | 90.6 | 194: P63/mmc, hex. | 2.958, 2.958, 4.750 | 36.002 | 9008517 | 4.416 |

| TiO | 7.8 | 225: Fm-3m cubic (fcc) | 4.194, | 73.785 | 9008749 | 5.749 | |

| Anatase TiO2 | 1.6 | 141: I41/amd, choice-1, tetragonal | 3.782, 3.782, 9.514 | 136.124 | 9008213 | 3.897 | |

| 20 kHz | Rutile Ti O2 | 23.0 | 136: P42/mnm tetragonal | 4.656, 4.656, 3.031 | 65.725 | 9004144 | 4.036 |

| α-Ti | 64.3 | 194: P63/mmc hex | 2.931, 2.931, 4.705 | 35.020 | 9016190 | 4.539 | |

| β-Ti | 12.7 | 229: Im-3m cubic (bcc) | 3.283 | 35.38 | 9011925 | 4.05 | |

| 10 kHz | Ti2O | 15 | 191: P6/mmm hex | 5.068, 5.068, 2.882 | 64.123 | 9008976 | 4.340 |

| Ti5O5 | 14 | 12:112/m, unique-c, cell-1. monocl | 5.856, 9.342, 4.143 | 216.177 | 9016272 | 4.906 | |

| Rutile Ti O2 | 4 | 136: P42/mnm tetragonal | 4.664, 4.664, 3.032 | 65.975 | 9004142 | 4.020 | |

| α-Ti | 40 | 194: P63/mmc hex | 2.936, 2.936, 4.663 | 34.831 | 9016190 | 4.564 | |

| α′-Ti | 27 | 191: P6/mmm hex | 4.493,4.493, 2.754 | 2.7546 | 9011600 | 4.950 |

| Specimen | Δm [g] | VL (m) | Wv (m) | VL (op) | Wv (op) | Av. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mm3] | [mm3/Nm] | [mm3] | [mm3/Nm] | CoF | ||

| Ti grade 1 | 9 × 10−4 | 4.059 | 2.018 × 10−2 | 6.816 | 3.38 × 10−2 | 0.59 |

| 48 kHz | 7 × 10−4 | 1.804 | 8.96 × 10−3 | 9.549 | 4.75 × 10−2 | 0.48 |

| 20 kHz | 1 × 10−4 | 0.451 | 2.24 × 10−3 | 1.322 | 2.8 × 10−3 | 0.44 |

| 10 kHz | 1 × 10−4 | 0.451 | 2.24 × 10−3 | 0.567 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Twardowska, A.; Ślusarczyk, Ł. Improving the Friction-Wear Properties and Wettability of Titanium Through Microstructural Changes Induced by Laser Surface Treatment. Materials 2025, 18, 5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235410

Twardowska A, Ślusarczyk Ł. Improving the Friction-Wear Properties and Wettability of Titanium Through Microstructural Changes Induced by Laser Surface Treatment. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235410

Chicago/Turabian StyleTwardowska, Agnieszka, and Łukasz Ślusarczyk. 2025. "Improving the Friction-Wear Properties and Wettability of Titanium Through Microstructural Changes Induced by Laser Surface Treatment" Materials 18, no. 23: 5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235410

APA StyleTwardowska, A., & Ślusarczyk, Ł. (2025). Improving the Friction-Wear Properties and Wettability of Titanium Through Microstructural Changes Induced by Laser Surface Treatment. Materials, 18(23), 5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235410