3.1. Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

The PVEL-AD [

20,

21,

22] is the largest-scale benchmark dataset for photovoltaic battery defect detection globally, jointly released by Hebei University of Technology and Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, aiming to provide a standardized evaluation platform for photovoltaic defect detection algorithms. This dataset is constructed based on electroluminescence (EL) imaging technology, covering various complex scenarios and defect types, containing over 30,000 images, of which 4500 are annotated. This paper selects seven types of defects for experimentation: crack, finger, black core, thick line, star crack, printing error, and short circuit. The paper divides 3600 images into training sets and 900 images into validation sets in a 4:1 ratio.

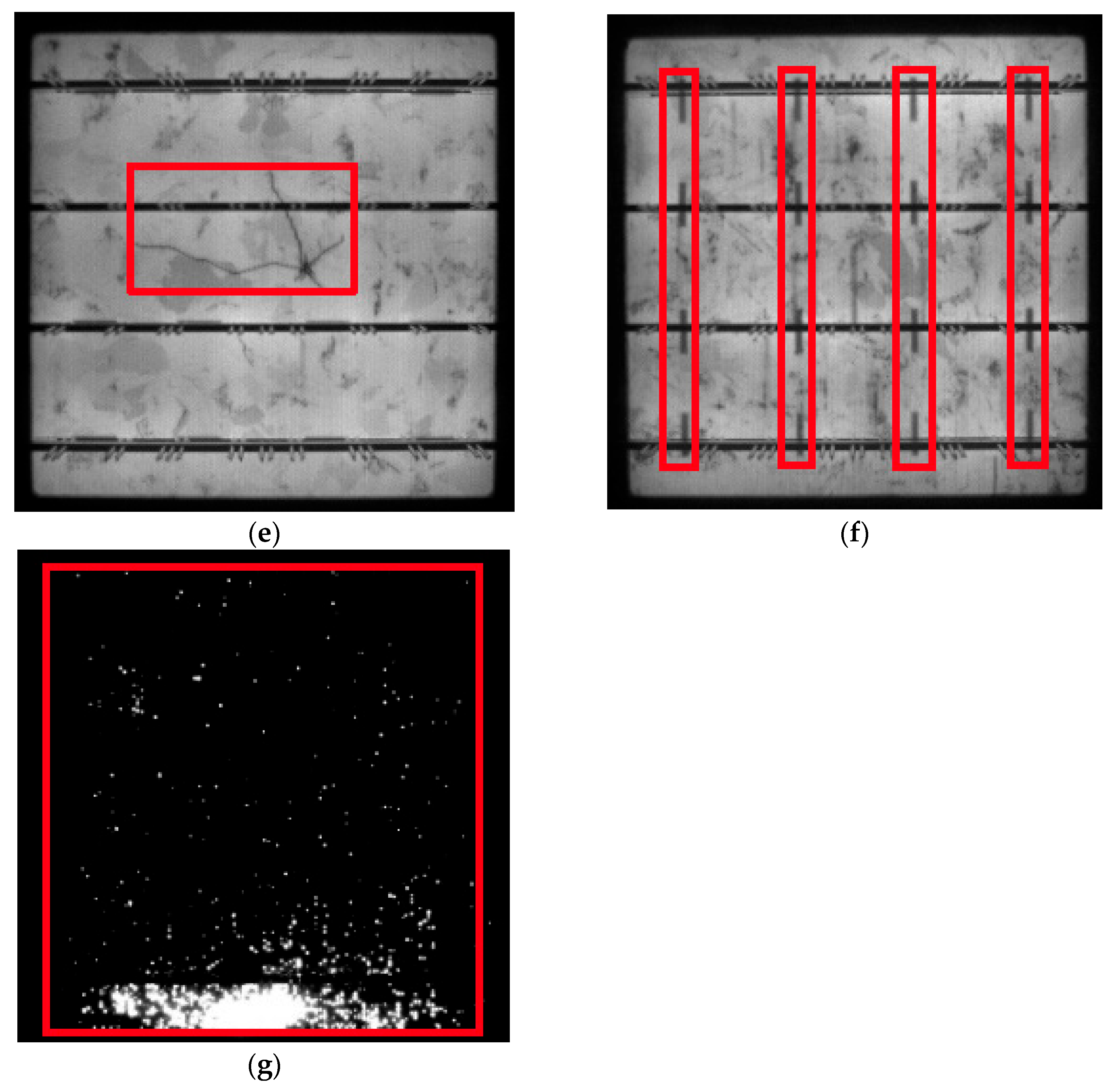

The dataset for surface defect samples is shown in

Figure 5. To clearly locate the defect area, red wireframes have been used in the figure to label the specific locations of defects in each sample, in order to visually distinguish the morphological differences between defects and normal areas.

1. Crack

The crack refers to fractures occurring in the silicon material inside the solar cell. The cracks detected in this article are mainly visible cracks, which are visible to the naked eye. The occurrence of cracks is often related to improper operation during production processes, such as improper force application during handling, welding, and lamination. The commonly used method for detecting cracks is EL detection. Areas with cracks cannot emit light, and will appear as clear black lines in the EL image.

2. Finger

The finger refers specifically to abnormalities occurring in the thin grid lines, resembling fingers, on the front side of the solar cell panel used for current collection. This type of defect manifests as broken, missing, or uneven grid lines. These defects are primarily caused by issues during the screen printing process, such as blocked screen plates, uneven squeegee pressure, or improper paste viscosity. It leads to discontinuous printing of the grid lines. This defect can be detected through EL inspection, where the broken grid areas will exhibit local dark areas.

3. Black Core

The black core, also known as black heart, manifests in EL images as an irregular, approximately circular dark area. The main reason is that the lifetime of minority carriers in the central zone of the cell is much shorter than that in the edge region.

4. Thick line

The thick line refers to the cell busbar, especially the main busbar or fine busbar, width exceeding the process specification and becoming too wide. The main cause of this defect is improper printing parameters, such as too little squeegee pressure, improper snap-off distance between the screen and the silicon wafer, etc. In addition, wear or damage to the screen busbar pattern can also lead to thick line defects, which manifest as obvious uneven thickness.

5. Star Crack

The star crack is a special form of cracks, typically radiating out from a central point, resembling a star or spider web. The main cause is the impact of point-like external forces on the solar cell during production or transportation, such as small protrusions on equipment or collisions with hard objects. When a local point is subjected to a large external force, this force will be released to the surrounding area, causing the silicon wafer to crack with that point as the center. Under EL detection, star crack will exhibit typical radial black patterns, and severe star cracks can be visible to the naked eye.

6. Printing Error

The printing error constitutes a broad category, referring to issues other than finger defects and thick lines in the screen printing process. These mainly include printing offsets, incomplete printing of back electrodes, and smudges. In EL inspection, printing errors can lead to uneven brightness and darkness in EL images.

7. Short Circuit

The short circuit refers to internal leakage in the solar cell, where the P-N junction is partially damaged, causing the current to be bypassed and unable to flow through the external circuit to perform work. In EL images, short circuits manifest as local or overall abnormal dark areas.

The above-mentioned defects are the focus of monitoring and prevention in the photovoltaic manufacturing industry. This article uses deep learning techniques to identify defective solar cells, ensuring the quality and long-term power generation reliability of the final photovoltaic modules.

Intersection over Union (IoU) is an algorithm that calculates the overlapping ratio between different images, primarily used for object detection. A higher IoU value indicates that the predicted box overlaps more with the real box. Therefore, its detection and positioning are more accurate. The calculation formula is shown in Equation (11).

The precision is the proportion of truly positive samples among those predicted as positive, and its calculation formula is shown in Equation (12).

The recall rate reflects the proportion of all true positive samples that were successfully predicted, as shown in Equation (13).

The Precision Recall (PR) curve is the evaluation of the performance in predicting positive categories. It takes accuracy as the vertical axis and recall rate as the horizontal axis, which is suitable for imbalanced category scenarios.

The F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, and its calculation formula is shown in Equation (14).

Mean Average Precision (mAP) is used to measure the performance of the target detection algorithm. It is obtained by the comprehensive weighted average of the Average Precision (AP) of all kinds of detection.

Here, AP averages all categories of Area Under the Curve (AUC), and the average accuracy is shown in Equation (16).

At the same time, mean Average Precision at IoU threshold 0.50 (mAP@0.5) is calculated as the average precision under different IoU thresholds, followed by taking the category average. Therefore, mAP@0.5 represents the average when the threshold is 0.5.

The confusion matrix is a table used to visually display the comparison between the prediction results of a classification model and the true labels. By using the confusion matrix, one can intuitively see the performance of the model in each category.

3.3. Experiment

The setting of the main hyperparameters is carried out under a unified framework. In terms of basic training, the training period (epoch) is set to 100 to ensure that the model fully converges. The batch size is set to 16. The input images size is 640 × 640 pixels, retaining sufficient defect detail features. The optimizer uses Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with momentum set to 0.937 to accelerate convergence and suppress oscillations. The weight decay coefficient is 0.0005, and L2 regularization is applied to prevent over-fitting. The learning rate (lr) adopts a linear decay strategy, with an initial learning rate of 0.01 and a final decay to 0.0001. Before training, three learning rate warm-up cycles are enabled. During this period, the momentum and bias learning rates are set to 0.8 and 0.1, respectively, to achieve stable initialization in the early stages of training.

In response to the multi-tasking characteristics of object detection, fine adjustments are made to the weight of the loss function. The bounding box regression loss gain is set to 7.5. The classification loss (cls) is set to 0.5, and the distribution focus loss (dfl) gain is set to 1.5 to optimize the probability distribution modeling of the bounding box. The data augmentation adopts a comprehensive approach, with color space perturbations covering hue, saturation, and brightness, geometric transformations including translation and scaling, and horizontal flipping with a probability of 0.5. Meantime, to enhance the model’s generalization ability and detection accuracy, four training images are spliced into one, simulating complex scenes, reducing the possibility of over-fitting, and enhancing the model’s generalization ability in complex environments, as well as strengthening the detection effect on small and occluded targets.

Figure 7 is the enhanced dataset. Mosaic enhancement is turned off in the last 10 rounds of model training. In the inference and validation phase, the IoU threshold for non-maximum suppression is set to 0.7, and automatic mixed precision training is enabled to improve training speed and control graphics memory usage. In

Figure 7, the numbers 0 to 6 and their corresponding boxes are used to identify and distinguish different types of defects. Their specific meanings are: 0 represents crack, 1 represents finger, 2 represents back core, 3 represents thick line, 4 represents star crack, 5 represents printing error, and 6 represents short circuit.

Figure 8 shows the label images file after training. The images show the visual images related to labels in the data set and give examples of images with information such as the location and category names of different categories of targets, such as crack, finger, and thick line. It is used to visually present the labeling situation in the data set and help users quickly understand the content and style of labeling.

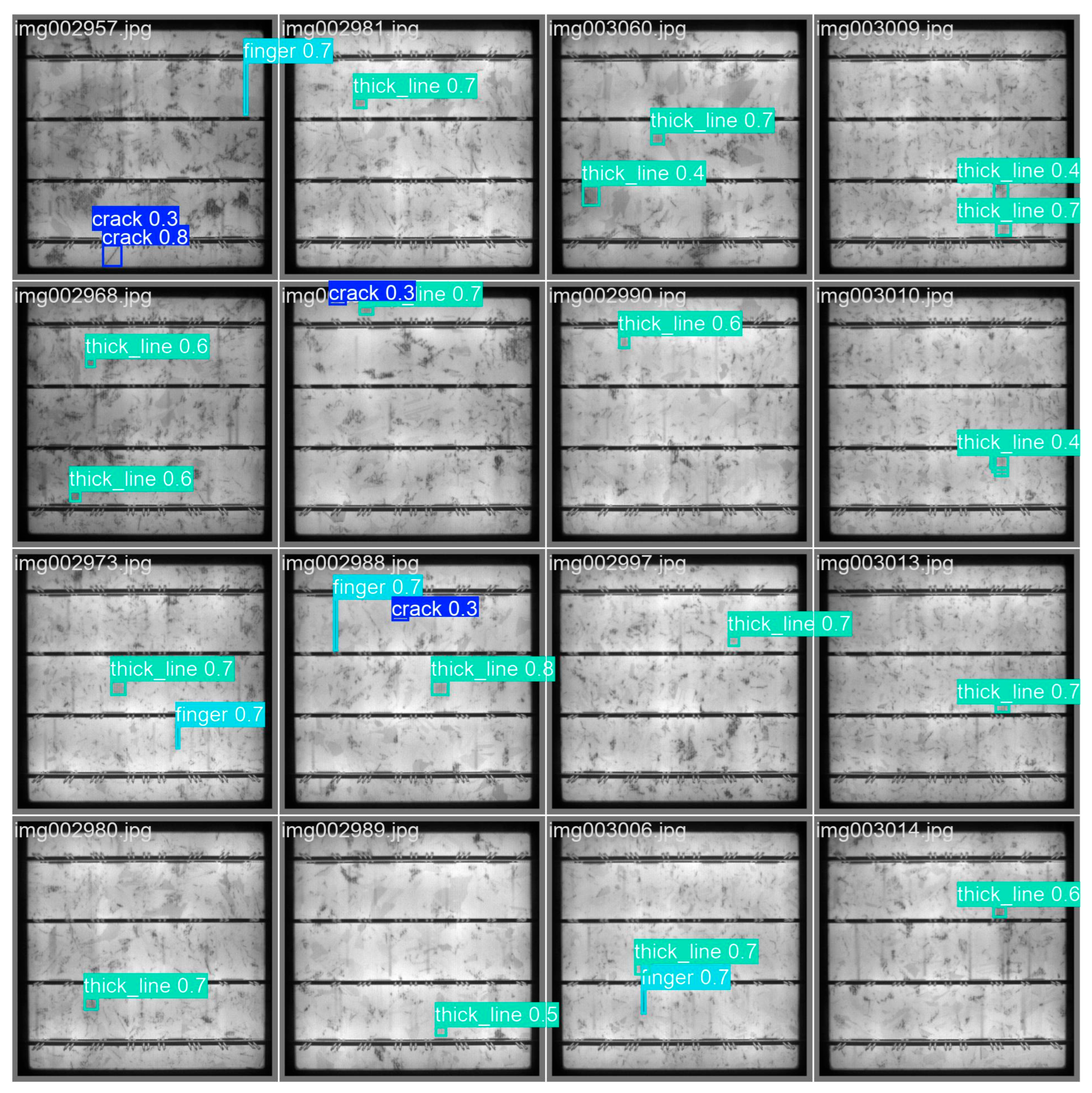

Figure 9 is the image of the test results. After testing by the AE-YOLO model, many surface defects were found. These defects are marked in the image as bounding boxes and each bounding box corresponds to a specific defect type, location, and confidence score.

The AE-YOLO model exhibits excellent detection performance in dense defect areas. It not only achieves precise defect localization, but also outputs correct category labels and high confidence, verifying its excellent practical performance.

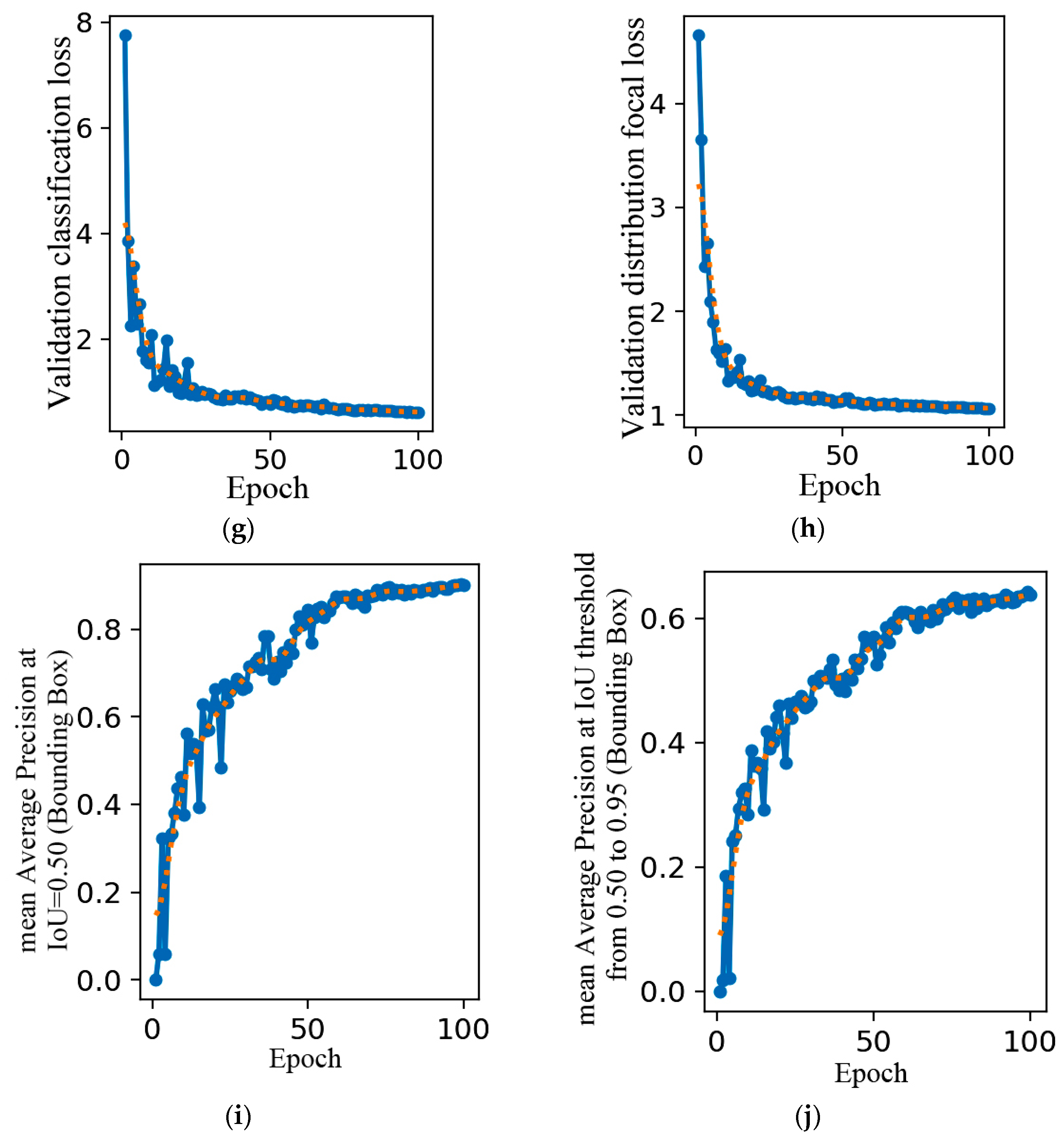

The training loss and evaluation metrics of AE-YOLO model are shown in

Figure 10, which are used to analyze its convergence and detection performance.

In

Figure 10a, the initial bounding box loss is about 3.5, which shows a rapid downward trend during training iterations and ultimately stabilizes in the low loss range close to 0.5. It indicates that the model can reduce the spatial deviation between the predicted box and the real defect area. The boundary fitting ability for irregular shaped defects such as crack and thick line is constantly improving.

Figure 10b reflects the classification accuracy of the model for various defects, such as crack, black core, and short circuit. The initial loss is about 5, which rapidly decreases and tends to stabilize during the training process, eventually approaching 0. This indicates that the model can learn the feature differences in different defects. When facing the complex background, the confusion in classifying various types of defects is reduced, and the confidence and accuracy of classification are continuously optimized. It reflects the increasing ability of the model to distinguish multiple types of defects.

Figure 10c is an indicator used to measure the model’s ability to handle class imbalance when classifying each prediction box into multiple categories. The initial loss is about 4.0, which shows a significant downward trend with training iterations and eventually stabilizes below 1.0. It indicates that the model can grasp the distribution characteristics of the bounding box when dealing with the multi-scale distribution of defects. This reduces prediction fluctuations caused by differences in defect scale, further enhancing the detection robustness of the model in complex scenarios.

In the initial stage, the precision curve fluctuates and the value is relatively low in

Figure 10d. It is because at the beginning of training, the parameters are initialized randomly, and its ability to extract features from data and classify them is weak. The model incorrectly predicts many background areas as targets, resulting in the low accuracy. Then, it shows an overall upward trend, but there are still fluctuations. As training progresses, the model begins to learn some basic features of surface defects and gradually distinguishes between targets and backgrounds. However, due to the potential complexity and noise in the training data, the model performs unstably on certain batches of data, causing fluctuations. In the later training stage, it tends to stabilize, with the value remaining at a relatively high level, close to 0.8. At this point, the model has fully learned the features in the data and can accurately determine whether a target exists. It can identify various complex defects, such as crack, finger, and star crack, and the number of false positive samples has been reduced, thus maintaining a high and stable precision.

From

Figure 10e, it can be seen that the recall rate is very low in the initial stage. When the model starts training, its ability to recognize the target is limited, and many real surface defects cannot be detected, resulting in a large number of false negative samples. In the middle training stage, the recall rate rises rapidly. As the model continues to learn, it can recognize more surface defect features, and its detection ability gradually increases. The model starts to detect some previously missed surface defects, and the number of false negative samples decreases. At last, the recall rate growth slows down and tends to stabilize, increasing to above 0.9, enabling more comprehensive detection of various surface defects. The model has achieved high accuracy in detecting the target, but there may still be some extreme cases where the target cannot be detected, such as thick line and crack.

Figure 10f is used to measure the accuracy of the model in locating the boundary boxes of photovoltaic panel defects on the validation set. The initial loss value is about 4.0, which rapidly decreases during training iterations and eventually stabilizes within the range of 1.0–1.5. This indicates that it can fit its true bounding box on the validation set. The generalization ability of bounding box localization has been validated, providing support for accurate spatial localization of defects.

Figure 10g reflects the accuracy of the model in classifying various types of defects on the validation set. The initial loss is about 8.0, then rapidly decreases and tends to stabilize. It can stably distinguish the differences between various types of defects. The consistency in confidence and accuracy in distinguishing defect categories on the validation set reflects the model’s generalization ability in multi class defect classification tasks.

Figure 10h is used to measure the accuracy of the model’s predicted bounding box position distribution, which focuses on the positioning accuracy. Its initial loss is approximately 4.5, which significantly decreases with training iterations and eventually stabilizes below 1. There are significant scale differences in defects of photovoltaic panels, ranging from small fine cracks to larger thick line, with complex distribution characteristics. The stable decrease in this loss indicates that it can grasp the distribution of bounding boxes of defects at different scales on the validation set. Even when faced with untrained defect scale samples, it can reduce prediction fluctuations and verify the model’s generalization robustness in multi-scale defect detection scenarios.

Regarding

Figure 10i, in the initial stage, the mAP@0.5 is relatively low. Due to the poor matching between the predicted bounding boxes and the true boxes, many predicted boxes have the IoU with the true boxes less than 0.5, resulting in a lower average precision. In the middle training stage, mAP@0.5 increases significantly. As the model learns, the matching between predicted boxes and true boxes gradually improves. It can locate the position and range of surface defects, enabling more predicted boxes to have the IoU with the true boxes exceeding 0.5. At last, mAP@0.5 tends to stabilize and eventually reaches 0.903. At this point, it has achieved good detection performance with the IoU threshold of 0.5. The model can stably detect and locate various surface defects, including small-sized defects such as thick line and star crack.

Regarding

Figure 10j, in the initial stage, the mAP@0.5:0.95 is very low. This is because the metric considers a higher IoU threshold, which demands higher detection accuracy from the model. At the beginning of training, the IoU is low, so the average precision is at a low level. In the middle training stage, mAP@0.5:0.95 gradually increases, but the rate of increase is relatively slow. As the model learns, the degree of matching between the predicted boxes and the true boxes continues to improve, but it is still difficult to meet the higher IoU threshold. The model needs to locate surface defects more accurately and predict the shape and position of defects more precisely. In the later training stage, mAP@0.5:0.95 tends to stabilize and exceeds 0.6. At this point, the model can maintain a certain detection performance under different IoU thresholds and accurately identify the above seven types of defects.

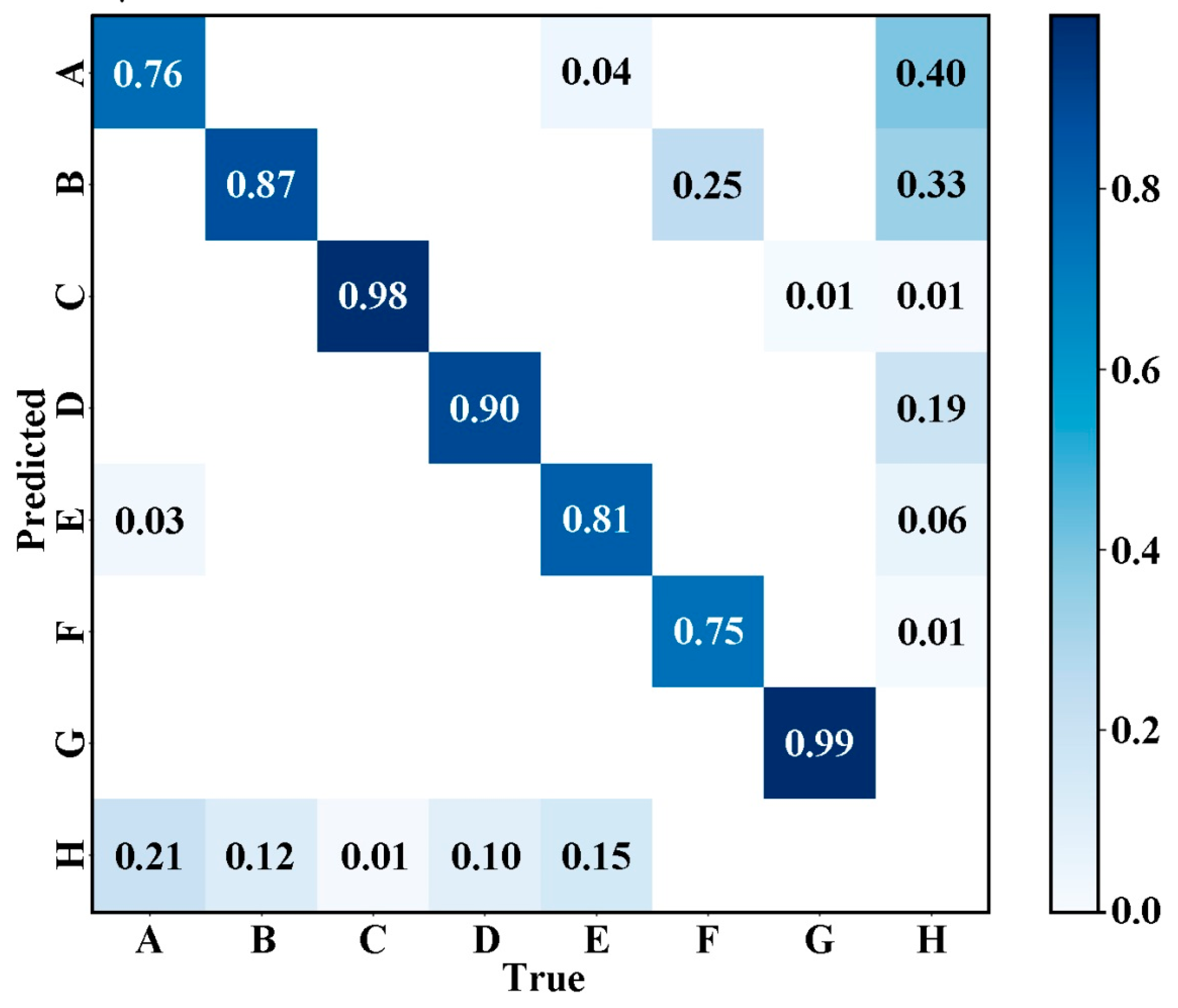

Figure 11 shows the normalized confusion matrix of the AE-YOLO model on the PVEL-AD dataset. It used to visually evaluate the classification performance of the model for various types of defects. The horizontal axis represents the true defect category, and the vertical axis represents the model predicted category. The value of each cell represents the normalized proportion of the predicted results for that category, with dark blue indicating a high proportion and light colors indicating a low proportion. From the main diagonal, the model has a relatively high overall accuracy in identifying various types of defects. For example, the accuracy of category C is 0.98, category G is 0.99, the accuracy of categories B, D, E, and F are also 0.87, 0.90, 0.81, and 0.75, respectively, and category A is 0.76. Therefore, the model has strong discriminative ability for most defect categories. The values of non-main diagonals reflect the confusion of categories. The values above the main diagonal indicate the proportion of misclassifications where the true category is a certain category but is predicted as another category. For example, the proportion of true E being misclassified as A is 0.04, the proportion of true F being misclassified as B is 0.25, and so on. These values reflect the degree of confusion between different defect categories in the model, with smaller values indicating better category discrimination. The value below the main diagonal indicates the proportion of missed detections where the true category is a certain category but is mistakenly classified as H. The proportion of true A being misjudged as H is 0.21, the proportion of true B being misjudged as H is 0.12, etc. These values reflect the missed detection risk of various types of defects in the model, and the smaller the value, the more reliable the model’s identification of such defects. Overall, most defect categories can be identified and category confusion can be effectively controlled, indicating the robustness and reliability of the model in detecting defects under multi-scale and complex backgrounds.

In the experimental environment of this paper, relevant experiments are conducted based on the PyTorch (Version: 2024.3.4, Community Edition, Manufacturer: JetBrains s.r.o., Prague, Czech Republic) deep learning framework. After 100 iterations of training, AE-YOLO and all comparison methods obtained the following experimental results. The results are shown in

Table 2.

Through the analysis of experimental data, the following main conclusions can be drawn. (1) mAP@0.5: The YOLO series models overall performed the best, with YOLOv5s and YOLOv11 significantly outperforming other models. SSD performed decently with smaller input sizes but still lagged behind the YOLO series. In contrast, the accuracy of Faster R-CNN was significantly lower, as cracks often appear as slender, curved, or irregular geometric shapes, and Faster R-CNN relies on rectangular bounding boxes for localization, which makes it difficult to precisely fit such targets, leading to large IoU calculation errors. Cracks have a wide range of length and width variations, requiring the model to have multi-scale perception capabilities, but fixed-size anchor boxes cannot effectively cover, resulting in low-quality candidate regions generated by the Region Proposal Network (RPN). The redundancy of two-stage object detection deserves attention in object detection tasks. EfficientDet, as a general object detection model, is lightweight and efficient, extracting high-level semantic features through multiple down-sampling operations. (2) Computational efficiency: EfficientDet had the lowest computational demand but sacrificed accuracy. YOLOv11 and AE-YOLO maintained a high mAP@0.5 (0.892~0.903) with moderate computational demand, demonstrating a better balance. Meantime, the AE-YOLO has a computational complexity of 5.3 GFLOPs, significantly lower than the original YOLOv11′s 6.4 GFLOPs, which theoretically confirms the effectiveness of its lightweight design. Faster R-CNN, despite having extremely high computational demand (370.26G FLOPs), had the worst performance, indicating its low resource utilization efficiency. (3) Parameter Efficiency: The AE-YOLO has the fewest parameters, only 2.1M, which is an 18.9% reduction compared to the standard YOLOv11 model. (4) mAP@0.5:0.95: The AE-YOLO model achieved the mAP@0.5:0.95 value of 0.63813 on the PVEL-AD dataset. It is not only better than the original YOLOv11n model’s 0.63422, but also significantly higher than YOLOv5s’ 0.60481, YOLOv7 tiny’s 0.5782, and traditional architectures such as SSD and Faster R-CNN. This result fully validates the effectiveness of the collaboration between the Adown module and the ECA mechanism. (5)Inference speeds (ms/frame): When the input size is 640 × 640 pixels, the AE-YOLO model achieves an inference speed of 259.56 FPS, which is slightly lower than the original YOLOv11 (297.98 FPS), but still significantly higher than other comparison models (Faster R-CNN’s 52.10 FPS, SSD’s 97.20 FPS, etc.), fully meeting the frame rate requirements for industrial real-time detection. The slight decrease in inference speed is mainly due to the additional computational path introduced by the ECA, but its gains in accuracy (mAP@0.5 improved to 90.3%) and feature discrimination ability are more significant. (6) Energy efficiency (mAP@0.5/Watt): The energy efficiency of AE-YOLO model is 0.0367, which is basically the same as the original YOLOv11′s 0.0371, indicating that the energy efficiency level is maintained while significantly improving the detection accuracy. Horizontal comparison shows that the energy efficiency performance of AE-YOLO is significantly better than traditional architectures such as Faster R-CNN, SSD, and EfficientDet. Although YOLOv7 tiny has a higher energy efficiency value of 0.0779, its detection accuracy is 4.4% lower than AE-YOLO. This comparison highlights the good balance achieved by AE-YOLO between accuracy and energy efficiency. The energy efficiency analysis further validated the effectiveness of the improvement strategy. The Adown reduces computational overhead by optimizing the feature compression process, while the ECA achieves feature calibration at minimal cost. The synergistic effect of the two improves performance while maintaining energy efficiency competitiveness.

To explore the performance characteristics of the AE-YOLO model under the COCO standard evaluation system, this study systematically analyzed the detection results of seven typical defects based on COCO evaluation indicators. The quantitative analysis data of different types of defects are detailed in

Table 3.

Based on the evaluation results in

Table 3, the performance of the AE-YOLO model on the PVEL-AD dataset is as follows: mAP value is 89.9%, mAP@0.5 is 89.1%, and mAP@0.75 is 87.5%. The detection performance of medium and large target defects is 56.1% and 34%, respectively, fully verifying the advantage of the Adown module in preserving fine-grained features. The relatively low global average mAP score is mainly attributed to the lack of specific size targets in certain defect categories during the evaluation process. The short circuit lacks medium-sized targets (mAP_m = nan), while the finger and print error both lack large instances (mAP_l = nan). According to the COCO evaluation protocol, these missing dimension annotation samples result in the inability to calculate the corresponding size box indicators, thereby affecting the overall average calculation. This phenomenon reflects the limitations of the dataset rather than fundamental model performance issues.

3.8. Discussions

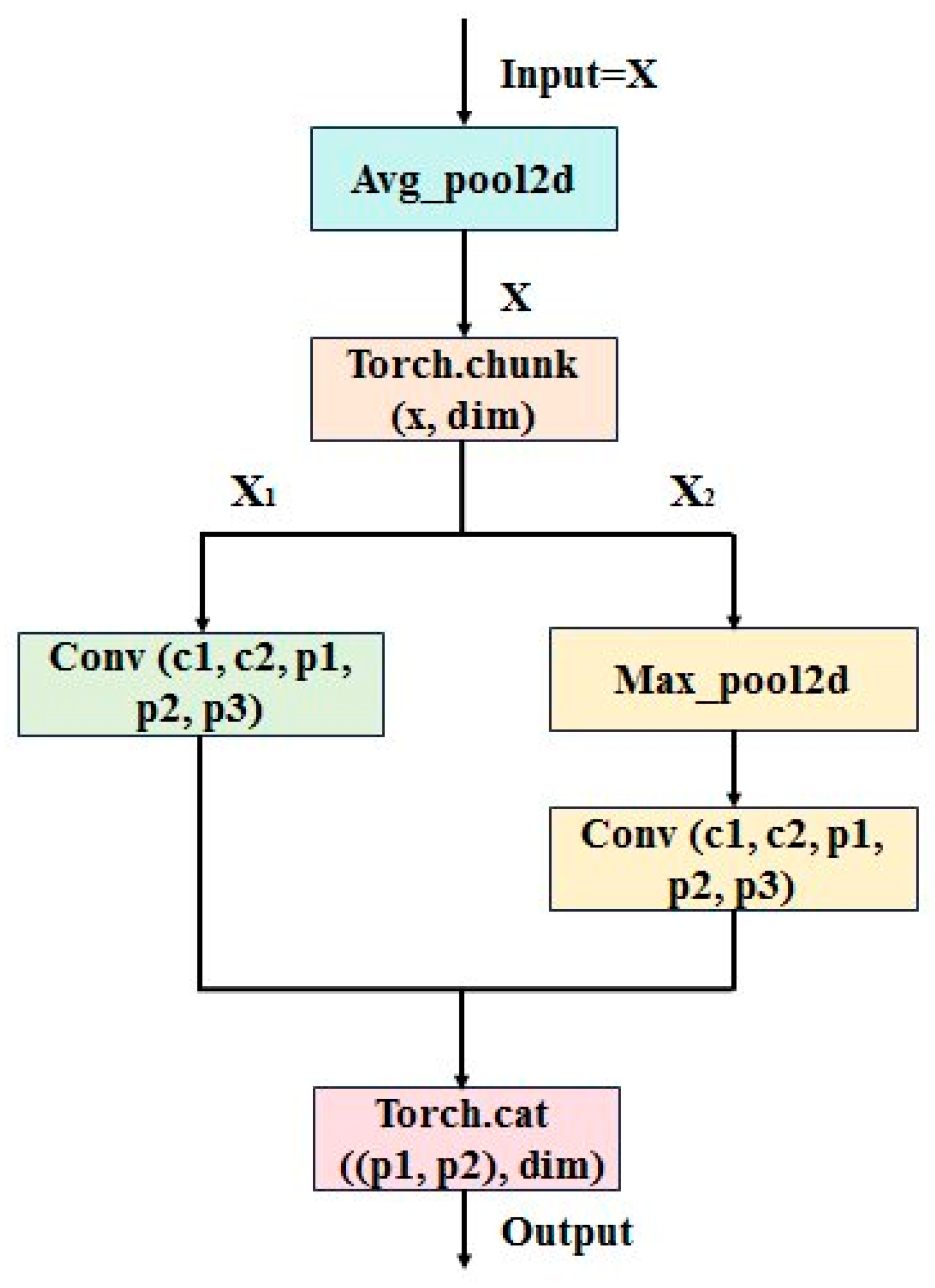

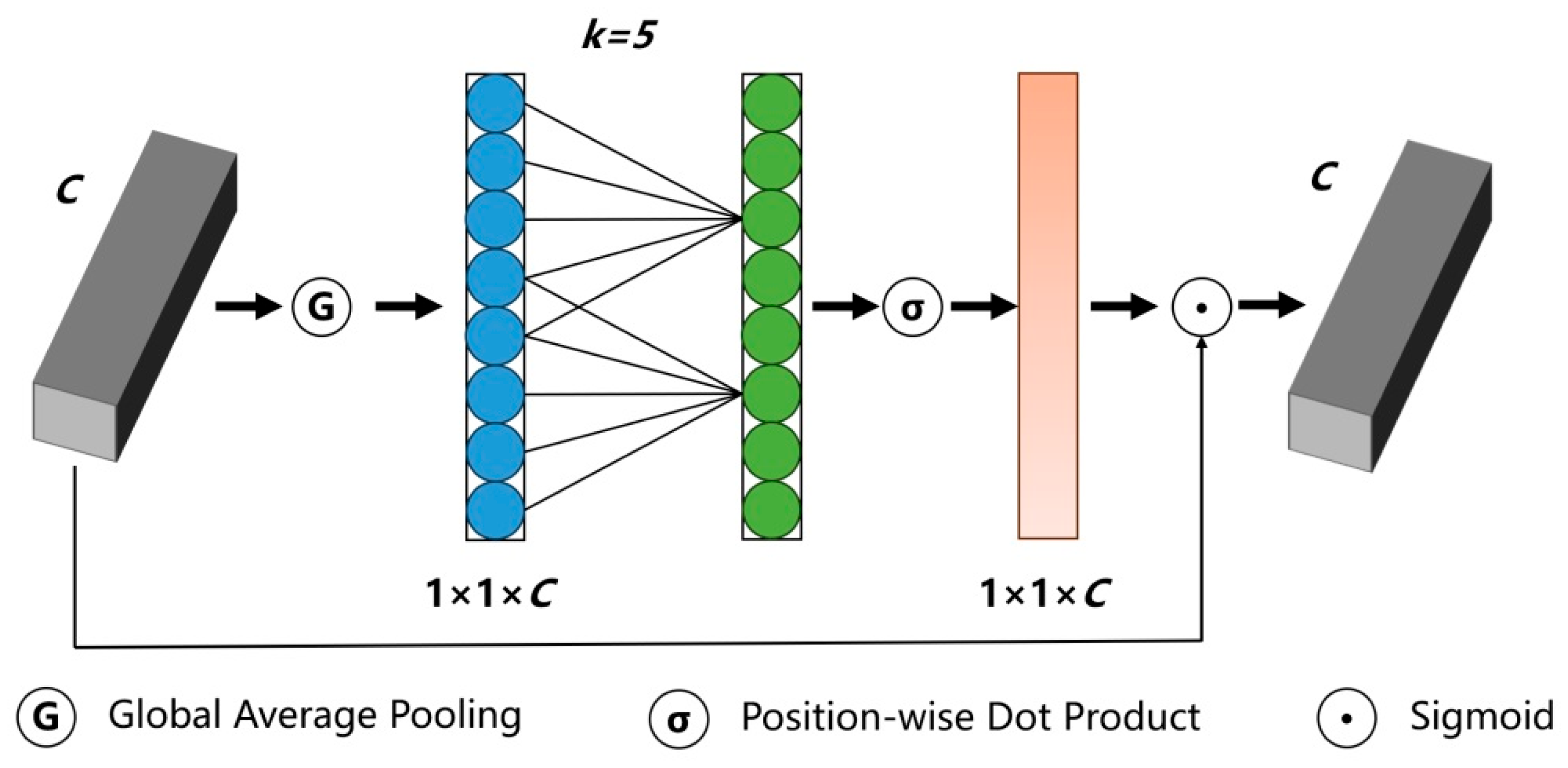

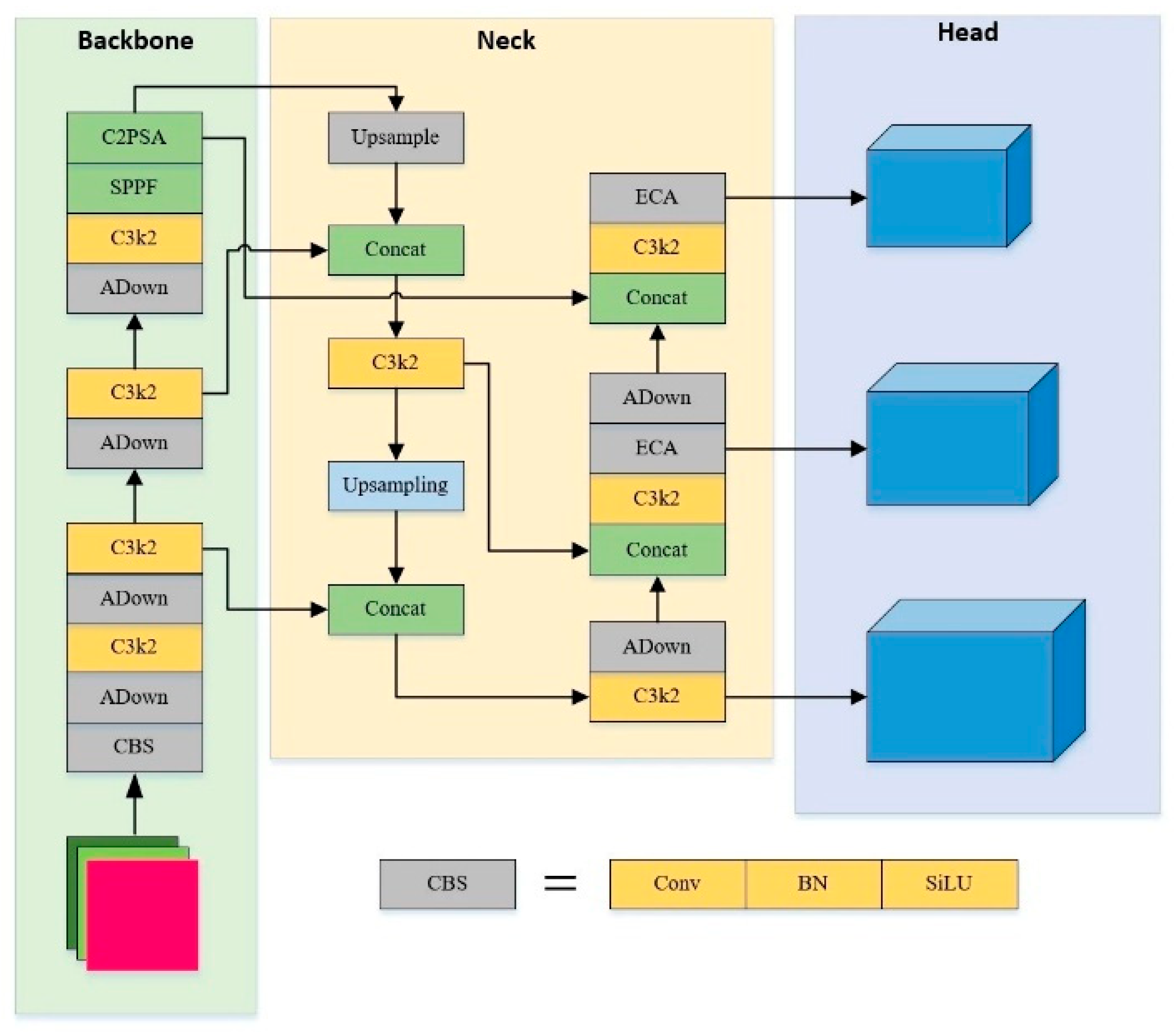

This paper proposes the AE-YOLO based on YOLOv11 to solve the problems of multi-scale missed detection in surface defect detection of photovoltaic panels. By introducing the Adown and ECA, it achieves collaborative optimization of model performance and efficiency.

(1) Lightweight and efficiency. The improved model achieves the mAP@0.5 value of 90.3% on the PVEL-AD dataset with 5.3G of computation and 2.1M parameters, showing an 18.9% reduction in parameter quantity and a 17.2% decrease in computation compared to the original YOLOv11, verifying the effectiveness of the Adown module in feature compression and information retention, providing a feasible solution for edge device deployment.

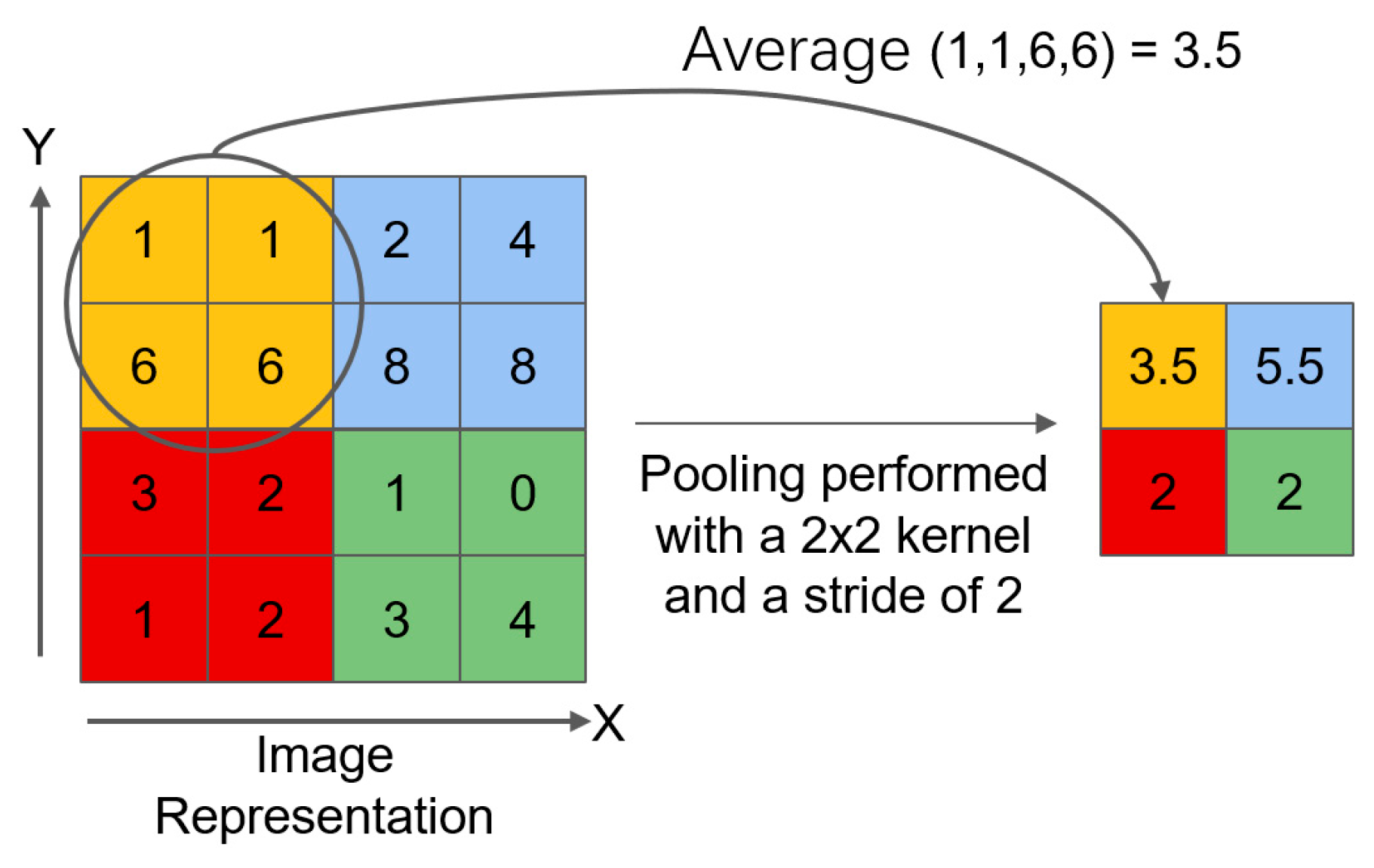

(2) Enhanced multi-scale defect detection capability. The Adown alleviates the problem of fine-grained feature loss caused by traditional down-sampling through a dual-path design that integrates average pooling and maximum pooling. The ECA dynamic ally calibrates key channel features, which improves the detection accuracy of irregular scale defects such as crack.

(3) Module collaborative effect verification. Ablation experiments show that the combination gain of the Adown and ECA exceeded the improvement of a single module. It confirms the complementarity of spatial adaptive down-sampling and channel attention mechanism, which collaboratively optimize the multi-level feature expression.

(4) Industrial application value. Compared with traditional models such as Faster R-CNN, EfficientDet, and SSD, AE-YOLO has significantly improves mAP@0.5 and FPS. By maintaining real-time inference speed, it solves the complex background noise and multi-type defect detection requirements.

(5) Compared with existing research, the AE-YOLO model exhibits certain advantages on the PVEL-AD dataset. As the creator of this dataset, although reference [

20] did not provide specific mAP values, it established a benchmark framework for performance comparison. Compared to the traditional feature engineering method Center Pixel Gradient Information to Center-Symmetric Local Binary Pattern (CPICS-LBP) proposed in reference [

21], the AE-YOLO end-to-end detection framework demonstrates significant advantages of deep learning. Compared with the most comparable Bidirectional Attention Feature Pyramid Network (BAFPN) [

22], the AE-YOLO model mAP@0.5 increase by 2.23%, while significantly reducing the computational load from 370.2G FLOPs to 5.3G FLOPs. This system comparison validates the dual breakthroughs of AE-YOLO in accuracy and efficiency, and the collaborative optimization of the Adown module and the ECA mechanism provides a better solution for defect detection in photovoltaic panels.

The future work will focus on: introducing a dynamic down-sampling rate adjustment strategy to further adapt to defect scale changes. To enhance the joint modeling capability of spatial channel features, a three-dimensional attention mechanism is introduced. To address the data scarcity dilemma faced by small sample defect categories, semi supervised learning methods are combined to break through this bottleneck [

23]. At the same time, exploring the adaptability of the proposed algorithm in complex dynamic scenarios can draw on the adaptive signal classification continuous learning method based on selective multi-task collaboration to enhance the flexibility and robustness of the algorithm. Given the current model training’s high dependence on labeled datasets, future research will focus on achieving functional breakthroughs in scenarios with few samples or weak labeling, such as referencing the practical experience of Virtual Signal Large Model (VSLM) [

24] in few-sample broadband signal detection and recognition tasks. Furthermore, the issue of label noise cannot be ignored, as it may severely impair the learning performance of the model or even render it ineffective. The next step will focus on researching coping strategies.