Architecting Highly Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Flexible Phase Change Materials for Directed Thermal Management of Cylindrical Li-Ion Batteries

Highlights

- The hybrid 1D/3D carbon aerogel (CA) formed by combining 1D CNTs and 3D EG has a more optimized structural alignment than the single 3D EG-based CA as the CNTs enhance interlayer connectivity and guide directional pore arrangement;

- The hybrid 1D/3D-based FPCM demonstrated significantly enhanced anisotropic thermal conductivity: a 16.7% increase in axial thermal conductivity and a 5.0% increase in radial thermal conductivity compared to the single 3D-based FPCM;

- When applied to a cylindrical Li-ion battery, the hybrid FPCM effectively reduced the maximum battery-surface temperature by 13.1 °C and lowered the average surface temperature by 13.6 °C during the phase-change thermal-management stage.

- This work provides a scalable and effective strategy for designing high-performance anisotropic thermal-management materials, which can be tailored for high-power-density Li-ion batteries and other compact electronics with directional heat dissipation needs;

- The hybrid 1D/3D skeleton design overcomes the limitations of single-dimensional conductive networks, offering a new pathway to enhance thermal conductivity anisotropy beyond current upper limits;

- The developed FPCM maintains excellent flexibility, thermal stability, and energy storage capacity, making it suitable for practical applications in complex and flexible electronic devices.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

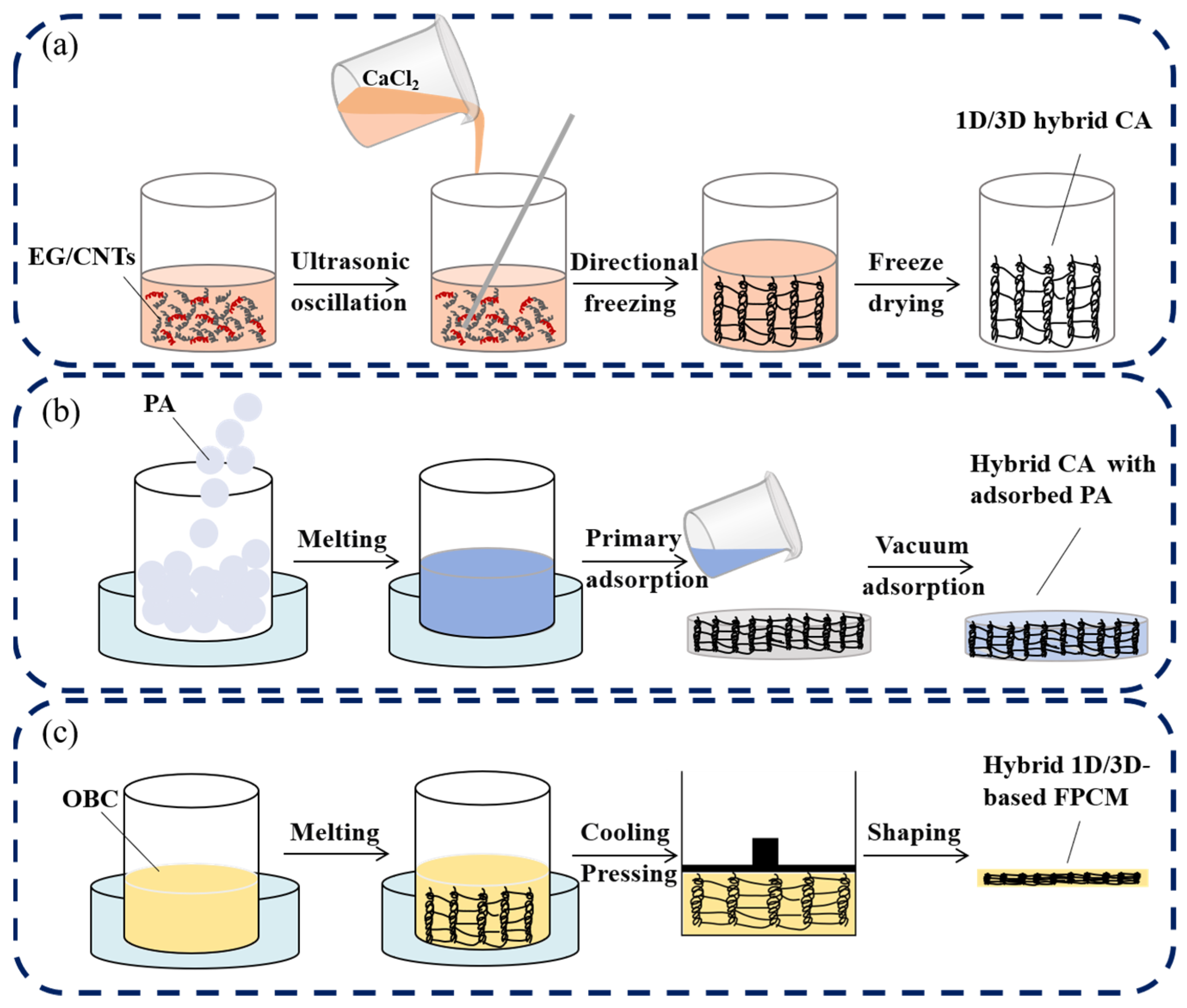

2.2. Preparation of 1D/3D Hybrid CA

2.3. Preparation of Hybrid 1D/3D-Based FPCM

2.4. Characterizations

3. Results

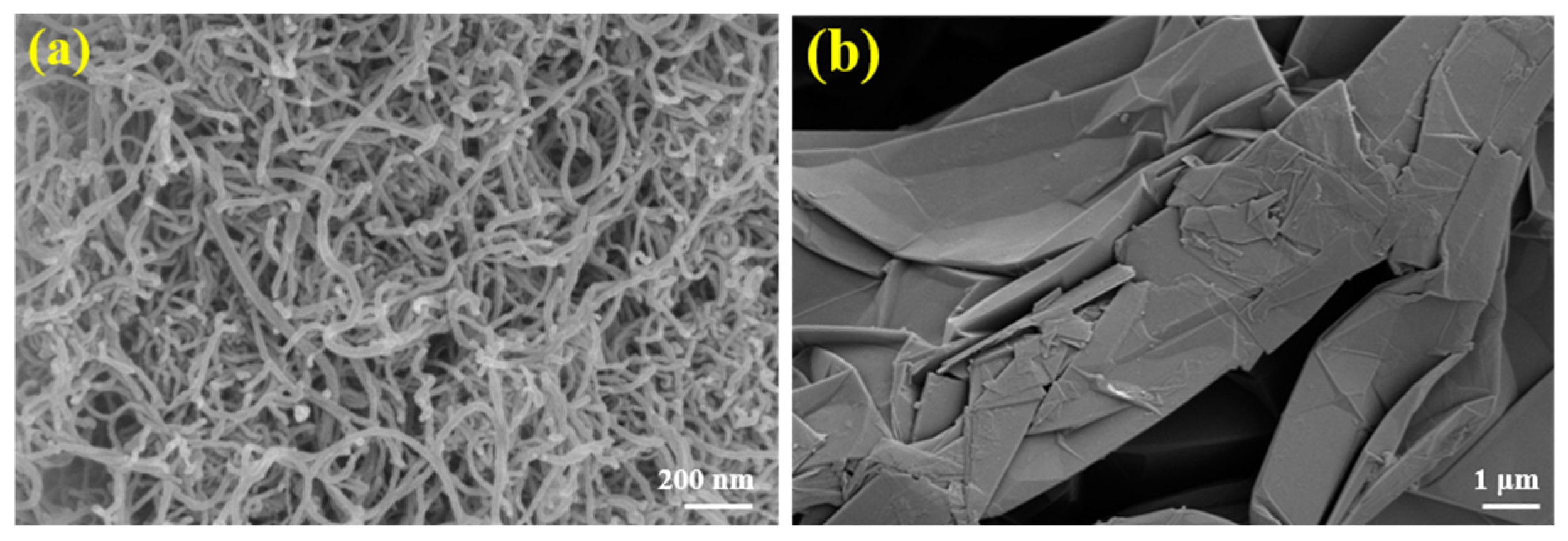

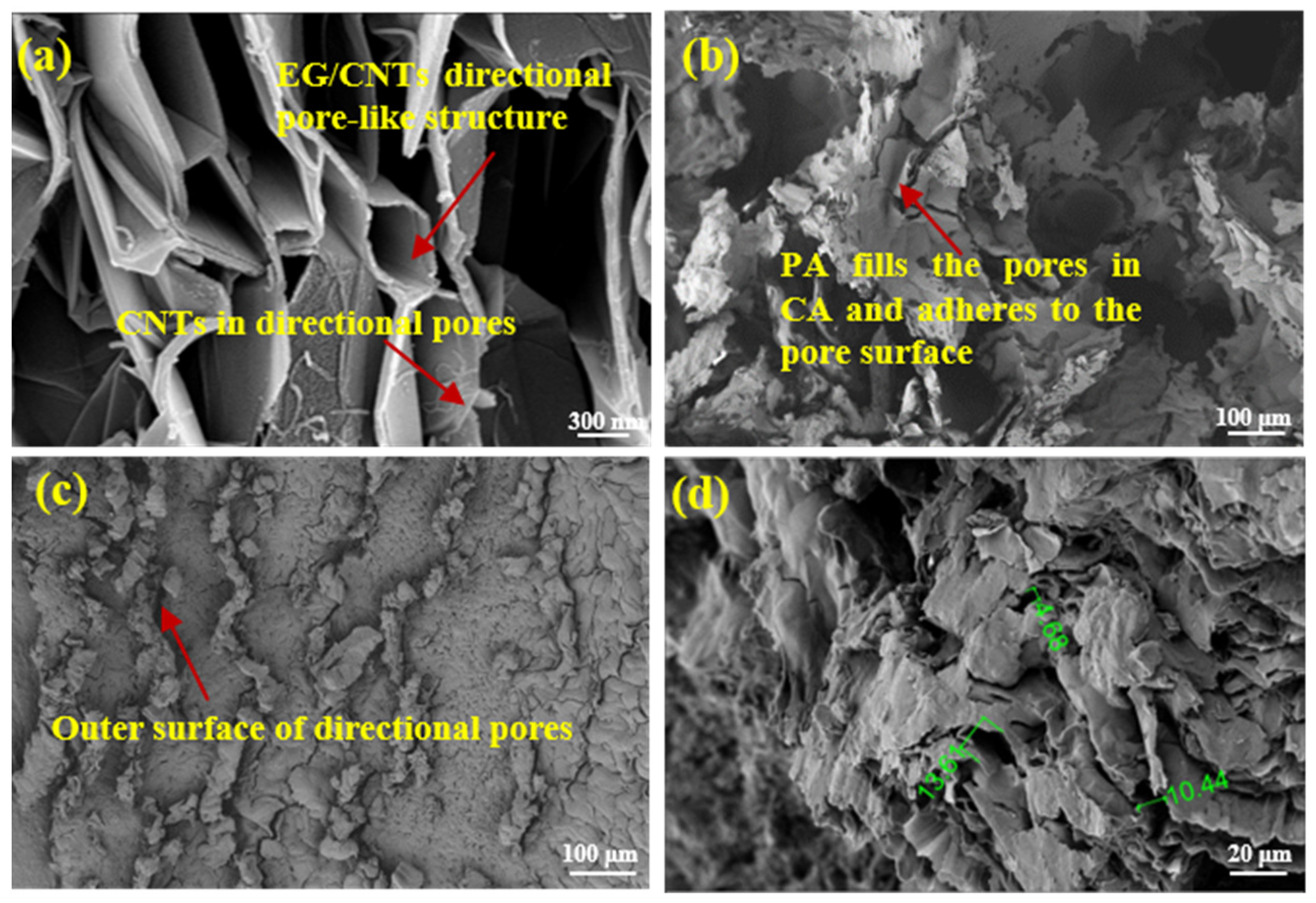

3.1. Microstructural Morphology Analysis

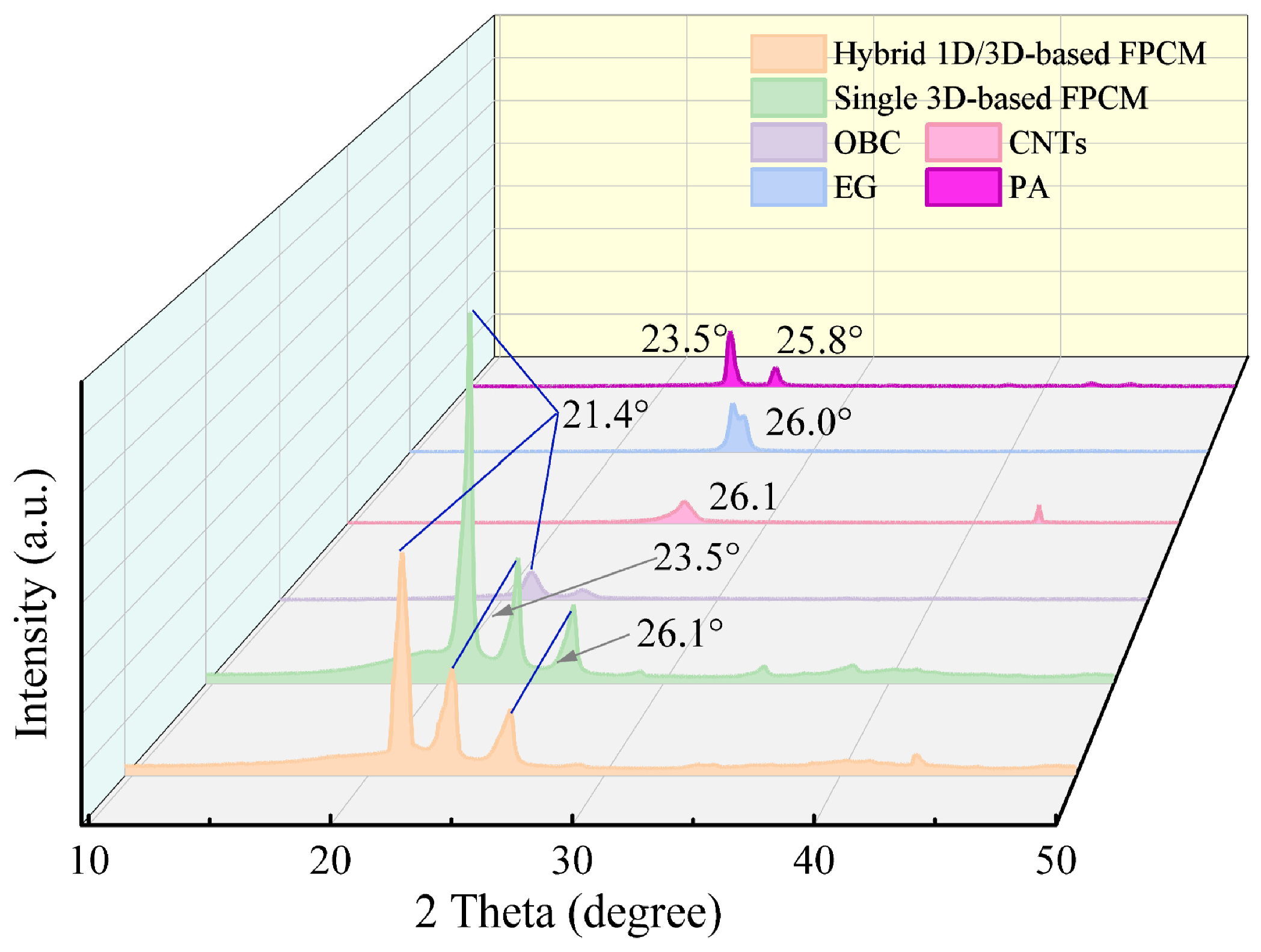

3.2. Chemical Composition Analysis

3.3. Phase-Change Property Analysis

3.4. Thermal Conductivity Analysis

3.5. Thermal Stability Analysis

3.6. Flexibility Analysis

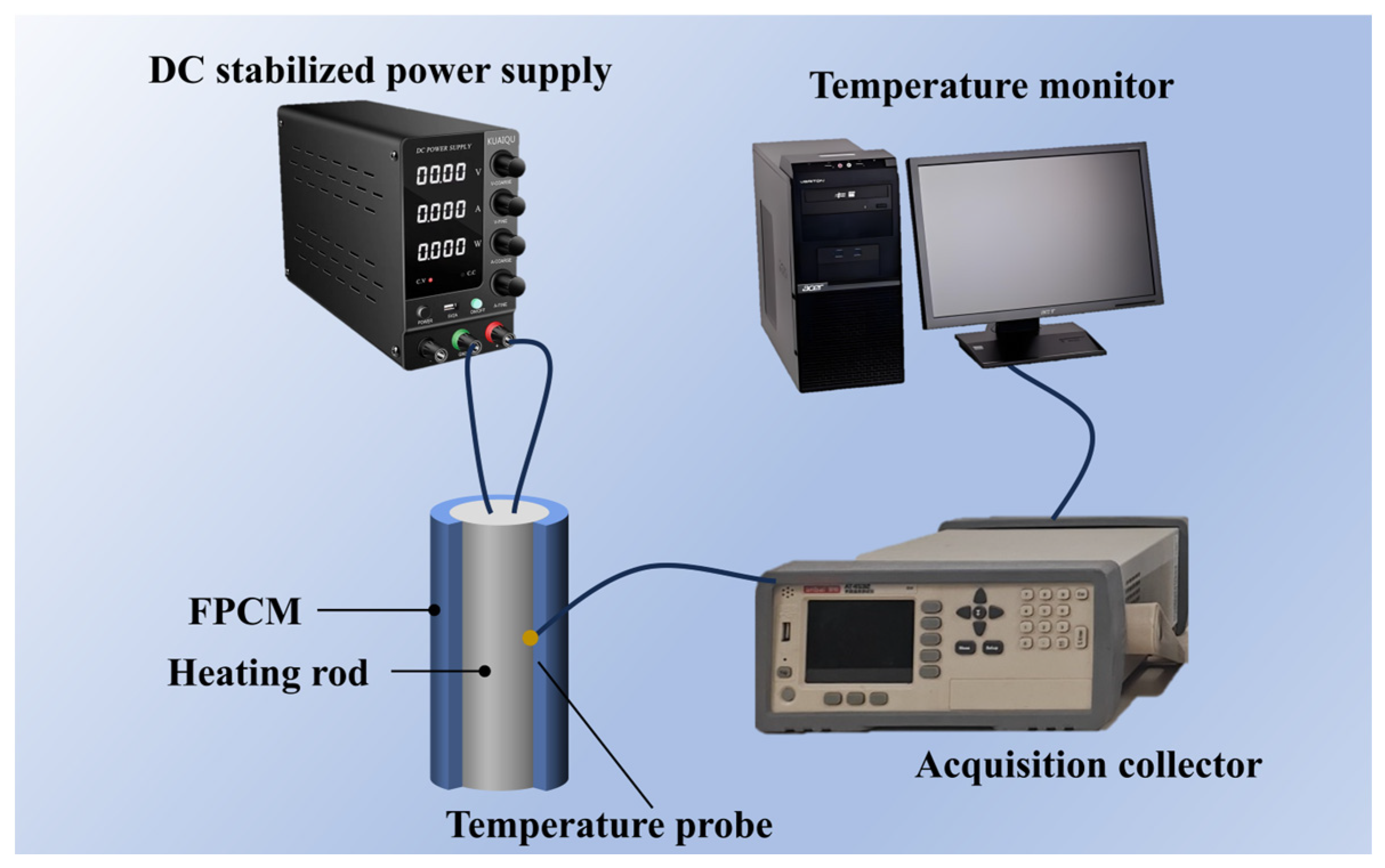

3.7. Anisotropic Thermal-Management Capability Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The hybrid CA synergistically combines the robust 3D framework of expanded graphite with the high orientation capability of 1D carbon nanotubes, yielding a thermally conductive skeleton with superior structural alignment compared to CA derived solely from EG.

- (2)

- Owing to the optimized skeleton, the resulting FPCM exhibits a substantially enhanced thermal conductivity anisotropy. Specifically, compared to its 3D CA-based counterpart, the radial thermal conductivity increased by 5.0%, while the axial thermal conductivity was significantly improved by 16.7%.

- (3)

- The hybrid 1D/3D-based FPCM maintains considerable latent heat capacity, excellent shape stability, and superior flexibility, ensuring reliable performance under practical conditions.

- (4)

- When applied to cylindrical Li-ion batteries, the material demonstrates exceptional effectiveness in directed thermal management. It achieved a substantial reduction in the battery’s average surface temperature by 13.6 °C during the phase-change thermal-management stage, effectively mitigating localized overheating.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiang, C.Q.; Wu, C.W.; Zhou, W.X.; Xie, G.F.; Zhang, G. Thermal transport in lithium-ion battery: A micro perspective for thermal management. Front. Phys. 2022, 17, 13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.M.; Ke, X.Y.; Yuan, C. Modeling the effects of state of charge and temperature on calendar capacity loss of nickel-manganese-cobalt lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2022, 49, 104105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.H.; Jin, H.L.; Duan, C.G.; Gao, Y.B.; Nakayama, A.; Liu, C.L. Simulation study on heat dissipation of a prismatic power battery considers anisotropic thermal conductivity in air cooling system. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 55, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.L.; Jiang, T.; Shang, K.; Xu, B.; Chen, Z.Q. Heat and mass transfer performance of proton exchange membrane fuel cells with electrode of anisotropic thermal conductivity. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 182, 121957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Ai, W.L.; Marlow, M.N.; Patel, Y.; Wu, B. The effect of cell-to-cell variations and thermal gradients on the performance and degradation of lithium-ion battery packs. Appl. Energy 2019, 248, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, X.L.; Negnevitsky, M.; Zhang, H.Y. A review of air-cooling battery thermal management systems for electric and hybrid electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2021, 501, 230001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, L.; Tang, Y. A review on the liquid cooling thermal management system of lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Energy 2024, 375, 124173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Experimental-numerical studies on thermal conductivity anisotropy of lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 103, 114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.Y.; Sun, B.; Jiang, P.K. Highly thermally conductive yet electrically insulating polymer/boron nitride nanosheets nanocomposite films for improved thermal management capability. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhao, Q.; Ye, F. An experimental study on gas and liquid two-phase flow in orientated-type flow channels of proton exchange membrane fuel cells by using a side-view method. Renew. Energy 2022, 188, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Hou, J.; Song, M.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Y. Design of battery thermal management system based on phase change material and heat pipe. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 188, 116665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.X.; Yang, X.Q.; Zhang, G.Q.; Chen, K.; Wang, S.F. Experimental investigation on the thermal performance of heat pipe-assisted phase change material-based battery thermal management system. Energy Conv. Manag. 2017, 138, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Panigrahi, P.K. A hybrid battery thermal management system using ionic wind and phase change material. Appl. Energy 2024, 359, 122676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; He, Y. All-climate thermal management structure for batteries based on expanded graphite/polymer composite phase change material with a high thermal and electrical conductivity. Appl. Energy 2022, 322, 119509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Z. PVA-assisted graphene aerogels composite phase change materials with anisotropic porous structure for thermal management. Carbon 2024, 230, 119639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Zhao, H.Y.; Lu, X.H.; Min, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.L.; Li, X.F.; Yu, Z.Z. High-quality anisotropic graphene aerogels and their thermally conductive phase change composites for efficient solar-thermal-electrical energy conversion. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 11991–12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Li, Y.; An, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, K.; Wu, D.; Sun, J. 3D printing, leakage-proof, and flexible phase change composites for thermal management application. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 258, 110905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yang, P.; Wang, B.K.; Li, M.Y.; Niu, M.Y.; Yuan, K.J.; Xuan, W.W.; Lu, Q.P.; Cao, W.B.; Wang, Q. In situ construction of vertically aligned AlN skeletons for enhancing the thermal conductivity of stearic acid-based phase-change composites. Mat. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Zhao, S.; Deng, W.; Min, P.; Lu, X.-H.; Li, X.; Yu, Z.-Z. Highly thermally conductive phase change composites with anisotropic graphene/cellulose nanofiber hybrid aerogels for efficient temperature regulation and solar-thermal-electric energy conversion applications. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2023, 248, 110367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xue, F.; Qi, X.-d.; Yang, J.-h.; Zhou, Z.-w.; Yuan, Y.-p.; Wang, Y. Photo- and electro-responsive phase change materials based on highly anisotropic microcrystalline cellulose/graphene nanoplatelet structure. Appl. Energy 2019, 236, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, A.; Buahom, P.; Shokouhi, E.B.; Mark, L.H.; Rahmati, R.; Tafreshi, O.A.; Hamidinejad, M.; Mandelis, A.; Kim, K.S.; Park, C.B. Highly anisotropic thermally conductive dielectric polymer/Boron nitride nanotube composites for directional heat dissipation. Small 2024, 20, 2404189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, S.; Yao, Q.; Cao, B.; Wang, F.; Wang, N. Form-stable phase change composites encapsulated in 1D multifunctional matrices for enhanced electro-thermal energy conversion. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, D.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y. Directional enhancement and potential reduction of thermal conductivity induced by one-dimensional nanoparticle addition in pure PCMs. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 215, 124478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mu, B.Y. Effect of different dimensional carbon materials on the properties and application of phase change materials: A review. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 695–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhu, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, H.; Ma, C.; Li, A. Enhanced thermal conductivity of phase change material nanocomposites based on MnO2 nanowires and nanotubes for energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 180, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Kang, M.; Liu, Y.; Lin, W.; Liang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, J. The preparation and characterization of phase change material microcapsules with multifunctional carbon nanotubes for controlling temperature. Energy 2023, 268, 126652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, N. Exfoliated 2D hexagonal boron nitride nanosheet stabilized stearic acid as composite phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy 2020, 204, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhao, L.; Shen, C.; Mao, Z.; Xu, H.; Feng, X.; Wang, B.; Sui, X. Boron nitride microsheets bridged with reduced graphene oxide as scaffolds for multifunctional shape stabilized phase change materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 209, 110441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Cao, G.; Sun, X.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, F.; Di, X.; Li, J.; et al. Low-cost, three-dimension, high thermal conductivity, carbonized wood-based composite phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Energy 2018, 159, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Gao, H.; Li, A.; Wang, C. Construction of CNT@Cr-MIL-101-NH2 hybrid composite for shape-stabilized phase change materials with enhanced thermal conductivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 350, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, L.S.; Li, L.J.; Huang, Z.H.; Chen, Y. Hybrid microencapsulated phase-change material and carbon nanotube suspensions toward solar energy conversion and storage. Energies 2020, 13, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Han, X.; Ma, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, C.; Li, R.; Li, C. Form-stable phase change composites with high thermal conductivity and enthalpy enabled by Graphene/Carbon nanotubes aerogel skeleton for thermal energy storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 255, 123954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, N.; Ren, Y.; Yang, X.; Pan, H.; Chai, Z.; Xu, L.; Huang, X. Anisotropic and hierarchical porous boron nitride/graphene aerogels supported phase change materials for efficient solar-thermal energy conversion. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 18923–18931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.H.; Xing, X.; Li, S.S.; Wu, X.Y.; Jia, Q.Q.; Tu, H.; Bian, H.L.; Lu, A.; Zhang, L.N.; Yang, H.Y.; et al. Anisotropic hybrid hydrogels constructed via the noncovalent assembly for biomimetic tissue scaffold. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, S.; Cao, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Jian, X.; Weng, Z. Improving the comprehensive properties of chitosan-based thermal insulation aerogels by introducing a biobased epoxy thermoset to form an anisotropic honeycomb-layered structure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, C.; Meng, W.; Sheng, N.; Zhu, C.; Rao, Z. Anisotropically enhancing thermal conductivity of epoxy composite with a low filler load by an AlN/C fiber skeleton. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 17604–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ez-Zahraoui, S.; Semlali, F.-Z.; Raji, M.; Nazih, F.-Z.; Bouhfid, R.; Qaiss, A.E.K.; El Achaby, M. Synergistic reinforcing effect of fly ash and powdered wood chips on the properties of polypropylene hybrid composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zou, M.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Hu, X.; Chen, W.; Jiang, X. Polypyrrole and Ag nanoparticles synergistically enhances the photothermal conversion performance of microencapsulated phase change energy storage materials in multiple way. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 283, 113451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, T.; Shi, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, T.; Tang, S.; Chen, L.; Lu, H.; Song, J. Thermal conductivity enhancement for multi-functional phase change materials: From random fillers to oriented networks in viscous systems. iScience 2025, 28, 113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Qiu, Y.; Ye, C.; Li, Q. Anisotropically conductive phase change composites enabled by aligned continuous carbon fibers for full-spectrum solar thermal energy harvesting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 141940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.-K.; Zhao, R.; Chen, J.; Cheng, W.-L. Theoretical and experimental study on the anisotropic thermal conductivity of composite phase change materials prepared by hot-pressing method. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 198, 123380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, N.; Zhu, R.J.; Dong, K.X.; Nomura, T.; Zhu, C.Y.; Aoki, Y.; Habazaki, H.; Akiyama, T. Vertically aligned carbon fibers as supporting scaffolds for phase change composites with anisotropic thermal conductivity and good shape stability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 4934–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | CA Content (%) | Phase-Change Temperature (°C) | Latent Heat (J/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid 1D/3D-based FPCM | 8 | 60.9 | 126.01 |

| Single 3D-based FPCM | 8 | 60.1 | 122.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Yang, T.; Jiang, J.; Luo, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Guan, S. Architecting Highly Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Flexible Phase Change Materials for Directed Thermal Management of Cylindrical Li-Ion Batteries. Materials 2025, 18, 5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235400

Chen L, Yang T, Jiang J, Luo J, Li Y, Wang J, Li W, Guan S. Architecting Highly Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Flexible Phase Change Materials for Directed Thermal Management of Cylindrical Li-Ion Batteries. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235400

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Liying, Tong Yang, Jun Jiang, Jianwen Luo, Yuanyuan Li, Juntao Wang, Wanwan Li, and Sujun Guan. 2025. "Architecting Highly Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Flexible Phase Change Materials for Directed Thermal Management of Cylindrical Li-Ion Batteries" Materials 18, no. 23: 5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235400

APA StyleChen, L., Yang, T., Jiang, J., Luo, J., Li, Y., Wang, J., Li, W., & Guan, S. (2025). Architecting Highly Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Flexible Phase Change Materials for Directed Thermal Management of Cylindrical Li-Ion Batteries. Materials, 18(23), 5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235400