Study on Antibacterial Powder Coatings Based on Halloysite/Biopolymer Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antimicrobial Agents (AA): Materials and Preparation Methodology

2.2. Preparation of Powder Coatings

- Saturated polyester resin: GP 95518, acid value: 35 mg KOH/g (Sarzyna Chemical, Sarzyna, Poland);

- β-hydroxyalkyl-amide curing agent: Primid XL-552, hydroxyl number: 620–700 mg KOH/g, melting range 120–125 °C (EMS-CHEMIE AG, Domat/Ems, Switzerland);

- Degassing agent: benzoin (Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland);

- Flow control agent: Byk 368P (Byk-Chemie, Wesel, Germany);

- Filler: barium sulfate, Albasoft 100 (Deutsche Baryt-Industrie, Bad Lauterberg, Germany);

- Brown iron pigment: Bayferrox 654 T (Lanxess, Köln, Germany);

- Antimicrobial agents: ε-polylysine (PLY), halloysite (HAL), PLY immobilized on halloysite (HAL/PLY), quaternized chitosan (CH-Q) or quaternized chitosan (CH-Q) immobilized on halloysite (HAL/CH-Q).

2.3. Measurements

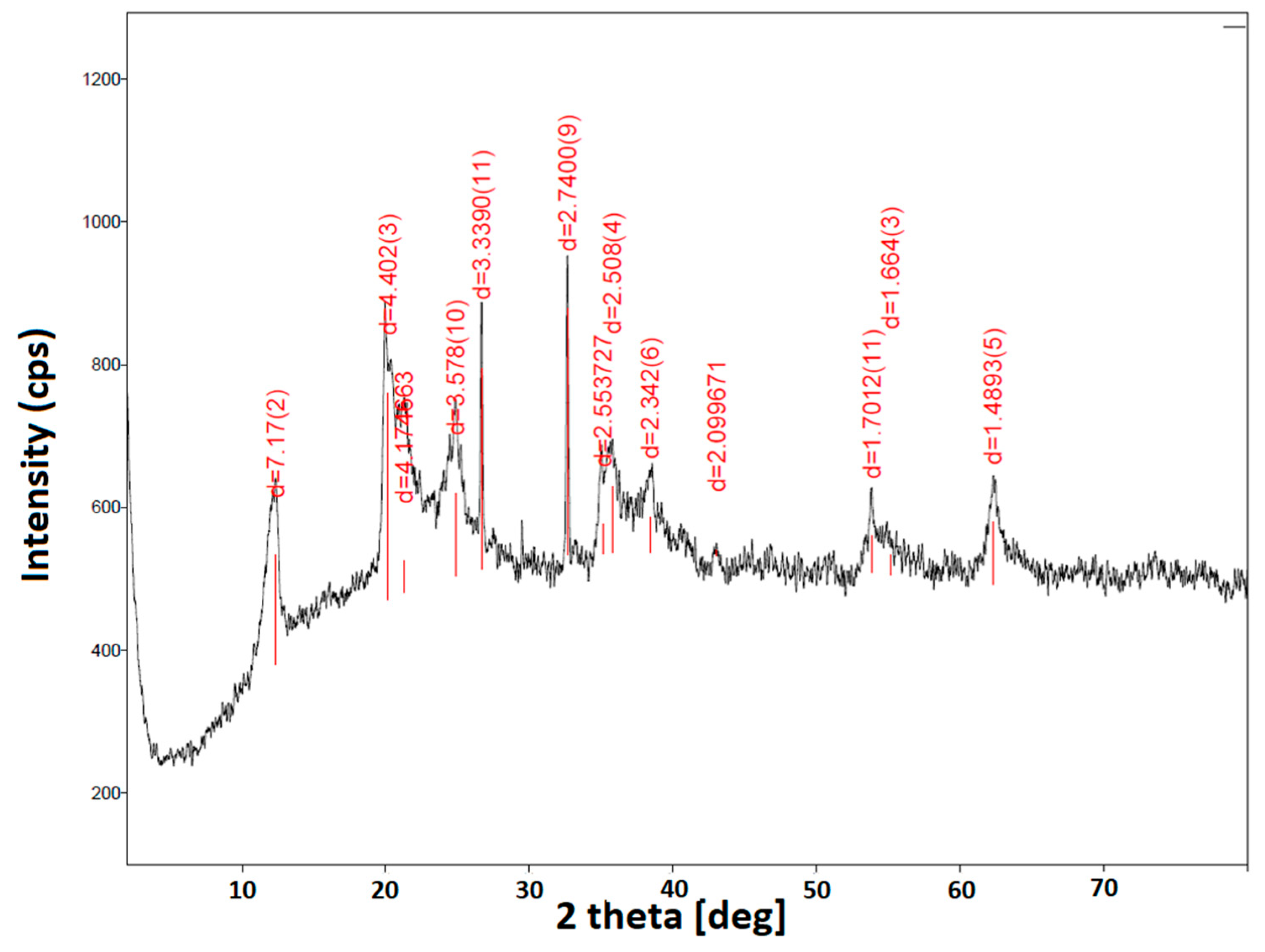

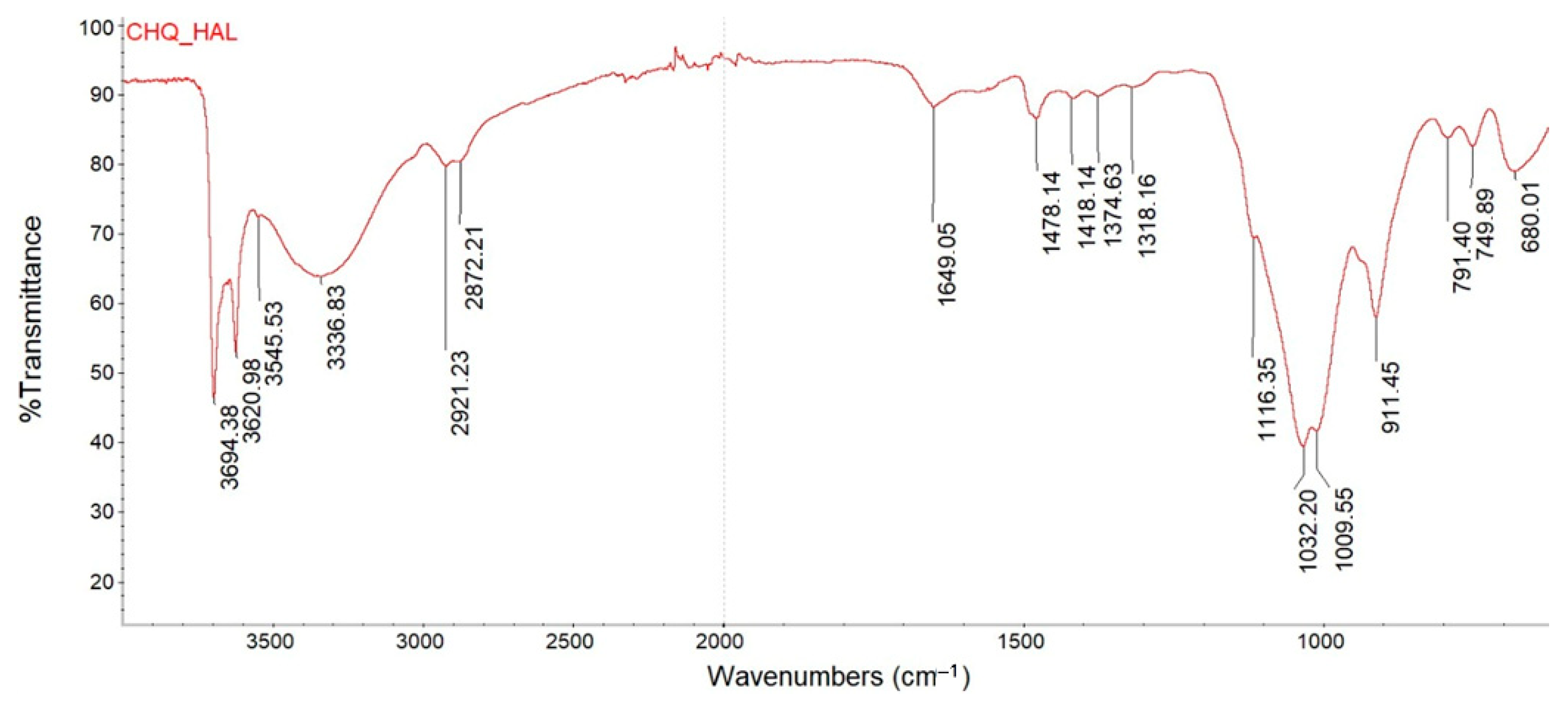

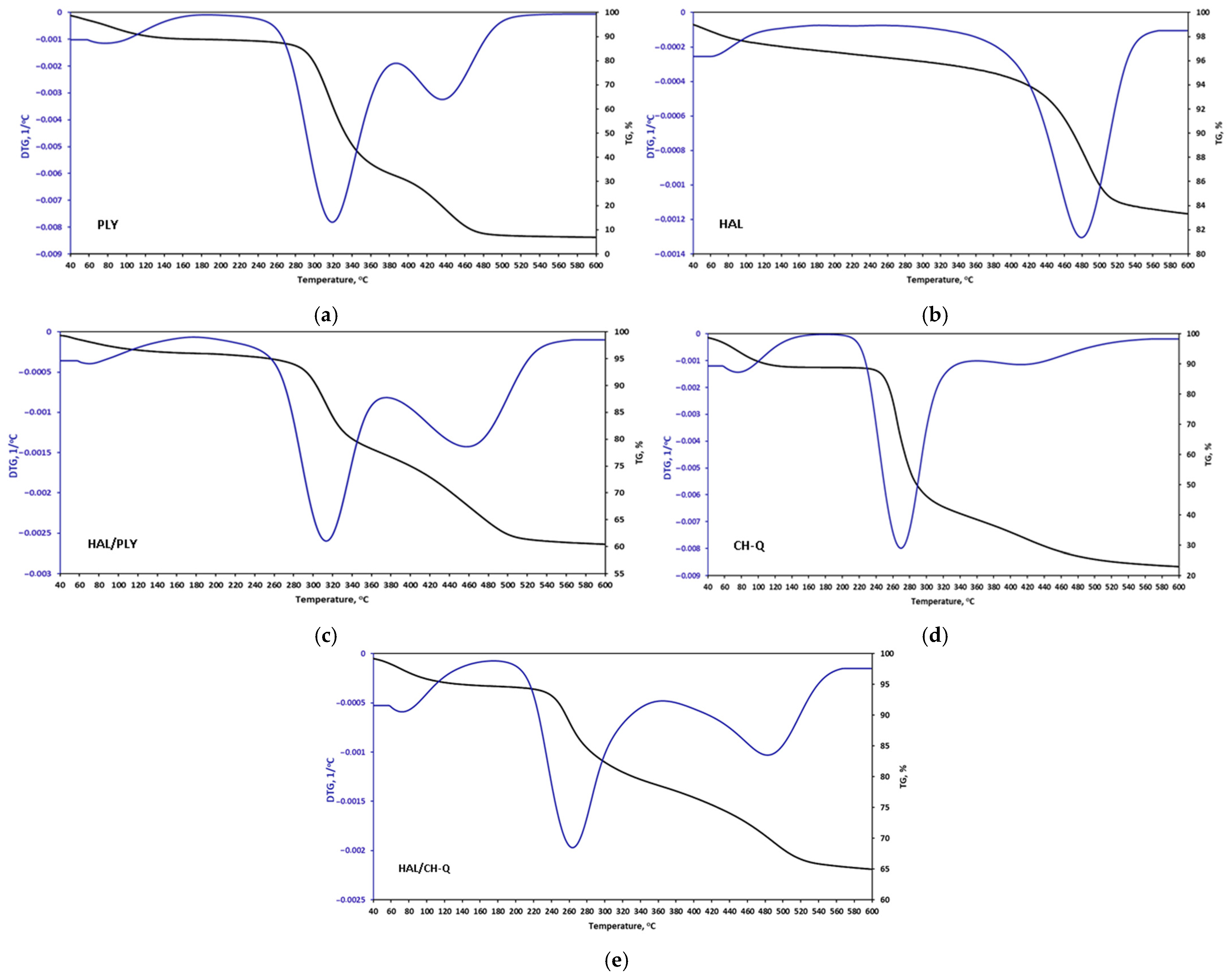

2.3.1. Characterization of Antimicrobial Agent

2.3.2. Characterization of Powder Coatings

- L*—lightness (0 = black, 100 = white),

- a*—green-red axis (− = green, + = red),

- b*—blue-yellow axis (− = blue, + = yellow).

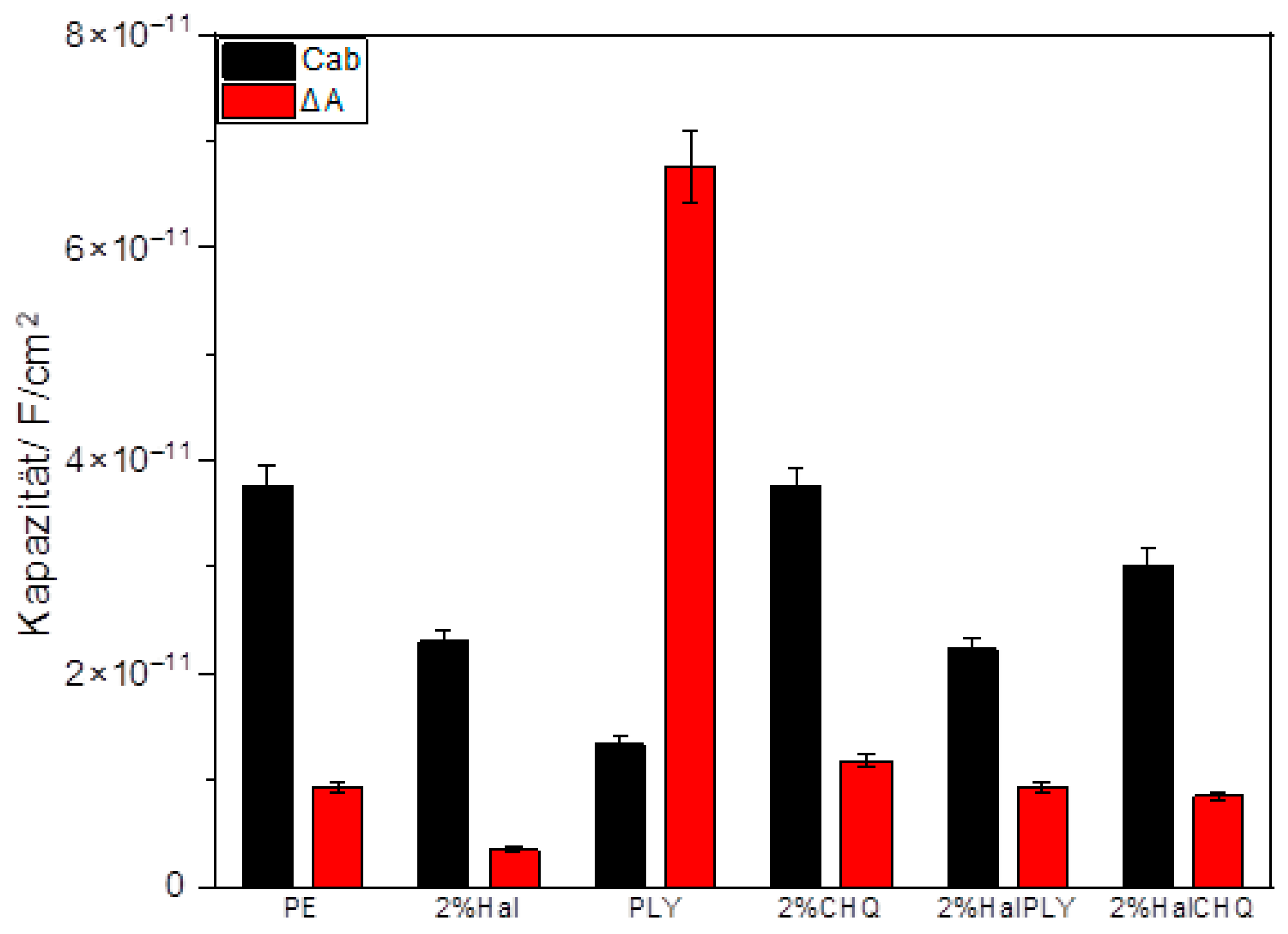

- C: coating capacitance,

- ε0: vacuum permittivity (8.854*10−12 F m−1),

- A: detected area,

- d: coating thickness,

- εr: dielectric constant, εr (H2O) ≈ 80, εr (polymer) < 8.

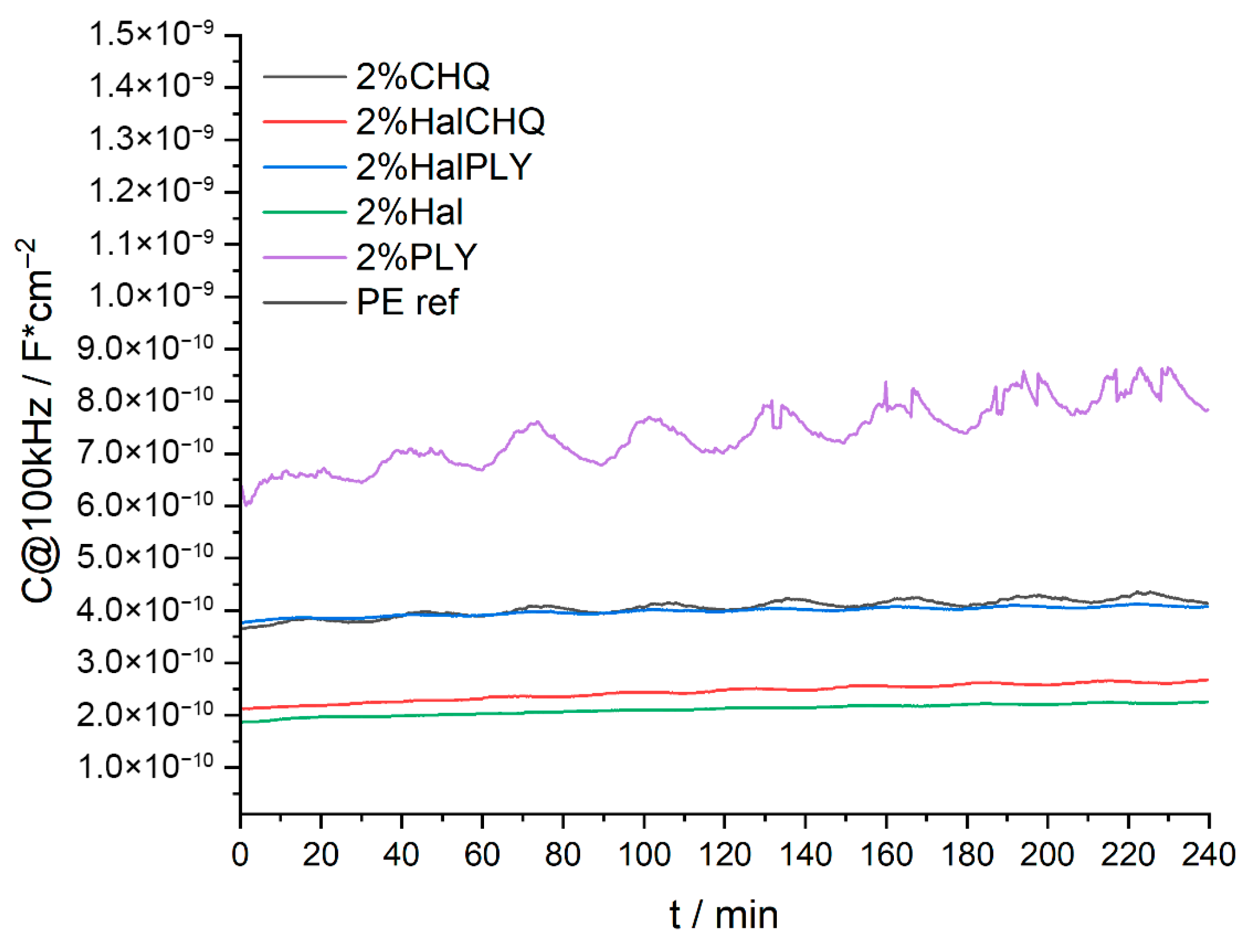

2.3.3. Washing Resistance of Antibacterial Additives

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antimicrobial Agents’ Characterization

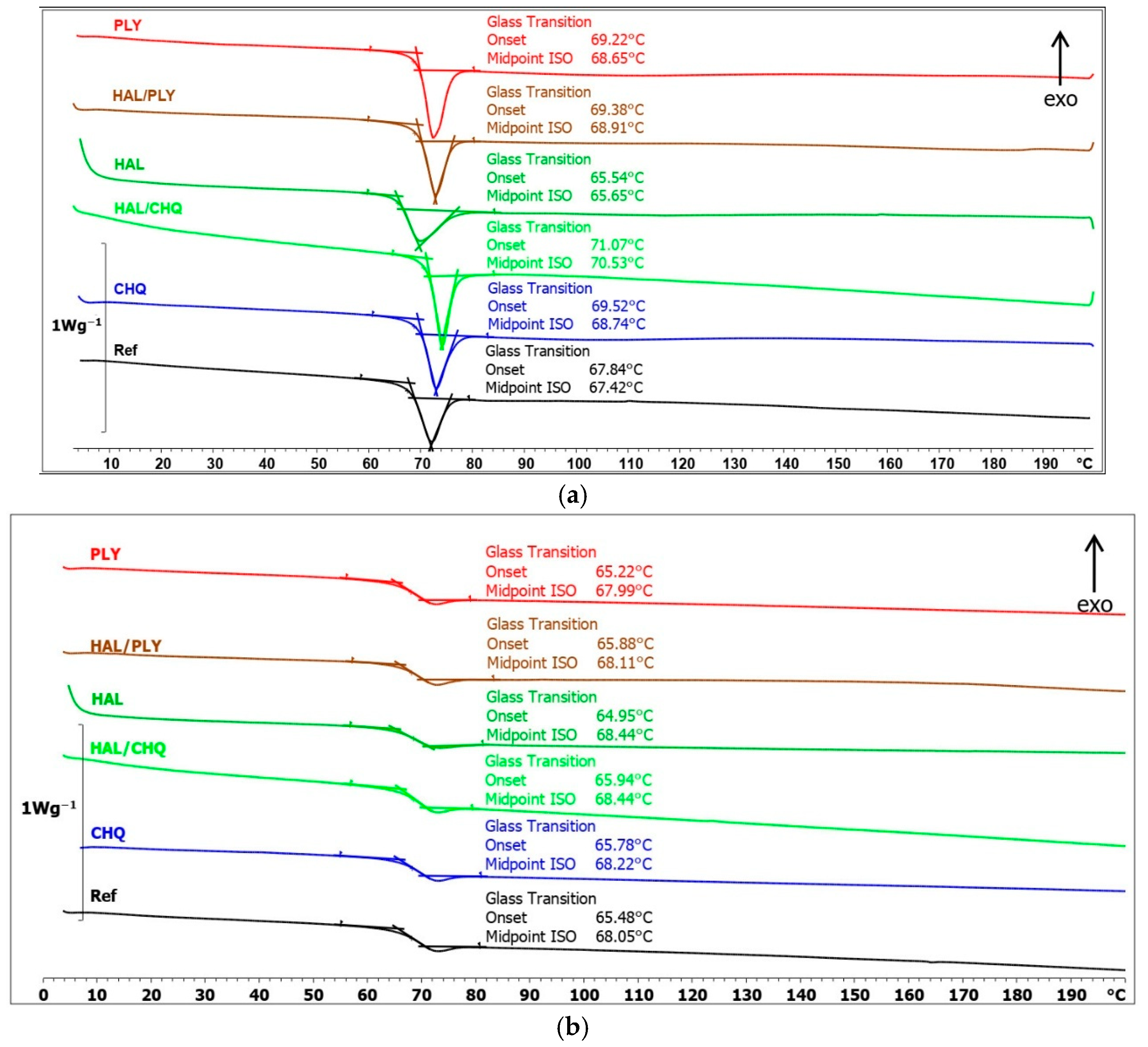

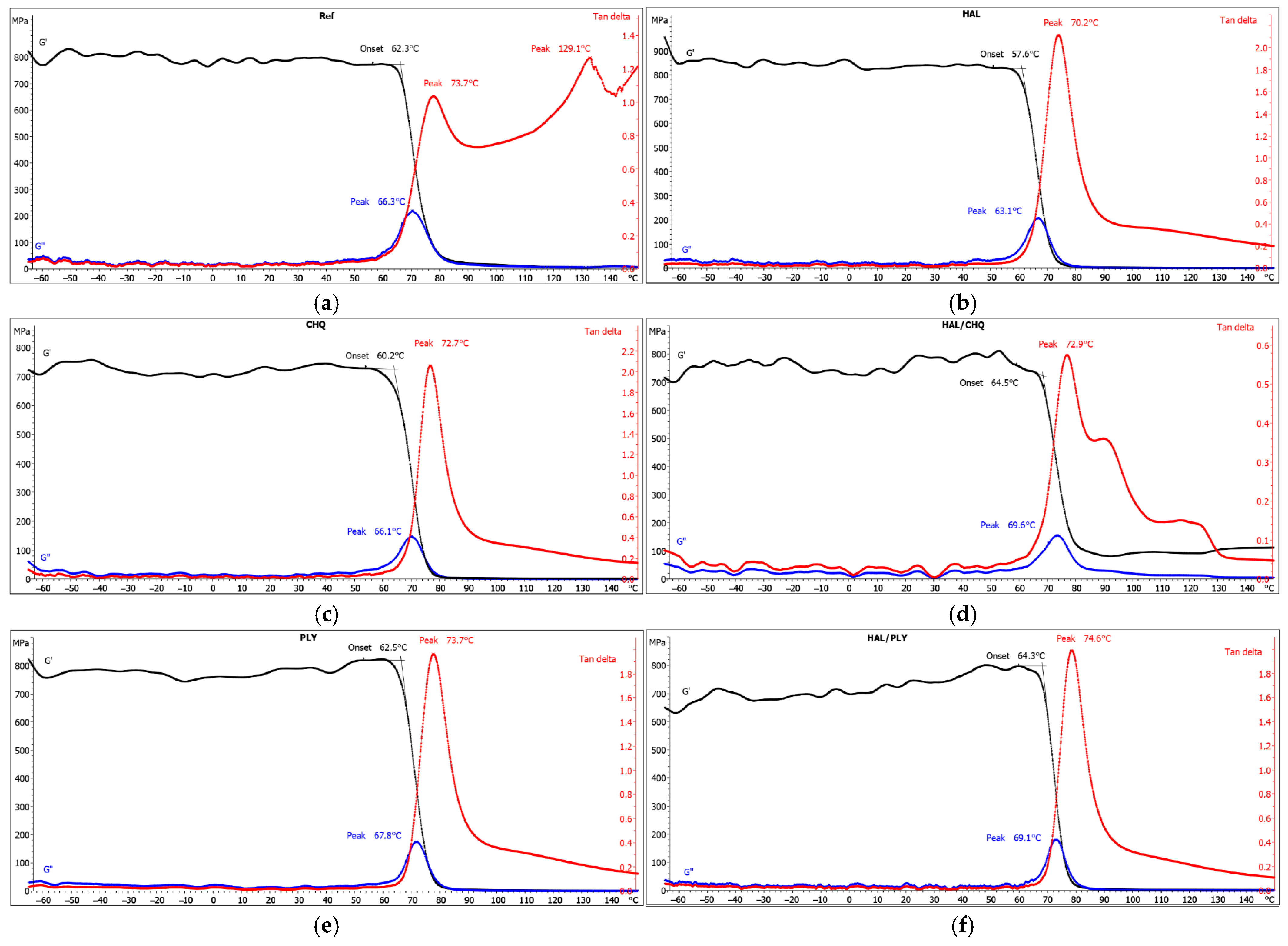

3.2. Powder Coatings Characterization

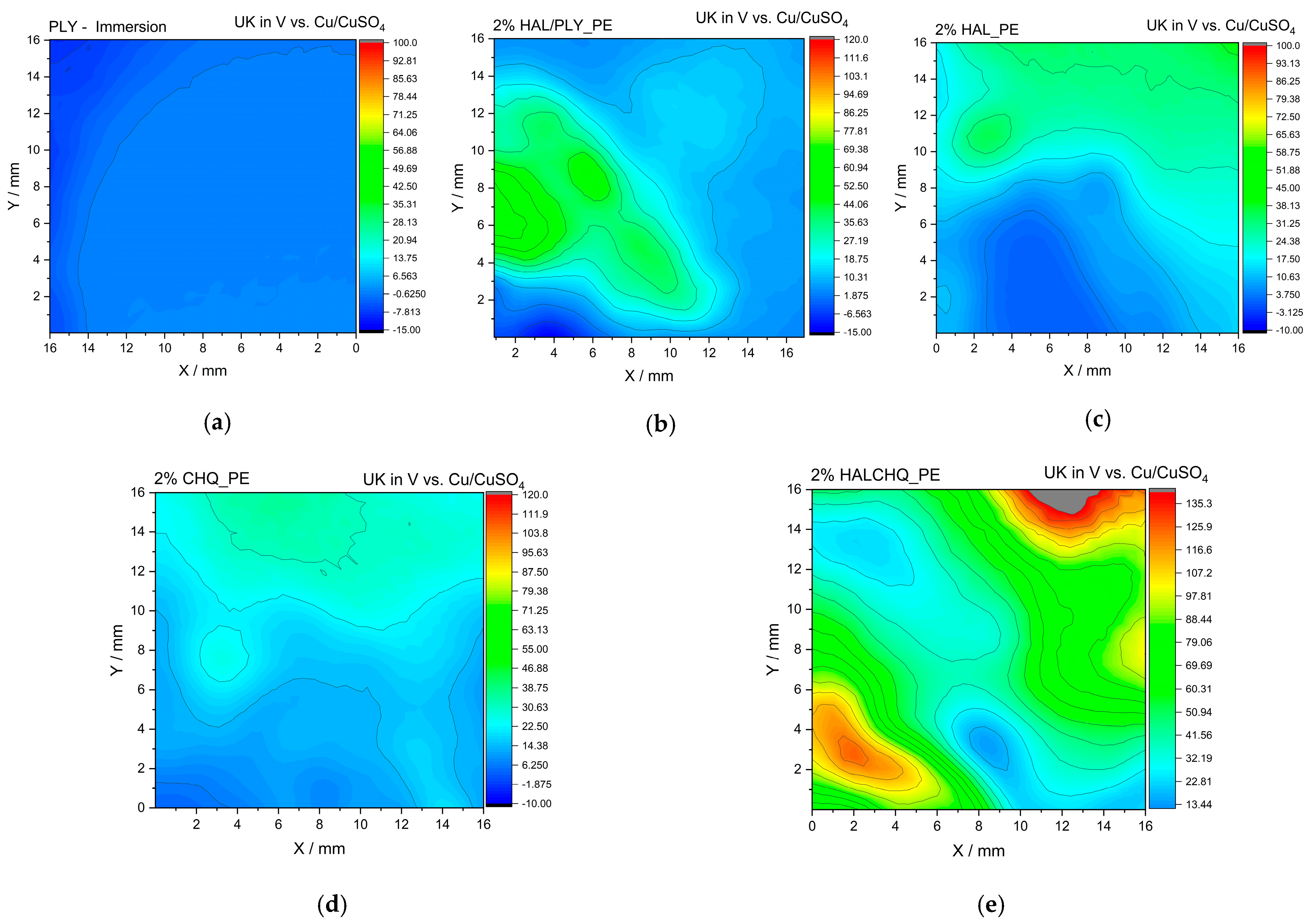

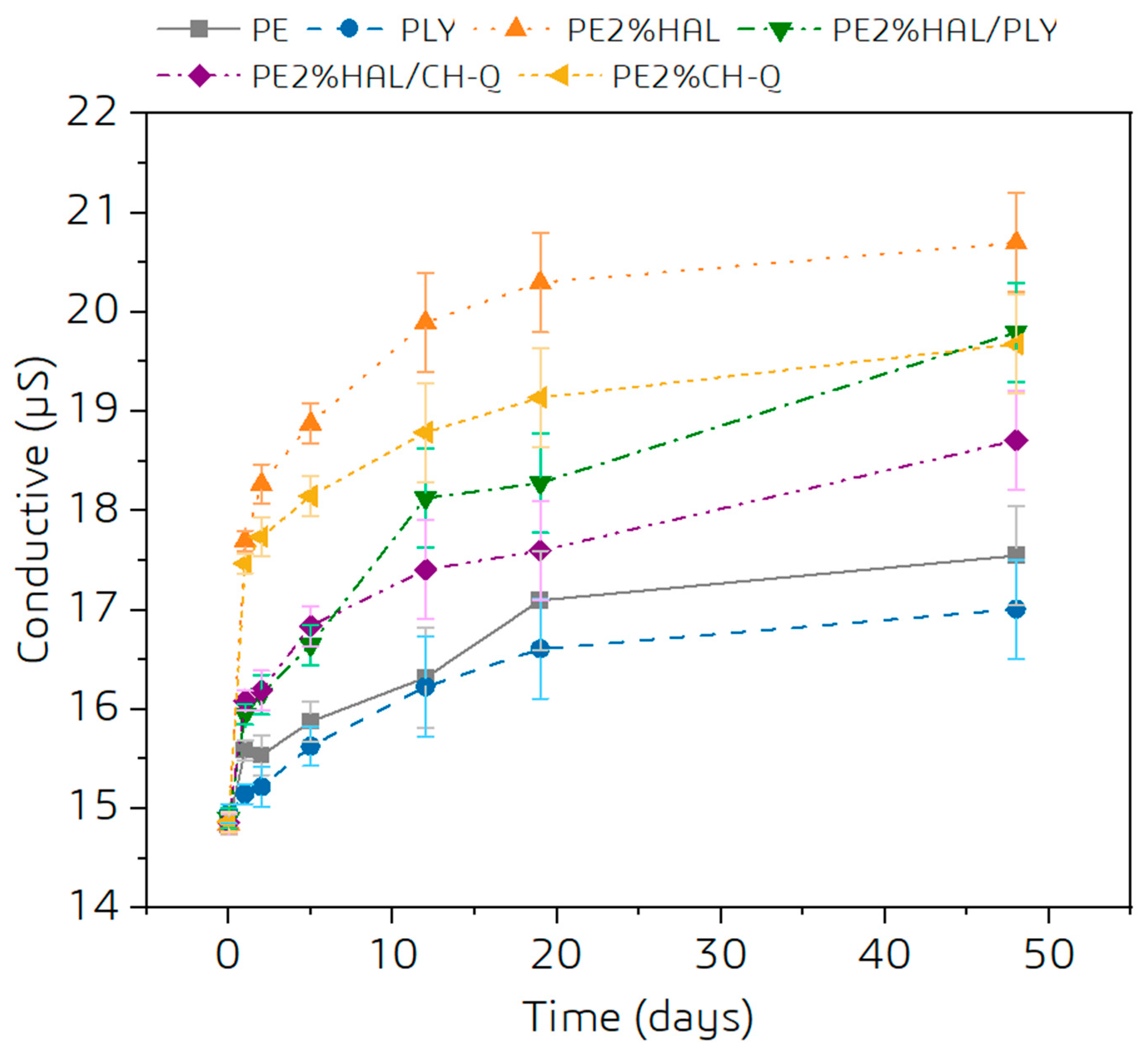

3.3. Structure–Performance Correlation (SEM, FTIR, SKP, WUR)

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLY | polylysine |

| CH-Q | quaternized chitosan |

| HAL | halloysite |

| MMT | montmorillonite |

References

- Sauer, F. Microbicides in Coatings; Vincentz Network: Hannover, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Puttaiahgowda, Y.M.; Nagaraja, A.; Jalageri, M.D. Antimicrobial Polymeric Paints: An Up-to-date Review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 4642–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhareva, K.; Chernetsov, V.; Burmistrov, I. A Review of Antimicrobial Polymer Coatings on Steel for the Food Processing Industry. Polymers 2024, 16, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Shi, Q.; Chen, M.; Yu, W.; Yang, T. Antibacterial-Based Hydrogel Coatings and Their Application in the Biomedical Field—A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Duse, A.; Wattal, C.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Sumpradit, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Hara, G.L.; Gould, I.M.; Goossens, H.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance—The Need for Global Solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 1057–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Liu, S. Antibacterial Surface Design—Contact Kill. Progress Surf. Sci. 2016, 91, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, M.; Mantovani, D.; Rosei, F. Antibacterial Coatings: Challenges, Perspectives, and Opportunities. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capricho, J.C.; Liao, T.-Y.; Chai, B.X.; Al-Qatatsheh, A.; Vongsvivut, J.; Kingshott, P.; Juodkazis, S.; Fox, B.L.; Hameed, N. Magnetically Cured Macroradical Epoxy as Antimicrobial Coating. Chem. Asian J. 2023, 18, e202300237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molling, J.; Seezink, J.; Teunissen, B.; Muijrers-Chen, I.; Borm, P. Comparative Performance of a Panel of Commercially Available Antimicrobial Nanocoatings in Europe. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2014, 7, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22196; Measurement of Antibacterial Activity on Plastics and Other Non-Porous Surfaces. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Das, D.; Paul, P. Environmental Impact of Silver Nanoparticles and its Sustainable Mitigation by Novel Approach of Green Chemistry. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 14, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Yang, X. How to safeguard soil health against silver nanoparticles through a microbial functional gene-based approach? Environ. Int. 2025, 202, 109680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Orozco, M.F.; Lorenzo-Leal, A.C.; de Alba Montero, I.; Marín, N.P.; Santana, M.A.C.; Bach, H. Mechanism of Escape from the Antibacterial Activity of Metal-Based Nanoparticles in Clinically Relevant Bacteria: A Systematic Review. Nanomedicine 2024, 55, 102715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, O.I.; Aslam, R.; Pan, D.; Sharma, S.; Andotra, M.; Kaur, A.; Jia, A.-Q.; Faggio, C. Source, bioaccumulation, degradability and toxicity of triclosan in aquatic environments: A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahariah, P.; Gaware, V.; Lieder, R.; Jónsdóttir, S.; Hjálmarsdóttir, M.; Sigurjonsson, O.; Másson, M. The Effect of Substituent, Degree of Acetylation and Positioning of the Cationic Charge on the Antibacterial Activity of Quaternary Chitosan Derivatives. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 4635–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilch-Pitera, B.; Krawczyk, K.; Kędzierski, M.; Pojnar, K.; Lehmann, H.; Czachor-Jadacka, D.; Bieniek, K.; Hilt, M. Antimi-crobial Powder Coatings Based on Environmentally Friendly Biocides. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 10325–10339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čalija, B.; Milić, J.; Milašinović, N.; Daković, A.; Trifković, K.; Stojanović, J.; Krajišnik, D. Functionality of Chitosan-halloysite Nanocomposite Films for Sustained Delivery of Antibiotics: The Effect of Chitosan Molar Mass. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervini-Silva, J.; Camacho, A.N.; Palacios, E.; Del Angel, P.; Pentrak, M.; Pentrakova, L.; Kaufhold, S.; Ufer, K.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Gómez-Vidales, V.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxic Activity by Natural Matrices of Nano-Iron(Hydr)Oxide/Halloysite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 120, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.B.; Metge, D.W.; Eberl, D.D.; Harvey, R.W.; Turner, A.G.; Prapaipong, P.; Poret-Peterson, A.T. What Makes a Natural Clay Antibacterial? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3768–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 12085; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile Method—Motif Parameters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996.

- ISO 2813; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Specular Gloss of Non-Metallic Paint Films at 20 Degrees, 60 Degrees and 85 Degrees. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 2808; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Film Thickness. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 2409; Paints and Varnishes—Cross-Cut Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 1522; Paints and Varnishes—Pendulum Damping Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ISO 1520; Paints and Varnishes—Cupping Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 7724; Paints and Varnishes—Colorimetry. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1984.

- Sakiewicz, P.; Nowosielski, R.; Pilarczyk, W.; Golombek, K.; Lutynski, M. Selected properties of the halloysite as a component of Geosynthetic Clay Liners (GCL). J. Achiev. Mater. Manufactur. Eng. 2011, 48, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Pasabeyoglu, P.; Deniz, E.; Moumin, G.; Say, Z.; Akata, B. Solar-Driven Calcination of Clays for Sustainable Zeolite Production: CO2 Capture Performance at Ambient Conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 477, 143838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joussein, E.; Petit, S.; Churchman, J.; Theng, B.; Righi, D.; Delvaux, B. Halloysite Clay Minerals—A Review. Clay Miner. 2005, 40, 383–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Noguchi, T.; Miyake, A.; Igami, Y.; Haruta, M.; Seto, Y.; Miyahara, M.; Tomioka, N.; Saito, H.; Hata, S.; et al. Influx of nitrogen-rich material from the outer Solar System indicated by iron nitride in Ryugu samples. Nat. Astron. 2024, 8, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitarz-Palczak, E.; Kalembkiewicz, J. The Influence of Physical Modification on the Sorption Properties of Geopolymers Ob-tained from Halloysite. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 5749–5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhung, L.T.T.; Kim, I.Y.; Yoon, Y.S. Quaternized Chitosan-Based Anion Exchange Membrane Composited with Quaternized Poly(vinylbenzyl chloride)/Polysulfone Blend. Polymers 2020, 12, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, M.; Mathew, M.; Pradyumnan, P.P.; Francis, T. Dielectric and Thermal Stability Studies on High Density Polyethylene—Chitosan Composites Plasticized with Palm Oil. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 2742–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualicoat. Specifications for a Quality Label for Liquid and Powder Organic Coatings on Aluminium for Architectural Applications, 25th ed.; Qualicoat: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cui, J.; Yang, J.; Yan, H.; Zhu, X.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J. Effect of Carrier Materials for Active Silver in Anti-bacterial Powder Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davodiroknabadi, A.; Shahvaziyan, M.; Shirgholami, M. Ultrasound’s influence on the properties of cellulose/halloysite clay nanotube nanocomposites. Int. J. Mater. Res. (Former. Z. Fuer Met.) 2025, 116, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pongsuk, P.; Pumchusak, J. Effect of Ultrasonication on the Morphology, Mechanical Property, Ionic Conductivity, and Flame Retardancy of PEO-LiCF3SO3-Halloysite Nanotube Composites for Use as Solid Polymer Electrolyte. Polymers 2022, 14, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legocka, I.; Wierzbicka, E.; Al-Zahari, T.M.; Osawaru, O. Influence of halloysite on the structure, thermal and mechanical properties of polyamide 6. Polimery 2013, 58, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persano, F.; Gigli, G.; Leporatti, S. Halloysite-Based Nanosystems for Biomedical Applications. Clays Clay Miner. 2021, 69, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisuzzo, L.; Cavallaro, G.; Milioto, S.; Lazzara, G. Halloysite Nanotubes Coated by Chitosan for the Controlled Release of Khellin. Polymers 2020, 12, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Ma, R.; Lin, C.; Liu, Z.; Tang, T. Quaternized Chitosan as an Antimicrobial Agent: Antimicrobial Activity, Mechanism of Action and Biomedical Applications in Orthopedics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 1854–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component/ Symbol of Coating | Polyester Resin | XL-552 | Benzoin | Byk 368P | Bayferrox 654 | Albasoft 100 | PLY | HAL | HAL/ PLY | CH-Q | HAL/ CH-Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [wt.%] | |||||||||||

| PE (reference sample) | 65.55 | 3.45 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.50 | 25.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| PLY | 65.55 | 3.45 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.50 | 23.00 | 2.00 | - | - | - | - |

| HAL | 65.55 | 3.45 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.50 | 23.00 | - | 2.00 | - | - | - |

| HAL/PLY | 65.55 | 3.45 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.50 | 23.00 | - | - | 2.00 | - | - |

| CH-Q | 65.55 | 3.45 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.50 | 23.00 | - | - | - | 2.00 | - |

| HAL/CH-Q | 65.55 | 3.45 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.50 | 23.00 | - | - | - | - | 2.00 |

| Symbol | C [wt.%] | H [wt.%] | N [wt.%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLY | 39.87 ± 0.21 | 8.03 ± 0.04 | 15.00 ± 0.22 |

| HAL | 1.13 ± 0.07 | 1.81 ± 0.02 | 0.69 ± 0.01 |

| HAL/PLY | 13.38 ± 0.08 | 3.73 ± 0.01 | 5.22 ± 0.03 |

| CH-Q | 41.08 ± 0.03 | 8.23 ± 0.02 | 8.00 ± 0.03 |

| HAL/CH-Q | 15.81 ± 0.03 | 3.99 ± 0.02 | 3.34 ± 0.01 |

| AA Symbol | Decomposition Temperature Ranges [°C]/wt.% Loss | DTG Max [°C] | Total wt.% Loss at 600 °C |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLY | 25–180/8 240–560/83 | 76 310; 425; 444 | 91 |

| HAL | 25–200/2.5 200–700/12.5 | 80 480 | 15 |

| HAL/PLY | 25–180/3 180–600/36 | 80 312; 465 | 39 |

| CH-Q | 25–180/10 180–600/65 | 75 272; 408 | 75 |

| HAL/CH-Q | 25–180/4 180–600/29 | 72 274; 490 | 33 |

| Symbol of Coating | PE (Refer. Sample) | PLY | HAL | HAL/PLY | CH-Q | HAL/CH-Q | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roughness ISO 12085 [20] | Ra, µm | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 2.97 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.03 |

| Rz, µm | 0.70 ± 0.16 | 12.10 ± 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.17 | 0.83 ± 0.18 | 2.13 ± 0.18 | 0.77 ± 0.13 | |

| Gloss (60°) ISO 2813 [21] | GU | 87.0 ± 1.2 | 10.7 ± 1.5 | 89.2 ± 0.9 | 84.5 ± 1.6 | 83.3 ± 1.1 | 85.5 ± 1.2 |

| Thickness ISO 2808 [22] | µm | 60.1 ± 1.6 | 63.3 ± 2.5 | 65.4 ± 2.1 | 70.5 ± 1.8 | 61.7 ± 2.2 | 69.7 ± 2.6 |

| Relative hardness ISO 1522 [24] | - | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.03 |

| Adhesion to the steel ISO 2409 [23] | 0-best 5-worst | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cupping ISO 1520 [25] | mm | 10.01 ± 0.07 | 6.37 ± 0.09 | 10.45 ± 0.11 | 9.08 ± 0.05 | 10.06 ± 0.09 | 10.47 ± 0.13 |

| Color ISO 7724 [26] | - | L* = 17.46 a* = 15.53 b* = 18.27 | L* = 25.86 a* = 11.34 b* = 10.35 | L* = 18.88 a* = 15.27 b* = 17.33 | L* = 19.64 a* = 15.15 b* = 17.38 | L* = 19.51 a* = 14.73 b* = 16.32 | L* = 19.09 a* = 14.95 b* = 16.53 |

| - | ΔE*ab = 8.40 ± 0.28 | ΔE*ab = 1.74 ± 0.58 | ΔE*ab = 2.38 ± 0.15 | ΔE*ab = 2.93 ± 0.07 | ΔE*ab = 2.44 ± 0.02 | ||

| Reduction in Escherichia coli ISO 22196 [10] | % | 99.9836 ± 0.0007 | 50.5226 ± 0.2223 | 99.9998 ± 0.0001 | 48.0256 ± 0.4550 | 50.2323 ± 0.3701; 70.9986 ± 0.1273(s) | |

| Reduction in Staphylococcus aureus ISO 22196 [10] | % | 99.9333 ± 0.0011 | uncountable | 99.9993 ± 0.0002 | 81.5603 ± 0.6282 | 70.9220 ± 0.0691; 98.6500 ± 0.0021(s) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krawczyk, K.; Pilch-Pitera, B.; Kędzierski, M.; Zubielewicz, M.; Kunce, I.; Langer, E.; Jurczyk, S.; Kamińska-Bach, G.; Ciszkowicz, E.; Przybysz-Romatowska, M.; et al. Study on Antibacterial Powder Coatings Based on Halloysite/Biopolymer Compounds. Materials 2025, 18, 5402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235402

Krawczyk K, Pilch-Pitera B, Kędzierski M, Zubielewicz M, Kunce I, Langer E, Jurczyk S, Kamińska-Bach G, Ciszkowicz E, Przybysz-Romatowska M, et al. Study on Antibacterial Powder Coatings Based on Halloysite/Biopolymer Compounds. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235402

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrawczyk, Katarzyna, Barbara Pilch-Pitera, Michał Kędzierski, Małgorzata Zubielewicz, Izabela Kunce, Ewa Langer, Sebastian Jurczyk, Grażyna Kamińska-Bach, Ewa Ciszkowicz, Marta Przybysz-Romatowska, and et al. 2025. "Study on Antibacterial Powder Coatings Based on Halloysite/Biopolymer Compounds" Materials 18, no. 23: 5402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235402

APA StyleKrawczyk, K., Pilch-Pitera, B., Kędzierski, M., Zubielewicz, M., Kunce, I., Langer, E., Jurczyk, S., Kamińska-Bach, G., Ciszkowicz, E., Przybysz-Romatowska, M., Wojda, D., Komorowski, L., & Hilt, M. (2025). Study on Antibacterial Powder Coatings Based on Halloysite/Biopolymer Compounds. Materials, 18(23), 5402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235402