Integrative Evaluation of Bead Morphology in Plasma Transferred Arc Cladding Through Orthogonal Arrays and Morphology Index Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

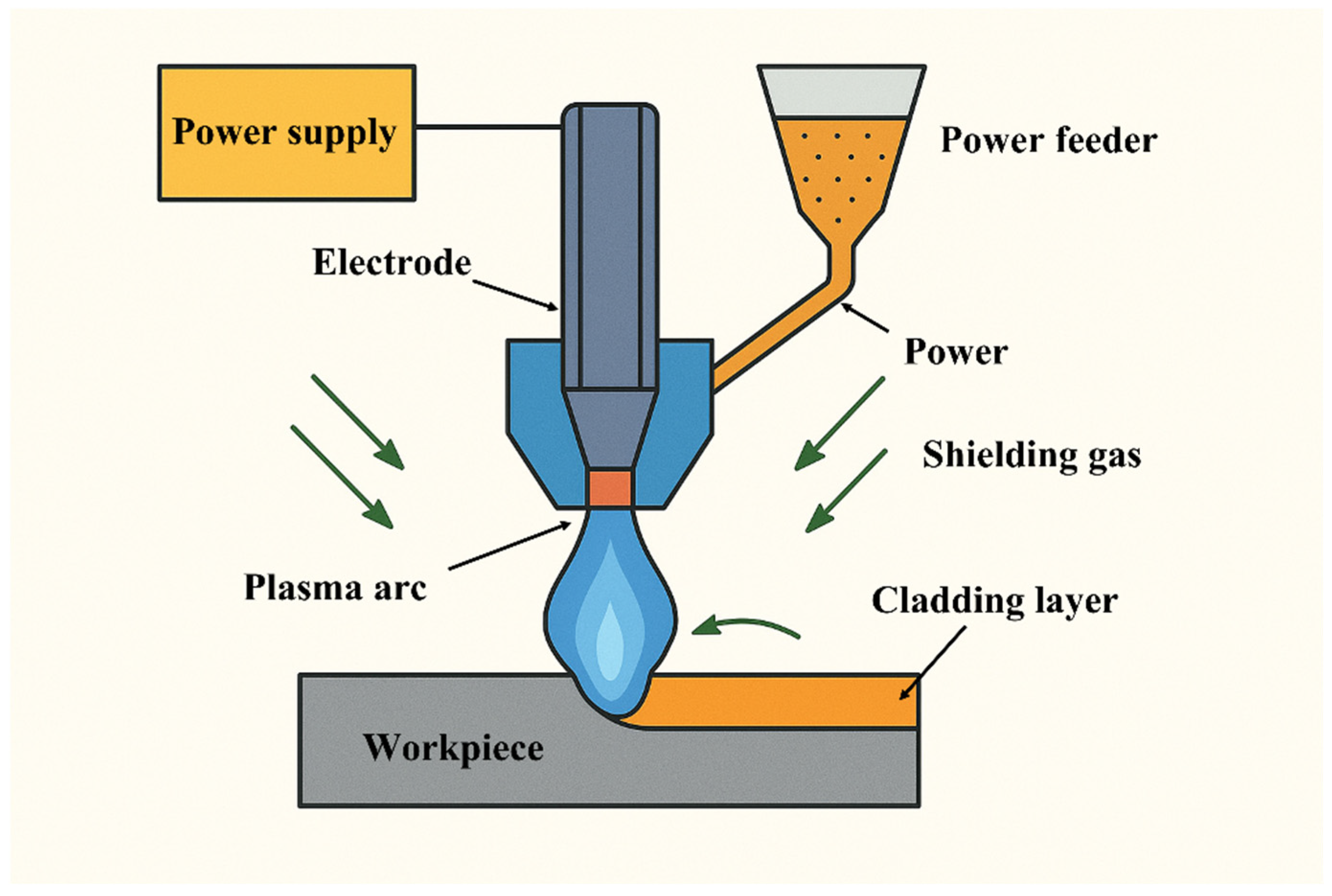

2.1. Materials and PTA Cladding Setup

2.2. Process Parameters and Design of Experiments

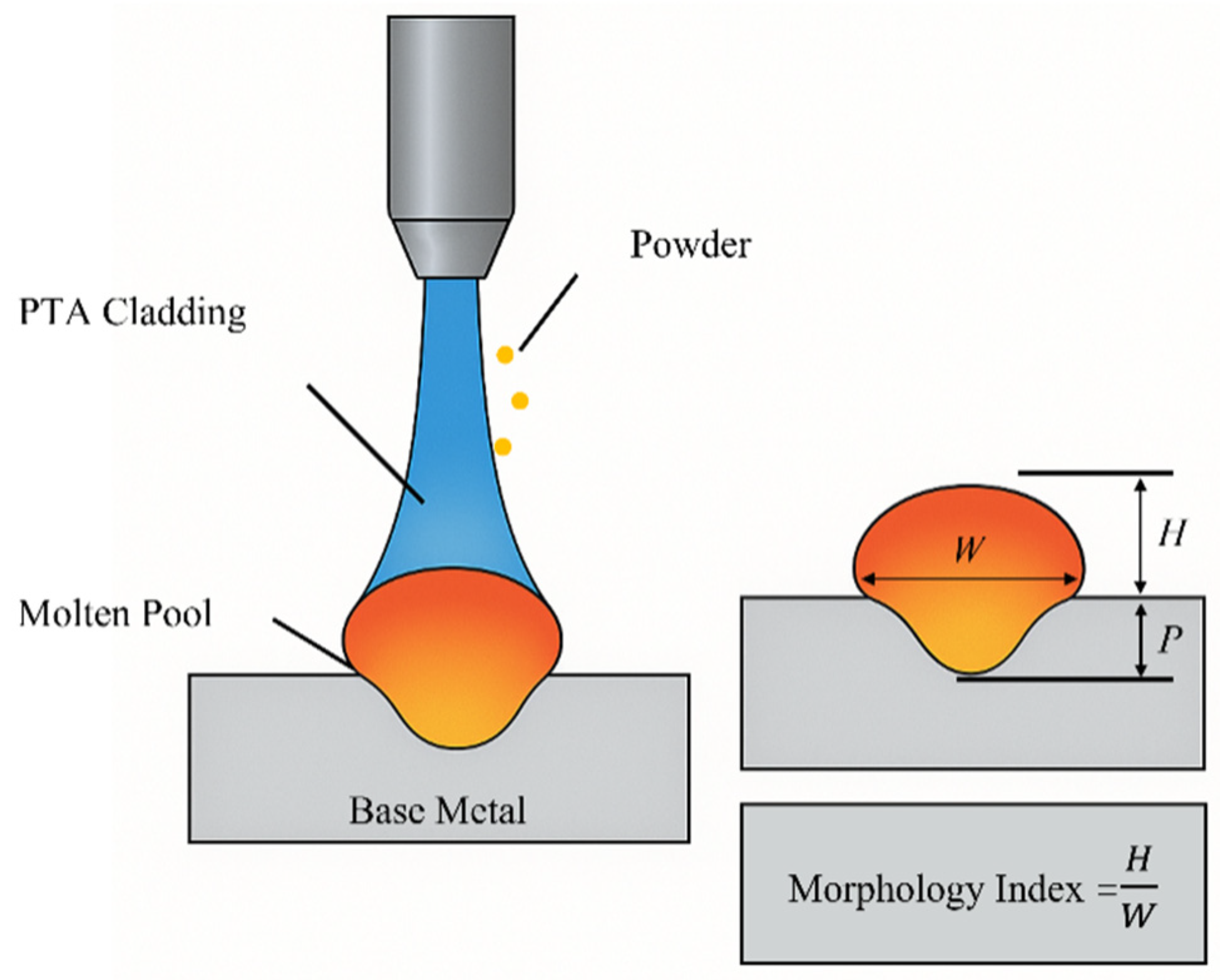

2.3. Construction of Evaluation Metrics for PTAW Bead Geometry

2.3.1. Influence of Process Parameters on Bead Geometry in PTAW

2.3.2. Regression-Based Bead Morphology Evaluation

2.3.3. Dimensionless Evaluation Model for PTA Process Optimization

3. Numerical Simulation Framework

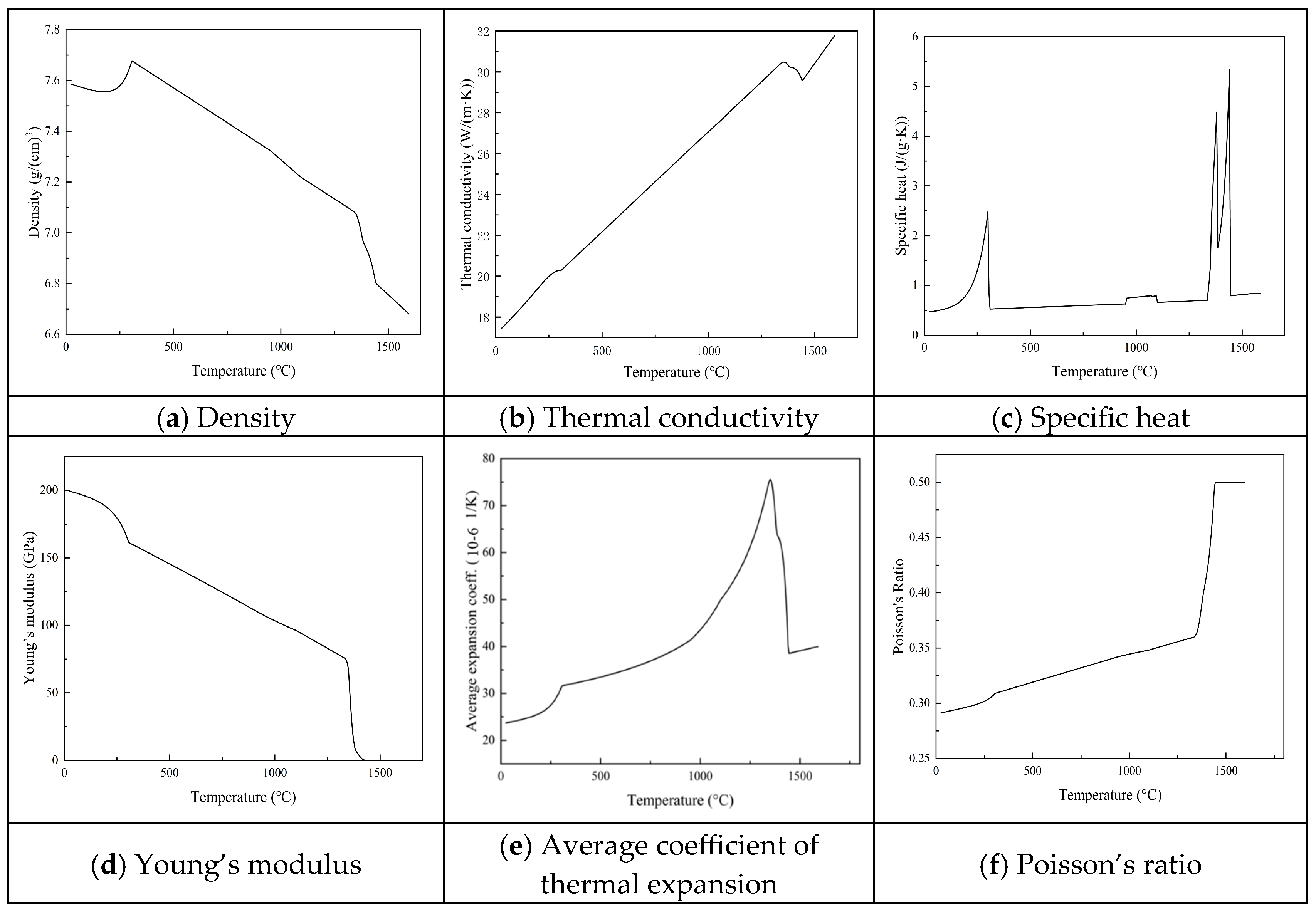

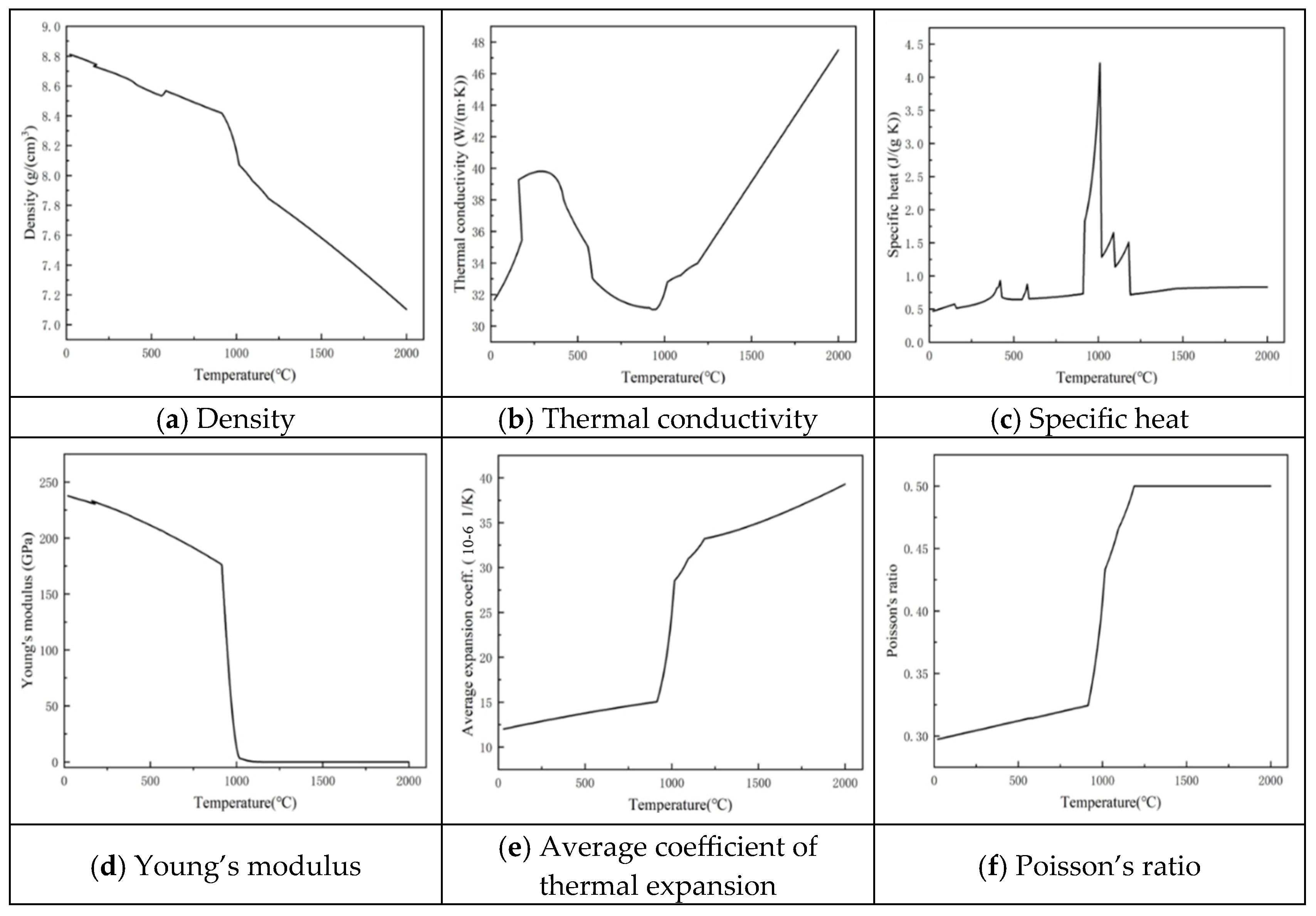

3.1. Governing Equations and Material Constitutive Models

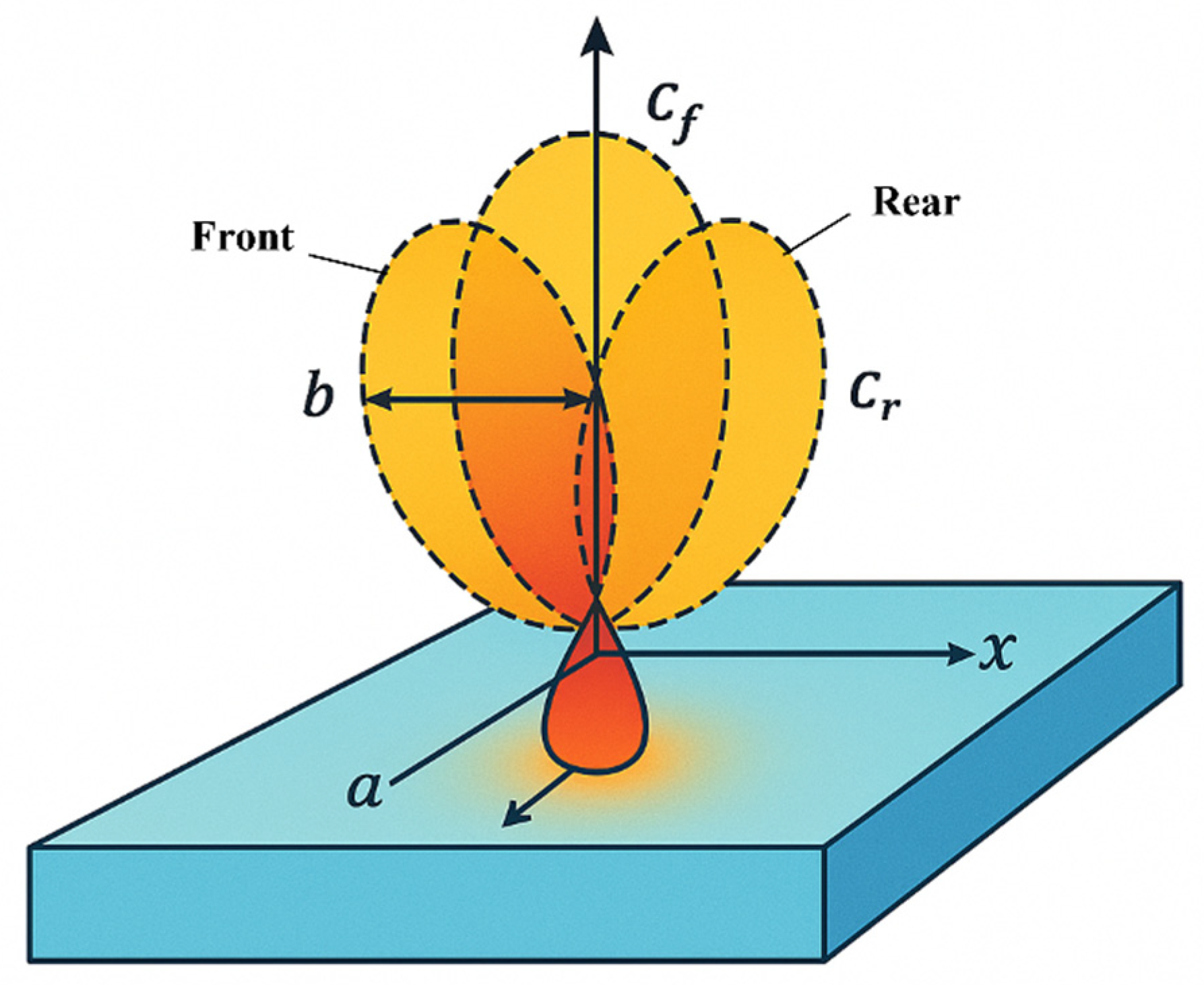

3.2. Heat Source Modeling in PTA Cladding

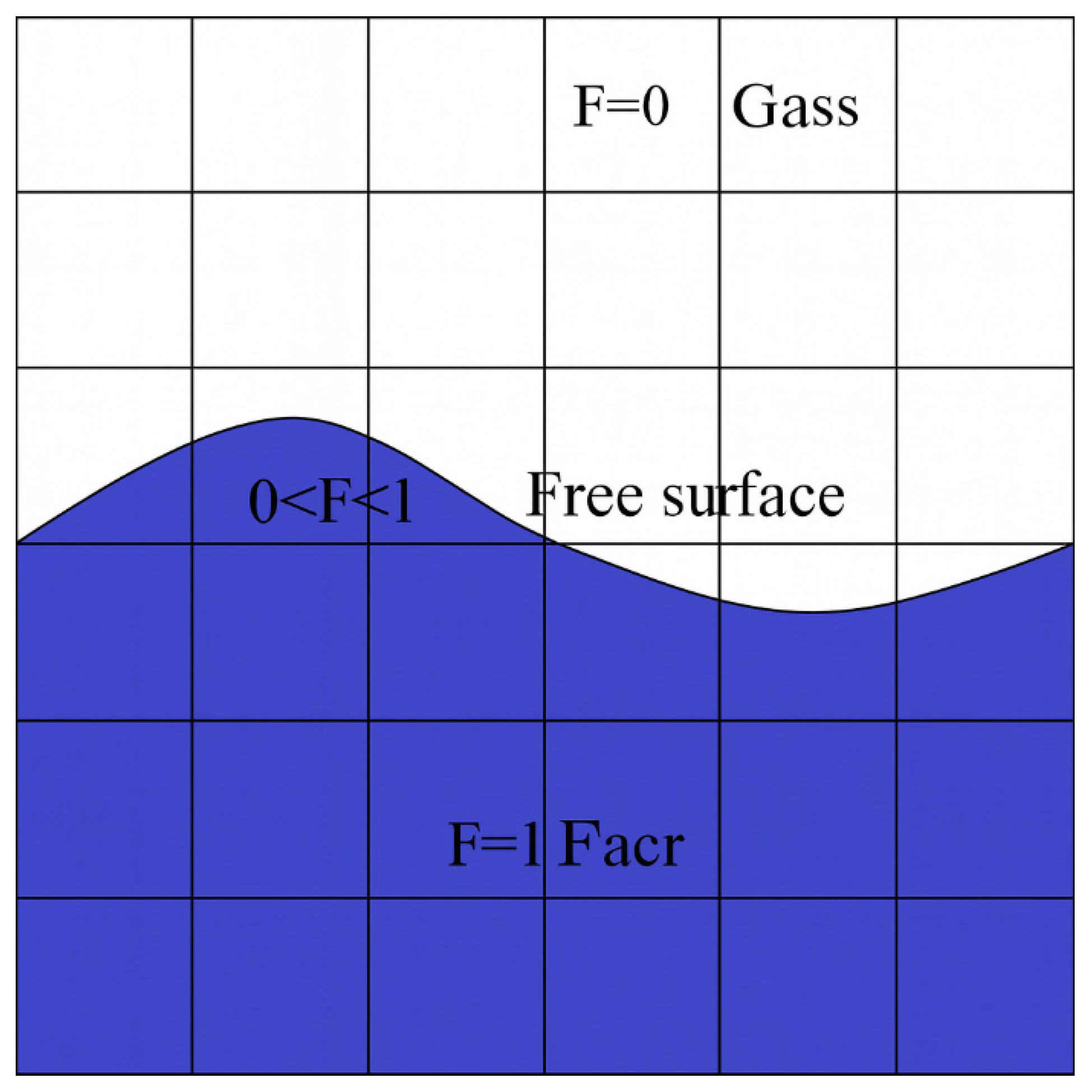

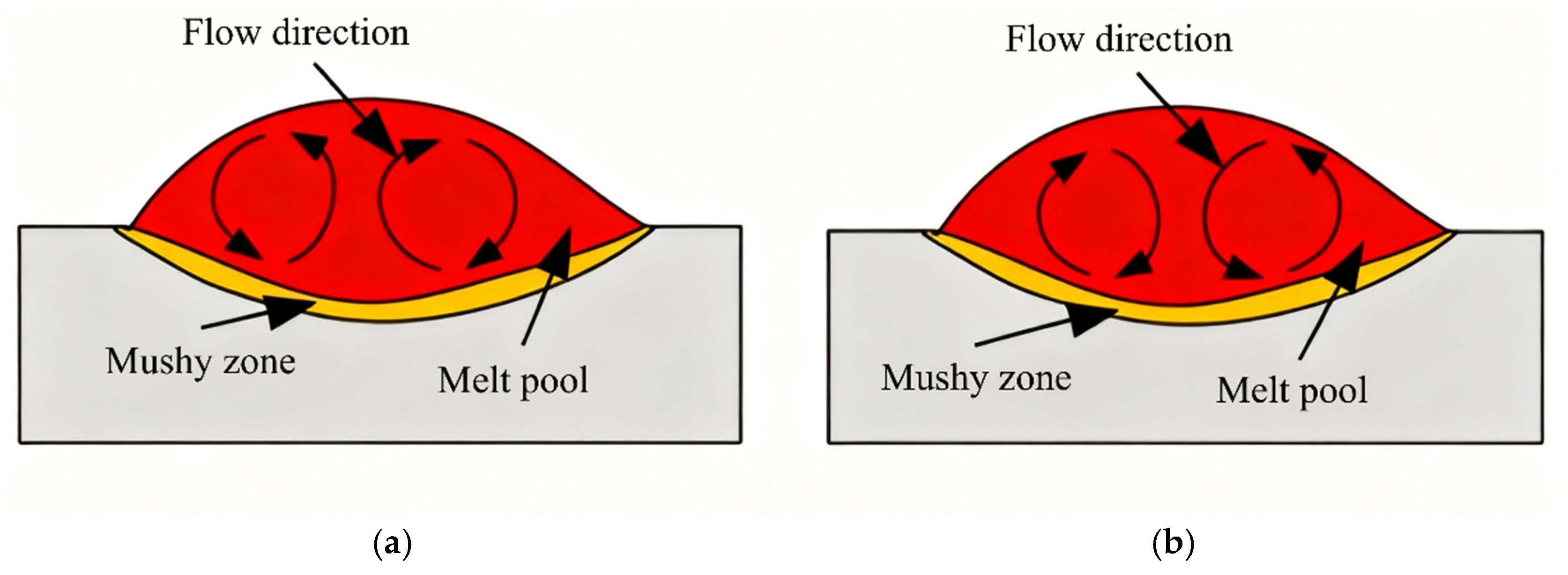

3.3. Melt Pool Evolution and Morphology Description

4. Thermo-Mechanical Modeling and Molten Pool Morphology in Plasma Transferred Arc (PTA) Cladding

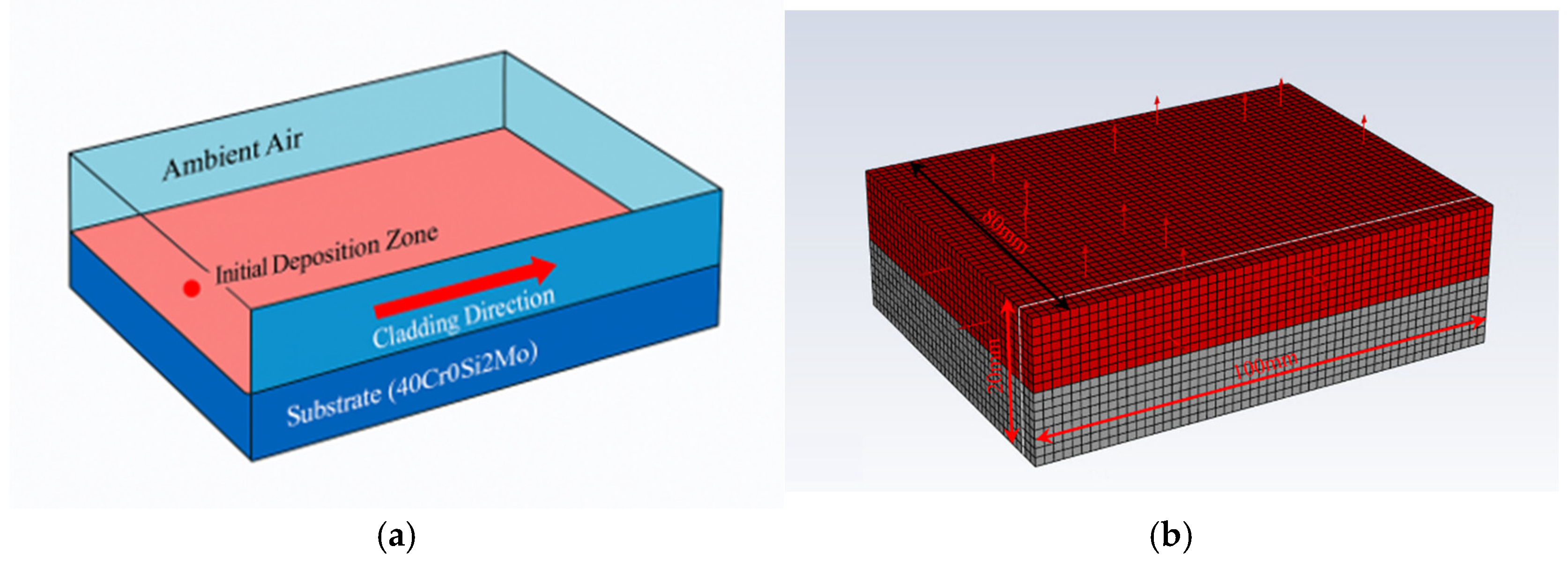

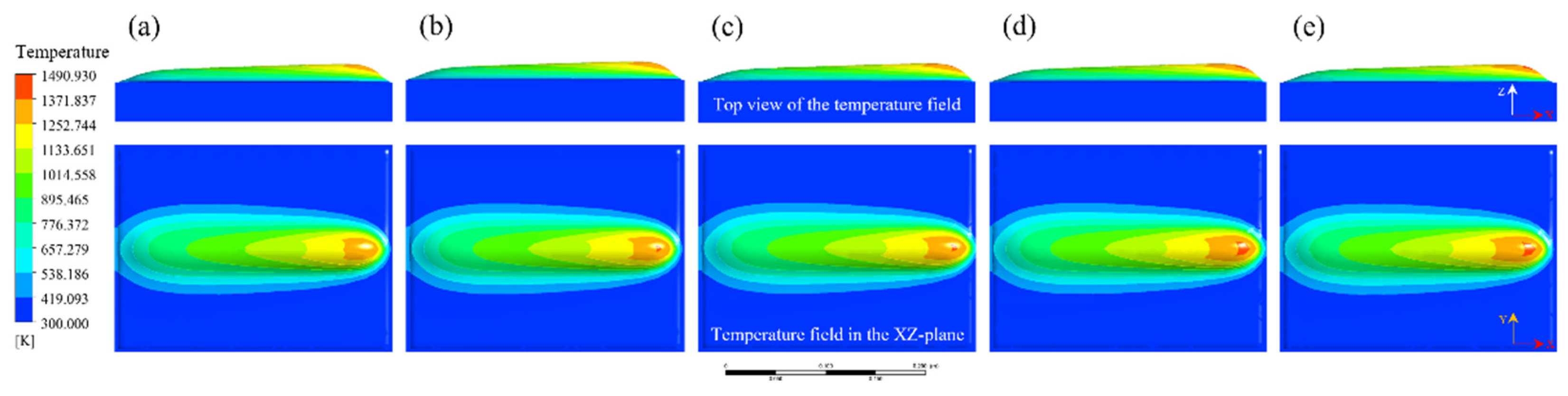

4.1. Development of a Thermo-Mechanical FEM Model for Single-Track PTA Cladding

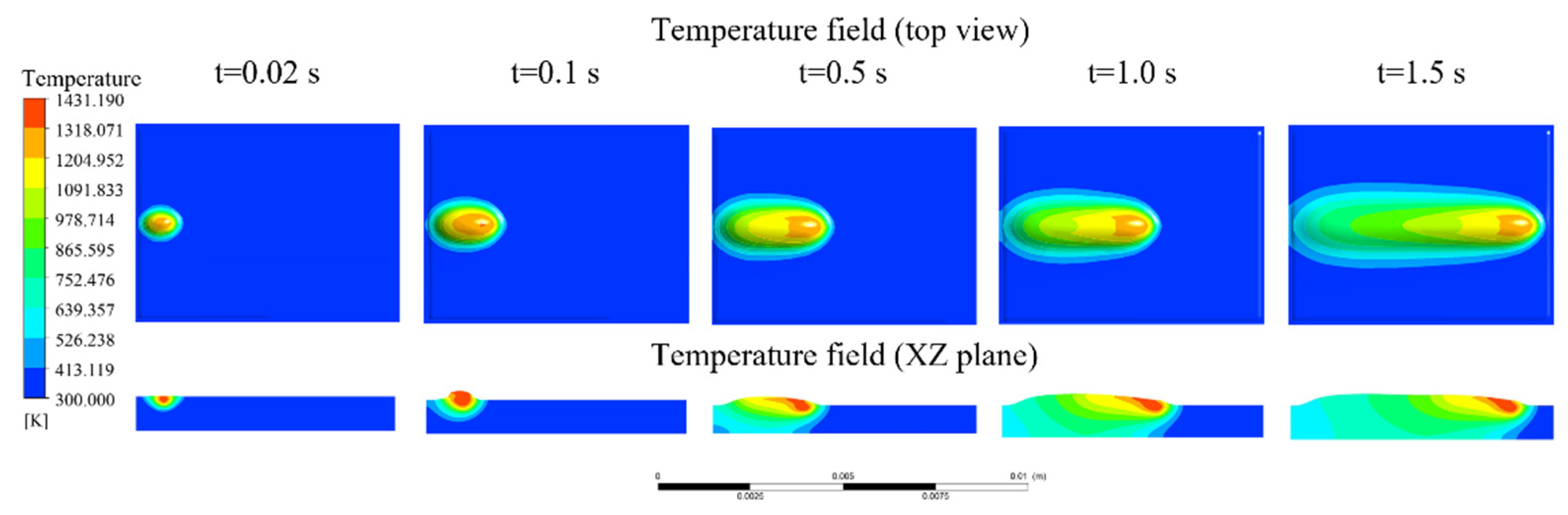

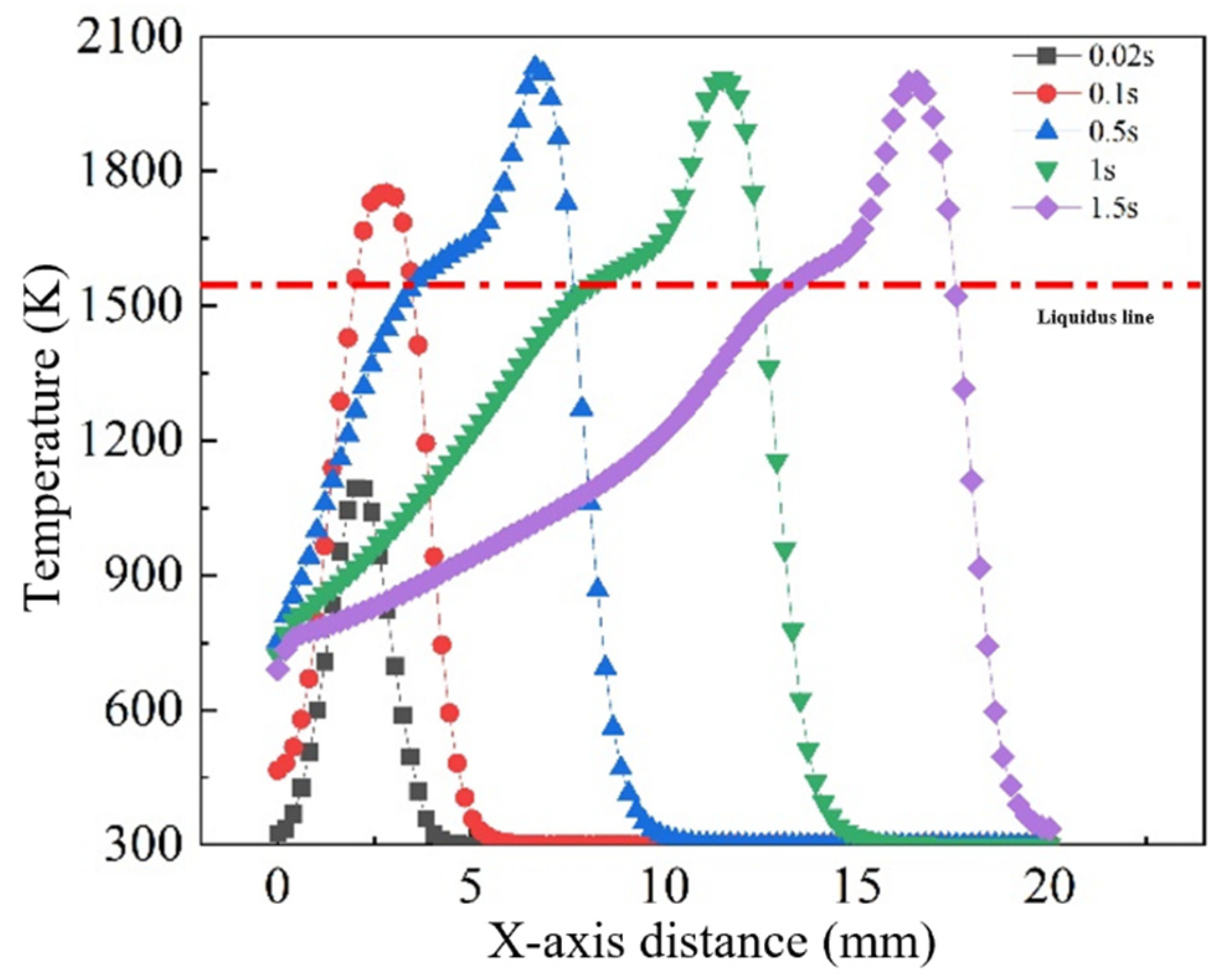

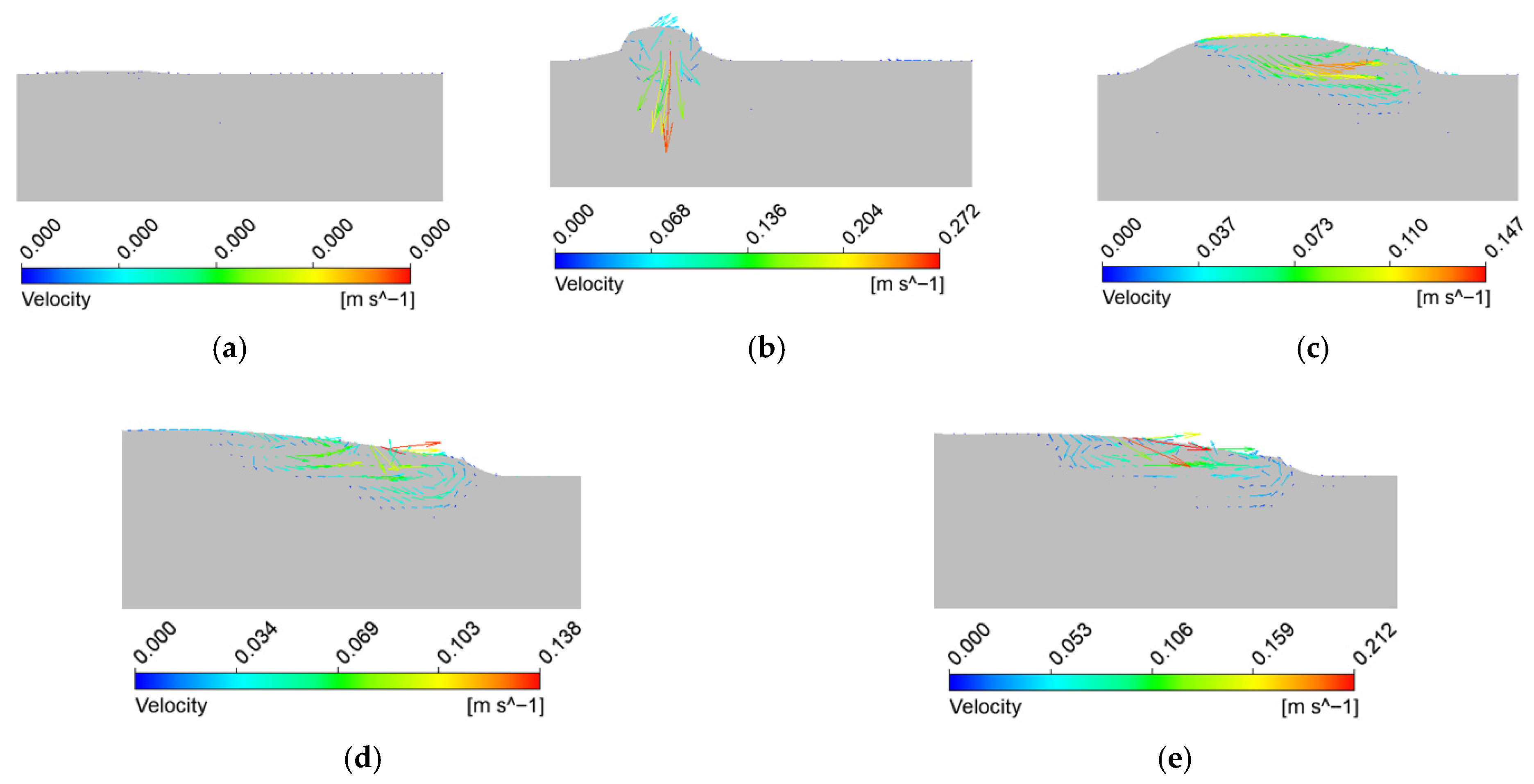

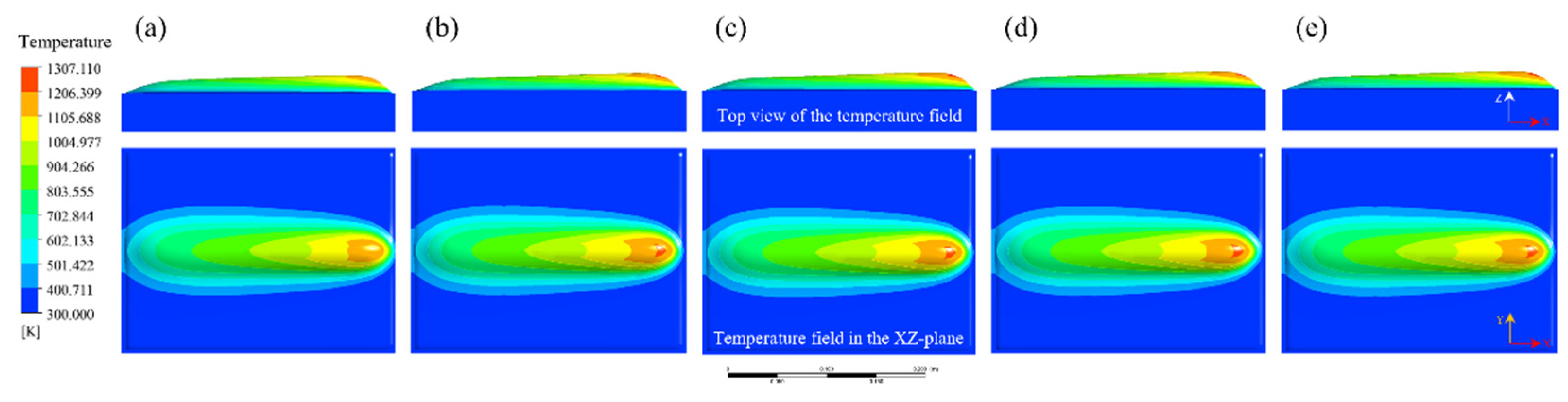

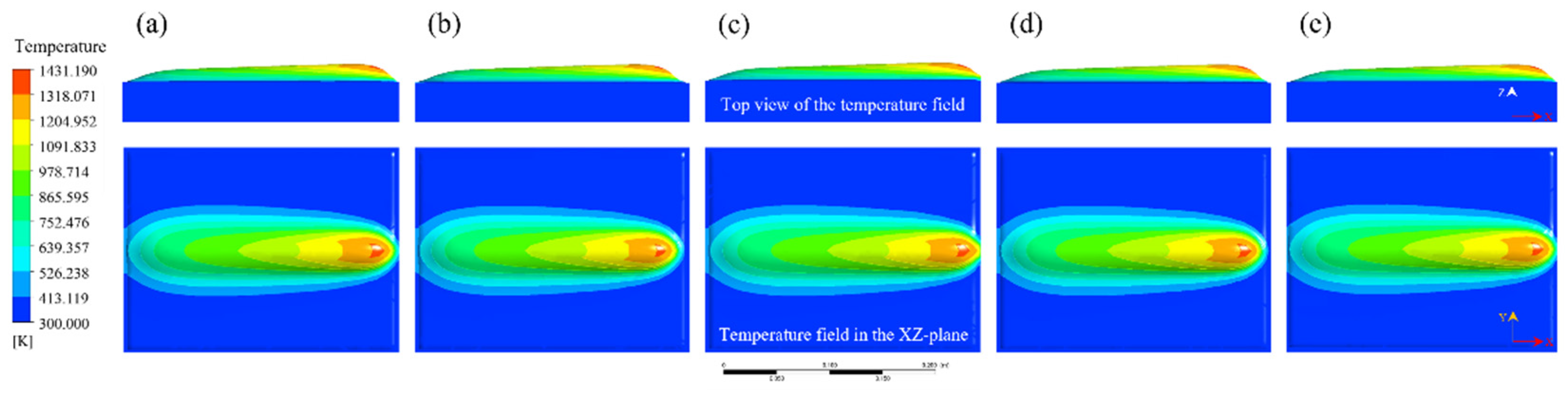

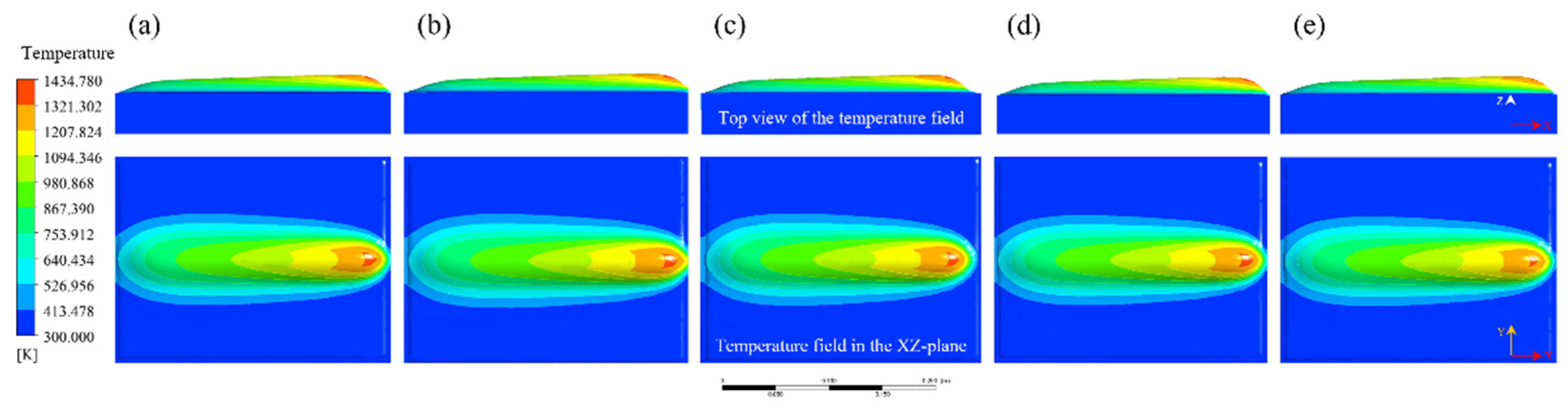

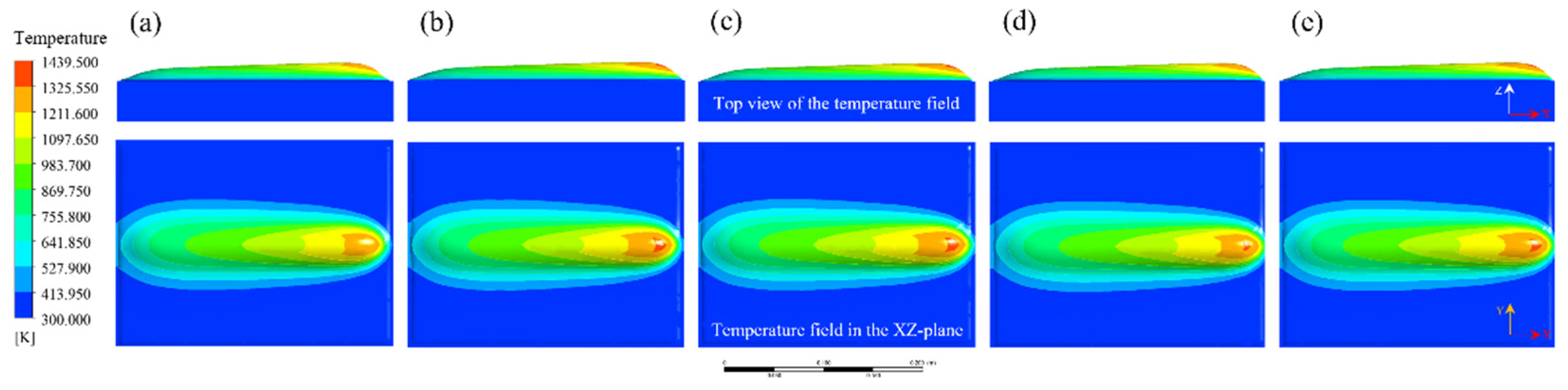

4.2. Evolution of Molten Pool Morphology During Single-Track PTA Cladding

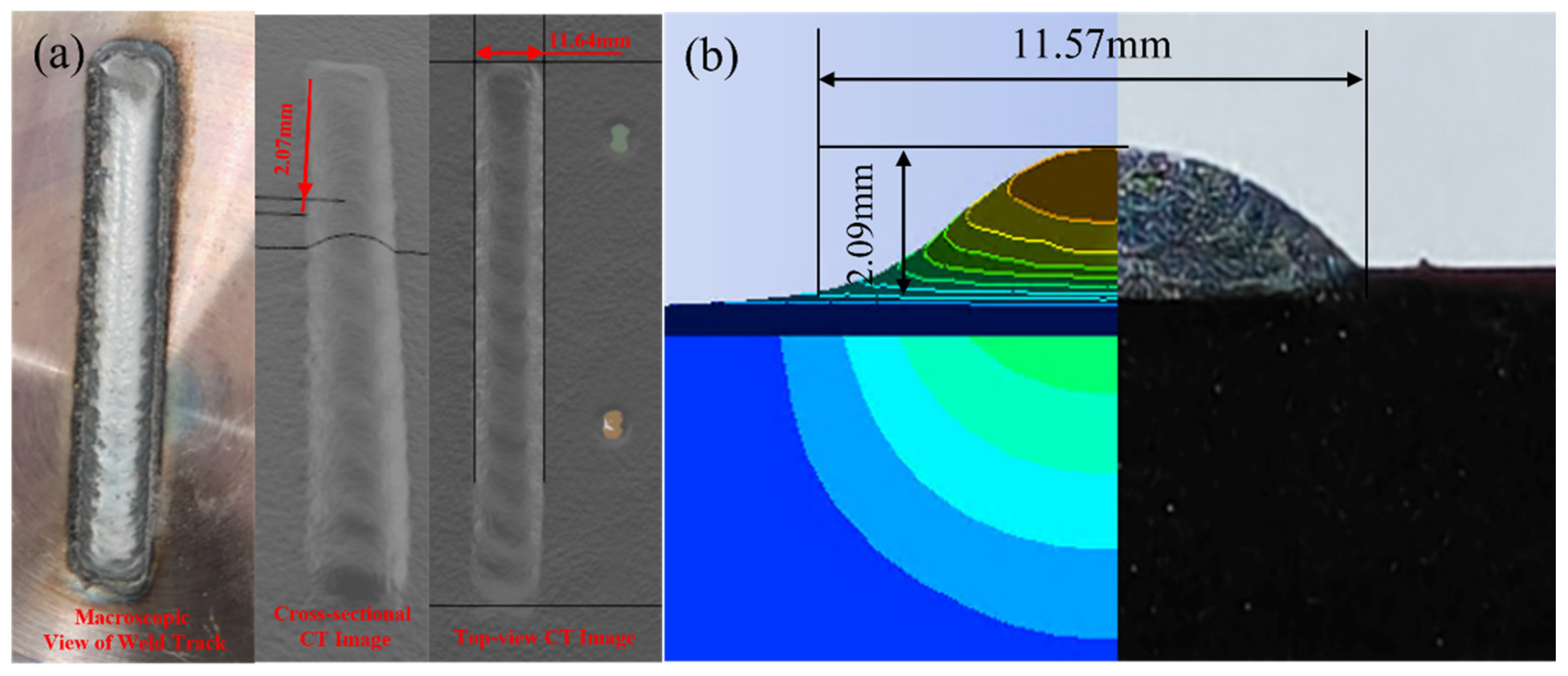

4.3. Experimental Validation of the Thermo-Mechanical Numerical Model

5. Influencing Factors and Evaluation of Coating Morphology in Plasma Cladding

5.1. Influence of Process Parameters on Bead Geometry in Plasma Transferred Arc (PTA) Cladding

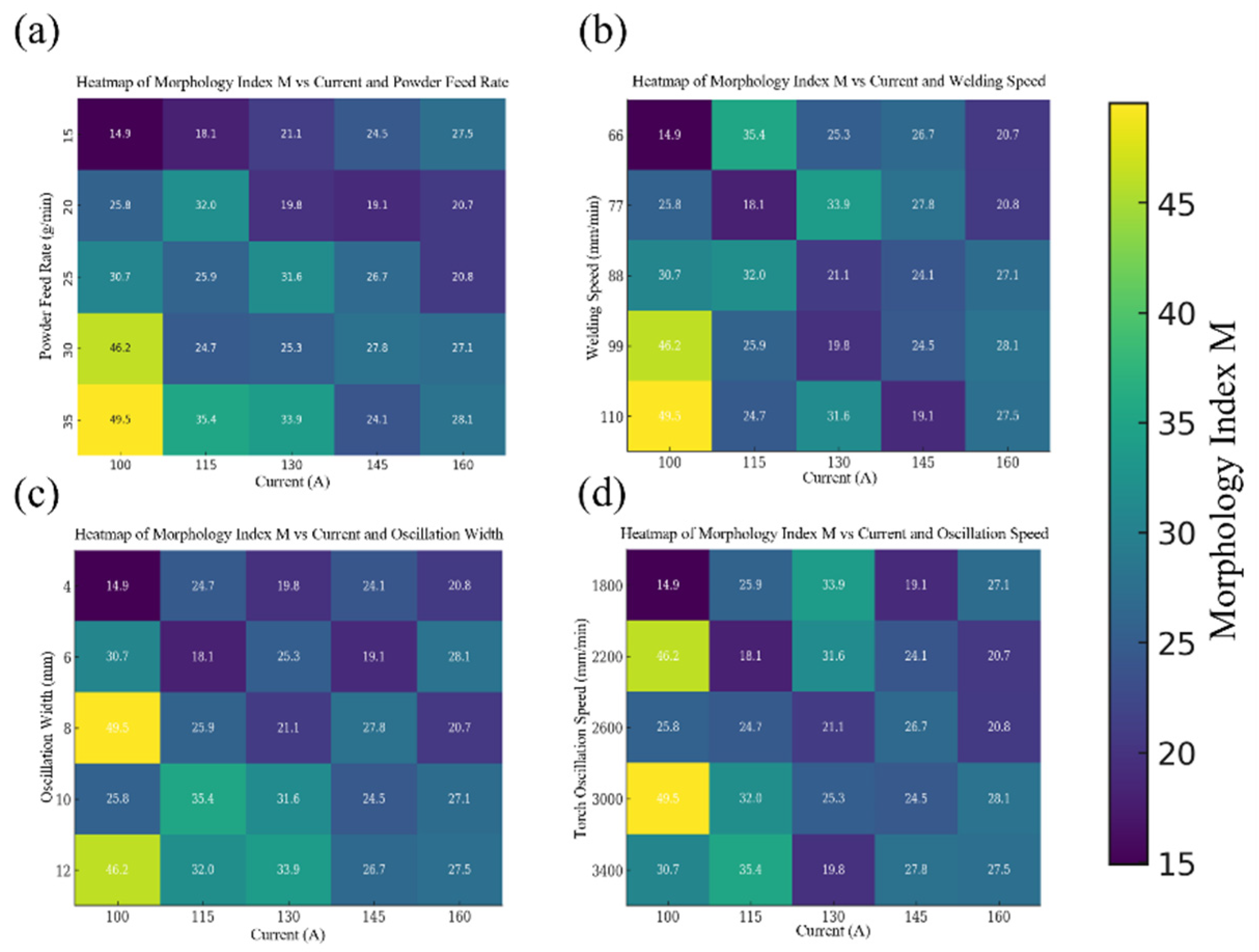

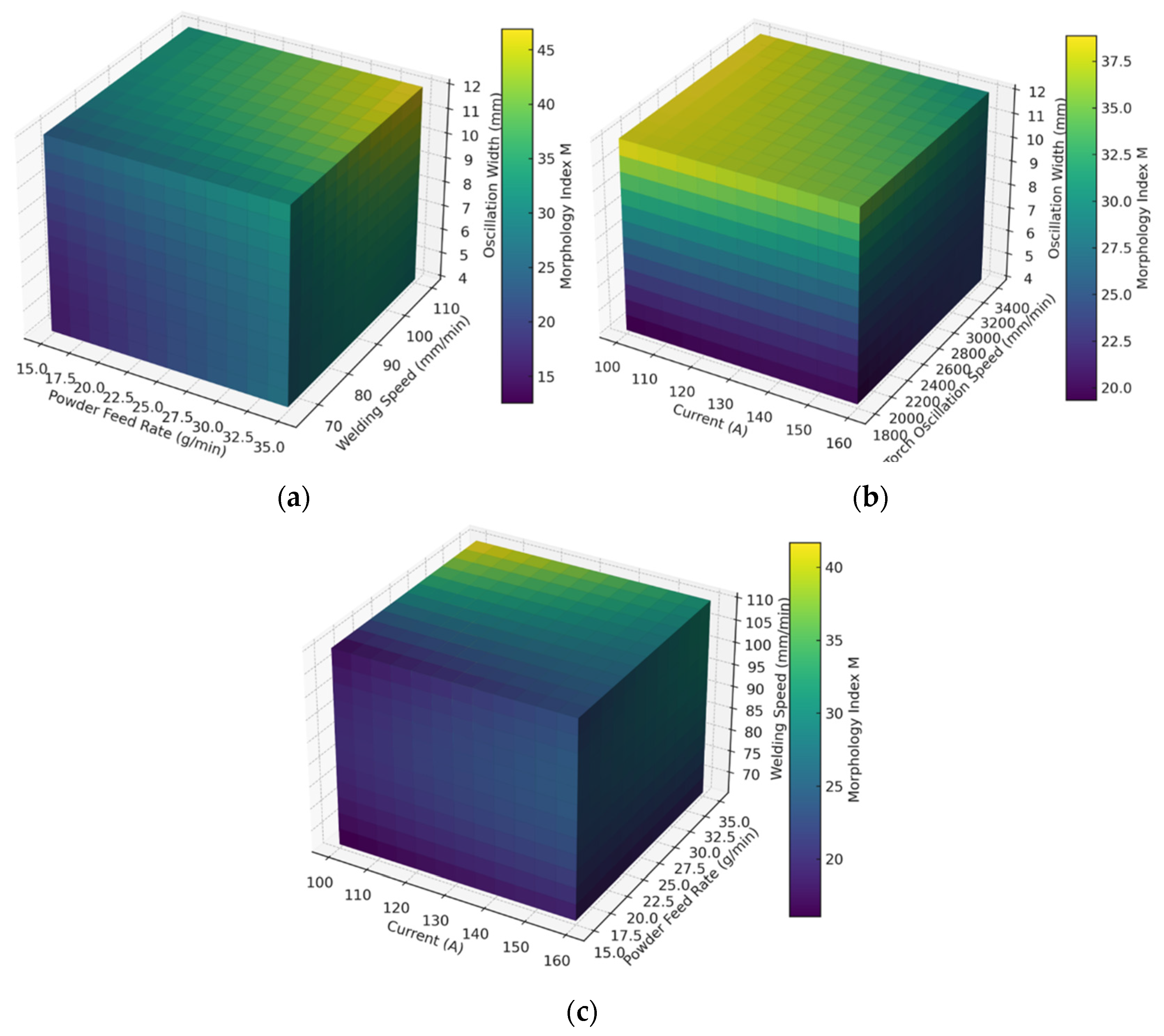

5.2. Analysis of the Morphology Index Response to Key Process Parameters

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matějíček, J.; Antoš, J.; Rohan, P. W + Cu and W + Ni composites and FGMs prepared by plasma transferred arc cladding. Materials 2021, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Soriano, E.M.; Ariza, E.; Arevalo, C.; Montealegre-Melende, I.; Kitzmantel, M.; Neubauer, E. Processing by additive manufacturing based on plasma transferred arc of Hastelloy in Air and Argon Atmosphere. Metals 2020, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, B.; Bhadury, P. Optimization of weld bead parameters of nickel-based overlay deposited by plasma transferred arc surfacing with adequacy test. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2014, 4, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Balaji, D.S.; Harishkumar, J. Study of welding parameters to control the weld bead characteristics in plasma transferred arc powder deposition system using cobalt-based hardfacing alloy. J. Ind. Pollut. Control. 2017, 33, 1676–1681. [Google Scholar]

- Zanzi, K.B.S.; Silva, K.B.; da Cunha, T.V.; Niño Bohórquez, C.E. Effect of plasma transferred arc with powder cladding process parameters on the bead morphology of Inconel 625. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 140, 3593–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Yin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G. Influence of Mo on Ni-15Cr Cladding Layers via Plasma Transferred Arc. Materials 2022, 15, 8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Li, K.; Qian, C.; Li, W. Composite Fe-Cr-V-C coatings prepared by plasma transferred-arc powder surfacing. Materials 2023, 16, 5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Fan, D.; Huang, J.; Yu, S.; Yuan, W.; Han, M. Self-Adaptive Control System for Additive Manufacturing Using Double Electrode Micro Plasma Arc Welding. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 34, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Hou, Q.; Wang, P. Cr3C2-modified Ni-base coating by PTA: Microstructure and properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 2993–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.J. Taguchi Techniques for Quality Engineering, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, G.; Chowdhury, S.; Wu, Y. Taguchi’s Quality Engineering Handbook; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 10th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Li, K.; Qian, C.; Li, W. Composite Fe–Cr–V–C coatings by PTA surfacing: Microstructure and properties. Coatings 2023, 13, 1135. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, H.; Vargas, Z.; Valdez, S.; Serrano, M.; Del Pozo, A.; Alcántara, M. Taguchi, Grey Relational Analysis, and ANOVA Optimization of TIG Welding Parameters to Maximize Mechanical Performance of Al-6061 T6 Alloy. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahiti, M.; Raghavendra Reddy, M.; Joshi, B.; Nageswara Rao, B. Application of Taguchi Method for Optimum Weld Process Parameters of Pure Aluminum. Am. J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 2017, 1, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.; Aliyev, A.; Zeidler, H.; Krinke, S. Recent developments and challenges in wire arc additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, D.; Gao, P.; Naumov, A.; Li, Q.; Li, F.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Microstructure and properties of FeAlC-x(WC-Co) composite coating prepared through plasma transferred arc cladding. Coatings 2024, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Dong, B.; Qiu, Z.; Garbe, U.; Pan, Z.; Li, H. Microstructural characteristics of WC-Cu cladding on mild steel substrate prepared through plasma transferred arc welding. Metals 2025, 15, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Tian, J.; Liu, Z.; Song, G.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y. Comparative analysis of the microstructure and tribological behaviors of Ni-, Fe-, and Co-based plasma cladding coatings. Metals 2025, 15, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-J.; Lin, H.-M. Effects of niobium carbide additions on Ni-based superalloys: A study on microstructures and cutting-wear characteristics through plasma-transferred-arc-assisted deposition. Coatings 2024, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treutler, K. Plasma powder transferred arc additive manufacturing of ((Fe, Ni)-Al) intermetallic alloy and resulting properties. Weld World 2024, 68, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelamasetti, B.; Sandeep, M.; Narella, S.S.; Varada Varied, V.; Tushar, V. Optimization of TIG welding process parameters using Taguchi technique for the joining of dissimilar metals of AA5083 and AA7075. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SaediArdahaei, S.; Pham, X.-T. Multi-response optimization of aluminum laser spot welding with sinusoidal and cosinusoidal power profiles based on Taguchi–grey relational analysis. Materials 2025, 18, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillard, F.; Duprey, B.; Courouau, J.-L.; Robin, R.; Aubry, P.; Blanc, C.; Tabarant, M.; Maskrot, H.; Nicolas, L.; Blat-Yrieix, M.; et al. Evaluation of cobalt-free coatings as hardfacing material candidates in sodium-cooled fast reactor and effect of oxygen in sodium on the tribological behaviour. EPJ Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | B | C | Cr | Fe | Ni | Si | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt.%) | 1.9 | 0.90 | 18.0 | 5.4 | Bal. | 5.3 | trace |

| Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Ni | Cr | Cu | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt.%) | 0.43 | 3.14 | 0.50 | 0.023 | 0.002 | 0.21 | 8.62 | 0.033 | Bal. |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Main arc current (A) | 120 |

| Traverse speed (mm·min−1) | 120 |

| Powder feed rate (g·min−1) | 8.0 |

| Oscillation amplitude (mm) | 5 |

| Plasma gas flow (L·min−1) | 3 (Ar/2%H2) |

| Shielding gas flow (L·min−1) | 10 |

| Preheat temperature (°C) | 150 |

| Ambient temperature (K) | 293.15 |

| Number | Current (A) | Powder Feed Rate (g/min) | Welding Speed (mm/min) | Torch Oscillation Speed (mm/min) | Oscillation Width (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100.0 | 15.0 | 66.0 | 1800.0 | 4.0 |

| 2 | 100.0 | 20.0 | 77.0 | 2600.0 | 10.0 |

| 3 | 100.0 | 25.0 | 88.0 | 3400.0 | 6.0 |

| 4 | 100.0 | 30.0 | 99.0 | 2200.0 | 12.0 |

| 5 | 100.0 | 35.0 | 110.0 | 3000.0 | 8.0 |

| 6 | 115.0 | 15.0 | 77.0 | 2200.0 | 6.0 |

| 7 | 115.0 | 20.0 | 88.0 | 3000.0 | 12.0 |

| 8 | 115.0 | 25.0 | 99.0 | 1800.0 | 8.0 |

| 9 | 115.0 | 30.0 | 110.0 | 2600.0 | 4.0 |

| 10 | 115.0 | 35.0 | 66.0 | 3400.0 | 10.0 |

| 11 | 130.0 | 15.0 | 88.0 | 2600.0 | 8.0 |

| 12 | 130.0 | 20.0 | 99.0 | 3400.0 | 4.0 |

| 13 | 130.0 | 25.0 | 110.0 | 2200.0 | 10.0 |

| 14 | 130.0 | 30.0 | 66.0 | 3000.0 | 6.0 |

| 15 | 130.0 | 35.0 | 77.0 | 1800.0 | 12.0 |

| 16 | 145.0 | 15.0 | 99.0 | 3000.0 | 10.0 |

| 17 | 145.0 | 20.0 | 110.0 | 1800.0 | 6.0 |

| 18 | 145.0 | 25.0 | 66.0 | 2600.0 | 12.0 |

| 19 | 145.0 | 30.0 | 77.0 | 3400.0 | 8.0 |

| 20 | 145.0 | 35.0 | 88.0 | 2200.0 | 4.0 |

| 21 | 160.0 | 15.0 | 110.0 | 3400.0 | 12.0 |

| 22 | 160.0 | 20.0 | 66.0 | 2200.0 | 8.0 |

| 23 | 160.0 | 25.0 | 77.0 | 3000.0 | 4.0 |

| 24 | 160.0 | 30.0 | 88.0 | 1800.0 | 10.0 |

| 25 | 160.0 | 35.0 | 99.0 | 2600.0 | 6.0 |

| Metric | Experimental | Simulation | Absolute Error | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cladding Width (mm) | 11.64 | 11.57 | 0.07 | 0.60% |

| Cladding Height (mm) | 2.07 | 2.09 | 0.02 | 0.97% |

| Number | Bead Height H (mm) | Bead Width W (mm) | Penetration Depth P (mm) | Morphology Index M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.87 | 10.67 | 1.34 | 14.89 |

| 2 | 1.94 | 11.59 | 0.87 | 25.84 |

| 3 | 2.11 | 11.64 | 0.8 | 30.7 |

| 4 | 2.07 | 11.84 | 0.53 | 46.24 |

| 5 | 2.16 | 11.47 | 0.5 | 49.55 |

| Number | Bead Height H (mm) | Bead Width W (mm) | Penetration Depth P (mm) | Morphology Index M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 2.06 | 10.71 | 1.22 | 18.09 |

| 7 | 2.0 | 12.0 | 0.75 | 31.99 |

| 8 | 2.09 | 10.91 | 0.88 | 25.92 |

| 9 | 2.03 | 9.85 | 0.81 | 24.67 |

| 10 | 2.48 | 12.0 | 0.84 | 35.38 |

| Number | Bead Height H (mm) | Bead Width W (mm) | Penetration Depth P (mm) | Morphology Index M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 2.03 | 11.44 | 1.1 | 21.12 |

| 12 | 1.97 | 10.38 | 1.03 | 19.84 |

| 13 | 2.06 | 11.64 | 0.76 | 31.56 |

| 14 | 2.51 | 12.0 | 1.19 | 25.28 |

| 15 | 2.6 | 12.0 | 0.92 | 33.89 |

| Number | Bead Height H (mm) | Bead Width W (mm) | Penetration Depth P (mm) | Morphology Index M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 2.0 | 12.0 | 0.98 | 24.48 |

| 17 | 2.09 | 10.11 | 1.11 | 19.05 |

| 18 | 2.54 | 12.0 | 1.14 | 26.71 |

| 19 | 2.48 | 12.0 | 1.07 | 27.77 |

| 20 | 2.57 | 11.24 | 1.2 | 24.06 |

| Number | Bead Height H (mm) | Bead Width W (mm) | Penetration Depth P (mm) | Morphology Index M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 1.97 | 12.0 | 0.86 | 27.48 |

| 22 | 2.57 | 12.0 | 1.49 | 20.68 |

| 23 | 2.51 | 11.77 | 1.42 | 20.79 |

| 24 | 2.6 | 12.0 | 1.15 | 27.11 |

| 25 | 2.54 | 11.97 | 1.08 | 28.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, L.; Long, J.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, F. Integrative Evaluation of Bead Morphology in Plasma Transferred Arc Cladding Through Orthogonal Arrays and Morphology Index Analysis. Materials 2025, 18, 5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225155

Jiang L, Long J, Wei Y, Jiang Q, Wang F. Integrative Evaluation of Bead Morphology in Plasma Transferred Arc Cladding Through Orthogonal Arrays and Morphology Index Analysis. Materials. 2025; 18(22):5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225155

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Lihe, Jinwei Long, Yanhong Wei, Qian Jiang, and Fangxuan Wang. 2025. "Integrative Evaluation of Bead Morphology in Plasma Transferred Arc Cladding Through Orthogonal Arrays and Morphology Index Analysis" Materials 18, no. 22: 5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225155

APA StyleJiang, L., Long, J., Wei, Y., Jiang, Q., & Wang, F. (2025). Integrative Evaluation of Bead Morphology in Plasma Transferred Arc Cladding Through Orthogonal Arrays and Morphology Index Analysis. Materials, 18(22), 5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225155