Enhancing the Printability of Laser Powder Bed Fusion-Processed Aluminum 7xxx Series Alloys Using Grain Refinement and Eutectic Solidification Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CALPHAD-Based Alloy Design Approach for LPBF

2.2. Compositions of Interest

2.3. Materials

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.5. LPBF Experiments

2.6. Microstructural Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

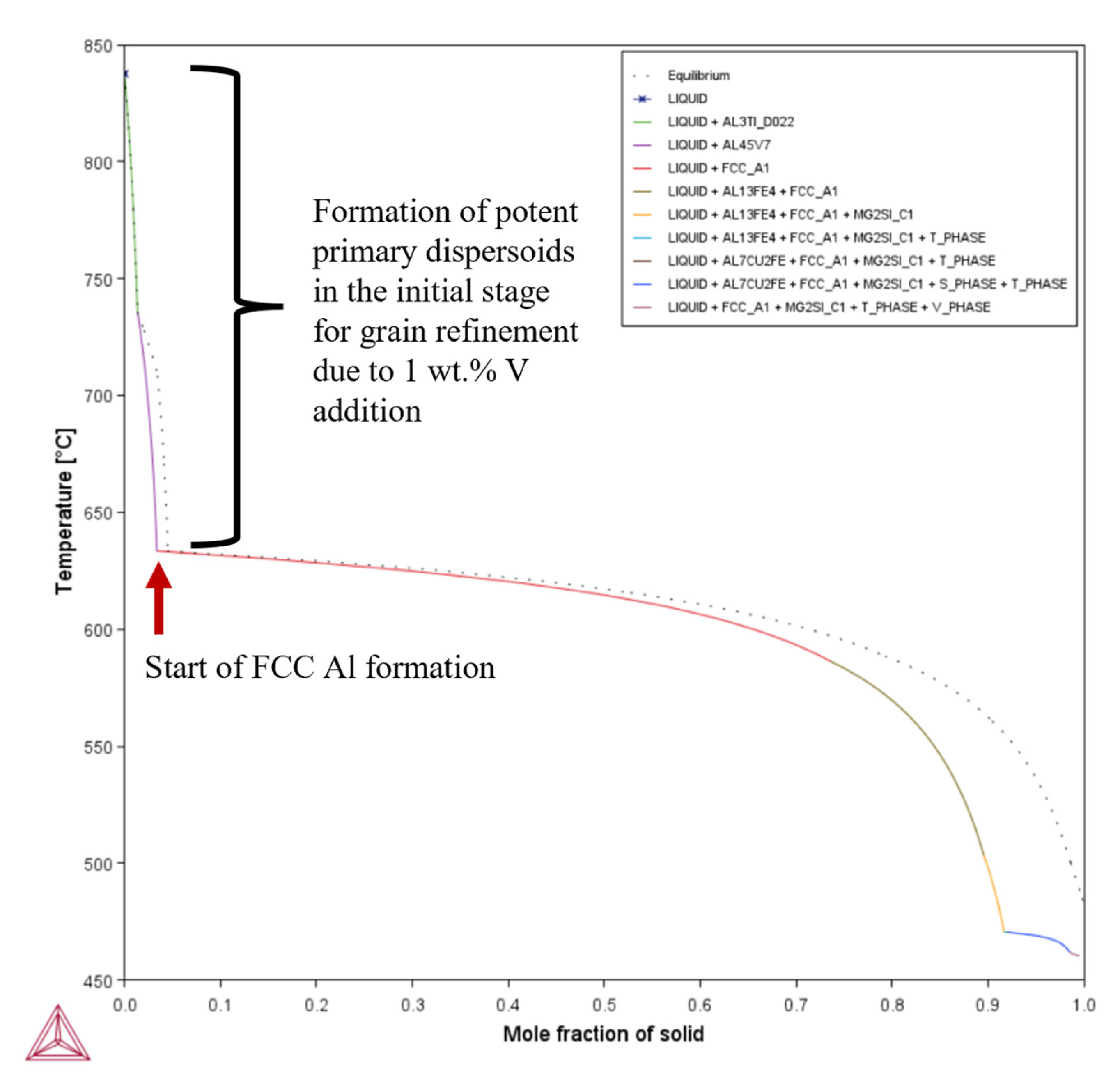

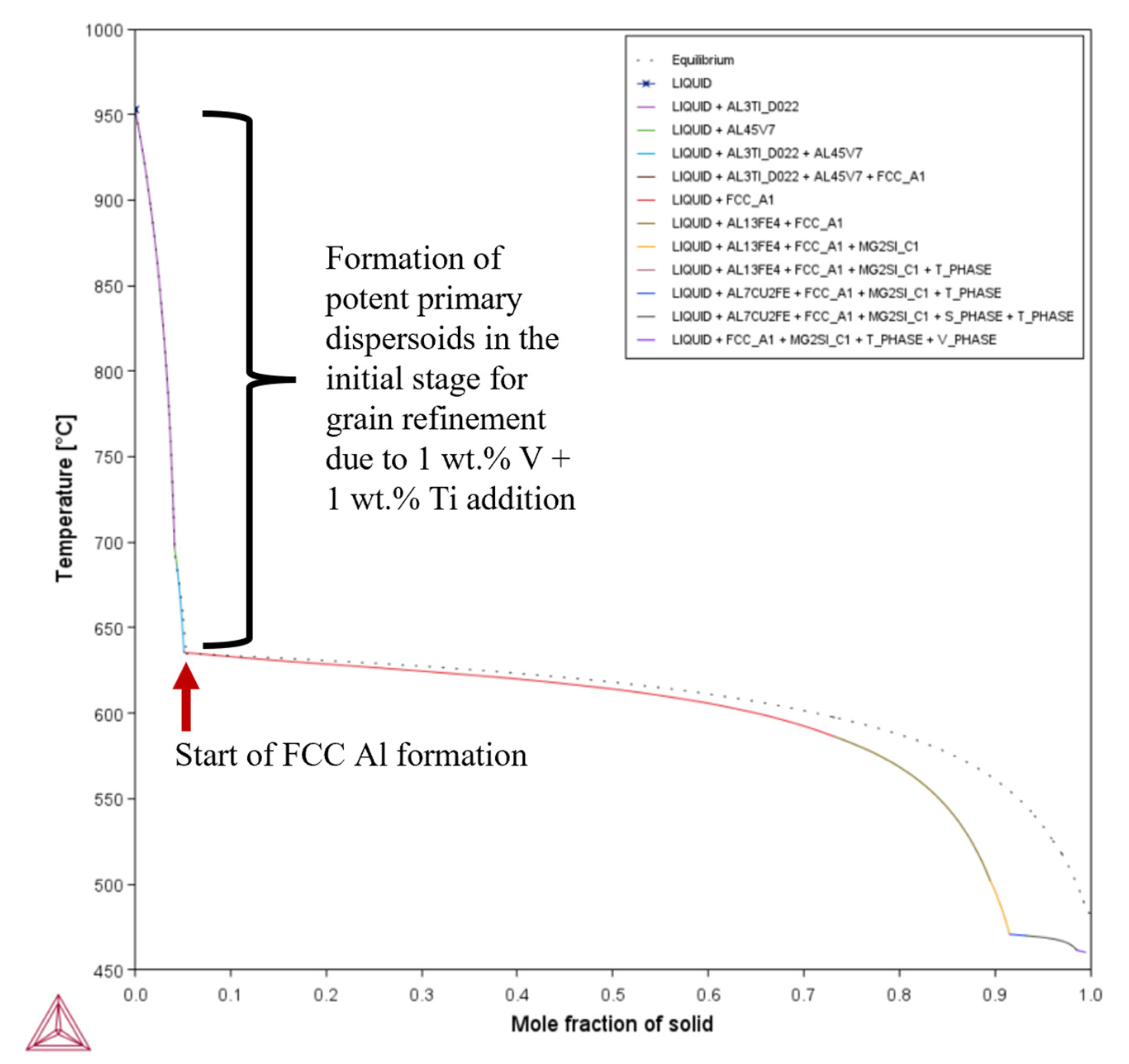

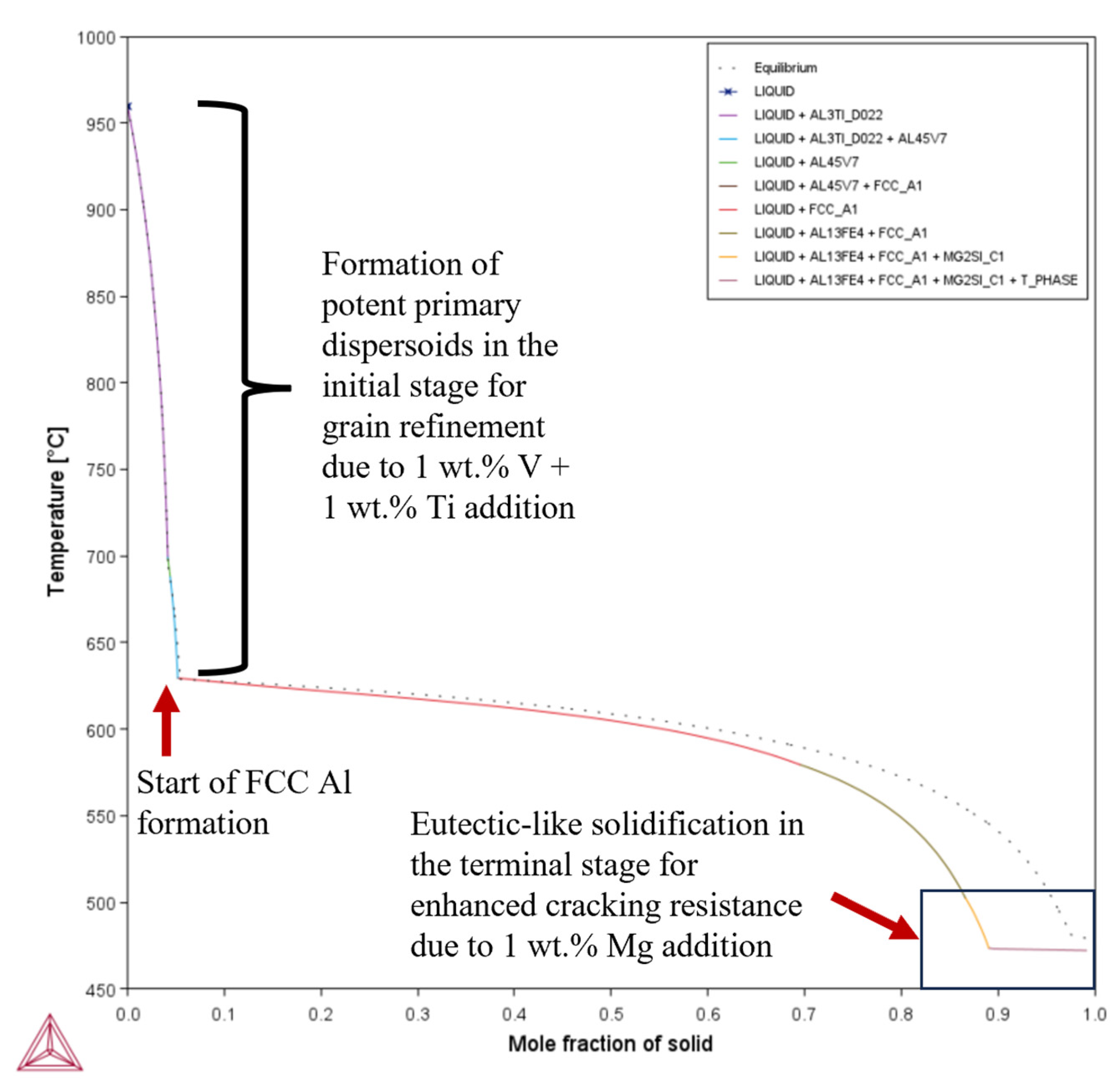

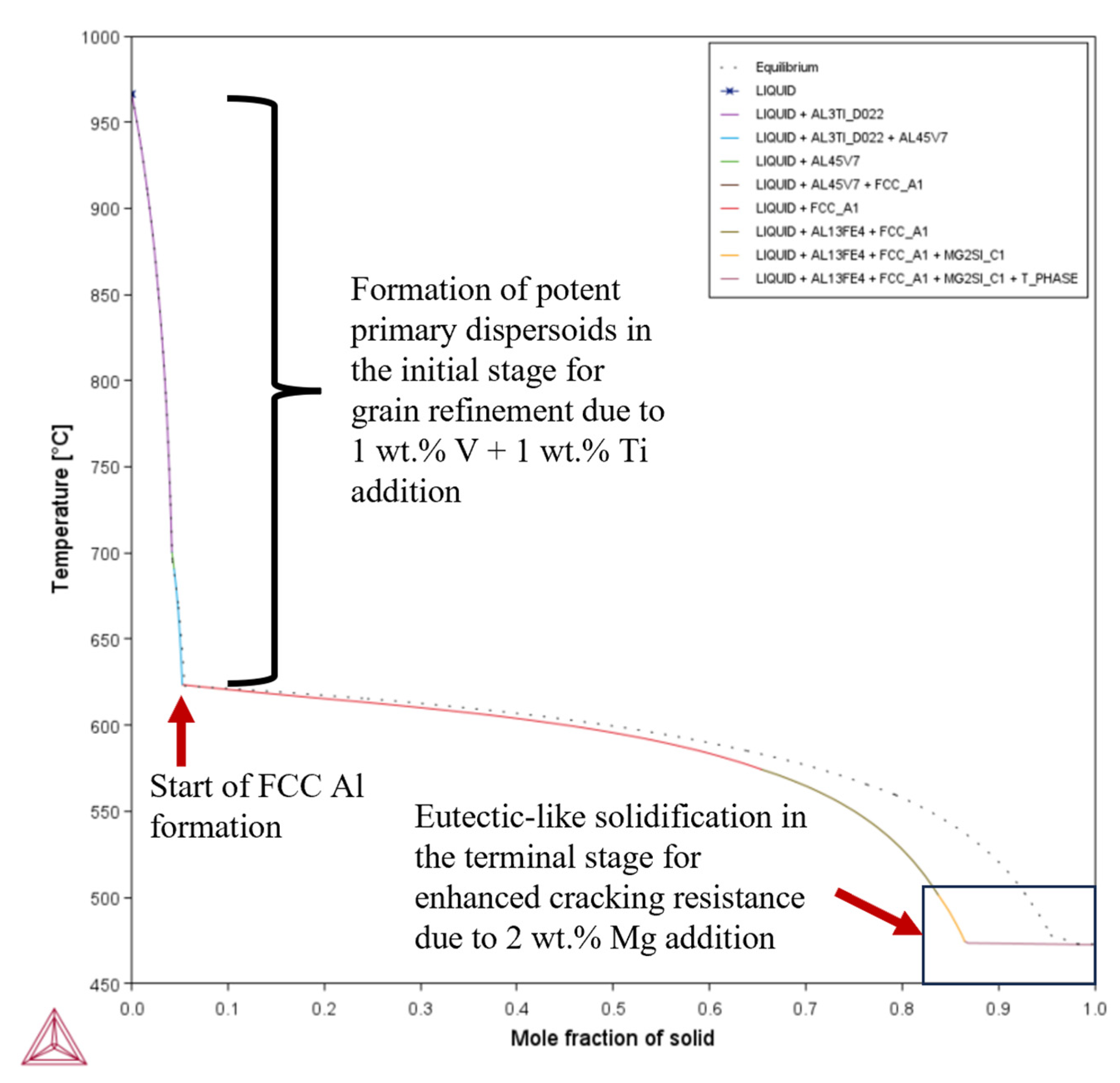

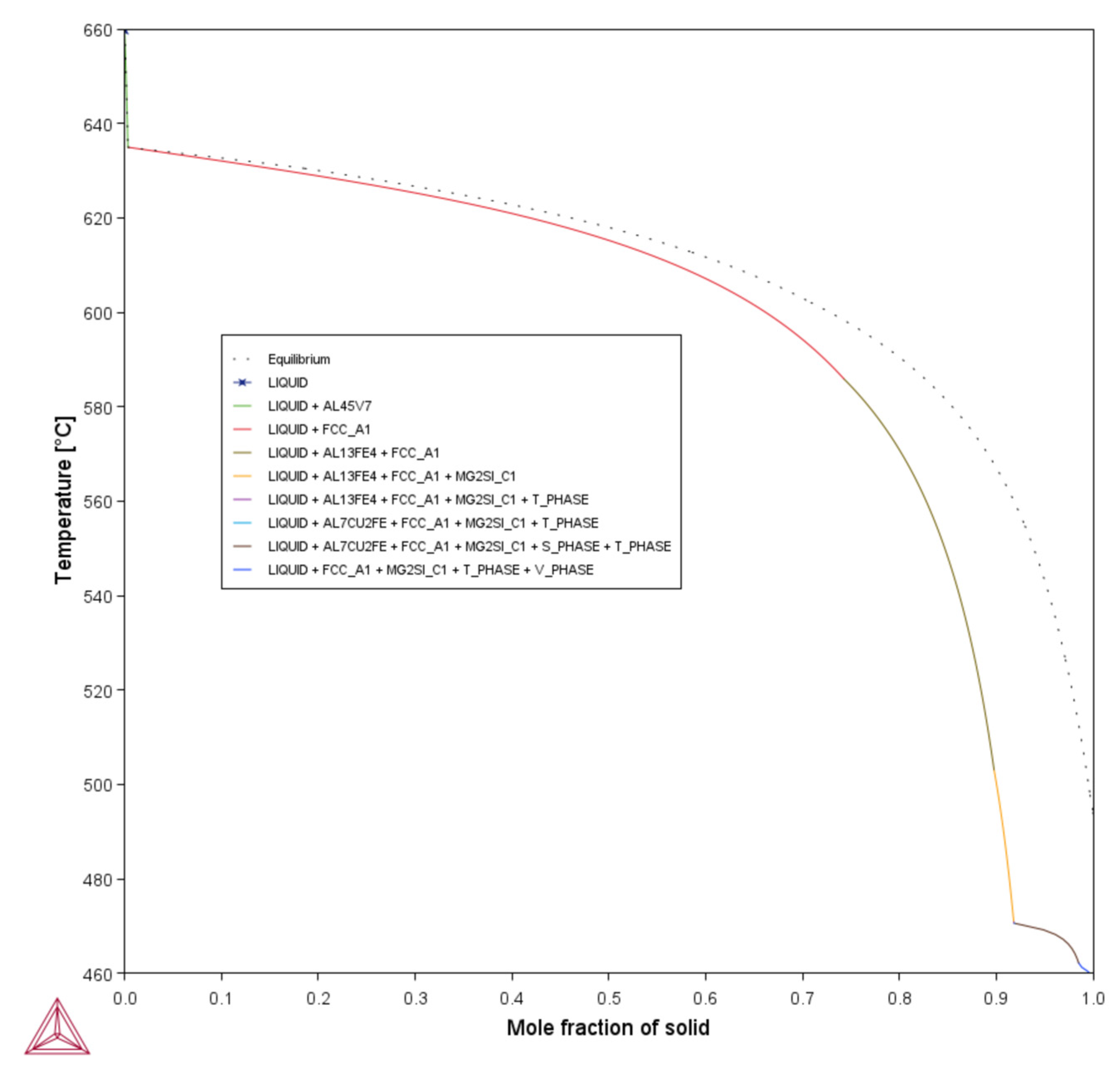

3.1. CALPHAD-Based Alloy Design Analysis for LPBF Using Solidification Indices

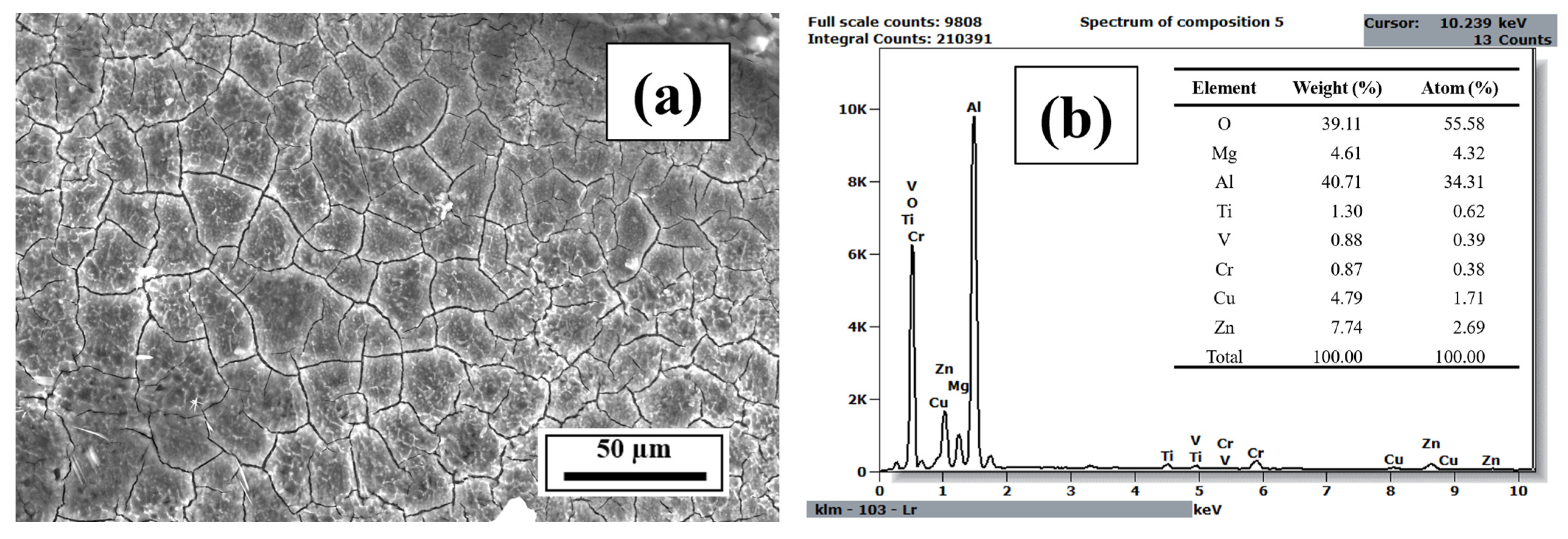

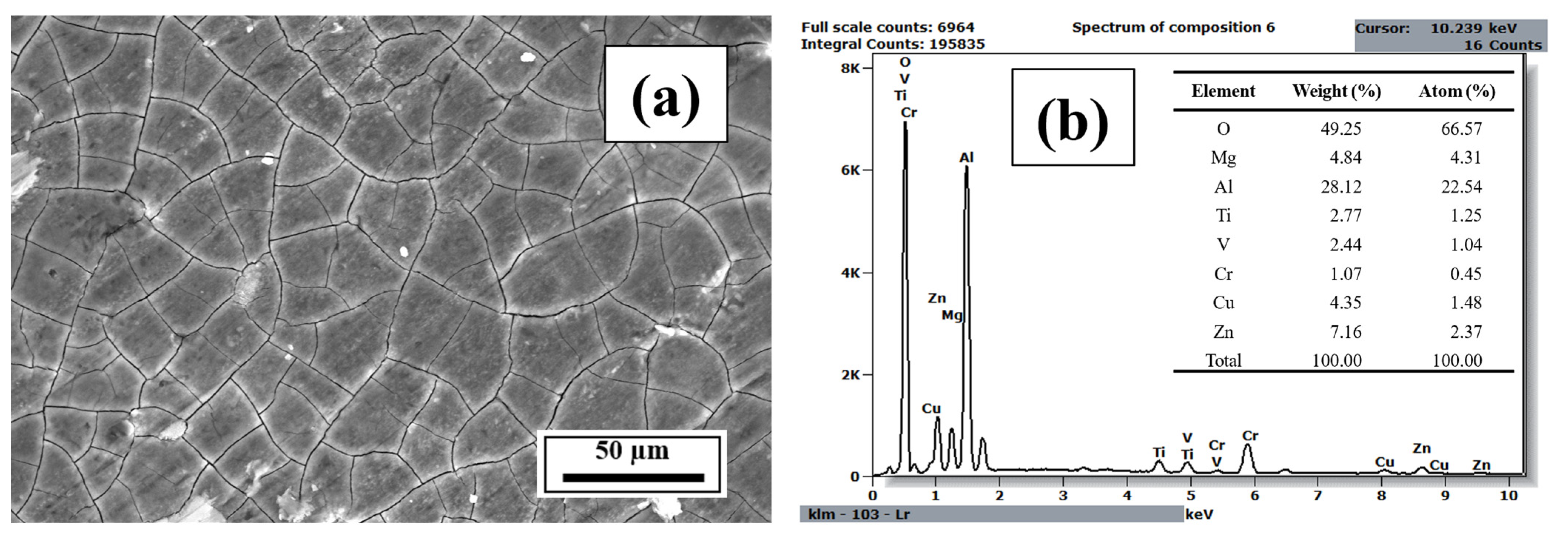

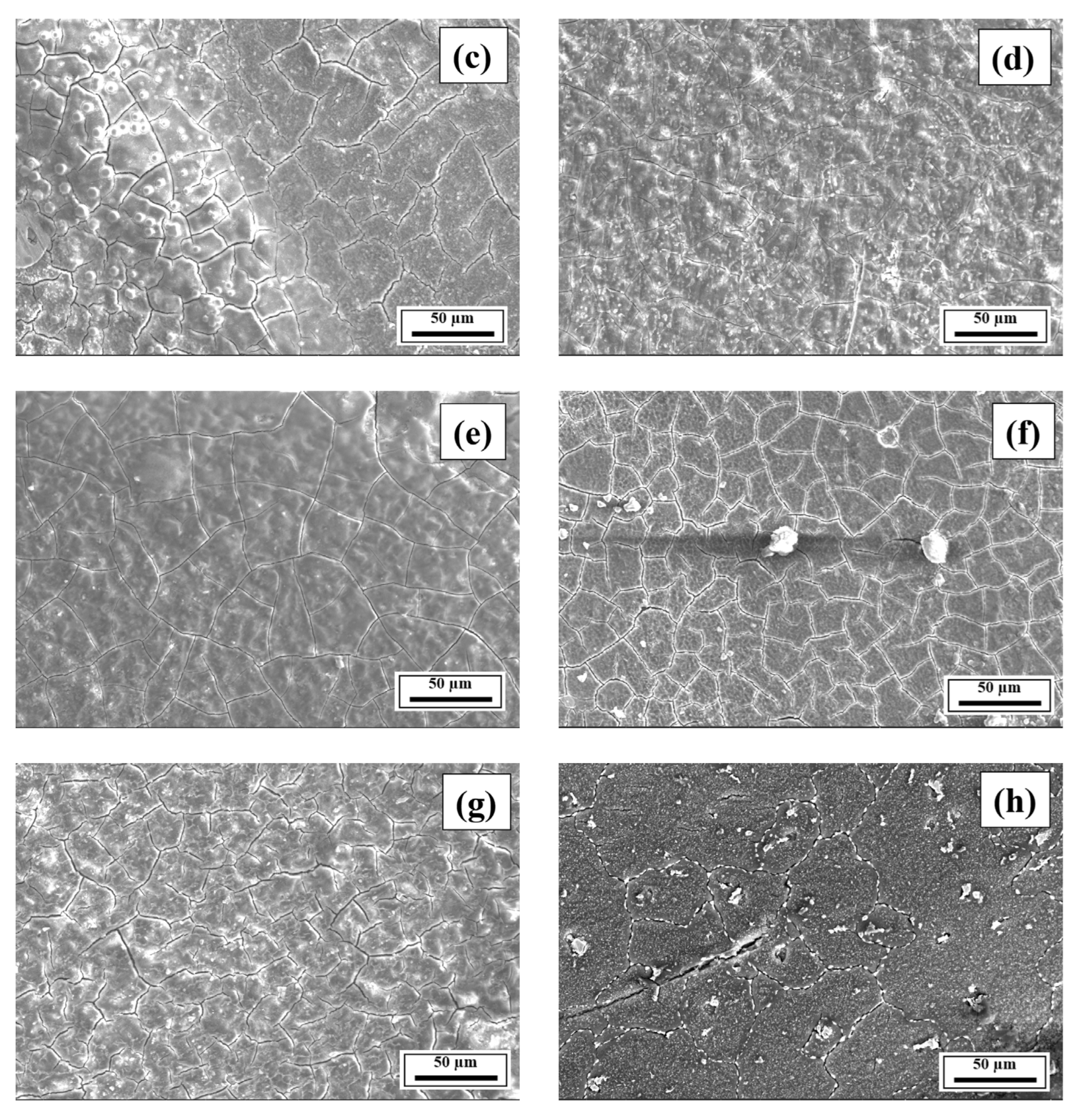

3.2. SEM Analysis

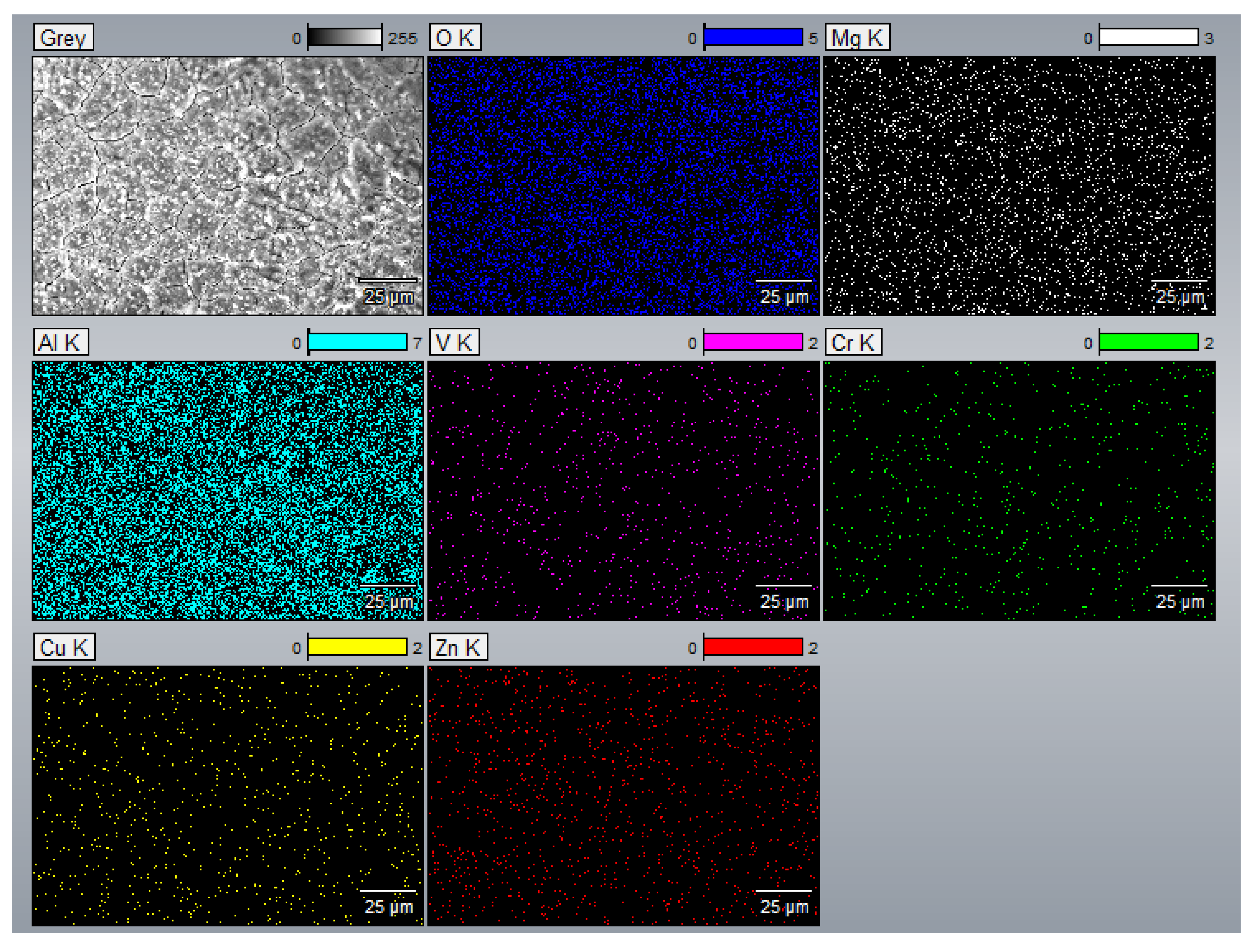

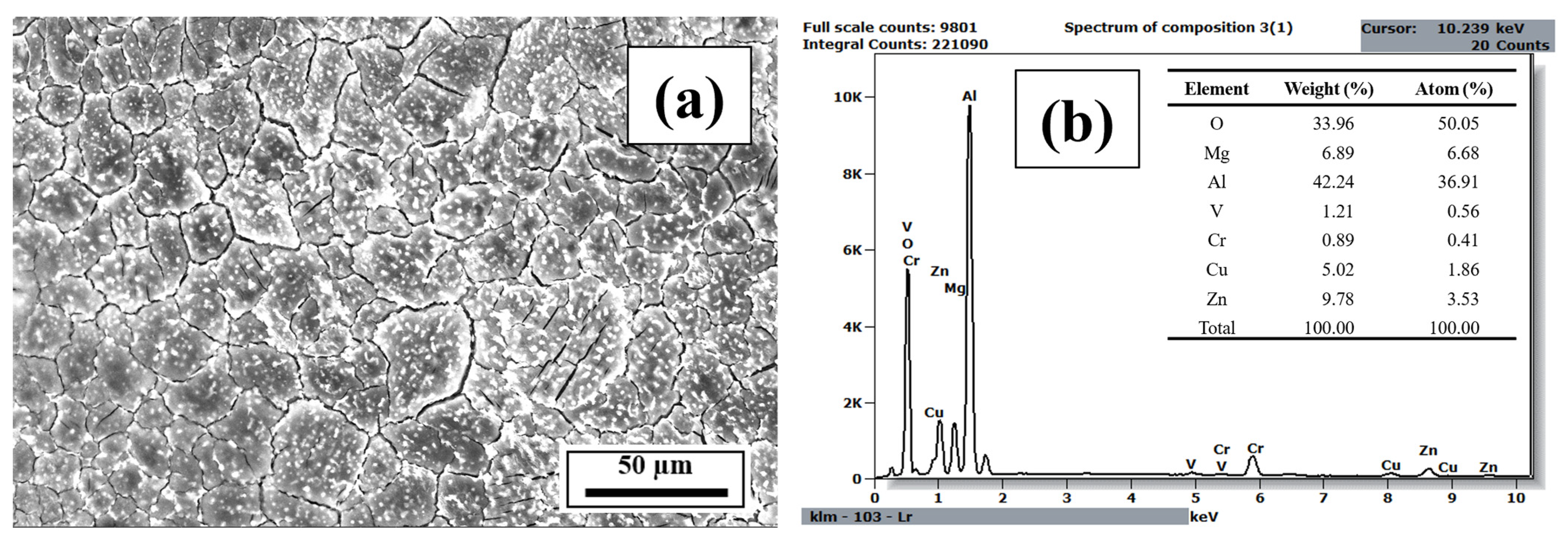

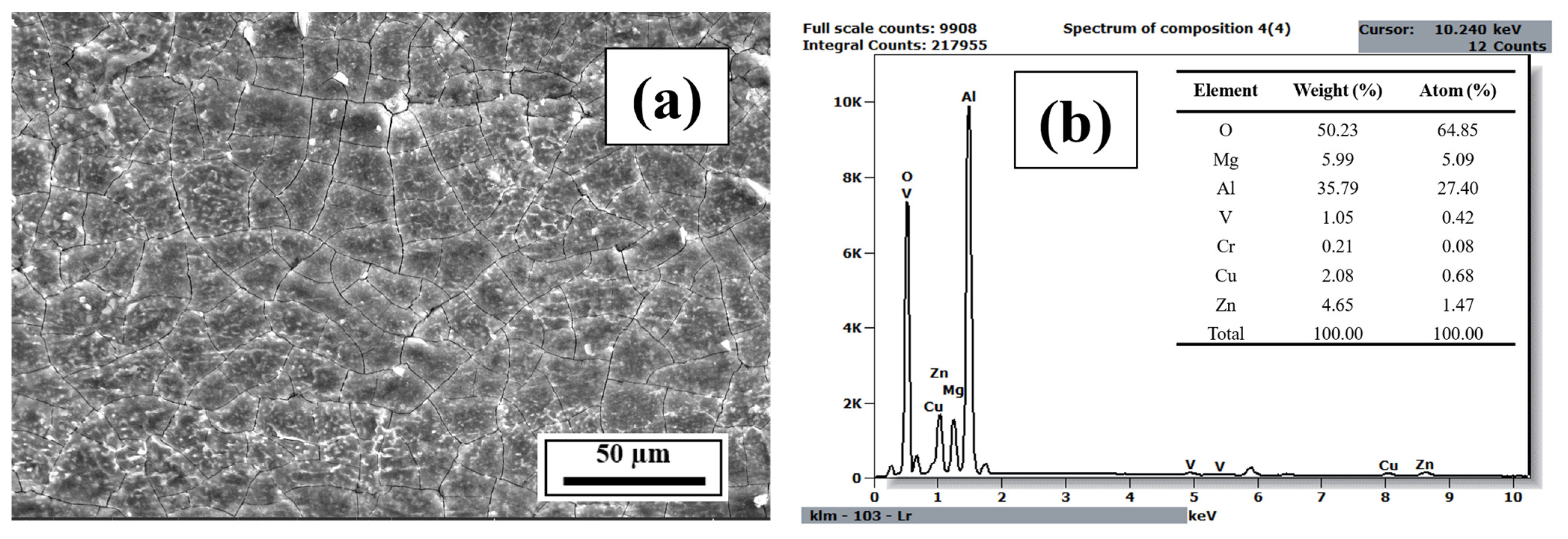

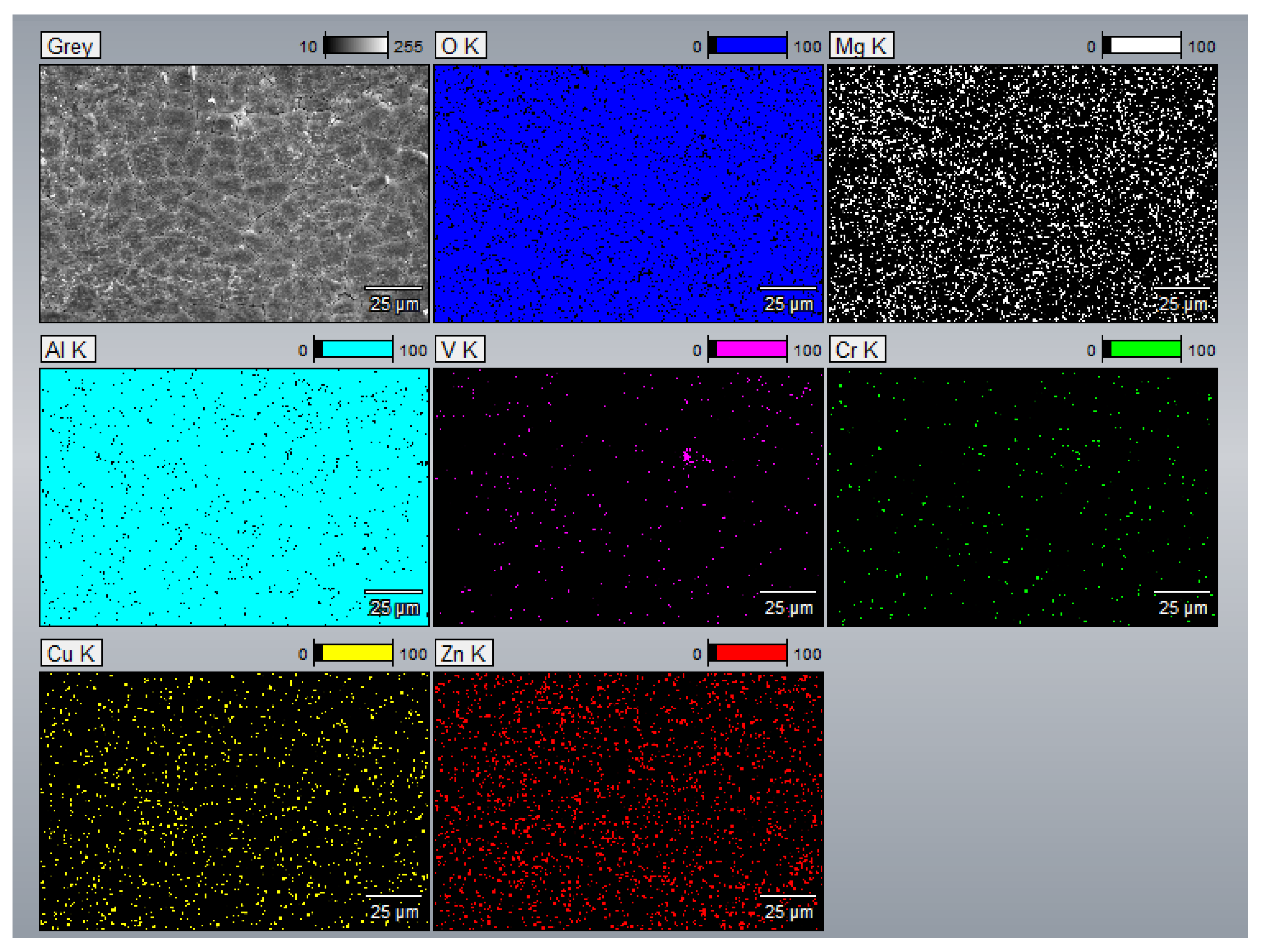

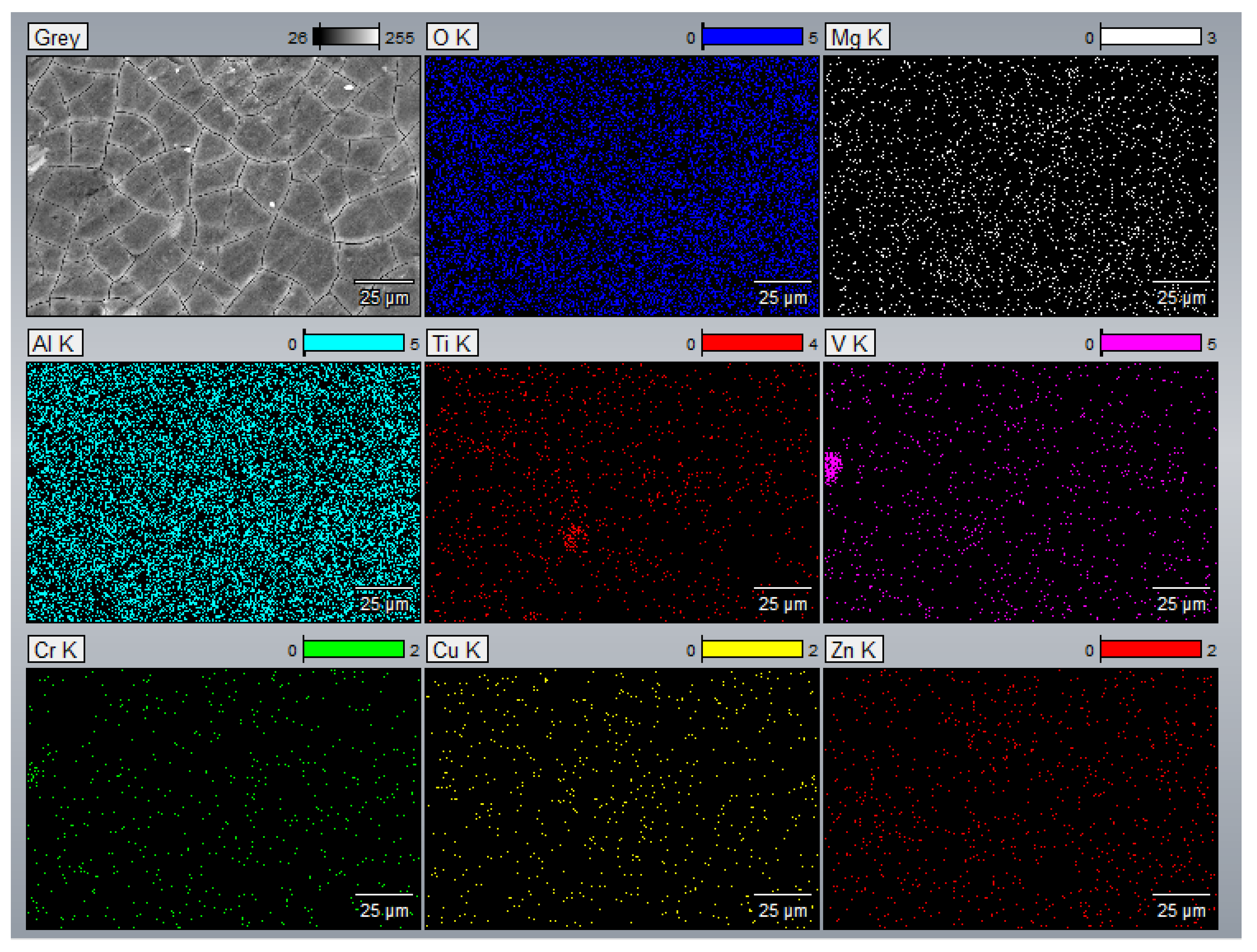

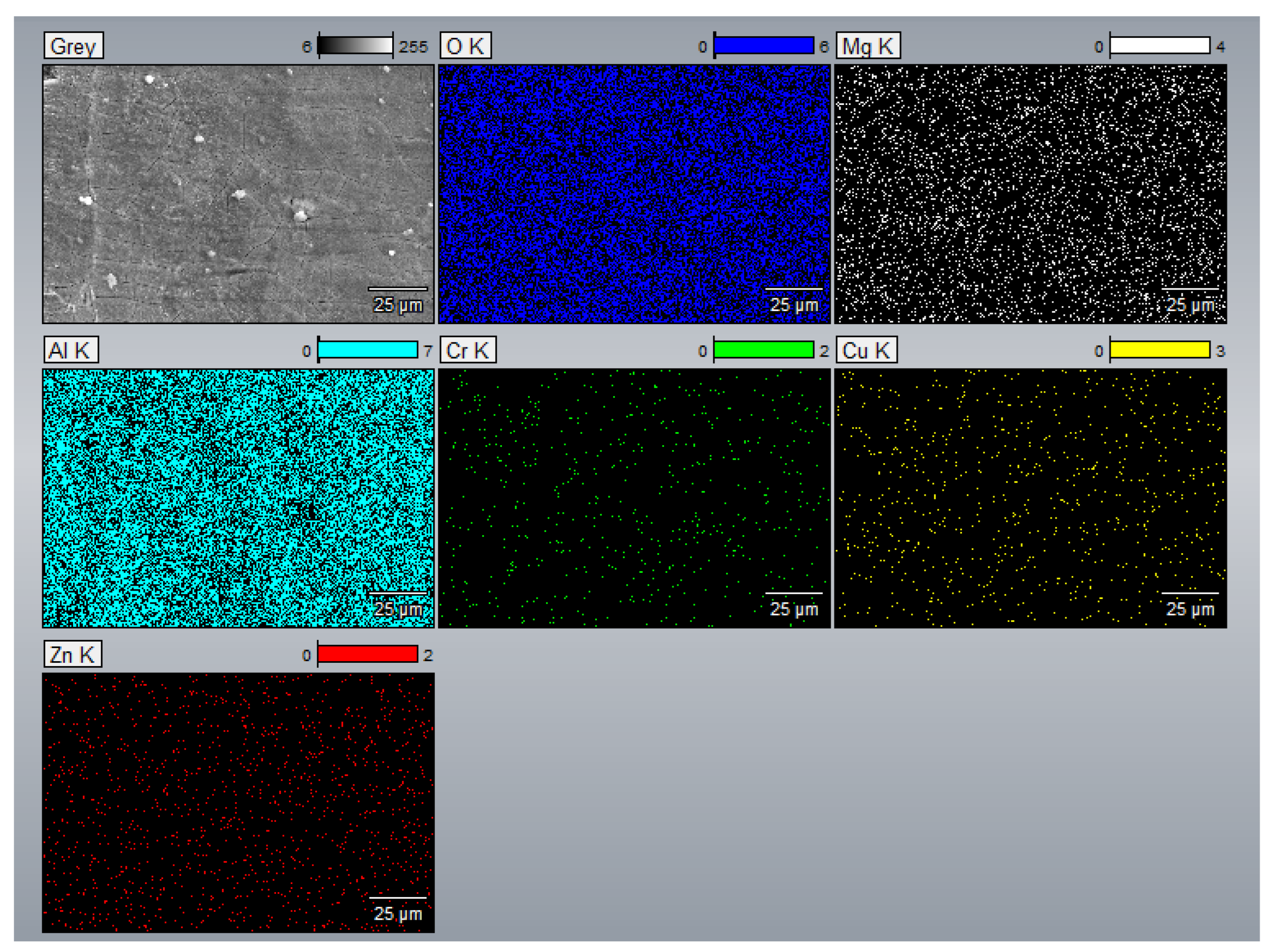

3.3. EDS Analysis

3.4. X-Ray Micro-CT Analysis

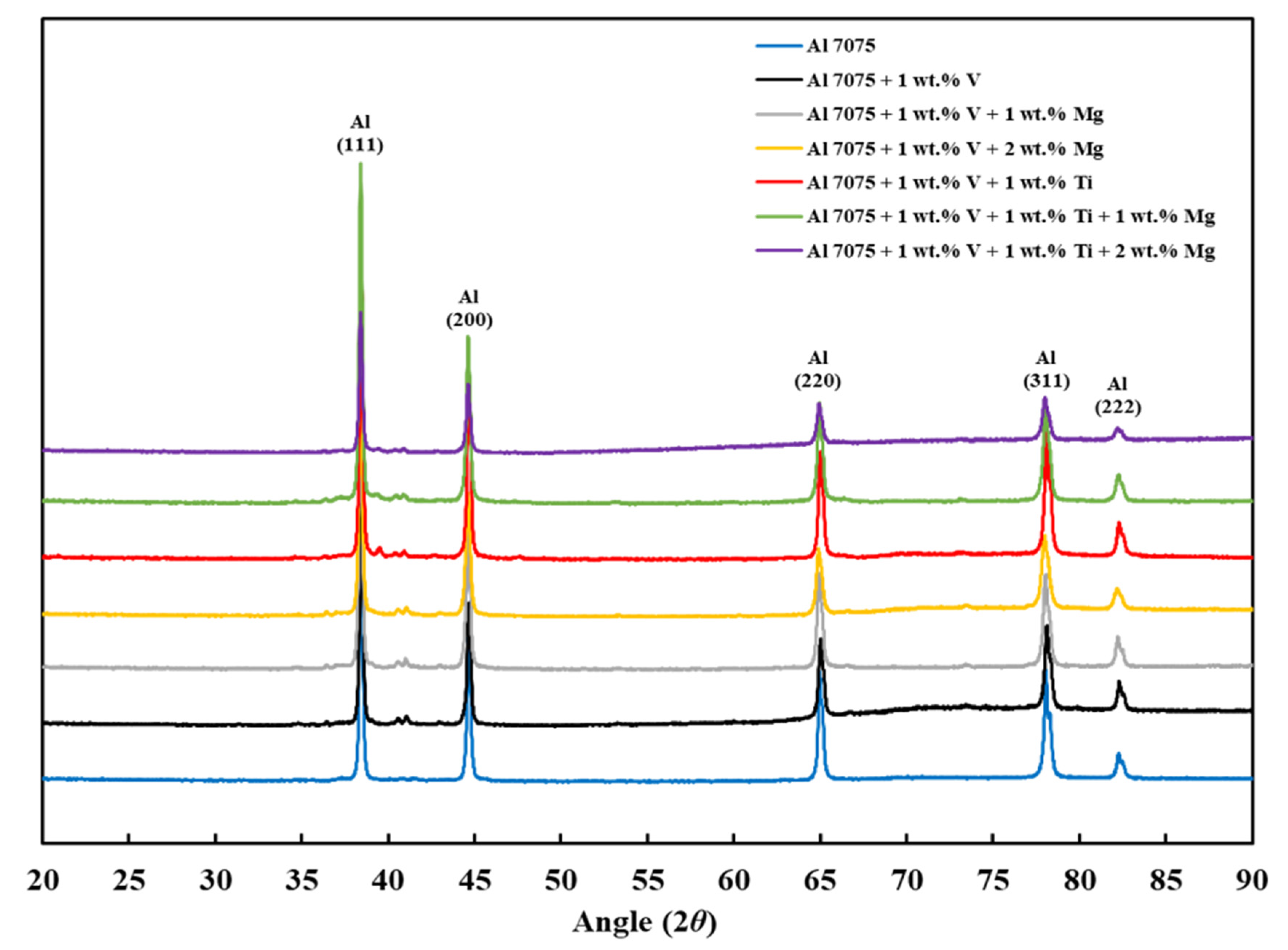

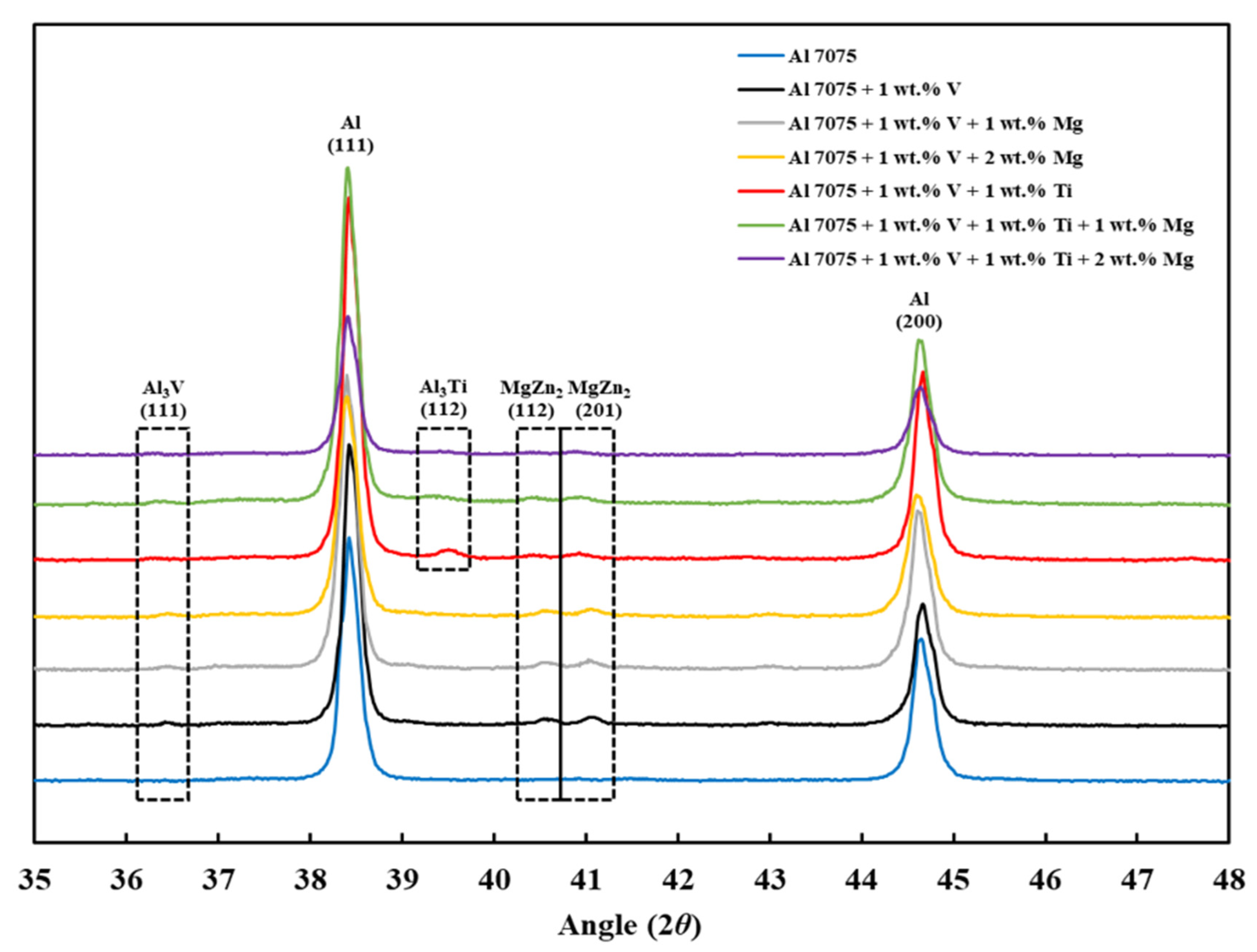

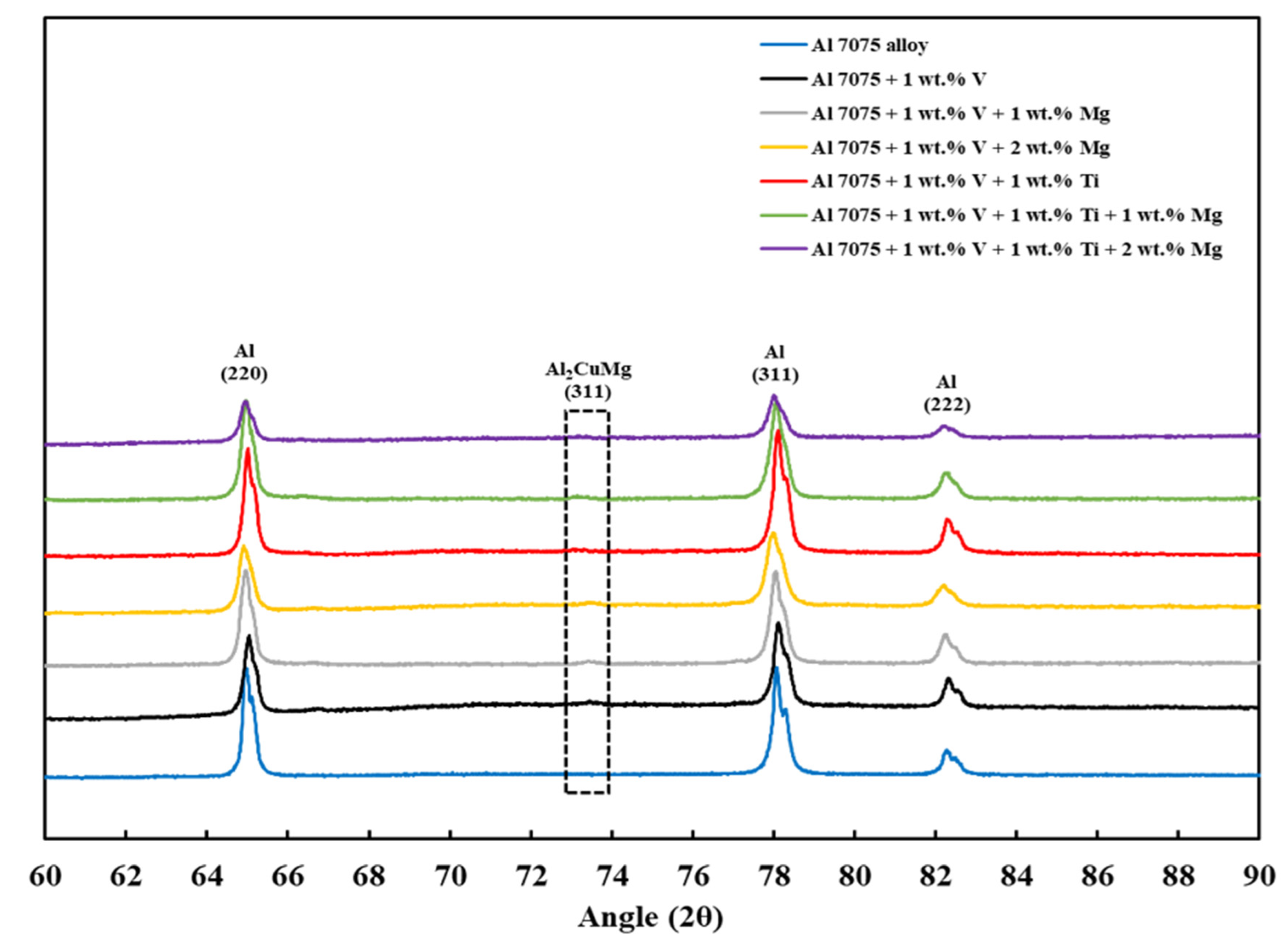

3.5. XRD Analysis

4. Conclusions

- By adding grain refiners (V and Ti) and an ES enhancer (Mg) to Al 7075 alloy, the compositions of interest were developed using CALPHAD and categorized into three as follows: Category 1 (Composition 1 = Al 7075), Category 2 (Composition 2 = Al 7075 + 1 wt.% V and Composition 5 = Al 7075 + 1 wt.% V + 1 wt.% Ti), and Category 3 (Composition 3 = Al 7075 + 1 wt.% V + 1 wt.% Mg, Composition 4 = Al 7075 + 1 wt.% V + 2 wt.% Mg, Composition 6 = Al 7075 + 1 wt.% V + 1 wt.% Ti + 1 wt.% Mg, and Composition 7 = Al 7075 + 1 wt.% V + 1 wt.% Ti + 2 wt.% Mg).

- Unlike for Composition 1, the T– curves of Compositions 2–7 from = 0 to = 0.1 revealed that the primary dispersoids (due to Vand/or Ti) solidified first from TLiquidus to the start of FCC-Al formation, with an increased freezing range. The HN of Al grains upon the dispersoids formed Al3V and/or Al3Ti phases, thereby refining the grains. The combined effect of 1 wt.% V and 1 wt.% Ti exceeded that of 1 wt.% V.

- Composition 1 exhibited the highest HSI and TCR values of 279.29 °C and 9.47 °C, respectively, at the final solidification stage. Category 2 improved in HSI (~5.8% and 9.1% decrements for Compositions 2 and 5, respectively) and TCR (~0.74% and 71.37% decrements for Compositions 2 and 5, respectively) compared to Category 1. As the Mg content increased in Category 3, only the T phase (Al2Mg3Zn3) eutectic solidified up to = 1 after the solidification of the Al¬–Mg2Si eutectic, which favored cracking resistance. Consequently, Category 3 exhibited relatively low HSI (~86.2%, 94.6%, 92.7%, and 94.7% decrements for Compositions 3, 4, 6, and 7, respectively) and TCR (~94.5%, 95.8%, 94.8%, and 96% decrements for Compositions 3, 4, 6, and 7, respectively) values compared to Category 1. Thus, the increase in Mg content favored the solidification of the desired T phase (Al2Mg3Zn3) eutectic as early as possible up to the end of solidification.

- Composition 1 exhibited the highest CSC value of 0.419. Category 2 improved in CSC (~15.8% and 24.8% decrements for Compositions 2 and 5, respectively) compared to Category 1. As the Mg content increased in Category 3, further improvements in CSC were observed (~58.9%, 60.1%, 62.1%, and 62.8% decrements for Compositions 3, 4, 6, and 7, respectively) compared to Category 1. Thus, the addition of Mg significantly reduced the time during which the sample is vulnerable to cracking.

- The SEM results revealed the crack reduction in the as-printed Compositions 2–7 compared to Composition 1 due to microstructural refinement and liquid availability during the final solidification stages. Also, while Ti and/or V caused microstructural refinement, an increase in the Mg content in Category 3 further suppressed the cracks due to the ES effect at the end of the solidification process, which corroborated the CALPHAD-based alloy design results using solidification indices. However, residual cracks and/or pores were observed in all the samples due to the lack of process parameter optimization.

- The SEM results of the etched cross-sections (y–z plane) of the LPBF-fabricated samples revealed that columnar grains and an avalanche of interconnected dark-colored pores that formed long cracks were present in Composition 1. For Compositions 2–7, microstructural refinements in the form of CET were observed, with the grain boundaries clearly outlined, similar to that of conventionally fabricated Al 7075 alloy.

- The EDS results confirmed that the alloying elements were uniformly distributed in the as-printed samples and that aluminum oxide was present in all as-printed samples.

- The X-ray micro-CT results revealed that in terms of percentage porosity decrement of the as-printed samples compared to Composition 1, Compositions 2–7 exhibited ~7–28% improvement in porosity reduction. However, pores were still present in Compositions 2–7 due to the adopted 168-W laser power. These results will serve as a critical baseline for improved studies using high laser power suitable for Al alloys.

- Finally, the XRD results revealed that the Al3V phase was observed in Compositions 2–7, and the Al3Ti phase was observed in Compositions 5–7, confirming the results of the CALPHAD-based alloy design and SEM results.

- Future work will require optimizing the LPBF parameters with substrate preheating and modification to eliminate defects. In parallel, mechanical-property characterization and precipitation-hardening heat treatment optimization should be conducted to establish process–structure–property links.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| CALPHAD | Calculation of Phase Diagrams |

| CET | Columnar-to-equiaxed transition |

| CSC | Cracking susceptibility coefficient |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| ES | Eutectic solidification |

| FCC | Face-centered cubic |

| HCS | Hot cracking susceptibility |

| HN | Heterogenous nucleation |

| HSI | Hot susceptibility index |

| LPBF | Laser powder bed fusion |

| Micro-CT | Micro-computed tomography |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SLM | Selective laser melting |

| VED | Volumetric energy density |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. CALPHAD-Based Alloy Design Results

| Composition | TSolidus (°C) | TLiquidus (°C) | Freezing Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 494.06 | 659.58 | 165.52 |

| 2 | 483.73 | 837.54 | 353.82 |

| 3 | 478.09 | 843.73 | 365.63 |

| 4 | 473.03 | 849.95 | 376.91 |

| 5 | 483.21 | 952.87 | 469.68 |

| 6 | 477.74 | 959.56 | 481.82 |

| 7 | 472.85 | 966.27 | 493.43 |

| Composition | Al–¬Mg2Si Eutectic | T Phase (Al2Mg3Zn3) eutectic | Al7Cu2Fe | S Phase (Al2CuMg) | V Phase ((Al, Zn)5(Zn, Cu)6(Mg)2)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T = 503.07 °C fS = 0.8977 | T = 471.08 °C fS = 0.9180 | T = 470.59 °C fS = 0.9184 | T = 470.57 °C fS = 0.9192 | T = 462.21 °C fS = 0.9850 |

| 2 | T = 503.65 °C fS = 0.8955 | T = 470.86 °C fS = 0.9166 | T = 470.54 °C fS = 0.9196 | T = 470.51 °C fS = 0.9204 | T = 462.03 °C fS = 0.9850 |

| 3 | T = 503.61 °C fS = 0.8674 | T = 473.32 °C fS = 0.8924 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | T = 502.51 °C fS = 0.8387 | T = 474.28 °C fS = 0.8674 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 5 | T = 502.16 °C fS = 0.8951 | T = 471.12 °C fS = 0.9152 | T = 470.71 °C fS = 0.9158 | T = 469.94 °C fS = 0.9327 | T = 461.91 °C fS = 0.9851 |

| 6 | T = 502.59 °C fS = 0.8664 | T = 473.56 °C fS = 0.8906 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | T = 501.55 °C fS = 0.8373 | T = 474.52 °C fS = 0.8651 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Appendix A.2. SEM Results

Appendix A.3. EDS Results

References

- Laleh, M.; Sadeghi, E.; Revilla, R.I.; Chao, Q.; Haghdadi, N.; Hughes, A.E.; Xu, W.; De Graeve, I.; Qian, M.; Gibson, I.; et al. Heat Treatment for Metal Additive Manufacturing. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 133, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Components—Process, Structure and Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Hui, D. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): A Review of Materials, Methods, Applications and Challenges. Compos. B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sames, W.J.; List, F.A.; Pannala, S.; Dehoff, R.R.; Babu, S.S. The Metallurgy and Processing Science of Metal Additive Manufacturing. Int. Mater. Rev. 2016, 61, 315–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhou, S.; Xu, W.; Leary, M.; Choong, P.; Qian, M.; Brandt, M.; Xie, Y.M. Topological Design and Additive Manufacturing of Porous Metals for Bone Scaffolds and Orthopaedic Implants: A Review. Biomaterials 2016, 83, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Components by Selective Electron Beam Melting—A Review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2016, 61, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettesheimer, T.; Hirzel, S.; Roß, H.B. Energy Savings through Additive Manufacturing: An Analysis of Selective Laser Sintering for Automotive and Aircraft Components. Energy Effic. 2018, 11, 1227–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.K.; Moroni, G.; Vaneker, T.; Fadel, G.; Campbell, R.I.; Gibson, I.; Bernard, A.; Schulz, J.; Graf, P.; Ahuja, B.; et al. Design for Additive Manufacturing: Trends, Opportunities, Considerations, and Constraints. CIRP Ann. 2016, 65, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Voisin, T.; McKeown, J.T.; Ye, J.; Calta, N.P.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Roehling, T.T.; et al. Additively Manufactured Hierarchical Stainless Steels with High Strength and Ductility. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.B.; Owens, P.R. Geochemical Characterization of the Loess-Paleosol Sequence in Northeast China. Geoderma 2018, 321, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Brandt, M.; Sun, S.; Elambasseril, J.; Liu, Q.; Latham, K.; Xia, K.; Qian, M. Additive Manufacturing of Strong and Ductile Ti–6Al–4V by Selective Laser Melting via in Situ Martensite Decomposition. Acta Mater. 2015, 85, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, J.J.; Seifi, M. Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Mechanical Properties. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2016, 46, 151–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Q.; Cruz, V.; Thomas, S.; Birbilis, N.; Collins, P.; Taylor, A.; Hodgson, P.D.; Fabijanic, D. On the Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of a Selective Laser Melted Austenitic Stainless Steel. Scr. Mater. 2017, 141, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laleh, M.; Hughes, A.E.; Xu, W.; Haghdadi, N.; Wang, K.; Cizek, P.; Gibson, I.; Tan, M.Y. On the Unusual Intergranular Corrosion Resistance of 316L Stainless Steel Additively Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Corros. Sci. 2019, 161, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruth, J.P.; Mercelis, P.; Van Vaerenbergh, J.; Froyen, L.; Rombouts, M. Binding Mechanisms in Selective Laser Sintering and Selective Laser Melting. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2005, 11, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olakanmi, E.O.; Cochrane, R.F.; Dalgarno, K.W. A Review on Selective Laser Sintering/Melting (SLS/SLM) of Aluminium Alloy Powders: Processing, Microstructure, and Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 74, 401–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, M.; Uematsu, Y.; Kakiuchi, T.; Nakajima, M.; Kawaguchi, R. Defect-Dominated Fatigue Behavior in Type 630 Stainless Steel Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 666, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, S.J.; Wang, H.L.; Hou, W.T.; Hao, Y.L.; Yang, R.; Sercombe, T.B.; Zhang, L.C. Microstructure, Defects and Mechanical Behavior of Beta-Type Titanium Porous Structures Manufactured by Electron Beam Melting and Selective Laser Melting. Acta Mater. 2016, 113, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, H.; Palm, F.; Kühn, U.; Eckert, J. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the Near-Beta Titanium Alloy Ti-5553 Processed by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Des. 2016, 105, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averyanova, M.; Bertrand, P.; Verquin, B. Manufacture of Co-Cr Dental Crowns and Bridges by Selective Laser Melting Technology. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2011, 6, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, N.J.; Todd, I.; Mumtaz, K. Reduction of Micro-Cracking in Nickel Superalloys Processed by Selective Laser Melting: A Fundamental Alloy Design Approach. Acta Mater. 2015, 94, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Song, B.; Wei, Q.; Bourell, D.; Shi, Y. A Review of Selective Laser Melting of Aluminum Alloys: Processing, Microstructure, Property and Developing Trends. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; Dong, H.; Chen, S.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Pulse MIG Welded 6061/A356 Aluminum Alloy Dissimilar Butt Joints. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, K.; Yin, S.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Lupoi, R. Solid-State Additive Manufacturing and Repairing by Cold Spraying: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Zhou, Y.; Smugeresky, J.E.; Schoenung, J.M.; Lavernia, E.J. Thermal Behavior and Microstructural Evolution during Laser Deposition with Laser-Engineered Net Shaping: Part I. Numerical Calculations. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2008, 39, 2228–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Balla, V.K.; Basu, D.; Bose, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Laser Processing of SiC-Particle-Reinforced Coating on Titanium. Scr. Mater. 2010, 63, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanescu, D.M.; Ruxanda, R. Fundamentals of Solidification. In Metallography and Microstructures; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2004; Volume 9, pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavernia, E.J.; Ayers, J.D.; Srivatsan, T.S. Rapid Solidification Processing with Specific Application to Aluminium Alloys. Int. Mater. Rev. 1992, 37, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, A.; Marchese, G.; Saboori, A.; Bassini, E.; Manfredi, D.; Biamino, S.; Ugues, D.; Fino, P.; Lombardi, M. New Aluminum Alloys Specifically Designed for Laser Powder Bed Fusion: A Review. Materials 2019, 12, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulkhair, N.T.; Simonelli, M.; Parry, L.; Ashcroft, I.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. 3D Printing of Aluminium Alloys: Additive Manufacturing of Aluminium Alloys Using Selective Laser Melting. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 106, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M. The Rise of 3-D Printing: The Advantages of Additive Manufacturing over Traditional Manufacturing. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, T.M.; Clarke, A.J.; Babu, S.S. Design and Tailoring of Alloys for Additive Manufacturing. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2020, 51, 6000–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Fan, Z.; Tang, X.; Yin, Y.; Li, G.; Huang, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, T.; et al. A Novel Strategy to Additively Manufacture 7075 Aluminium Alloy with Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 821, 141638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopyra, W.; Gruber, K.; Smolina, I.; Kurzynowski, T.; Kuźnicka, B. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of AA7075 Alloy: Influence of Process Parameters on Porosity and Hot Cracking. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.S.; Thapliyal, S. Design Approaches for Printability-Performance Synergy in Al Alloys for Laser-Powder Bed Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2021, 204, 109640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H.; Yahata, B.D.; Hundley, J.M.; Mayer, J.A.; Schaedler, T.A.; Pollock, T.M. 3D Printing of High-Strength Aluminium Alloys. Nature 2017, 549, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Cao, P.; Yuan, T.; Zhu, H. Developing a High-Strength Al-Mg-Si-Sc-Zr Alloy for Selective Laser Melting: Crack-Inhibiting and Multiple Strengthening Mechanisms. Acta Mater. 2020, 193, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Q.; Fan, Z.; Li, G.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.-X.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, J.; et al. Inoculation Treatment of an Additively Manufactured 2024 Aluminium Alloy with Titanium Nanoparticles. AcMat 2020, 196, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.P.; Maeder, X.; Michler, J.; Spierings, A.B. Mechanical Anisotropy Investigated in the Complex SLM-Processed Sc- and Zr-Modified Al–Mg Alloy Microstructure. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1801113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, S.; Okuhira, T.; Mitsuhara, M.; Nakashima, H.; Kusui, J.; Adachi, M. Effect of Fe Addition on Heat-Resistant Aluminum Alloys Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Metals 2019, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H.; Yahata, B.; Mayer, J.; Mone, R.; Stonkevitch, E.; Miller, J.; O’Masta, M.R.; Schaedler, T.; Hundley, J.; Callahan, P.; et al. Grain Refinement Mechanisms in Additively Manufactured Nano-Functionalized Aluminum. AcMat 2020, 200, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opprecht, M.; Garandet, J.-P.; Roux, G.; Flament, C.; Soulier, M.; Opprecht, M.; Garandet, J.-P.; Roux, G.; Flament, C.; Soulier, M. A Solution to the Hot Cracking Problem for Aluminium Alloys Manufactured by Laser Beam Melting. AcMat 2020, 197, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, D.; Li, G.; Cai, Q. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, Aging Behavior, and Corrosion Resistance of a Laser Powder Bed Fusion Fabricated Al–Zn–Mg–Cu–Ta Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 832, 142364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ng, F.L.; Seet, H.L.; Lu, W.; Liebscher, C.H.; Rao, Z.; Raabe, D.; Mui Ling Nai, S. Superior Mechanical Properties of a Selective-Laser-Melted AlZnMgCuScZr Alloy Enabled by a Tunable Hierarchical Microstructure and Dual-Nanoprecipitation. Mater. Today 2022, 52, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, H.; Nie, X.; Yin, J.; Hu, Z.; Zeng, X. Effect of Zirconium Addition on Crack, Microstructure and Mechanical Behavior of Selective Laser Melted Al-Cu-Mg Alloy. Scr. Mater. 2017, 134, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.; Ke, L.; Zeng, X. Effect of Zr Content on Formability, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Selective Laser Melted Zr Modified Al-4.24Cu-1.97Mg-0.56Mn Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 764, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ruan, G.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Guo, C.; Zhao, C.; Cheng, L.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; et al. Facile and Cost-Effective Approach to Additively Manufacture Crack-Free 7075 Aluminum Alloy by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 928, 167097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D. Process Optimization and Mechanical Property Evolution of AlSiMg0.75 by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Des. 2018, 140, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.P.; Wang, X.J.; Saunders, M.; Suvorova, A.; Zhang, L.C.; Liu, Y.J.; Fang, M.H.; Huang, Z.H.; Sercombe, T.B. A Selective Laser Melting and Solution Heat Treatment Refined Al–12Si Alloy with a Controllable Ultrafine Eutectic Microstructure and 25% Tensile Ductility. Acta Mater. 2015, 95, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Q.; Yan, C.; Shi, Y. Effect of Heat Treatment on AlSi10Mg Alloy Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting: Microstructure Evolution, Mechanical Properties and Fracture Mechanism. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 663, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huynh, T.; Park, S.; Hyer, H.; Mehta, A.; Song, S.; Bai, Y. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Al–10 Wt% Ce Alloys: Microstructure and Tensile Property. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 14611–14626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkowski, A.; Sisco, K.; Bahl, S.; Shyam, A.; Yang, Y.; Allard, L.; Nandwana, P.; Rossy, A.M.; Dehoff, R.R. Microstructure and Properties of a High Temperature Al–Ce–Mn Alloy Produced by Additive Manufacturing. Acta Mater. 2020, 196, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinwei, L.; Shi, S.; Shuang, H.; Xiaogang, H.; Qiang, Z.; Hongxing, L.; Wenwu, L.; Yusheng, S.; Hui, D. Microstructure, Solidification Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Al-Si-Mg-Ti/TiC Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, M.X.; Zhu, Q. Novel Approach to Additively Manufacture High-Strength Al Alloys by Laser Powder Bed Fusion through Addition of Hybrid Grain Refiners. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, H.; Enz, J.; Ebel, T.; Yan, M. Selective Laser Melting Additive Manufacturing of 7xxx Series Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloy: Cracking Elimination by Co-Incorporation of Si and TiB2. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, Y.; Sasaki, S. Effects of the Addition of Silicon to 7075 Aluminum Alloy on Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Selective Laser Melting Processability. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 777, 139079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, Y.; Kusaki, Y.; Itagaki, K.; Sasaki, S. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of A7075 Alloy with Additional Si Objects Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Trans. 2019, 60, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, R.; Yuan, T.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X. Microstructures and Tensile Properties of a Selective Laser Melted Al–Zn–Mg–Cu (Al7075) Alloy by Si and Zr Microalloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 787, 139492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.J. Model for Solute Redistribution during Rapid Solidification. J. Appl. Phys. 1982, 53, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroy, T.; David, S.A. Physical Processes in Fusion Welding. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1995, 67, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Whang, S.H. Grain Refinement in Rapidly Solidified W-Si Alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 1991, 26, 5911–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapliyal, S.; Komarasamy, M.; Shukla, S.; Zhou, L.; Hyer, H.; Park, S.; Sohn, Y.; Mishra, R.S. An Integrated Computational Materials Engineering-Anchored Closed-Loop Method for Design of Aluminum Alloys for Additive Manufacturing. Materialia 2020, 9, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S. A Simple Index for Predicting the Susceptibility to Solidification Cracking. Weld. J. 2015, 94, 374–388. [Google Scholar]

- Thapliyal, S.; Nene, S.S.; Agrawal, P.; Wang, T.; Morphew, C.; Mishra, R.S.; McWilliams, B.A.; Cho, K.C. Damage-Tolerant, Corrosion-Resistant High Entropy Alloy with High Strength and Ductility by Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S. A Criterion for Cracking during Solidification. Acta Mater. 2015, 88, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, D.G.; Suyitno; Katgerman, L. Mechanical Properties in the Semi-Solid State and Hot Tearing of Aluminium Alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2004, 49, 629–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovgyy, B.; Simonelli, M.; Pham, M.S. Alloy Design against the Solidification Cracking in Fusion Additive Manufacturing: An Application to a FeCrAl Alloy. Mater. Res. Lett. 2021, 9, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippold, J.C. Welding Metallurgy and Weldability; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–400. ISBN 9781118230701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saida, K.; Matsushita, H.; Nishimoto, K.; Kiuchi, K.; Nakayama, J. Quantitative Influence of Minor and Impurity Elements on Hot Cracking Susceptibility of Extra High-Purity Type 310 Stainless Steel. Yosetsu Gakkai Ronbunshu Q. J. Jpn. Weld. Soc. 2013, 31, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agarwal, G.; Kumar, A.; Gao, H.; Amirthalingam, M.; Moon, S.C.; Dippenaar, R.J.; Richardson, I.M.; Hermans, M.J.M. Study of Solidification Cracking in a Transformation-Induced Plasticity-Aided Steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2018, 49, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, K.; Neshani, S.; Uba, C.; Ding, H.; Raush, J.; Guo, S. Engineering the Surface Melt for In-Space Manufacturing of Aluminum Parts. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 6092–6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvvssn, V.; Butt, M.M.; Laieghi, H.; Uddin, Z.; Salamci, E.; Kim, D.B.; Kizil, H. Recent Progress in Additive Manufacturing of 7XXX Aluminum Alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 4353–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H. Laser Surface Treatment and Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Study Using Custom Designed 3D Printer and the Application of Machine Learning in Materials Science. Ph.D. Dissertations, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zeng, C.; Hemmasian Ettefagh, A.; Gao, J.; Guo, S. Laser Surface Treatment of Ti-10Mo Alloy under Ar and N2 Environment for Biomedical Application. J. Laser Appl. 2019, 31, 022012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero Sistiaga, M.L.; Mertens, R.; Vrancken, B.; Wang, X.; Van Hooreweder, B.; Kruth, J.P.; Van Humbeeck, J. Changing the Alloy Composition of Al7075 for Better Processability by Selective Laser Melting. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2016, 238, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Yu, W.; Chua, C.K.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.; Xue, P.; Tan, S.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, H. Influence of Erbium Addition on the Defects of Selective Laser-Melted 7075 Aluminium Alloy. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2022, 17, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Xue, P.; Tan, S.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, H. Processing and Characterization of Crack-Free 7075 Aluminum Alloys with Elemental Zr Modification by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Mater. Sci. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, A.; Marchese, G.; Manfredi, D.; Lorusso, M.; Calignano, F.; Biamino, S.; Lombardi, M.; Fino, P.; Pavese, M. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of a High Strength Al-Si-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloy. Metals 2018, 8, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.; Kim, K.T.; Yu, J.H.; Park, J.M.; Yang, D.Y.; Jung, S.H.; Jo, S.; Joo, H.; Kang, M.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. A Novel Route for Predicting the Cracking of Inoculant-Added AA7075 Processed via Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 62, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chen, X.; Liu, T.; Wei, H.; Zhu, Z.; Du, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liao, W. Crack-Free High-Strength AA-7075 Fabricated by Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Inoculations of Metallic Glass Powders. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 891, 145916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, X.; Guo, C.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, Q.; Qu, W.; Li, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, M.X.; Zhu, Q. Investigation into the Effect of Energy Density on Densification, Surface Roughness and Loss of Alloying Elements of 7075 Aluminium Alloy Processed by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 147, 107621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | Al 7075 Alloy (wt.%) | V (wt.%) | Mg (wt.%) | Ti (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% | - | - | - |

| 2 | Balance | 1 | - | - |

| 3 | Balance | 1 | 1 | - |

| 4 | Balance | 1 | 2 | - |

| 5 | Balance | 1 | - | 1 |

| 6 | Balance | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | Balance | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Elements | Al | Ti | Zn | Cr | Mg | Mn | Cu | Fe | Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition (wt.%) | Balance | 0.01 | 5.35 | 0.19 | 2.62 | 0.01 | 1.61 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Composition | CSC | TLiquidus (°C) | T (Start of FCC Al Formation; °C) | Initial Freezing Range (°C) | T = 0.95; °C) | T = 1; °C) | TCR (°C) | HSI (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.419 | 659.58 | = ~0.00333 | 24.61 | 469.11 | 459.64 | 9.47 | 279.29 |

| 2 | 0.353 | 837.54 | = ~0.0335 | 203.99 | 469.05 | 459.65 | 9.40 | 263.25 |

| 3 | 0.172 | 843.73 | = ~0.0335 | 215.74 | 472.57 | 472.05 | 0.52 | 38.55 |

| 4 | 0.167 | 849.95 | = ~0.0338 | 227.58 | 472.95 | 472.56 | 0.39 | 15.09 |

| 5 | 0.315 | 952.87 | = ~0.0515 | 317.41 | 469.01 | 466.30 | 2.71 | 253.80 |

| 6 | 0.159 | 959.56 | = ~0.0519 | 330.04 | 472.58 | 472.09 | 0.49 | 20.26 |

| 7 | 0.156 | 966.27 | = ~0.0528 | 342.76 | 472.90 | 472.52 | 0.38 | 14.92 |

| Composition | Mean Pore Size (10−5 mm3) | Volume of Sample (mm3) | Total Volume of Pores in the Sample (mm3) | Ratio of Pore Volume to Sample Volume | Porosity Decrement Compared to Composition 1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.48 | 60.94 ± 3.81 | 6.86 | 0.113 ± 0.0071 | - |

| 2 | 0.15 | 330.71 ± 4.17 | 27.18 | 0.0822 ± 0.0010 | 27.11 |

| 3 | 0.11 | 332.11 ± 3.29 | 26.98 | 0.0813 ± 0.0008 | 27.84 |

| 4 | 4.16 | 183.80 ± 3.11 | 13.53 | 0.0736 ± 0.0012 | 34.62 |

| 5 | 7.39 | 383.31 ± 5.34 | 38.03 | 0.0992 ± 0.0014 | 11.88 |

| 6 | 0.14 | 375.25 ± 5.19 | 39.66 | 0.1057 ± 0.0015 | 6.14 |

| 7 | 4.63 | 143.07 ± 4.28 | 14.85 | 0.1038 ± 0.0031 | 7.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uba, C.U.; Ding, H.; Chen, Y.; Guo, S.; Raush, J.R. Enhancing the Printability of Laser Powder Bed Fusion-Processed Aluminum 7xxx Series Alloys Using Grain Refinement and Eutectic Solidification Strategies. Materials 2025, 18, 5089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225089

Uba CU, Ding H, Chen Y, Guo S, Raush JR. Enhancing the Printability of Laser Powder Bed Fusion-Processed Aluminum 7xxx Series Alloys Using Grain Refinement and Eutectic Solidification Strategies. Materials. 2025; 18(22):5089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225089

Chicago/Turabian StyleUba, Chukwudalu Uchenna, Huan Ding, Yehong Chen, Shengmin Guo, and Jonathan Richard Raush. 2025. "Enhancing the Printability of Laser Powder Bed Fusion-Processed Aluminum 7xxx Series Alloys Using Grain Refinement and Eutectic Solidification Strategies" Materials 18, no. 22: 5089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225089

APA StyleUba, C. U., Ding, H., Chen, Y., Guo, S., & Raush, J. R. (2025). Enhancing the Printability of Laser Powder Bed Fusion-Processed Aluminum 7xxx Series Alloys Using Grain Refinement and Eutectic Solidification Strategies. Materials, 18(22), 5089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225089