1. Introduction

Low-dimensional materials exhibiting charge density wave (CDW) orders [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] have attracted significant attention due to their rich phase diagrams, including superconductivity (SC) [

1,

4], nematicity [

5], and multiple density-wave orders [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Suppression of CDW by external parameters in those low-dimensional materials often leads to emergent novel quantum states, making them an ideal platform for exploring the interplay between the CDW and the competing quantum states. Archetypal examples include the case of transition-metal dichalcogenides Pd

xTaSe

2, in which intercalating Pd ions between TaSe

2 layers suppresses the CDW and enhances SC near the CDW quantum critical point [

1], and that of the kagome metals AV

3Sb

5 (A = K, Rb, Cs), at which the pressure-induced suppression of the CDW state results in two SC domes [

8,

9]

CuTe represents a prototypical example of exhibiting CDW order from the quasi-one-dimensional (Q1D) electronic structure. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy has confirmed that the CDW transition appearing at

TCDW1 = 335 K at ambient pressure is driven by the Fermi surface nesting of Te 5

px orbitals [

10]. Under high-pressure conditions [

11,

12], CuTe exhibits a complex pressure–temperature phase diagram involving an interplay between CDW and SC phases (

Figure S1). As pressure increases,

TCDW1, as evidenced by a jump in resistivity

, decreases linearly and reaches ~100 K near 6.5 GPa. Above this pressure, the anomaly vanishes. Beyond ~6.7 GPa, another in-plane resistivity anomaly—a peak in the

dρ/

dT curve—appears at ~200 K, indicating a stabilization of a second CDW phase (CDW2). With further pressure (6.7 ≤

P ≤ 10 GPa),

TCDW2 is gradually lowered toward ~170 K, and the resistivity anomaly at

TCDW2 finally vanishes above 10 GPa. Moreover, the SC first emerges at a pressure of 4.8 GPa as a small resistivity drop at

TC ≈ 0.5 K [

12].

TC rises with further increase in pressure, showing a maximum at 2.3 K near 6.5 GPa. Above 6.5 GPa,

TC gradually decreases, consequently forming a dome-like phase diagram. Beyond 10 GPa,

TC becomes below 1 K, indicating significant suppression of SC with increasing pressure. At pressures exceeding 20 GPa, CuTe undergoes a structural phase transition from the orthorhombic (

Pmmn) to the monoclinic (

Cm) phase. In this new structural phase, SC is stabilized with

TC ≈ 2.4 K, persisting across the high-pressure range up to 49 GPa [

11].

However, the nature of pressure-induced SC in CuTe, particularly its relationship with the CDW orders, remains elusive. As a possible mechanism for finding SC in the vicinity of CDW phases, two scenarios have been proposed [

12]. First, a continuous suppression of CDW1 may increase charge fluctuation to enhance the pairing strength for superconductivity. However, this scenario is not applicable to the pristine CuTe as

TCDW1 decreases to only 100 K at 6.5 GPa, thus mitigating the possibility of having quantum fluctuation of the CDW order parameters. Second, a nominal competition between CDW and SC may induce the stabilization of SC at the expense of the competing CDW order. As is common in a quasi-1D CDW system, the charge density modulation seems to involve significant lattice distortion so that the CDW transition with variation in temperature or pressure is clearly a first-order type. In particular, as a function of pressure, an abrupt first-order transition from CDW1 to CDW2 occurs at ~6.5–6.7 GPa, so that SC is not a single competing phase of the CDW1 order. Indeed, SC stabilized at 4.8 ≤

P ≤ 10 GPa also overlaps with the temperature and pressure windows where CDW2 phase stabilized (i.e., 7.5 GPa (

TCDW2 = 204 K) ≤

P ≤ 10.1 GPa (

TCDW2 = 173 K)). Therefore, the SC appears within the electronic structure created by the CDW2 phase rather than appearing directly at the expense of the CDW1 phase.

To address the puzzling question on the relationship between pressure-induced SC with the CDW order, we have investigated a Cu1-δTe (δ = 0.016) single crystal using high-pressure studies of Raman spectroscopy, transport, and structural properties. Our study reveals that slight Cu deficiency significantly modifies the phase evolution, leading to TCDW1 ≈ 0 K near 6 GPa and subsequent emergence of SC above 5.2 GPa with the maximum TC~3.2 K at 5.6 GPa. Furthermore, we find that a new structural phase, isostructural to the Cu-deficient rickardite CuTe (r-CuTe), appears above 6 GPa, thereby hosting the CDW2 order around 200 K. These findings suggest that understanding the role of Cu deficiency can be crucial for unraveling the intricate relationship between structural transitions, CDW orders, and superconductivity in the copper telluride system.

3. Results

Figure 1a presents an XRD pattern of a Cu

0.984Te single crystal. Only sharp (001) diffraction peaks appear, indicating that the crystallographic

c-axis is perpendicular to the facet of the crystal. The measured (001) peaks match well with those of the vulcanite CuTe (

v-CuTe, space group

Pmmn). Independent XRD experiments on the grounded polycrystals have confirmed the

v-CuTe structure (

Figure S3). Therefore, the Cu

0.984Te crystal is isostructural to the

v-CuTe structure, as illustrated in

Figure 1b, at ambient pressure and at room temperature. In the

v-CuTe structure, the Te chains are known to exist along the

a-axis, and each Cu atom forming a buckled Cu plane is bonded to the four Te atoms located below and above the Cu plane. As a result, the

v-CuTe forms an orthorhombic

Pmmn structure with lattice constants

a = 3.16 Å,

b = 4.08 Å, and

c = 6.93 Å. Wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy confirmed a Cu:Te ratio of 0.984:1.00 (

Figure S4,

Table S1), indicating slight Cu deficiency. We also measured the resistivity along the

a-axis,

ρ, in a Cu

0.984Te single crystal, as shown in

Figure 1c. Despite the slight Cu deficiency, we observe a clear resistivity upturn near 333 K, a feature similar to CuTe at its CDW state [

10,

11].

- B.

Pressure-dependent evolution of Raman phonon modes

To monitor the structural evolution of Cu

0.984Te, we performed high-pressure Raman scattering using diamond anvil cells up to 13.3 GPa at room temperature, as presented in

Figure 1d. From the obtained scattering intensity, the pressure dependence of phonon mode frequencies was extracted as summarized in

Figure 1e. Below 6.2 GPa, only one Raman mode was found at 136.6 cm

−1, which seems to be close to a theoretically predicted frequency of the

A1g mode (136.0 cm

−1) in the

v-CuTe [

11,

19]. However, above 6.7 GPa, three new Raman modes, which do not correspond to the reported Raman modes of the

v-CuTe [

12,

18], emerge at 163.8 cm

−1(

mode 1), 145.8 cm

−1(

mode 2), and 93.8 cm

−1(

mode 3). Meanwhile, the original

A1g mode persists up to 8.3 GPa and disappears above the pressure. These spectral changes provide evidence that a new structural phase appearing at 6.7 GPa coexists with the low-pressure

v-CuTe up to 8.3 GPa and becomes solely stabilized above 8.3 GPa. Note that in the pristine CuTe, a pressure-induced structural transition has been reported to occur at 20 GPa from an orthorombic (

Pmmn) to a monoclinic structure (

Cm). However, no structural transition has been reported in a low-pressure regime around ~7 GPa [

11,

12].

One might suspect that the newly appearing modes 2 and 3 at the high pressures may have originated from Te clusters [

19] as they are indeed close to those of the

E modes in pristine Te at ambient pressure (140.7 cm

−1 and 92.2 cm

−1) [

20,

21]. However, if those modes originated from the Te clusters, the

A1 mode of Te would have also been observed, since the intensity of the

A1 mode is known to always be stronger than that of the

E modes, and its frequency lies around ~120–100 cm

−1 in a pressure regime below 15 GPa [

20]. No signal that can be assigned as an

A1 mode of Te was detected around ~100–120 cm

−1 in our experiments performed below 13 GPa. The minimum frequency of the

A1 mode of Te was previously found at ~100 cm

−1 at a pressure of ~8 GPa [

20]; its frequency at high pressures always remains higher than that of mode 3, leading to the conclusion that mode 3 is not the

A1 mode of Te. Moreover, the Raman mode of Te has not been reported previously near the frequency region of ~164 cm

−1 (that of mode 1) in a pressure window below 15 GPa, ruling out the possibility that mode 1 can stem from the possible Te cluster. These observations suggest that the three modes emerging under the pressure above 6.7 GPa are unlikely to originate from possible Te clusters.

According to the previous density functional theory (DFT) calculations on CuTe [

20], it was predicted that the Cu-deficient rickardite structure (

r-CuTe) would have a lower formation energy than the

v-CuTe. In this theoretical

r-CuTe structure plotted in

Figure 1g [

18,

22], the Cu

2 sites of the rickardite Cu

3Te

2 (

Figure 1f) located close to the four Te sites become completely vacant, and the remaining Cu sites form a flat Cu plane. Although the

r-CuTe forms an orthorhombic structure (space group

Pmmn) with lattice constants

a = 3.845 Å,

b = 3.847 Å, and

c = 6.493 Å, it is indeed close to a tetragonal structure as it has similar in-plane lattice constants. However, this theoretical

r-CuTe phase has not been found experimentally in the high-pressure region of CuTe [

11,

12].

We find in

Figure 1d that three Raman modes appearing at the high pressures above 6.7 GPa match relatively well with those predicted for the

r-CuTe in ref. [

18]; the phonon frequencies of mode 1 (163.8 cm

−1) and mode 2 (145.8 cm

−1) are close to those calculated for the

B2g2/

B3g2 (~164.7 cm

−1) and the

Ag2 (141.1 cm

−1) modes, respectively. According to

Figure 1e, the mode 3 frequency shows a drastic increase with pressure from 93.8 cm

−1 at 6.7 GPa to 115.0 cm

−1 at 13.3 GPa. As a result, the predicted

Ag1 mode frequency (~119.28 cm

−1) [

18] is indeed close to the frequency of 115.0 cm

−1 obtained at 13.3 GPa. As this

Ag1 mode involves the vibrational motion along the

c-axis, its frequency can be sensitive to the interlayer distance; consequently, mode 3 indeed exhibits drastic hardening under pressure. Therefore, mode 3 can be assigned as the

Ag1 mode predicted in the

r-CuTe structure. On the other hand, we could not identify the additional phonon modes near the theoretically predicted

B2g1/

B3g1 mode (78.4 cm

−1) within our experimental resolution.

- C.

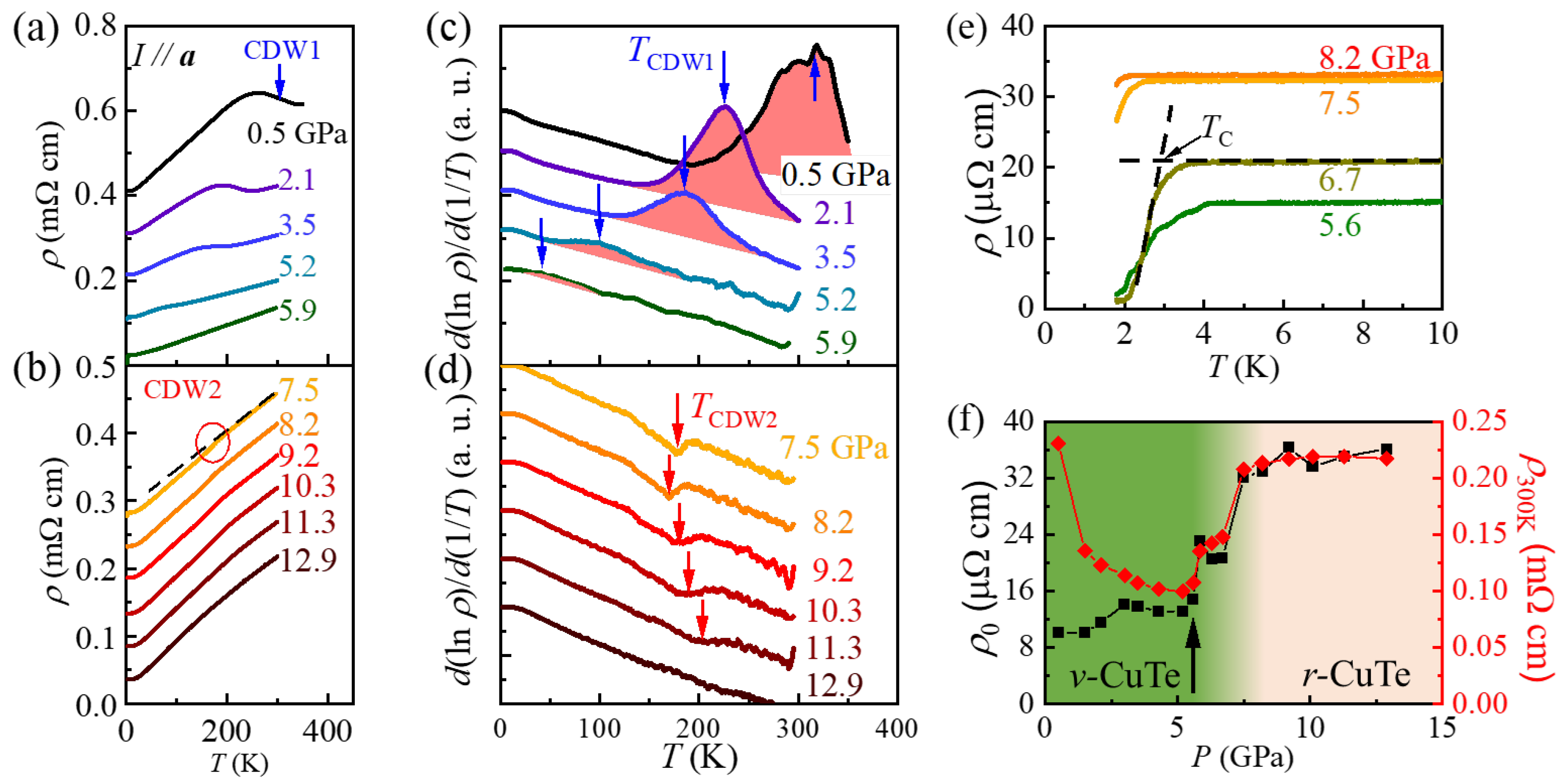

Temperature-dependent resistivity under high pressures

To understand the evolution of electronic orders under external pressure, we have conducted temperature-dependent

ρ measurements at pressures up to 12.9 GPa using a diamond anvil cell (

Figure 2a,b). In the pressure regime starting from 0.5 GPa, we observe a clear

r upturn around 318 K associated with the CDW1 ordering (a blue arrow). With further increase in pressure, the resistivity upturn is progressively weakened and its location is shifted to lower temperatures. Following a convention in the literature [

23], we determine

TCDW1 at each pressure as the peak temperature in the

d ln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curves (

Figure 2c, blue arrows). As a result,

TCDW1, located at 333 K at ambient pressure, systematically decreases to 40 K at 5.9 GPa. At

P above 6.0 GPa, the peak associated with the CDW1 in the

d ln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curves could not be identified.

With a further increase in

P, we find that another kink in the

dln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curves emerges from 7.5 GPa and remains until ~11.3 GPa (red arrows in

Figure 2d). Those kinks are linked to a weak resistivity drop, as illustrated in

Figure 2b (red circles). Previous studies on the pristine CuTe have similarly found a small positive peak in the

dρ/

dT curves [

11]; it was assigned as the onset of the second CDW order (CDW2), based on the observation of the amplitudon mode from Raman scattering measurements [

12]. As the peak feature in the

dρ/

dT curves can appear as a dip in the

dln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curve, we attribute the dip in the

dln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curves to the onset of CDW2 order in Cu

0.984Te.

It is found in

Figure 2d that the determined

TCDW2 from the dip of the

dln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curves exhibits non-monotonous changes with pressure; it decreases from 176 K at 7.5 GPa to 170 K at 8.2 GPa, and again increases to 203 K at 11.3 GPa. This behavior is in contrast to that found in a pristine CuTe, where

TCDW2, determined from the peak in the

dρ/

dT curve, continuously decreases with an increase in

P;

TCDW2 ≈ 204 K at 7.5 GPa decreases linearly down to

TCDW2 ≈ 173 K at 10.1 GPa [

12]. Note that the dip feature in the

dln(

r)/

d(1/

T) curve becomes progressively weakened with further

P increase and finally disappears at 12.9 GPa. We also confirmed that the pressure-dependent evolutions of both

TCDW1 and

TCDW2, as revealed in the

dln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curves of Cu

0.984Te (

Figure 2d), align well with those found in the

dρ/

dT curves (

Figure S5).

At low temperatures, the drop of

r, implying the onset of superconducting transition, appears between 5.2 and 8.2 GPa (

Figure 2e). The onset temperature of the superconducting transition (

TC) is determined by a crossing temperature from the two linear extrapolated lines (dashed lines in

Figure 2e). As a result,

TC reaches a maximum of 3.2 K at 5.6 GPa and gradually decreases with an increase in

P. Note that this value is significantly higher than the maximum

TC = 2.3 K realized at

P ≈ 5.7 GPa in CuTe [

12].

As depicted in

Figure 2f, we also find that both residual resistivity (

ρ0) and resistivity at 300 K (

ρ300K) remain small at

P ≤ ~6 GPa (a black arrow), where the vulcanite structure is dominant. On the other hand, at

P ≥ ~9 GPa, where the

r-CuTe structure is dominant, both

r0 and

ρ300K reach the highest value. In an intermediate regime of 6.7 ≤

P ≤ 8.3 GPa, both

r0 and

ρ300K remain in the intermediate values and exhibit gradual increments. At this intermediate

P regime, the Raman scattering results exhibit evidence of structural coexistence in Cu

0.984Te.

- D.

Structural phase transition and the emergence of CDW2

The emergence of CDW2 in Cu

0.984Te and CuTe occurs in a different manner. In the Cu

0.984Te,

TCDW2 first appears at 176 K and at

P = 7.5 GPa inside the pressure range where the

r-CuTe structure coexists with the

v-CuTe structure (i.e., 6.7 ≤

P ≤ 8.3 GPa). With the stabilization of the

r-CuTe structure (

P ≥ 8.3 GPa),

TCDW2 decreases to 170 K, and increases again to 203 K as

P increases to 11.3 GPa. In contrast, the pristine CuTe exhibits a sudden appearance of the CDW2 phase at 204 K at

P ≥ 6.7 GPa in the

v-CuTe structure, and

TCDW2 decreases monotonically with increasing pressure [

11,

12]. It was previously argued that the CDW2 phase in CuTe may stem from electronic correlation effects induced by four hole pockets originating from Te

pz orbitals, because there is no phonon softening or diverging electronic susceptibilities to support either electron–phonon coupling scenario or Fermi-surface nesting picture, respectively [

12]. However, there is no concrete evidence in the theoretical calculations to support the scenario [

12].

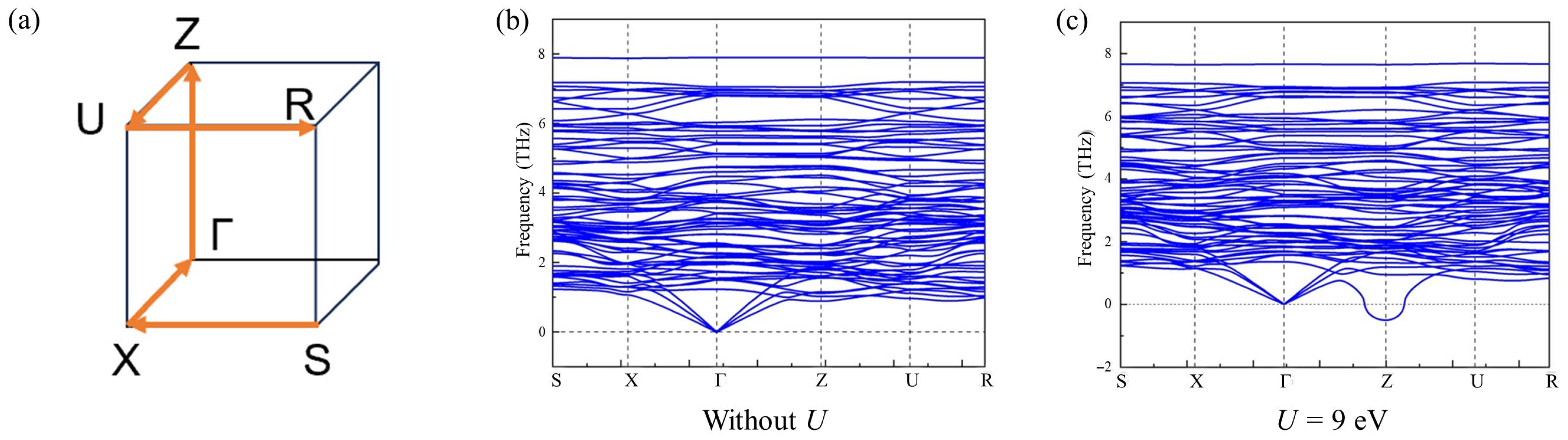

To better understand the origin of stabilizing the CDW2 phase in Cu

0.984Te, we have thus calculated phonon band structures of the

r-CuTe with Cu deficiency, using the Cu

11Te

12 composition at 10 GPa (

Figure 3). For this, the initial atomic positions of the r-CuTe structure, as provided in the

supplementary data as a cif file, were used to have Cu deficiency in the Cu sites. Then, at 10 GPa, the atomic positions of the

r-CuTe structure with Cu deficiency have been relaxed. Since Coulomb interaction can affect the emergence of CDW2, as argued in CuTe [

24], calculations were performed for the cases with or without Coulomb interaction (

U) for Cu 3

d orbitals. Without the Coulomb interaction, there was no structural instability. However, the results reveal a negative phonon mode near the

Z point when the Coulomb interaction

U = 9 eV is included. When

U is systematically increased, it is found that the phonon mode softening was systematically increased at the Z point (See

Figure S6). Our independent calculations of the phonon band structure for the pristine CuTe (

v-CuTe structure) for both with (

U = 9 eV) and without (

U = 0) Coulomb interaction, did not result in any phonon anomaly (See

Figure S7). However, when the chemical potential of the CuTe electronic structure has been shifted toward the hole-doped side, the effect of increasing

U has also resulted in a similar negative phonon mode at a different momentum position (

Figure S7). These results suggest that both Cu deficiency, making hole-doping, and increased Coulomb interactions should be important in creating the CDW2 phase in the high-pressure region of Cu

0.984Te.

- E.

Magnetotransport measurements under high pressure

To monitor the evolution of the electronic structure with pressure, we conducted magnetoresistance (MR) and Hall effects measurements at various pressures.

Figure 4a shows the MR curves, Δ

ρ(

H)/

ρ(0) × 100 = (

ρ(

H) −

ρ(0))/

ρ(0) × 100 at 10 K, and at

P ≥ 1.5 GPa. For 1.5 ≤

P ≤ 5.6 GPa, where CDW1 is stabilized, the MR at 10 K is particularly large, reaching 10–110% at 9 T. Moreover, at this

P regime, MR shows a crossover from

H-quadratic at μ

0H ≤ 2 T (dashed blue line) to linear dependence above μ

0H ≥ ~3 T (dashed red guidelines). As

P increases from 1.5 to 5.6 GPa, MR at 9 T decreases from 110 to 10%, accompanied by similar decreases in the linear slope (red dashed lines). Therefore, the large MR and the linear slope proportional to the MR value should be attributed to the characteristic features of the CDW1 state.

For

P > 6.3 GPa and at 10 K (

Figure 4b), where the CDW2 state in the

r-CuTe structure is dominantly stabilized, the MR values become less than 10% at m

0H = 9 T; they are clearly smaller than those in the lower pressure regime. Moreover, the field-dependence of MR, being proportional to

, exhibits mostly quadratic behavior, i.e.,

, with

β ≈ 2 at μ

0H ≤ ~6 T (dashed blue lines). Detailed analyses of the d

(

H)/dμ

0H curves (

Figure S8) are also consistent with such quadratic

H dependence in the region where the CDW2 state in the

r-CuTe structure is realized.

Numerous materials with CDW order have often exhibited large linear MR below their

TCDWs [

25]. In those cases, the CDW transition can create small electron or hole pockets with sharp curvature, called “sharp corners” in the momentum space. Electrons traveling along these sharply curved trajectories experience abrupt momentum changes, thus strongly influencing the resistivity values. Under magnetic fields, the electrons experience the Lorentz force, causing them to follow the trajectories with a cyclotron frequency proportional to

H. This means that as

H increases, the electrons pass through the trajectory more quickly and thus increase the probability of interaction with the sharp corners. As a result, the number of electrons interacting with such sharp corners can increase linearly with

H, explaining how the CDW state can lead to the linear MR.

Based on the hypothesis that the linear MR in Cu

0.984Te (

Figure 4a) is also caused by the sharp corners in the momentum space as formed inside the CDW1 state [

10], we try to extract the slope

L predicted by the formula of

ρ(

H) =

ρ0 + μ

0L|

H|.

Figure 4e shows the resultant

L extracted from the MR data (

Figure 4a, μ

0H ≥ 3 T) at each pressure; the MR value at μ

0H = 9 T at 10 K is also plotted together. It is found that as

P increases, both

L and MR at 9 T systematically decrease up to 5.9 GPa, at which the CDW1 state is nearly suppressed to become

TCDW1 = 40 K. At

P = 6.3 GPa, the MR exhibits only linear

H-dependence down to ~2 K. With further increase in

P ≥ 6.3 GPa (

Figure 4b), linear MR behavior disappears (thus

L vanishes) and quadratic

H dependence becomes dominant in the

ρ(

H) curves as well, shown in the three representative curves from 7.5 to 12.9 GPa. Moreover, the MR values at 9 T become saturated at ~10%. These results suggest that the reconstructed electronic structure formed by the CDW1 state produces sharp corners in the momentum space to result in the large linear MR. Moreover, upon pressure being increased to enter the CDW2 state, the sharp corners may have almost disappeared.

Figure 4c,d show the Hall resistivity

rxy at 10 K measured at various

P ≤ 6.3 and ≥7.5 GPa, respectively; the evolution of the Hall coefficient

RH extracted at the curves below 1 T is also summarized in

Figure 4f. At

P ≤ ~5.9 GPa, where the CDW1 order is stabilized, the positive

RH values (

Figure 4f) systematically decrease with an increase in

P, indicating that effective carrier density increases with the gradual decrease in the electronic gap inside the CDW1 state. However, even at

P ≥ 6.3 GPa, where the CDW1 state is no longer stabilized at a finite temperature,

RH keeps decreasing to become negative at

P = 7.5 GPa, from which nearly the same negative value is maintained up to

P = 12.9 GPa. In addition, followed by the sign change of

RH near 7.5 GPa,

ρxy starts to exhibit nonlinear

H dependence in the pressure region of ~7.5 ≤

P ≤ 12.9 GPa (

Figure 4d). As

RH values (also

ρxy behaviors) are similar at 7.5 ≤

P ≤ 12.9 GPa, irrespective of the phase boundaries of CDW2 (7.5 ≤

P ≤ 11.3 GPa), it is expected that the

r-CuTe structure, not the CDW2 state, mainly determines the electronic structures.

To analyze the

H dependence of

ρxy under pressure, we used a two-band model with one-hole and one-electron bands [

26,

27]:

Here,

nh (

ne) represents the hole (electron) density,

μh (

μe) is the hole (electron) mobility,

e is one electron charge, and

B is the magnetic induction. This model was applied to fit the

rxy curve at each pressure (see

Figure S9), and the parameters

nh,

ne,

μh, and

μe obtained from the fit are summarized in

Figure 4g,h. It is found that at ~4.3 ≤

P ≤ 7.5 GPa, both

nh and

ne are sharply increased, forming maximum values at the critical pressure of ~5.9 GPa, at which a quantum critical point of the CDW1 state is expected to exist. Simultaneously, both

μh and

μe exhibit a nearly two-fold decrease from

P ≈ 3.5 to 6.7 GPa and a slight increase at 7.5 GPa, thus forming a minimum at 6.7 GPa. At

P ≥ ~7.5 GPa,

μh and

μe remain nearly constant. These observations suggest that a continuous gap closing of the CDW1 state by

P increases up to ~5.9 GPa and associated critical fluctuation of charge amplitude might cause the increase in carrier densities and the decrease in carrier mobilities [

28]. This aligns with the diminishing linear MR as

P approaches ~5.9 GPa, showing that the suppression of the CDW1 order is significantly affecting the transport properties. Furthermore, under the CDW1 order, the electron- and hole-carrier densities, as well as the mobilities, take comparable magnitudes, suggesting a nearly compensated state. Such a condition, likely induced by the Fermi-surface reconstruction under the CDW1 state, can account for the observed large and linear MR [

29,

30,

31].

When a single CDW state is collapsed within the same crystal structure, thereby closing the CDW gap, it is common to observe an increase in the carrier densities outside the CDW state [

32]. However, our results indicate that near the structure coexistence region of the

v- and

r-CuTe (~6.7 ≤

P ≤ 8.3 GPa), the

nh and

ne show abrupt decreases from 6.3 GPa, while

μh and

μe increase slightly. This suggests that, albeit having the gap closing of the CDW1 state, the creation of different structural phases may have resulted in the abrupt reduction in carrier densities. In addition, possible extra-scattering of carriers at the structural domain walls, if any, may be negligible as compared with the effect of critical fluctuation of the CDW1 order (both CDW amplitude and phase). Furthermore, at

P ≥ 7.5 GPa, where the CDW2 state is stabilized, the decreasing behavior of

nh and

ne values is saturated to remain nearly the same, indicating that the electronic structure, as influenced by the CDW2 state in the

r-CuTe phase, is less sensitive to the pressure variation.

4. Discussion

Figure 5a summarizes the pressure-temperature phase diagram of Cu

0.984Te, highlighting distinct regions of structural and electronic phases. Raman spectroscopy, resistivity, and magnetotransport data are used to construct the structural and electronic phase boundaries. The ambient

v-CuTe structure is stabilized below 6.7 GPa, within which the CDW1 order emerges at low temperatures below

TCDW1. As described in the Results, the

r-CuTe structure coexists with the

v-CuTe structure between 6.7 and 8.3 GPa. Above 8.3 GPa, the system fully transforms into the

r-CuTe phase. The CDW2 emerges at ~176 K at

P = 7.5 GPa, and

TCDW2 is gradually enhanced up to 203 K with pressure increase up to 11.3 GPa. However, above 11.3 GPa, the experimental signature of the CDW2 state (i.e., dip in the

dln(

ρ)/

d(1/

T) curves in

Figure 2d) disappears.

We should note that the structural/electronic phase evolution of Cu

0.984Te differs significantly from that of the pristine CuTe [

12] in several aspects (

Figure S1). Firstly, CDW1 in Cu

0.984Te is continuously suppressed with pressure to reach

TCDW1 = 40 K at 5.9 GPa, and the signals related to the CDW1 cannot be found in the transport data above 6.0 GPa. In contrast, the CDW1 state of the pristine CuTe persists up to 6.5 GPa and exhibits

TCDW1~100 K near 6.5 GPa. Secondly, in the Cu

0.984Te, we observe a clear structural phase transition into the

r-CuTe structure and the emergence of the CDW2 state within the

r-CuTe structure. This new structure was absent in the pristine CuTe, while the CDW2 state in CuTe has been found at 7.5 ≤

P ≤ 10.3 GPa. This indicates that the high-pressure structure is not an essential part of inducing the CDW2 instability. Thirdly,

TCDW2 in Cu

0.984Te increases with pressure from 170 K at 8.2 GPa to 203 K at 11.3 GPa. However,

TCDW2 in CuTe decreased with pressure increase; it is found at 204 K at 7.5 GPa and 173 K at 10.3 GPa. Therefore, the slight deficiency of Cu significantly affects both the electronic and structural phase boundaries.

The CDW1 state in Cu

0.984Te shows a decrease of

TCDW1 with pressure increase. Indeed, we found that

TCDW1 decreases rapidly in the low-

P regime (

P ≤ 3.5 GPa) (

Figure 5a). On the other hand, above 3.5 GPa, where

P approaches 6 GPa,

TCDW1 follows a power-law behavior with

with

PC~5.98 ± 0.05 GPa. This power-law behavior with the exponent 0.5 is a typical behavior expected in a mean-field type phase transition [

33]. This characteristic mean field behavior has also been found in several materials near the quantum critical point (QCP) [

28,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], including NbSe

3 [

34,

35] and

β-vanadium bronze [

34,

36], which belong to the Q1D materials exhibiting a CDW formation and a charge ordering, respectively. This emergence of power-law behavior in Cu

0.984Te thus strongly suggests that it may undergo a pressure-induced quantum phase transition of the CDW state, and the CDW fluctuation near

PC plays a role in enhancing

TC.

On the other hand, the continuous evolution of

TCDW1 with pressure, following power-law behavior near

PC is distinctly different from that of the pristine CuTe, in which

TCDW1 decreases almost linearly to 100 K at 6.5 GPa and disappears suddenly in a first-order manner above 6.5 GPa [

12]. The different pressure responses suggest that Cu deficiency may allow the continuous decrease in the electronic CDW1 order parameter (i.e., CDW amplitude) to form the pressure-induced CDW-QCP at 5.98 GPa. For this, the structural transition expected in the CDW instability is decoupled so that the associated anomaly in the Te chain occurs at a higher pressure regime (>6.3 GPa). Note that this behavior is clearly different from that observed in a typical 1D-CDW system, in which a first-order CDW transition often occurs together due to the associated large entropy change involved in the lattice modulation.

To investigate the possible effect of charge fluctuations near

PC on transport phenomena, we have studied the pressure-dependent evolution of the Fermi-liquid behavior at low temperatures above

TC (

Figure 5b,c). Due to the dominant electron-electron scattering of the Fermi-liquids at low temperatures [

38],

ρ exhibits a quadratic

T-dependence of

ρ =

ρ0 +

AT2, where

ρ0 is a residual resistivity and

A is the coefficient of the quadratic term [

39]. In our data for

P ≤ 1.5 GPa, the quadratic power-law successfully describes the

ρ (

T) behavior below~5 K, defined as

TFL. Here,

TFL refers to a coherent temperature, below which a crossover from incoherent to coherent metallic state occurs, and the electron-electron scattering becomes dominant [

38]. Our data thus indicate that the electron-electron scattering is dominant in the transport behavior at ambient and low-pressure region (

P ≤ 1.5 GPa) below

TFL, while the other factors, such as electron-phonon coupling, become more important above

TFL.

It is found that the quadratic

T-dependence persists across all the

P ranges studied.

Figure 5c shows the (

ρab −

ρ0) vs.

T2 plots at various pressures, indicating that (

ρab −

ρ0) is linear with

T2 below

TFL. As

P increases,

TFL rises from 5.6 K at 1.5 GPa to 17.9 K at 5.9 GPa, suggesting an enhancement of the effective Fermi-liquid energy scale near

PC. However, after reaching a maximum at

P~

PC,

TFL drops to ~10 K at 8.2 GPa and remains nearly constant up to 12.9 GPa. (

Figure 5d). This behavior can be interpreted as a modification of the Fermi surface by

P. A larger Fermi surface implies that electrons can maintain a well-defined quasiparticle distribution over a wider

T range, thereby possibly elevating

TFL. Since the suppression of CDW1 often leads to an enlarged Fermi surface, the sharply enhanced

TFL near

PC should be attributed to the increased Fermi surface area. The observed

P-dependent increase in the carrier densities up to 5.9 GPa (

Figure 4g) is also consistent with this picture. However, sharp decreases in both carrier density and

TFL above 5.9 GPa, and their saturated behavior above 8.2 GPa, indicate that the full stabilization of the

r-CuTe structure above

P = 8.2 GPa and its resultant electronic band structure limits the increase in carrier density and Fermi surface.

In the Fermi liquid state, it is known that the Kadowaki-Woods relation,

A =

α KW γ02 [

40], where

α KW is the Kadowaki-Woods ratio and

γ0 is the Sommerfeld coefficient, is satisfied, resulting in the relation that

A1/2 ∝

γ0. Moreover,

γ0 can be expressed as

γ0 =

[

41], where

kB is the Boltzmann constant,

(

) is the electron-electron (electron-phonon) coupling constant, and

is the electronic density of states at the Fermi level. Based on the experimental data summarized in

Figure 5c, we have extracted the pressure

-dependent evolution of

A1/2 (

Figure 5f). Below 3.0 GPa,

A1/2 decreases from 5.75 × 10

−5 Ω

1/2cm

1/2K

−1 at 0.5 GPa to 4.79 × 10

−5 Ω

1/2cm

1/2K

−1 at 3.5 GPa. However, in the range 3.5–6.7 GPa near

PC,

A1/2 exhibits a sharp peak reaching a maximum of 6.65 × 10

−5 Ω

1/2cm

1/2K

−1 at 5.9 GPa. With increasing pressure,

A1/2 gradually decreases again up to 12.9 GPa.

According to the Kadowaki-Woods relation, the evolution of

A1/2 provides insights into changes in

,

, and

. Since the new structural phase in Cu

0.984Te appears above 6.7 GPa,

likely does not change significantly near

PC [

39]. Hence, the increased

A1/2 near

PC seems to arise from the enhancement in

or

. As the effective Fermi surface area is expected to increase upon closing the CDW1 gap, the increasing trend of the

TFL and the carrier density across

PC can be reasonably understood. This may be accompanied by a gradual decrease of

, as the pressure evolution of the electronic structure can result in a decrease in the effective mass. In our experimental results,

A1/2 indeed exhibits a gradual decrease in both low and high pressure regions except near

PC, indicating that the gradual decrease can be explained by the overall decrease of

with pressure. However, to explain the sharp increase of

A1/2 near

PC, where the critical fluctuations of the CDW order parameter are expected, we conjecture that the

increase plays an important role. A similar sharp enhancement of

A1/2 near

PC has also been observed recently in other systems with a CDW-QCP, such as 2

H-Pd

0.05TaSe

2 [

39]. However, it seems quite rare to find experimental evidence of such enhanced charge fluctuation at the critical pressure in a Q1D material. This seems to be realized because the electronic CDW transition is decoupled from the structural transition in Cu

0.984Te due to the Cu deficiency.

The critical behavior of CDW1 in Cu

0.984Te offers new insights into the relation between SC and CDW1. Near

PC,

TC reaches its maximum value of 3.2 K in Cu

0.984Te. This is much higher than that found in pristine CuTe [

12]. The enhancement of

TC near

PC thus suggests that strong CDW1 fluctuation may also contribute to enhancing SC, similar to the recent observations in other systems with the CDW-QCP; Ti-doped CsV

3Sb

5 [

9], Lu(Pt

1-xPd

x)

2In [

42], and 2

H-Pd

0.05TaSe

2 [

39]. In contrast, CDW2 appears to have minimal effect on SC itself because it emerges above 7.5 GPa. Therefore, our observations here underscore the critical role of CDW1 fluctuation in enhancing superconducting pairing strength in Cu

0.984Te, possibly through increased electron-electron interaction.