Bond Strength of Adhesive Mortars to Substrates in ETICS—Comparison of Testing Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Investigation of Wall Geometry and the Thickness of Adhesive Mortar for Thermal Insulation in ETICS

2.2. Empirical Research—Survey-Based

- What actual thickness of the adhesive layer do you most frequently encounter when applying thermal insulation in ETICS?

- What maximum thickness of the adhesive layer do you most frequently encounter when applying thermal insulation in ETICS?

2.3. Laboratory Tests

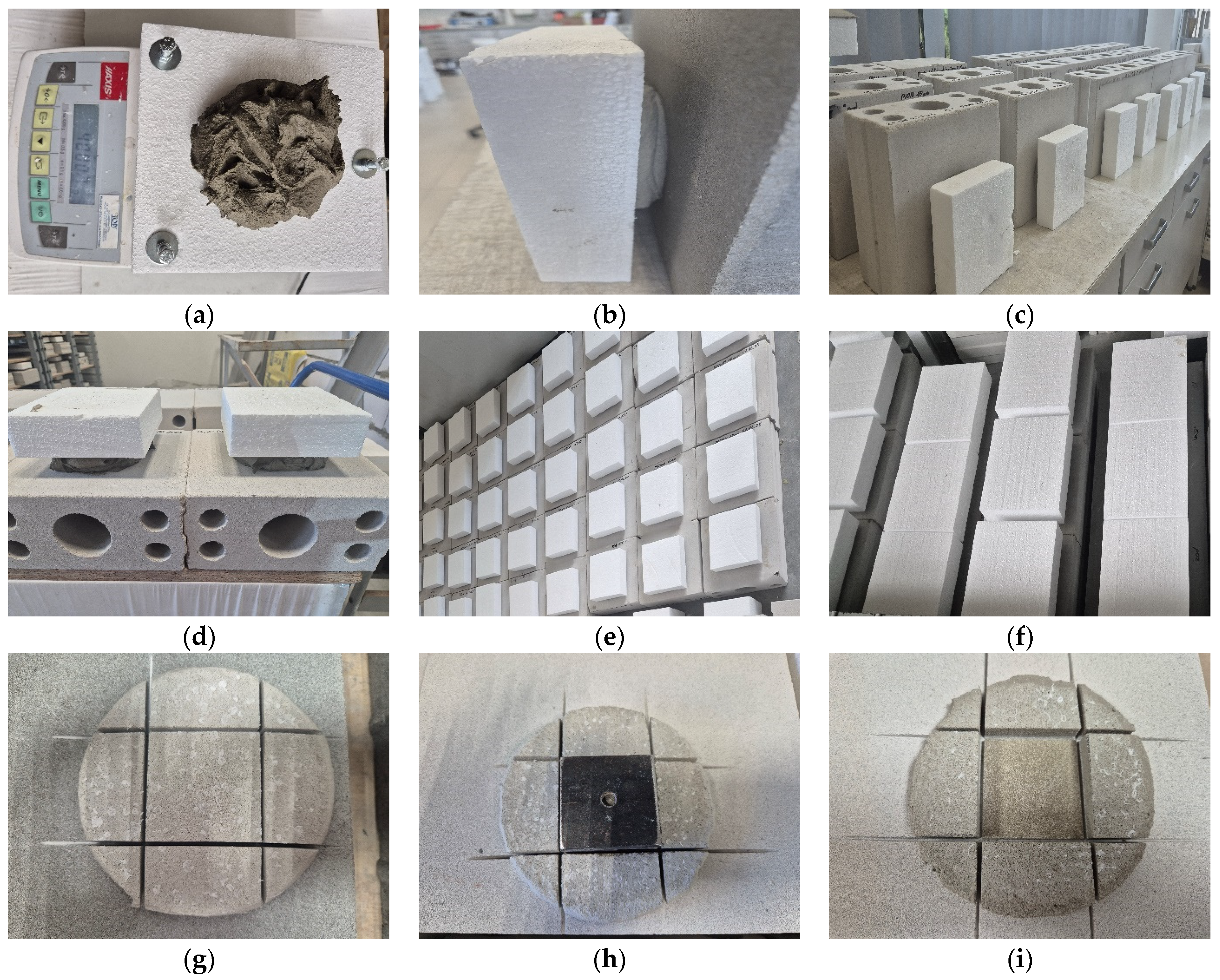

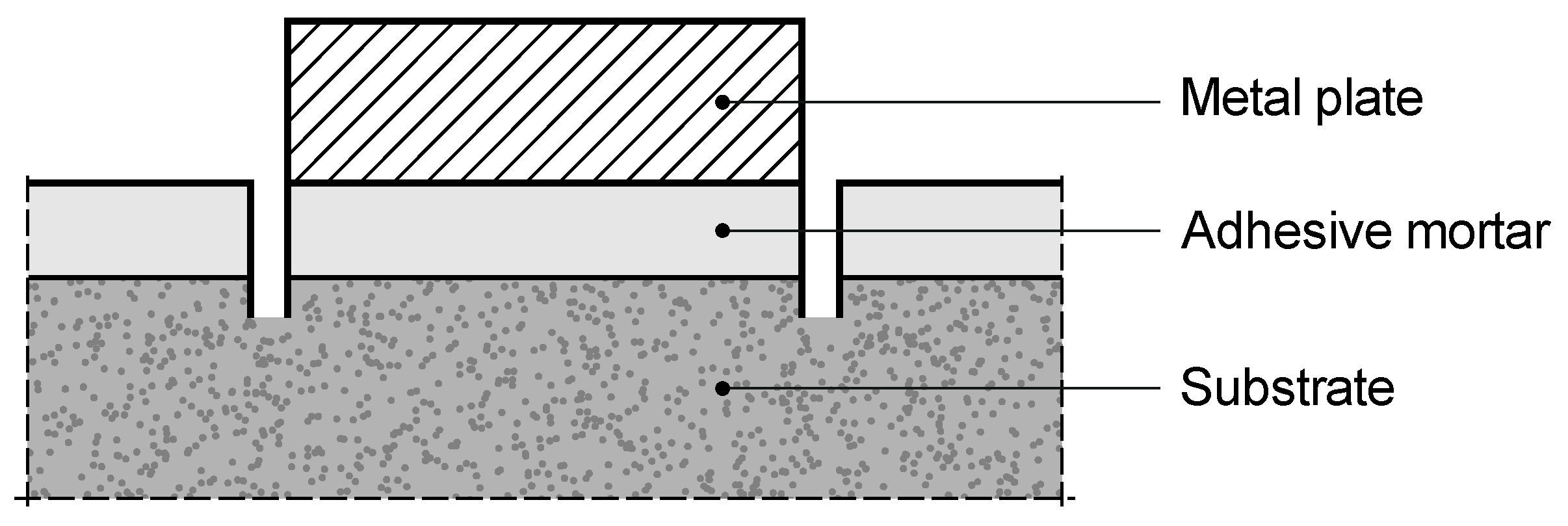

2.3.1. Laboratory Testing of Adhesive Mortars by Means of the CAST Method

- Smooth concrete slabs, tensile strength (perpendicular pull-off) above 1.8 MPa, density approx. 2247 kg/m3, water absorption 28.1 g/(m2 × s0.5), test according to EN 772-11:2011 [25];

- Silicate blocks intended for masonry walls, density 1410–1600 kg/m3, water absorption 188.6 g/(m2 × s0.5), test according to EN 772-11:2011 [25].

2.3.2. Laboratory Testing of Adhesive Mortars by the Standard Method and the Method Based on EAD [15]

- Concrete slabs as defined in Section 2.3.1.

- Silicate blocks as defined in Section 2.3.1.

- These substrates were coded as s0, s1, and s2, respectively.

2.4. Empirical Data Analysis

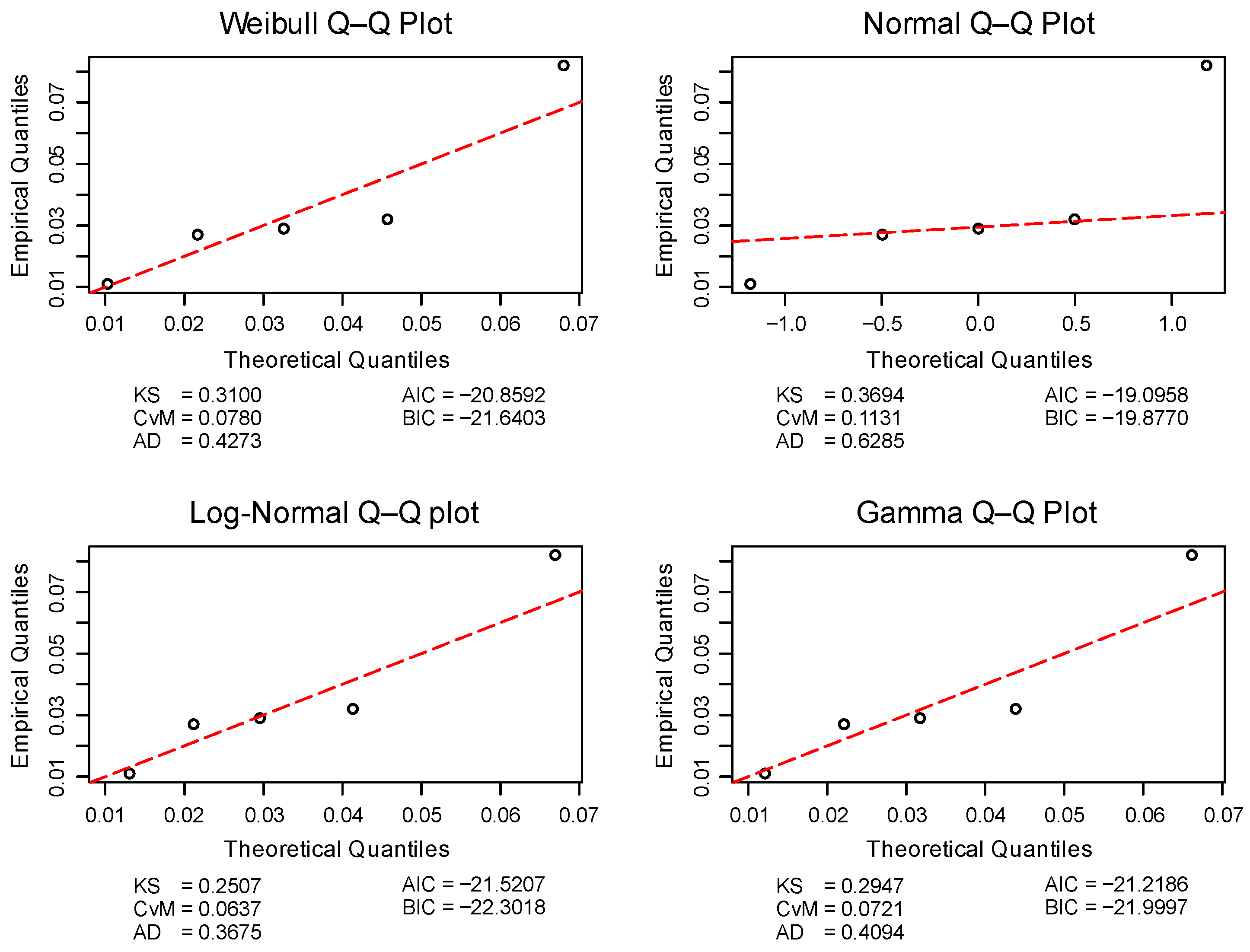

2.4.1. Distributional Assessment

2.4.2. Reporting of Fit Measures

2.4.3. Descriptive Statistics

2.4.4. Bootstrap Resampling

2.4.5. Comparative Metrics

2.4.6. Correlation Analysis

2.4.7. Inferential Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wall Adhesive Mortar for Thermal Insulation in ETICS

3.2. Results of the Survey Concerning the Assessment of the Actual Thickness of the Adhesive Layer for Thermal Insulation

3.3. Bond Strength Results and Analysis

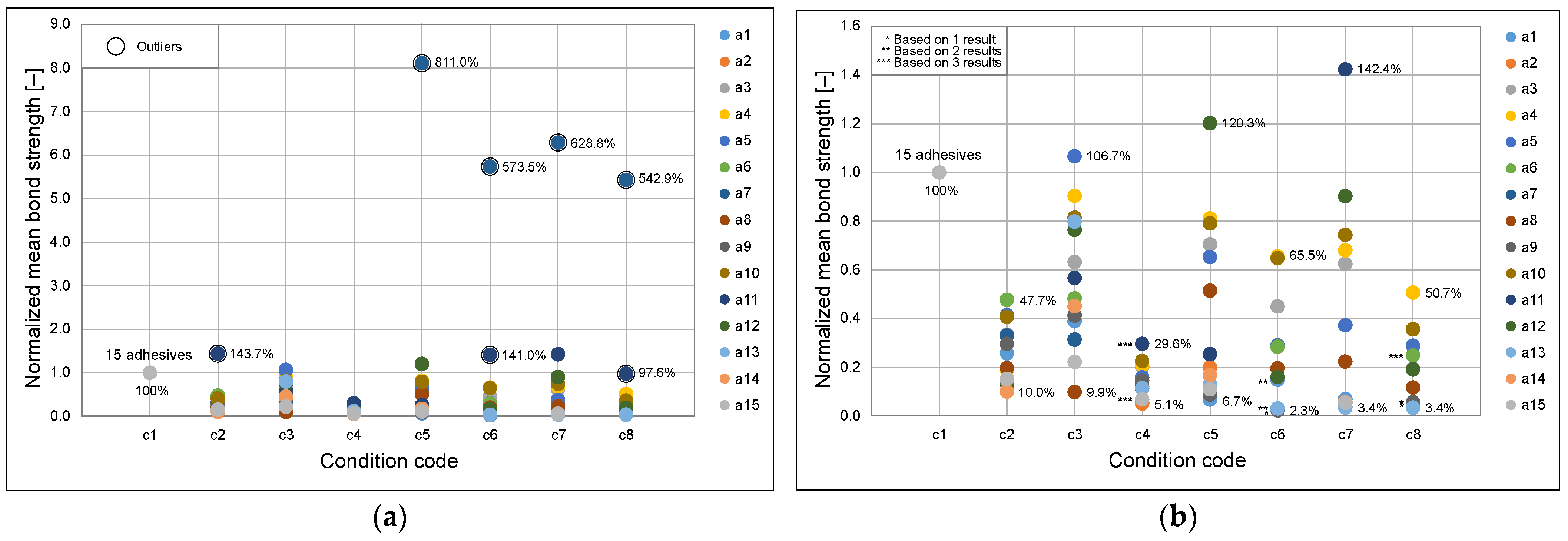

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

- Distributional Characteristics of the Data

- 2.

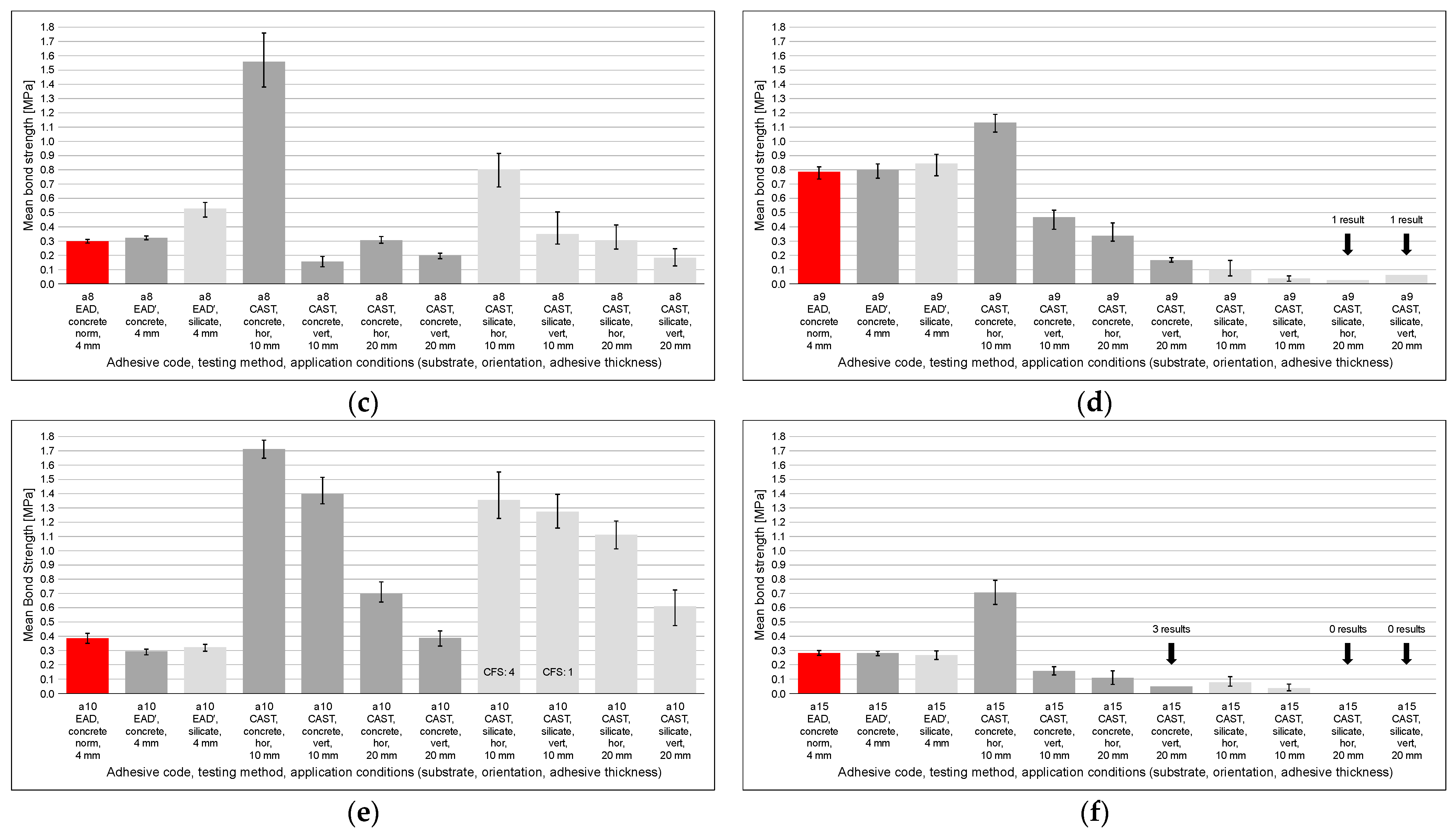

- Results for the CAST Method

- 3.

- Results from the EAD and EAD′ methods

- 4.

- Comparison of results from the EAD/EAD′ and CAST methods;

3.3.2. Inferential Statistics

- 1.

- CAST factorial (substrate × orientation × thickness)

- 2.

- CAST one way by conditions (c1–c8)

- 3.

- EAD one-way by substrate (s0–s2)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETICS | External Thermal Insulation Composite Systems |

| EAD | European Assessment Document; also used to denote the pull-off testing method defined therein |

| EAD′ | Variant of the EAD method applied to “non-normative” substrates |

| EPS | Expanded Polystyrene |

| TR | Tensile Strength Perpendicular to Face (EN 1607) |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| CAST | Central Adhesive Spot Test (in-house method) |

| CFS | Cohesive Fracture in Substrate |

| LE1 | Results limited to values ≤ 1 (Low, Equal 1) |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| BCa | Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (bootstrap CI) |

| SW | Shapiro–Wilk (test) |

| KS | Kolmogorov–Smirnov (test) |

| CvM | Cramér–von Mises (test) |

| AD | Anderson–Darling (test) |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| Q–Q | Quantile–Quantile |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| MAD | Median Absolute Deviation |

| MedAD | Mean Absolute Deviation from the Median |

| MedADn | Scaled Median Absolute Deviation (normalized) |

| PEMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination (as variance explained) |

| η2 | Eta-squared (effect size) |

| ε2 | Epsilon-squared (effect size) |

| δ | Cliff’s delta (effect size) |

| VD-A | Vargha–Delaney A (effect size) |

| ART | Aligned Rank Transform |

| ρ | Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient |

| τ | Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient |

| p | Probability value (statistical significance) |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| IDE | Integrated Development Environment |

References

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2024/1275 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, L 1275, 1–62. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- European Commission. A Renovation Wave for Europe—Greening Our Buildings, Creating Jobs, Improving Lives; COM(2020) 662 Final, Brussels, 14 October 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0662 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Rada Ministrów RP. Uchwała nr 91 z dnia 22 Czerwca 2015 r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia “Krajowego Planu Mającego na Celu Zwiększenie Liczby Budynków o Niskim Zużyciu Energii”. Monitor Polski, 2015; poz. 614. [Google Scholar]

- Rada Ministrów RP. Uchwała nr 23/2022 z Dnia 9 Lutego 2022 r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia “Długoterminowej Strategii Renowacji Budynków”. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj-technologia/Dlugoterminowa-strategia-renowacji-budynkow (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Obwieszczenie Ministra Rozwoju i Technologii z Dnia 15 Kwietnia 2022 r. w Sprawie Ogłoszenia Jednolitego Tekstu Rozporządzenia Ministra Infrastruktury w Sprawie Warunków Technicznych, Jakim Powinny Odpowiadać Budynki i Ich Usytuowanie. Dziennik Ustaw 2022, poz. 1225; z późn. zm.: Dz.U. 2023, poz. 2442; Dz.U. 2024, poz. 474; Dz.U. 2024, poz. 726. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220001225 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Nowoświat, A.; Miros, A.; Krause, P. Change in the Properties of Expanded Polystyrene Exposed to Solar Radiation in Real Aging Conditions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norvaišienė, R.; Krause, P.; Buhagiar, V.; Burlingis, A. Resistance of ETICS with Fire Barriers to Cyclic Hygrothermal Impact. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajsnar, A. Deweloperzy Budują Coraz Wyższe Bloki? Sprawdzamy dane GUS. Bankier.pl. 31 May 2025. Available online: https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Deweloperzy-buduja-coraz-wyzsze-bloki-Sprawdzamy-dane-GUS-8949978.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Krause, P. Thermal conductivity of the curing concrete. Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2008, 1, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland (GUS). New Residential Buildings Completed—Construction Technologies (Quarterly), Dataset P4135; Local Data Bank (BDL); Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Bond, D.E.M.; Clark, W.W.; Kimber, M. Configuring wall layers for improved insulation performance. Appl. Energy 2013, 112, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorowska, R.; Sieczkowski, J. Warunki Techniczne Wykonania i Odbioru Robót Budowlanych; Część C: Zabezpieczenia i Izolacje. Zeszyt 8: Złożone Systemy Ocieplania Ścian Zewnętrznych Budynków (ETICS) z Zastosowaniem Styropianu lub Wełny Mineralnej i Wypraw Tynkarskich; Instytut Techniki Budowlanej: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stowarzyszenie na Rzecz Systemów Ociepleń (SSO). Warunki Techniczne Wykonawstwa, Oceny i Odbioru Robót Elewacyjnych z Zastosowaniem ETICS, 06/2022 ed.; SSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; Available online: http://www.systemyocieplen.pl/pliki/SSO_wytyczne_11.2_K.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Michalak, J. External Thermal Insulation Composite Systems (ETICS) from Industry and Academia Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAD 040083-00-0404; External Thermal Insulation Composite Systems (ETICS) with Renderings. European Organisation for Technical Assessment (EOTA): Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Published 2020.

- European Organisation for Technical Assessment (EOTA). EAD 040287-00-0404: Kits for External Thermal Insulation Composite System (ETICS) with Panels as Thermal Insulation Product and Discontinuous Claddings as Exterior Skin; EOTA: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gaciek, P.; Krause, P. Mocowanie klejowe izolacji termicznej do podłoża w systemie ETICS—Analiza wytycznych. Przegląd Bud. 2023, 9–10, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudoł, E.; Kozikowska, E. Mechanical Properties of Polyurethane Adhesive Bonds in a MineralWool-Based External Thermal Insulation Composite System for Timber Frame Buildings. Materials 2021, 14, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanho, S.; Veiga, M.R. Bond Strength between Layers of ETICS—Influence of the Characteristics of Mortars and Insulation Materials. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Organisation for Technical Approvals (EOTA). Guideline for European Technical Approval of External Thermal Insulation Composite Systems with Rendering (ETAG 004); EOTA: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, R.; Rinaldi, M.; Trullo, M.; Tornabene, F. Numerical Modeling of Single-Lap Shear Bond Tests for Composite-Reinforced Mortar Systems. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitri, R.; Rinaldi, M.; Tornabene, F.; Micelli, F. Numerical Study of the FRP–Concrete Bond Behavior under Thermal Variations. Curved Layer. Struct. 2023, 10, 20220193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaciek, P.; Gaczek, M.; Krause, P. Factors Influencing Adhesive Bonding Efficiency in ETICS Application. Materials 2025, 18, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaciek, P. CAST (Central Adhesive Spot Test): An Original Method of Testing Adhesion in the Central Area of the Adhesive Dab Using the Pull-Off Method; BOLIX: Żywiec, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EN 772-11:2011; Methods of Test for Masonry Units—Part 11: Determination of Water Absorption of Aggregate Concrete, Autoclaved Aerated Concrete, Manufactured Stone and Natural Stone Masonry Units Due to Capillary Action and the Initial Rate of Water Absorption of Clay Masonry Units. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, version 2025.05.0+496; Posit Software; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Delignette-Muller, M.L.; Dutang, C. fitdistrplus: An R Package for Fitting Distributions. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 64, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-387-95457-0. Available online: https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Therneau, T. A Package for Survival Analysis in R, R Package Version 3.8-3; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Therneau, T.M.; Grambsch, P.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-387-98784-3. [Google Scholar]

- Canty, A.; Ripley, B. Boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions, R Package version 1.3-31; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, A.C.; Hinkley, D.V. Bootstrap Methods and Their Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; ISBN 0-521-57391-2. [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. Fast R Functions for Robust Correlations and Hierarchical Clustering. J. Stat. Soft. 2012, 46, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package, R Package version 2.7-1; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, B.; Torchiano, M. lmPerm: Permutation Tests for Linear Models, R Package version 2.1.4; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shachar, M.; Lüdecke, D.; Makowski, D. effectsize: Estimation of Effect Size Indices and Standardized Parameters. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchiano, M. Effsize: Efficient Effect Size Computation, R Package version 0.8.1; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, M.; Elkin, L.; Higgins, J.; Wobbrock, J. ARTool: Aligned Rank Transform for Nonparametric Factorial ANOVAs, R Package version 0.11.2; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobbrock, J.; Findlater, L.; Gergle, D.; Higgins, J. The Aligned Rank Transform for Nonparametric Factorial Analyses Using Only ANOVA Procedures. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’11), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T.; Hornik, K.; van de Wiel, M.A.; Zeileis, A. A Lego System for Conditional Inference. Am. Stat. 2006, 60, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T.; Hornik, K.; van de Wiel, M.A.; Zeileis, A. Implementing a Class of Permutation Tests: The coin Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D.J. Learning Statistics with R: A Tutorial for Psychology Students and Other Beginners (Version 0.6); University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://learningstatisticswithr.com (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, R Package version 1.1.5; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics IBP. WUFI® Pro; Version 6.7; Material Database Version 27.5.0.86; Fraunhofer IBP: Holzkirchen, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cziesielski, E.; Vogdt, F.U. Schäden an Wärmedämm-Verbundsystemen. In Schadenfreies Bauen; Zimmermann, G., Ed.; Fraunhofer IRB Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2000; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- TU Berlin. Keramische Bekleidungen auf Wärmedämmverbundsystemen und Massiven Untergründen (Dr.-Ing. S. Himburg). Available online: https://www.tu.berlin/bauphysik/forschung/abgeschlossene-projekte/keramische-bekleidungen-auf-wdvs (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Liu, H.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, J. Interface bonding properties of new and old concrete: A review. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1389785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salustio, J.; Torres, S.M.; Melo, A.C.; Silva, Â.J.C.e.; Azevedo, A.C.; Tavares, J.C.; Leal, M.S.; Delgado, J.M.P.Q. Mortar Bond Strength: A Brief Literature Review, Tests for Analysis, New Research Needs and Initial Experiments. Materials 2022, 15, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesza, M.; Dębski, D.; Fangrat, J.; Michalak, J. Effect of redispersible polymer powders on selected mechanical properties of thin-bed cementitious mortars. Cem. Wapno Beton = Cem. Lime Concr. 2020, 25, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwica, Ł.; Małolepszy, J. Polymer-cement and polymer-alite interactions in hardening of cement-polymer composites. Cem. Wapno Beton = Cem. Lime Concr. 2012, 17, 12–16. Available online: https://www.cementwapnobeton.pl/Polymer-cement-and-polymer-alite-interactions-in-hardening-of-cement-polymer-composites,177587,0,2.html (accessed on 17 October 2025).

| Condition Codes | Substrate | Substrate Orientation | Adhesive Thickness [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| c1: s1-o1-t1 | Concrete slab | Horizontal | 10 |

| c2: s1-o1-t2 | 20 | ||

| c3: s1-o2-t1 | Vertical | 10 | |

| c4: s1-o2-t2 | 20 | ||

| c5: s2-o1-t1 | Silicate block | Horizontal | 10 |

| c6: s2-o1-t2 | 20 | ||

| c7: s2-o2-t1 | Vertical | 10 | |

| c8: s2-o2-t2 | 20 |

| Condition Codes | Min [MPa] | Max [MPa] | Median [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|

| c1: s1-o1-t1 | 0.1696 | 1.8576 | 0.7218 |

| c2: s1-o1-t2 | 0.0390 | 0.6968 | 0.1718 |

| c3: s1-o2-t1 | 0.0532 | 1.3968 | 0.3628 |

| c4: s1-o2-t2 | 0.0340 | 0.3868 | 0.1176 |

| c5: s2-o1-t1 | 0.0310 | 1.3754 | 0.1420 |

| c6: s2-o1-t2 | 0.026 (0.0335) | 1.1102 | 0.2570 (0.3048) |

| c7: s2-o2-t1 | 0.0182 | 1.2744 | 0.2688 |

| c8: s2-o2-t2 | 0.035 (0.0370) | 0.9208 | 0.2034 (0.2483) |

| Substrate | Orientation | Mean [95% CI] | Median [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Results | Results ≤ 1 | All Results | Results ≤ 1 | ||

| Concrete slab | Horizontal | 0.3334 [0.232, 0.627] | 0.2545 [0.198, 0.321] | 0.2571 [0.148, 0.334] | 0.2266 [0.148, 0.332] |

| Vertical | 0.3432 [0.234, 0.638] | 0.2583 [0.202, 0.339] | 0.2629 [0.148, 0.320] | 0.2488 [0.142, 0.311] | |

| Silicate block | Horizontal | 1.2840 [0.656, 2.629] | 0.4917 [0.339, 0.653] | 0.6723 [0.321, 1.515] | 0.4444 [0.236, 0.707] |

| Vertical | 1.0639 [0.648, 2.427] | 0.5940 [0.431, 0.716] | 0.7517 [0.479, 0.890] | 0.6852 [0.309, 0.758] | |

| Substrate | Adhesive Thickness | Mean [95% CI] | Median [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Results | Results ≤ 1 | All Results | Results ≤ 1 | ||

| Concrete slab | 10 mm | 0.5653 [0.432, 0.710] | 0.5267 [0.398, 0.652] | 0.5245 [0.363, 0.781] | 0.4824 [0.314, 0.631] |

| 20 mm | 0.5321 [0.410, 0.688] | 0.4848 [0.375, 0.602] | 0.4911 [0.252, 0.605] | 0.4713 [0.252, 0.605] | |

| Silicate block | 10 mm | 0.9438 [0.566, 2.269] | 0.5792 [0.458, 0.709] | 0.5871 [0.392, 0.838] | 0.5709 [0.337, 0.750] |

| 20 mm | 0.9107 [0.701, 1.362] | 0.6896 [0.544, 0.824] | 0.8238 [0.550, 1.026] | 0.6921 [0.429, 0.873] | |

| Substrate | Conditions Ratio | Mean [95% CI] | Median [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Results | Results ≤ 1 | All Results | Results ≤ 1 | ||

| Concrete slab | c4/c1 | 0.1449 [0.111, 0.188] | No ratios exceed 1 | 0.1265 [0.069, 0.158] | No ratios exceed 1 |

| Silicate block | c8/c5 | 0.9310 [0.459, 1.867] | 0.4517 [0.330, 0.579] | 0.5376 [0.261, 0.706] | 0.4461 [0.243, 0.634] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaciek, P.; Gaczek, M.; Krause, P. Bond Strength of Adhesive Mortars to Substrates in ETICS—Comparison of Testing Methods. Materials 2025, 18, 4977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214977

Gaciek P, Gaczek M, Krause P. Bond Strength of Adhesive Mortars to Substrates in ETICS—Comparison of Testing Methods. Materials. 2025; 18(21):4977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214977

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaciek, Paweł, Mariusz Gaczek, and Paweł Krause. 2025. "Bond Strength of Adhesive Mortars to Substrates in ETICS—Comparison of Testing Methods" Materials 18, no. 21: 4977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214977

APA StyleGaciek, P., Gaczek, M., & Krause, P. (2025). Bond Strength of Adhesive Mortars to Substrates in ETICS—Comparison of Testing Methods. Materials, 18(21), 4977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214977