Uncertainty Quantification of the Mechanical Properties of 2D Hexagonal Cellular Solid by Analytical and Finite Element Method Approach

Highlights

- The determination of the mechanical properties of the 2D hexagonal cellular solids with FEM, as well as the comparison of the analytical and numerical approximations of the effective elasto-plastic properties, provided superior accuracy in capturing localized nonlinear effects.

- The probabilistic, analytical, and Finite Element Method-based homogenization of the cellular material in the elasto-plastic regime provided superior accuracy in capturing localized nonlinear effects.

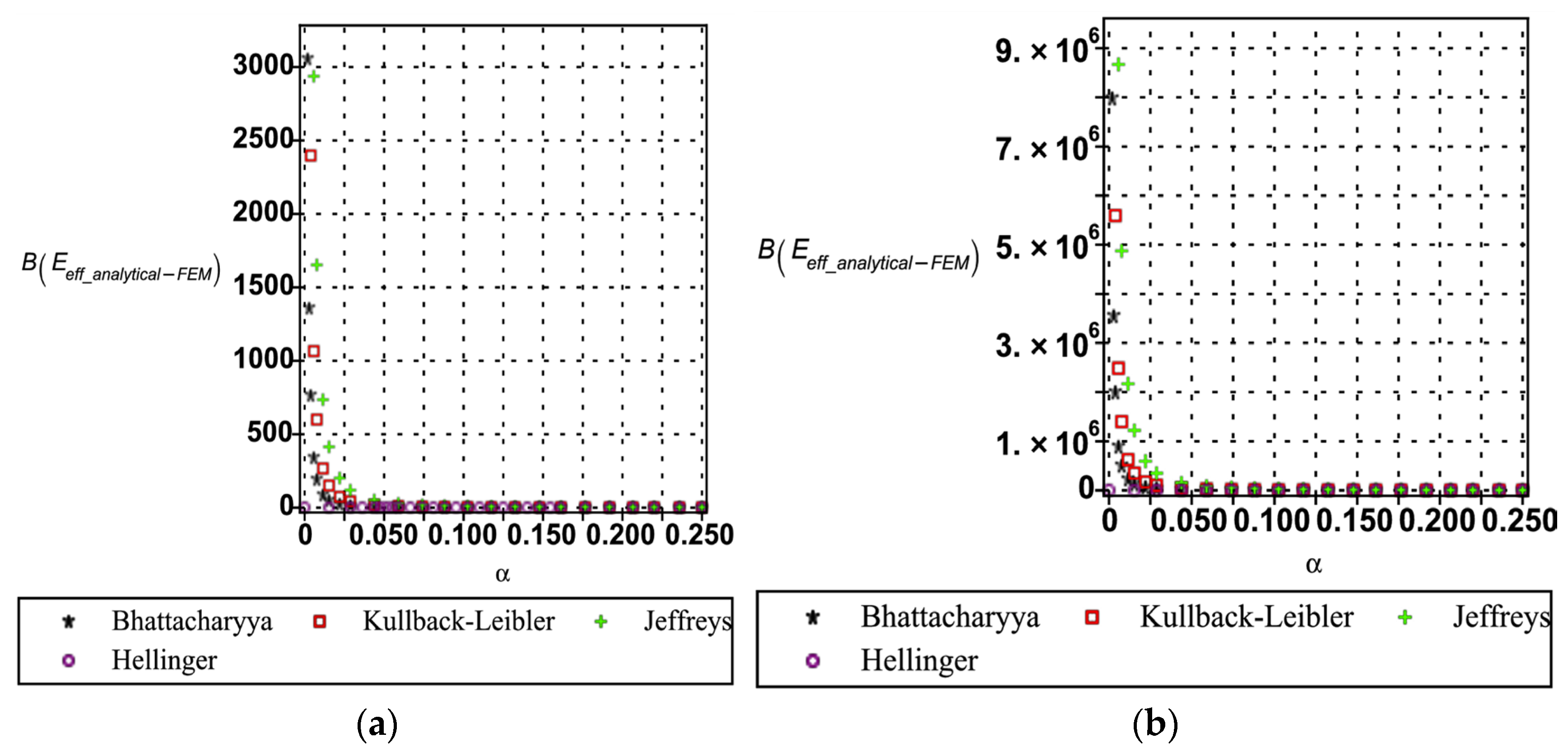

- The relative entropy quantification of the deviation between the analytical and numerical homogenization procedures provided a validated basis for the uncertainty-aware design of lightweight and multifunctional materials.

Abstract

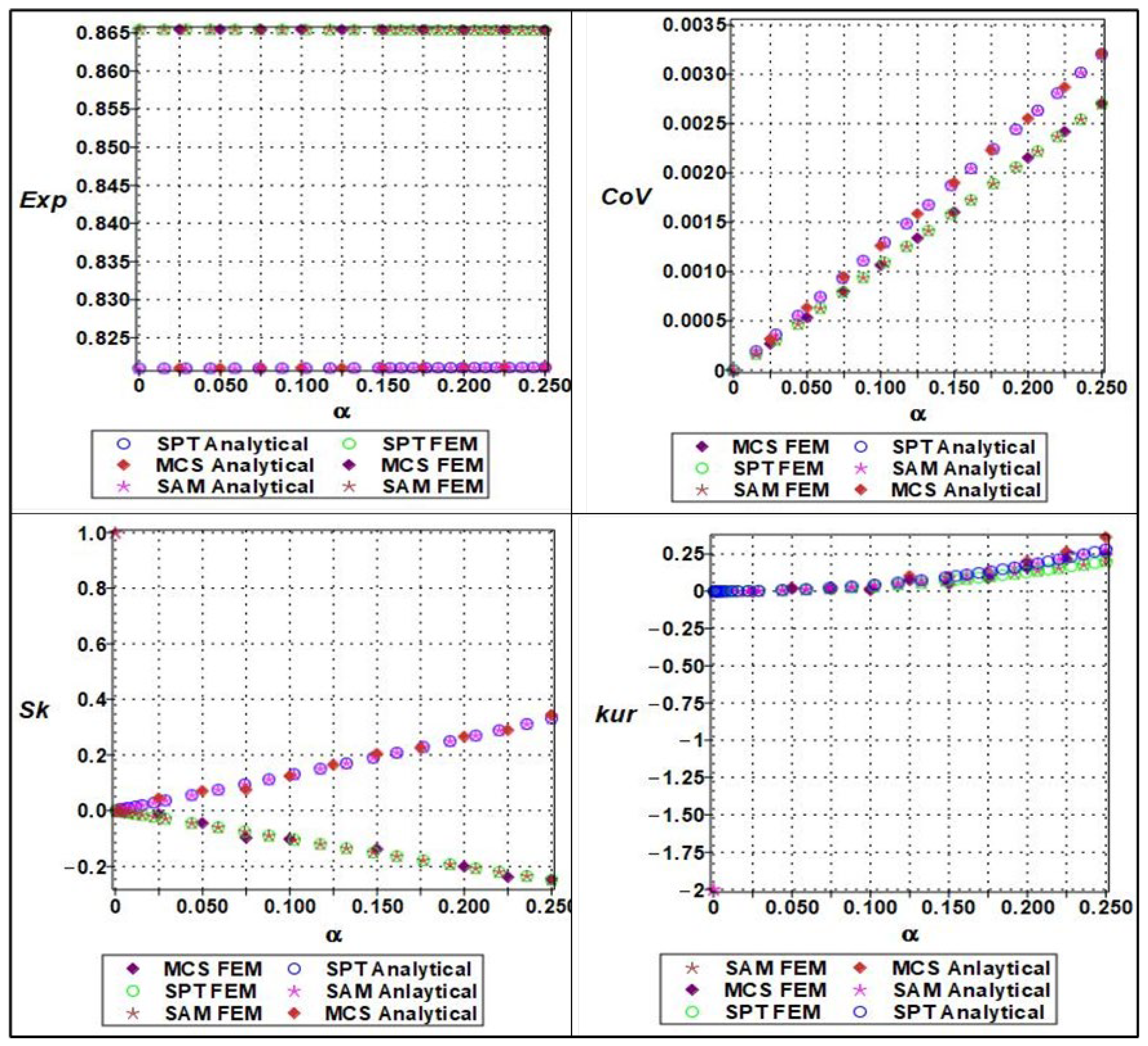

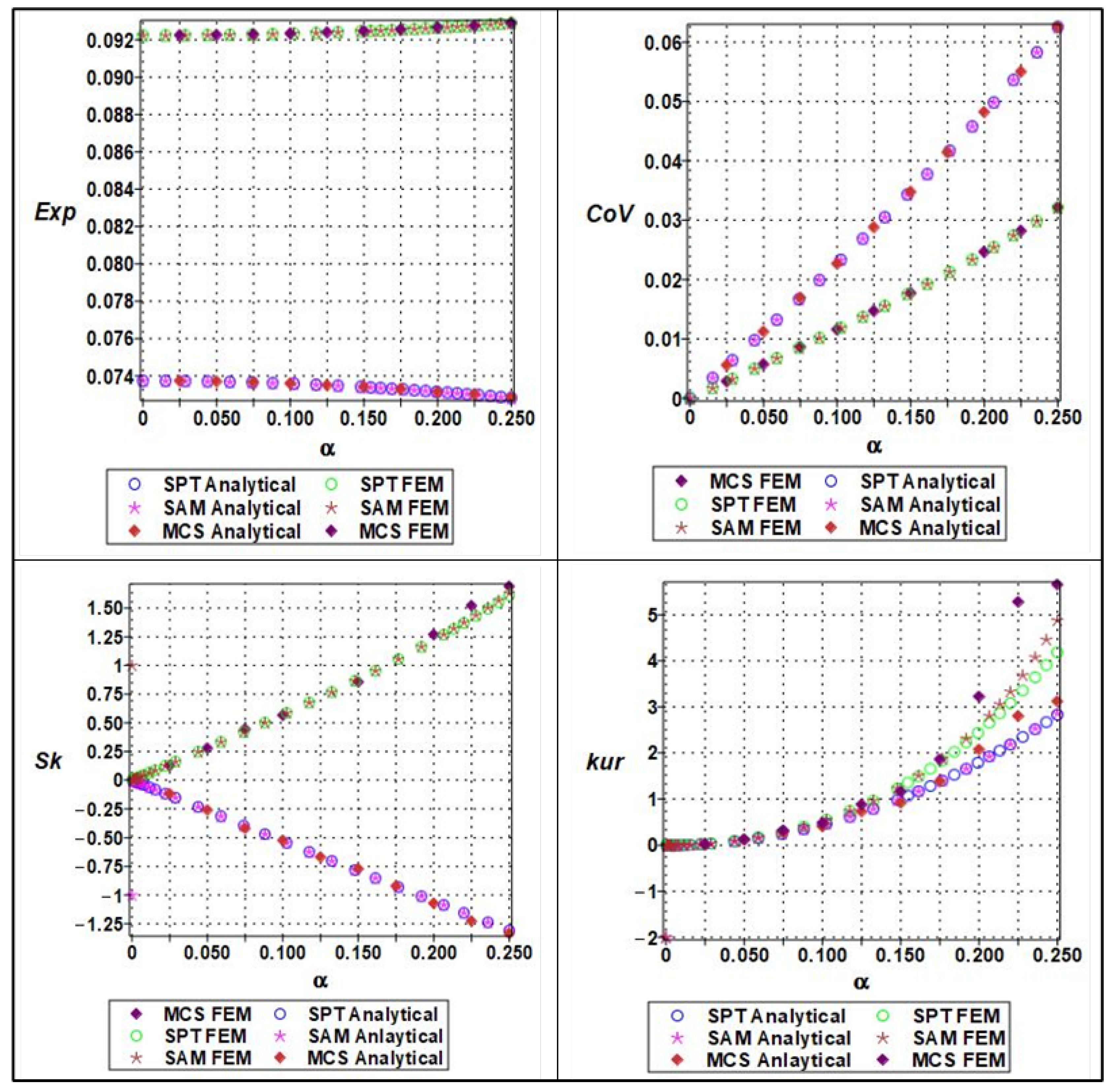

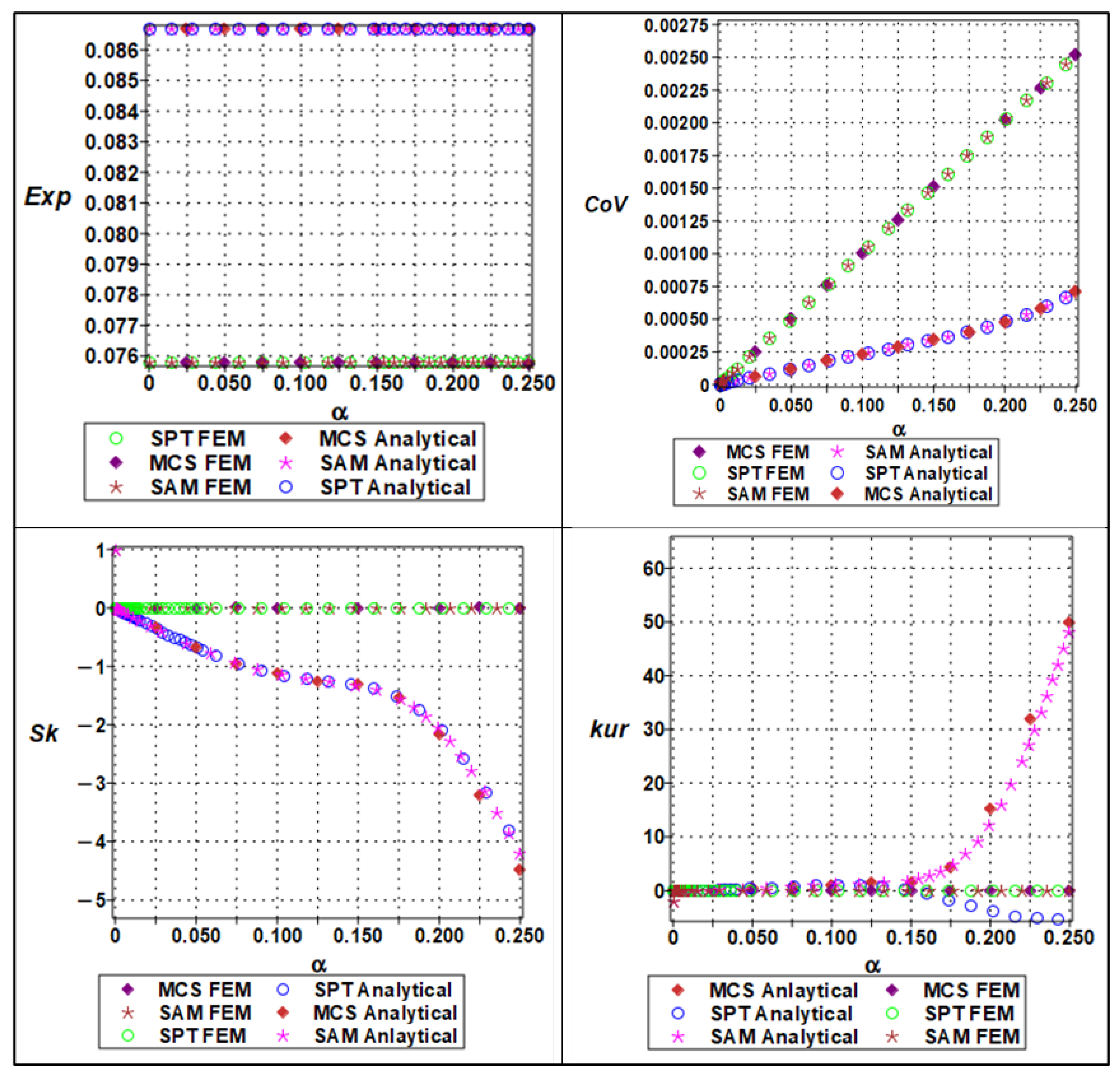

1. Introduction

2. Analytical Model

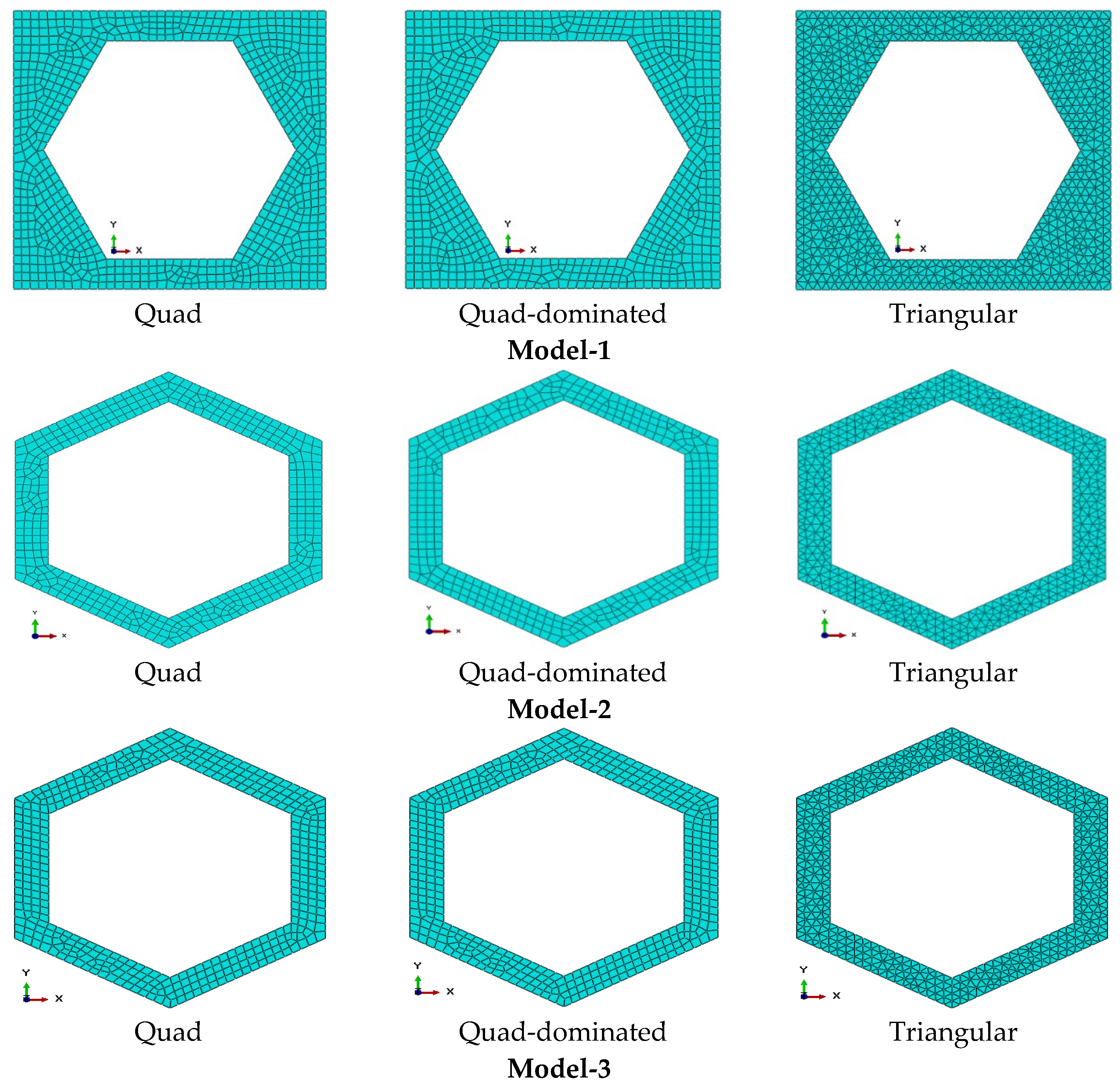

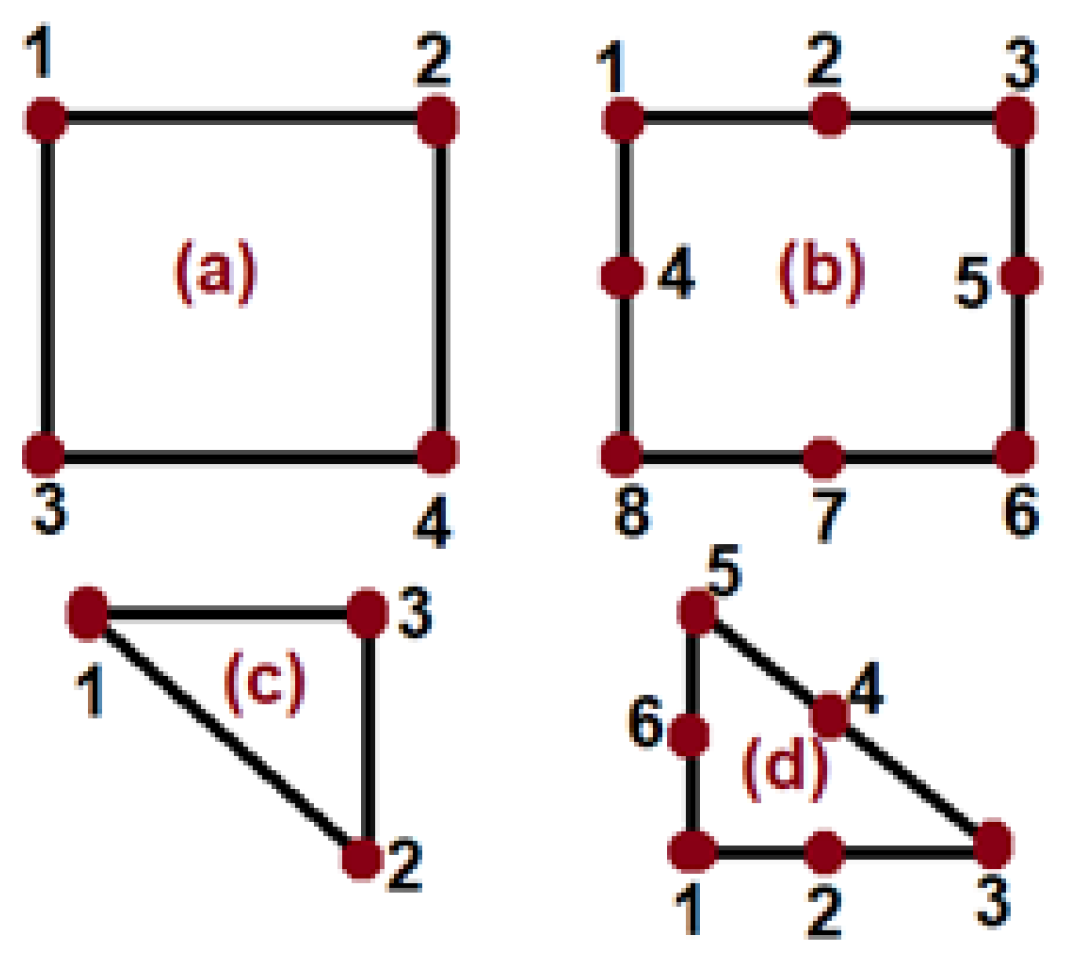

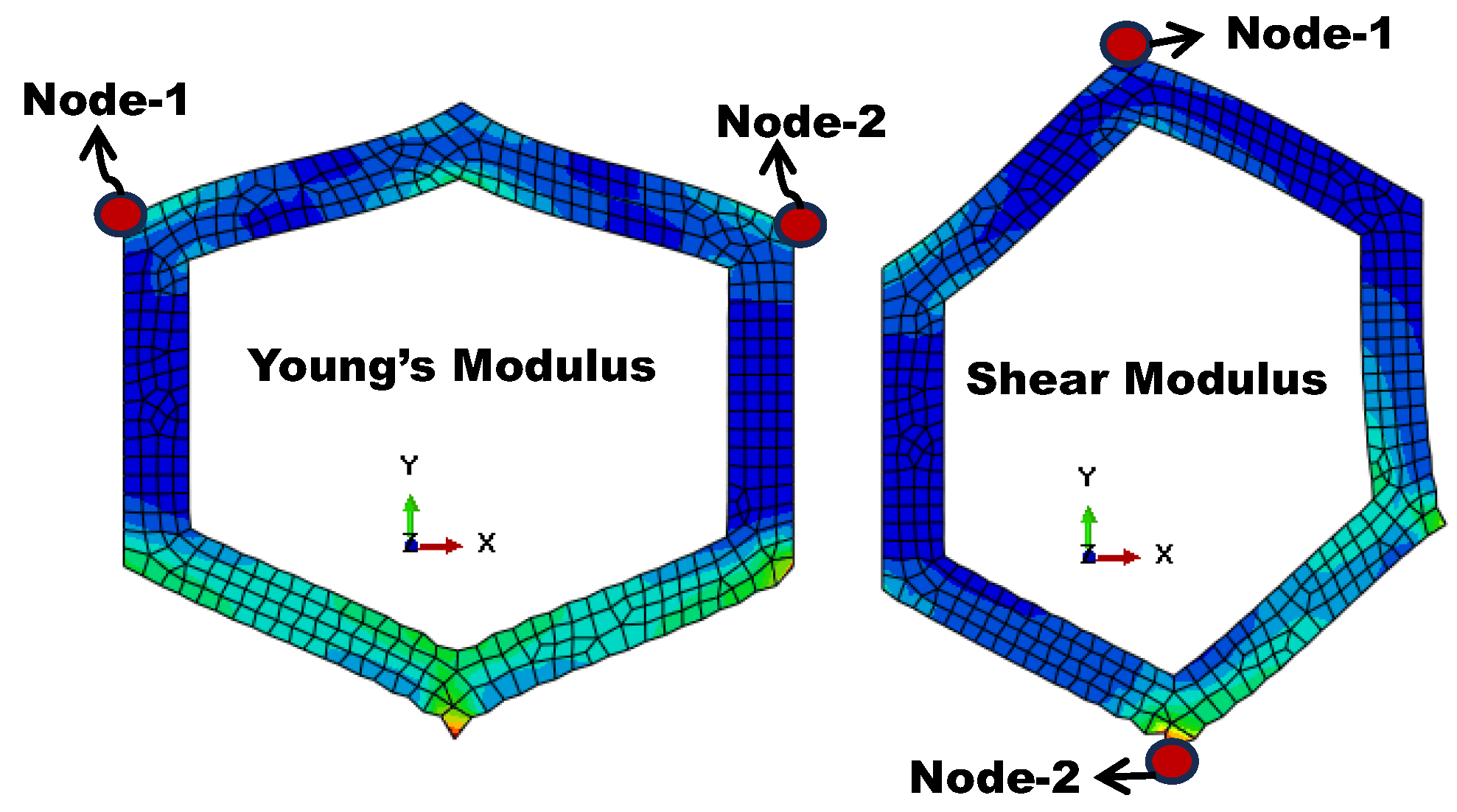

3. Numerical Analysis

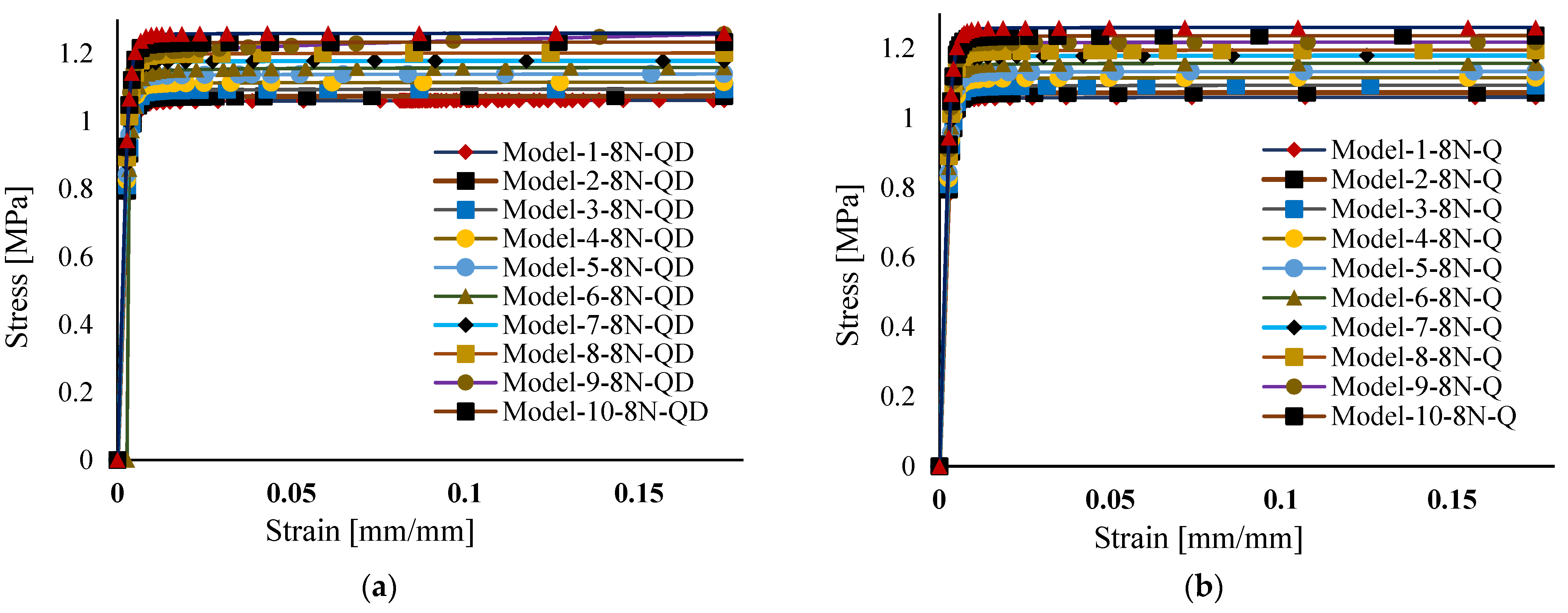

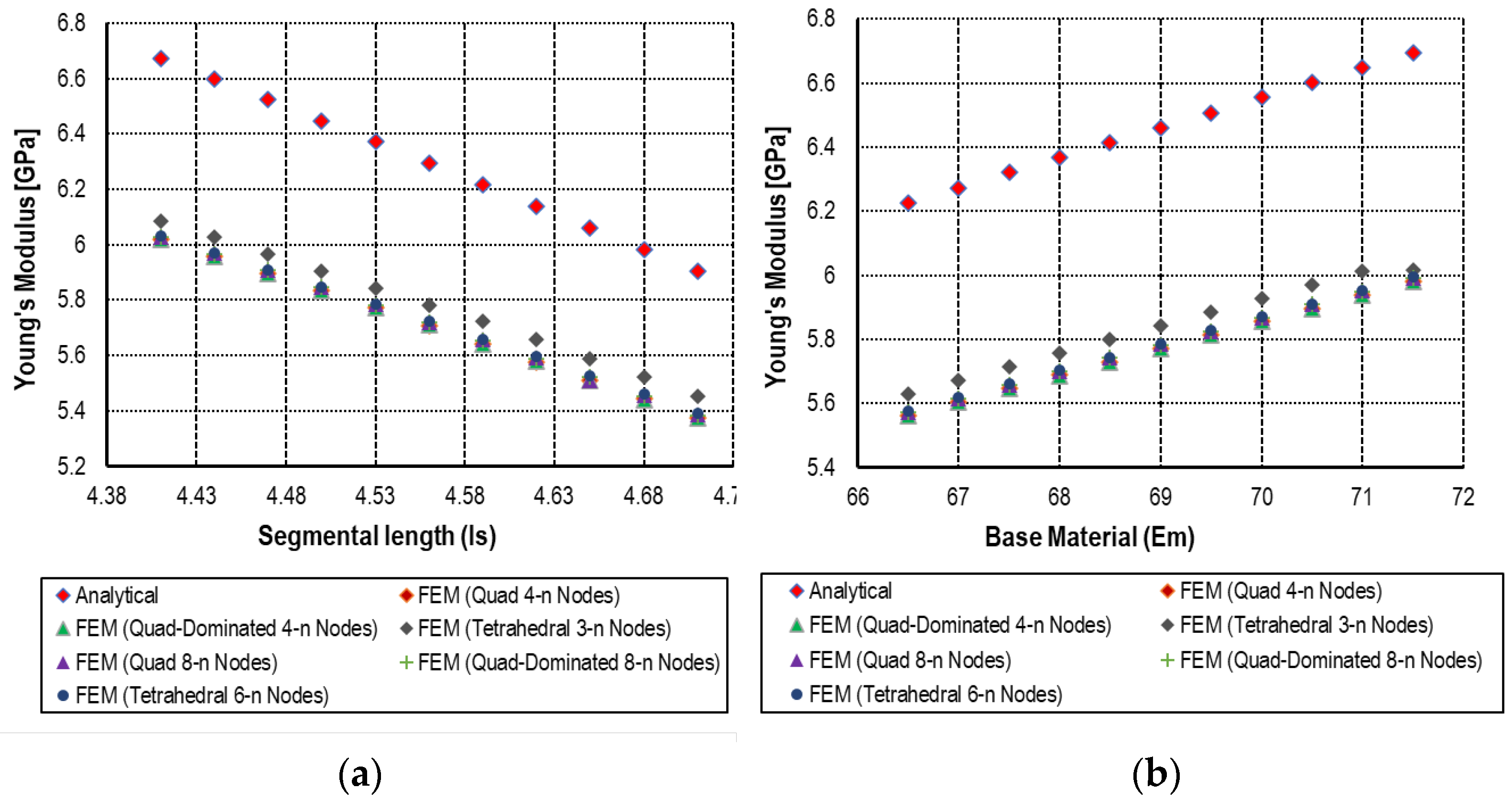

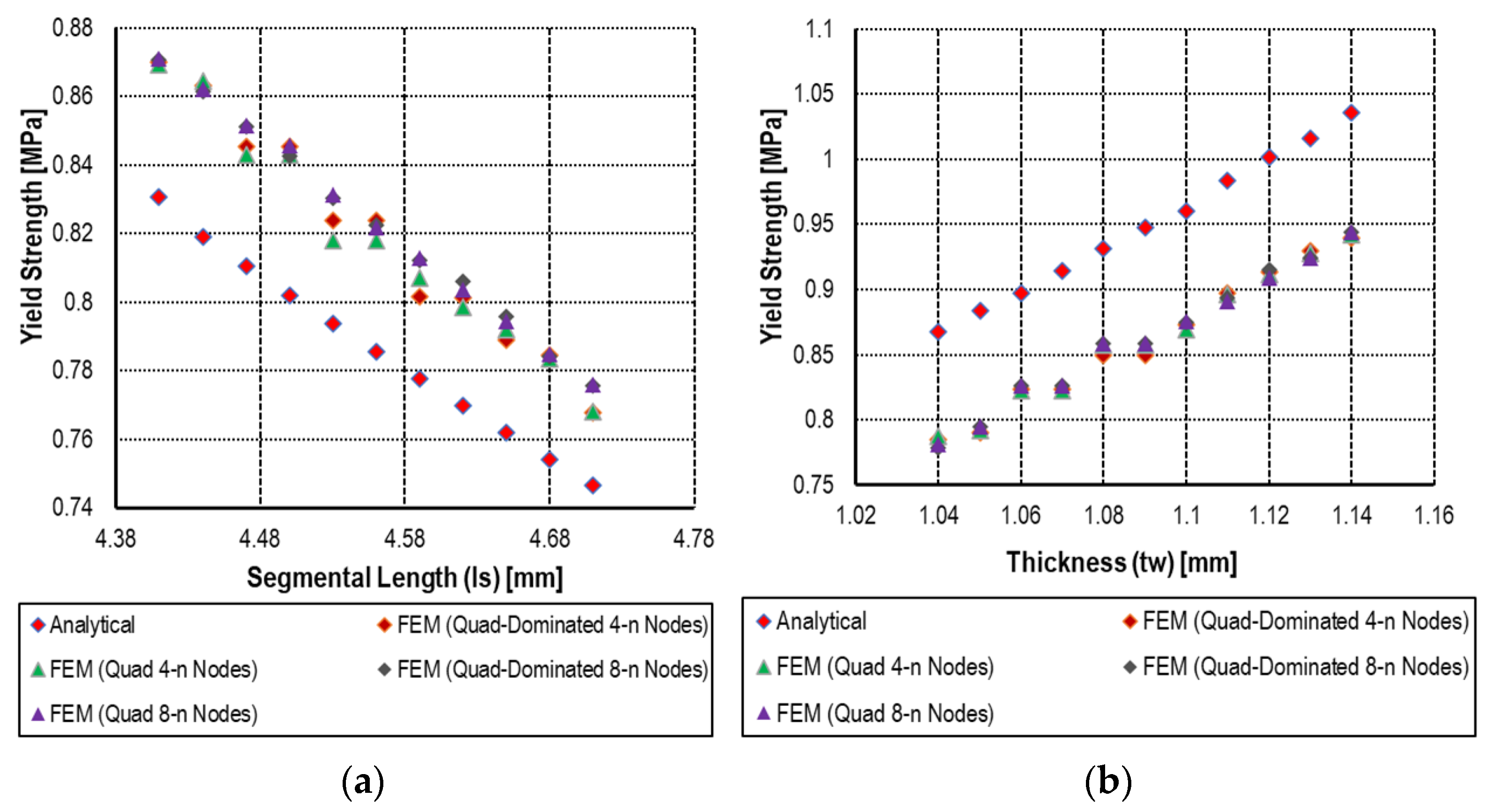

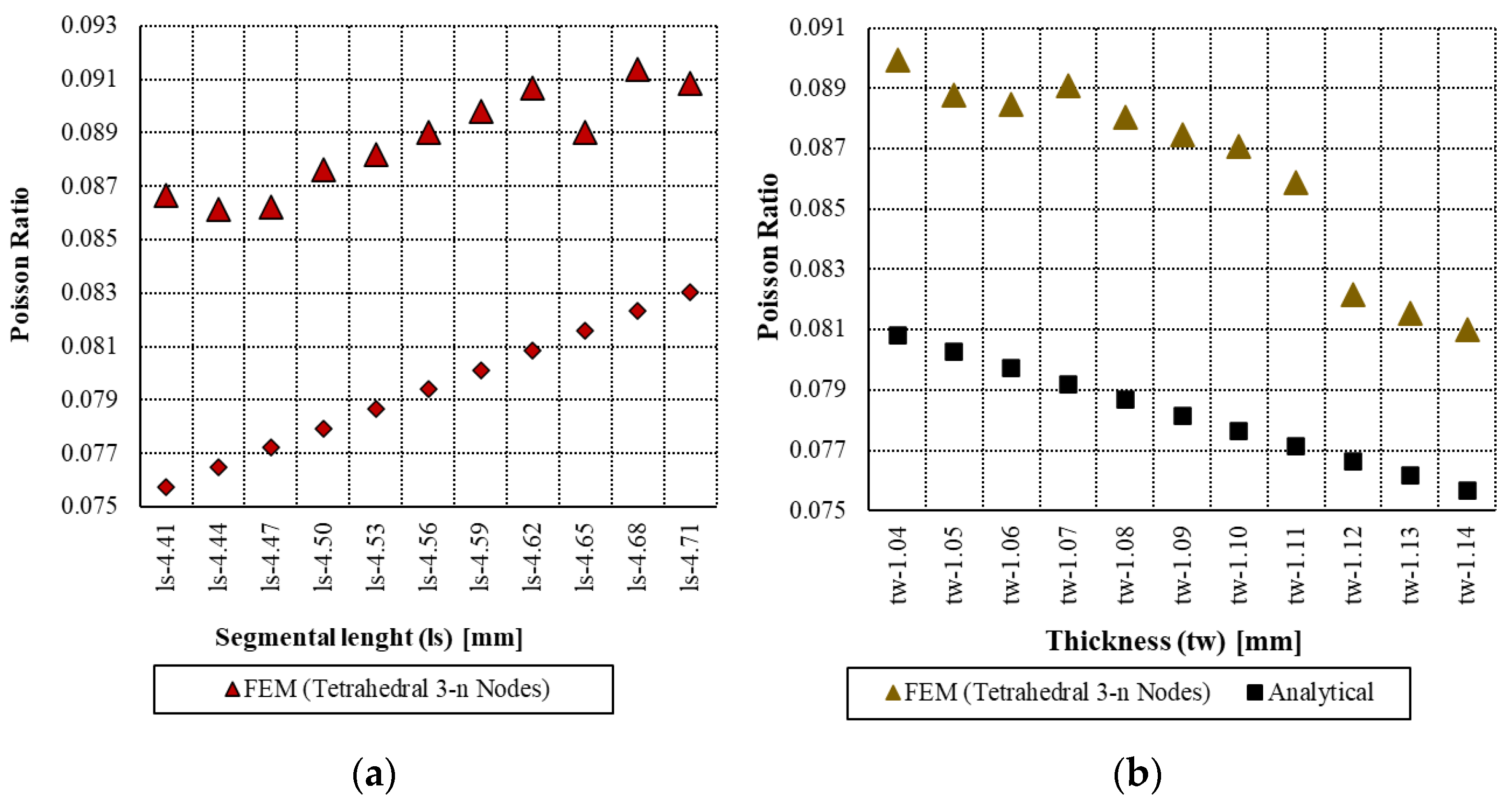

4. Computer Simulation

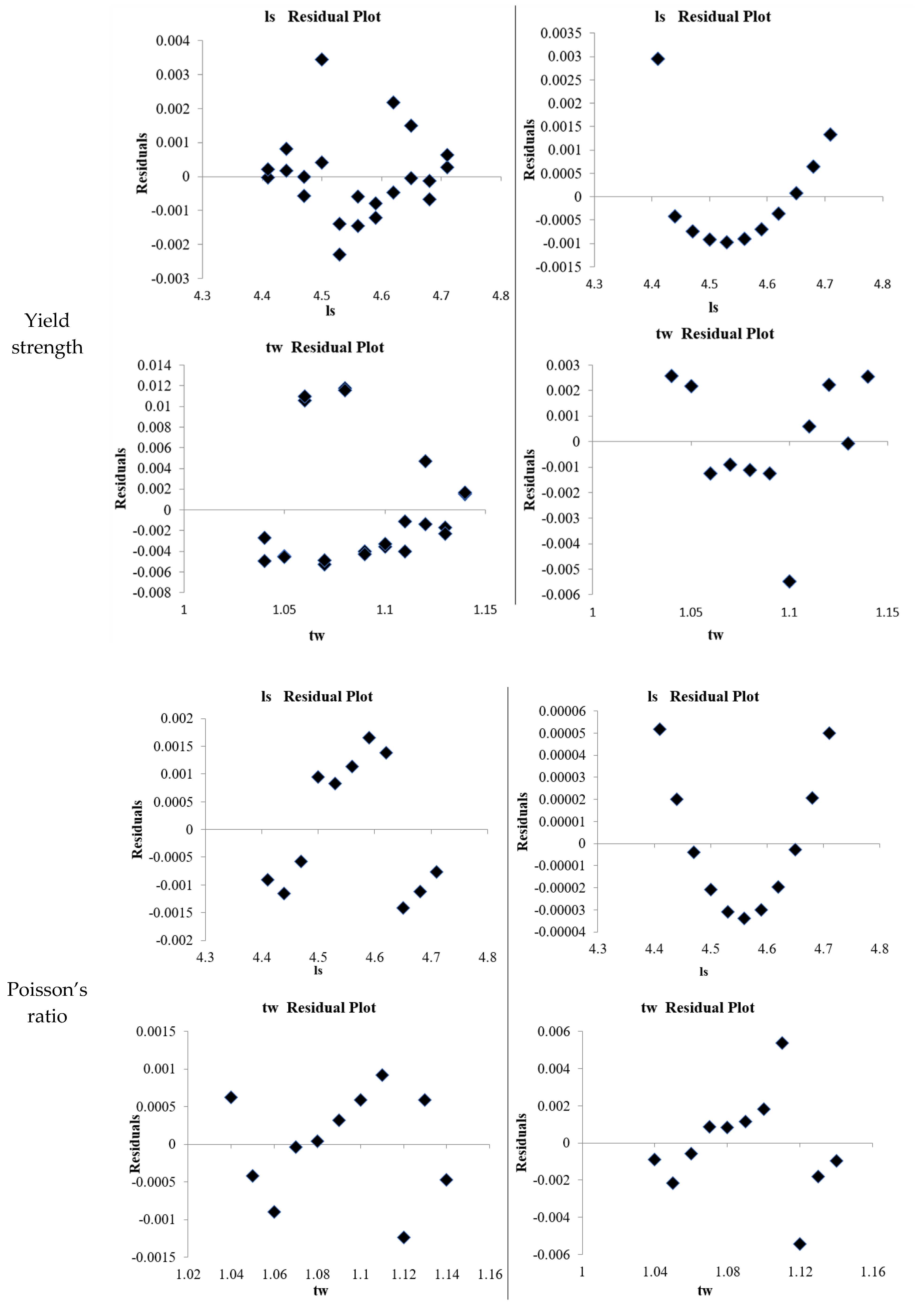

5. Development of Polynomial Model

6. Uncertainty Quantification

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model Description | Elastic Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation on (Em) | Variation on (ls) | ||||||

| Mesh | Nodes | Mesh | Nodes | ||||

| Elements | Types | No. | Elements | Types | No. | ||

| Case-1 | Case-1-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 932 | CPS8R | 3026 |

| Case-1-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 897 34 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2989 | |

| Case-2 | Case-2-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 780 | CPS8R | 2570 |

| Case-2-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 757 18 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2537 | |

| Case-3 | Case-3-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 771 | CPS8R | 2543 |

| Case-3-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 736 20 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2478 | |

| Case-4 | Case-4-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 747 | CPS8R | 2471 |

| Case-4-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 721 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2421 | |

| Case-5 | Case-5-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 741 | CPS8R | 2453 |

| Case-5-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 704 20 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2382 | |

| Case-6 | Case-6-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 741 | CPS8R | 2453 |

| Case-6-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 706 10 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2368 | |

| Case-7 | Case-7-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 698 | CPS8R | 2324 |

| Case-7-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 666 20 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2268 | |

| Case-8 | Case-8-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 706 | CPS8R | 2348 |

| Case-8-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 656 26 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2250 | |

| Case-9 | Case-9-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 704 | CPS8R | 821 |

| Case-9-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 674 16 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2288 | |

| Case-10 | Case-10-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 705 | CPS8R | 2351 |

| Case-10-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 668 16 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2272 | |

| Case-11 | Case-11-8N-Q | 756 | CPS8R | 2498 | 703 | CPS8R | 2345 |

| Case-11-8N-QD | 726 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2436 | 666 24 | CPS8R CPS6M | 2282 | |

| Model Description | Plastic Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation on (tw) | Variation on (ls) | ||||||

| Mesh | Nodes | Mesh | Nodes | ||||

| Elements | Types | No. | Elements | Types | No. | ||

| Case-1 | Case-1-8N-Q | 421 | CPS8R | 1467 | 413 | CPS8R | 1443 |

| Case-1-8N-QD | 394 20 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1426 | 408 4 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1436 | |

| Case-2 | Case-2-8N-Q | 423 | CPS8R | 1473 | 436 | CPS8R | 1512 |

| Case-2-8N-QD | 140 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1458 | 417 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1479 | |

| Case-3 | Case-3-8N-Q | 417 | CPS8R | 1455 | 418 | CPS8R | 1458 |

| Case-3-8N-QD | 403 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1441 | 402 10 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1430 | |

| Case-4 | Case-4-8N-Q | 416 | CPS8R | 1452 | 441 | CPS8R | 1527 |

| Case-4-8N-QD | 387 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1393 | 420 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1488 | |

| Case-5 | Case-5-8N-Q | 408 | CPS8R | 1428 | 407 | CPS8R | 1425 |

| Case-5-8N-QD | 386 20 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1402 | 386 16 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1394 | |

| Case-6 | Case-6-8N-Q | 414 | CPS8R | 1446 | 423 | CPS8R | 1473 |

| Case-6-8N-QD | 391 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1405 | 396 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1416 | |

| Case-7 | Case-7-8N-Q | 420 | CPS8R | 1464 | 408 | CPS8R | 1428 |

| Case-7-8N-QD | 404 8 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1432 | 388 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1392 | |

| Case-8 | Case-8-8N-Q | 446 | CPS8R | 1542 | 441 | CPS8R | 1533 |

| Case-8-8N-QD | 413 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1467 | 415 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1479 | |

| Case-9 | Case-9-8N-Q | 422 | CPS8R | 1470 | 445 | CPS8R | 1547 |

| Case-9-8N-QD | 402 22 | CPS8R CPS6M | 515 | 419 10 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1489 | |

| Case-10 | Case-10-8N-Q | 425 | CPS8R | 1479 | 451 | CPS8R | 1569 |

| Case-10-8N-QD | 401 12 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1431 | 439 6 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1545 | |

| Case-11 | Case-11-8N-Q | 418 | CPS8R | 1458 | 448 | CPS8R | 1560 |

| Case-11-8N-QD | 408 14 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1456 | 440 6 | CPS8R CPS6M | 1548 | |

| Model Description | Poisson’s Ratio Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation on (tw) | Variation on (ls) | ||||||

| Mesh | Nodes | Mesh | Nodes | ||||

| Elements | Types | No. | Elements | Types | No. | ||

| Case-1 | Case-1-3N-T | 796 | CPS3 | 500 | 816 | CPS3 | 510 |

| Case-2 | Case-2-3N-T | 804 | CPS3 | 504 | 812 | CPS3 | 508 |

| Case-3 | Case-3-3N-T | 804 | CPS3 | 504 | 812 | CPS3 | 508 |

| Case-4 | Case-4-3N-T | 812 | CPS3 | 508 | 810 | CPS3 | 507 |

| Case-5 | Case-5-3N-T | 812 | CPS3 | 508 | 812 | CPS3 | 508 |

| Case-6 | Case-6-3N-T | 816 | CPS3 | 510 | 810 | CPS3 | 507 |

| Case-7 | Case-7-3N-T | 812 | CPS3 | 508 | 812 | CPS3 | 508 |

| Case-8 | Case-8-3N-T | 818 | CPS3 | 511 | 840 | CPS3 | 525 |

| Case-9 | Case-9-3N-T | 810 | CPS3 | 507 | 842 | CPS3 | 526 |

| Case-10 | Case-10-3N-T | 810 | CPS3 | 507 | 868 | CPS3 | 542 |

| Case-11 | Case-11-3N-T | 812 | CPS3 | 508 | 872 | CPS3 | 544 |

Appendix B

| Effective Parameters | Standard Error | t Stat | p-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | Lower 99.0% | Upper 99.0% | ||

| Young’s Modulus w.r.t () | Numerically | Intercept | 0.005356153 | 9.92399 × 10−5 | 0.059921801 | −0.01117 | 0.011173271 | −0.015239543 | 0.015240606 |

| 7.7605 × 10−5 | 1080.210138 | 3.85534 × 10−49 | 0.083668 | 0.083991624 | 0.08360893 | 0.084050556 | |||

| Analytically | Intercept | 6.70493 × 10−15 | 192198474.2 | 3.8133 × 10−154 | 1.29 × 10−6 | 1.28868 × 10−6 | 1.28868 × 10−6 | 1.28868 × 10−6 | |

| 9.71473 × 10−17 | 9.63963 × 10+14 | 3.7592 × 10−288 | 0.093646 | 0.093646399 | 0.093646399 | 0.093646399 | |||

| Young’s Modulus w.r.t () | Numerically | Intercept | 0.060638964 | 255.1613197 | 1.3144 × 10−36 | 15.34623 | 15.59920885 | 15.30017973 | 15.64525664 |

| 0.013295142 | −160.961054 | 1.31427 × 10−32 | −2.16773 | −2.11226682 | −2.177829194 | −2.10217081 | |||

| Analytically | Intercept | 0.023958893 | 750.4155359 | 5.6249 × 10−46 | 17.92915 | 18.02910283 | 17.91095427 | 18.04729664 | |

| 0.005253006 | −487.911067 | 3.08416 × 10−42 | −2.57396 | −2.55204242 | −2.577946588 | −2.54805341 | |||

| Yield strength w.r.t () | Numerically | Intercept | 0.013154723 | 172.8301002 | 3.17056 × 10−33 | 2.246092 | 2.300972401 | 2.236102473 | 2.310961786 |

| 0.002884184 | −110.282053 | 2.50836 × 10−29 | −0.32409 | −0.31205739 | −0.326280172 | −0.30986721 | |||

| Analytically | Intercept | 0.012507849 | 163.1960621 | 9.97684 × 10−33 | 2.015141 | 2.06732257 | 2.005642576 | 2.076820734 | |

| 0.002742356 | −100.333317 | 1.65641 × 10−28 | −0.28087 | −0.26942921 | −0.282952595 | −0.26734673 | |||

| Yield strength w.r.t () | Numerically | Intercept | 0.044771257 | −19.2876476 | 2.15579 × 10−14 | −0.95692 | −0.77014103 | −0.99092167 | −0.7361428 |

| 0.041057273 | 38.57814888 | 2.97942 × 10−20 | 1.49827 | 1.669557567 | 1.467091706 | 1.700735486 | |||

| Analytically | Intercept | 0.017766168 | −49.962198 | 1.77986 × 10−22 | −0.9247 | −0.85057723 | −0.938187591 | −0.83708602 | |

| 0.016292382 | 103.426271 | 9.0352 × 10−29 | 1.651075 | 1.719045601 | 1.638702928 | 1.731417649 | |||

| Poisson’s ratio w.r.t () | Numerically | Intercept | 0.018024544 | 12.44637904 | 5.63782 × 10−7 | 0.183566 | 0.265114651 | 0.165763498 | 0.282917103 |

| ls | 0.003951896 | −7.65939614 | 3.12819 × 10−5 | −0.03921 | −0.02132933 | −0.043112145 | −0.01742612 | ||

| Analytically | Intercept | 0.000479388 | 326.2699766 | 1.21486 × 10−19 | 0.155325 | 0.157494365 | 0.154851982 | 0.157967846 | |

| 0.000105106 | −163.197846 | 6.19214 × 10−17 | −0.01739 | −0.01691534 | −0.017494684 | −0.01681153 | |||

| Poisson’s ratio w.r.t () | Numerically | Intercept | 0.00758042 | 4.125197252 | 0.002577881 | 0.014123 | 0.048418826 | 0.006635609 | 0.055905843 |

| 0.006951588 | 7.577620388 | 3.405 × 10−5 | 0.036951 | 0.068402084 | 0.030084979 | 0.075268018 | |||

| Analytically | Intercept | 5.46375 × 10−17 | 0.253997414 | 0.805205267 | −1.1 × 10−16 | 1.37476 × 10−16 | −1.63685 × 10−16 | 1.91441 × 10−16 | |

| 5.01051 × 10−17 | 1.4539 × 10+15 | 1.7541 × 10−133 | 0.072848 | 0.072847682 | 0.072847682 | 0.072847682 | |||

References

- Montazeri, A.; Saeedi, A.; Bahmanpour, E.; Safarabadi, M. Heterogeneous hexagonal honeycombs with nature-inspired defect channels under in-plane crushing. Mater. Lett. 2024, 366, 136564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.; Jardin, R.; Pereira, A.; de Sousa, R.A. Comparing the mechanical performance of synthetic and natural cellular materials. Mater. Des. 2015, 82, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Pan, Z.; Wang, C.; Dong, Y.; Ou, Y. Composition, structure and mechanical properties of several natural cellular materials. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2007, 52, 2903–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Kamiński, M. Review Study on Mechanical Properties of Cellular Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaedler, T.A.; Carter, W.B. Architected Cellular Materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2016, 46, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahatme, C.; Giri, J.; Mohammad, F.; Ali, M.S.; Sathish, T.; Sunheriya, N.; Chadge, R. Experimental and numerical investigation of PLA based different lattice topologies and unit cell configurations for additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 136, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Kamiński, M.; Ardakani, S.S. Uncertainty quantification of effective mechanical characteristics of hexagonal cellular material. Mech. Res. Commun. 2025, 144, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, F.N.; Iovenitti, P.; Masood, S.H.; Nikzad, M. Cell geometry effect on in-plane energy absorption of periodic honeycomb structures. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 94, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, F.; Blain, S.; Lew, T.; Perrott, D.; Ruzzene, M.; Yates, J. Elastic buckling of hexagonal chiral cell honeycombs. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2007, 38, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swellam, M.; Yi, S.; Ahmad, M.F.; Huber, L.M. Mechanical properties of cellular materials. I. Linear analysis of hexagonal honeycombs. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 63, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, J.N.; Gatt, R.; Ravirala, N.; Alderson, A.; Evans, K. Negative Poisson’s ratios in cellular foam materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 423, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, A.A.; Sadeghi, M. The effects of foam filling on compressive response of hexagonal cell aluminum honeycombs under axial loading-experimental study. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 1216–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.J.; Silberschmidt, V.V. Numerical modelling of low-density cellular materials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Han, Y.; Lu, J. Design and optimization of lattice structures: A review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D.J.; Tawfick, S.; King, W.P. Mechanical properties of hexagonal lattice structures fabricated using continuous liquid interface production additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 25, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; van Egmond, D.A.; Abu Samk, K.; Erb, U.; Wilkinson, D.; Embury, D.; Zurob, H. The design of “Grain Boundary Engineered” architected cellular materials: The role of 5–7 defects in hexagonal honeycombs. Acta Mater. 2022, 243, 118513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttakul, P.; Vo, D.; Fongsamootr, T.; Nanakorn, P. Closed-form effective out-of-plane elastic properties of regular and non-regular hexagonal lattice plates. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 32, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, J.; Li, K.; Deshpande, V.; Fleck, N. The in-plane, elastic-plastic response of a filled hexagonal honeycomb at finite strain. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2022, 168, 105047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M. Design sensitivity analysis for the homogenized elasticity tensor of a polymer filled with rubber particles. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2014, 51, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, B.; Hinton, E. A review of homogenization and topology optimization II—Analytical and numerical solution of homogenization equations. Comput. Struct. 1998, 69, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabnejad, S.; Pasini, D. Mechanical properties of lattice materials via asymptotic homogenization and comparison with alternative homogenization methods. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2013, 77, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanparast, R.; Rafiee, R. Developing a homogenization approach for estimation of in-plan effective elastic moduli of hexagonal honeycombs. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elements 2020, 117, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacigalupo, A.; Gambarotta, L. Homogenization of periodic hexa- and tetrachiral cellular solids. Compos. Struct. 2014, 116, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Jin, F.; Fang, D. Mechanical properties of hierarchical cellular materials. Part I: Analysis. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 3380–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohe, J.; Beschorner, C.; Becker, W. Effective elastic properties of hexagonal and quadrilateral grid structures. Compos. Struct. 1999, 46, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehbaghi, H.; Farrokhabadi, A. Analytical, experimental, and numerical evaluation of mechanical properties of a new unit cell with hyperbolic shear deformable beam theory. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 31, 6419–6433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Fracture analysis of cellular materials: A strain gradient model. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1998, 46, 789–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.; Gao, X.-L.; Li, K. A strain energy-based homogenization method for 2-D and 3-D cellular materials using the micropolar elasticity theory. Compos. Struct. 2021, 265, 113594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Johnston, S.; Shang, S.; Anderson, T. Calculated strain energy of hexagonal epitaxial thin films. J. Cryst. Growth 2002, 240, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Song, T.; Li, C.; Das, R.; Gu, J.; Qian, M. The Gibson-Ashby model for additively manufactured metal lattice materials: Its theoretical basis, limitations and new insights from remedies. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2023, 27, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q. Effect of entrapped gas on the dynamic compressive behaviour of cellular solids. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2015, 63, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahani, M.; Safarian, S.; Maghsoud, Z. Multiscale asymptotic homogenization analysis of epoxy-based composites reinforced with different hexagonal nanosheets. Compos. Struct. 2019, 222, 110929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakareyar, P.; ElSayed, M.S.A.; El Ella, H.A.; Matida, E. Effective Mechanical Properties of Periodic Cellular Solids with Generic Bravais Lattice Symmetry via Asymptotic Homogenization. Materials 2023, 16, 7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.; Garboczi, E. Elastic moduli of model random three-dimensional closed-cell cellular solids. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-D.; Noels, L. Computational homogenization of cellular materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2014, 51, 2183–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iltchev, A.; Marcadon, V.; Kruch, S.; Forest, S. Computational homogenisation of periodic cellular materials: Application to structural modelling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 93, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, S.J.; Brown, J.A.; Ernst, C.D.; Lim, H.; Long, K.N. Hexahedral Mesh Generation for Computational Materials Modeling. Procedia Eng. 2017, 203, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroni, N.; Campen, M.; Sheffer, A.; Cherchi, G.; Bommes, D.; Gao, X.; Scateni, R.; Ledoux, F.; Remacle, J.; Livesu, M. Hex-Mesh Generation and Processing: A Survey. ACM Trans. Graph. 2022, 42, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Gao, X.-L.; Subhash, G. Effects of cell shape and cell wall thickness variations on the elastic properties of two-dimensional cellular solids. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2005, 42, 1777–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S. The in-plane mechanical properties of highly compressible and stretchable 2D lattices. Compos. Struct. 2021, 272, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipperman, F.; Ryvkin, M.; Fuchs, M.B. Fracture toughness of two-dimensional cellular material with periodic microstructure. Int. J. Fract. 2007, 146, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozrikidis, C. Mechanics of hexagonal atomic lattices. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2008, 45, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, T.; Mahata, A.; Adhikari, S.; Zaeem, M.A. Effective elastic properties of two dimensional multiplanar hexagonal nanostructures. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, J.; Leng, J.; Liu, Y. In-plane mechanical properties of a novel cellular structure for morphing applications. Compos. Struct. 2022, 305, 116482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huo, Y.; Meng, K.; Zhou, W.; Yang, J.; Nan, Z. Fatigue failure analysis of platform screen doors under subway aerodynamic loads using finite element modeling. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 174, 109502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Nan, Z.; Huo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, P.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, Y.; Meng, K. Design, characterisation, and crushing performance of hexagonal-quadrilateral lattice-filled steel/CFRP hybrid structures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 304, 112631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Guo, W.; Yang, L.; Yang, C.; Zhou, S. Crashworthiness analysis and multi-objective optimization of a novel metal/CFRP hybrid friction structures. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2024, 67, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Aznar, M.T. Condensed-Matter and Materials Physics: Basic Research for Tomorrow’s Technology. Eur. J. Phys. 2000, 21, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaro, F. Estimation of the effective properties of two-dimensional cellular materials: A review. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 2018, 8, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, O.; Nobile, F.; Schillings, C.; Sullivan, T. Uncertainty Quantification. Oberwolfach Rep. 2020, 16, 695–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorguluarslan, R.M.; Choi, S.-K.; Saldana, C.J. Uncertainty quantification and validation of 3D lattice scaffolds for computer-aided biomedical applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 71, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Ma, Z.; Hulbert, G.M. Elastic analysis of auxetic cellular structure consisting of re-entrant hexagonal cells using a strain-based expansion homogenization method. Mater. Des. 2018, 160, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M. Homogenization-based finite element analysis of unidirectional composites by classical and multiresolutional techniques. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2005, 194, 2147–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M.; Szafran, J. Perturbation-based stochastic finite element analysis of the interface defects in composites via Response Function Method. Compos. Struct. 2013, 97, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M. The Stochastic Perturbation Method for Computational Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M. Generalized stochastic perturbation technique in engineering computations. Math. Comput. Model. 2010, 51, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Rao, B.N. A perturbation method for stochastic meshless analysis in elastostatics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2001, 50, 1969–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M. On generalized stochastic perturbation-based finite element method. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 2005, 22, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M. Generalized perturbation-based stochastic finite element method in elastostatics. Comput. Struct. 2007, 85, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björck, Å. Numerical Methods for Least Squares Problems; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regression Statistics | Multiple R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Standard Error | Observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus w.r.t () | Numerically | 0.999991 | 0.99998 | 0.999982 | 0.000575534 | 22 |

| Analytically | 0.999991 | 0.99999 | 0.998982 | 7.20464 × 10−16 | 22 | |

| Young’s Modulus w.r.t () | Numerically | 0.999614 | 0.99923 | 0.999190 | 0.005915965 | 22 |

| Analytically | 0.999958 | 0.99992 | 0.999912 | 0.00233744 | 22 | |

| Yield strength w.r.t () | Numerically | 0.999958 | 0.99992 | 0.999912 | 0.00233744 | 22 |

| Analytically | 0.999008 | 0.99802 | 0.997918 | 0.001220271 | 22 | |

| Yield strength w.r.t () | Numerically | 0.993348 | 0.98674 | 0.986077 | 0.006089778 | 22 |

| Analytically | 0.999066 | 0.99813 | 0.998040 | 0.002416551 | 22 | |

| Poisson’s ratio w.r.t () | Numerically | 0.931125 | 0.86699 | 0.852216 | 0.001243435 | 11 |

| Analytically | 0.999831 | 0.99966 | 0.999625 | 3.30709 × 10−5 | 11 | |

| Poisson’s ratio w.r.t () | Numerically | 0.929785 | 0.8645 | 0.849444 | 0.000729089 | 11 |

| Analytically | 0.935685 | 0.87256 | 0.978552 | 5.25507 × 10−18 | 11 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqbal, S.; Kamiński, M. Uncertainty Quantification of the Mechanical Properties of 2D Hexagonal Cellular Solid by Analytical and Finite Element Method Approach. Materials 2025, 18, 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204792

Iqbal S, Kamiński M. Uncertainty Quantification of the Mechanical Properties of 2D Hexagonal Cellular Solid by Analytical and Finite Element Method Approach. Materials. 2025; 18(20):4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204792

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqbal, Safdar, and Marcin Kamiński. 2025. "Uncertainty Quantification of the Mechanical Properties of 2D Hexagonal Cellular Solid by Analytical and Finite Element Method Approach" Materials 18, no. 20: 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204792

APA StyleIqbal, S., & Kamiński, M. (2025). Uncertainty Quantification of the Mechanical Properties of 2D Hexagonal Cellular Solid by Analytical and Finite Element Method Approach. Materials, 18(20), 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204792