1. Introduction

Most waste generated by the textile industry [

1], is composed of organic and inorganic compounds generated during textile dyeing [

2,

3]. These compounds are difficult to eliminate by traditional effluent treatment processes [

2,

4,

5,

6], due to the excessive content of suspended solids, and the presence of surfactants, detergents, and dyes [

7]. The textile sector is also characterized by high competition, stimulated by economic, consumerism, and globalization factors, seeking improvements to reduce its expenses and costs, maintaining the quality of the product and contributing to sustainability [

8].

Among the materials used by the textile industry, polyester is considered the most consumed synthetic fiber in the world, being able to integrate different types of products that unfold in the textile chain [

9]. However, the dyeing of polyester fibers with dispersed dyes is a complex process as it resembles a solid-on-solid dispersion and encounters considerable difficulties due to the absence of reactive sites, which gives this type of fiber a hydrophobic character [

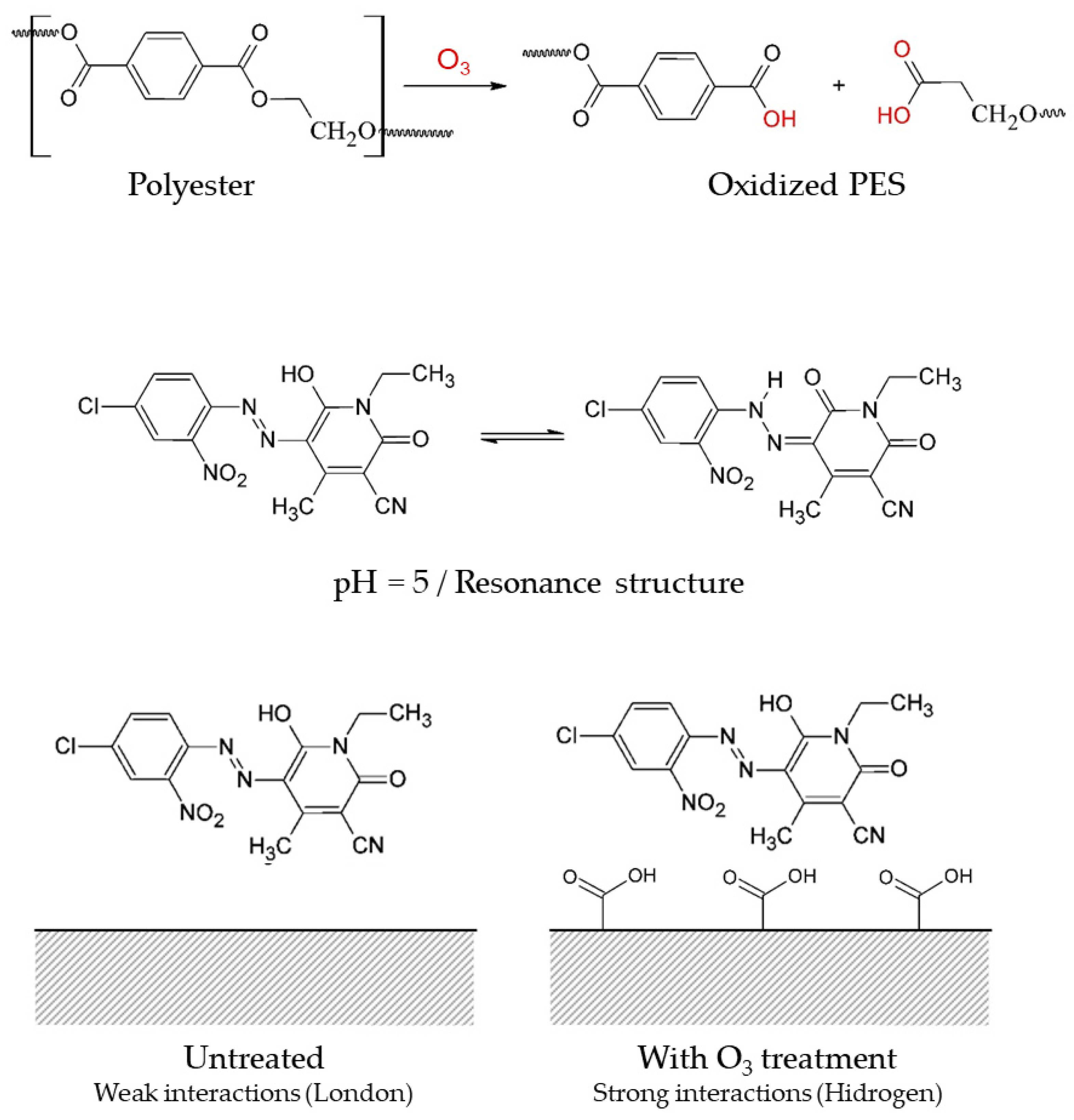

10]. In this context, it is possible to make a modification on the polyester fiber in order to improve its hydrophilicity and, consequently, facilitate the absorption of the dyes.

Many publications have shown the difficulty for treatment of textile effluents, pointing out to the excess content of solids present, in addition of surfactants, detergents, and dyes [

3,

6,

9,

10]. An alternative to facilitate treatment is to reduce the consumption of dyes without losing the characteristics of the article, especially the coloring. Thus, surface modification processes can create reactive sites and increase the adsorption of dye by the fiber hence reducing the amount of pollutants in the effluents. In the search for new technologies to improve the dyeing process, the use of ozone gas (O

3) has emerged as a viable alternative [

11], as ozone treatments have the capability to improve the wettability of the polyester fibers [

12,

13], and to use less water during the dyeing process [

9,

14,

15,

16,

17].

According to Wakida et al. [

18], ozone treatments alter both, the fiber’s surface and its internal structure [

19]. Several authors [

10,

17,

20] have also found that ozone treatment has the potential of lower energy consumption during the processing of polyester fibers.

Thus, it is expected that from the use of polyester surface modification with ozone, it will be possible to obtain a more hydrophilic fabric, making it possible to have a dyeing process with less amounts of dye. The absorption of dyes into porous media comprises several steps. Initially, there is mass transfer from the bulk liquid media (dyeing bath), through the boundary layer to the external surface of the fiber, followed by diffusional dye transport inside the fiber.

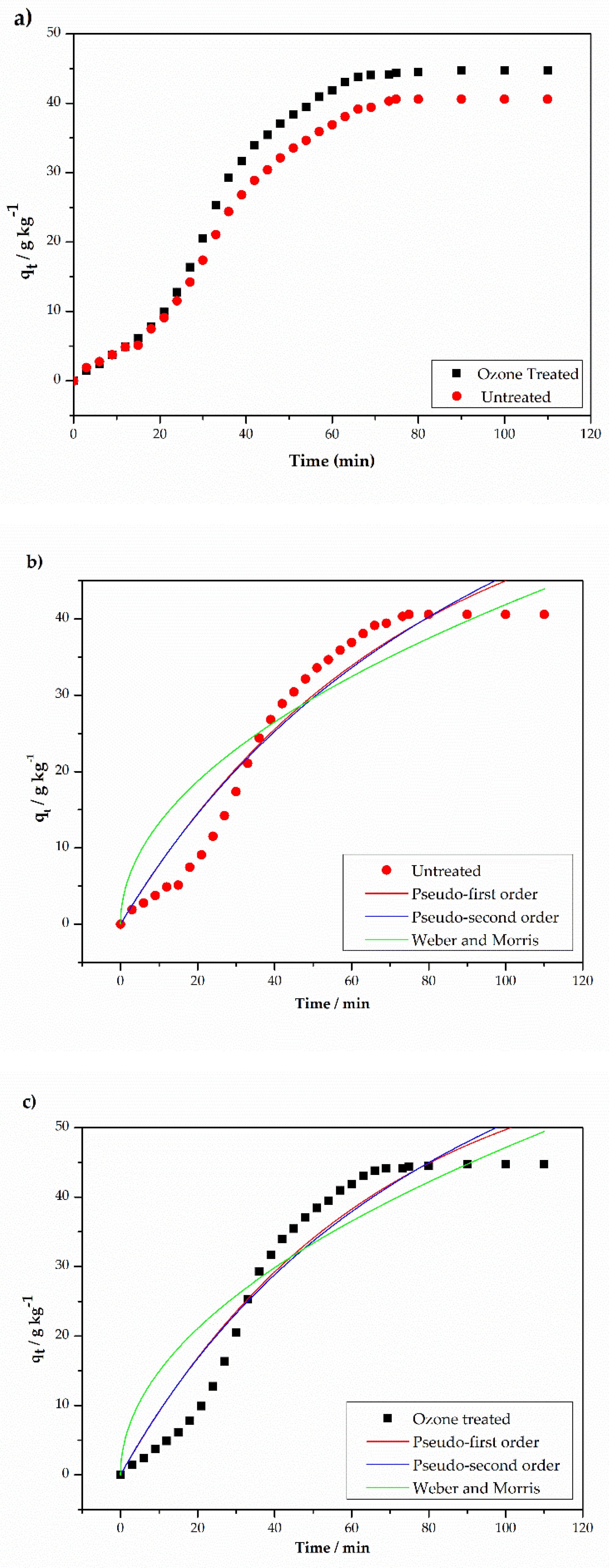

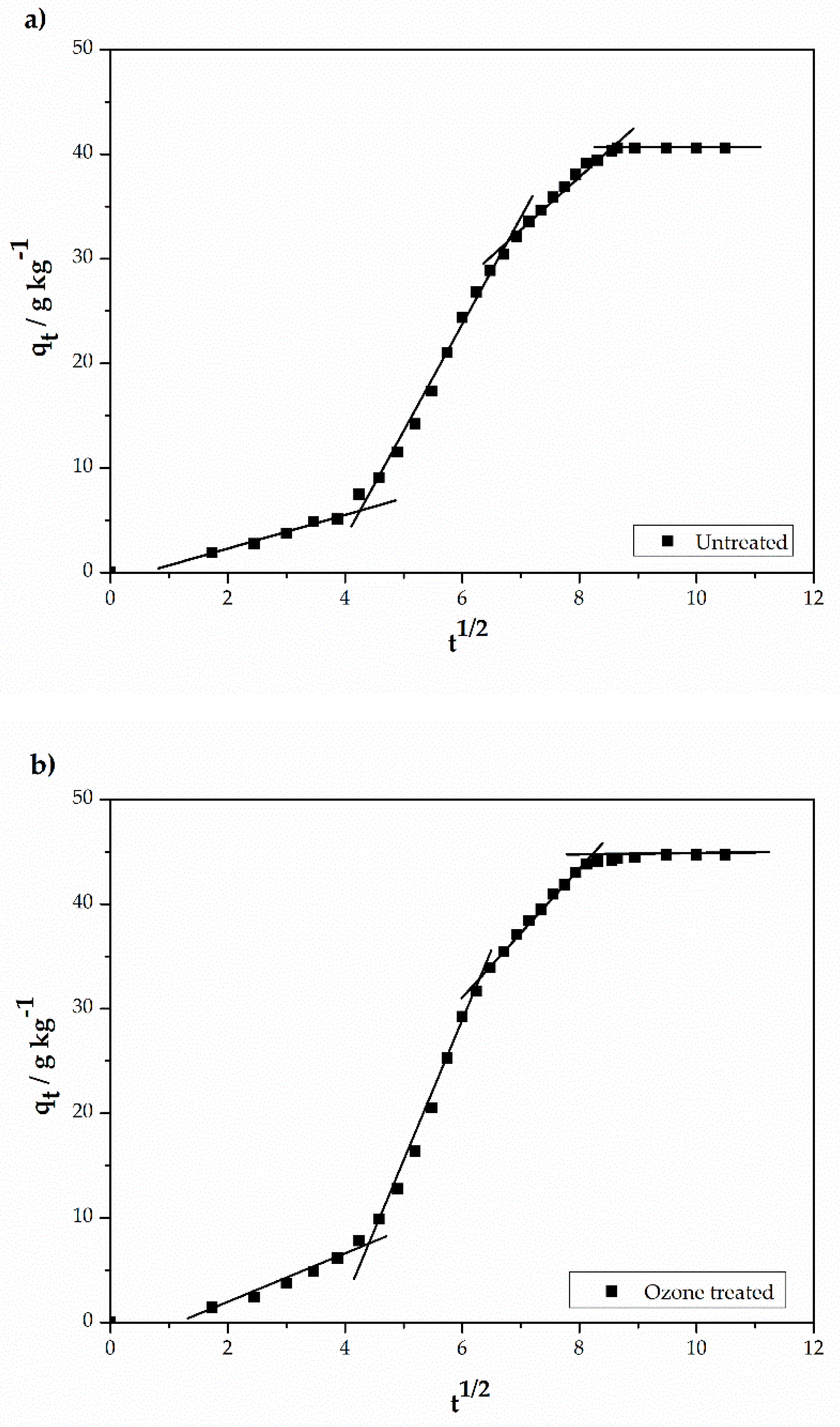

Kinetic models describing this absorption phenomena use two approaches: (i) Models based on adsorption reaction models such as the pseudo-first order (PFO) [

21] and pseudo second order (PSO) [

22], models which assume that the adsorption process is exclusively controlled by the adsorption rate of the solute on the surface of the adsorbent, and neglect intraparticle diffusion and external mass transfer; (ii) intra-particle diffusion models, which assume that equilibrium between fluid and surface concentrations of dye, are instantaneously reached inside the pores [

23], therefore simplifying the dyeing process to a simple mass transfer process.

In this paper, we report on the use of ozone gas to modify surface of polyester fibers, and the effect of this ozone pre-treatment on the dyeing of these fibers using disperse dyes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polyester plain weave 100% (160 ± 5 gm−2), 20 Tex warp yarn (24 yarns/cm), 6.25 Tex weft yarn (24 yarns/cm) were provided by the Polytechnic University of Catalunya (UPC), C.I. Disperse Yellow 211 dye was provided by Golden Technology (São José dos Campos, Brazil). Blue Turquoise Solae GLL, (NH4)2SO4, and sodium bisulphite, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Polyester Modification by O3

Ozone modification was performed using a UV-SURF X4 (UV-Consulting Peschl España, Spain) equipment, 17 W power, and an emission spectrum varying from 185 to 254 nm. Polyester samples of 10 cm × 20 cm were inserted into the equipment’s chamber and exposed for 20, 30, and 45 min to ozone produced by low-pressure mercury lamps.

2.3. Evaluation of Modified Fabric

FTIR-ATR spectroscopy was performed using a Frontier—Perkin Elmer, 64 scans with a resolution of 1 cm−1 using attenuated total reflectance (ATR) in the range between 650 and 4000 cm−1. Raman spectroscopy measurements were carried out using an Alpha 300 R spectrometer—Witec, containing a double monochromator, a 532 nm laser and a microscope with a 20× objective lens; 532 nm laser excitation lines were used. The laser power on the surface of the samples was approximately 7.5 mW cm−2 with an integration time of 3 s and a total of 10 scans. Zeta potential measurements were obtained in a Zetasizer Nano from Malvern Instruments. The readings were performed in triplicate on both sides of each sample at pH 6 and 25 °C. For the capillarity tests, a method was adapted from standard JIS L 1907—(Testing methods for water absorbency of textiles). Samples were cut into 20 × 2.5 cm strips and 1 cm of this strip was immersed in a solution containing a reactive dye Blue Turquoise Solae GLL. After 10 min, the height of the dye absorbed by capillarity was measured.

2.4. Dyeing

We perform the exhaustion dyeing experiments in a Mathis ALT-1-B mug machine, with a bath ratio of 1:30 (m:v) and 5 g of fabric sample. Total of 2 g·L−1 of ammonium sulfate (pH control 5–5.5), 1.5 g·L−1 of non-ionic wetting agent, and 1% of w (over fiber weight) of C.I. Dispersed yellow 211 dye were added at 130 °C for 30 min. At the end of the process, reductive washing was performed using a solution containing 2 g·L−1 of sodium hydrosulfite and 3 g·L−1 of sodium hydroxide (50° BÉ) at 80 °C for 20 min.

2.5. Evaluation of Polyester Fabrics after Dyeing

2.5.1. Color Rating

The color evaluation of the samples was performed using a DataColor spectrophotometer, spectraflesh model SF650X, and the i7 Delta Color software. The evaluation was performed under illuminant D65, which generates trichromatic coordinates, arranged in the CIE L*a*b* space. The color difference between the treated and untreated samples was calculated using ΔE and ΔEcmc.

The color strength was calculated using Equation (1) and the percentage of dye reduction was obtained via Equation (2).

where

K/

S is assumed to represent the color intensity.

For Equation (2), in order to obtain the same color strength, if Q% > 0, it indicates that the amount of dye required must be increased and for values of Q% < 0, the amount of dye must be reduced.

2.5.2. Morphological Analysis

The surface of the fabric samples was imaged using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM Quanta 250) with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, Spot 3.5, and magnification levels of 1500 and 4000×.

2.5.3. Fastness to Rubbing Tests

The color fastness to rubbing test was carried out on a KIMAK crock meter (Kimak, Brazil), under dry and wet conditions. The specimens were compared to the gray scale (BSI Standards) in accordance to the Test for colour fastness—Part X12: Colour fastness to rubbing, ISO 105-X12 [

24].

2.5.4. Dyeing Kinetics

Kinetic data were obtained using a Smart Liquor equipment (Mathis

®). During the dyeing process, the equipment measures the absorbance of the bath and generates dye depletion curves as a function of time at a rate of 6 scans per minute. These data were used to study the kinetics of the process by fitting to three kinetic models: pseudo-first order [

21], pseudo-second order [

22], and Weber and Morris intraparticle model (WM) [

25].

4. Conclusions

We report on the modification of polyester fabrics with ozone and the dyeing of the modified fabrics with the C.I. Disperse Yellow 211 dye. We observed molecular and topographical changes in the polyester fabric after ozone exposure. While FT-IR and Raman spectra do not reveal the appearance of extensive amounts of new functional groups on the treated fabrics, Raman spectra shows that the intensity of the non-aromatic bands decreases with oxidation and oxidized groups are created by ozonolysis, with a significant increase in the intensity of peaks related to the hydrophilic bonds. Friction fastness tests shows that upon 20 min of ozone exposure, the specimens have a score of 5 for both tests, dry and wet. Kinetic data show that dye adsorption process can be explained by a three-steps Weber and Morris intraparcicle diffusion model. The amount of dye adsorption at equilibrium is higher by a 10.74% for the untreated samples confirming that ozone treatment may be an efficient means to reduce the amount of dye used. We assume that this increase is due to an increase in hydrogen bond interactions after ozone treatment. To emphasize the nature of structural changes and the different possibilities of interaction between dye and fabric, we will use aromatic dyes, without hydrogen bond probability, for future work to improve the understanding of this process. This work shows that ozone treatment is a good way to reduce inputs in the dyeing processes and also wastewater treatment expenses, thus, reducing the environmental impacts of the textile industry as well as potentially decreasing the processing costs.