Bioactivity of Bioceramic Materials Used in the Dentin-Pulp Complex Therapy: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.2.1. Sources of Information

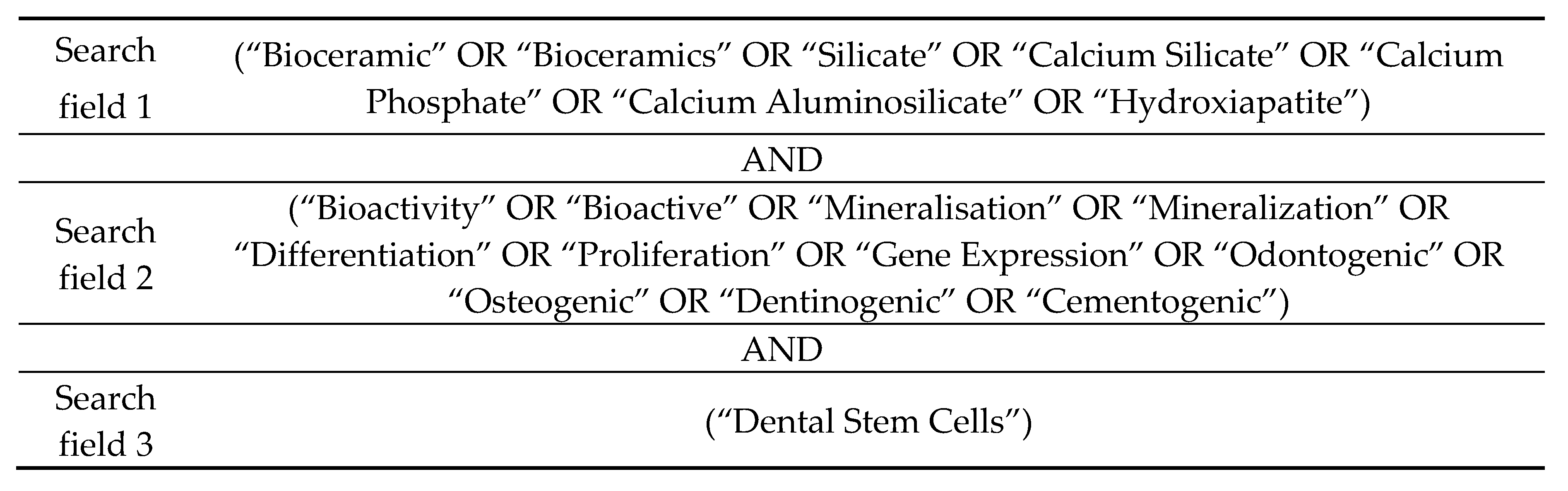

2.2.2. Search Terms

2.2.3. Study Selection

2.2.4. Study Data

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Flow Diagram

3.2. Study Characteristics

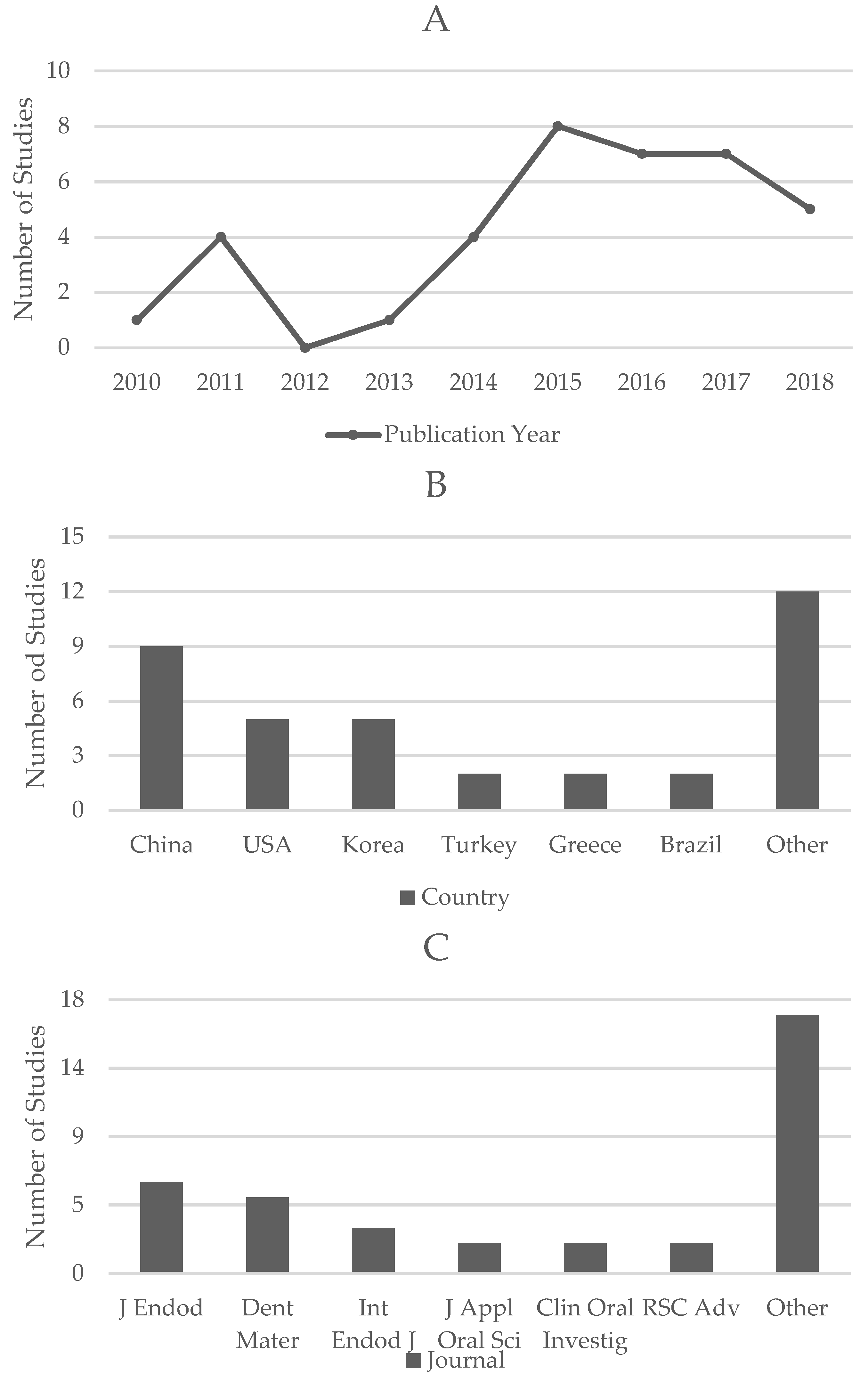

3.2.1. Bibliometric Analysis

3.2.2. Bioactivity Analysis

3.2.3. Study Type

3.2.4. Cell Variant

3.2.5. Bioceramic Materials Used

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Study Tesults

3.4.1. Results for RT-PCR Analysis

3.4.2. Results for ARS Staining

3.4.3. Results for ALP Activity

3.4.4. Results for Other Bioactivity-Related Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slavkin, H.C.; Bartold, P.M. Challenges and potential in tissue engineering. Periodontol 2000 2006, 41, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.G.; Malek, M.; Sigurdsson, A.; Lin, L.M.; Kahler, B. Regenerative endodontics: A comprehensive review. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 1367–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, S.S.; Jadhav, G.R.; Gathani, K.M.; Kotadia, P. Bioceramics in endodontics—A review. J. Istanb. Univ. Fac. Dent. 2017, 51, S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P.R.M. The rise of bioceramics in endodontics: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2015, 6, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Best, S.M.; Porter, A.E.; Thian, E.S.; Huang, J. Bioceramics: Past, present and for the future. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 28, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, P.; Linsuwanont, P. Vital pulp therapy in vital permanent teeth with cariously exposed pulp: A systematic review. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, A.; Soujanya, E.; Nandakumar, P. Recent advances in pulp capping materials: An overview. J. Clin. Diagn Res. 2014, 8, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.F. On the mechanisms of biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2941–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkel, B.; Dupas, C.; Armengol, V.; Apke Adou, J.; Bosco, J.; Daculsi, G.; Jean, A.; Laboux, O.; LeGeros, R.Z.; Weiss, P. Bioactive materials in endodontics. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2008, 5, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, O.A. Research that matters—Biocompatibility and cytotoxicity screening. Int. Endod. J. 2013, 46, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallittu, P.K.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Hupa, L.; Watts, D.C. Bioactive dental materials—Do they exist and what does bioactivity mean? Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 693–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Jain, A. Current overview on dental stem cells applications in regenerative dentistry. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, A.; Núñez-Toldrà, R.; Carrio, N.; Ferres-Padro, E.; Ali, H.; Montori, S.; Al Madhoun, A. The effect of commercially available endodontic cements and biomaterials on osteogenic differentiation of dental pulp pluripotent-like stem cells. Dent. J. 2018, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-González, M.; García-Bernal, D.; Oñate-Sánchez, R.E.; Ortolani-Seltenerich, P.E.; Álvarez-Muro, T.; Lozano, A.; Forner, L.; Llena, C.; Moraleda, J.M.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J. Cytotoxicity and bioactivity of various pulpotomy materials on stem cells from human exfoliated primary teeth. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.M.; Cornélio, A.L.G.; Mestieri, L.B.; Fuentes, A.S.C.; Salles, L.P.; Rossa-Junior, C.; Faria, G.; Guerreiro-Tanomaru, J.M.; Tanomaru-Filho, M. Human dental pulp cells response to mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) and MTA plus: Cytotoxicity and gene expression analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhtiar, H.; Nekoofar, M.H.; Aminishakib, P.; Abedi, F.; Naghi Moosavi, F.; Esnaashari, E.; Azizi, A.; Esmailan, S.; Ellini, M.R.; Mesgarzadeh, V.; et al. Human pulp responses to partial pulpotomy treatment with TheraCal as compared with biodentine and ProRoot MTA: A clinical trial. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-García, D.M.; Aguirre-López, E.; Méndez-González, V.; Pozos-Guillén, A. Cytotoxicity and initial biocompatibility of endodontic biomaterials (MTA and biodentine™) used as root-end filling materials. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 7926961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faggion, C.M. Guidelines for reporting pre-clinical in vitro studies on dental materials. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, A.K.; Shinaishin, S.F.; Eldeen, G.N.; Aly, R.M. Nano hydroxyapatite & mineral trioxide aggregate efficiently promote odontogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedano, M.S.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Sun, Z.; Cokic, S.M.; Putzeys, E.; Yoshihara, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Chen, Z.; Van Landuyt, K. Freshly-mixed and setting calcium-silicate cements stimulate human dental pulp cells. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, D. Osteogenic stimulation of human dental pulp stem cells with a novel gelatin-hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate scaffold. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2018, 106, 1851–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, B.; Reynolds, M.A.; Ma, J.; Schneider, A.; Gu, N.; Xu, H.H.K. Injectable calcium phosphate scaffold with iron oxide nanoparticles to enhance osteogenesis via dental pulp stem cells. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, F.; Bao, C.; Weir, M.D.; Reynolds, M.A.; Ma, J.; Gu, N.; Xu, H.H.K. Gold nanoparticles in injectable calcium phosphate cement enhance osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. Nanomedicine 2018, 14, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyung-Jung, K.; Min Suk, L.; Chan-Woong, M.; Jae-Hoon, L.; Hee Seok, Y.; Young-Joo, J. In vitro and in vivo dentinogenic efficacy of human dental pulp-derived cells induced by demineralized dentin matrix and HA-TCP. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsupa, N.; Nuntanaranont, T.; Kamolmattayakul, S.; Thuaksuban, N. Assessment of bone regeneration of a tissue-engineered bone complex using human dental pulp stem cells/poly(ε-caprolactone)-biphasic calcium phosphate scaffold constructs in rabbit calvarial defects. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 2017, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Hill, R.G.; Rawlinson, S.C.F. Zinc bioglasses regulate mineralization in human dental pulp stem cells. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalayin, C.; Tezel, H.; Dagci, T.; Karabay Yavasoglu, N.U.; Oktem, G.; Kose, T. In vivo performance of different scaffolds for dental pulp stem cells induced for odontogenic differentiation. Braz. Oral. Res. 2016, 30, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharidou, A.; Bakopoulou, A.; Kontonasaki, E.; Papachristou, E.; Hadjichristou, C.; Bousnaki, M.; Theodorou, G.; Papadopoulou, L.; Kantiranis, N.; Paraskevopoulos, K. Odontogenic differentiation and biomineralization potential of dental pulp stem cells inside mg-based bioceramic scaffolds under low-level laser treatment. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, L.N.; Pei, D.D.; Morris, M.; Jiao, K.; Huang, X.Q.; Primus, C.M.; Susin, F.L.; Bergeron, B.E.; Pashley, D.H.; Tay, F.R. Mineralogenic characteristics of osteogenic lineage-committed human dental pulp stem cells following their exposure to a discoloration-free calcium aluminosilicate cement. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.I.; Lee, E.S.; El-Fiqi, A.; Lee, S.Y.; Eun-Cheol, K.; Kim, H.W. Stimulation of odontogenesis and angiogenesis via bioactive nanocomposite calcium phosphate cements through integrin and VEGF signaling pathways. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2016, 12, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakopoulou, A.; Papachristou, E.; Bousnaki, M.; Hadjichristou, C.; Kontonasaki, E.; Theocharidou, A.; Papadopoulou, L.; Kantiranis, N.; Zachariadis, G.; Leyhausen, G. Human treated dentin matrices combined with zn-doped, mg-based bioceramic scaffolds and human dental pulp stem cells towards targeted dentin regeneration. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoluzzi, E.A.; Niu, L.; Palani, C.D.; El-Awady, A.R.; Hammond, B.D.; Pei, D.D.; Tian, F.C.; Cutler, C.W.; Pashley, D.H.; Tay, F.R. Cytotoxicity and osteogenic potential of silicate calcium cements as potential protective materials for pulpal revascularization. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1510–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natu, V.P.; Dubey, N.; Loke, G.C.L.; Tan, T.S.; NG, W.H.; Yong, C.W.; Cao, T.; Rosa, V. Bioactivity, physical and chemical properties of MTA mixed with propylene glycol. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widbiller, M.; Lindner, S.; Buchalla, W.; Eidt, A.; Hiller, K.A.; Schmalz, G.; Galler, K.M. Three-dimensional culture of dental pulp stem cells in direct contact to tricalcium silicate cements. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Lei, D.; Xiao, L.; Cheng, X.; Lin, Y.; Peng, B. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a nanoparticulate bioceramic paste for dental pulp repair. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 5156–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Kohli, M.R.; Yu, Q.; Kim, S.; Qu, T.; He, W.X. Biodentine induces human dental pulp stem cell differentiation through mitogen-activated protein kinase and calcium-/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II pathways. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, S.; Nazarian, H.; Khojasteh, A.; Shokouhinejad, N. Gene expression and cytokine release during odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells induced by 2 endodontic biomaterials. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, M.; Fan, Z.; Ma, L.; Yu, Y.; Yu, J. Mineral trioxide aggregate enhances the odonto/osteogenic capacity of stem cells from inflammatory dental pulps via NF-κB pathway. Oral. Dis. 2014, 20, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Won, J.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, H.W. Odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells stimulated by the calcium phosphate porous granules. J. Tissue Eng. 2011, 2011, 812547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yang, F.; Shen, H.; Hu, X.; Mohizuki, C.; Sato, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. The effect of composition of calcium phosphate composite scaffolds on the formation of tooth tissue from human dental pulp stem cells. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7053–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; He, W.; Song, Z.; Tong, Z.; Li, S.; Ni, L. Mineral trioxide aggregate promotes odontoblastic differentiation via mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in human dental pulp stem cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjpe, A.; Zhang, H.; Johnson, J.D. Effects of mineral trioxide aggregate on human dental pulp cells after pulp-capping procedures. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.G.; Ho, C.C.; Hsu, T.T.; Huang, T.H.; Lin, M.J.; Shie, M.Y. Mineral trioxide aggregate with mussel-inspired surface nanolayers for stimulating odontogenic differentiation of dental pulp cells. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulan, P.; Karabiyik, O.; Kose, G.T.; Kargul, B. The effect of accelerated mineral trioxide aggregate on odontoblastic differentiation in dental pulp stem cell niches. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Dou, Y.; Huan, Z.; Chang, J. In vitro self-setting properties, bioactivity, and antibacterial ability of a silicate-based premixed bone cement. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2018, 15, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, T.; Shen, Y.; Haapasalo, M.; Zou, L.; Liu, J. Effect of iRoot fast set root repair material on the proliferation, migration and differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells in vitro. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, B.; Chang, H.; Hwang, Y.; Hwang, I.; Oh, W. Effects of a novel light-curable material on odontoblastic differentiation of human dental pulp cells. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daltoé, M.O.; Paula-Silva, F.W.; Faccioli, L.H.; Gatón-Hernández, P.M.; De Rossi, A.; Bezerra Silva, L.A. Expression of mineralization markers during pulp response to biodentine and mineral trioxide aggregate. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandolfi, M.; Spagnuolo, G.; Siboni, F.; Procino, A.; Riviecco, V.; Pelliccioni, G.A.; Prati, C.; Rengo, S. Calcium silicate/calcium phosphate biphasic cements for vital pulp therapy: Chemical-physical properties and human pulp cells response. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 2075–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestieri, L.B.; Gomes-Cornélio, A.L.; Rodrigues, E.M.; Salles, L.P.; Bosso-Martelo, R.; Guerreiro-Tanomaru, J.M.; Filho, M.T. Biocompatibility and bioactivity of calcium silicate-based endodontic sealers in human dental pulp cells. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbdulQader, S.T.; Kannan, T.P.; Rahman, I.A.; Ismail, H.; Mahmood, Z. Effect of different calcium phosphate scaffold ratios on odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 49, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; Chang, J.; Sun, J. Odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp cells induced by silicate-based bioceramics via activation of P38/MEPE pathway. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 72536–72543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Yun, H.-M.; Perez, R.-A.; Gallinetti, S.; Ginebra, M.-P.; Choi, S.-J.; Kim, E.-C.; Kim, H.-W. Nanotopological-tailored calcium phosphate cements for the odontogenic stimulation of human dental pulp stem cells through integrin signaling. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 63363–63371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncel Torun, Z.; Torun, D.; Demirkaya, K.; Yavuz, S.T.; Elçi, M.P.; Sarper, M.; Avcu, F. Effects of iRoot BP and white mineral trioxide aggregate on cell viability and the expression of genes associated with mineralization. Int. Endod. J. 2015, 48, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Liu, W.; Zhai, W.; Jiang, L.; Li, L.; Chang, J.; Zhu, Y. Effect of tricalcium silicate on the proliferation and odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp cells. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathinam, E.; Rajasekharan, S.; Chitturi, R.T.; Martens, L.; De Coster, P. Gene expression profiling and molecular signaling of dental pulp cells in response to tricalcium silicate cements: A Systematic review. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithikadatta, J.; Gopikrishna, V.; Datta, M. CRIS guidelines (checklist for reporting in-vitro studies): A concept note on the need for standardized guidelines for improving quality and transparency in reporting in-vitro studies in experimental dental research. J. Conserv. Dent. 2014, 17, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Variant | Study Type | Bioceramics Used | Author | Bioactivity Analysis * | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hDPSCs | In vitro | MTA, Nano-HA | Hanafy et al. [21] | RT-PCR (Runx2, OCN, ALP, COL1α, OPN); | 21 days |

| ARS | 21 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | Exp. PPL, BD, Nex-MTA | Pedano et al. [22] | RT-PCR (OCN, DSPP, ALP) | 4, 10 and 14 days |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | Gelatin-HA-TCP (10:1:1) | Gu et al. [23] | RT-PCR (Runx2, OSX, BSP); | 4, 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 4, 7 and 14 days | ||||

| ARS | 14 and 21 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | aIONP-CPC, bIONP-CPC | Xia et al. [24] | RT-PCR (ALP, COL1α, Runx2, OCN); | 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 4, 7 and 14 days | ||||

| ARS | 7, 14 and 21 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | GNP-CPC | Xia et al. [25] | RT-PCR (ALP, COL1α, Runx2); | 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 4, 7 and 14 days | ||||

| ARS | 4, 7, 14 and 21 days | ||||

| hDPCSs | In vitro, Animal | HA-TCP | Kyung-Jung et al. [26] | In vitro: RT-PCR (ALP, BSP, OPN, DMP-1, DSPP); | 10 days |

| In vivo: RT-PCR (BSP, OPN, ONT, OCN) | 8 weeks | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro, Animal | PCL-BCP | Wongsupa et al. [27] | RT-PCR (Runx2, ALP, OCN, DSPP); | 7, 14 and 21 days |

| Micro-CT; | 2, 4 and 8 weeks | ||||

| Histomorphometric analysis | 2, 4 and 8 weeks | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 | Huang et al. [28] | Western blot (DSPP, DMP-1); | 7 and 14 days |

| RT-PCR (Runx2, OCN, BSP, BMP-2, MEPE, ON); | 7 and 14 days | ||||

| ALP activity; | 1, 4, 7 and 10 days | ||||

| ARS | 3, 4 and 5 weeks | ||||

| DPSCs | Animal | HA-TCP | Atalayin et al. [29] | RT-PCR (DSPP, DMP-1, MMP20, PHEX) | 6 and 12 weeks |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | SC | Theocharidou et al. [30] | RT-PCR (DSPP, BMP-2, Runx2, OSX); | 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 3, 7 and 14 days | ||||

| Mineralization analysis using SEM | 28 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | Niu et al. [31] | RT-PCR (Runx2, OSX, ALP, BSP, OCN, DMP-1, DSPP); | 1, 2 and 3 weeks |

| Western blot (DMP-1, DSPP, OCN); | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | ||||

| ALP activity; | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | ||||

| ARS; | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | ||||

| ATR-FTIR; | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | ||||

| TEM | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | CPC-BGN | Lee SI et al. [32] | RT-PCR (DMP-1, DSPP, ALP, OPN, OCN, VEGF, (FGF)-2, (VEGFR)-2, VEGFR-1, (PECAM)-1, VE-cadherin; | 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 7 and 14 days | ||||

| ARS | N/S | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro, ex vivo | SC | Bakopoulou et al. [33] | RT-PCR (DSPP, BMP-2, Runx2, OSX, ALP, BGLAP); | 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 3, 7 and 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | BD, TheraCal, MTA | Bortoluzzi et al. [34] | RT-PCR (ALP, OCN, BSP, Runx2, DSPP, DMP-1); | 7 days |

| ALP activity; | 14 days | ||||

| ARS | 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | MTA+UW/PG | Natu et al. [35] | RT-PCR (ALP, OCN, Runx2, DSPP, MEPE); | 7 and 14 days |

| ARS | 7 and 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | BD, PR-MTA | Widbiller et al. [36] | RT-PCR (COL1α, ALP, DSPP, Runx2); | 7, 14 and 21 days |

| ALP activity | 3, 7 and 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro, Animal | iRoot BP Plus, PR-MTA | Zhu et al. [37] | SEM; | 1, 3 and 7 days |

| ATR-FTIR; | 1, 3 and 7 days | ||||

| microCT; | - | ||||

| Histologic analysis; | - | ||||

| Double immunofluorescence | - | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | BD | Luo et al. [38] | RT-PCR (OCN, DSPP, DMP1, BSP); | 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 1, 3, 7, 10 and 14 days | ||||

| ARS | 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | PR-MTA, CEM | Asgary et al. [39] | RT-PCR (FGF4, BMP2, BMP4, TGF-β1, ALP, COL1, DSPP, DMP1); | 1, 3, 7 and 14 days |

| ELISA (FGF4, BMP2, BMP4, TGF-β1); | 1, 3, 7 and 14 days | ||||

| ARS | 14 days | ||||

| iDPSCs | In vitro | MTA | Wang et al. [40] | RT-PCR (ALP, Runx2, OSC, OCN, DSPP); | 3 and 7 days |

| ALP activity; | 3 and 5 days | ||||

| ARS | 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | CaP granules | Nam et al. [41] | RT-PCR (DSPP, DMP1, COL1, OCN); | 7, 14 and 21 days |

| ALP activity; | 7, 14 and 21 days | ||||

| ARS; | 28 days | ||||

| Western blot | 21 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro, ex vivo | PLGA/HA, PLGA/CDHA, PLGA/TCP | Zheng et al. [42] | ALP activity; | N/S |

| Von Kossa staining and Gene Tool analysis | 4 and 5 weeks | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | MTA | Zhao et al. [43] | RT-PCR (ALP, DSPP, COL1, OCN, BSP) | 6, 12, 24 and 48 h |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | PR-MTA | Paranjpe et al. [44] | RT-PCR (Runx2, OCN, ALP, DSP) | 1, 4 and 7 days |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | DA0, DA0.5, DA1 | Tu et al. [45] | TRACP & ALP assay kit (Takahara, Shiga, Japan); | 3 and 7 days |

| OC and DSP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (ThermoFisher Scientific) | 7 and 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | PR-MTA, MTA-CaCl2, MTA-Na2HPO4 | Kulan et al. [46] | RT-PCR (DSPP, COL1); | 14 and 21 days |

| ALP activity; | 7 and 14 days | ||||

| Von Kossa staining | 21 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | CSC | Xu et al. [47] | ALP activity | 10 days |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | iRoot FS, BD at 0.2 and 2 mg/mL | Sun et al. [48] | RT-PCR (COL1, OCN); | 1, 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity; | 7 and 14 days | ||||

| ARS | 21 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | TheraCal, PR-MTA | Lee BN et al. [49] | RT-PCR (DSPP, DMP1); | 1 and 3 days |

| ALP activity; | 7 days | ||||

| ARS | 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro, Animal | BD, MTA | Daltoé et al. [50] | RT-PCR (SPP1, IBSP, DSPP, ALPL, DMP1, Runx2); | 24 and 48 h |

| Immunohistochemical assays for OPN y ALP; | 120 days | ||||

| Indirect immunofluorescence for Runx2; | 120 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | CaSi-αTCP, CaSi-DCPD | Gandolfi et al. [51] | RT-PCR (ALP, OCN) | 24 h |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | MTAP, MTAF | Mestieri et al. [52] | ALP activity | 1 and 3 days |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | BCP at a ratio of 20/80, 50/50 y 80/20 | AbdulQader et al. [53] | RT-PCR (COL1A1, BSP, DMP1, DSPP); | 14, 21 and 28 days |

| ALP activity; | 0–3, 3–6, 6–9, 9–12 and 12–15 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | CSP | Zhang et al. [54] | RT-PCR (DMP1, DSPP, Runx2, OPN); | 3 and 10 days |

| ALP activity | 3 and 10 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | CPC-N, CPC-M | Lee SY et al. [55] | RT-PCR (DMP1, DSPP, OCN, OPM, BSP); | 7 and 14 days |

| ALP activity | 7 and 14 days | ||||

| hDPSCs | In vitro | iRoot BP, MTA diluted at 1:1, 1:2 o 1:5 | Öncel Torun et al. [56] | RT-PCR (BMP, ON, BSP, OPN, DSPP, COL1A1, HO-1) | 24 and 72 h |

| hDPSCs | In vitro | Ca3SiO5 | Peng et al. [57] | RT-PCR (ALP, DSPP, DMP1, COL1, OC) | 4, 7 and 10 days |

| ALP activity; | 4, 7 and 10 days | ||||

| ARS | 30 days |

| Material | Abbreviation | Manufacturer | Times Studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral Trioxide Aggregate | MTA | Angelus Dental Solutions, Londrina, PR, Brazil | 3 |

| Nano-hydroxiapatite | Nano-HA | Sigma-Aldrich, UK | 1 |

| Biodentine (tricalcium silicate) | BD | Septodont, Saint Maurdes-Fosses, France | 7 |

| Nex-Cem MTA | Nex MTA | GC, Tokyo, Japan | 1 |

| Hydroxiapatite-Tricalcium Phosphate | HA-TCP | OSSTEM Implant Co., Ltd., New Zealand | 1 |

| Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA | 1 | ||

| N/S | 1 | ||

| ProRoot Mineral Trioxide Aggregate | PR-MTA | Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties, Tulsa, OK, USA | 10 |

| Quick-Set2 | - | Primus Consulting, Bradenton, FL, USA | 1 |

| TheraCal LC | TheraCal | Bisco Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA | 2 |

| iRoot BP Plus | - | Innovative Bioceramix, Vancouver, BC, Canada | 1 |

| Calcium-enriched mixture | CEM | BioniqueDent, Tehran, Iran | 1 |

| Hydroxyapatite | HA | N/S | 1 |

| iRoot Fast Set root repair material | FS | Innovative Bioceramix, Vancouver, BC, Canada | 1 |

| MTA Plus | MTAP | Avalon Biomed Inc., Bradenton, FL, USA | 1 |

| MTA Fillapex | MTAF | Angelus S/A, Londrina, PR, Brazil | 1 |

| FillCanal | FC | Technew, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil | 1 |

| iRoot BP | iRoot BP | Innovative Bioceramix, Vancouver, BC, Canada | 1 |

| Material | Abbreviation | Composition | Times Studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium-silicate cement containing phosphopullulan | Exp. PPL | 60% portland cement, 20% bismuth oxide, 5% calcium sulfate dehydrate, PPL (5%), other (10%) | 1 |

| Gelatin-hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate scaffold | Gelatin-HA-TCP | Three types of powdered gelatin, HA and TCP at a ratio of 10:1:1 | 1 |

| Poly-ɛ-caprolactane–biphasic calcium phosphate | PCL-BCP | 80% poly-ɛ-caprolactane, 20% biphasic calcium phosphate | 1 |

| Zinc Bioglass | Zn0 | 38.5% SiO2, 26.2% Na2O, 29.0% CaO, 6.3% P2O5, 0% ZnO | 1 |

| Zn1 | 37.0% SiO2, 26.5% Na2O, 29.2% CaO, 6.3% P2O5, 1.0% ZnO | 1 | |

| Zn2 | 35.7% SiO2, 26.7% Na2O, 29.4% CaO, 6.2% P2O5, 2.0% ZnO | 1 | |

| Zn3 | 34.3% SiO2, 27.0% Na2O, 29.6% CaO, 6.1% P2O5, 3.0% ZnO | 1 | |

| Mg-based, Zn-doped bioceramic scaffolds | SC | 60% SiO2; 7.5% MgO; 30% CaO; 2.5% ZnO | 2 |

| Calcium phosphate porous granules | CaP granules | N/S | 1 |

| Gelatin-hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate | Gelatin-HA-TCP | A mixture of 3 types of powdered gelatin, HA and TCP at a ratio of 10:1:1 was added to ultrapure water to form the scaffold | 1 |

| Calcium silicate | CaSi | Dicalcium silicate, tricalcium silicate, tricalcium aluminate, calcium sulfate | 1 |

| Calcium silicate-alpha tricalcium phosphate | CaSi-αTCP | Ca3(PO4)2 | 1 |

| Calcium silicate-dicalcium phosphate dihydrate | CaSi-DCPD | CaHPO4·2H2O | 1 |

| Hydroxyapatite-β-tricalcium phosphate | BCP | Ca5(PO4)3(OH)/ Ca3(PO4)2 at ratios of 20/80, 50/50 and 80/20 | 1 |

| Silicate based Ca7Si2P2O16 bioceramic extract | CSP | Ca7Si2P2O16 diluted at a 200, 100, 50 and 25 mg/mL | 1 |

| Calcium phosphate cements in the form of nano and microparticles | CPC-N, CPC-M | α-TCP | 1 |

| Tricalcium silicate | Ca3SiO5 | Ca3SiO5 | 1 |

| Material | Bioceramic Material Composition | Additive | Additive Composition | Abbreviation | Times Studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium phosphate cement | Tetracalcium phosphate Ca4(PO4)2O + dicalcium phosphate anhydrous (CaHPO4) | Iron oxide nanoparticles | Hematite, αFe2O3 | αIONP-CPC | 1 |

| Maghemite, βFe2O3 | βIONP-CPC | ||||

| Calcium phosphate cement | Tetracalcium phosphate Ca4(PO4)2O + dicalcium phosphate anhydrous (CaHPO4) | Gold nanoparticles | Gold (III) chloride trihydrate, sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate | GNP-CPC | 1 |

| Calcium phosphate | α-tricalcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2) | Bioactive glass nanoparticles | 85% SiO2, 15% CaO | CPC-BGN | 1 |

| Hydroxyapatite | Ca5(PO4)3(OH) | Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) | - | PLGA/HA | 1 |

| Hydroxiapatite-Calcium carbonate | CaCO3 + Ca5(PO4)3(OH) | Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) | - | PLGA/CDHA | 1 |

| Tricalcium phosphate | Ca3(PO4)2 | Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) | - | PLGA/TCP | 1 |

| Mg-based, Zn-doped bioceramic scaffolds | 60% SiO2; 7.5% MgO; 30% CaO; 2.5% ZnO | Low level laser irradiation | - | SC + LLLI | 1 |

| Premixed C3S/CaCl2 paste | C3S/CaCl2 | Polyethylene glycol | - | CSC | 1 |

| ProRoot MTA | - | Propylene glycol and ultrapure water | - | MTA + UW/PG | 1 |

| ProRoot MTA | - | Polydopamine | 0 mg/mL polydopamine | DA0 | 1 |

| 0.5 mg/mL polydopamine | DA0.5 | 1 | |||

| 1 mg/mL polydopamine | DA1 | 1 | |||

| ProRoot MTA | - | Calcium chloride | CaCl2 | MTA-CaCl2 | 1 |

| ProRoot MTA | - | Sodium phosphate dibasic | Na2HPO4 | MTA-Na2HPO4 | 1 |

| Studies | Modified CONSORT Checklist of Items for Reporting In Vitro Studies of Dental Materials | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2a | 2b | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| Hanafy et al. [21] | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Pedano et al. [22] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Gu et al. [23] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Xia et al. [24] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Xia et al. [25] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Kyung-Jung et al. [26] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Wongsupa et al. [27] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Huang et al. [28] | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Theocharidou et al. [30] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Niu et al. [31] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Lee SI et al. [32] | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Bakopoulou et al. [33] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Bortoluzzi et al. [34] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Natu et al. [35] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Widbiller et al. [36] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Zhu et al. [37] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Luo et al. [38] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Asgary et al. [39] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Wang et al. [40] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Nam et al. [41] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Zheng et al. [42] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Zhao et al. [43] | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Paranjpe et al. [44] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Tu et al. [45] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Kulan et al. [46] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Xu et al. [47] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Sun et al. [48] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Lee BN et al. [49] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Daltoé et al. [50] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Gandolfi et al. [51] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Mestieri et al. [52] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| AbdulQader et al. [53] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Zhang et al. [54] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Lee SY et al. [55] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Öncel Torun et al. [56] | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Peng et al. [57] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Studies | ARRIVE Checklist of Items for Reporting In Vivo Experiments (Animal Research) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

| Kyung-Jung et al. [26] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Wongsupa et al. [27] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Atalayin et al. [29] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Zhu et al. [37] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Daltoé et al. [50] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Gene | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedano et al. [22] | Exp. PPL, BD, Nex-MTA | Exp. PPL, Biodentine > Nex MTA | DSPP | 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| OCN | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Biodentine > Nex MTA | DSPP | 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Xia et al. [24] | αIONP-CPC, βIONP-CPC | γION-CPC > αION-CPC | COL1α | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Hanafy et al. [21] | MTA, Nano-HA | Nano-HA > MTA | OPN, Runx2, OCN | 21 days | p < 0.05 |

| Niu et al. [31] | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | Quick-Set2 > PR-MTA | Runx2 | 1 and 2 weeks | p < 0.001 |

| OSX | 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| ALP | 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| BSP | 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| PR-MTA > Quick-Set2 | ALP | 1 week | p < 0.001 | ||

| OCN | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| DMP-1 | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| DSPP | 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| Sun et al. [48] | iRoot FS, BD at 0.2 and 2 mg/mL | FS0.2 > BD0.2 > BD2 > FS2 | COL1 | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| FS0.2 > FS2 > BD2, BD0.2 | OCN | 7 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| FS0.2 > BD0.2, BD2 > FS2 | COL1 | 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| FS0.2, FS2 > BD0.2, BD2 | OCN | 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| AbdulQader et al. [53] | BCP at a ratio of 20/80, 50/50 y 80/20 | BCP20 > BCP50-80 | DMP-1, DSPP | 14, 21 and 28 days | p < 0.05 |

| BSP | 21 and 28 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| BCP50 > BCP80 | BSP | 28 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Öncel Torun et al. [56] | iRoot BP, MTA diluted at 1:1, 1:2 o 1:5 | 1:1MTA > 1:1iRoot BP | OPN, DSPP | 72 h | p < 0.05 |

| HO1, BMP2, BSP | 24 and 72 h | p < 0.05 | |||

| 1:1iRoot BP > 1:1 MTA | DSPP | 24 h | p < 0.05 | ||

| ON, COL1A1 | 24 and 72 h | p < 0.05 | |||

| 1:2MTA > 1:2iRoot BP | BMP2, ON, BSP | 72 h | p < 0.05 | ||

| HO1 | 24 and 72 h | p < 0.05 | |||

| 1:2iRoot BP > 1:2 MTA | OPN | 24 h | p < 0.05 | ||

| DSPP, COL1A1 | 72 h | p < 0.05 | |||

| 1:5MTA > 1:5iRoot BP | HO1, OPN, ON | 72 h | p < 0.05 | ||

| BMP2 | 24 and 72 h | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Gene | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xia et al. [24] | αIONP-CPC, βIONP-CPC | γION-CPC, αION-CPC > CPC | COL1α | 7 days | p < 0.01 |

| ALP, Runx2 | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| OCN | 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Xia et al. [25] | GNP-CPC | GNP-CPC > CPC | COL1α, ALP, Runx2 | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.01 |

| OCN | 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Theocharidou et al. [30] | SC | SC + low level laser treatment > SC | DSPP, BMP-2, OSX, Runx2 | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Lee SI et al. [32] | CPC-BGN | CPC-BGN10% > CPC-BGN5% > CPC-BGN2% | OPN, DSPP, FGF2, VEGF, PECAM-1 | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| VEGFR1 | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| CPC-BGN10% > CPC-BGN2% | DMP-1, VEGFR2. VE-cadherin | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| CPC-BGN2, 5, 10% > CPC-BGN0% | PECAM-1, DSPP | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| ALP, OPN, DMP-1, VEGF, VEGFR1, VE-cadherin | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| CPC-BGN5, 10% > CPC-BGN0% | FGF2 | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| OPN, VEGF | 7 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| OCN | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| CPC-BGN10% > CPC-BGN0% | VEGFR2 | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| DMP-1, VE-cadherin | 7 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Bakopoulou et al. [33] | SC | hTDM/SC > SC | BMP-2 | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| DSPP | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| SC > hTDM | Runx2 | 7 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Natu et al. [35] | MTA + UW/PG | MTA + UW/PG (100/0) > MTA + UW/PG (50/50) | OCN, DSPP | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Kulan et al. [46] | PR-MTA, MTA-CaCl2, MTA-Na2HPO4 | MTA-CaCl2, MTA-Na2HPO4 > PR-MTA + distilled water | COL1, DSPP | 14 and 21 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Gene | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedano et al. [22] | Exp. PPL, BD, Nex-MTA | Biodentine, Exp. PPL, Nex MTA < control | ALP | 4 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| DSPP, OCN | 4 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Biodentine > control | DSPP, OCN | 10 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Biodentine, Ex. PPL > control | OCN | 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Gu et al. [23] | Gelatin-HA-TCP (10:1:1) | Gel-HA-TCP > control | Runx2 | 4 days | p < 0.01 |

| OSX | 7 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| BSP | 4 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Kyung-Jung et al. [26] | HA-TCP | HA-CPC > control | ALP | 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| BSP | 10 days | p < 0.001 | |||

| Control > HA-CPC | OPN, DMP-1 | 10 days | p < 0.01 | ||

| DSPP | 10 days | p < 0.001 | |||

| Huang et al. [28] | Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 | Zn1, Zn2 > control | Runx2 | 7 days | p < 0.01 |

| Zn0 > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Zn1 > control | ON | 7 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Zn0 > control | OCN | 7 days | p < 0.01 | ||

| Zn3 > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Zn0 > control | MEPE | 7 days | p < 0,05 | ||

| Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 7 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | BSP | 7 days | p < 0.01 | ||

| Zn0 > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | BMP-2 | 7 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Zn0, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Zn1 > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Bakopoulou et al. [33] | SC | SC > control | DSPP, BMP-2, BGLAP | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| OSX | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Control > SC | ALP | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Runx2 | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Niu et al. [31] | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA > control | Runx2 | 1 and 2 weeks | p < 0.001 |

| OSX, DSPP | 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| ALP | 1 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| BSP | 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| OCN, DMP-1 | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| Bortoluzzi et al. [34] | BD, TheraCal LC, MTA | Biodentine, MTA > control | ALP, OCN, BSP, DSPP, DMP-1 | 7 days | p < 0.0085 |

| Luo et al. [38] | BD | Biodentine 0.2 mg/mL, Biodentine 2 mg/mL > control | OCN, DSPP, DMP1, BSP | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Wang et al. [40] | MTA | MTA > control | OCN | 3 days | P < 0.05 |

| Runx2, OSX, DSPP | 3 and 7 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| ALP, OCN | 7 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Nam et al. [41] | CaP granules | CaP > control | DSPP, DMP1, OCN | 21 days | p < 0.01 |

| COL1 | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| CaP > control | COL1, OCN, DSPP | 7 days | p < 0.01 | ||

| DMP1 | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Zhao et al. [43] | MTA | MTA > control | ALP, DSPP, COL1, BSP | 6, 12, 24 and 48 h | p < 0.05 |

| OCN | 12, 24 and 48 h | p < 0.05 | |||

| MTA 0.2 mg/mL, MTA 2 mg/mL > control | ALP, DSPP, COL1, BSP, OCN | 48 h | p < 0.05 | ||

| Paranjpe et al. [44] | MTA | MTA > control | OCN, ALP, DSP | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| Runx2 | 4 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Sun et al. [48] | iRoot FS, BD at 0.2 and 2 mg/mL | Control > BD2 | COL1 | 1 and 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| OCN | 7 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Control > BD0.2, FS0.2, FS2 | COL1 | 7 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| FS0.2 > control | OCN | 7 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| COL1 | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Lee BN et al. [49] | TheraCal, PR-MTA | PR-MTA > control | DSPP | 1 and 3 days | p < 0.05 |

| DMP | 3 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Theracal > control | DSPP, DMP | 3 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Daltoé et al. [50] | BD, MTA | Biodentine, MTA > control | SPP1, ALPL, Runx2 | 48 h | p < 0.05 |

| Gandolfi et al. [51] | CaSi-αTCP, CaSi-DCPD | CaSi-αTCP > control | ALP, OCN | 24 h | p < 0.05 |

| Zhang et al. [54] | CSP diluted at 200, 100, 50 y 25 mg/mL | CSP25, CSP50, CSP100, CSP200 > control | DSPP, DMP1 | 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| Runx2 | 3 and 10 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| CSP50, CSP100, CSP200 > control | DSPP, DMP1, OPN | 3 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| CSP100, CSP200 > control | OPN | 10 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Peng et al. [57] | Ca3SiO5 | Ca3SiO5 > control | ALP, DSPP | 4, 7 and 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| OC, DMP1 | 7 and 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Other Material Used | Bioactivity Analysis | Significant Results | Gene | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyung-Jung et al. [26] | HA-TCP | Demineralized dentin matrix | RT-PCR (ALP, BSP, OPN, DMP-1, DSPP) | DDM > HA-CPC | ALP, BSP, OPN | 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| DMP-1 | 10 days | p < 0.01 | |||||

| DSPP | 10 days | p < 0.001 | |||||

| Peng et al. [57] | Ca3SiO5 | Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) | RT-PCR (ALP, COL1, OC, DSPP, DMP1) | Ca3SiO5 > Ca(OH)2 | ALP, DSPP | 4, 7 and 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| Ca(OH)2 > Ca3SiO5 | OC, DMP1 | 7 and 10 days | p < 0.05 | ||||

| DMP1 | 4 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xia et al. [24] | αIONP-CPC, βIONP-CPC | γION-CPC > αION-CPC | 14 and 21 days | p < 0.05 |

| Niu et al. [31] | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | PR-MTA > Quick-Set2 | 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 |

| Lee BN et al. [49] | TheraCal, PR-MTA | PR-MTA > Theracal | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xia et al. [24] | αIONP-CPC, βIONP-CPC | γION-CPC, αION-CPC > CPC | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Xia et al. [25] | GNP-CPC | GNP-CPC > CPC | 14 and 21 days | p < 0.01 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gu et al. [23] | Gelatin-HA-TCP (10:1:1) | Gel-HA-TCP > control | 18 days | p < 0.01 |

| 21 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Huang et al. [28] | Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 | Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 3 weeks | p < 0.05 |

| Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 4 and 5 weeks | p < 0.05 | ||

| Niu et al. [31] | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | PR-MTA, Quick-Set2 > control | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 |

| Bortoluzzi et al. [34] | BD, TheraCal, MTA | Biodentine, TheraCal, MTA > control | 7 and 14 weeks | p < 0.05 |

| Luo et al. [38] | BD | Biodentine 0.2 mg/mL, Biodentine 2 mg/mL > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Wang et al. [40] | MTA | 0.2 mg/mL MTA > control | 14 days | p < 0.01 |

| Nam et al. [41] | CaP granules | CaP > control | 28 days | p < 0.01 |

| Sun et al. [48] | iRoot FS, BD at 0.2 and 2 mg/mL | FS0.2 > control | 21 days | p < 0.05 |

| Lee BN et al. [49] | TheraCal, PR-MTA | PR-MTA, Theracal > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Peng et al. [57] | Ca3SiO5 | Ca3SiO5 > control | 30 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xia et al. [24] | αIONP-CPC, βIONP-CPC | γION-CPC > αION-CPC | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Niu et al. [31] | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | PR-MTA > Quick-Set2 | 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 |

| Zheng et al. [42] | PLGA/HA, PLGA/CDHA, PLGA/TCP | PLGA/TCP > PLGA/HA, PLG/CDHA | N/S | p < 0.05 |

| Sun et al. [48] | iRoot FS, BD at 0.2 and 2 mg/mL | FS0.2, FS2, BD0.2 > BD2 | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| FS0.2 > BD0.2 > BD2, FS2 | 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Mestieri et al. [52] | MTAP, MTAF | MTAP > MTAF | 1 y 3 days | p < 0.05 |

| AbdulQader et al. [53] | BCP at a ratio of 20/80, 50/50 y 80/20 | BCP20 > BCP50, BCP20 | 3–6, 6–9, 9–12 and 12–15 days | p < 0.05 |

| BCP50 > BCP80 | 9–12 and 12–15 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Lee SY et al. [55] | CPC-N, CPC-M | CPC-N > CPC-M | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xia et al. [24] | αIONP-CPC,βIONP-CPC | γION-CPC, αION-CPC > CPC | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| 14 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Xia et al. [25] | GNP-CPC | GNP-CPC > CPC | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.01 |

| Theocharidou et al. [30] | SC | SC + LLLI > SC | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| SC > SC + LLLI | 14 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Lee SI et al. [32] | CPC-BGN | CPC-BGN2, 5, 10% > CPC-BGN0% | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Kulan et al. [46] | PR-MTA, MTA-CaCl2, MTA-Na2HPO4 | MTA-CaCl2, MTA-Na2HPO4 > PR-MTA + distilled water | N/S | p < 0.01 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Significant Results | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gu et al. [23] | Gelatin-HA-TCP (10:1:1) | Gel-HA-TCP > control | 4 days | p < 0.05 |

| 7 and 12 days | p < 0.01 | |||

| Huang et al. [28] | Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 | Zn3 > control | 1 day | p < 0.05 |

| Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | 7 and 10 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Niu et al. [31] | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | PR-MTA, Quick-Set2 > control | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 |

| Bakopoulou et al. [33] | SC | SC > control | 3, 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Bortoluzzi et al. [34] | BD, TheraCal, MTA | Biodentine, MTA, TheraCal > control | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Widbiller et al. [36] | BD, PR-MTA | Control > MTA | 3, 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Luo et al. [38] | BD | Biodentine 0.2 mg/mL, Biodentine 2 mg/mL > control | 7, 10 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Biodentine 0.2 mg/mL > control | 3 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| Wang et al. [40] | MTA | 0.02 mg/mL MTA > control | 3 days | p < 0.05 |

| 0.2 mg/mL MTA > control | 3 and 5 days | p < 0.01 | ||

| 2 mg/mL MTA > control | 5 days | p < 0.01 | ||

| Control > 20 mg/mL MTA | 3 and 5 days | p < 0.01 | ||

| Nam et al. [41] | CaP granules | CaP > control | 14 and 21 days | p < 0.01 |

| Xu et al. [47] | CSC | CSC > control | 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| Sun et al. [48] | iRoot FS, BD at 0.2 and 2 mg/mL | BD0.2, BD2, FS0.2, FS2 > control | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Lee BN et al. [49] | TheraCal, PR-MTA | MTA > control | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| Mestieri et al. [52] | MTAP, MTAF | Control > MTAP, MTAF | 1 and 3 days | p < 0.05 |

| Zhang et al. [54] | CSP diluted at 200, 100, 50 y 25 mg/mL | CSP50, CSP100, CSP200 > control | 3 and 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| Peng et al. [57] | Ca3SiO5 | Ca3SiO5 > control | 10 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Bioactivity Analysis | Significant Results | Gene | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. [28] | Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 | Western Blot | Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 > control | DSPP | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| Control > Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 | DSPP | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Zn2, Zn3 > control | DMP-1 | 7 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Control > Zn0, Zn1, Zn2, Zn3 | DSPP | 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| Niu et al. [31] | Quick-Set2, PR-MTA | Western Blot | PR-MTA > Quick-Set2 | DMP-1 DSPP, OCN | 1, 2 and 3 weeks 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 |

| PR-MTA, Quick-Set2 > control | DMP-1 DSPP | 1, 2 and 3 weeks 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 | |||

| PR-MTA > control | OCN | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| ATR-FTIR | PR-MTA > Quick-Set2 | - | 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | ||

| PR-MTA, Quick-Set2 > control | - | 1, 2 and 3 weeks | p < 0.001 | |||

| Asgary et al. [39] | MTA, CEM | ELISA | MTA > CEM | TFG-β1 | N/S | p < 0.05 |

| CEM > MTA | FGF4 | N/S | p < 0.05 | |||

| Zheng et al. [42] | PLGA/HA, PLGA/CDHA, PLGA/TCP | Gene Tool (level of grey in mineralization nodules analysis) | PLGA/TCP > PLGA/HA, PLG/CDHA | - | 4 weeks | p < 0.05 |

| PLGA/TCP > PLGA/HA | - | 5 weeks | p < 0.05 | |||

| Tu et al. [45] | DA0, DA0.5, DA1 | TRACP & ALP assay kit (Takahara, Shiga, Japan) | DA0.5, DA1 > DA0 | ALP | 7 days | p < 0.05 |

| DA1 > DA0 | ALP | 3 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| DA0.5, DA1 > DA0 | OCN | 7 and 14 days | p < 0.05 | |||

| OC and DSP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (ThermoFisher Scientific) | DA1 > DA0 | DSP | 7 days | p < 0.05 | ||

| DA0.5, DA1 > DA0 | DSP | 14 days | p < 0.05 |

| Author | Bioceramics Used | Non-Bioceramic Material Used | In Vivo Assay Description | Bioactivity Analysis | Results | Gene | Duration | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyung-Jung et al. [26] | HA-TCP | Demineralized dentin matrix | Ectopic bone fomation in athymic rats with HA-(HA-TCP or DDM) and HDPSCs implanted subcutaneously. | RT-PCR | HA-TCP > DDM | BSP | 8 weeks | p < 0.001 |

| Wongsupa et al. [27] | PCL-BCP | - | Bone formation in 1mm diameter calvarial defects in the parietal bone in 5–6-month-old male New Zealand white rabbits. | Micro-CT | PCL-BCP + hDPSCs > PCL-BCP | - | 4 and 8 weeks | p < 0.01 |

| Hysto-morphometric anaysis | PCL-BCP + hDPSCs > PCL-BCP | - | 2, 4 and 8 weeks | p < 0.01 | ||||

| Atalayin et al. [29] | HA-TCP | L-lactide/DL-lactide copolymer (PLDL), DL-lactide copolymer (PDL) | Odontogenic differentiation of hDPSCs in rats implanted with HA-CPC and hDPSCs subcutaneously. | RT-PCR (DSPP, DMP-1, MMP20, PHEX) | PDL > PLDL, HA/TCP | DSPP | 12 weeks | p < 0.05 |

| PLDL > PDL, HA-TCP | DMP1 | 6 weeks | p < 0.05 | |||||

| HA-TCP > PLDL, PDL | 12 weeks | p < 0.05 | ||||||

| PLDL, HA/TCP > PDL | MMP20 | 6 weeks | p < 0.05 | |||||

| PDL > PLDL, HA/TCP | 12 weeks | p < 0.05 | ||||||

| HA-TCP > PLDL, PDL | PHEX | p < 0.05 | ||||||

| PLDL > PDL, HA-TCP | p < 0.05 | |||||||

| Daltoé et al. [50] | BD, MTA | - | 87 specimens of 2nd and 3rd upper premolars and 2nd, 3rd, and 4th lower premolars from 4 dogs (Beagles), evaluated 120 days after pulpotomy. | Staining for OPN and ALP in mineralized tissue bridge | MTA > BD | OPN | 120 days | p < 0.001 |

| BD > MTA | ALP | 120 days | p < 0.001 | |||||

| Staining for OPN and ALP in pulp tissue | BD > MTA | OPN | 120 days | p < 0.001 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanz, J.L.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; Llena, C.; Sauro, S.; Forner, L. Bioactivity of Bioceramic Materials Used in the Dentin-Pulp Complex Therapy: A Systematic Review. Materials 2019, 12, 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12071015

Sanz JL, Rodríguez-Lozano FJ, Llena C, Sauro S, Forner L. Bioactivity of Bioceramic Materials Used in the Dentin-Pulp Complex Therapy: A Systematic Review. Materials. 2019; 12(7):1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12071015

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanz, José Luis, Francisco Javier Rodríguez-Lozano, Carmen Llena, Salvatore Sauro, and Leopoldo Forner. 2019. "Bioactivity of Bioceramic Materials Used in the Dentin-Pulp Complex Therapy: A Systematic Review" Materials 12, no. 7: 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12071015

APA StyleSanz, J. L., Rodríguez-Lozano, F. J., Llena, C., Sauro, S., & Forner, L. (2019). Bioactivity of Bioceramic Materials Used in the Dentin-Pulp Complex Therapy: A Systematic Review. Materials, 12(7), 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12071015