Enhanced Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Performance of Cuprous Oxide/Titania: The Effect of Titania Matrix

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Cu2O/TiO2 Photocatalysts

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Photocatalytic Activity Tests

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity Tests with Xenon Lamp Irradiation

2.5. Antibacterial Activity Test with Solar Irradiation

3. Results and Discussion

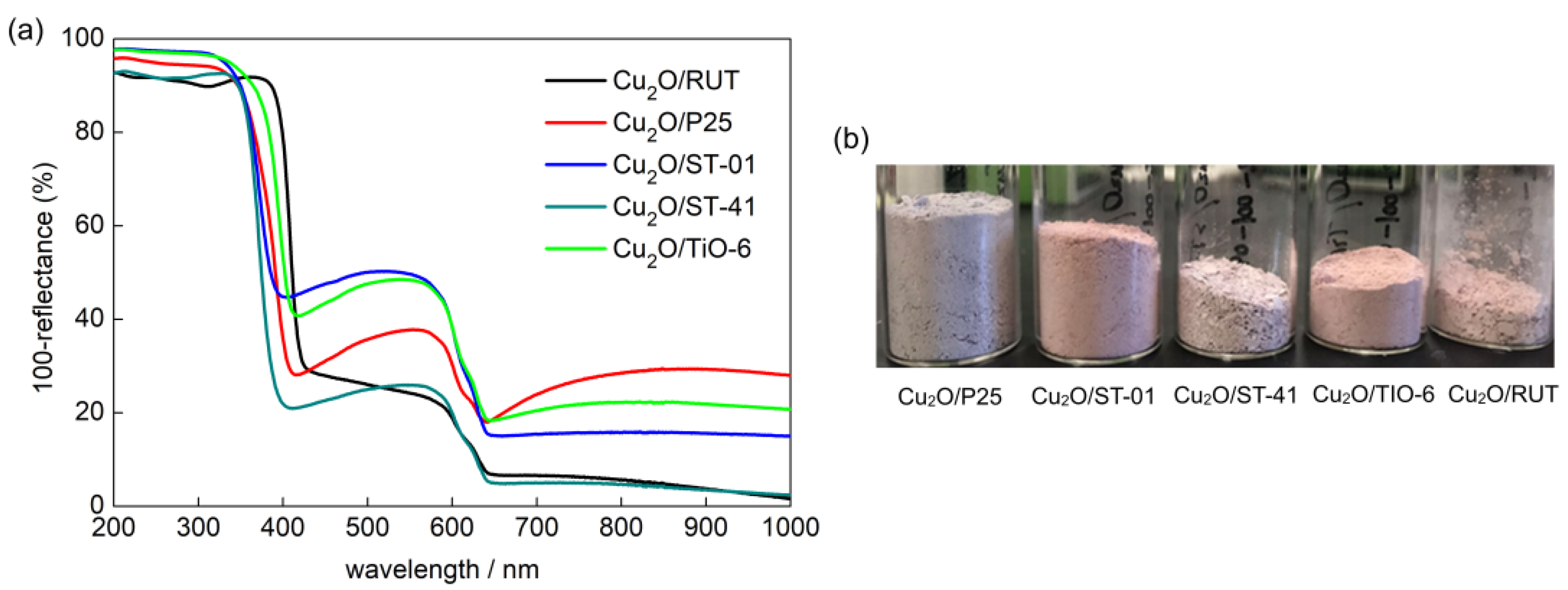

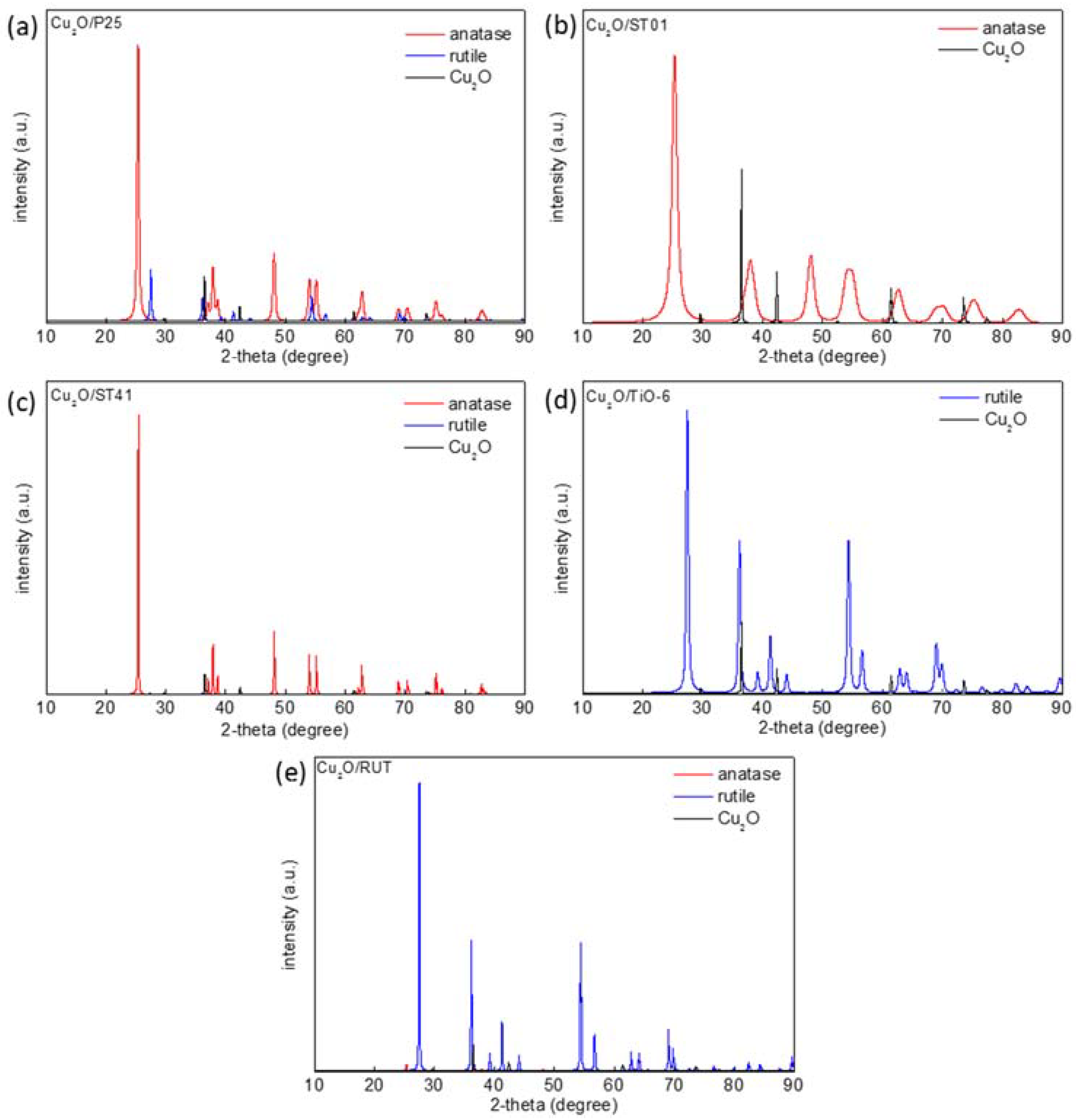

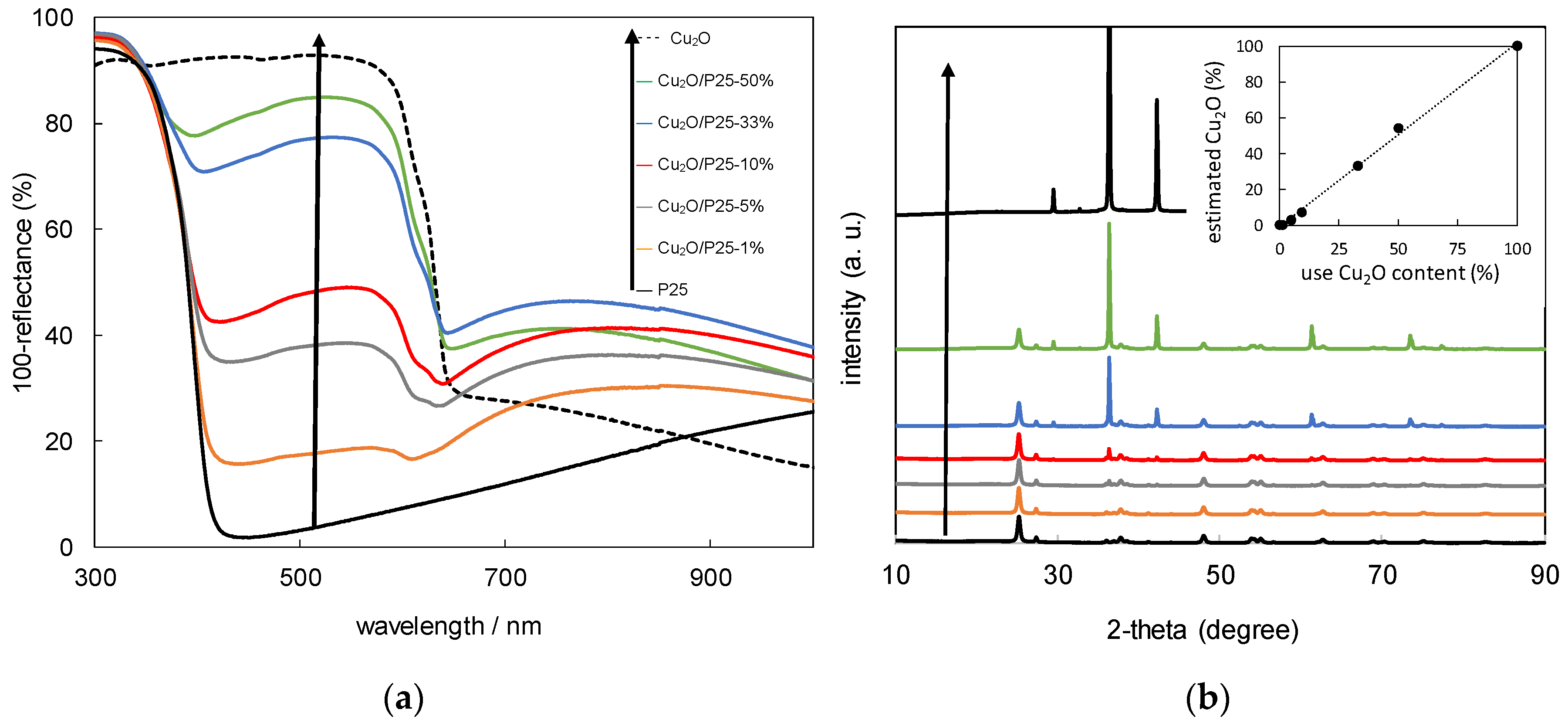

3.1. Characterization of Cu2O/TiO2 Samples

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity

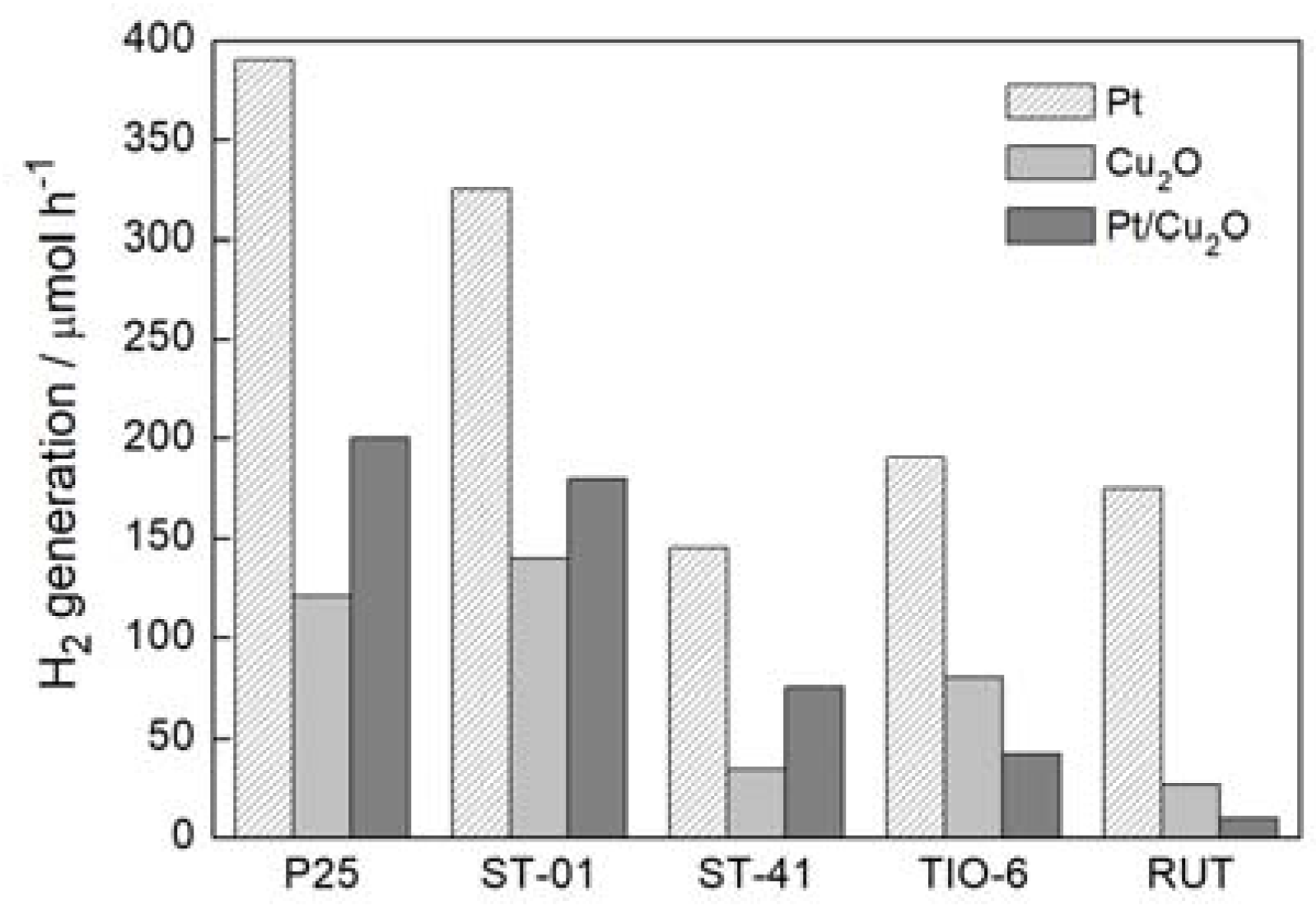

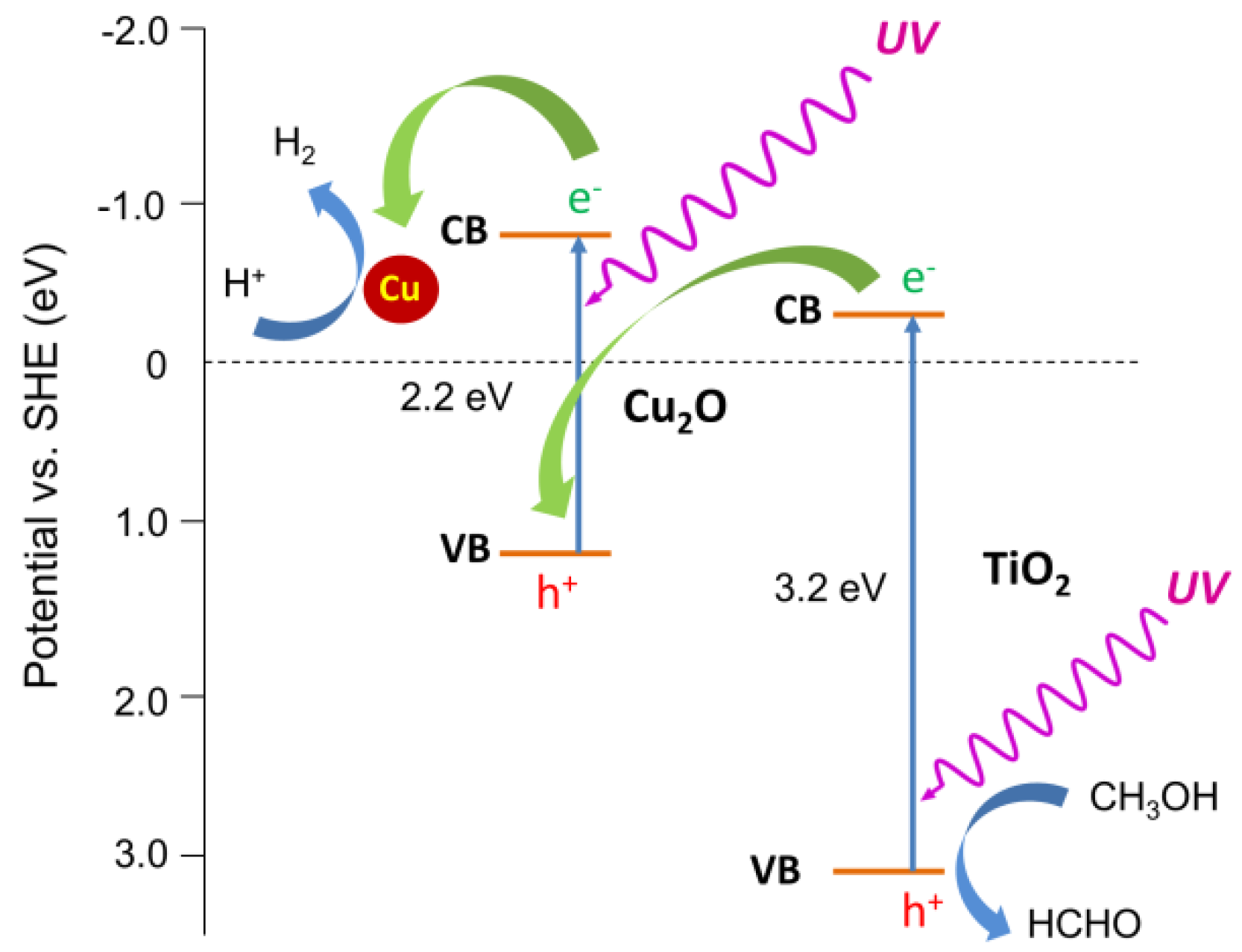

3.2.1. Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis)-Induced Methanol Dehydrogenation

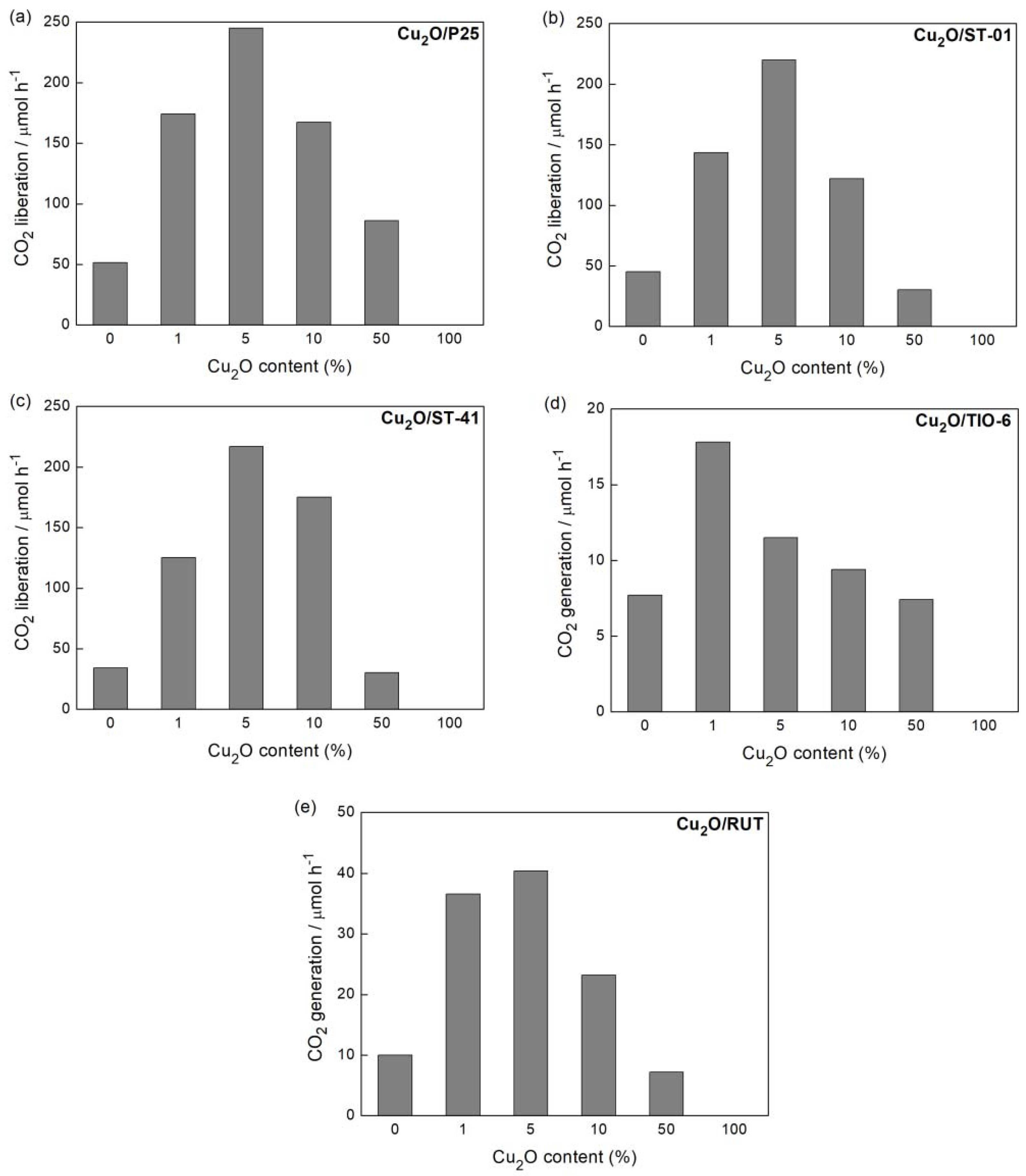

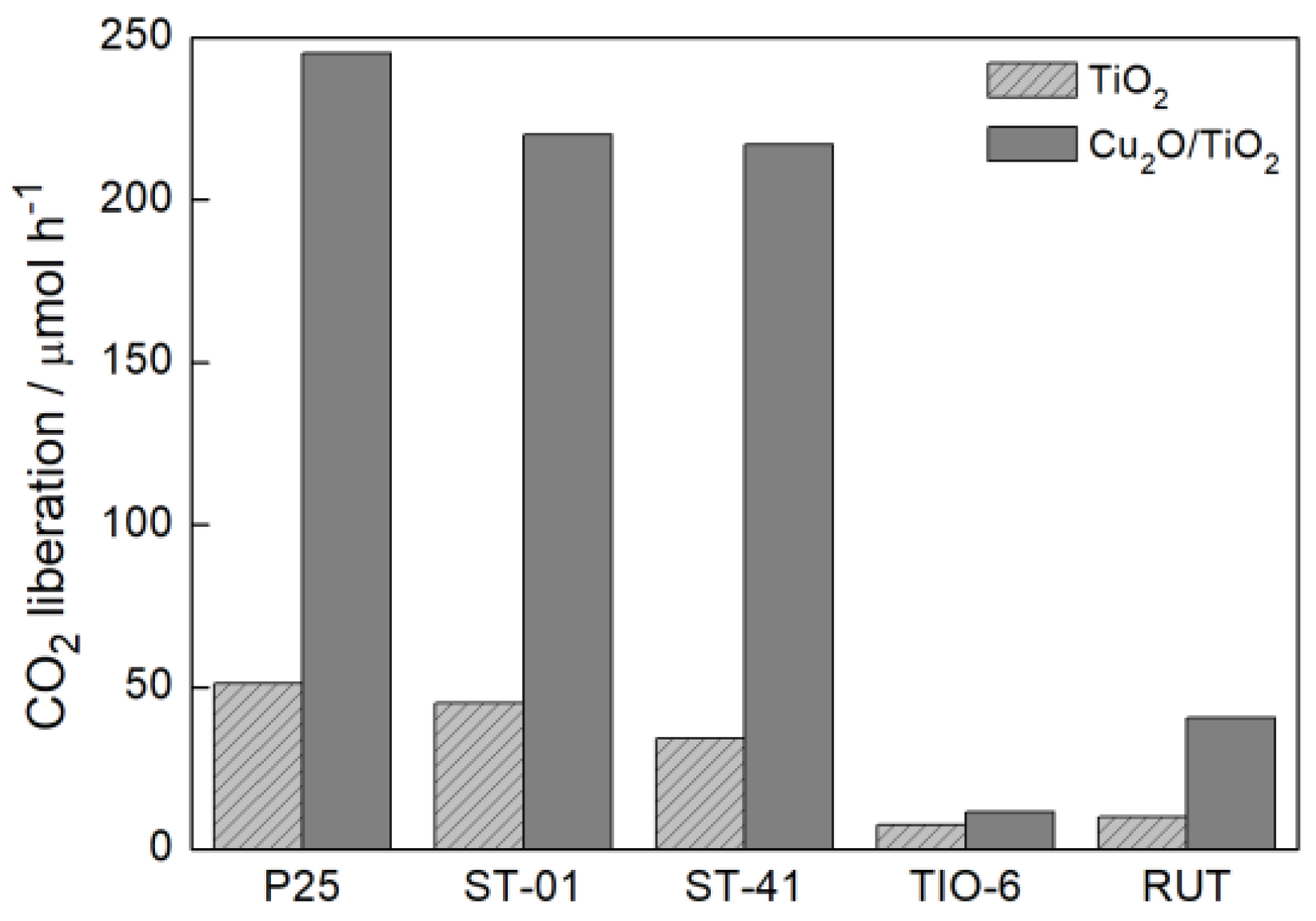

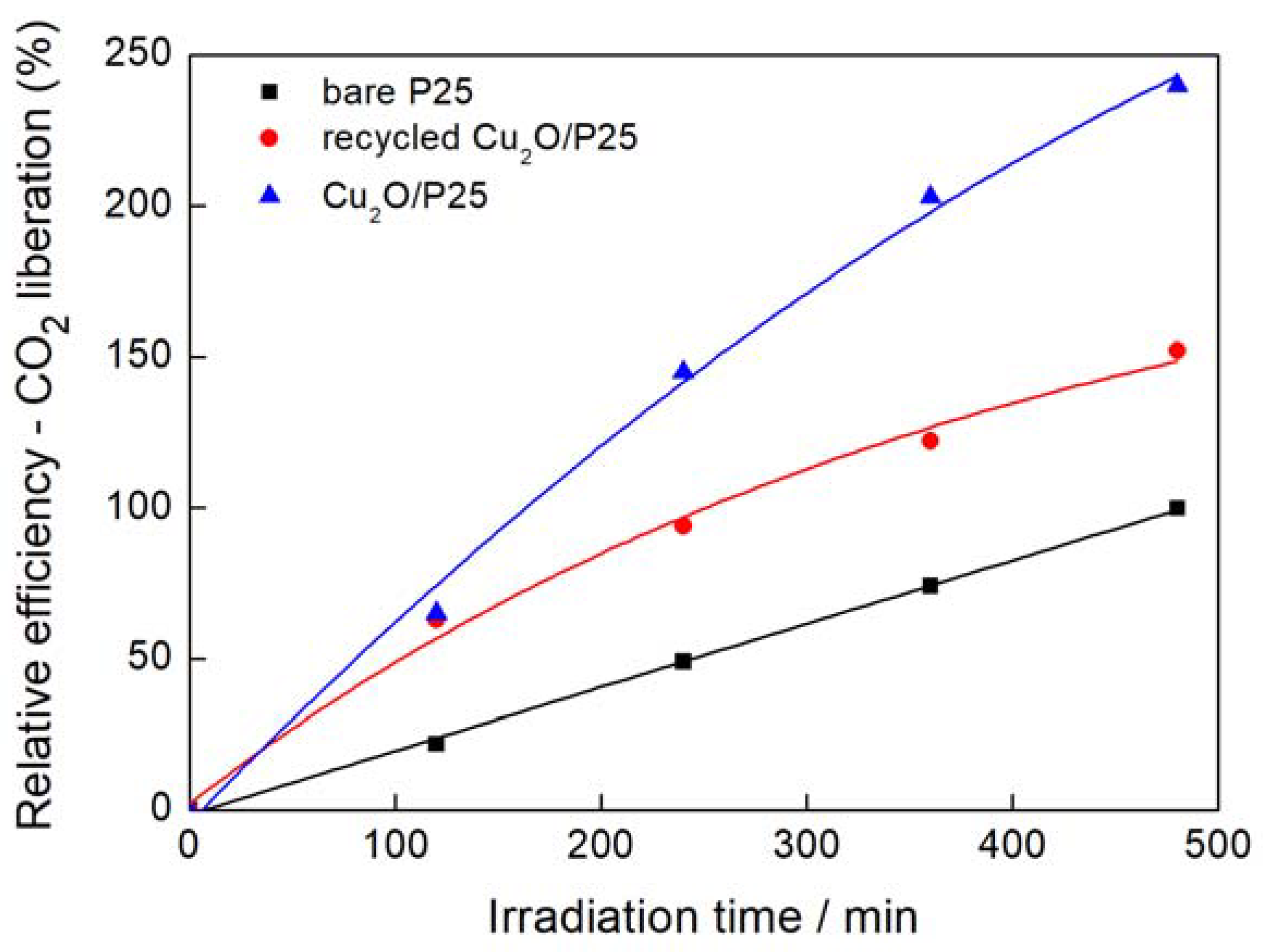

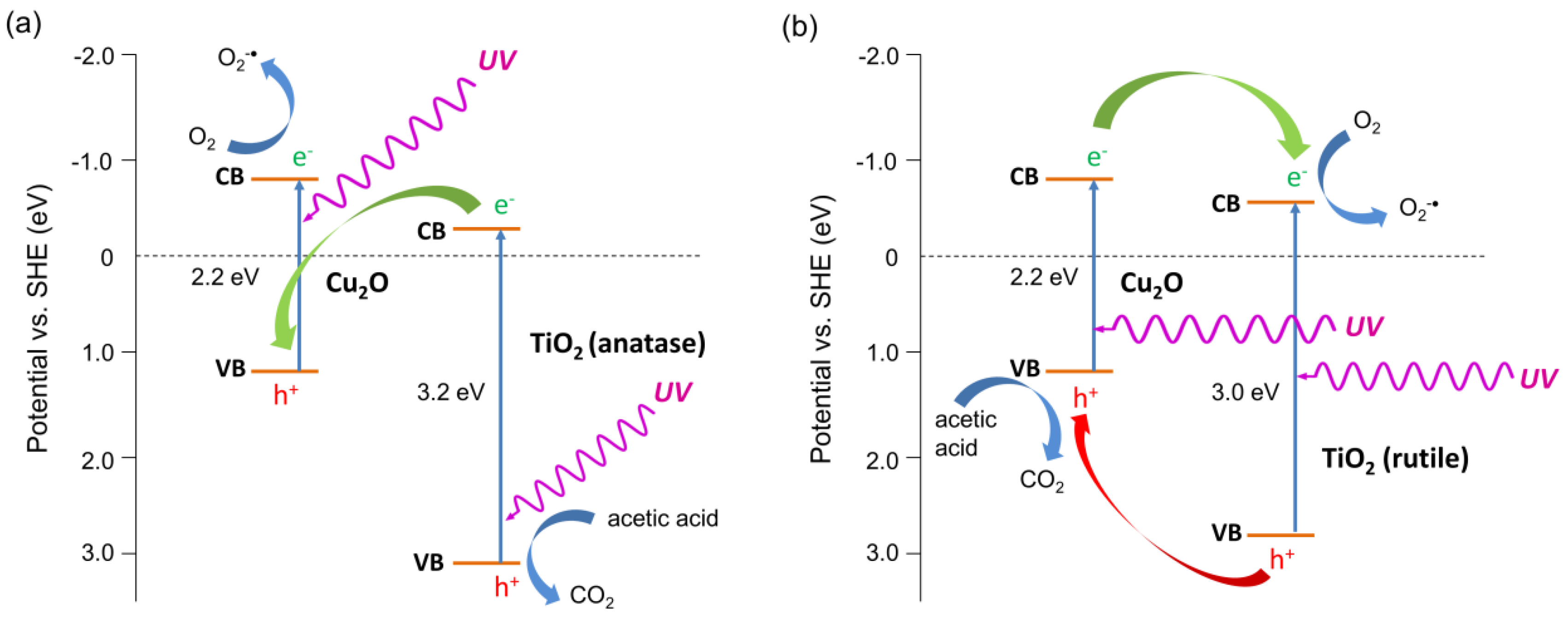

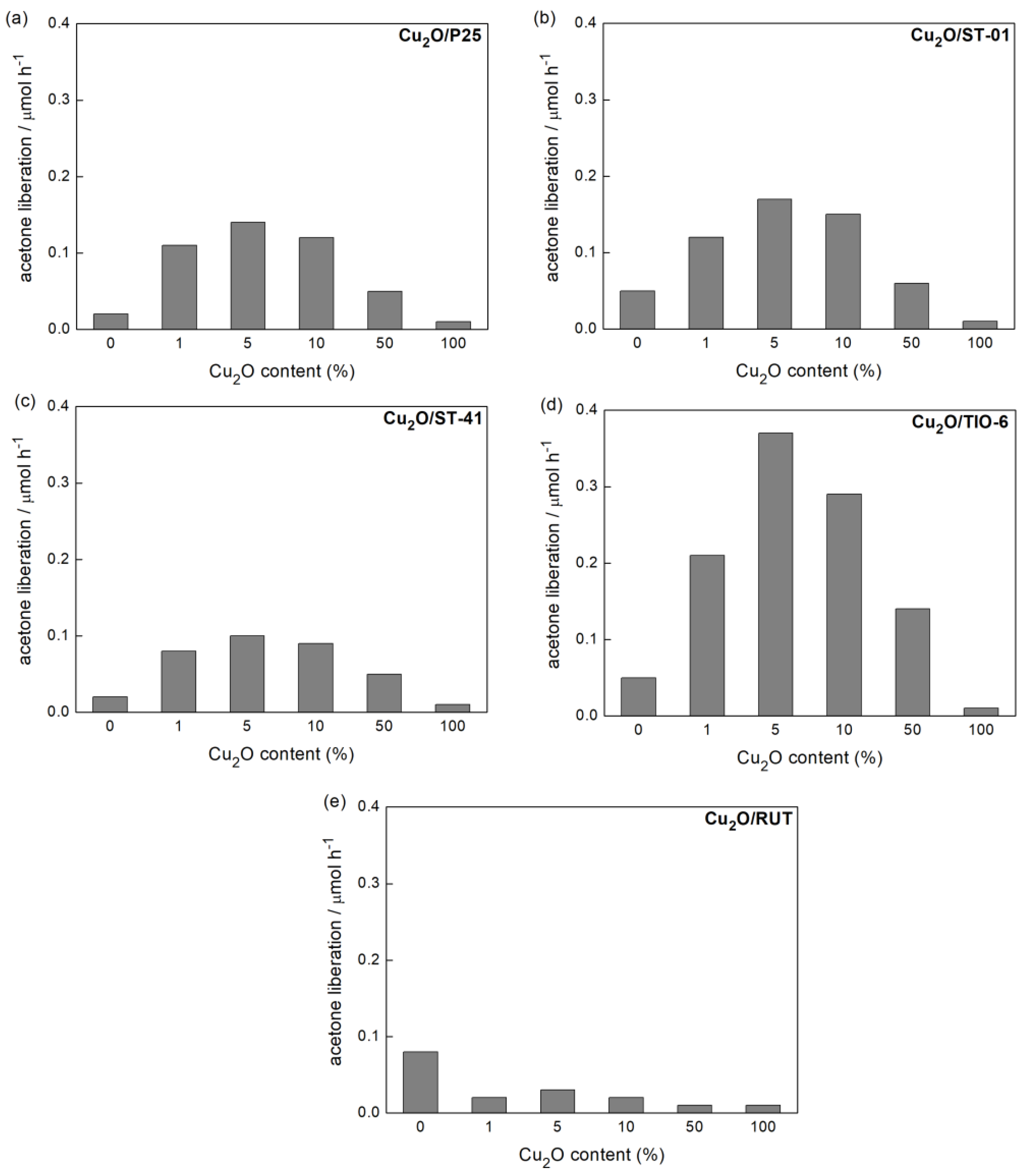

3.2.2. UV/Vis-Induced Acetic Acid Oxidation

3.2.3. Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity

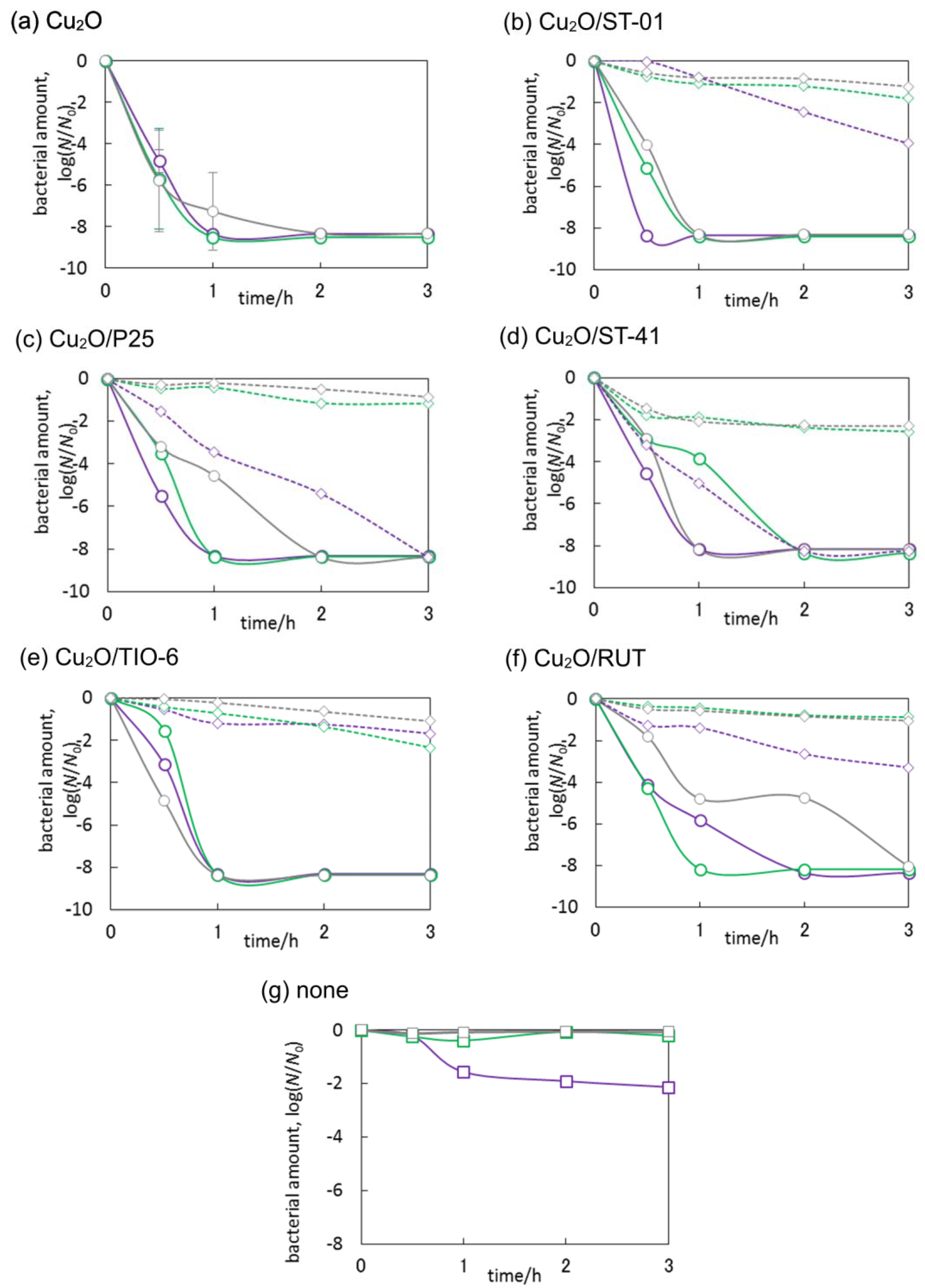

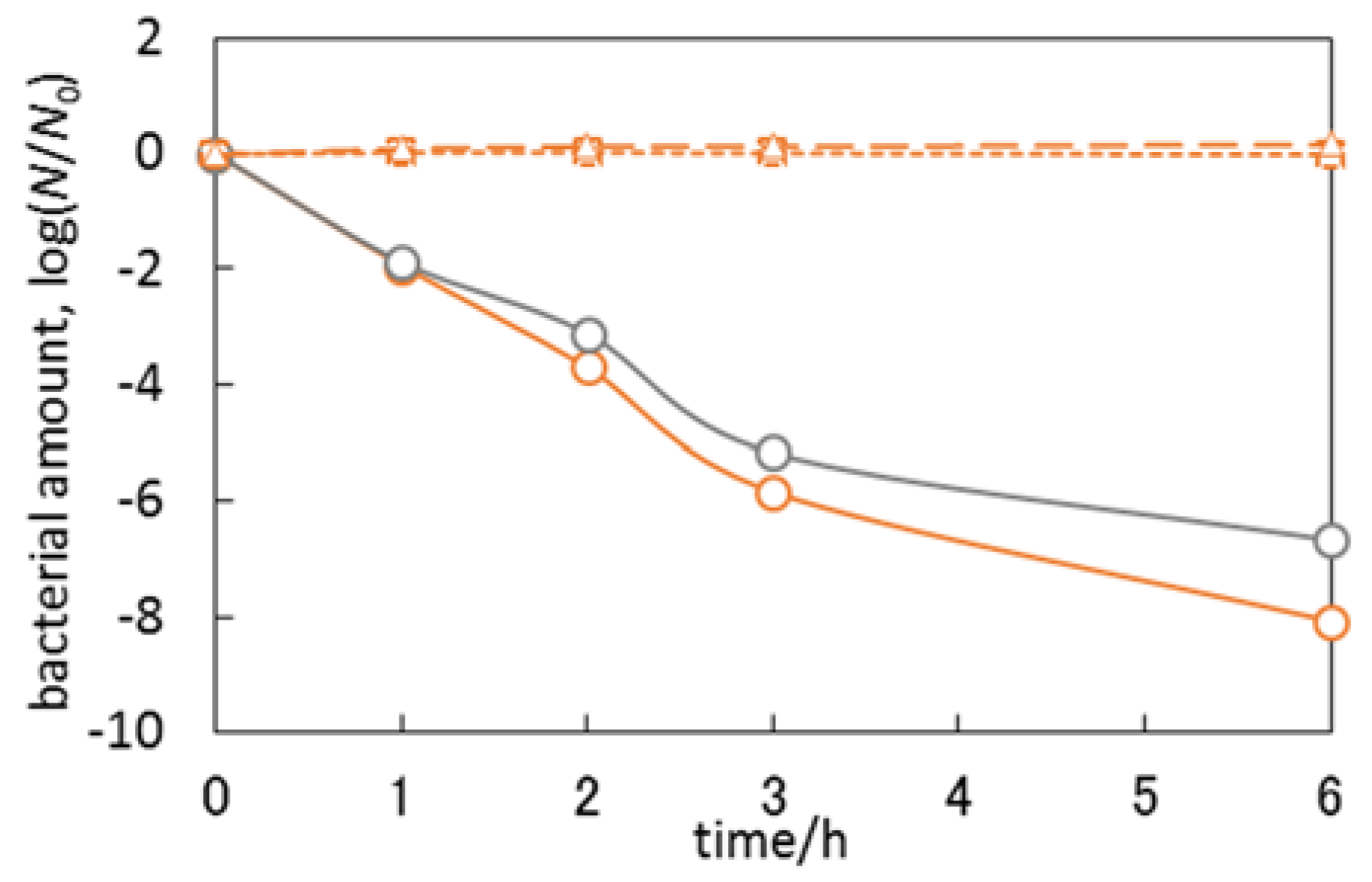

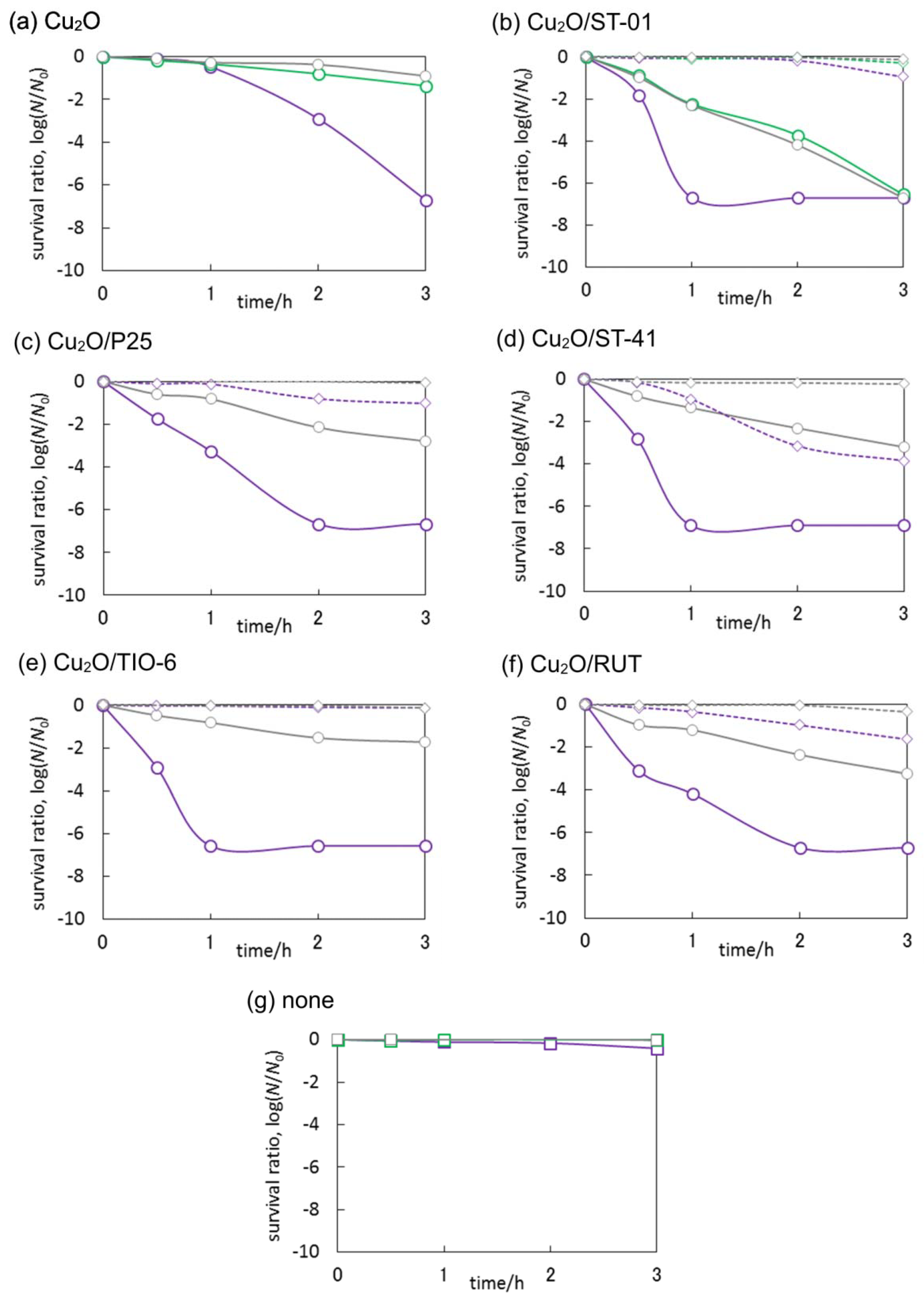

3.3. Antimicrobial Properties of Cu2O/TiO2

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bahnemann, D.W. Photocatalytic water treatment: Solar energy applications. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, B.; Ge, J.; Jia, X. Fabrication of ternary zinc cadmium sulfide photocatalysts with highly visible-light photocatalytic activity. Catal. Commun. 2010, 11, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Peng, B.S.; Peng, T.Y. Recent advances in heterogeneous photocatalytic CO2 conversion to solar fuels. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7485–7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahi, R.; Morikawa, T.; Ohwaki, T.; Aoki, K.; Taga, Y. Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides. Science 2001, 293, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Lopez-Puente, V.; Wang, Q.; Polavarapu, L.; Pastoriza-Santos, I.; Xu, Q.H. Plasmon-enhanced light harvesting: Applications in enhanced photocatalysis, photodynamic therapy and photovoltaics. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 29076–29097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, M.; Takatori, H.; Tada, H. Interfacial chemical bonding effect on the photocatalytic activity of TiO2–SiO2 nanocoupling systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 361, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martsinovich, N.; Troisi, A. How TiO2 crystallographic surfaces influence charge injection rates from a chemisorbed dye sensitiser. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 13392–13401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 photocatalysis: Mechanisms and materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisch, H. Semiconductor photocatalysis—Mechanistic and synthetic aspects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 812–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanushali, S.; Ghosh, P.; Ganesh, A.; Cheng, W.L. 1D copper nanostructures: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Small 2015, 11, 1232–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarizia, L.; Spasiano, D.; Di Somma, I.; Marotta, R.; Andreozzi, R.; Dionysiou, D.D. Copper modified-TiO2 catalysts for hydrogen generation through photoreforming of organics. A short review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 16812–16831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Endo, M.; Wang, K.; Charbit, E.; Markowska-Szczupak, A.; Ohtani, B.; Kowalska, E. Noble metal-modified octahedral anatase titania particles with enhanced activity for decomposition of chemical and microbiological pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 318, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janczarek, M.; Wei, Z.; Endo, M.; Ohtani, B.; Kowalska, E. Silver- and copper-modified decahedral anatase titania particles as visible light-responsive plasmonic photocatalyst. J. Photonics Energy 2017, 7, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Janczarek, M.; Endo, M.; Wang, K.; Balčytis, A.; Nitta, A.; Méndez-Medrano, G.; Colbeau-Justin, C.; Juodkazis, S.; Ohtani, B.; et al. Noble metal-modified faceted anatase titania photocatalysts: Octahedron versus decahedron. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 237, 547–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, M.; Kowalska, E. On the origin of enhanced photocatalytic activity of copper-modified titania in the oxidative reaction systems. Catalysts 2017, 7, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Medrano, M.G.; Kowalska, E.; Lehoux, A.; Herissan, A.; Ohtani, B.; Bahena, D.; Briois, V.; Colbeau-Justin, C.; Rodrigues-Lopez, J.L.; Remita, H. Surface modification of TiO2 with Ag nanoparticles and CuO nanoclusters for application in photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 5143–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSario, P.A.; Pietron, J.J.; Brintlinger, T.H.; McEntee, M.; Parker, J.F.; Baturina, O.; Stroud, R.M.; Rolison, D.R. Oxidation-stable plasmonic copper nanoparticles in photocatalytic TiO2 nanoarchitectures. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 11720–11729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Miyauchi, M.; Sunada, K.; Minoshima, M.; Liu, M.; Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Shimodaira, Y.; Hosogi, Y.; Kuroda, Y.; et al. Hybrid CuxO/TiO2 nanocomposites as risk-reduction materials in indoor environments. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.M.; Yang, W.Y.; Li, Q.; Gao, S.A.; Shang, J.K. Synthesis of Cu2O nanospheres decorated with TiO2 nanoislands, their enhanced photoactivity and stability under visible light illumination, and their post-illumination catalytic memory. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 5629–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.; Zheng, X.M.; Kong, F.; Wu, G.H.; Luo, L.L.; Guo, Y.; Liu, H.L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.X.; Zou, Z.G. Architecture of Cu2O@TiO2 core-shell heterojunction and photodegradation for 4-nitrophenol under simulated sunlight irradiation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 129, 1184–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessekhouad, Y.; Robert, D.; Weber, J.-V. Photocatalytic activity of Cu2O/TiO2, Bi2O3/TiO2 and ZnMn2O4/TiO2 heterojunctions. Catal. Today 2005, 101, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Luo, S.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Kang, Q.; Cai, Q. High efficient photocatalytic degradation of p-nitrophenol on a unique Cu2O/TiO2 p-n heterojunction network catalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7641–7646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, L.B.; Yang, F.; Yan, L.L.; Yan, N.N.; Yang, X.; Qiu, M.Q.; Yu, Y. Bifunctional photocatalysis of TiO2/Cu2O composite under visible light: Ti3+ in organic pollutant degradation and water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2011, 72, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gu, X.; Sun, C.; Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Gao, F.; Dong, L. In situ loading of ultra-small Cu2O particles on TiO2 nanosheets to enhance the visible-light photoactivity. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 6351–6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yang, W.; Sun, W.; Li, Q.; Shang, J.K. Creation of Cu2O@TiO2 composite photocatalysts with p−n heterojunctions formed on exposed Cu2O facets, their energy band alignment study, and their enhanced photocatalytic activity under illumination with visible light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Y.; Ji, G.B.; Liu, Y.S.; Gondal, M.A.; Chang, X.F. Cu2O/TiO2 heterostructure nanotube arrays prepared by an electrodeposition method exhibiting enhanced photocatalytic activity for CO2 reduction to methanol. Catal. Commun. 2014, 46, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, L.; Cai, J.; Xie, K.; Lin, C. p–n Heterojunction photoelectrodes composed of Cu2O-loaded TiO2 nanotube arrays with enhanced photoelectrochemical and photoelectrocatalytic activities. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Zheng, S.; Pan, F.; Wang, T. TiO2 Film/Cu2O microgrid heterojunction with photocatalytic activity under solar light irradiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 1, 2111–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, B.; Yang, S.; Fang, Y.; Peng, F. The influence of the electrodeposition potential on the morphology of Cu2O/TiO2 nanotube arrays and their visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 13866–13871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Peng, F.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Li, Z. Preparation and characterization of Cu2O/TiO2 nano–nano heterostructure photocatalysts. Catal. Commun. 2009, 10, 1839–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Peng, F.; Yu, H.; Wang, H. Preparation of cuprous oxides with different sizes and their behaviors of adsorption, visible-light driven photocatalysis and photocorrosion. Solid State Sci. 2009, 11, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Jampaiah, D.; Kandjani, A.E.; Sabri, Y.M.; Gaspera, E.D.; Reineck, P.; Judd, M.; Langley, J.; Cox, N.; Embden, J.; et al. Oxygen-deficient photostable Cu2O for enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 6039–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Xu, L.; Shi, W.; Guan, J. Facile preparation and size-dependent photocatalytic activity of Cu2O nanocrystals modified titania for hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.Y.; Yu, T.H.; Chao, K.J.; Lu, S.Y. Cu2O-decorated mesoporous TiO2 beads as a highly efficient photocatalyst for hydrogen production. ChemCatChem 2014, 6, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.H.; Li, C.J.; Zhang, L.; Xing, M.Y.; Zhang, J.L. Synergistic effect of Cu2O/TiO2 heterostructure nanoparticle and its high H2 evolution activity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 6345–6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Wang, B.W.; Liu, S.H.; Duan, X.F.; Hukey, Z.Y. Synthesis and characterization of Cu2O/TiO2 photocatalysts for H2 evolution from aqueous solution with different scavengers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 324, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.P.; Reddy, N.L.; Kumari, M.M.; Srinivas, B.; Kumari, V.D.; Sreedhar, B.; Roddatis, V.; Bondarchuk, O.; Karthik, M.; Neppolian, B.; et al. Cu2O-sensitized TiO2 nanorods with nanocavities for highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production under solar irradiation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 136, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalitha, K.; Sadanandam, G.; Kumari, V.D.; Subrahmanyam, M.; Sreedhar, B.; Hebalkar, N.Y. Highly stabilized and finely dispersed Cu2O/TiO2: A promising visible sensitive photocatalyst for continuous production of hydrogen from glycerol:water mixtures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 22181–22189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senevirathna, M.K.I.; Pitigala, P.K.D.D.P.; Tennakone, K. Water photoreduction with Cu2O quantum dots on TiO2 nano-particles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2005, 171, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunada, K.; Minoshima, M.; Hashimoto, K. Highly efficient antiviral and antibacterial activities of solid-state cuprous compounds. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 235, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.H.; Gong, J.L.; Zeng, G.M.; Zhang, P.; Song, B.; Zhang, X.G.; Liu, H.Y.; Huan, S.Y. Graphene sponge decorated with copper nanoparticles as a novel bactericidal filter for inactivation of Escherichia coli. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankovich, T.A.; Smith, J.A. Incorporation of copper nanoparticles into paper for point-of-use water purification. Water Res. 2014, 63, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, J.; Hai, Y.; Jaroniec, M. Photocatalytic hydrogen production over CuO-modified titania. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 357, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dozzi, M.V.; Chiarello, G.L.; Pedroni, M.; Livraghi, S.; Giamello, E.; Selli, E. High photocatalytic hydrogen production on Cu (II) pre-grafted Pt/TiO2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 209, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchalska, M.; Kobielusz, M.; Matuszek, A.; Pacia, M.; Wojtyla, S.; Macyk, W. On oxygen activation at rutile- and anatase-TiO2. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 7424–7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, D.O.; Dunnill, C.W.; Buckeridge, J.; Shevlin, S.A.; Logsdail, A.J.; Woodley, S.M.; Catlow, C.R.A.; Powell, M.J.; Palgrave, R.G.; Parkin, I.P.; et al. Band alignment of rutile and anatase TiO2. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, Z.; El Kolli, N.; Uribe, D.B.; Beaunier, P.; Jose-Yacaman, M.; Vigneron, J.; Etcheberry, A.; Sorgues, S.; Colbeau-Justin, C.; Chen, J.; et al. Modification of TiO2 by bimetallic Au–Cu nanoparticles for wastewater treatment. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 10829–10835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.H.; Liu, J.W.; Wang, D.J.; Gao, Y.; Shen, J. Cu2O/Cu/TiO2 nanotube Ohmic heterojunction arrays with enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production activity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 6431–6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, A.D.; Tang, J. Controllable proton and CO2 photoreduction over Cu2O with various morphologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 13017–13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, M.; Kowalska, E.; Ohtani, B. Decahedral-shaped anatase titania photocatalyst particles: Synthesis in a newly developed coaxial-flow gas-phase reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 289, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, Y.; Polavarapu, L.; Gao, N.; Yuan, P.; Sow, C.H.; Hu, Q.H. Plasmon-enhanced photocatalytic properties of Cu2O nanowire–Au nanoparticle assemblies. Langmuir 2012, 28, 12304–12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpone, N.; Maruthamuthu, P.; Pichat, P.; Pelizzetti, E.; Hidaka, H. Exploiting the interparticle electron transfer process in the photocatalysed oxidation of phenol, 2-chlorophenol and pentachlorophenol: Chemical evidence for electron and hole transfer between coupled semiconductors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1995, 85, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Mahaney, O.O.; Murakami, N.; Abe, R.; Ohtani, B. Correlation between photocatalytic activities and structural and physical properties of titanium(IV) oxide powders. Chem. Lett. 2009, 38, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, E.; Prieto Mahaney, O.O.; Abe, R.; Ohtani, B. Visible-light-induced photocatalysis through surface plasmon excitation of gold on titania surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 2344–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghriche, O.; Rtimi, S.; Pulgarin, C.; Sanjines, R.; Kiwi, J. Innovative TiO2/Cu nanosurfaces inactivating bacteria in the minute range under low-intensity actinic light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 5234–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; O’Shea, P. The electrostatic nature of the cell surface of Candida albicans: A role in adhesion. Exp. Mycol. 1994, 18, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danmek, K.; Intawicha, P.; Thana, S.; Sorachakula, C.; Meijer, M.; Samson, R.A. Characterization of cellulase producing from Aspergillus melleus by solid state fermentation using maize crop residues. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 8, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar]

| Sample Name | Anatase * (%) | Rutile * (%) | Crystallite Size/nm | Specific Surface Area/m2·g−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatase | Rutile | ||||

| P25 | 83.8 | 16.2 | 21 | 37 | 59 |

| ST-01 | 100 | - | 8 | - | 298 |

| ST-41 | 98.3 | 1.7 | 70 | 124 | 11 |

| TIO-6 | - | 100 | - | 16 | 105 |

| RUT | 1.7 | 98.3 | 55 | 82 | 4 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janczarek, M.; Endo, M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, K.; Kowalska, E. Enhanced Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Performance of Cuprous Oxide/Titania: The Effect of Titania Matrix. Materials 2018, 11, 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11112069

Janczarek M, Endo M, Zhang D, Wang K, Kowalska E. Enhanced Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Performance of Cuprous Oxide/Titania: The Effect of Titania Matrix. Materials. 2018; 11(11):2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11112069

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanczarek, Marcin, Maya Endo, Dong Zhang, Kunlei Wang, and Ewa Kowalska. 2018. "Enhanced Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Performance of Cuprous Oxide/Titania: The Effect of Titania Matrix" Materials 11, no. 11: 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11112069