1. Introduction

For more than a decade carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been considered as a fundamental focus of nanotechnology, thanks to their outstanding physical and electrical properties, which are strongly dependent on their chirality and curvature [

1,

2,

3]. These nanostructures have attracted a great attention also for their exceptional chemical stability. The latter has been widely investigated not only for biomedical purposes [

4], where CNTs have been considered ideal nanocapsules for the encapsulation of specific nanomedicine contrast agents [

4], but also for numerous magnetic applications involving the encapsulation of a ferromagnetic material inside the carbon nanotube core [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The high chemical stability of CNTs ensures a complete protection of the encapsulated ferromagnet from the external environment and allows retaining the magnetic properties for long timescales. In this context, α-Fe and Fe

3C have been widely studied owing to their promising magnetic properties, with high and tuneable saturation magnetizations and large coercivities [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These nanostructures are generally grown by chemical vapour deposition (CVD) of a metallocene (ferrocene) at high temperatures (approximately 1000 °C) in the form of vertically oriented films [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Despite the numerous reports on the control of the ferromagnetic filling rates of these vertically oriented nanostructures, one of the major problems that limit their translation into magnetic devices is the high brittleness. Indeed, CNTs-films produced using only ferrocene are generally very fragile, due to the low number of Van der Waals interactions and other imperfections in the vertical alignment. Recent works have shown that the stability of these structures can be improved through the addition of Cl-containing hydrocarbons, which allow the synthesis of CNTs-films with a higher number of Van der Waals interactions and less imperfections in the vertical alignment [

13].

Despite the vast amount of work, the production of these nanostructures in large scale remains still challenging and strongly depends on the used substrate, on the evaporation temperatures of the precursors and on the chosen surface of growth [

13]. Interestingly, recent reports have shown that another type of Fe-filled CNTs film, known as buckypaper, can comprise Fe-filled CNTs in the form of randomly entangled or horizontally aligned structures [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This type of film is generally synthesized directly in situ by CVD of ferrocene/dichlorobenzene or trichlorobenzene mixtures and can exhibit excellent magnetic properties and high elasticity [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Recent reports have shown that the morphology of these structures strongly depend on the used vapour flow rates, as well as on the chosen dichlorobenzene or trichlorobenzene concentration [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The excellent magnetic properties of these structures show a great promise for applications in electromagnetic devices, as well as in microwave absorption and aerospace technology [

14].

However, some major challenges based on the control of purity and reaction efficiency remain. Indeed it has been shown that buckypapers grown in presence of Cl radicals at low evaporation temperatures generally present an unusual surface crust comprising empty and filled carbon nano-onions (CNOs) [

13,

14]. The presence of such an unusual crust therefore requires additional purification treatments that limit a direct use of this approach for industrial buckypaper production. In addition, the necessity of accurately control the concentration of dichlorobenzene in order to avoid the formation of metal chlorides represents a challenge limiting the growth of these nanostructures to only low precursor-evaporation temperatures and low Cl-concentrations [

13,

14,

21]. Minimizing the quantities of dichlorobenzene could be considered a necessary step toward the large scale production of these types of carbon nanotubes films. New solutions are necessary for higher precursor-evaporation temperatures that are required for the future encapsulation of specific hard magnet alloys such as FePt, CoPt, Fe

5Sm, and Co

5Sm in buckypaper structures, given the high evaporation temperatures of the metal-containing metallocene-like precursors [

22]. Up to now, high evaporation temperatures in the order of 200 °C can be used only for the production of vertically aligned CNTs structures, but not for the production of buckypapers [

13].

In this context, the possible use of alternative supported-catalysts could be useful for promoting the growth of these nanostructured-films in a large scale. It has been shown that highly porous and high surface area matrices such as mesoporous ordered silicas can be considered as ideal candidates as support for nanoparticles to be used as catalysts for CNTs production [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. These types of supported catalysts can allow for the synthesis of CNTs with a uniform diameter distribution, since the dimensions of the catalyst-nanoparticles are comparable to those of the mesoporous-silica pores. In particular, the so called SBA-16, which has a cubic arrangement of pores characterized by a body centered cubic symmetry (space group

Im-3

m) has attracted much attention [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], which stems from the spherical empty cages, with each cage connected to eight neighbouring one by narrow openings forming a 3D network of mesopores. Despite these promising characteristics, this type of supported catalysts has not yet been considered for promoting the growth of ferromagnetically filled CNTs buckypapers.

In this work, we demonstrate that SBA-16 can have a crucial role in the fabrication of large-scale ferromagnetically filled buckypapers by favoring the growth of CNTs on a horizontal plane with random orientation rather than in a vertical direction. SBA-16 can therefore be considered not only as secondary catalyst source since it acts as catalyst support on the substrate surface but also as growth-inhibitor, since it can prevent the growth of CNTs in the form of vertically oriented films. The morphology and composition of the obtained CNTs-buckypapers was analyzed in detail by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high resolution TEM (HRTEM), and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). Structural investigation of the buckypapers was performed by Rietveld Refinement methods of X-ray diffraction (XRD) data. The magnetic properties of the produced buckypapers were also analysed by vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) at room temperature. Additionally, the electrochemical performances of these buckypapers are demonstrated and reveal a behavior that is compatible with that of a pseudo-capacitor with better performances than those presented in other previously studied layered-buckypapers of Fe-filled CNTs.

3. Results and Discussion

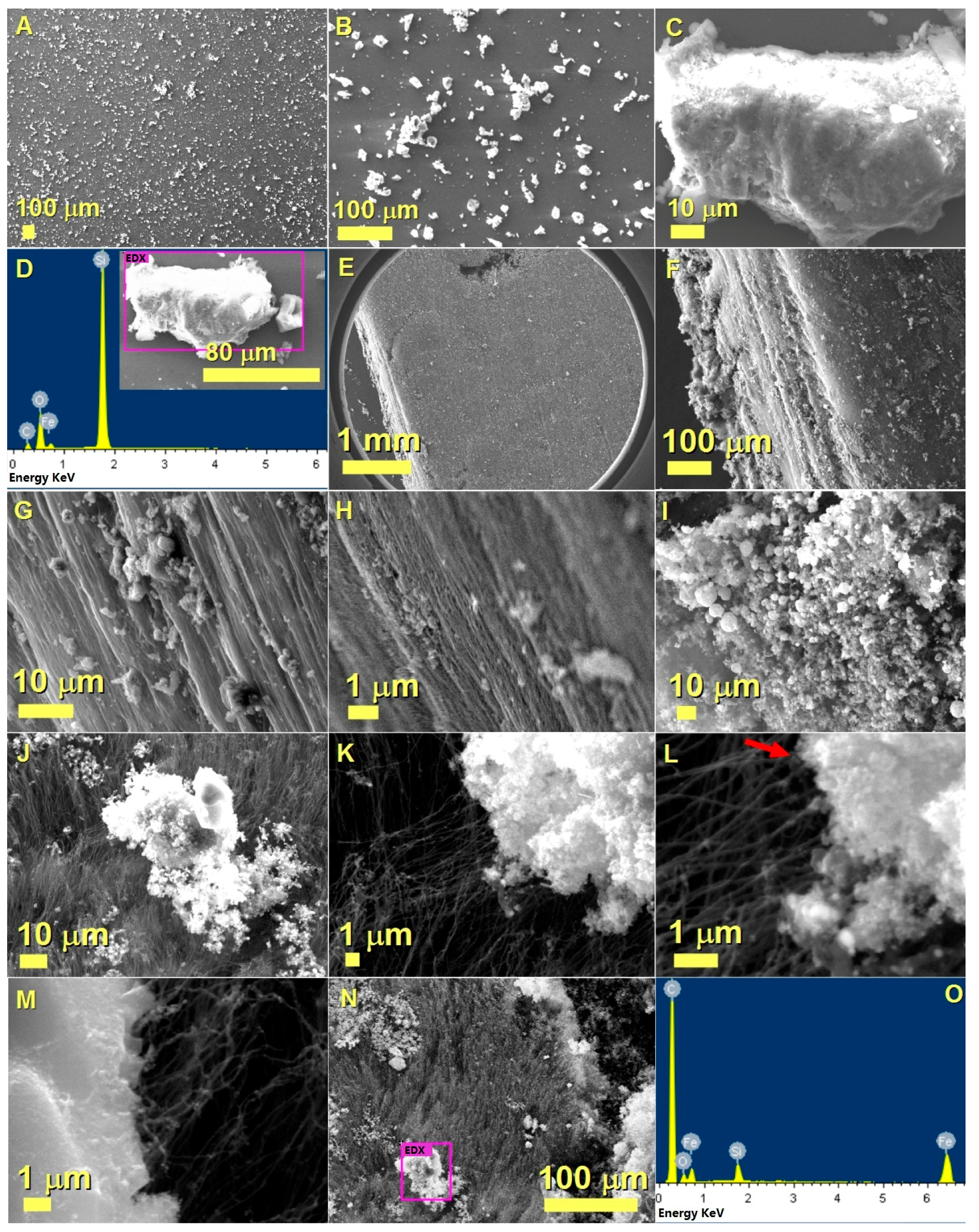

The morphology of the as prepared substrate after spin-coating of FeSm/SBA-16 has been investigated by SEM, and the results are shown in

Figure 1. As shown in

Figure 1A,B, the catalyst supported on mesoporous silica appears to be uniformly distributed on the top of the Si substrate surface in the form of flakes. A higher magnification detail of a micrometre-size flake is shown in the image of

Figure 1C. Typical EDX spectrum of the area displayed in

Figure 1C is shown in

Figure 1D (see also inset), which provided the following amounts of the elements present: 17.43 wt % of C, 31.85 wt % of O, 32.94 wt % of Si, and 17.78 wt % of Fe, corresponding to 29.42 at % of C, 40.36 at % of O, 23.77 at % of Si, and 6.45 at % of Fe. These results indicate that Fe-containing species are present within the SBA-16 flakes, while no Sm could be detected due to the very low quantities used in the synthesis-method described above.

The SEM morphological analysis performed on the as grown buckypaper after CVD are shown in

Figure 1E–H. The cm-scale dimensions of the buckypaper were confirmed by the SEM image at low magnification (see

Figure 1E). Further images of the buckypaper-cross-section obtained with an increasing magnification in

Figure 1F–H revealed the thickness of the buckypaper in the order of approximately 290 μm. The buckypaper appears to be arranged in a layered like morphology, with each CNT-layer characterized by a random CNTs orientation in the horizontal plane. Note that as shown in

Figure 1I–J, the catalyst particles together with the SBA-16 support were found on the top-surface of the analysed buckypaper. Analysis of this area at higher magnification revealed the presence a direct connection between the growing CNTs and the SBA-16 catalyst support. Such direct connection can be clearly observed in different regions of the analysed SBA-16 flake, as indicated in

Figure 1K–M and in

Figure 1L by the red arrow.

Such direct connection between the grown CNTs and the supported catalyst suggests that SBA-16 has crucial role in driving the buckypaper growth by inhibiting the formation of vertically aligned CNTs, and instead favouring the formation of CNTs in the horizontal plane with random x-y directions in a spider-web like arrangement. In addition, the presence of SBA-16 on the top-region of the buckypaper suggests that after the first layer-growth is initiated, the other layers may grow one by one underneath the first one in a lift-up mechanism [

21]. Note also that no onion-crust if found in the buckypaper-surface shown in

Figure 1E,F. This suggests that the buckypapers produced in this work have a higher purity with respect to those reported in previous reports [

13,

14,

21].

The presence of Si and O, together with Fe was confirmed by the EDX spectrum, shown in

Figure 1O, derived from the region of the SBA-16 flake (

Figure 1N). Instead, Sm could be detected only in separated regions in the form of micrometre sized particles, as highlighted in the following. Further characterization of the produced buckypaper was obtained using X-ray diffraction. In particular, the XRD pattern obtained from the analysed buckypaper is shown in

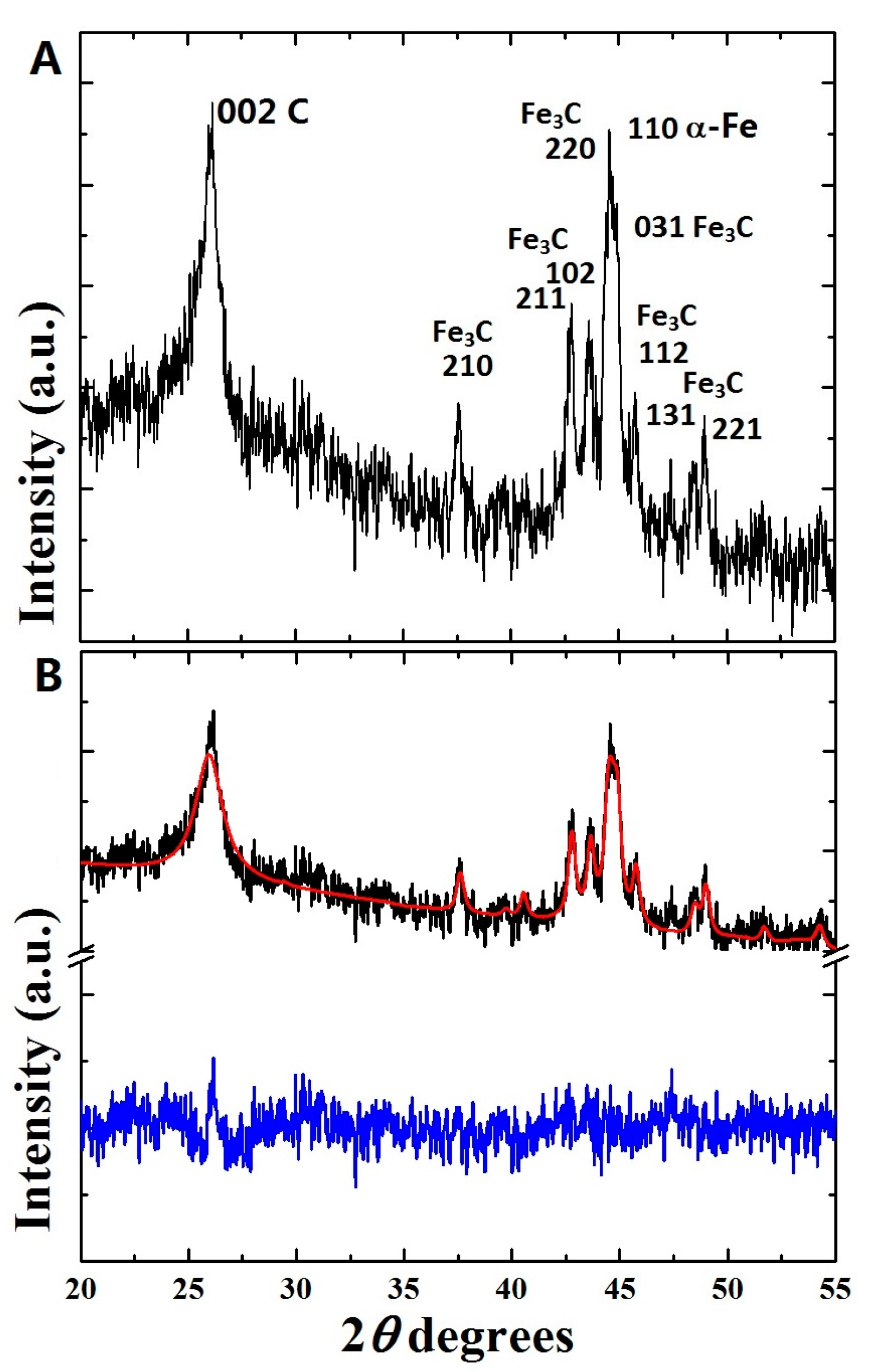

Figure 2.

Interestingly, together with the 002 reflection arising from the CNTs-walls contribution, the 210, 211, 102, 220, 031, 112, 131, and 221 reflections due to the presence of Fe3C and an intense 110 reflection due to the presence of α-Fe were also detected. Instead, no clear reflection due to the γ-Fe phase was observed. Moreover, no peak is found due to Sm, which might be present in an amorphous phase. An amorphous halo detectable in the region of 25 degrees 2θ can be attributed to the presence of SBA-16 in the buckypaper.

The Rietveld method, which uses the least-squares approach to match a theoretical line profile to the diffraction pattern, was used to gather further information, such as identify and estimate the relative abundances of the phases present in the ferromagnetically filled CNTs buckypaper. As shown in

Figure 2B, the Rietveld refinement confirmed the interpretation above with the following relative abundances of carbon (78.1%), α-Fe (2.5%), and Fe

3C (19.3%). Furthermore, the following unit cell parameters were derived as follows: for Fe

3C with space group Pnma a: 0.511 nm, b: 0.676 nm, c: 0.454 nm; for α-Fe with space group

Im-3

m a = b = c: 0.287 nm; for the carbon CNTs-walls graphitic contribution: a = b: 0.246 nm and c: 0.687 nm.

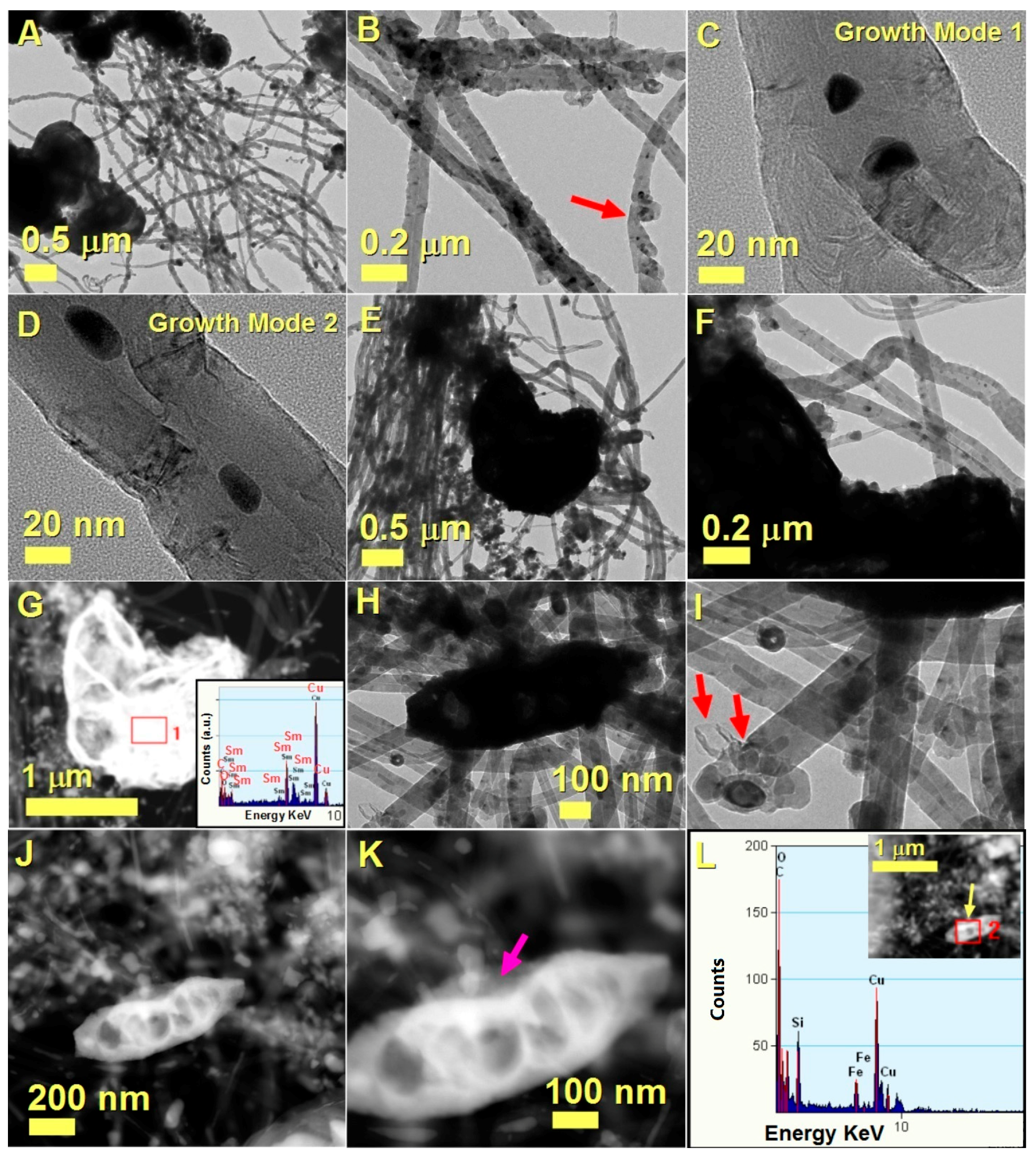

The characterization of the CNTs present within the buckypaper was carried out by TEM, HRTEM and STEM/EDX, as shown in

Figure 3. As shown in

Figure 3A the analysed CNTs were found to be connected with micrometre-scale agglomerations of spherically encapsulated Fe-based catalyst particles.

The presence of these particles can be considered a consequence of the in situ reduction of SBA-16 supported catalyst induced by the presence of high concentrations of hydrogen coming from the pyrolysed metallocene/dichlorobenzene vapours. Further analysis of the cross-sectional CNTs morphology also revealed the presence of two main growth mechanism (growth modes). A growth mode 1, in which the CNTs appear to grow in bamboo-like arrangement [

30,

31,

32] (see red arrow in

Figure 3B and HRTEM image in

Figure 3C) and a growth mode 2 (see HRTEM image in

Figure 3D), in which the CNTs appear to grow in a catalyst-pool like mechanism [

13,

14,

32]. Note that in bamboo-like growth mechanisms, CNTs are generally characterized by the periodical repetition of closed compartments. Instead in the catalyst pool mechanism the presence of graphene caps is generally a consequence of the melted status of the catalyst particle during the CNTs growth and is indicative of the growth direction (the graphene cap is generally oriented toward the growth direction of the CNT) [

13]. In addition, cross sectional EDX investigation in STEM mode allowed us to detect the presence of Sm in unusual thick micrometre size particles, as highlighted in the example shown in

Figure 3G and in the inset reporting the EDX spectrum. Due to the high thickness, the information could not be obtained from the TEM and HRTEM images (

Figure 3E,F). Instead, the EDX analysis in STEM mode revealed the compositional characteristics. Note that the high brightness is associated to the high Sm content within the particle. Curiously, the EDX spectrum did not evidence the presence of Fe within the particle, indicating that Fe and Sm did not alloy during the in situ reduction in the CVD process. In addition, the presence of oxygen suggests that an amorphous Sm

2O

3 phase is probably formed by exposure of the catalyst to air after the CVD experiment.

Further TEM images shown in

Figure 3H,I also allowed for the direct observation of the cross-sectional morphology of the post-CVD SBA-16 matrix. A flake of SBA-16 with a platelet-like arrangement was found to be connected with numerous CNTs. An example of CNT detached from the flake is shown in

Figure 3H,I. Note that many onion-like particles are connected to the CNT-base, however the nucleation of the CNTs appears to start from a not-encapsulated particle, as indicated by the red arrows. Further analysis of this area of the sample in STEM mode (see

Figure 3J,K) also allowed for the observation of a CNT directly connected to the silica-based SBA-16 support. Note that, as shown in

Figure 3K by the magenta arrow, the nucleation of the CNT appears to initiate directly from the SBA-16, which, as expected, is found to contain both silicon and oxygen (see compositional analyses in

Figure 3L and area of analysis in

Figure 3L-inset). These observations confirm the key role that SBA-16 plays in controlling the nucleation dynamics of the filled-CNTs in the buckypaper.

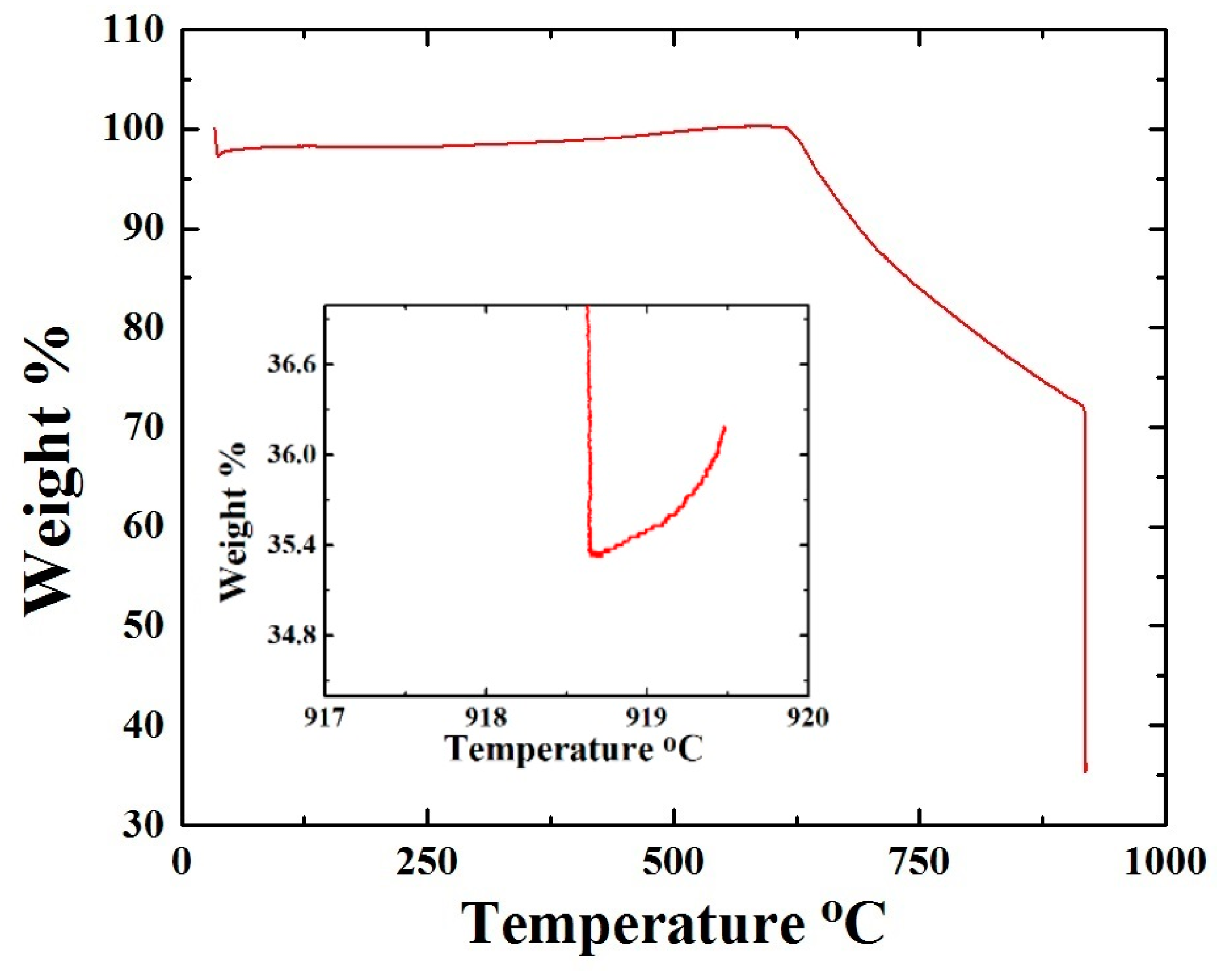

Further information on the composition of the grown buckypaper was obtained by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) under N

2, which was done in two steps: in step 1, temperature was increased up to approximately 919 °C, and, in step 2, the temperature was kept constant until complete decomposition. As shown in

Figure 4, the results revealed the presence of approximately 64.6% of carbon, which could be attributed to the graphitic structure of the CNTs and 36.4% of metal, which can be attributed to both the Sm-based and Fe-based species within the buckypaper.

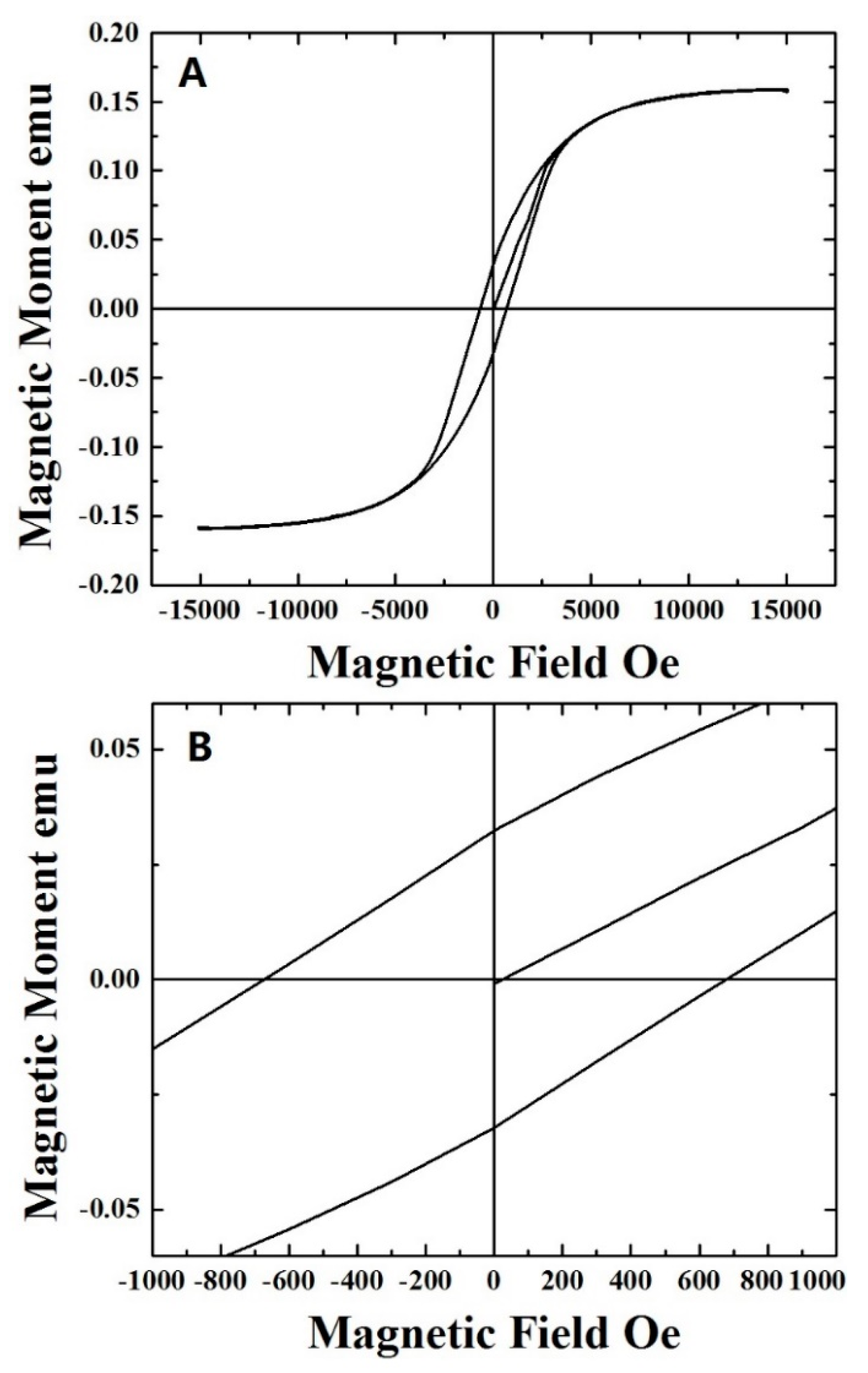

In order to measure the coercivity associated with the buckypaper the magnetic properties were measured at 300 K. As shown in

Figure 5, a typical ferromatignetic-like behavior was found. A high coercivity, in the order of 650 Oe, was determined which is higher with respect to the values given in previous reports on cm-scale buckypapers filled with Fe

3C [

14,

21]. Also, the observed coercivity is higher with respect to that of approximately 200 Oe reported by Rossella et al. [

33] in the case of template grown cobalt cluster-filled CNTs arrays. The observed coercivity is however lower with respect to the values recently found in the case of other type of buckypaper morphologies filled with Fe crystals, due to the absence of geometry-induced exchange coupled interactions presented in that work [

21]. Note also that the absence of γ-Fe in our sample also implies the absence of low-temperature antiferromagnetic phenomena. The magnetic properties are therefore much different with respect to those reported by Sahoo et al. in the case of antiferromagnetic Co

3O

4 nanoparticles [

34].

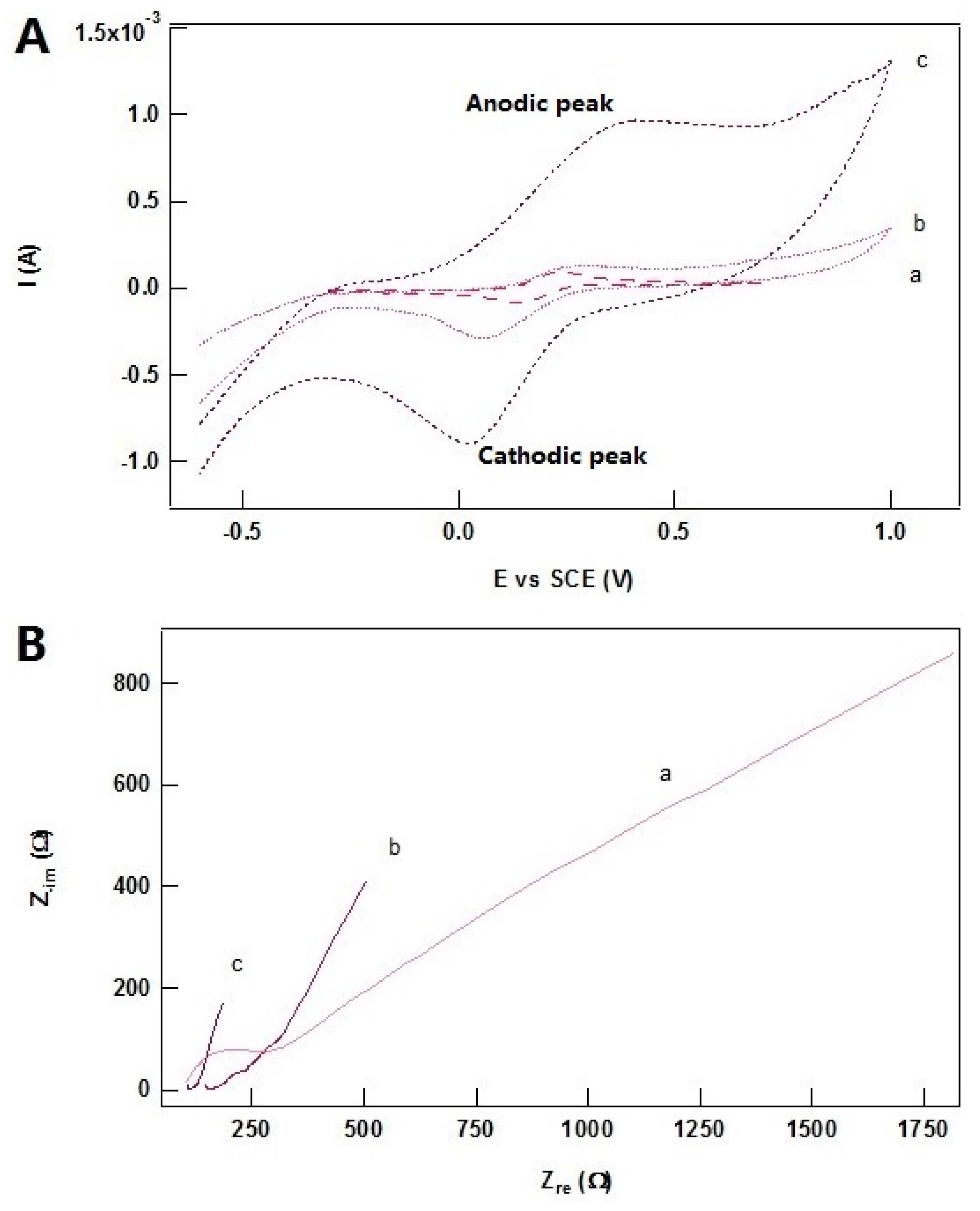

The electrochemical properties of Fe

3C/CNTs buckypapers produced in this work were then investigated by cyclic voltammetry (CV), at a scan rate of 50 mV using the K

3[Fe(CN)

6]/K

4[Fe(CN)

6] redox probe. In these measurements the properties of this buckypaper were compared to those of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE), and to those of another type of buckypaper obtained with the synthesis method in reference [

21], and consisting of a layered structure comprising both Fe filled carbon nano-onions, (layer 1) and randomly oriented CNTs filled with α-,γ-Fe (layer 2). As can be seen in

Figure 6, a significant peak current increase (

Ip) was observed for Fe

3C/CNTs (curve c) in comparison to GCE and the other buckypaper (curve a and b). This phenomenon can be attributed to the possible intrinsic differences in (1) the structural arrangement of the buckypapers, and (2) the active surface areas in comparison to unmodified GCE. In particular, in the case of the buckypaper presented in this work (Fe

3C-CNTs in

Figure 6) the presence of a significant quantity of Sm particles on the top surface could possibly function as active sites for the electrochemical processes.

Moreover, a well visible shift of cathodic and anodic peaks (

Figure 6A) with the peak potential (Δ

Ep) separation of 214 and 387 mV for CNOs/α-,γ-Fe/CNTs, and Fe

3C/CNTs buckypapers, respectively, can be noticed. The increase of peaks potentials separation indicates the absence of catalytic properties toward carried out electrochemical reaction. Interestingly, the cyclic voltammogram of Fe

3C/CNTs possess a rectangular-like shape, demonstrating an electrochemical pseudo-capacitance behavior (resistive-capacitor), which is further investigated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) technique (

Figure 6B). Most likely, this current is related to the charging of the double layer capacitance. Characteristic values obtained from CV measurements are collected in

Table 1.

Accordingly, the EIS measurements were performed for the GC, CNOs-CNTs buckypaper, and Fe

3C/CNTs buckypaper electrodes using the K

3[Fe(CN)

6]/K

4[Fe(CN)

6] redox probe in the presence of KCl.

Figure 6B shows Nyquist plots of examined electrodes, where

Zre is the real part and

Z-im is the imaginary part of the complex impedance

Z. Line (a) shown in

Figure 6B, corresponds to EIS results obtained for unmodified GCE, where the semicircle diameter at higher frequencies corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (

Rct), which controls the electron transfer kinetics of K

3[Fe(CN)

6]/K

4[Fe(CN)

6] at the electrode/electrolyte interface, meanwhile the resistance in the high frequency range (

Re) is the resistance of the electrolyte, the contacts, and connections. The straight line is the impedance due to the mass transfer of the redox species to the electrode, described by Warburg. As can be seen, the EIS of the bare GCE is composed of a semi-circle and a straight line featuring a diffusion limiting step of the K

3[Fe(CN)

6]/K

4[Fe(CN)

6] probe.

In the case of the CNOs-CNTs buckypaper and Fe

3C/CNTs buckypaper electrodes (

Figure 6B, line b and c), the electron transfer kinetics of the redox probe becomes fast so that the semi-circle disappears and forms almost a straight line. The decrease of the charge transfer resistance is due to the higher electron transfer kinetics at the buckypaper/electrolyte interface, and is in agreement with CV results. A presence of a “knee-like” feature (

Figure 6B, line b) can be observed in the Nyquist impedance plot for the CNOs-CNTs buckypaper electrode, which can be attributed to its complex structure characterized by two horizontal layers, of which the first one is composed of filled carbon CNOs structures and the second of randomly oriented CNTs. In the case of Fe

3C/CNTs buckypaper (

Figure 6B, line c) its impedance shows slight change, where the line is approaching the imaginary axis (

R-im) in the low frequency region pointing out on the capacitive-like behaviour of the material. Due to our considerations, the enhanced capacitive properties of the Fe

3C/CNTs buckypaper electrode, in comparison to that of CNOs-CNTs, can be assigned to the contribution from both the higher surface area of thicker CNTs layer, as well as to Fe and Sm catalyst particles present on the material layers and surface (for more details see EDX and SEM materials characterization). As it has been shown, the Fe particles not only act as a catalyst for the CNTs growth but at the same time contribute as the Fe

3C/CNTs buckypaper modifier, which allow to achieve an enhanced capacitive behavior (together with the Sm particles) of the Fe

3C/CNTs based material presented in this study. Furthermore, a slight deviation of the Nyquist plot from a straight line in the high frequency region is most probably attributed to charging processes of Fe

3C/CNTs electrode.