Data-Driven Site Selection Based on CO2 Injectivity in the San Juan Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

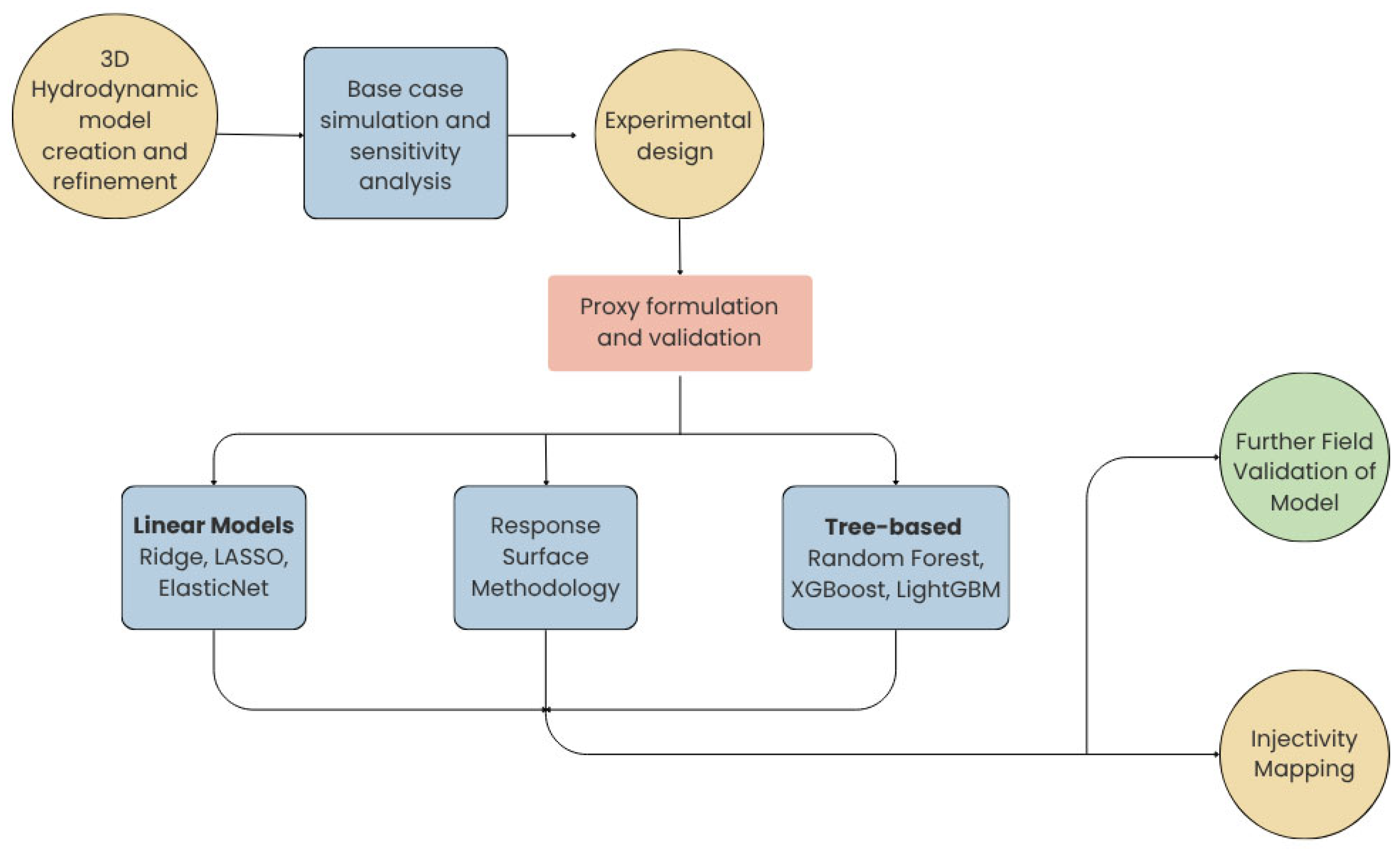

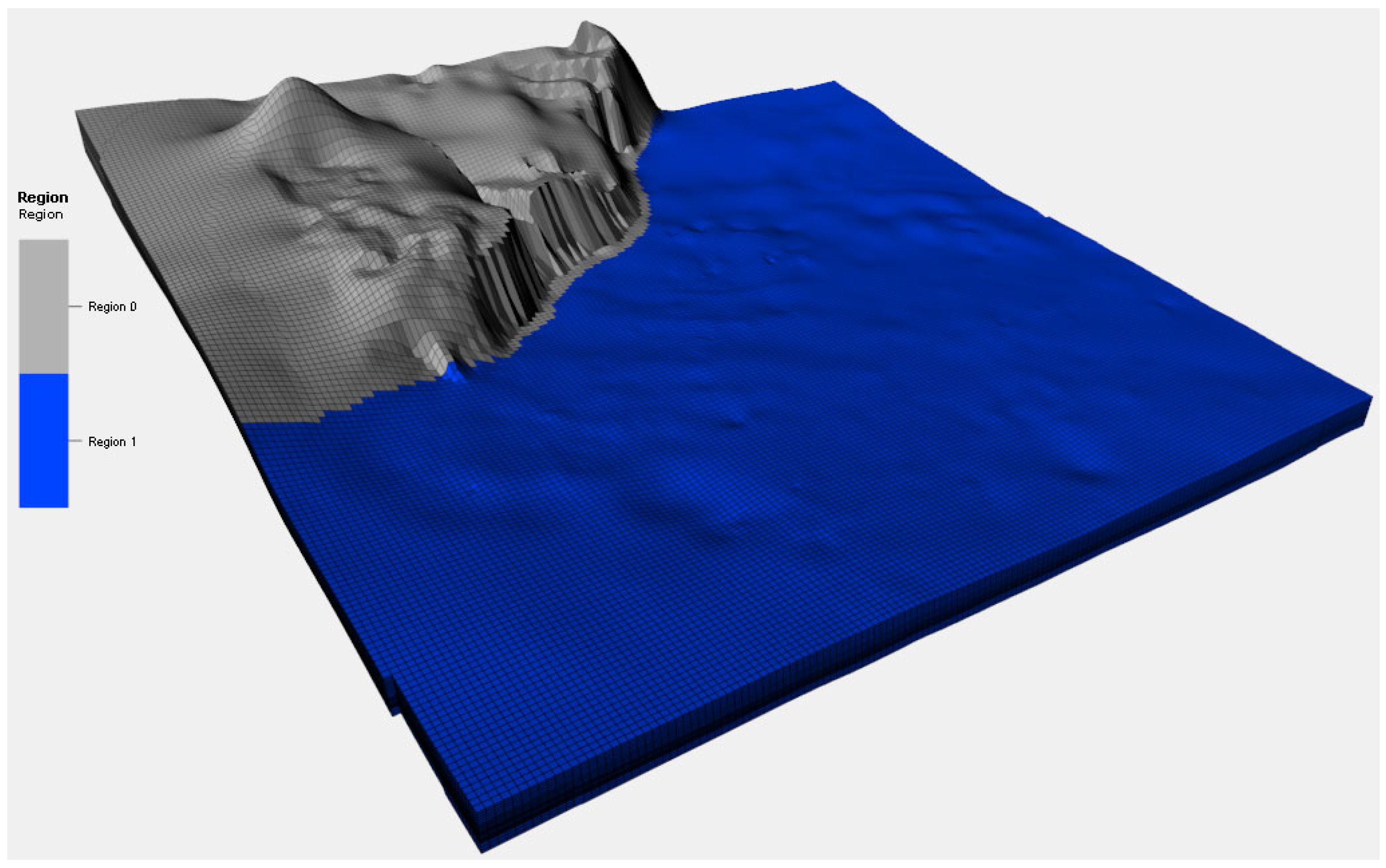

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

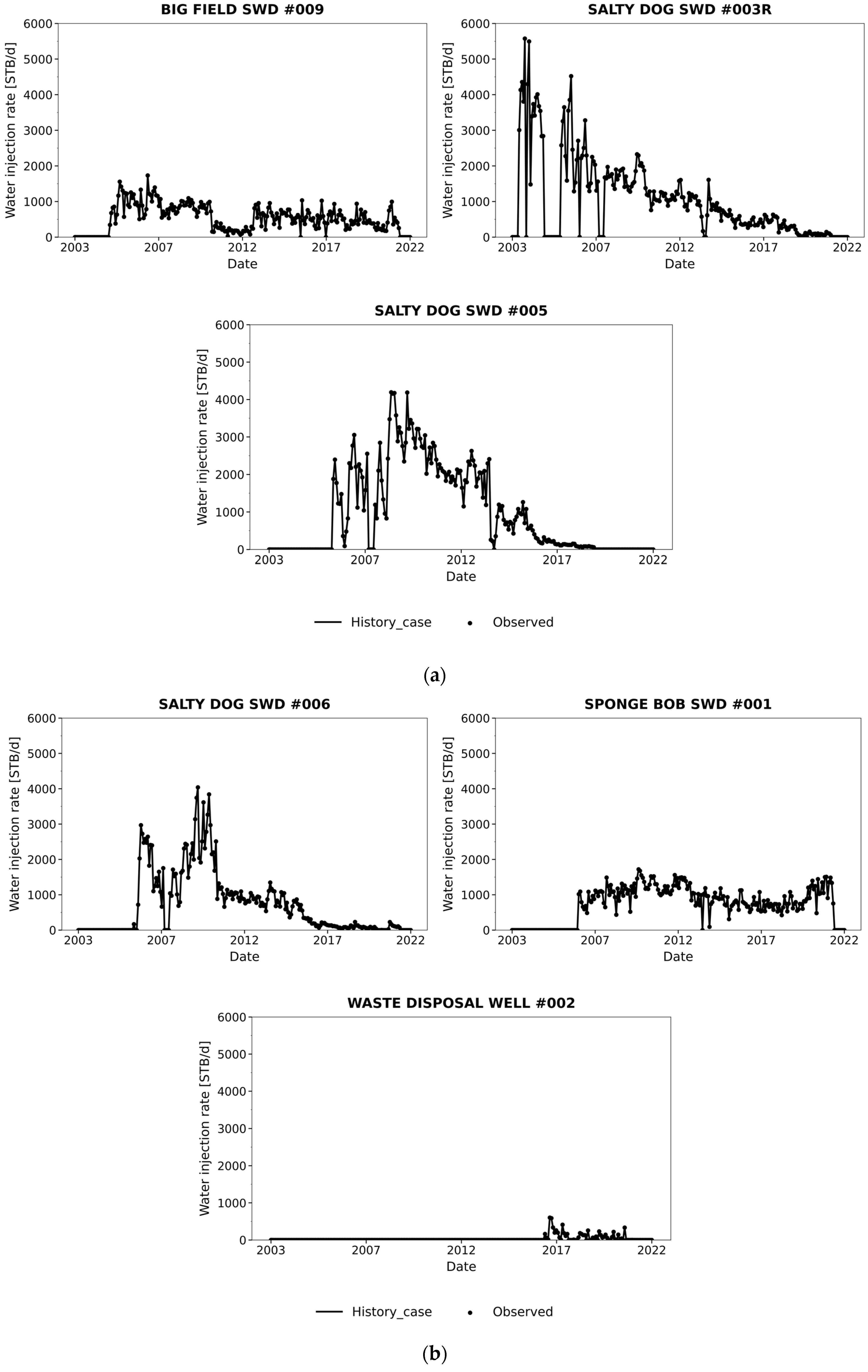

3.1. Simulating CO2 Injection Dynamics: From Calibration to Forecast

3.2. Parameter Ranking via Multi-Parameter Sensitivity

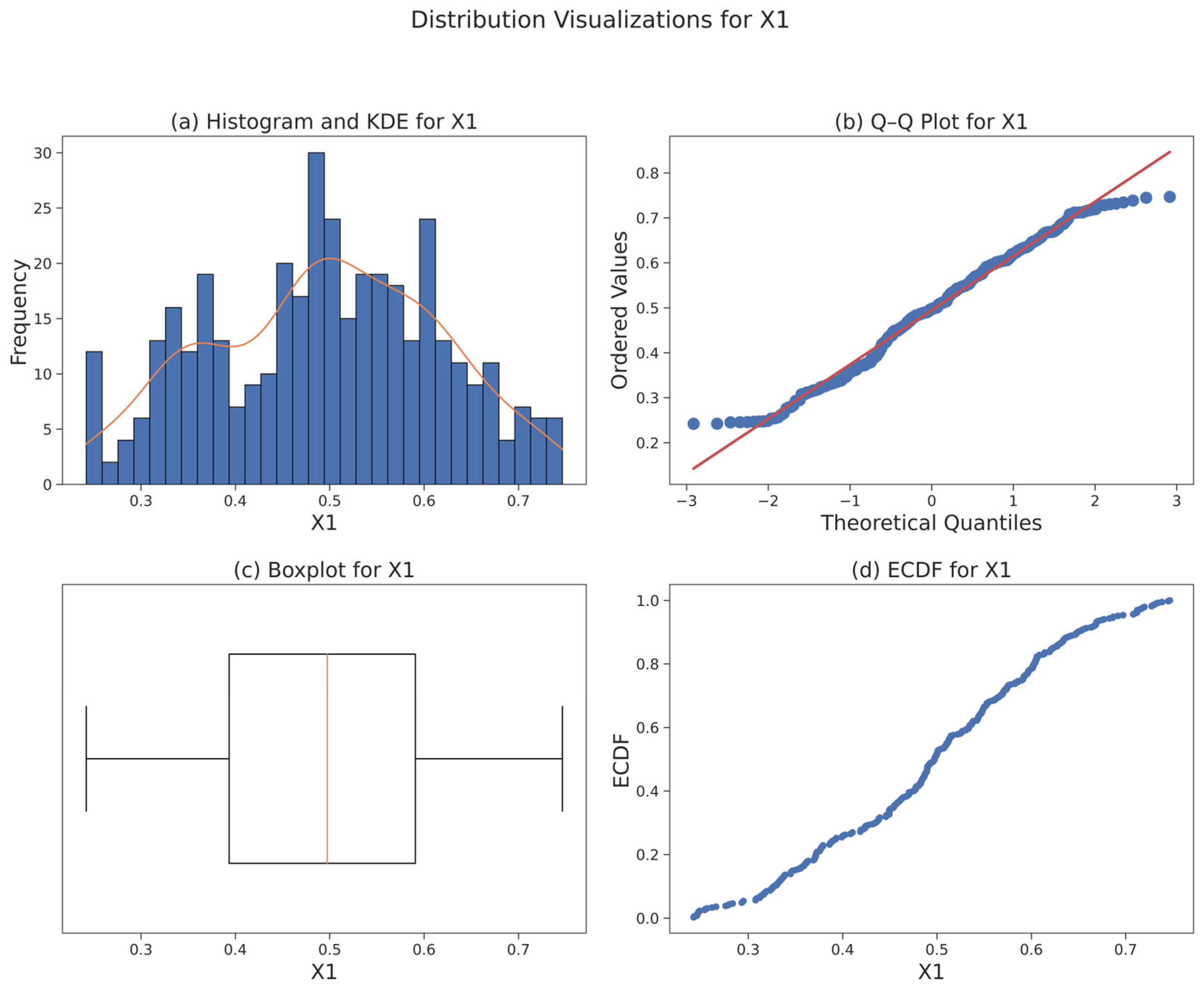

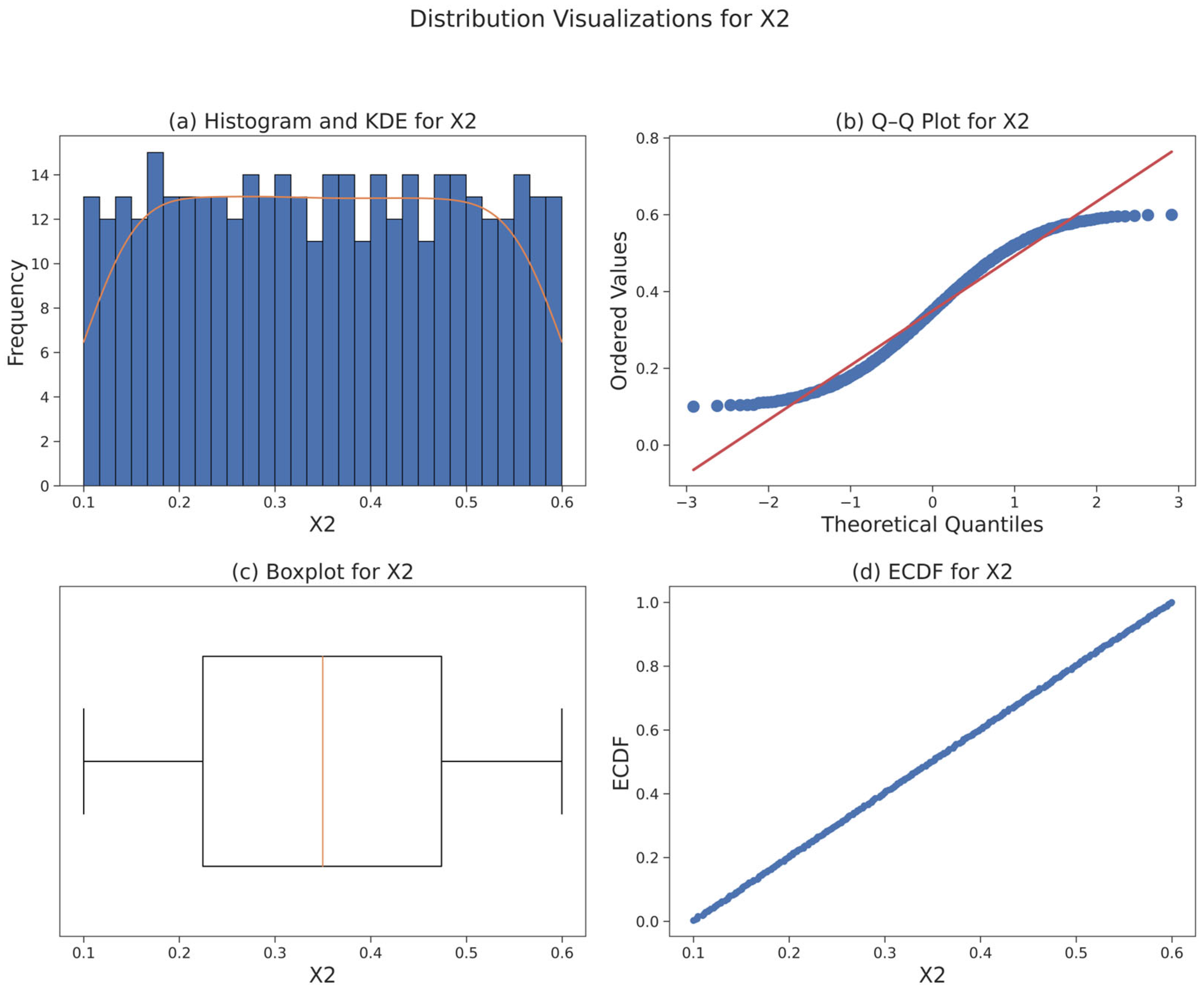

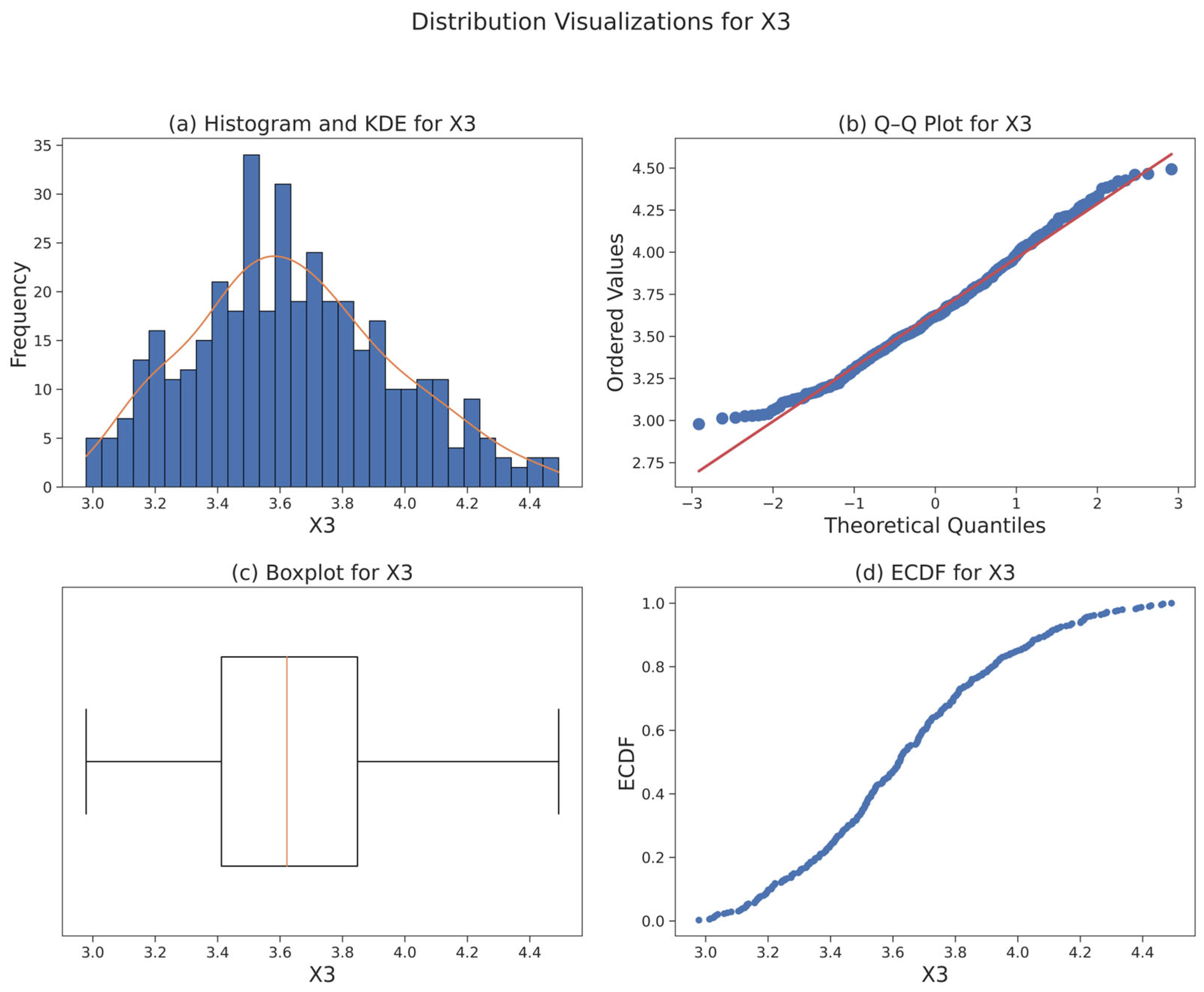

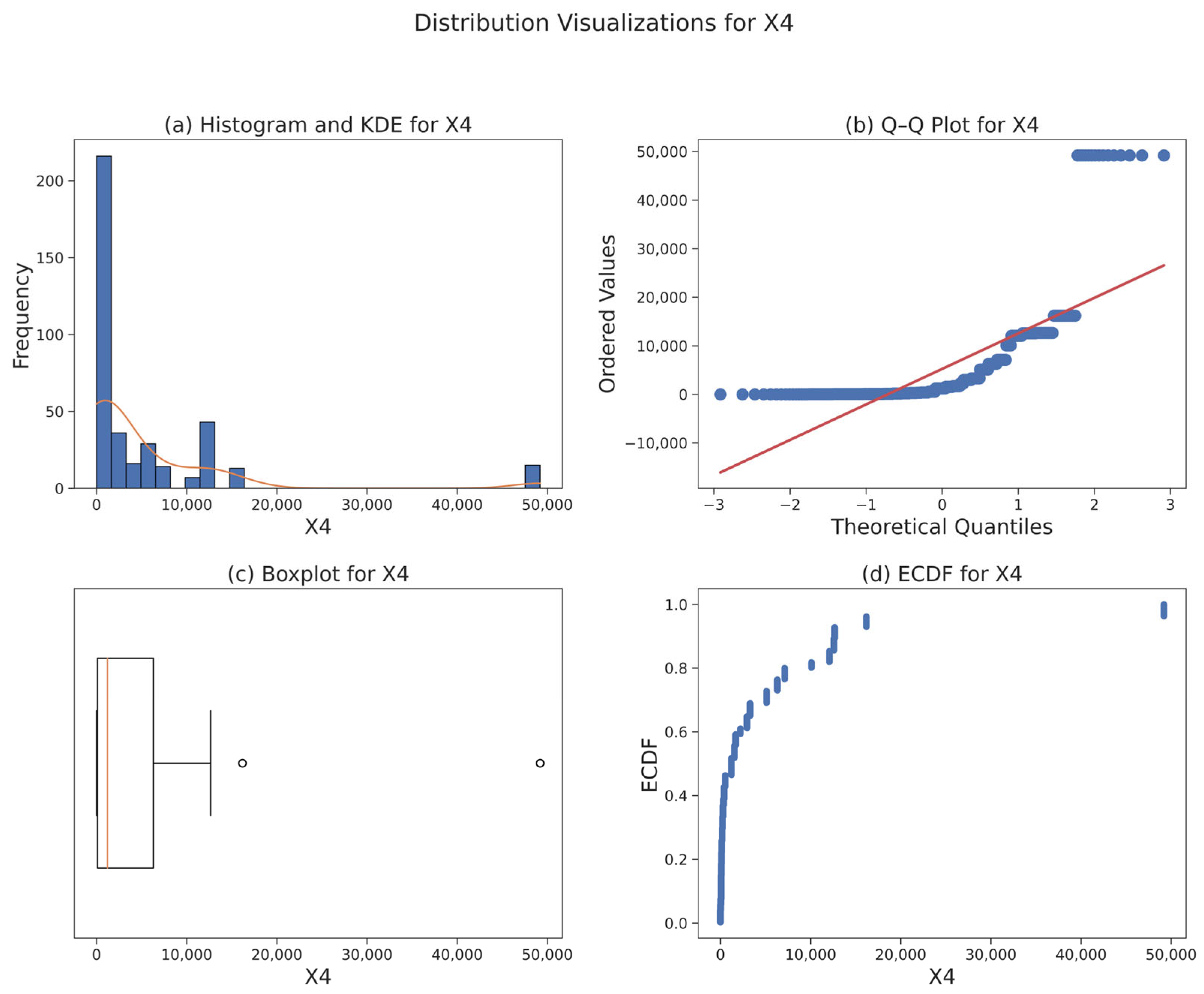

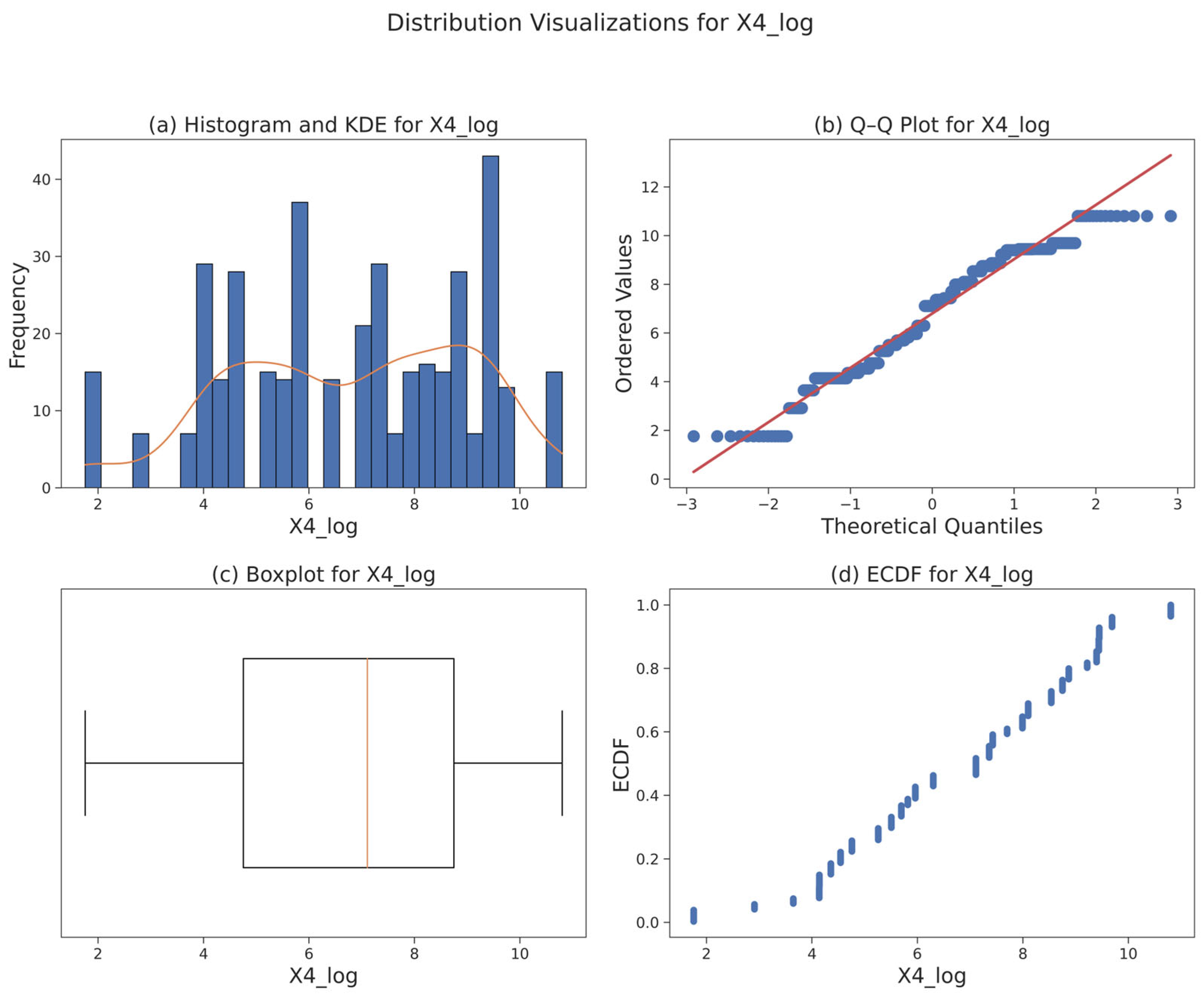

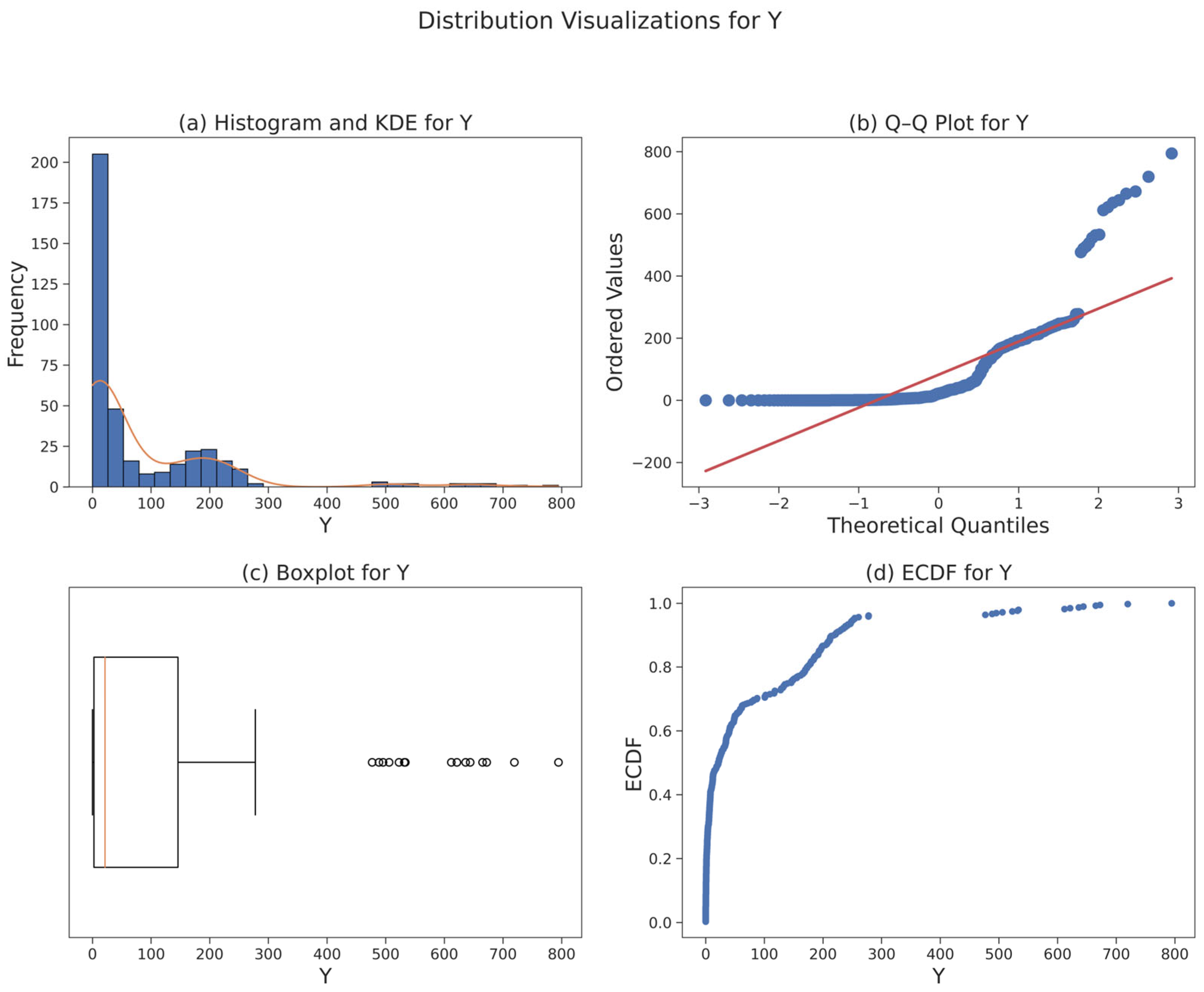

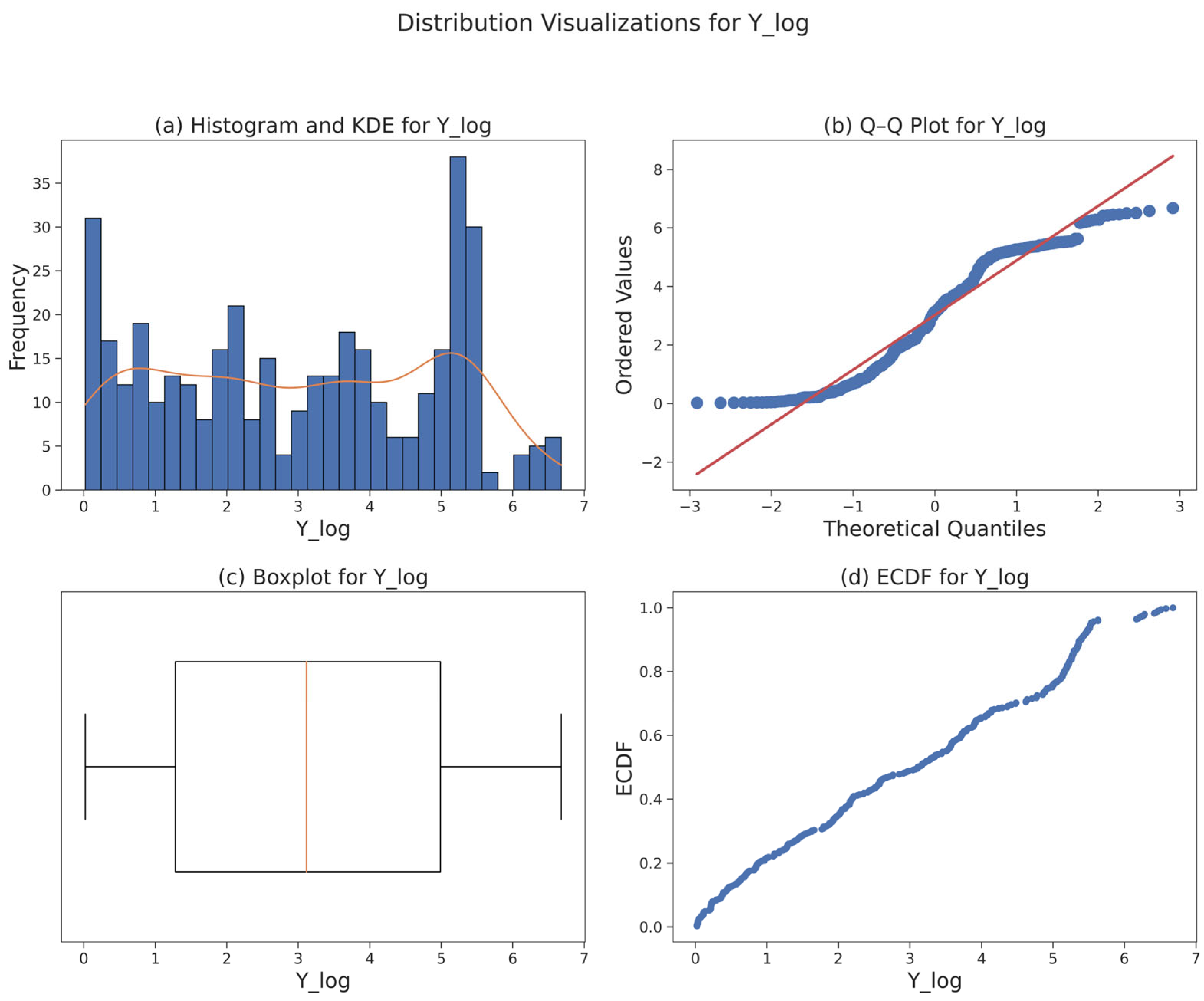

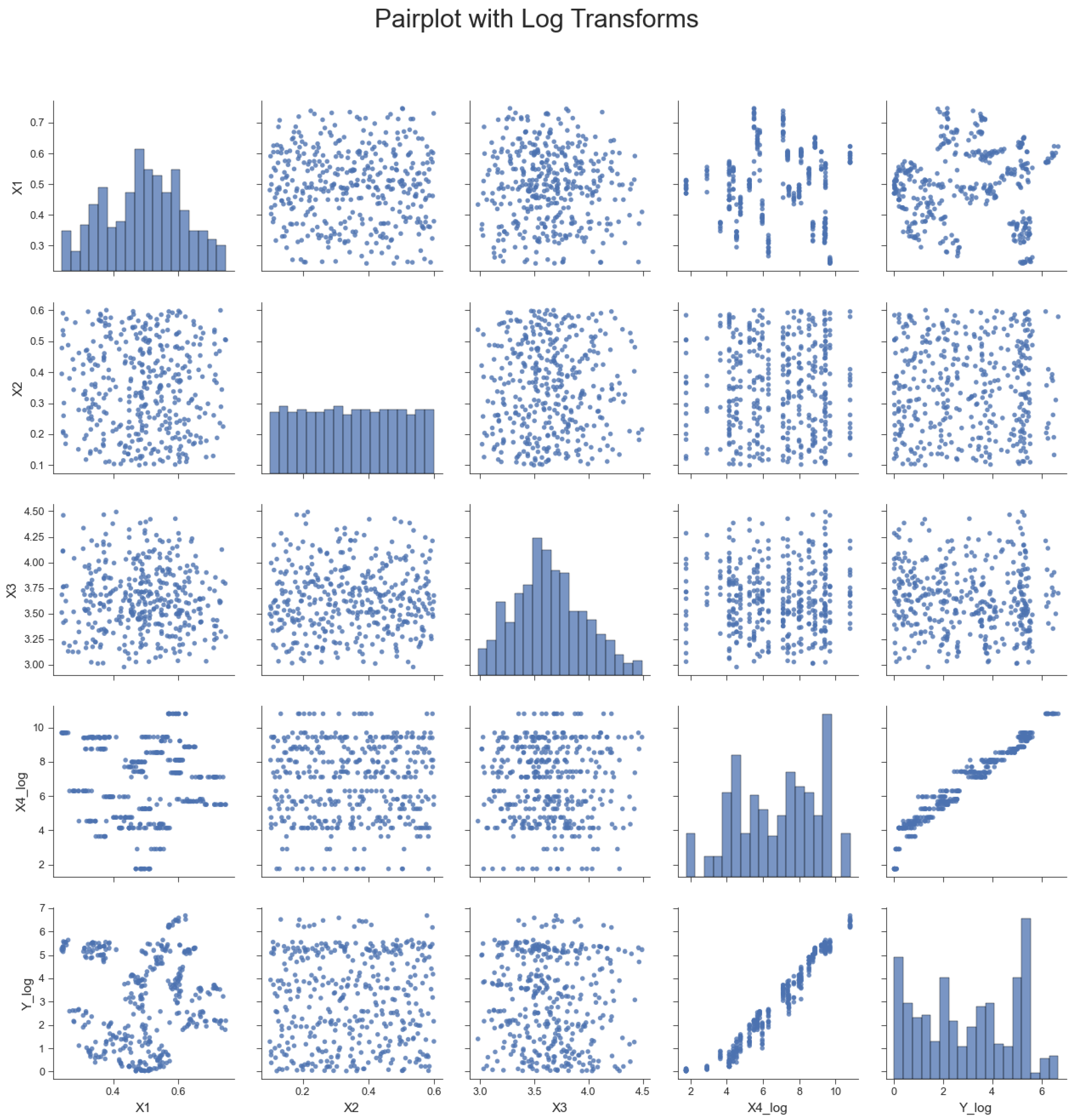

3.3. Data Foundation and Statistical Diagnostics

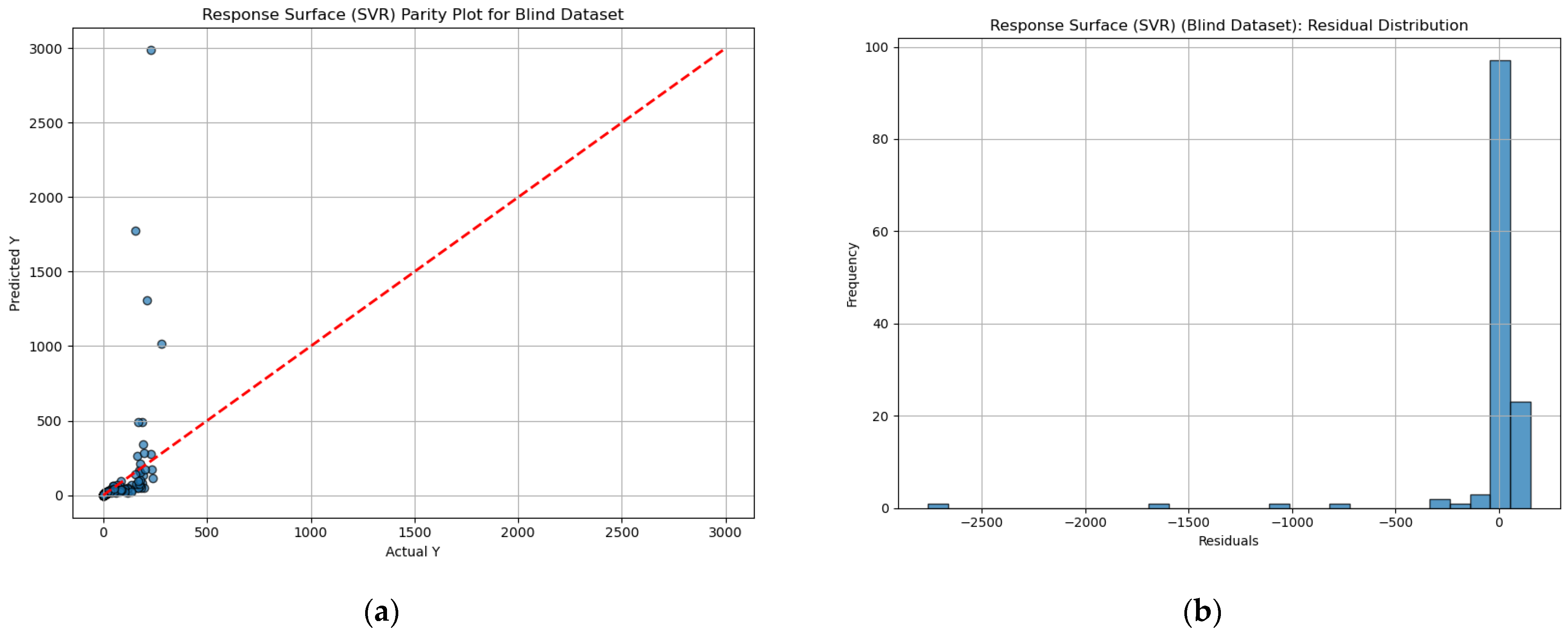

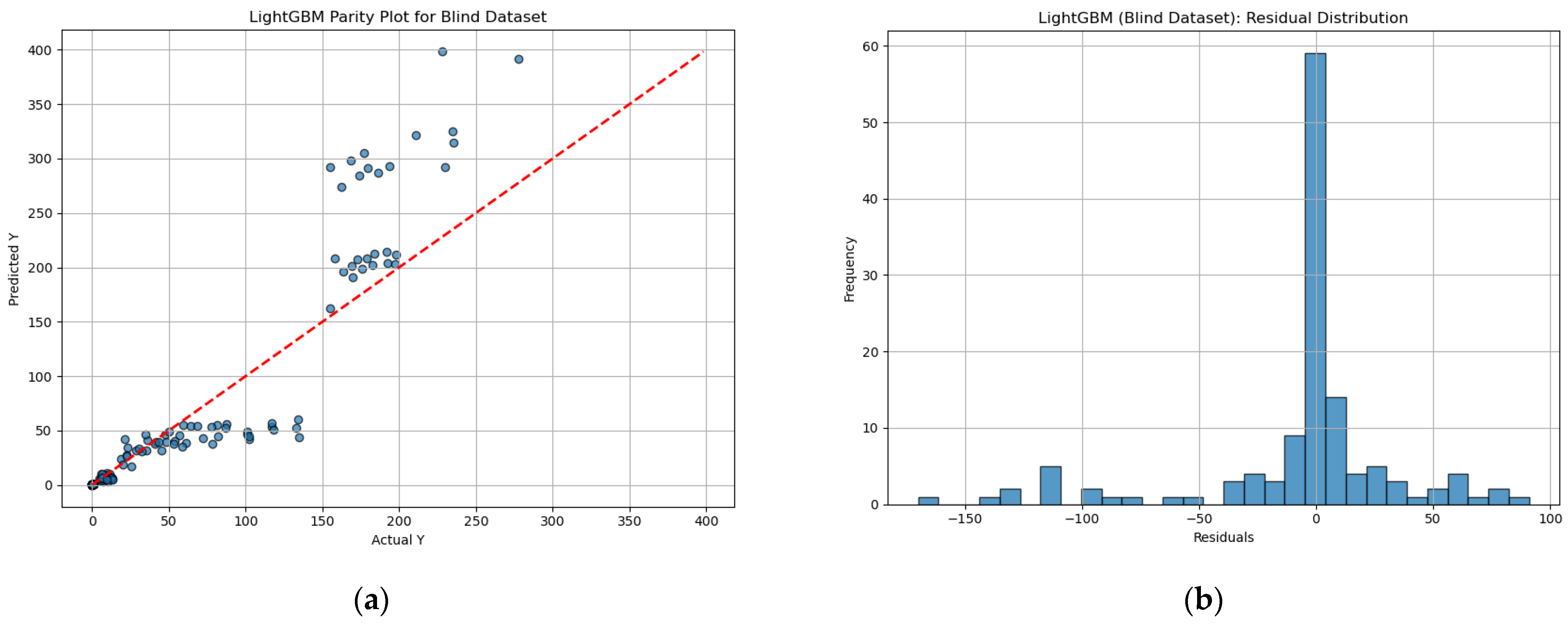

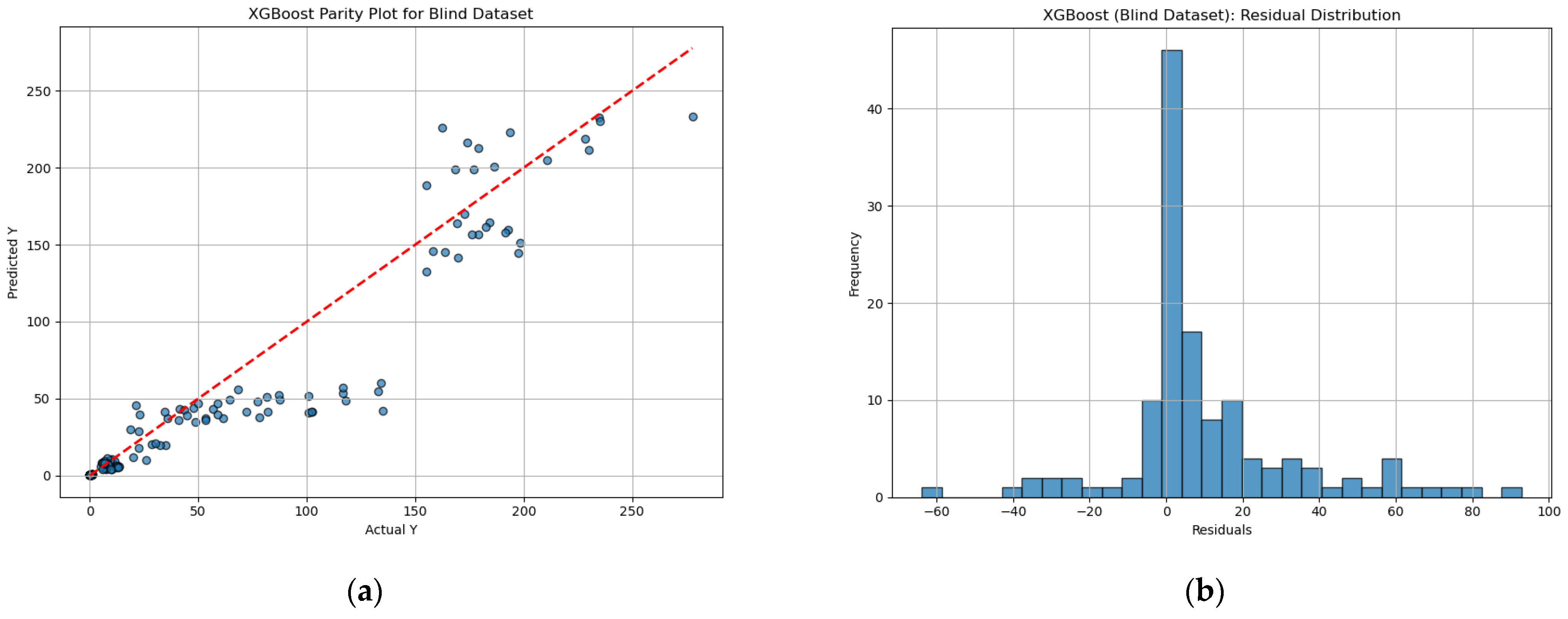

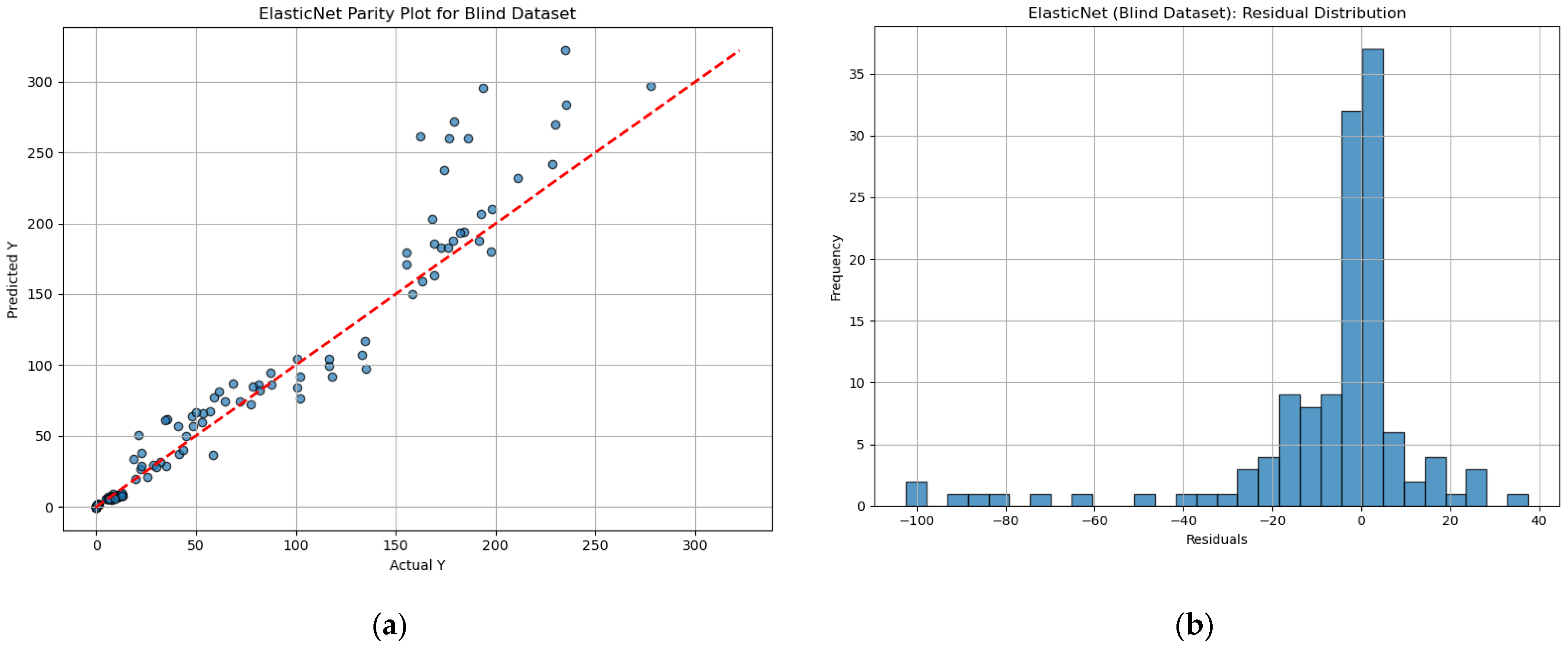

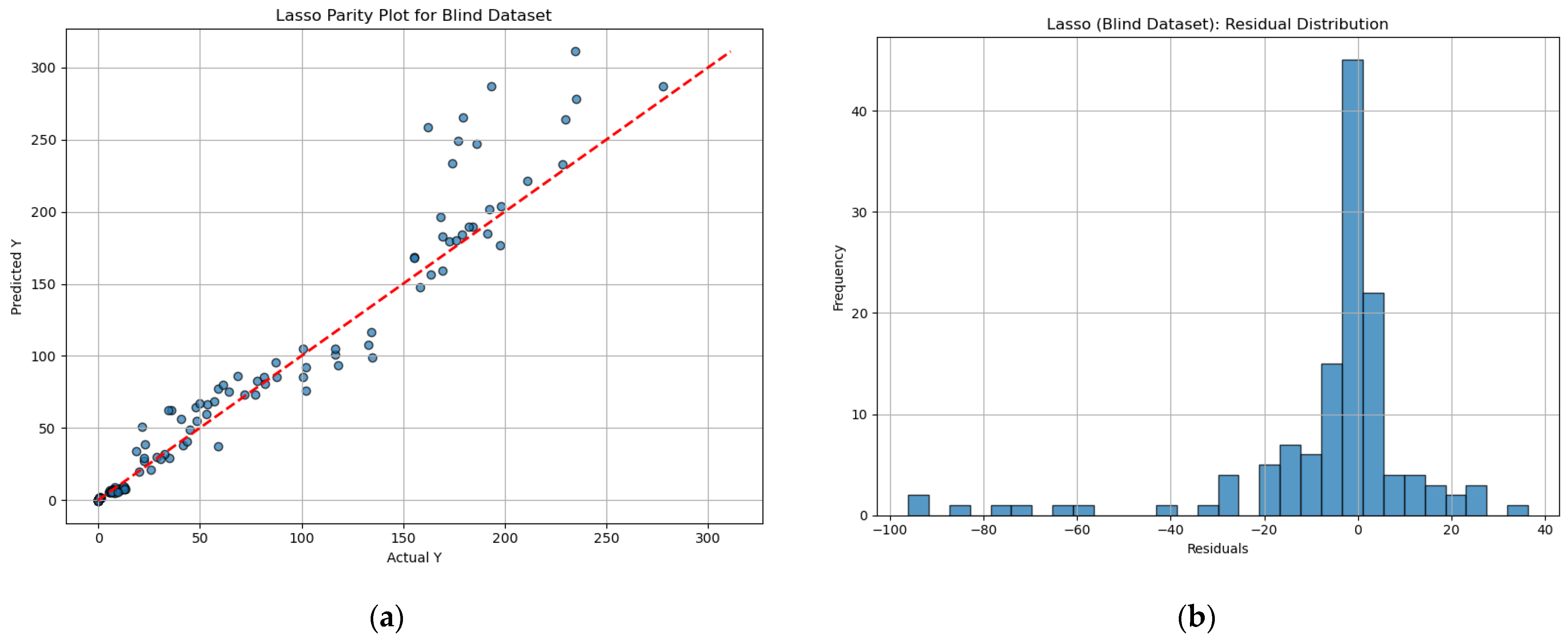

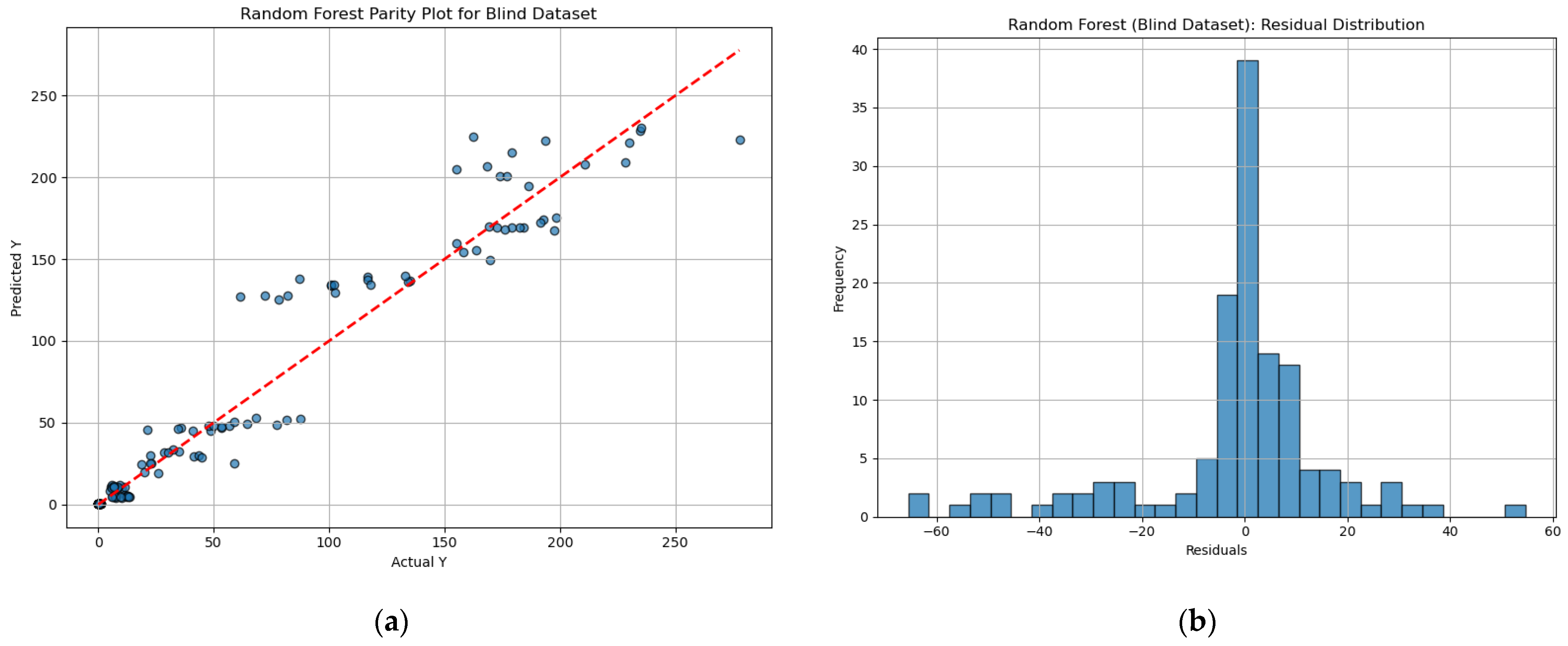

3.4. Comparative Evaluation of Machine Learning Models for CO2 Injectivity

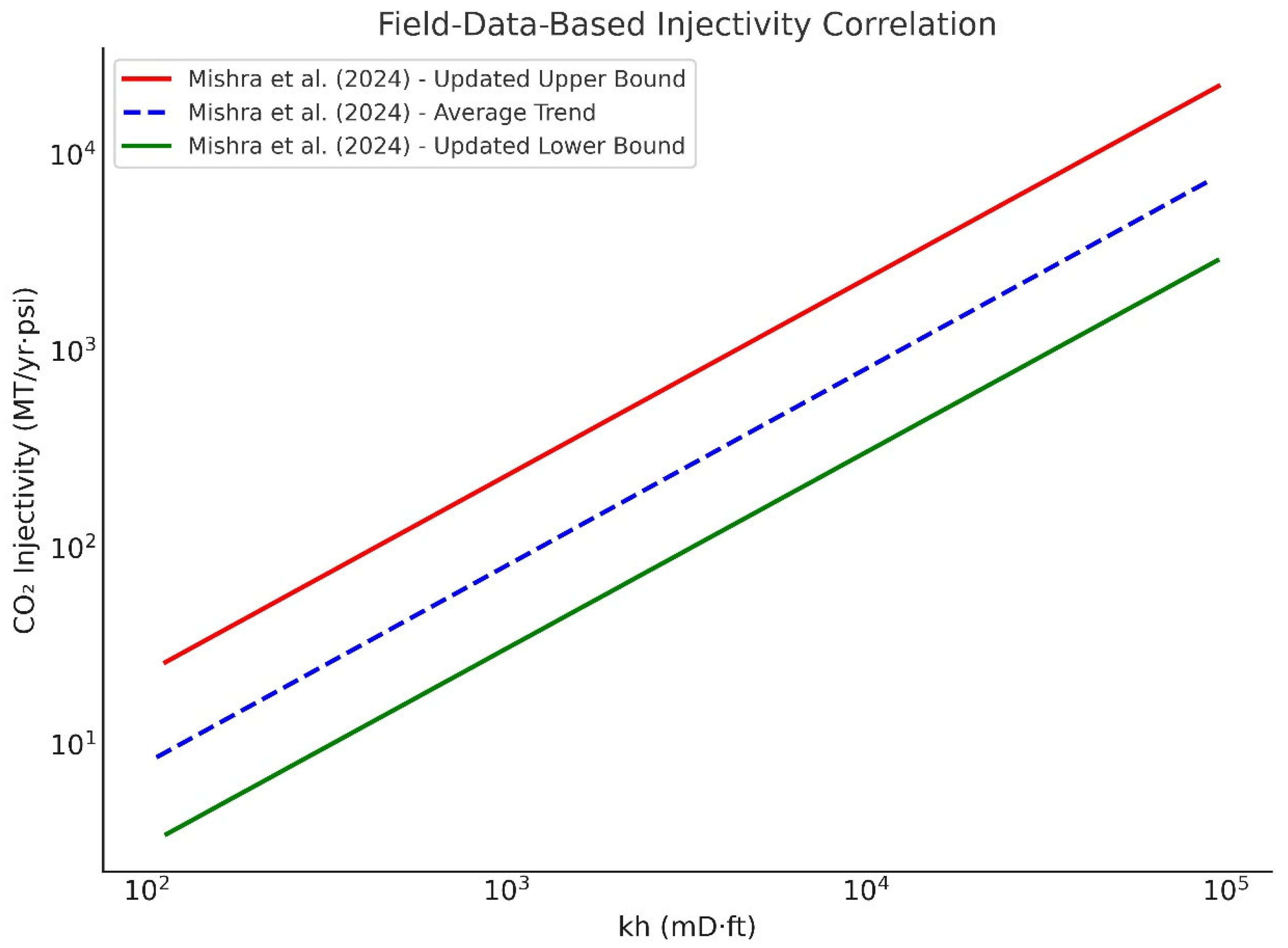

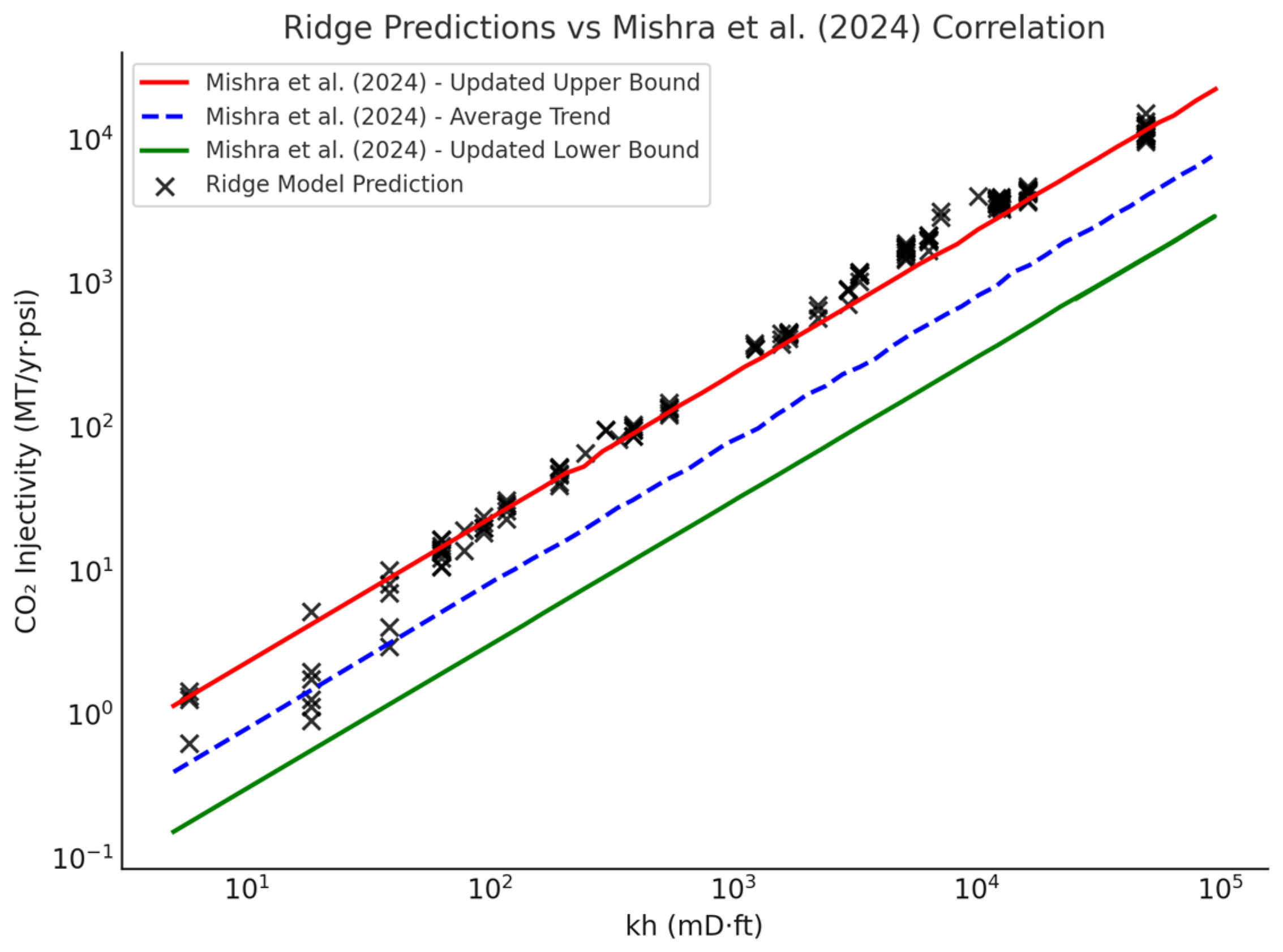

3.5. Bridging Data and Physics: Validating Ridge-Based CO2 Injectivity Predictions with Global Field Correlation

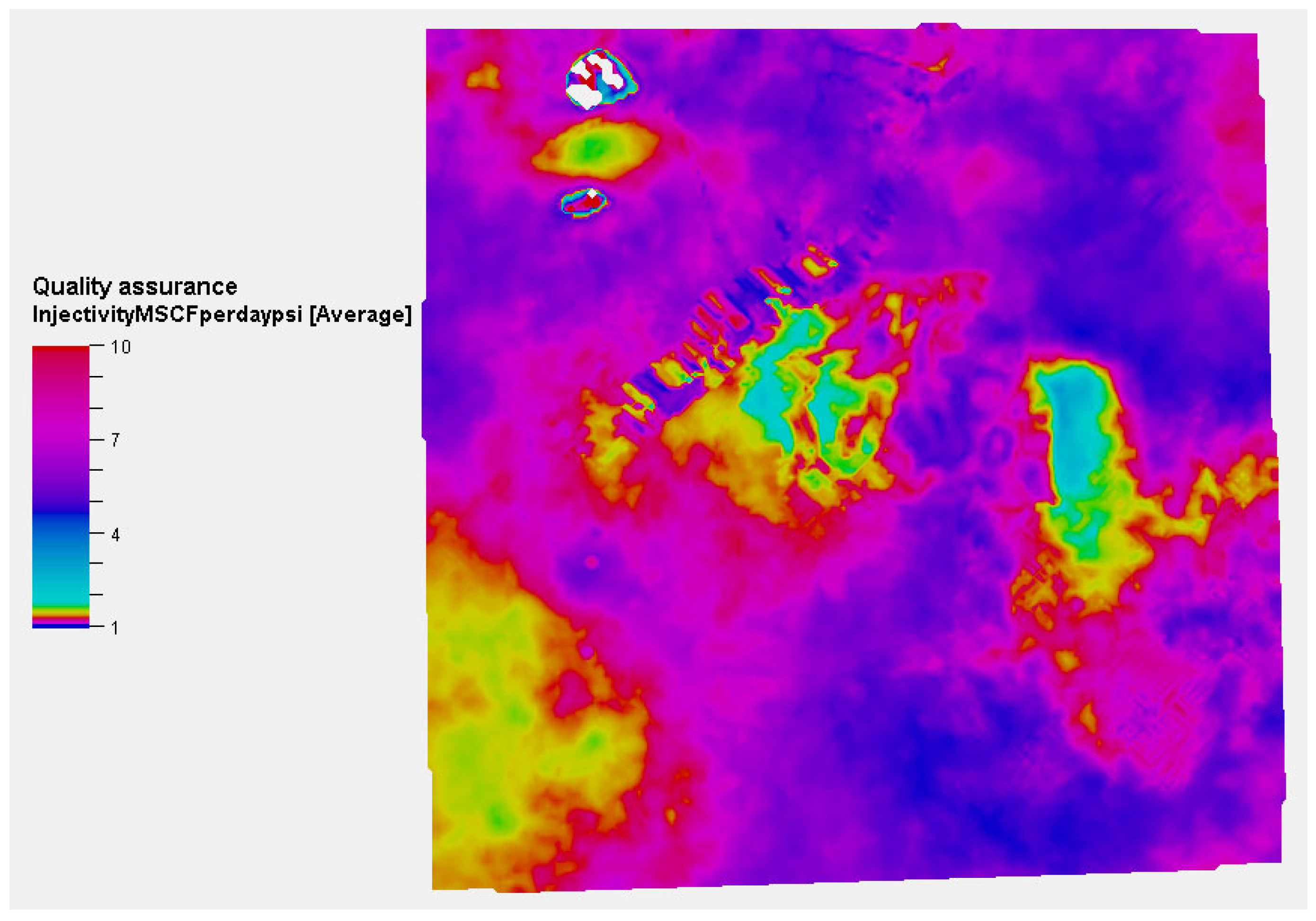

3.6. Spatial Distribution CO2 Injectivity in the Entrada Formation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBDP | Illinois Basin—Decatur Project |

| SECARB | Southeast Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership |

| MRCSP | Midwestern Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership |

| AEP | American Electric Power |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| BHP | Bottomhole Pressure |

| UDQ | User-Defined Quantity |

| WGIR | Well Gas Injection Rate |

| WBHP | Well Bottomhole Pressure |

| FPRP | Field Average Pressure |

| LHS | Latin Hypercube Sampling |

References

- Li, Y. Dynamic Modelling and Monitoring of Geological Carbon Sequestration Assets. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Essel, D.C.; Ampomah, W.; Sibaweihi, N.; Bui, D. Multi-Parameter Assessment of CO2 Injectivity for Optimal Well Siting in Geological Carbon Storage. In Proceedings of the SPE/AAPG/SEG Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 23–25 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, M.V.B.; Delshad, M.; Sepehrnoori, K. Injectivity assessment for CCS field-scale projects with considerations of salt deposition, mineral dissolution, fines migration, hydrate formation, and non-Darcy flow. Fuel 2023, 353, 129148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Benson, S.M. Influence of small-scale heterogeneity on upward CO2 plume migration in storage aquifers. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 83, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Wang, Y.; Rui, Z.; Chen, B.; Ren, S.; Zhang, L. Assessing the combined influence of fluid-rock interactions on reservoir properties and injectivity during CO2 storage in saline aquifers. Energy 2018, 155, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsæter, M.; Cerasi, P. Geological and geomechanical factors impacting loss of near-well permeability during CO2 injection. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2018, 76, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamara, H.; Blondeau, C.; Thibeau, S.; Bogdanov, I. Vertical equilibrium simulation for industrial-scale CO2 storage in heterogeneous aquifers. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeigler, B.P.; Moon, Y.; Kim, D.; Ball, G. The DEVS environment for high-performance modeling and simulation. IEEE Comput. Sci. Eng. 1997, 4, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Wei, N.; Zhang, Y.; Ali, M.; Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.; Yin, Y.; Vo Thanh, H. Advances in machine-learning-driven CO2 geological storage: A comprehensive review and outlook. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 13315–13343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah, A.; Tariq, Z.; Mustafa, A.; Mahmoud, M.; Okoroafor, E.R. A review of data-driven machine learning applications in reservoir petrophysics. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 20343–20377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Mahapatra, A.; Singal, A.; Goel, D.; Huang, K.; Scardapane, S.; Spinelli, I.; Mahmud, M.; Hussain, A. Interpreting black-box models: A review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahith, J.K.; Lal, B. Leveraging machine learning and artificial intelligence for enhanced carbon capture and storage (CCS). In Gas Hydrate in Carbon Capture, Transportation and Storage, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 159–196. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, C.; Kim, M.; Shin, H. Optimization of well placement and operating conditions for various well patterns in CO2 sequestration in the Pohang Basin, Korea. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 90, 102810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbotten, J.M.; Celia, M.A.; Bachu, S. Injection and storage of CO2 in deep saline aquifers: Analytical solution for CO2 plume evolution during injection. Transp. Porous Media 2005, 58, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, T.; Park, P.; Coll, C. A semi-analytical model for the prediction of CO2 injectivity into saline aquifers or depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Europec featured at EAGE Conference and Exhibition, Madrid, Spain, 6–9 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Ganesh, P.R.; Schuetter, J. Developing and validating simplified predictive models for CO2 geologic sequestration. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 3456–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluri, M.; Mishra, S.; Ganesh, P.R. Injectivity index: A powerful tool for characterizing CO2 storage reservoirs—A technical note. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Han, G.; Chen, Z.; Pagou, A.L.; Zhu, L.; Abdoulaye, A.M. Dynamically coupled reservoir and wellbore simulation research in two-phase flow systems: A critical review. Processes 2022, 10, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, M.W.; Horne, R.N. Investigation of injection-induced seismicity using a coupled fluid flow and rate/state friction model. Geophysics 2011, 76, WC181–WC198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SLB. ECLIPSE Reservoir Simulation Reference Manual; Schlumberger Limited: Houston, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Debossam, J.G.S.; de Freitas, M.M.; de Souza, G.; Amaral Souto, H.P.; Pires, A.P. Numerical Simulation of Non-Darcy Flow in Naturally Fractured Tight Gas Reservoirs for Enhanced Gas Recovery. Gases 2024, 4, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yuan, G.; Xia, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Y. Research on improving injection and production gas capacity based on integrated reservoir-well coupling model for gas storage. Fuel 2025, 393, 135018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzle, M.; Wang, Z. Seismic properties of pore fluids. Geophysics 1992, 57, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N. Supercritical CO2-brine relative permeability experiments in reservoir rocks—Literature review and recommendations. Transp. Porous Media 2011, 87, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.H. Pore-volume compressibility of consolidated, friable, and unconsolidated reservoir rocks under hydrostatic loading. J. Pet. Technol. 1973, 25, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.M.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Janssen, H. Efficiency enhancement of optimized Latin hypercube sampling strategies: Application to Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis and meta-modeling. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 76, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Al-Otaibi, F.; Kokal, S. Relative permeability characteristics and wetting behavior of supercritical CO2 displacing water and remaining oil for carbonate rocks at reservoir conditions. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 5464–5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dria, D.E.; Pope, G.A.; Sepehrnoori, K. Three-phase gas/oil/brine relative permeabilities measured under CO2 flooding conditions. SPE Reserv. Eng. 1993, 8, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Ganesh, P.R. A screening model for predicting injection well pressure buildup and plume extent in CO2 geologic storage projects. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2021, 106, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Modeling Injection Induced Fractures and Their Impact in CO2 Geological Storage. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clavaud, J.B.; Maineult, A.; Zamora, M.; Rasolofosaon, P.; Schlitter, C. Permeability anisotropy and its relations with porous medium structure. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2008, 113, B01202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, P.R.; Mishra, S. Reduced physics modeling of CO2 injectivity. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 3116–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.J.; Dean, M.A. To log or not to log: Bootstrap as an alternative to the parametric estimation of moderation effects in the presence of skewed dependent variables. Organ. Res. Methods 2000, 3, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, K.; Baerdemaeker, J.D.; Babuška, R. Genetic polynomial regression as input selection algorithm for non-linear identification. Soft Comput. 2006, 10, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Mahmud, M.P.; Saha, P.K.; Gupta, K.D.; Siddique, Z. Effect of data scaling methods on machine learning algorithms and model performance. Technologies 2021, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Pencina, M.; Einstein, A.J.; Liang, J.X.; Berman, D.S.; Slomka, P. Impact of train/test sample regimen on performance estimate stability of machine learning in cardiovascular imaging. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemerien, K.; Alsarayreh, S.; Altarawneh, E. Diagnosing Cardiovascular Diseases using Optimized Machine Learning Algorithms with GridSearchCV. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2024, 5, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zheng, H.; Han, B.; Li, Y.; Han, C.; Li, W. Comparative performance of eight ensemble learning approaches for the development of models of slope stability prediction. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 1477–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Ganesh, P.R.; Valluri, M.; Jenkins, C. Practical Approaches for Estimating CO2 Injectivity Index in Saline Aquifers and Applications in De-Risking CCS Projects. In Proceedings of the 17th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference (GHGT-17), Calgary, AB, Canada, 20–24 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.O.; Chugh, S.; McBurney, C.; McKishnie, R. History Matching Standards: Quality Control and Risk Analysis for Simulation. In Proceedings of the PETSOC Canadian International Petroleum Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 13–15 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rezk, M.G.; Ibrahim, A.F. Numerical investigation of CO2 plume migration and trapping mechanisms in the Sleipner field: Does the aquifer heterogeneity matter? Fuel 2025, 394, 135054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; Satapathy, S.; Daneti, J. Perspectives of CO2 injection strategies for enhanced oil recovery and storage in Indian oilfields. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 10613–10633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punase, A.D. Assessing the Effect of Reservoir Heterogeneity on CO2 Plume Migration Using Pressure Transient Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Kelley, M.; Place, M.; Cumming, L.; Mawalkar, S.; Srikanta, M.; Pardini, R. Lessons learned from CO2 injection, monitoring, and modeling across a diverse portfolio of depleted closed carbonate reef oil fields–the Midwest Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership experience. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 5540–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, H. CO2-Brine Primary Displacement in Saline Aquifers: Experiments, Simulations and Concepts. Postdoctoral Thesis, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Odi, U.; Gupta, A. Fractional Flow Analysis of Displacement in a CO2 Enhanced Gas Recovery Process for Carbonate Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering (OMAE), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1–6 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gasda, S.E.; Celia, M.A.; Nordbotten, J.M. Upslope plume migration and implications for geological CO2 sequestration in deep, saline aquifers. IES J. Part A Civ. Struct. Eng. 2008, 1, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Chinhamu, K.; Chifurira, R. Evaluating South Africa’s market risk using asymmetric power auto-regressive conditional heteroscedastic model under heavy-tailed distributions. J. Econ. Financ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Maurya, S.K.; Yadav, A.S.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, U. A new flexible logarithmic transform heavy-tailed distribution and its applications. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2021, 24, 917–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Buckley, J.P.; Kuiper, J.R.; Keil, A.P. Log-transformation of independent variables: Must we? Epidemiology 2022, 33, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enginar, O. Deep Ensembles Approach for Energy Forecasting. Ph.D. Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Nan, B.; Li, Y. A Revisit to De-biased Lasso for Generalized Linear Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lai, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shao, L.; Wu, J.; Xie, G.S. Discriminative elastic-net regularized linear regression. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model\Test Size | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.986 | 0.985 | 0.977 |

| XGBoost | 0.990 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.980 |

| Ridge | 0.984 | 0.984 | 0.979 | 0.980 | 0.981 |

| ElasticNet | 0.979 | 0.982 | 0.980 | 0.982 | 0.978 |

| LightGBM | 0.977 | 0.969 | 0.970 | 0.964 | 0.911 |

| Lasso | 0.972 | 0.975 | 0.973 | 0.978 | 0.972 |

| Response Surface (SVR) | 0.817 | 0.203 | −0.270 | −0.098 | −0.794 |

| Test Size | Mean R2 | Mean MAE | Mean MSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.96 | 16.78 | 1490.22 |

| 0.20 | 0.87 | 16.57 | 4576.11 |

| 0.25 | −0.03 | 22.79 | 142,950.84 |

| 0.30 | −0.01 | 19.27 | 51,445.84 |

| 0.40 | −0.11 | 28.61 | 405,888.61 |

| Model | Train MSE | Train MAE | Train R2 | Test MSE | Test MAE | Train R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 40.855 | 2.698 | 0.998 | 164.737 | 7.562 | 0.994 |

| Ridge | 271.332 | 8.869 | 0.988 | 175.602 | 7.347 | 0.994 |

| XGBoost | 54.740 | 3.523 | 0.997 | 187.513 | 5.425 | 0.993 |

| ElasticNet | 379.966 | 10.007 | 0.983 | 851.040 | 13.608 | 0.971 |

| Response Surface | 1209.355 | 18.303 | 0.945 | 872.499 | 18.735 | 0.970 |

| LightGBM | 252.877 | 5.579 | 0.988 | 1010.741 | 15.676 | 0.965 |

| Lasso | 474.329 | 10.738 | 0.978 | 1211.447 | 16.068 | 0.958 |

| Model | Blind MSE | Blind MAE | Blind R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 344.38 | 11.17 | 0.93 |

| Ridge | 410.54 | 11.03 | 0.93 |

| Lasso | 460.31 | 10.97 | 0.92 |

| ElasticNet | 554.90 | 12.03 | 0.90 |

| XGBoost | 640.75 | 15.43 | 0.88 |

| LightGBM | 1901.12 | 23.82 | 0.66 |

| Response Surface | 95,860.72 | 78.35 | −0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Essel, D.C.; Ampomah, W.; Sibaweihi, N.; Bui, D. Data-Driven Site Selection Based on CO2 Injectivity in the San Juan Basin. Energies 2026, 19, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030764

Essel DC, Ampomah W, Sibaweihi N, Bui D. Data-Driven Site Selection Based on CO2 Injectivity in the San Juan Basin. Energies. 2026; 19(3):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030764

Chicago/Turabian StyleEssel, Donna Christie, William Ampomah, Najmudeen Sibaweihi, and Dung Bui. 2026. "Data-Driven Site Selection Based on CO2 Injectivity in the San Juan Basin" Energies 19, no. 3: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030764

APA StyleEssel, D. C., Ampomah, W., Sibaweihi, N., & Bui, D. (2026). Data-Driven Site Selection Based on CO2 Injectivity in the San Juan Basin. Energies, 19(3), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030764