Advanced Universal Hybrid Power Filter Configuration for Enhanced Harmonic Mitigation in Industrial Power Systems: A Field-Test Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

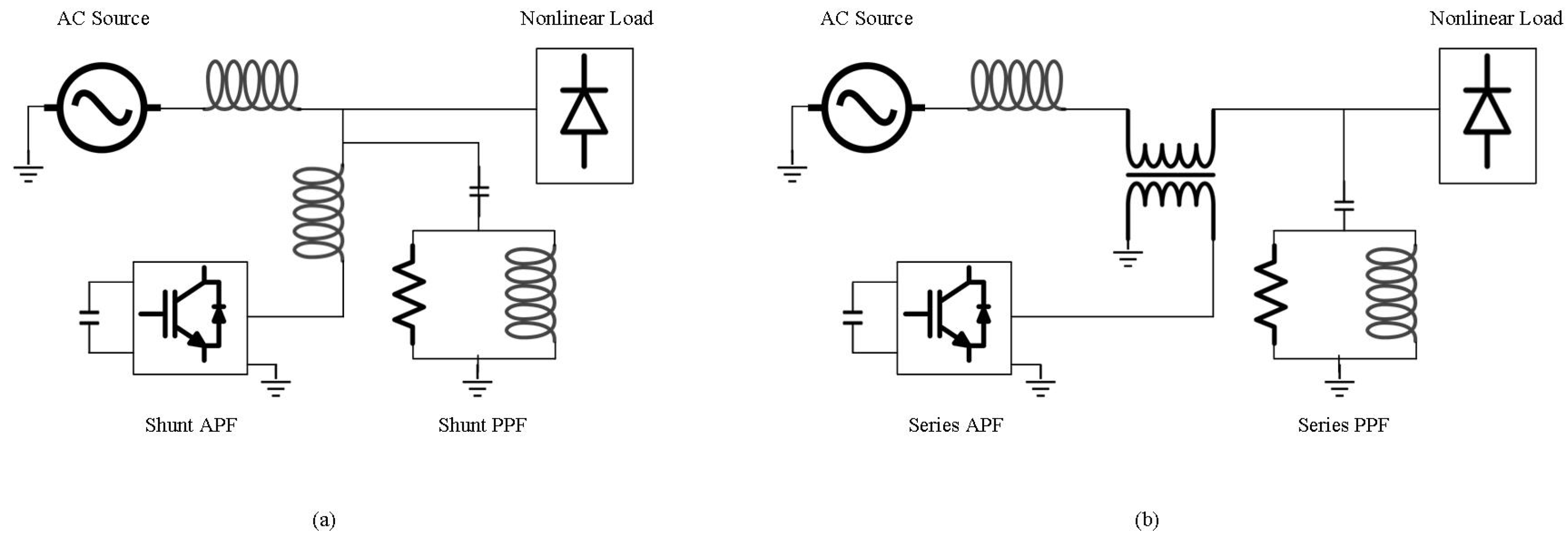

- The filtering performance is highly dependent upon the power system’s impedance, as the impedance of the power transmission line affects current flow in each branch according to Kirchhoff’s current law. Performance can be poor in large power systems with low source impedance—a ‘stiff’ source.

- Multiple tuned filtering branches are often required since each LC branch can only compensate for a specific frequency harmonic. Additionally, there is a risk of series or parallel resonance, which complicates the design process.

- Resonance can occur between the internal impedance of the power system and the tuned trap filter, leading to harmonic amplification.

- They cannot dynamically attenuate harmonics or compensate for reactive power.

- They have considerable weight and volume.

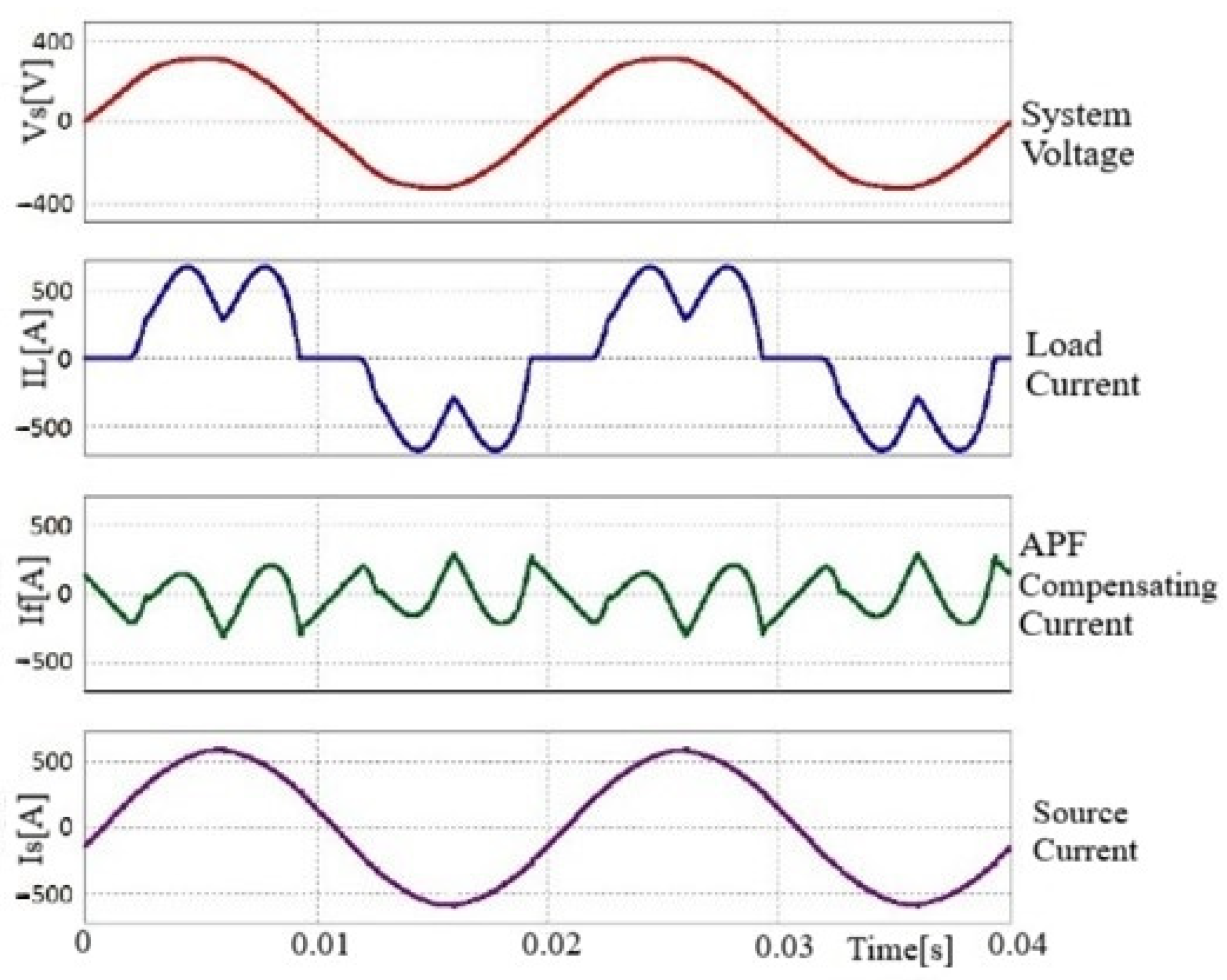

- Fast dynamic response performance.

- Reduction of harmonic distortion while compensating for the reactive power dynamically without being significantly influenced by the grid’s parameters (performance is mostly independent of the power distribution system properties).

- APFs are capable of suppressing both supply current harmonics and reactive currents.

- APFs can often avoid harmful resonances with the power distribution systems.

- Smaller volume and lighter weight.

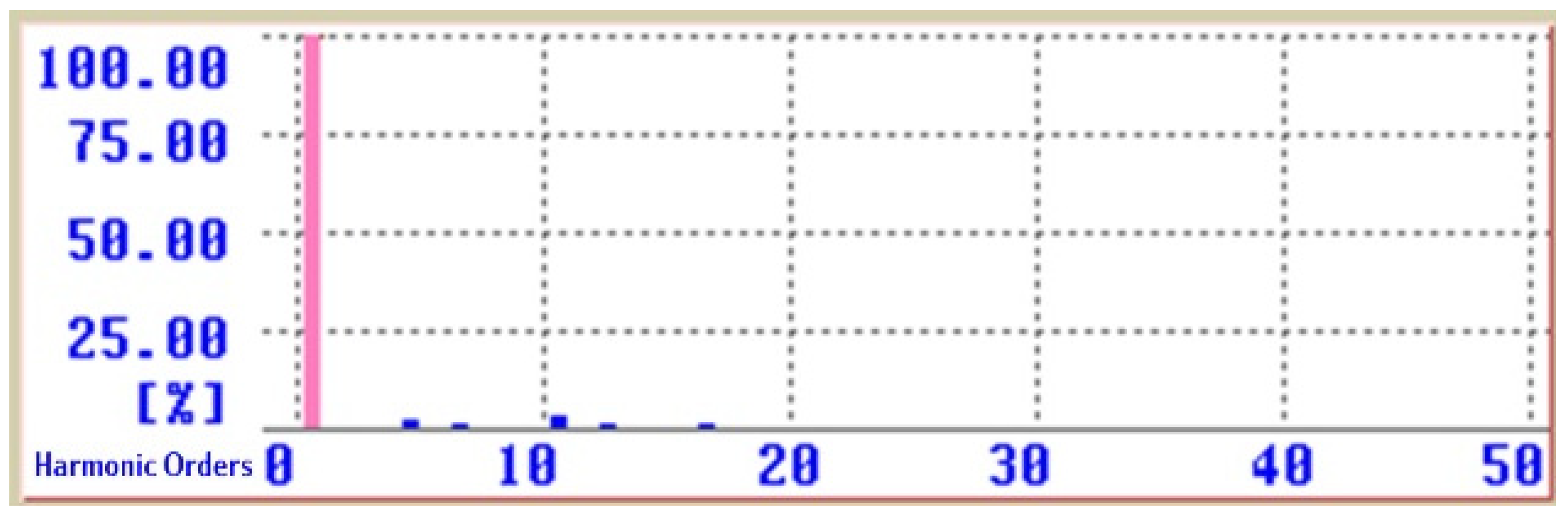

- Performance Outcome: Successfully achieved current total harmonic distortion (THDi) of 1.2%, indicating significant effectiveness in harmonic mitigation across tested configurations.

- Novel Configuration: Present a novel hybrid configuration of APF and AUHF, achieving such a low THDi in both description and practice.

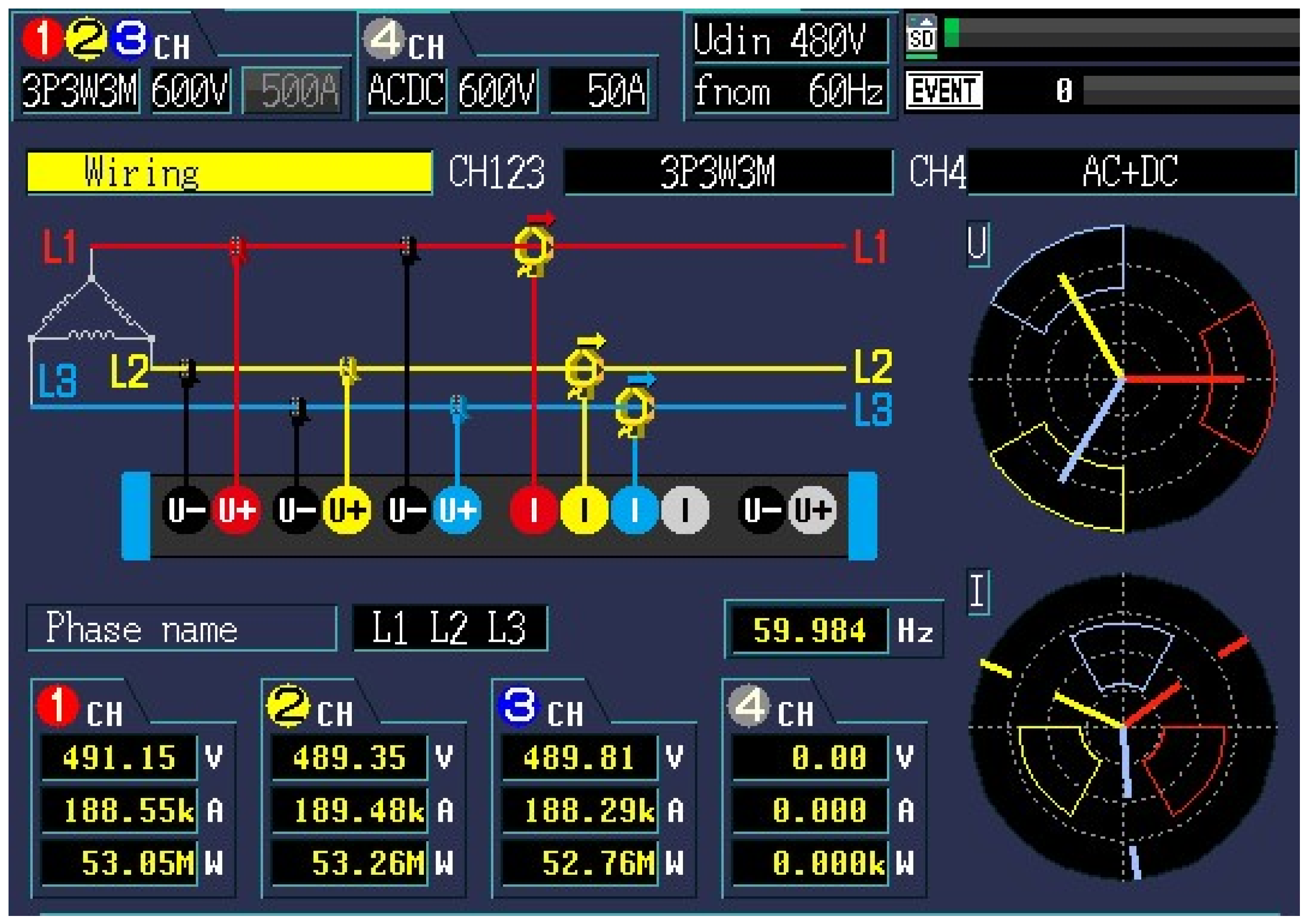

- Setup and Testing Conditions: Real-time hardware tests include active power filters, passive power filters, a variable frequency drive, an electric motor, and main and auxiliary current transformers performing under both half-load and full-load conditions to compare different configurations of power quality filters.

- Measurement Precision: Utilized newly calibrated measurement devices for accurate data collection, ensuring reliable test results. This process was conducted in accordance with key industrial standards, including IEEE Std 519 [27], to guarantee compliance with established power quality and harmonic distortion benchmarks.

- Comparative Analysis: Conducted comprehensive comparisons across different filter configurations—passive, active, and hybrid—to understand their performance under varying load conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

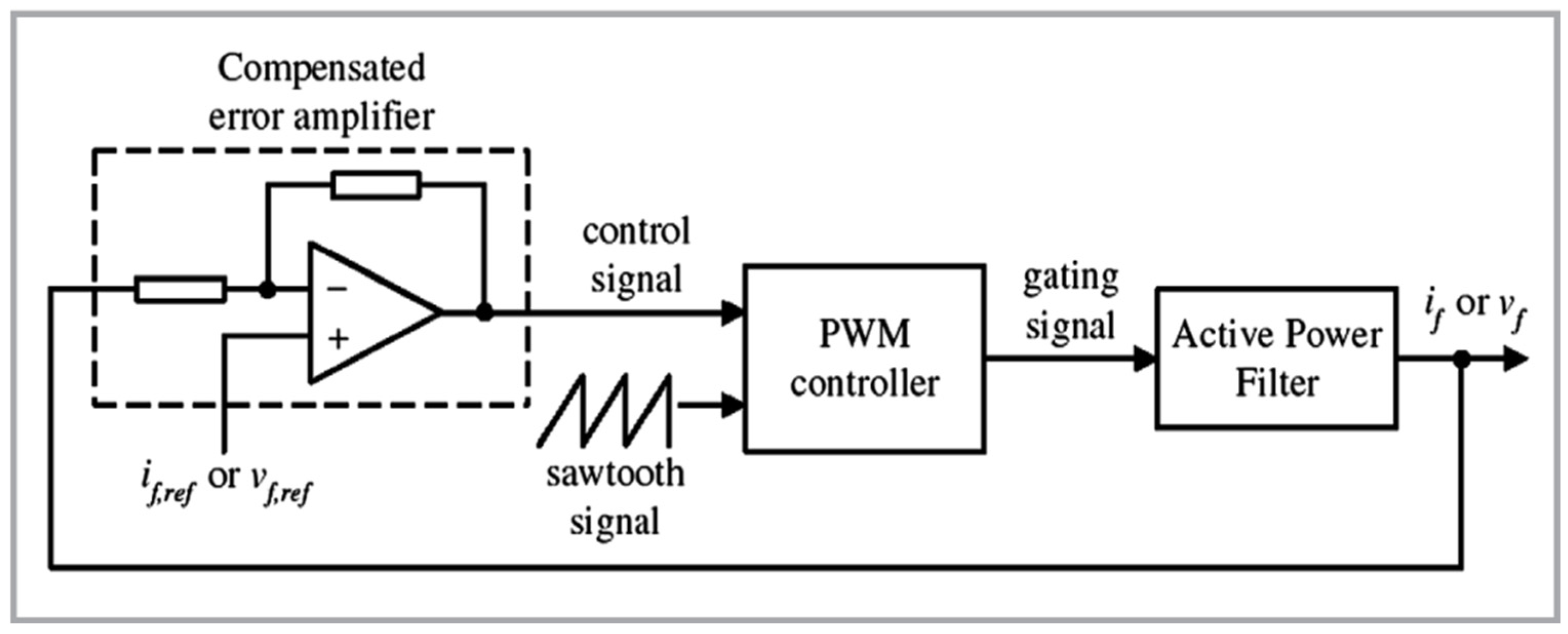

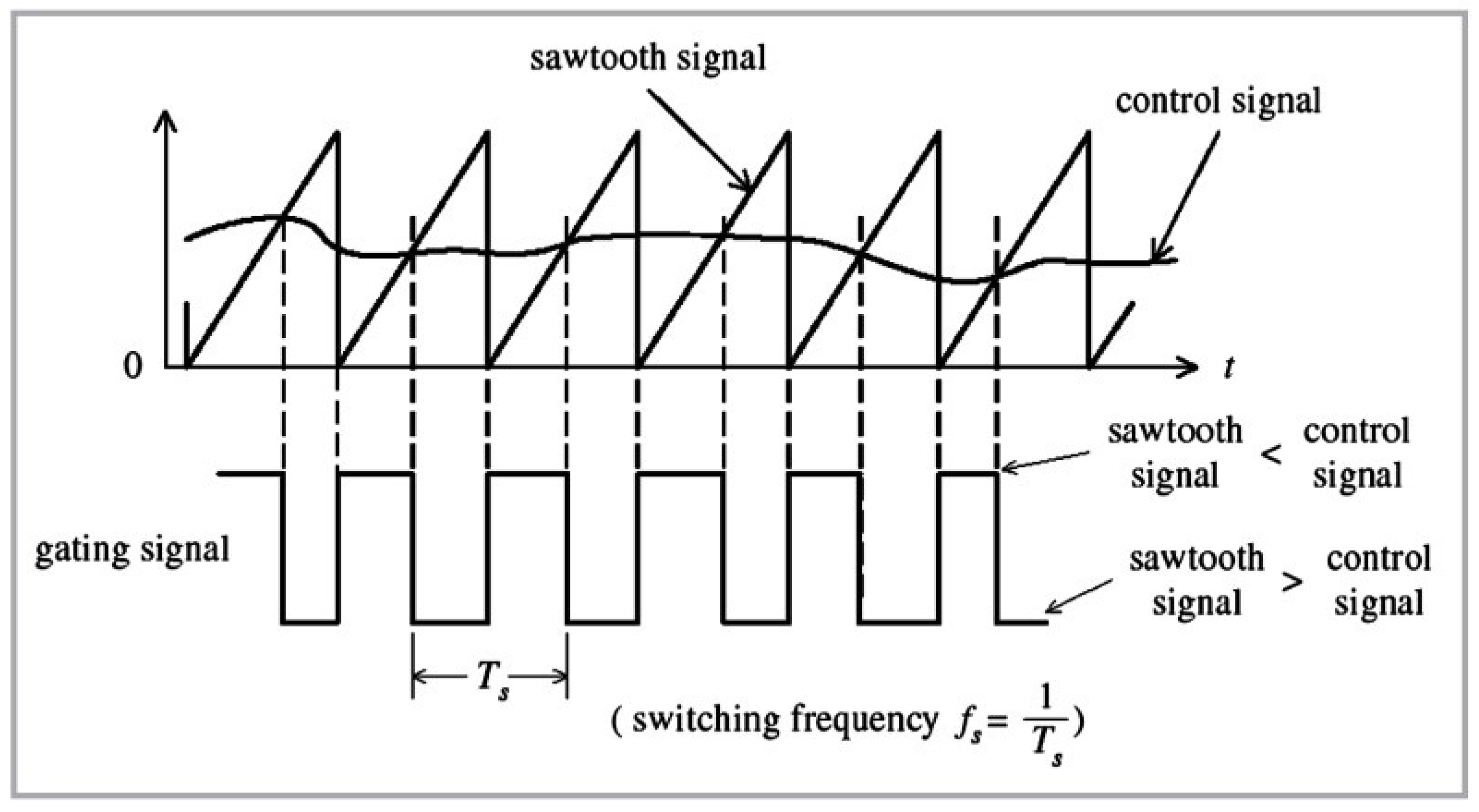

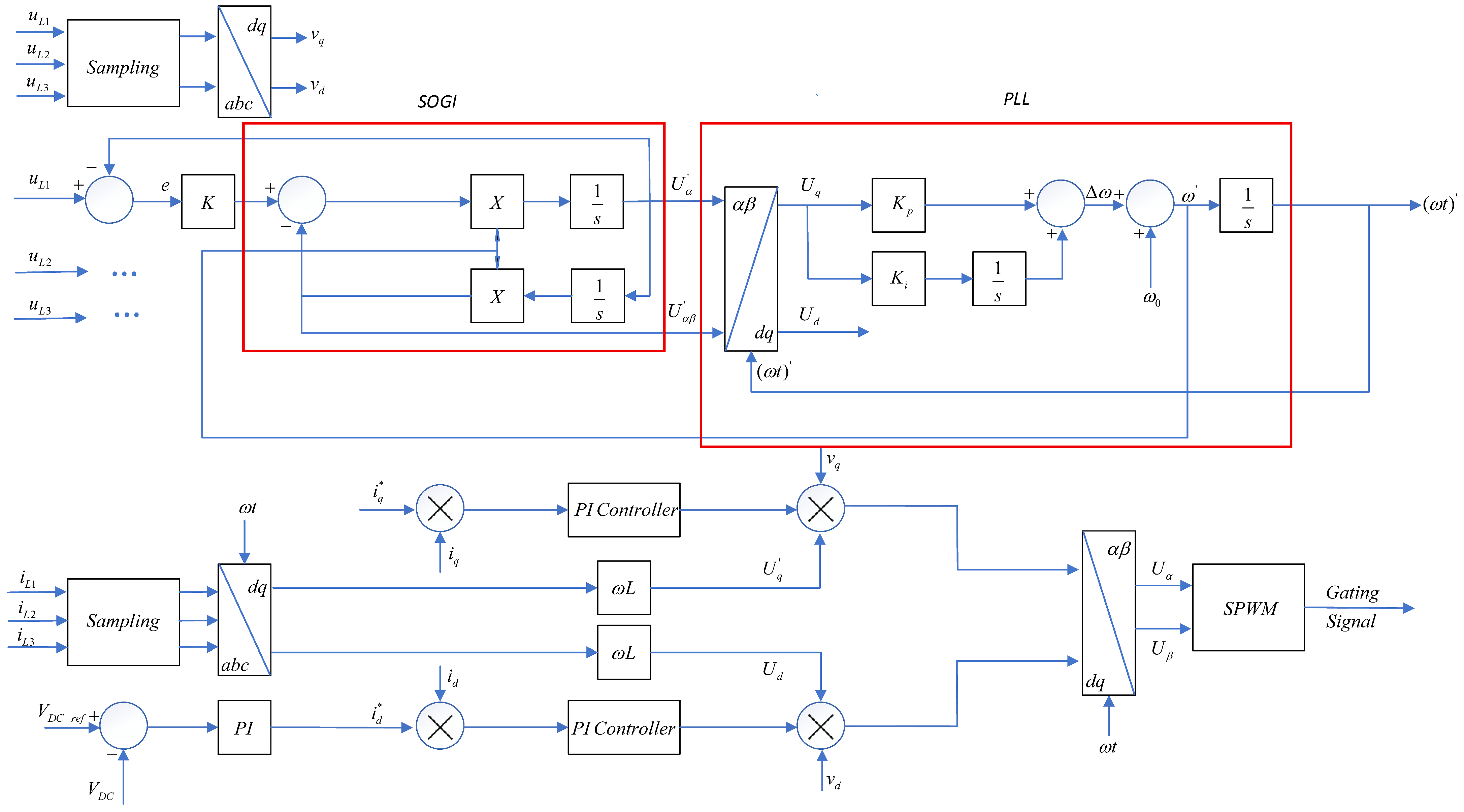

2.1. Linear Control Technique

2.2. Signal Conditioning and Reference Current Generation

2.3. Standards and Certifications

2.3.1. IEEE Standards for Power Quality Compliance

2.3.2. UL Standard for Safety and Reliability

2.3.3. CSA Standard for Canadian Regulatory Requirements

2.3.4. ABS Standard for Shipboard Power Quality Equipment

2.3.5. ISO Compliance and Quality Standards

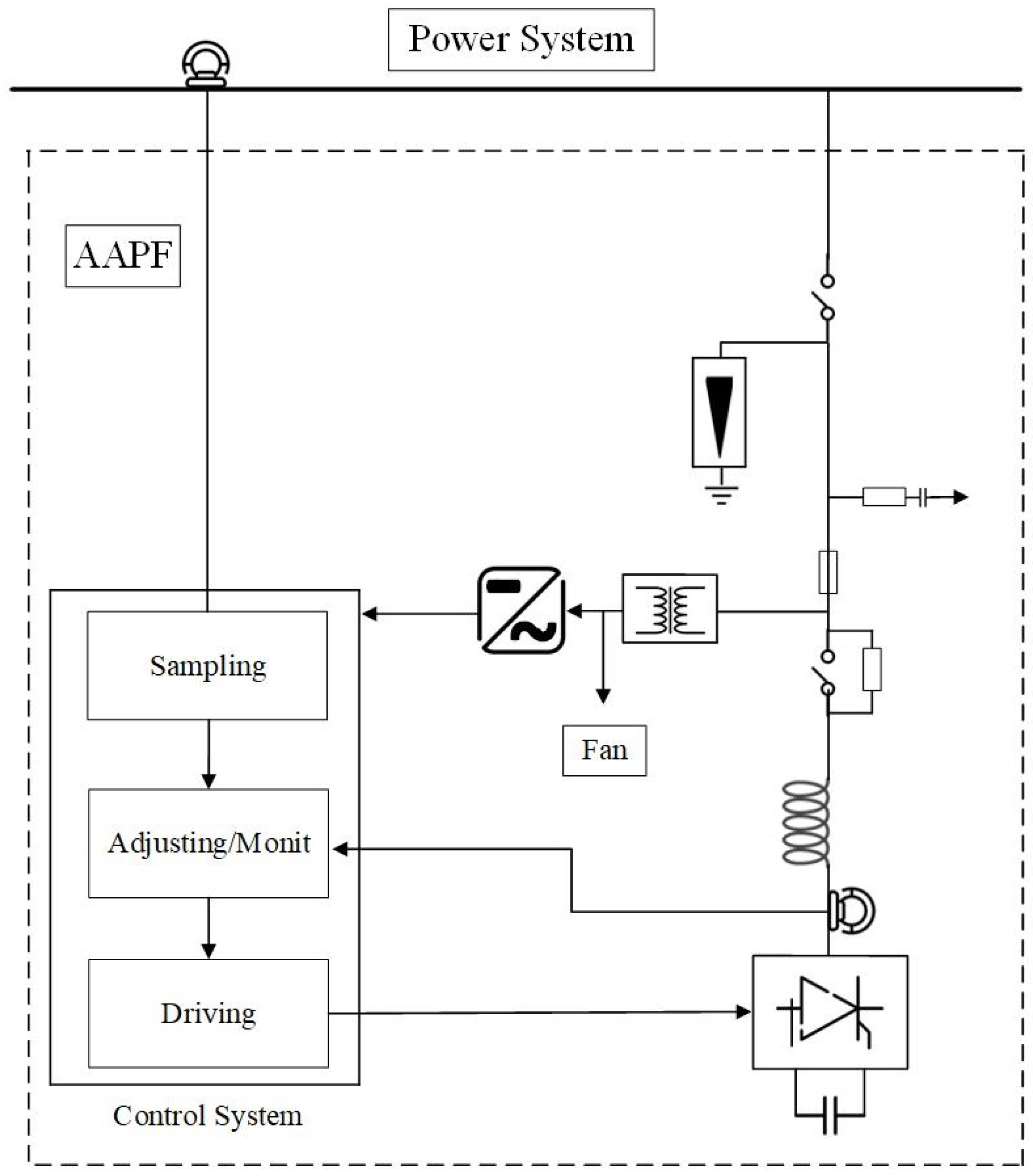

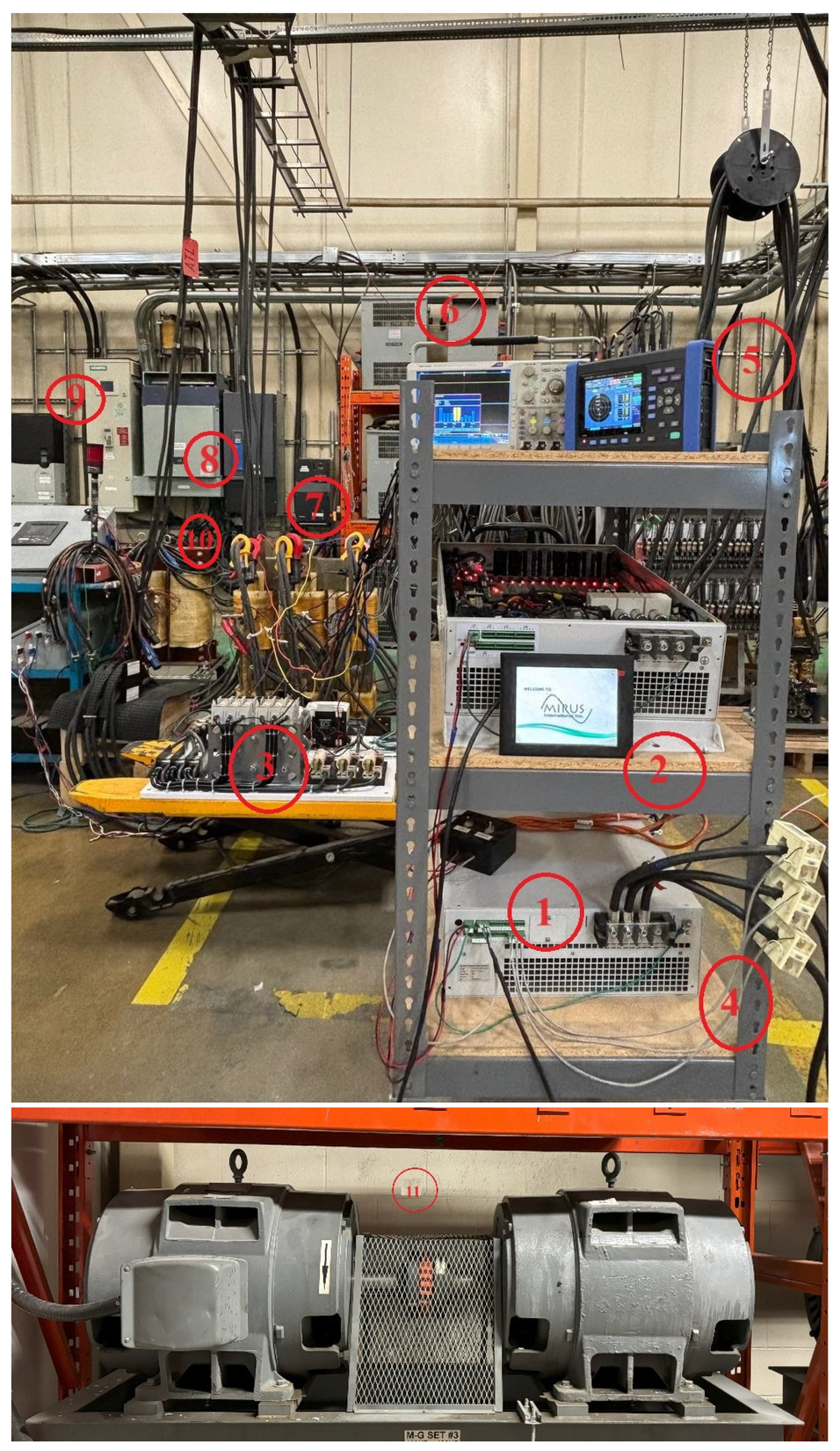

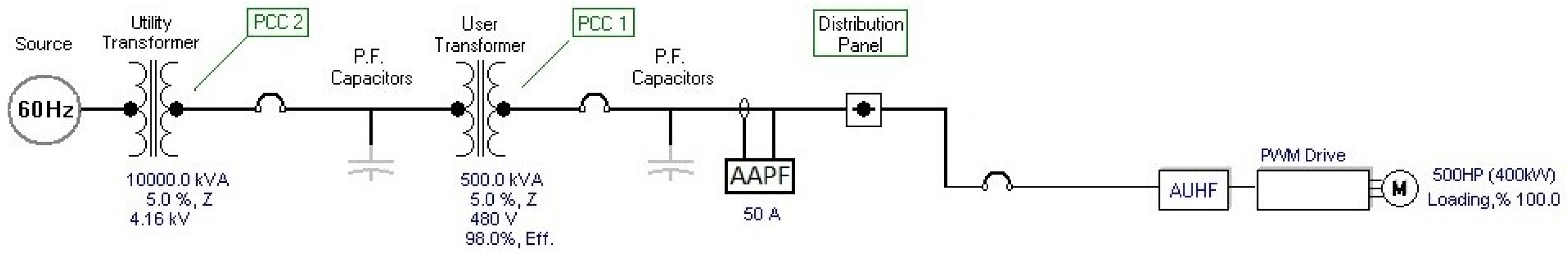

3. Test Setup

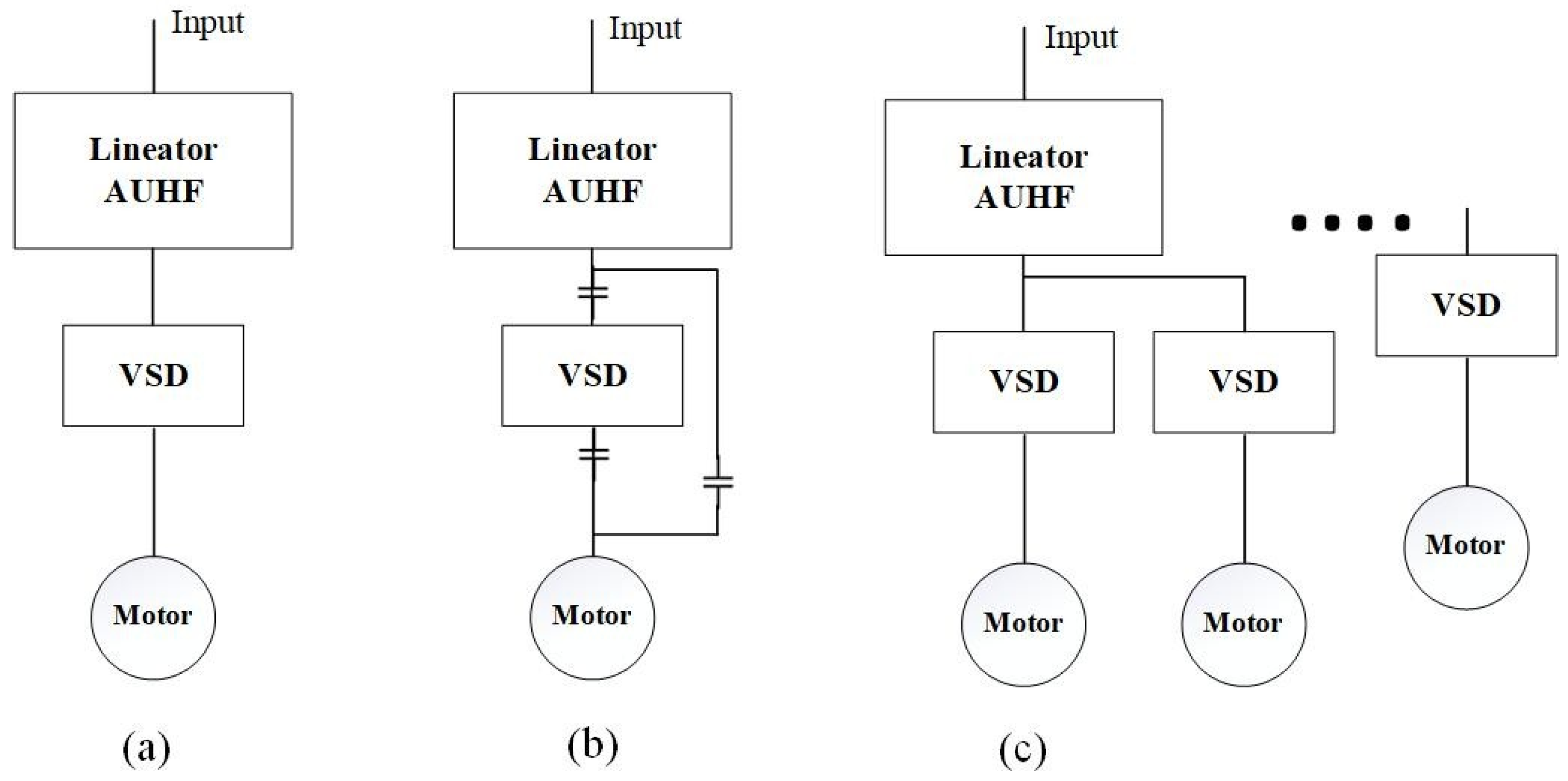

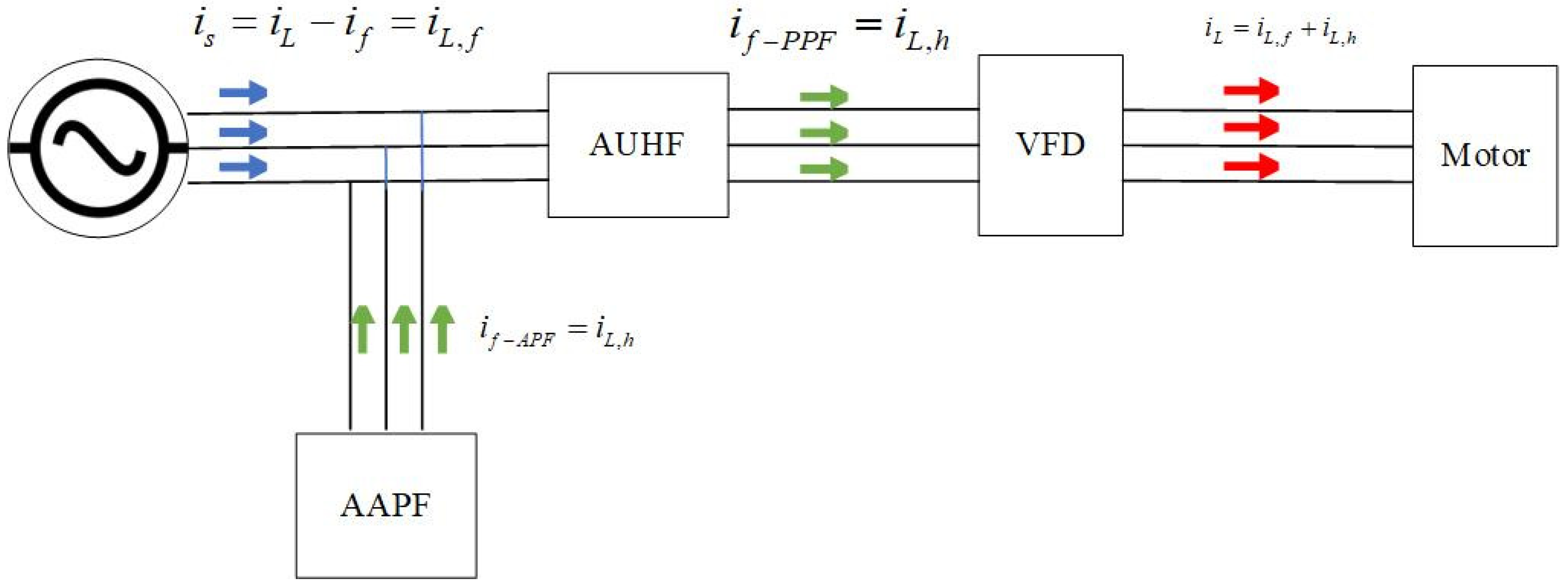

3.1. Test

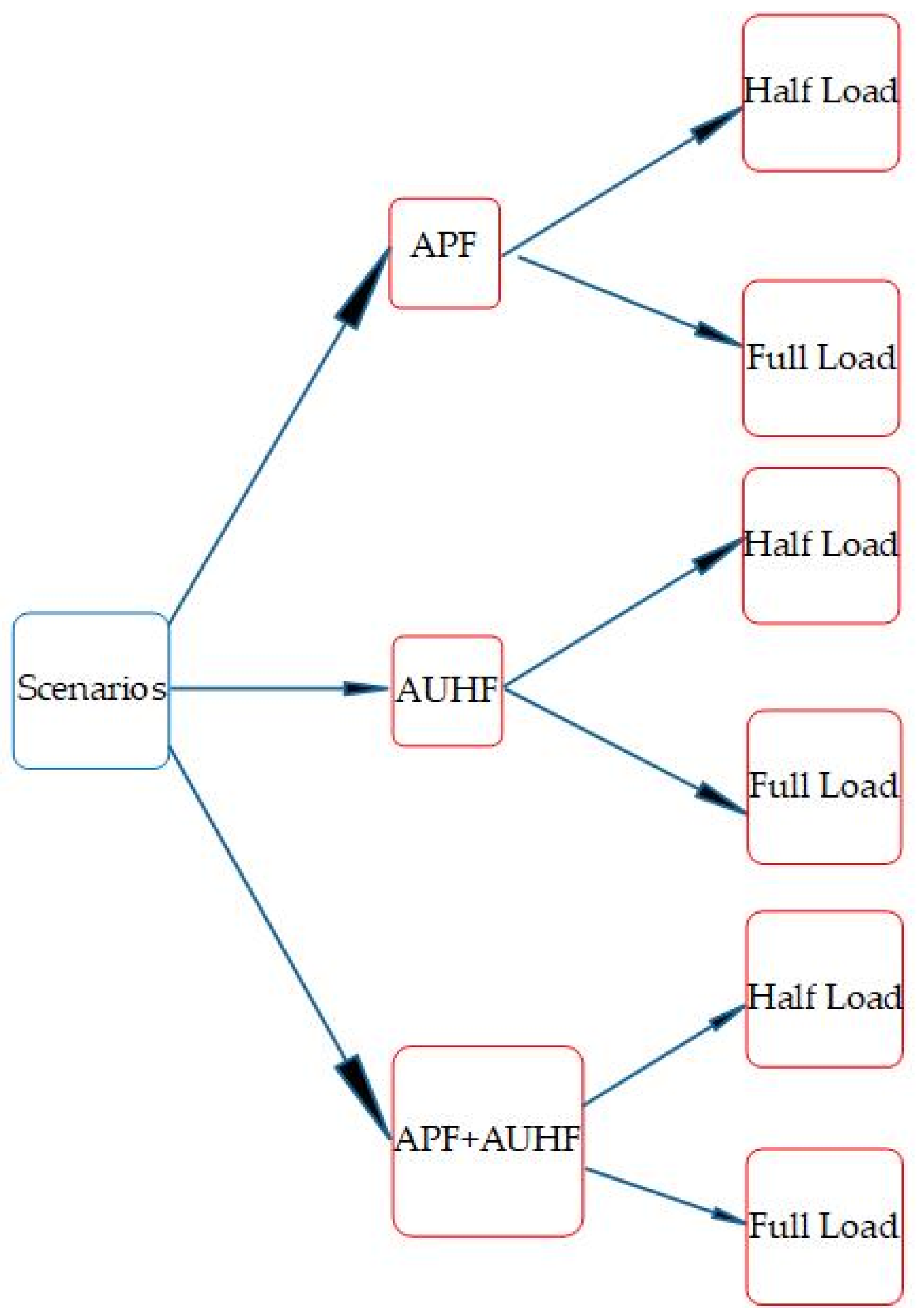

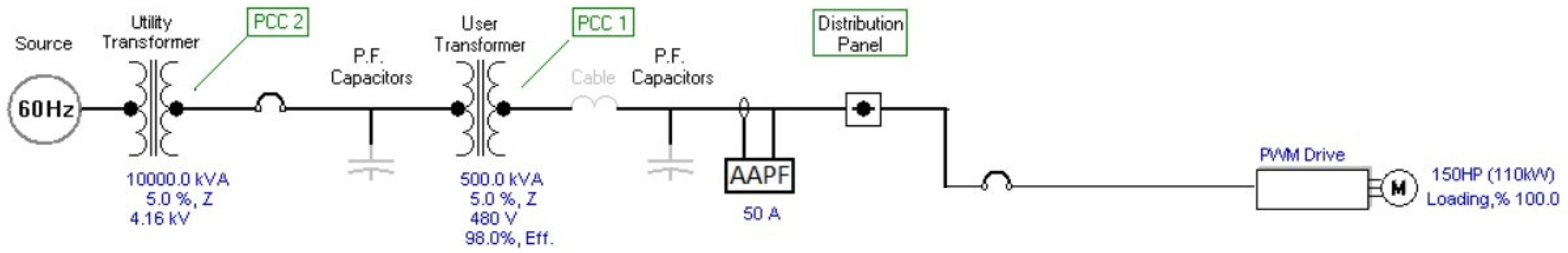

- APF Connection Only: Connect only the APF to the network and investigate its impact on the network under half-load and full-load conditions.

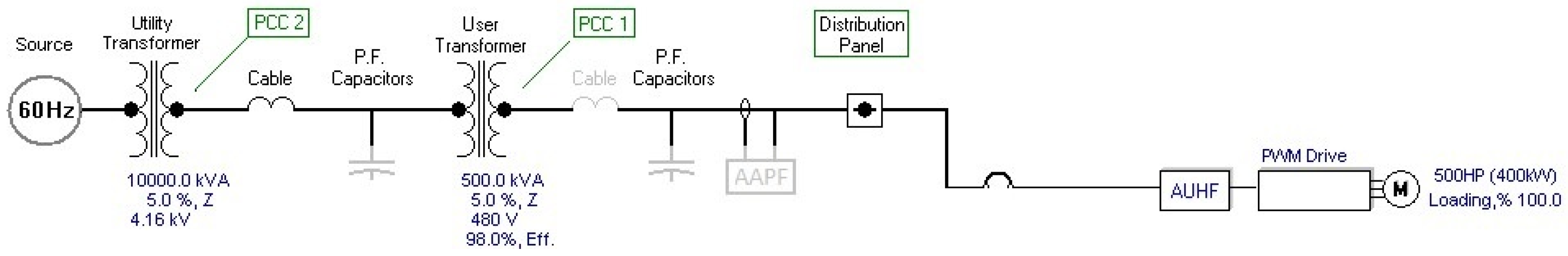

- AUHF Connection Only: Connect only the AUHF to the network and investigate its impact on the network under half-load and full-load conditions.

- Hybrid Connection: Connect the APF upstream of the AUHF filter and investigate the impact of this hybrid connection on the network under half-load and full-load conditions.

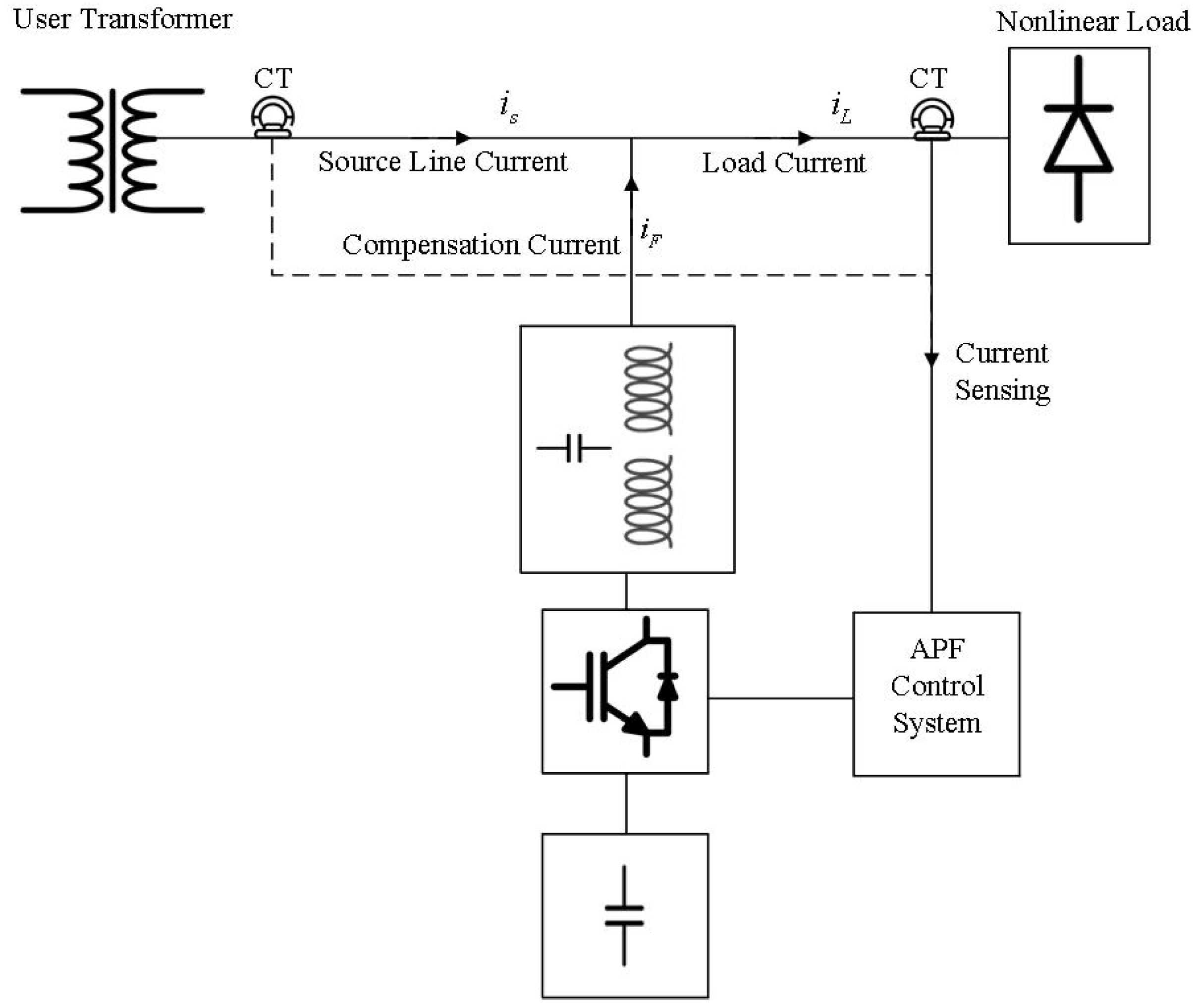

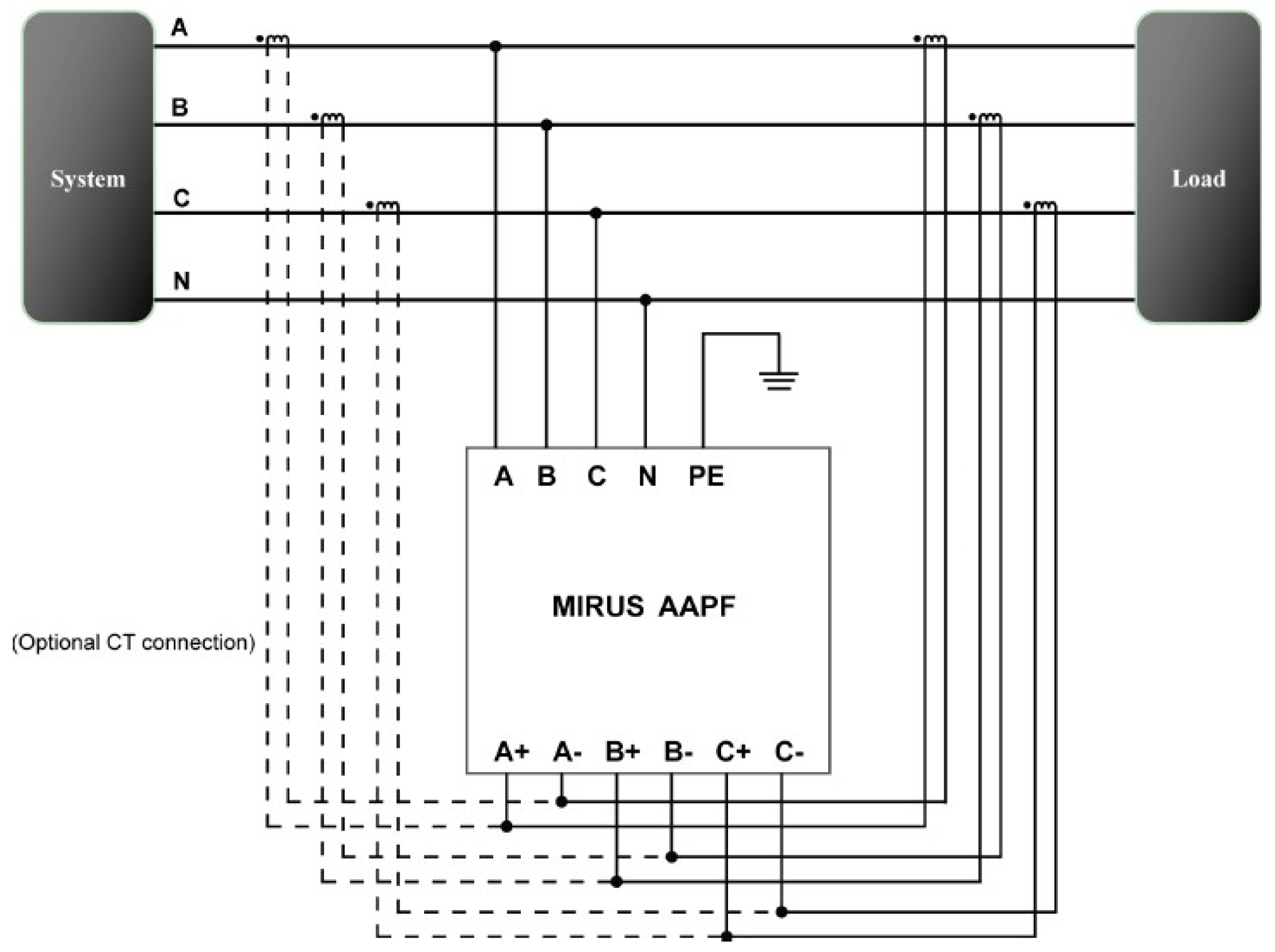

3.2. APF

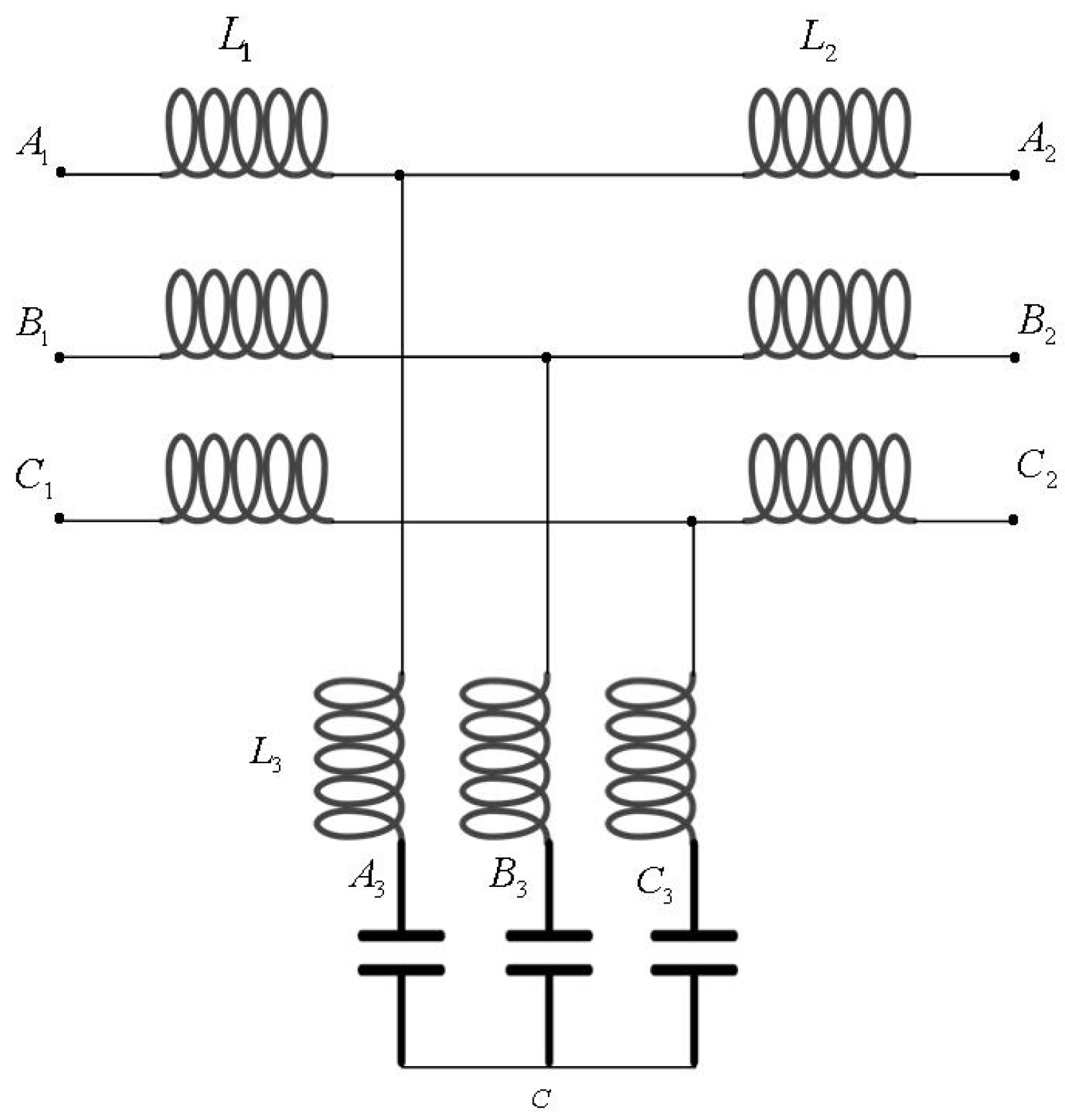

3.3. PPF

3.4. Hybrid (APF + AUHF)

4. Tests and Results

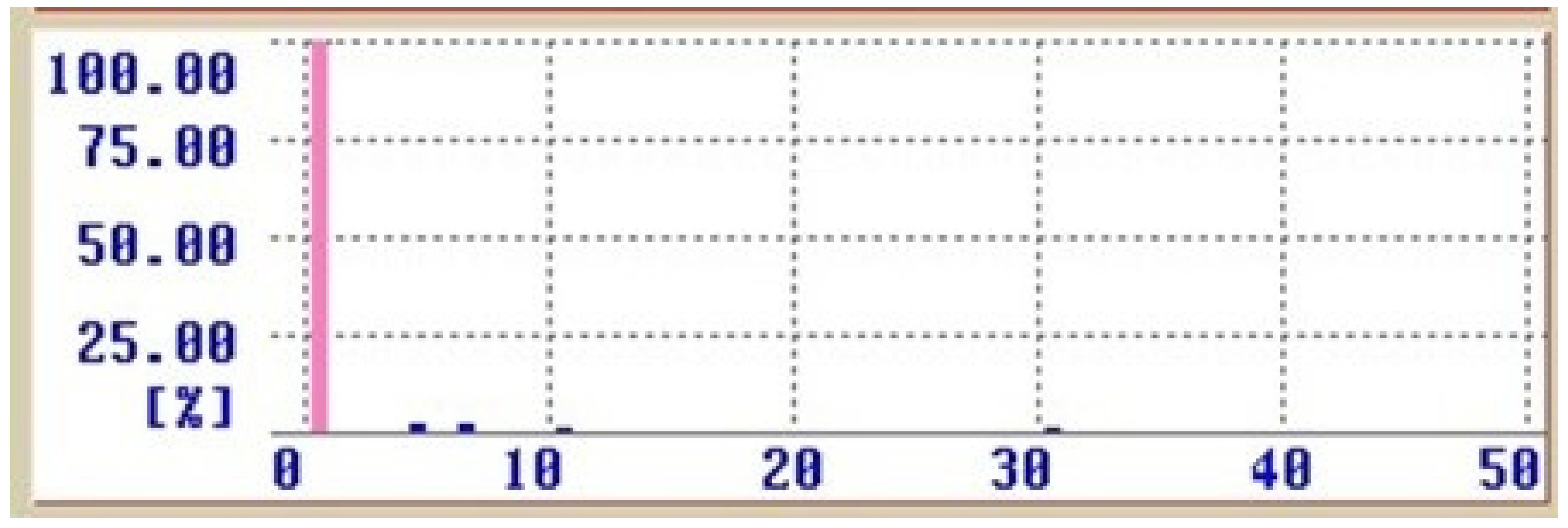

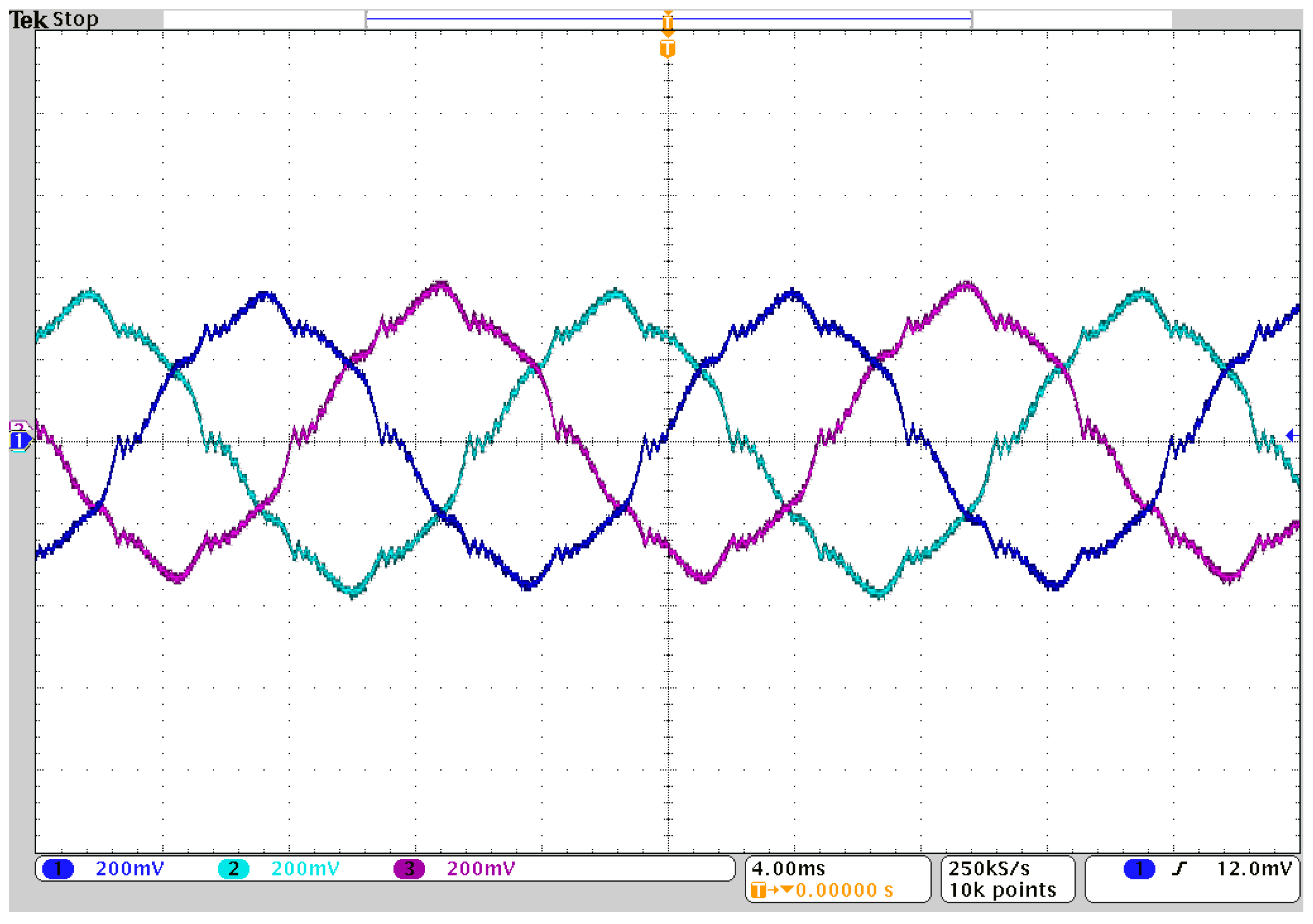

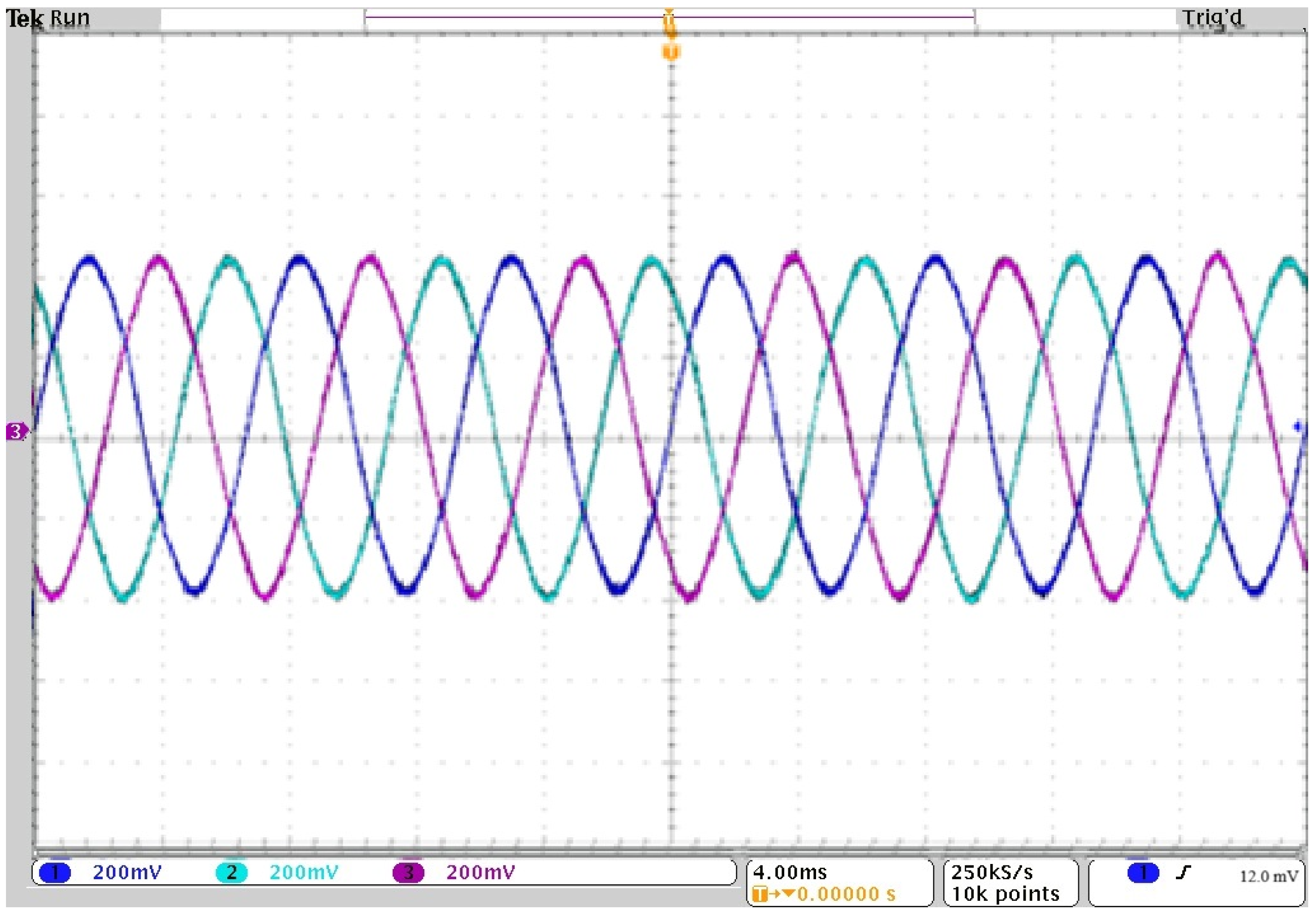

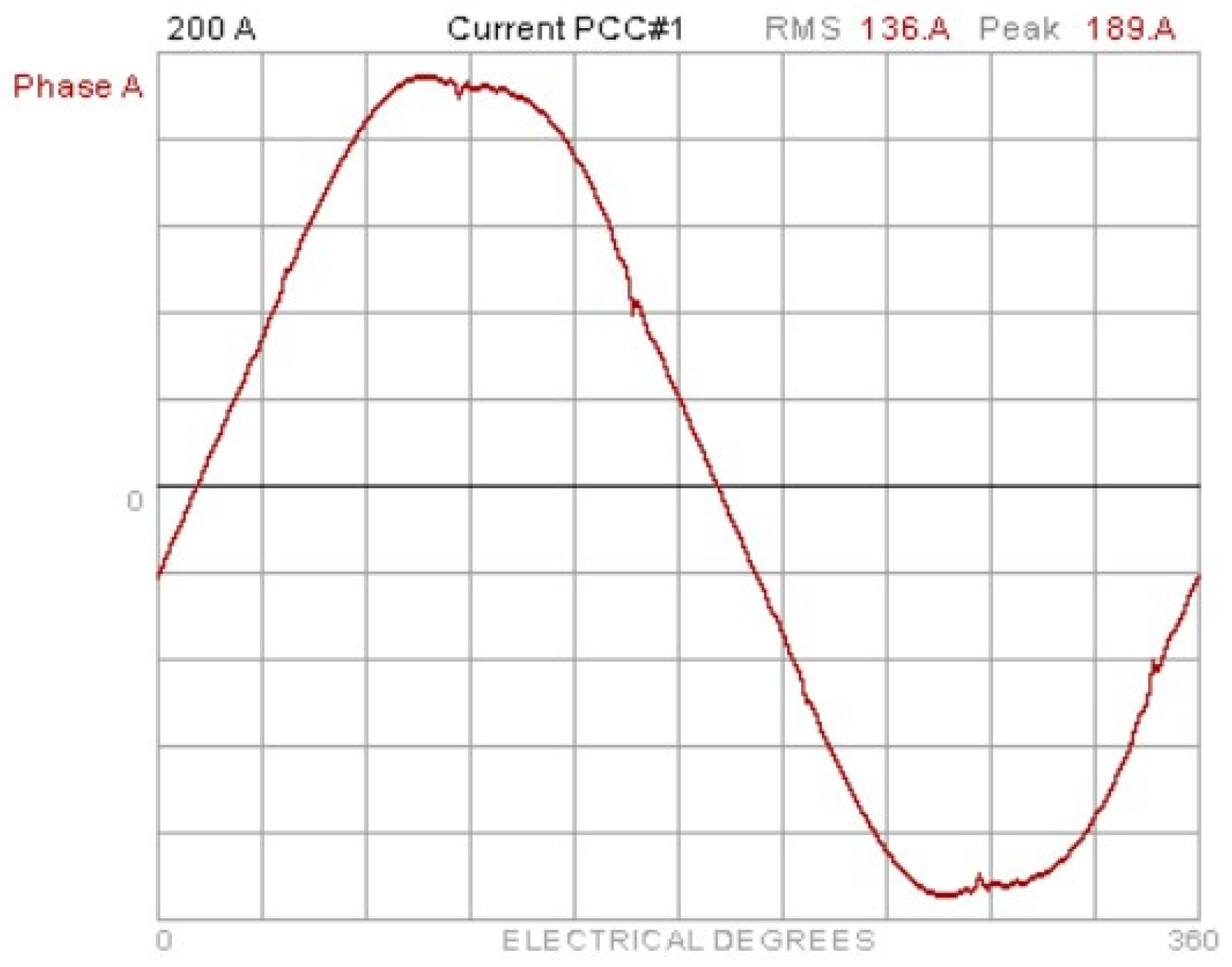

4.1. TEST1 (APF Half/Full Load)

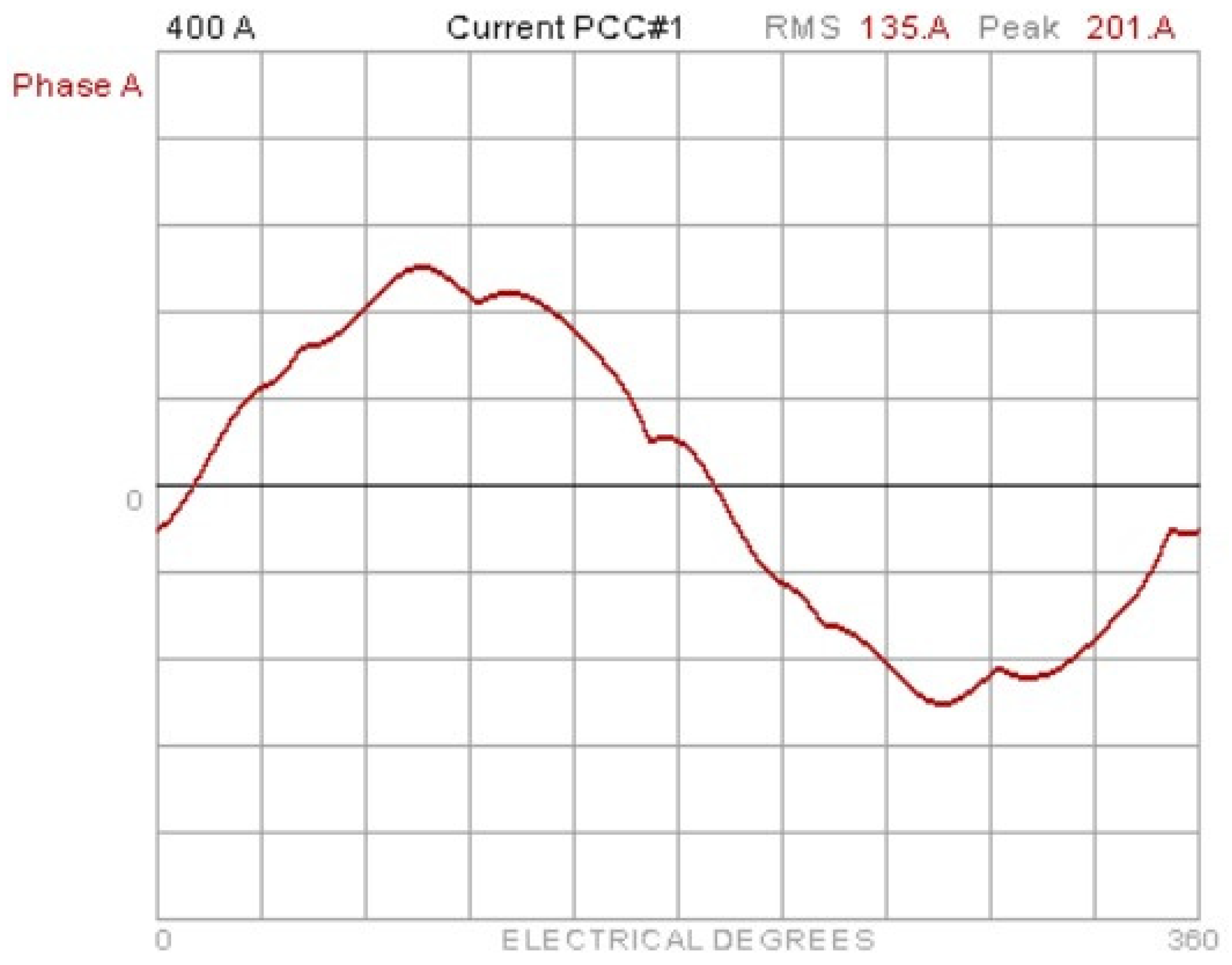

4.2. TEST2 (AUHF Half/Full Load)

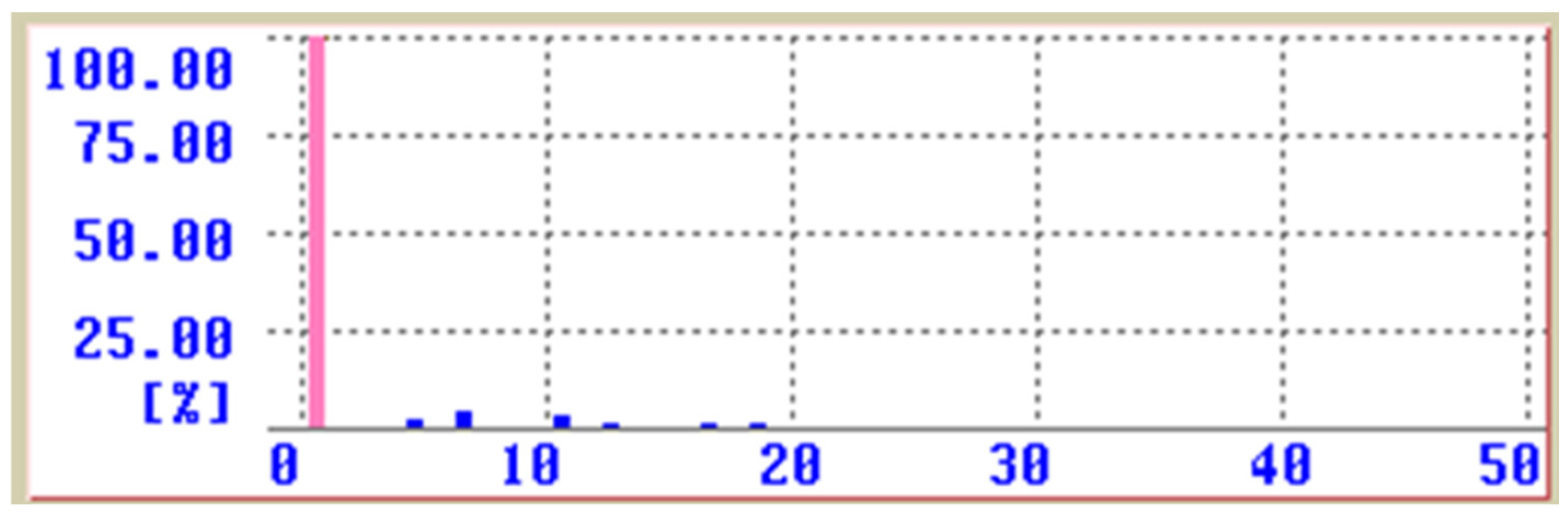

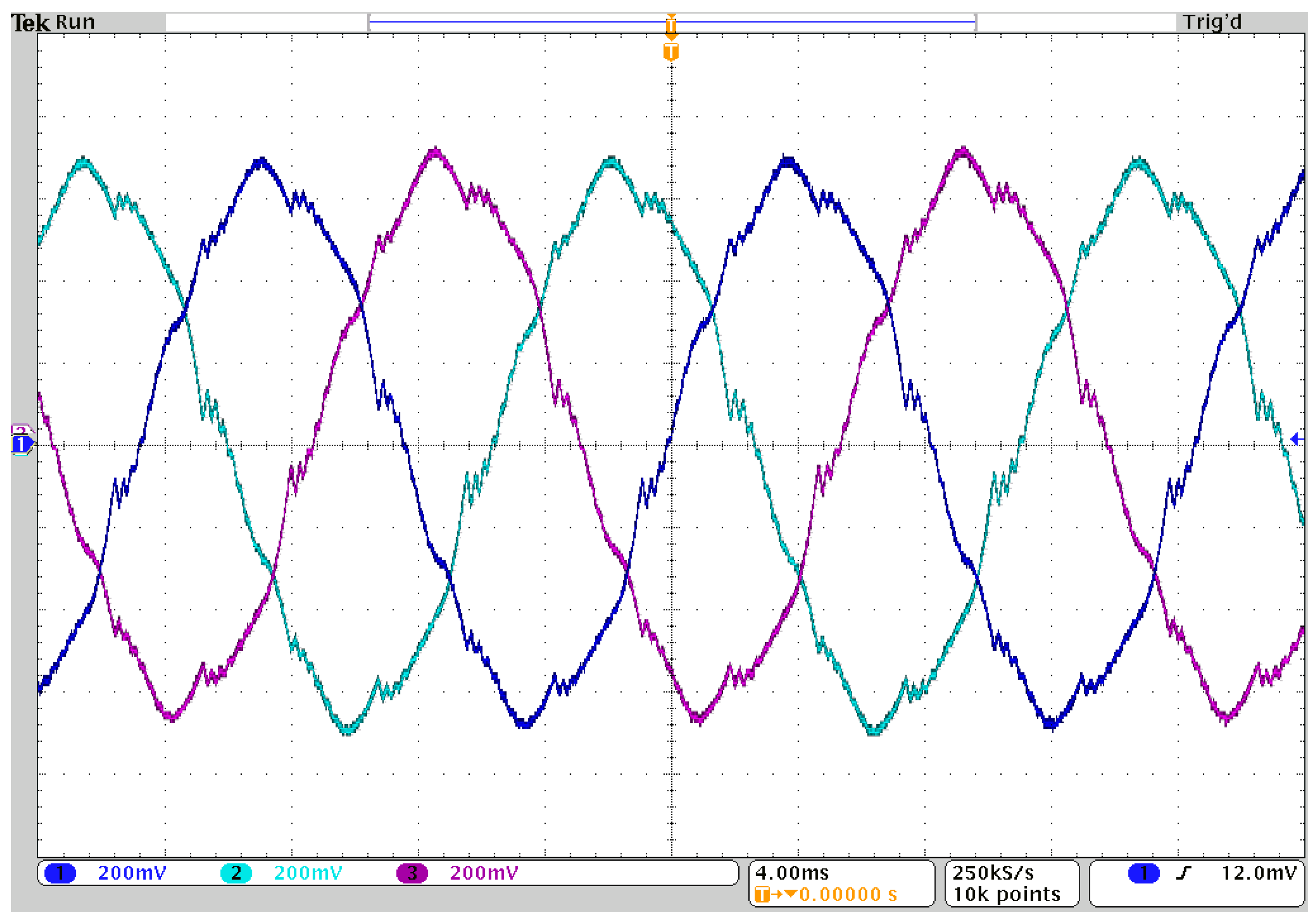

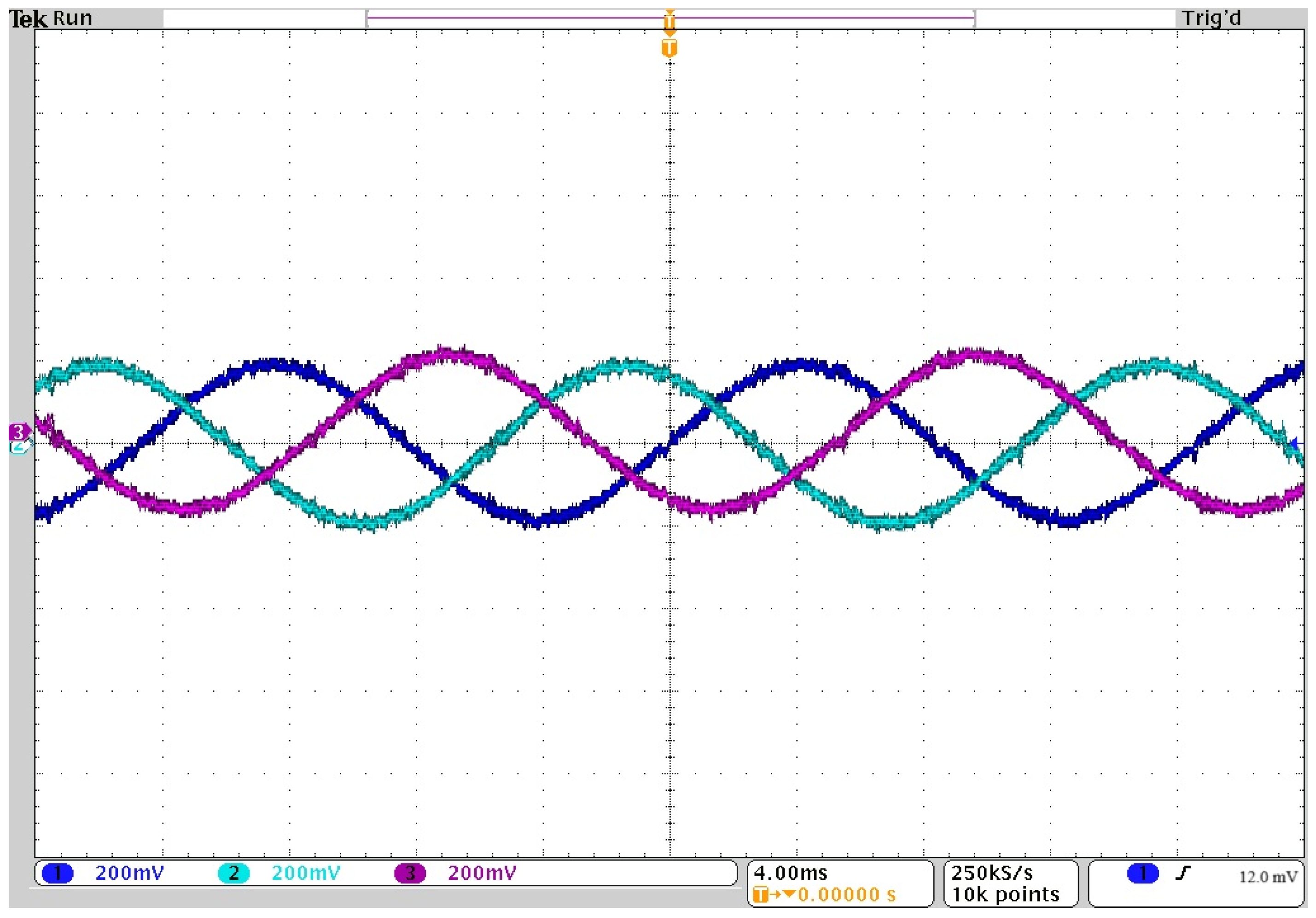

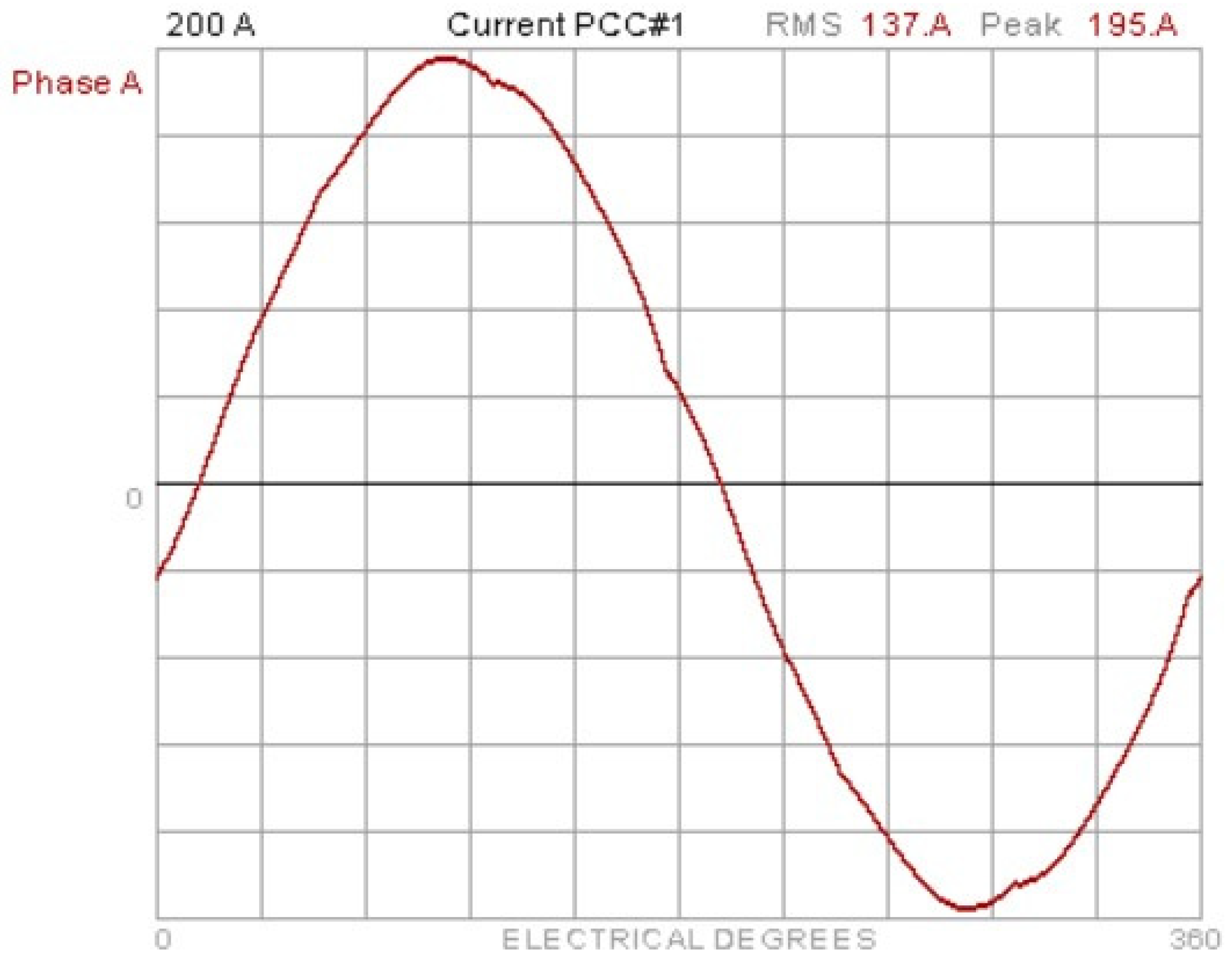

4.3. TEST3 (Hybrid Configuration: APF + AUHF Half/Full Load)

5. Discussion

5.1. Simulation Validation

5.2. Comparative Analysis

- Test 1 (APF Half/Full Load):

- Half Load: The variable frequency drive was set to 60.23 Hz, causing the motor to draw 130 A. The APF injected 25 A of harmonic current, reducing the THDi to 7.2%.

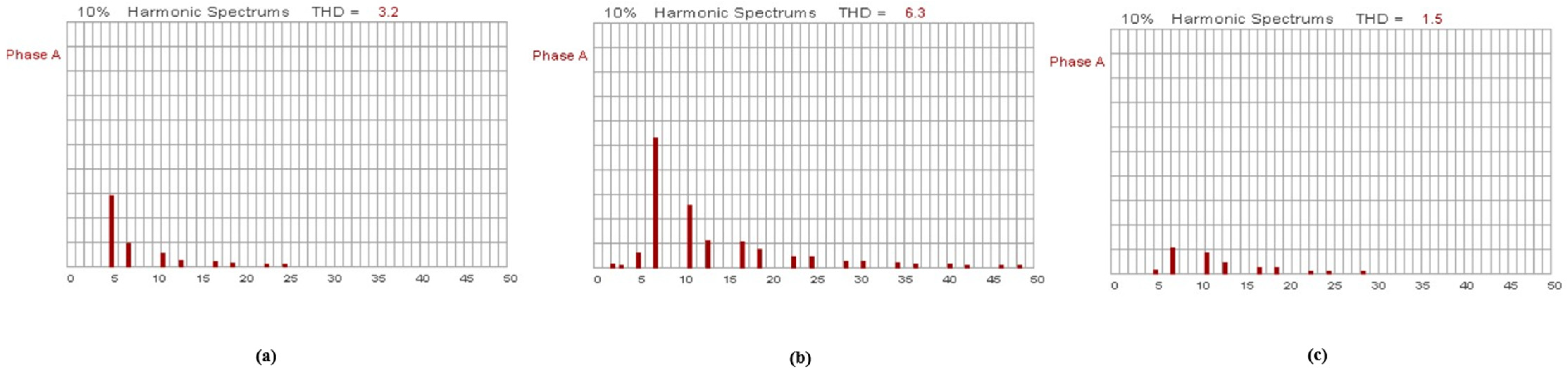

- Full Load: With the VFD adjusted to 60.45 Hz, the motor drew 150 A, prompting the APF to inject its full nominal current of 50 A. This adjustment resulted in a THDi reduction to 3.4%.

- Test 2 (AUHF Half/Full Load):

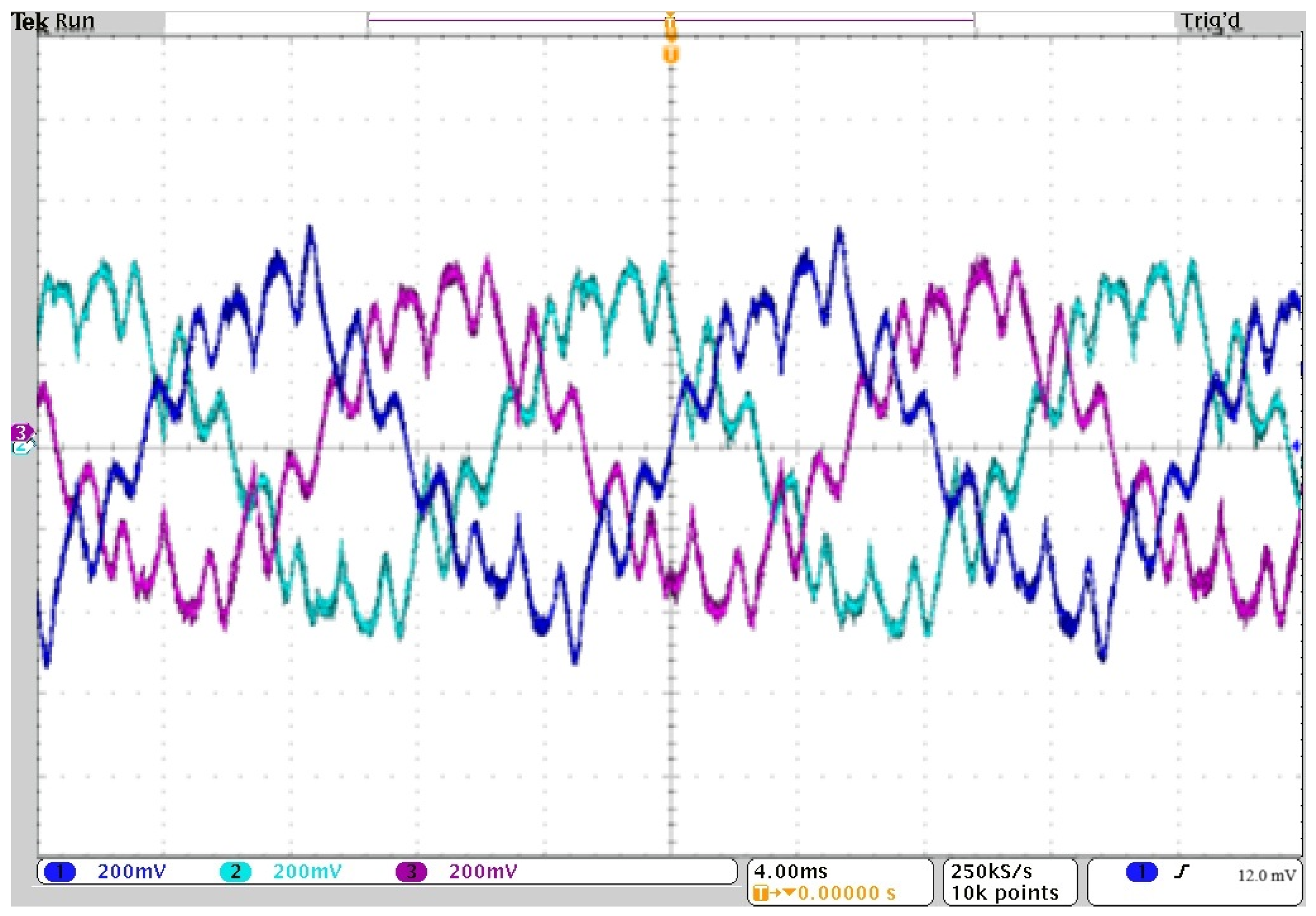

- Half Load: The VFD was set to 60.23 Hz, causing the motor to draw 130 A. The AUHF operated at half load, filtering harmonic currents and achieving a THDi of 8.0%.

- Full Load: With the VFD adjusted to 60.45 Hz, the motor drew 150 A, and the AUHF filtered its full nominal current. This resulted in a THDi reduction to 6.3%.

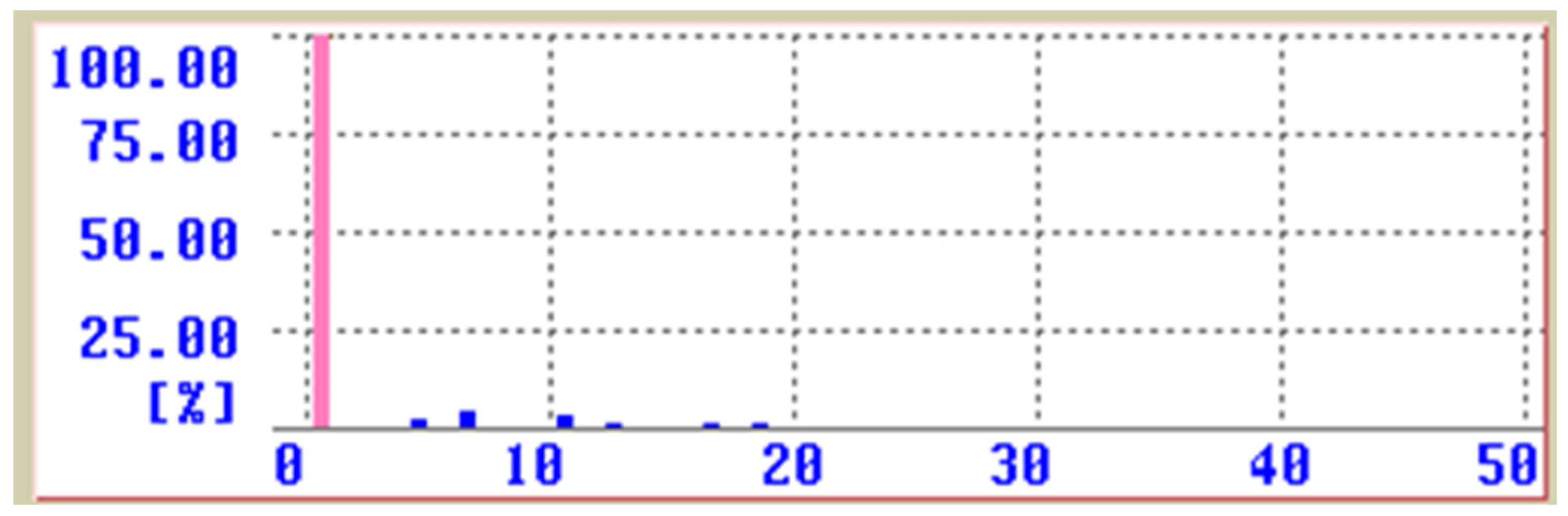

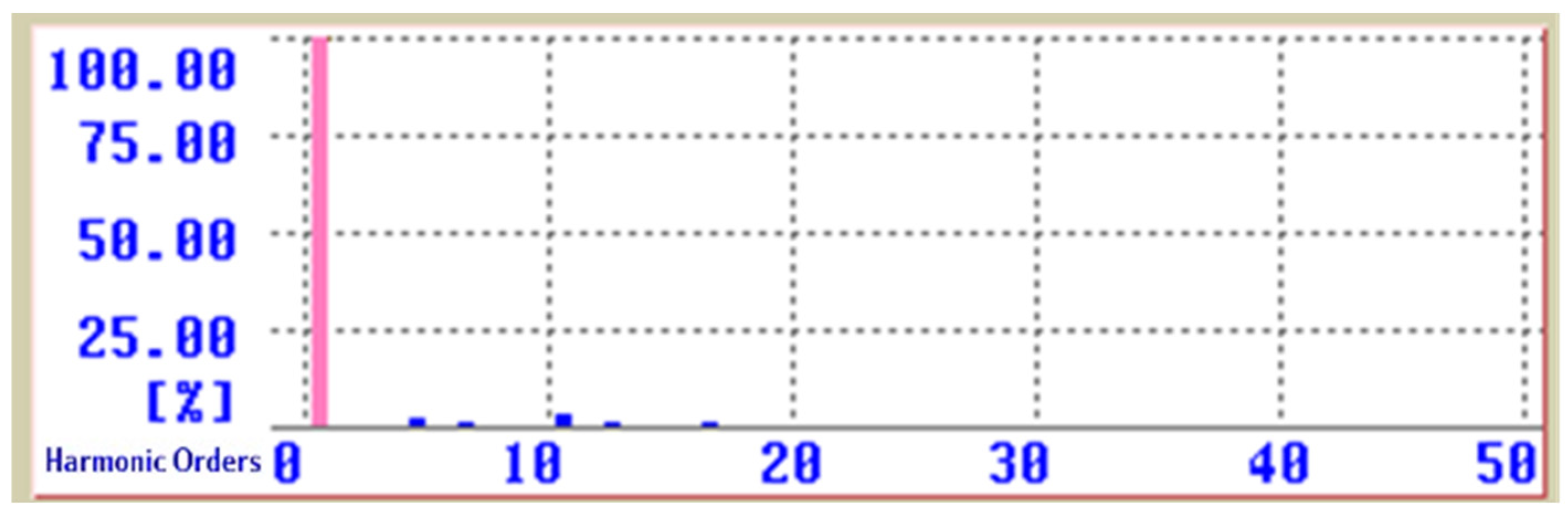

- Test 3 (Hybrid Configuration: APF + AUHF Half/Full Load):

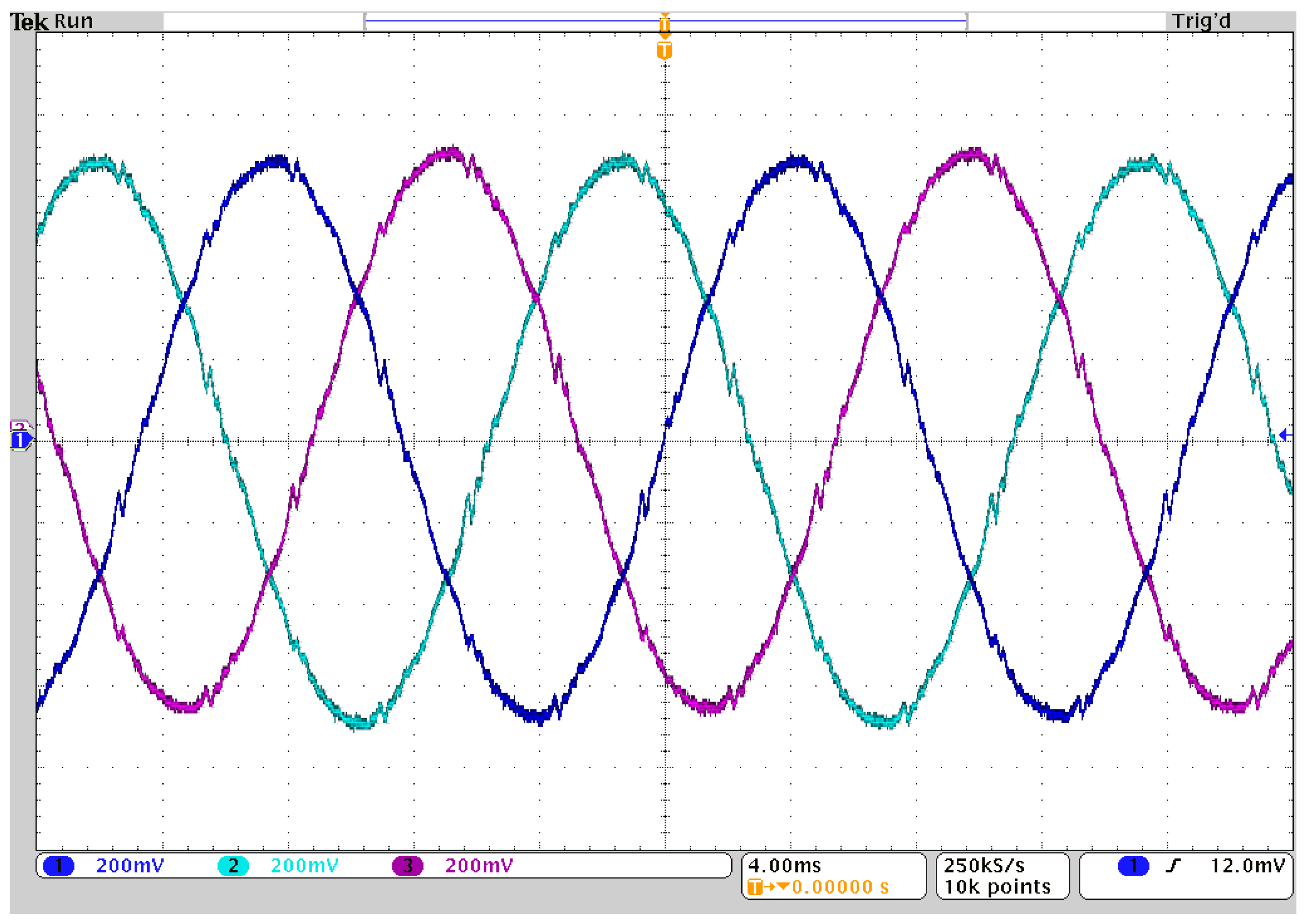

- Half Load: The VFD was set to 60.23 Hz, causing the motor to draw 130 A. Under these conditions, the APF injected 25 A while the AUHF provided complementary harmonic filtering, achieving a THDi of 1.8%.

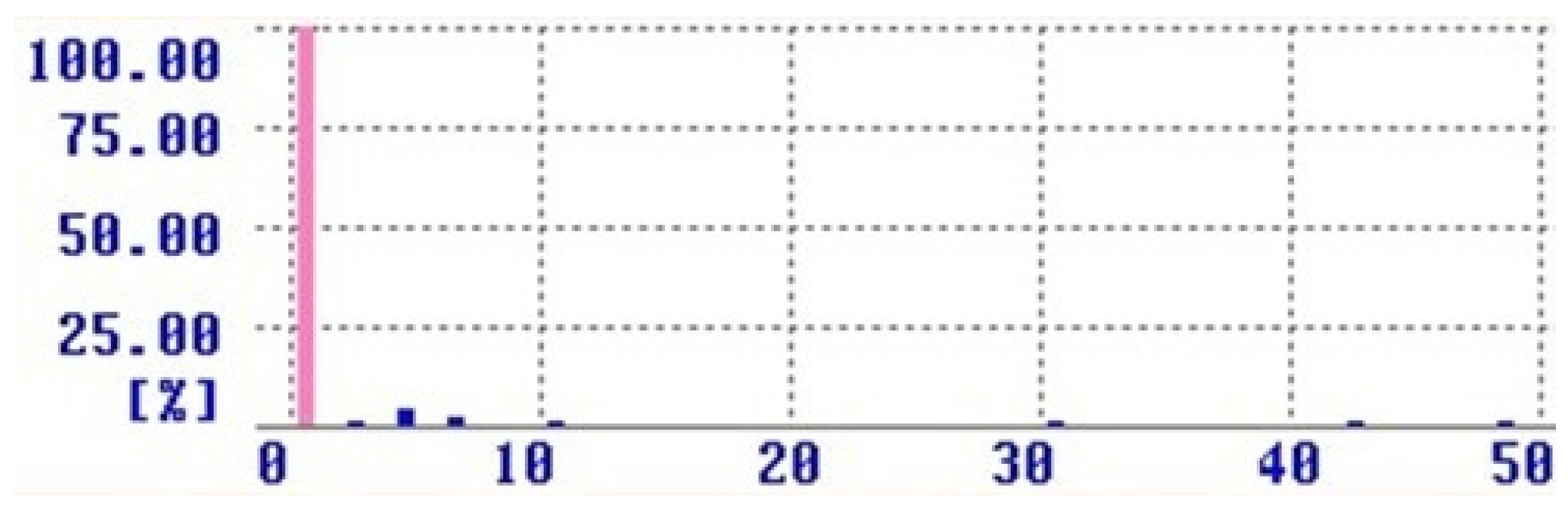

- Full Load: With the VFD adjusted to 60.45 Hz, the motor drew 150 A. The APF injected its full nominal current of 50 A, while the AUHF continued to filter additional harmonics. This resulted in a THDi reduction to 1.2%.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arranz-Gimon, A.; Zorita-Lamadrid, A.; Morinigo-Sotelo, D.; Duque-Perez, O. A review of total harmonic distortion factors for the measurement of harmonic and interharmonic pollution in modern power systems. Energies 2021, 14, 6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalair, A.; Abas, N.; Kalair, A.R.; Saleem, Z.; Khan, N. Review of harmonic analysis, modeling and mitigation techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 1152–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otcenasova, A.; Bolf, A.; Altus, J.; Regula, M. The influence of power quality indices on active power losses in a local distribution grid. Energies 2019, 12, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Zhuo, F.; Zhu, C.; Yi, H.; Wang, Z.; Tao, R.; Wei, T. An optimal compensation method of shunt active power filters for system-wide voltage quality improvement. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Beres, R.N.; Wang, X.; Liserre, M.; Blaabjerg, F.; Bak, C.L. A review of passive power filters for three-phase grid-connected voltage-source converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2015, 4, 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, S.A.; Negrão, F.A. Single-phase to three-phase unified power quality conditioner applied in single-wire earth return electric power distribution grids. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 3950–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, L.; Faúndes, N. Active/passive harmonic filters: Applications, challenges & trends. In Proceedings of the 2016 17th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 16 October 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 657–662. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeri, S.; Esmaeili, S.; Koochi, M.H. Passive harmonic filter design considering voltage sag performance-applicable to large industries. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 37, 1714–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, M.J.; Raicevic, S.S.; Klimenta, D.O.; Raicevic, N.B.; Perovic, B.D. Determination of optimal locations and parameters of passive harmonic filters in unbalanced systems using the multiobjective genetic algorithm. Elektronika ir Elektrotechnika 2024, 30, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.M.; Chou, C.J.; Lu, C.T.; Hsiao, Y.T. Optimal design of single-tuned filters for industrial power systems to reduce harmonic distortion using forest algorithm. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 2024, 47, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latoufis, K.C.; Vassilakis, A.I.; Grapsas, I.K.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Design Optimization and Performance Evaluation of Passive Filters for Acoustic Noise Mitigation in Locally Manufactured Small Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 4350–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirus International Inc. Available online: https://www.mirusinternational.com/downloads/MIRUS-WP003-A-Practical-and-Effective-Way-of-Applying-IEEEStd519-Harmonic-Limits.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Melo, I.D.; Pereira, J.L.; Variz, A.M.; Ribeiro, P.F. Allocation and sizing of single tuned passive filters in three-phase distribution systems for power quality improvement. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 180, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleybar, H.J.; Davoodi, M.; Brenna, M.; Zaninelli, D. Applications of genetic algorithm and its variants in rail vehicle systems: A bibliometric analysis and comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 68972–68993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, S. Harmonics mitigation of stand-alone photovoltaic system using LC passive filter. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 2389–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhan, P.S.; Ray, P.K.; Pottapinjara, S. Performance analysis of shunt active filter for harmonic compensation under various non-linear loads. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2021, 22, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, P.P.; Suganthan, P.N.; Amaratunga, G.A. Minimizing harmonic distortion in power system with optimal design of hybrid active power filter using differential evolution. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 61, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sou, W.K.; Chao, C.W.; Gong, C.; Lam, C.S.; Wong, C.K. Analysis, design, and implementation of multi-quasi-proportional-resonant controller for thyristor-controlled LC-coupling hybrid active power filter (TCLC-HAPF). IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Shon, J. Sensorless AC capacitor voltage monitoring method for HAPF. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 15514–15524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taya, B.B.; Ahammad, A.; Jahin, F.I. Total harmonic distortion mitigation and voltage control using distribution static synchronous compensator and hybrid active power filter. Int. J. Adv. Technol. Eng. Explor. 2024, 11, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazaeli, M.H.; Keramat, M.M.; Alipour, H.; Khodabakhsi-javinani, N. Effects of Electric Vehicles Battery on The Harmonic Distortion of HVDC Lines by Active Filter. In Proceedings of the 2020 15th International Conference on Protection and Automation of Power Systems (IPAPS), Shiraz, Iran, 30 December 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Špelko, A.; Blažič, B.; Papič, I.; Herman, L. Active filter reference calculations based on customers’ current harmonic emissions. Energies 2021, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, G. Harmonic detection method based on adaptive noise cancellation and its application in photovoltaic-active power filter system. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 184, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakhtii, O.; Nerubatskyi, V.; Scherbak, Y.; Mashura, A.; Khomenko, I. Energy efficiency criterion of power active filter in a three-phase network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE KhPI Week on Advanced Technology (KhPIWeek), Kharkiv, Ukraine, 5 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Alhasheem, M.; Mattavelli, P.; Davari, P. Harmonics mitigation and non-ideal voltage compensation utilising active power filter based on predictive current control. IET Power Electron. 2020, 13, 2782–2793. [Google Scholar]

- Kritsanasuwan, K.; Leeton, U.; Kulworawanichpong, T. Harmonic mitigation of AC electric railway power feeding system by using single-tuned passive filters. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 519; IEEE Recommended Practice and Requirements for Harmonic Control in Electric Power Systems. IEEE Standards Association: New York, NY, USA, 2014.

- Buso, S.; Malesani, L.; Mattavelli, P.; Veronese, R. Design and fully digital control of parallel active filters for thyristor rectifiers to comply with IEC-1000-3-2 standards. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2002, 34, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, Z.; Cheng, T.P.; Jusoh, A. Review of Active Power Filter Technologies; The Institution of Engineers: Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, 2007; Volume 68. [Google Scholar]

- Saadat, H. Power System Analysis; McGraw-hill: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, N.; Undeland, T.M.; Robbins, W.P. Power Electronics: Converters, Applications, and Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleybar, H.J.; Kojabadi, H.M.; Foiadelli, F.; Brenna, M.; Blaabjerg, F. Model analysis and real-time implementation of model predictive control for railway power flow controller. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 109, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Chandra, A.; Al-Haddad, K. Power Quality: Problems and Mitigation Techniques; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, J.; Brandl, R.; Vishwanath, K.; Johnson, J.; Darbali-Zamora, R.; Summers, A.; Hashimoto, J.; Kikusato, H.; Ustun, T.S.; Ninad, N.; et al. Advanced laboratory testing methods using real-time simulation and hardware-in-the-loop techniques: A survey of smart grid international research facility network activities. Energies 2020, 13, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 1159; IEEE Recommended Practice for Monitoring Electric Power Quality. IEEE Standards Association: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- IEEE Std 1459; IEEE Standard Definitions for the Measurement of Electric Power Quantities under Sinusoidal, Nonsinusoidal, Balanced, or Unbalanced Conditions. IEEE Standards Association: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- Underwriters Laboratories. Available online: https://www.shopulstandards.com/ProductDetail.aspx?UniqueKey=47339 (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- UL 508A; Standard for Industrial Control Panels. Underwriters Laboratories: Northbrook, IL, USA, 2018.

- UL 1012; Standard for Power Units Other than Class 2. Underwriters Laboratories: Northbrook, IL, USA, 2018.

- UL 1741; Standard for Inverters, Converters, Controllers and Interconnection System Equipment for Use with Distributed Energy Resources. Underwriters Laboratories: Northbrook, IL, USA, 2010.

- CSA C22.2 No. 14; Industrial Control Equipment. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018.

- CSA C22.2 No. 107.1; General Use Power Supplies. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018.

- CSA C22.2 No. 286; Standard for Adjustable Speed Drives. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010.

- Canadian Standards Association. Available online: https://www.csagroup.org/standards/standards-research/ (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- American Bureau of Shipping. Available online: https://ww2.eagle.org/en/rules-and-resources/rules-and-guides/archives.html (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- International Organization for Standardization. Standards. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standards.html (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- ISO 9001; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Davoodi, M.; Bevrani, H. A new application of the hardware in the loop test of the min–max controller for turbofan engine fuel control. Adv. Control Appl. Eng. Ind. Syst. 2023, 5, e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirus International Inc. Available online: https://www.mirusinternational.com/ (accessed on 11 January 2026).

| Ref. | Year | Key Benefit | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | 2021 | Novel passive filter design for LCI drives. Addresses detuning, resonance elimination, and harmonic loading. | Very expensive. |

| [9] | 2024 | Optimal placement and sizing of passive filters. Nonlinear multi-objective optimization approach. | Does not tackle current total harmonic distortion. |

| [10] | 2024 | Forest growth model algorithm for filter design. Accounts for passive filter component and system parameter variations. | Best-case scenario does not accurately reflect real-world conditions. |

| [11] | 2024 | Optimizes L-RLC filter for minimal distortion and stable voltage. Field tested for performance. | Specific application may not be broadly applicable. |

| [16] | 2021 | dq-Proportional Resonant control for distortion elimination. Significant THDi mitigation. | Laboratory prototype only. Not representative of real-world conditions. |

| [17] | 2017 | Optimal algorithm for parameter adaptation. Gradually reduces population size. | Effectiveness is influenced by grid disturbances, voltage fluctuations, and environmental conditions. |

| [18] | 2021 | Low DC-link voltage. Extended operational range. Simultaneous compensation for reactive power, harmonics, and unbalanced power. | Complex multi-quasi-proportional-resonant controller. |

| [19] | 2023 | Monitors AC capacitor voltage without additional sensors. Prevents AC capacitor burnout. | Minor average discrepancy between measured and predicted voltages. |

| [20] | 2024 | APF outperforms D-STATCOM in various parameters. Effective MATLAB/Simulink simulation results. | Industry needs mitigation up to the 50th or 100th harmonic order. |

| [21] | 2020 | Uses PHEVs in V2G mode to prevent harmonic distortion. Manages switching of PHEV converters. | Dependent on the state of charge of PHEV batteries. |

| [22] | 2021 | Focuses on customer contributions to harmonic distortion. Minimizes required APF power. | Inadequate compensation if reference harmonic impedance does not match actual impedance. |

| [23] | 2020 | Balances convergence speed and steady-state accuracy. Sliding integrator and L2 norm-based step size iteration. | Specific to PV-APF systems. |

| [24] | 2020 | Analyzes energy-saving impact of parallel APF. Evaluates power losses and harmonic compensation. | May reduce network power efficiency. May introduce voltage distortion. |

| [25] | 2020 | Improved control structure for SAPFs. Reduces current ripple via efficient cost function. | Focused on nonlinear loads and unbalanced voltages in microgrids. |

| [26] | 2022 | Simulates impact of harmonics on electric train substation. Measures THD of voltage and current. | Only the 11th filter effective in maintaining THD within standard limits. |

| This Study | 2025 | Significant Harmonic Mitigation (1.2% THDi). Innovative Configuration. Real-Time Field Testing. High Precision in Measurements. | - |

| Bus Voltage | Individual Harmonic (%) | THD (%) |

|---|---|---|

| V ≤ 1.0 kV | 5.0 | 8.0 |

| 1 kV < V ≤ 69 kV | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| 69 kV < V ≤ 161 kV | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| 161 kV < V | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| Standard | Subject |

|---|---|

| UL 508A [38] | Industrial Control Panels. |

| UL 1012 [39] | Power Units Other Than Class 2. |

| UL 1741 [40] | Inverters, Converters, Controllers, and Interconnection System Equipment for Use with Distributed Energy Resources. |

| R | Component | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | APF | Mirus International AAPF, 50 A, 480 V, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 2 | APF’s HMI | Mirus International, LCD touchscreen, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 3 | APF Main CT, Side | Acrel, 800/5 A, Source Side, Shanghai, China |

| 4 | Measurement Device—Power Analyzer | Hioki (PQ3198), Ueda, Japan |

| 5 | Measurement Device—oscilloscope | Tektronix (DPO4014B), Beaverton, OR, USA |

| 6 | Measurement Device—Current Clamps | AEMC SR600 AC, 1000 A, Dover, DE, USA Hioki CT7136 (600 A)/9661, Ueda, Japan |

| 7 | Autotransformer | Mirus International, 600 V–480 V, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 8 | VFD | Siemens 150 HP, Munich, Germany, Allen-Bradley 300 HP, Milwaukee, WI, USA |

| 9 | Cabling | Connection between VFD and Motors |

| 10 | M-G Set | Lincguard, 325 HP, Catharines, ON, Canada |

| 11 | Input Voltage (Line-to-Line) | 480 VAC |

| Rows | Element | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | THDi (%) | 3.4 |

| 2 | Phase Voltage | 277 |

| R | Component | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AUHF | Mirus International AUHF, 450 HP, 480 V, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 2 | Measurement Device-Power Analyzer | Hioki (PQ3198), Ueda, Japan |

| 3 | Measurement Device-oscilloscope | Tektronix (DPO4014B), Beaverton, OR, USA |

| 4 | Measurement Device—Current Clamps | AEMC SR600 AC, 1000 A, Dover, DE, USA, Hioki CT7136 (600 A)/9661, Ueda, Japan |

| 5 | Autotransformer | Mirus International, 600 V–480 V, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 6 | VFD | Siemens 150 HP, Allen-Bradley 300 HP, Munich, Germany, Fuji Electric 200 HP, Tokyo, Japan |

| 7 | Cabling | Connection between VFD and Motors |

| 8 | M-G Set | Lincguard, 525 HP, Catharines, ON, Canada |

| 9 | Input Voltage (Line-to-Line) | 480 VAC |

| Rows | Element | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | THDi (%) | 8.0 |

| 2 | Phase Voltage | 277 |

| Rows | Element | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | THDi (%) | 6.3 |

| 2 | Phase Voltage | 277 |

| R | Component | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | APF | Mirus International AAPF, 50 A, 480 V, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 2 | APF’s HMI | Mirus International, LCD touchscreen, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 3 | AUHF | Mirus International AUHF, 450 HP, 480 V, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 4 | APF main CT side | Acrel, 800/5 A, Source Side, Shanghai, China |

| 5 | Measurement Device-Power Analyzer | Hioki (PQ3198), Ueda, Japan |

| 6 | Measurement Device-oscilloscope | Tektronix (DPO4014B), Beaverton, OR, USA |

| 7 | Measurement Device—Current Clamps | AEMC SR600 AC, 1000 A, Dover, DE, USA Hioki CT7136 (600 A)/9661, Ueda, Japan |

| 8 | VFD | Allen-Bradley 300 HP, Fuji Electric 200 HP, Milwaukee, WI, USA |

| 9 | VFD | Siemens 150 HP, Munich, Germany |

| 10 | Autotransformer | Mirus International, 600 V–480 V, Brampton, ON, Canada |

| 11 | M-G Set | Lincguard, 525 HP, Catharines, ON, Canada |

| 12 | Cabling | Connection between VFD and Motors |

| 13 | Input Voltage (Line-to-Line) | 480 VAC |

| Rows | Element | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | THDi (%) | 1.8 |

| 2 | Phase Voltage | 277 |

| Rows | Element | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | THDi (%) | 1.2 |

| 2 | Phase Voltage | 277 |

| Test | Condition | VFD Frequency (Hz) | Voltage (V) | APF Current (A) | MOTOR Current (A) | AUHF Current (A) | THDi (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APF | Half Load | 60.23 | 480 | 25 | 130 | - | 7.2 |

| Full Load | 60.45 | 480 | 50 | 150 | - | 3.4 | |

| AUHF | Half Load | 60.23 | 480 | - | 130 | Half Load | 8.0 |

| Full Load | 60.45 | 480 | - | 150 | Full Load | 6.3 | |

| Hybrid | Half Load | 60.23 | 480 | 25 | 130 | Complementary | 1.8 |

| Full Load | 60.45 | 480 | 50 | 150 | Complementary | 1.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Davoodi, M.; Hoevenaars, P.; Kaleybar, H.J.; Brenna, M. Advanced Universal Hybrid Power Filter Configuration for Enhanced Harmonic Mitigation in Industrial Power Systems: A Field-Test Approach. Energies 2026, 19, 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030700

Davoodi M, Hoevenaars P, Kaleybar HJ, Brenna M. Advanced Universal Hybrid Power Filter Configuration for Enhanced Harmonic Mitigation in Industrial Power Systems: A Field-Test Approach. Energies. 2026; 19(3):700. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030700

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavoodi, Mohsen, Paul Hoevenaars, Hamed Jafari Kaleybar, and Morris Brenna. 2026. "Advanced Universal Hybrid Power Filter Configuration for Enhanced Harmonic Mitigation in Industrial Power Systems: A Field-Test Approach" Energies 19, no. 3: 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030700

APA StyleDavoodi, M., Hoevenaars, P., Kaleybar, H. J., & Brenna, M. (2026). Advanced Universal Hybrid Power Filter Configuration for Enhanced Harmonic Mitigation in Industrial Power Systems: A Field-Test Approach. Energies, 19(3), 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030700