1. Introduction

The rapid growth of distributed energy resources (DERs), especially photovoltaic (PV) generation and battery energy storage systems (BESSs), is transforming conventional distribution networks into more flexible and decentralized microgrids. Microgrids can operate either grid-connected or in islanded mode and are expected to enhance reliability, resiliency, and local utilization of renewable energy. However, as inverter-based resources replace synchronous machines, the short-circuit behavior and protection requirements of these systems become fundamentally different from those of traditional distribution systems. Recent review papers consistently point out that reduced fault levels, bidirectional power flows, and frequent changes in topology and operating mode complicate protection coordination in microgrids [

1,

2,

3,

4].

While several studies have utilized PSCAD for microgrid analysis, most rely on simplified or idealized converter representations that fail to account for the nonlinear interactions between manufacturer-specific control loops and real-world cable impedances. This paper addresses this gap by developing a high-fidelity model based on an actual 22.9 kV distribution-level microgrid, providing specific insights into the sub-millisecond transient window required for effective protection—a level of detail often missing in generic literature.

Unlike synchronous generators, which can supply relatively large and predictable fault currents determined mainly by machine reactance and network impedance, inverter-based DERs are equipped with fast-acting current-limiting and protection functions. As a result, their fault current contribution is usually limited to only a few multiples of rated current and is sustained for a very short duration. The exact magnitude, phase angle, and waveform shape depend strongly on the inverter control strategy (e.g., grid-following or grid-forming), implemented protection algorithms, and applicable interconnection requirements. Experimental and simulation studies have shown that PV inverters in particular exhibit diverse short-circuit responses across manufacturers and control modes, making it difficult to estimate available fault current for conventional protection design [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The main contributions of this paper are (i) the quantification of critical fault-detection timeframes in a converter-dominated system using manufacturer-based parameters; (ii) the demonstration of how actual network topology (e.g., specific TFR-CV cable data) influences DC-link discharge slopes, which is essential for setting robust protection thresholds like ICCR.

In microgrids with high penetration of BESS and PV units, this limited and converter-controlled fault current challenges the conventional philosophy of overcurrent-based protection schemes. Overcurrent relays, fuses, and reclosers are typically coordinated under the assumption of relatively high and well-defined fault levels and unidirectional power flow. When these assumptions no longer hold, protection devices may fail to detect faults, operate with excessive delay, or lose selectivity between primary and backup protections. The situation is further complicated by the fact that microgrids frequently transition between grid-connected and islanded modes, causing significant changes in fault levels and current directions that can disturb the coordination of existing relays [

2,

3,

4,

9,

10].

A BESS–PV microgrid is particularly attractive in practice because the BESS can provide energy shifting, peak shaving, and fast power support, while the PV plant supplies renewable energy and reduces net load. This combination can improve self-consumption of PV power and support multiple grid services. At the same time, however, the presence of both BESS and PV inverters introduces additional protection challenges: the fault current contribution from each unit is limited by its own current controller and protection logic, depends on operating conditions such as state of charge or irradiance, and can change as the system switches between charging, discharging, and standby modes. Yazdani and Dash analytically characterized the dynamics of a grid-connected PV system and showed how inverter control strategies strongly influence its transient and fault responses [

10]. Adegboyega et al. surveyed practical DC microgrid deployments and reported that protection and reliability issues become more severe as configurations and operating modes diversify [

11]. Kant and Gupta provided a comprehensive review of protection challenges and candidate schemes for DC microgrids, emphasizing the difficulty of coordinating conventional overcurrent relays under limited fault currents [

12]. Aboelezz et al. proposed an advanced centralized protection system for AC microgrids with a high penetration of inverter-based resources, illustrating how adaptive settings and wide-area information are often required to maintain selectivity [

13]. From an operational perspective, Zia et al. reviewed microgrid energy management systems and highlighted that frequent changes in dispatch, power flow direction, and operating mode lead to wide variations in short-circuit levels [

14]. Alahmed and AlMuhaini presented a laboratory-scale microgrid testbed with hybrid renewables, storage, and controllable loads, further demonstrating that different configurations and control modes significantly affect fault behavior and protection performance [

15]. As a consequence, the overall fault level and current distribution in a BESS–PV microgrid can vary widely across operating scenarios, and conventional settings that are adequate in one mode may lead to under-reach, miscoordination, or even non-operation in another.

To capture the complex interaction between inverter fault behavior and protection devices in such systems, the choice of simulation tool and model detail is critical. Phasor-domain (RMS) tools are widely used for power-flow and traditional short-circuit studies, but inverters are typically represented as idealized controlled sources with simplified dynamics. Such models are adequate for steady-state analyses but are often insufficient to reproduce fast switching phenomena, current limiting, and control interactions that determine inverter fault current waveforms and relay response. Electromagnetic transient (EMT) tools such as PSCAD/EMTDC, by contrast, allow detailed time-domain modeling of switching devices, control systems, and protection logic with microsecond-level time steps, enabling realistic representation of the dynamic behavior of BESS and PV inverters during faults and their impact on measurements, relays, and breakers [

5,

7,

8,

9].

Against this background, there is a clear need for case studies that use EMT-level models of real BESS–PV microgrids to examine short-circuit behavior and protection performance under practically relevant conditions [

16,

17,

18]. Such studies can help bridge the gap between theoretical protection concepts and field implementation by directly linking simulation results to actual system configurations, equipment ratings, and relay or protection settings.

This paper addresses this need by building and validating a detailed PSCAD EMT model of an actual BESS–PV microgrid connected to a 22.9 kV distribution feeder. The microgrid integrates a 1 MWh BESS with a 500 kW PCS and a 500 kW PV plant; the model incorporates the utility source, transformers, cables, aggregated loads, and manufacturer-based control models for the BESS and PV converters. The PSCAD model is first verified under grid-connected steady-state conditions by checking that PV and BESS power, bus voltages, and the PCC voltage correspond to the expected operating range of the real system.

Based on this validated model, two representative fault scenarios are investigated: (i) pole-to-pole short-circuit faults on the DC links of the PV and ESS converters, and (ii) a three-phase short-circuit fault at the low-voltage bus on the AC side. The fault current waveforms and peak values are analyzed to clarify the respective roles of the DC-link capacitors, converter current-limiting controls, and grid source. As a first application of the model to protection design, an instantaneous current change rate (ICCR)-based DC protection algorithm is implemented and its performance is evaluated under the simulated DC pole-to-pole fault.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

Development of a high-fidelity PSCAD EMT model of a real BESS–PV microgrid, using its actual topology, equipment ratings, line/cable data, and converter control parameters, and verification of the model through steady-state simulations.

Characterization of DC and AC short-circuit behavior in the actual microgrid, including DC pole-to-pole faults at the PV and ESS DC links and a three-phase short-circuit fault at the low-voltage bus, with explicit decomposition of grid, BESS, and PV current contributions.

Demonstration of an ICCR-based DC protection scheme as an example application of the model, showing sub-millisecond detection of DC pole-to-pole faults in the presence of converter current limiting.

Provision of a validated PSCAD model and data set that can serve as a platform for future research on new DC/AC protection techniques and protection coordination strategies for inverter-dominated microgrids.

2. Real BESS–PV Microgrid

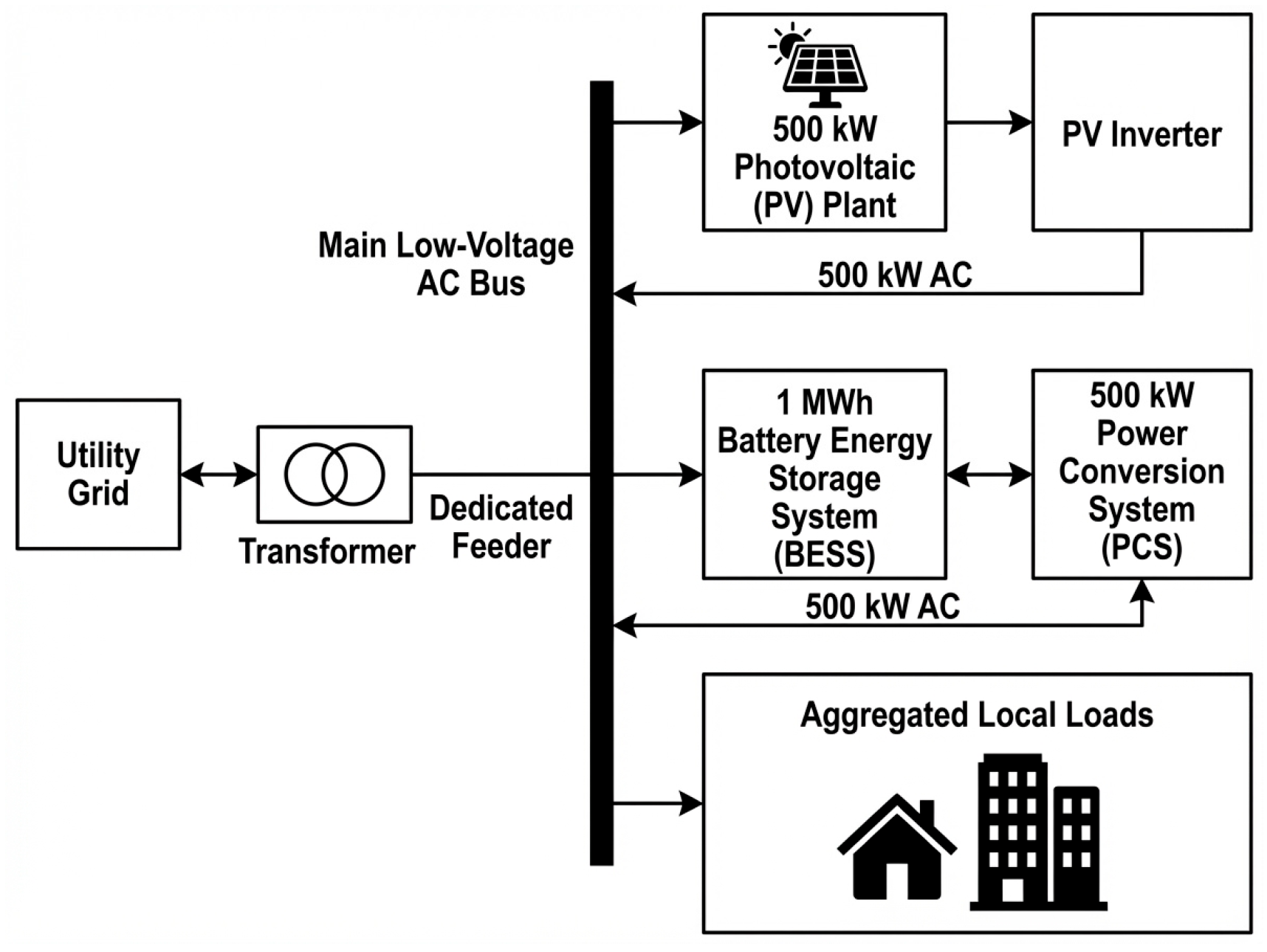

2.1. Microgrid System Overview

The microgrid considered in this thesis is a distribution-level BESS–PV system interconnected with the utility grid through a dedicated feeder and transformer. It has been designed to supply local loads while increasing the utilization of on-site renewable generation and providing operational flexibility through battery energy storage. The main components of the microgrid are a 1 MWh battery energy storage system (BESS) with a 500 kW power conversion system (PCS), a 500 kW grid-connected photovoltaic (PV) plant, low-voltage and medium-voltage transformers, radial feeders, and a set of aggregated loads located on the main low-voltage bus.

Under normal operating conditions, the microgrid is connected to the upstream distribution network at the point of common coupling (PCC). Power can flow bidirectionally through the PCC depending on the balance between local generation, storage operation, and load demand. When local generation and BESS discharge exceed the load demand, surplus power is exported to the grid; conversely, when generation is insufficient, the microgrid imports power from the utility.

Figure 1 shows the configuration diagram of a microgrid system. The microgrid consists of a transformer that connects the PCC to the main LV bus. The BESS PCS and PV inverters are connected in parallel to this LV bus through dedicated switchgear and protection devices. Downstream radial feeders supply building loads or process loads, each equipped with breakers, overcurrent protection, and metering.

Unlike studies that use generic library components, the model shown in

Figure 1 is built upon specific field data. This includes the precise impedance characteristics of the TFR-CV 185 mm

2 and 240 mm

2 cables and the transformer’s electrical parameters derived from the 22.9 kV real-world distribution feeder. Furthermore, the model incorporates manufacturer-based converter control parameters for the 500 kW PCS and PV inverters. This ensures that the simulation captures the fast transient behaviors (e.g., DC-link capacitor discharge) that are critical for validating the ICCR protection scheme.

2.2. BESS System Design

The BESS is designed to provide both energy and power support to the microgrid. The installed energy capacity is 1 MWh, which enables the system to perform peak shaving, load shifting, and short-duration backup operation. The nominal power rating of the associated PCS is 500 kW, allowing the BESS to charge and discharge at a maximum rate corresponding to a C-rate of approximately 0.5 C. The battery is implemented as a modular system composed of multiple racks and strings, each including a number of series-connected cells. A battery management system (BMS) monitors cell voltages, temperatures, and state of charge (SOC), and ensures safe operation within specified limits.

On the AC side, the BESS is interfaced with the LV bus through the 500 kW PCS, which is a three-phase, grid-connected voltage source converter (VSC). The PCS operates under different control modes depending on system requirements and grid conditions. Under normal grid-connected operation, it typically runs in PQ control mode, injecting a setpoint of active and reactive power to support local load and power factor requirements. During islanded operation, the PCS can switch to a voltage–frequency (V/f) or grid-forming mode, providing voltage and frequency references for the microgrid while sharing active and reactive power with the PV plant according to predefined droop characteristics.

2.3. PV System Design

The PV plant has a nominal capacity of 500 kW and is connected to the same LV bus as the BESS PCS. The array is composed of multiple strings of series-connected PV modules, which are combined through string combiner boxes and connected to one or more central or string inverters. The DC-side design (module type, number of modules per string, and number of parallel strings) is chosen to ensure that the array voltage and current remain within the allowable operating range of the inverters under expected irradiance and temperature conditions.

Each PV inverter operates as a grid-following converter under normal conditions, synchronizing with the voltage at the LV bus and injecting active power according to the available irradiance and maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithm. Reactive power can be controlled to support local voltage regulation, either at a fixed power factor or according to a Q(V) characteristic, depending on grid code and utility requirements. In islanded operation, the PV inverters typically continue to operate in a grid-following mode, using the voltage and frequency references established by the BESS PCS or another grid-forming unit.

The PV system is protected by DC-side fuses or breakers at the string or array level to clear faults such as string-to-string or ground faults, and by AC-side breakers with overcurrent and, if required, residual current or ground-fault protection. Surge protective devices are installed on both the DC and AC sides to limit the impact of lightning and switching surges. Measurement devices provide real-time data on array voltage, current, power, and inverter status.

3. PSCAD Modeling of Microgrid

The PSCAD model of the microgrid aims to capture the essential electrical and control characteristics of the BESS, PV plant, PCS, transformers, lines, loads, and the utility grid. The model is developed at an electromagnetic transient (EMT) level with a sufficiently small time step to accurately represent switching events, converter dynamics, and the fast transients associated with short-circuit faults.

3.1. BESS System

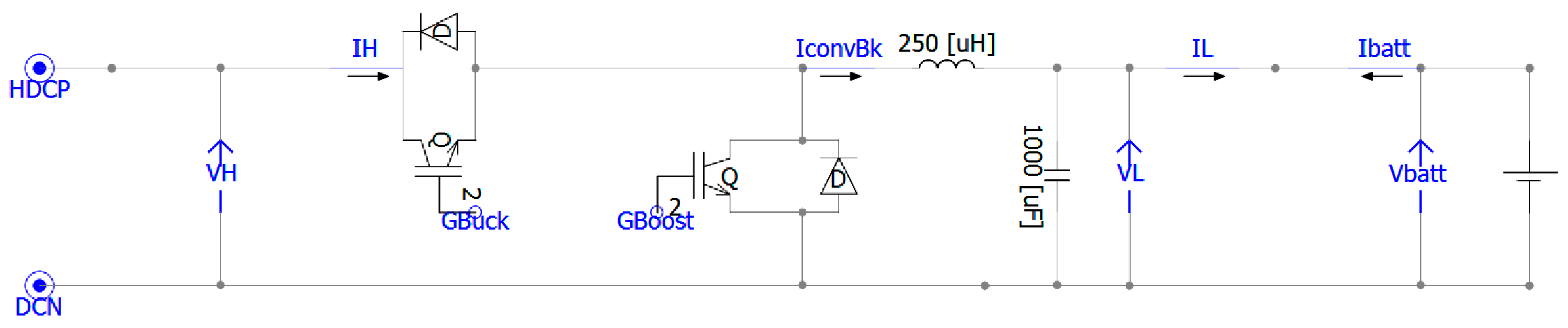

Figure 2 shows the PSCAD model of the battery energy storage system (BESS) used in this study. As shown in

Figure 2, the BESS is connected between the high-voltage DC bus (HDCP/DCN) and the battery terminals through a bidirectional DC/DC converter composed of the GBuck and GBoost switches and an interface inductor

L. The converter operates in buck mode during charging (energy transfer from the DC bus to the battery) and in boost mode during discharging (energy transfer from the battery to the DC bus), while the inductor

L smooths the inductor current and limits its ripple.

The currents

,

,

, and

, and the node voltages

and

are monitored to analyze the dynamic behavior of the BESS under normal operation and DC fault conditions. The battery element on the far right of

Figure 2 is modeled using the Shepherd model, in which the open-circuit voltage is expressed as a nonlinear function of the state of charge (SOC), combined with internal resistance and polarization terms. This allows the PSCAD model to reproduce realistic charge–discharge characteristics and terminal voltage response of the 1 MWh battery during the simulations.

The control parameters for the 500 kW PCS, including current limiting strategies and internal response constants, were strictly modeled based on the manufacturer’s technical specifications. This ensures that the simulated converter dynamics accurately represent the physical hardware’s self-protection characteristics during transient events.

3.2. PV System

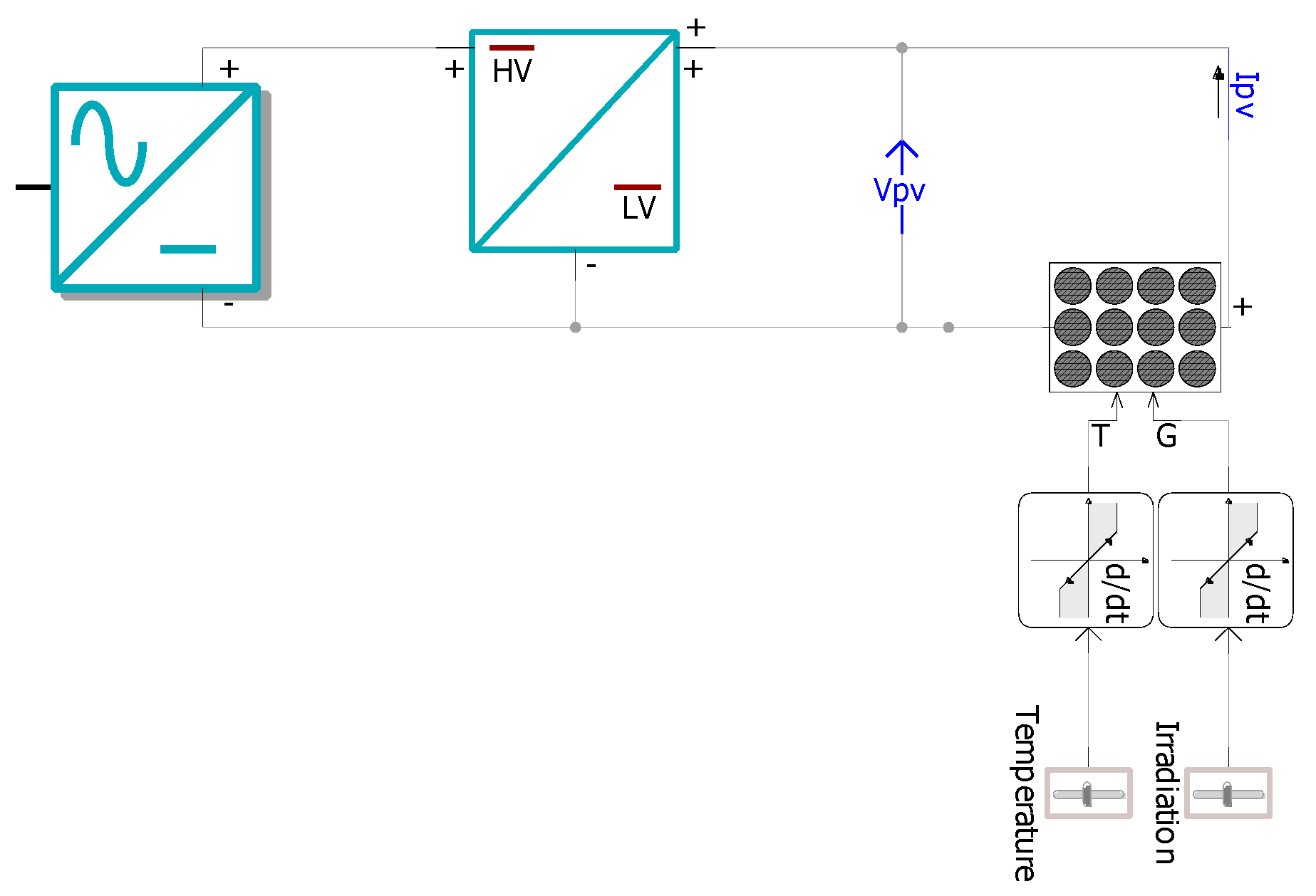

Figure 3 shows the PSCAD model of the PV system used in this study. As shown in

Figure 3, the PV array is represented by a nonlinear DC source whose current–voltage characteristic depends on solar irradiance

and cell temperature

. These two variables are provided as external inputs through time-varying blocks, so that different irradiation and temperature profiles can be applied in the simulations. The array terminal voltage

and current

are measured at the output of the PV block and are used both for monitoring and for control purposes.

On the DC side, the PV array is connected to a DC/DC converter that performs maximum power point tracking (MPPT). The MPPT controller continuously adjusts the duty ratio of the DC/DC converter so that the operating point of the PV array follows the maximum power point corresponding to the instantaneous values of and . In this way, the PV system can extract the maximum available power from the array under varying environmental conditions while maintaining the desired DC-link voltage.

The regulated DC power is then transferred to the common DC link of a grid-connected AC/DC converter. This converter is modeled as a voltage-source converter interfaced with the main low-voltage AC bus (380

) of the microgrid. Through appropriate current control in the synchronous

–

frame and a phase-locked loop for synchronization, the AC/DC converter injects active power generated by the PV array into the 380 V bus and, if required, provides reactive power support. Thus, as indicated in

Figure 3, the combination of the MPPT-controlled DC/DC stage and the grid-connected AC/DC converter enables the PV system to operate as a controllable source within the BESS–PV microgrid.

To accurately capture high-frequency transients during DC fault conditions, the PSCAD simulation was performed with a fixed time-step of 10 μs, while the ICCR algorithm was implemented with a sampling frequency of 10 kHz to match the actual Digital Signal Processor (DSP) performance of the site’s controllers, thereby confirming the practical feasibility of sub-millisecond fault detection in real-world hardware.

3.3. PCS and Network

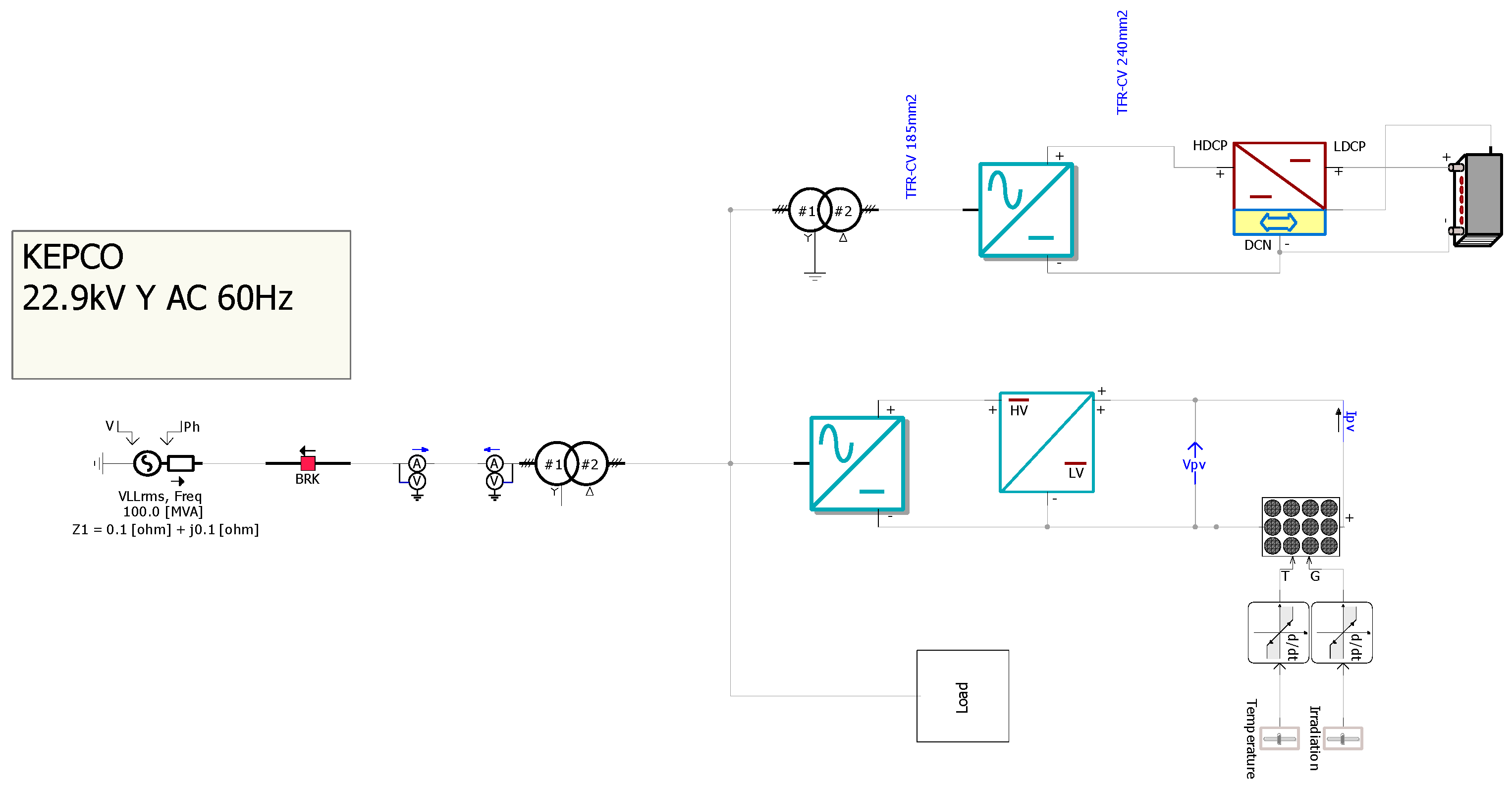

Figure 4 shows the complete PSCAD model of the BESS–PV microgrid as connected to the KEPCO distribution system. As shown in

Figure 4, the external grid is represented by a three-phase 22.9 kV, 60 Hz Y-connected source (“KEPCO 22.9 kV Y AC 60 Hz”). A circuit breaker (BRK) and a set of measuring current transformers (CTs #1 and #2) are installed on the medium-voltage feeder to emulate the actual protection and metering arrangement at the point of common coupling (PCC).

Downstream of the PCC, the medium-voltage feeder is connected to a distribution transformer that steps the 22.9 kV line-to-line voltage down to the low-voltage level. The transformer and the outgoing low-voltage cables (TFR-CV 185 mm2 and 240 mm2 in the PSCAD model) feed the main low-voltage bus of the microgrid. This LV bus is the common connection point for the BESS PCS, the PV inverter, and the aggregated local load.

On the upper branch of

Figure 4, the BESS PCS is modeled as a three-phase grid-connected voltage-source converter interfacing the common DC link of the BESS (described in

Section 3.1) with the LV bus. The PCS injects or absorbs up to 500 kW of active power depending on the charge/discharge command and can provide reactive power support as required. Its inner current control, outer power/voltage control, and protection functions (current limiting, over/under-voltage, and trip logic) are implemented in PSCAD so that the converter responds realistically to both normal operating conditions and fault events.

On the lower branch, the PV system described in

Section 3.2 is connected to the LV bus through its own AC/DC converter and, where applicable, a dedicated LV transformer. The PV inverter delivers up to 500 kW of active power to the LV bus while operating at the maximum power point determined by the DC/DC MPPT stage. Both the BESS PCS and the PV inverter therefore share the same LV node with the local load, so that their combined output can either supply the load or be exported/imported through the PCC depending on the instantaneous power balance.

The aggregated local load is modeled as a three-phase load block connected to the LV bus, with active and reactive power levels chosen to represent the typical demand of the actual facility.

4. Simulation Result

This chapter presents the main simulation results obtained from the PSCAD model of the microgrid. The results are organized into steady-state operation and short-circuit fault studies on both the DC and AC sides. The objective is to validate the model under normal conditions, characterize the fault current contributions of the BESS and PV units, and examine their impact on protection performance.

4.1. Steady State

The effectiveness of the developed microgrid model was first evaluated under normal steady-state operating conditions.

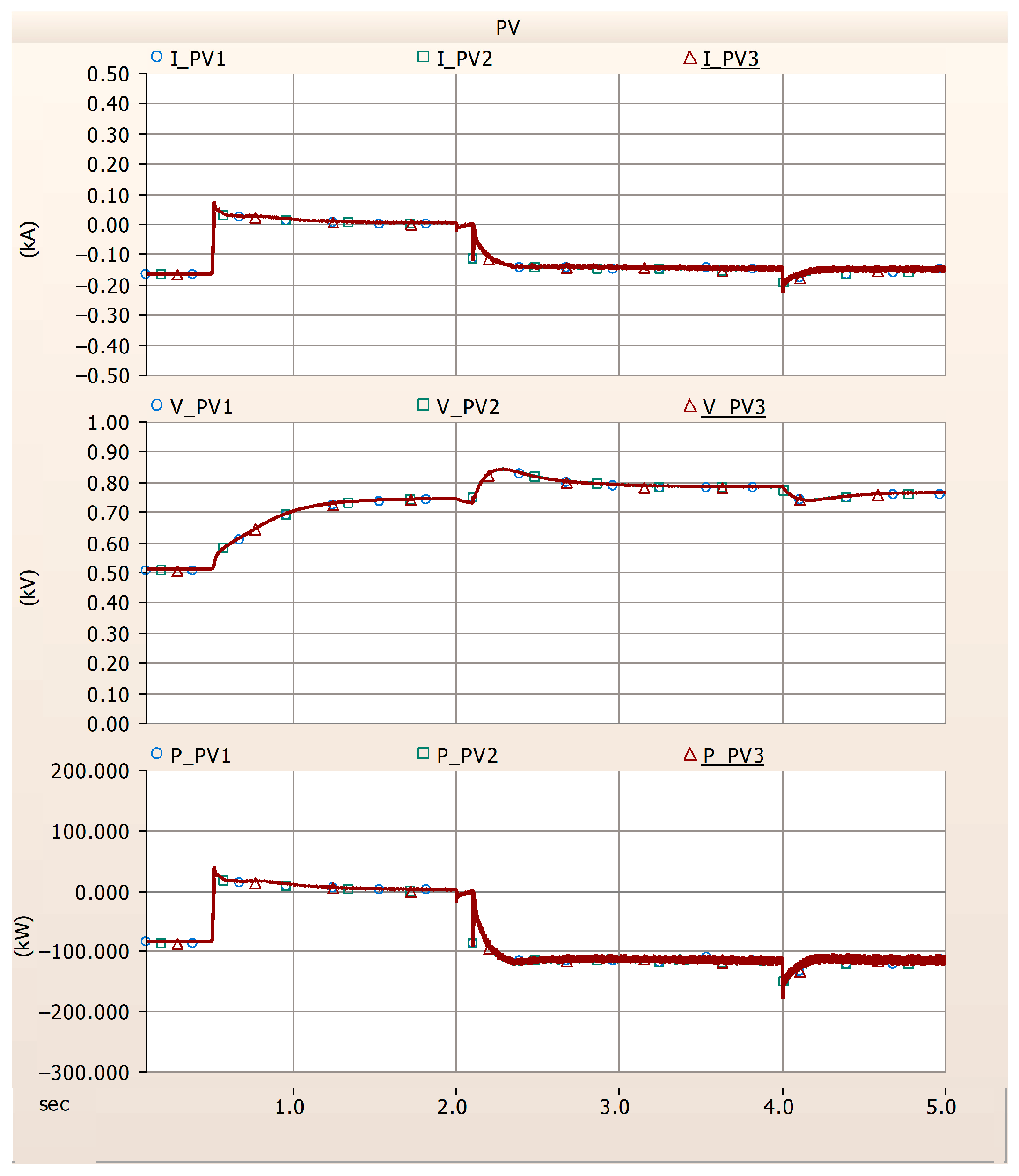

Figure 5 shows the current, terminal voltage, and active power of the three PV units (PV1–PV3) obtained from the PSCAD simulations. In the considered scenario, the rectifier is connected to the system at 0.5 s, establishing the DC link. At 2.0 s all three PV units start operating and track their maximum power point, after which each unit delivers approximately 120 kW of active power. At 4.0 s, the operating mode of the ESS is changed so that charging/discharging of the battery is initiated, which causes a small but noticeable change in the PV output current and power while the terminal voltages remain within the expected range.

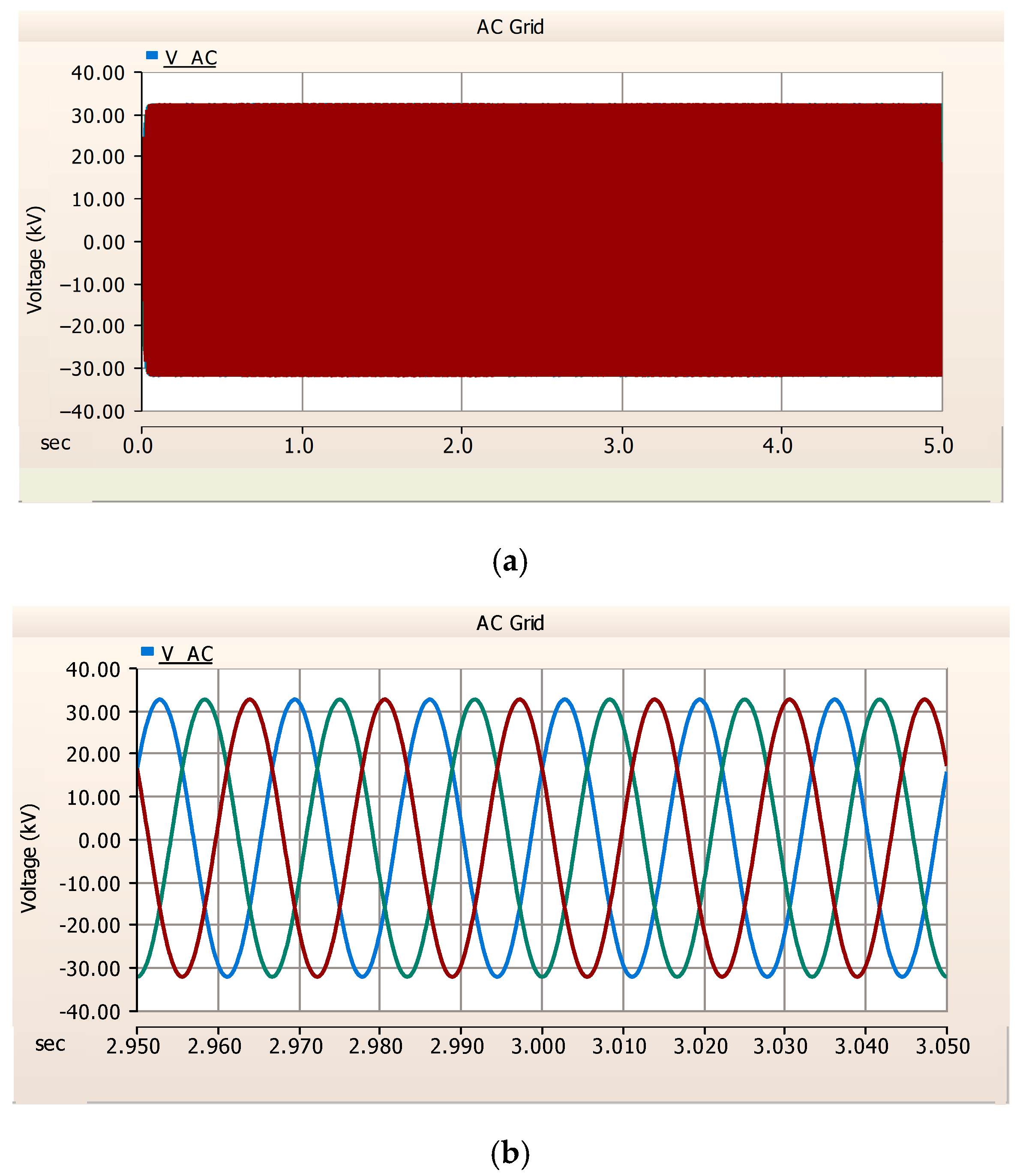

Figure 6 presents the AC grid voltage waveform under the same normal operating condition. The simulated maximum (peak) voltage is 32.384 kV, corresponding to an RMS value of 22.899 kV, which is essentially equal to the nominal 22.9 kV of the KEPCO distribution system. This confirms that the model correctly reproduces the steady-state grid voltage at the point of common coupling.

Overall, the steady-state waveforms exhibit stable behavior with smooth transients following each switching event. Bus voltages remain close to their nominal values, and the total active power from the PV units and the ESS matches the prescribed load demand and grid exchange within a small tolerance. These results indicate that the control systems of the PV inverters and the ESS PCS are functioning as intended and that the network model accurately represents power flow in the microgrid. Consequently, the steady-state simulations verify the validity and accuracy of the proposed PSCAD microgrid model, providing a reliable basis for the subsequent fault and protection analyses.

To verify the phase-to-phase relationship within the developed EMT model, the steady-state voltage at the PCC is analyzed as shown in

Figure 6b. The different colored lines denote the individual phases: red for Phase A, green for Phase B, and blue for Phase C. The consistent peak magnitudes and uniform frequency across all three phases demonstrate the reliability of the inverter control parameters and the overall system stability in the simulation environment.

In addition to steady-state validation, the transient behavior of the converter models was verified by comparing the simulated step responses with the control dynamic characteristics specified in the manufacturer’s design documents. Although field-measured fault data are unavailable due to safety constraints of the operational site, the high fidelity of the model under fault conditions is supported by the precise integration of actual transformer saturation curves and cable impedance parameters, which were benchmarked against standard IEEE test case behaviors for inverter-interfaced resources. Furthermore, the simulated fault initiation—characterized by a sub-millisecond current rise—was cross-checked against theoretical RC discharge models of the DC-link, confirming that the developed EMT model reliably captures the high-frequency transient dynamics essential for fast protection studies.

4.2. Pole to Pole Short-Circuit Fault (DC Side)

To investigate the DC fault behavior of the converter-interfaced sources, a solid pole-to-pole short-circuit fault was applied to the DC links of the PV system and the ESS. In both cases the fault inception time was set to 3.0 s, while the systems were operating under steady-state conditions prior to the fault.

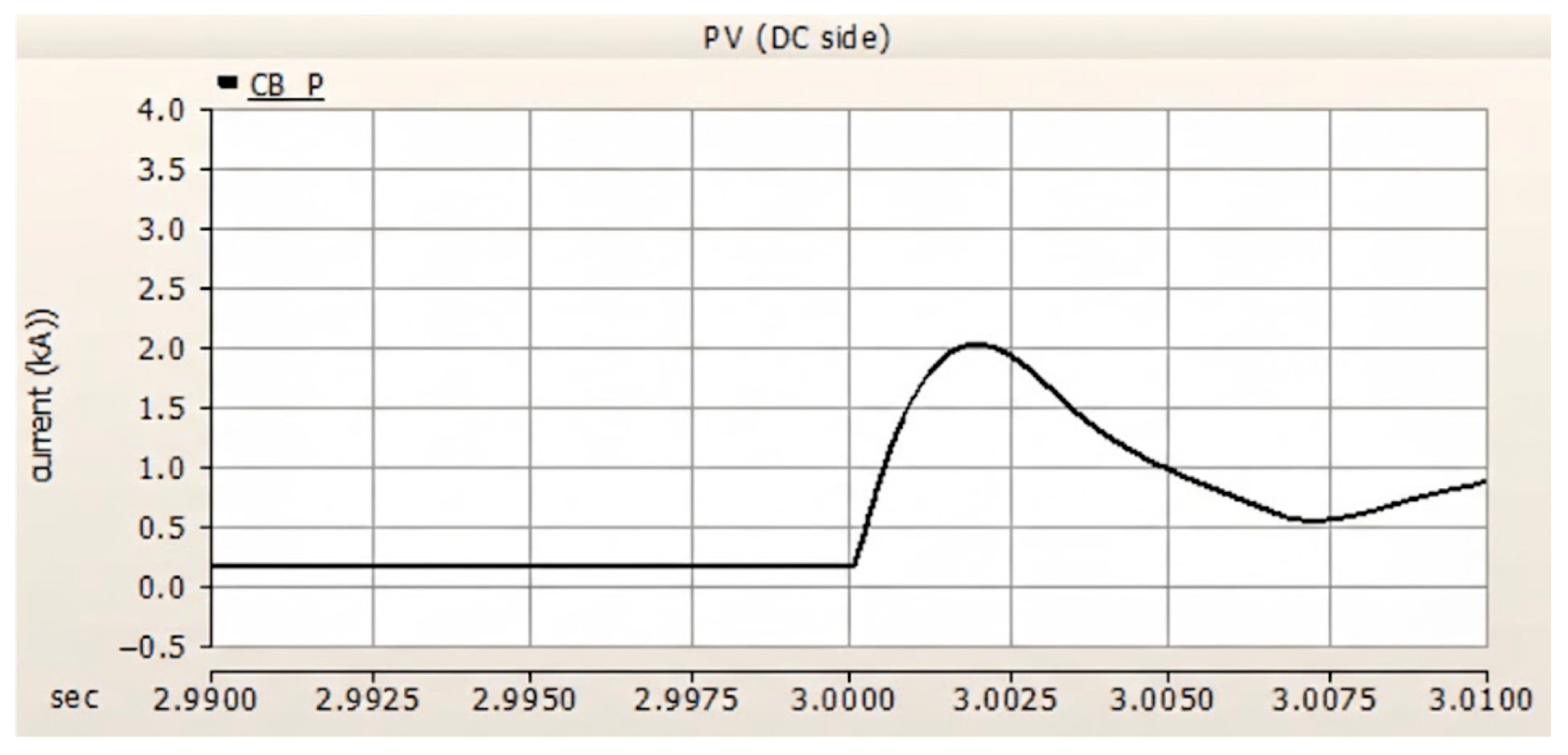

Figure 7 shows the PV DC-side current during the pole-to-pole short-circuit fault. Before

, the PV operates normally and the DC current remains at its pre-fault value. At the instant of the fault the current starts to rise rapidly, reaching a maximum of 2.005 kA at 3.002 s. The relatively large peak arises because the energy stored in the DC-link capacitor of the PV converter is suddenly discharged into the fault path. After this initial discharge, the current subsequently flows through the short-circuit path at a much reduced level.

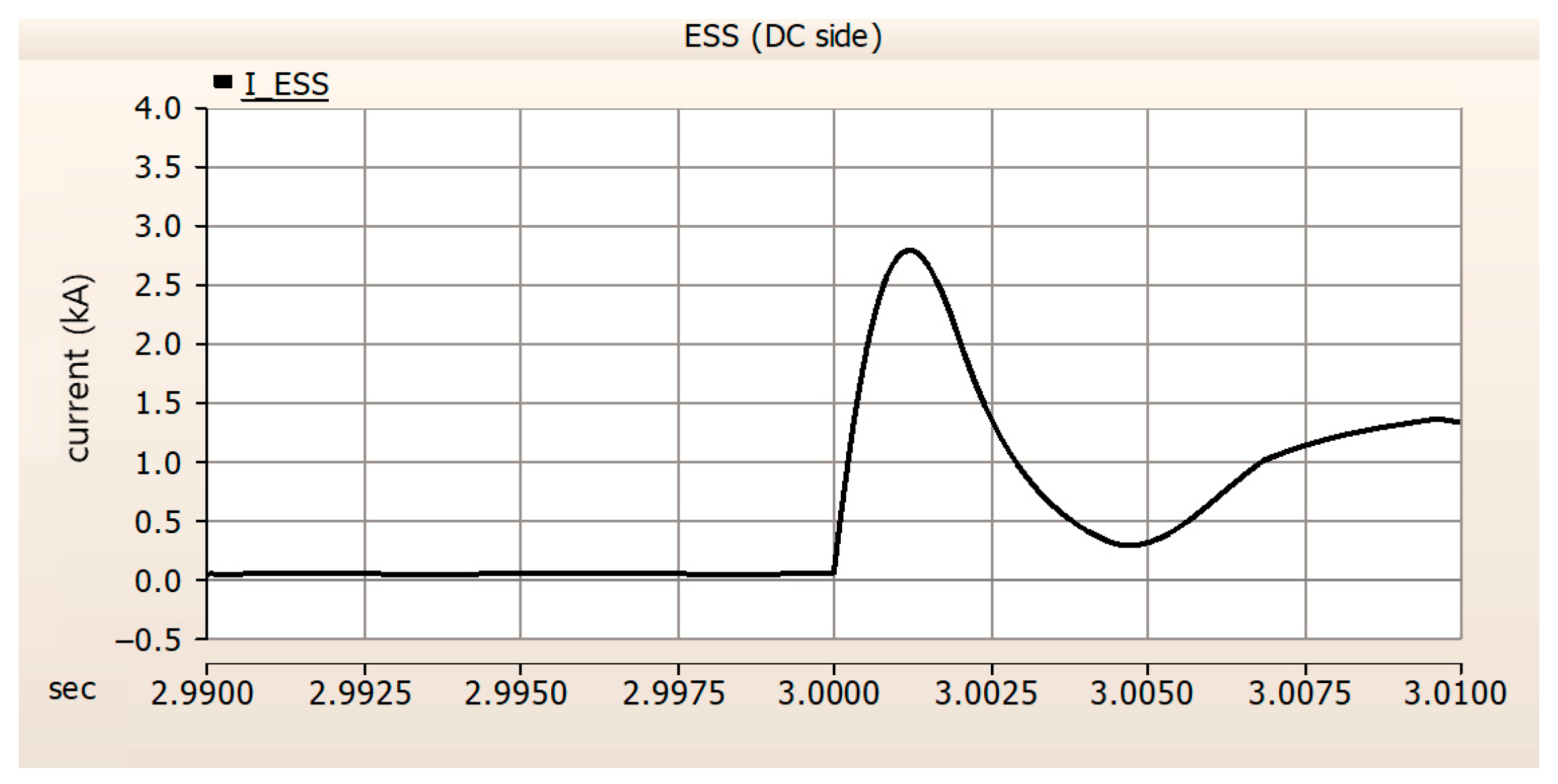

Figure 8 shows the ESS DC-side current when a pole-to-pole short-circuit fault is applied to the ESS DC link. As in the PV case, the current remains at its pre-fault level up to

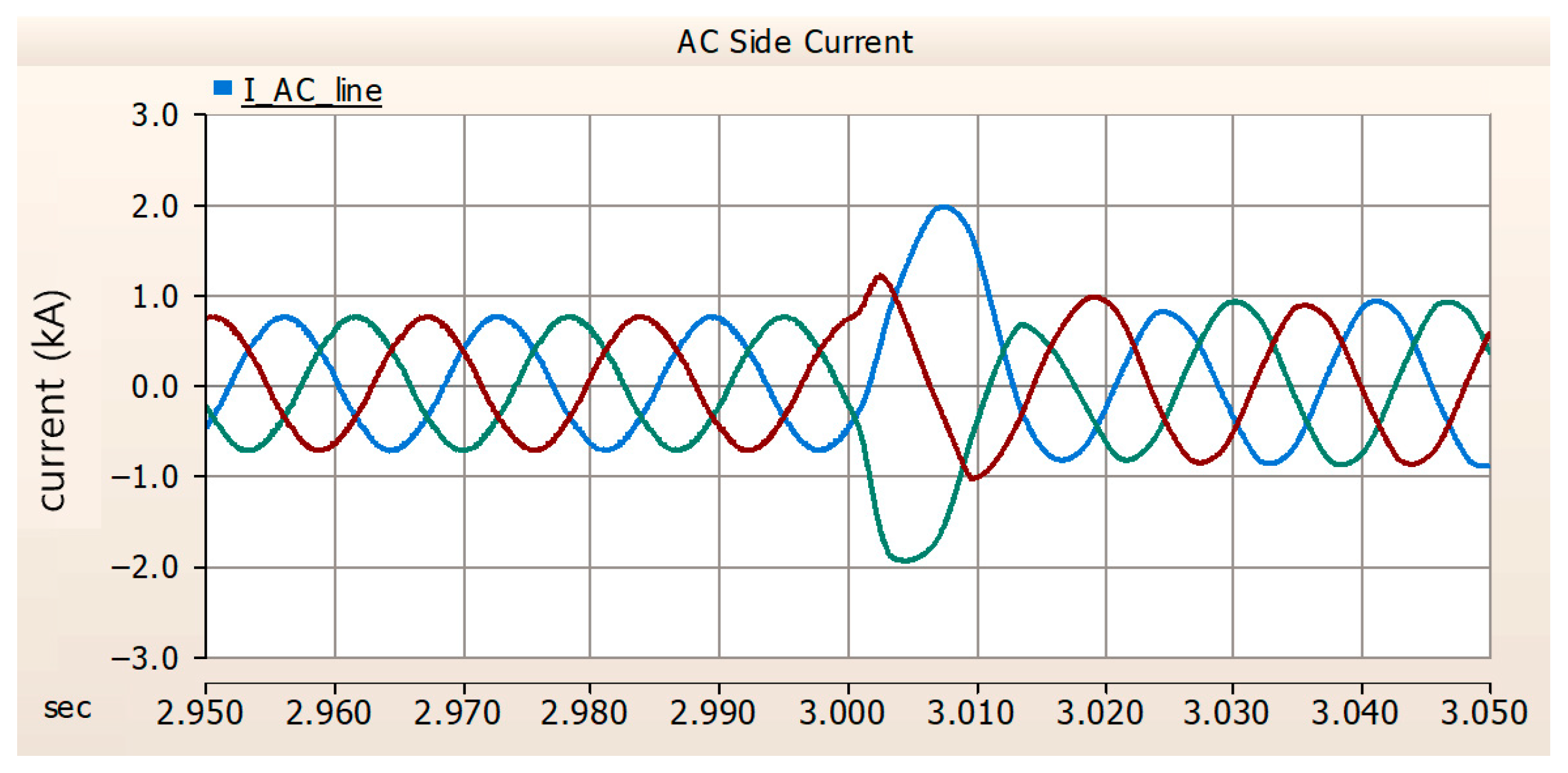

and then increases rapidly once the fault is introduced. The maximum current is 2.770 kA, occurring at 3.0012 s. This peak again results from the sudden release of the energy stored in the DC-link capacitor of the ESS rectifier.

Figure 9 shows the three-phase AC line currents at the converter terminals for the same DC pole-to-pole fault. The waveforms for Phase A, Phase B, and Phase C are represented by blue, green, and red lines, respectively. Prior to the fault, the A-phase, B-phase, and C-phase currents are balanced sinusoidal waveforms. Immediately after the fault at

, the phase currents exhibit transient peaks: the A-phase current increases to 1.956 kA, the B-phase current decreases to −1.958 kA, and the C-phase current increases to 1.406 kA. These transient values correspond to the interval during which the DC-link capacitor energy is being discharged through the converter toward the AC side. Once the converter current-limiting action is established, the AC currents return toward their pre-fault magnitude and waveform.

Taken together,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 demonstrate that DC pole-to-pole faults in converter-interfaced sources are characterized by a very short-duration high peak caused by DC-link capacitor discharge, followed by a quickly limited current determined by the converter control. This behavior underscores the need for fast and sensitive DC-side protection schemes tailored to these brief but distinctive current transients.

4.3. Three-Phase Short-Circuit Fault (AC Side)

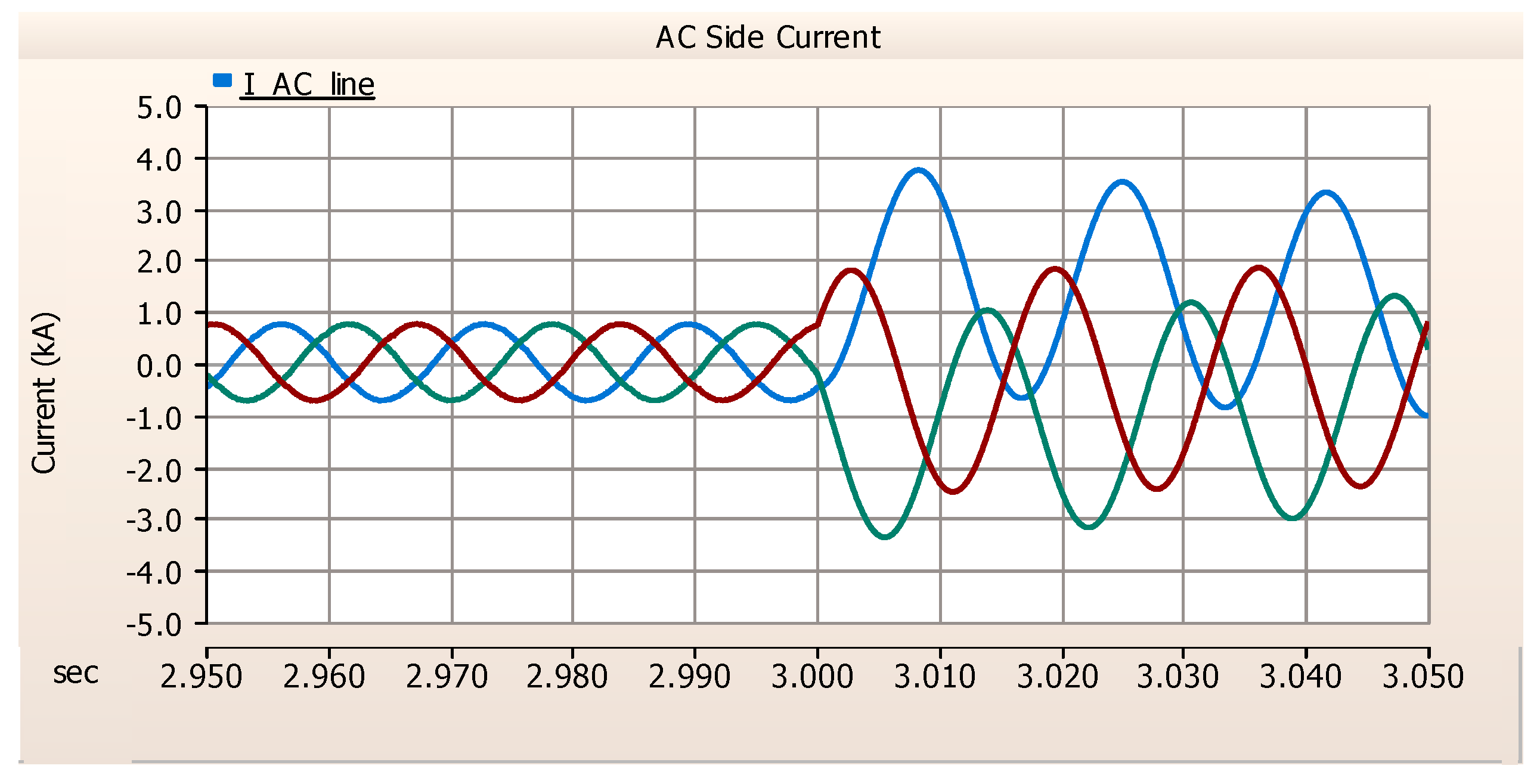

Figure 10 shows the three-phase AC-side line currents when a three-phase short-circuit fault is applied on the AC side of the microgrid. The blue, green, and red lines in the figure represent Phase A, Phase B, and Phase C, respectively. The fault inception time is set to 3.0 s, at which point the system is operating in steady state with balanced sinusoidal currents. Immediately after the fault, the phase currents increase sharply and exhibit transient asymmetry.

Specifically, the A-phase (blue) current rises to a peak value of 3.714 kA, while the B-phase (green) and C-phase (red) currents reach −3.384 kA and −2.506 kA, respectively. These results demonstrate the model’s ability to capture severe transient responses during AC-side faults.

After these peaks, the currents begin to decay as the fault is supplied primarily by the upstream grid source while the BESS and PV converters enter current-limiting operation. As a result, the sustained fault current level is limited compared with conventional synchronous-machine systems. This behavior indicates that, although the initial three-phase fault produces a significant increase in AC current, the magnitude and duration are constrained by the converter controls, which must be carefully considered when setting overcurrent and directional protection on the AC side.

5. Protection Scheme

This chapter describes the protection scheme adopted for the proposed BESS–PV microgrid. Conventional overcurrent protection is used on the AC side (PCC breaker, LV feeders, and converter terminals), while an instantaneous current change rate (ICCR) technique is employed as a dedicated DC-side protection for fast detection of pole-to-pole (PtoP) faults in the PV and ESS DC links. The ICCR method is particularly suitable for converter-interfaced sources, where the absolute fault-current magnitude is limited by the converter control but the rate of rise of DC current during a fault remains significantly higher than in normal operating conditions.

The ICCR technique exploits the fact that, under a DC PtoP fault, the DC-link current of a converter increases much more rapidly than during normal load changes. Instead of relying on the absolute magnitude of the DC current, the method evaluates the instantaneous rate of change of the DC current and compares it with a predefined threshold.

The ICCR value at the

n-th sampling instant is defined as

where

is the DC-link current at the current sampling instant,

is the DC-link current at the previous sampling instant, and

is the sampling interval.

In normal operation, variations of between consecutive samples are small, so remains close to zero. When a PtoP fault occurs, the energy stored in the DC-link capacitor is rapidly discharged, causing a steep rise of DC current. As a result, temporarily exceeds a predetermined threshold, which is used as the detection criterion for DC faults. In this study, the ICCR threshold is selected as , taking into account the initial transient characteristics of the DC-link current under normal operating conditions and small disturbances. When , a fault counter is started. To avoid mis-operation due to measurement noise or small transient spikes, the counter must reach a preset value N before a trip signal is issued. Here, N is set to 2, which corresponds to an effective detection window of approximately 0.13 ms at the adopted sampling rate.

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed ICCR algorithm, the threshold of 100 A/ms was validated under various non-fault scenarios, including maximum load switching transients and measurement noise levels of up to 5%. The results confirmed that the algorithm remains immune to such non-fault disturbances, preventing nuisance tripping. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the ICCR method was tested across different fault impedances (0.1 Ω to 10 Ω) and various operating points of the BESS and PV systems, ensuring reliable detection even under high-impedance fault conditions where the peak current is limited.

If the condition is not satisfied in consecutive samples, the counter is reset to zero. This simple logic allows the ICCR scheme to distinguish genuine PtoP faults—which produce a sustained high rate of current rise over several samples—from benign transients.

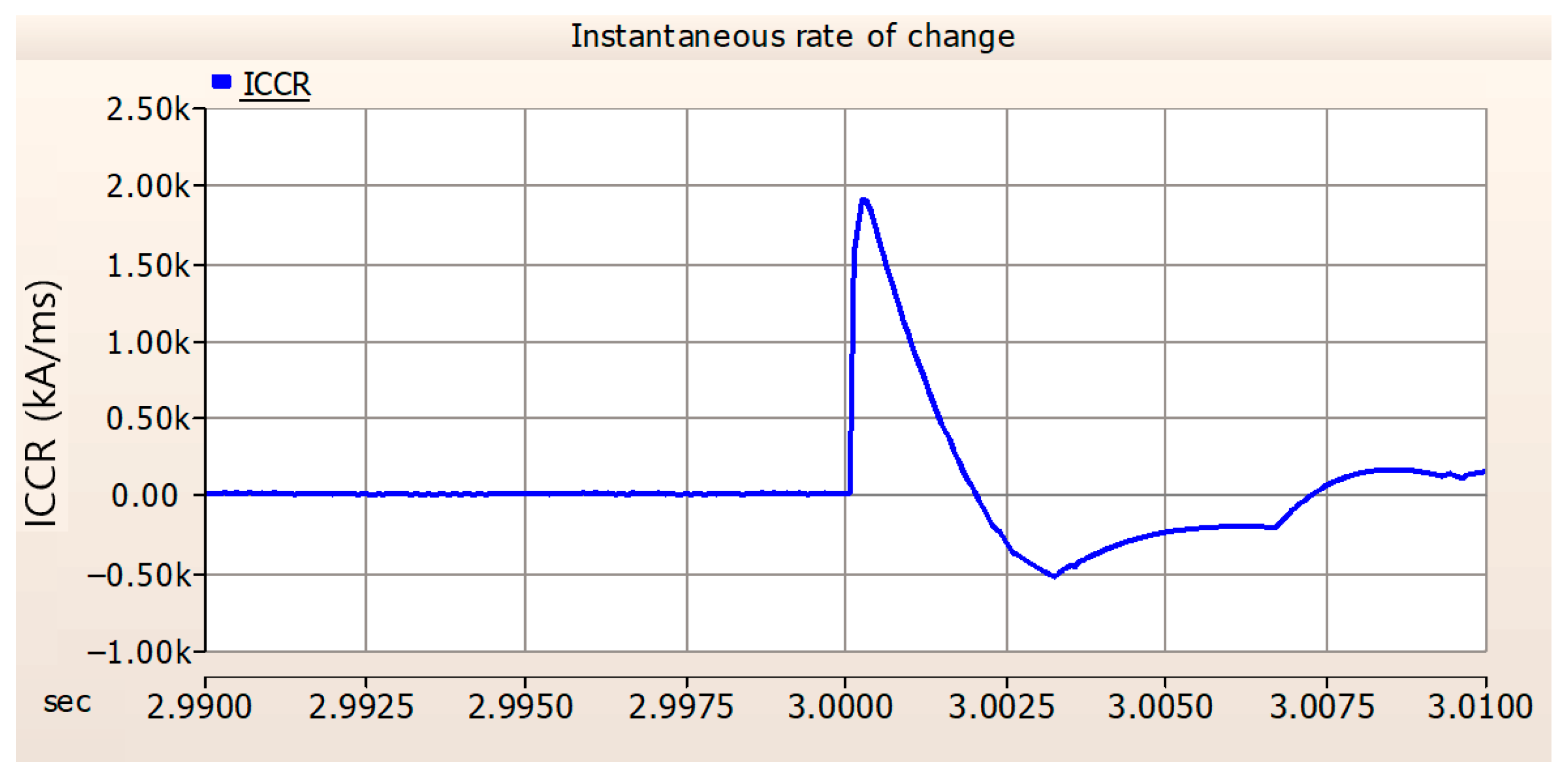

When a pole-to-pole short-circuit fault is applied on the DC side at

, the behavior of the ICCR index is shown in

Figure 11. Before the fault, the ICCR value remains close to zero, indicating only small variations in the DC current under normal operation. Immediately after fault inception, the ICCR rises sharply and reaches a maximum value of 1899.319 A/ms, which is far higher than the protection threshold of 100 A/ms. This large positive spike corresponds to the rapid increase of DC current caused by the discharge of the DC-link capacitor into the short-circuit path.

To ensure the robustness of the 100 A/ms ICCR threshold, a sensitivity analysis was performed considering measurement noise and normal switching transients. Even with the introduction of 5% Gaussian white noise into the current measurement, the maximum rate of change during steady-state and load-switching scenarios remained below 35 A/ms. This provides a safety margin of more than 180% relative to the 100 A/ms setting, confirming that the proposed threshold is sufficient to prevent nuisance tripping while maintaining high sensitivity for actual fault detection.

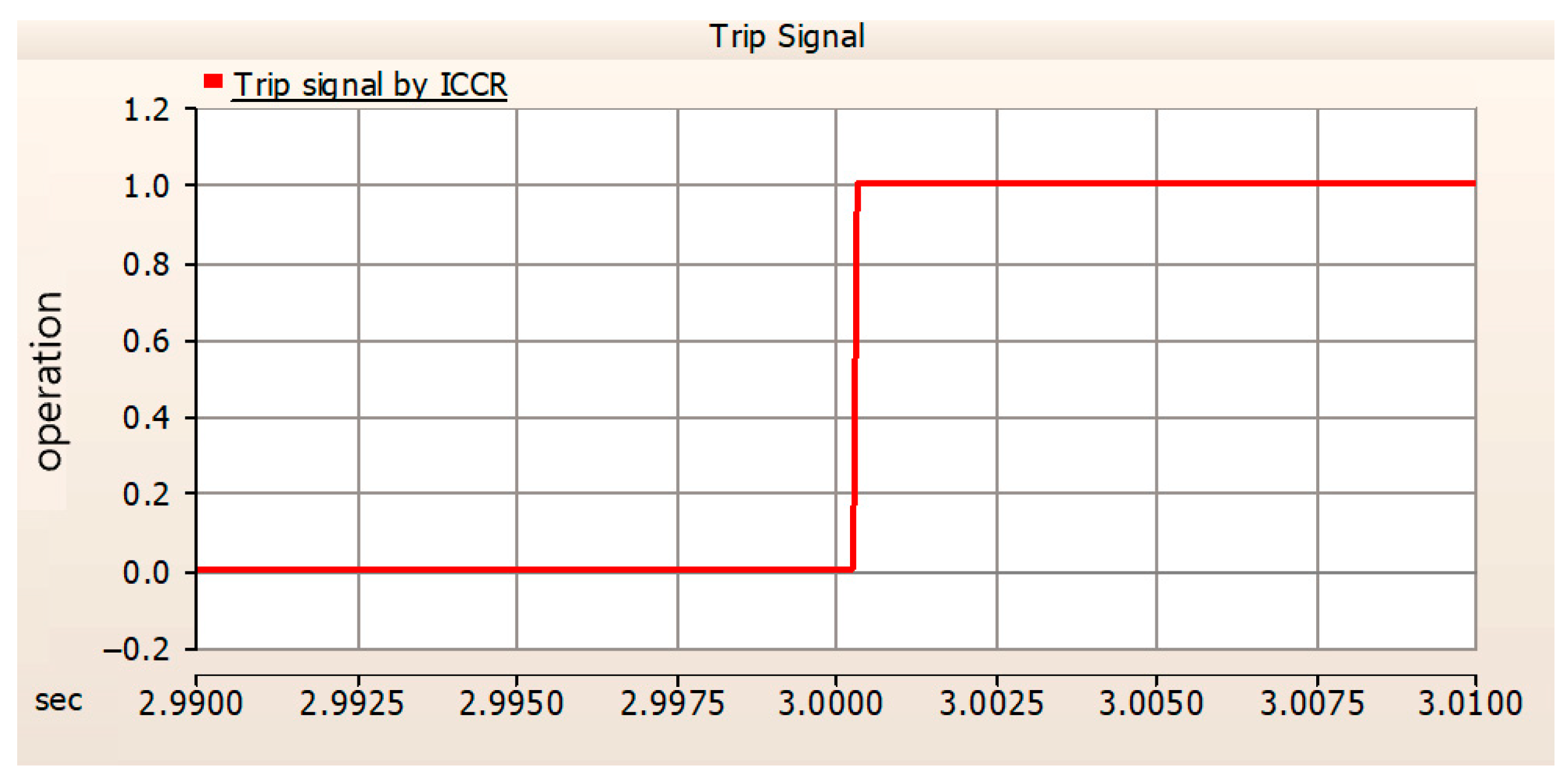

The corresponding trip signal generated by the ICCR protection is presented in

Figure 12. As soon as the ICCR exceeds the threshold for the required number of consecutive samples, the counter condition is satisfied and the trip signal changes from 0 to 1. In this case, the ICCR threshold is reached and a trip command is issued 0.342 ms after the fault occurs, demonstrating that the proposed ICCR-based protection can detect DC pole-to-pole faults within a sub-millisecond time frame.

To further evaluate the robustness of the ICCR algorithm, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the fault impedance (Rf) and introducing measurement noise.

Table 1 summarizes the performance of the ICCR algorithm under these conditions. Even as the fault impedance increases to 10 Ω, which significantly reduces the peak fault current, the initial di/dt remains well above the 100 A/ms threshold. Additionally, the algorithm successfully distinguished faults from load switching transients, where the di/dt was observed to be less than 45 A/ms.

The results in

Table 1 indicate that the ICCR algorithm is highly effective for inverter-dominated microgrids because it relies on the physical discharge characteristics of DC-link capacitors rather than steady-state fault current magnitudes. While high-impedance faults (10 Ω) reduce the absolute current level, the rapid change in current (di/dt) during the first few milliseconds remains a distinct signature of a fault. This robustness against parameter uncertainty and noise (tested up to 5% variance) confirms that the proposed method is not only theoretically sound but also practically applicable to diverse microgrid configurations beyond this specific case study.

The fault behaviors observed in this study, particularly the sub-millisecond current peak, are primarily governed by the energy stored in the DC-link capacitors of the PCS and PV inverters. Analytically, the peak fault current and its rate of rise (di/dt) are proportional to the ratio of /, where is the total loop inductance. To highlight the performance gains of the proposed method, a comparative analysis was conducted between the ICCR algorithm and a conventional instantaneous overcurrent (OC) relay. While conventional OC relays are often delayed because the fault current magnitude is rapidly capped by the converter’s current-limiting control, the ICCR algorithm identifies the fault within 0.342 ms by detecting the initial discharge slope before the control action takes effect. This confirms that the ICCR scheme provides superior speed and selectivity in inverter-dominated microgrids compared to magnitude-based protection methods.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented a PSCAD-based analysis of short-circuit faults and protection characteristics in a real BESS–PV microgrid integrating a 1 MWh BESS with a 500 kW PCS and a 500 kW PV plant on a 22.9 kV feeder. The main contribution is the development and steady-state validation of a detailed EMT model that reflects the actual single-line diagram, equipment ratings, cable data, and converter control structures of the operating microgrid. Using this model, DC pole-to-pole faults at the PV and ESS DC links and a three-phase short-circuit fault at the low-voltage bus were simulated. The results showed that DC faults are dominated by short-duration peaks caused by DC-link capacitor discharge and are strongly limited by converter control, while AC three-phase faults are mainly supplied by the upstream grid with only limited contribution from the converters.

As an initial application of the model to protection design, an instantaneous current change rate (ICCR) algorithm was implemented as a DC-side protection function. For a DC pole-to-pole fault, the ICCR index exceeded the 100 A/ms threshold and issued a trip command within 0.342 ms, demonstrating the feasibility of very fast DC fault detection in converter-dominated systems. It should be noted that these findings are primarily characterized within the specific electrical parameters of the 22.9 kV distribution-level microgrid, where the fault transients are heavily influenced by the integrated DC-link capacitance and specific loop inductances of the site. The validated PSCAD model and associated data set thus provide a practical platform for future work on new DC/AC protection algorithms and protection coordination strategies tailored to real BESS–PV microgrids.

In conclusion, while the results are specifically tied to the analyzed 22.9 kV BESS–PV microgrid configuration, they offer critical insights into the necessity of sub-millisecond protection in inverter-dominated systems.

To further validate the broader applicability of the proposed protection scheme, future research will investigate the algorithm’s performance across diverse microgrid topologies and varying scales of inverter-based resources. Additionally, we plan to conduct hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) simulations and experimental tests to evaluate the robustness of the ICCR method against complex measurement noise and communication latencies in real-world deployments.