1. Introduction

The energy sector has been undergoing very dynamic changes in recent years. These changes are driven by several factors. Firstly, dynamic economic development in many regions of the world, particularly in Asia, has induced a rapid increase in energy demand. Secondly, many countries are striving to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which leads to a reduction in the role of fossil fuels and a simultaneous increase in the emission-free source potential. Another important factor is the desire for energy security, which in the case of regions such as Europe, which has high energy demand but very limited fossil fuel resources. According to the IEA, global energy investments will reach USD 3296 billion in 2025, which is an increase of over 20% compared to 2015. The structure of investment is also changing. In 2015, the petrochemical industry saw the largest investment, while currently, the largest investments are being observed in renewable energy sources. The energy systems of countries that have achieved a high share of weather-dependent renewable sources typically face serious issues with energy supply stability. In most of these systems, fossil fuel sources provide electricity when weather conditions result in low production of electricity from wind turbines or photovoltaic panels. However, as the EU and China aim to achieve climate neutrality within the next few decades, energy storage will have to take on the role of stabilizing energy supplies. The amounts of energy that must be stored are enormous, thousands of times greater than the capacity of pumped-storage power plants. Therefore, it is expected that energy will be stored in the form of synthetic fuels such as hydrogen, ammonia, or methane. The purpose of this paper is to determine the size of energy storage facilities, the capacity of facilities for producing synthetic fuels, and installations for converting secondary fuels into electricity, which would be necessary to achieve a system based 100% on renewable sources. The Polish power system is used as an example.

The concept of an energy system based entirely on renewable sources is not new. In the paper [

1], the authors analyzed Germany and its possibility of converting it into a fully sustainable system, finding that this process is economically acceptable. In the paper [

2], a fully renewable building system was analyzed, and it was shown that converting a building to fully sustainable is feasible. In the paper [

3], different solutions of renewable systems for two zones in Mexico were analyzed. Consideration for the whole Mexico system can be found in [

4]. A very interesting overview of the possibilities of building renewable systems is presented in [

5,

6,

7]. In [

8,

9], one can find considerations regarding the sustainable energy system in Japan. All of these publications raise the issue of storing large amounts of energy, which is only possible using synthetic fuels. Therefore, many publications concern the development of technologies necessary for sustainable energy systems. In the works [

10,

11], one can find the state of knowledge about large electrolyzers for converting electrical energy into the chemical energy of hydrogen. Much attention is devoted to large-scale energy storage [

12,

13,

14]. It should be noticed that currently available battery storage systems have capacities in the order of GW, while for seasonal storage on the country scale, tens of TWh are required. Therefore, a lot of publications are devoted to technologies which could be used for the conversion of renewable electricity into chemicals [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

In 2024, total electricity consumption in Poland reached nearly 160 TWh [

20]. According to IEA online data for 2023, coal ranks first in the Polish electricity generation mix, accounting for 60.1%. Weather-dependent renewable sources, such as wind turbines (WTs) and photovoltaic (PV) panels, accounted for 21% of production, while biofuels for 4.7%. However, under good weather conditions, in 2024, renewable energy sources accounted for two-thirds of electricity production, but at the same time, under bad weather conditions, there were 73 h when the share of renewable energy was below 1% of total production. Because of the limited capacity of energy storage facilities (pumped-storage power plants and battery storage systems), fossil fuel sources serve currently as stabilizing sources. The question remains how the system will be balanced when fossil fuel sources are decommissioned, which is foreseen 25 years from now. Poland’s energy policy includes the construction of nuclear power plants, but they will operate in base-load mode. Using them to balance the system would mean operating at partial loads, which would radically reduce their profitability. Biomass could be a potential solution for the Polish system. It is estimated that the potential for methane production from biomass fermentation is 9 billion cubic meters annually. Poland also has significant resources of solid biomass in the form of straw from grain production and waste wood from furniture and other wood goods production.

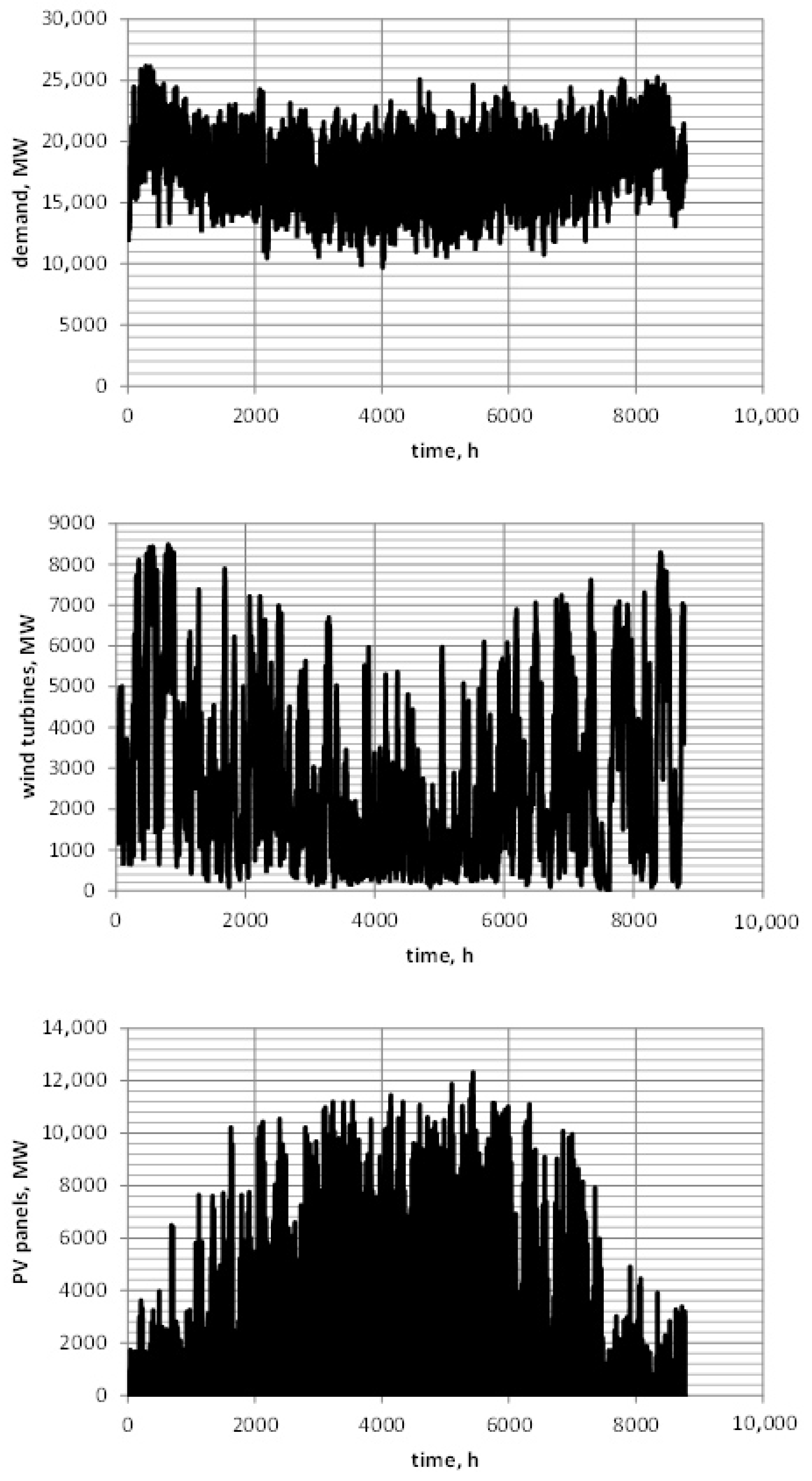

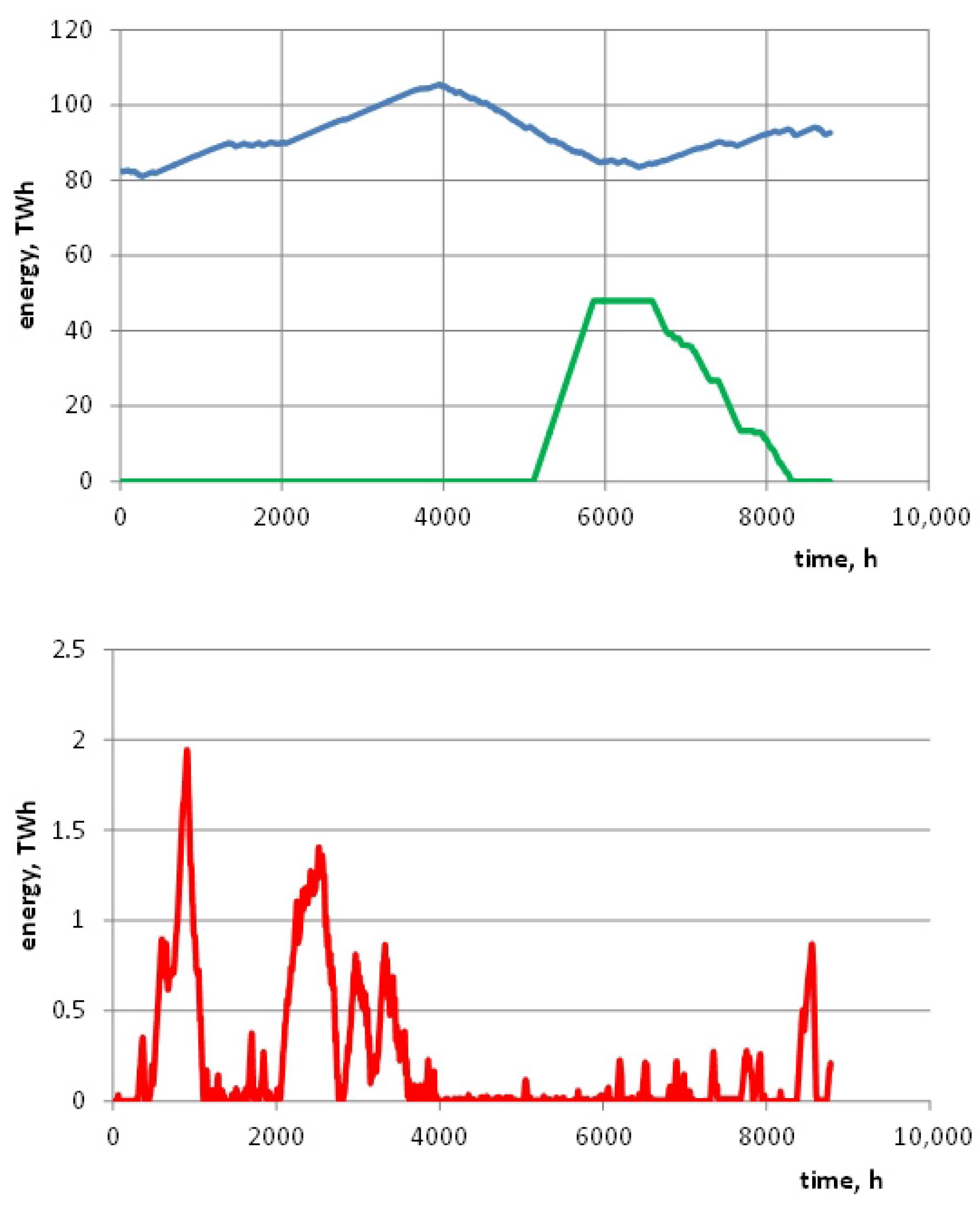

Figure 1 shows the annual patterns of electrical power demand and the total power generated by wind turbines and photovoltaic panels. The graphs start at the beginning of the year. As can be seen, winter demand (left and right ends of curves) is slightly higher than summer demand, and energy production from PV panels occurs primarily in the summer months, while wind turbine energy production is higher in winter than in summer. The main message from this figure is that electricity demand varies from 10 to 25 GW, showing mainly short-term fluctuations resulting from the daily and weekly rhythm of life, and PV and WT as well are affected both by daily, weekly, as well as seasonal changes.

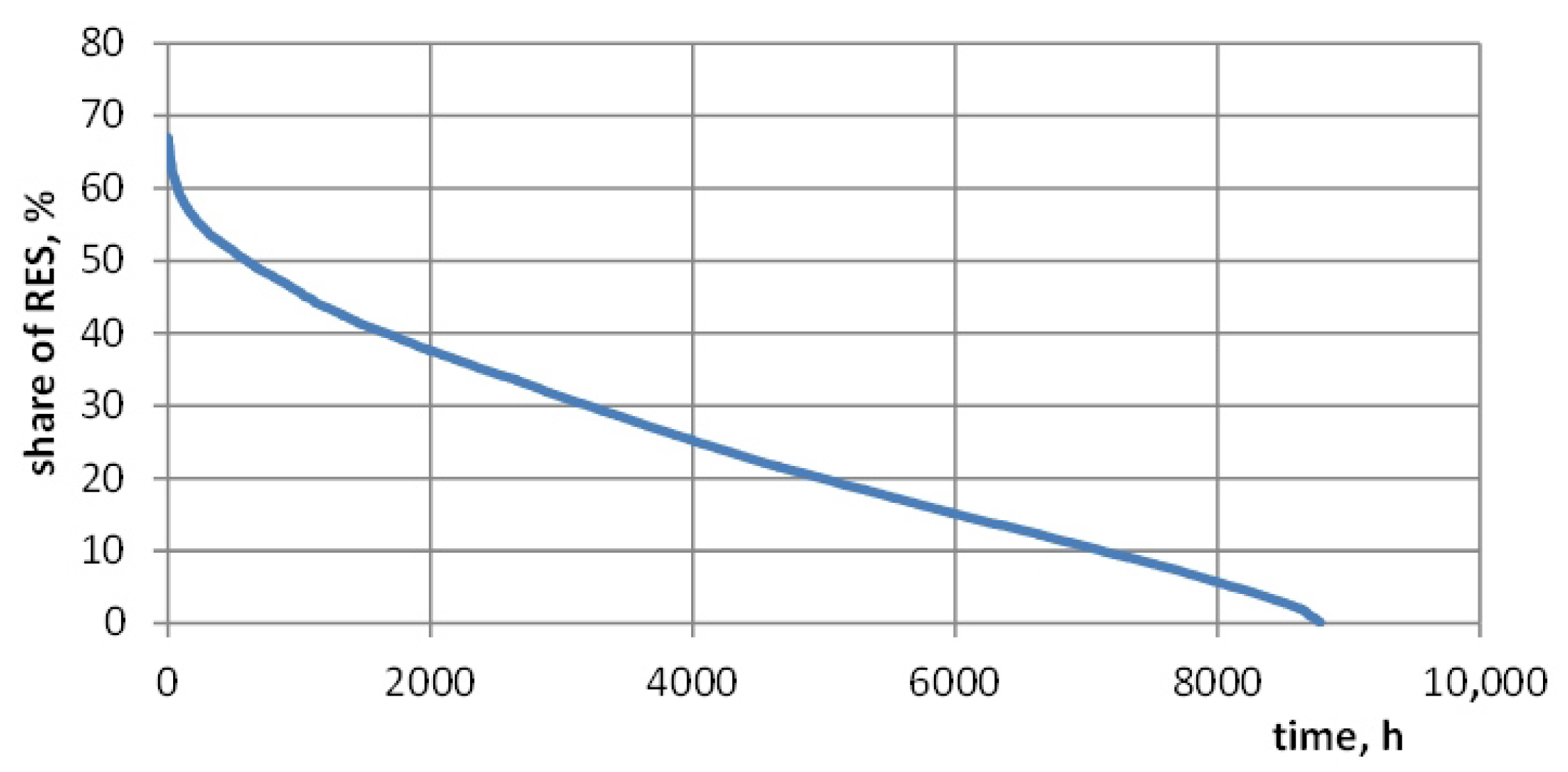

Figure 2 shows the duration curve of the coverage of the demand for electric power by renewable sources. As it can be seen, the maximum of about two-third is reached for a very short period of time. For about 5000 h a year, renewable energy covers more than 20% of electricity demand.

2. Concept of Becoming Fully Sustainable

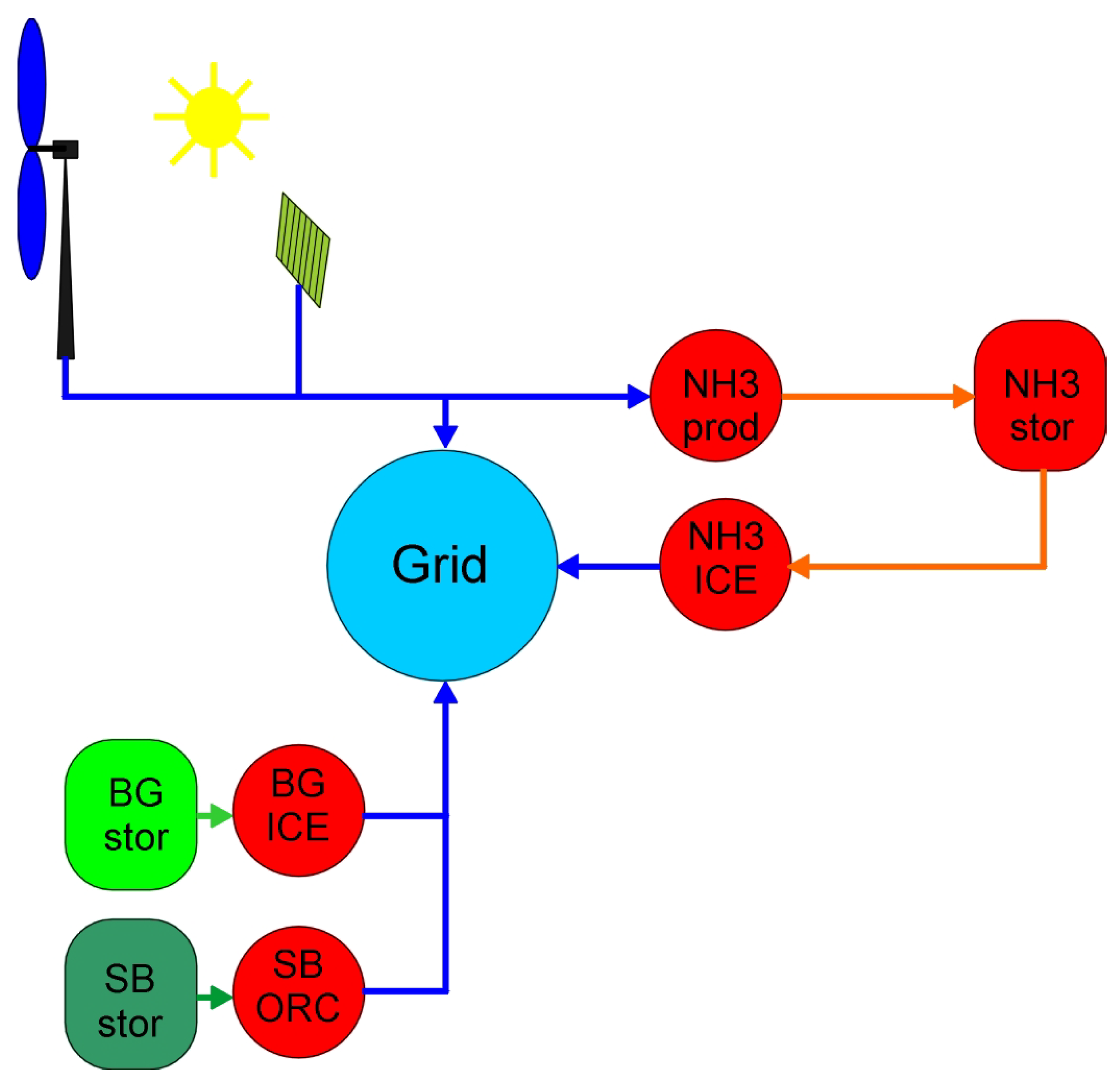

Figure 3 shows the concept of an energy system based solely on renewable sources. It consists of weather-dependent renewable sources: wind turbines (WTs) and a PV panel, biomethane tanks (BG stor), biomethane-fueled internal combustion engines (BG ICE), solid biomass storage facilities (SB stor), ORC systems powered by solid biomass (SB ORC), ammonia production systems powered by excess electricity generated from renewable sources (NH3 prod), ammonia tanks (NH3 stor), and ammonia-fueled internal combustion engines (NH3 ICE). When energy production from weather-dependent renewable sources do not cover the demand, the stored chemical energy from biomethane, solid biomass, and ammonia is utilized. When energy production from weather-dependent renewable sources exceeds demand, ammonia is produced and stored in pressurized steel tanks.

3. Methods

Calculations were made for the year 2024, when the following energy amounts were noted:

Total electricity consumption, 157.8 TWh;

Electricity production in wind turbines, 23.5 TWh;

Electricity production in PV panels, 17.4 TWh.

In addition, the following energy potential of biomass was assumed:

Biomethane: 8 billion cubic meters, which corresponds to 82.4 TWh of chemical energy, which, with combustion engine efficiency of 50%, corresponds to 41.2 TWh of electricity. It was assumed that biomethane is produced at a constant rate throughout the year, with excess stored in existing underground reservoirs currently used for natural gas storage.

Straw: 12 million tons, equivalent to 48 TWh of chemical energy. Given the assumed efficiency of biomass-powered ORC systems, this equates to 9.6 TWh of electricity. It was assumed that straw is produced in August and stored in landfills at CHP plants equipped with ORC modules.

It has to be stressed that total straw production in Poland is higher and estimated at the level of 30+ millions tons annually. Part of the straw is needed for sustainable agriculture, and thus, only part of this amount can be used for energy production. It was assumed that straw is used as close as possible to the place where it is produced—in local heating plants, which could be equipped with ORC modules. In the case of biomethane, it was assumed that it will be purified and introduced to the gas network in order to possibly widely distribute and store it in existing underground natural gas storages.

Assumed energy conversion efficiencies are presented in

Table 1.

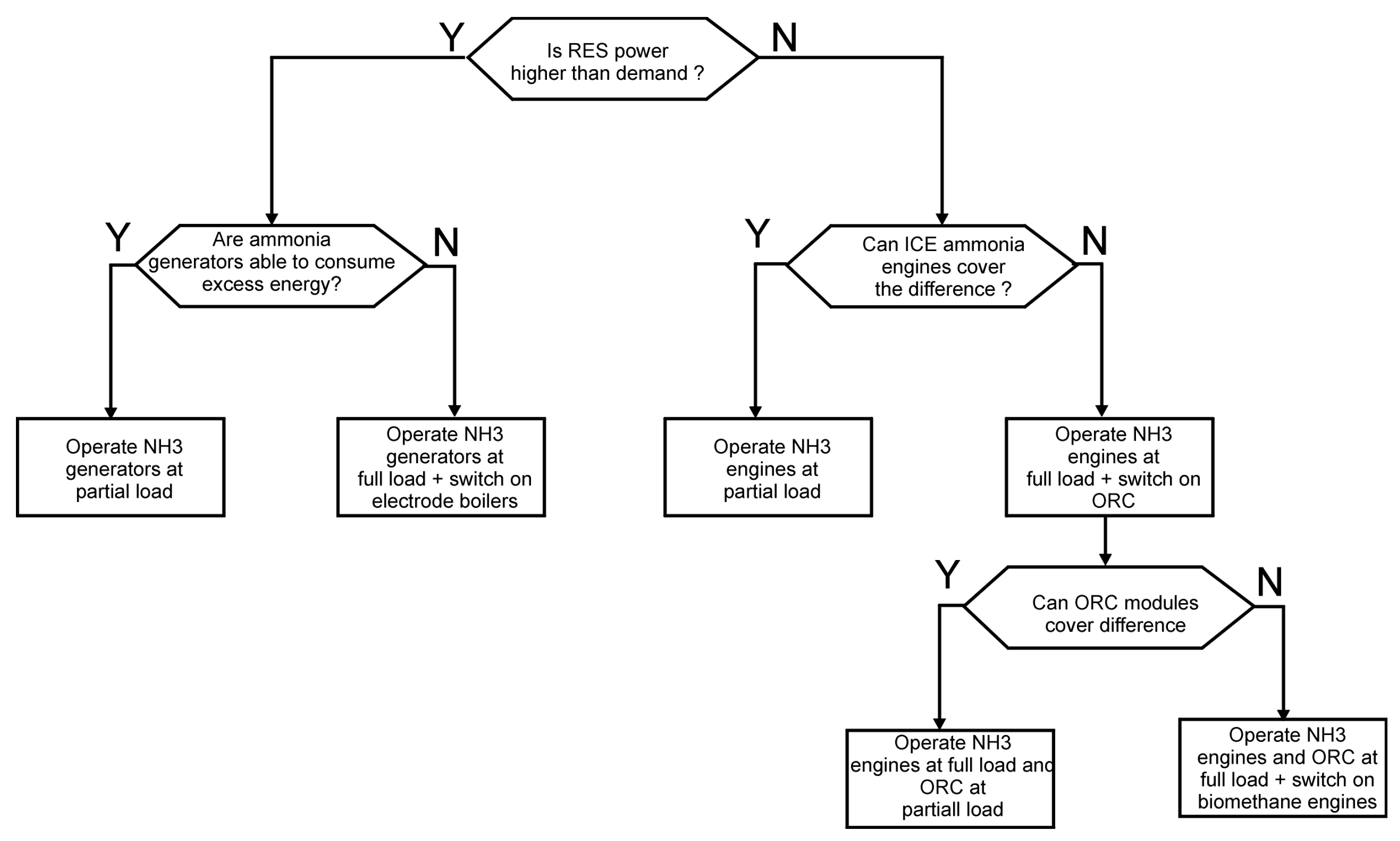

Calculations were made using self-made Fortran code with the general flowchart presented in

Figure 4. It was assumed that the efficiency of the system elements operate with the same efficiency at partial load. Such an assumption, at first glimpse, seems to be oversimplified; however, one has to take into account that in fact, the system consists of hundreds of distributed engines, ammonia generators, and ORC modules, and partial load of the system is achieved by switching part of these hundreds, but each of them can operate close to full load.

It should be emphasized that, in reality, a more complex operation of the system would be applied, utilizing the entire flexibility of the system. However, the purpose of this paper is an assessment of the total power of system elements that would be necessary to convert an energy system to fully renewable.

Five modes of Poland’s energy system operation were analyzed and summarized in

Table 2. For Case A, an identical 4.3-fold increase in installed PV and WT capacity was assumed, along with the simultaneous installation of ammonia generators with a total capacity of 10 GW and electricity generation capacity of 10 GW of ammonia-fueled engines, 24 GW of biomethane-fueled engines, and 10 GW of ORC modules. The capacities refer to the energy produced by the devices and were selected as a result of multi-variant calculations based on the assumption that the energy needs of the Polish system are covered 100% every hour of the year. Case B differs from Case A in that only the installed TW capacity was increased. Case C, in turn, represents an increase in installed PV capacity only. Case D assumed no ammonia generators and therefore no ammonia-fueled engines, while Case E additionally assumed no ORC modules. For Cases A–C, it was assumed that if electricity production from the wind turbine and photovoltaic panels exceeds consumption, the excess is directed to ammonia generators. If the excess exceeds the installed capacity of the generators, the difference is used to power the electrode boilers and convert electricity to heat. Otherwise, if the wind turbine and photovoltaic panels produce too little energy, the ammonia-powered engines are activated first. If this is insufficient, the ORC modules are activated, and finally, biomethane powered engines are activated. This order is intended to minimize the size of the ammonia tanks and the need for straw storage. Additionally, it was assumed that due to the relatively low electrical efficiency of ORC modules, their power is used only during the winter to utilize all heat for space heating.

For each case, the required WT and PV installed power was searched, which would cover the energy demands in every hour of the year, with biomethane consumption not exceeding annual production. The hourly power demand for each hour of the analyzed year was assumed to be equal to the demand recorded in 2024. A similar assumption was made for the annual energy production profile of the WT and PV.

4. Results

In

Table 3, the required increase in installed power of WT and PV in Poland with respect of those that existed in 2024, as well as the required installed power of other system components are summarized.

The results of the calculations for Case A are presented in

Figure 5. The upper part of the figure shows the amount of energy in methane tanks (blue line) and the straw reserves (green line). The lower part of the figure shows the charge status of the ammonia tanks. It is worth noticing that the maximum amount of stored chemical energy of ammonia is only 2 TWh, which corresponds to a mass of approximately 400 kilotons, which corresponds to only six largest tanks currently available on the market. The chemical energy of biomethane varies in the range of 80–100 TWh, showing that the system can operate with usage of 20 TWh capacity biomethane storages. This is lees than currently used in underground natural gas storages in Poland. The chemical energy of straw increases during agricultural harvesting time and decreases as it is consumed by ORC modules.

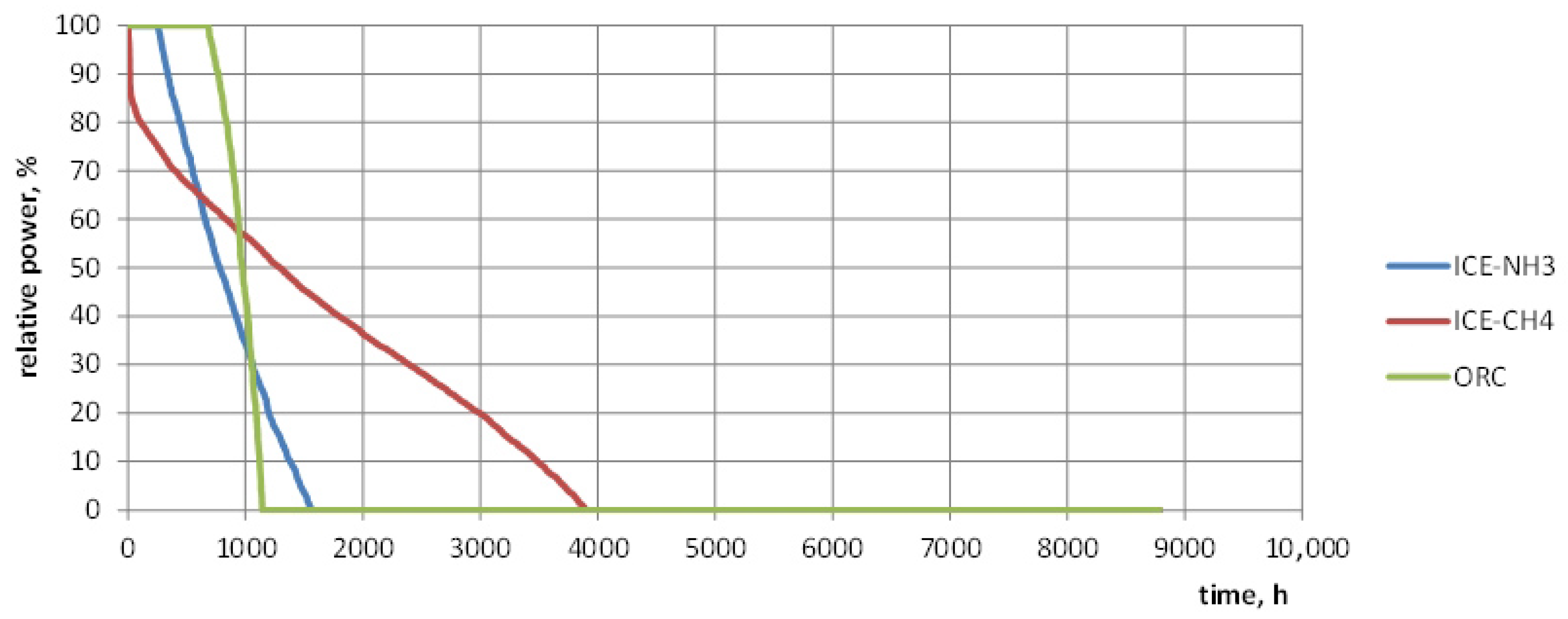

Figure 6 shows the duration curve of the installed equipment’s capacity utilization. As one can see, the equipment is used for a very limited time—for ORC modules, it is just over 1000 h per year; for ammonia-powered engines, about 1500 h; and for methane-powered engines, around 4000 h. The economic viability of operating these devices would require market solutions that would provide financing for the equipment to ensure their readiness for operation.

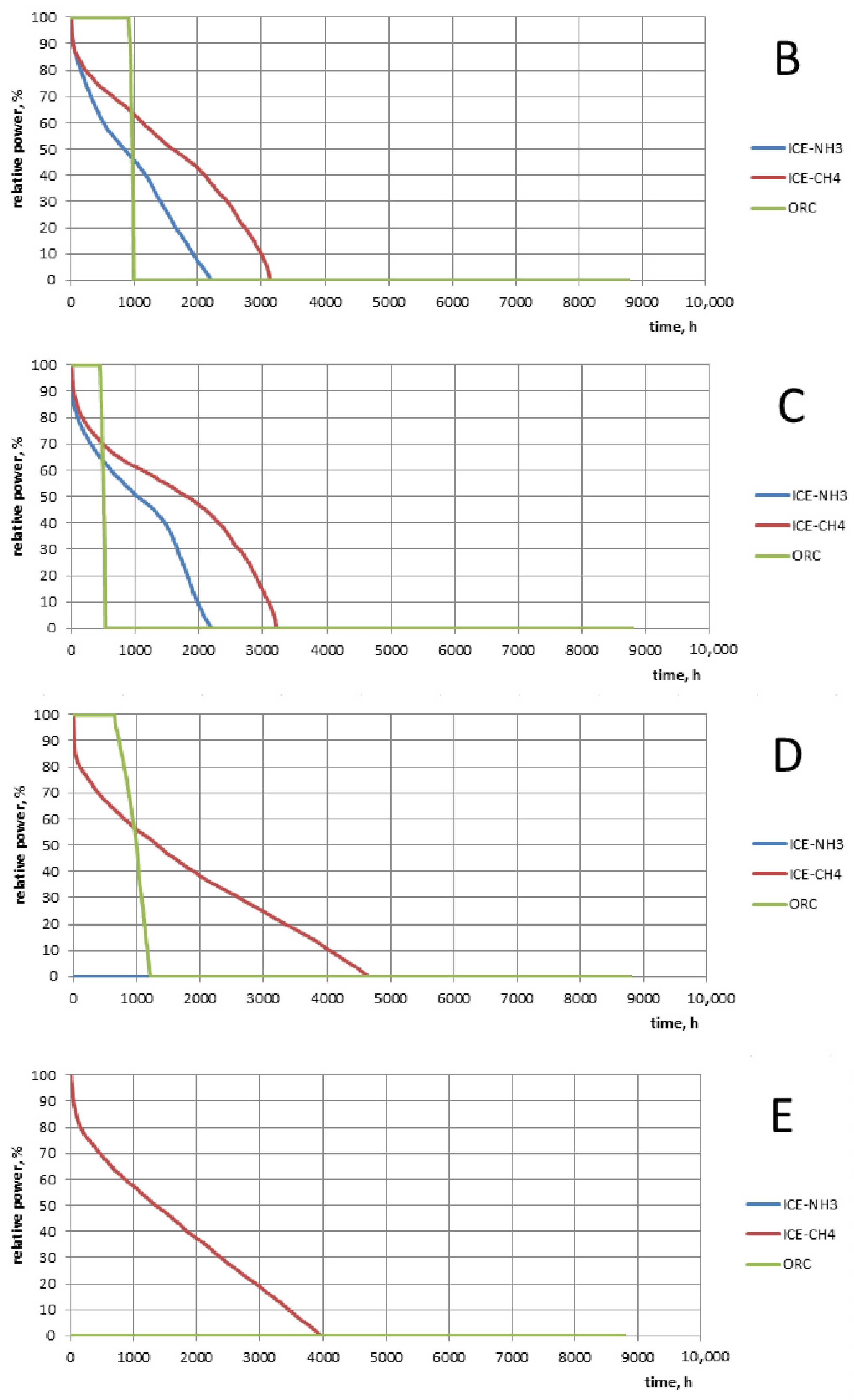

Corresponding duration curves for Cases B–E are presented in

Figure 7. Case D is particularly interesting, as the system has no ammonia-fueled engines and therefore requires no ammonia generators or tanks. At the same time, the required installed power of the wind turbine and PV is not significantly greater than in Case A. In all analyzed cases, annual utilization of the installed power of ammonia generators, ICE engines, as well as ORC modules are relatively low. For more than half of the year, installed power is not needed at all. As it was mentioned previously, this imposes a need for market regulations regarding installed power.

As previously mentioned, it was assumed that if production of electricity in PV and TW is greater than the sum of consumption and installed power of electrolyzers, the remaining energy is supplied to electrode boilers, which are of low CAPEX costs.

Table 4 shows the annual amount of energy supplied to electrode boilers in all five cases.

The numbers presented in

Table 4 show that in the case of no ammonia storage capacity, a large volume of electricity has to be converted to heat, which can be used for space heating at least in winter.

All analyzed cases prove that it is possible to achieve a fully renewable electricity system based on PV and WT using solid and gaseous biomass as the energy for delivering electricity in case of no wind and no sun. In the case of no ammonia generators, excess electricity has to be either wasted or converted to heat in large amounts.

5. Summary and Conclusions

The transformation of energy systems to achieve full climate neutrality is a difficult task in countries that lack suitable natural conditions. Norway is an example of a country with ideal natural conditions, thank to which it can meet almost all its electricity needs from weather-independent, renewable hydropower plants. In countries like Poland, wind turbines and photovoltaic panels may be the primary sources of climate-neutral electricity. However, these sources are weather-dependent and therefore not adaptable to the electricity demand. However, in countries like Poland, biomass, both in the form of solid biomass as well as of biogas, can play a particularly important role. It can be relatively easily stored for a long time and used when electricity demand exceeds the current capacity of wind turbines and photovoltaic panels. This paper analyzes five different hypothetical configurations of Poland’s energy system, which ensure full climate neutrality while simultaneously meeting the electricity demand every hour of the year. As the calculations show, this can be achieved in several ways. Particularly interesting are configurations A and D. In the first configuration, the currently installed capacity of wind turbines and photovoltaic panels would have to be increased 4.3 times, and additionally, in the system, 10 GW of ammonia production capacity and the same amount of combustion engines adapted to ammonia combustion should be installed. In configuration D, the capacity of wind turbines and panels would have to be increased 4.8 times, but this would eliminate the use of ammonia as a method of energy storage. Of course, the fundamental question is the cost of such a solution. Currently, wind turbines in Poland have a total installed capacity of approximately 10 GW. Increasing it 4.8 times (variant D) would require the installation of an additional 38 GW. Assuming the CAPEX cost of a wind turbine based on reports from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory at USD 2000/kW, a total cost of USD 76 billion of newly erected wind turbines can be estimated. A similar cost would be associated with a 4.8 times increase in installed photovoltaic power. The total cost is therefore in the range of USD 150 billion. Considering the current plans of the Polish government to build a nuclear power plant with a capacity of approximately 4 GW and an estimated cost of USD 50 billion, the cost of USD 150 billion does not seem excessive. It should be noted that the 4 GW of planned nuclear power plant capacity represents only a portion of Poland’s energy needs, while USD 150 billion invested in renewable sources would meet all of these needs. The considerations presented herein concern the current demand for electricity. A significant increase in electricity demand is expected in the future, driven by factors such as the development of electromobility and the electrification of heating plants. While this will necessitate the installation of even greater generating capacity, it will also increase the ability to match energy demand to current production. The main goal of this article was to demonstrate that achieving climate neutrality in the electricity generation system in a country like Poland is possible. It should be stated that it is possible within a reasonable cost range.