Transient CFD Analysis of Combustion and Heat Transfer in a Coal-Fired Boiler Under Flexible Operation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calculation Simulation Setting and Working Condition Design

2.1. Introduction of Simulation Object

2.2. Computational Simulation Method

2.3. Boundary Conditions

2.4. Grid Independence Verification

3. Simulation Results and Analysis

3.1. Effect of Variable Load Rate on Heat Transfer of the Burner

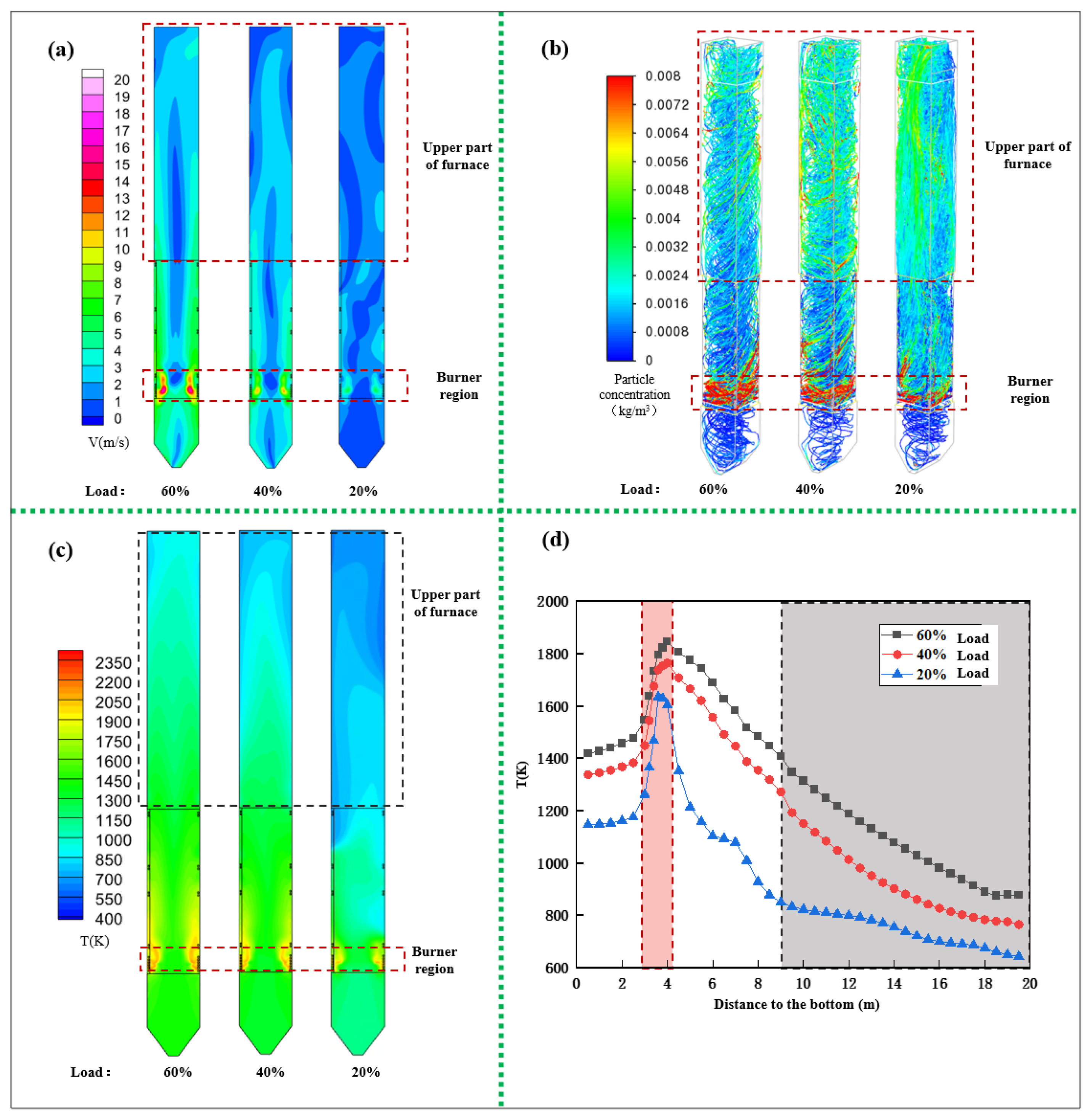

3.2. Influence of Different Loads on Boiler Combustion Characteristics

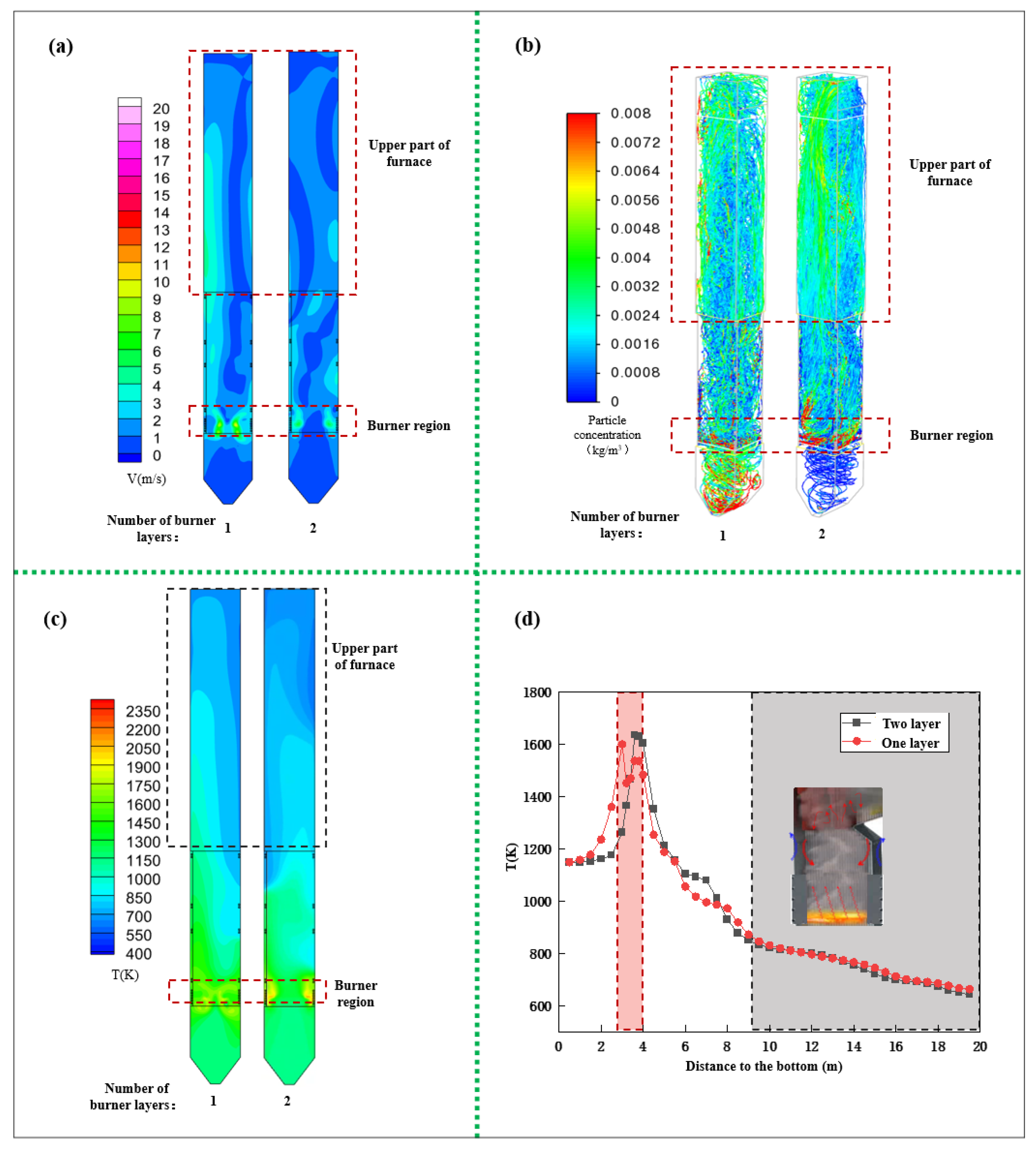

3.3. Influence of the Number of Burner Opening Layers on Boiler Combustion Characteristics Under 20% Load

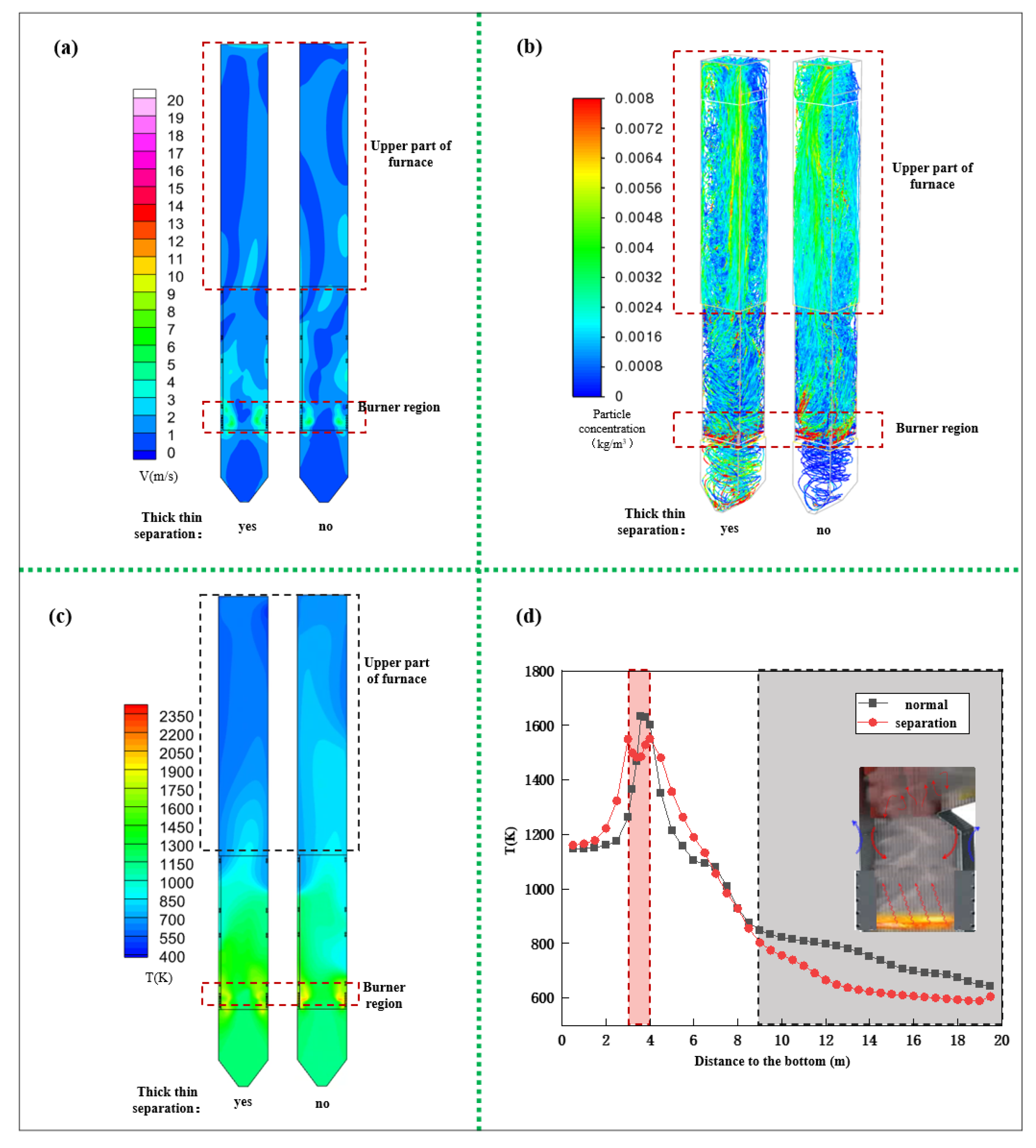

3.4. The Effect of Rich–Lean Separation on Boiler Combustion Characteristics at 20% Load

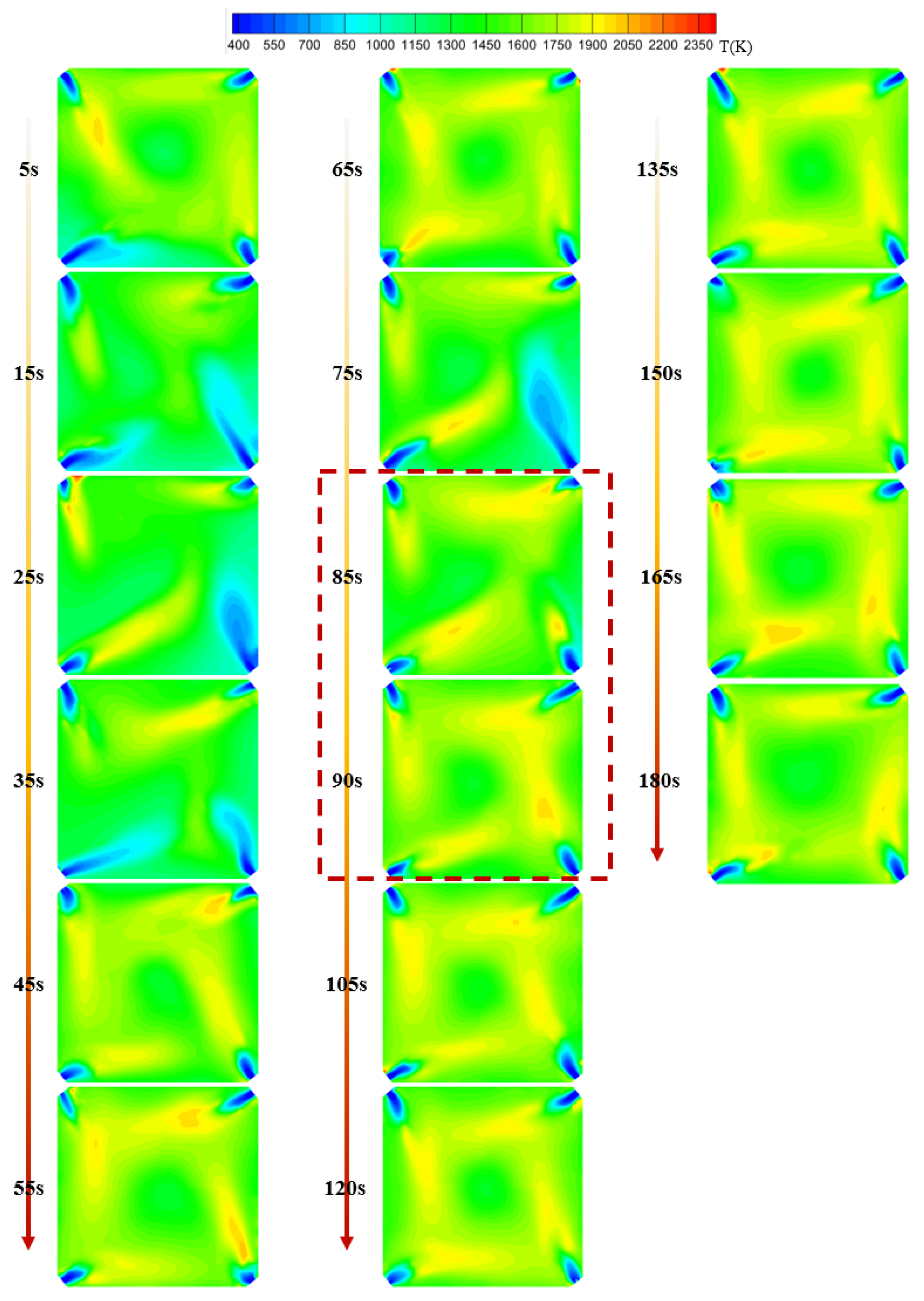

3.5. The Influence of Different Variable Load Rates on the Combustion-Heat Transfer Characteristics of the Boiler

3.6. Nonlinear Load-Control Strategy and Limitations

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Near the furnace outlet, heat flux density increases over time. While variable load rates of 2%/min, 4%/min, and 6%/min minimally affect the size of the high-heat-flux area, they significantly impact localized heat flux values. At 2%/min and 4%/min, heat flux is uniform along the upper wall, but at 6%/min, it becomes uneven, with higher density adjacent to the dense pulverized coal flow compared to the fresh coal flow side.

- (2)

- At 60% load, the flow field shows symmetry, and the flame has optimal fullness with a temperature of 1200 K spanning from the furnace bottom to the upper section. At 40% load, the upper flow field begins to distort, and by 20% load, the flow field becomes disordered, exhibiting uneven temperature distributions and reduced high-temperature flames above 1900 K. Increasing load results in higher particle concentrations near the burner wall and lower concentrations near the upper wall.

- (3)

- At 20% load, the flow field in furnace with single-layer burner is more stable than with two-layer burner. Particle concentrations near the boiler walls are lower, while concentrations in the cold ash hopper are higher. The high-temperature region is centrally concentrated, with fewer areas exceeding 1900 K. Single-layer burners show lower average temperature peaks near 3 m from the furnace bottom. Boilers with rich–lean separation improve airflow fullness and achieve a more uniform temperature distribution, reducing wall particle concentrations. For the 20% low-load condition, the combined configuration of the two-layer burner and rich–lean separation is recommended.

- (4)

- A nonlinear control strategy is necessary as the load transitions from low to high. In extremely low operating ranges, load regulation rates should remain below the rated variable load rate (Vref), while they can be increased beyond Vref in medium–high ranges. Integral averaging of these regulation rates ensures compliance with rated variable load requirements while managing thermal stress.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A1 | Pre-exponential factors of devolatilization at low temperature (s−1) |

| A2 | Pre-exponential factors of devolatilization at high temperature (s−1) |

| E1 | Activation energy of devolatilization at low temperature (J/kmol) |

| E2 | Activation energy of devolatilization at high temperature (J/kmol) |

| Mar | Moisture, as received (wt.%) |

| Aar | Ash, as received (wt.%) |

| Var | Volatile matter, as received (wt.%) |

| FCar | Fixed carbon, as received (wt.%) |

| Car | Carbon, as received (wt.%) |

| Har | Hydrogen, as received (wt.%) |

| Oar | Oxygen, as received (wt.%) |

| Nar | Nitrogen, as received (wt.%) |

| St,ar | Total sulfur, as received (wt.%) |

| Qnet,ar | Net calorific value, as received (MJ·kg−1) |

| t | Time (s) |

| T | Temperature (K) |

| v | Gas velocity (m/s) |

| Abbreviations | |

| MCR | Maximum continuous rating |

| SOFA | Separated overfire air |

| PA | Primary air |

| SA | Secondary air |

| Vref | Velocity reference |

References

- Decastro, M.; Salvador, S.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Costoya, X.; Carvalho, D.; Sanz-Larruga, F.; Gimeno, L. Europe, China and the United States: Three different approaches to the development of offshore wind energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 109, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, R.; Cai, P.; Xiao, Z.; Fu, H.; Guo, T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Song, X. Risk in solar energy: Spatio-temporal instability and extreme low-light events in China. Appl. Energy 2024, 359, 122749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Energy Administration Released the National Power Industry Statistics from January to July. China Electr. Power News, 21 August 2023. (In Chinese)

- Ouyang, T.; Qin, P.; Tan, X.; Wang, J.; Fan, J. A novel peak shaving framework for coal-fired power plant in isolated microgrids: Combined flexible energy storage and waste heat recovery. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 133936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ho, M.S.; Xie, C.; Stern, N. China’s flexibility challenge in achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. Control characteristic analysis of typical coal-fired boilers during low load or variable load running. Therm. Power Gener. 2018, 47, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, P.; Wang, F.; Li, Q.; Zhao, G.; Ma, J.; Ma, S. Research and challenge of coal power technology development in china under the background of dual carbon strategy. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 2641−2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Z.; He, E.; Jiang, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Combustion characteristics and NOx formation of a retrofitted low-volatile coal-fired 330 MW utility boiler under various loads with deep-air-staging. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 110, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, S.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Ding, X. Combustion stability and NOx emission characteristics of a 300 MWe tangentially fired boiler under ultra-low loads with deep-air staging. Energy 2023, 269, 126795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, S.; He, X.; Tao, L.; Shi, H.; Chen, D. Technical problems occurring in ultra-low load operation of pulverized coal-fired boilers and the solutions. J. Chin. Soc. Power Eng. 2019, 39, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Li, S.; Ren, Y.; Yao, Q.; Yuan, Y. Investigation of mechanisms in plasma-assisted ignition of dispersed coal particle streams. Fuel 2016, 186, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, B.; Zeng, L.; Che, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z. Anthracite combustion characteristics and NOx formation of a 300 MWe down-fired boiler with swirl burners at different loads after the implementation of a new combustion system. Appl. Energy 2017, 189, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.F.; Zhang, S.Y.; He, X.; Tao, L.; Shi, H.F.; Chen, R.Y. Technical problems and countermeasures for ultra-low load operation of pulverized coal boilers. J. Power Eng. 2019, 39, 784–791+803. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, Q. Effect of the anthracite ratio of blended coals on the combustion and NOx emission characteristics of a retrofitted down-fired 660-MWe utility boiler. Appl. Energy 2012, 95, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Huang, C.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Z.; Song, J.; Fang, F.; Su, J.; et al. Industrial measurement of combustion and NOx formation characteristics on a low-grade coal-fired 600MWe FW down-fired boiler retrofitted with novel low-load stable combustion technology. Fuel 2022, 321, 123926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Wang, H.; Lyu, Q.; Zhu, S.; Zeng, X.; Su, K. Research Progress on Deep Peak Shaving Technology of Pulverized Coal-fired Boiler Power Unit. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 8772–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B. Cause analysis on transversal cracks formation of water wall tubes in a boiler. Phys. Test. Chem. Anal. Part A Phys. Test. 2018, 54, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Cai, W.; Du, S.; Dong, S.; Gao, D.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. Cause analysis and treatment measures of water cooling wall pipe leakage in a power station boiler. Corros. Prot. 2022, 43, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Analysis and research on transverse cracks in high temperature corrosion zone of boiler water wall. Technol. Innov. Appl. 2021, 11, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Zhao, B.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Tian, S.; Zhong, Z.; Fu, Q. Study of NOx reduction during the adjustment of boiler combustion. Power Syst. Eng. 2015, 31, 41–43+6. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Wang, C.; Lu, X.; An, G.; Yan, H.; Ma, H.; Yan, X. Combustion Adjustment in Initial Startup Stage of 660MW Supercritical Fossil Power Unit. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. IOP Publ. 2021, 1732, 012113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Zeng, D.; Fang, F.; Niu, Y. Modeling and flexible load control of combined heat and power units. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 166, 114624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Yan, H.; Yan, J. Optimization on coordinate control strategy assisted by high-pressure extraction steam throttling to achieve flexible and efficient operation of thermal power plants. Energy 2022, 244, 122676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Kang, Y.; Wei, W. Research on a novel universal low–load stable combustion technology. Energy 2024, 310, 133223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Huang, Q.; Niu, F.; Li, S. Recirculating structures and combustion characteristics in a reverse-jet swirl pulverized coal burner. Fuel 2020, 270, 117456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Ding, X.; Kang, Z. Retrofit and application of pulverized coal burners with LNG and oxygen ignition in utility boiler under ultra-low load operation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yao, G.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Xu, Z. Study on low-load combustion characteristics of a 600 MW power plant boiler with self-sustaining internal combustion burners. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 267, 125859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhou, H.; Li, Z.; Zeng, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Hui, J.; Lin, J.; Su, K.; Wang, H.; Ding, H.; et al. Wide-load combustion characteristics of lean coal tangential preheating combustion. Energy 2025, 323, 135845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.X. Contrastive research of two kinds of bias burners in 360t/h coal-fired boiler. Power Syst. Eng. 2011, 27, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; Qian, L.; Meng, S.; Tan, Y. Numerical Study on the Stereo-Staged Combustion Properties of a 600 MWe Tangentially Fired Boiler; Cleaner Combustion and Sustainable World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1109–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; Zhao, N.; Wu, S.; Tan, Y. Numerical Simulation of the Gas-Solid Flow in a Square Circulating Fluidized Bed with Secondary Air Injection; Cleaner Combustion and Sustainable World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.B.; Jia, G.; Zhai, S.B.; Pang, Z.Z. MW-level experimental study on combustion characteristics of anthracite and bituminous coal mixed fuel. Boil. Manuf. 2023, 5, 15–17+35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gu, W.L.; Sun, S.Z.; Wang, J.J.; Zhai, S.B.; Xu, Y.H.; Wang, M.H.; Song, X.; Yan, Y.F. Experimental study on the coupling combustion of biomass particles and pulverized coal. Boil. Manuf. 2021, 3, 8–10+21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Wei, G.; Song, M.; Diao, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, Q.; Shen, T. Experimental study on combustion performance of a novel central fuel-rich direct current pulverized-coal burner. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 7530–7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ye, Z.; Gao, J. Effect of the primary air velocity on ignition characteristics of bias pulverized coal jets. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 3182–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liao, Y.; Lin, J.; Dou, C.; Huang, Z.; Yu, X.; Yu, Z.; Chen, C.; Ma, X. Numerical simulation of the co-firing of pulverized coal and eucalyptus wood in a 1000MWth opposed wall-fired boiler. Energy 2024, 298, 131306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.F.; Qi, H.Y.; Xu, X.C.; Baudoin, B. Numerical simulation of flow field in tangentially fired boiler using different turbulence models and discretization schemes. J. Chin. Soc. Power Eng. 2001, 02, 1128–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Irfan, M.; Niazi, U.M.; Shah, I.; Legutko, S.; Rahman, S.; Alwadie, A.S.; Jalalah, M.; Glowacz, A.; Khan, M.K.A. Centrifugal Compressor Stall Control by the Application of Engineered Surface Roughness on Diffuser Shroud Using Numerical Simulations. Materials 2021, 14, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benim, A.C.; Canal, C.D.; Boke, Y.E. Computational investigation of oxy-combustion of pulverized coal and biomass in a swirl burner. Energy 2022, 238, 121852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Tan, H.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Numerical simulation on the influence of secondary air ratio and swirling intensity on the performance of a pre-combustion low nitrogen swirl burner. Clean Coal Technol. 2022, 28, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Wu, L.; Wang, T.; Sun, B. Numerical simulation of ammonia combustion with sludge and coal in a utility boiler: Influence of ammonia distribution. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 111, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, M.A. Rate of combustion of size-graded fractions of char from a low-rank coal between 1 200 K and 2 000 K. Combust. Flame 1969, 13, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H. Research on flexible load variation control strategy for 600 MW coal-fired power unit. Northeast. Power Technol. 2025, 3, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Liu, Z.; Miao, P.; Zheng, X.; Xing, W.; Jia, N. Investigation on on-off characteristic of 80 MW pulverized coal industrial water boiler. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 4627−4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L. Prevention of slagging in boilers and retrofitting horizontal rich/lean burners thereof. Therm. Power Gener. 2005, 34, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Duan, L.; Ji, R.; Niu, F. Research progress of peaking technology for flexibility modification ofpulverized coal boiler combustion system. Coal Qual. Technol. 2024, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Proximate Analysis/(wt.%) | Ultimate Analysis/(wt.%) | Calorific Value/(MJ·kg−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar | Aar | Var | FCar | Car | Har | Oar | Nar | St,ar | Qnet,ar | |

| Shenhua bituminous coal | 9.36 | 6.48 | 28.11 | 56.05 | 69.83 | 3.94 | 9.08 | 0.91 | 0.40 | 26.42 |

| Item | Unit | Load | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60%MCR | 40%MCR | 20%MCR | ||

| Coal mass flow rate | kg/s | 0.189 | 0.126 | 0.063 |

| Total air mass flow rate | kg/s | 2.04 | 1.36 | 0.68 |

| Primary mass flow rate | kg/s | 0.468 | 0.312 | 0.156 |

| Secondary mass flow rate | kg/s | 1.224 | 0.816 | 0.408 |

| Overfire air mass flow rate | kg/s | 0.348 | 0.232 | 0.116 |

| Primary air temperature | K | 368 | 368 | 368 |

| Secondary air temperature | K | 573 | 573 | 573 |

| Burnout air temperature | K | 573 | 573 | 573 |

| Particle diameter | μm | 5.83~230 | 5.83~230 | 5.83~230 |

| Particle Diameter (μm) | >5 | >10 | >20 | >30 | >50 | >90 | >160 | >200 | >230 |

| Mass Fraction (%) | 97.0 | 89.2 | 74.5 | 62.1 | 42.3 | 18.7 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Load | Mass Fraction of CO | Mass Fraction of O2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA-Air6 (3.71 m) | PA-Air4 (3.61 m) | PA-Air2 (3.31 m) | SA-Air6 (3.71 m) | PA-Air4 (3.61 m) | PA-Air2 (3.31 m) | |

| 60%MCR | 0.002857 | 0.002938 | 0.002545 | 0.03618 | 0.04136 | 0.06150 |

| 40%MCR | 0.002792 | 0.003205 | 0.002530 | 0.03312 | 0.03915 | 0.06301 |

| 20%MCR | 0.002775 | 0.004446 | 0.002251 | 0.02584 | 0.03067 | 0.07350 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X.; Sun, S. Transient CFD Analysis of Combustion and Heat Transfer in a Coal-Fired Boiler Under Flexible Operation. Energies 2026, 19, 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020478

Li C, Zhang Z, Feng D, Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Guo X, Sun S. Transient CFD Analysis of Combustion and Heat Transfer in a Coal-Fired Boiler Under Flexible Operation. Energies. 2026; 19(2):478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020478

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chaoshuai, Zhecheng Zhang, Dongdong Feng, Yi Wang, Yongjie Wang, Yijun Zhao, Xin Guo, and Shaozeng Sun. 2026. "Transient CFD Analysis of Combustion and Heat Transfer in a Coal-Fired Boiler Under Flexible Operation" Energies 19, no. 2: 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020478

APA StyleLi, C., Zhang, Z., Feng, D., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Guo, X., & Sun, S. (2026). Transient CFD Analysis of Combustion and Heat Transfer in a Coal-Fired Boiler Under Flexible Operation. Energies, 19(2), 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020478