Adaptive PID Control Based on Laplace Distribution for Multi-Environment Temperature Regulation in Smart Refrigeration Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- A new probabilistic adaptive PID framework that leverages the inverse Laplace density for dynamic gain modulation without explicit model identification.

- (ii)

- A theoretical formulation for L(t) and a detailed explanation of how the scale parameter b governs the trade-off between control responsiveness and energy consumption.

- (iii)

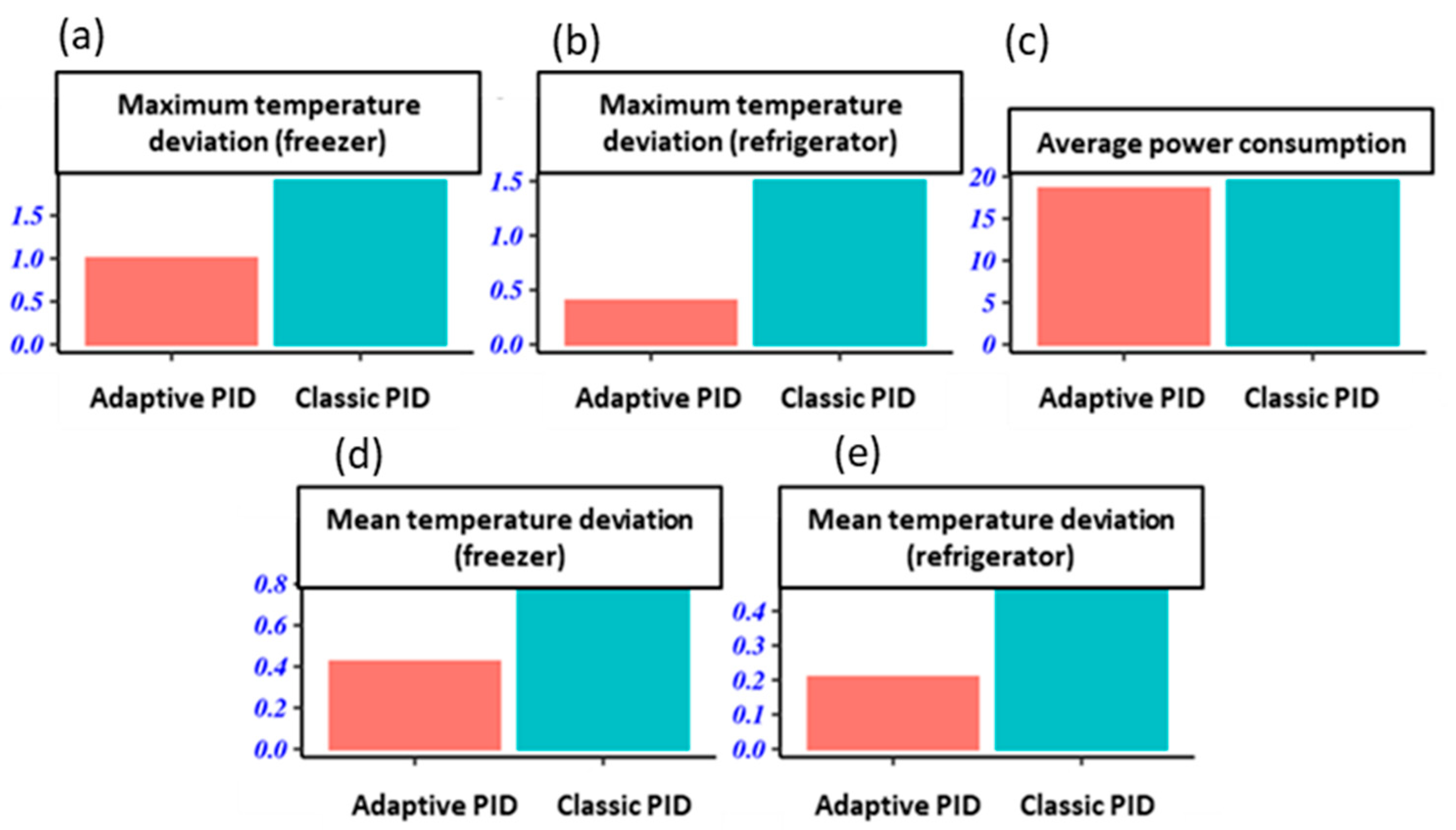

- Experimental validation on a real refrigerator system, demonstrating improved temperature stability, reduced overshoot, and approximately 4–5% energy savings compared to classical PID and a commercial embedded controller.

- (iv)

- A practical design suitable for low-power embedded controllers, enabling easy integration into existing home appliance architectures.

2. Methodology

2.1. System Description

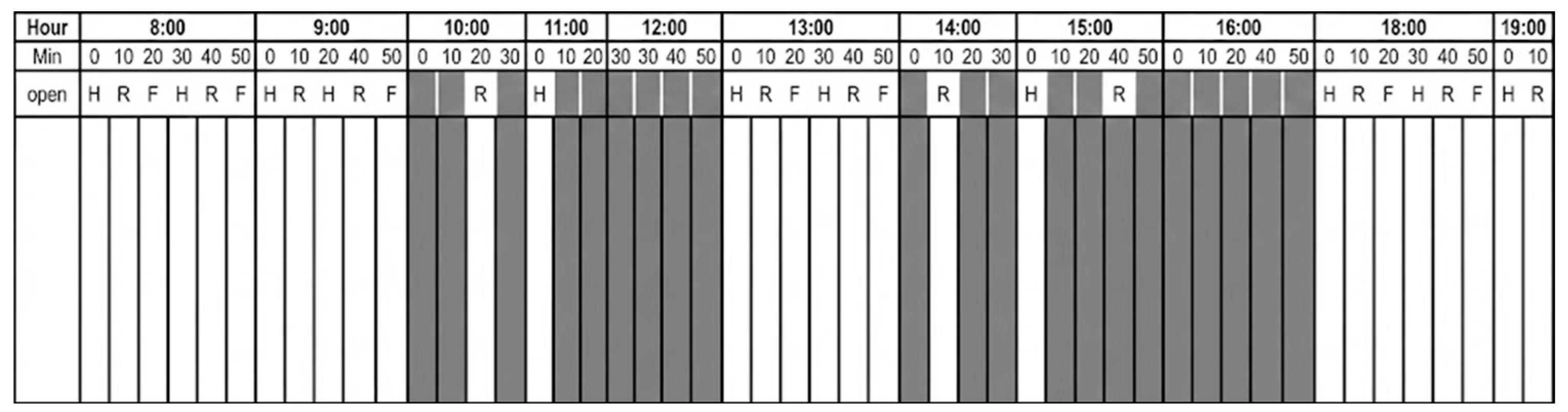

2.2. Experimental Setup

- (i)

- Short repetitive disturbances (08:00–10:00, 13:00–14:00, 18:00–19:10): Frequent door openings introduce repeated thermal shocks, providing insight into the sensitivity and responsiveness of each controller.

- (ii)

- Mixed disturbance region (10:00–12:00, 15:00–16:00): Occasional door openings separated by longer idle periods create alternating transient and steady-state conditions.

- (iii)

- Long undisturbed interval (12:00–13:00, 16:00–17:00): Extended continuous operation without door activity allows analysis of steady-state temperature regulation and energy efficiency.

2.3. Mathematical Formulation

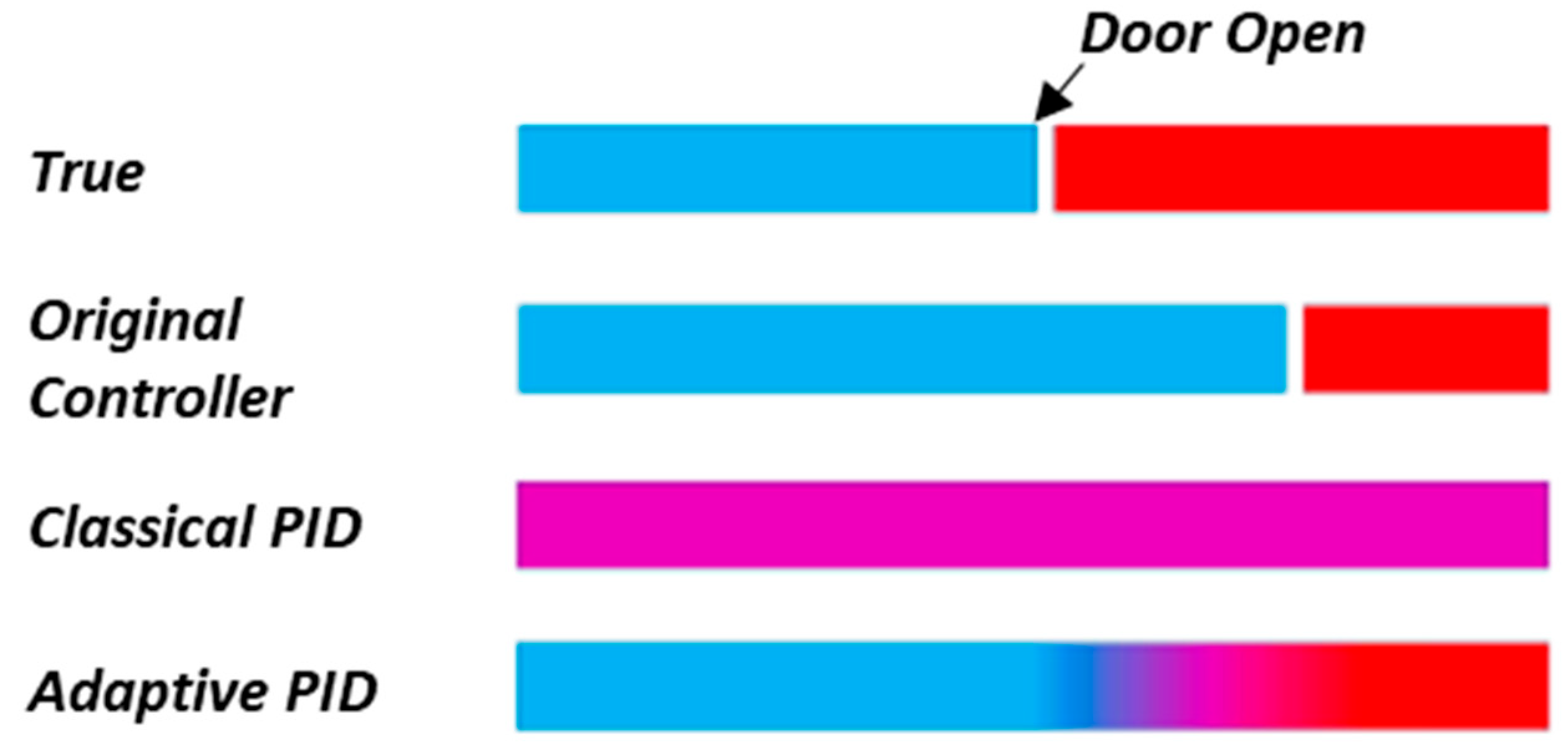

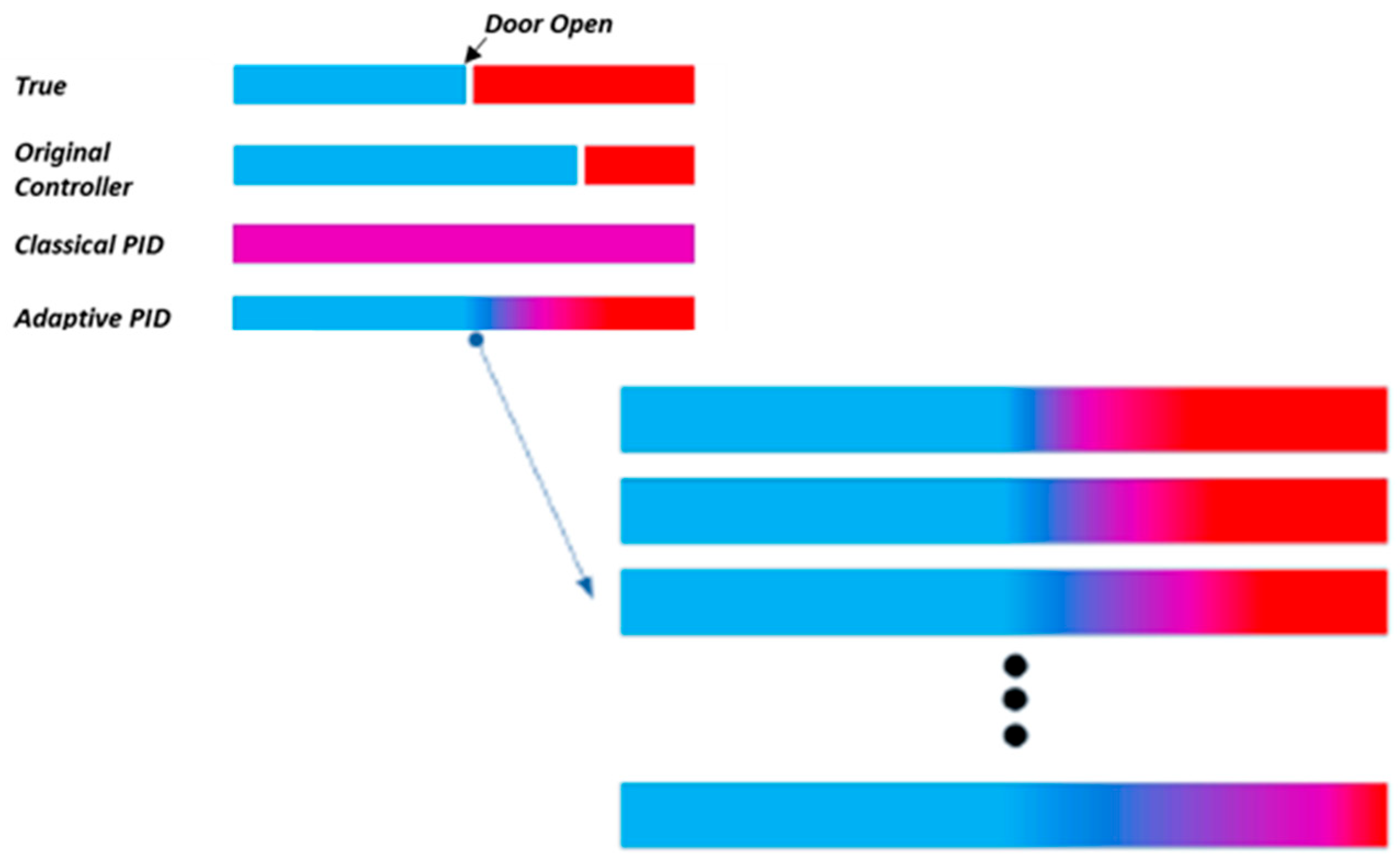

2.3.1. Motivation for Adaptive PID

2.3.2. Composite Error Definition

- : fresh-food compartment temperature,

- : freezer temperature,

- : respective setpoints,

- λ: weighting parameter controlling the contribution of freezer temperature.

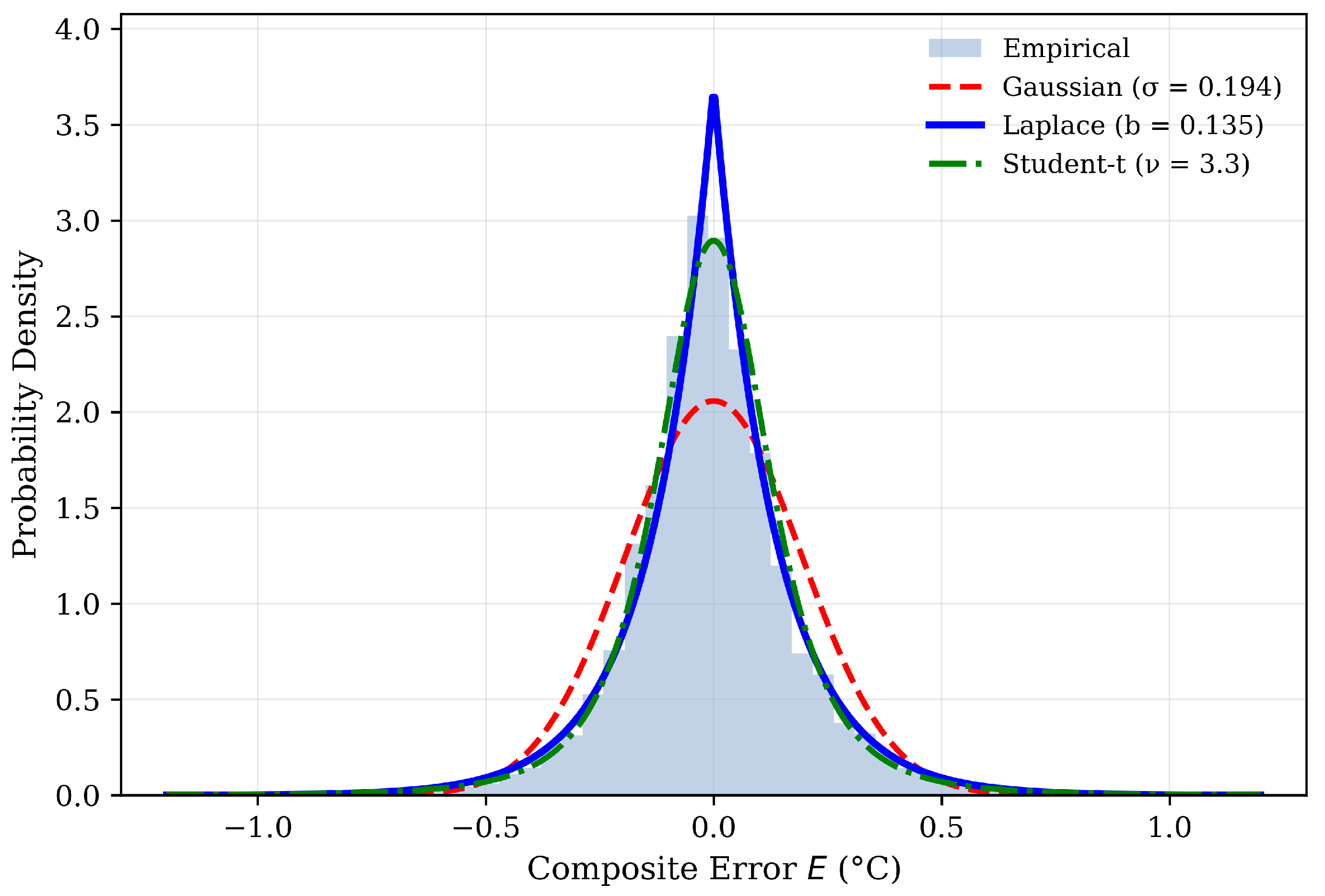

2.3.3. Error Distribution Estimation

- It naturally captures the heavy-tailed behavior that arises from sudden thermal disturbances.

- Its probability density function has a simple analytic form, enabling closed-form gain computation.

- It allows efficient inverse-PDF evaluation, which is essential for low-computation embedded systems.

2.3.4. Laplace-Distribution-Based Gain Scaling

- When ∣e(t)∣ is small (steady state), L(t) is small, producing smooth and energy-efficient control.

- When ∣e(t)∣ becomes large (door opening or abrupt load change), L(t) decreases sharply, indicating that the corresponding error is statistically rare and lies in a low-probability region of the Laplace distribution.

2.3.5. Effect of the Scale Parameter b

2.3.6. Adaptive PID Control Law

- Kp, Ki, Kd: proportional, integral, and derivative gains,

- L(t): adaptive gain scaling based on the error distribution,

- e(t): composite temperature error.

3. Results and Discussions

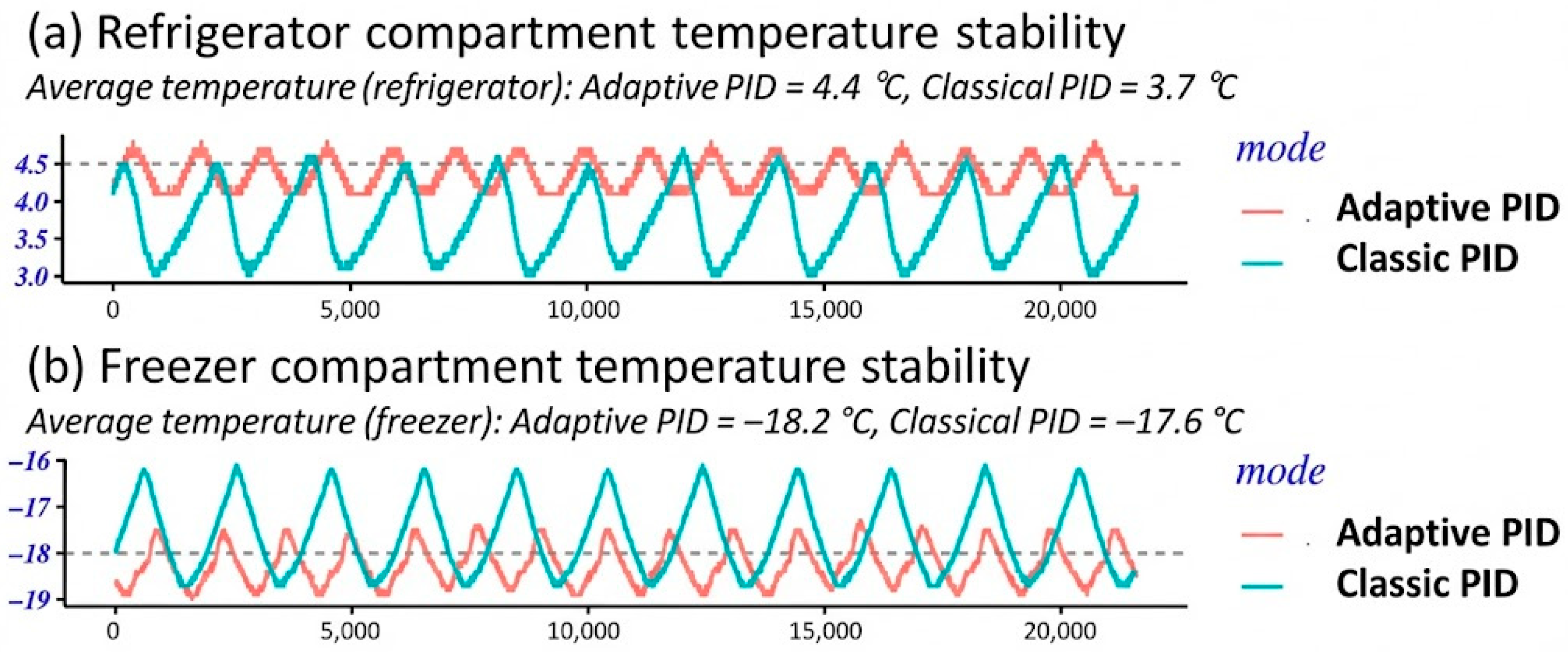

3.1. Temperature Stability in the Refrigerator and Freezer Compartments

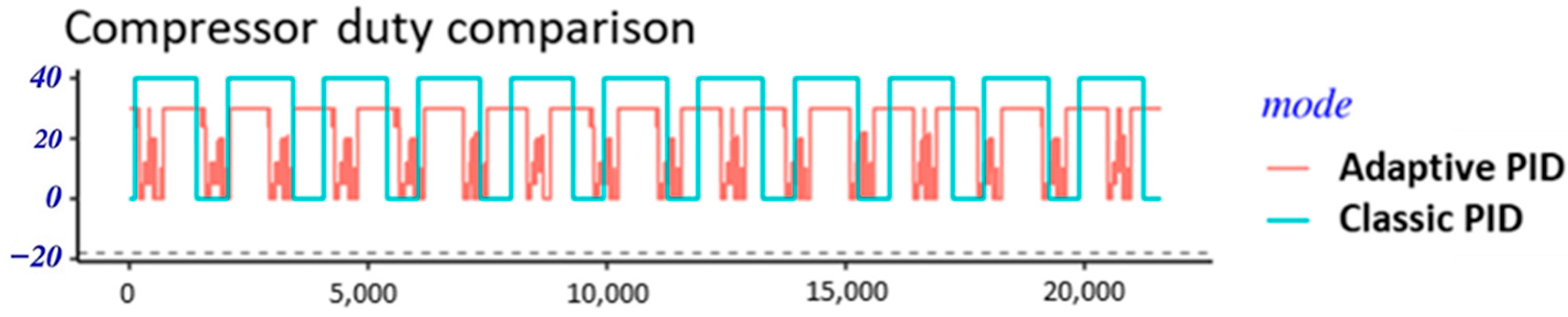

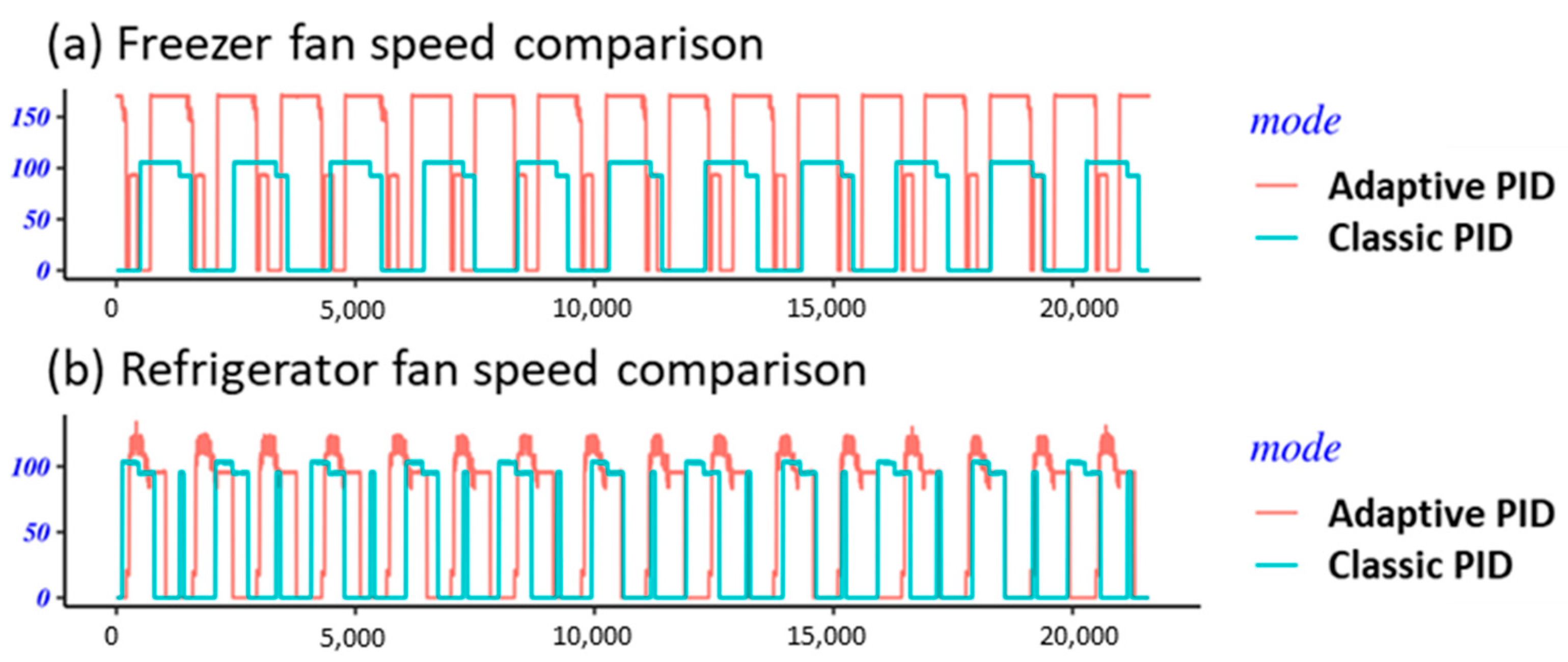

3.2. Compressor Duty and Fan Speed Behavior

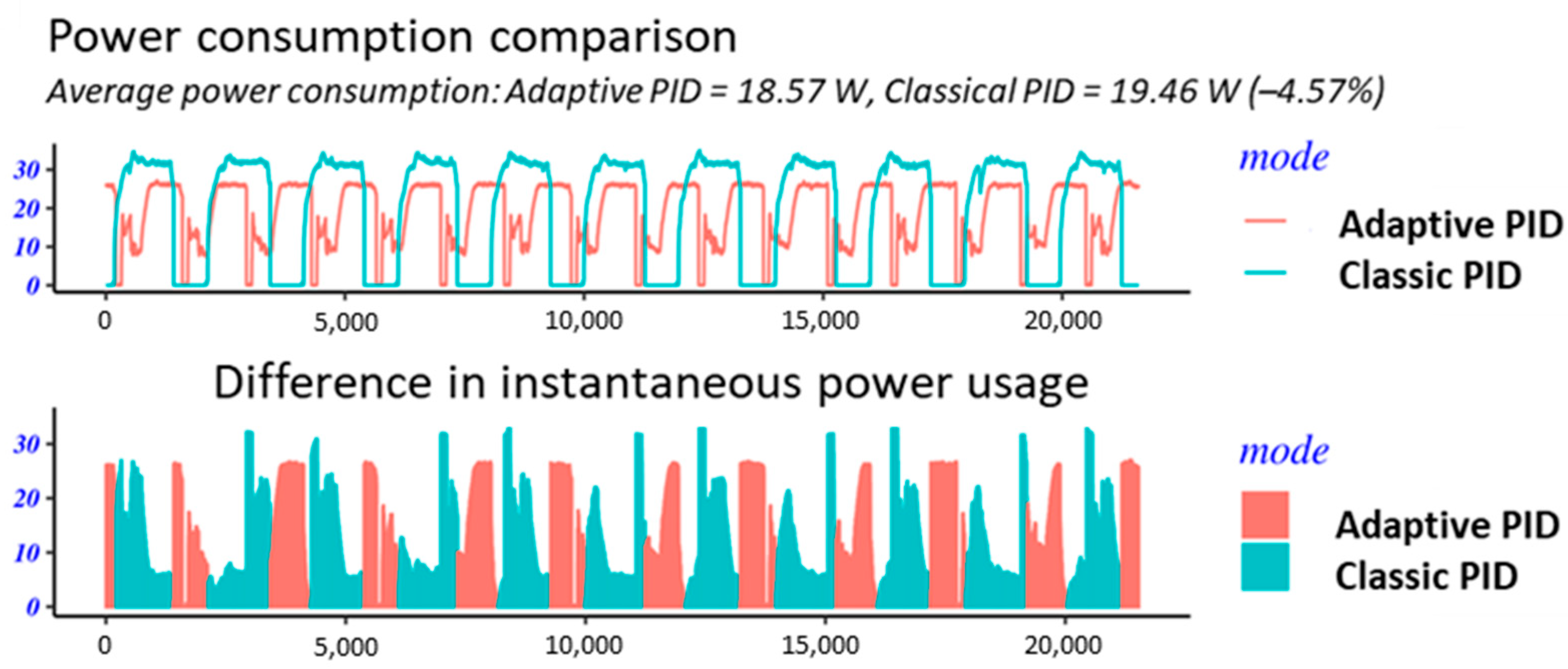

3.3. Energy Consumption Analysis

3.4. Summary of Selected Performance Metrics

3.5. Discussions

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Åström, K.J.; Hägglund, T. PID Controllers: Theory, Design, and Tuning; ISA—The Instrumentation, Systems and Automation Society: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Åström, K.J.; Murray, R.M. Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dwyer, A. Handbook of PI and PID Controller Tuning Rules, 3rd ed.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, A.S.; Souza, G.A.; Liston, R.J.; Hermes, C.J.L. Sensorless Temperature Control of Household Refrigerators Based on the Electric Current of the Compressor. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 152, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurt, L.C.; Hermes, C.J.L.; Neto, A.T. A Model-Driven Multivariable Controller for Vapor Compression Refrigeration Systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2009, 32, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.A.; Foster, A.M.; Brown, T. Temperature Control in Domestic Refrigerators and Freezers. In Proceedings of the 3rd IIR International Conference on Sustainability and the Cold Chain, London, UK, 23–25 June 2014; International Institute of Refrigeration: Twickenham, UK, 2014; p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Shinskey, F.G. Process Control Systems: Application, Design, and Tuning, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.-C. A New Tuning Method for PID Controllers. ISA Trans. 2002, 41, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killian, M.; Kozek, M. Ten Questions Concerning Model Predictive Control for Energy Efficient Buildings. Build. Environ. 2016, 105, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afram, A.; Janabi-Sharifi, F. Theory and Applications of HVAC Control Systems—A Review of Model Predictive Control (MPC). Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mattia, E.; Gambarotta, A.; Marzi, E.; Morini, M.; Saletti, C. Predictive Controller for Refrigeration Systems Aimed to Electrical Load Shifting and Energy Storage. Energies 2022, 15, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyguder, S.; Alli, H. Design and Simulation of Self-Tuning PID-Type Fuzzy Adaptive Control for an Expert HVAC System. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 4566–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gu, D.-W.; Ball, J.E. Self-Tuning PID Temperature Controller Based on Flexible Neural Network. In Advances in Neural Networks—ISNN 2007; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 4491, pp. 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Li, H.; Li, S. Fuzzy Immune PID Temperature Control of HVAC Systems. In Advances in Neural Networks—ISNN 2009; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5552, pp. 1059–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Guesmi, K.; Essounbouli, N.; Hamzaoui, A. Systematic Design Approach of Fuzzy PID Stabilizer for DC–DC Converters. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 2880–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.J.; Wittenmark, B. On Self-Tuning Regulators. Automatica 1973, 9, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, T.; Jezernik, K. Parametric and Nonparametric PID Controller Tuning for Integrating Processes. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, I.D.; Lozano, R.; M’Saad, M.; Karimi, A. Adaptive Control: Algorithms, Analysis and Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Åström, K.J.; Wittenmark, B. Adaptive Control, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.W. Multivariate Density Estimation: Theory, Practice, and Visualization; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, P.R.; Lennox, B.; Chen, Q.; Sandoz, D.J. Robust Inferential Control Using Kernel Density Methods. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2000, 24, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, S.; Kozubowski, T.J.; Podgórski, K. The Laplace Distribution and Generalizations: A Revisit with Applications to Communications, Economics, Engineering, and Finance; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eltoft, T.; Kim, T.; Lee, T.-W. On the Multivariate Laplace Distribution. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2006, 13, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Component/Feature | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cabinet Structure | Total volume | 727 L |

| Compartment layout | Fresh-food (top), Freezer (bottom) | |

| Drawers/Shelves | 2 drawers, multi-shelf airflow design | |

| Cooling System | Compressor type | Linear inverter compressor |

| Refrigeration cycle | Vapor compression with wire-and-tube condenser and no-frost evaporator | |

| Expansion device | Capillary tube with suction-line heat exchanger | |

| Airflow System | Fan | Single-speed centrifugal fan (freezer compartment) |

| Air distribution | Multi-airflow ducts supplying both compartments | |

| Damper | Electronic damper for fresh-food temperature regulation | |

| Electronics and Control | Temperature sensing | Multi-point thermocouple array installed for experiments |

| Fast freeze mode | Supported | |

| Hygiene Fresh | Air purification module enabled | |

| Physical Dimensions | Size (W × H × D) | 902 × 1785 × 920 mm |

| Distribution | Scale Parameter | AIC | BIC | KS Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | σ = 0.1938 | −1771.9 | −1765.6 | 0.0757 |

| Laplace | b = 0.1348 | −2482.2 | −2475.9 | 0.0384 |

| Student-t | s = 0.1278 | −2518.6 | −2506.0 | 0.0270 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yoo, M. Adaptive PID Control Based on Laplace Distribution for Multi-Environment Temperature Regulation in Smart Refrigeration Systems. Energies 2026, 19, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020477

Yoo M. Adaptive PID Control Based on Laplace Distribution for Multi-Environment Temperature Regulation in Smart Refrigeration Systems. Energies. 2026; 19(2):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020477

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoo, Mooyoung. 2026. "Adaptive PID Control Based on Laplace Distribution for Multi-Environment Temperature Regulation in Smart Refrigeration Systems" Energies 19, no. 2: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020477

APA StyleYoo, M. (2026). Adaptive PID Control Based on Laplace Distribution for Multi-Environment Temperature Regulation in Smart Refrigeration Systems. Energies, 19(2), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020477