Challenges in the Legal and Technical Integration of Photovoltaics in Multi-Family Buildings in the Polish Energy Grid

Abstract

1. Introduction

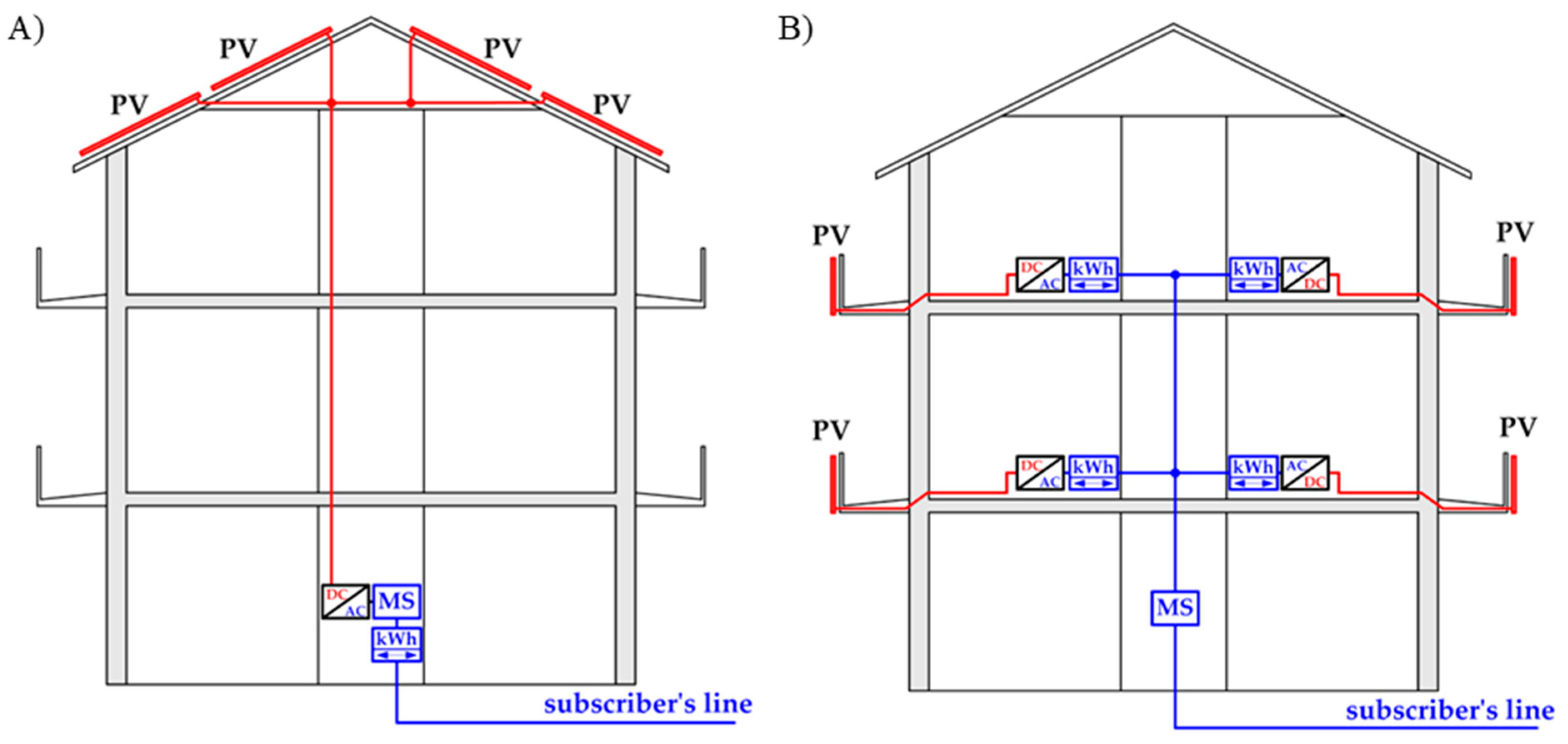

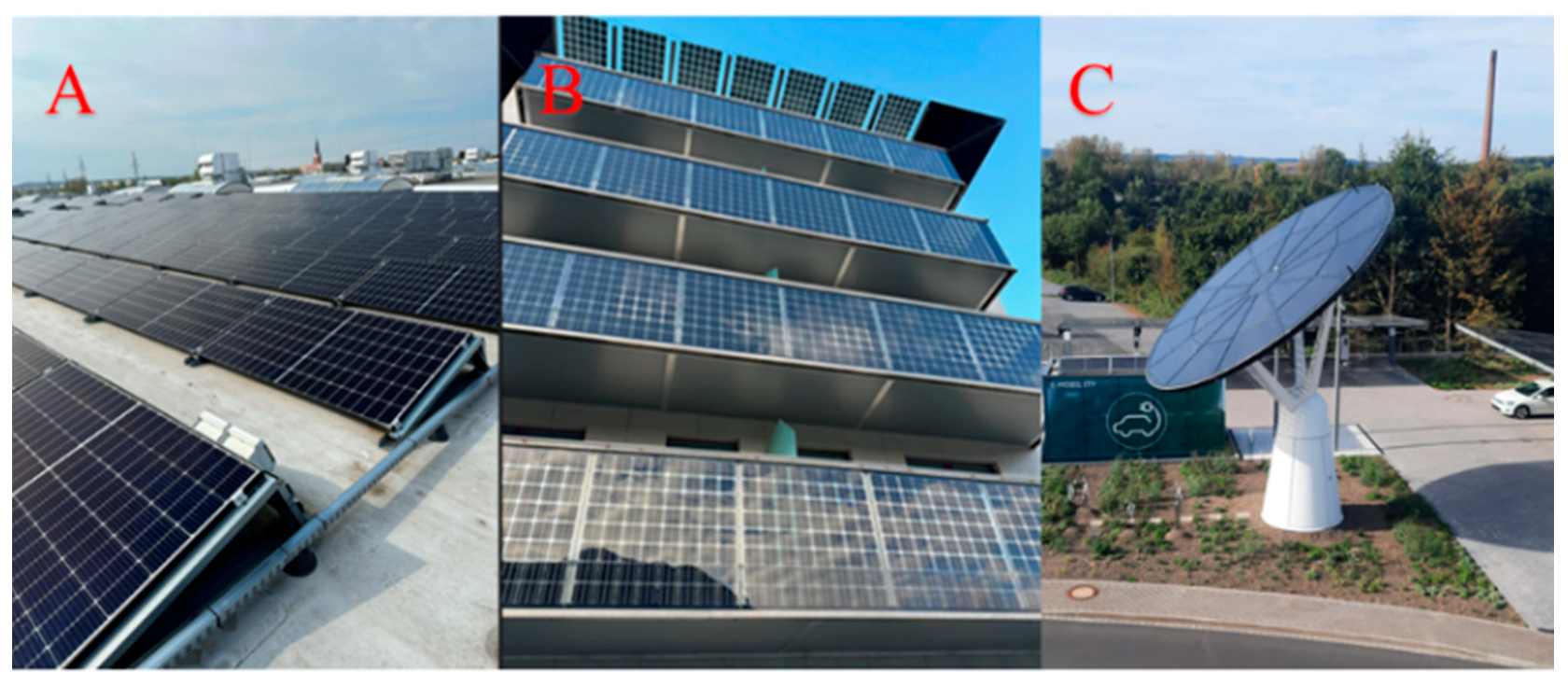

2. Design PV Installations on Multi-Family Buildings

2.1. Technical Challenges

2.2. Safety Issues

2.3. Legal Regulations in Poland

3. Methodology and Experimental Details

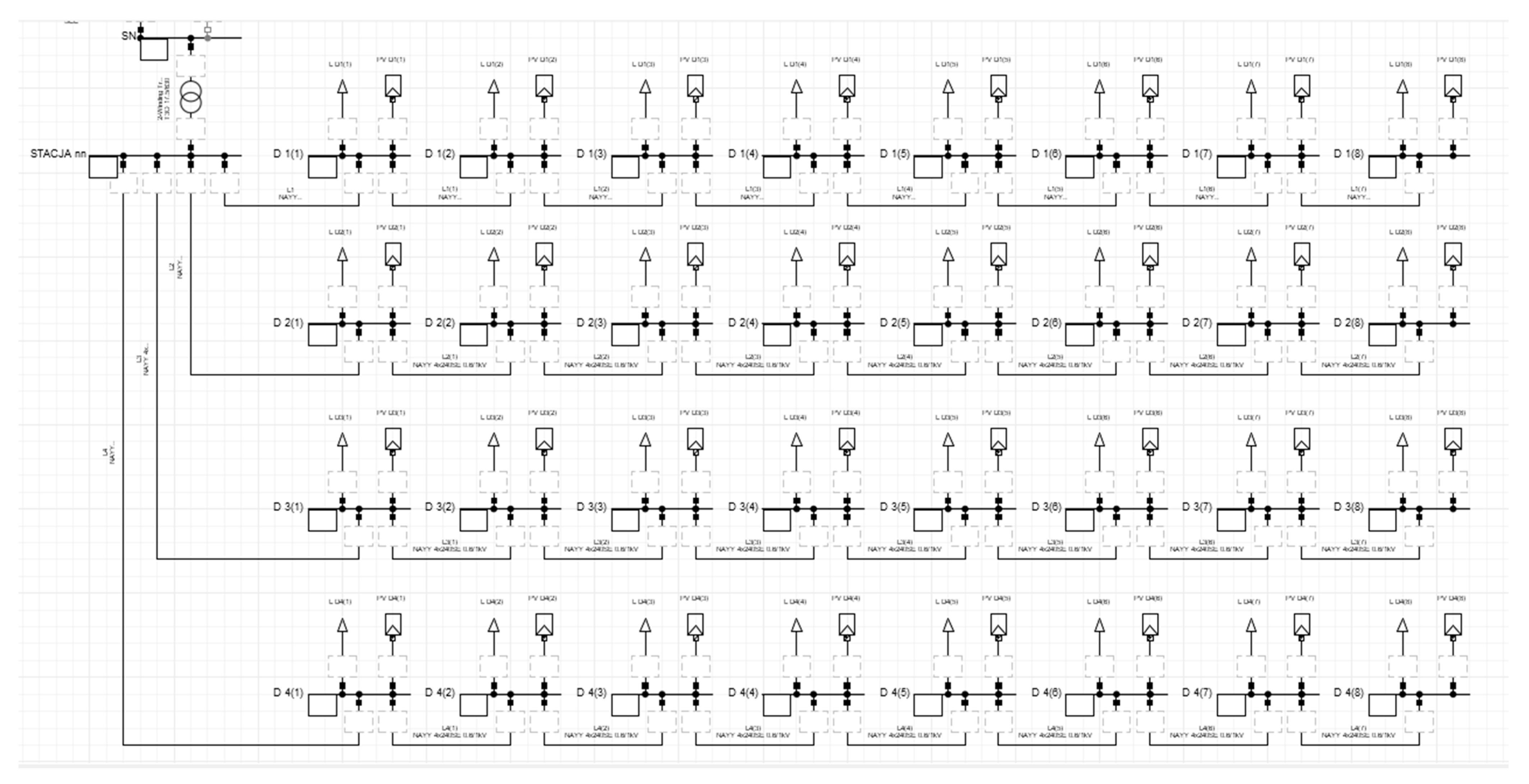

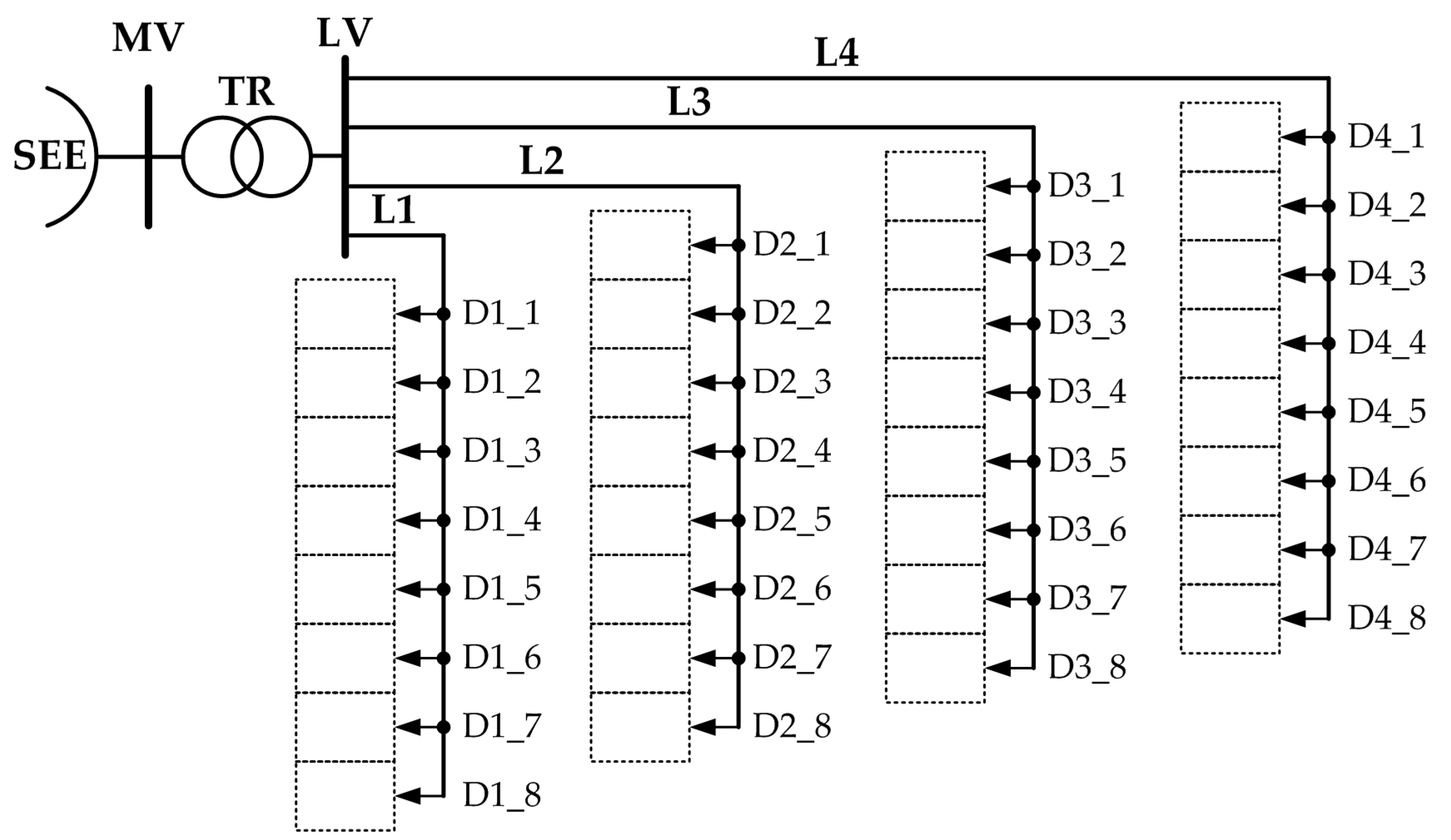

3.1. Research Object

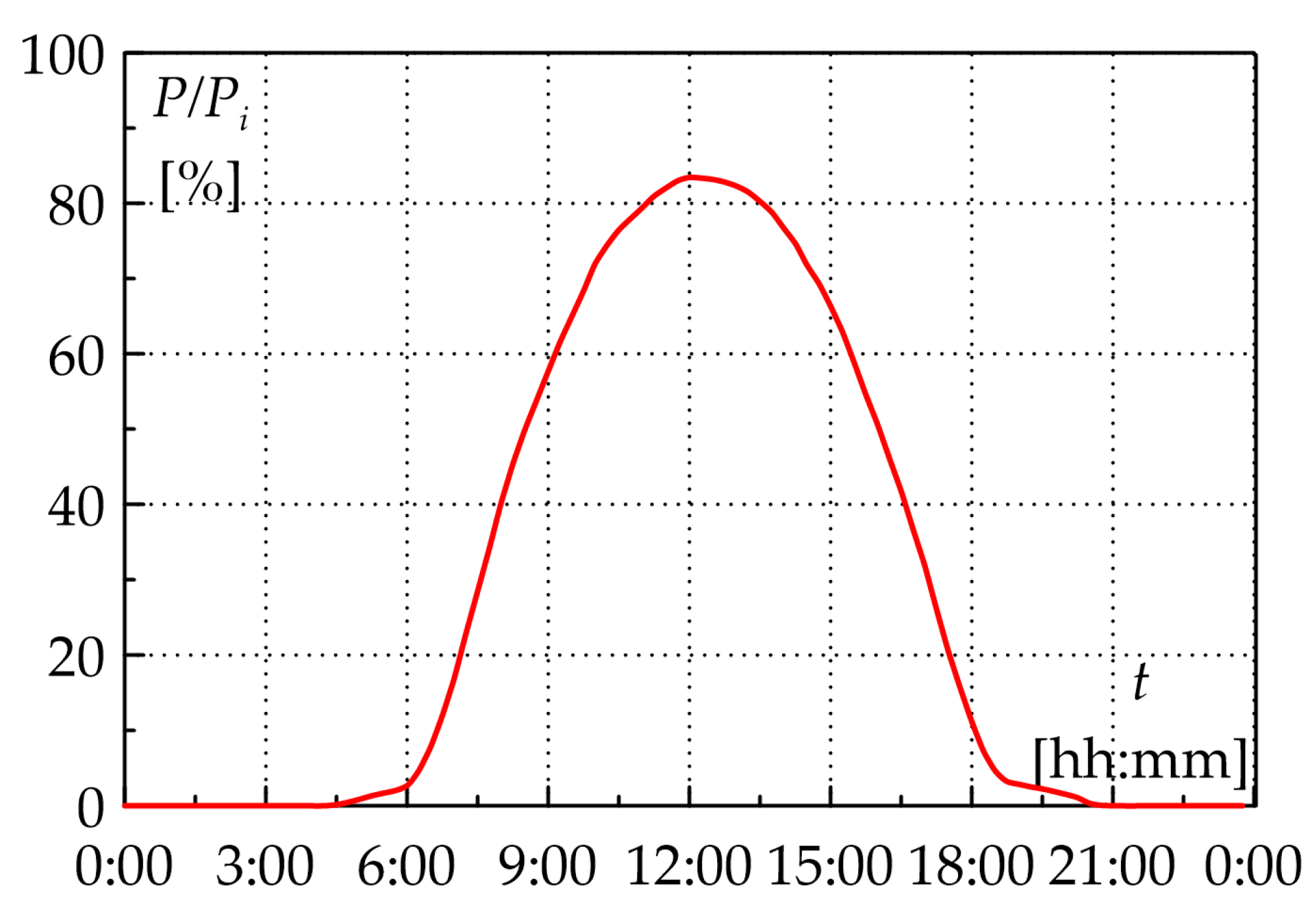

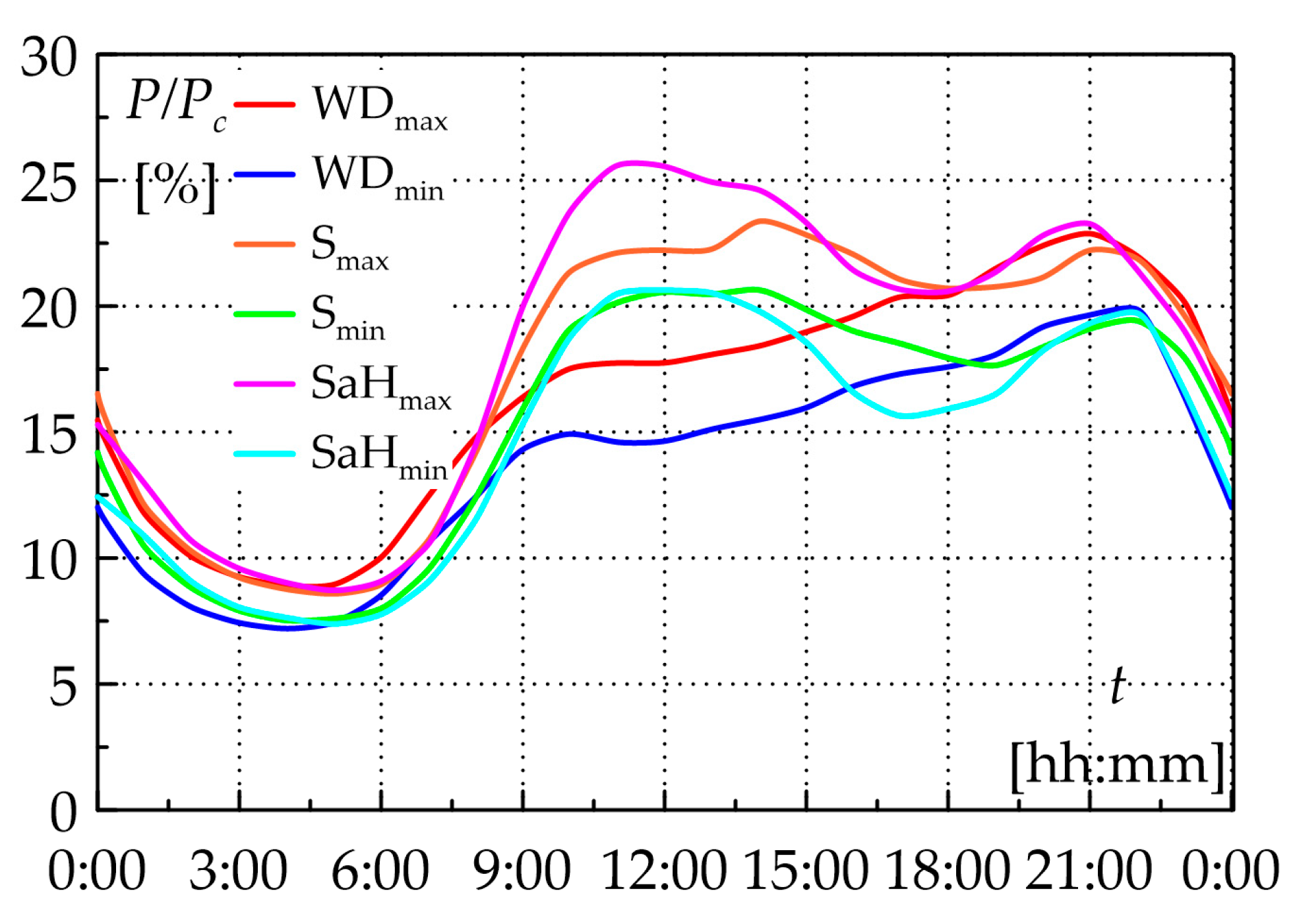

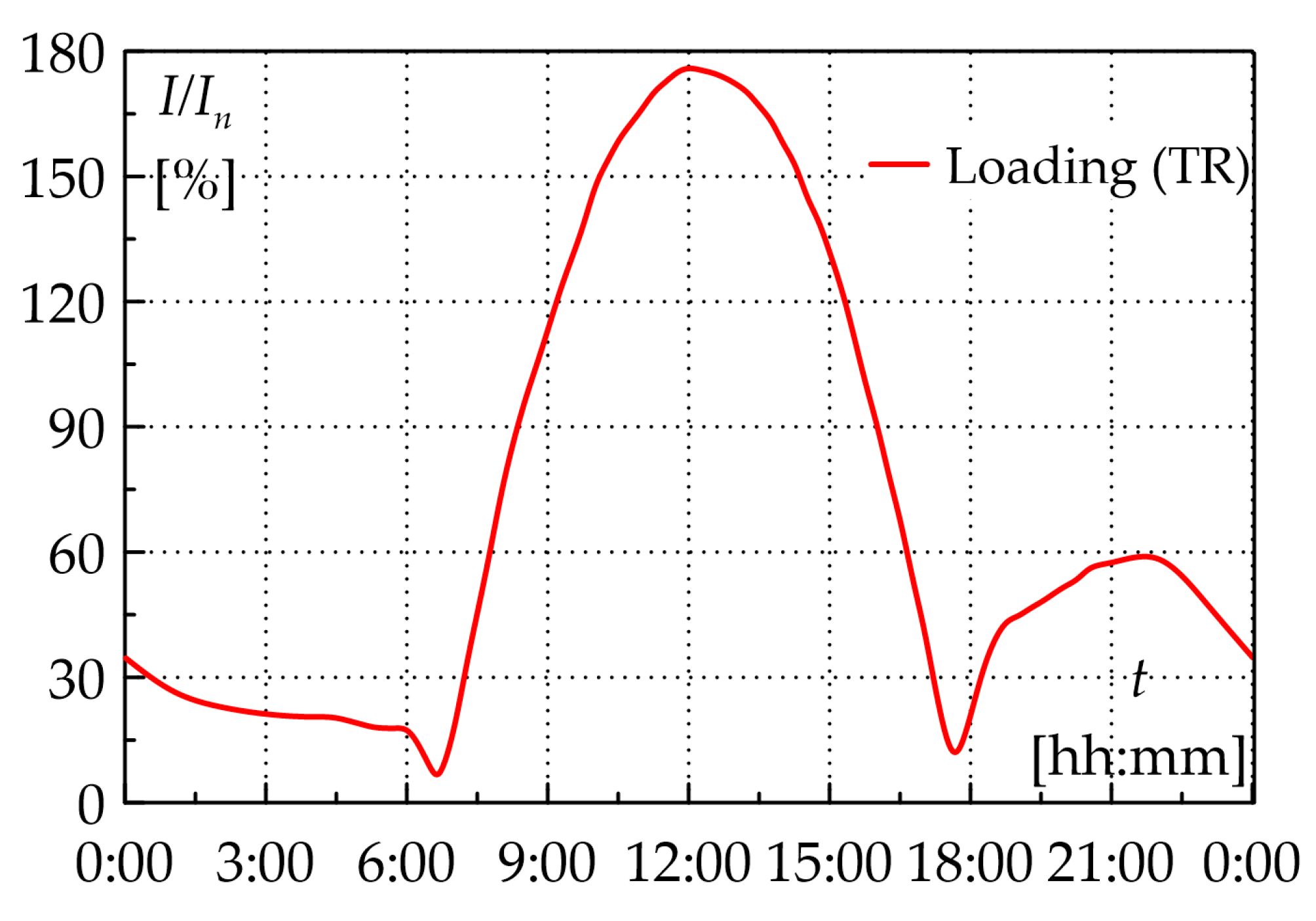

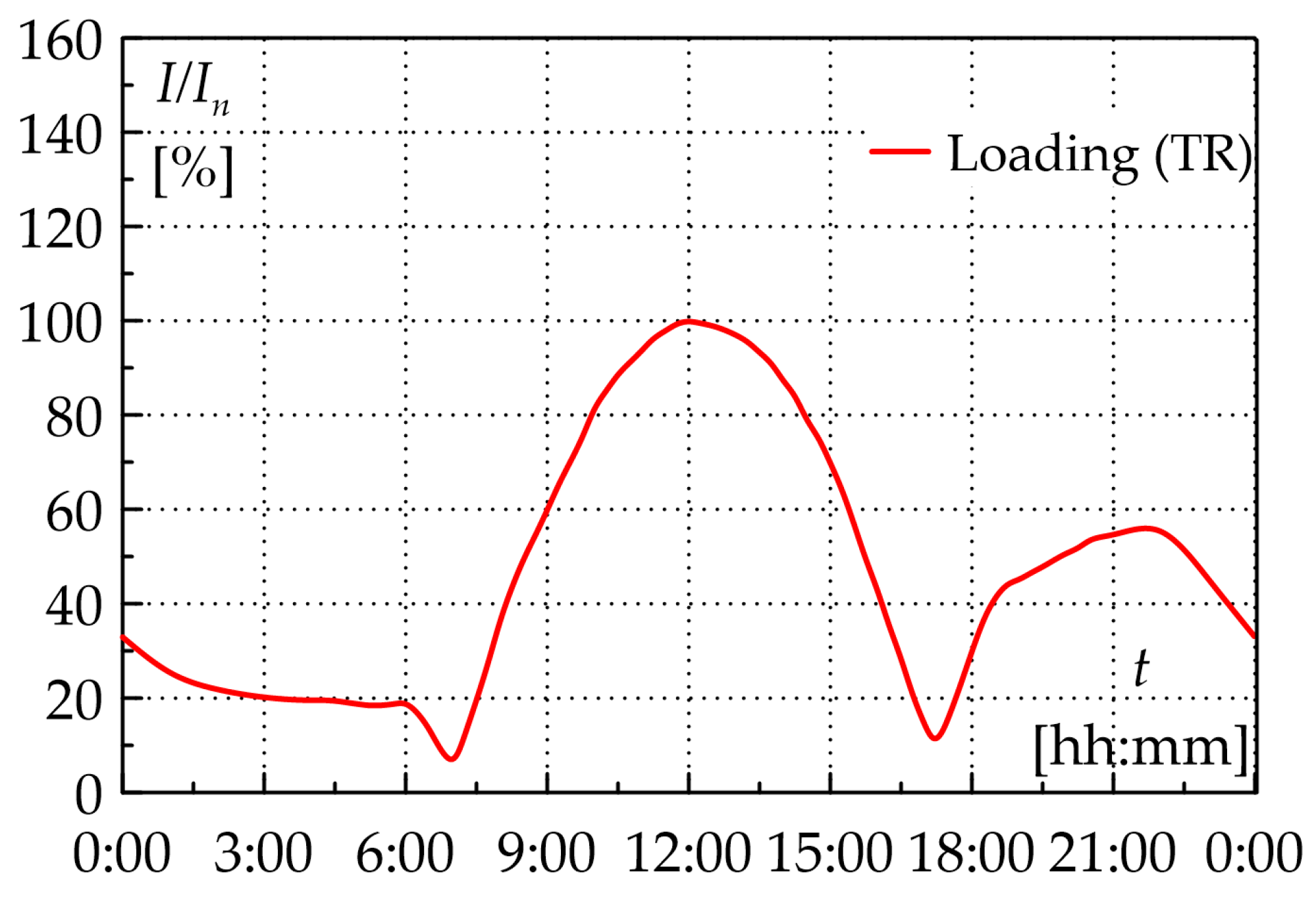

3.2. Characteristics of PV Generation and Power Demand of Electricity Consumers

3.3. Computer Model

3.4. Presented Research Variants

- Variant I—No photovoltaic installations in the estate, minimum and maximum power consumption by consumers.

- Variant II—Operation of photovoltaic installations in all buildings of the estate with the total power installed in a single building equal to the building’s connection power of 36 kW, minimum power consumption by consumers.

- Variant III—Operation of photovoltaic installations in all buildings of the estate with the total power installed in a single building equal to the sum of the connection power of individual apartments in the building, which gives the value of the power installed in the building amounting to 50 kW (12.5 kW × 4 apartments in the building); consumption power by consumers is minimal.

4. Results and Discussion

- i—i-th node of the network.

- Umax—maximum voltage value determined for the node during the day.

- Umin—minimum voltage value determined for the node during the day.

- Umax—the maximum voltage value occurring in the network nodes during the day.

- Umin—the minimum voltage value occurring in the network nodes during the day.

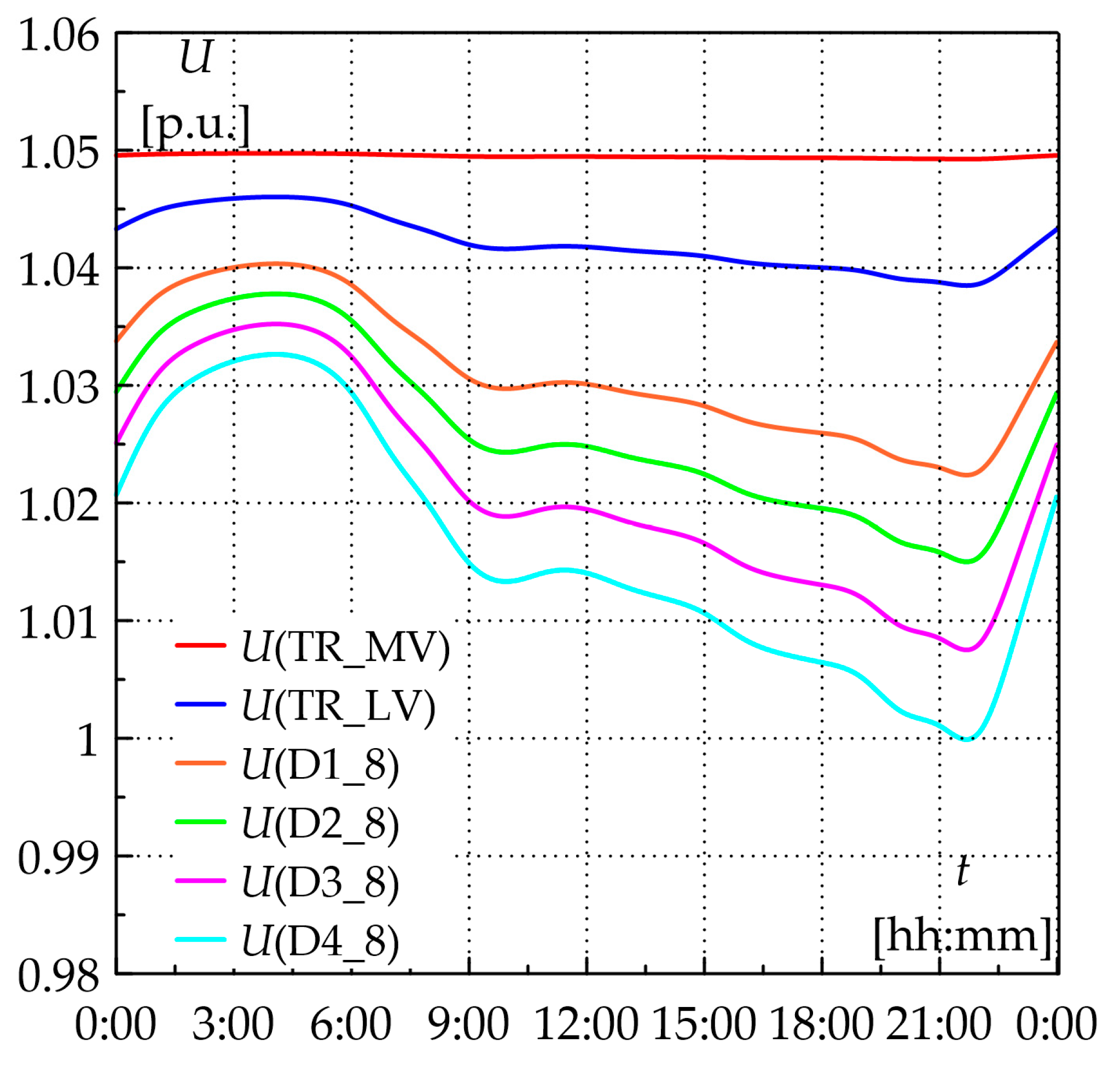

4.1. Variant I

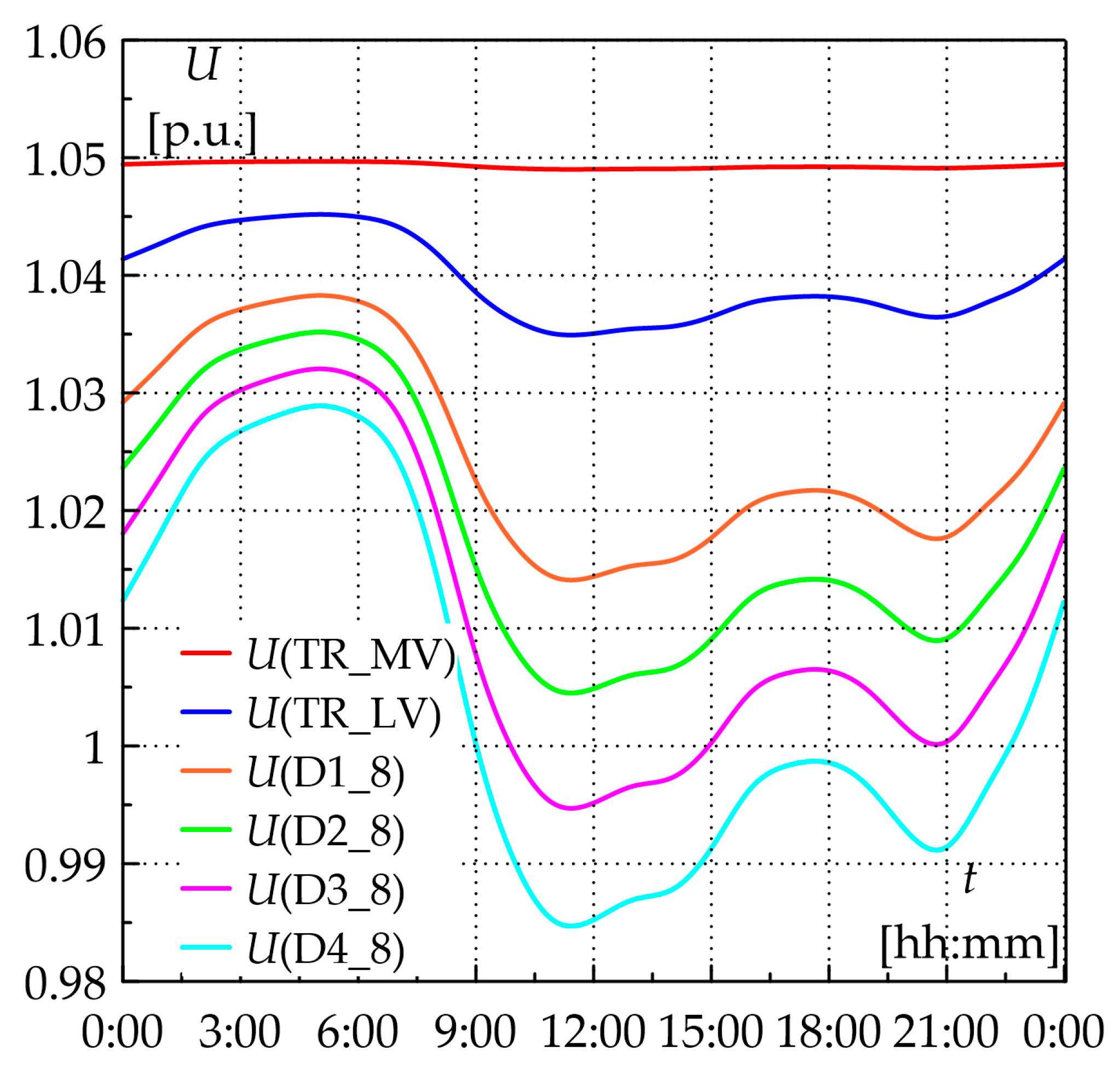

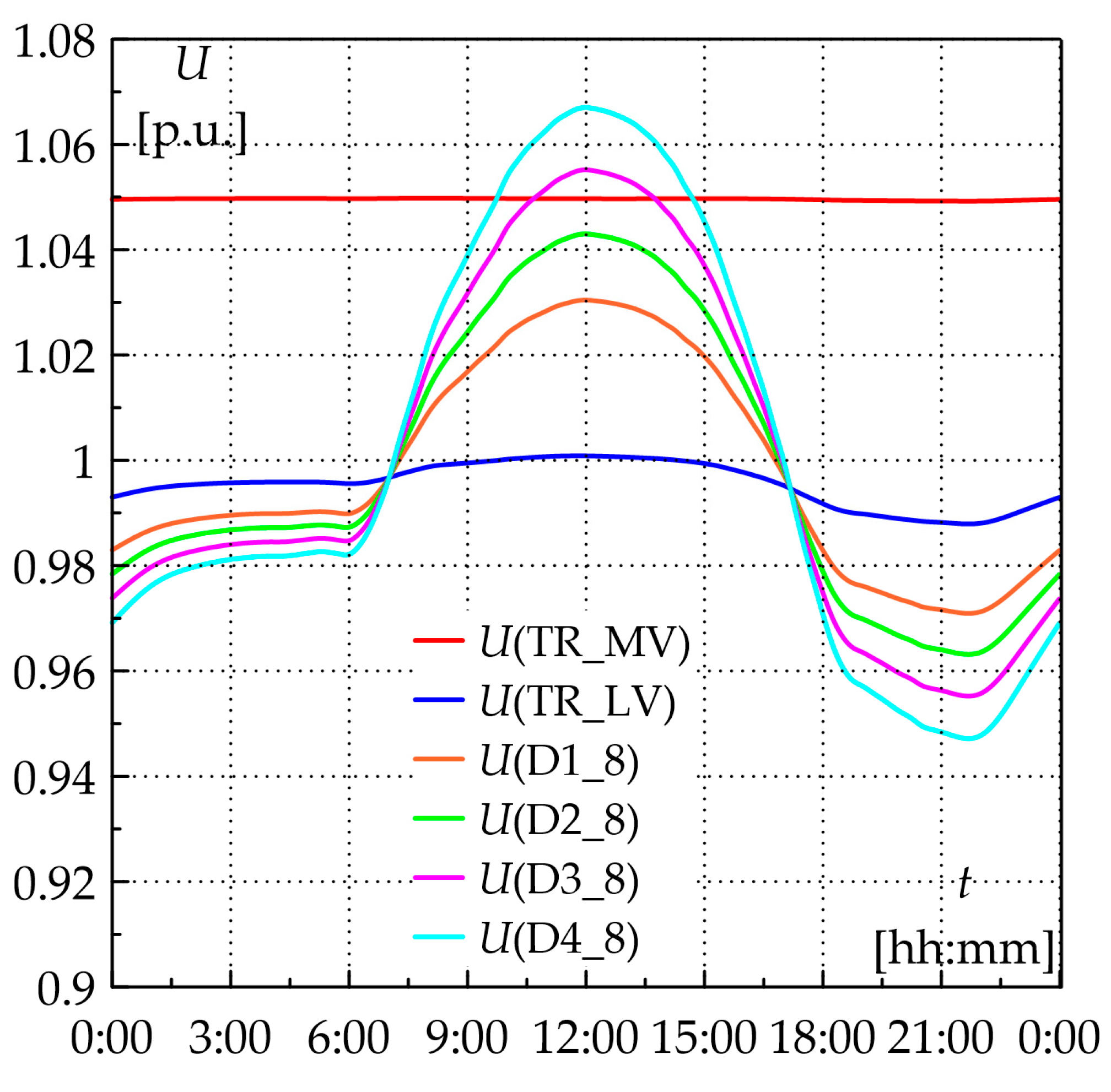

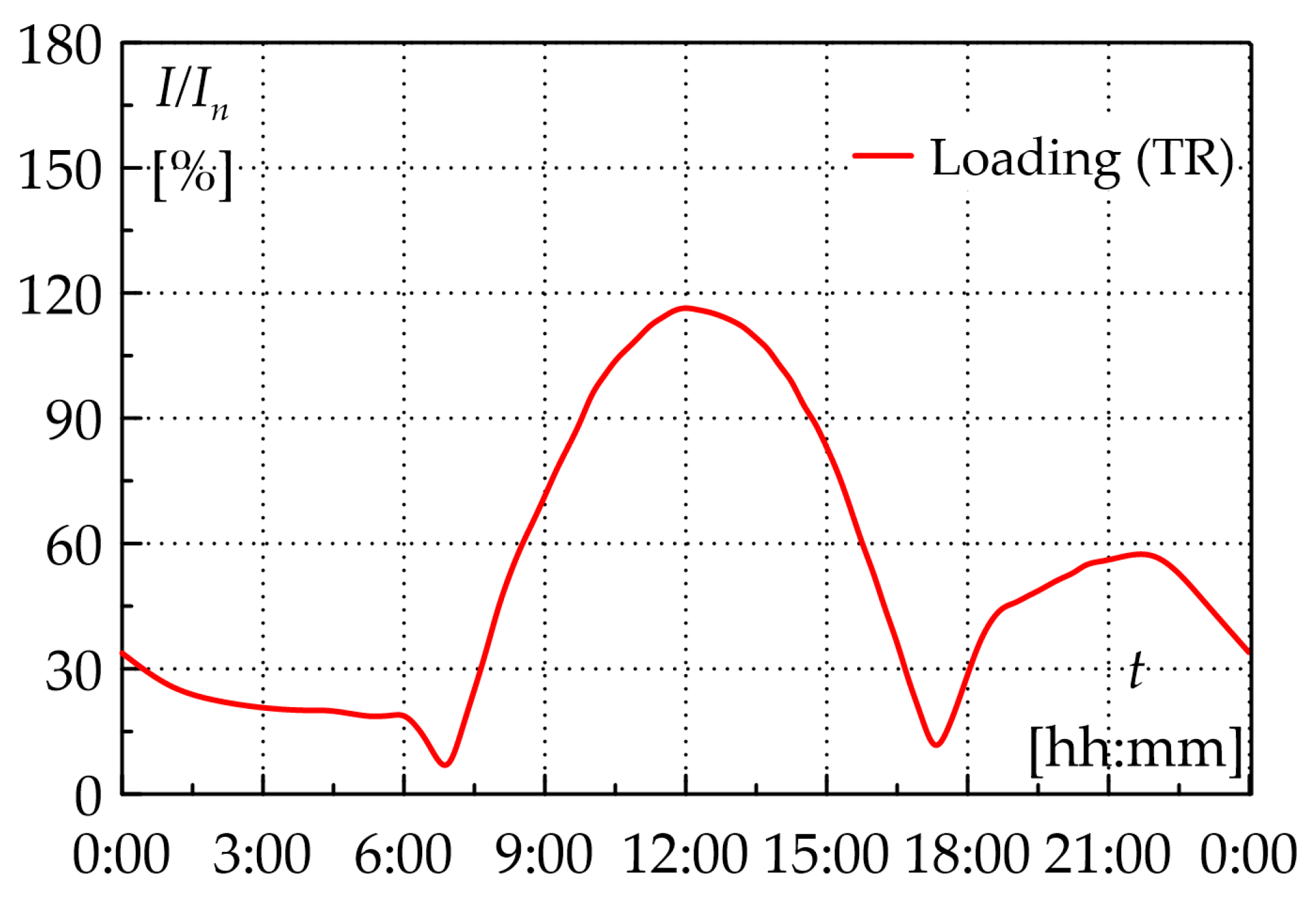

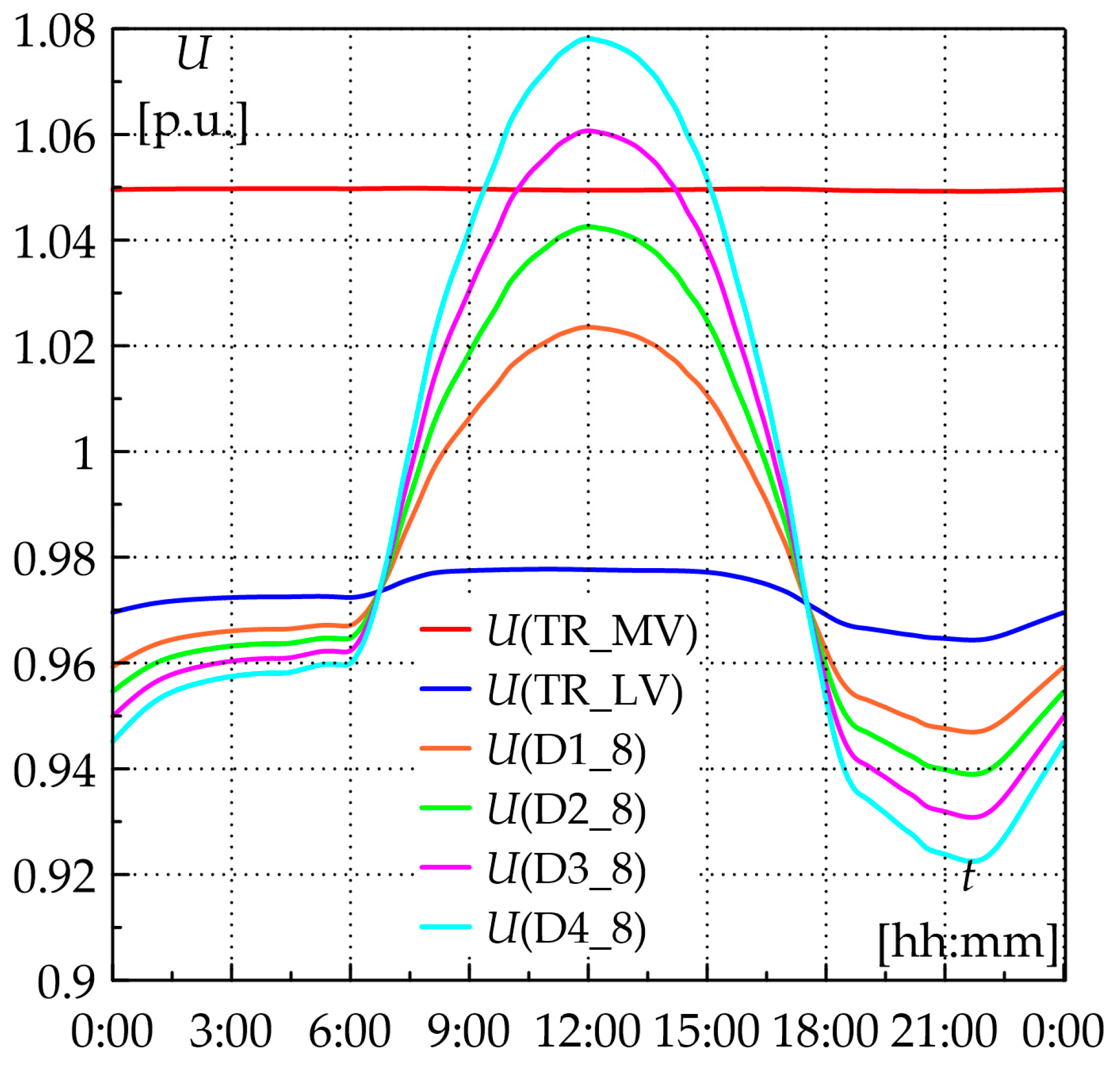

4.2. Variant II

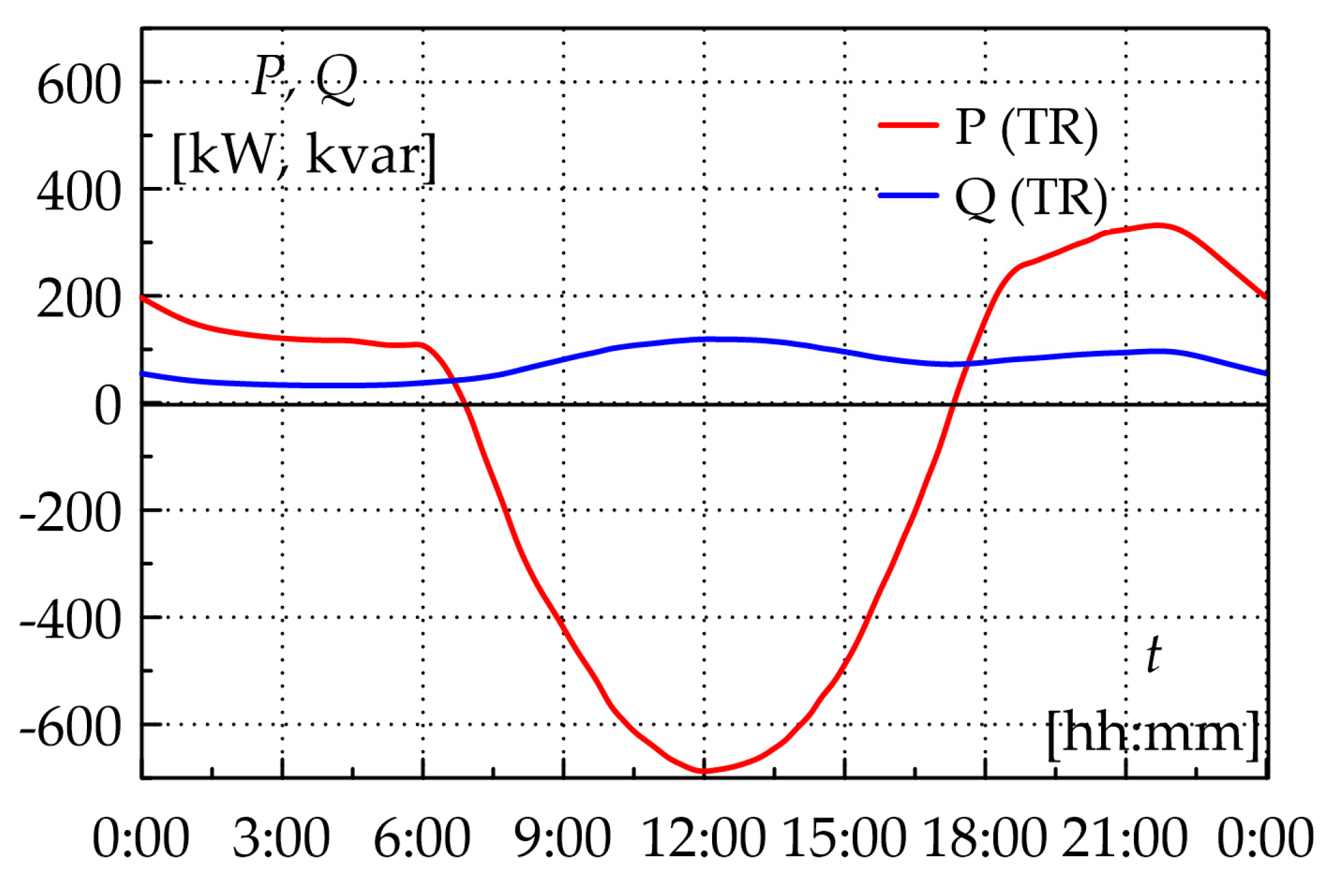

4.3. Variant III

4.4. Discussion of the Obtained Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

References

- Cader, J.; Olczak, P.; Koneczna, R. Regional dependencies of interest in the ‘My Electricity’ photovoltaic subsidy program in Poland. Polityka Energetyczna—Energy Policy J. 2021, 24, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paska, J.; Surma, T.; Terlikowski, P.; Zagrajek, K. Electricity Generation from Renewable Energy Sources in Poland as a Part of Commitment to the Polish and EU Energy Policy. Energies 2020, 13, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V.V.; Rahim, N.A.A.; Rahim, N.A.; Jeyraj, A.; Selvaraj, L. Progress in solar PV technology: Research and achievement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 20, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, B.; Mularczyk, A. PESTEL Analysis of the Photovoltaic Market in Poland—A Systematic Review of Opportunities and Threats. Resources 2024, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulkowski, S.; Krawczak, E. Long-Term Energy Yield Analysis of the Rooftop PV System in Climate Conditions of Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumo, F.; Pennacchia, E.; Zylka, C. Energy-Efficient Solutions: A Multi-Criteria Decision Aid Tool to Achieve the Targets of the European EPDB Directive. Energies 2023, 16, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Kowalska-Koczwara, A.; Kozak, E.; Pachla, F.; Szuminski, J.; Tatara, T. Energy and Cost Analysis of Adapting a New Building to the Standard of the NZEB. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 112076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, M.; Sikorski, T.; Kostyła, P.; Kaczorowska, D.; Leonowicz, Z.; Rezmer, J.; Szymańda, J.; Janik, P.; Bejmert, D.; Rybiański, M.; et al. Influence of Measurement Aggregation Algorithms on Power Quality Assessment and Correlation Analysis in Electrical Power Network with PV Power Plant. Energies 2019, 12, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnberg, S.; Bollen, M.; Larsson, A. Grid impact from PV-installations in Northern Scandinavia. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference and Exhibition on Electricity Distribution (CIRED 2013), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–13 June 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElNozahy, M.S.; Salama, M.M.A. Technical impacts of grid-connected photovoltaic systems on electrical networks—A review. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2013, 5, 32702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaigwe, K.N.; Mutabilwa, P.; Dintwa, E. An overview of solar power (PV systems) integration into electricity grids. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2019, 2, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, R.; Hax, G.T.; Freitas, W.; Nassif, A. Impact Assessment of High-Frequency Distortions Produced by PV Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 2978–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knenicky, M.; Prochazka, R.; Hlavacek, J.; Sefl, O. Impact of High-Frequency Voltage Distortion Emitted by Large Photovoltaic Power Plant on Medium Voltage Cable Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 1882–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, N.; Usman, M.; Jawad, M.; Zafar, M.H.; Iqbal, M.N.; Kütt, L. Economic analysis and impact on national grid by domestic photovoltaic system installations in Pakistan. Renew Energy 2020, 153, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, R.; Fujii, Y. Optimal integration assessment of solar PV in Japan’s electric power grid. Renew Energy 2019, 139, 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchakour, S.; Arab, A.H.; Abdeladim, K.; Amrouche, S.O.; Semaoui, S.; Taghezouit, B.; Boulahchiche, S.; Razagui, A. Investigation of the voltage quality at PCC of grid connected PV system. Energy Procedia 2017, 141, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komendantova, N.; Schwarz, M.M.; Amann, W. Economic and regulatory feasibility of solar PV in the Austrian multi-apartment housing sector. AIMS Energy 2018, 6, 810–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, Ö.; Gotchev, B.; Holstenkamp, L.; Müller, J.R.; Radtke, J.; Welle, L. Consumer (Co-) ownership in renewables in Germany. In Energy Transition: Financing Consumer Co-Ownership in Renewables; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 271–293. [Google Scholar]

- Braeuer, F.; Kleinebrahm, M.; Naber, E. Effects of the tenants electricity law on energy system layout and landlord-tenant relationship in a multi-family building in Germany. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; p. 12168. [Google Scholar]

- Kisiel, E. Solar Panels in Condominium Communities. LSU J. Energy L. Resour. 2019, 8, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, G.K. An Exploration of Solar Access: How Can Tenants Benefit from Solar Financing Policies? Kleinman Center for Energy Policy: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- AS4777.2; Inverter Requirements Standard. Australian Energy Market Operator: Melbourne, Australia, 2020.

- Roberts, M.B.; Bruce, A.; MacGill, I. Opportunities and barriers for photovoltaics on multi-unit residential buildings: Reviewing the Australian experience. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, C.; Chierici, M.; Franzò, S.; Causone, F. Economic Performance Analysis of Jointly Acting Renewable Self-Consumption: A Case Study on 109 Condominiums in an Italian Urban Area. Buildings 2025, 15, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, R. Public acceptance of residential photovoltaic installation: A case study in China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grycan, W.; Brusilowicz, B.; Kupaj, M. Photovoltaic farm impact on parameters of power quality and the current legislation. Sol. Energy 2018, 165, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, P.; Kosobudzki, G.; Schwarz, H. Influence of increasing numbers of RE-inverters on the power quality in the distribution grids: A PQ case study of a representative wind turbine and photovoltaic system. Front. Energy 2017, 11, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gała, M.; Jaderko, A. Assessment of the impact of photovoltaic system on the power quality in the distribution network. Prz. Elektrotech. 2018, 94, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, T.; Madani, H.; Zottl, A.; Sommerfeldt, N.; Zucker, G. Techno-economic analysis of combined heat pump and solar PV system for multi-family houses: An Austrian case study. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 36, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassar, A.A.A.; Cha, S.H. Feasibility assessment of adopting distributed solar photovoltaics and phase change materials in multifamily residential buildings. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarcanin, S.; Andresen, G.B. Grid integration of solar PV for multi-apartment buildings. Int. J. Sustain. Energy Plan. Manag. 2018, 17, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, F. 5—Photovoltaic (PV) balance of system components: Basics, performance. In The Performance of Photovoltaic (PV) Systems; Pearsall, N., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; pp. 135–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhere, N.G. Reliability of PV modules and balance-of-system components. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the Thirty-first IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 3–7 January 2005; pp. 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN IEC 61730-1:2018-06; Ocena Bezpieczeństwa Modułu Fotowoltaicznego (PV)—Część 1: Wymagania Dotyczące Konstrukcji. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 1–64.

- PN-EN 62109-1:2010; Bezpieczeństwo Konwerterów Mocy Stosowanych W Fotowoltaicznych Systemach Energetycznych—Część 1: Wymagania Ogólne. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 1–156.

- PN-HD 60364-8-2:2019-01; Instalacje Elektryczne Niskiego Napięcia—Część 8-2 Niskonapięciowe Instalacje Elektryczne Prosumenta. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; pp. 1–58.

- PN-HD 60364-7-712:2016-05; Instalacje Elektryczne Niskiego Napięcia—Część 7-712: Wymagania Dotyczące Specjalnych Instalacji Lub Lokalizacji—Fotowoltaiczne (PV) Układy Zasilania. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 1–30.

- Association of Polish Electrical Engineers (SEP). Electrical Installations in Buildings. Electrical Installations in Residential Buildings. Planning Basics; Bialystok University of Technology: Białystok, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 61730-1:2023; Photovoltaic (PV) Module Safety Qualification—Part 1: Requirements for Construction. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- IEC 60364; Low-Voltage Electrical Installations. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- IEC-62305-2:2024; Protection Against Lightning—Part 2: Risk Management. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Litzbarski, L.; Olesz, M.; Seklecki, K.; Nowak, M. Ryzyko strat odgromowych a systemy fotowoltaiczne. Prz. Elektrotech. 2023, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damianaki, K.; Christodoulou, C.A.; Kokalis, C.-C.A.; Kyritsis, A.; Ellinas, E.D.; Vita, V.; Gonos, I.F. Lightning Protection of Photovoltaic Systems: Computation of the Developed Potentials. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.I.; Ab-Kadir, M.; Izadi, M.; Azis, N.; Radzi, M.; Zaini, N.; Nasir, M. Lightning protection on photovoltaic systems: A review on current and recommended practices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzbarski, L.S.; Seklecki, K.; Adamowicz, M.; Grochowski, J. PV installations and the safety of residential buildings. Inżynieria Bezpieczeństwa Obiektów Antropog. 2023, Nr 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seklecki, K.; Olesz, M.; Adamowicz, M.; Nowak, M.; Litzbarski, L.S.; Balcarek, K.; Grochowski, J. A Comprehensive System for Protection of Photovoltaic Installations in Normal and Emergency Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iringova, A. Location of Photovoltaic Panels in the Building Envelope in Terms of Fire Safety. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2022, 18, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Zhou, X.; Gong, J.; Zhao, K.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ren, X.; Yang, L. Impact of flat roof–integrated solar photovoltaic installation mode on building fire safety. Fire Mater. 2019, 43, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Ju, X.; Lai, D.; Yang, L. Experimental study of combustion characteristics of PET laminated photovoltaic panels by fire calorimetry. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 253, 112242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, N.A.F.M.N.; Tohir, M.Z.M.; Mutlak, M.M.; Sadiq, M.A.; Omar, R.; Said, M.S.M. BowTie analysis of rooftop grid-connected photovoltaic systems. Process Saf. Prog. 2022, 41, S106–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Poland. Act of 24 June 1994 on Ownership of Premises; Government Legislation Centre: Warsaw, Poland, 1994.

- Sejm RP, “Construction Law.”. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20250000418 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Republic of Poland. Act of August 17, 2023 amending the Act on Renewable Energy Sources and Certain Other Acts; Government Legislation Centre: Warsaw, Poland, 2023.

- Official Journal of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Recast) (Text with EEA Relevance); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalak, R. Charakterystyka pracy instalacji fotowoltaicznej trójpłaszczyznowej małej mocy—Studium przypadku. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny. 2024. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:268683365 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Energa-Operator S.A. Distribution Network Operation and Maintenance Manual, Appendix No. 5 “List of Load Profiles for Profile Customers Connected to ENERGA-OPERATOR S.A. Network; Energa: Gdańsk, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalak, R.; Czapp, S. Improving Voltage Levels in Low-Voltage Networks with Distributed Generation—Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2018 Progress in Applied Electrical Engineering (PAEE), Koscielisko, Poland, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:52130276 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Chwieduk, B.; Chwieduk, D. Analysis of operation and energy performance of a heat pump driven by a PV system for space heating of a single family house in polish conditions. Renew Energy 2021, 165, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeuer, F.; Kleinebrahm, M.; Naber, E.; Scheller, F.; McKenna, R. Optimal system design for energy communities in multi-family buildings: The case of the German Tenant Electricity Law. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicki, L.; Pietrzykowski, R.; Kusz, D. Factors Determining the Development of Prosumer Photovoltaic Installations in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocetkiewicz, I.; Tomaszewska, B.; Mróz, A. Renewable energy in education for sustainable development. Pol. Exp. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mularczyk, A.; Zdonek, I.; Turek, M.; Tokarski, S. Intentions to Use Prosumer Photovoltaic Technology in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pals, H.; Singer, L. Residential energy conservation: The effects of education and perceived behavioral control. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2015, 5, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country/Region | Ownership and Decision-Making Framework | Legal Model for PV Electricity Sharing | Key Regulatory Barriers | Enabling Legal Instruments/Policies | Profitability Implications | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Co-ownership of roof under housing law; strong separation between housing and energy law | Limited internal supply; collective use mainly via special contractual arrangements (e.g., all-in usage contracts) | Internal electricity sales trigger supplier and grid obligations; consumer protection law increases contractual risk | Amendments to Electricity Act (ElWOG, incl. §16a); Green Electricity Act (Ökostromgesetz); pilot projects (e.g., StromBIZ) | Profitability is moderate and highly case-specific; high transaction and compliance costs reduce economic viability | [17] |

| Germany | Co-ownership in multi-family buildings; regulated landlord–tenant relations | Tenant Electricity Model (Mieterstrom): direct on-site supply to tenants | Administrative complexity; metering and billing obligations; dependence on policy incentives | Mieterstromgesetz; partial exemption from grid fees and levies | Profitability can be positive at high self-consumption rates, but remains sensitive to incentive levels | [18,19] |

| United States (California) | Condominium associations/HOAs; shared ownership of common areas | Individual or shared PV; virtual net metering in selected cases | HOA approval procedures; aesthetic restrictions; reduced export compensation | California Solar Rights Act; deemed approval rules; evolving net-metering schemes | Profitability increasingly relies on self-consumption and storage; export-oriented PV less attractive | [20] |

| United States (e.g., New York, Illinois) | State-dependent condominium and landlord–tenant law | Community solar; virtual net metering (state-dependent) | Lack of enabling legislation in some states; limited tenant access to incentives | State community solar acts; federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC); Solar for All | Profitability varies widely by state; community solar improves access but often yields lower returns | [21] |

| Australia | Strata Title system; roof as common property; Owners Corporation approval required | Embedded networks; emerging local energy trading models | High transaction costs; regulatory obligations for embedded network operators; declining feed-in tariffs | State-level limits on banning sustainability infrastructure; AER exemption framework; AS4777 standards [22] | Profitability driven by on-site consumption; embedded networks improve returns but add regulatory complexity | [23] |

| Italy | Condominium co-ownership under Civil Code (Art. 1117); joint decision-making by apartment owners | Jointly Acting Renewable Self-Consumption (JARS); Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) | Incentive dependency; dilution of per capita benefits in large buildings; regulatory complexity | RED II transposition; incentive tariff for shared energy; tax bonuses for PV investment | Empirically positive profitability: payback ~8–9 years; annual per capita benefit when incentives and bill savings are combined | [24] |

| China | Clear distinction between single-family houses and multi-family buildings; collective ownership of roofs in apartment buildings | Predominantly individual residential PV; limited feasibility in multi-family buildings due to collective decision rules | Installation in apartment buildings requires approval of owners’ congress; incomplete property rights; declining subsidies | National PV promotion programs; feed-in mechanisms; targeted rural PV policies; gradual subsidy phase-out | Profitability is high for single-family houses (self-use + grid sales), but remains low and uncertain for multi-family buildings; economic incentives are necessary but insufficient without governance reform | [25] |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Transformer T3O 17.5/630 | |

| Rated power [kVA] | 630 |

| Rated voltage HV–side [kV] | 15.75 |

| Rated voltage LV–side [kV] | 0.42 |

| Short-circuit voltage [%] | 4.5 |

| Copper losses [kW] | 4.6 |

| No load current [%] | 0.35 |

| No load losses [kW] | 0.8 |

| Cable NAYY 4 × 240SE 0.6/1 kV | |

| Rated current [A] | 357 |

| Phases | 3 |

| Nominal frequency [Hz] | 50 |

| AC-resistance r’ (20 °C) [Ω/km] | 0.127 |

| Reactance x’ [Ω/km] | 0.08 |

| Susceptance b’ [μS/km] | 237.3 |

| Solution | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Limitation of installed or generated PV power | Top-down restriction on maximum PV capacity per building or on allowable power generation to prevent network overloading |

|

|

| 2. Oversizing of network components | Designing transformers and network elements to accommodate maximum potential PV generation |

|

|

| 3. Energy storage or local use of surplus energy | Use of electrical storage systems or conversion of surplus PV electricity into heat (e.g., domestic hot water, heat pumps) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kowalak, R.; Kowalak, D.; Seklecki, K.; Litzbarski, L.S. Challenges in the Legal and Technical Integration of Photovoltaics in Multi-Family Buildings in the Polish Energy Grid. Energies 2026, 19, 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020474

Kowalak R, Kowalak D, Seklecki K, Litzbarski LS. Challenges in the Legal and Technical Integration of Photovoltaics in Multi-Family Buildings in the Polish Energy Grid. Energies. 2026; 19(2):474. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020474

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalak, Robert, Daniel Kowalak, Konrad Seklecki, and Leszek S. Litzbarski. 2026. "Challenges in the Legal and Technical Integration of Photovoltaics in Multi-Family Buildings in the Polish Energy Grid" Energies 19, no. 2: 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020474

APA StyleKowalak, R., Kowalak, D., Seklecki, K., & Litzbarski, L. S. (2026). Challenges in the Legal and Technical Integration of Photovoltaics in Multi-Family Buildings in the Polish Energy Grid. Energies, 19(2), 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020474