Bi-Objective Intraday Coordinated Optimization of a VPP’s Reliability and Cost Based on a Dual-Swarm Particle Swarm Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

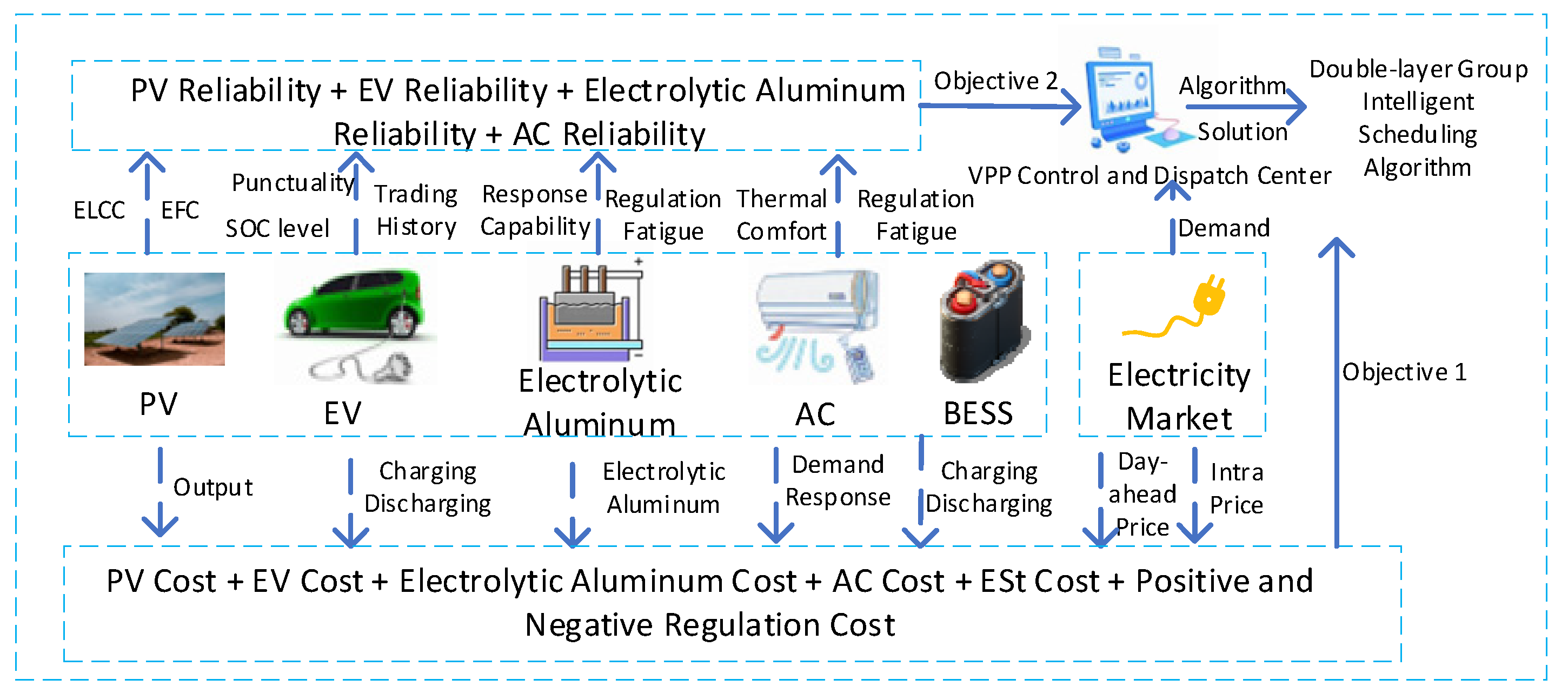

2. VPP Operational Framework

3. Intraday Resource Modeling

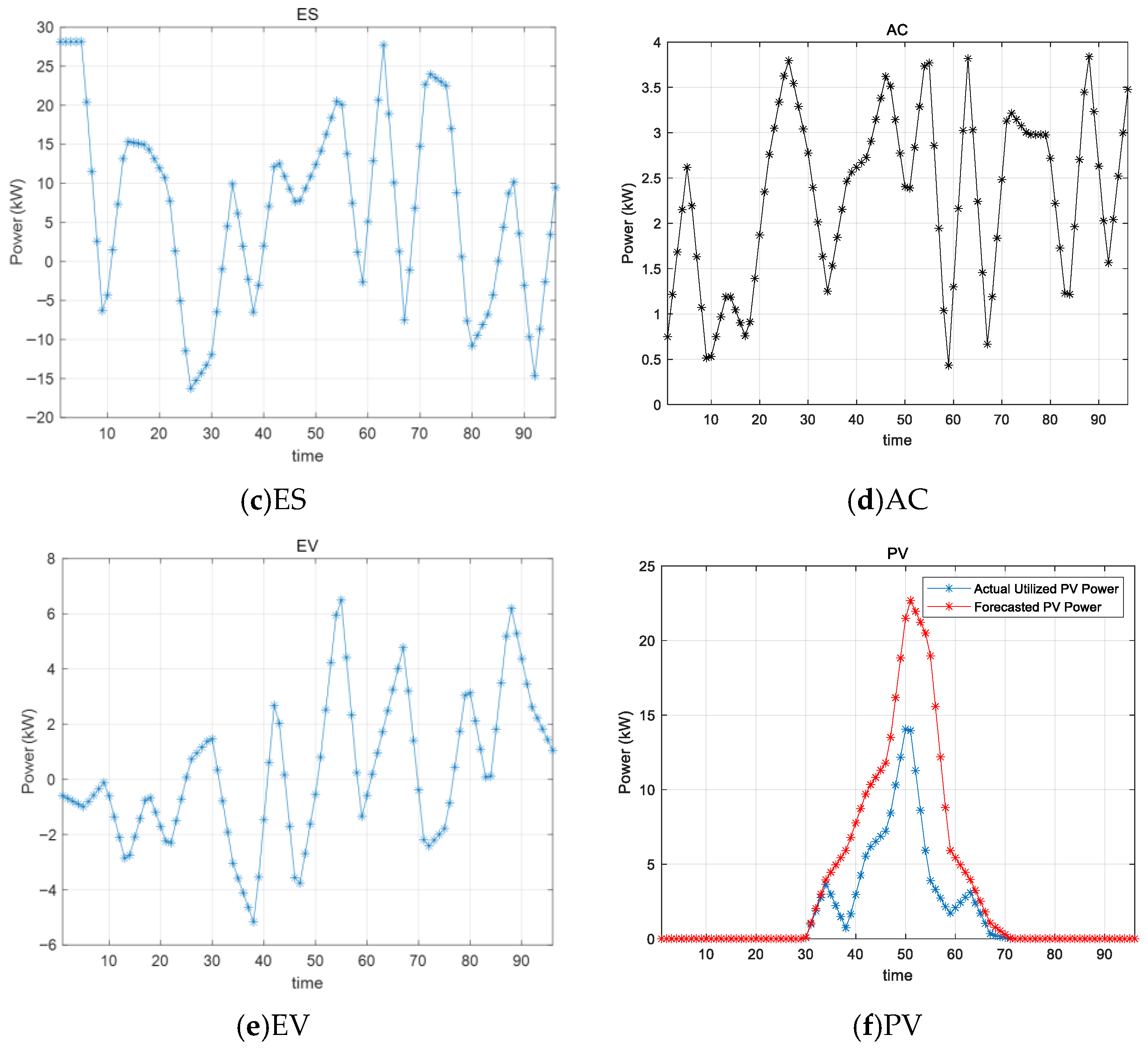

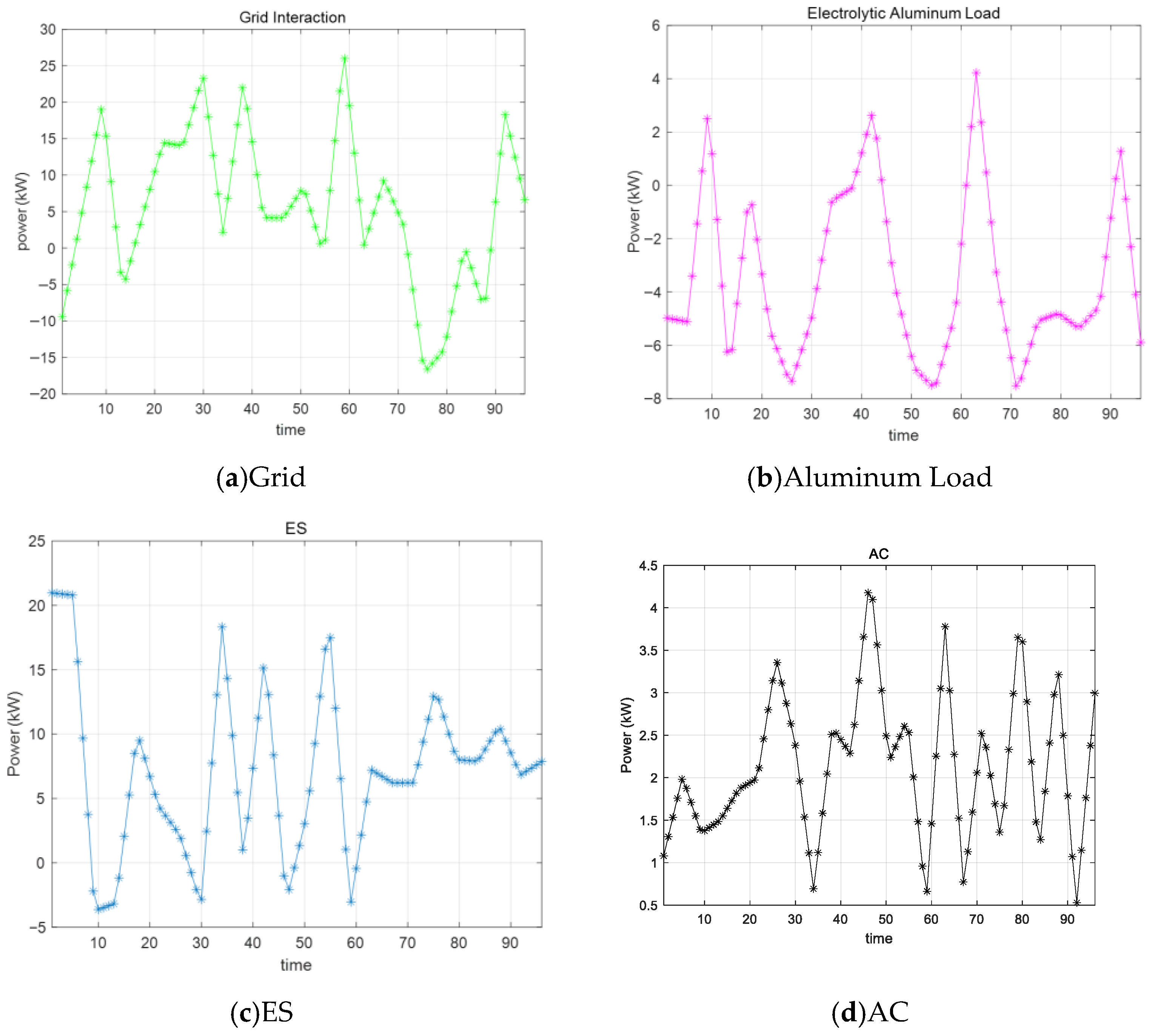

3.1. PV Output Modeling

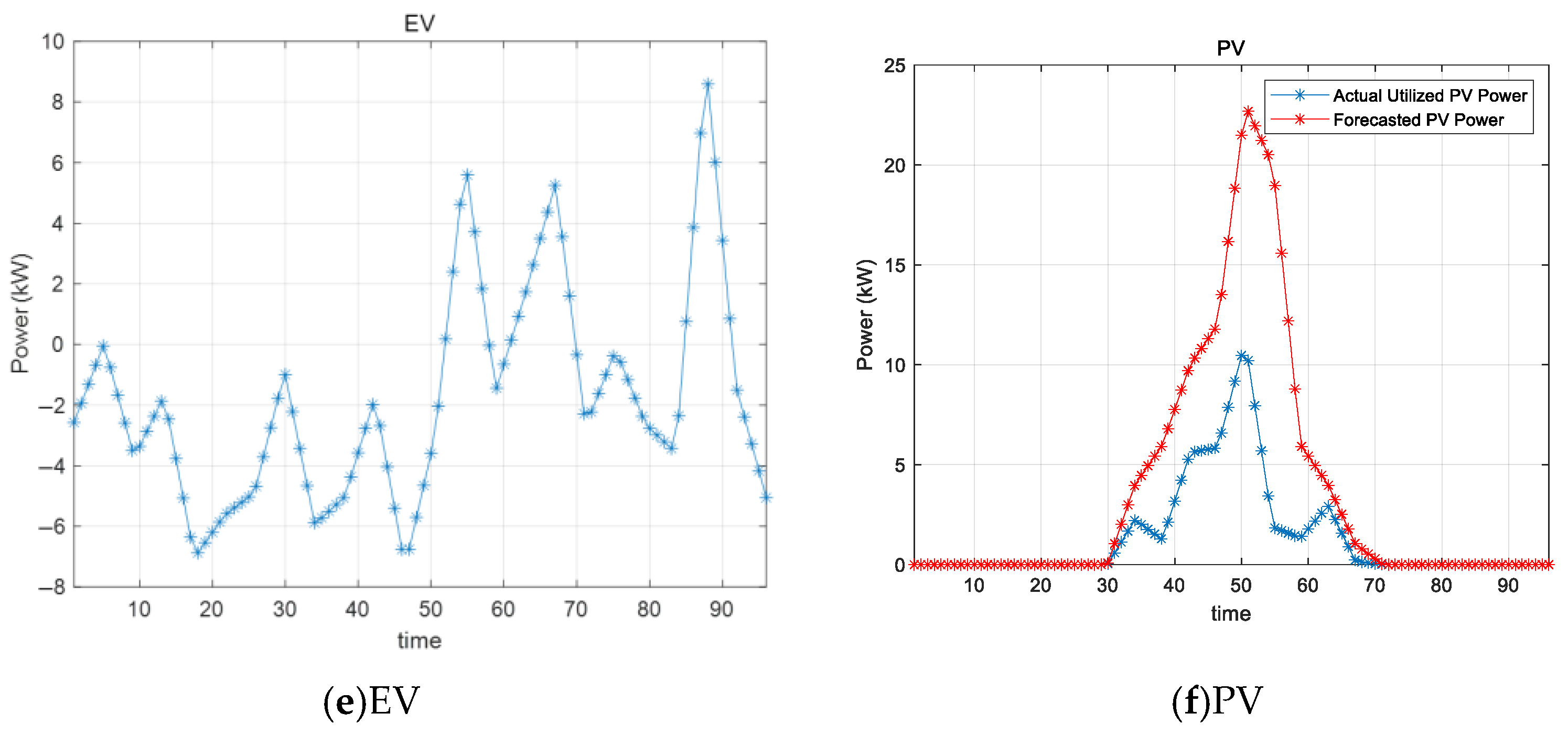

3.2. EV Modeling

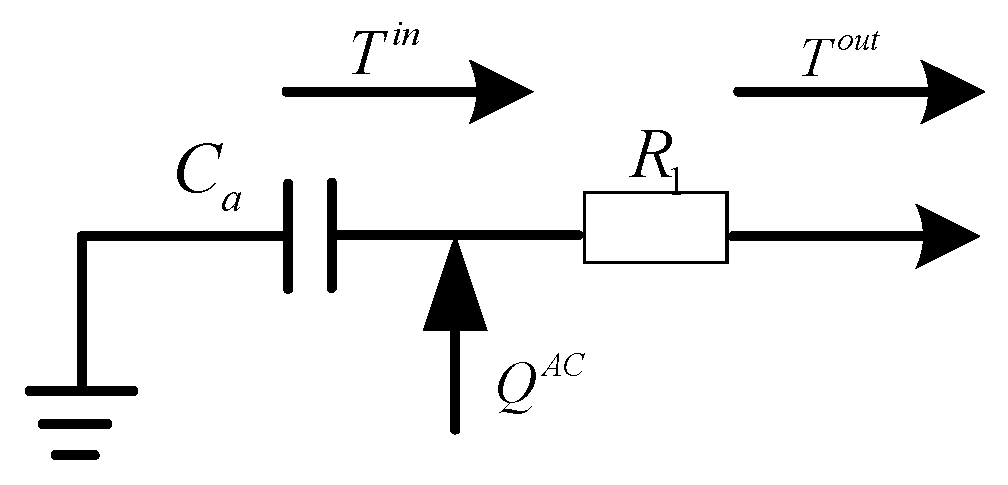

3.3. AC Load Modeling

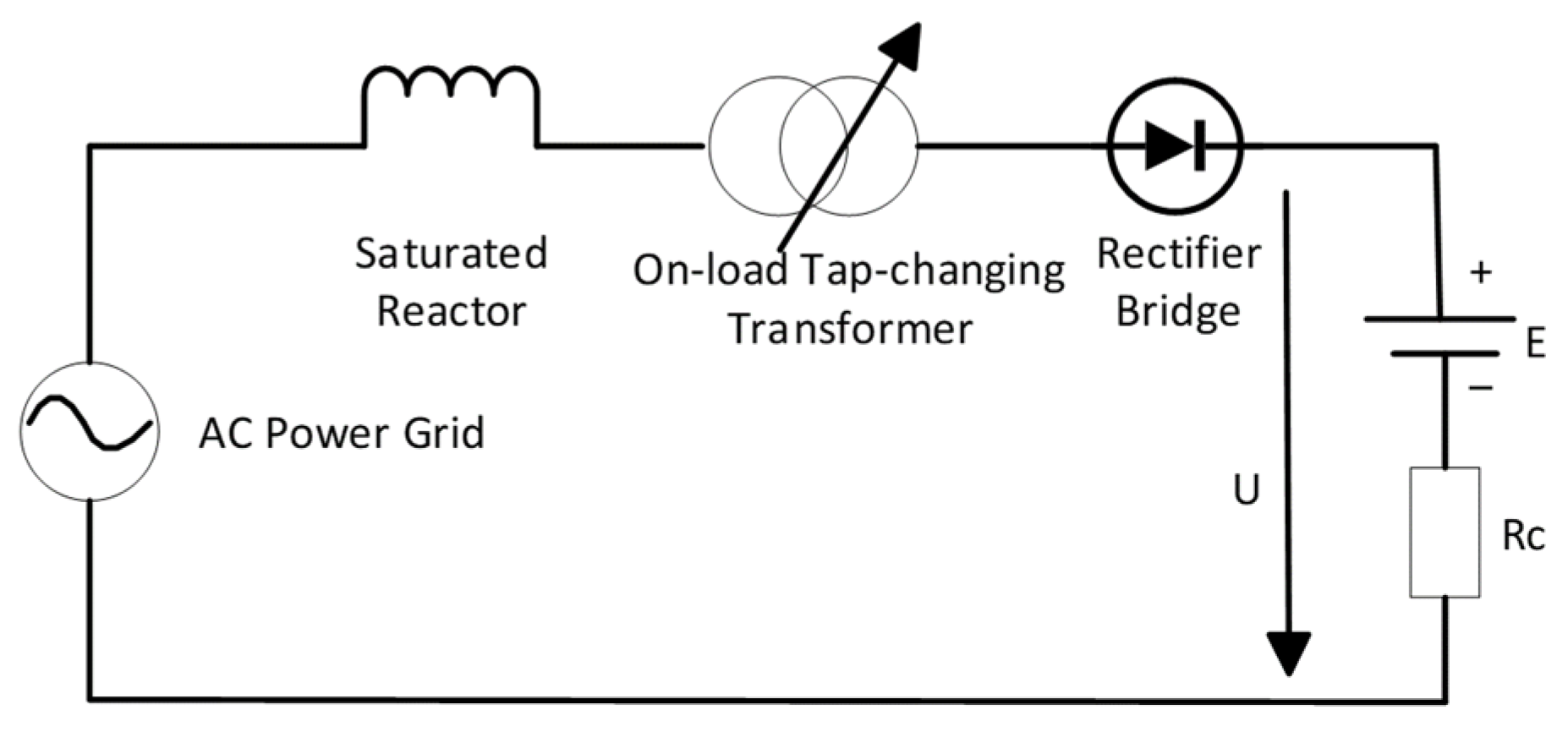

3.4. Electrolytic Aluminum Load

3.5. BESS

4. Intraday Resource Credibility Modeling

4.1. PV Credibility Index

4.2. EV Credibility Index

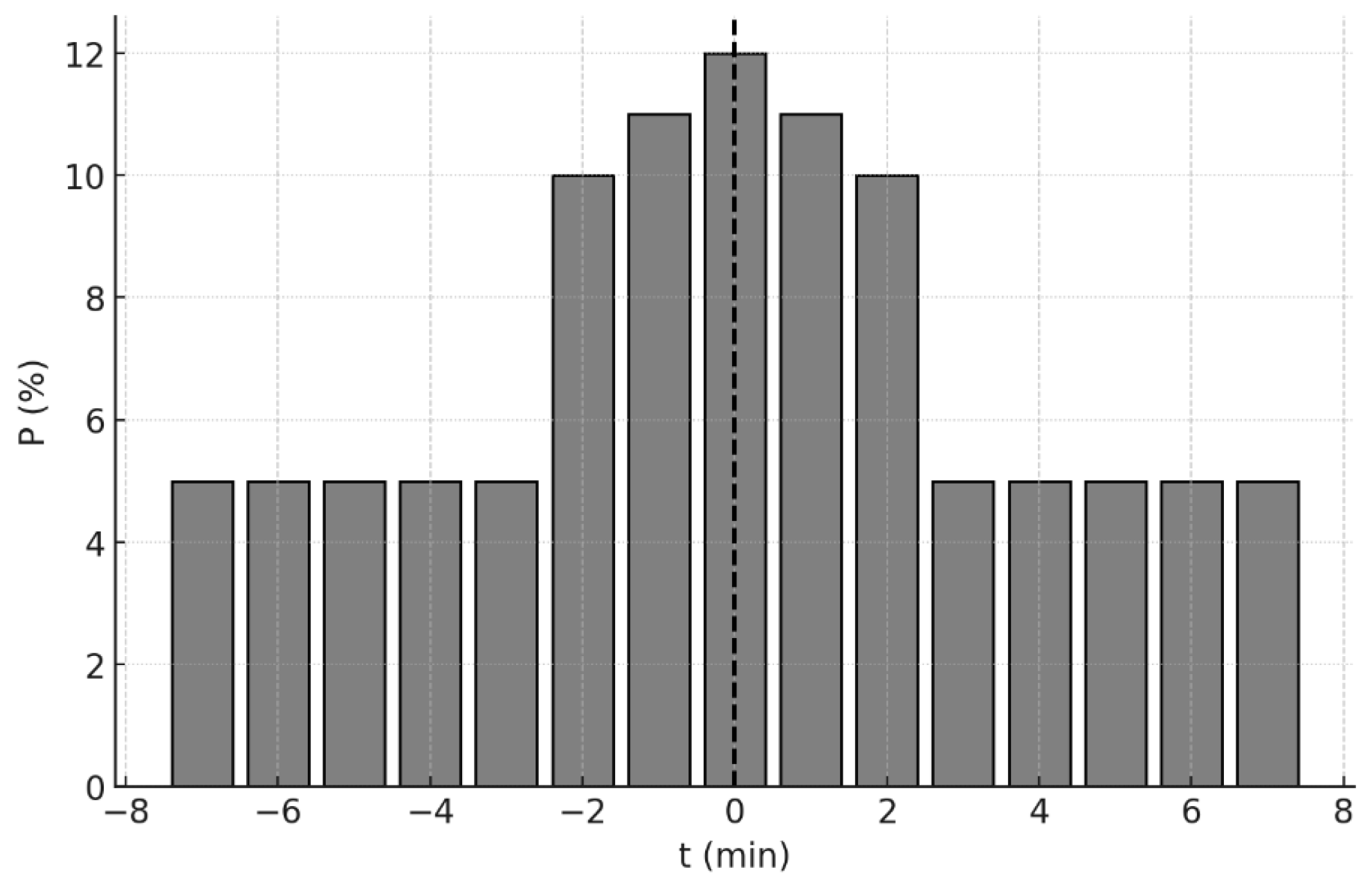

4.2.1. EV Punctuality

4.2.2. SOC Level

4.2.3. Historical Transaction Credibility

4.2.4. Comprehensive Credibility Index

4.3. AC Load Credibility Index

4.3.1. Time Period Credibility

4.3.2. Remaining Credibility

4.3.3. Response Fatigue Credibility

4.3.4. Comprehensive Credibility Calculation

4.4. Electrolytic Aluminum Load Credibility Index

4.4.1. Response Capacity Index

4.4.2. Response Fatigue Index

4.4.3. Comprehensive Credibility Calculation

4.5. BESS Credibility Index

5. Intraday Precision Coordinated Optimization

5.1. Construction of the Cost Objective Function

5.2. Construction of the Credibility Objective Function

5.3. Constraint Conditions

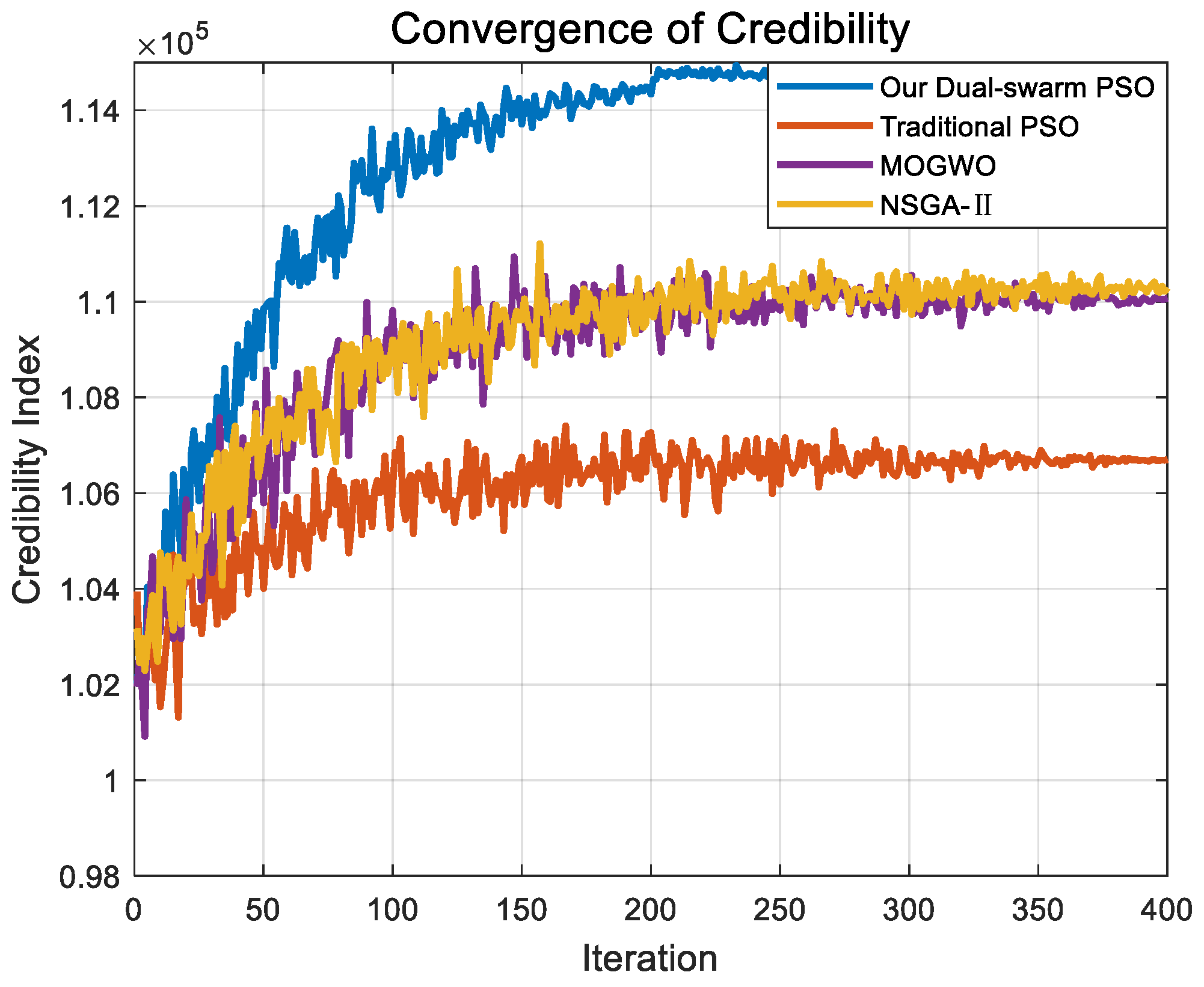

5.4. Multi-Objective Optimization Based on Dual-Subpopulation Cooperative PSO

6. Example Analysis

6.1. Parameter Settings

| Max Iterations | Swarm Size | Grid Inflation Factor | Leader Selection Pressure | Archive/Repository Size | Deletion Pressure | Mutation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 150 | 0.1 | 2 | 100 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

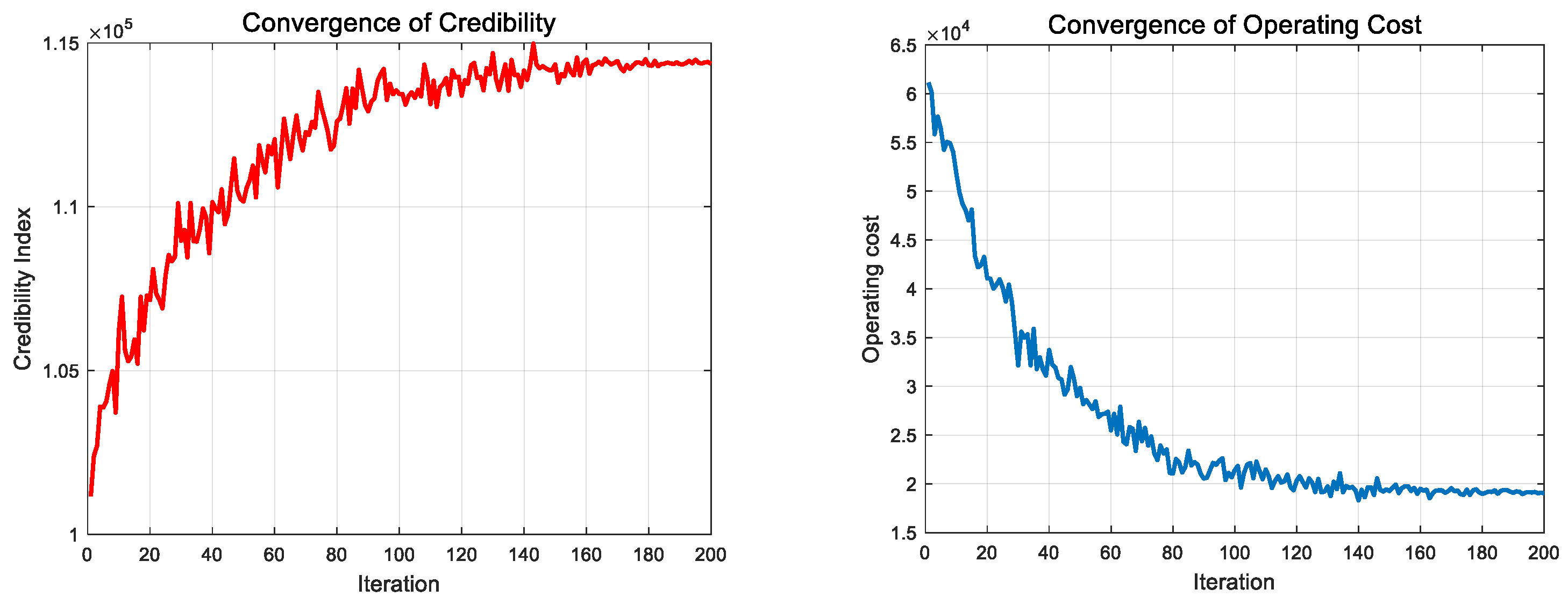

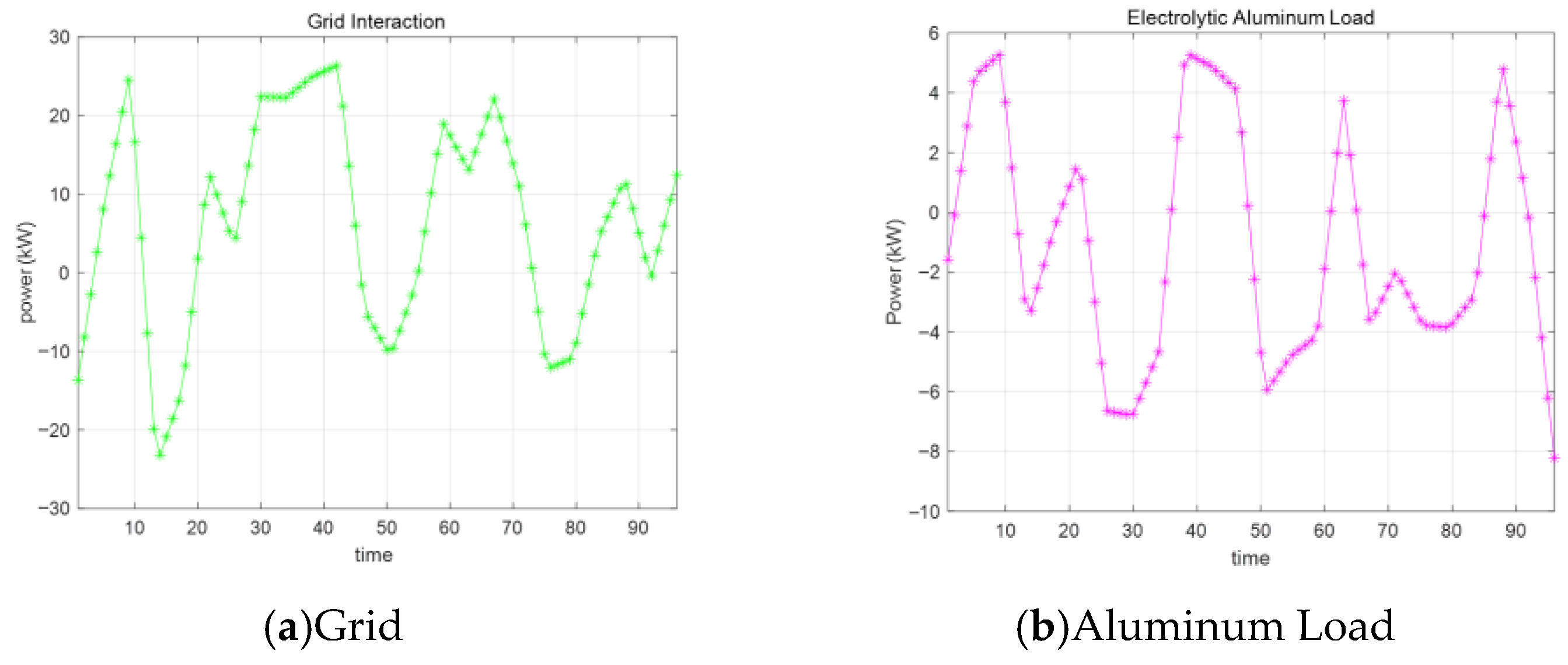

6.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Results

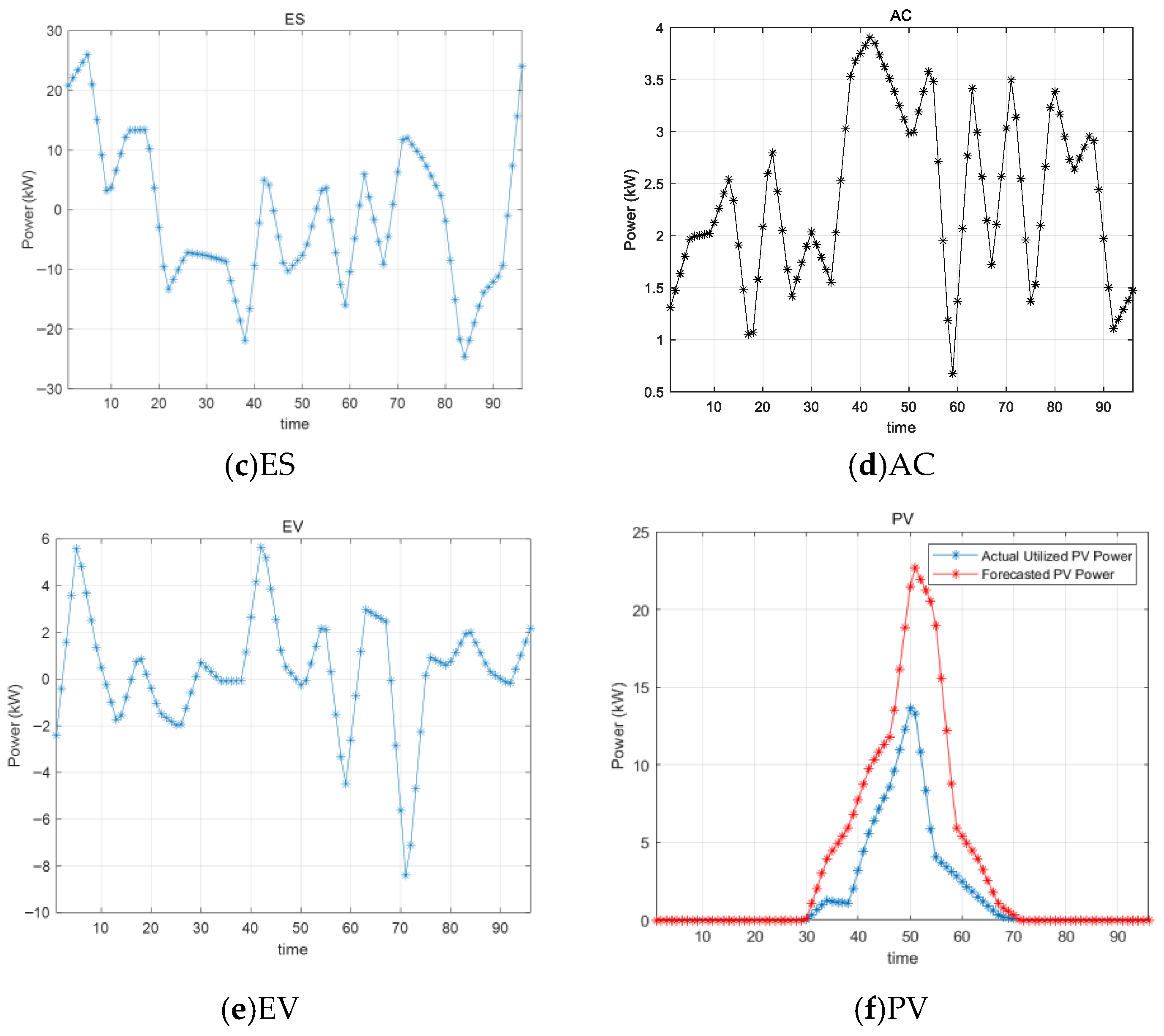

6.3. Optimized Cost Results with Imbalance Price Coefficients Results

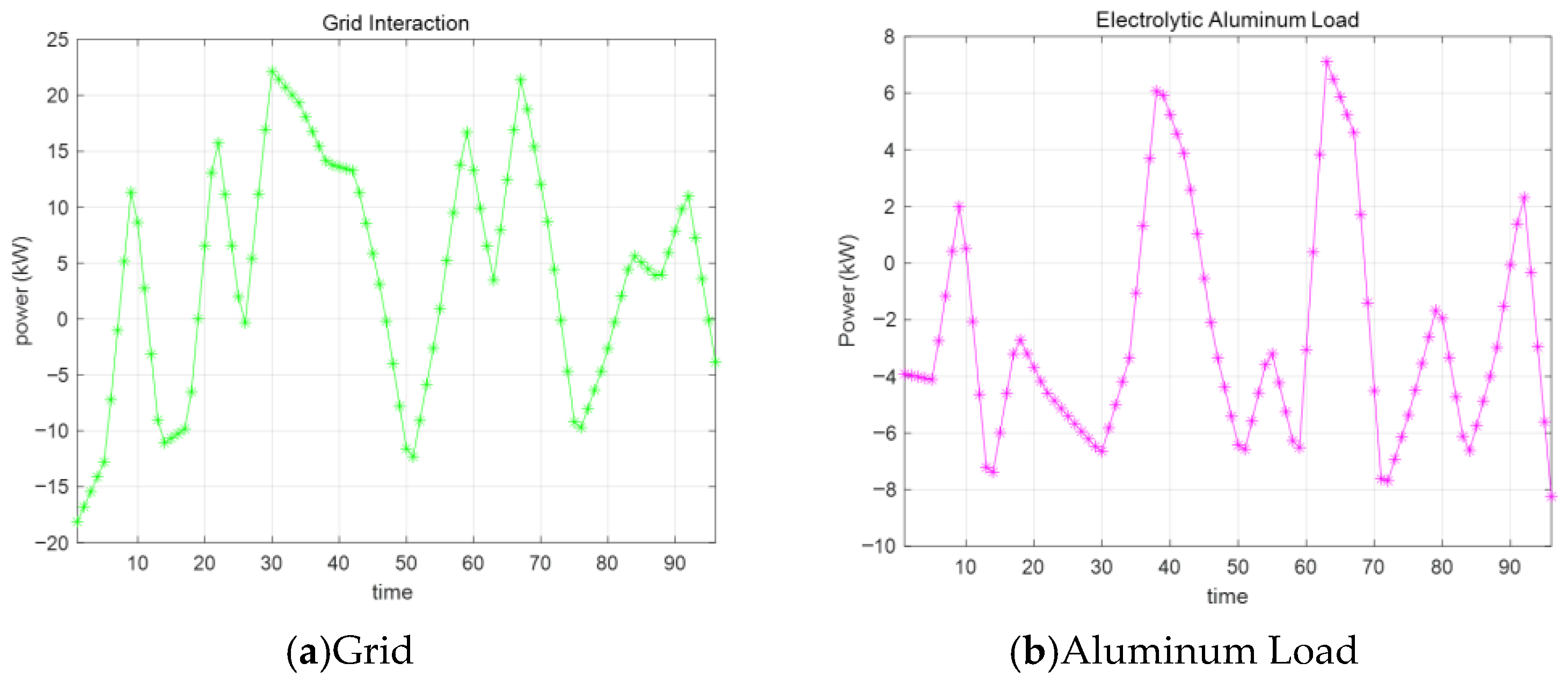

6.4. Standard Cost Minimization Results

6.5. Compare

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, C.; Du, E.; Guo, H.; Li, Y.W.; Fang, Y.C.; Zhang, N.; Zhong, H.W. Primary Exploration of Six Essential Factors in New Power System. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Nosratabadi, S.M.; Hooshmand, R.-A.; Gholipour, E. A Comprehensive Review on Microgrid and Virtual Power Plant Concepts Employed for Distributed Energy Resources Scheduling in Power Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ai, Q. Research on Demand Side Response Strategy of Multi-Microgrids Based on Improved Co-evolution Algorithm. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 7, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z. Research on Coordinated Scheduling of Heterogeneous Loads in Smart Buildings Under Multi-time Scales. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, L.; Lan, J.; Zhou, L.; Ye, M.; Ma, L.; Chen, H. Multi-timescale Frequency Regulation Control of Flexible Resources in Virtual Power Plant. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2024, 48, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Yun, Y.; Wang, X.; He, J. Multi-time Scale of New Energy Scheduling Optimization for Virtual Power Plant Considering Uncertainty of Wind Power and Photovoltaic Power. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2022, 43, 529–537. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Ai, Q. Novel Optimal Dispatch Method for Multiple Energy Sources in Regional Integrated Energy Systems Considering Wind Curtailment. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 10, 2166–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, G.; Peng, J.; Li, W.; Yuan, Y. Low-carbon Economic-robust Optimization Scheduling of Multi-energy Complementary Virtual Power Plants. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 9718–9731. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H.; Dou, W.; Yuan, J.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Jing, T. Response Interval Evaluation Method of Virtual Power Plant Considering Multiple Uncertainties. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2024, 44, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen, D.; Willén, O. A Study of Electric Vehicle Charging Patterns and Range Anxiety. Department of Engineering Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, Rep. UPTEC STS13 015, June 2013. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A626048&dswid=516 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Gao, Y.; Ai, Q.; He, X.; Fan, S. Coordination for Regional Integrated Energy System Through Target Cascade Optimization. Energy 2023, 276, 127606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Gao, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, R.; Li, W.; Xie, Q. Multi-objective Scheduling Optimization of An Integrated Energy System Considering Variable Efficiency of Energy Conversion Devices. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 2025, 53, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, C.; Chen, S.; Hao, X.; Sun, X. Multi-objective Optimization Dispatching of Microgrid Based on Improved Particle Swarm Algorithm. Electr. Power Sci. Eng. 2021, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Alsabbagh, A.; Wu, B.; Ma, C. Distributed Electric Vehicles Charging Management Considering Time Anxiety and Customer Behaviors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 2422–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wen, J. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Continuous Electric Vehicles Charging Control with Dynamic User Behaviors. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5124–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Ai, Q.; Wang, D.; Ding, Y.; Wu, J.; Xie, Y. Day-ahead Robust Bidding Strategy for Prosumer Considering Virtual Energy Storage of Air-conditioning Load. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2020, 44, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Gao, C.; Yan, H.; Yang, J. Thermal Battery Modeling of Inverter Air Conditioning for Demand Response. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 5522–5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Low-Carbon Economic Dispatch of Power System Considering Electrolytic Aluminum Load for Demand Response; Huazhong University of Science and Technology: Wuhan, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Hao, L.; Xv, F.; Min, Y. Industrial Load Peak Regulation and its Secondary Frequency Regulation Capacity Assessment Considering Intra-Production Segment Characteristics. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 3613–3622. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Kang, C.; Xiao, J.; Hui, L. Review and Prospect of Wind Power Capacity Credit. Proc. CSEE 2015, 35, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld, P. Rounding of arrival and departure times in travel surveys: An interpretation in terms of scheduled activities. J. Transp. Statist. 2002, 5, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, M.; Dix, M.; Jones, P. Error and Uncertainty in Travel Surveys. Transportation 1981, 10, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cheng, N.; Jiang, Y. Multi-time-scale Scheduling Strategy of V2G Aggregators Considering EV Peak Regulating Demand Response Reliability. High Volt. Eng. 2025, 51, 401–411. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, P.; Qi, J.; Xiong, Y.; Hu, K.; Han, Y.; Zhao, X. Demand-side Precision Peak Shaving Strategy Considering Response Reliability and Economy. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2025, 49, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

| Charging Participation Dispatch | Discharging Participation Dispatch | |

|---|---|---|

| ✔ | ✕ | |

| ✔ | ✔ | |

| ✕ | ✔ |

| Algorithm: Dual-Subpopulation Cooperative PSO for Multi-Objective Optimization |

|---|

| 1. Initialize particle positions, velocities, divide into Subpopulations A and B, initialize Elite Archive. |

| 2. Cold-start phase: Compute instance representativeness, select top representative instances, query labels and update target. |

| 3. Main learning phase: Repeat until query budget is reached: |

| - Compute fitness value and update particle positions |

| - Compute label uncertainty, update target |

| - Update prediction network |

| 4. Termination condition: Terminate when max iterations or query budget is reached, output non-dominated solutions from Elite Archive |

| EV | AC | BESS | Electrolytic Aluminum Load | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOCd | SOCmax | SOCmin | Q | R | C | Tin | Tout | SOCmin | Rc | Uac | UR | ||

| 90 | 100 | 20 | 40 kWh | 5 kWh/°C | 24 °C | 35 °C | 5 | 0.9 | 400 V | 10 V | 0.9 | ||

| Optimization Method | Total Cost Reduction Rate | System Reliability Improvement Rate | Power Deviation Reduction Rate | Convergence Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our method | 6.8% | 12.5% | 14.8% | 200 iterations |

| Traditional PSO | 3.4% | 4.6% | 7.9% | 350 iterations |

| NSGA-II | 4.5% | 8.1% | 10.2% | 400 iterations |

| MOGWO | 3.5% | 7.9% | 9.1% | 380 iterations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhan, J.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Jiang, J.; Gao, Y. Bi-Objective Intraday Coordinated Optimization of a VPP’s Reliability and Cost Based on a Dual-Swarm Particle Swarm Algorithm. Energies 2026, 19, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020473

Zhan J, Sun X, Li Y, Sun W, Jiang J, Gao Y. Bi-Objective Intraday Coordinated Optimization of a VPP’s Reliability and Cost Based on a Dual-Swarm Particle Swarm Algorithm. Energies. 2026; 19(2):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020473

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhan, Jun, Xiaojia Sun, Yang Li, Wenjing Sun, Jiamei Jiang, and Yang Gao. 2026. "Bi-Objective Intraday Coordinated Optimization of a VPP’s Reliability and Cost Based on a Dual-Swarm Particle Swarm Algorithm" Energies 19, no. 2: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020473

APA StyleZhan, J., Sun, X., Li, Y., Sun, W., Jiang, J., & Gao, Y. (2026). Bi-Objective Intraday Coordinated Optimization of a VPP’s Reliability and Cost Based on a Dual-Swarm Particle Swarm Algorithm. Energies, 19(2), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020473