Study of Co-Combustion of Pellets and Briquettes from Lignin in a Mixture with Sewage Sludge

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparing Fuels for Research

- No. 1—sewage sludge (SS);

- No. 2—lignin pellets (LP);

- No. 3—lignin briquettes (LB).

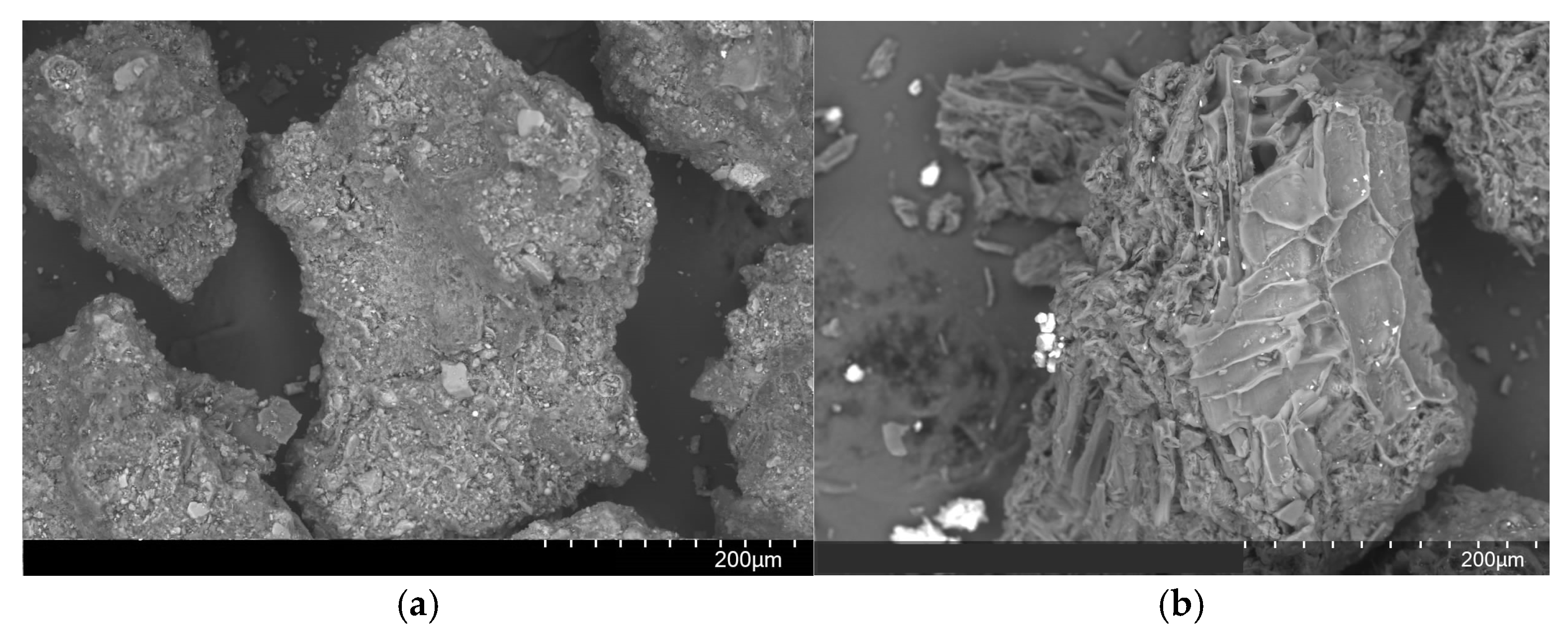

2.2. Analysis of Fuel Particle Surface and Chemical Composition of Ash

2.3. Methodology for Conducting TGA

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of the Thermal, Morphological, and Chemical Analysis of the Ash

3.2. Analysis of TGA Curves During Heating of Individual Fuels

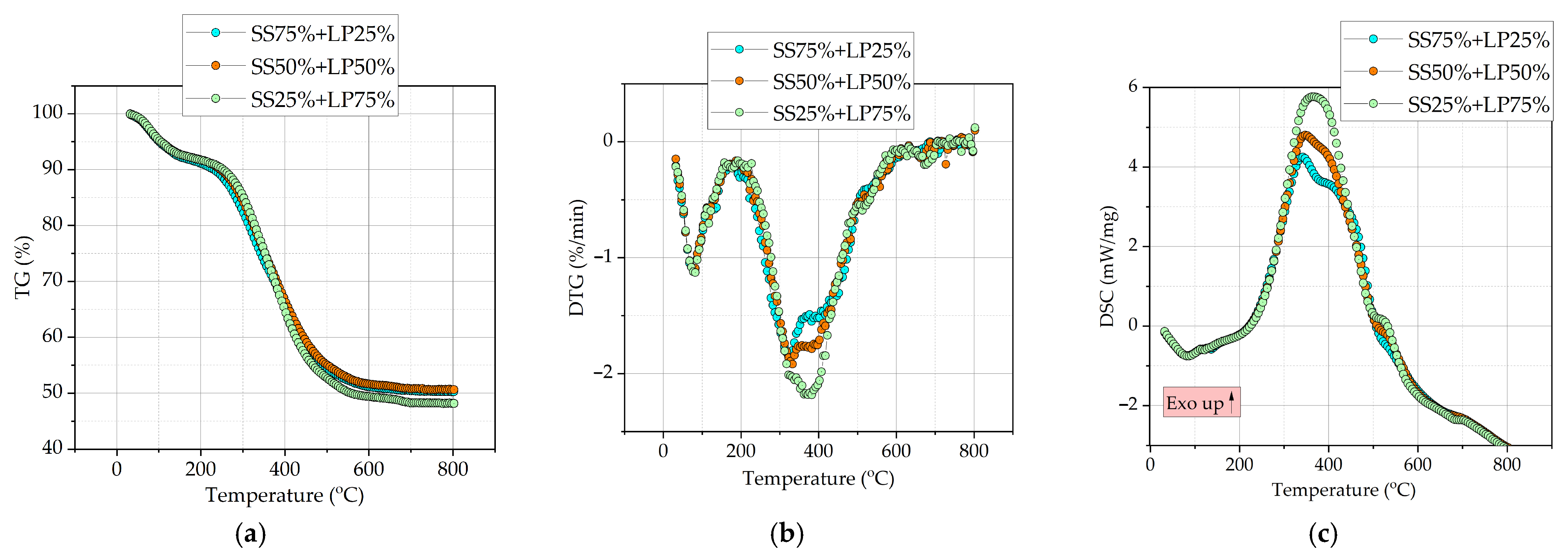

3.3. Analysis of TGA Curves During Heating of Fuel Mixtures

3.4. Analysis of the Influence of Mixture Components on the Combustion Rate of Coke Residue

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ad | ash a dry state (%) |

| Cdaf, Hdaf, Ndaf, Odaf, Sdaf | fraction of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur converted to a dry ash-free state (%) |

| DTGex | DTG curves obtained during thermal analysis (%/min) |

| DTGtr | DTG curves theoretically obtained (%/min) |

| DSCmax | maximum heat flux value (W/g) |

| lower heating value in working condition (MJ/kg) | |

| higher heating value in dry ash-free state (MJ/kg) | |

| Wr | moisture in working condition (%) |

| Wa | moisture content in the analytical state (%) |

| Q | combustion efficiency index (min−2 °C−3) |

| Tb | ending-oxidation temperature (°C) |

| TR | temperature DTGmax (°C) |

| TDSC | temperature DSCmax (°C) |

| Ti | ignition temperature (°C) |

| Vdaf | gaseous content in dry ash-free state (%) |

| Rmax | maximum combustion rate (%/min) |

| Rmean | average combustion rate in the temperature range from Ti to Tb (%/min) |

References

- Ling, Z.S.; Jaafar, M.H.; Ismail, N. The knowledge, attitudes and practices in circular economy: A review of industrial waste management in China. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 11, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshmand-Jahromi, S.; Sedghkerdar, M.H.; Mahinpey, N. A review of chemical looping combustion technology: Fundamentals, and development of natural, industrial waste, and synthetic oxygen carriers. Fuel 2023, 341, 127626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zhang, J.; An, K.; Shi, N.; Li, P.; Li, B. Recent advances in recycle of industrial solid waste for the removal of SO2 and NOx based on solid waste sorts, removal technologies and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364, 132338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liang, T.; Cheng, M.; Chen, L.; Mei, C.; Dai, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, B. Recent advances in CO2 mineralization by alkaline industrial solid waste: Mechanisms, applications and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, C.; Hu, S.; Li, L.; Li, X. Environmental and life cycle assessment of organic Rankine cycle technology for industrial waste heat recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Normazlan, W.M.D.; Buthiyappan, A.; Mohd Jais, F.; Abdul Raman, A.A. Exploring the potential of industrial and municipal wastes for the development of alternative fuel source: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 194, 904–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yang, K.; Sun, X.; Zhu, X.; Chen, W.; Hou, D.; Cheng, Z.; Yan, B. Advances in biomass chemical looping combustion technology: Process control and comprehensive evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.T.; Naqvi, M.; Li, B.; Raza, R.; Khan, A.; Taqvi, S.A.A.; Nizami, A.-S. From Waste to Watts: Emerging role of waste lignin-derived materials for energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 82, 110477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libretti, C.; Santos Correa, L.; Meier, M.A.R. From waste to resource: Advancements in sustainable lignin modification. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 4358–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiju, P.S.; Singhania, R.R.; Shruthy, N.S.; Shalu, S.; Dong, C.-D.; Patel, A.K. Lignin-derived biomaterials for environmental application, advancements in sustainable leather and bioplastic production: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 322, 146887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Bi, H.; Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Tian, J.; Yao, Y.; He, L.; Meng, K.; Lin, Q. Effect of lignin on coal slime combustion characteristics and carbon dioxide emission. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 140884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniza, R.; Chen, W.-H.; Herrera, C.J.A.; Quirino, R.; Petrissans, M.; Petrissans, A. Bioenergy and bioexergy analyses with artificial intelligence application on combustion of recycled hardwood and softwood wastes. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.J.; Hornsby, K.; Cheah, K.W.; Hurst, P.; Walker, S.; Skoulou, V. Repurposing lignin rich biorefinery waste streams into the next generation of sustainable solid fuels. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 7, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, G.; Yin, J.; Jin, Z.; Jin, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, X. Optimized co-combustion of paper-making solid wastes via, genetic algorithm: Synergistic enhancement and coal-substitution potential. Waste Manag. 2025, 207, 115114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M.; Khan, M.U.; Bokhary, A.; Ahring, B.K. Emerging trends in sewage sludge pretreatment: Enhancing treatment efficiency and sustainable waste management. Clean. Water 2025, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leino, O.; Äystö, L.; Fjäder, P.; Perkola, N.; Lehtoranta, S. Contaminants of environmental concern in sewage sludge in the Nordic countries. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 381, 126604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, G.; Fürsatz, K.; Long, A.; Hannl, T.K.; Schubert, T. Exploring the potential of sewage sludge for gasification and resource recovery: A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 40, 104346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinin, Y.V.; Yazykov, N.A.; Lyulyukin, A.P.; Yakovlev, V.A. Combustion of sewage sludge in a fluidized bed of catalyst: From laboratory to the pilot plant. Waste Manag. 2025, 204, 114944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniza, R.; Chen, W.-H.; Kwon, E.E.; Bach, Q.-V.; Hoang, A.T. Lignocellulosic biofuel properties and reactivity analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) toward zero carbon scheme: A critical review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 22, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rago, Y.P.; Collard, F.-X.; Görgens, J.F.; Surroop, D.; Mohee, R. Co-combustion of torrefied biomass-plastic waste blends with coal through TGA: Influence of synergistic behaviour. Energy 2022, 239, 121859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieush, L.; Koveria, A.; Sommersacher, P.; Retschitzegger, S.; Kienzl, N. Co-Pyrolysis of Biomass with Bituminous Coal in a Fixed-Bed Reactor for Biofuel and Bioreducing Agents Production. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvez-Tovar, B.; Scalize, P.S.; Angiolillo-Rodríguez, G.; Albuquerque, A.; Ebang, M.N.; de Oliveira, T.F. Agro-Industrial Waste Upcycling into Activated Carbons: A Sustainable Approach for Dye Removal and Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Xu, K.; Hui, B.; Li, Z.; Xia, Z.; Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Tan, H.; Zhang, X.; Du, Z. Investigation on co-combustion characteristics of sewage sludge char with biomass: Thermal behavior, synergistic effect, ash melting characteristics and kinetic analysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 202, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbancl, D.; Agačević, D.; Gradišnik, E.; Šket, A.; Štajnfelzer, N.; Goričanec, D.; Petrovič, A. The Torrefaction of Agricultural and Industrial Residues: Thermogravimetric Analysis, Characterization of the Products and TG-FTIR Analysis of the Gas Phase. Energies 2025, 18, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Wei, R.; Zhou, D.; Long, H.; Li, J.; Xu, C. Co-Combustion of Food Solid Wastes and Pulverized Coal for Blast Furnace Injection: Characteristics, Kinetics, and Superiority. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Jin, M.-H.; Lee, Y.-J.; Song, G.-S.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, D.-W.; Choi, Y.-C.; Park, S.-J.; Song, K.H.; Kim, J.-G. Two-in-One Fuel Synthetic Bioethanol-Lignin from Lignocellulose with Sewage Sludge and Its Air Pollutants Reduction Effects. Energies 2019, 12, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3310-1:2016; Test Sieves—Technical Requirements and Testing—Part 1: Test Sieves of Metal Wire Cloth. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 18134-1:2022; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Moisture Content. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 18122:2022; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Ash Content. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 18123:2023; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Volatile Matter. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 18125:2017; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Calorific Value. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 16948:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 16994:2016; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Sulfur and Chlorine. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO/TS 20048-1:2020; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Off-Gassing and Oxygen Depletion Characteristics. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Oladejo, J.M.; Adegbite, S.; Pang, C.H.; Liu, H.; Parvez, A.M.; Wu, T. A novel index for the study of synergistic effects during the co-processing of coal and biomass. Appl. Energy 2017, 188, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuikov, A.; Pyanykh, T.; Kolosov, M.; Grishina, I.; Zhuikova, Y.; Kuznetsov, P.; Chicherin, S. Improving Energy Efficiency of Wastewater Residue Biomass Utilisation by Co-Combustion with Coal. Energies 2025, 18, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wen, C.; Liu, T.; Xu, M.; Ling, P.; Wen, W.; Li, R. Combustion and co-combustion of biochar: Combustion performance and pollutant emissions. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Abu-Jdayil, B.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; Inayat, A. Kinetic and thermodynamic analyses of date palm surface fibers pyrolysis using Coats-Redfern method. Renew. Energy 2022, 183, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuikov, A.V.; Glushkov, D.O.; Kuznetsov, P.N.; Grishina, I.I.; Samoilo, A.S. Ignition of two-component and three-component fuel mixtures based on brown coal and char under slow heating conditions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 11965–11976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armakan, S.; Civan, M.; Yurdakul, S. Determining co-combustion characteristics, kinetics and synergy behaviors of raw and torrefied forms of two distinct types of biomass and their blends with lignite. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 12855–12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zuo, H.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Xue, Q.; Wang, J. Co-combustion behavior, kinetic and ash melting characteristics analysis of clean coal and biomass pellet. Fuel 2022, 324, 124727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, A.S.; Siddique, R.; Singh, G. Review on the effect of sewage sludge ash on the properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xu, X.; Gu, X.; Hu, D.; Zhou, Z. Enhanced antioxidant activity of lignin for improved asphalt binder performance and aging resistance in sustainable road construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 471, 140364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, H.; Yao, Y.; Tian, J.; Hu, P.; He, L.; Lin, Q.; Liu, L. Co-combustion of sewage sludge with corn stalk based on TG-MS and TG-DSC: Gas products, interaction mechanisms, and kinetic behavior. Energy 2024, 308, 132747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Ma, X.; Fang, S.; Yu, Z.; Lin, Y. Thermogravimetric analysis of the co-combustion of eucalyptus residues and paper mill sludge. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 106, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ma, X.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Z.; Fang, S. Thermogravimetric analysis of the co-combustion of paper mill sludge and municipal solid waste. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 99, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bi, H.; Tian, J.; Ni, Z.; Shi, H.; Yao, Y.; Meng, K.; Wang, J.; Lin, Q. Thermogravimetric analysis of co-combustion characteristics of sewage sludge and bamboo scraps combined with artificial neural networks. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Names of Mixtures | Decoding of Names |

|---|---|

| SS75% + LP25% | 75% sewage sludge + 25% lignin pellets |

| SS50% + LP50% | 50% sewage sludge + 50% lignin pellets |

| SS25% + LP75% | 25% sewage sludge + 75% lignin pellets |

| SS75% + LB25% | 75% sewage sludge + 25% lignin briquette |

| SS50% + LB50% | 50% sewage sludge + 50% lignin briquette |

| SS25% + LB75% | 25% sewage sludge + 75% lignin briquette |

| No. | Main Stages | Equipment | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| The preparation of fuels for thermogravimetric analysis | |||

| 1 | Grinding fuel in a mill | Retsch DM200 (Haan, Germany) | ISO 3310-1:2016 “Test sieves—Technical requirements and testing—Part 1: Test sieves of metal wire cloth” [27] |

| 2 | Sieving of fuels on an analytical machine to sizes of 150–250 μm | Retsch AS200 (Haan, Germany) | ISO 3310-1:2016 “Test sieves—Technical requirements and testing—Part 1: Test sieves of metal wire cloth” [27] |

| Conducting a thermotechnical analysis of fuels | |||

| 3 | Humidity determination (status: Wr—working; Wa—analytical) | Moisture analyser MA-150 Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany | ISO 18134-1:2022 “Solid biofuels—Determination of moisture content” [28] |

| 4 | Determination of ash content (status: Ad—dry) | Muffle furnace Snol 7.2/1300 (AB ‘Umega’, Utena, Lithuania) | ISO 18122:2022 “Solid biofuels—Determination of ash content” [29] |

| 5 | Determination of volatile substances (status: Vdaf—dry ash-free) | Muffle furnace Snol 7.2/1300 (AB ‘Umega’, Utena, Lithuania) | ISO 18123:2023 “Solid biofuels—Determination of volatile matter” [30] |

| 6 | Determination of combustion heat (status: —lowest, working; —highest, dry, ash-free) | Calorimeter C6000 (IKA, Staufen, Germany) | ISO 18125:2017 “Solid biofuels—Determination of calorific value” [31] |

| 7 | Determination of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen (status: Cdaf, Hdaf, Ndaf—dry ash-free) | Vario MACRO cube device (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany) | ISO 16948:2015 “Solid biofuels—Determination of total content of carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen” [32] |

| 8 | Determination of sulphur (status: Sdaf—dry ash-free) | Chemical method | ISO 16994:2016 “Solid biofuels—Determination of total content of sulfur and chlorine” [33] |

| 9 | Oxygen determination (status: Odaf—dry ash-free) | Subtraction method | ISO/TS 20048-1:2020 “Solid biofuels—Determination of off-gassing and oxygen depletion characteristics” [34] |

| Fuels | Wr | Wa | Ad | Vdaf | Cdaf | Hdaf | Ndaf | Sdaf | Odaf | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | MJ/kg | ||||||||||

| SS | 35.2 | 7.1 | 44.5 | 83.5 | 55.1 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 1.4 | 32.2 | 9.6 | 22.7 |

| LP | 19.0 | 6.2 | 45.5 | 70.3 | 63.9 | 4.1 | 0 | 3.8 | 28.2 | 11.4 | 23.2 |

| LB | 9.4 | 5.5 | 46.4 | 72.0 | 65.0 | 4.2 | 0 | 4.0 | 28.8 | 12.2 | 23.1 |

| Chemical Composition% | Sewage Sludge | Lignin |

|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 45.2 | 22.3 |

| Al2O3 | 5.26 | 2.44 |

| Fe2O3 | 10.7 | 12.5 |

| CaO | 11.4 | 27.4 |

| MgO | - | - |

| TiO2 | 1.71 | 1.55 |

| K2O | 1.98 | 1.82 |

| P2O5 | 17.5 | 2.67 |

| ZnO | 0.17 | - |

| Fuels | Ti | TR | Tb | TDSC | Rmax | DSCmax | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | %/min | mW/mg | min−2 °C−3 | ||||

| SS | 262.1 | 323.0 | 585.4 | 331.8 | 2.22 | 4.3 | 1.02 |

| LP | 291.8 | 372.1 | 561.0 | 372.0 | 2.60 | 6.9 | 1.11 |

| SS75% + LP25% | 256.5 | 324.1 | 595.1 | 337.0 | 1.87 | 4.2 | 0.68 |

| SS50% + LP50% | 267.2 | 330.9 | 582.9 | 347.3 | 1.93 | 4.8 | 0.69 |

| SS25% + LP75% | 284.8 | 364.3 | 572.5 | 367.3 | 2.19 | 5.8 | 0.84 |

| LB | 290.0 | 373.9 | 592.2 | 367.0 | 2.56 | 6.8 | 1.12 |

| SS75% + LB25% | 251.4 | 321.4 | 586.5 | 331.0 | 2.05 | 4.5 | 0.89 |

| SS50% + LB50% | 273.0 | 326.0 | 601.7 | 351.0 | 1.85 | 4.8 | 0.61 |

| SS25% + LB75% | 276.3 | 366.1 | 573.8 | 359.0 | 2.27 | 5.7 | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhuikov, A.; Pyanykh, T.; Kolosov, M.; Grishina, I.; Fetisova, O.; Kuznetsov, P.; Chicherin, S. Study of Co-Combustion of Pellets and Briquettes from Lignin in a Mixture with Sewage Sludge. Energies 2026, 19, 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020397

Zhuikov A, Pyanykh T, Kolosov M, Grishina I, Fetisova O, Kuznetsov P, Chicherin S. Study of Co-Combustion of Pellets and Briquettes from Lignin in a Mixture with Sewage Sludge. Energies. 2026; 19(2):397. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020397

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhuikov, Andrey, Tatyana Pyanykh, Mikhail Kolosov, Irina Grishina, Olga Fetisova, Petr Kuznetsov, and Stanislav Chicherin. 2026. "Study of Co-Combustion of Pellets and Briquettes from Lignin in a Mixture with Sewage Sludge" Energies 19, no. 2: 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020397

APA StyleZhuikov, A., Pyanykh, T., Kolosov, M., Grishina, I., Fetisova, O., Kuznetsov, P., & Chicherin, S. (2026). Study of Co-Combustion of Pellets and Briquettes from Lignin in a Mixture with Sewage Sludge. Energies, 19(2), 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020397