Constrained and Unconstrained Control Design of Electromagnetic Levitation System with Integral Robust–Optimal Sliding Mode Control for Mismatched Uncertainties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contribution and Article Structure

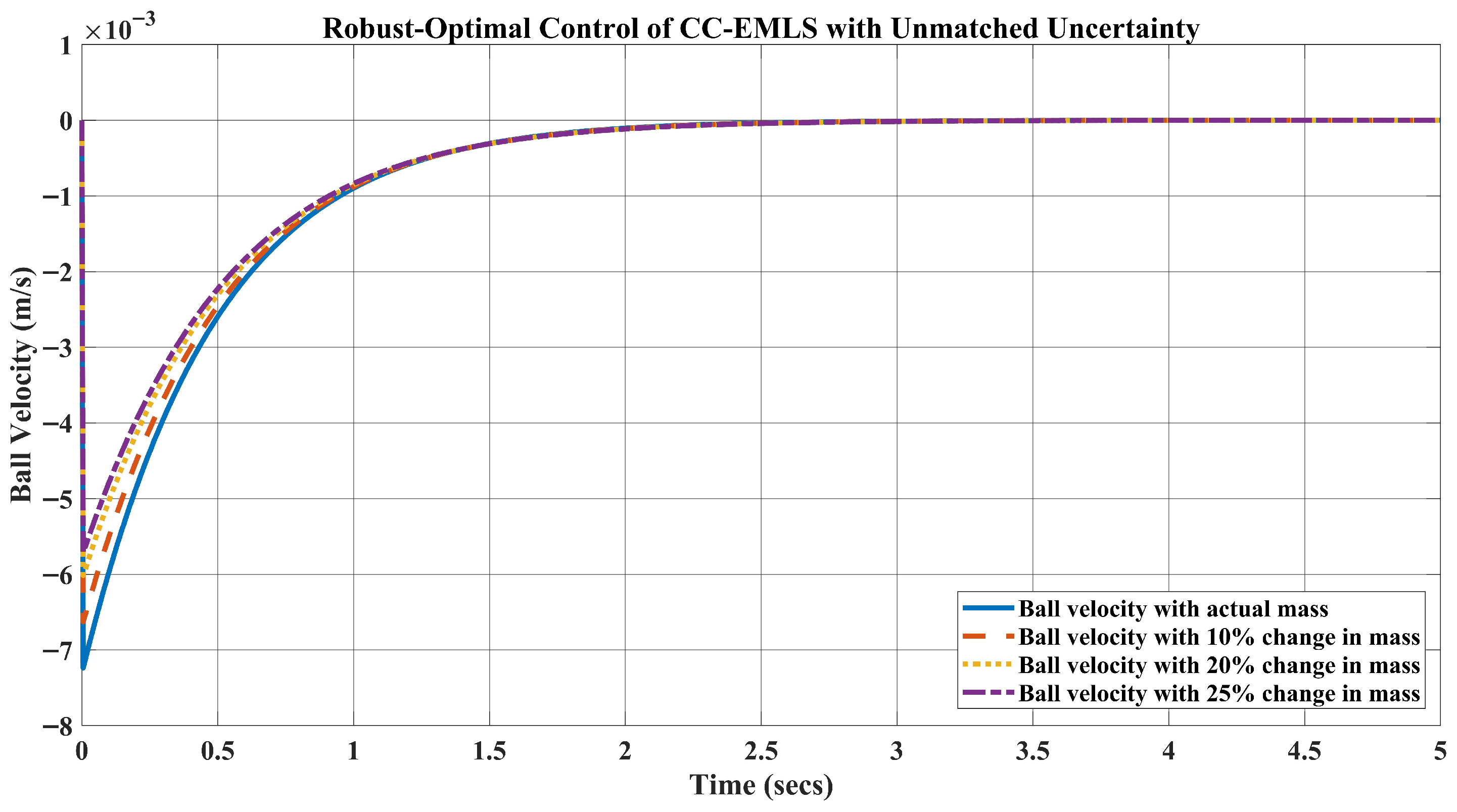

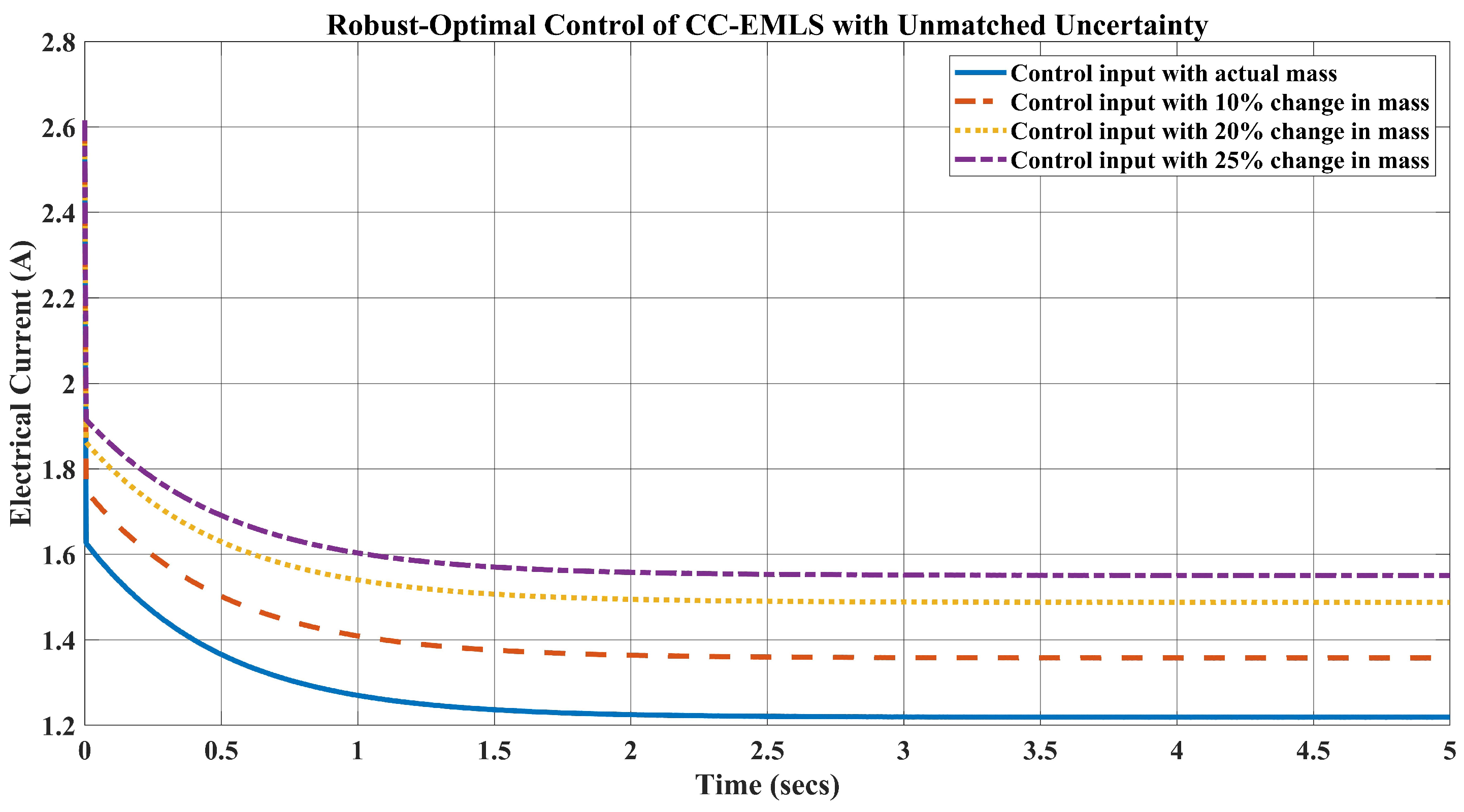

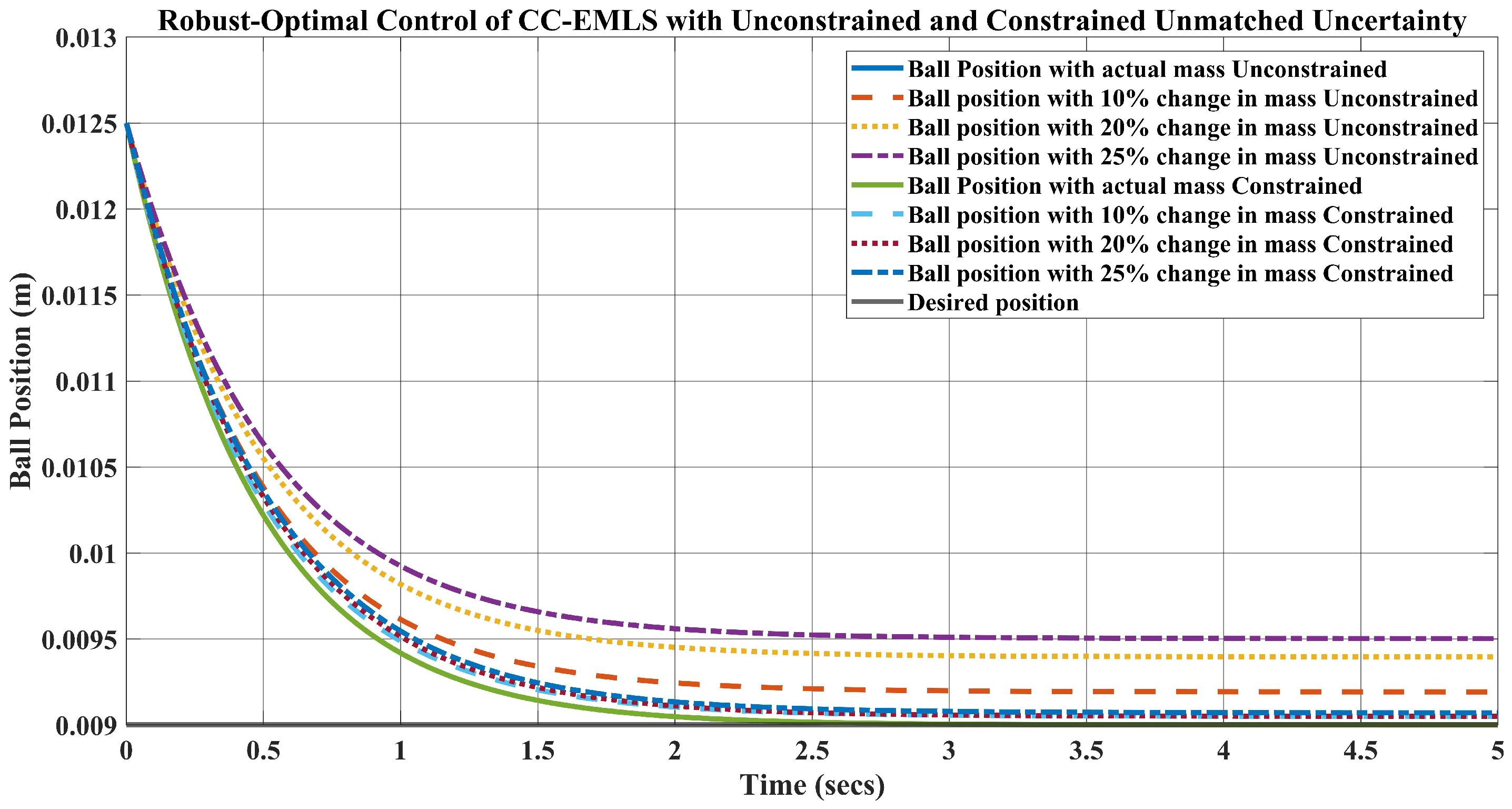

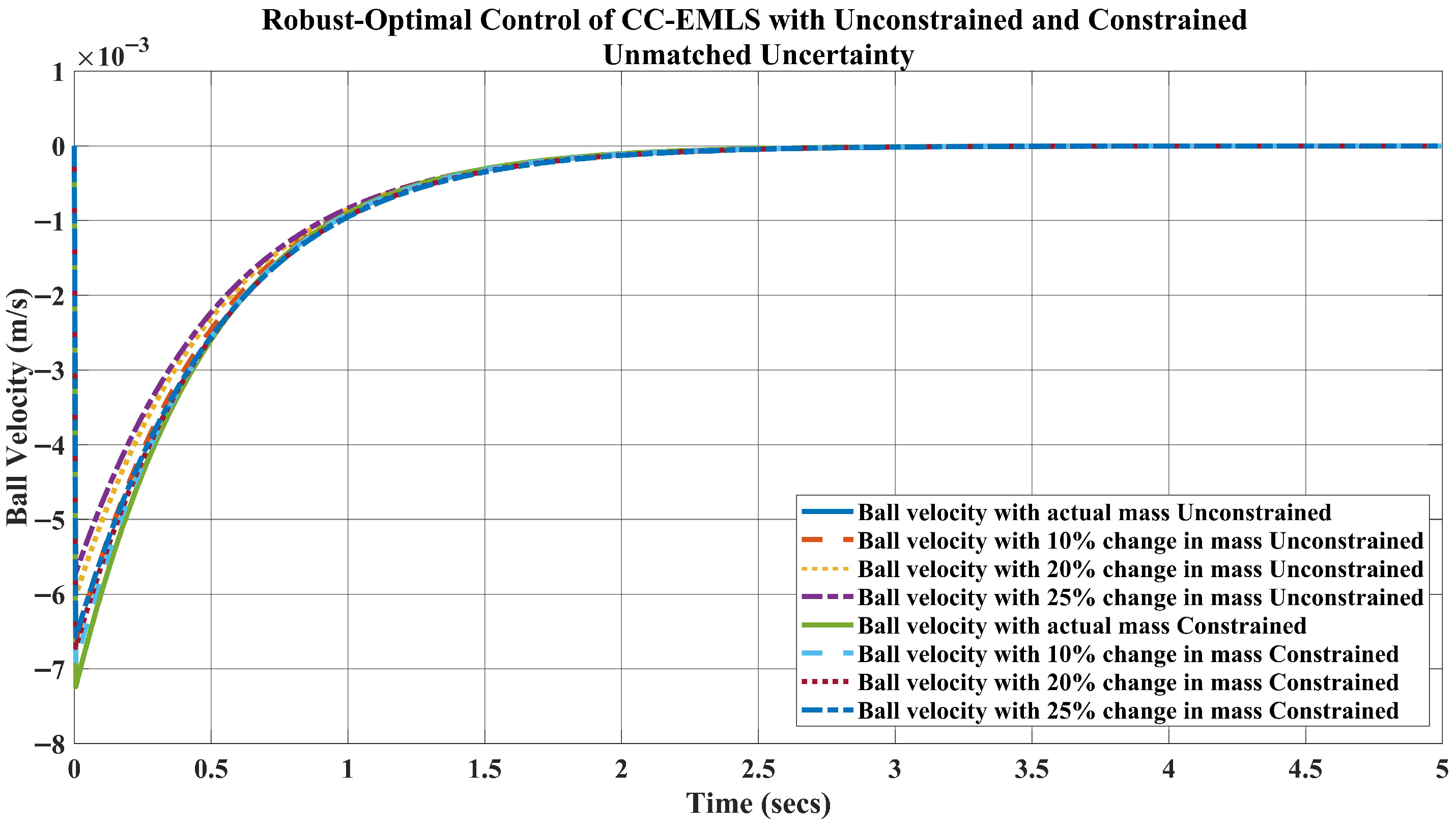

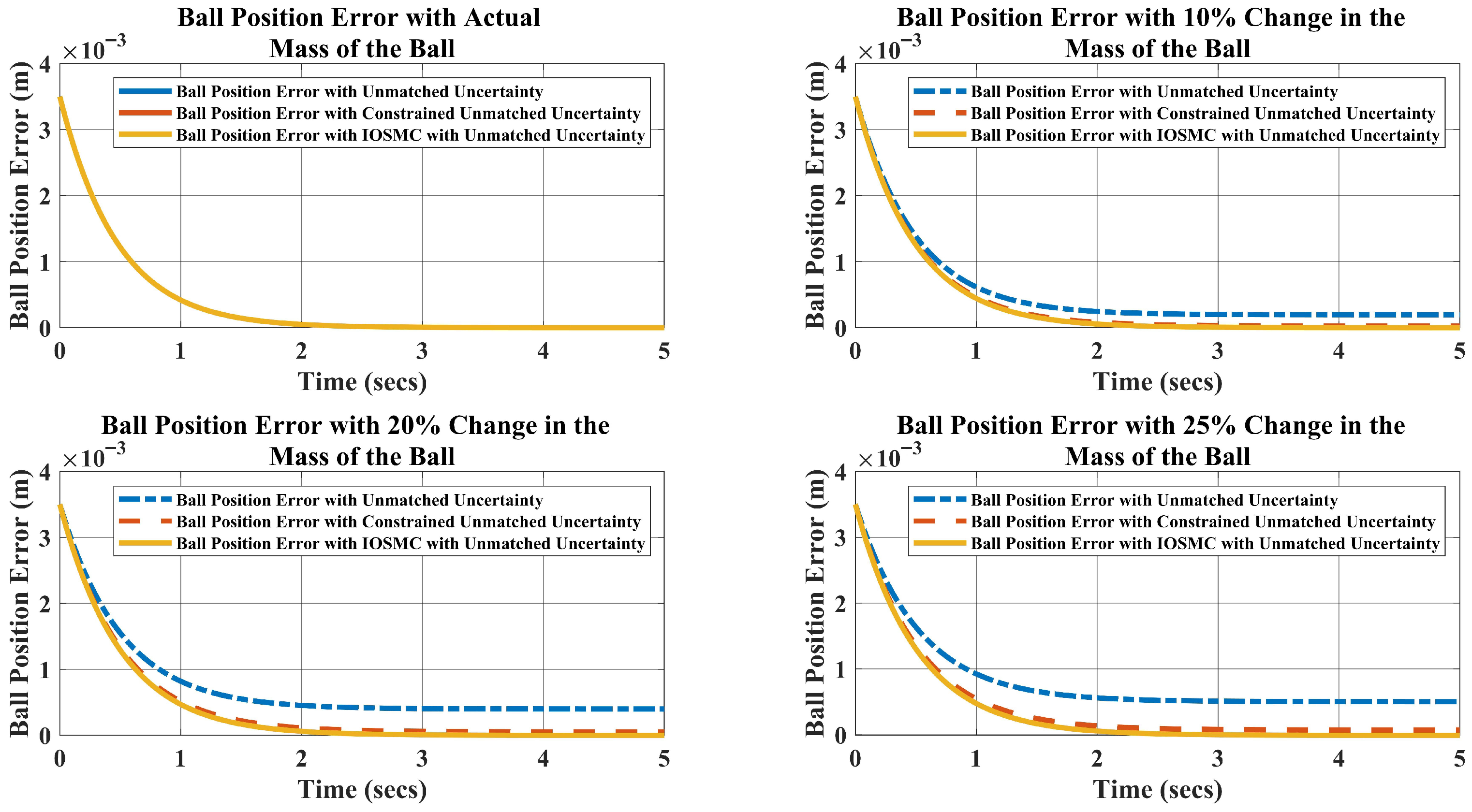

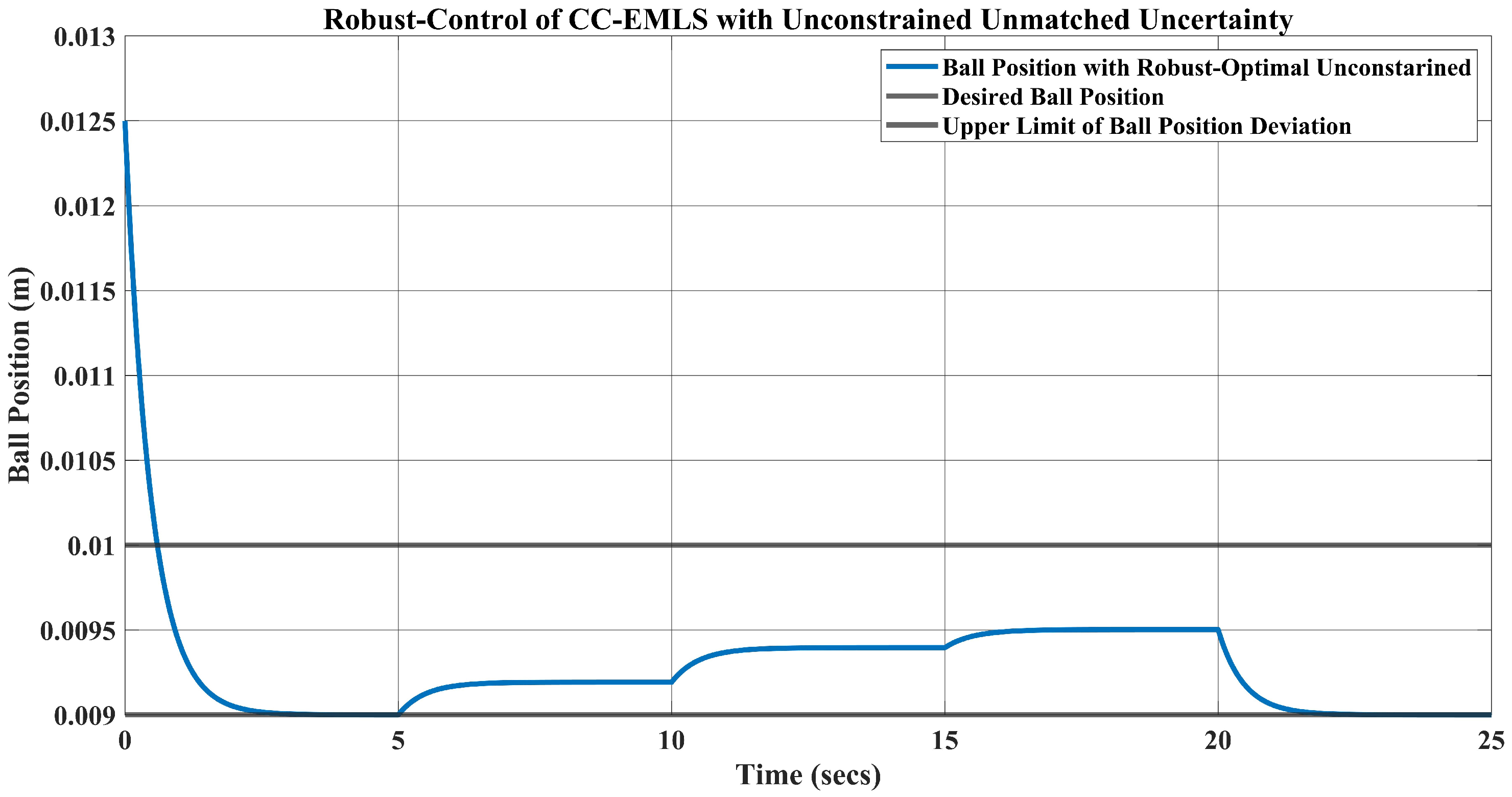

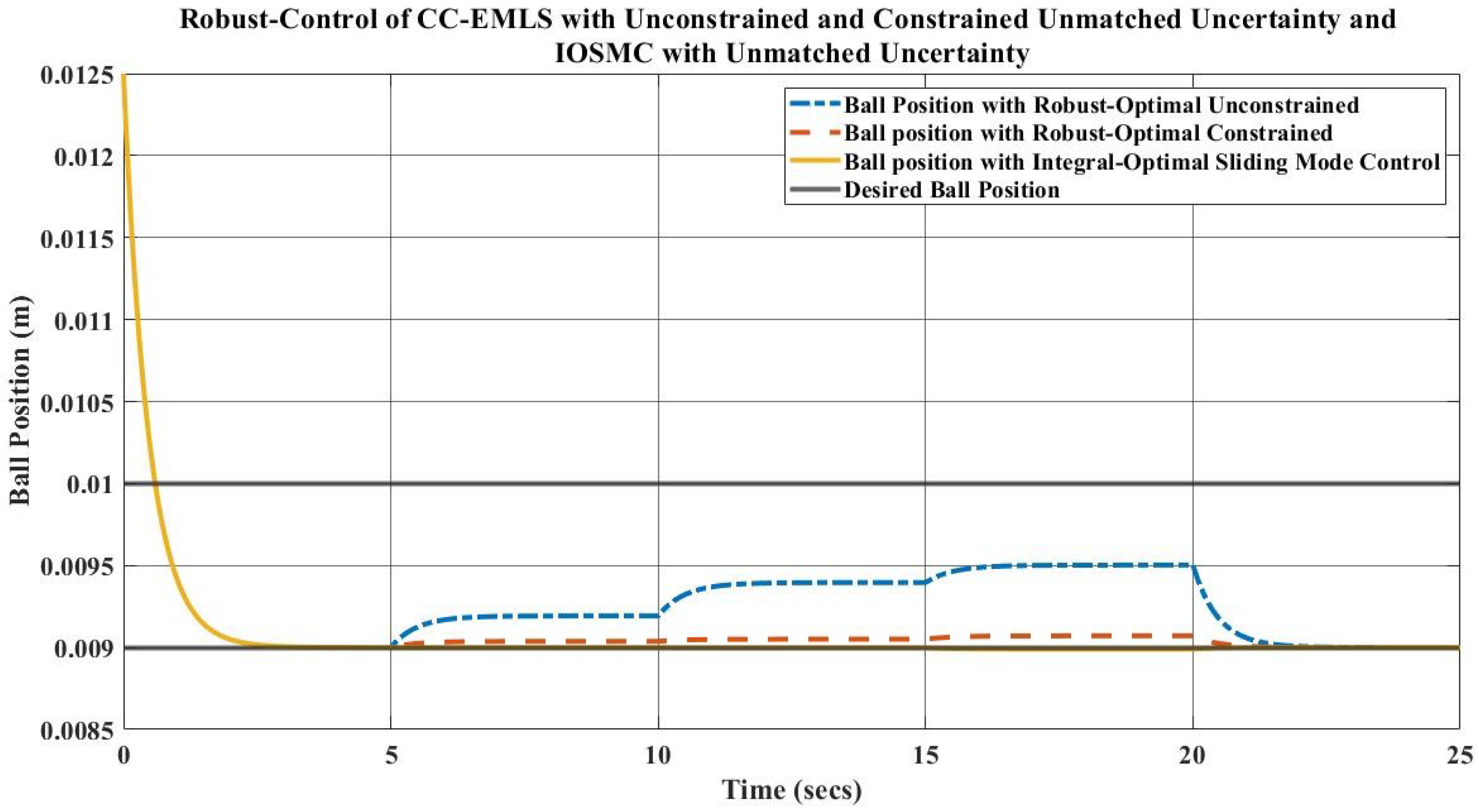

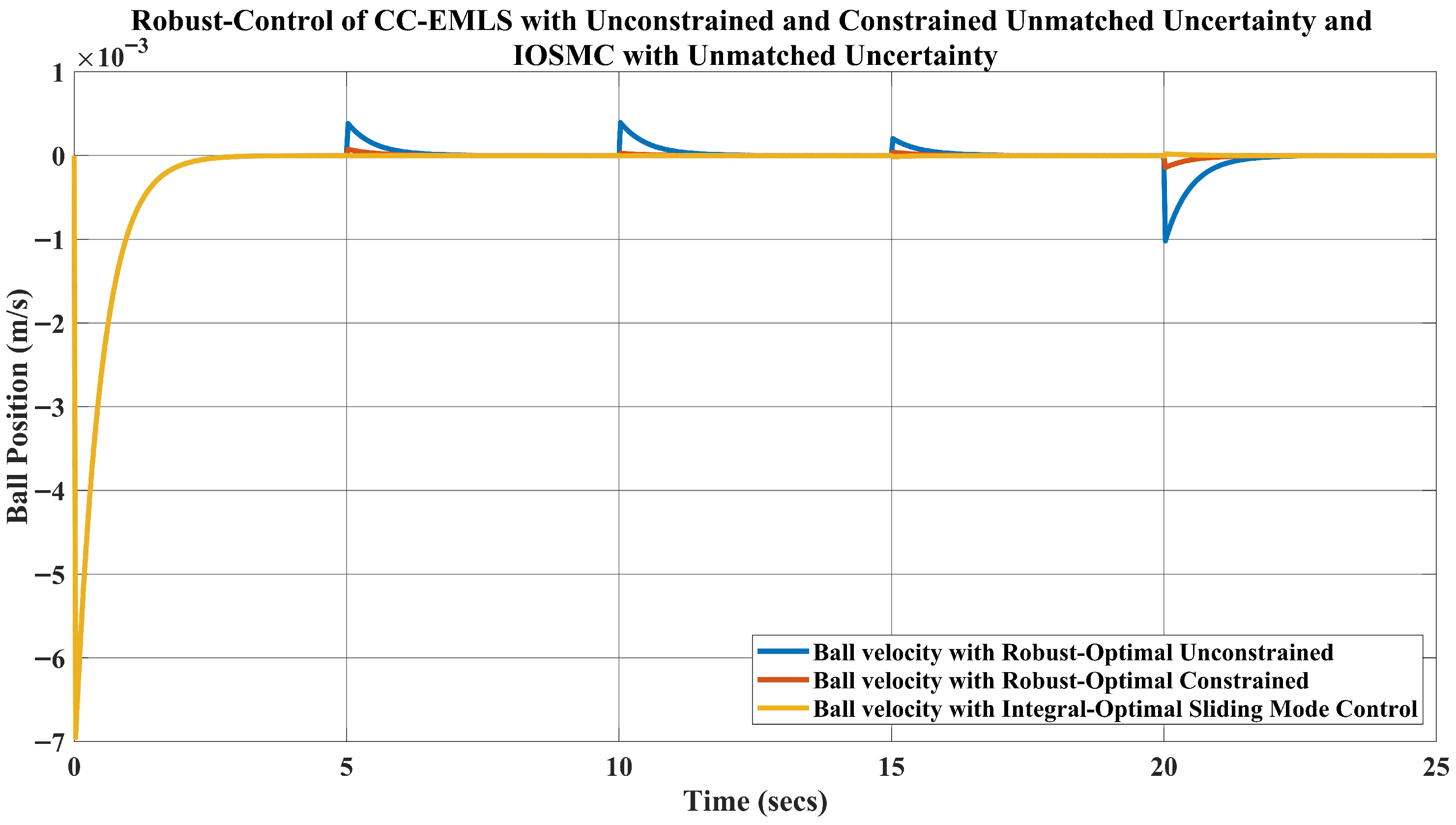

- Due to nonlinear nature of levitation system, initially a robust control scheme based on the optimal control approach with unconstrained mismatched uncertainties is introduced for CC-EMLS, utilizing a quadratic performance function solved via the HJB equation, with stability confirmed using the Lyapunov direct method.

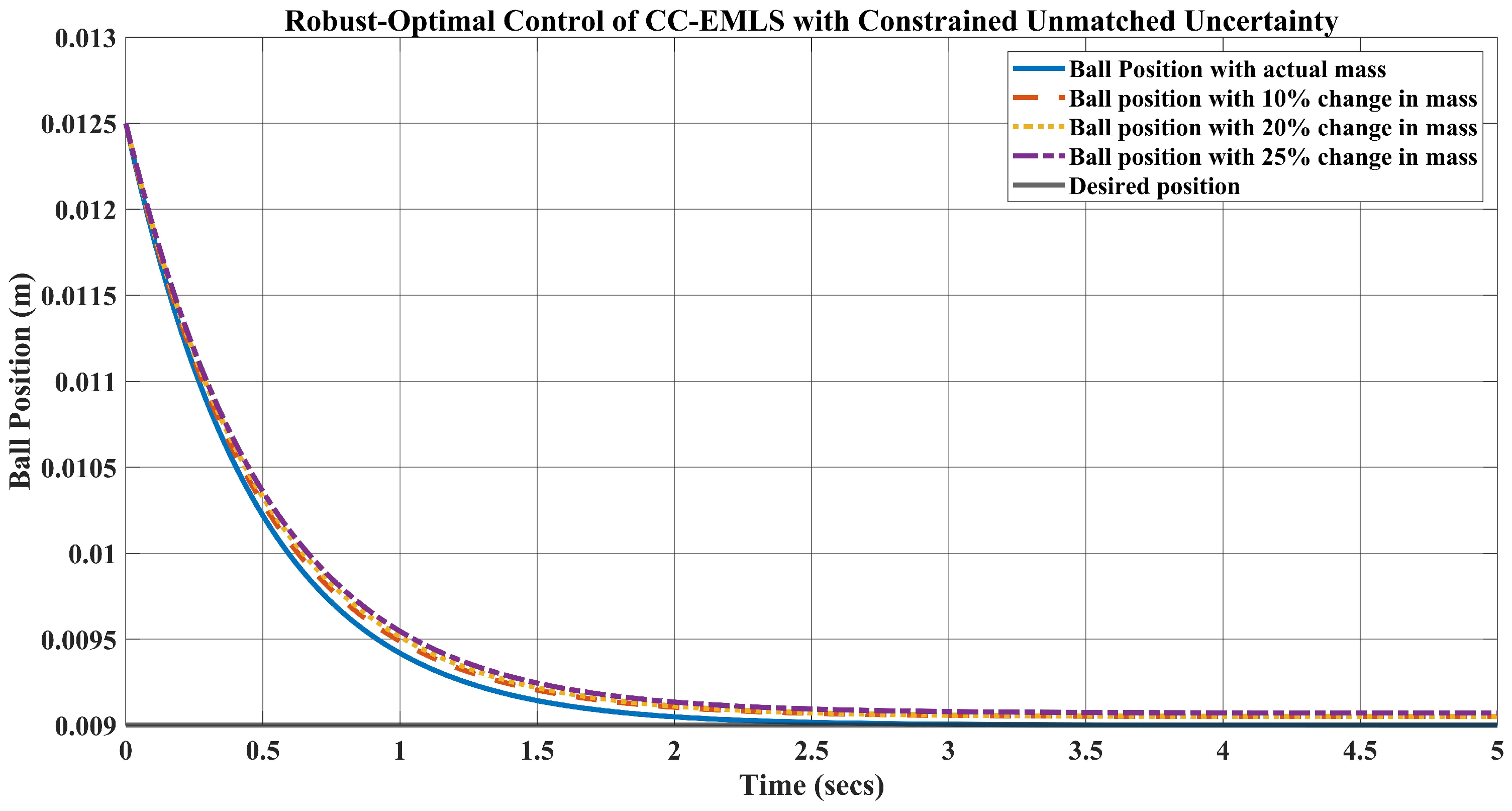

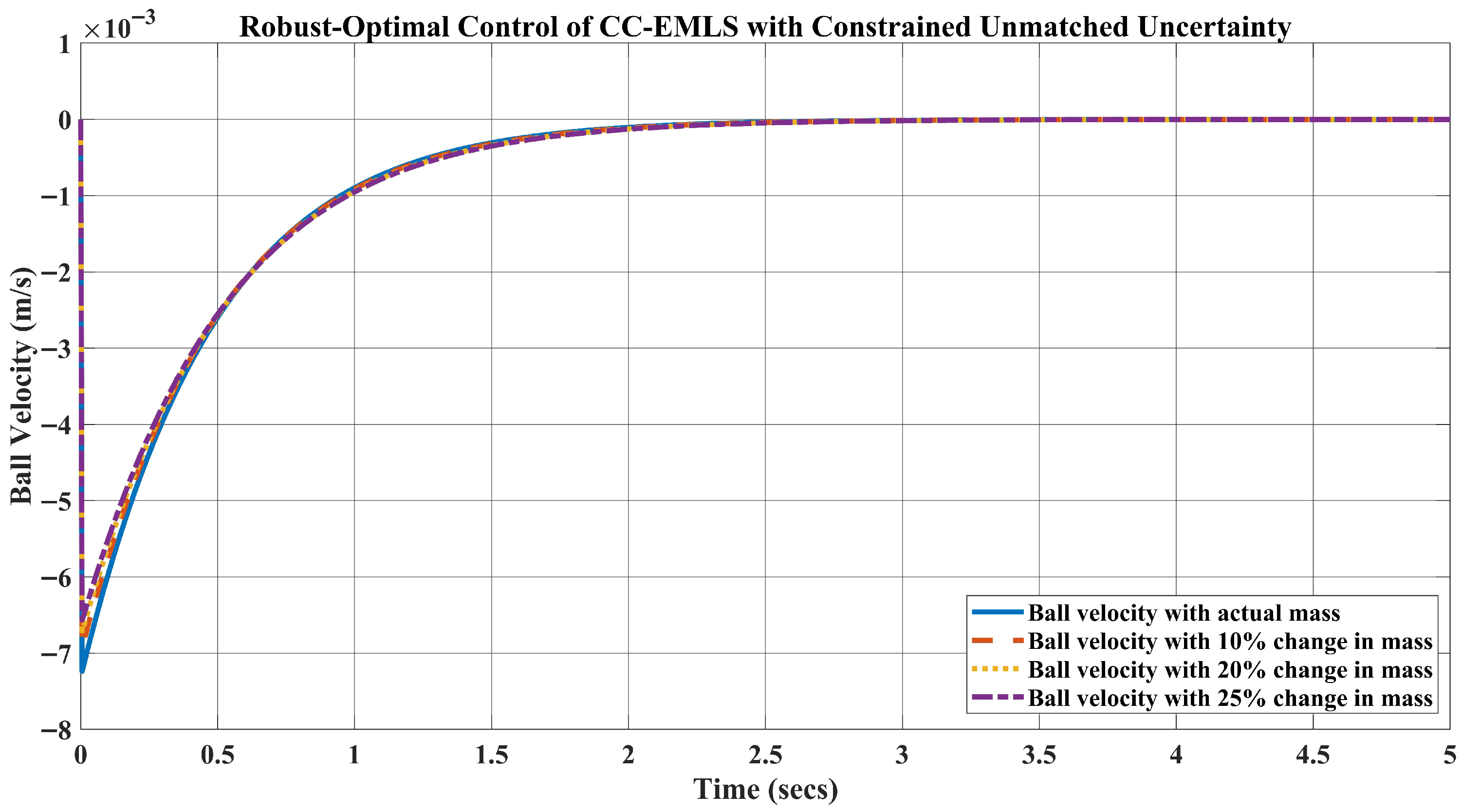

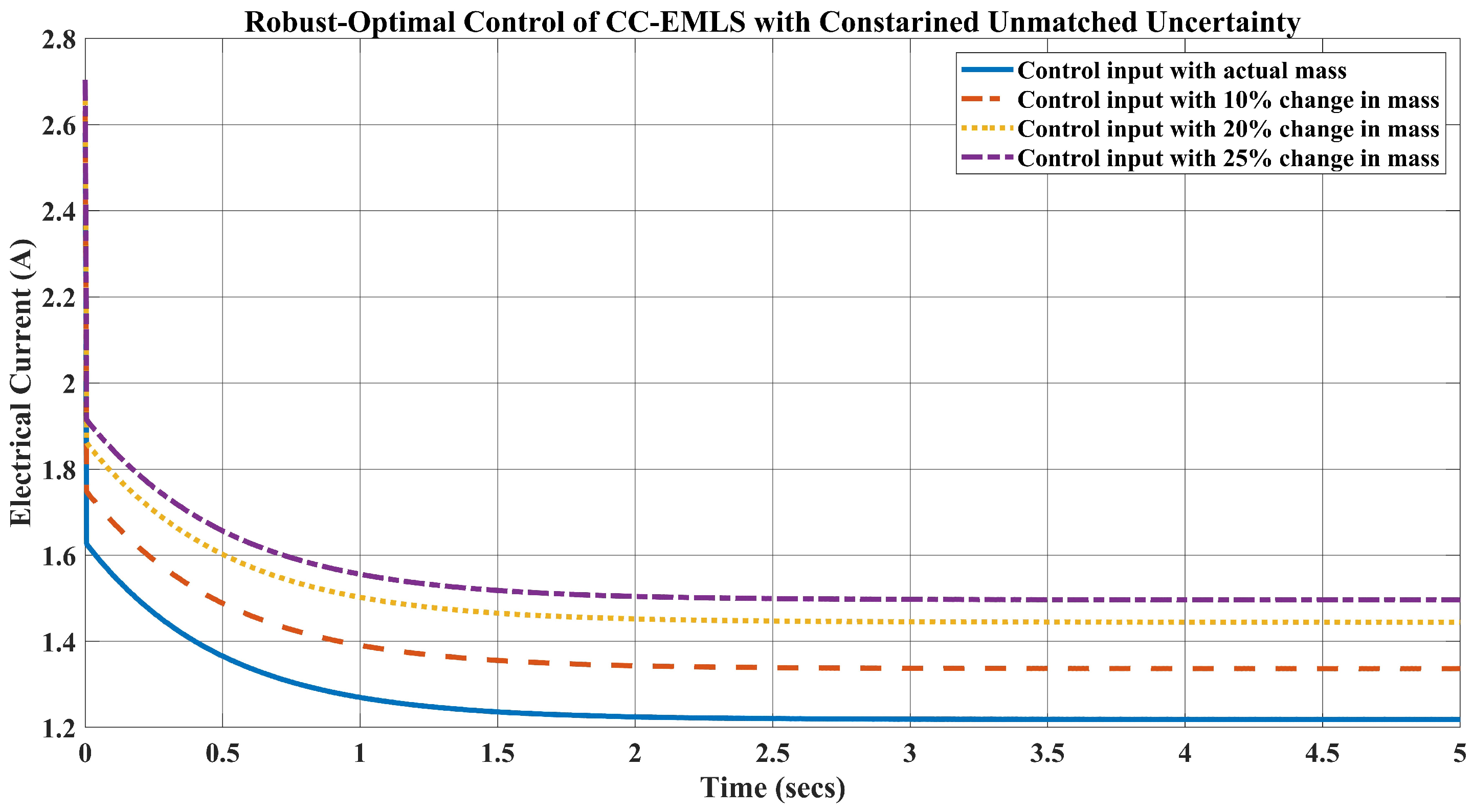

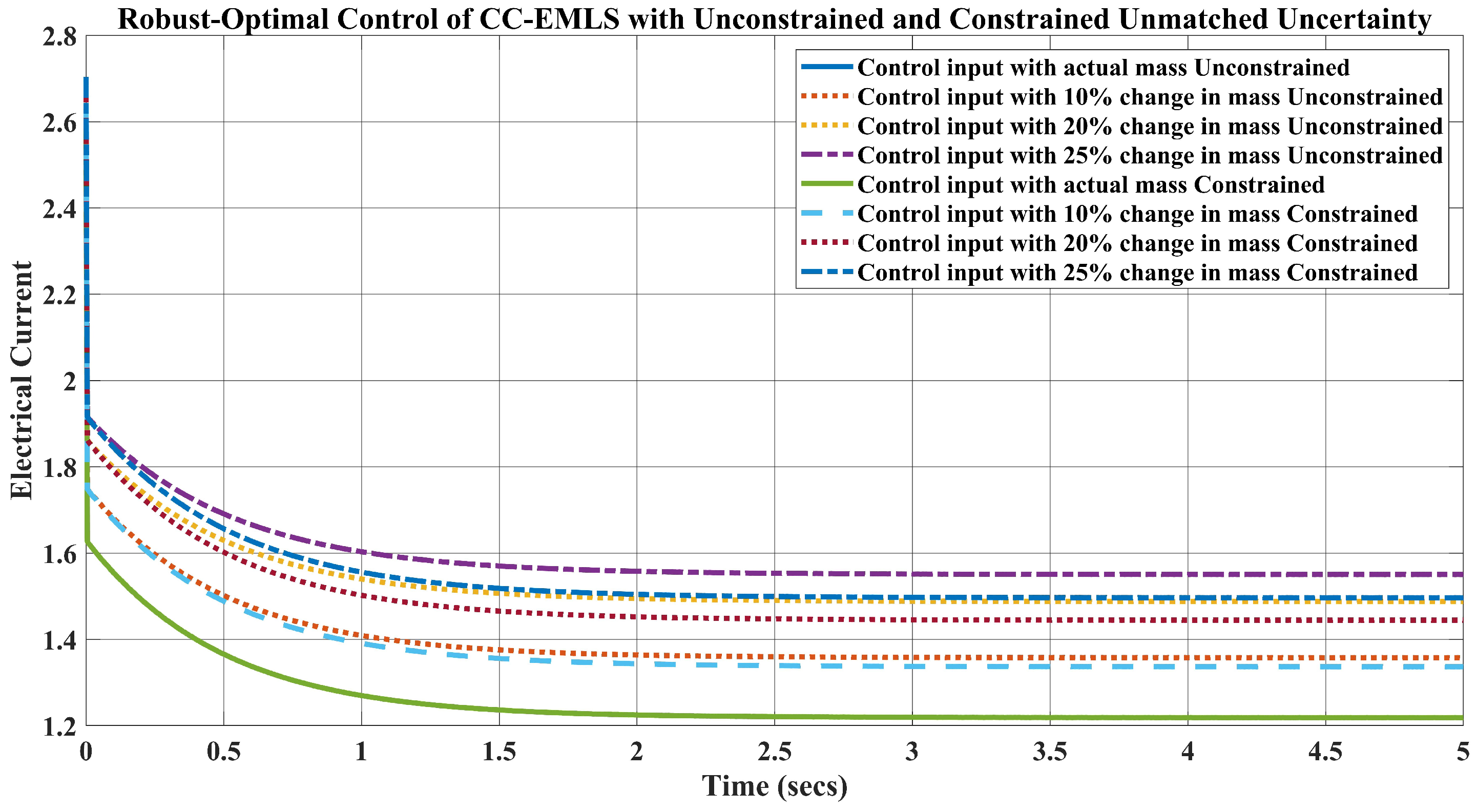

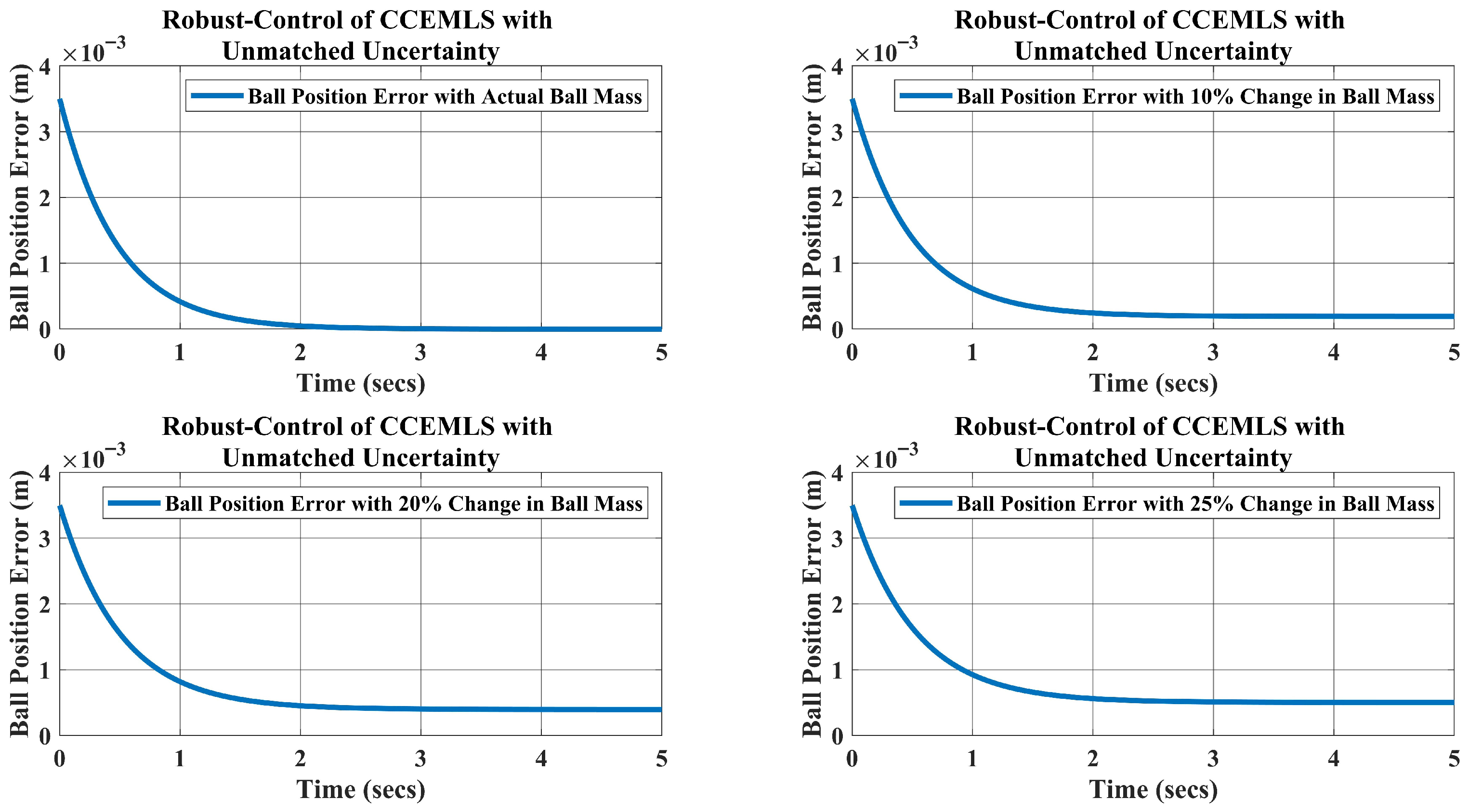

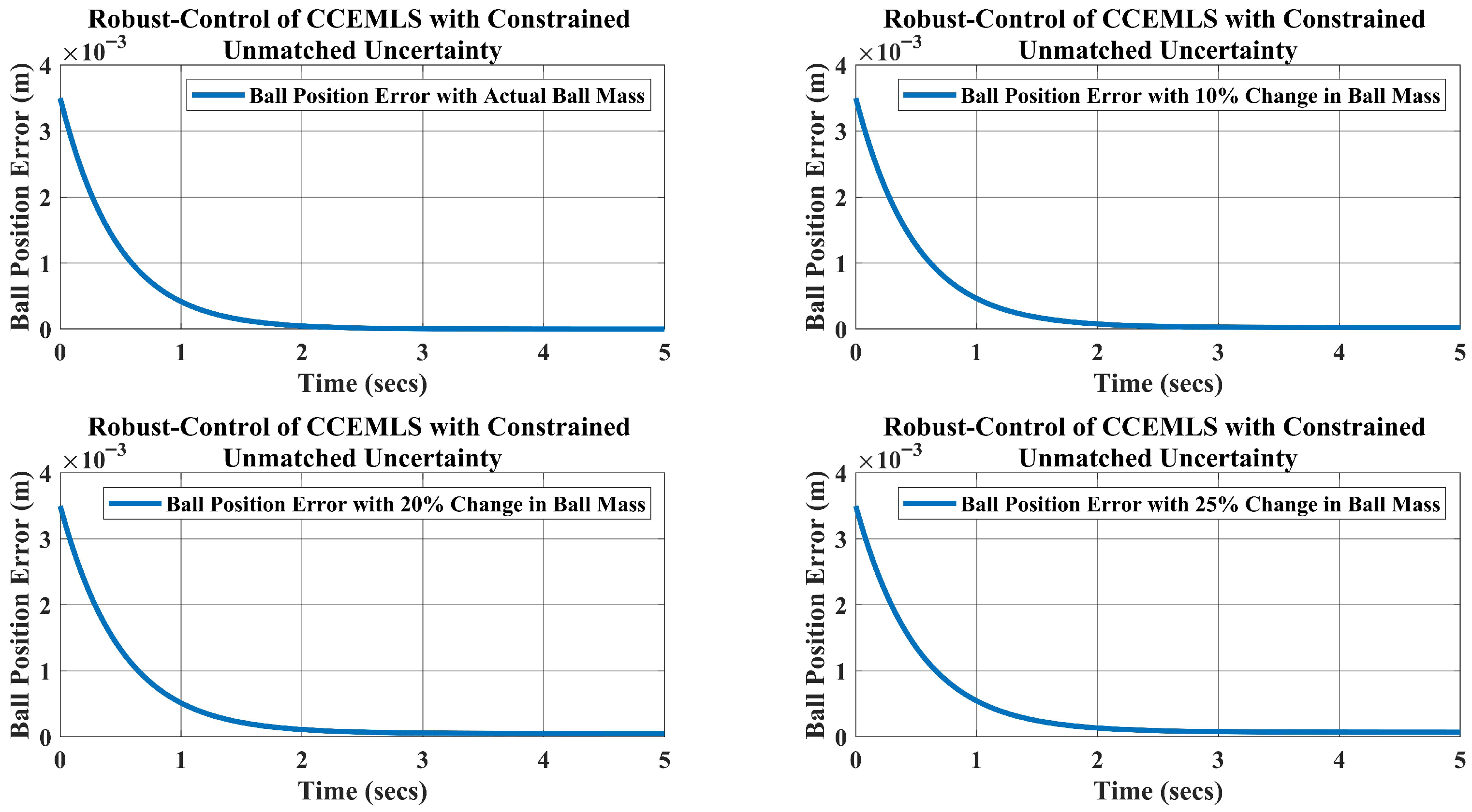

- The designed controller is effective against uncertainties; however, it faces steady-state errors at higher uncertainties levels. Therefore, a constrained-based approach with a non-quadratic cost function is proposed to address this issue, enhancing robustness and stability while requiring less control effort.

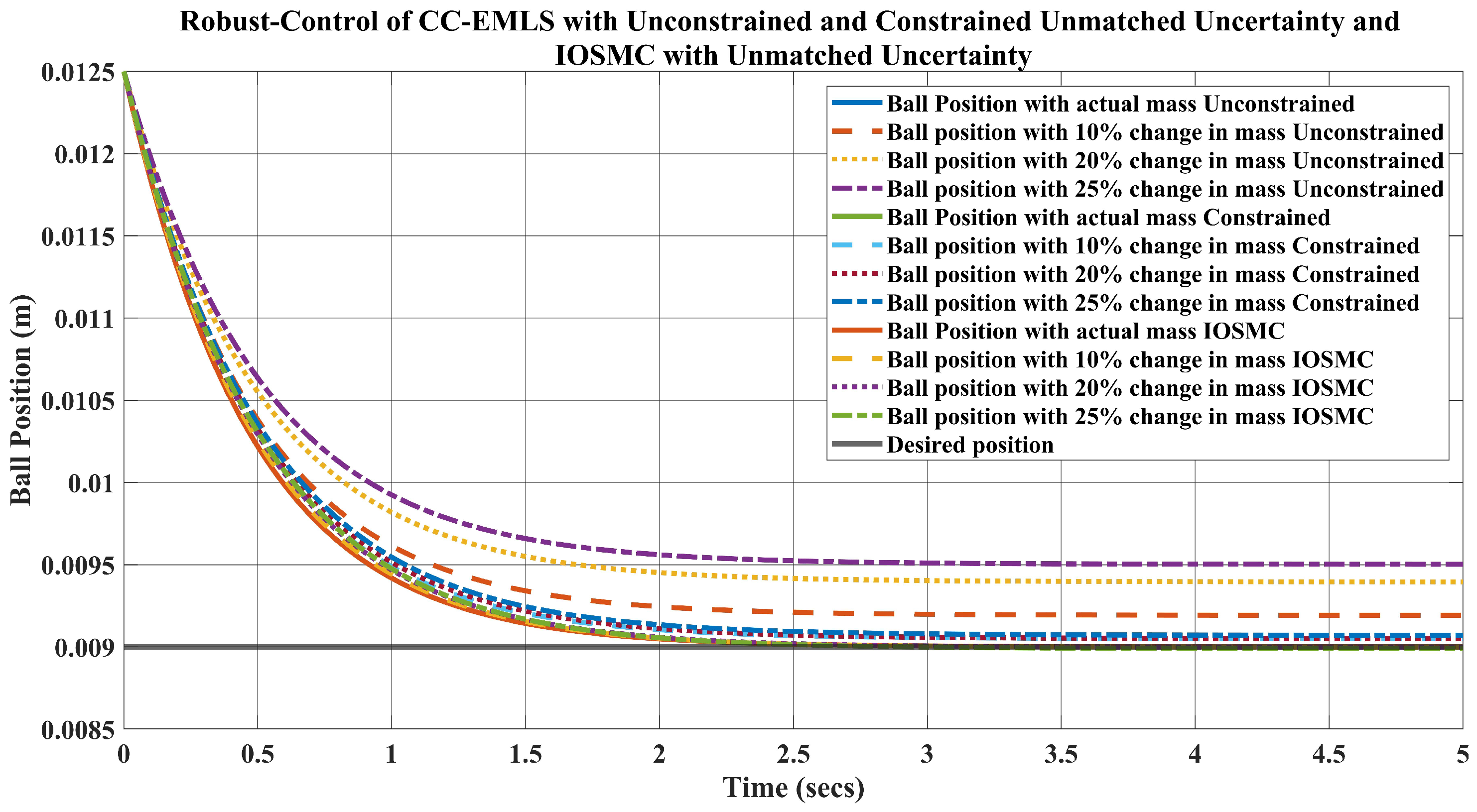

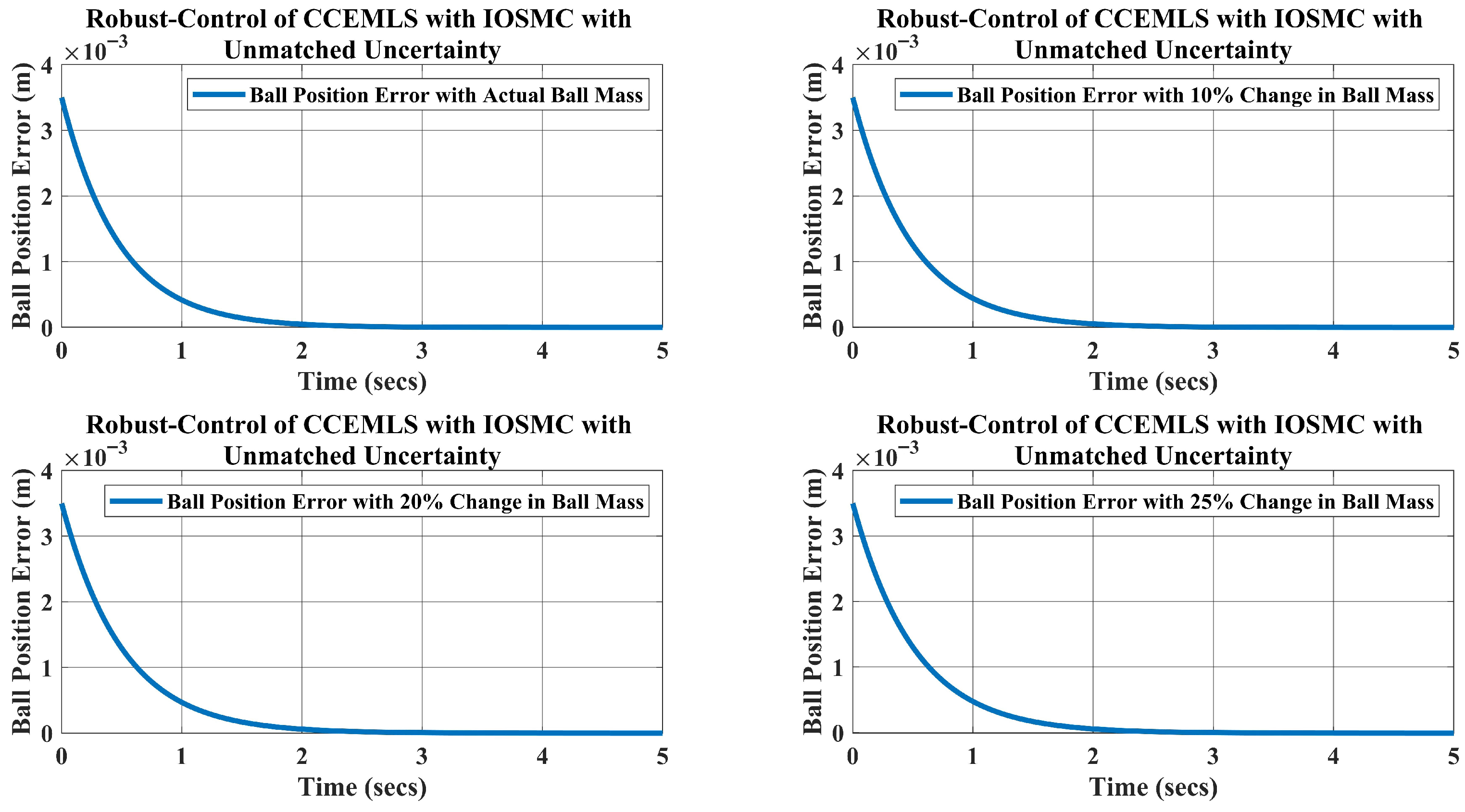

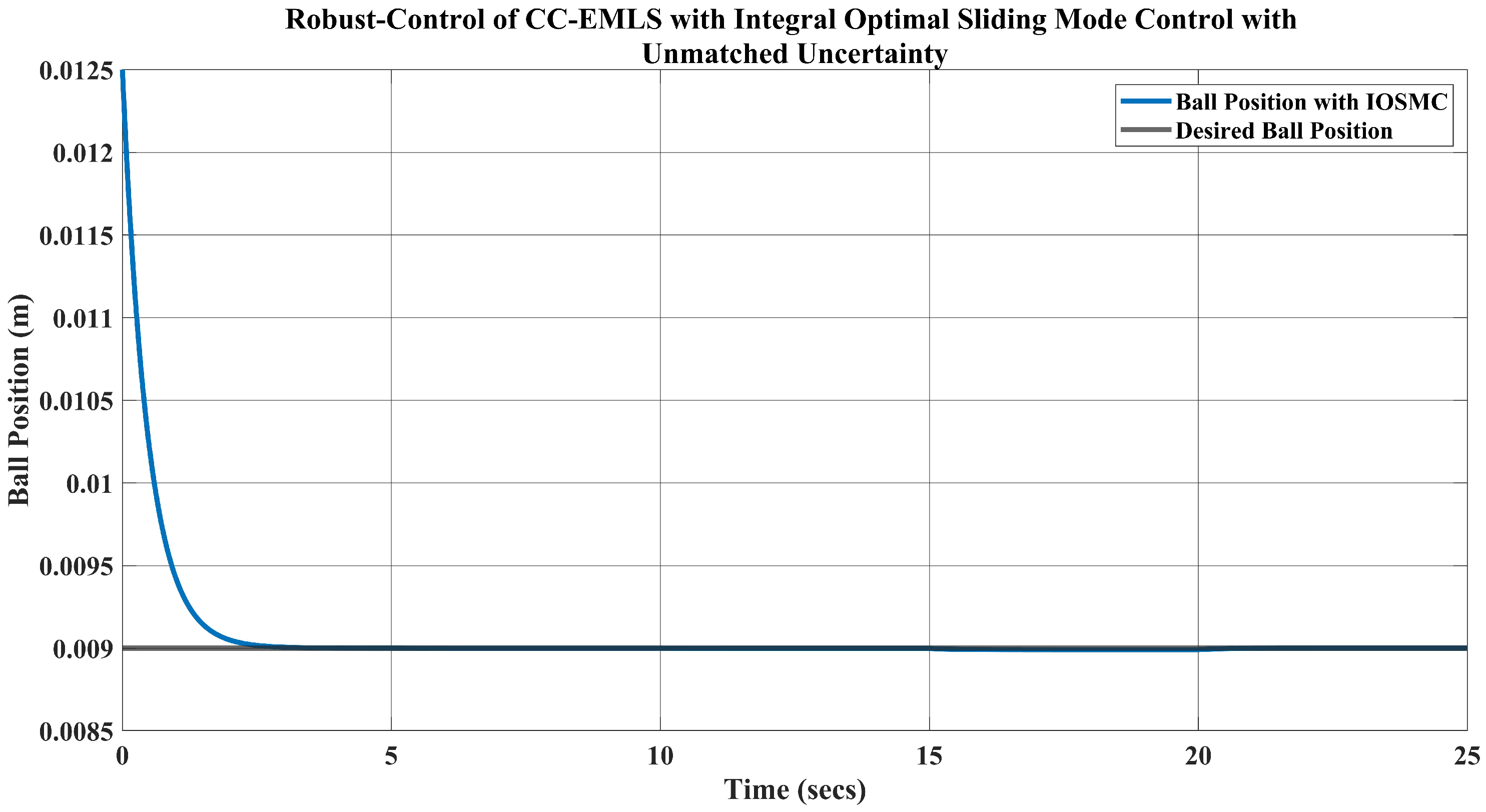

- Nevertheless, the problem of steady-state error remains partially unsolved in the constrained-based robust–optimal control outline for CC-EMLS with mismatched uncertainties. To address this drawback, an integral sliding mode control scheme is proposed. Since the traditional sliding mode control provides the tracking at the desired set point and robustness against external disturbances, it is fundamentally susceptible to high-frequency chattering, which can affect system stability.

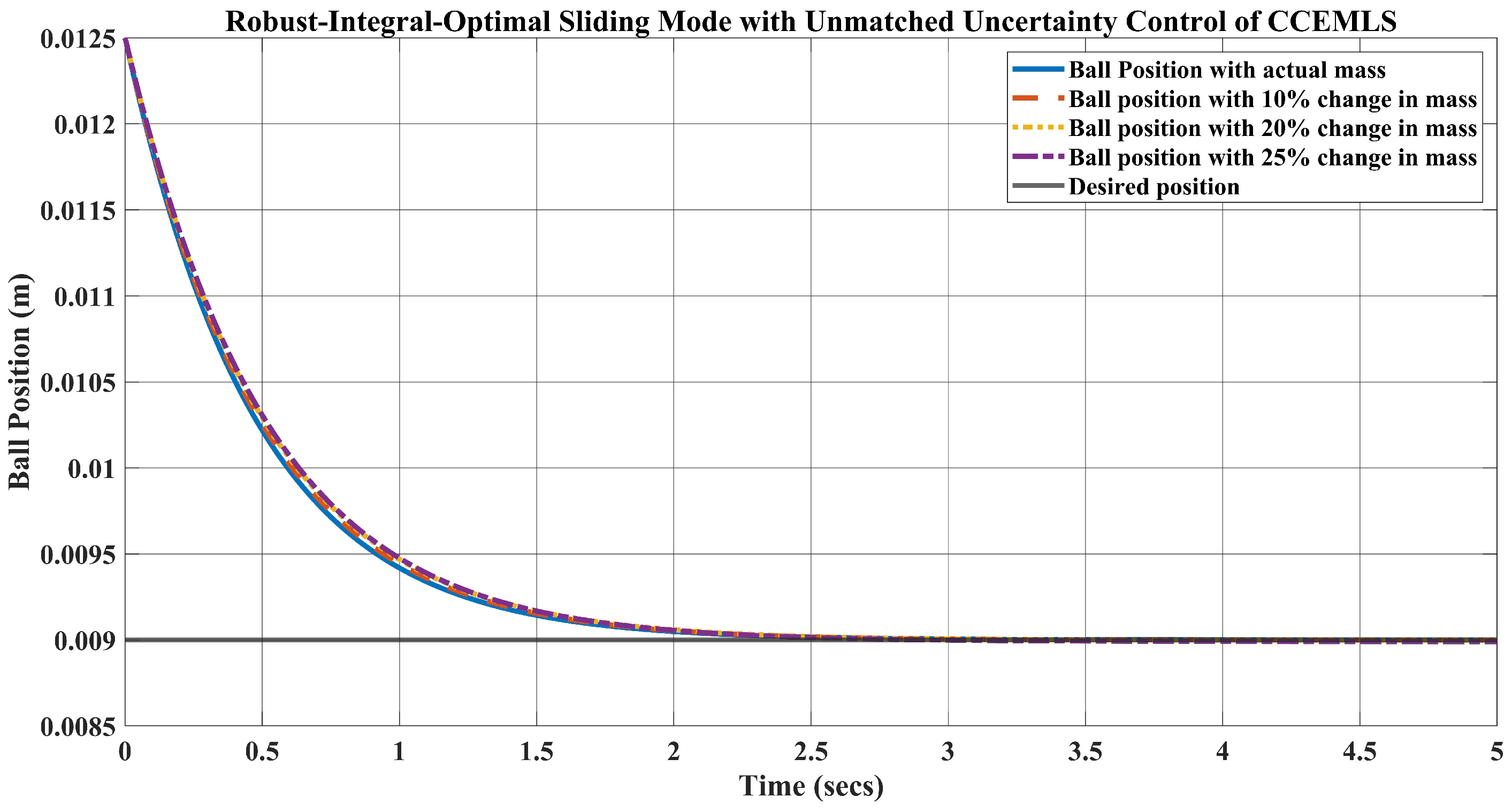

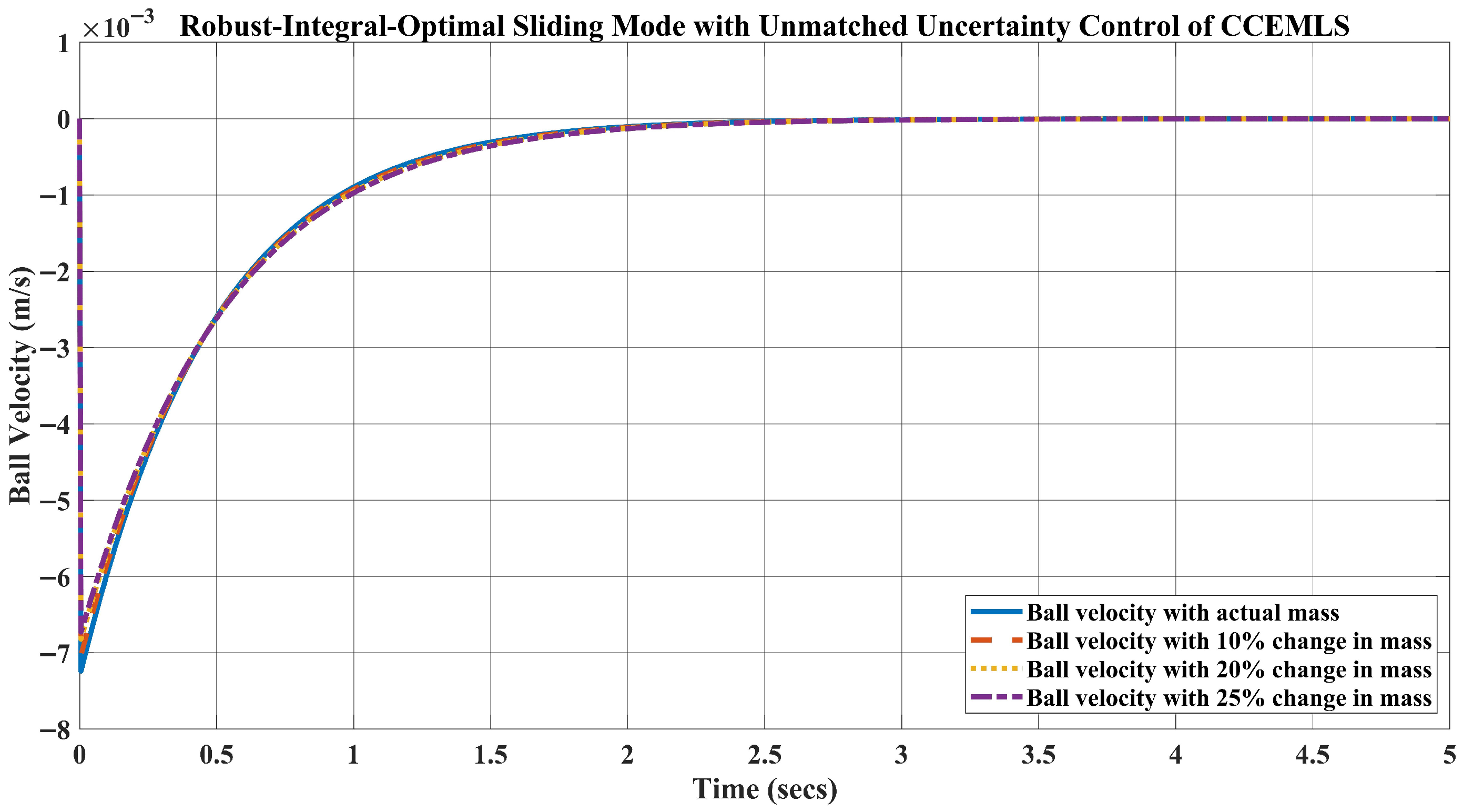

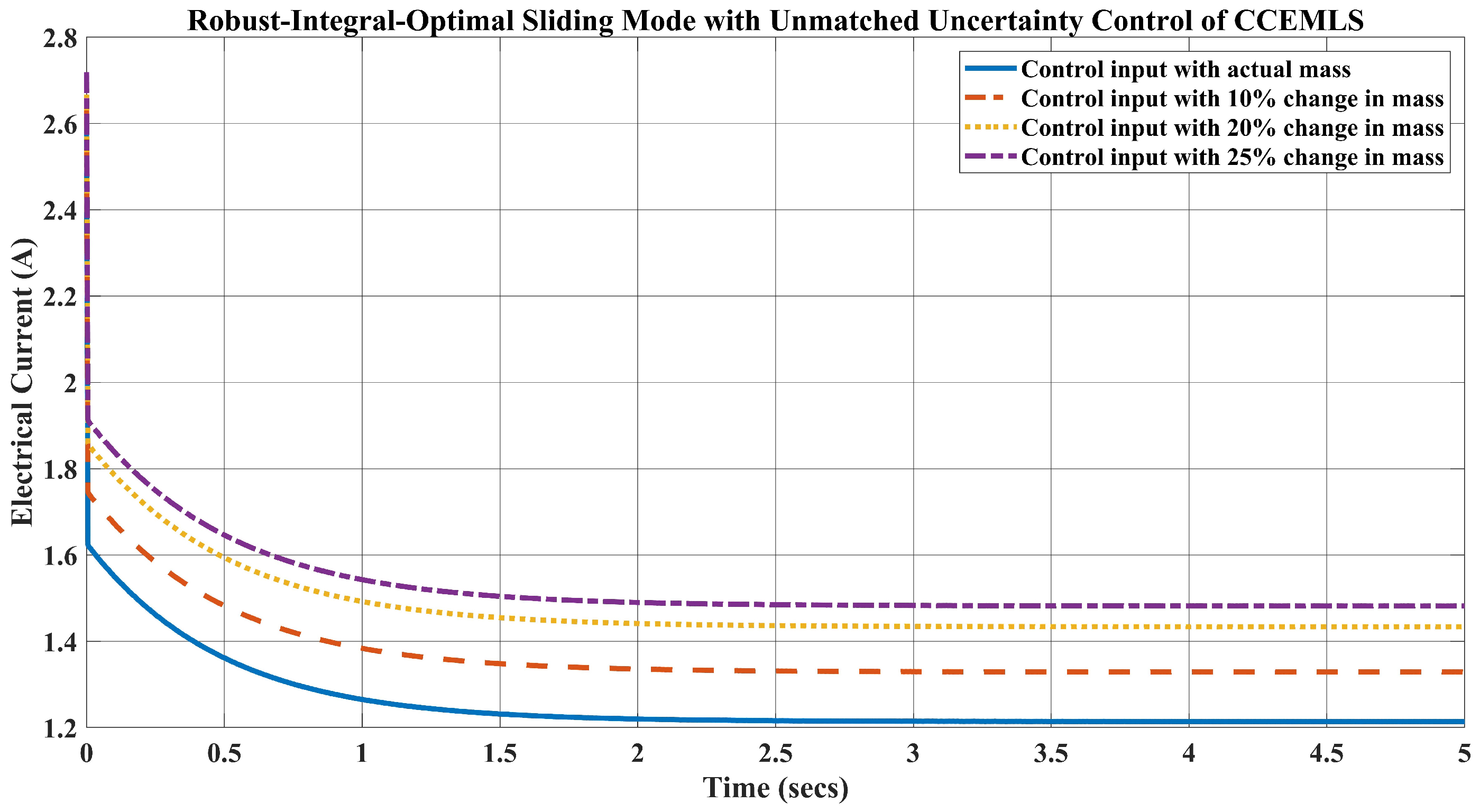

- To overcome the aforementioned limitations, the designed control technique incorporates an integral sliding mode control with a robust–optimal design scheme, where the integral action eliminates the steady-state error from the start and enhances the disturbance rejection capability. The robust–optimal action guarantees optimal performance under parametric variations. This combined approach results in improved transient response, reduced chattering amplitude, and enhanced steady-state accuracy.

- The stability is verified through the Lyapunov method, and the integral error metrics of all three proposed control schemes are compared to highlight their robustness.

3. Model of EMLS

4. Statement of the Problem and Controller Design

4.1. Problem Statement

4.2. Unconstrained Mismatched Uncertainties

4.2.1. Robust Control Challenges with Mismatched Uncertainties of CC-EMLS

4.2.2. Optimal-Control Challenges with Mismatched Uncertainties of CC-EMLS

4.3. Constrained Mismatched Uncertainties

Optimal Control Challenges with Mismatched Uncertainties of CC-EMLS

4.4. Integral Sliding Mode Control with Robust–Optimal Method

5. Simulation Results and Disscusion

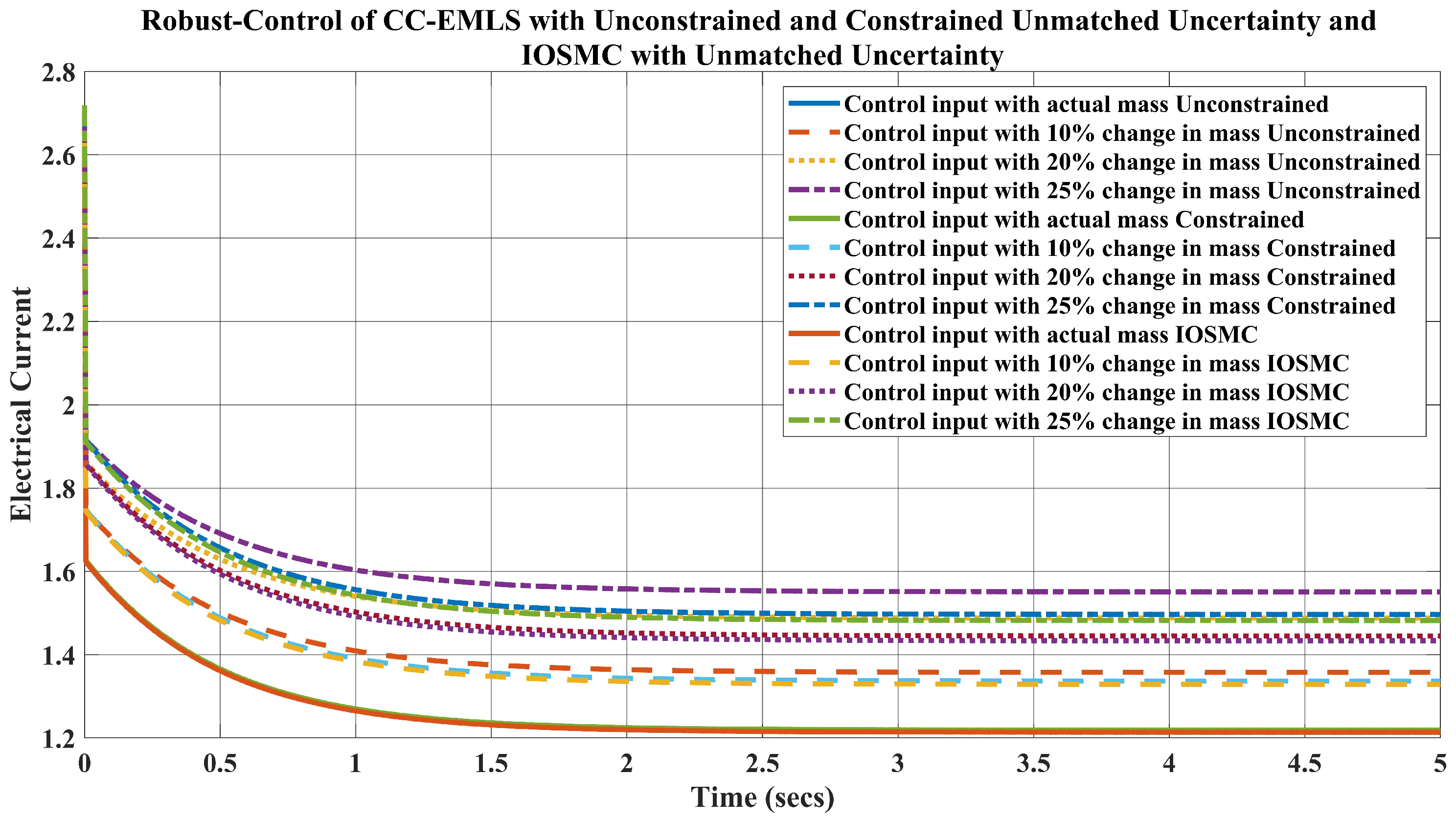

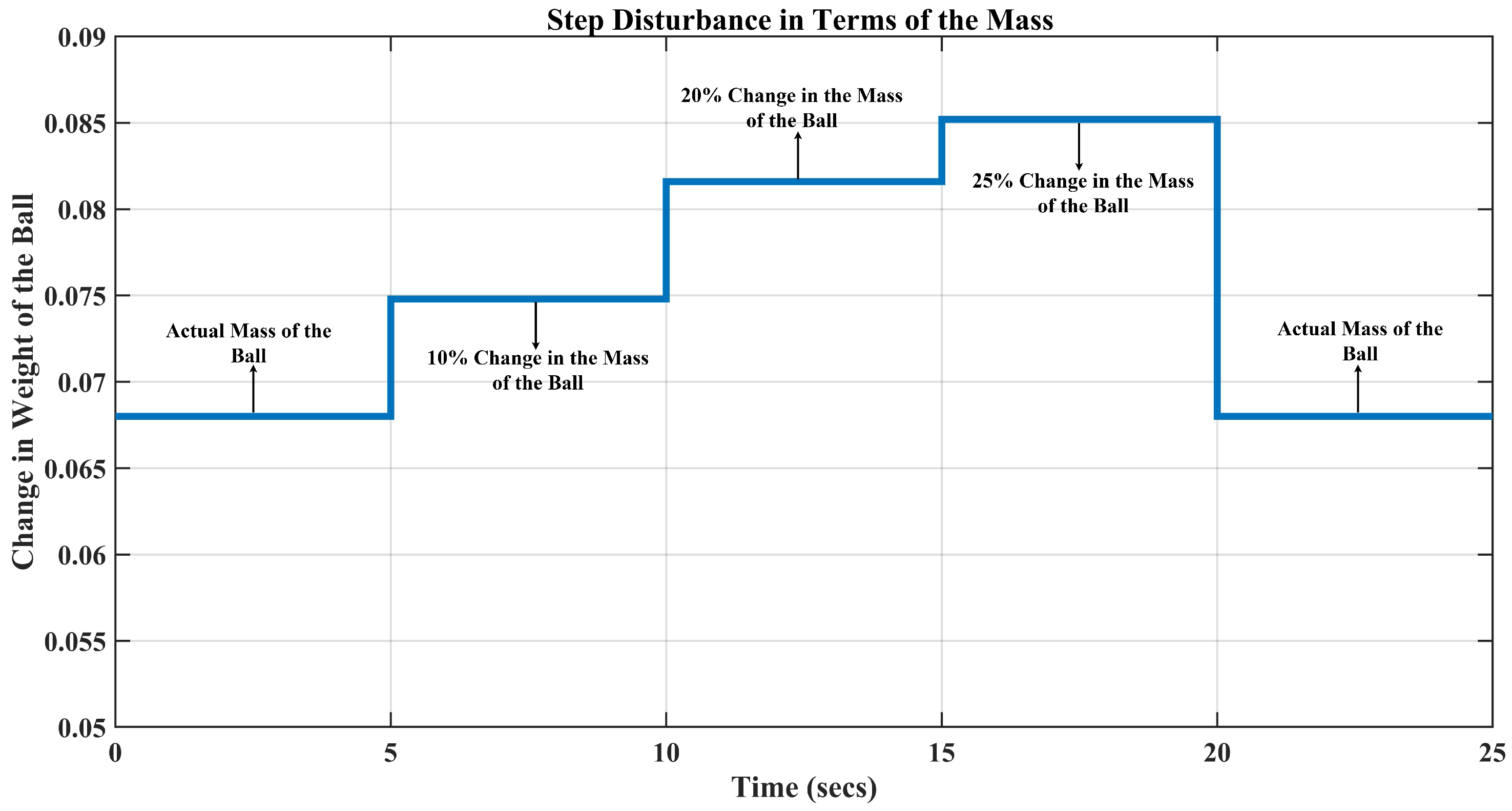

- For the weight kg, which is a change in the mass, the requirement of the current is A to keep the ball levitated at m.

- Likewise, when the weight of the ball is kg, the requirement of the current A.

- Lastly, for the ball’s mass, kg, which is a change in the mass, the current required to lift the object upward at m is A.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adil, H.M.; Ahmed, S.; Ahmad, I. Control of MagLev system using supertwisting and integral backstepping sliding mode algorithm. IEEE Acces. 2020, 8, 51352–51362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Adhyaru, D.M. Control techniques for electromagnetic levitation system: A literature review. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 11, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Qiang, H.; Lin, G. Adaptive neural-fuzzy robust position control scheme for maglev train systems with experimental verification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 8589–8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Gao, D.; Ma, W.; Luo, S.; Qian, Q. Dynamic modeling and adaptive sliding mode control for a maglev train system based on a magnetic flux observer. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 31571–31579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, J.; Ji, W.; Rong, L.; Lin, G. Sliding mode robust adaptive control of maglev vehicle’s nonlinear suspension system based on flexible track: Design and experiment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41874–41884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Robust air-gap control of superconducting-hybrid MagLev intelligent conveyor system in smart factory. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.R.; Fiske, J.; Ricci, K.; Ricci, M. Analysis of levitational systems for a superconducting launch ring. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2007, 17, 2117–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, H. The most important maglev applications. J. Eng. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.K.; Banerjee, S. DSP based implementation of piecewise linear control scheme for wide air-gap control of an electromagnetic levitation system. In Proceedings of the IECON 2015-41st Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Yokohama, Japan, 9–12 November 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1223–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahzadeh, M.; Asadi, M.B.; Pourgholi, M. Ekf-based fuzzy sliding mode control using neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Tabriz, Iran, 4–6 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Winursito, A.; Pratama, G.N. LQR state feedback controller with precompensator for magnetic levitation system. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2111, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, R.; Sira-Ramírez, H. Trajectory tracking for the magnetic ball levitation system via exact feedforward linearisation and GPI control. Int. J. Control 2010, 83, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, C.V.; Ananthababu, P.; Latha, D.P.; Sudha, K.R. Design and analysis of position controlled eddy current based nonlinear magnetic levitation system using LMI. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Control Communication & Computing India (ICCC), Kerala, India, 19–21 November 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Santim, M.; Teixeira, M.; Souza, W.A.; Cardim, R.; Assuncao, E. Design of a Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy regulator for a set of operation points. Math. Probl. Eng. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. Design and implementation of an electromagnetic levitation system for active magnetic bearing wheels. IET Control Theory Appl. 2014, 8, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantachaisilp, P.; Lin, Z. Fractional order PID control of rotor suspension by active magnetic bearings. Actuators 2017, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSinawi, A.H.; Emam, S. Dual LQG-PID control of a highly nonlinear magnetic levitation system. In Proceedings of the 2011 Fourth International Conference on Modeling, Simulation and Applied Optimization, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 19–21 April 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, F.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, J.; Lin, G. Nonlinear control of a magnetic levitation system based on coordinate transformations. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164444–164452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesús Rubio, J.; Zhang, L.; Lughofer, E.; Cruz, P.; Alsaedi, A.; Hayat, T. Modeling and control with neural networks for a magnetic levitation system. Neurocomputing 2017, 227, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyavathi, S. Design of sliding mode controller for magnetic levitation system. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2019, 78, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, X.; Man, Z. Terminal sliding mode control design for uncertain dynamic systems. Syst. Control Lett. 1998, 34, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C. A model-free control strategy for vehicle lateral stability with adaptive dynamic programming. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 10693–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.V.; Adhyaru, D.M. Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy regulator design for nonlinear and unstable systems using negative absolute eigenvalue approach. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2019, 7, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkurawy, L.E.; Mohammed, K.G. Model predictive control of magnetic levitation system. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2020, 10, 5802–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fujita, H. Model predictive control for hybrid levitation systems of maglev trains with state constraints. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 9972–9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, M.; Pourgholi, M. Adaptive fuzzy sliding mode control of magnetic levitation system based on Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Neural Network Identification with an Extended Kalman–Bucy filter. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.T.; Suzuki, S.; Sakamoto, N. Nonlinear optimal control design considering a class of system constraints with validation on a magnetic levitation system. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2017, 1, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Lewis, F.L.; Abu-Khalaf, M. Fixed-final-time-constrained optimal control of nonlinear systems using neural network HJB approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2007, 18, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhyaru, D.M.; Kar, I.N.; Gopal, M. Fixed final time optimal control approach for bounded robust controller design using Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman solution. IET Control Theory Appl. 2009, 3, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Ji, H.; Xie, Y. A nearly optimal control for spacecraft rendezvous with constrained controls. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2016, 38, 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Adhyaru, D.M. Robust-optimal control design for current-controlled electromagnetic levitation system with unmatched input uncertainty. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2024, 12, 2980–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Controller | IAE | ISE | ITAE | ITSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOSMC | ||||

| Constrained | ||||

| Unconstrained | ||||

| Unconstrained Input |

| Controller | IAE | ISE | ITAE | ITSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOSMC | ||||

| Constrained | ||||

| Unconstrained | ||||

| Unconstrained Input |

| Controller | IAE | ISE | ITAE | ITSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOSMC | ||||

| Constrained | ||||

| Unconstrained | ||||

| Unconstrained Input |

| Controller | IAE | ISE | ITAE | ITSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOSMC | ||||

| Constrained | ||||

| Unconstrained | ||||

| Unconstrained Input |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pandey, A.; Adhyaru, D.M.; Sharma, G.; Ogudo, K.A. Constrained and Unconstrained Control Design of Electromagnetic Levitation System with Integral Robust–Optimal Sliding Mode Control for Mismatched Uncertainties. Energies 2026, 19, 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020350

Pandey A, Adhyaru DM, Sharma G, Ogudo KA. Constrained and Unconstrained Control Design of Electromagnetic Levitation System with Integral Robust–Optimal Sliding Mode Control for Mismatched Uncertainties. Energies. 2026; 19(2):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020350

Chicago/Turabian StylePandey, Amit, Dipak M. Adhyaru, Gulshan Sharma, and Kingsley A. Ogudo. 2026. "Constrained and Unconstrained Control Design of Electromagnetic Levitation System with Integral Robust–Optimal Sliding Mode Control for Mismatched Uncertainties" Energies 19, no. 2: 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020350

APA StylePandey, A., Adhyaru, D. M., Sharma, G., & Ogudo, K. A. (2026). Constrained and Unconstrained Control Design of Electromagnetic Levitation System with Integral Robust–Optimal Sliding Mode Control for Mismatched Uncertainties. Energies, 19(2), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020350