Complexity of Horizontal Oil–Gas–Water Flows in Deepwater Simulation Well: Insights from Multiscale Phase Permutation Entropy Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. PE, PPE and MPPE Algorithm

2.1. PE Algorithm [17]

2.2. PPE Algorithm [23]

2.3. MPPE Algorithm

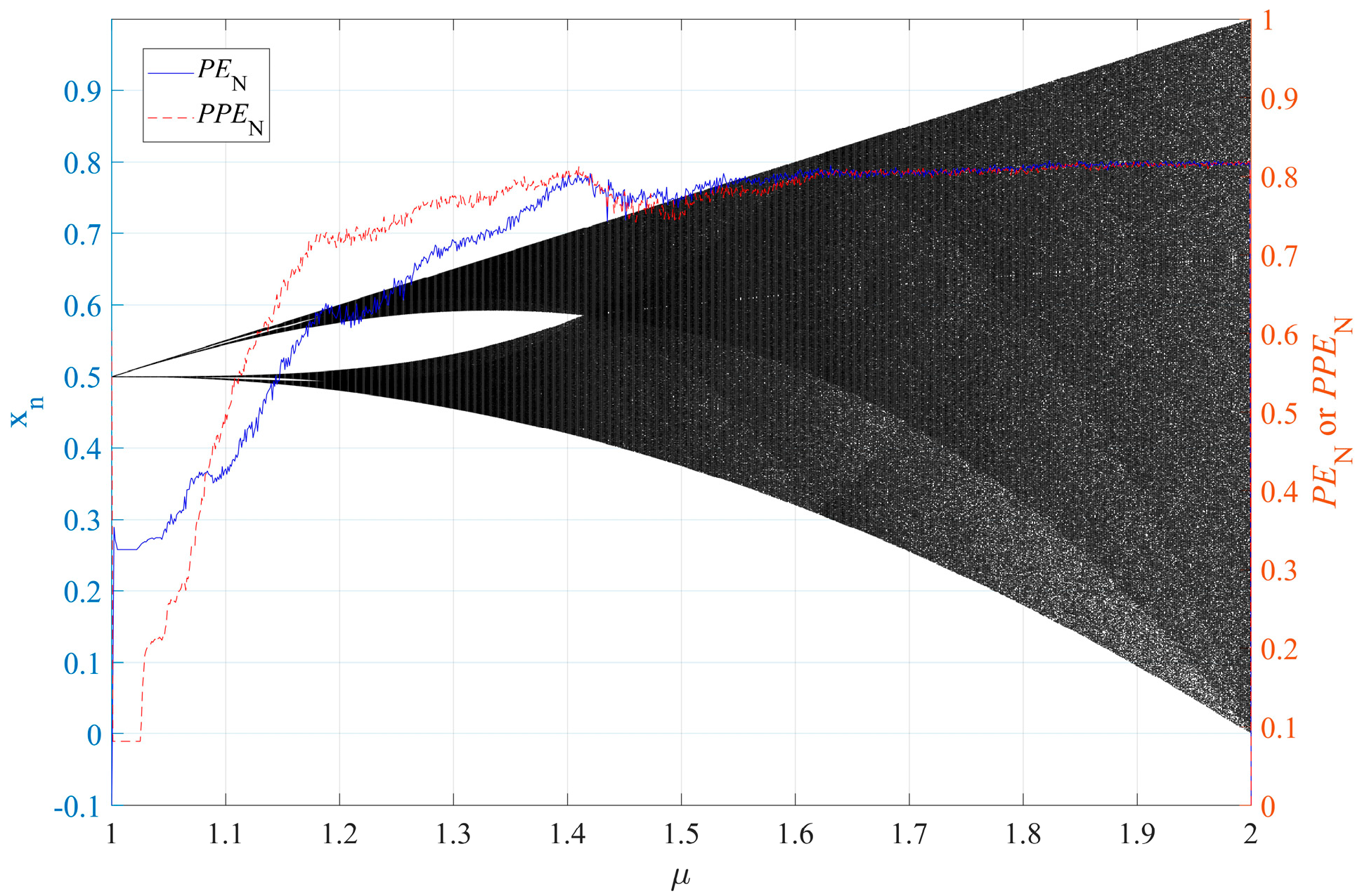

3. Algorithm Evaluation

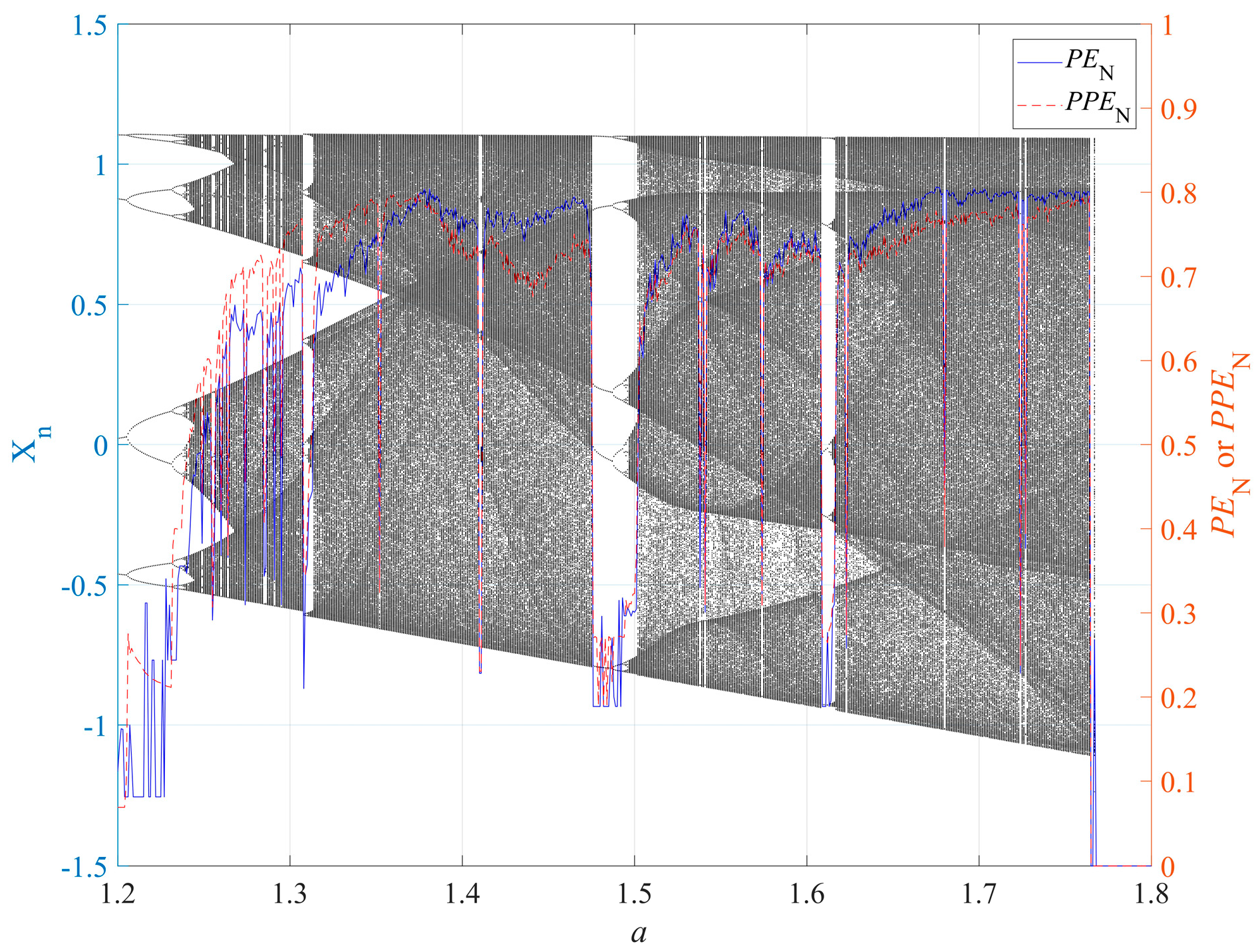

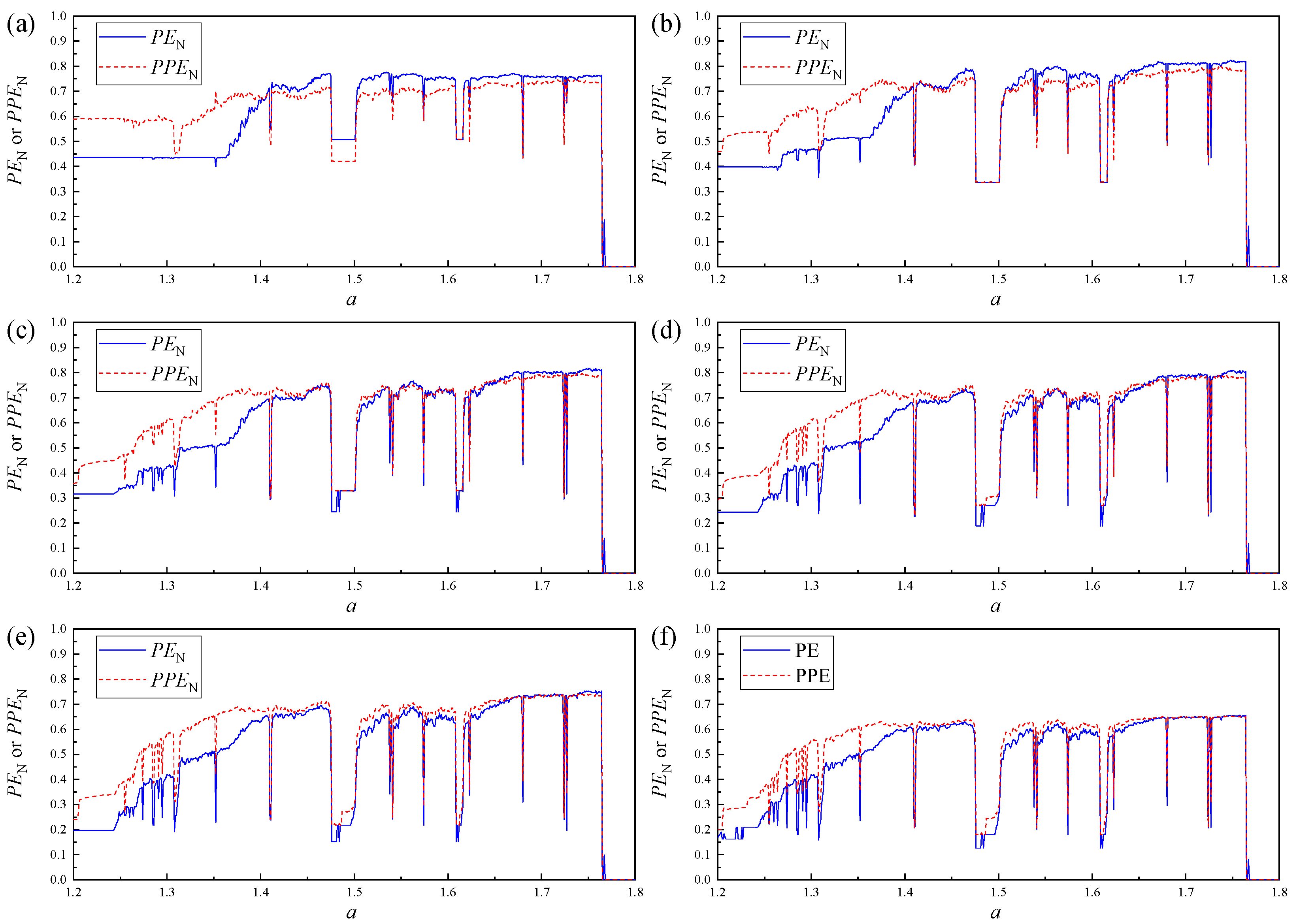

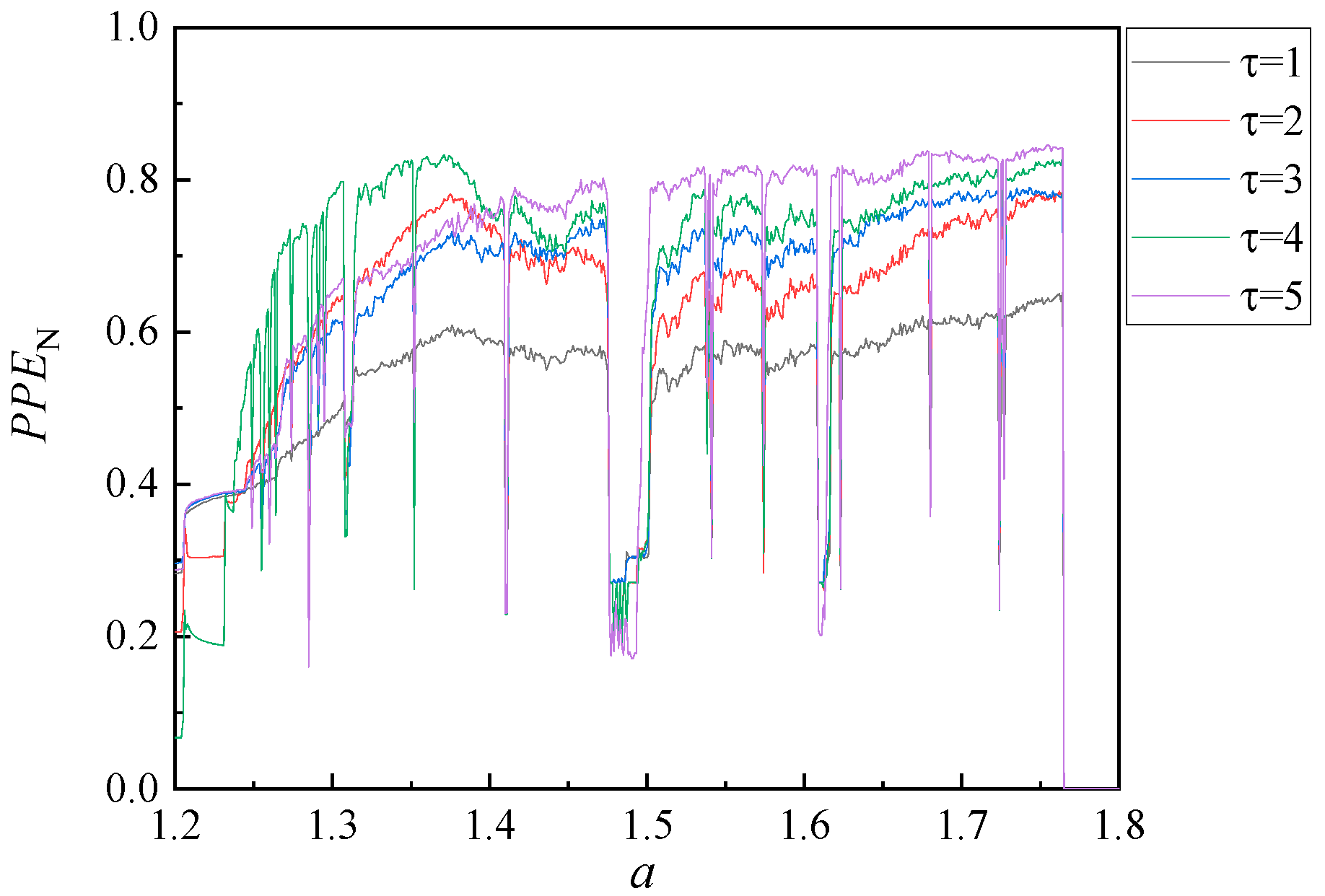

3.1. PPE Evaluation

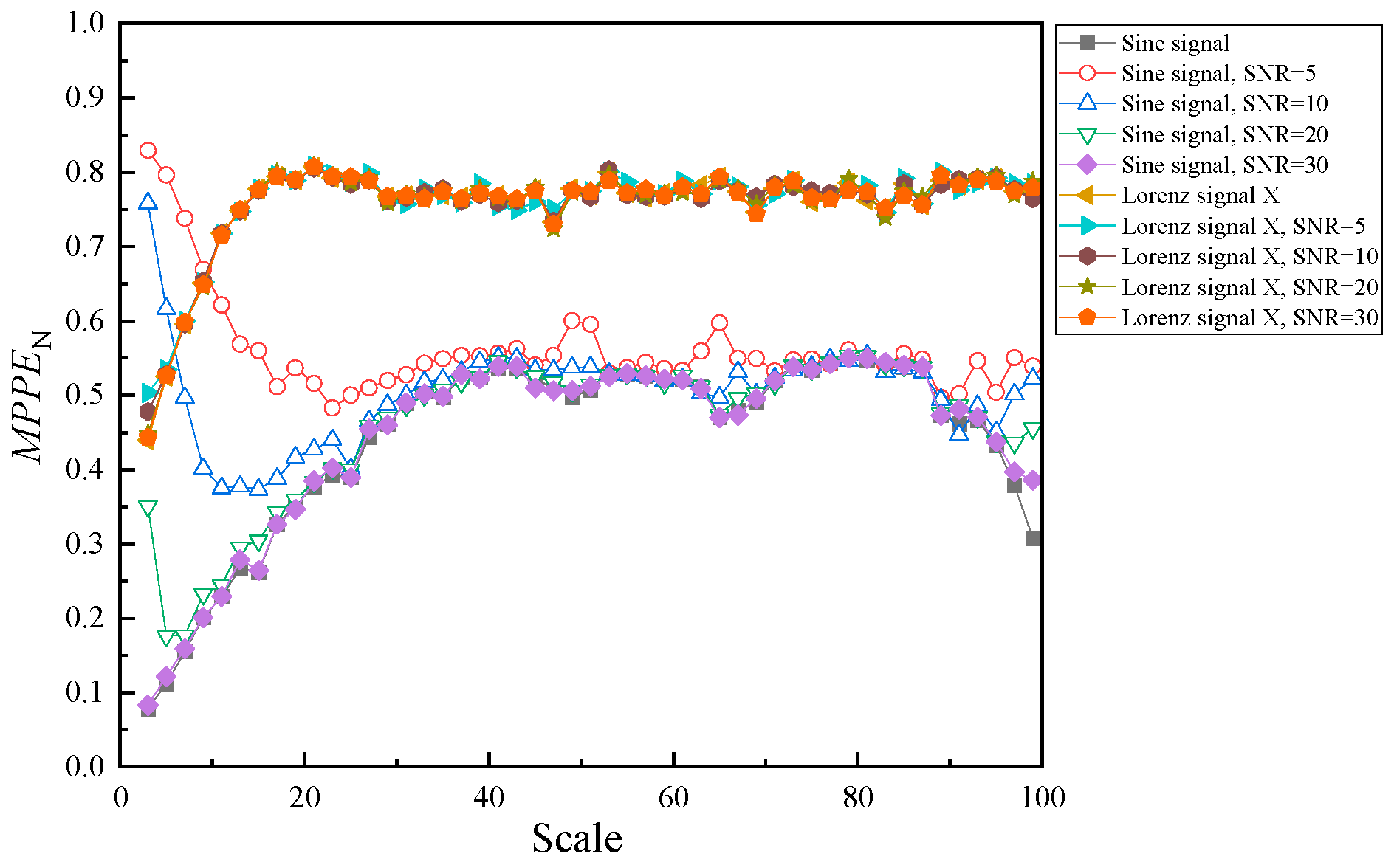

3.2. MPPE Evaluation

4. Data Acquisition for Horizontal Oil–Gas–Water Simulation Well

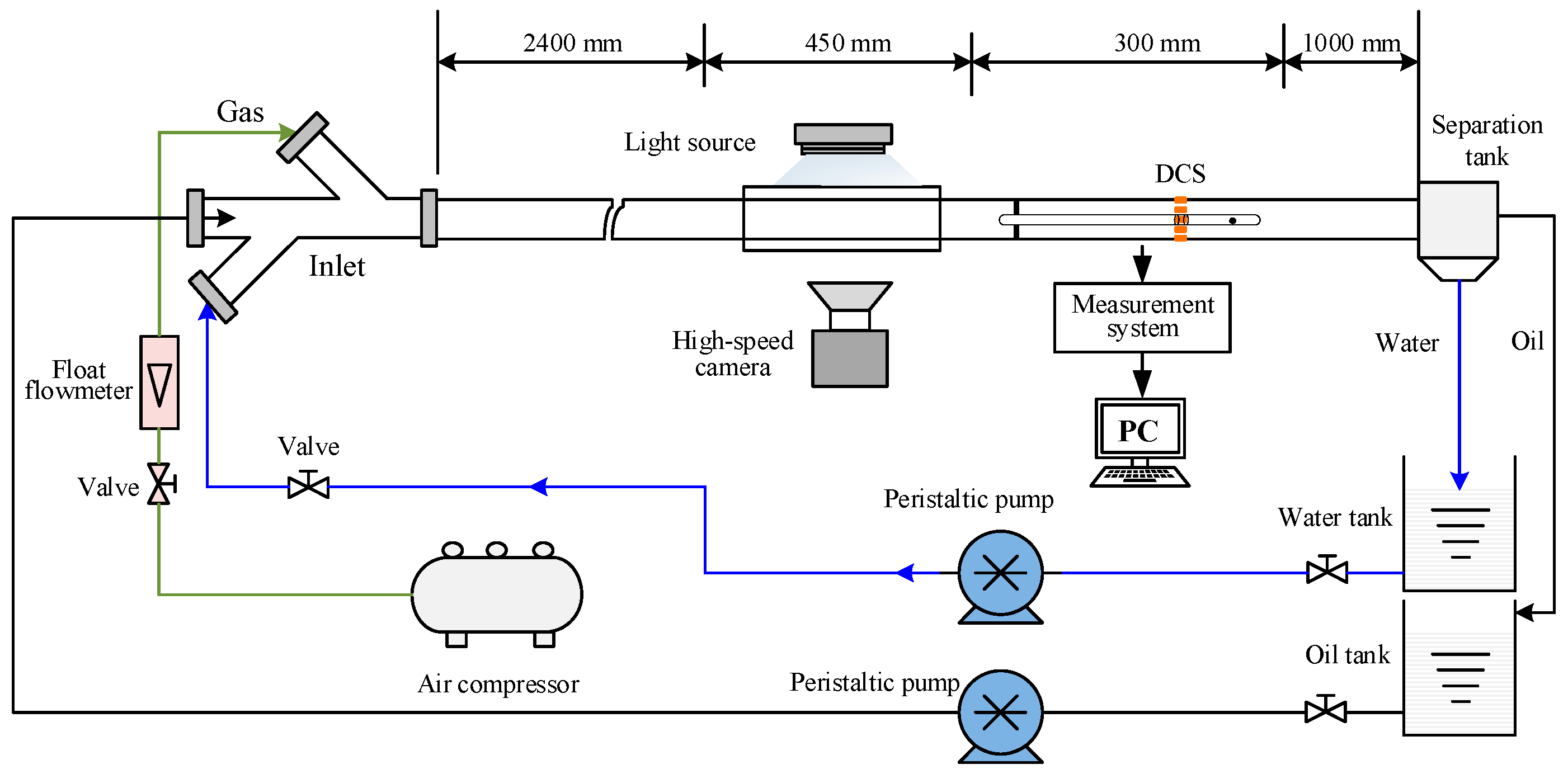

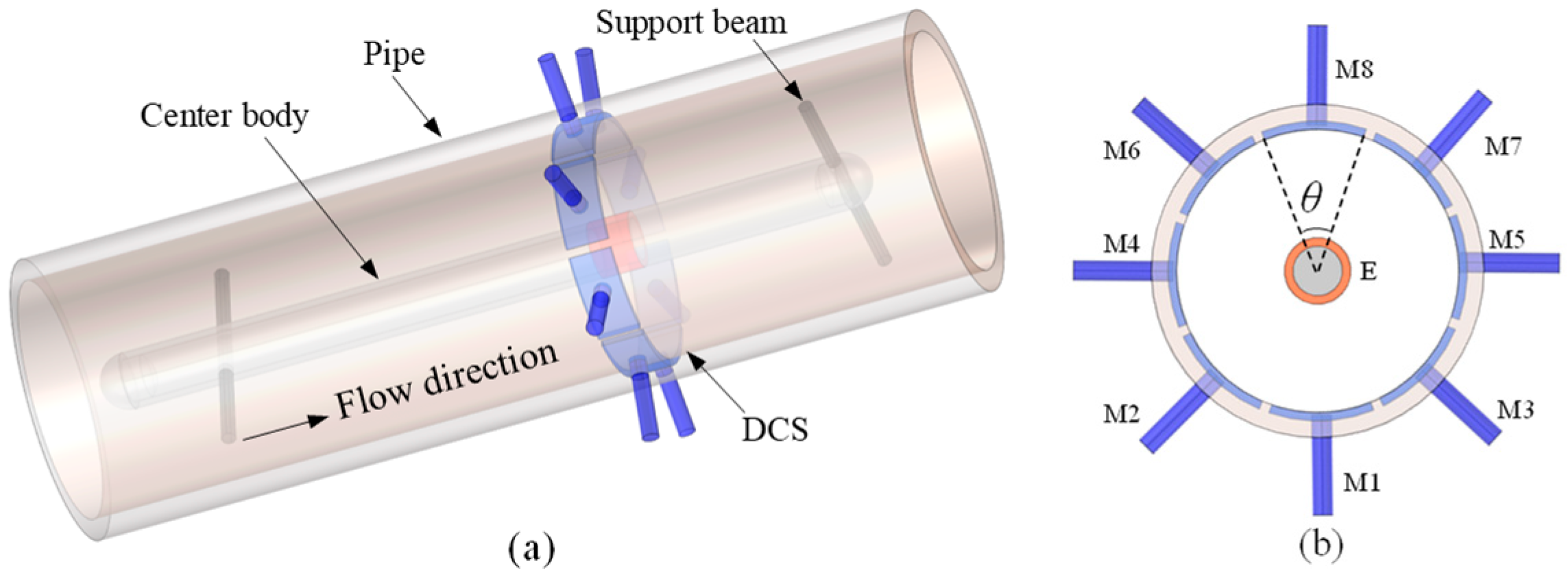

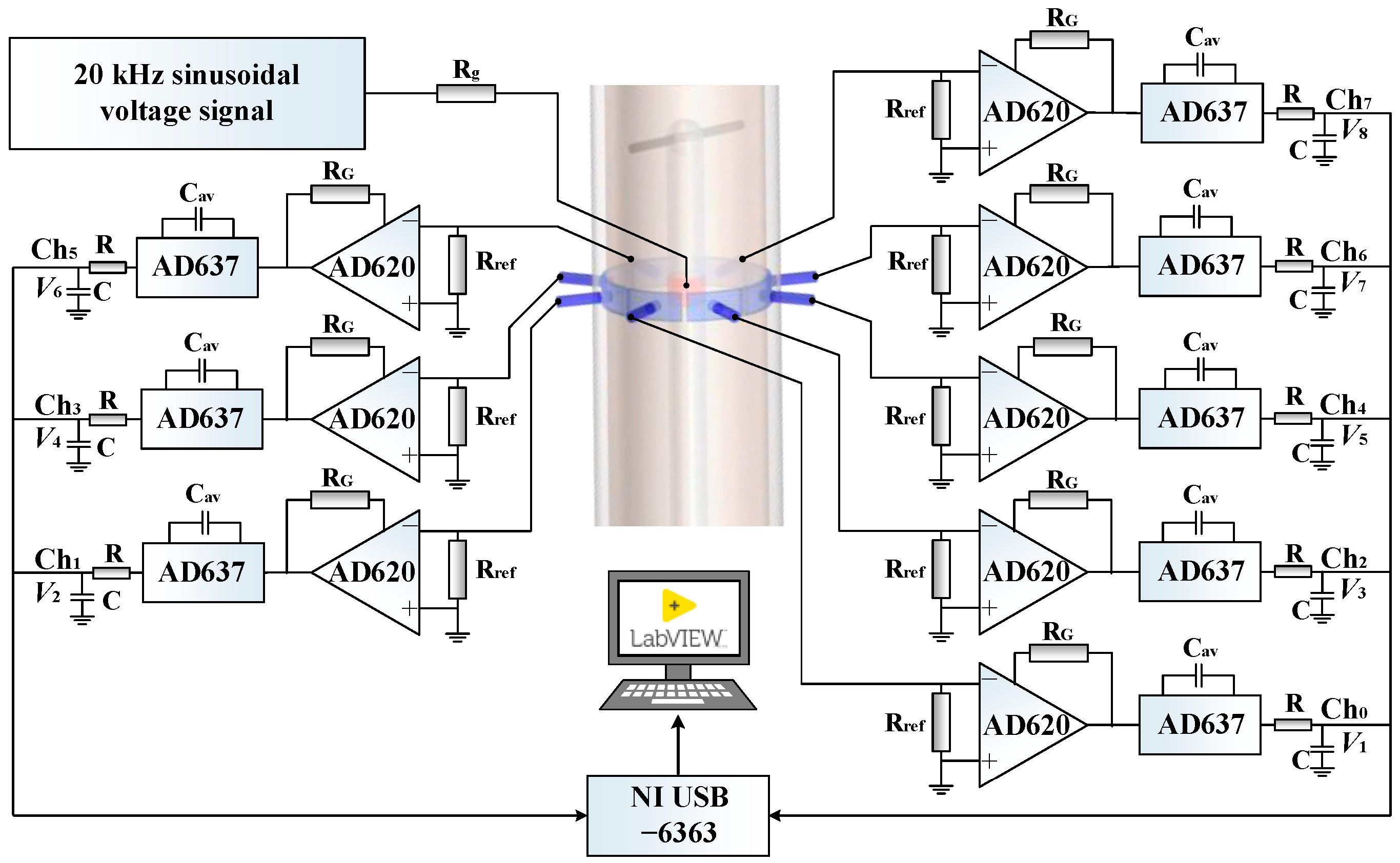

4.1. Experimental Setup

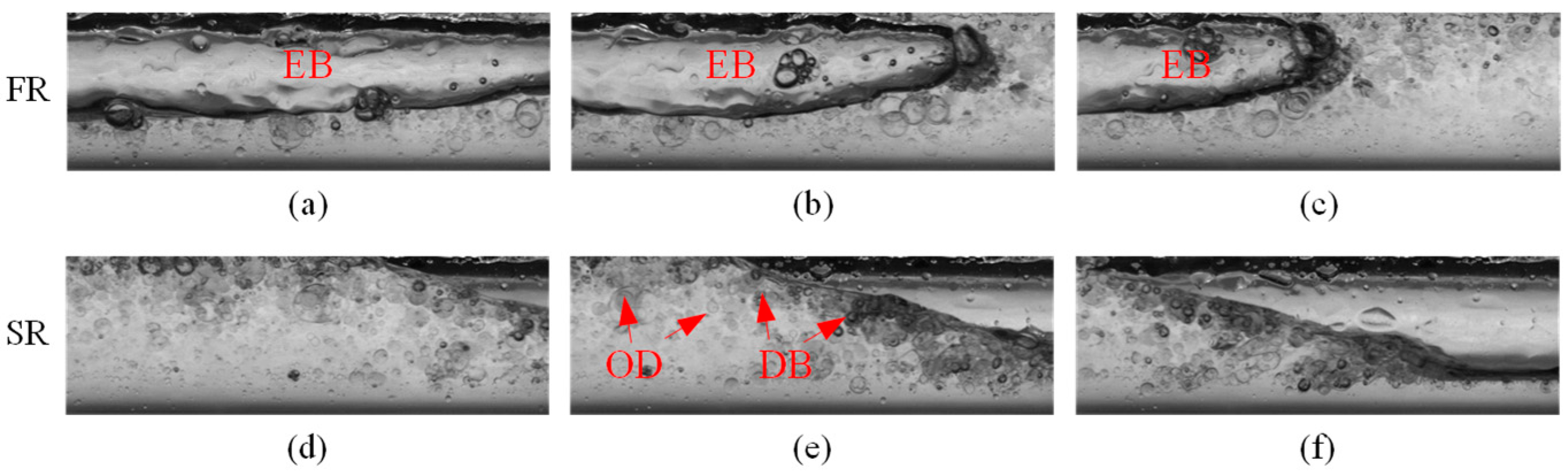

4.2. Flow Images and DCS Responses

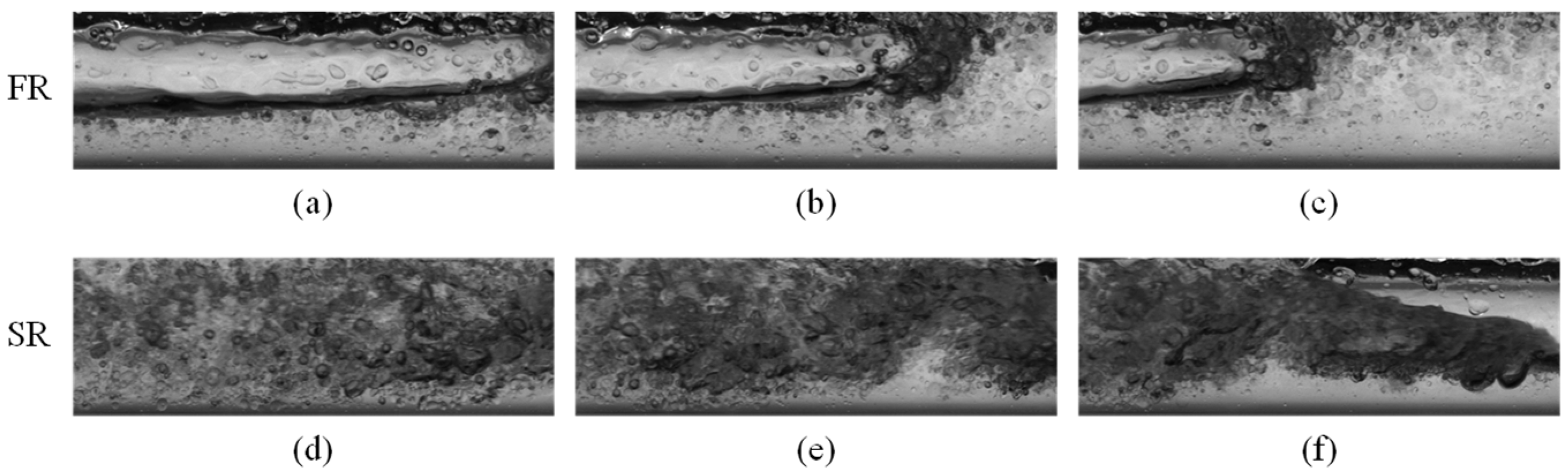

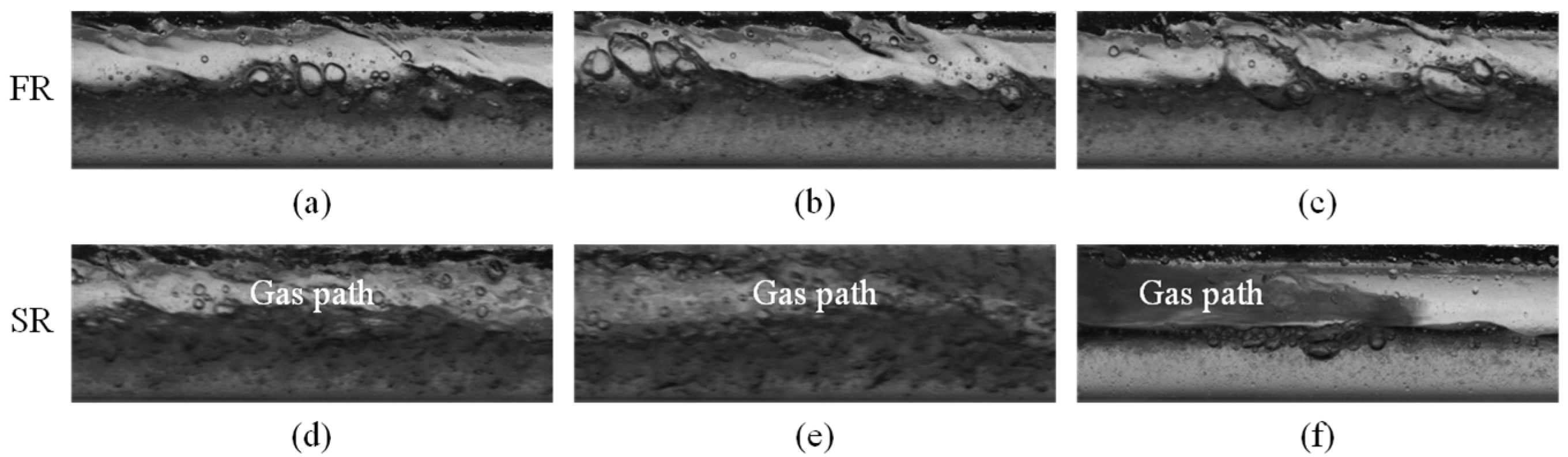

- (1)

- Oil-dispersed slug flow: As illustrated in Figure 9, this flow pattern exhibits a clear quasi-periodic succession of film and slug regions. The slug region contains a limited number of dispersed bubbles and oil droplets, with the oil droplets generally exhibiting relatively large diameters. In the film region, only a small number of bubbles and droplets are observed within the liquid film beneath the elongated bubble.

- (2)

- Emulsified slug flow: With an increase in gas flow rate, as shown in Figure 10, both the film and slug regions display a markedly higher concentration of dispersed bubbles and oil droplets. The slug region becomes strongly aerated, characterized by a greater number and broader spatial distribution of bubbles. Simultaneously, the oil droplets in the slug region are significantly reduced in size, leading to the formation of an oil–water emulsion.

- (3)

- Pseudo slug flow: As the aeration of the slug region intensifies further, gas pathways develop within the slug, progressively disrupting its structure (Figure 11). The liquid phase also appears as an oil-water emulsion, while the overall fluid motion becomes increasingly irregular and chaotic.

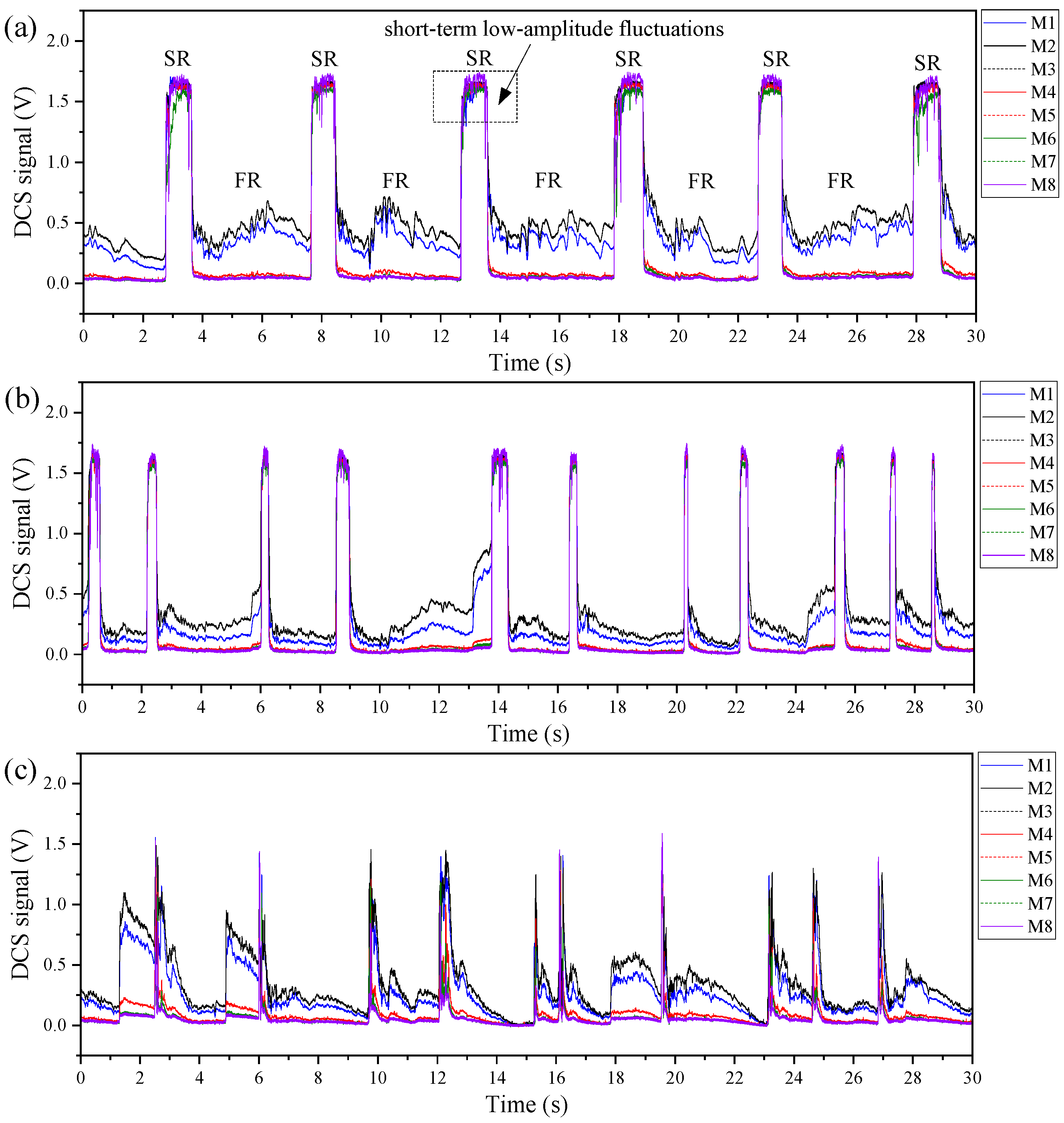

- (1)

- Due to the presence of dispersed bubbles and oil droplets, short-term low-amplitude fluctuations are embedded within the high-amplitude signals corresponding to slug regions, as illustrated in Figure 12a. With increasing gas flow rate, the slug length gradually decreases, and the low-amplitude fluctuations caused by dispersed bubbles and droplets become less evident, as shown in Figure 12b. When the flow transitions into pseudo slug flow, the slug-region signals exhibit sharp peaks, primarily dominated by gas pathways; in this case, the effects of dispersed bubbles and droplets almost vanish, as seen in Figure 12c.

- (2)

- Because of the varying liquid-film thickness beneath the elongated bubble, the signals from electrodes M1, M2, and M3 show large-amplitude oscillations. In contrast, electrodes M4 and M5 are mainly sensitive to the elongated-bubble structure and thus display stable, low-level signals, as observed in Figure 12a,b. Interestingly, when the flow shifts to pseudo slug flow, complex gas coalescence in the film region leads to noticeable fluctuations even in the signals of electrodes M4 and M5. Meanwhile, the responses of M1, M2, and M3 also effectively indicate the intensified instability of the liquid film.

5. Complexity of Horizontal Oil–Gas–Water Flows

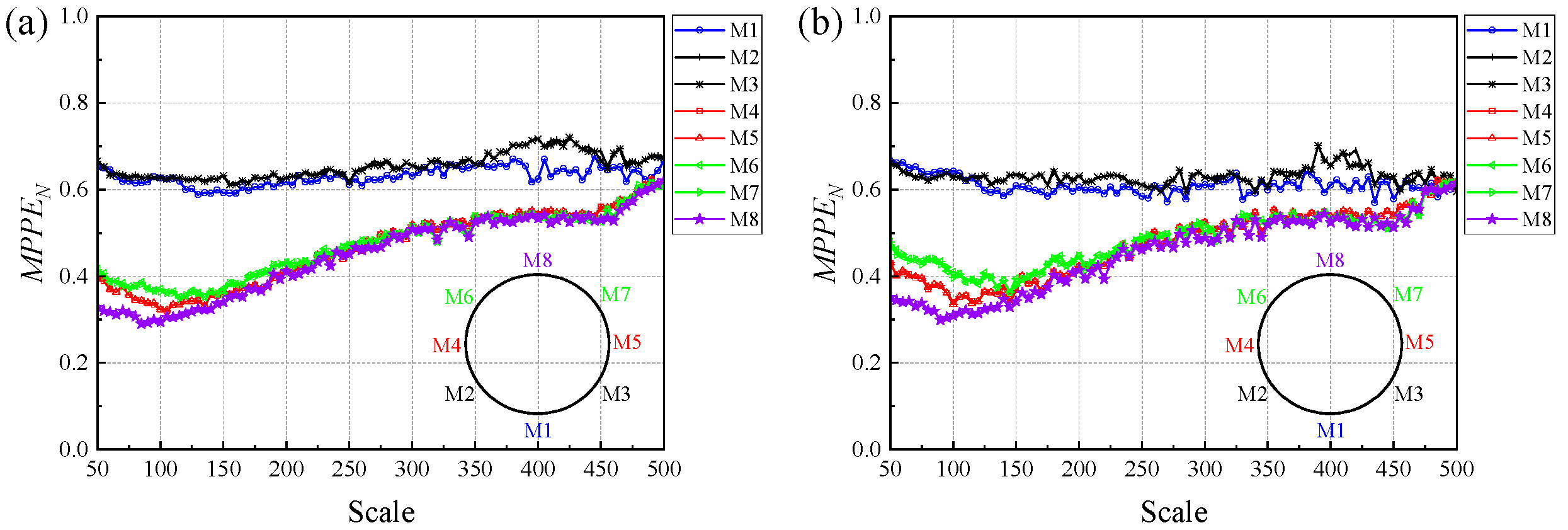

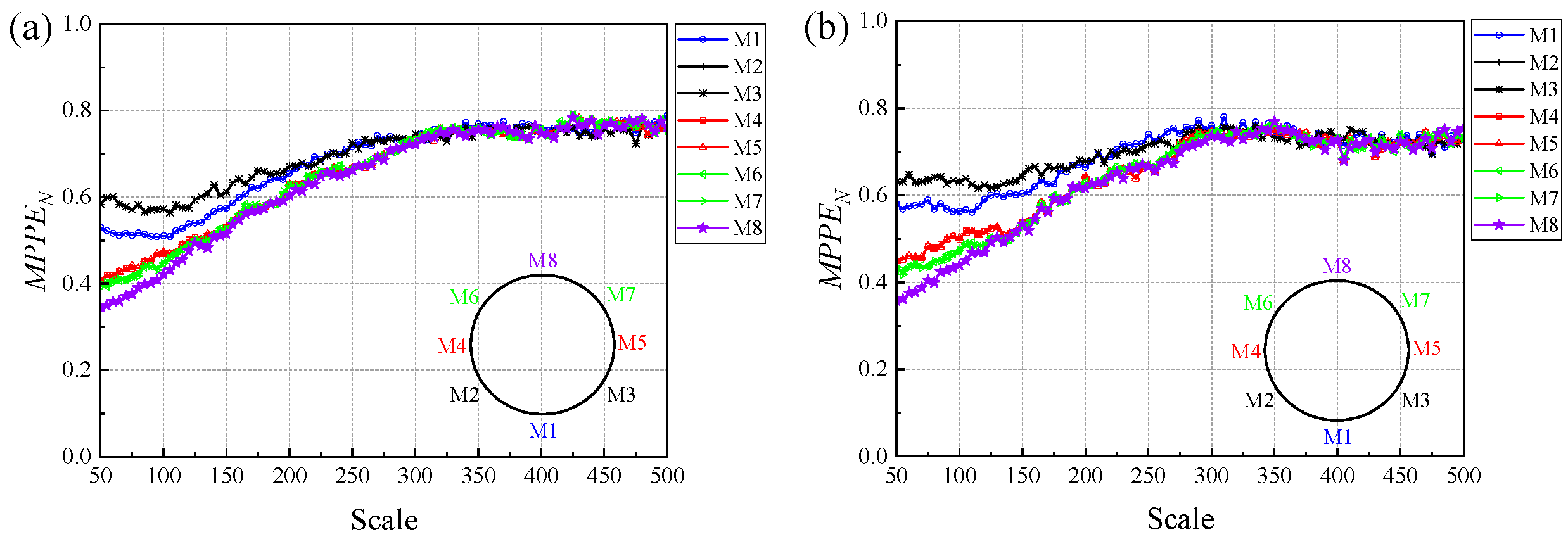

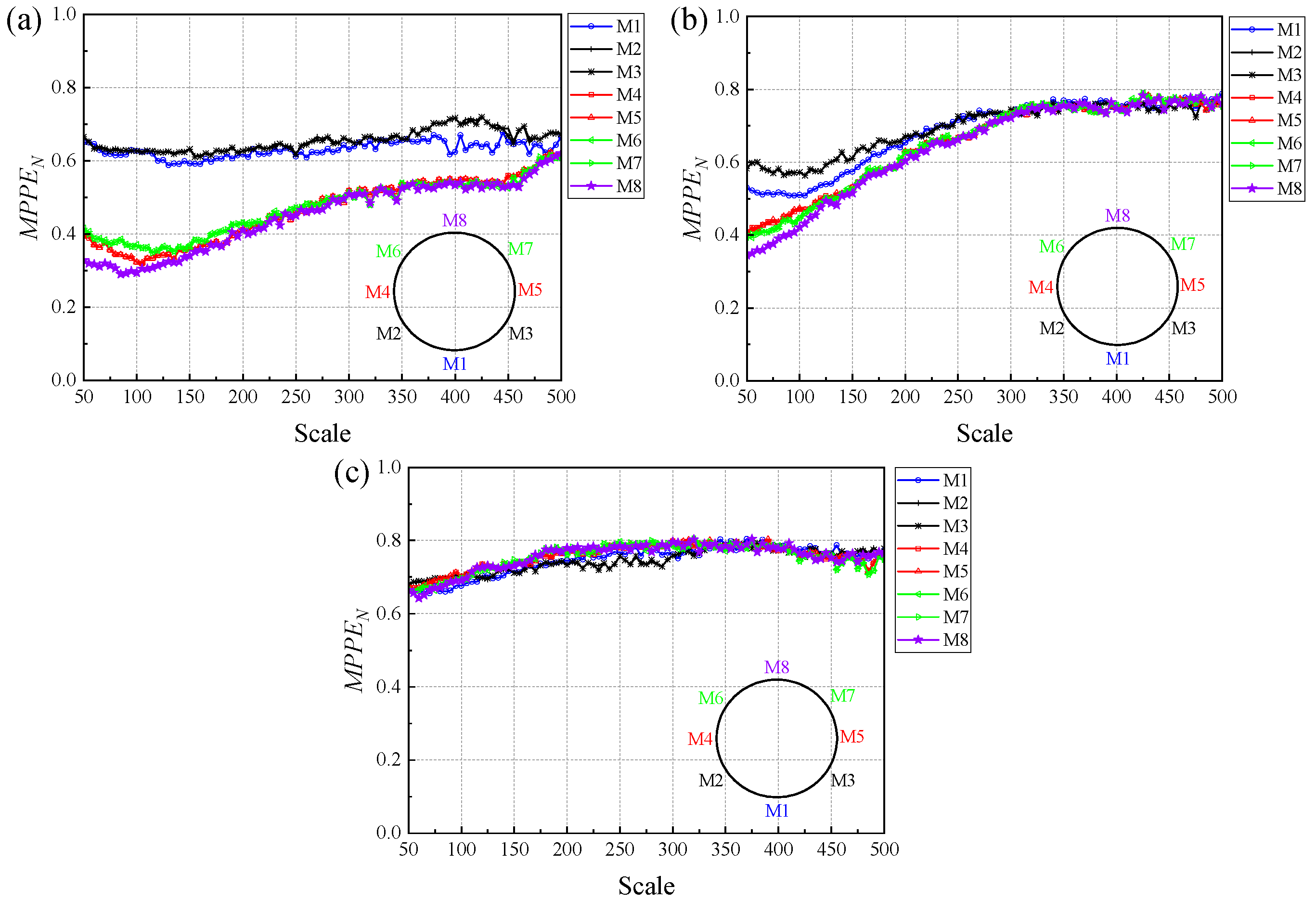

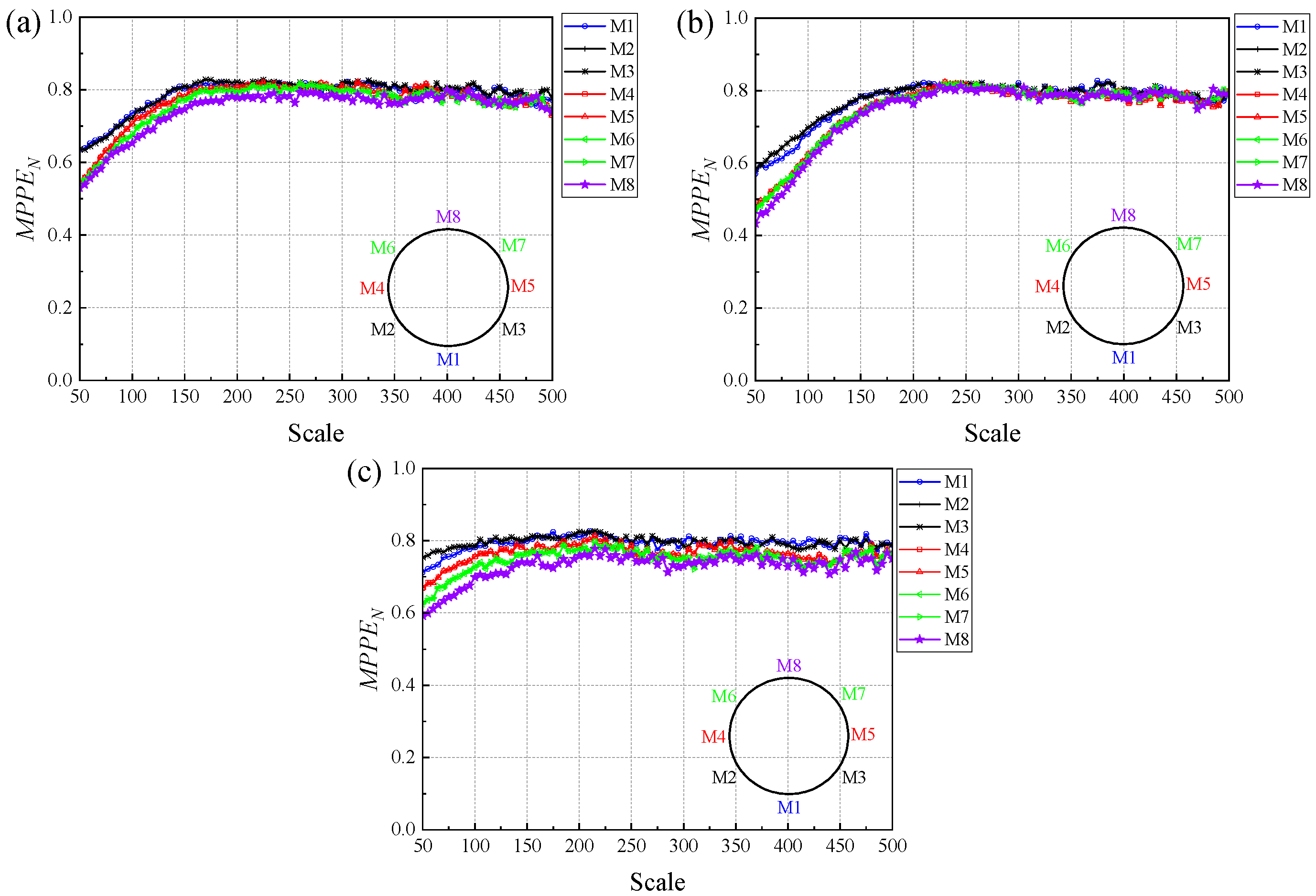

- (1)

- At low gas flow rates, as shown in Figure 14a, the flow pattern corresponds to oil-dispersed slug flow. Because electrodes M1, M2, and M3 are located at the bottom of the pipe, they are able to capture information on the motion of dispersed bubbles and oil droplets as well as fluctuations in liquid-film thickness. Their values are relatively high, indicating more complex hydrodynamic behavior near the pipe bottom. In comparison, electrodes M4–M8 are more sensitive to the quasi-periodic motion of elongated bubbles and liquid slugs in the upper part of the pipe, and thus show lower values within the examined scales.

- (2)

- With increasing gas flow rate, as illustrated in Figure 14b, the values of signals from different electrodes tend to converge at larger scales and exhibit a noticeable increasing trend. At smaller scales, however, the shows a distinct difference according to electrode height: as the electrode position rises, the gradually decreases. This indicates that the motion complexity of small-scale bubbles and oil droplets presents a spatial gradient distribution.

- (3)

- When pseudo slug flow occurs, as shown in Figure 14c, the overall motion complexity of the flows increases throughout the entire pipe cross-section, and the values at different spatial positions become relatively close.

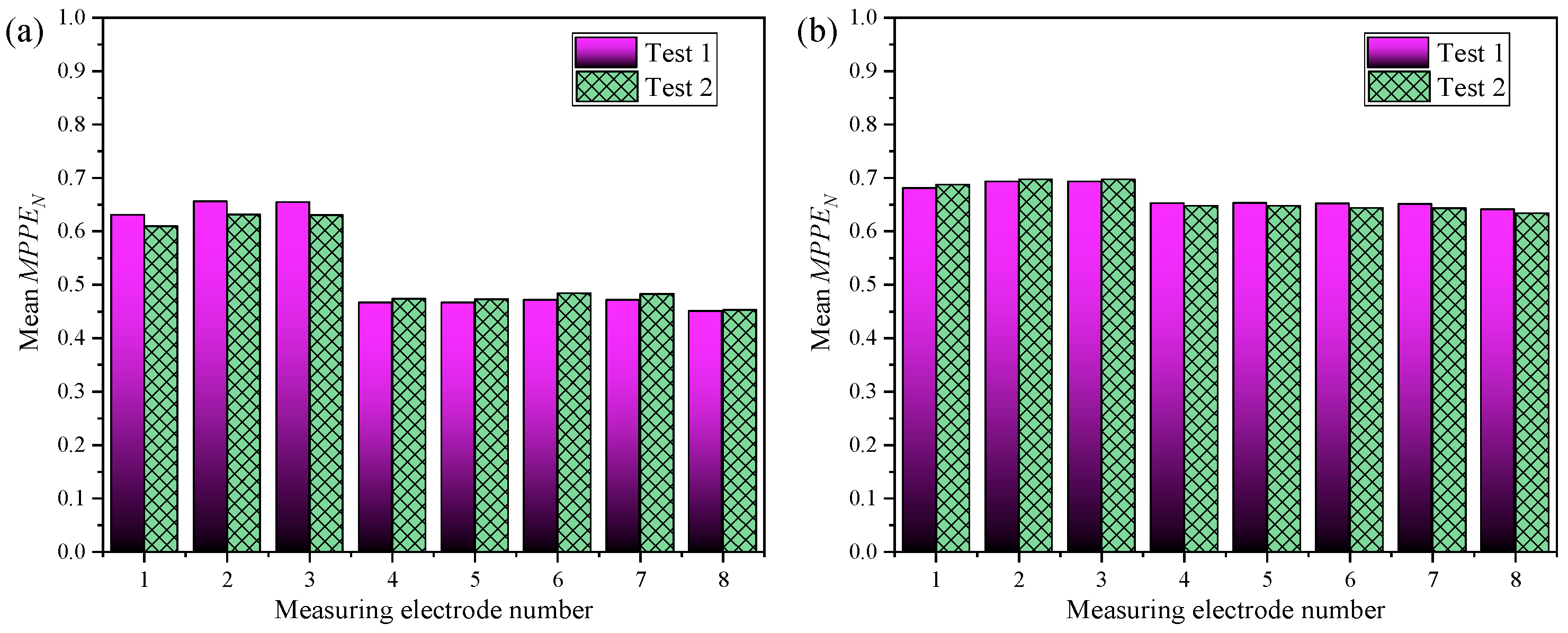

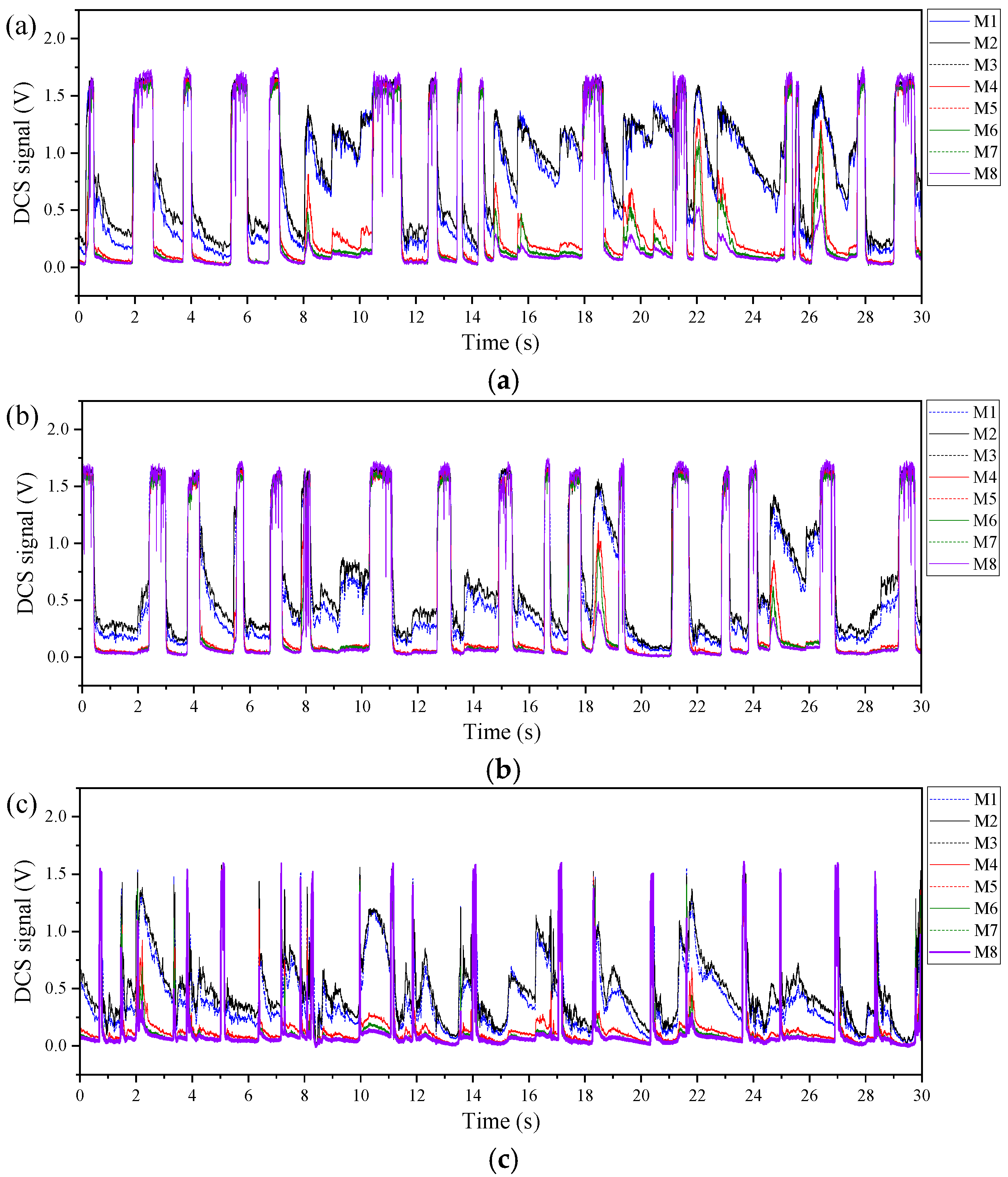

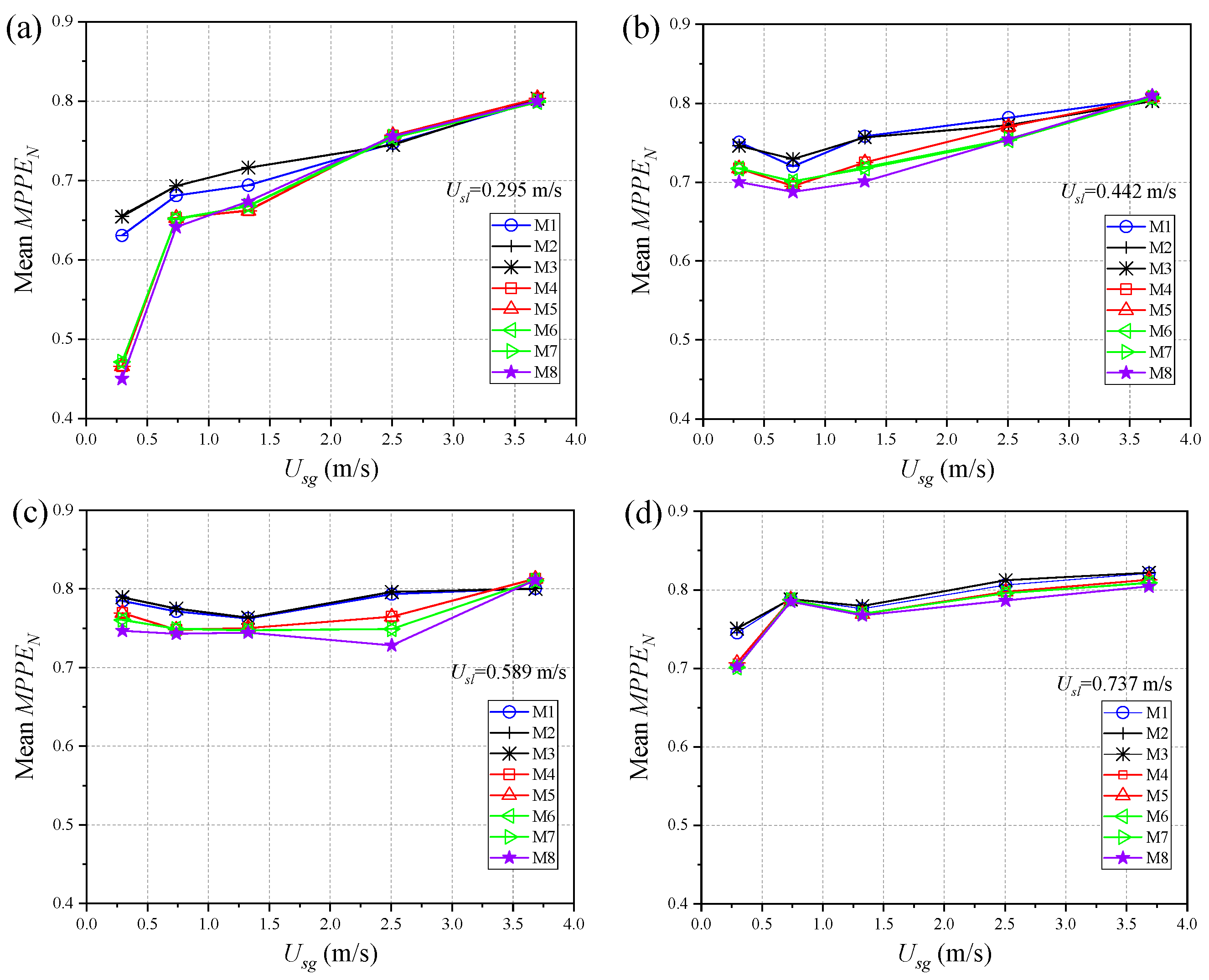

- (1)

- When the superficial liquid velocity is relatively low, as shown in Figure 16a, the flow complexity at the eight local positions in the pipe increases with the rise in gas flow rate. At low gas flow rates, the mean of the M1, M2, and M3 electrode signals is higher, suggesting that the flow complexity is dominated by dispersed phase motion and liquid film fluctuations near the pipe bottom. At higher gas flow rates, however, the mean values obtained from different electrode signals show better consistency, indicating that the flow complexity has expanded across the entire pipe.

- (2)

- When the superficial liquid velocity increases to 0.442 m/s, as shown in Figure 16b, higher gas flow rates always produce higher mean values for all electrode signals, while the mean of the M1, M2, and M3 electrode signals remains relatively high.

- (3)

- With a further increase in superficial liquid velocity, as shown in Figure 16c,d, all electrodes exhibit relatively high mean values under various gas flow rates, and the difference in flow complexity between the pipe bottom and top no longer follows a clear pattern.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- For oil-dispersed slug flow, the presence of dispersed bubbles and oil droplets can produce high flow complexity at the lower part of the pipe. In comparison, measuring electrodes at the upper part of the pipe are more sensitive to the quasi-periodic motion of elongated bubbles, and thus show lower values within the examined scales.

- (2)

- For emulsified slug flow, values of different electrodes tend to converge at larger scales. At smaller scales, however, the shows a distinct difference according to electrode height. As the electrode position rises, the gradually decreases, indicating that the motion complexity of small-scale bubbles and oil droplets presents a spatial gradient distribution.

- (3)

- For pseudo-slug flow, the overall dynamical complexity increases across the pipe cross-section. It is worth noting that when the superficial liquid velocity is relatively low, the complexity values at different electrodes remain close to each other. However, when the superficial liquid velocity becomes sufficiently high, the flow complexity gradually decreases from the bottom to the top of the pipe. This behavior is mainly attributed to the coexistence of large-scale gas pathways, dispersed bubbles, and oil droplets, which leads to a highly non-uniform spatial distribution of the flow structures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Zhuang, L.; Jin, N.; Zhao, A.; Gao, Z.; Zhai, L.; Tang, Y. Nonlinear multi-scale dynamic stability of oil–gas–water three-phase flow in vertical upward pipe. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 302, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Huang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Xu, B.; Jin, N. Measurement of gas holdup in slug region of horizontal oil–gas–water three-phase flow by a distributed ultrasonic sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 2547–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Meng, X.; Qiao, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W. Measurement of water holdup in slug region of oil-gas-water intermittent flow by plug-in conductance sensors. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2025, 102, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, J.S.; Moorman, J.R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 278, H2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-Z.; Qian, X.-Y.; Lu, H.-Y. Cross-sample entropy of foreign exchange time series. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2010, 389, 4785–4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Jin, N.D.; Gao, Z.K.; Zong, Y.B. Multi-scale cross entropy analysis for inclined oil–water two-phase countercurrent flow patterns. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 6099–6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scafetta, N.; Grigolini, P. Scaling detection in time series: Diffusion entropy analysis. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2002, 66, 036130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Goldberger, A.L.; Peng, C.K. Multiscale entropy analysis of biological signals. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2005, 71, 021906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Peng, C.K.; Goldberger, A.L.; Hausdorff, J.M. Multiscale entropy analysis of human gait dynamics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2003, 330, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Goldberger, A.L.; Peng, C.K. Multiscale entropy analysis of complex physiologic time series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 068102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuraisingham, R.A.; Gottwald, G.A. On multiscale entropy analysis for physiological data. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2006, 366, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, L.; Maestri, R.; Marinazzo, D.; Nitti, L.; Pellicoro, M.; Pinna, G.D.; Stramaglia, S.; Tupputi, S.A. Multiscale analysis of short term heart beat interval, arterial blood pressure, and instantaneous lung volume time series. Artif. Intell. Med. 2007, 41, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.J.; Xie, C.; Han, F. Multi-scale approximate entropy analysis of foreign exchange markets efficiency. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2012, 3, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, Q.; Yuan, N.; Yao, Z. Multi-scale entropy analysis of vertical wind variation series in atmospheric boundary-layer. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2014, 19, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begušić, S.; Kostanjčar, Z.; Kovač, D.; Stanley, H.E.; Podobnik, B. Information feedback in temporal networks as a predictor of market crashes. Complexity 2018, 2018, 2834680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnack, D.; Laminski, E.; Schünemann, M.; Pawelzik, K.R. Topological causality in dynamical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 098301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandt, C.; Pompe, B. Permutation entropy: A natural complexity measure for time series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 174102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Sun, K.; Wang, H. Multivariate permutation entropy and its application for complexity analysis of chaotic systems. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2016, 461, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.U.; Mandic, D.P. Multivariate multiscale entropy: A tool for complexity analysis of multichannel data. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2011, 84, 061918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Shang, P. Multivariate multiscale sample entropy of traffic time series. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 86, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, F.C.; Labate, D.; La Foresta, F.; Bramanti, A.; Morabito, G.; Palamara, I. Multivariate multi-scale permutation entropy for complexity analysis of alzheimer’s disease EEG. Entropy 2012, 14, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Shang, P. Multivariate weighted multiscale permutation entropy for complex time series. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 88, 1707–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G. Phase permutation entropy: A complexity measure for nonlinear time series incorporating phase information. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 568, 125686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, G.; Qin, K.; Li, C. An image encryption scheme based on chaotic tent map. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 87, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarbanel, H.D.I.; Kennel, M.B. Local false nearest neighbors and dynamical dimensions from observed chaotic data. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Top. 1993, 47, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebert, W.; Schuster, H.G. Proper choice of the time delay for the analysis of chaotic time series. Phys. Lett. A 1989, 142, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Angeli, P.; Jin, N.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, L. The nonlinear analysis of horizontal oil-water two-phase flow in a small diameter pipe. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2017, 92, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhai, L.; Huang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Cui, J. Complexity of Horizontal Oil–Gas–Water Flows in Deepwater Simulation Well: Insights from Multiscale Phase Permutation Entropy Analysis. Energies 2026, 19, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010052

Zhai L, Huang Y, Qiao J, Cui J. Complexity of Horizontal Oil–Gas–Water Flows in Deepwater Simulation Well: Insights from Multiscale Phase Permutation Entropy Analysis. Energies. 2026; 19(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhai, Lusheng, Yukun Huang, Jiawei Qiao, and Jingru Cui. 2026. "Complexity of Horizontal Oil–Gas–Water Flows in Deepwater Simulation Well: Insights from Multiscale Phase Permutation Entropy Analysis" Energies 19, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010052

APA StyleZhai, L., Huang, Y., Qiao, J., & Cui, J. (2026). Complexity of Horizontal Oil–Gas–Water Flows in Deepwater Simulation Well: Insights from Multiscale Phase Permutation Entropy Analysis. Energies, 19(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010052