Thermal Characterization of a Stainless Steel Flat Pulsating Heat Pipe and Benchmarking Against Copper

Abstract

1. Introduction

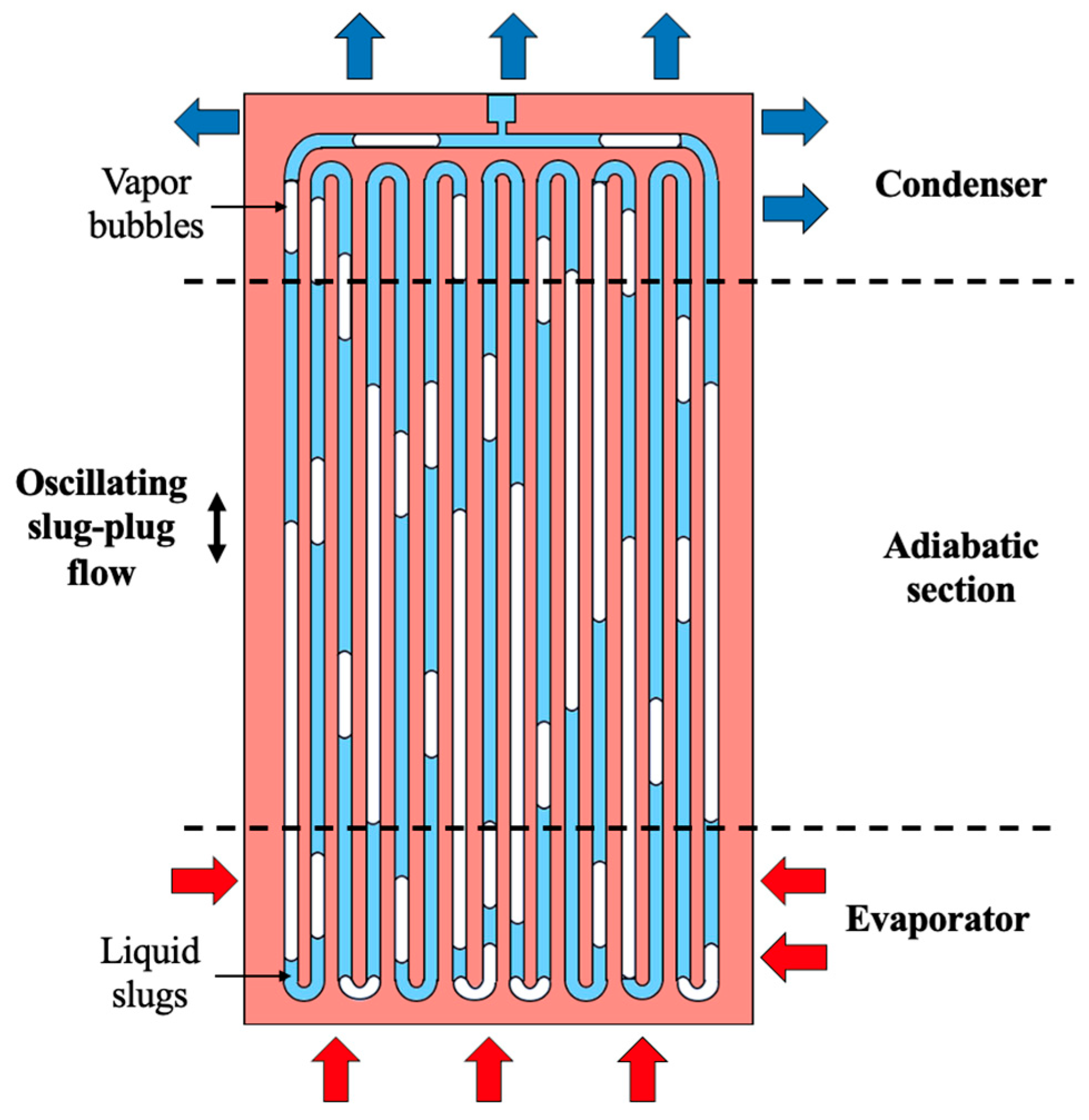

2. Materials and Methods

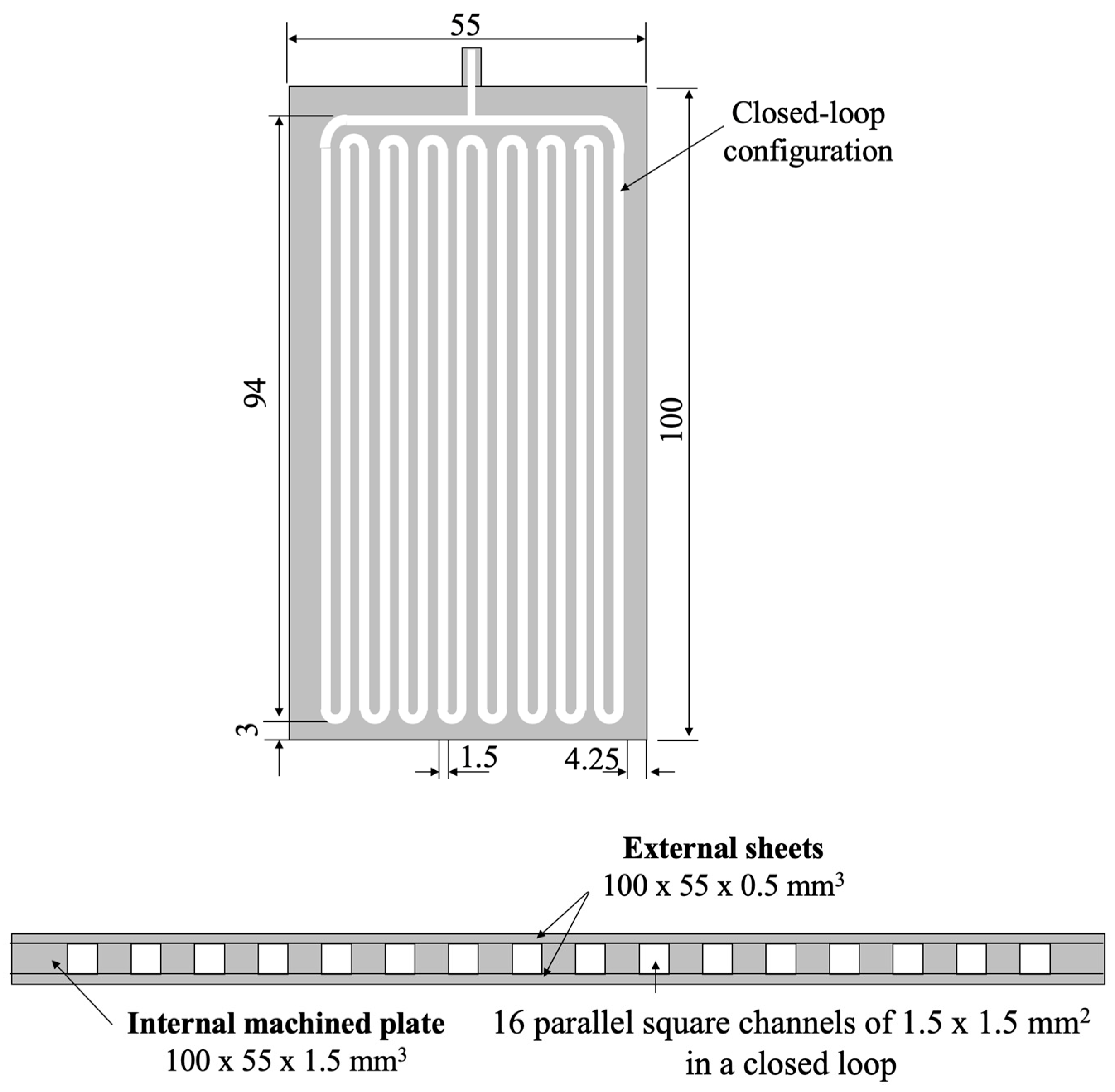

2.1. Manufacturing of Flat PHPs

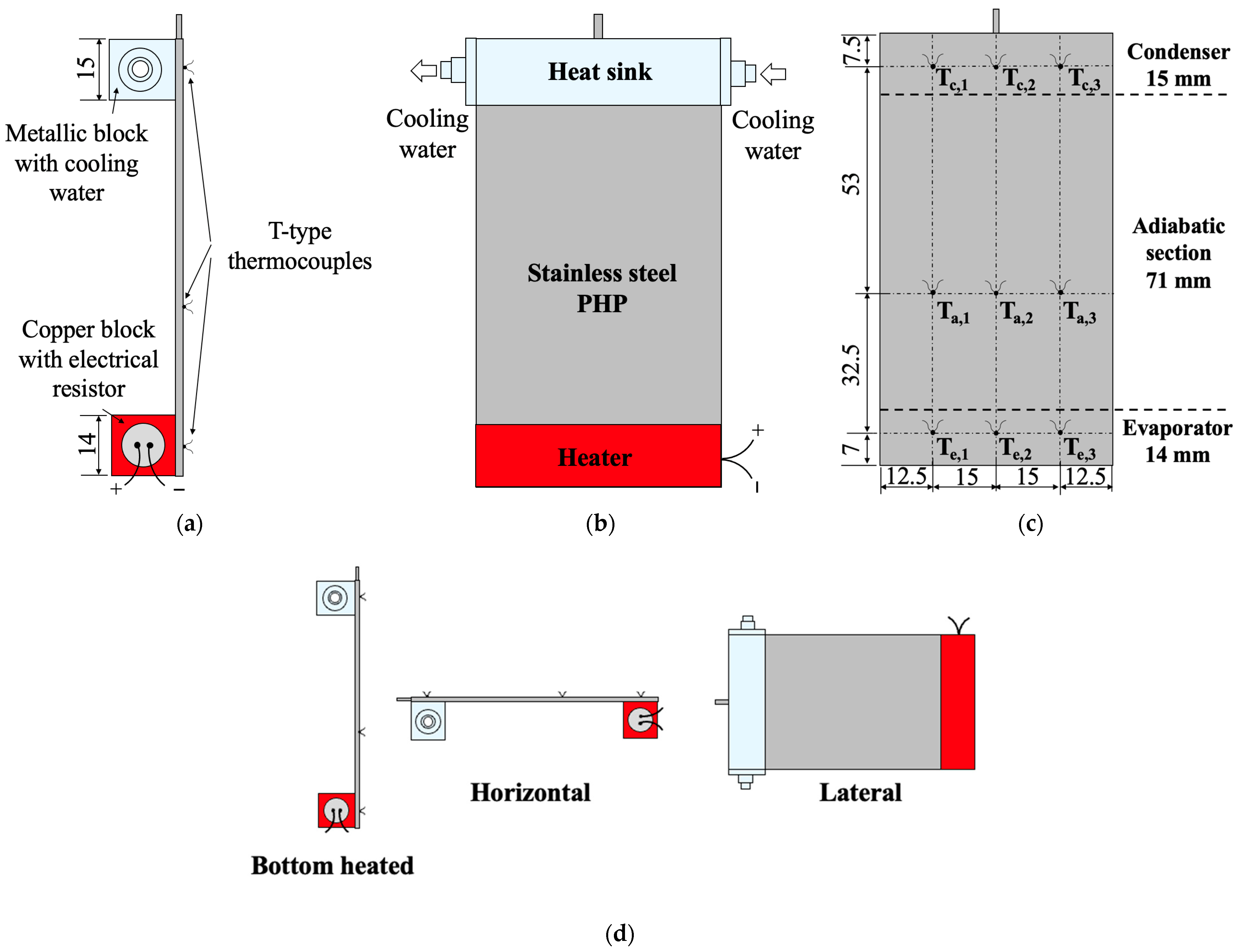

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Experimental Procedure

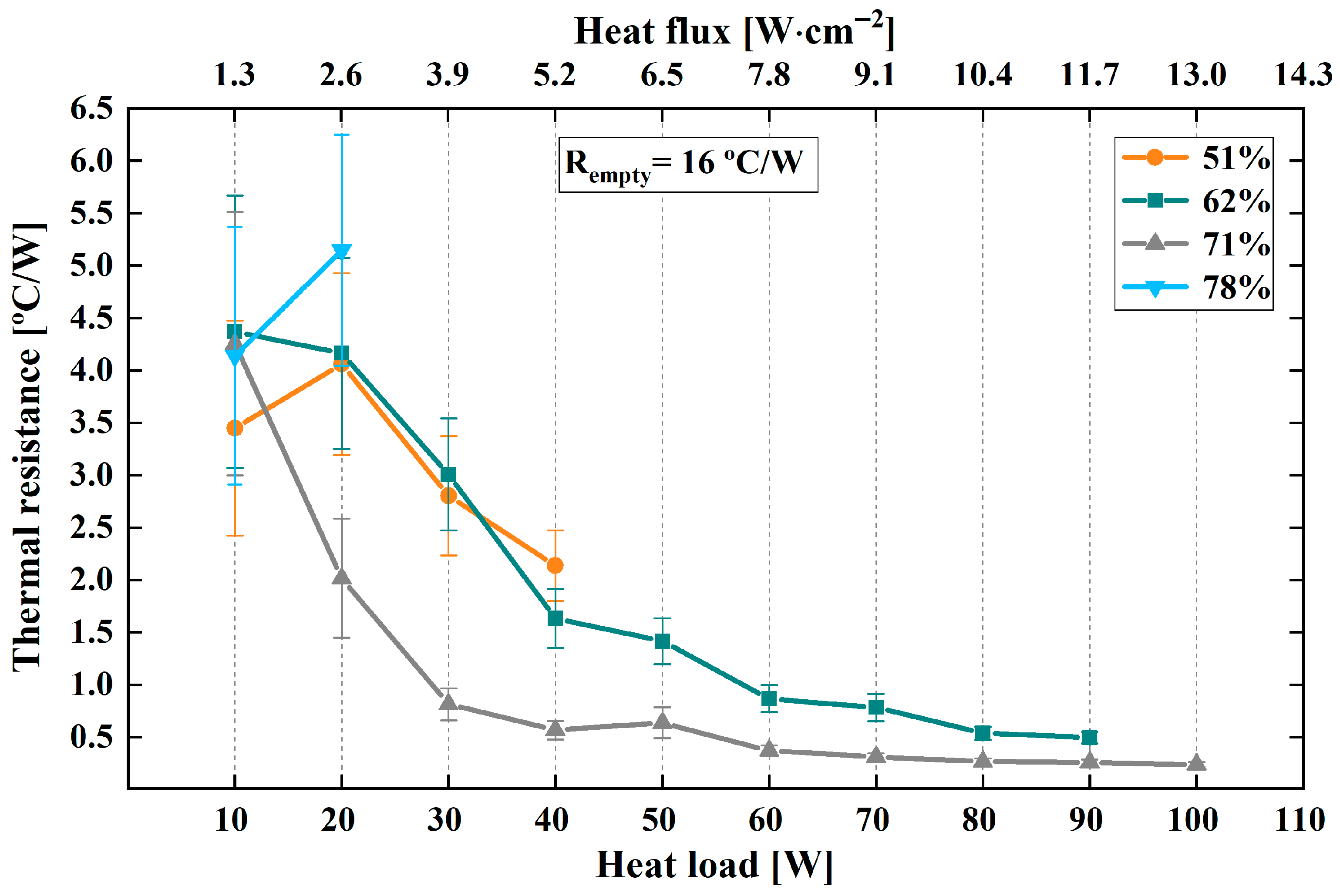

- Filling Ratio Study: The effect of working fluid volume on the heat transfer performance of the stainless steel mini PHP was investigated. Various filling ratios were tested to identify the optimal fluid volume, defined as the ratio of working fluid to the total internal channel void volume. Baseline tests were also conducted without fluid, where heat transfer occurred solely via conduction.

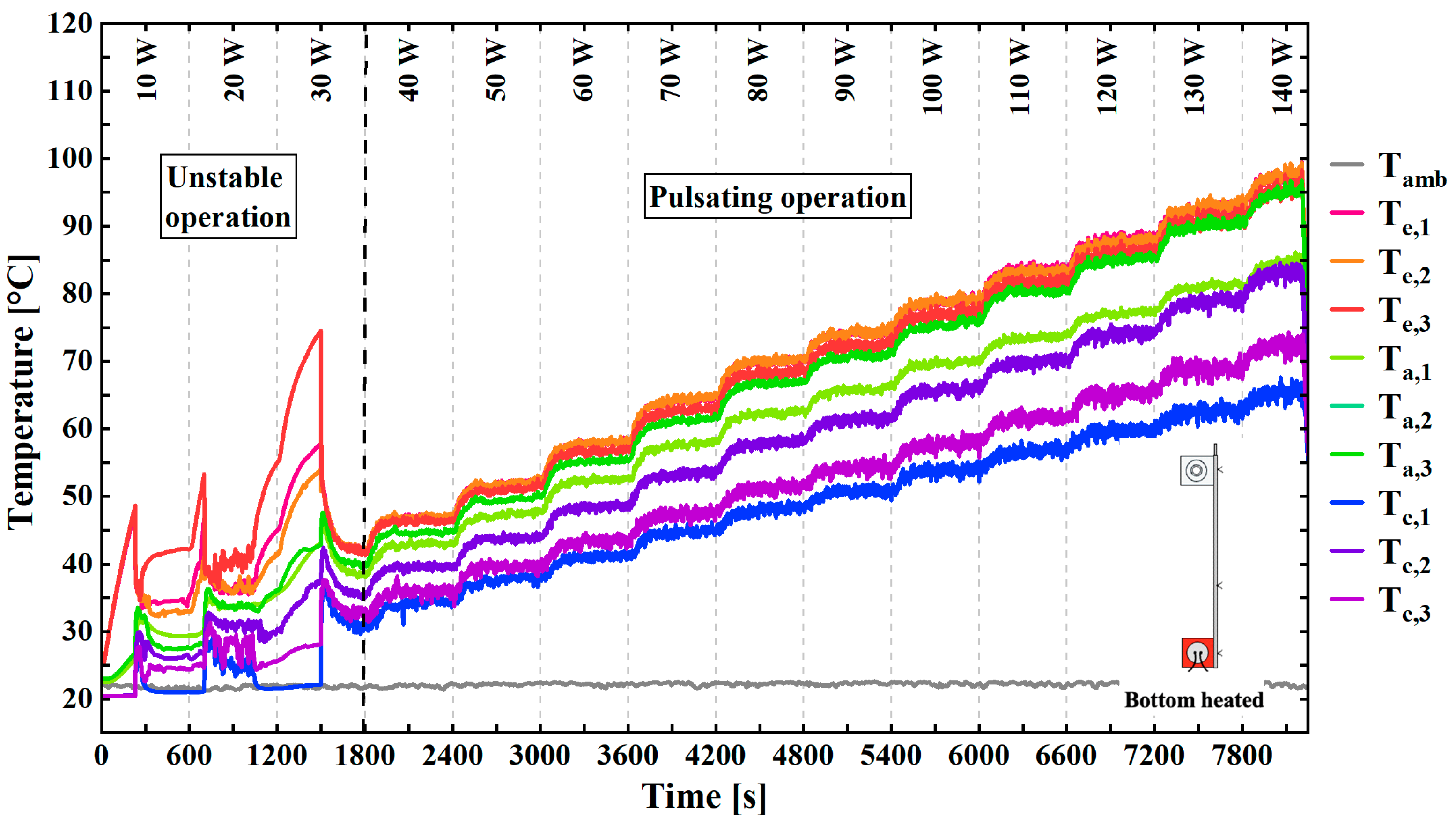

- Orientation Effect: The impact of gravity was investigated by testing the mini-PHP in three orientations: horizontal, vertical bottom-heated (evaporator below condenser), and lateral (condenser and evaporator side by side), as illustrated schematically in Figure 5d. The optimum filling ratio identified from Test I was used for these experiments.

- Benchmarking Comparison: The thermal performance of the stainless steel PHP was compared with that of a copper mini-PHP under identical operating conditions. Both devices were tested using the same filling ratio to ensure that any differences in thermal behavior were attributed solely to the tube material rather than variations in the amount of working fluid. Maintaining an identical filling ratio was essential to allow a fair comparison.

2.4. Data Reduction

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Filling Ratio Study of the Stainless Steel Flat PHP

3.2. Orientation Effect in the Thermal Behavior

3.3. Benchmarking Comparison

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| OHP | Oscillating Heat Pipe |

| PHP | Pulsating Heat Pipe |

| UFSC | Federal University of Santa Catarina |

References

- Khandekar, S.; Panigrahi, P.K.; Lefèvre, F.; Bonjour, J. Local Hydrodynamics of Flow in a Pulsating Heat Pipe: A Review. Front. Heat Pipes 2010, 1, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolayev, V.S. Physical Principles and State-of-the-Art of Modeling of the Pulsating Heat Pipe: A Review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 195, 117111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameli, M.; Besagni, G.; Bansal, P.K.; Markides, C.N. Innovations in Pulsating Heat Pipes: From Origins to Future Perspectives. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 203, 117921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Khandekar, S.; Groll, M. Performance Characteristics of Pulsating Heat Pipes as Integral Thermal Spreaders. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2009, 48, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, G.; Culham, J.R. Review and Assessment of Pulsating Heat Pipe Mechanism for High Heat Flux Electronic Cooling. In Proceedings of the The Ninth Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 1–4 June 2004; pp. 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mameli, M.; Marengo, M.; Khandekar, S. Local Heat Transfer Measurement and Thermo-Fluid Characterization of a Pulsating Heat Pipe. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2014, 75, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandekar, S.; Charoensawan, P.; Groll, M.; Terdtoon, P. Closed Loop Pulsating Heat Pipes—Part B: Visualization and Semi-Empirical Modeling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2003, 23, 2021–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd Corporation. Two-Phase Thermal Solution Guide. Available online: https://www.boydcorp.com (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Somers-Neal, S.; Phan, N.; Watanabe, N.; Ueno, A.; Nagano, H.; Saito, Y. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of a Diffusion Bonded Flat-Type Loop Heat Pipe for Passive Thermal Management. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 257, 124485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, W.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, H. Fabrication and Thermal Performance of Mesh-Type Ultra-Thin Vapor Chambers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 162, 114263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, A.; Kim, S.J. The Effect of Substrate Conduction on the Thermal Performance of a Flat Plate Pulsating Heat Pipe. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Heat Transfer, Fluid Mechanics and Thermodynamics, Orlando, FL, USA, 14–16 July 2014; pp. 1411–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Shang, F.; Yang, K.; Zheng, C.; Cao, X. Experimental Study of Thermal Performance of Pulsating-Heat-Pipe Heat Exchanger with Asymmetric Structure at Different Filling Rates. Energies 2024, 17, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameli, M.; Piacquadio, S.; Viglione, A.S.; Catarsi, A.; Bartoli, C.; Marengo, M.; Di Marco, P.; Filippeschi, S. Start-Up and Operation of a 3D Hybrid Pulsating Heat Pipe on Board a Sounding Rocket. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 2019, 31, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abela, M.; Mameli, M.; Nikolayev, V.; Filippeschi, S. Experimental Analysis and Transient Numerical Simulation of a Large Diameter Pulsating Heat Pipe in Microgravity Conditions. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2022, 187, 122532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarini, L.; Cattani, L.; Bozzoli, F.; Mameli, M.; Filippeschi, S.; Rainieri, S.; Marengo, M. Thermal Characterization of a Multi-Turn Pulsating Heat Pipe in Microgravity Conditions: Statistical Approach to the Local Wall-to-Fluid Heat Flux. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2021, 169, 120930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfotenhauer, J.M.; Sun, X.; Berryhill, A.; Shoemaker, C.B. The Influence of Aspect Ratio on the Thermal Performance of a Cryogenic Pulsating Heat Pipe. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 196, 117322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, R.; Barba, M.; Bonelli, A.; Baudouy, B. Thermal Performance of a Meter-Scale Horizontal Nitrogen Pulsating Heat Pipe. Cryogenics 2018, 93, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, L.; Vocale, P.; Bozzoli, F.; Malavasi, M.; Pagliarini, L.; Iwata, N. Global and Local Performances of a Tubular Micro-Pulsating Heat Pipe: Experimental Investigation. Heat Mass Transf./Waerme-Und Stoffuebertragung 2022, 58, 2009–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, G. Vibration-Enhanced Performance of Asymmetric Channel Flat-Plate Pulsating Heat Pipes: Reducing Thermal Resistance and Start-up Time under Dynamic Loads. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Pan, Y. Visualization Analysis of Heat Transfer and Flow Behavior in Flat-Plate Pulsating Heat Pipe with Sintered Powder Wick Layer. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 167, 109326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnoni, F.; Ayel, V.; Romestant, C.; Bertin, Y. Experimental Behaviors of Closed Loop Flat Plate Pulsating Heat Pipes: A Parametric Study. In Proceedings of the Joint 19th IHPC and 13th IHPS, Pisa, Italy, 10–14 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krambeck, L.; Domiciano, K.G.; Betancur-Arboleda, L.A.; Mantelli, M.B.H. Novel Flat Plate Pulsating Heat Pipe with Ultra Sharp Grooves. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 211, 118509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.; Rapp, D.; Mahlke, A.; Zunftmeister, F.; Vergez, M.; Wischerhoff, E.; Clade, J.; Bartholomé, K.; Schäfer-Welsen, O. Small-Sized Pulsating Heat Pipes/Oscillating Heat Pipes with Low Thermal Resistance and High Heat Transport Capability. Energies 2020, 13, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, M.; Accardo, A.; Bernagozzi, M.; Spessa, E. A Comparative Life Cycle Analysis of an Active and a Passive Battery Thermal Management System for an Electric Vehicle: A Cold Plate and a Loop Heat Pipe. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantelli, M.B.H. Thermosyphons and Heat Pipes: Theory and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-62772-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Jia, L. Visual Experimental Study on Flat-Plate Pulsating Heat Pipe with Double Condensers. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2025, 114, 109831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wits, W.W.; Groeneveld, G.; Van Gerner, H.J. Experimental Investigation of a Flat-Plate Closed-Loop Pulsating Heat Pipe. J. Heat Transf. 2019, 141, 091807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, L.K.; Dhanalakota, P.; Mahapatra, P.S.; Pattamatta, A. Thermal and Flow Characteristics in a Flat Plate Pulsating Heat Pipe with Ethanol-Water Mixtures: From Slug-Plug to Droplet Oscillations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 194, 123066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, L.K.; Vempeny, D.T.; Dileep, H.; Dhanalakota, P.; Mahapatra, P.S.; Srivastava, P.; Pattamatta, A. Thermal Performance Comparison of Flat Plate Pulsating Heat Pipes of Different Material Thermal Conductivity Using Ethanol-Water Mixtures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krambeck, L.; Domiciano, K.G.; Mantelli, M.B.H. A New Flat Electronics Cooling Device Composed of Internal Parallel Loop Heat Pipes. Exp. Comput. Multiph. Flow 2024, 6, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krambeck, L.; Domiciano, K.G.; Mameli, M.; Filippeschi, S.; Mantelli, M.B.H. Comparison of the Thermal Performance of a Wire-Plate and a Pulsating Heat Pipe. In Proceedings of the 41st UIT International Heat Transfer Conference, Napoli, Italy, 19–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gietzelt, T.; Toth, V.; Huell, A. Diffusion Bonding: Influence of Process Parameters and Material Microstructure; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-953-51-2597-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L.P.; Amaral, M.C.; de Andrade Caldas, L.; Martins, B.M.; Domiciano, K.G.; Krambeck, L.; Xavier, F.A.; Mantelli, M.B.H. Evaluation of Copper Diffusion Bonding Parameters Applied to the Manufacture of Flat Heat Pipes. Mater. Res. 2025, 28, e20250065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, B.S.; Williams, A.D.; Drolen, B.L. Review of Pulsating Heat Pipe Working Fluid Selection. J. Thermophys. Heat Trans. 2012, 26, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, N.; Bozzoli, F.; Pagliarini, L.; Cattani, L.; Vocale, P.; Malavasi, M.; Rainieri, S. Characterization of Thermal Behavior of a Micro Pulsating Heat Pipe by Local Heat Transfer Investigation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 196, 123203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, A.J.; Ma, H.B.; Critser, J.K. Experimental Investigation of Cryogenic Oscillating Heat Pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2009, 52, 3504–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekrami, A.H.; Sabzpooshani, M.; Shafii, M.B. Series Flat Plate Pulsating Heat Pipe: Fabrication and Experimentation. AUT J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 5, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuke, H.; Okazaki, S.; Ogawa, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Balloon Flight Demonstration of an Oscillating Heat Pipe. J. Astron. Instrum. 2017, 6, 1740006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, S.J.; McClintock, F.A. Describing Uncertainities in Single Experiments. Mech. Eng. 1953, 75, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Stainless Steel PHP | Copper PHP (Benchmark) |

|---|---|---|

| Length [mm] | 100 | 100 |

| Width [mm] | 55 | 55 |

| Final thickness [mm] | 2.28 | 2.60 |

| U-Turns | 8 | 8 |

| Channel size [mm2] | 1.5 × 1.5 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| Diffusion bonding cycle | 1160 °C, 24 h, 9 MPa | 875 °C, 1 h, 9 MPa |

| Material | AISI 316L | Cu 99% (C11000) |

| Density [g/cm3] | 7.99 | 8.96 |

| Final Mass [g] | 65.55 | 105.36 |

| Internal void volume [mL] | 3.75 ± 0.02 | 2.85 ± 0.02 |

| Working fluid | Distilled and deionized water | |

| Test | PHP | Filling Ratio (FR) [%] | Orientation | Heat Source/Heat Sink |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filling ratio study | Stainless Steel | 0, 51, 62, 71, and 78 ± 1 | Horizontal | Thermal loads applied of 10 W steps/ Cooling water at 20 °C, 4 L/min |

| Orientation effect | Stainless Steel | 71 ± 1 | Horizontal Bottom heated Lateral | |

| Benchmarking comparison | Stainless Steel | 71 ± 1 | Horizontal Bottom heated | |

| Copper | 70 ± 1 |

| Parameter | Instrument | Resolution/Accuracy | Individual Uncertainty | Combined Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Thermocouple calibration | Varies per thermocouple | Varies per thermocouple | ±0.13 °C |

| Thermometer | 0.1 °C | 0.029 °C | ||

| Acquisition system (DAQ-NITM SCXI-1000, National Instruments Corp., Austin, TX, USA) | 0.01 °C | 0.003 °C | ||

| Repeatability | Varies per thermocouple | Varies per thermocouple | ||

| Voltage | Power supply unit (TDK-LambdaTM GEN300-17, TDK-Lambda Americas Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) | Resolution: 0.036 V Accuracy: 0.3 V | 0.01 V 0.15 V | ±0.15 V |

| Electric current | Resolution: 2.04 mA Accuracy: 68 mA | 0.001 A 0.034 A | ±0.034 A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Krambeck, L.; Guessi Domiciano, K.; Beé, M.E.; Marengo, M.; Mantelli, M.B.H. Thermal Characterization of a Stainless Steel Flat Pulsating Heat Pipe and Benchmarking Against Copper. Energies 2026, 19, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010045

Krambeck L, Guessi Domiciano K, Beé ME, Marengo M, Mantelli MBH. Thermal Characterization of a Stainless Steel Flat Pulsating Heat Pipe and Benchmarking Against Copper. Energies. 2026; 19(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrambeck, Larissa, Kelvin Guessi Domiciano, Maria Eduarda Beé, Marco Marengo, and Marcia Barbosa Henriques Mantelli. 2026. "Thermal Characterization of a Stainless Steel Flat Pulsating Heat Pipe and Benchmarking Against Copper" Energies 19, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010045

APA StyleKrambeck, L., Guessi Domiciano, K., Beé, M. E., Marengo, M., & Mantelli, M. B. H. (2026). Thermal Characterization of a Stainless Steel Flat Pulsating Heat Pipe and Benchmarking Against Copper. Energies, 19(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010045