1. Introduction

The flash furnace is a common process used in copper manufacturing. As it requires a dry and fine charge material in the form of a copper concentrate, part of the input mass of the concentrate is carried over to the waste heat recovery boiler in the form of dust. Dust carried over by off-gas partially settles on boiler tubes, forming build-ups and restricting the boiler efficiency [

1]. In many cases, even a small amount of the deposit on the surface locally reduces the heat exchange [

2] and steam generation. The deposits insulate the surface of heat exchanger tubes and thereby increase the deposit’s surface temperature, which leads to a decrease in the heat flux [

3,

4] and restricts the possibilities for heat transfer. At the initial stage of fouling, until the critical insulation diameter has been achieved, the heat flux can achieve higher values than for a clean tube surface [

5]. The causes of this increase in heat flux also include a change in the heat transfer conditions caused by an increase in the heat transfer surface by its roughening due to the beginning of the depositing process. It is only after the critical thickness has been exceeded that the deposit will impair the heat transfer, thereby causing an increase in the heat resistance.

We divide deposits by the degree to which the particles are bound into the categories of loose and bound. In order to understand the ash settling process, first, the ash’s properties should be examined, including its chemical, mechanical, and thermal aspects. The chemical properties include the chemical constitution and mineral phases of the ash deposit. The mechanical properties include a few aspects: porosity, strength, deposit viscosity, and melting temperature. The thermal properties include its effective thermal conductivity coefficient and radiation properties.

The thermal properties of deposits, such as viscosity, density, specific heat, and thermal conductivity, depend on the ash composition, oxygen availability, and temperature. The literature shows that the loose and bound deposits in waste heat recovery boilers [

6] in the copper production process differ in the heat conductivity coefficient [

7,

8]. The bound deposits from the radiation zone achieve much higher values of the heat conductivity coefficient than the loose ones. The main factors affecting the heat conductivity coefficient of both deposit types are porosity, structure [

9,

10], density, and chemical composition, having an effect on the deposit microstructure. Sintering, grain growth, and other structural changes alter the mechanical and thermal properties of the deposits. This results in denser, mechanically stronger layers with a higher thermal conductivity [

10]. The thermal conductivity of the deposits increases as the sintering time increases. The chemical constitution of ash has an indirect impact on the thermal conductivity [

10]. The deposits also feature a different surface emissivity than the tube material [

11,

12]. The knowledge of thermal properties of the deposits can be used to model the process of heat flow from the off-gases carried from the flash furnace to the heat transfer system.

There have been numerous attempts to understand the mechanisms of deposit formation and to predict the fouling behaviour. The mechanisms related to the deposit formation include inertial settling, rotary settling, thermophoretic force impact, salt condensation, and chemical reactions. A thorough understanding of the mechanisms of fouling allows us to predict the rate of increase in the deposit thickness. One of the approaches seeks to find a relationship between the constitution of the fuel mineral substance and the chemical constitution of the fouling by isolating the individual components and carrying out tests aiming at determining the mineral transformations that occur during heating [

13,

14]. This approach leads to the post-process constituents deposited on the surface of heat exchangers being distinguished, and a determination of which constituents diffuse towards the surface of the tube or deposit, thereby leading to a complex constitution of the fouling.

Due to the complexity of the deposit structure and its change, caused by its exposure to high temperatures, and the complex constitution of the post-process gases during boiler operation, it is very difficult to determine the actual conditions of fouling. The dust particles that settle on the walls experience a drastic change in the environment. The tube wall is much cooler than the gas stream, and the duration of potential reactions is much longer than the normal residence time of particles in the boiler. The deposited particles are also in close contact with other particles, which provides the possibility of an additional range of transformations. As the deposits build up, their surface and internal temperatures increase, leading to very complex secondary reactions resulting from the mineral constitution and manifesting as the sintering of the deposit. The presence of a temperature gradient between the flowing gas and the heat transfer surface makes the prediction of a theoretical fouling model very difficult.

There are two types of dust in copper smelting processes: mechanically formed dust, which consists of small particles of input material that are entrained and carried over with the process gas, and chemically formed dust, which consists of evaporated fine particles, i.e., Ag, As, Pb, Sb, and Zn, as well as their oxides and sulphides, which can condense on the surface of the mechanically formed particles when the off-gas temperature drops. As a result of the dust flow, a viscose coating of condensing vapours can form on the walls of the boiler tubes. At the beginning, fine particles can also deposit as a result of the thermophoretic force. The primary deposit consists of fine particles of less than 3 μm, and it is strongly enriched with alkalis. It results from the diffusion of vapours and fine particles of fly ash on the tube surface. The growth of the primary deposit thickness is enhanced by an increase in the deposit surface temperature and inhibited by the decomposition of complex sulphates as the temperature changes. As the thickness of the deposit layer grows and its surface temperature increases, the secondary layer starts forming. The secondary layer comprises coarser particles (1–100 μm) and contains less alkali. The formation of the secondary layer is usually much slower than that of the primary layer. The secondary layer is believed to form as a result of settling fly ash on the rough outer surface of the heat exchanger.

Once fouling has begun and particles have accumulated, the outer layer of the deposit sinters as a result of the increase in the deposit surface temperature with the increase in the deposit thickness. The sintering process involves reactions under high temperatures but below the melting point. Under these conditions, the constituents diffuse between the adjacent particles of the loose deposit. At first, the diffusion processes only occur at the surface, but as the temperature increases, the dislocation of particles to the defects of the crystalline lattice begins, and at the same time, new gaps form. The sintering changes the structure of fouling from a weak powder layer into a solid, stable structure. Over time, a mature deposit structure comprising several layers may develop. Individual layers differ because they are formed at much higher temperatures.

The objective of this study was to examine the deposits forming on the waste heat recovery boiler tubes. The deposits in the boiler are formed by the dust carried by the off-gas during the production of copper in the flash furnace. The heat from the off-gas is transferred at the surface of the tubes in the boiler. Next, it is conducted through the layer of the tube material and the layer of the formed deposit, and then transferred to the fluid circulating within the tubes. The present paper analyses the morphology and chemical constitution of the bound deposit taken from a boiler tube. The impact of the increase in the thickness of the bound deposit and of the loose deposit on the amount of heat transferred through the boiler walls was investigated.

The literature contains studies conducted primarily concerning deposits resulting from fuel combustion processes (coal, biomass). In this case, metal-bearing material containing, among other things, copper was examined. The combined analysis of material tests on two different deposits formed in different parts of a recovery boiler, along with thermal calculations, provides a comprehensive picture of the deposit problem and its impact on heat exchanger performance. The results provide valuable guidance for both recovery boiler designers and operators.

2. Materials and Methods

The study analysed the deposit forming on the heat exchanger tubes. The morphology and chemical constitution of the deposit were analysed. The quantitative analysis was carried out with the X-ray fluorescence method (XRF), mineralogical and lithological analysis with scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and phase analysis with the X-ray diffraction method (XRD). Tests were carried out on a deposit taken from the radiation zone of the waste heat recovery boiler (

Figure 1). The tested deposit showed a distinct laminar structure. Therefore, the deposit was divided into three layers: 1/1 (tube side), 1/2, and 1/3 (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), differing in the phase constitution and in the form and size of the crystals. Layer 1/2 was further divided into two sub-layers, A and B. The laminar structure is caused by a gradual increase in the surface temperature of the growing deposit, which results in changes in the process of fly ash settling and changes in the deposited material, i.e., grain growth and recrystallization.

The chemical constitution of the deposit is the same as that of the dust that forms it, but the content of the individual chemical substances varies. The results of the quantitative analysis of the chemical constitution of the whole sample showed the following contents in the deposit: Cu (26.1%), S (21.6%), CaO (12.5%), SiO2 (8%), K2O (7.4%), As (6.5%), MgO (4.7%), Pb (5.5%), Zn (0.5%), Fe (1.9%), and others. These values are higher than those observed in the dust, in particular for Cu (almost doubled) and K2O, MgO, and As (multiple growth), except Zn and Fe, where you can observe a decline in the content in the deposit compared to the flash furnace dust.

Deposit layer 1/1 is primarily built of copper sulphates and lead sulphates, i.e., chalcocyanite, anglesite, and palmierite. A similar composition for the radiation screen surface was observed in [

7]. Chalcocyanite forms clusters of small (<25 μm in length) automorphic crystals (

Figure 4a). The anglesite crystals are also properly formed, but their size is noticeably larger, especially at the boundary with the 1/2 A central sub-layer, which comprises their band (

Figure 5a). The other phases are very finely crystalline. The temperature conditions in this layer allowed the material to undergo extensive condensation, recrystallization, and grain growth. These processes lead, on the one hand, to a reduction in the primary layer thickness and, on the other hand, to building up an ash layer on the surface, with large grain sizes and a better contact surface between them [

15].

The 1/2 A sub-layer primarily comprises anhydrite, copper, and potassium sulphates, as well as langbeinite (

Figure 5b). Anhydrite and langbeinite form the background, as the main mass of the zone, with mixed in small (<30 μm in length) but very abundant automorphic crystals of copper and potassium sulphates adopting a pseudo-rhombohedral shape (

Figure 4b).

The 1/2 B sub-layer mainly comprises anhydrite forming the background and properly formed lammerite crystals (

Figure 5c). Lots of fine-grained silica appear in this zone in the form of impregnation in other phases and the filling of cracks in anhydrite. Alarsite also occurs next to lammerite. An intermediate phase also occurs: urusovite (

Figure 4c). Phases such as palmierite, anglesite, tenorite, or langbeinite are rare, and only traces of them are found.

The boundary between the central sub-layer 1/2 B and the external zone 1/3 is not as clear as the previous ones. It can be subjectively determined from the place where spinels begin to occur in the sample. These phases usually have a similar composition to cuprospinel CuFe

2O

4, with the addition of aluminium. Spinels occur in the form of numerous small octahedrons (

Figure 4d). They are dispersed in the main phases comprising this zone—anhydrite and potassium feldspar—and mixed with fine-grained silica. Copper arsenate and copper oxide—tenorite—appear on the edges of potassium feldspar grains. Iron oxide grains with an admixture of titanium were observed in several places near silica and spinels. Copper arsenate occurs less frequently than in the central 1/2 B sublayer, while automorphic crystals of aluminium-copper arsenate (urusovite) appear. With regard to other phases, the presence of anglesite was observed.

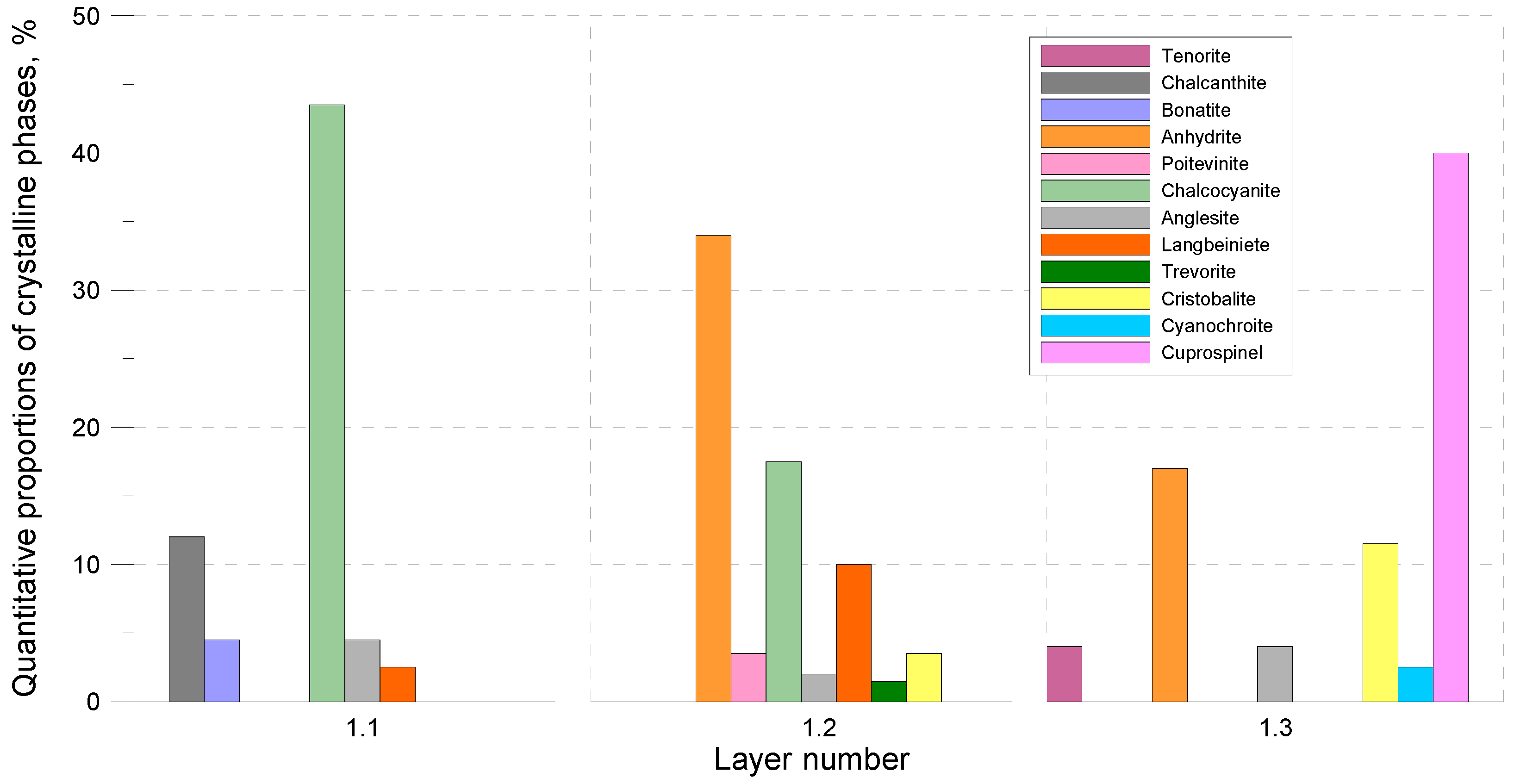

XRD analysis showed that, in the 1/1 layer, sulphates, i.e., chalcocyanite (more than 40 wt.%), chalcanthite, and yavapaiite, prevail in the phase constitution. Anhydrite, chalcocyanite, and langbeinite prevail in the central 1/2 layer. Cuprospinel, anhydrite, and cristobalite prevail in layer 1/3 (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

Depending on the zone, copper is concentrated in various phases. In layer 1/1 and sublayer 1/2 A, this metal is bound in various sulphates, mainly in chalcocyanite CuSO4. In sublayer 1/2 B, copper is in the structure of arsenates, mainly in lammerite Cu3(AsO4)2. In sublayer 1/3, copper is primarily in the structure of cuprospinels, secondarily in arsenates and sulphates. Silica, absent in layer 1/1, gradually increases its proportion towards the outer side of the sample. As the distance from the contact surface of the deposit and the tube increases, the proportion of oxides increases, in particular in layer 1/3. Iron is mostly concentrated in layer 1/3, in the structure of spinels. In other areas, this metal appears in sulphates. In layers 1/2 and 1/3, arsenic compounds occur. Automorphic crystals of many phases, in particular of arsenates, spinels, and chalcocyanite, suggest that they have crystallised at a slow, stable rate.

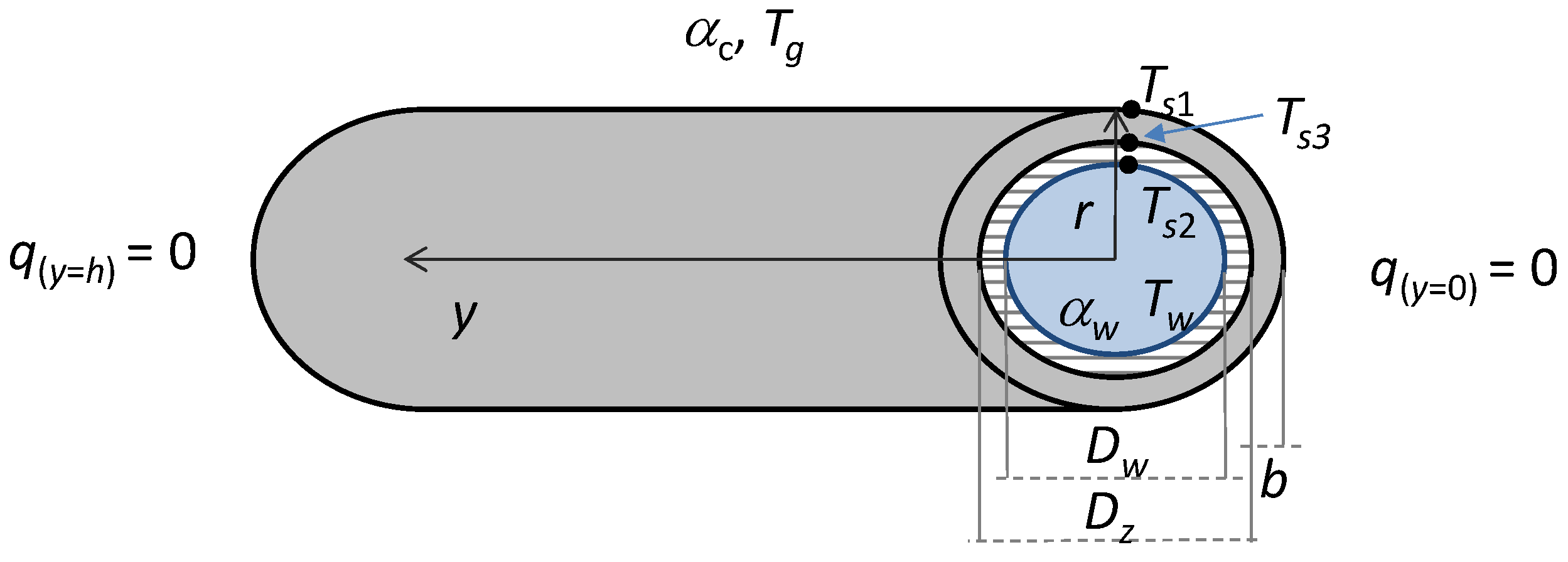

3. Numerical Computing

The temperature distribution of heat exchanger tubes in the waste heat recovery boiler was computed with the finite element method using an axi-symmetrical solution of the heat conductivity equation. The computing was carried out for a clean tube surface and for a case with loose and bound deposits present on the surface with thicknesses of 0.5 cm, 1 cm, and 2 cm. The applied finite element method is described in [

16]. On both sides of the tube surface, the second boundary condition was assumed (

Figure 8). The density of heat flux transferred between the post-process gas and the outer surface of the tube was calculated from the equation

The amount of heat transferred between the inner surface of the tube and the water was computed from the equation

where

Ts1—tube outer surface temperature, °C;

Ts2—tube inner surface temperature, °C;

Tg—post-process gas temperature, °C;

Tw—water temperature, °C;

αw—heat transfer coefficient on the water surface, W/(m2∙K);

αc—overall heat transfer coefficient at the boiler furnace side, W/(m2·K).

The computing was performed for the following assumptions:

The post-process gas temperature at the deposit formation place tg was 800 °C;

The water temperature tw was 260 °C;

The initial temperature of the internal and external surface Ts1 and Ts2 of the tube, without a deposit and with a deposit, was 250 °C;

The overall heat transfer coefficient αc changed from 100 W/(m2·K) to 300 W/(m2·K);

The heat transfer coefficient

αw was 10 kW/(m

2·K) [

17,

18].

The ranges of heat transfer coefficients assumed in the computing arise from the possibility of different operating conditions of the waste heat recovery boiler, as well as its unstable operation, and the change in the heat transfer conditions associated with the occurrence of a deposit. For the numerical computing, it was assumed that the heat exchanger tubes were made of boiler steel P265GH, with a size of Φ38 × 6.3 mm. The thermophysical properties of the steel are given in [

19]. The literature contains very little data on the thermal conductivity, specific heat, and density of deposits containing copper oxides. The authors in [

7] determine the change in the thermophysical properties of the deposits taken from various parts of the boiler. Bound deposits that have been exposed to high temperatures for a prolonged time and that have undergone sintering and melting processes, as well as loose deposits, were tested. For the bound deposits, the thermal conductivity coefficient ranged from 1.3 W/(m·K) to 1.8 W/(m·K) within the temperature range of 20 °C to 300 °C, and the specific heat ranged from 700 J/(kg·K) to 1000 J/(kg·K) within the temperature range of 300 °C to 800 °C. For the loose deposits, the thermal conductivity coefficient ranged from 0.2 W/(m·K) to 0.8 W/(m·K), and the specific heat had similar values. The thermal conductivity of both deposits was different because of structural changes and porosity. In the present study, the average values of thermal conductivity coefficient and specific heat provided in [

7] were assumed for numerical computing. The thermal conductivity of the bonded deposit was 1.5 W/(m·K), with a density of 3200 kg/m

3, and a specific heat of 750 J/(kg·K). In the case of the loose deposit, the thermal conductivity coefficient was 0.5 W/(m·K), the density was 2000 kg/m

3, and the specific heat was 750 J/(kg·K). The accuracy of the FEM solution used for modelling the temperature field was documented in [

16,

20]. The solution has been verified by comparison of the numerical results to those obtained from the analytical solution. A good correlation between the solution and numerical results has been obtained.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this study was to characterise the deposits formed from the dust carried over from the flash furnace to the waste heat recovery boiler and to determine their influence on the heat transfer through the boiler walls.

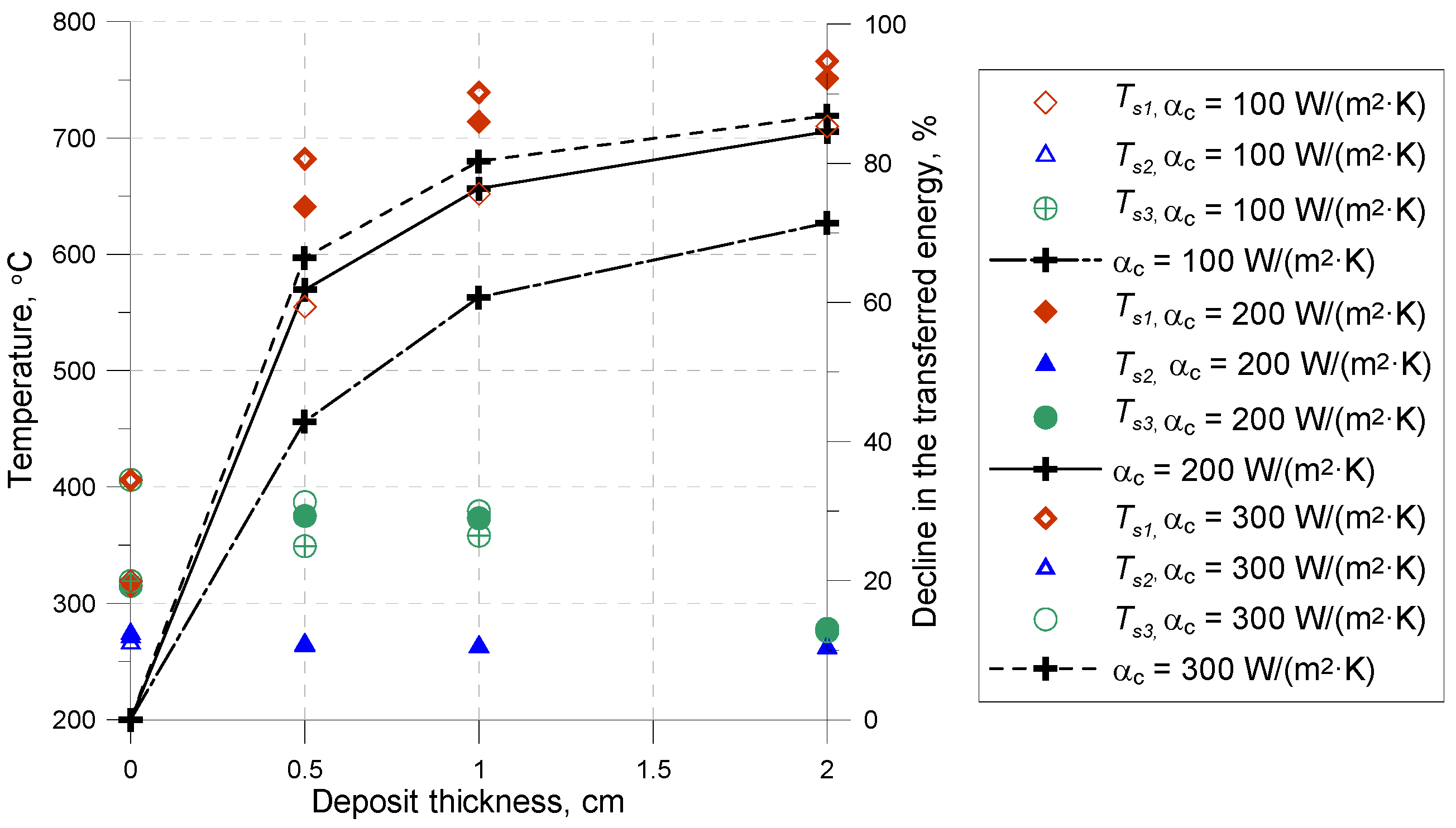

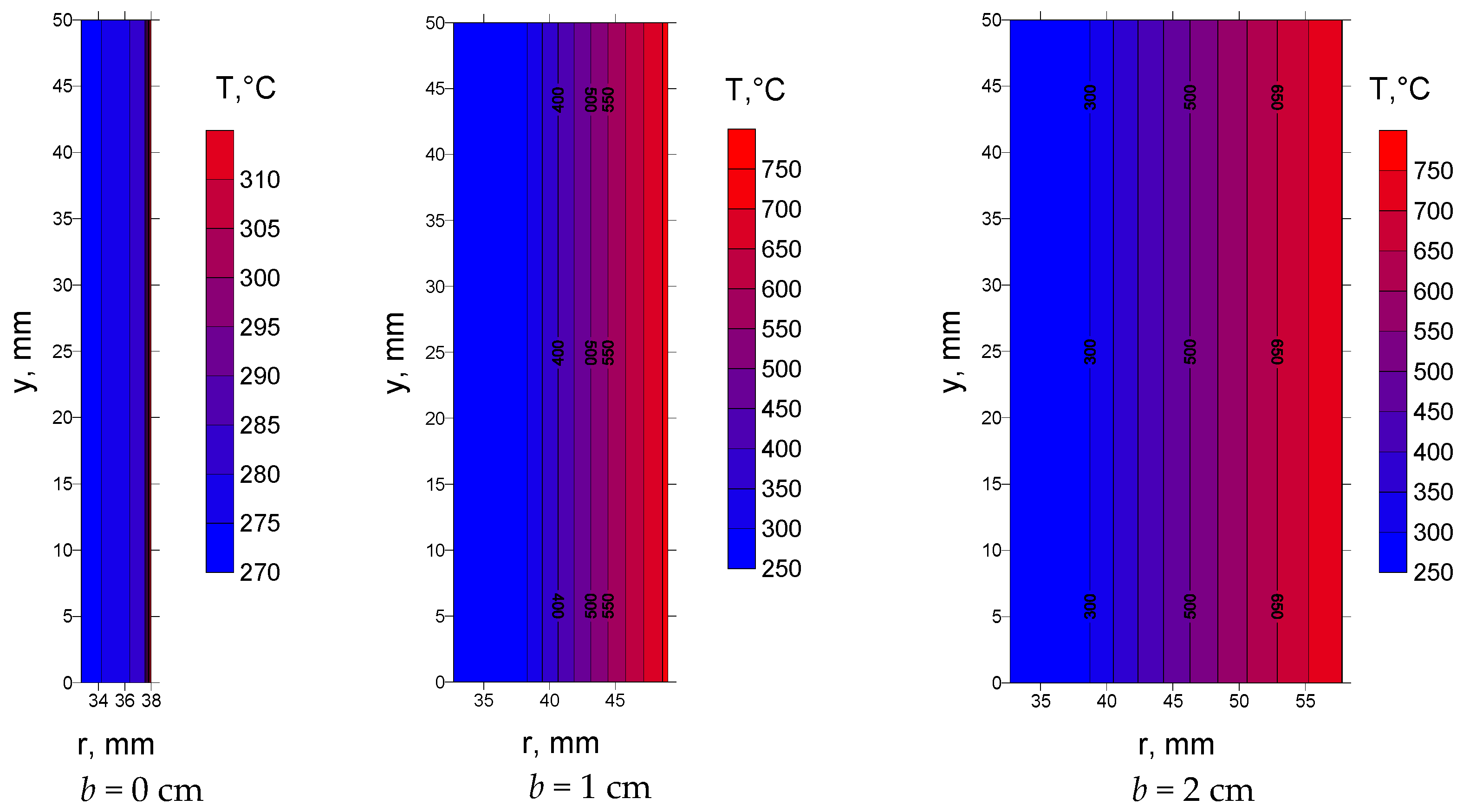

It was established that after depositing the first layer of sulphates doped with low-melting constituents, further phase transitions in dust result from the temperature conditions of the deposited layer, which in turn are conditioned by the flux of the thermal energy being transferred.

The temperature difference in the deposit cross-section depends on the type and thickness of the deposit, as well as on the overall heat transfer coefficient on the side of the boiler chamber.

For the loose deposits with a thickness of 0.5 cm, the decline in the heat transferred was similar to the values obtained for the bound deposit with a thickness of 2 cm. It was established that, for a deposit with a thickness of 20 mm, there was an approximately 80% decline in the energy transferred by the walls compared to the clean tube surface.

The accurate prediction of the deposit properties, depending on the fuel, boiler design, and its operating conditions, is the most important area for which further research is necessary.