1. Introduction

Solar energy is increasingly being utilized on a global scale, largely because it stands out as an abundant and environmentally sustainable renewable option. As a key candidate to meet future energy demands, photovoltaic (PV) power generation has attracted significant attention in modern power grids for its efficient use of solar energy. It is projected that by 2025, PV generation will supply one-quarter of the world’s electricity demand [

1]. However, the intermittent nature of solar energy necessitates that the generated electricity be either consumed immediately or stored in costly battery systems. To maintain a stable energy supply and enable effective resource planning, achieving high accuracy in PV power forecasting is critical.

The primary approaches for predicting PV power currently encompass physical models, statistical and probabilistic methods, and machine learning models. Physical models do not rely on historical data but rather compute PV power output directly using meteorological information (e.g., weather forecasts, satellite cloud maps) and system parameters such as PV panel installation angles and surface temperatures. In studies based on physical modeling, Zhi et al. [

2] constructed a model based on physical principles for PV power forecasting, which incorporates both meteorological parameter prediction and an enhanced MPPT algorithm. Experimental results under various weather conditions demonstrated low prediction error, thereby improving both accuracy and applicability. El Ainaoui et al. [

3] introduced new mathematical formulations using implicit single-diode models (SDM) and explicit Das models (DM) to describe variations in model parameters with temperature and irradiance. Field tests at the Moroccan Green Energy Park showed that their method could effectively predict PV performance, achieving an NRMSE below 4.16%, contributing to PV system optimization and enhanced grid stability. Zaimi et al. [

4] proposed two new techniques for identifying the physical parameters of single-diode circuit models, which rely on establishing correlations between key photovoltaic indicators and quality factors. Manufacturer data were utilized to determine temperature and radiation coefficients, investigating the influence of environmental factors on model parameters. Testing on KC130GT and SM55 photovoltaic panels validated the effectiveness of the methods and models, providing support for photovoltaic system performance prediction. Tifidat et al. [

5] proposed a novel simulation approach for PV module performance based on the single-diode model. By combining numerical and analytical techniques, they reduced the number of unknown parameters and eliminated the need for approximation and iteration, relying only on data under standard test conditions and simplifying the modeling process. Comparative experiments on PV modules using various technologies showed lower error and faster convergence compared to other methods, providing an effective tool for dynamic performance evaluation and design. Although physical modeling does not require historical data and is applicable to any prediction horizon, it faces practical challenges. A major constraint is the need for highly detailed, site-specific parameters tailored to large-scale PV plants, which makes these models less suitable for residential rooftop PV systems [

6]. Furthermore, compared to data-driven methods, physical models demand more domain knowledge, as they rely on solving complex differential equations based on mathematical descriptions of photovoltaic conversion. This not only imposes high computational costs but also leads to longer runtimes to achieve accurate results. Despite a solid understanding of the underlying physical phenomena and accurate modeling, even mature and well-studied models can introduce errors [

7]. Many fail to account for localized effects such as system faults, cloud movement, partial shading, or snow accumulation—factors that data-driven methods are better equipped to handle [

8].

Statistical approaches rely on the analysis of historical data to construct a functional relationship between past and predicted values. Classical statistical techniques such as vector autoregression (VAR) [

9] and autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models [

10] were dominant in early studies. Li et al. [

11] proposed an autoregressive moving average model with exogenous inputs (ARMAX), incorporating meteorological features to forecast power output. By using easily obtainable parameters such as temperature, precipitation, sunshine duration, and humidity, the model retained the simplicity of ARIMA without relying on solar irradiance forecasts. It also proved to be more general and flexible in practical applications. Based on real-world data from a 2.1 kW grid-connected PV system, the ARMAX model significantly outperformed ARIMA in prediction accuracy. Despite advantages such as structural simplicity and fast computation, statistical models struggle to capture the volatile and dynamic nature of PV data, limiting their predictive performance [

12].

In recent years, machine learning has been widely applied in PV power forecasting due to its ease of modeling, high accuracy, and strong generalization capability. Sulaiman et al. [

13] successfully applied neural network (NN) models for forecasting the power generation of rooftop PV systems. The authors reported superior accuracy and consistency over alternative approaches. For day-ahead forecasting in a real microgrid, an integrated model (WT-PSO-SVM) was formulated by Eseye et al. [

14], which merges wavelet transform, particle swarm optimization, and support vector machine. Wavelet transform was used for preprocessing, and particle swarm optimization for hyperparameter tuning, resulting in improved prediction performance. Wolff et al. [

15] evaluated support vector regression (SVR) against physical models by utilizing a fused dataset, which included PV power observations, numerical weather prediction (NWP), and cloud motion vector (CMV) information. SVR showed excellent performance in real microgrid environments. Machine learning models have shown significant promise for PV forecasting; however, their effectiveness is often constrained when it comes to fully modeling the intricate nonlinear dynamics between weather conditions and PV power. It often struggles to capture dynamic phenomena such as sudden cloud cover changes and component degradation, and lacks long-range modeling capabilities, which constrain further accuracy improvements. Overcoming these limitations calls for models with stronger feature extraction and time-series modeling capabilities, paving the way for deep learning applications in PV forecasting.

Owing to its powerful strengths in feature extraction, nonlinear modeling, and generalization, deep learning has emerged as an increasingly prominent subfield of machine learning. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

16] are frequently applied to time-series prediction problems. Lee et al. [

17] utilized two types of RNNs to forecast PV power without requiring future meteorological information, achieving better results than traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs) and deep neural networks (DNNs). However, RNNs suffer from long-term dependency issues, leading to vanishing or exploding gradients. Hochreiter et al. [

18] presented the long short-term memory (LSTM) network to tackle this issue. By leveraging a mechanism of input, forget, and output gates plus a memory cell, the LSTM network effectively overcomes long-term dependency issues, making it a broadly applied tool in PV forecasting. Hu et al. [

19] further combined LSTM with self-attention mechanisms, integrating historical and forecast data. Their model, tested on real PV data from a building in Japan, exhibited strong accuracy and adaptability. Ahmed et al. [

20] proposed an efficient and practical integrated forecasting method combining LSTM with live data from the Yulara PV plant in Australia. Other commonly used deep learning models include gated recurrent units (GRUs) [

21] and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

22]. Dai et al. [

23] used LOWESS smoothing to extract PV features and proposed a CNN-BiGRU-Attention hybrid model optimized via ensemble learning. Chen et al. [

24] employed a multi-task learning (MTL) scheme for TPA-LSTM to jointly forecast wind–solar. Their approach utilized the maximal information coefficient for feature selection and wind–PV correlation analysis. The MTL framework’s innovation lay in separating shared and task-specific components, which was further enhanced by a novel loss strategy balancing training speed and loss magnitude. Qu et al. [

25] introduced an attention-based long- and short-term memory prediction model (ALSM) under a multi-related and target-variable prediction (MRTPP) scheme. The model combines CNN, LSTM, and attention mechanisms and was validated using historical PV system data from the DKSCA website. Results showed that the MRTPP-based ALSM outperformed traditional input–output schemes and various statistical and AI-based forecasting methods. Furthermore, improved LSTM-based algorithms are widely adopted in PV power forecasting. Bi-LSTM’s bidirectional learning enhances accuracy and convergence speed in time-series tasks [

26,

27], while GRU, by simplifying LSTM’s gate structure into a unified update gate, offers fewer parameters and easier training, contributing to its popularity [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

In summary, while existing PV power forecasting methods have addressed many challenges, several issues remain. First, physics-based methods suffer from low prediction accuracy, poor generalization, and complex parameterization. Traditional statistical methods are inadequate in capturing key PV data characteristics. Moreover, conventional machine learning models are prone to gradient issues under long-term dependencies. Although hybrid models combining various algorithms have become mainstream in PV forecasting, they often focus solely on model structure, neglecting the role of meteorological data analysis. In response to these limitations, a deep learning-based PV power forecasting model that integrates similar-day clustering is proposed in this study, whose structure is illustrated in

Figure 1. The main contributions are as follows:

- −

To enhance the model’s adaptability in complex meteorological scenarios, the PV dataset is first processed using a K-medoids clustering algorithm based on Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) distance. This method allows the model to fully account for the impact of varying weather conditions on power generation.

- −

The TimeGAN algorithm is employed to generate synthetic data samples under extreme weather conditions, aiming to mitigate model underfitting and enhance the model’s robustness in such scenarios.

- −

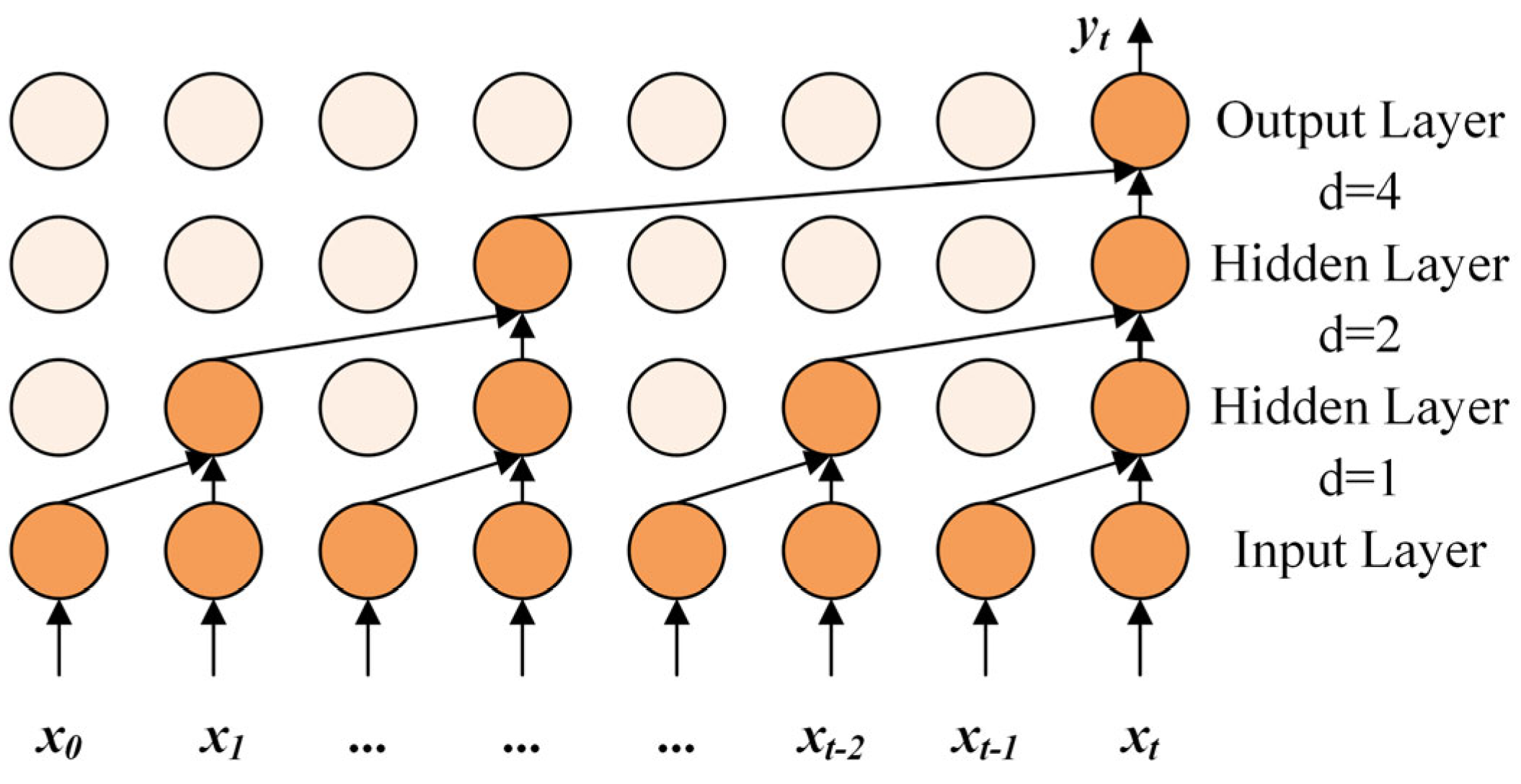

The BiTCN and BiGRU algorithms are integrated to fully leverage their bidirectional structures for capturing latent information within the sequences. Meanwhile, to address the issue of excessive hyperparameters, the AOO algorithm is employed to optimize these parameters, thereby improving prediction accuracy and reducing manual tuning efforts.

- −

The superior performance of the proposed method for photovoltaic power forecasting is validated through a comparative analysis against other models, utilizing Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and R2 as the evaluation indicators.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows:

Section 2 covers the theoretical foundations of the employed methods and the proposed model.

Section 3 is then dedicated to the case study, data, and preprocessing.

Section 4 describes the modeling process and presents a comprehensive analysis of the results. Lastly,

Section 5 recaps the principal findings of this study and proposes potential avenues for subsequent research.

3. Data Analysis and Parameter Configuration

This section outlines the dataset employed in this study, the comparative methodology, evaluation metrics, parameter configurations, and feature relevance analysis. Furthermore, the experimental hardware configuration comprises a 3.7 GHz Intel® CoreTM i9-10900K CPU, 96.00 GB of memory, and an NVIDIA® GeForce RTX™ 5060 Ti graphics card. The TimeGAN algorithm was implemented in Python 3.10.15based on the PyTorch 2.7.0 framework with CUDA 12.8 support, whilst clustering and prediction algorithms were realized using MATLAB 2023a.

3.1. Data Information

The data for this study were sourced from figshare, a website that publicly shares various datasets [

39]. The solar data was sourced from the China State Grid Renewable Energy Generation Forecasting Competition. This dataset originates from a 30 MW nominal capacity solar power station.

Table 1 and

Table 2 illustrates its key characteristics. The dataset spans the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019, with a resolution of 15 min. Detailed feature information is presented in

Table 1. Energy peaks around midday, with relatively lower levels at sunrise and in the afternoon, tending towards zero during night-time hours. Furthermore, a noticeable lag effect exists between certain meteorological factors and the PV data. As photovoltaic power output is zero at night, night-time data points were removed, retaining only data from 07:30 to 19:30. The dataset was subsequently partitioned into an 80% training set and a 20% validation set.

3.2. Comparative Methodology

To demonstrate the effectiveness of generated weather samples for photovoltaic power forecasting, this paper designed an ablation study comparing accuracy changes before and after data generation. Concurrently, to validate the efficacy of the AOO-BiTCN-BiGRU model for this task, we selected GRU, LSTM, TCN [

40], and CNN models for comparative analysis.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

To assess how well the predicted values matched the actual values, this study utilized three standard statistical metrics: MAE, RMSE, and the coefficient of determination (R

2) [

41,

42,

43].

The MAE quantifies the average magnitude of the errors between predicted and actual values:

The RMSE is particularly sensitive to outliers. This is because its calculation squares each error, which gives large errors a disproportionately heavy weight:

For the error metrics (MAE and RMSE), lower values signify superior predictive accuracy. Conversely, R

2 measures the quality of the model’s fit, where a value closer to 1 indicates a more accurate prediction:

where

,

, and

correspond to the actual, predicted, and mean values, respectively, and

n is the total number of samples.

3.4. Parameter Configuration

For the DTW-based K-medoids algorithm, the sequence length was set to 49 points. Based on this data structure, the number of cluster categories was set to 4.

For the TimeGAN algorithm, the detailed parameter settings are presented in

Table 3. Within this table, the middle column corresponds to the search range for each parameter, while the rightmost column indicates the final parameter values determined through experimental validation. It is worth noting that the algorithm generates a volume of synthetic samples consistent with the original dataset. To ensure comprehensive exploration of the solution space while balancing efficiency, the maximum number of iterations for the algorithm starts at 3000 and increments by 500 steps each time, ranging up to 7000.

Regarding parameter settings for the AOO-BiTCN-BiGRU model: the historical time step size is set to 49, the prediction step size to 4 (i.e., utilizing one day’s historical data to forecast the subsequent hour’s data); the filter size is set to 5; and the optimizer employs the Adam algorithm.

Dropout, a commonly used regularization technique in neural network training, primarily aims to suppress model overfitting. The selection of the Dropout rate necessitates consideration of the specific application scenario and model architecture, typically requiring cross-validation to determine the optimal value. This paper sets the Dropout rate at 0.1, a value that effectively avoids the reduced learning efficiency or underfitting issues caused by excessively high Dropout rates, while also preventing overfitting resulting from excessively low Dropout rates.

The parameter settings for the AOO optimization algorithm are as follows: population size of 4 and maximum iterations of 10. This algorithm primarily optimizes key parameters within the BiTCN-BiGRU model, specifically including the learning rate, number of neurons in the BiGRU layer, number of filters, and regularization parameters. The upper and lower limits for optimizing each parameter are detailed in

Table 4.

After AOO optimization, the final hyperparameter values used in the experiment are summarized in

Table 5. These values are derived through iterative search and verification, ensuring they match the model structure and data characteristics to maximize predictive performance.

3.5. Feature Correlation Analysis

In this study, we employed the Pearson correlation coefficient method (PCC) [

44] to analyze the degree of association between different variables. As a multifunctional analysis technique, PCC is calculated based on time-series data, focusing on linear correlations between data sequences. In the PCC calculation, we selected weather elements as the comparison series and PV output power as the baseline for comparison. The PCC calculation formula is as follows:

The PCC method was applied to calculate the pairwise correlations between seven meteorological factors and power in the original dataset, including total solar radiation (W/m

2), direct normal radiation (W/m

2), global horizontal radiation (W/m

2), air temperature (°C), atmospheric pressure (hPa), relative humidity (%), and PV output power (MW). The PCC heat map is presented in

Figure 7. Upon calculating the correlation coefficients, the degree of association between variables can be assessed via the value ranges. The heat map indicates that the factors exerting the greatest influence and exhibiting the highest correlation with PV output power are total solar radiation, direct normal radiation, and global horizontal radiation. Atmospheric pressure exerts the least influence and is therefore excluded. Consequently, the selected input variables for the model comprise total solar radiation, direct normal radiation, global horizontal radiation, air temperature, relative humidity, and PV output power.

5. Conclusions

Accurately predicting PV power on an ultra-short timescale is vital for maintaining the stable operation of the power grid and executing peak shaving and valley filling operations. Such forecasting is critical for managing the equilibrium between supply and load, as well as for optimizing energy dispatch. While single-structure models are often challenged by highly volatile data and long-range temporal relationships, composite-structure models generally yield superior accuracy. The latter achieves this by utilizing more intricate neural network architectures capable of learning complex features and data patterns. To address this, our study enhances ultra-short-term PV forecasting accuracy by constructing a hybrid prediction model. This model integrates clustering, optimization, generative adversarial networks, and deep learning methods, thereby achieving high-precision forecasting and robust performance evaluation.

The main conclusions drawn from this work include:

A hybrid PV power forecasting model was developed that fully accounts for the influence of varying weather conditions on PV output. To significantly boost the model’s accuracy and adaptability across complex meteorological conditions, multi-dimensional meteorological data (such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar irradiance) along with historical PV power data were incorporated.

Data generation via the TimeGAN algorithm mitigates model underfitting, thereby enhancing robustness under extreme weather conditions. Exploration of model parameter optimization methods reduces complexity and computational efficiency, ensuring practical feasibility for real-world forecasting.

Validation and evaluation using operational data from actual PV power plants analyzed prediction accuracy and reliability across different seasons and weather conditions. Comparative analysis assessed the hybrid model’s advantages over single-method approaches, providing a more reliable tool for PV power forecasting in photovoltaic-storage integrated charging stations.

In summary, the integrated PV power forecasting algorithm proposed herein achieves a higher level of accuracy compared to the other models. Its consideration of weather factors and generation of extreme weather samples significantly enhances PV power prediction accuracy, holding substantial practical value and real-world significance. Future research may deepen the exploration of the following areas: firstly, expanding data dimensions to incorporate PV module status (real-time temperature, dust coverage, degradation level) and regional microclimate data to reduce prediction errors; secondly, integrating reinforcement learning to optimize model parameter update mechanisms, enabling online adaptive optimization and enhancing long-term operational stability; thirdly, integrating the model with energy management strategies for photovoltaic-storage systems to construct an integrated ‘prediction-scheduling’ decision model, thereby facilitating renewable energy integration.