Multi-Time Scale Optimal Scheduling of Aluminum Electrolysis Parks Considering Production Economy and Operational Safety Under High Wind Power Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Power Regulation Characteristics of Electrolytic Aluminum Loads

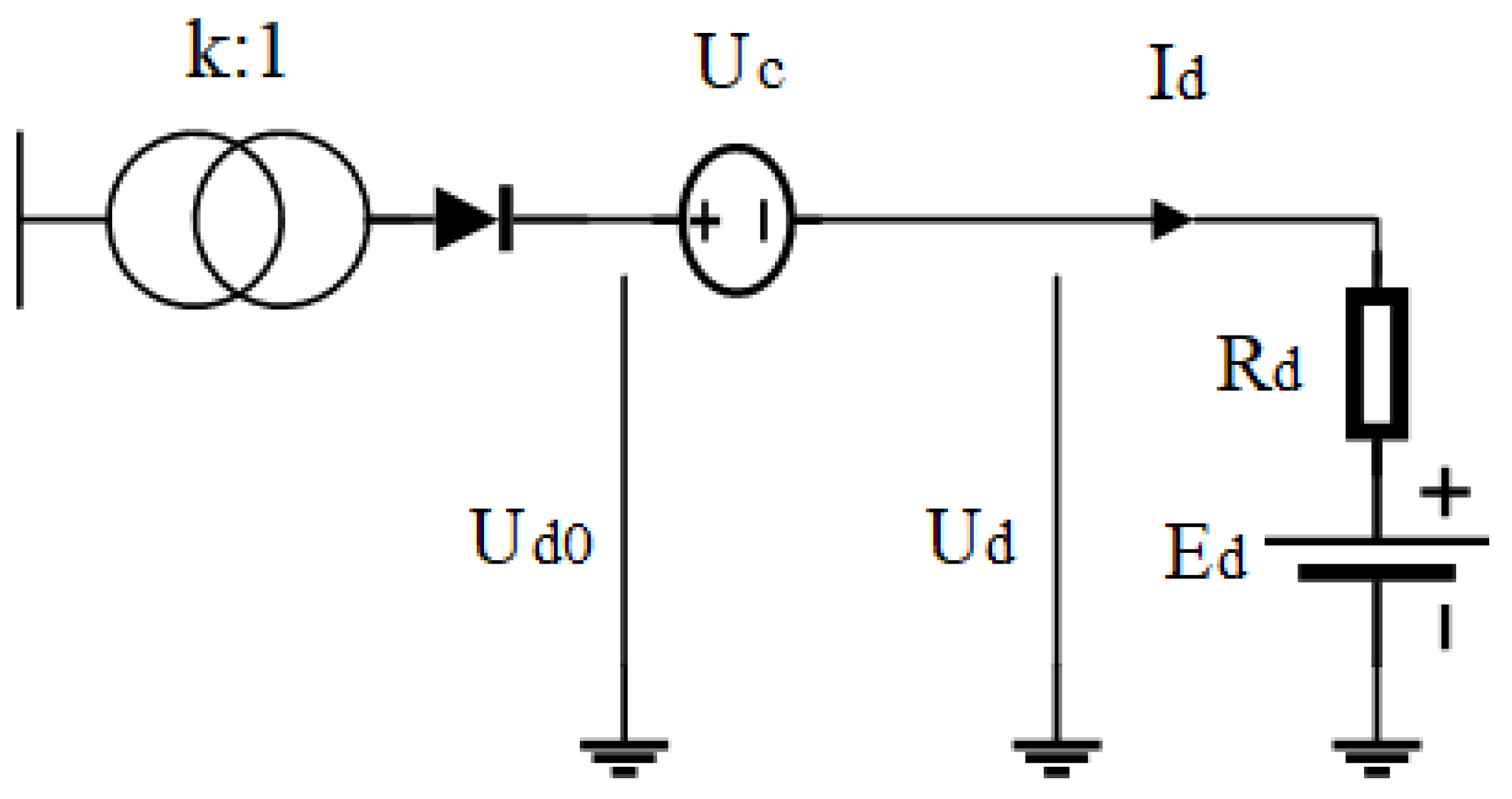

2.1. Principle of Power Regulation for Electrolytic Aluminum Loads

2.2. Power Regulation Model for Electrolytic Aluminum Loads

2.2.1. Constraints

- (1)

- Minimum On/Off Time Constraints.

- (2)

- Constraint on the Voltage Drop Range of the Saturable Reactor.

- (3)

- Production Safety Constraints for the Electrolytic Cell Series [25].

- (4)

- Temperature Constraints

- (5)

- Ramp Rate Constraint

- (6)

- Regulation Time Constraint

- (7)

- The Number of Adjustments Constraint

2.2.2. Regulation Cost of Electrolytic Aluminum

- (1)

- Production Loss Cost

- (2)

- Temperature Penalty Cost

3. Multi-Time Scale Scheduling Model

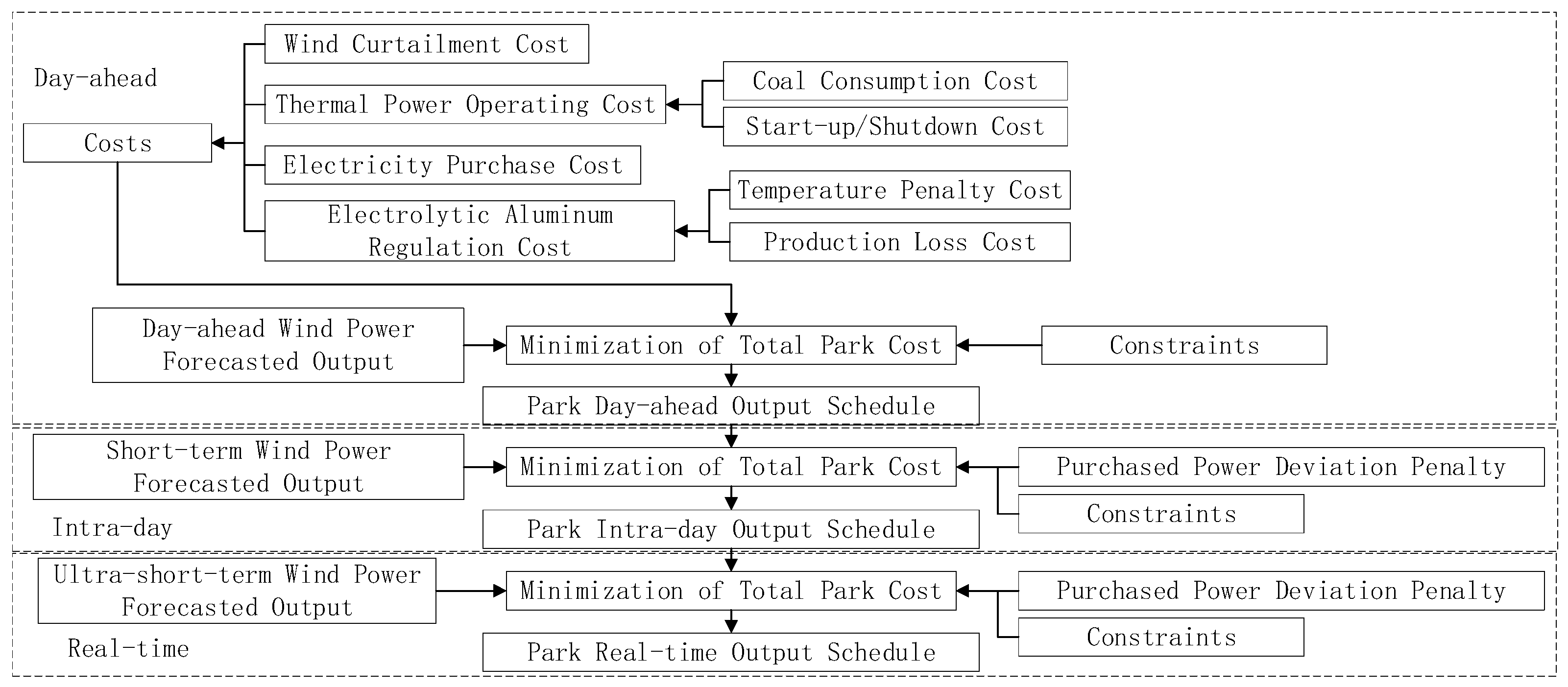

3.1. Scheduling Framework

3.2. Day-Ahead Scheduling Model

3.2.1. Objective Function

3.2.2. Constraints

- (1)

- Power Balance Constraint

- (2)

- Thermal Power Unit Constraints

- (3)

- Wind Power Grid Integration Constraint

- (4)

- External Grid Purchased Power Constraint

- (5)

- Electrolytic Aluminum Constraints

3.3. Intra-Day Rolling Dispatch Model

3.3.1. Objective Function

3.3.2. Constraints

3.4. Real-Time Dispatch Model

3.4.1. Objective Function

3.4.2. Constraints

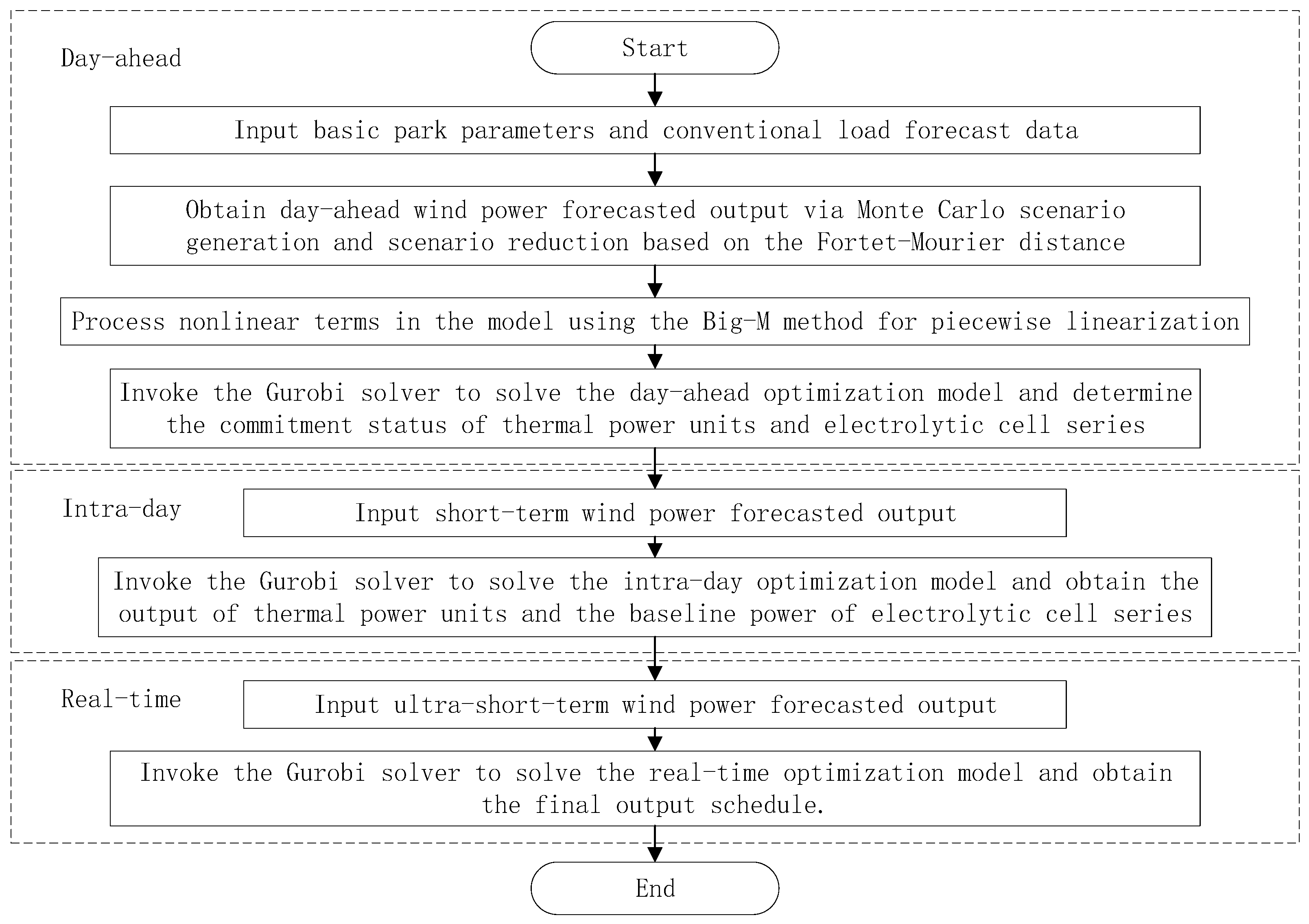

4. Model Solution

4.1. Handling Wind Power Uncertainty

4.1.1. Wind Power Scenario Generation and Reduction

- (1)

- Randomly select k scenarios from the initial set as the initial representative scenarios.

- (2)

- Calculate the Fortet–Mourier distance between all scenarios and the current representative scenarios. Assign each scenario to the cluster whose representative scenario is the nearest neighbor. The Fortet–Mourier distance can be expressed as:

- (3)

- For each of the clusters, calculate the distances between all scenarios within the cluster and select a new representative scenario for which the sum of distances to all other scenarios in the cluster is minimized.

- (4)

- When the clustering results no longer change, the final representative scenarios are obtained. Their probability weights are determined by the number of scenarios in their respective clusters.

4.1.2. Robust Optimization of Wind Power

4.2. Multi-Time Scale Solution Procedure

5. Case Study

5.1. Basic Data

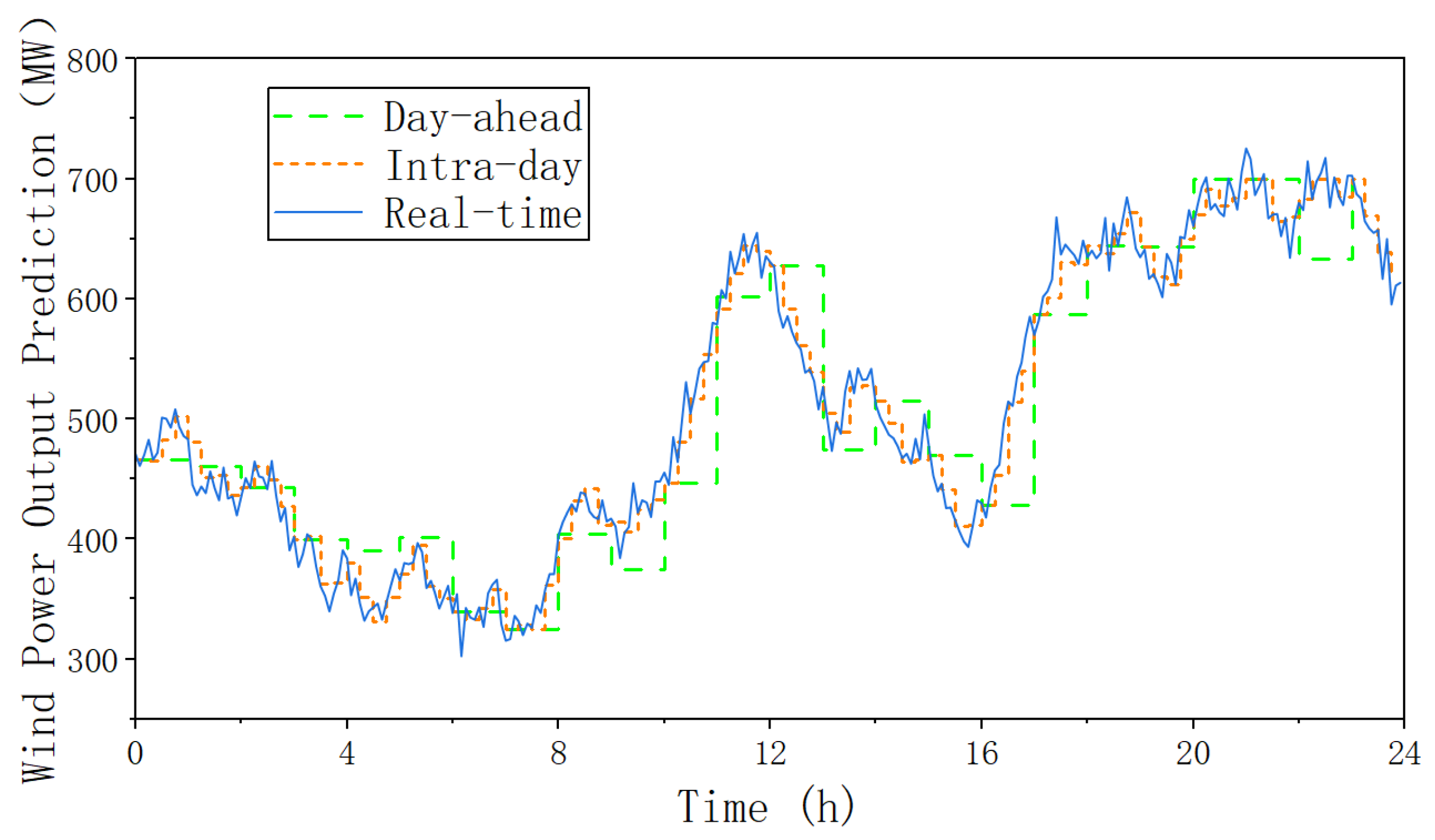

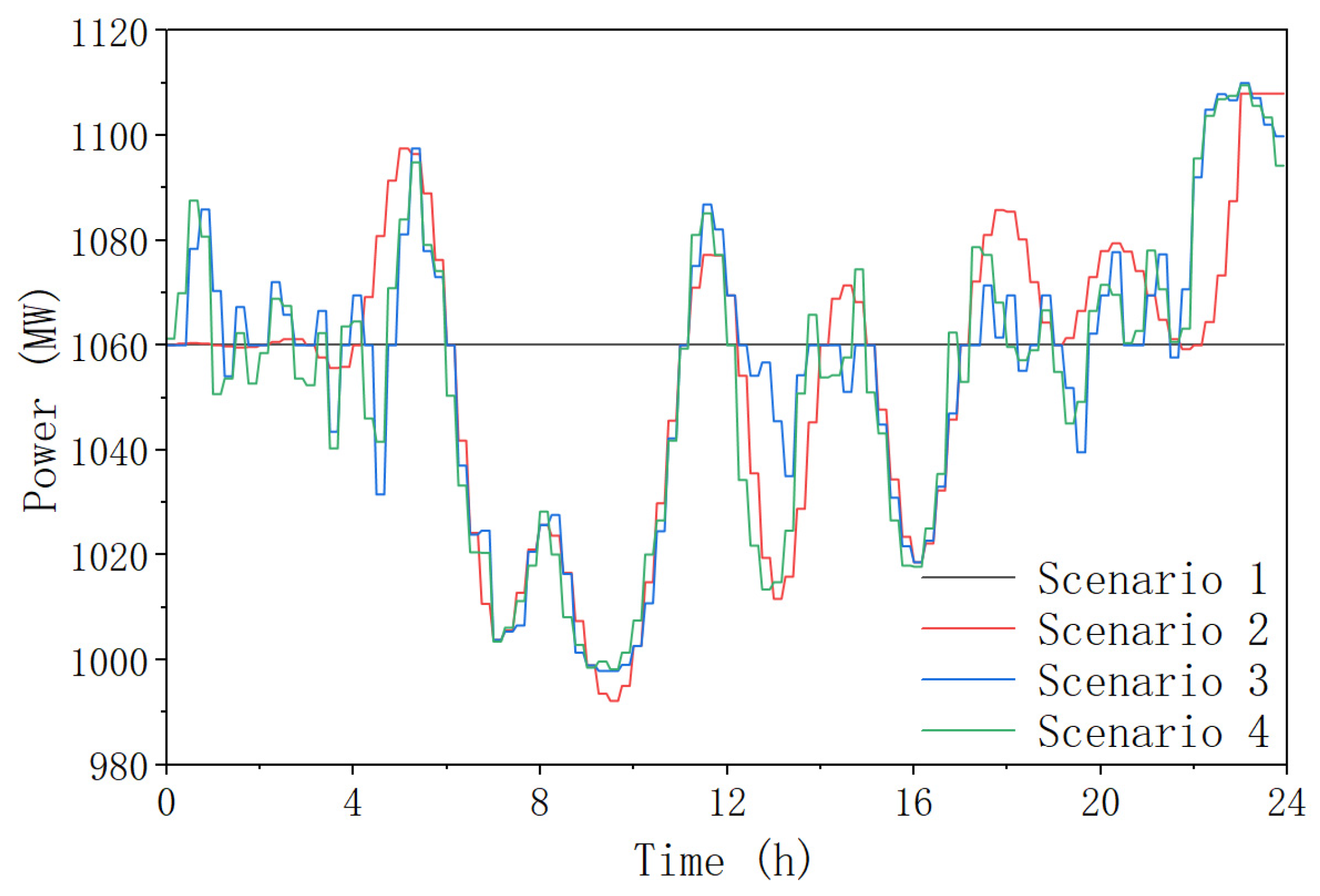

5.2. Multi-Time Scale Scheduling Results

5.3. Wind Power Robustness Validation

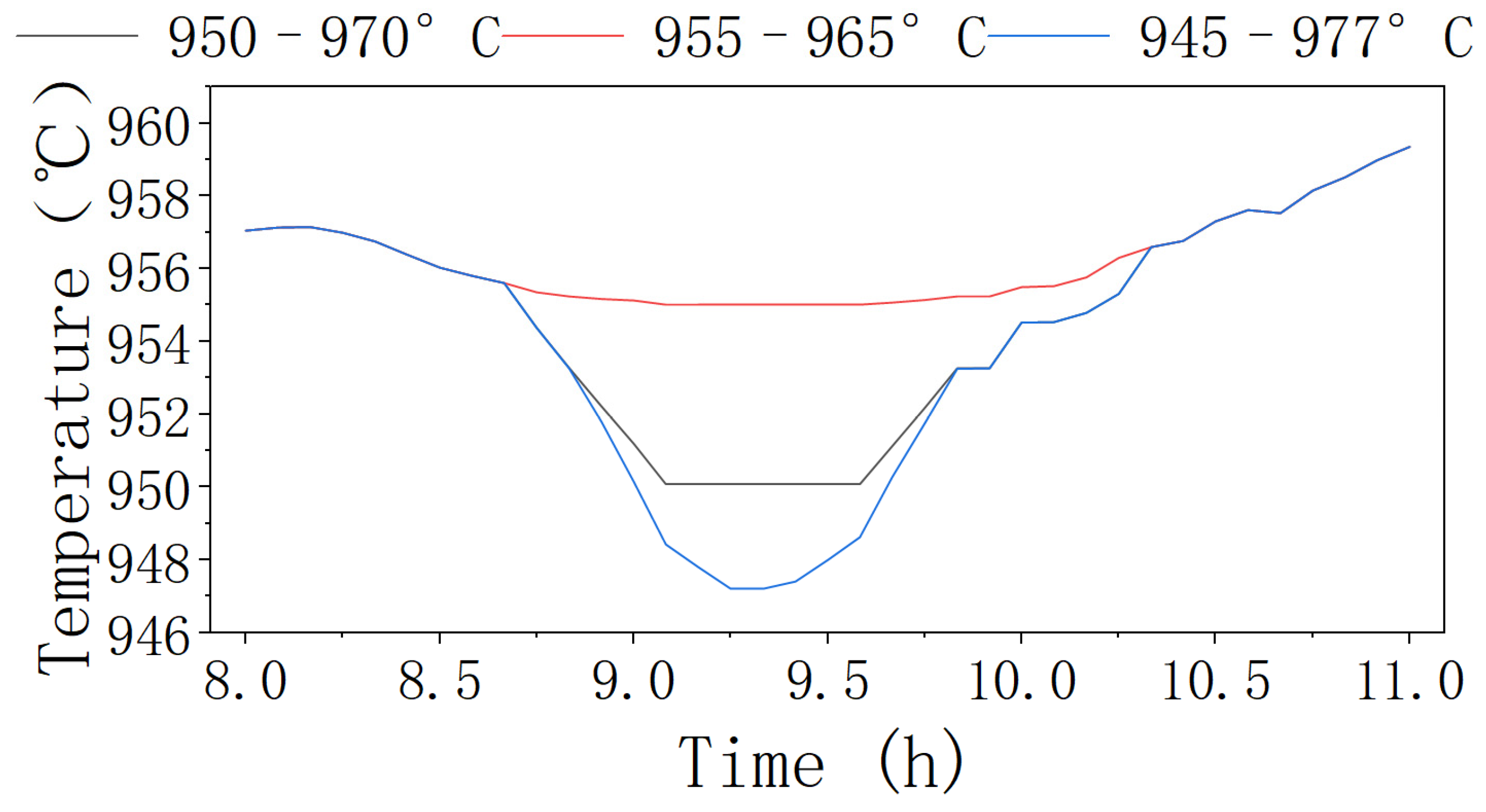

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Temperature Constraint Variations

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Electricity Price Fluctuations

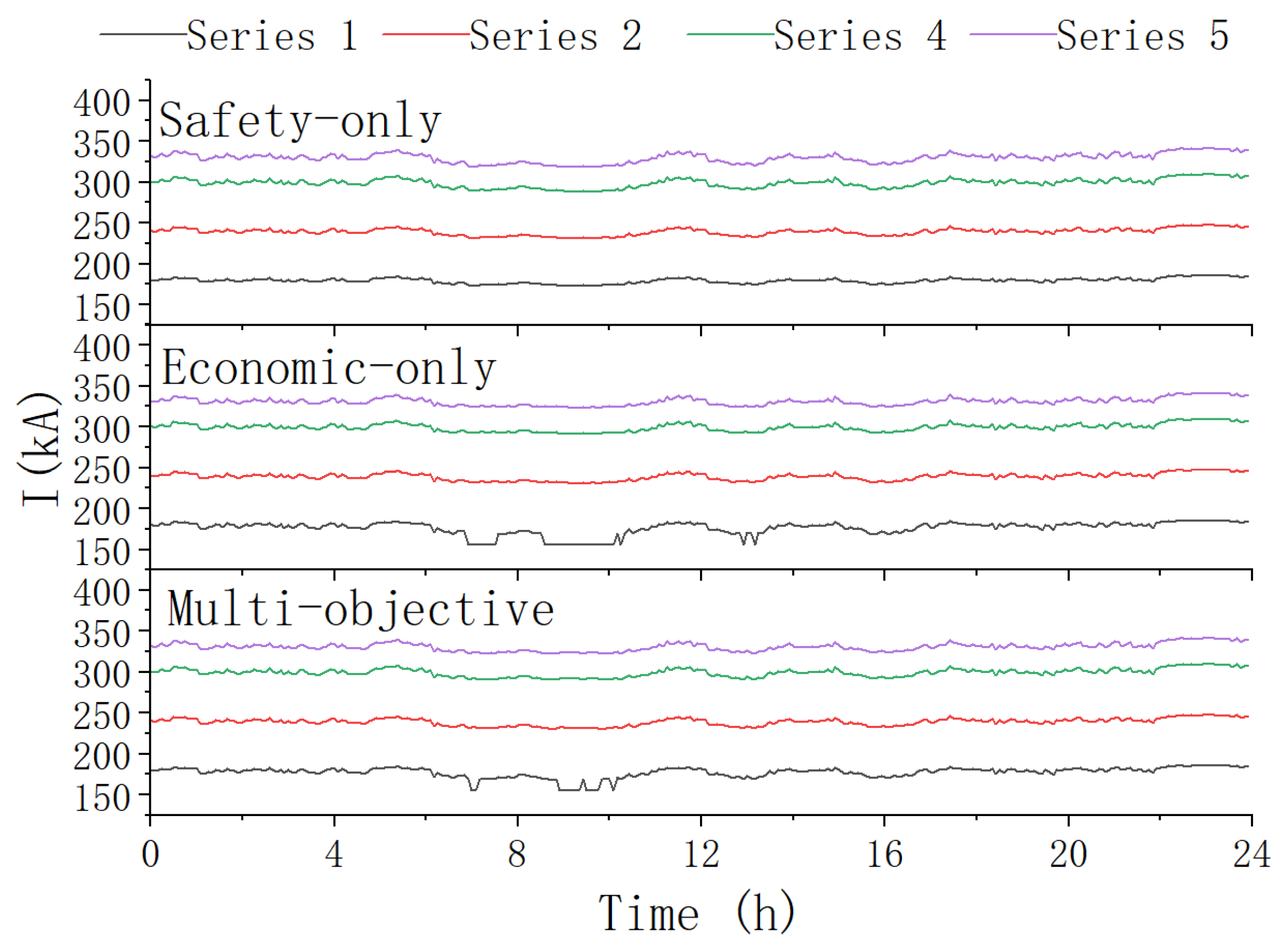

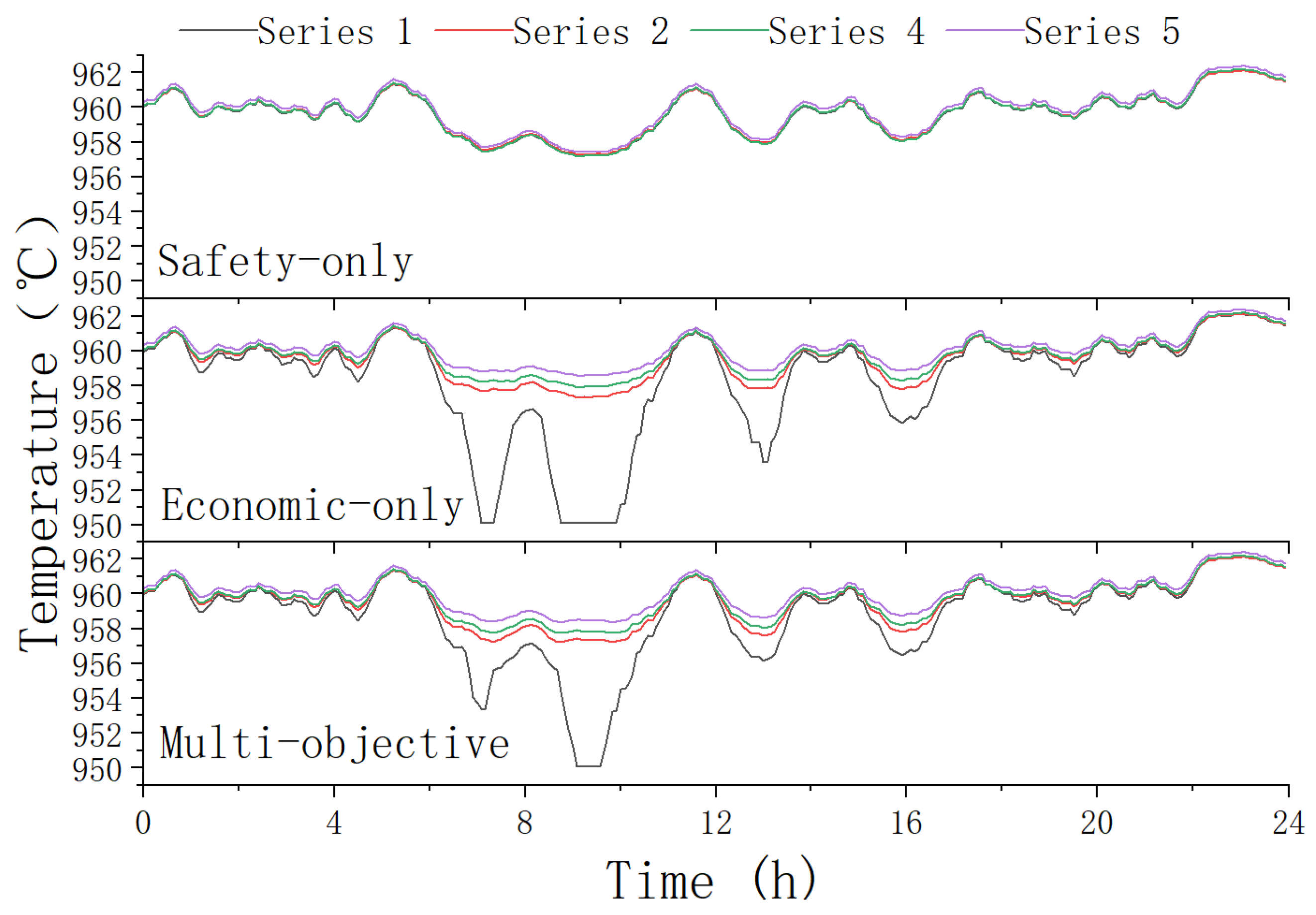

5.6. Analysis of Electrolytic Aluminum Regulation Under Different Objectives

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The integration of aluminum electrolysis loads into day-ahead, intra-day, and real-time optimal scheduling enhances the flexibility of the power system, facilitates the consumption of renewable energy, and reduces the total operating costs.

- (2)

- The developed multi-objective regulation model for aluminum electrolysis effectively balances the trade-off between economic cost and production safety, thereby ensuring the economical and secure operation of the loads.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, G.; Yang, X.; Jiang, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, S.; Zhang, Y. Demand response regulation strategy for power grid accessed with high proportion of renewable energy considering industrial load characteristics. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Energy Review 2025; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, L.; Xiao, M. Short-term optimal operation of hydro-wind-solar hybrid system with improved generative adversarial networks. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Yan, X.; Tong, D.; Davis, S.J.; Caldeira, K.; Lin, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Ping, L.; et al. Strategies for climate-resilient global wind and solar power systems. Nature 2025, 643, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.; Wei, E.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q. A Multi-Type Dynamic Response Control Strategy for Energy Consumption. Energies 2024, 17, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huo, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yin, J.; Yang, J. Multi-Time-Scale Optimization and Control Method for High-Penetration Photovoltaic Electrolytic Aluminum Plants. Energies 2025, 18, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhu, H. Source-load coordinated optimal planning method of electrolytic aluminum industrial park. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2024, 44, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Hao, L.; Xu, F.; Min, Y. Industrial Load Peak Regulation and its Secondary Frequency Regulation Capacity Assessment Considering Intra-Production Segment Characteristics. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 3613–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bian, S.; Liao, S.; Lu, H. Source-Load Collaborative Optimization Method Considering Core Production Constraints of Electrolytic Aluminum Load. Energies 2024, 17, 6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Yan, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, S. Two-Level Optimal Scheduling of Electric–Aluminum–Carbon Energy System Considering Operational Safety of Electrolytic Aluminum Plants. Energies 2025, 18, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, D.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Y. Load Modeling of Electrolytic Aluminum Considering Distributed Impedance and Constant Current Control. J. North China Electr. Power Univ. 2023, 50, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Liao, S.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X. System static voltage stability analysis considering load characteristics of electrolytic aluminum. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Bian, S.; Xu, J.; Ke, D.; Sun, Z. Evaluation of Grid-load Interactive Adjustable Capacity of Electrolytic Aluminum Load Considering Optimization of Electrolytic Cell Energy Flow. Proc. CSEE 2025, 45, 2110–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liao, S.; Sun, Y.; Ma, X.; Gao, W.; Li, X.; Gu, J.; Dong, J.; Zhou, M. An isolated industrial power system driven by wind-coal power for aluminum productions: A case study of frequency control. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2015, 30, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Optimization scheduling strategy of high energy-consumption industrial park participation in green certificate trading and carbon emission trading. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 172, 111169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C. Coordinated optimization of IES in electrolytic aluminum industrial park considering hybrid CSP-CCHP system, demand response, and CCER-carbon trading. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 171, 110943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, C.M.; Spiller, M.; Dimovski, A.; Barbieri, J.; Ragaini, E.; Merlo, M. Integrated adequacy and stability BESS sizing criteria for hybrid diesel–PV microgrids in developing countries. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 83, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, H. Deep peak shaving method of electrolytic aluminum load cooperating with thermal power and energy storage system based on Wasserstein distance distribution robust. Therm. Power Gener. 2024, 53, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Si, D.; Li, F.; He, J.; Shan, W.; Niu, T. Research on peak shaving of wind power grid connection considering demand side response of electrolytic aluminum load. Adv. Technol. Electr. Eng. Energy 2023, 42, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Liao, S.; Fu, L.; Xu, J.; Ke, D.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; He, X. Hierarchical Optimization Strategy of High-penetration Wind Power System Considering Electrolytic Aluminum Energy-intensive Load Regulation and Deep Peak Shaving of Thermal Power. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 3186–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Liao, S. Source-load coordinated control strategy for smoothing wind power fluctuation in grid-connected high energy consuming electrolytic aluminum industrial power grid. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2022, 42, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Hua, D.; Song, X.; Liao, M.; Li, Z.; Jing, S. Multi-source coordinated low-carbon optimal dispatching for interconnected power systems considering carbon capture. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, S. A Coordinated Emergency Frequency Control Strategy Based on Output Regulation Approach for an Isolated Industrial Microgrid. Energies 2024, 17, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liao, S.; Sun, Y. Modeling and Control of Industrial Load for Power Grid Supporting; China Science Publishing & Media Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Thonstad, J. Aluminium Electrolysis: Fundamentals of the Hall-Héroult Process; Aluminium-Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J. Modern Aluminum Electrolysis; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hille, S.C.; Theewis, E.S. Explicit expressions and computational methods for the Fortet–Mourier distance of positive measures to finite weighted sums of Dirac measures. J. Approx. Theory 2023, 294, 105947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xe, J.; Liu, Y.; Gong, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, J. Series on Power Demand-Side Flexibility: Overview of Flexibility Potential in the Aluminum Electrolysis Industry; Rocky Mountain Institute: Basalt, CO, USA, 2023; Available online: https://rmi.org.cn/insights/industrial-dsf/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

| Electrolytic Cell Series | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated Power/MW | 100 | 180 | 240 | 240 | 300 |

| Series Current/kA | 180 | 240 | 300 | 300 | 330 |

| Equivalent Back EMF/V | 250 | 318 | 380 | 380 | 410 |

| Equivalent Resistance/mΩ | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| maximum voltage drops of the saturable reactor/V | 25 | 32 | 38 | 38 | 34 |

| Unit Capacity/MW | 350 | 150 |

|---|---|---|

| Active power output upper/lower limits/MW | 320/140 | 140/70 |

| Ramp-up/down constraints/MW | 50/80 | 50/80 |

| Minimum operating duration/h | 6 | 4 |

| Coal consumption coefficients a/(USD/(MW)2) | 0.00031 | 0.002 |

| Coal consumption coefficients b/(USD/MW) | 16.26 | 16.5 |

| Coal consumption coefficients c/(USD/MW) | 700 | 680 |

| Scenario | Period | USD/MWh |

|---|---|---|

| Peak | 11:00–14:00, 18:00–23:00 | 136 |

| Flat | 7:00–11:00, 14:00–18:00 | 85 |

| Valley | 0:00–7:00, 23:00–24:00 | 34 |

| Scenario | Thermal Power Operating Cost (10,000 USD) | Power Purchase Cost (10,000 USD) | Deviation Penalty Cost (10,000 USD) | Electrolytic Aluminum Regulation Cost (10,000 USD) | Wind Curtailment Cost (10,000 USD) | Total Cost (10,000 USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 160.32 | 4.38 | 1.09 | 0.00 | 1.77 | 167.56 |

| 2 | 160.03 | 2.13 | 0.67 | 1.75 | 1.06 | 165.63 |

| 3 | 159.85 | 1.73 | 0.30 | 1.87 | 0.84 | 164.59 |

| 4 | 159.85 | 1.14 | 0.20 | 2.02 | 0.45 | 163.66 |

| Power Purchase Cost (10,000 USD) | Deviation Penalty Cost (10,000 USD) | Electrolytic Aluminum Regulation Cost (10,000 USD) | Wind Curtailment Cost (10,000 USD) | Total Cost (10,000 USD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.14 | 0.2 | 2.02 | 0.45 | 163.66 |

| 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.77 | 2.74 | 1.61 | 167.77 |

| 0.4 | 6.74 | 1.62 | 3.24 | 3.73 | 175.18 |

| 0.6 | 11.94 | 3.21 | 3.89 | 7.12 | 186.01 |

| 0.8 | 23.27 | 5.74 | 4.57 | 14.69 | 208.12 |

| 1 | 37.16 | 9.65 | 5.46 | 25.54 | 237.66 |

| Temperature Range Constraints | Thermal Power Operating Cost (10,000 USD) | Power Purchase Cost (10,000 USD) | Deviation Penalty Cost (10,000 USD) | Electrolytic Aluminum Regulation Cost (10,000 USD) | Wind Curtailment Cost (10,000 USD) | Total Cost (10,000 USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 950–970 °C | 159.85 | 1.14 | 0.20 | 2.02 | 0.45 | 163.66 |

| 955–965 °C | 159.81 | 1.52 | 0.22 | 1.79 | 0.45 | 163.78 |

| 945–977 °C | 159.86 | 0.94 | 0.19 | 2.09 | 0.44 | 163.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, C.; Zhong, H.; Li, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Wang, Y. Multi-Time Scale Optimal Scheduling of Aluminum Electrolysis Parks Considering Production Economy and Operational Safety Under High Wind Power Integration. Energies 2026, 19, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010278

Xiao C, Zhong H, Li X, Ouyang Z, Wang Y. Multi-Time Scale Optimal Scheduling of Aluminum Electrolysis Parks Considering Production Economy and Operational Safety Under High Wind Power Integration. Energies. 2026; 19(1):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010278

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Chiyin, Hao Zhong, Xun Li, Zhenhui Ouyang, and Yongjia Wang. 2026. "Multi-Time Scale Optimal Scheduling of Aluminum Electrolysis Parks Considering Production Economy and Operational Safety Under High Wind Power Integration" Energies 19, no. 1: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010278

APA StyleXiao, C., Zhong, H., Li, X., Ouyang, Z., & Wang, Y. (2026). Multi-Time Scale Optimal Scheduling of Aluminum Electrolysis Parks Considering Production Economy and Operational Safety Under High Wind Power Integration. Energies, 19(1), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010278