1. Introduction

Driven by the dual impetus of the “dual carbon” goals and new energy vehicle industry policies, electric vehicles (EVs) have become the core carrier of a low-carbon transition in the transportation sector. The community scenario, which serves as the primary setting for residents’ daily parking and EV charging, has gradually become a key interface for the interaction between EVs and the power grid. With the continuous growth in the number of private EVs, the load characteristics of the power grid in community scenarios are undergoing significant changes: the randomness and concentration of EV charging loads (e.g., the overlap of charging demand with evening electricity peak hours) not only widen the peak-valley difference in community distribution network loads and increase transformer overload risks but also pose challenges to the safe and stable operation of the power grid and power supply reliability. Therefore, implementing ordered charging management for community EV users has increasingly become an urgent need to balance power grid loads and ensure the stable operation of the power system.

As the core means of ordered charging management for EVs, Demand Response (DR) has been the subject of extensive research by many scholars. For instance, based on the “avoidable cost” theory of ordered electricity consumption, some scholars have designed dual-dimensional (capacity-electricity) incentive prices by quantifying the reduced marginal generation costs and transmission capacity expansion costs of the power grid, which result from the reduction in users’ peak electricity load [

1]. Other studies have developed an interest distribution model between the power grid and users by integrating game theory, aiming to achieve balanced optimization of interests for both parties [

2]. Additionally, other studies have introduced non-monetary incentive measures, such as point redemption and charging discounts, to enrich the forms of incentives [

3]. To promote the implementation of demand response in residential communities, the National Development and Reform Commission, the National Energy Administration, and eight other ministries jointly issued the

Implementation Opinions on Further Enhancing the Service Guarantee Capability of Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure. The document stipulates that newly built residential communities must ensure that 100% of fixed parking spaces are equipped with charging facilities or reserved with installation conditions. In addition, it encourages charging operators or community management entities to be entrusted by property owners to centrally carry out the construction, operation, and maintenance of charging facilities.

Research on orderly charging mostly focuses on three aspects: mechanism design, regulation strategies, and user response.

In terms of mechanism design, current studies mostly focus on attracting users to engage in ordered charging by means of prices or incentives, with the goal of profit maximization or cost minimization. Ref. [

4] proposes a novel secure electricity trading and incentive contract model. Revenue-based incentive contracts can promote positive interactions among EVs, making EV owners more willing and active in participating in demand response or energy transactions. By applying contract theory, Ref. [

5] incorporates factors such as incentives, penalties, and electricity demand in demand response into the user utility function to design and optimize the demand response mechanism. This approach not only maximizes the profits of power grid operators but also ensures that users truthfully disclose their adjustment costs. Ref. [

6] proposes a long-term contract-based dispatching strategy that combines prices and incentives. Assuming that some EV users have signed long-term incentive agreements with EV aggregators, it optimizes with the objectives of maximizing the profits of EV aggregators and minimizing regional load fluctuations, verifying the effectiveness of the proposed dispatching strategy. Ref. [

7] proposes a market-based real-time mechanism where aggregators sign long-term contracts with the power grid and receive EV users’ charging information, power grid congestion, and other relevant data. They are responsible for dispatching EV users during demand response, ensuring both power quality and fulfillment of contract terms with the power grid. Case studies verify that this mechanism not only reduces electricity costs but also effectively addresses issues such as power grid congestion. Ref. [

8] proposes a model that combines incentive mechanisms with direct load control to define charging curves. Initially, aggregators provide users with a contract to agree on the dwell time and appropriately utilize the flexibility of EVs in successive steps. This model is solved using backward induction, which shows that this strategy creates a win–win situation for both aggregators and users. It can be observed that most studies on mechanism design focus on macro-level interest distribution to achieve a win–win outcome or are conducted based on public scenarios, while studies focused on community scenarios are relatively scarce.

In the existing literature, studies on optimal regulation strategies are relatively abundant, and the technical pathways are relatively mature. For example, Ref. [

9] proposes an EV charging load control model based on charging and swapping stations. With the goal of maximizing profits, it optimizes to obtain the optimal charging load curves for EV users and the scheduling strategy for adjustable capacity by aggregators. This enables charging and swapping stations to not only meet users’ charging and swapping needs but also provide adjustable capacity for the power grid. Based on the home energy management system, Ref. [

10] establishes a load model by considering the classification of various flexible electrical appliances, such as distributed photovoltaics, electric vehicles, and energy storage. It further constructs a day-ahead scheduling model for household users to participate in demand response by integrating price-based demand response and incentive-based demand response, finally verifying the effectiveness of the models. Ref. [

11] introduces a fully decentralized and participatory learning mechanism to develop a coordinated charging control mechanism for electric vehicles. And this mechanism reduces power peaks and energy costs while enhancing user comfort for EV owners. Ref. [

12] proposes a hierarchical scheduling model for electric vehicles that considers shared charging piles. The upper-level model determines the charging time, while the lower-level model coordinates charging stations and shared charging piles to determine the charging locations.

Some scholars have also begun to conduct research on electric vehicle users’ participation in demand response, exploring regulation strategies to achieve higher user acceptance. Ref. [

13] classifies user groups based on their response potential, sets priorities for different levels of user response potential, and inputs these priorities into the electric vehicle optimal scheduling model to obtain the optimal solution. Results show that this scheduling strategy effectively addresses the matching issue between EV users’ response potential and the optimal scheduling mode and helps users more readily accept scheduling tasks. Ref. [

14] proposes a charging priority calculation scheme based on users’ charging demands and electricity fees. This method can not only control the total charging power of electric vehicle users within the constraint range but also enable EV users to participate in demand response through measures such as temporarily reducing power during charging. Addressing the problem of difficult charging in old residential communities, Ref. [

15] proposes a hierarchical collaborative charging schedule based on registration and queuing, which optimizes the priority allocation under limited charging resources.

User satisfaction is an important part of ordered charging research, which directly affects the effectiveness of demand response. Thus, many scholars have conducted research on ordered charging based on user satisfaction. Ref. [

16] proposes a charging and discharging compensation pricing strategy for electric vehicle aggregators that considers users’ response willingness from the perspective of the Stackelberg game and establishes a user response willingness model to measure users’ participation level. Ref. [

17] establishes an EV user profit model, an aggregator profit model, and a user satisfaction model, and conducts a detailed analysis of the pricing factors that may cause changes in EV users’ satisfaction. Ref. [

18] proposes a two-stage ordered charging scheduling scheme for electric vehicles. In the first stage, it processes users’ preferences using intuitionistic fuzzy sets to reflect their willingness to adjust charging power; in the second stage, it incentivizes users to participate in demand response through a cooperative game model, thereby promoting EV participation in demand response while satisfying users’ preferences.

It can be observed that existing electric vehicle scheduling scenarios are mostly concentrated on public scenarios such as charging and swapping stations, while research on communities—as a core application scenario—is insufficient. Furthermore, research in aspects such as mechanism design, regulation strategies, and user satisfaction is relatively independent, and there is little research on integrating these three aspects and applying them to EV participation in demand response in communities. Under community scenarios, current research struggles to cover full-chain requirements, including mechanism design, regulation strategies, and user experience, and has not yet formed implementable systematic solutions.

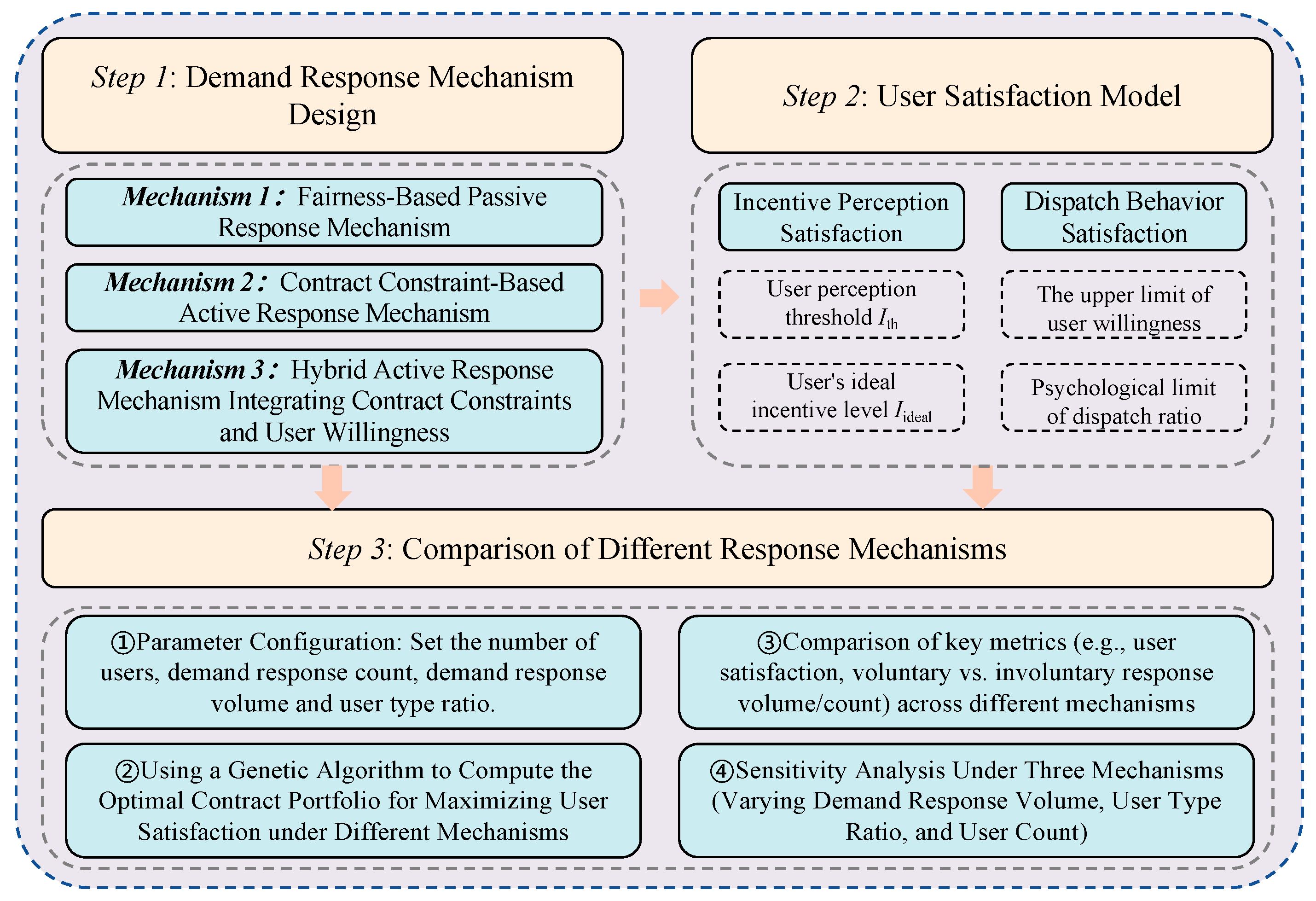

Therefore, this study focuses on the coordination between regulation order and user willingness in community EV demand response and proposes an orderly charging regulation strategy based on an optimal contract signing framework. The research is conducted under a centrally constructed and uniformly operated community charging scenario, in which private intelligent chargers are built, operated, and maintained by property management companies or professional operators. Users charge their EVs at fixed parking spaces using standardized charging facilities, resulting in relatively homogeneous charging access conditions. Under this assumption, external constraints commonly observed in public charging networks—such as facility distribution, accessibility, and congestion—are effectively mitigated, enabling the analysis to focus on heterogeneity in users’ subjective perception of incentives and regulation. Based on this framework, two active demand response mechanisms are designed and compared with a traditional fairness-based passive mechanism. A hierarchical user satisfaction model is constructed to characterize nonlinear user responses under different incentive and dispatch conditions, and a genetic algorithm is employed to optimize contract combinations from a system-level perspective. Through simulation analysis under a typical community scenario, the proposed mechanisms are evaluated in terms of user satisfaction, peak-shaving performance, and scalability, providing quantitative evidence for mechanism design and optimization of orderly EV charging in residential communities. The structural diagram of this study is shown in

Figure 1.

2. Mechanism Design

2.1. Mechanism 1: Fairness-Based Passive Response Mechanism

In existing residential demand response practices, power grids commonly adopt a passive response approach in which load reductions are allocated proportionally according to user capacity. Under this mechanism, all users bear identical load adjustment obligations during demand response events, and responsibility allocation is determined solely by user capacity. Specifically, each user’s required load reduction is proportional to their individual capacity, resulting in the same reduction ratio across all users. Although this mechanism ensures fairness in capacity-based allocation, it suffers from two key limitations. First, even in the idealized community environment considered in this study—where charging infrastructure conditions are relatively homogeneous—the mechanism neglects heterogeneity in users’ intrinsic willingness to respond. As a result, users with rigid charging demands may be forced to undertake regulation tasks beyond their acceptable range, leading to reduced user satisfaction. Second, the scheme lacks flexibility, as it does not incorporate prioritization and cannot be adaptively adjusted according to user-specific differences.

To address these limitations, this study proposes two active demand response mechanisms for community scenarios: a Contract Constraint-Based Active Response Mechanism and a Hybrid Active Response Mechanism that integrates contractual constraints with user willingness. These mechanisms enable a transition from passive, fairness-based allocation to proactive and flexible regulation. The overall framework is illustrated in

Figure 2.

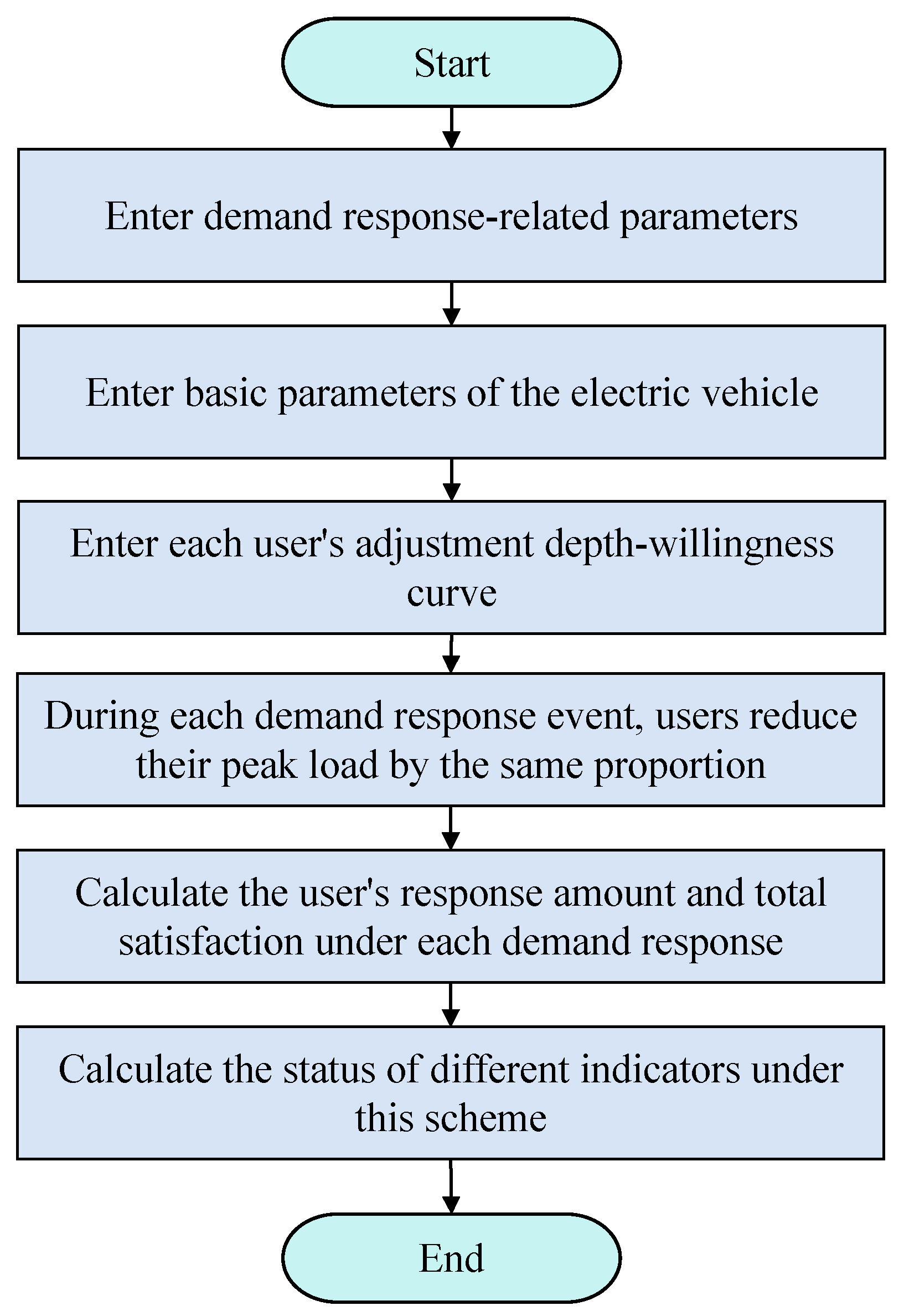

2.2. Mechanism 2: Contract Constraint-Based Active Response Mechanism

Although the Fairness-Based Passive Response Mechanism ensures fairness in the allocation of regulation responsibilities through proportional allocation, its core limitation lies in neglecting differences between users’ willingness to actively participate and the rigidity of their energy demands. As a result, users with inflexible charging needs may be required to undertake regulation tasks beyond their acceptable range, which significantly reduces satisfaction and weakens their long-term willingness to participate.

To address these limitations, this study proposes a Contract Constraint-Based Active Response Mechanism for electric vehicles. Through the core design of contract-based participation and priority scheduling, the mechanism enables users to make voluntary participation decisions while enforcing contractual obligations, thereby achieving an initial balance between system response reliability and user willingness.

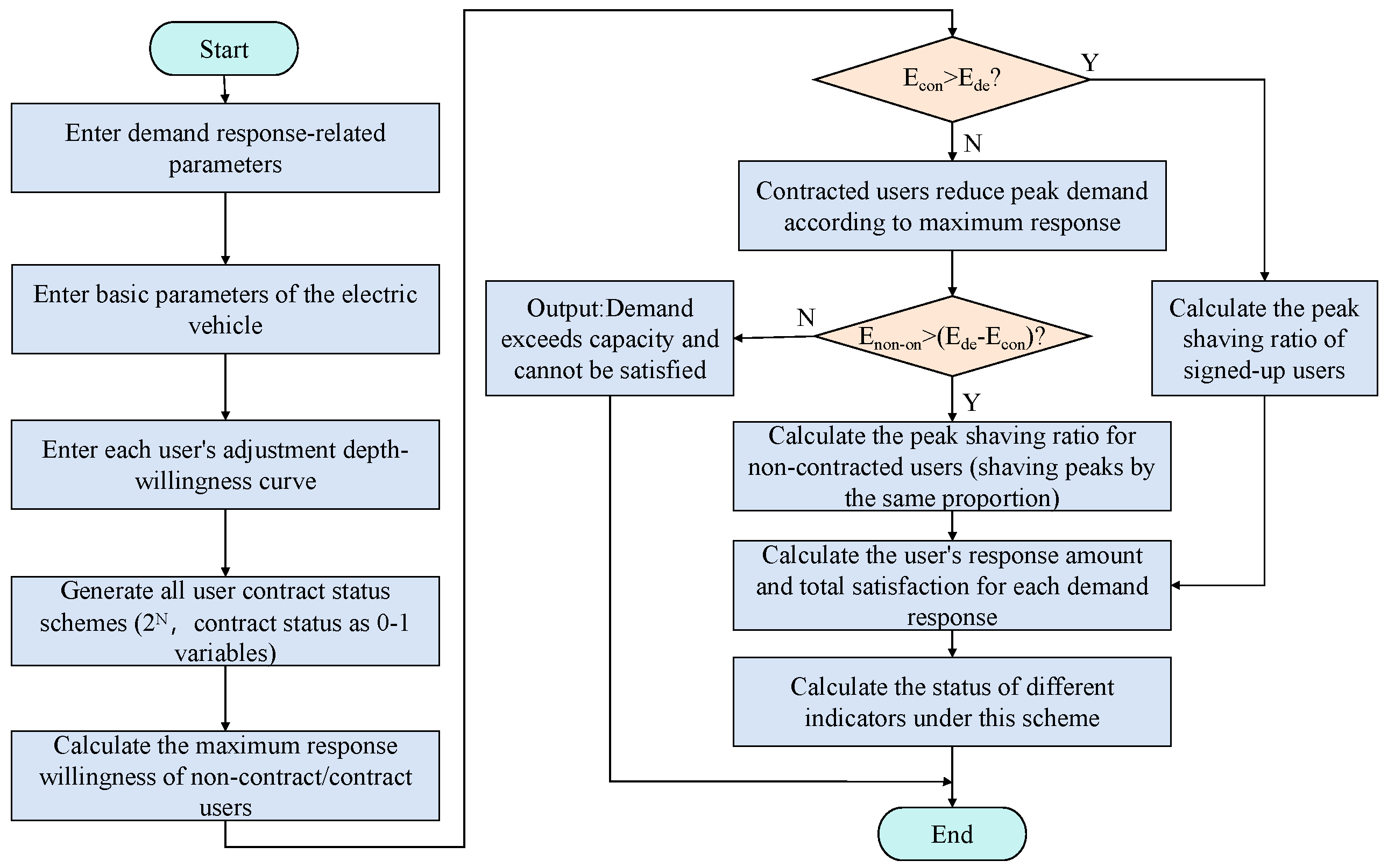

Its core logic is as follows: The power grid discloses relevant information on demand response for the year in advance, guides users willing to participate actively to sign contracts, and clarifies the priority response obligations that contracted users should fulfill during demand response for the year; when a demand response event occurs, it prioritizes the utilization of the reducible capacity of contracted users, and only when the capacity of contracted users is insufficient will non-contracted users share the remaining load in proportion. The flow of this mechanism is shown in

Figure 3.

- (1)

Based on historical demand response data, the power grid predicts the basic information of demand response for the current year, such as peak-shaving frequency M and peak-shaving volume , calculates the demand response incentive prices p that can be provided to users for the year, and discloses this information to users.

- (2)

Electric vehicle users decide whether to sign a contract with the power grid based on their own charging demands and the information disclosed by the power grid. If they decide to sign, the signed agreement will specify the priority response obligations and maximum responsive capacity of the contracted users .

- (3)

Statistics on the total responsive capacity of contracted users and non-contracted users are collected .

- (4)

Response of Contracted Users: If the total responsive capacity of contracted users is greater than the peak-shaving demand of the current demand response event, contracted users will undertake the demand response tasks in proportion to their capacities; if the total reducible capacity of contracted users is less than the peak-shaving demand of the current demand response event, contracted users will reduce load according to their maximum responsive capacity.

- (5)

Response of Non-Contracted Users: When the total reducible capacity of contracted users is less than the peak-shaving demand of the current demand response event, non-contracted users will undertake the remaining peak-shaving demand (after subtracting the total responsive capacity of contracted users) in proportion to their capacities.

2.3. Mechanism 3: Hybrid Active Response Mechanism Integrating Contract Constraints and User Willingness

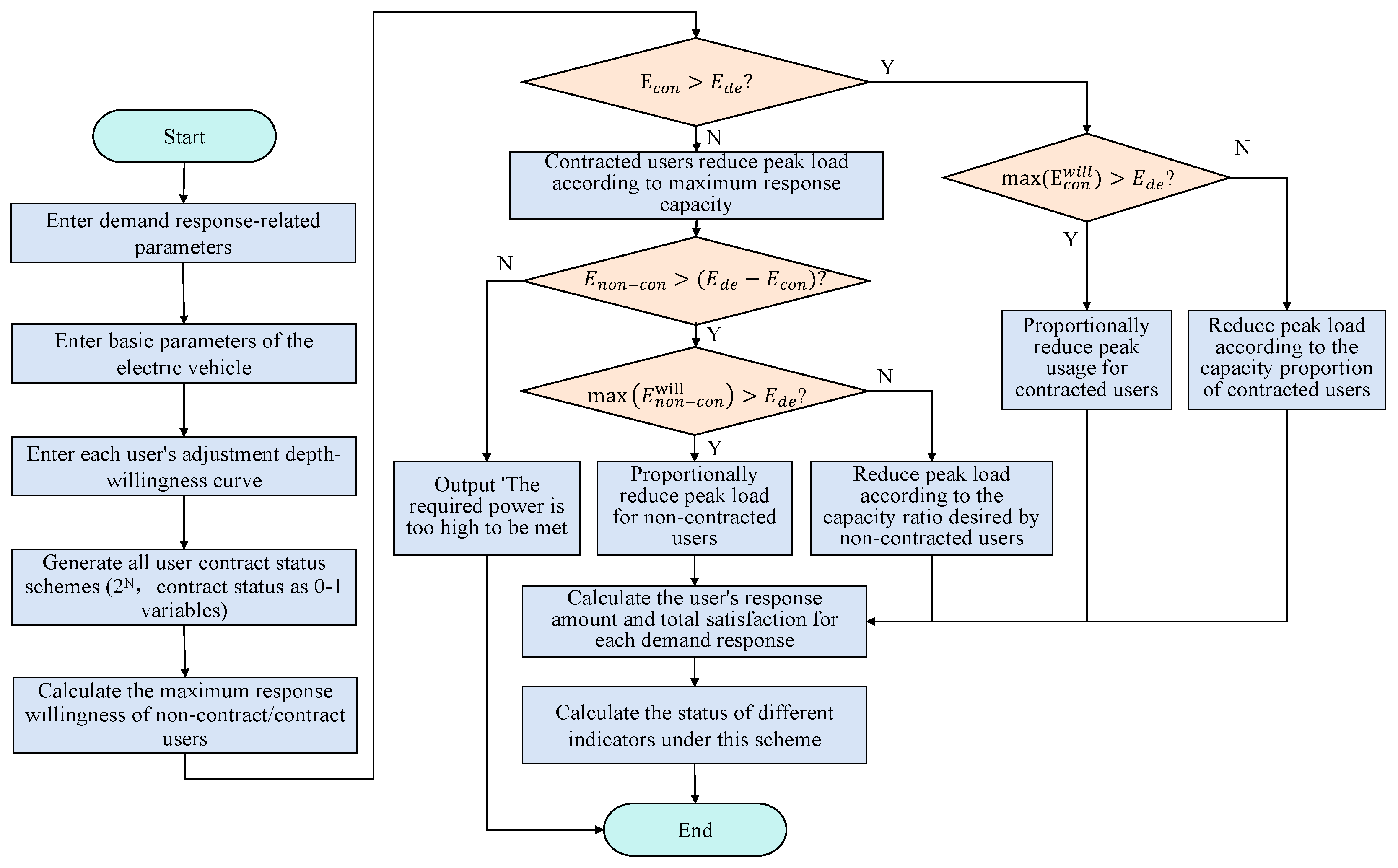

The traditional Contract Constraint-Based EV scheduling mechanism can ensure system response capability to a certain extent; however, its major limitation lies in disregarding heterogeneity in users’ willingness to participate. As a result, contracted users may experience substantial dissatisfaction when they are required to reduce load beyond their acceptable range, thereby undermining their long-term motivation to participate. To address this issue, this study proposes a Hybrid Active Response Mechanism that integrates contract constraints and user willingness. While preserving the contractual discipline and priority scheduling inherent in the original mechanism, the proposed approach introduces explicit willingness parameters, allowing users to declare their maximum willing reducible capacity according to their charging needs. This design enables the scheduling process to better balance system reliability and user satisfaction.

The operational logic of this mechanism is as follows. The grid first evaluates whether the aggregate responsive capacity of contracted users is sufficient to meet the current demand response requirement. If so, scheduling is performed within the contracted group, with tasks allocated in proportion to users’ declared willing capacity; if the willing capacity is insufficient, allocation proceeds according to their maximum responsive capacities. When the total capacity of contracted users cannot satisfy the requirement, non-contracted users are subsequently activated, and load reduction is first distributed within their willingness ranges. If the remaining demand still cannot be met, the mechanism sequentially utilizes the remaining capacities of contracted users and then non-contracted users beyond their declared willingness. The procedural framework of this mechanism is illustrated in

Figure 4.

- (1)

The grid forecasts the annual demand response baseline scenario, including parameters such as peak-shaving frequency M and peak-shaving volume , based on historical demand response data. It then calculates the incentive pricing p for the year and discloses this information to users.

- (2)

Electric vehicle users decide whether to enter into a contract with the grid based on the disclosed information and explicitly define in the agreement the priority response obligations of contracted users, maximum responsive capacity , and declared willing reduction capacity range (i.e., the maximum reduction amount the user is willing to undertake).

- (3)

Scheduling of Contracted Users: Assessment of Contracted Users’ Responsive Capacity.

The total responsive capacity of contracted users, , is evaluated. When this capacity exceeds the peak-shaving demand, the willing responsive capacity, , is subsequently assessed:

- a.

If the total willing reduction capacity of contracted users is greater than the peak-shaving demand, peak-shaving tasks are allocated in proportion to the willing capacity of contracted users;

- b.

If the total willing reduction capacity of contracted users is less than the peak-shaving demand, contracted users implement peak shaving in proportion to their capacities.

If the total responsive capacity of contracted users is less than the peak-shaving demand, contracted users respond at their maximum capacity, calculate the remaining peak-shaving demand, and proceed to Step (4).

- (4)

Scheduling of Non-Contracted Users: When contracted users fail to meet the demand, evaluate the willing responsive capacity of non-contracted users :

- a.

If the total willing reduction capacity of non-contracted users is greater than the remaining peak-shaving demand, non-contracted users implement a reduction in proportion to their willing capacity;

- b.

If the total willing reduction capacity of non-contracted users is less than the remaining peak-shaving demand, non-contracted users implement peak shaving in proportion.

3. User Satisfaction Model

In the context of community electric vehicle (EV) orderly charging and demand response, users’ overall satisfaction primarily originates from two dimensions. The first dimension is the psychological utility derived from external price incentives, reflecting users’ perceived benefits from economic compensation and participation mechanisms. The second dimension relates to users’ experience during the demand response execution stage, representing their perceptions of comfort and autonomy when charging behaviors are adjusted.

Furthermore, under the centrally constructed and uniformly operated community scenario with privately owned chargers considered in this study, users face no significant differences in external conditions such as charging convenience and infrastructure accessibility. Accordingly, the user categories defined in the model (active, intermediate, and passive), together with their associated behavioral parameters (e.g., response willingness thresholds and psychological cost coefficients), are mainly intended to capture behavioral heterogeneity arising from intrinsic factors, including daily routines, vehicle usage patterns, and subjective preferences. On this basis, overall user satisfaction is formulated as a weighted combination of incentive perception satisfaction and dispatch behavior satisfaction:

where

denotes the incentive perception satisfaction, describing the influence of price incentives on users’ subjective willingness;

represents the dispatch behavior satisfaction, measuring the deviation between the actual charging power and the user’s ideal behavior; and

and

are the corresponding weighting coefficients, used to distinguish the preference tendencies of different user types.

In residential private charging scenarios, users exhibit behavioral differences in demand response primarily in their sensitivity to charging timing, flexibility, and the degree of control intervention they can tolerate. Accordingly, this study categorizes users into three types—active, intermediate, and passive—and assigns differentiated behavioral parameters, including response willingness, psychological cost, and satisfaction weights. This classification approach allows differences in users’ convenience preferences, time urgency, and acceptance of control interventions to be naturally reflected in both satisfaction evaluation and response behavior, without explicitly modeling spatial accessibility or physical distance. As a result, the model provides a more realistic representation of user behavior characteristics in community scenarios.

3.1. Incentive Perception Satisfaction

During the demand response process, electric vehicle (EV) users exhibit significant heterogeneity in daily routines, travel patterns, and consumption psychology, which leads to uncertainty in their perception and acceptance of incentive signals. In the context of community-based vehicle-to-grid (V2G) interaction, power utilities or aggregators design incentive mechanisms to encourage users to voluntarily participate in demand response or to sign contracts and become controllable load resources. Users may choose between two charging modes: (1) a collaborative charging mode, in which users participate in demand response and allow the system to optimize their charging schedules in exchange for economic compensation; and (2) an independent charging mode, in which users charge solely according to their own needs without participating in system coordination.

In this study, user satisfaction with incentives is modeled using a piecewise linear function, which approximates users’ psychological responses under different incentive levels [

19]. This formulation quantitatively characterizes the variation in users’ perceived response intensity as incentives change, thereby providing theoretical support for subsequent evaluation of user satisfaction and analysis of contract signing willingness. The EV response willingness is expressed in terms of perceived response quantity, and its piecewise representation is given as follows:

where

denotes the incentive perception satisfaction,

represents the unit compensation incentive,

is the user perception threshold,

is the user’s ideal incentive level, and

is the psychological cost coefficient, representing the unit price incentive corresponding to the energy amount a user is willing to shift.

and

denote the energy quantities corresponding to the high-price and low-price periods, respectively. Accordingly, when the compensation incentive

exceeds the ideal level

, the user’s incentive perception satisfaction

approaches its upper limit. The corresponding satisfaction curve is illustrated in

Figure 5.

Within the incentive level interval [, ], the user’s incentive perception satisfaction exhibits a linear relationship with the incentive level, with a slope ranging between and , reflecting the heterogeneity in sensitivity to incentive changes among users of the same category. The satisfaction curve can be divided into four distinct phases: dead zone, linear response zone, ideal saturation zone, and complete saturation zone.

Specifically, denotes the threshold at which users begin to perceive the incentive. When the incentive level is below , users are insensitive to changes in incentives, and their satisfaction remains at zero—this is defined as the dead zone. When the incentive level enters the interval [], users start to respond linearly, with satisfaction increasing proportionally to the incentive level—this is the linear response zone. The point represents the minimum incentive level at which the earliest users in this group reach maximum satisfaction. As the incentive level continues to rise within the interval [], some users have reached full satisfaction while others are still increasing, causing the curve to gradually flatten—this phase is defined as the ideal saturation zone. Finally, represents the maximum incentive level at which all users in this group achieve maximum satisfaction. Beyond , users’ satisfaction remains constant at its upper limit, entering the complete saturation zone, where further changes in incentives produce negligible effects.

The threshold and slope parameters of this incentive–response relationship characterize the critical willingness of EV users to respond to incentives, forming the foundation of the user satisfaction function. A detailed parameter analysis is provided in

Appendix A.

3.2. Dispatch Behavior Satisfaction

In demand response scenarios, electric vehicle (EV) users’ satisfaction with charging and discharging dispatch behavior is influenced not only by the level of economic incentives but also by the deviation between the actual dispatch amount and the user’s acceptable tolerance. When dispatch requests exceed a user’s psychological threshold, overall satisfaction may decline significantly, even in the presence of financial compensation or incentives. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a satisfaction function that captures the acceptance of dispatch behavior across different user types and describes their psychological response patterns under varying dispatch ratios.

According to Miller’s research on human–computer interaction psychology, when a system’s response time or task delay exceeds a user’s acceptable threshold, perceived satisfaction exhibits a pronounced stagewise decline, reflecting nonlinear discontinuities in user perception [

20]. Inspired by this psychological mechanism, this study divides EV users’ dispatch behavior satisfaction into multiple stages to characterize the piecewise degradation of satisfaction as the dispatch ratio expands from the acceptable range into the overload region.

Accordingly, the dispatch behavior satisfaction function,

is defined as follows:

where

denotes the decline coefficient within the willingness range, reflecting the gradual decrease in satisfaction as the dispatch ratio increases within the user’s acceptable range;

represents the upper limit of user willingness; and

denotes the psychological limit of dispatch ratio, corresponding to the maximum dispatch extent that the user can tolerate. The corresponding satisfaction curve of this relationship is illustrated in

Figure 6.

Let x ∈ [0, 1] denote the actual dispatch ratio of a user during a demand response event, and let W ∈ (0, 1] represent the maximum acceptable willingness ratio. When x ≤ W, the dispatch remains within the user’s willingness range, and satisfaction decreases slowly as the dispatch ratio increases, indicating a relatively high level of user acceptance toward system control. However, when the dispatch ratio exceeds the willingness limit W, the user gradually enters a psychological resistance zone, where satisfaction declines rapidly until reaching the psychological threshold. Once x > np, the user’s subjective satisfaction drops to zero, signifying complete refusal of further dispatch.

5. Case Study

5.1. Simulation Scenario Settings

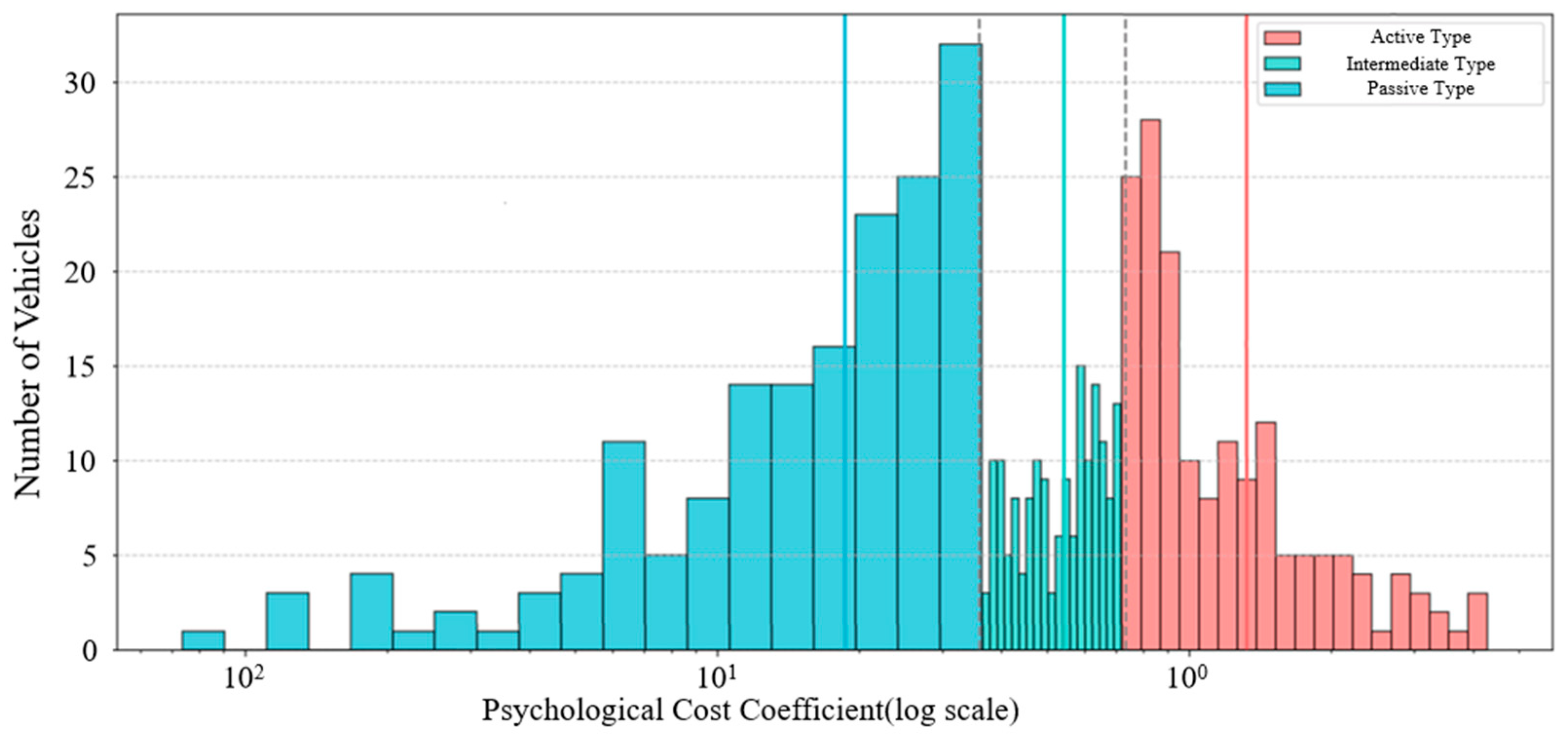

This study focuses on a typical urban residential community, primarily examining scenarios in which residents charge their electric vehicles using privately owned chargers installed at designated parking spaces. In such settings, the availability and convenience of charging facilities are relatively stable, and external constraints commonly encountered at public charging stations—such as queuing or differences in travel distance—are largely absent. Consequently, users exhibit relatively homogeneous accessibility to charging infrastructure, and variations in their participation in demand response programs mainly stem from individual differences in sensitivity to economic incentives, behavioral impacts, and psychological costs.

Based on this context, the community is assumed to contain N = 80 electric vehicles capable of participating in demand response. Taking residential DC chargers as an example, each user is assumed to be equipped with a private charger with a rated power of 20 kW. Given that each demand response event lasts for 1 h, the theoretical maximum response energy provided by a single vehicle per event is 20 kWh. Additional modeling parameters and baseline data are provided in

Appendix C. According to differences in response willingness, users are classified into active, intermediate, and passive types, with an equal proportion of 1:1:1.

In terms of modeling willingness level, the maximum response willingness β+ of active-type users follows a normal distribution with a mean of μ+ = 50%, i.e., β+~N(μ+,σ2); the maximum response willingness β of intermediate-type users follows a normal distribution with a mean of μ = 30%, i.e., β~N(μ,σ2); the maximum response willingness β− of passive-type users follows a normal distribution with a mean of μ− = 10%, i.e., β−~N(μ−,σ2).

A total of M = 10 demand response events are assumed, with corresponding total DR capacities denoted as {

D1,

D2, …,

DM}, as listed in

Appendix C. To account for users’ varying psychological sensitivity to economic incentives and behavioral constraints, the satisfaction weight coefficients

for active, intermediate, and passive users are set as [0.8, 0.2], [0.5, 0.5], and [0.2, 0.8], respectively.

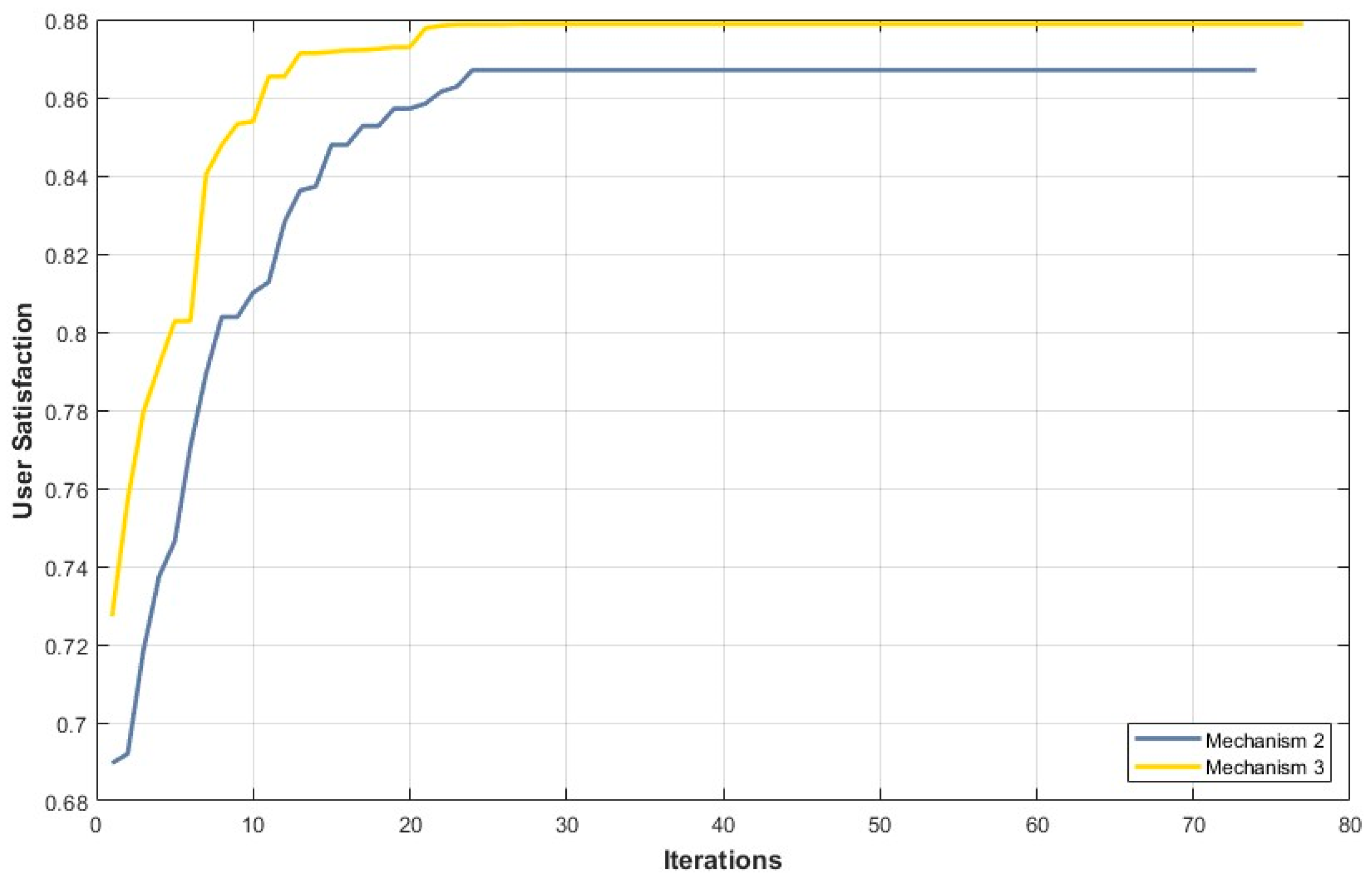

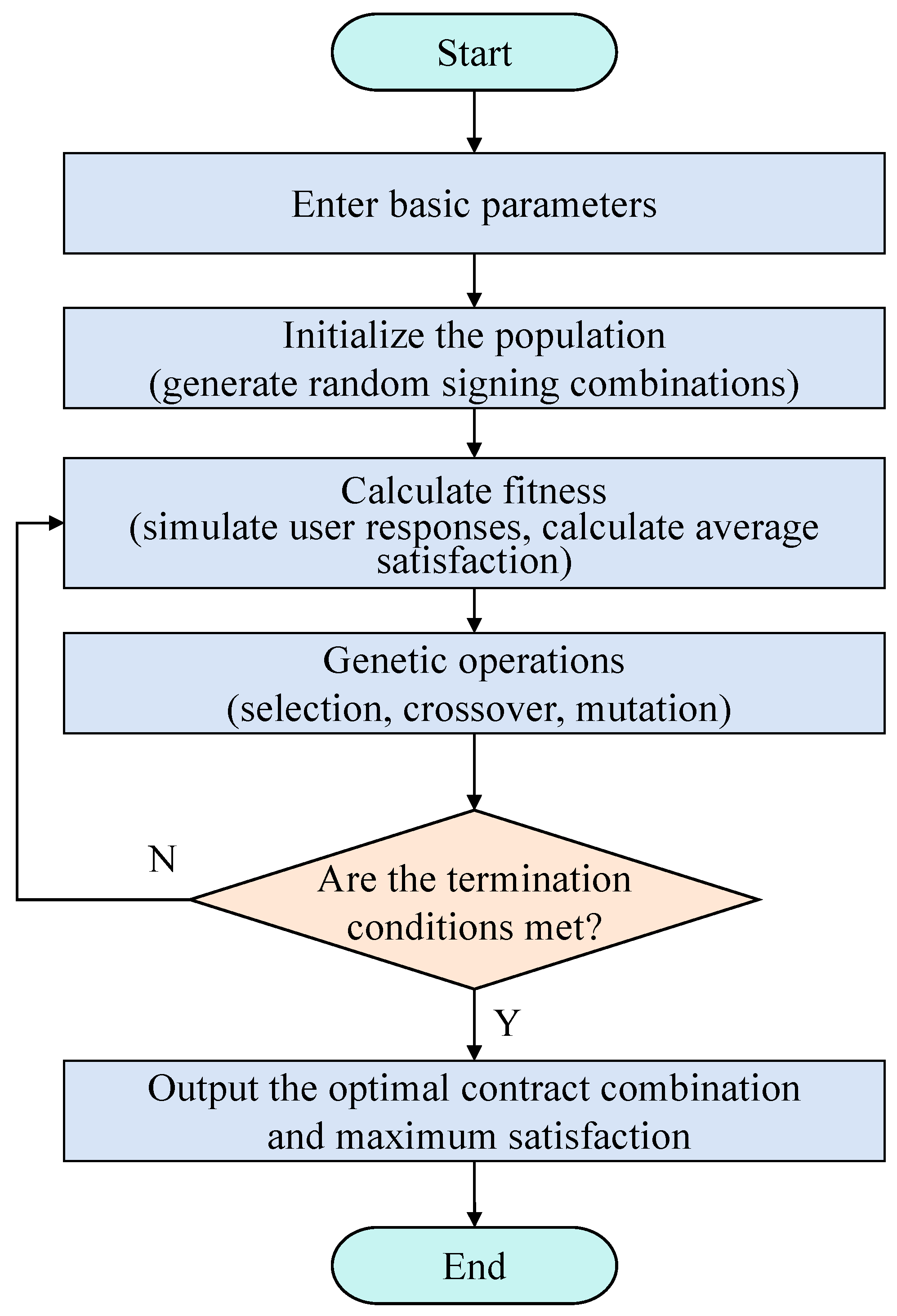

In the contract configuration optimization, this study represents the contract status of N = 80 community EV users using a binary vector of length N, denoted as . Here, indicates that user i has signed an active response contract with the grid, whereas indicates that the user remains unsigned. The genetic algorithm performs a global search over the solution space , where each chromosome corresponds to a candidate contract combination. For a given , the model simulates the response decisions and benefit settlement process of the three user types over M demand response events, obtaining each user’s incentive perception satisfaction and dispatch behavior satisfaction for every event. These are then combined through weighted aggregation to compute the overall satisfaction for user i in event t.

The genetic algorithm aims to maximize , seeking an optimal contract configuration that balances peak-shaving capability and user satisfaction. To solve the above optimization problem, this study implements the GA using the MATLAB R2022b Global Optimization Toolbox. A binary encoding scheme is adopted to represent chromosomes, and standard genetic operators suitable for binary coding—tournament selection, single-point crossover, and bit-wise mutation—are employed. The initial population is generated randomly and evolves across iterations based on fitness-driven selection. The population size is set to 100, with a maximum of 100 generations; the crossover probability is set to 0.8, and the mutation probability to 0.15. To improve computational efficiency, the algorithm terminates early if the improvement in the best fitness value remains below 0.05% for 50 consecutive generations.

With regard to constraints, once a contract configuration is specified, the consistency between users’ maximum response capability and the system’s peak-shaving requirement is enforced as a hard constraint. If the total available response capacity under a given contract portfolio is insufficient to meet the required peak-shaving volume for a specific event, the model executes the maximum feasible response, and any unmet portion is reflected in the fitness function through reduced satisfaction. Consequently, infeasible configurations or those with insufficient peak-shaving capability are naturally eliminated during the evolutionary process. In addition, the applicability and convergence performance of the genetic algorithm are validated and illustrated in

Appendix B.

5.2. Comparison of Different Response Mechanisms

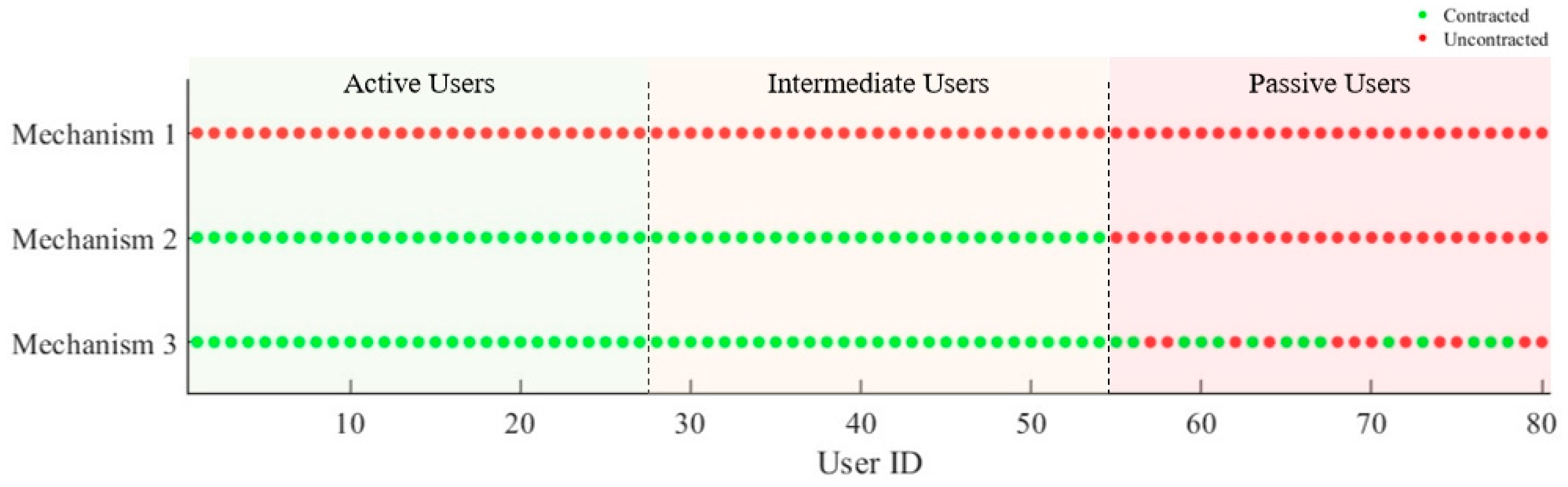

This study designs and compares three demand response (DR) mechanisms under identical total DR requirements. Comparative analyses are conducted across multiple dimensions, including average user satisfaction, voluntary and involuntary response volumes, the frequency of voluntary and involuntary DR events, and benefit distribution between contracted and non-contracted users. These evaluations aim to systematically assess the performance and applicability of each mechanism in terms of user acceptance and fairness in benefit allocation. The contract configurations corresponding to the maximum average user satisfaction under each mechanism are illustrated in

Figure 8.

As shown in the figure, Mechanism 1 serves as the baseline case, in which all users remain uncontracted. Under Mechanism 2, contracted users are primarily concentrated among active and intermediate user groups. Because this mechanism requires contracted users to fulfill relatively rigid response obligations during DR events—where callable capacity is directly allocated by the system according to predefined contract ratios—users with higher psychological costs or stronger resistance to peak-shaving tasks (i.e., passive users) face a higher perceived participation risk. This results in negative expected utility and, consequently, refusal to sign contracts. These results indicate that although a purely contract-constrained mechanism can effectively secure callable capacity for the grid, it has limited ability to attract users with low psychological tolerance for sustained, long-term participation.

In contrast, Mechanism 3 exhibits a noticeably broader distribution of contracted users, with a portion of passive users also choosing to participate. The key reason lies in the introduction of the willingness-based reduction capacity parameter, which transforms the contractual relationship from a rigid constraint into a flexible one. This design allows users to determine their maximum reducible capacity within an acceptable psychological threshold. When system dispatch remains within a user’s declared willingness range, satisfaction remains high, thereby alleviating psychological resistance and significantly increasing the overall contract participation rate.

5.2.1. User Satisfaction

A comparison of average user satisfaction under the three mechanisms is presented in

Figure 9. Among them, Mechanism 3 achieves the highest average user satisfaction, reaching 0.8788, which is significantly higher than that of Mechanism 2 and Mechanism 1. The superior performance of Mechanism 3 can be attributed to its integrated consideration of contractual constraints and individual user heterogeneity. Specifically, the dispatchable capacity of contracted users is first utilized within their declared willingness range, which preserves contractual discipline while ensuring the effectiveness of incentive mechanisms. When the contracted capacity is insufficient, the willingness-based capacity of non-contracted users is employed as a supplementary resource, further enhancing system scheduling flexibility. Moreover, by hierarchically dispatching capacity beyond users’ willingness ranges only when necessary, Mechanism 3 maintains the balance between system supply and demand while minimizing the loss of user satisfaction.

In contrast, Mechanism 1 adopts a proportional peak-shaving strategy among all users, failing to account for heterogeneity in user willingness and the absence of contractual constraints. Although this mechanism exhibits a certain degree of fairness in allocation, its neglect of individual behavioral differences results in a relatively low overall satisfaction level. Mechanism 2 introduces contract-based priority in the allocation process and achieves a higher average satisfaction than Mechanism 1; however, it does not explicitly consider user willingness. Consequently, when some users are required to reduce load beyond their acceptable range, their satisfaction declines markedly, limiting the potential for further improvement. Overall, the results demonstrate that incorporating user willingness into a contract-constrained demand response mechanism can effectively enhance overall user satisfaction while maintaining system reliability.

5.2.2. Comparison of Voluntary Response Volume and Involuntary Response Volume

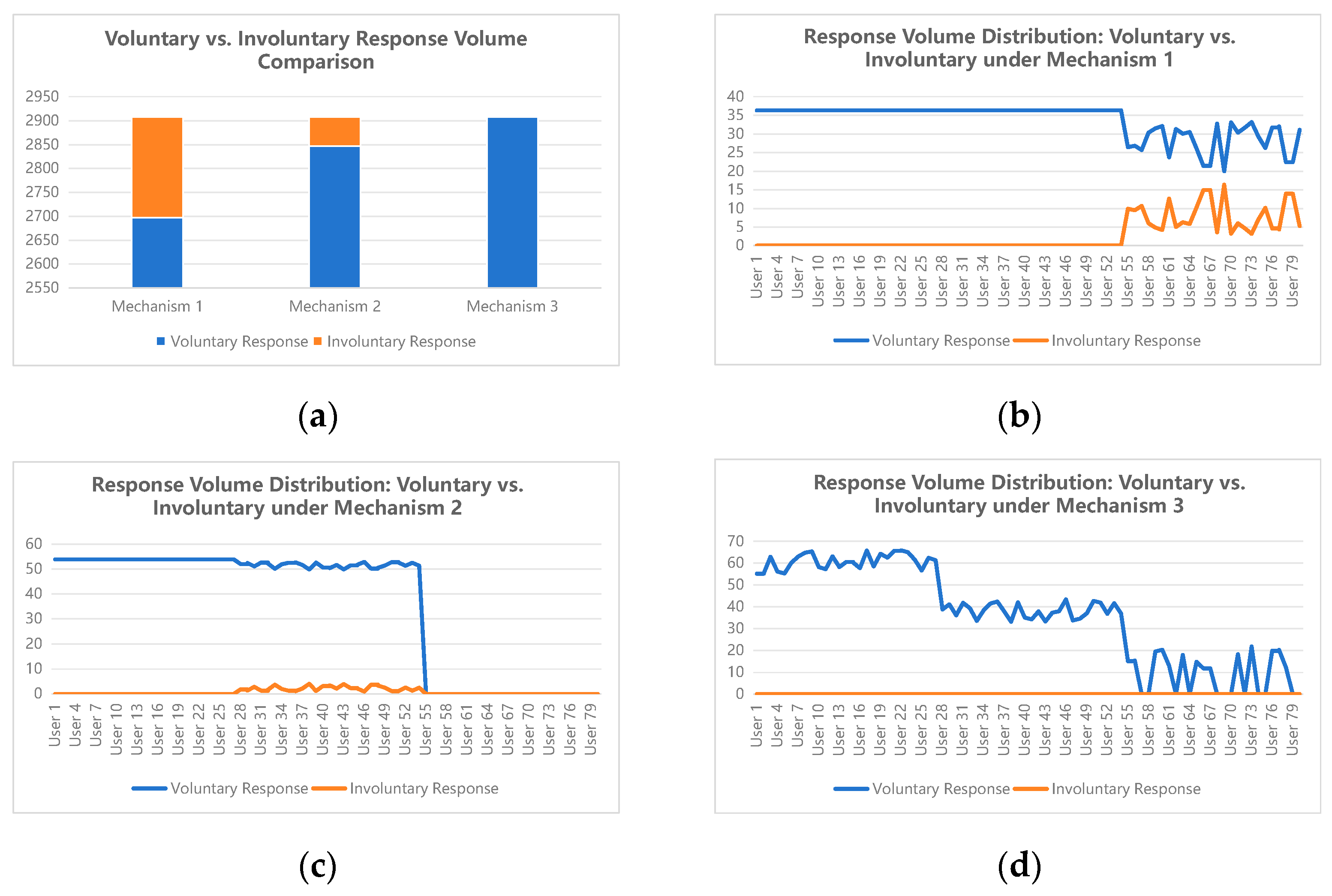

The distribution of voluntary and involuntary response volumes under the three mechanisms is illustrated in

Figure 10. The results indicate that Mechanism 3 performs best in enhancing both user satisfaction and system scheduling flexibility, exhibiting the highest proportion of voluntary response volume and an almost complete elimination of involuntary response. In contrast, both Mechanism 1 and Mechanism 2 retain a non-negligible proportion of involuntary response, which negatively affects overall user satisfaction. From an aggregate perspective, the voluntary response volume under Mechanism 3 is sufficient to fully satisfy demand response requirements, whereas Mechanism 1 and Mechanism 2 must rely on a certain level of involuntary response to meet system needs. At the individual user level, both Mechanism 1 and Mechanism 2 involve situations in which some users are required to respond beyond their declared willingness ranges. By contrast, owing to its hierarchical dispatching strategy, Mechanism 3 is able, in most cases, to meet demand response requirements using only capacity within users’ willingness ranges, thereby significantly reducing the occurrence of involuntary dispatch. The advantage of Mechanism 3 lies in its explicit integration of user willingness on top of contractual constraints, enabling the system to minimize involuntary dispatch while maintaining the balance between supply and demand. As a result, it achieves a dual optimization of users’ willingness to participate and overall system reliability. Although Mechanism 1 and Mechanism 2 exhibit a certain degree of scheduling feasibility, neither fully accounts for individual user heterogeneity, leading to an inherent trade-off between user satisfaction and fairness.

5.2.3. Comparison of Voluntary Response Times and Involuntary Response Times

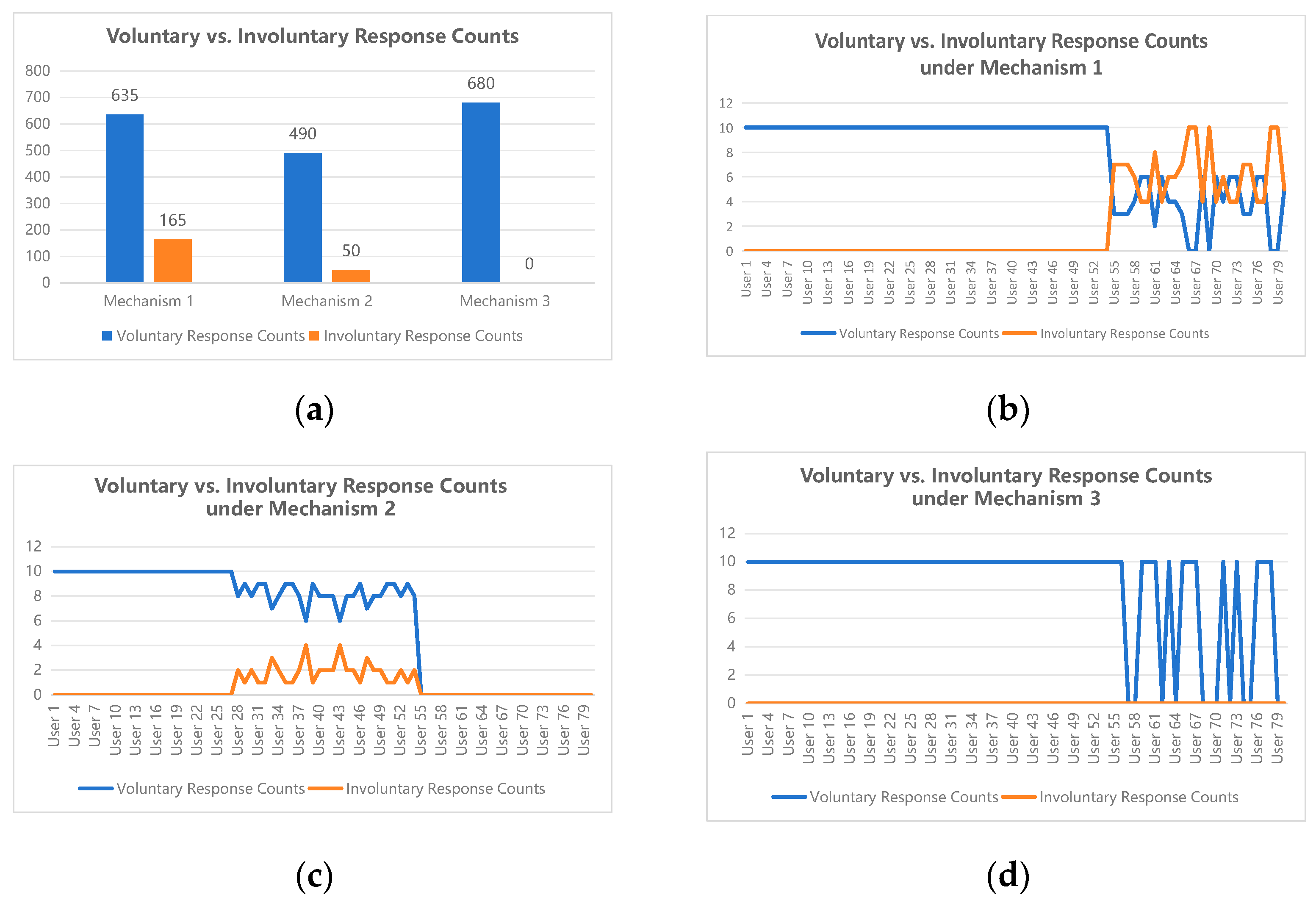

A comparison of users’ voluntary and involuntary response frequencies under the three mechanisms is presented in

Figure 11. Overall, Mechanism 3 exhibits the best performance, with the highest number of voluntary responses and the complete elimination of involuntary responses, whereas both Mechanism 1 and Mechanism 2 exhibit involuntary responses to varying degrees. Specifically, Mechanism 1 records approximately 635 voluntary responses and about 165 involuntary responses, while Mechanism 2 exhibits 490 voluntary responses and 50 involuntary responses. In contrast, Mechanism 3 achieves 680 voluntary responses with zero involuntary responses, indicating that this mechanism maximizes the utilization of users’ voluntary response capacity while effectively avoiding forced dispatch.

Further individual-level analysis reveals distinct response patterns across mechanisms. Under Mechanism 1, most users experience involuntary responses to some extent, reflecting the limitation of the fairness-based allocation scheme in failing to adequately account for user willingness. Although Mechanism 2 increases the voluntary response frequency for a subset of users through priority allocation to contracted users, a considerable number of users are still subject to involuntary dispatch. By contrast, Mechanism 3 achieves an allocation outcome that relies almost entirely on voluntary responses, with involuntary response frequencies reduced to zero for all users. This response pattern aligns more closely with users’ declared willingness, demonstrating superior acceptability and perceived fairness.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the robustness and long-term effectiveness of the three demand response strategies, this section conducts a sensitivity analysis along three dimensions: demand response volume, user group composition, and system scale. By examining the sensitivity of average user satisfaction to these key parameters, this analysis aims to identify the intrinsic performance characteristics and applicable boundaries of the different mechanisms.

5.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis Under Different Demand Response Volumes

To assess the performance of the three demand response (DR) mechanisms under varying dispatch pressures, this subsection analyzes the sensitivity of average user satisfaction to changes in total DR volume.

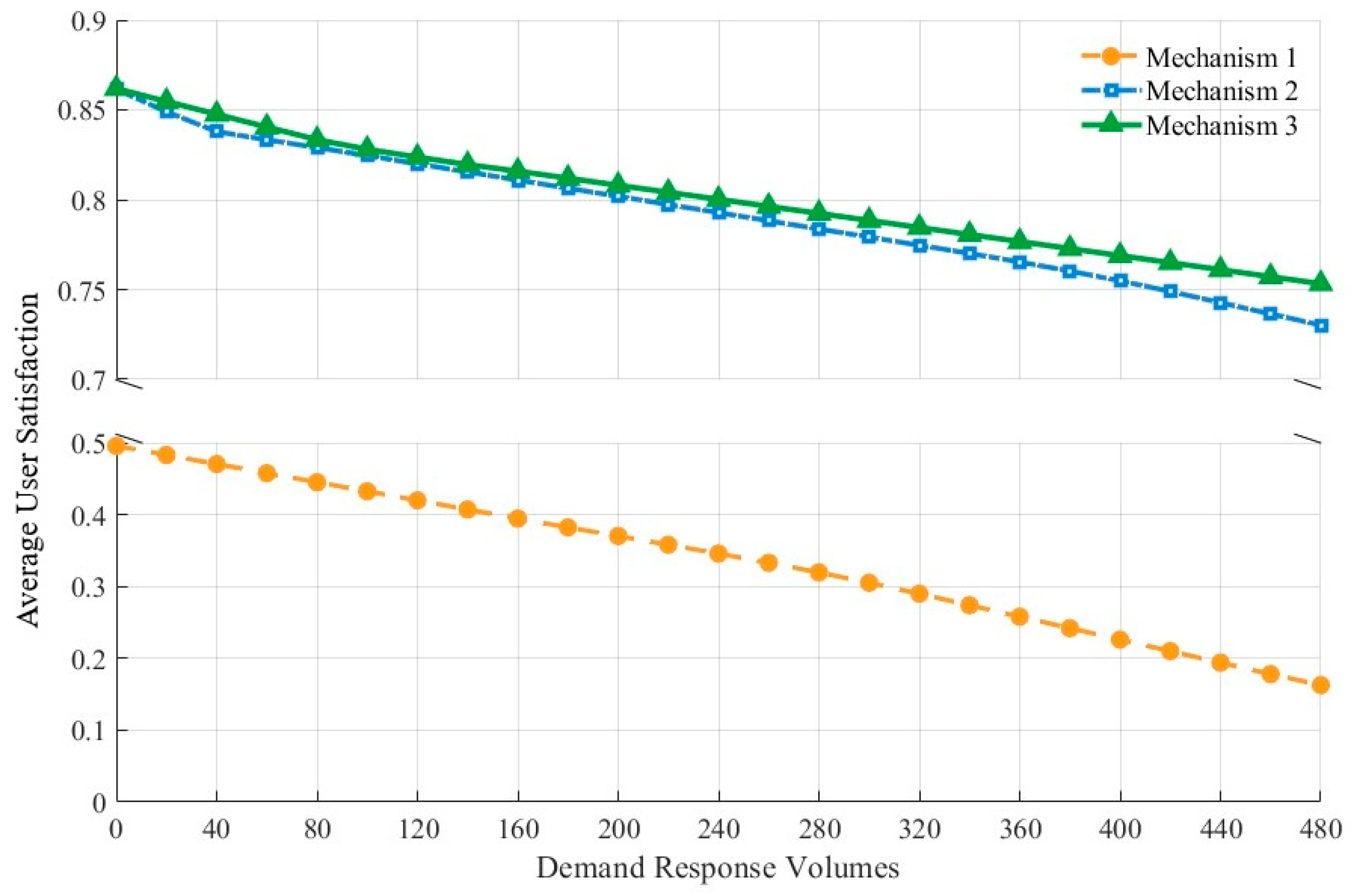

Figure 12 illustrates the response curves of system-wide average user satisfaction for the three mechanisms as the total DR volume varies within the range of [0, 480].

The simulation results reveal distinct sensitivity characteristics across the three mechanisms. Mechanism 1 exhibits a clear negative correlation between average user satisfaction and total DR volume, showing a continuous and monotonic decline as dispatch requirements increase. This trend indicates that Mechanism 1 struggles to accommodate higher scheduling demands, as any additional load reduction directly translates into a loss of user utility, highlighting the mechanism’s inherent vulnerability.

By contrast, the two active response mechanisms—Mechanism 2 and Mechanism 3—demonstrate significantly greater robustness. Across the entire tested range, both mechanisms maintain relatively high and stable levels of average user satisfaction, exhibiting low sensitivity to variations in total DR volume. This behavior suggests that the introduction of contract-based active participation effectively transforms dispatch requests from a perceived compulsory burden into an opportunity for economic compensation, thereby substantially improving user acceptance of load adjustments.

Moreover, throughout the entire observation interval, the satisfaction curve of Mechanism 3 consistently remains above that of Mechanism 2, confirming that explicitly incorporating individual user willingness on top of active participation generates additional satisfaction gains. By respecting users’ psychological tolerance while ensuring dispatch effectiveness, Mechanism 3 achieves a more favorable balance between grid regulation requirements and user comfort.

In summary, the sensitivity analysis demonstrates that Mechanism 3 not only effectively incentivizes user participation but also exhibits strong adaptability to changes in demand response scale, highlighting its potential as a sustainable and scalable community-level load management strategy.

5.3.2. Sensitivity Analysis Under Different Proportions of Active-Type Users

To investigate the impact of user composition on the performance of different demand response (DR) mechanisms, this subsection conducts a sensitivity analysis focusing on the proportion of active-type users, which represents a key influencing parameter.

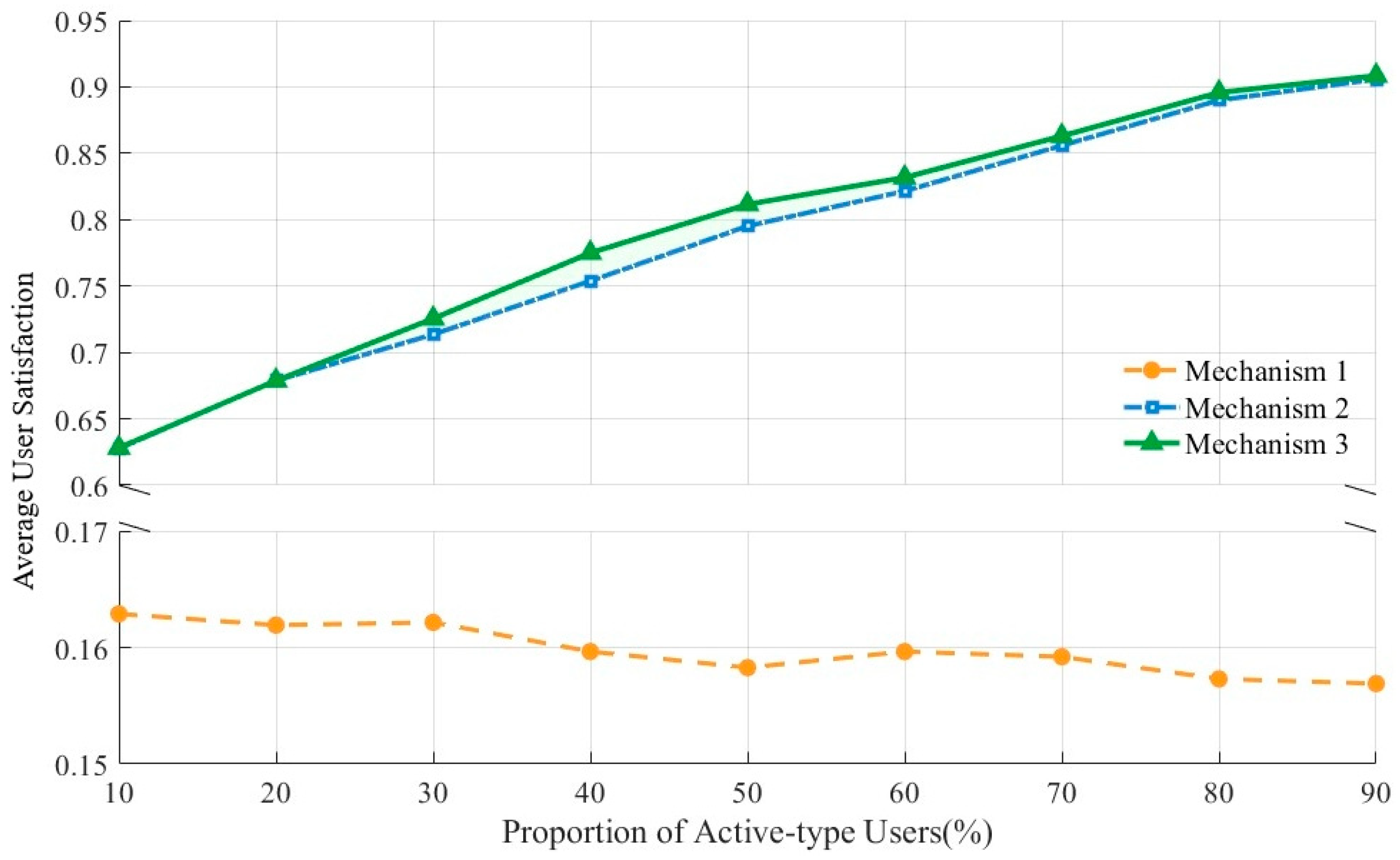

Figure 13 illustrates the response of system-wide average user satisfaction across the three mechanisms as the proportion of active users increases from 10% to 90%.

The results indicate that changes in user composition exert markedly different effects on the three mechanisms. Mechanism 3 exhibits strong adaptability and stability, with average user satisfaction increasing steadily from 0.628 to 0.908, corresponding to a 44.59% improvement. This monotonic upward trend suggests that Mechanism 3 effectively exploits the performance advantages associated with a higher share of active users. Through its embedded willingness coordination design, users with high response willingness are transformed into reliable sources of system flexibility and regulation capability.

Mechanism 2 also shows a positive response trend; however, its satisfaction level remains consistently lower than that of Mechanism 3 across the entire parameter range. This persistent gap highlights the additional marginal benefits of explicitly incorporating user willingness on top of a purely contract-based framework, underscoring the importance of refined mechanism design.

By contrast, Mechanism 1 exhibits performance that is essentially independent of user composition, with average satisfaction remaining nearly constant at approximately 0.20. This outcome reflects the structural limitations of the fairness-based allocation mechanism: its mandatory scheduling approach neglects user heterogeneity and therefore fails to leverage potential performance gains arising from a more favorable user mix. Such insensitivity to user composition fundamentally indicates a lack of adaptability to market-oriented demand response environments.

An effective high-performance DR mechanism should be capable of adapting to variations in user group characteristics. The performance of Mechanism 3 demonstrates that integrating user classification and willingness information into mechanism design not only enhances overall system performance but also preserves control effectiveness under evolving user structures. These findings provide valuable insights for future power system operations with a high penetration of variable renewable energy sources.

5.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis Under Different User Scales

As illustrated in

Figure 14, a sensitivity analysis is conducted to evaluate the scalability and adaptability of the proposed demand response (DR) mechanisms under varying system scales. The number of participating electric vehicles (EVs) is gradually increased from 10 to 150, and the resulting variation in system-wide average user satisfaction across the three mechanisms is systematically examined.

The simulation results show that Mechanism 1 consistently maintains a low satisfaction level below 0.35, accompanied by irregular fluctuations as the user scale increases. This behavior further confirms the structural limitations of its fixed-ratio allocation strategy, under which changes in system scale directly translate into unstable user experiences. By contrast, both active response mechanisms—Mechanism 2 and Mechanism 3—exhibit strong scalability and robustness, with satisfaction levels stabilizing within a relatively high range of 0.75–0.80 across different user population sizes. This indicates that, as the system scales up, active mechanisms can effectively balance economic incentives and user comfort, thereby maintaining stable user acceptance.

Moreover, Mechanism 3 consistently outperforms Mechanism 2 throughout the entire observation range. This sustained advantage highlights the critical role of willingness coordination in large-scale systems, where closer alignment between users’ psychological expectations and system dispatch requirements enables further improvements in overall satisfaction and response enthusiasm without increasing incentive costs.

From a scalability perspective, these results demonstrate that active response mechanisms possess strong potential for large-scale commercial deployment. The absence of performance degradation as the user scale expands provides solid mechanism-level support for the promotion of community-level demand response projects across a wide range of user population sizes.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates the design of multiple mechanisms for community EV participation in DR. Three differentiated user regulation mechanisms are systematically developed and comparatively evaluated within a unified framework, focusing on user satisfaction, response behavior, and system performance. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows.

- (1)

Mechanism performance comparison: Mechanism 1 ensures fairness through proportional allocation but lacks effective user incentives and contractual constraints, resulting in a low average satisfaction level of 0.2595 and a high proportion of involuntary responses. The contract-based active mechanism improves system controllability by imposing rigid contractual obligations; however, it does not fully account for heterogeneity in individual willingness, which limits overall satisfaction. In contrast, the hybrid active response mechanism integrates user willingness parameters into the contractual framework, achieving simultaneous improvements in regulatory flexibility and psychological acceptance. This mechanism attains the highest average satisfaction and the lowest involuntary response ratio, demonstrating superior overall performance.

- (2)

User behavioral characteristics: Under the optimal contract configuration, contracted users are primarily concentrated among active and partially intermediate user groups, while most passive users are excluded, indicating a clear self-selection effect. This outcome reflects the mechanism’s ability to attract users with high reliability and strong willingness to participate, thereby reducing psychological costs and resistance associated with forced dispatch.

- (3)

Sensitivity analysis results: As the total DR requirement increases, the average satisfaction of the active response mechanisms remains relatively stable, whereas that of the passive mechanism declines sharply. When the proportion of active users increases, the satisfaction level of the hybrid mechanism rises steadily from 0.628 to 0.908. Moreover, when the user population expands to 150 EVs, the hybrid mechanism maintains a high satisfaction level in the range of 0.75–0.80, indicating strong scalability and robustness.

- (4)

Engineering and practical implications: The results suggest that the optimization of DR mechanisms should shift from traditional “equitable load allocation” toward a “willingness-driven and differentiated incentive design” paradigm. By integrating willingness modeling with contract-based coordination, system security can be ensured while enhancing long-term user participation. This provides a solid technical foundation for orderly community EV charging management and demand-side management in next-generation power systems.

This study provides quantitative evidence and theoretical support for the design and optimization of demand response mechanisms; however, several directions remain worthy of further investigation. The proposed framework is primarily developed for community charging scenarios characterized by relatively homogeneous infrastructure conditions and controllable operation. This setting facilitates focused analysis of the interaction between contractual arrangements and user psychological behavior while minimizing the influence of external system variables. In more complex application environments—such as areas with constrained charging resources or heterogeneous spatial layouts (e.g., older residential communities or public charging stations)—external conditions may further affect users’ response capability and participation willingness.

Accordingly, future research may be extended in several directions. First, more refined quantitative models of user preferences could be developed to capture how different user groups trade-off among electricity prices, subsidies, and charging comfort. Second, multidimensional benefit allocation and incentive compensation mechanisms could be designed to enhance the persistence and stability of long-term participation among heterogeneous users. Third, by integrating diversified market mechanisms such as carbon markets and ancillary service markets, the economic and environmental value of demand response in new-type power systems could be further expanded. Fourth, heterogeneity in external charging infrastructure conditions—such as the distribution, accessibility, and potential congestion of public chargers—can be explicitly incorporated [

21] to systematically analyze how user response capability and behavioral patterns vary across different spatial environments, thereby improving the applicability and robustness of demand response mechanisms.

Moreover, when the research scope is extended to public charging hubs or city-wide systems, the peak-shaving effects induced by demand response may, in turn, influence charging infrastructure siting and expansion decisions. Developing an integrated modeling framework that jointly considers demand response mechanisms and charging station planning therefore represents an important direction for future research. Through these extensions, coordinated improvements in power system security, economic efficiency, and user satisfaction can be achieved, promoting deeper integration of vehicle–grid interaction and the ongoing energy transition.