Optimization Models for Distributed Energy Systems Under CO2 Constraints: Sizing, Operating, and Regulating Power Provision

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related Work

1.3. Research Objectives

2. Methods

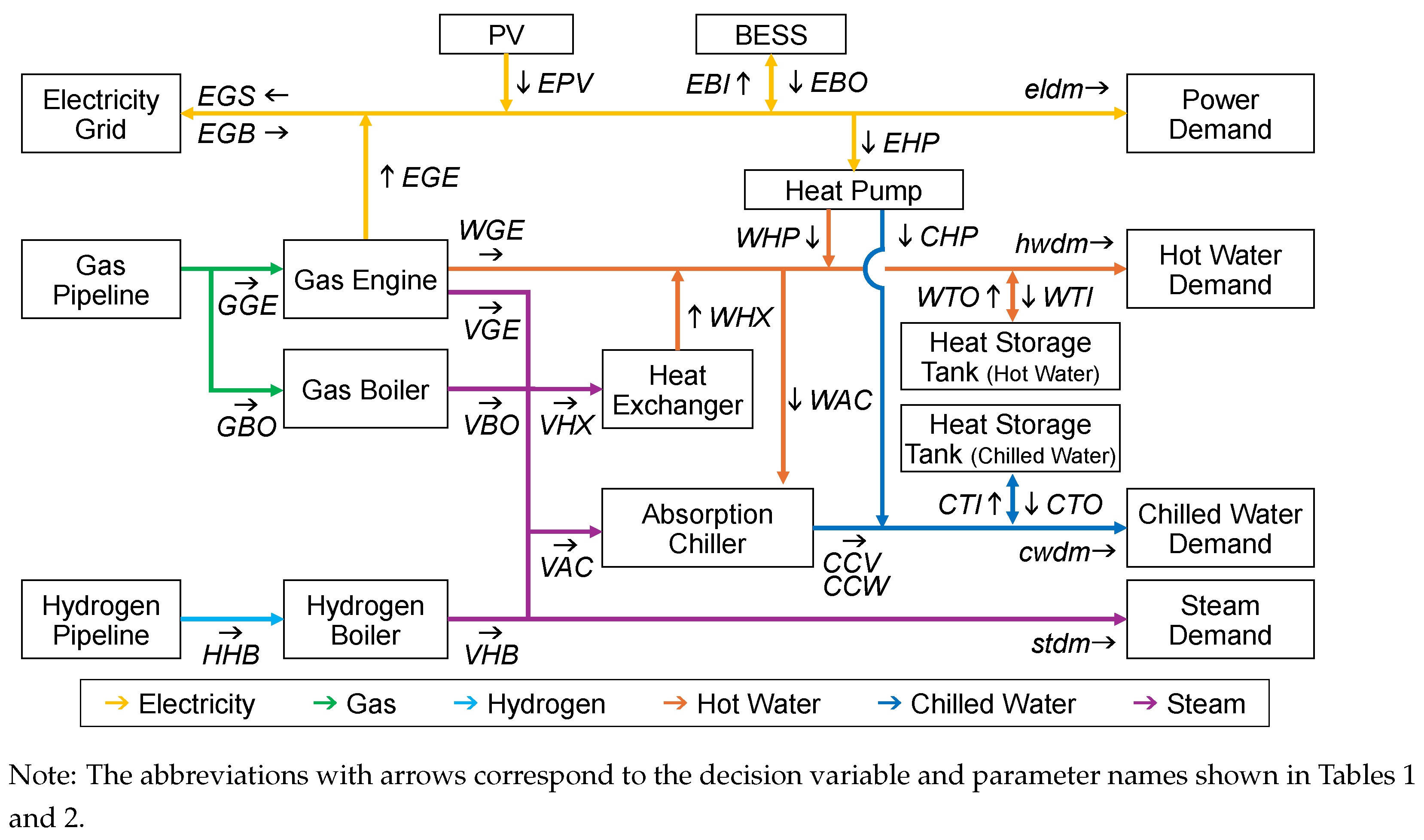

2.1. System Energy Flow and Notation

2.2. DES Optimization Model

- (1)

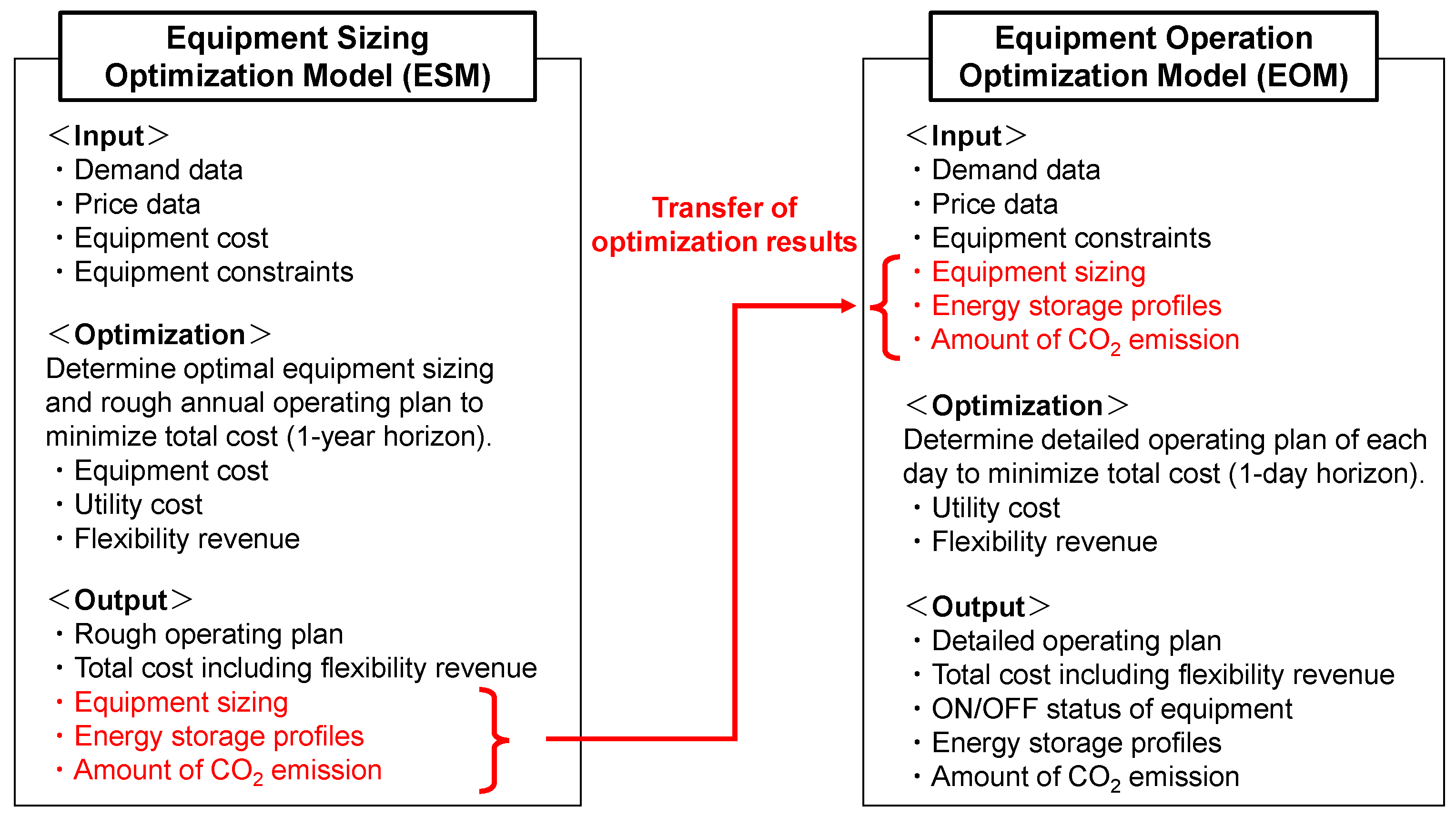

- Equipment Sizing Optimization Model (ESM)The ESM uses input data such as DES demand (electricity, steam, hot water, and chilled water), equipment installation costs, electricity tariffs, and gas prices. Its objective function minimizes the total cost over one year, comprising both installation and operational costs, while accounting for depreciation. The model outputs include the number of equipment units, hourly operational profiles (including energy storage levels), CO2 emissions, and the total operating cost.

- (2)

- Equipment Operation Optimization Model (EOM)The EOM uses both the input and output data from ESM—specifically, the number of units, energy storage profiles, and the daily allowable CO2 emission level. Its objective is to minimize daily operating costs. Since stored energy is assumed to be fully discharged at the end of each optimization period, the storage capacity calculated in the ESM is used to represent continuity across days. In particular, the model incorporates constraints requiring that the storage level at the beginning of day N equals that at the end of day , and that the end-of-day storage level is no less than the corresponding value specified in the ESM.For equipment such as gas engine and absorption chiller with non-continuous minimum output constraints, the model explicitly accounts for start-up and shut-down states to enable more accurate operational scheduling. Regarding CO2 emissions, the daily emission values obtained from the ESM are imposed as upper limits in the EOM, ensuring that emissions do not exceed the results determined in the sizing stage. However, because the EOM incorporates more detailed operational scheduling—such as gas engine startup fuel consumption—the resulting emissions may differ from those in the ESM. To address this discrepancy, a penalty term is introduced to ensure that the daily CO2 emissions in the EOM do not exceed the upper limits derived from the ESM.Similar to the ESM, the EOM also incorporates constraints related to regulating power provision. Its outputs include hourly equipment status, energy storage levels, start-up/shut-down events, CO2 emissions, and the total operating cost.

2.3. Case Study

- The first case study examined the impact of enabling or disabling regulating power provision on equipment configuration and profitability.

- The second case study used a DES without a PV, a BESS and a hydrogen boiler as the baseline, with the baseline conditions set for fiscal year 2025, and examined changes in equipment configuration, operations, and profitability when CO2 emissions were reduced by a specified percentage.

3. Scenario Assumptions and Input Data

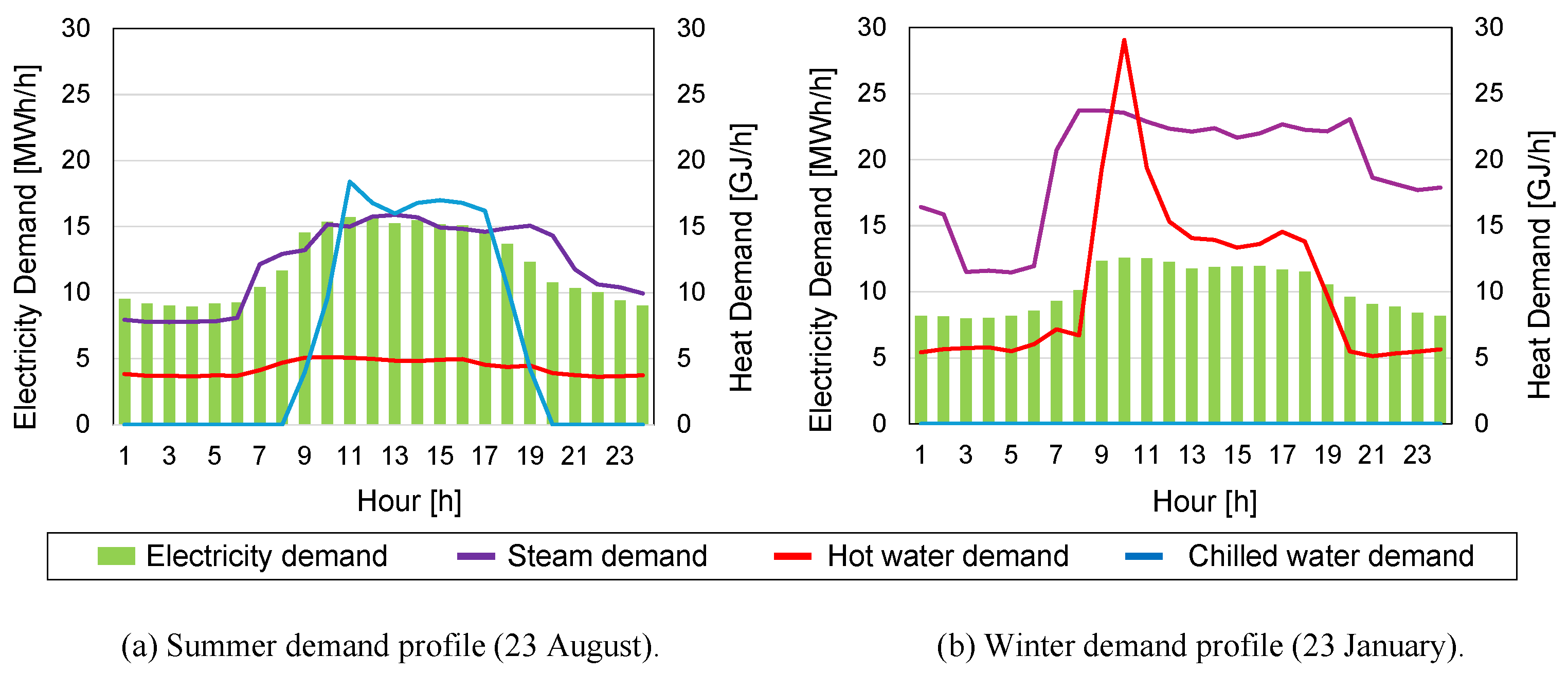

3.1. Demand Data

3.2. PV Output Data

3.3. Price Data

3.4. Equipment Specification

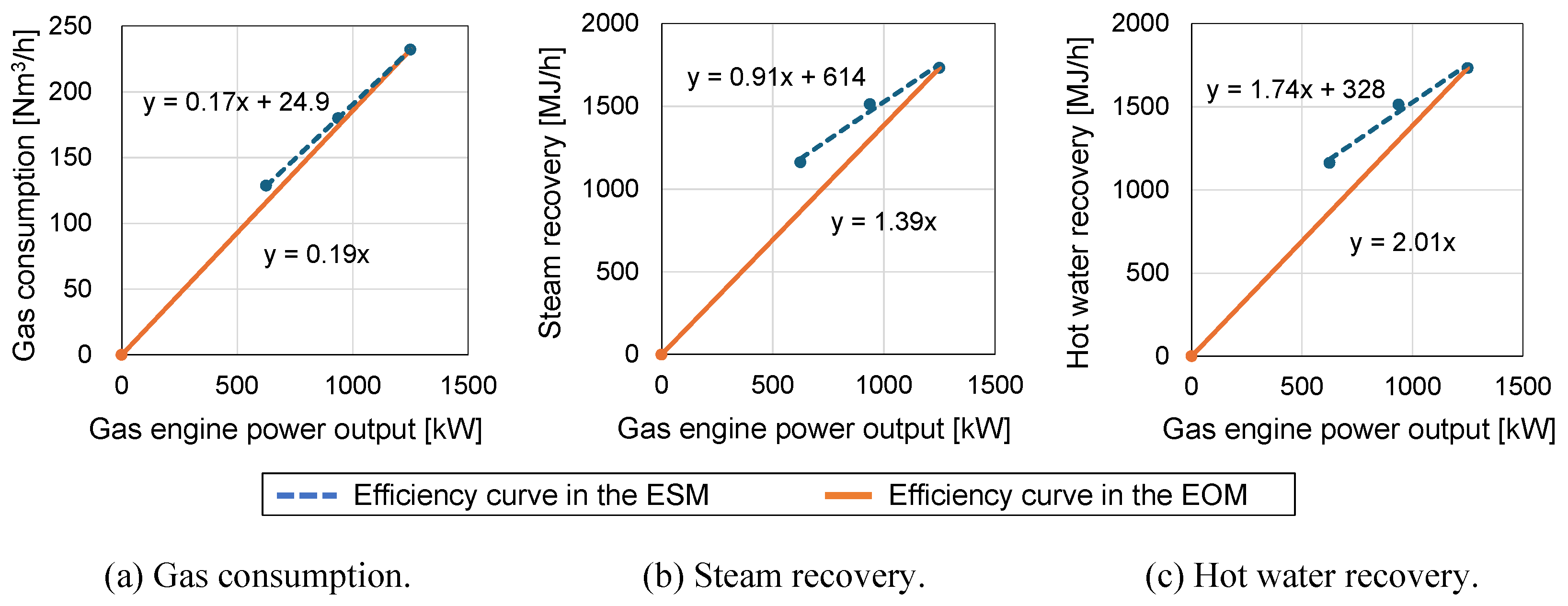

3.4.1. Gas Engine

3.4.2. Gas Boiler

3.4.3. Absorption Chiller

3.4.4. Heat Pump

3.4.5. Heat Exchanger

3.4.6. Thermal Storage Tank

3.4.7. PV Generation Unit

3.4.8. Battery Storage Systems

3.4.9. Hydrogen Boiler

3.5. Equipment Installation Cost

3.6. CO2 Emission Factor

4. Equipment Sizing Optimization Model (ESM)

4.1. Capital Costs

4.2. Objective Function of the ESM

4.3. Supply–Demand Balance Constraints of the ESM

4.4. Equipment Constraints of the ESM

4.4.1. Gas Engine Constraints

4.4.2. BESS Constraints

4.4.3. Gas Boiler Constraints

4.4.4. Absorption Chiller Constraints

4.4.5. Heat Pump Constraints

4.4.6. Heat Exchanger Constraints

4.4.7. Thermal Storage Tank Constraints

4.4.8. PV Generation Constraints

4.4.9. Hydrogen Boiler Constraints

4.5. CO2 Emissions Constraints of the ESM

5. Equipment Operation Optimization Model (EOM)

5.1. Objective Function of the EOM

5.2. Supply–Demand Balance Constraints of the EOM

5.3. Equipment Constraints of the EOM

5.3.1. Gas Engine Constraints

5.3.2. BESS Constraints

5.3.3. Absorption Chiller Constraints

5.3.4. Thermal Storage Tank Constraints

5.4. CO2 Emissions Constraints of the EOM

6. Analysis Results

6.1. Baseline Case

6.2. Impact of Regulating Power Provision

6.2.1. Comparison of Installed Equipment Capacity

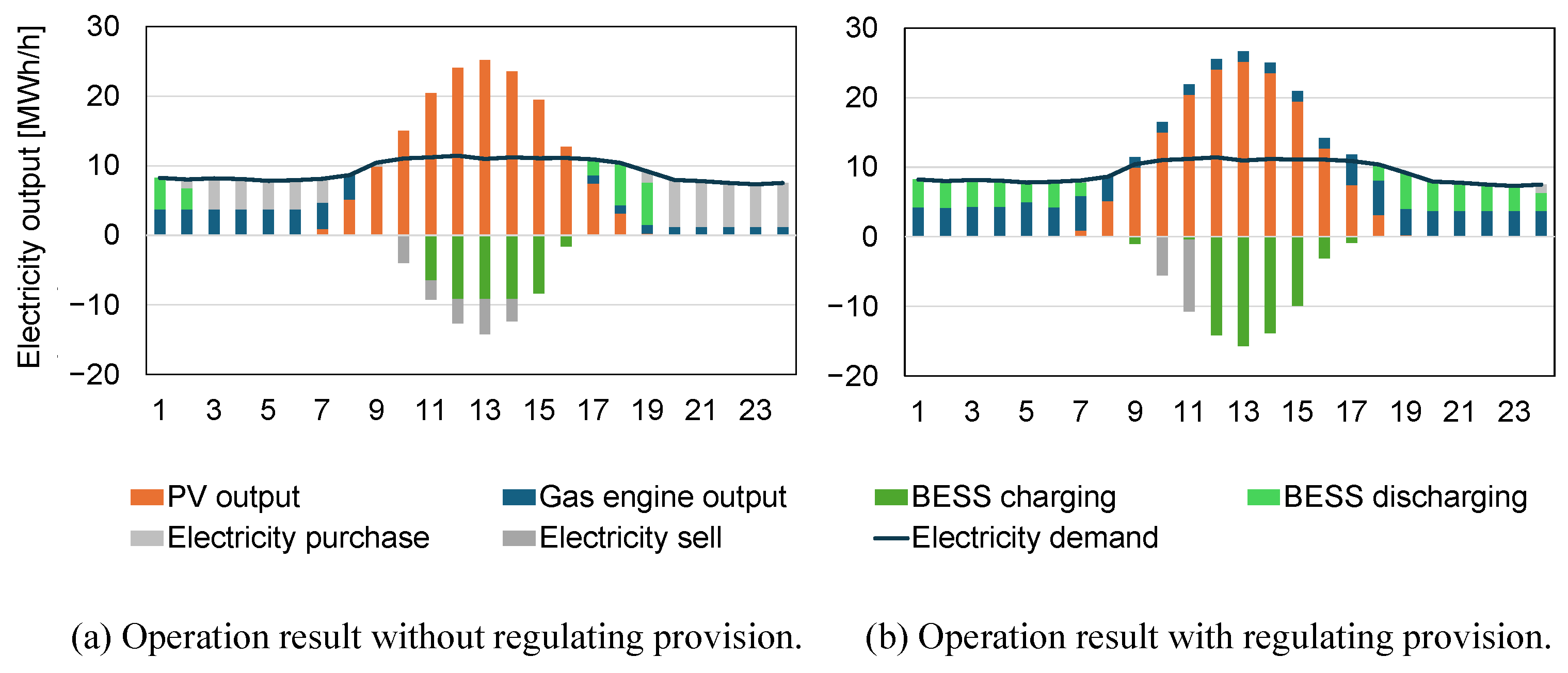

6.2.2. Comparison of Operational Result

6.3. The Effect of CO2 Emission Constraints

6.3.1. The Result of Equipment Sizing

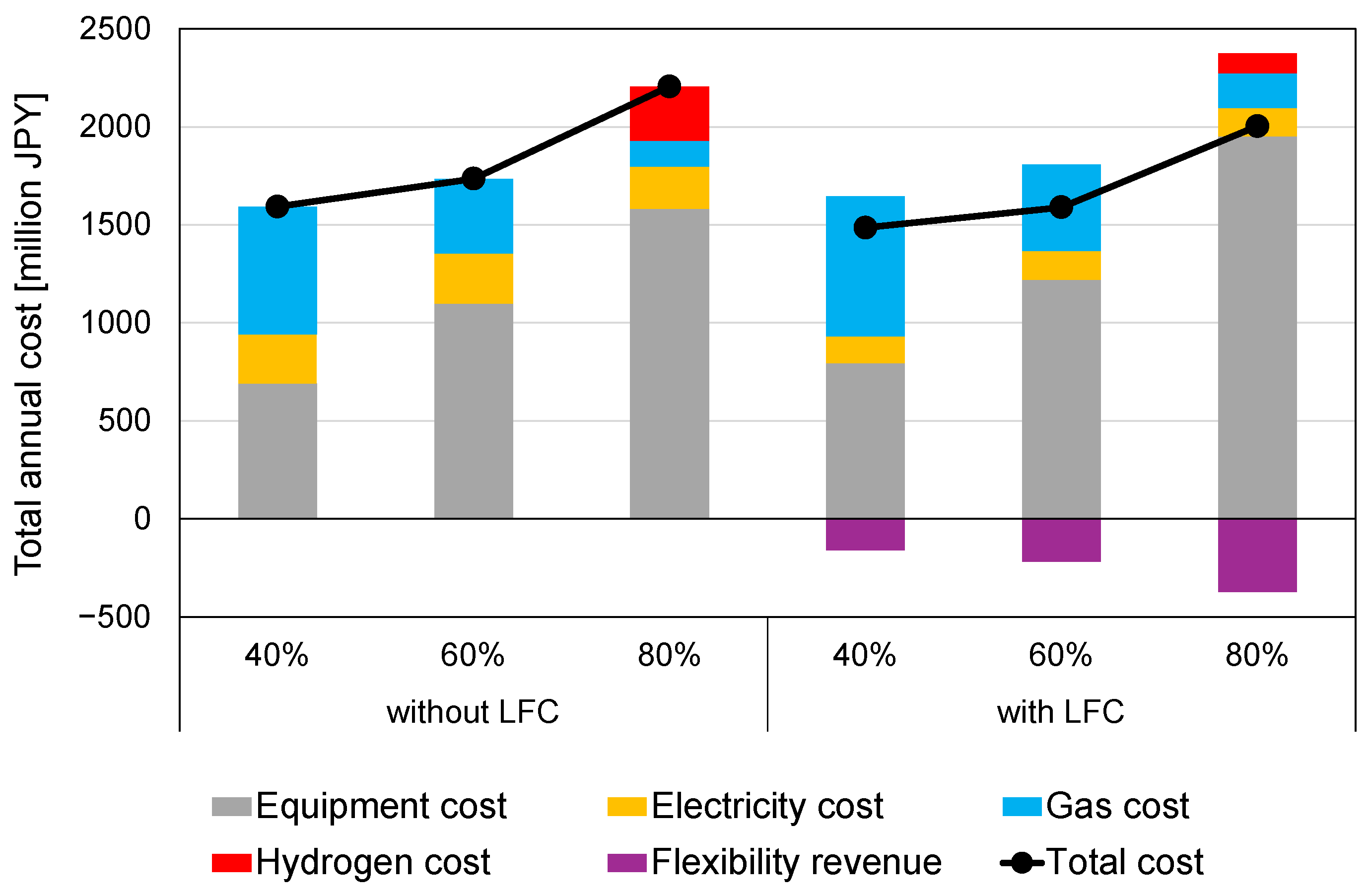

6.3.2. Comparison of Total Cost Under CO2 Emission Reduction Constraints

6.3.3. Comparison of CO2 Emissions Between the ESM and EOM

7. Conclusions

- The proposed framework consists of two models: the Equipment Sizing Optimization Model (ESM), which determines the equipment configuration and approximate operation, and the Equipment Operation Optimization Model (EOM), which calculates detailed operation based on the ESM results. Both models are formulated as mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) models. This two-stage approach reduces computational burden. Although this study focused on the year 2040, the model is applicable to long-term scenario analysis.

- The model formulation allows gas engines and battery energy storage systems (BESS) to provide regulating power equivalent to Load Frequency Control (LFC).

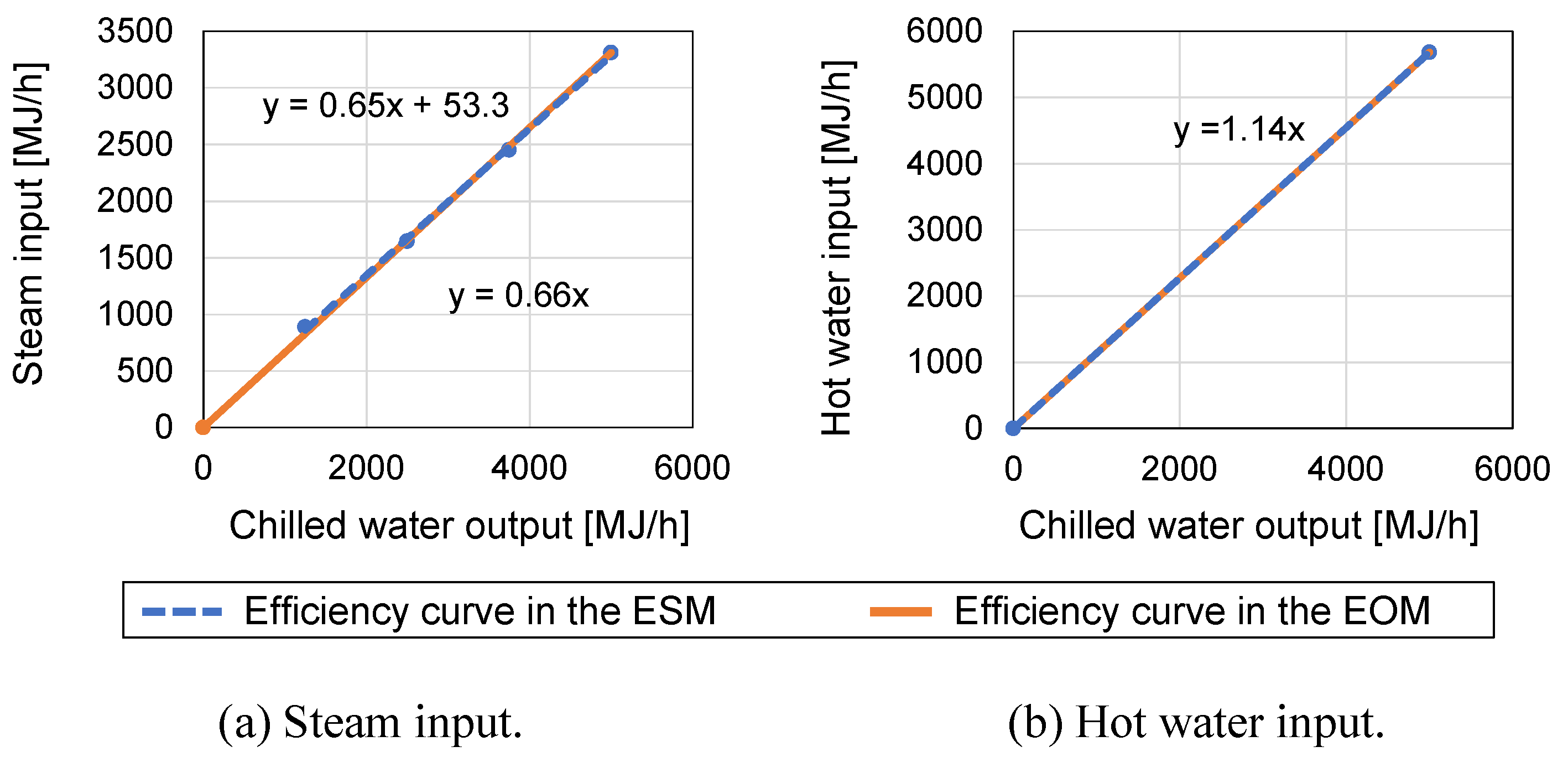

- In the ESM, the partial-load efficiency characteristics of equipment such as gas engines and absorption chillers are represented using linear approximations formulated as a linear programming (LP) model without integer variables by omitting startup and shutdown states. This simplification reduces computational complexity and enables efficient equipment sizing. In contrast, the EOM incorporates these operational details through a full MILP formulation, allowing more accurate representation of equipment behavior in detailed scheduling.

- CO2 emissions, equipment capacities, and the remaining state of charge of the BESS determined in the ESM are passed to the EOM as daily upper bounds and initial conditions. Because the CO2 emissions calculated in the ESM and EOM do not necessarily coincide—owing to the simplified partial-load efficiency representation in the LP formulation—a penalty term is introduced in the EOM to ensure that its daily emissions do not exceed the ESM-derived limits. Similarly, for the state of charge of the BESS and the heat storage tank, penalties for deficit and rewards for surplus are incorporated to prevent inconsistencies between the two models and to maintain feasible energy balances in detailed operation.

- The BESS is modeled with separate cost parameters for power output and storage capacity, allowing the model to determine optimal sizing for both components.

- A case study was conducted to validate the proposed model. The results confirmed that equipment configurations vary depending on the presence of regulating power provision and the level of CO2 emission reduction, and in the 40% CO2 reduction case, the cost reduction achieved through regulating power provision was 6.8%. In addition, the analysis of total system cost under different CO2 reduction targets showed that providing regulating power consistently lowers the overall cost across all scenarios.

- Under the 80% CO2 reduction constraint, the optimization results indicate that hydrogen-related equipment becomes cost-effective and is incorporated into the optimal system configuration. This demonstrates that hydrogen plays an important role in maintaining system flexibility when emission limits become highly stringent. These findings highlight the potential of hydrogen technologies as a key option for future low-carbon energy systems.

- Although this study evaluated cost minimization of a DES providing LFC-type regulating power, the long-term degradation of equipment has not been considered, and impacts on the power system other than regulating power provision—such as voltage fluctuations caused by output variations—were not included in the present analysis. Furthermore, hydrogen was assumed to be supplied externally; however, future extensions of the model could incorporate on-site hydrogen production, for example by introducing a water electrolyzer into the DES to convert surplus PV electricity into hydrogen. Addressing these aspects in future work will further enhance the applicability and robustness of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Gorenstein, D.J.; Ansarin, M.; Bene, C.; van Delzen, T.; van Nuffel, L.; Jagtenberg, H. Increasing Flexibility in the EU Energy System: Technologies and Policies to Enable the Integration of Renewable Electricity Sources; Policy Department for Transformation, Innovation and Health, European Parliament: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Innovation Landscape Brief: Market Integration of Distributed Energy Resources; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, C.; Codani, P.; Perez, Y.; Reneses, J.; Hakvoort, R. Managing electric flexibility from distributed energy resources: A review of incentives for market design. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.B.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Khoshjahan, M.; Dehghanian, P. A comprehensive review on power system flexibility: Concept, services, and products. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99257–99267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, X. Microgrid economic optimal operation of the combined heat and power system with renewable energy. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES General Meeting, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 25–29 July 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Buoro, D.; Pinamonti, P.; Reini, M. Optimization of a distributed cogeneration system with solar district heating. Appl. Energy 2014, 124, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, A.; Adda, M.; Ilinca, A.; Ghandour, M.; Ibrahim, H. Optimizing virtual power plant management: A novel MILP algorithm to minimize levelized cost of energy, technical losses, and greenhouse gas emissions. Energies 2024, 17, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaan, L.; Ismail, L.S.; Gowid, S.; Meskin, N.; Massoud, A.M. Optimal energy dispatch engine for PV-DG-ESS hybrid power plants considering battery degradation and carbon emissions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 58506–58515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmintier, B.S.; Webster, M.D. Heterogeneous unit clustering for efficient operational flexibility modeling. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2014, 29, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meus, J.; Poncelet, K.; Delarue, E. Applicability of a clustered unit commitment model in power system modeling. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 2195–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, S.; Kimura, K.; Suzuki, I.; Ikegami, T. Cross-regional power supply-demand analysis model based on clustered unit commitment. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2022, 215, e23368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.; Ali, M.; Siddique, M.N.I.; Chand, A.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Dong, D.; Pota, H.R. A review of battery energy storage systems for ancillary services in distribution grids: Current status, challenges and future directions. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 971704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, H.; Tang, W.; Rajagopal, R.; Xia, Q.; Kang, C.; Wang, Y. Optimal bidding strategy for microgrids in joint energy and ancillary service markets considering flexible ramping products. Appl. Energy 2017, 205, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancarella, P.; Chicco, G. Integrated energy and ancillary services provision in multi-energy systems. In Proceedings of the IREP Symposium on Bulk Power System Dynamics and Control, Rethymno, Greece, 25–30 August 2013; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Y.; Hara, R.; Kita, H.; Takeda, K. Optimal operation of co-generation system coordinated by aggregator for providing the demand and supply regulation capacity. IEEJ Trans. Power Energy 2018, 139, 56–65. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, S.; Ikegami, T. Robust scheduling for pumping in a water distribution system under the uncertainty of activating regulation reserves. Energies 2021, 14, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyushu Electric Power Transmission and Distribution Co., Inc. Area Supply and Demand Data. Available online: https://www.kyuden.co.jp/td_area_jukyu/jukyu.html (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. Previously Published Information. Available online: https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/saving_and_new/saiene/statistics/past.html (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Nakayama, S.; Azuma, H.; Fukutome, S.; Ogimoto, K. Analysis of value of flexibility in Japan’s power system with increased VRE. Clean Energy 2018, 2, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Institute of Energy Economics, Japan (IEEJ). IEEJ Outlook 2020; IEEJ: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; Available online: https://eneken.ieej.or.jp/data/8650.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Kan, S.; Shibata, Y. Evaluation of the Economics of Renewable Hydrogen Supply in the APEC Region; The Institute of Energy Economics, Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; Available online: https://eneken.ieej.or.jp/data/7944.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Clean Energy Editorial Department. Natural Gas Cogeneration System Equipment Data 2015; Japan Industrial Publishing: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Thermal Engineering Co., Ltd. Catalog of Adsorption Chillers. Available online: https://www.khi.co.jp/corp/kte/product/catalogue/chiller_all/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Daikin Industries, Ltd. Heat Pump Catalog. Available online: https://ec.daikinaircon.com/iportal/cv.do?id=CL22124AXX_1_3&pp=R (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Sumitomo, S.; Akisawa, A.; Ikegami, T.; Nakayama, M. Installation effects of solid oxide fuel cell cogeneration for commercial buildings. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2018, 98, 149–156. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in Japan. Current Status of Renewable Energy Domestically and Abroad and Proposed Discussion Points for This Year’s Feed-In Tariff Calculation Committee. 2018. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/santeii/pdf/038_01_00.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Cole, W.; Frazier, A.W.; Augustine, C. Cost Projections for Utility-Scale Battery Storage; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/79236.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc. CO2 Emissions, Emissions Intensity, and Electricity Sales Volume. Available online: https://www.tepco.co.jp/corporateinfo/illustrated/environment/emissions-co2-j.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Evaluation Results on Progress in Global Warming Countermeasures in the Electric Power Industry Sector. 2020. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/press/files/jp/114277.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Tokyo Gas Co., Ltd. Tokyo Gas CSR Report 2017. Available online: https://www.tokyo-gas.co.jp/sustainability/download/archive/pdf/2017/csrr2017_all.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. Hydrogen Power Generation Handbook 2021. Available online: https://solutions.mhi.com/sites/default/files/assets/pdf/et-jp/hydrogen_power-handbook_jp.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

| Decision Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total installation cost of equipment [JPY] | HW output from GEs [MJ] | ||

| Number of equipment unit | HW output from HEX [MJ] | ||

| Installed storage capacity of the BESS [kWh] | HW output from HPs [MJ] | ||

| Installed power capacity of the BESS [kW] | HW output from TST [MJ] | ||

| Annual total cost of ESM [JPY] | HW supplied to TST [MJ] | ||

| Total electricity purchase cost [JPY] | HW supplied to ACs [MJ] | ||

| Total gas purchase cost [JPY] | CW output from HPs [MJ] | ||

| Total equipment installation cost [JPY] | CW output from TST [MJ] | ||

| Total flexibility revenue [JPY] | CW supplied to TST [MJ] | ||

| Purchased electricity [kWh] | CW output from ACs (steam-driven) [MJ] | ||

| Gas cons. of GEs [] | CW output from ACs (HW-driven) [MJ] | ||

| Gas cons. of GBs [] | Stored HW [MJ] | ||

| Upward regulating power of GEs [kW] | Stored CW [MJ] | ||

| Upward regulating power of the BESS [kW] | Hydrogen cons. of HBs [] | ||

| Downward regulating power of GEs [kW] | emissions [kg-] | ||

| Downward regulating power of the BESS [kW] | Total annual emissions [kg-] | ||

| Electricity generated by GEs [kWh] | Daily total cost of EOM [JPY] | ||

| Electricity generated by PV systems [kWh] | Net reward/penalty of remaining storage [JPY] | ||

| BESS discharge energy [kWh] | Shortage amount of storage [kWh], [MJ] | ||

| BESS charge energy [kWh] | Surplus amount of storage [kWh], [MJ] | ||

| Electricity sold [kWh] | Number of operating GEs [unit] | ||

| Electricity cons. of HPs [kWh] | Number of GEs started [unit] | ||

| Steam output from GEs [MJ] | Number of GEs stopped [unit] | ||

| Steam output from GBs [MJ] | Number of operating ACs [unit] | ||

| Steam output from HBs [MJ] | Number of ACs started [unit] | ||

| Steam supplied to ACs [MJ] | Number of ACs stopped [unit] | ||

| Steam supplied to HEX [MJ] | |||

| Index | |||

| m | Month index in a year (1 12) [month] | Index of HP for HW usage | |

| d | Day index in a year () [day] | Index of HP for CW usage | |

| t | Hourly time step in a year (1 8760) [hour] | Index of PV system | |

| h | Hourly time step () [hour] | Index of the BESS storage capacity | |

| Index of equipment | Index of the BESS power capacity | ||

| Index of GE | Index of HB | ||

| Index of GB | Index of HEX | ||

| Index of AC | Index of TST for HW usage | ||

| Index of HP | Index of TST for CW usage | ||

| Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital recovery factor | – | BESS round trip efficiency [-] | 0.95 | ||

| r | Discount rate | 0.04 | BESS time loss factor [-/day] | 0.01 | |

| n | Useful life [year] | 15 | Thermal storage round trip efficiency [-] | 0.98 | |

| Install. cost of GE [JPY/kW] | 290,000 | Thermal storage time loss factor [-/day] | 0.15 | ||

| Install. cost of GB [JPY/MJ] | 8100 | Regulating range coefficient (GE) [-] | 0.30 | ||

| Install. cost of AC [JPY/MJ] | 23,300 | Regulating range coefficient (BESS) [-] | 0.05 | ||

| Install. cost of HP [JPY/MJ] | 51,800 | Per-unit output of PV system [kW/kW] | – | ||

| Install. cost of PV system [JPY/kW] | 116,666 | factor of gas [kg-] | 2.29 | ||

| Install. cost of BESS storage unit [JPY/kWh] | 17,640 | factor of electricity [kg-kWh] | 0.29 | ||

| Install. cost of BESS power unit [JPY/kW] | 26,888 | Annual CO2 emissions (reference) [t-] | 35,657 | ||

| Install. cost of HB [JPY/MJ] | 13,450 | p | reduction rate [-] | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 | |

| Electricity price [JPY/kWh] | – | Penalty cost (BESS) [JPY/kWh] | |||

| Gas price [JPY/] | – | Reward (BESS) [JPY/kWh] | |||

| Upward flexibility price [JPY/kW] | – | Penalty cost (TST, HW) [JPY/MJ] | |||

| Downward flexibility price [JPY/kW] | – | Penalty cost (TST, CW) [JPY/MJ] | |||

| Electricity demand [kWh] | – | Number of equipment unit in the ESM [unit] | – | ||

| Steam demand [MJ] | – | Operating GEs at final hour of day d-1 [unit] | – | ||

| HW demand [MJ] | – | Gas cons. coefficient [(/h)/kW] | 0.17 | ||

| CW demand [MJ] | – | No-load gas cons. coefficient [/h] | 24.9 | ||

| Rated electricity output per GE [kW] | 1250 | Additional gas cons. for startup [/h] | – | ||

| Rated electricity output per PV unit [kW] | 1000 | Steam gen. coefficient [(MJ/h)/kW] | 0.91 | ||

| Rated steam output per GB [MJ/h] | 5000 | No-load steam gen. coefficient [MJ/h] | 614 | ||

| Rated steam output per HB [MJ/h] | 5000 | HW gen. coefficient [(MJ/h)/kW] | 1.74 | ||

| Rated HW output per HP [MJ/h] | 1000 | No-load HW gen. coefficient [MJ/h] | 328 | ||

| Rated CW output per HP [MJ/h] | 1000 | Steam gen. coefficient [(MJ/h)/(MJ/h)] | 0.65 | ||

| Rated CW output per AC [MJ/h] | 5000 | No-load steam gen. coefficient [MJ/h] | 53.3 | ||

| Rated TST capacity (HW) [MJ] | 60,000 | Additional heat cons. for startup [MJ/unit] | – | ||

| Rated TST capacity (CW) [MJ] | 40,000 | Additional heat cons. for startup [MJ/unit] | – | ||

| Steam efficiency of GE [(MJ/h)/kW] | 1.39 | SOC at hour h on day d in the ESM [kWh] | – | ||

| HW efficiency of GE [(MJ/h)/kW] | 2.01 | SOC at hour h on day d [kWh] | – | ||

| Gas cons. efficiency of GE [(h)/kW] | 0.19 | BESS power capacity in the ESM [kWh] | – | ||

| Steam efficiency of GB [MJ/kWh] | 0.95 | BESS storage capacity in the ESM [kWh] | – | ||

| Steam efficiency of AC [(MJ/h)/(MJ/h)] | 0.66 | Stored HW at hour h on day d in the ESM [MJ] | – | ||

| HW efficiency of AC [(MJ/h)/(MJ/h)] | 1.14 | Stored HW at hour h on day d [MJ] | – | ||

| COP of HP (HW) [-] | 4.3 | Daily CO2 emission limit in the ESM [kg-CO2] | – | ||

| COP of HP (CW) [-] | 4.1 | Penalty cost (CO2 surplus) | |||

| HW efficiency of HEX [-] | 0.98 | ||||

| Load Factor | 50% | 75% | 100% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power generation efficiency [%] | 38.9 | 41.7 | 43.1 |

| Steam recovery efficiency [%] | 20.1 | 18.7 | 16.6 |

| Hot water recovery efficiency [%] | 24.7 | 23.9 | 24.1 |

| Load Factor | 25% | 50% | 75% | 100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COP of steam consumption [-] | 1.41 | 1.52 | 1.53 | 1.51 |

| COP of hot water consumption [-] | 0.88 |

| Year | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2040 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 Emission Factor [kg-kWh] | 0.441 | 0.4055 | 0.370 | 0.299 |

| Equipment Type | Unit | Installed Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Gas engine | kW | 10,000 |

| Gas boiler | MJ/h | 15,000 |

| Absorption chiller | MJ/h | 15,000 |

| Equipment Type | Unit | Baseline Case | Without LFC | With LFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas engine | kW | 10,000 | 5000 | 6250 |

| Gas boiler | MJ/h | 15,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 |

| Absorption chiller | MJ/h | 15,000 | 15,000 | 10,000 |

| Heat pump | MJ/h | - | 0 | 0 |

| PV | kW | - | 38,000 | 38,000 |

| BESS (Storage) | kWh | - | 41,554 | 57,758 |

| BESS (Power) | kW | - | 9117 | 28,879 |

| Item | Unit | Without LFC | With LFC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment cost | million JPY | 690 | 793 |

| Electricity purchase cost | million JPY | 252 | 139 |

| Gas purchase cost | million JPY | 651 | 713 |

| Hydrogen purchase cost | million JPY | 0 | 0 |

| Revenue from regulating power provision | million JPY | 0 | −161 |

| Total annual cost | million JPY | 1593 | 1485 |

| CO2 reduction cost | JPY/t-CO2 | 18,306 | 10,735 |

| Item | Unit | Without LFC | With LFC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40% | 60% | 80% | 40% | 60% | 80% | |||

| Gas engine | kW | 5000 | 2500 | 0 | 6250 | 3750 | 0 | |

| Gas boiler | MJ/h | 20,000 | 25,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | |

| Absorption chiller | MJ/h | 15,000 | 10,000 | 5000 | 15,000 | 10,000 | 5000 | |

| Heat pump | MJ/h | 0 | 6000 | 13,000 | 0 | 6000 | 13,000 | |

| PV generation | kW | 38,000 | 64,000 | 96,000 | 38,000 | 63,000 | 100,000 | |

| BESS (storage) | kWh | 41,554 | 108,128 | 178,640 | 57,758 | 123,834 | 252,304 | |

| BESS (power) | kW | 9117 | 21,232 | 32,263 | 28,879 | 61,917 | 126,152 | |

| Hydrogen boiler | MJ/h | 0 | 0 | 5000 | 0 | 0 | 5000 | |

| Item | Unit | Baseline | Without LFC | With LFC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40% | 60% | 80% | 40% | 60% | 80% | ||||

| Annual CO2 Emission in ESM | t-CO2/yr | – | 21,394 | 14,263 | 7131 | 21,394 | 14,263 | 7131 | |

| Annual CO2 Emission in EOM | t-CO2/yr | 35,657 | 21,387 | 14,272 | 7131 | 21,367 | 14,255 | 7131 | |

| CO2 Reduction Rate | % | – | 40.02% | 59.97% | 80.00% | 40.08% | 60.02% | 80.00% | |

| Max. Daily CO2 Cap | % | – | 5.1% | 11.1% | – | – | 2.4% | – | |

| Overshoot Rate (Date) | (13 August) | (28 July) | (28 July) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Miyazaki, A.; Muraoka, M.; Ikegami, T. Optimization Models for Distributed Energy Systems Under CO2 Constraints: Sizing, Operating, and Regulating Power Provision. Energies 2026, 19, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010265

Miyazaki A, Muraoka M, Ikegami T. Optimization Models for Distributed Energy Systems Under CO2 Constraints: Sizing, Operating, and Regulating Power Provision. Energies. 2026; 19(1):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010265

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiyazaki, Azusa, Miku Muraoka, and Takashi Ikegami. 2026. "Optimization Models for Distributed Energy Systems Under CO2 Constraints: Sizing, Operating, and Regulating Power Provision" Energies 19, no. 1: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010265

APA StyleMiyazaki, A., Muraoka, M., & Ikegami, T. (2026). Optimization Models for Distributed Energy Systems Under CO2 Constraints: Sizing, Operating, and Regulating Power Provision. Energies, 19(1), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010265