Machine Learning for Sustainable Urban Energy Planning: A Comparative Model Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A systematic, multi-city benchmarking of Prophet, LSTM, GRU, and TCN across fifteen U.S. cities with diverse climatic and geographic conditions.

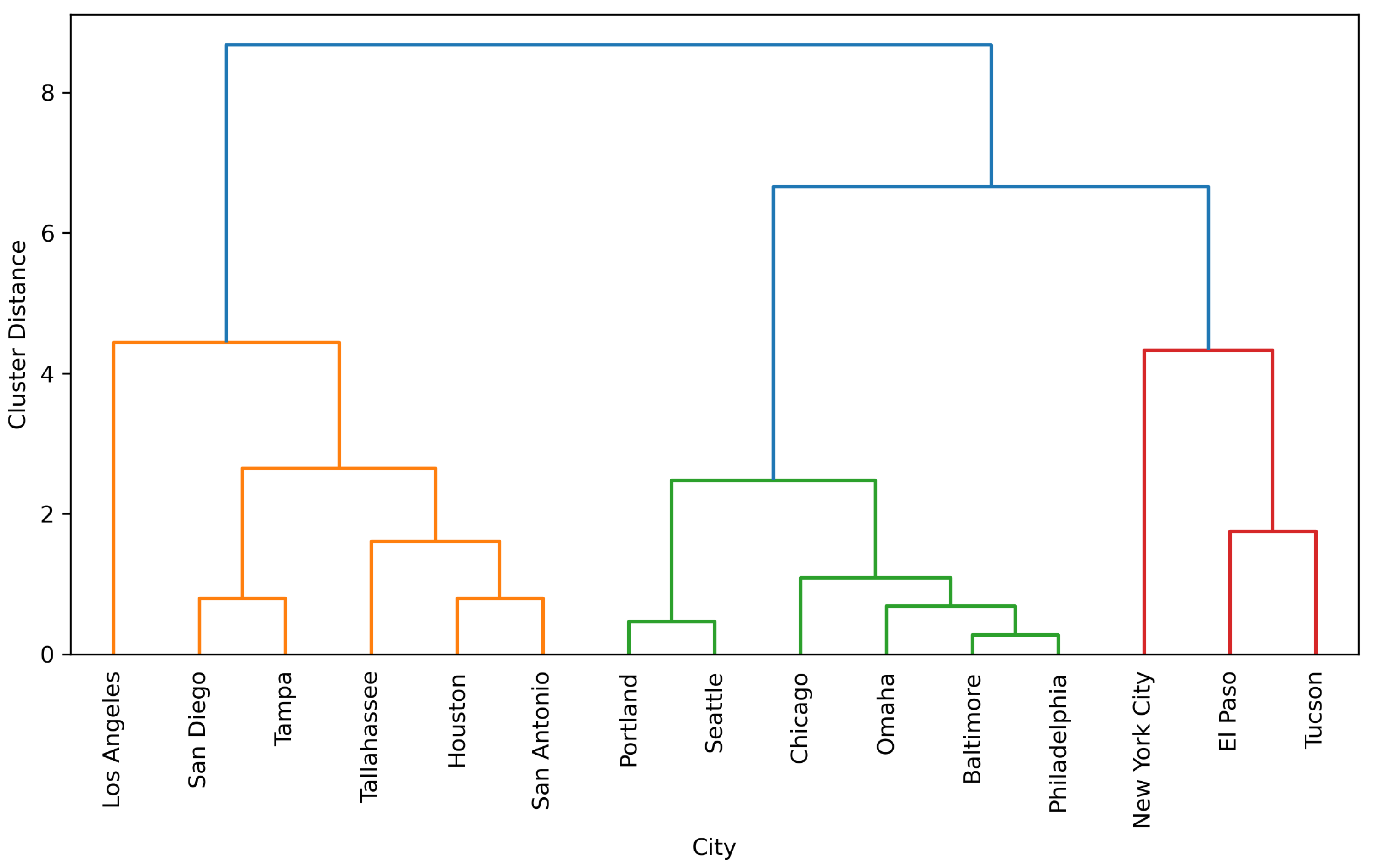

- A climate-aware evaluation framework based on clustering cities using the coefficient of variation of key meteorological variables.

- A multi-horizon performance assessment (1, 6, 12, and 24 h) using MAE, MSE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2.

- Quantitative evidence that Prophet consistently outperforms deep learning models at longer forecast horizons across all climatic clusters.

- Empirical demonstration that urban climate variability is a key determinant of forecasting reliability.

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

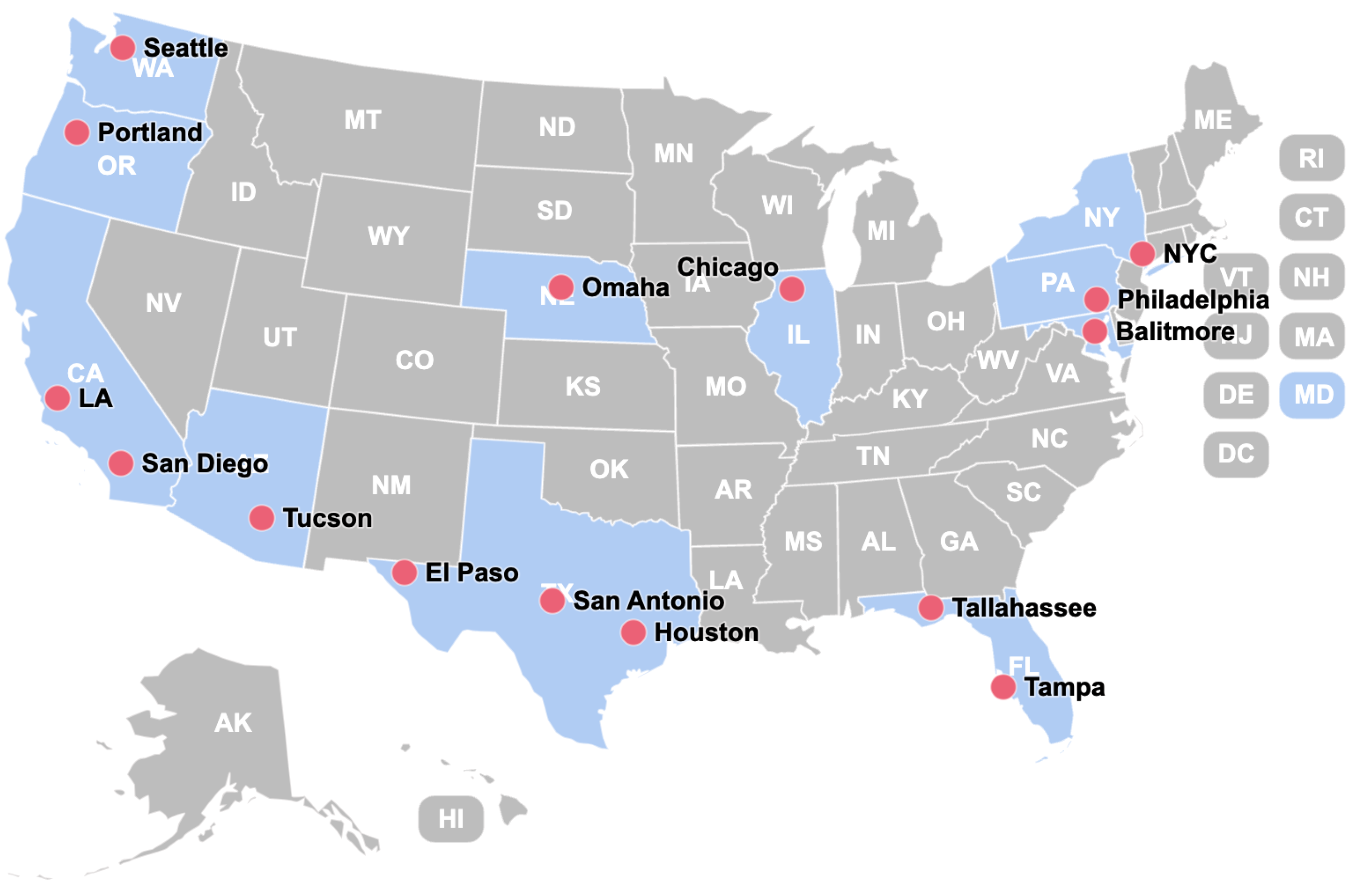

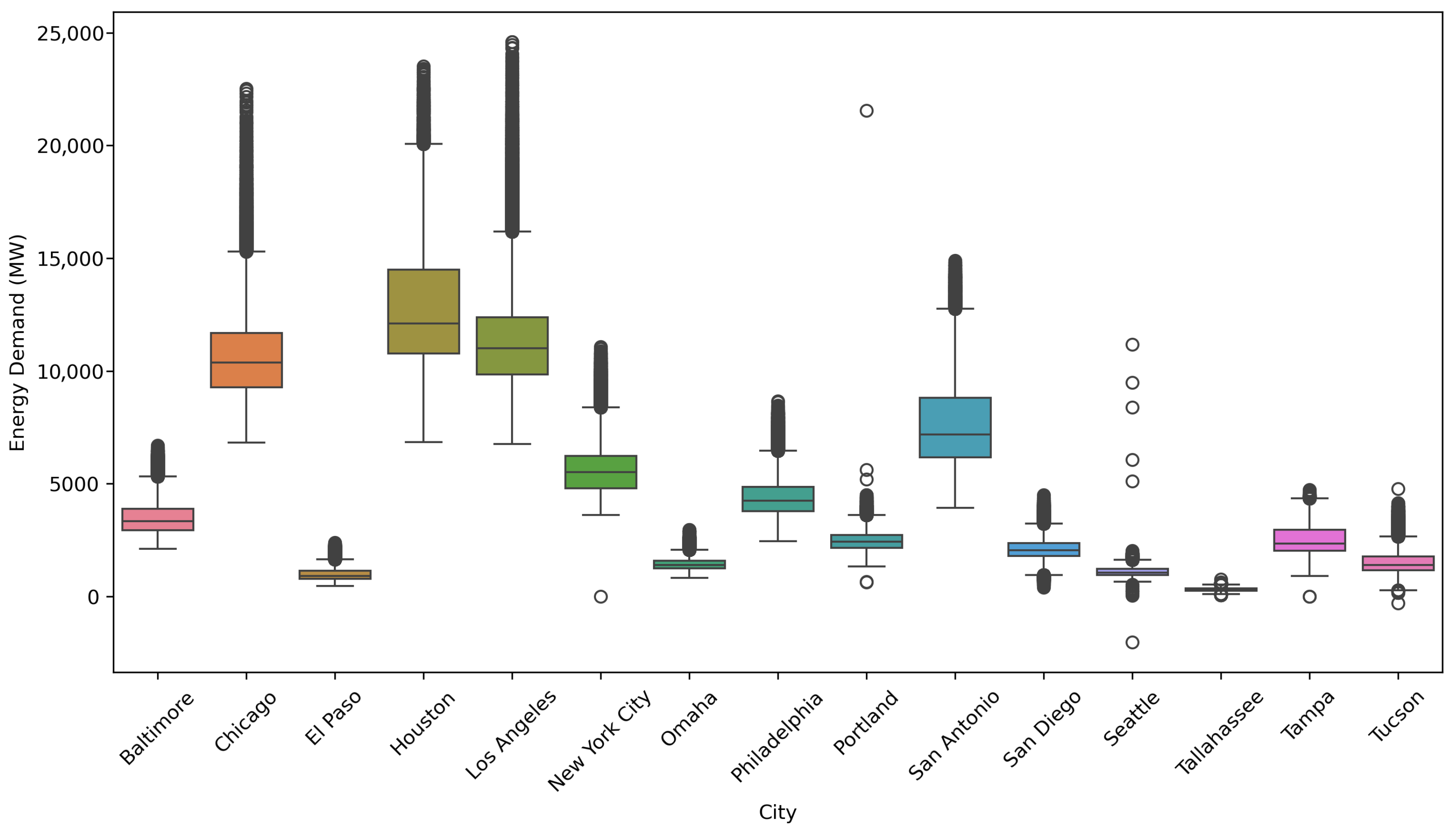

3.1. Data

3.2. Preprocessing

3.3. Model Development

3.4. Model Evaluation

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Measures the average magnitude of the errors in the predictions, providing a direct interpretation of the typical deviation between predicted and observed values.

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): Calculates the average of the squared differences between predicted and observed values, giving higher weight to larger errors.

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): The square root of MSE, which expresses the error in the same units as the original observations and allows easier interpretation.

- Coefficient of Determination (R2) Represents the proportion of variance in the observed data explained by the model. Values closer to 1 indicate better explanatory power.

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): Measures the average percentage deviation of predicted values from actual observations, providing an interpretable scale-independent metric for comparing performance across cities with varying energy demand levels.

3.5. Performance Across Cities

3.6. Significance Testing

3.7. Clustering of Climate Variables

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance for Individual Cities

4.2. Model Performance for City Clusters

4.3. Within-Cluster Differences in Model Performance

4.4. Clustering Analysis of Climate Variables

4.5. Linking Model Characteristics to Forecasting Performance

5. Discussion

5.1. Model Performance and City-Specific Challenges

5.2. Cluster Analysis and the Role of Climatic Variables

5.3. Weather Data Uncertainty and Model Robustness

5.4. Implications of Forecast Horizons

5.5. Broader Implications for Future Urban Energy Systems

5.6. Methodological and Data Limitations

5.7. Policy Implications for Regional Planning and Energy Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Geographic Differences in Cities

| City | Location | Climate | Key Geographic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baltimore | East Coast, along the Patapsco River | Temperate climate, mild winters, hot humid summers | Waterfront, historical port city |

| Chicago | Shore of Lake Michigan | Humid continental, cold winters, hot summers | Dense urban core, major economic and cultural hub |

| El Paso | West Texas, near the US-Mexico border | Hot desert, very hot summers, mild winters | Desert region, cultural mix due to border proximity |

| Houston | Gulf Coast | Humid subtropical, hot summers, mild winters | Sprawling urban landscape, oil and gas industry |

| Los Angeles | Pacific Coast | Mediterranean, mild wet winters, hot dry summers | Coastal, sprawling urban environment, diverse population |

| New York City | East Coast, on the Hudson River | Humid subtropical, cold winters, hot summers | Dense urban fabric, major global financial and cultural center |

| Omaha | Great Plains | Continental, cold winters, hot summers | Mid-sized city, agricultural and transportation history |

| Philadelphia | East Coast | Humid subtropical, hot humid summers, cold winters | Historical city, birthplace of American independence |

| Portland | Pacific Northwest | Temperate oceanic, wet mild winters, dry warm summers | Surrounded by natural landscapes, green spaces, environmental awareness |

| San Antonio | Central Texas | Hot semi-arid, hot summers, mild winters | Historical sites (e.g., Alamo), growing tech and military presence |

| San Diego | Pacific Coast | Mediterranean, mild wet winters, warm dry summers | Beaches, military presence, biotechnology sector |

| Seattle | Pacific Northwest | Temperate oceanic, wet mild winters, cool summers | Tech hub, surrounded by water, mountains, and forests |

| Tallahassee | Florida Panhandle | Humid subtropical, hot humid summers, mild winters | Mix of urban and rural landscapes, state capital |

| Tampa | Gulf Coast | Humid subtropical, hot humid summers, mild winters | Gulf Coast location, vibrant tourism sector |

| Tucson | Sonoran Desert | Hot desert, very hot summers, mild winters | Desert landscapes, surrounded by mountains |

Appendix B. City Performance

| City | Model | Horizon h | MAE | MSE | RMSE | R2 | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltimore | GRU | 1 | 88.4786 | 14,690.1486 | 120.7399 | 0.9745 | 2.5452 |

| Baltimore | GRU | 6 | 171.5476 | 60,469.7216 | 244.4870 | 0.8953 | 4.7924 |

| Baltimore | GRU | 12 | 216.4569 | 92,818.8963 | 303.3455 | 0.8403 | 5.9993 |

| Baltimore | GRU | 24 | 254.4262 | 122,873.0359 | 349.5169 | 0.7883 | 7.1577 |

| Baltimore | LSTM | 1 | 101.1091 | 17,898.7000 | 133.6133 | 0.9688 | 2.9368 |

| Baltimore | LSTM | 6 | 184.9285 | 65,262.6987 | 254.8649 | 0.8869 | 5.2260 |

| Baltimore | LSTM | 12 | 223.3107 | 95,815.1164 | 308.7576 | 0.8346 | 6.2756 |

| Baltimore | LSTM | 24 | 265.6068 | 129,445.3420 | 358.8136 | 0.7769 | 7.5113 |

| Baltimore | Prophet | 1 | 16.8647 | 511.2048 | 22.6098 | 0.9988 | 0.5033 |

| Baltimore | Prophet | 6 | 36.9673 | 2267.7375 | 47.6208 | 0.9964 | 1.2099 |

| Baltimore | Prophet | 12 | 59.2229 | 4514.7921 | 67.1922 | 0.9877 | 1.4903 |

| Baltimore | Prophet | 24 | 12.0533 | 195.7111 | 13.9897 | 0.9994 | 0.3363 |

| Baltimore | TCN | 1 | 97.2371 | 17,544.9835 | 131.5025 | 0.9699 | 2.7376 |

| Baltimore | TCN | 6 | 183.8302 | 67,873.9032 | 259.5152 | 0.8820 | 5.1792 |

| Baltimore | TCN | 12 | 221.1464 | 97,361.6977 | 311.0728 | 0.8311 | 6.1941 |

| Baltimore | TCN | 24 | 257.9645 | 126,072.5177 | 354.4056 | 0.7823 | 7.2184 |

| Chicago | GRU | 1 | 411.9057 | 710,790.8828 | 730.9077 | 0.8746 | 3.8183 |

| Chicago | GRU | 6 | 522.7851 | 950,437.3204 | 900.7756 | 0.8223 | 4.7208 |

| Chicago | GRU | 12 | 646.0938 | 1,216,845.0049 | 1046.8283 | 0.7656 | 5.8427 |

| Chicago | GRU | 24 | 750.6769 | 1,492,227.2140 | 1176.0157 | 0.7077 | 6.8169 |

| Chicago | LSTM | 1 | 396.2622 | 790,257.1815 | 762.4075 | 0.8613 | 3.6013 |

| Chicago | LSTM | 6 | 541.9760 | 1,073,265.1010 | 950.0262 | 0.8015 | 4.8691 |

| Chicago | LSTM | 12 | 652.4830 | 1,213,519.5675 | 1049.7466 | 0.7649 | 5.9291 |

| Chicago | LSTM | 24 | 744.1171 | 1,549,057.4026 | 1198.6711 | 0.6965 | 6.6916 |

| Chicago | Prophet | 1 | 216.4327 | 65,043.4487 | 255.0362 | 0.9667 | 1.9727 |

| Chicago | Prophet | 6 | 302.1496 | 102,524.5160 | 320.1945 | 0.8943 | 3.2633 |

| Chicago | Prophet | 12 | 380.7706 | 240,835.4790 | 490.7499 | 0.9456 | 2.8188 |

| Chicago | Prophet | 24 | 230.1452 | 125,196.5957 | 353.8313 | 0.9709 | 1.7634 |

| Chicago | TCN | 1 | 489.4370 | 1,185,090.8360 | 911.1978 | 0.7957 | 4.5444 |

| Chicago | TCN | 6 | 654.3732 | 1,545,219.8134 | 1124.2802 | 0.7185 | 5.9340 |

| Chicago | TCN | 12 | 768.8809 | 1,622,442.7801 | 1214.0035 | 0.6873 | 6.9259 |

| Chicago | TCN | 24 | 815.4084 | 1,911,625.9107 | 1320.1534 | 0.6322 | 7.3344 |

| El Paso | GRU | 1 | 56.2361 | 8237.5746 | 88.1332 | 0.9026 | 5.7367 |

| El Paso | GRU | 6 | 64.3789 | 10,226.5458 | 99.4290 | 0.8810 | 6.5026 |

| El Paso | GRU | 12 | 66.9775 | 11,318.2860 | 104.3706 | 0.8676 | 6.7730 |

| El Paso | GRU | 24 | 77.5814 | 14,502.6749 | 118.9832 | 0.8320 | 7.6801 |

| El Paso | LSTM | 1 | 69.6788 | 10,765.3048 | 101.9033 | 0.8765 | 7.3847 |

| El Paso | LSTM | 6 | 76.0051 | 12,432.8817 | 110.6681 | 0.8584 | 7.9864 |

| El Paso | LSTM | 12 | 81.7712 | 14,279.8511 | 118.6187 | 0.8381 | 8.4867 |

| El Paso | LSTM | 24 | 89.0802 | 17,219.6905 | 130.1118 | 0.8034 | 9.1766 |

| El Paso | Prophet | 1 | 16.6351 | 571.1110 | 23.8979 | 0.9830 | 1.7502 |

| El Paso | Prophet | 6 | 32.1678 | 1579.7107 | 39.7456 | 0.9150 | 3.5299 |

| El Paso | Prophet | 12 | 47.0859 | 2997.8971 | 54.7531 | 0.9827 | 4.1459 |

| El Paso | Prophet | 24 | 20.7198 | 639.9425 | 25.2971 | 0.9845 | 2.1519 |

| El Paso | TCN | 1 | 59.8426 | 9764.6339 | 94.9026 | 0.8847 | 6.1376 |

| El Paso | TCN | 6 | 73.1937 | 13,165.6902 | 113.1404 | 0.8472 | 7.5571 |

| El Paso | TCN | 12 | 82.6602 | 15,549.2825 | 122.4373 | 0.8206 | 8.5019 |

| El Paso | TCN | 24 | 93.9238 | 19,376.3633 | 137.8636 | 0.7759 | 9.5898 |

| Houston | GRU | 1 | 331.5139 | 219,891.2710 | 462.4759 | 0.9734 | 2.5519 |

| Houston | GRU | 6 | 607.8856 | 743,561.5799 | 858.8804 | 0.9069 | 4.6952 |

| Houston | GRU | 12 | 721.1868 | 1,040,957.4266 | 1014.7068 | 0.8680 | 5.6419 |

| Houston | GRU | 24 | 813.9539 | 1,287,635.6239 | 1127.8176 | 0.8378 | 6.4065 |

| Houston | LSTM | 1 | 338.0176 | 205,037.3653 | 451.4008 | 0.9736 | 2.6931 |

| Houston | LSTM | 6 | 608.9744 | 719,818.4786 | 843.1774 | 0.9075 | 4.7661 |

| Houston | LSTM | 12 | 756.8425 | 1,076,929.7718 | 1032.1927 | 0.8628 | 5.9916 |

| Houston | LSTM | 24 | 798.2694 | 1,223,494.5238 | 1099.8097 | 0.8432 | 6.3466 |

| Houston | Prophet | 1 | 74.9349 | 7922.9250 | 89.0108 | 0.9982 | 0.6068 |

| Houston | Prophet | 6 | 78.2871 | 10,074.6494 | 100.3726 | 0.9958 | 0.6570 |

| Houston | Prophet | 12 | 135.5303 | 26,278.3719 | 162.1061 | 0.9970 | 0.9045 |

| Houston | Prophet | 24 | 37.4470 | 1966.7719 | 44.3483 | 0.9996 | 0.2860 |

| Houston | TCN | 1 | 287.3305 | 167,616.7009 | 402.5336 | 0.9781 | 2.2747 |

| Houston | TCN | 6 | 565.2385 | 689,801.6394 | 819.6367 | 0.9104 | 4.4444 |

| Houston | TCN | 12 | 697.4020 | 987,720.1023 | 984.4306 | 0.8723 | 5.5042 |

| Houston | TCN | 24 | 777.9344 | 1,208,719.1228 | 1089.3710 | 0.8443 | 6.2027 |

| San Diego | GRU | 1 | 287.3305 | 167,616.7009 | 402.5336 | 0.9781 | 2.2747 |

| San Diego | GRU | 6 | 565.2385 | 689,801.6394 | 819.6367 | 0.9104 | 4.4444 |

| San Diego | GRU | 12 | 697.4020 | 987,720.1023 | 984.4306 | 0.8723 | 5.5042 |

| San Diego | GRU | 24 | 777.9344 | 1,208,719.1228 | 1089.3710 | 0.8443 | 6.2027 |

| San Diego | LSTM | 1 | 93.8797 | 17,313.6341 | 130.8529 | 0.9253 | 4.9417 |

| San Diego | LSTM | 6 | 131.4677 | 35,510.5746 | 187.3900 | 0.8474 | 6.9734 |

| San Diego | LSTM | 12 | 134.6661 | 36,960.2088 | 191.8474 | 0.8407 | 7.2015 |

| San Diego | LSTM | 24 | 140.1702 | 40,967.1217 | 202.0392 | 0.8240 | 7.3749 |

| San Diego | Prophet | 1 | 55.7399 | 6751.6296 | 82.1683 | 0.7232 | 2.5565 |

| San Diego | Prophet | 6 | 59.9933 | 4967.7775 | 70.4825 | 0.3951 | 3.0492 |

| San Diego | Prophet | 12 | 57.7483 | 10,554.9469 | 102.7373 | 0.8188 | 3.4295 |

| San Diego | Prophet | 24 | 29.7797 | 1196.9707 | 34.5973 | 0.9706 | 1.3249 |

| San Diego | TCN | 1 | 88.2167 | 15,510.0581 | 123.7240 | 0.9333 | 4.5919 |

| San Diego | TCN | 6 | 121.0016 | 31,945.1841 | 178.1373 | 0.8625 | 6.3700 |

| San Diego | TCN | 12 | 124.1561 | 33,359.8352 | 182.3083 | 0.8560 | 6.5187 |

| San Diego | TCN | 24 | 139.3537 | 41,248.7149 | 202.6446 | 0.8226 | 7.3410 |

| Seattle | GRU | 1 | 42.1933 | 8403.6248 | 87.5621 | 0.8267 | 3.9526 |

| Seattle | GRU | 6 | 45.7174 | 8989.0631 | 91.0384 | 0.8142 | 4.2440 |

| Seattle | GRU | 12 | 52.9378 | 10,224.3751 | 98.0363 | 0.7873 | 4.9264 |

| Seattle | GRU | 24 | 58.1157 | 11,280.7365 | 103.8591 | 0.7639 | 5.4098 |

| Seattle | LSTM | 1 | 47.3968 | 9126.3831 | 92.8646 | 0.8097 | 4.4371 |

| Seattle | LSTM | 6 | 52.0163 | 9795.6626 | 96.5682 | 0.7952 | 4.9043 |

| Seattle | LSTM | 12 | 58.1933 | 10,880.3089 | 101.7637 | 0.7722 | 5.5820 |

| Seattle | LSTM | 24 | 60.7532 | 11,770.3553 | 106.8350 | 0.7521 | 5.6413 |

| Seattle | Prophet | 1 | 44.5926 | 2633.2793 | 51.3155 | 0.9473 | 3.4631 |

| Seattle | Prophet | 6 | 28.1144 | 1166.0603 | 34.1476 | 0.9740 | 2.4748 |

| Seattle | Prophet | 12 | 20.5678 | 697.2112 | 26.4048 | 0.9759 | 2.4150 |

| Seattle | Prophet | 24 | 34.4994 | 2026.5496 | 45.0172 | 0.9432 | 3.0491 |

| Seattle | TCN | 1 | 45.4501 | 9343.5074 | 93.7721 | 0.8053 | 4.2203 |

| Seattle | TCN | 6 | 52.0411 | 10,508.2511 | 99.8841 | 0.7807 | 4.8083 |

| Seattle | TCN | 12 | 57.7781 | 11,694.4309 | 106.5482 | 0.7538 | 5.3545 |

| Seattle | TCN | 24 | 63.5066 | 12,805.7487 | 111.7856 | 0.7293 | 5.8945 |

| Tallahassee | GRU | 1 | 13.7545 | 358.8016 | 18.8187 | 0.9463 | 4.4417 |

| Tallahassee | GRU | 6 | 21.0256 | 874.3500 | 29.4065 | 0.8704 | 6.7393 |

| Tallahassee | GRU | 12 | 26.2469 | 1329.9253 | 36.2082 | 0.8049 | 8.5227 |

| Tallahassee | GRU | 24 | 28.9437 | 1669.4616 | 40.6030 | 0.7519 | 9.4233 |

| Tallahassee | LSTM | 1 | 13.7034 | 348.0109 | 18.5908 | 0.9486 | 4.5107 |

| Tallahassee | LSTM | 6 | 21.4450 | 887.3086 | 29.6149 | 0.8703 | 6.8613 |

| Tallahassee | LSTM | 12 | 25.9273 | 1246.1083 | 35.0759 | 0.8158 | 8.6454 |

| Tallahassee | LSTM | 24 | 29.6922 | 1682.5765 | 40.8275 | 0.7500 | 9.7838 |

| Tallahassee | Prophet | 1 | 7.1543 | 110.5420 | 10.5139 | 0.9238 | 2.4172 |

| Tallahassee | Prophet | 6 | 6.3782 | 48.1738 | 6.9407 | 0.9590 | 2.4493 |

| Tallahassee | Prophet | 12 | 7.0133 | 77.7383 | 8.8169 | 0.9761 | 1.8121 |

| Tallahassee | Prophet | 24 | 5.0186 | 47.4559 | 6.8888 | 0.9810 | 1.4878 |

| Tallahassee | TCN | 1 | 12.6412 | 311.0719 | 17.5858 | 0.9544 | 4.1127 |

| Tallahassee | TCN | 6 | 20.9350 | 876.2519 | 29.4854 | 0.8714 | 6.7059 |

| Tallahassee | TCN | 12 | 25.2557 | 1242.6937 | 35.1130 | 0.8168 | 8.3671 |

| Tallahassee | TCN | 24 | 28.9647 | 1659.1847 | 40.5109 | 0.7549 | 9.4831 |

| Tuscon | GRU | 1 | 91.6368 | 15,922.7464 | 124.5806 | 0.9453 | 6.8071 |

| Tuscon | GRU | 6 | 133.9853 | 35,488.8612 | 184.8731 | 0.8820 | 9.8593 |

| Tuscon | GRU | 12 | 144.3524 | 40,552.5880 | 196.8997 | 0.8672 | 10.7675 |

| Tuscon | GRU | 24 | 154.2250 | 46,671.1455 | 210.8856 | 0.8487 | 11.4220 |

| Tuscon | LSTM | 1 | 95.3716 | 17,112.9011 | 129.1712 | 0.9410 | 7.3249 |

| Tuscon | LSTM | 6 | 131.3315 | 34,284.5924 | 181.1381 | 0.8869 | 9.7986 |

| Tuscon | LSTM | 12 | 137.9481 | 37,677.9076 | 189.3717 | 0.8763 | 10.3284 |

| Tuscon | LSTM | 24 | 154.9230 | 47,436.7154 | 211.5773 | 0.8483 | 11.7839 |

| Tuscon | Prophet | 1 | 35.0289 | 1912.2606 | 43.7294 | 0.9774 | 2.3130 |

| Tuscon | Prophet | 6 | 42.9949 | 2898.2210 | 53.8351 | 0.8957 | 2.8304 |

| Tuscon | Prophet | 12 | 70.5490 | 6553.7843 | 80.9554 | 0.9845 | 4.8086 |

| Tuscon | Prophet | 24 | 22.6890 | 743.4698 | 27.2666 | 0.9928 | 1.4463 |

| Tuscon | TCN | 1 | 92.0281 | 16,159.7710 | 125.2435 | 0.9429 | 6.9088 |

| Tuscon | TCN | 6 | 136.5746 | 37,891.2820 | 189.2369 | 0.8769 | 10.2769 |

| Tuscon | TCN | 12 | 138.4448 | 39,060.6096 | 192.5174 | 0.8733 | 10.2012 |

| Tuscon | TCN | 24 | 154.4451 | 47,055.4719 | 211.3072 | 0.8442 | 11.6041 |

| Philadelphia | GRU | 1 | 107.6625 | 20,894.6098 | 143.9300 | 0.9744 | 2.4104 |

| Philadelphia | GRU | 6 | 169.9049 | 60,706.0674 | 246.1511 | 0.9260 | 3.7399 |

| Philadelphia | GRU | 12 | 220.8261 | 100,301.2897 | 316.0880 | 0.8779 | 4.8669 |

| Philadelphia | GRU | 24 | 272.3402 | 147,989.8930 | 384.2691 | 0.8197 | 6.0290 |

| Philadelphia | LSTM | 1 | 108.4771 | 20,616.1893 | 143.1624 | 0.9750 | 2.4505 |

| Philadelphia | LSTM | 6 | 181.0643 | 64,005.3140 | 252.5125 | 0.9221 | 4.0411 |

| Philadelphia | LSTM | 12 | 229.6147 | 102,740.1984 | 319.8449 | 0.8751 | 5.1070 |

| Philadelphia | LSTM | 24 | 277.3656 | 147,255.3639 | 382.5679 | 0.8212 | 6.1326 |

| Philadelphia | Prophet | 1 | 32.0178 | 1649.9959 | 40.6201 | 0.9949 | 0.7985 |

| Philadelphia | Prophet | 6 | 58.3972 | 4684.2804 | 68.4418 | 0.9859 | 1.5030 |

| Philadelphia | Prophet | 12 | 48.0936 | 3141.3585 | 56.0478 | 0.9923 | 0.9416 |

| Philadelphia | Prophet | 24 | 15.7171 | 457.4517 | 21.3881 | 0.9988 | 0.3667 |

| Philadelphia | TCN | 1 | 86.9800 | 14,196.7247 | 118.8997 | 0.9827 | 1.9425 |

| Philadelphia | TCN | 6 | 168.9979 | 58,352.8073 | 241.1798 | 0.9290 | 3.7529 |

| Philadelphia | TCN | 12 | 216.7416 | 94,044.5152 | 306.3122 | 0.8855 | 4.7832 |

| Philadelphia | TCN | 24 | 261.9680 | 134,265.0427 | 365.7485 | 0.8367 | 5.7712 |

| San Antonio | GRU | 1 | 203.7131 | 74,011.9930 | 271.9686 | 0.9804 | 2.6793 |

| San Antonio | GRU | 6 | 358.7291 | 260,185.1058 | 509.9413 | 0.9311 | 4.7560 |

| San Antonio | GRU | 12 | 463.8332 | 434,166.9088 | 658.3510 | 0.8847 | 6.1599 |

| San Antonio | GRU | 24 | 539.2059 | 579,395.5928 | 760.4961 | 0.8470 | 7.1010 |

| San Antonio | LSTM | 1 | 243.6161 | 102,469.5116 | 319.4890 | 0.9731 | 3.2746 |

| San Antonio | LSTM | 6 | 411.2620 | 324,088.5075 | 567.9070 | 0.9152 | 5.4366 |

| San Antonio | LSTM | 12 | 493.8181 | 462,247.9877 | 679.3595 | 0.8777 | 6.6202 |

| San Antonio | LSTM | 24 | 546.5051 | 586,885.8201 | 765.8046 | 0.8445 | 7.3336 |

| San Antonio | Prophet | 1 | 56.3815 | 7466.8278 | 86.4108 | 0.9974 | 0.8132 |

| San Antonio | Prophet | 6 | 57.2207 | 6580.8084 | 81.1222 | 0.9974 | 0.8355 |

| San Antonio | Prophet | 12 | 51.2221 | 5164.3676 | 71.8635 | 0.9981 | 0.5644 |

| San Antonio | Prophet | 24 | 66.4882 | 5960.0176 | 77.2011 | 0.9981 | 0.8230 |

| San Antonio | TCN | 1 | 201.4780 | 73,713.4719 | 270.8027 | 0.9803 | 2.6872 |

| San Antonio | TCN | 6 | 383.0537 | 296,180.6270 | 543.9936 | 0.9211 | 5.1432 |

| San Antonio | TCN | 12 | 463.7172 | 446,544.7699 | 668.1436 | 0.8815 | 6.2405 |

| San Antonio | TCN | 24 | 527.9993 | 567,517.8416 | 753.1219 | 0.8486 | 7.1410 |

| Portland | GRU | 1 | 62.3686 | 12,343.0811 | 105.5942 | 0.9363 | 2.5682 |

| Portland | GRU | 6 | 90.4112 | 20,637.1185 | 140.9087 | 0.8912 | 3.6696 |

| Portland | GRU | 12 | 104.7859 | 25,089.9987 | 155.6000 | 0.8677 | 4.3240 |

| Portland | GRU | 24 | 116.4490 | 31,548.7418 | 175.9969 | 0.8321 | 4.6856 |

| Portland | LSTM | 1 | 77.5571 | 17,319.8427 | 125.7055 | 0.9098 | 3.2161 |

| Portland | LSTM | 6 | 96.6631 | 22,733.9227 | 148.0422 | 0.8798 | 3.9064 |

| Portland | LSTM | 12 | 107.1362 | 26,553.7377 | 160.3489 | 0.8593 | 4.3873 |

| Portland | LSTM | 24 | 127.6451 | 36,781.5590 | 189.8350 | 0.8042 | 5.2175 |

| Portland | Prophet | 1 | 33.8610 | 1595.3917 | 39.9424 | 0.9692 | 1.5143 |

| Portland | Prophet | 6 | 55.6203 | 4078.2462 | 63.8611 | 0.9613 | 2.5806 |

| Portland | Prophet | 12 | 42.2922 | 2496.8768 | 49.9688 | 0.9629 | 1.5736 |

| Portland | Prophet | 24 | 46.9483 | 4574.7738 | 67.6371 | 0.8842 | 2.0022 |

| Portland | TCN | 1 | 86.5217 | 21,652.2050 | 139.9918 | 0.8883 | 3.5602 |

| Portland | TCN | 6 | 111.8787 | 30,203.0069 | 169.4401 | 0.8422 | 4.5172 |

| Portland | TCN | 12 | 133.7980 | 38,914.5441 | 190.7458 | 0.7977 | 5.6347 |

| Portland | TCN | 24 | 133.2291 | 39,629.4233 | 196.5195 | 0.7903 | 5.4446 |

| Los Angeles | GRU | 1 | 284.3712 | 154,206.1317 | 388.3336 | 0.9755 | 2.4735 |

| Los Angeles | GRU | 6 | 416.7433 | 355,133.6235 | 593.5011 | 0.9438 | 3.5483 |

| Los Angeles | GRU | 12 | 476.3850 | 440,366.5809 | 661.0175 | 0.9306 | 4.1065 |

| Los Angeles | GRU | 24 | 506.8041 | 527,929.6993 | 722.7685 | 0.9176 | 4.3072 |

| Los Angeles | LSTM | 1 | 316.6008 | 178,070.7432 | 419.5036 | 0.9712 | 2.8143 |

| Los Angeles | LSTM | 6 | 428.6626 | 356,605.6034 | 595.2330 | 0.9437 | 3.7140 |

| Los Angeles | LSTM | 12 | 467.6323 | 428,820.1693 | 652.0172 | 0.9325 | 4.0293 |

| Los Angeles | LSTM | 24 | 519.7834 | 549,017.1206 | 737.0816 | 0.9141 | 4.4519 |

| Los Angeles | Prophet | 1 | 91.5062 | 12,684.2843 | 112.6245 | 0.9911 | 0.8561 |

| Los Angeles | Prophet | 6 | 235.5114 | 77,605.6645 | 278.5779 | 0.8357 | 2.2544 |

| Los Angeles | Prophet | 12 | 196.8646 | 45,301.8665 | 212.8424 | 0.9912 | 1.6746 |

| Los Angeles | Prophet | 24 | 95.2982 | 24,106.6388 | 155.2631 | 0.9871 | 0.9529 |

| Los Angeles | TCN | 1 | 279.7668 | 138,702.0973 | 370.6171 | 0.9771 | 2.4671 |

| Los Angeles | TCN | 6 | 427.8595 | 376,380.2749 | 609.4956 | 0.9406 | 3.6784 |

| Los Angeles | TCN | 12 | 442.1358 | 409,148.5964 | 638.3442 | 0.9356 | 3.7473 |

| Los Angeles | TCN | 24 | 485.9583 | 500,411.1493 | 705.4569 | 0.9216 | 4.1022 |

| New York City | GRU | 1 | 156.4994 | 78,352.6758 | 239.2255 | 0.9528 | 2.6875 |

| New York City | GRU | 6 | 219.9790 | 127,878.0057 | 327.3027 | 0.9182 | 3.7550 |

| New York City | GRU | 12 | 282.8775 | 185,053.9870 | 407.2325 | 0.8770 | 4.8511 |

| New York City | GRU | 24 | 339.1639 | 250,319.9588 | 481.4327 | 0.8291 | 5.8022 |

| New York City | LSTM | 1 | 158.4971 | 45,486.2243 | 208.8116 | 0.9677 | 2.8190 |

| New York City | LSTM | 6 | 227.8100 | 101,044.1728 | 309.7714 | 0.9296 | 3.9662 |

| New York City | LSTM | 12 | 300.4532 | 175,351.2818 | 410.1478 | 0.8768 | 5.2054 |

| New York City | LSTM | 24 | 357.7402 | 247,874.9332 | 489.7387 | 0.8237 | 6.2788 |

| New York City | Prophet | 1 | 35.9358 | 2109.5295 | 45.9296 | 0.9960 | 0.6409 |

| New York City | Prophet | 6 | 70.8589 | 8465.3295 | 92.0072 | 0.9708 | 1.3635 |

| New York City | Prophet | 12 | 56.8691 | 5176.1957 | 71.9458 | 0.9936 | 0.8446 |

| New York City | Prophet | 24 | 38.5904 | 2356.4184 | 48.5430 | 0.9968 | 0.6857 |

| New York City | TCN | 1 | 114.6655 | 29,430.5004 | 162.7515 | 0.9803 | 2.0017 |

| New York City | TCN | 6 | 219.3952 | 134,029.3786 | 332.4096 | 0.9148 | 3.7460 |

| New York City | TCN | 12 | 274.5975 | 207,097.1027 | 420.1442 | 0.8662 | 4.6773 |

| New York City | TCN | 24 | 316.4043 | 224,683.7379 | 459.2551 | 0.8446 | 5.4101 |

| Omaha | GRU | 1 | 23.2177 | 876.2771 | 28.7292 | −0.0190 | 2.4699 |

| Omaha | GRU | 6 | 24.0404 | 947.4238 | 29.7480 | −1.1042 | 2.5632 |

| Omaha | GRU | 12 | 24.8248 | 1017.6050 | 30.9657 | −1.2297 | 2.6464 |

| Omaha | GRU | 24 | 24.4959 | 965.9364 | 30.2452 | −1.1628 | 2.6053 |

| Omaha | LSTM | 1 | 203.8283 | 811,324.9597 | 601.6454 | 0.0556 | 14.2714 |

| Omaha | LSTM | 6 | 221.6740 | 823,106.6493 | 615.1799 | −1.0197 | 15.6610 |

| Omaha | LSTM | 12 | 245.3685 | 832,964.0885 | 625.9563 | −1.0837 | 17.3301 |

| Omaha | LSTM | 24 | 210.6698 | 814,033.9343 | 607.2106 | 0.0405 | 14.4560 |

| Omaha | Prophet | 1 | 63.6864 | 13,795.3933 | 117.4538 | 0.7053 | 3.7328 |

| Omaha | Prophet | 6 | 45.3570 | 9021.7771 | 94.9830 | 0.6615 | 3.2103 |

| Omaha | Prophet | 12 | 47.5934 | 5372.0037 | 73.2940 | 0.9285 | 2.6613 |

| Omaha | Prophet | 24 | 41.3096 | 3839.0935 | 61.9604 | 0.9388 | 2.4913 |

| Omaha | TCN | 1 | 170.7902 | 1,291,635.6565 | 664.7587 | 0.2160 | 11.7918 |

| Omaha | TCN | 6 | 171.1089 | 1,392,047.5211 | 689.6581 | 0.1591 | 11.9326 |

| Omaha | TCN | 12 | 204.5854 | 1,312,614.1613 | 682.7986 | 0.1479 | 14.2650 |

| Omaha | TCN | 24 | 217.2904 | 1,118,488.3941 | 663.4458 | 0.0339 | 15.4355 |

| Tampa | GRU | 1 | 81.2304 | 11,844.6583 | 108.1844 | 0.9718 | 3.3570 |

| Tampa | GRU | 6 | 132.2254 | 34,859.3461 | 185.7429 | 0.9180 | 5.2682 |

| Tampa | GRU | 12 | 156.5541 | 47,501.9739 | 217.0320 | 0.8883 | 6.3090 |

| Tampa | GRU | 24 | 178.9941 | 62,426.8019 | 248.0483 | 0.8535 | 7.3254 |

| Tampa | LSTM | 1 | 90.7195 | 14,509.2779 | 120.1392 | 0.9656 | 3.7922 |

| Tampa | LSTM | 6 | 148.0406 | 42,019.8347 | 204.5557 | 0.9011 | 5.9564 |

| Tampa | LSTM | 12 | 173.1308 | 55,454.0895 | 234.6291 | 0.8694 | 7.1790 |

| Tampa | LSTM | 24 | 186.9419 | 66,433.4134 | 256.6485 | 0.8441 | 7.7130 |

| Tampa | Prophet | 1 | 15.0019 | 371.0215 | 19.2619 | 0.9972 | 0.7445 |

| Tampa | Prophet | 6 | 25.2020 | 822.6153 | 28.6813 | 0.9857 | 1.2935 |

| Tampa | Prophet | 12 | 39.6706 | 3546.2440 | 59.5503 | 0.9858 | 1.3388 |

| Tampa | Prophet | 24 | 22.9832 | 704.9305 | 26.5505 | 0.9968 | 1.0227 |

| Tampa | TCN | 1 | 68.7455 | 9001.8871 | 94.3470 | 0.9784 | 2.8069 |

| Tampa | TCN | 6 | 119.1644 | 28,724.9426 | 169.2677 | 0.9328 | 4.7538 |

| Tampa | TCN | 12 | 140.5849 | 38,396.9949 | 195.7796 | 0.9100 | 5.6751 |

| Tampa | TCN | 24 | 152.9676 | 46,308.3699 | 214.9841 | 0.8915 | 6.2396 |

Appendix C. Hierarchical Clustering of Climate Variable Variability

| City | Temperature | Dew Point | Relative Humidity | Precipitation | Wind Speed | Pressure | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Houston | 0.348 | 0.417 | 0.271 | 8.955 | 0.600 | 0.005 | 1 |

| Los Angeles | 0.280 | 0.390 | 0.311 | 9.190 | 1.254 | 0.004 | 1 |

| San Antonio | 0.384 | 0.434 | 0.338 | 8.521 | 0.645 | 0.006 | 1 |

| San Diego | 0.243 | 0.369 | 0.228 | 9.300 | 0.741 | 0.004 | 1 |

| Tallahassee | 0.363 | 0.419 | 0.269 | 8.813 | 0.816 | 0.005 | 1 |

| Tampa | 0.239 | 0.307 | 0.234 | 8.295 | 0.669 | 0.004 | 1 |

| Baltimore | 0.551 | 0.559 | 0.298 | 6.757 | 0.612 | 0.007 | 2 |

| Chicago | 0.631 | 0.607 | 0.265 | 6.465 | 0.516 | 0.007 | 2 |

| Omaha | 0.597 | 0.570 | 0.281 | 8.123 | 0.604 | 0.008 | 2 |

| Philadelphia | 0.575 | 0.562 | 0.313 | 6.796 | 0.604 | 0.007 | 2 |

| Portland | 0.550 | 0.563 | 0.265 | 3.815 | 0.741 | 0.007 | 2 |

| Seattle | 0.537 | 0.546 | 0.239 | 4.200 | 0.789 | 0.007 | 2 |

| El Paso | 0.470 | 0.603 | 0.585 | 16.364 | 0.719 | 0.006 | 3 |

| New York City | 0.575 | 0.573 | 0.276 | 19.025 | 0.626 | 0.008 | 3 |

| Tucson | 0.440 | 0.704 | 0.620 | 12.605 | 0.629 | 0.005 | 3 |

References

- UN-Habitat. Urban Energy. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/topic/urban-energy (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- UN-HABITAT. Envisaging the Future of Cities; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Madlener, R.; Sunak, Y. Impacts of urbanization on urban structures and energy demand: What can we learn for urban energy planning and urbanization management? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2011, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment Programme. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction; Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Energy Efficiency 2024; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Manohar, V.J.; Murthy, G.; Royal, N.P.; Binu, B.; Patil, T. Comprehensive Analysis of Energy Demand Prediction Using Advanced Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Casablanca, Morocco, 4–5 December 2025; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2025; Volume 616, p. 02027. [Google Scholar]

- Durmus Senyapar, H.N.; Aksoz, A. Empowering sustainability: A consumer-centric analysis based on advanced electricity consumption predictions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joskow, P.L. Creating a smarter US electricity grid. J. Econ. Perspect. 2012, 26, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Cox, E.; Loughhead, J.; Roberts, J. Counting the Cost: The Economic and Social Costs of Electricity Shortfalls in the UK-A Report for the Council for Science and Technology 2014. Available online: https://www.raeng.org.uk/media/2s2pgeeg/single-pages-counting-the-cost-report.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ward, C.; Robinson, C.; Singleton, A.; Rowe, F. Spatial-Temporal Dynamics of Gas Consumption in England and Wales: Assessing the Residential Sector Using Sequence Analysis. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2024, 17, 1273–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayindir, R.; Irmak, E.; Colak, I.; Bektas, A. Development of a real time energy monitoring platform. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2011, 33, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayindir, R.; Hossain, E.; Kabalci, E.; Billah, K.M.M. Investigation on North American microgrid facility. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2015, 5, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, J.S. A new hybrid method for China’s energy supply security forecasting based on ARIMA and XGBoost. Energies 2018, 11, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C40. 2021. 700+ Cities in 53 Countries Now Committed to Halve Emissions by 2030 and Reach Net Zero by 2050. Available online: https://www.c40.org/news/cities-committed-race-to-zero/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Hou, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Wu, X.; Tang, J.; Shi, Y.; Xie, C. Review of load forecasting based on artificial intelligence methodologies, models, and challenges. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 210, 108067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, M.; Wang, J. Deep learning-based feature engineering methods for improved building energy prediction. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Madonski, R.; Zhang, D.; Huang, C.; Mujeeb, A. Data-driven probabilistic machine learning in sustainable smart energy/smart energy systems: Key developments, challenges, and future research opportunities in the context of smart grid paradigm. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y.; Ghanem, K.; Alsalemi, A.; Bensaali, F.; Amira, A. Artificial intelligence based anomaly detection of energy consumption in buildings: A review, current trends and new perspectives. Appl. Energy 2021, 287, 116601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, S.; Choi, J.K.; Hong, T. Predicting industrial building energy consumption with statistical and machine-learning models informed by physical system parameters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 172, 113045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Nepal, M.; Thanh, K.N.; Dur, F. A novel urban heat vulnerability analysis: Integrating machine learning and remote sensing for enhanced insights. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, C.; Jain, A.; Barwaria, P.; Choudhary, A.; Singh, A.; Gupta, A.; Seth, A. Temporal prediction of socio-economic indicators using satellite imagery. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM IKDD CoDS and 25th COMAD, Hyderabad, India, 5–7 January 2020; pp. 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kiasari, M.; Ghaffari, M.; Aly, H.H. A Comprehensive Review of the Current Status of Smart Grid Technologies for Renewable Energies Integration and Future Trends: The Role of Machine Learning and Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, R.; Srinivasan, R.S.; Ahrentzen, S. Random Forest based hourly building energy prediction. Energy Build. 2018, 171, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, R.; Patne, N.R.; Pemmada, S.; Manchalwar, A.D. Regression model-based hourly aggregated electricity demand prediction. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, D.; Yi, J.; Zhang, G. Building energy consumption prediction: An extreme deep learning approach. Energies 2017, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tarhuni, B.; Naji, A.; Brodrick, P.G.; Hallinan, K.P.; Brecha, R.J.; Yao, Z. Large scale residential energy efficiency prioritization enabled by machine learning. Energy Effic. 2019, 12, 2055–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Xing, K.; Zhang, H. Artificial neural network for assessment of energy consumption and cost for cross laminated timber office building in severe cold regions. Sustainability 2017, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontokosta, C.E.; Tull, C. A data-driven predictive model of city-scale energy use in buildings. Appl. Energy 2017, 197, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ding, L.; Lv, J.; Xu, G.; Li, J. A novel hybrid approach of KPCA and SVM for building cooling load prediction. In Proceedings of the 2010 Third International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Online, 9–10 January 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 522–526. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Li, X.; Ding, L.; Jiang, L. Applying principal component analysis and weighted support vector machine in building cooling load forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Computer and Communication Technologies in Agriculture Engineering, Nanchang, China, 22–25 October 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 434–437. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Meng, Q.; Cai, J.; Yoshino, H.; Mochida, A. Applying support vector machine to predict hourly cooling load in the building. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VE, S.; Shin, C.; Cho, Y. Efficient energy consumption prediction model for a data analytic-enabled industry building in a smart city. Build. Res. Inf. 2021, 49, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J.; Weigold, M. A systematic review on predicting and forecasting the electrical energy consumption in the manufacturing industry. Energies 2021, 14, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Ding, L.; Jiang, L. Building cooling load forecasting using fuzzy support vector machine and fuzzy C-mean clustering. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Computer and Communication Technologies in Agriculture Engineering, Nanchang, China, 22–25 October 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 438–441. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, D.M.; Winter, R.L.; Boulanger, A.G.; Anderson, R.N.; Wu, L.L. Forecasting Energy Demand in Large Commercial Buildings Using Support Vector Machine Regression; Columbia University Computer Science Technical Reports, CUCS-040-11; Department of Computer Science, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R.E.; New, J.; Parker, L.E. Predicting future hourly residential electrical consumption: A machine learning case study. Energy Build. 2012, 49, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.C.; Wan, K.K.; Wong, S.; Lam, T.N. Principal component analysis and long-term building energy simulation correlation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzana, S.; Liu, M.; Baldwin, A.; Hossain, M.U. Multi-model prediction and simulation of residential building energy in urban areas of Chongqing, South West China. Energy Build. 2014, 81, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnely, P.; Ruette, T.; Tourwé, T.; Tsiporkova, E.; Verhelst, C. Predicting hourly energy consumption. Can you beat an autoregressive model. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Machine Learning Conference of Belgium and The Netherlands, Benelearn, Delft, The Netherlands, 18–20 November 2015; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Nakhi, A.E.; Mahmoud, M.A. Cooling load prediction for buildings using general regression neural networks. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 2127–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumo, N.; Biswas, M.R. Regression analysis for prediction of residential energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.; Ozturk, F. Forecasting energy consumption of Turkey by Arima model. J. Asian Sci. Res. 2018, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediger, V.Ş.; Akar, S. ARIMA forecasting of primary energy demand by fuel in Turkey. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathumitha, R.; Rathika, P.; Manimala, K. Intelligent deep learning techniques for energy consumption forecasting in smart buildings: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. Seasonal decomposition of electricity consumption data. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 6, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Mbasso, W.F.; Molu, R.J.J.; Harrison, A.; Pushkarna, M.; Kemdoum, F.N.; Donfack, E.F.; Jangir, P.; Tiako, P.; Tuka, M.B. Hybrid modeling approach for precise estimation of energy production and consumption based on temperature variations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.F.; Zhang, L.Z.; Yu, M.; Hong, W.C.; Dong, S.Q. Applications of random forest in multivariable response surface for short-term load forecasting. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 139, 108073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candanedo, L.M.; Feldheim, V.; Deramaix, D. Data driven prediction models of energy use of appliances in a low-energy house. Energy Build. 2017, 140, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.W.; Mourshed, M.; Rezgui, Y. Trees vs. Neurons: Comparison between random forest and ANN for high-resolution prediction of building energy consumption. Energy Build. 2017, 147, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, I.; Sahu, S.; Kumar, R.; Taniar, D. A machine-learning ensemble model for predicting energy consumption in smart homes. Internet Things 2022, 20, 100636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divina, F.; Gilson, A.; Goméz-Vela, F.; García Torres, M.; Torres, J.F. Stacking ensemble learning for short-term electricity consumption forecasting. Energies 2018, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashei, M.; Bijari, M. A novel hybridization of artificial neural networks and ARIMA models for time series forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 2664–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadegan, H.; Rashidi Malki, B.; Radmehr, A.; Karimi, H.; Ilani, M.A. Comparative study of long short-term memory (LSTM), bidirectional LSTM, and traditional machine learning approaches for energy consumption prediction. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2025, 43, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterakis, N.G.; Mocanu, E.; Gibescu, M.; Stappers, B.; van Alst, W. Deep learning versus traditional machine learning methods for aggregated energy demand prediction. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), Torino, Italy, 26–29 September 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hrnjica, B.; Mehr, A.D. Energy demand forecasting using deep learning. In Smart Cities Performability, Cognition, & Security; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi, J.; Toshniwal, D. Deep learning framework to forecast electricity demand. Appl. Energy 2019, 238, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, S.; Keivani, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Alengaram, U.J.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Mansor, Z.; Lee, M. Estimating building energy consumption using extreme learning machine method. Energy 2016, 97, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zio, E.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z. A hybrid hourly natural gas demand forecasting method based on the integration of wavelet transform and enhanced Deep-RNN model. Energy 2019, 178, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karijadi, I.; Chou, S.Y. A hybrid RF-LSTM based on CEEMDAN for improving the accuracy of building energy consumption prediction. Energy Build. 2022, 259, 111908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Real, A.J.; Dorado, F.; Durán, J. Energy demand forecasting using deep learning: Applications for the French grid. Energies 2020, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Cho, S.B. Predicting residential energy consumption using CNN-LSTM neural networks. Energy 2019, 182, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasyali, K.; El-Gohary, N. Deep learning for building energy consumption prediction. In Proceedings of the 6th CSCE-CRC International Construction Specialty Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 31 May–3 June 2017; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Cawthorne, D.; de Queiroz, A.R.; Eshraghi, H.; Sankarasubramanian, A.; DeCarolis, J.F. The role of temperature variability on seasonal electricity demand in the Southern US. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 644789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.U.M.; Ullah, A.; Khan, N.; Lee, M.Y.; Rho, S.; Baik, S.W. Deep Learning-Assisted Short-Term Power Load Forecasting Using Deep Convolutional LSTM and Stacked GRU. Complexity 2022, 2022, 2993184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduailij, M.A.; Petri, I.; Rana, O.; Alduailij, M.A.; Aldawood, A.S. Forecasting peak energy demand for smart buildings. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 6356–6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, B.; Yamaha, M.; Yokoe, A.; Yamaji, T. Electricity load forecasting using clustering and ARIMA model for energy management in buildings. Jpn. Archit. Rev. 2020, 3, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Dhyani, B.; chauhan, A.; Sayal, A. ARIMA based forecasting of solar and hydro energy consumption with implications for grid stability and renewable policy. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, B.; Bento, P.; Pombo, J.; Calado, M.d.R.; Mariano, S. Short-term load forecasting based on optimized random forest and optimal feature selection. Energies 2024, 17, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Dong, X.; Tao, L.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Yue, D. Multi-type load forecasting model based on random forest and density clustering with the influence of noise and load patterns. Energy 2024, 307, 132635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, S.; Anisi, M.H.; Kama, N.; Doctor, F.; Soleymani, S.A.; Sangaiah, A.K. Predictive modelling of building energy consumption based on a hybrid nature-inspired optimization algorithm. Energy Build. 2019, 196, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izudin, N.E.M.; Sokkalingam, R.; Daud, H.; Mardesci, H.; Husin, A. Forecasting electricity consumption in Malaysia by hybrid ARIMA-ANN. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Fundamental and Applied Sciences: ICFAS 2020, Sarawak, Malaysia, 14–16 July 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 749–760. [Google Scholar]

- Souhe, F.G.Y.; Mbey, C.F.; Boum, A.T.; Ele, P.; Kakeu, V.J.F. A hybrid model for forecasting the consumption of electrical energy in a smart grid. J. Eng. 2022, 2022, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumohsen, M.; Owda, A.Y.; Owda, M. Electrical load forecasting using LSTM, GRU, and RNN algorithms. Energies 2023, 16, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Hussain, T.; Ullah, A.; Rho, S.; Lee, M.; Baik, S.W. Towards efficient electricity forecasting in residential and commercial buildings: A novel hybrid CNN with a LSTM-AE based framework. Sensors 2020, 20, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, W.; Song, Q.; Li, X. Load forecasting method based on CNN and extended LSTM. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 2452–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carréon, J.R.; Worrell, E. Urban energy systems within the transition to sustainable development. A research agenda for urban metabolism. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Fu, C.; Xu, P. Energy shock, industrial transformation and macroeconomic fluctuations. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 92, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wan, K.; Song, X.; Liu, Y. Comparing the vulnerability of different coal industrial symbiosis networks under economic fluctuations. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffell, I.; Pfenninger, S. The increasing impact of weather on electricity supply and demand. Energy 2018, 145, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, H.; Núñez-Peiró, M.; Sánchez-Guevara, C.; Neila, J. On the identification of Homogeneous Urban Zones for the residential buildings’ energy evaluation. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Real-Time Operating Grid-U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Available online: https://toolkit.climate.gov/tool/us-electric-system-real-time-operating-grid (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Meteostat. Available online: https://meteostat.net/en/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Fan, C.; Xiao, F.; Wang, S. Development of prediction models for next-day building energy consumption and peak power demand using data mining techniques. Appl. Energy 2014, 127, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, J.; Azam, R.; Rifa, A.A.; Rana, M.J. Multiple machine learning models for predicting annual energy consumption and demand of office buildings in subtropical monsoon climate. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 26, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.K.; Kumar, A.; García-Díaz, V.; Sharma, A.K.; Kanhaiya, K. Study and analysis of SARIMA and LSTM in forecasting time series data. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2021, 47, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ruan, Y. Interpretable deep learning model for building energy consumption prediction based on attention mechanism. Energy Build. 2021, 252, 111379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Analyzing the heat island magnitude and characteristics in one hundred Asian and Australian cities and regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 512, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, H. Urban climates and heat islands: Albedo, evapotranspiration, and anthropogenic heat. Energy Build. 1997, 25, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Cooling the cities–A review of reflective and green roof mitigation technologies to fight heat island and improve comfort in urban environments. Sol. Energy 2014, 103, 682–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bou-Zeid, E. Should cities embrace their heat islands as shields from extreme cold? J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2019, 58, 1307–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, D. Urban density and climate change. In Analytical Review of the Interaction Between Urban Growth Trends and Environmental Changes; United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA): New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Steemers, K. Energy and the city: Density, buildings and transport. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, F.; Amado, M. The spatial dimension of energy consumption in cities. Energy Policy 2024, 187, 114023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, M.; Bussolino, B.; Marchisio, A.; Masera, G.; Martina, M.; Shafique, M. Hardware and software optimizations for accelerating deep neural networks: Survey of current trends, challenges, and the road ahead. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 225134–225180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Letham, B. Forecasting at scale. Am. Stat. 2018, 72, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chengbo, Y.; Tao, L. Prophet-Based Medium and Long-Term Electricity Load Forecasting Research. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2356, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S. A hybrid forecasting model using LSTM and Prophet for energy consumption with decomposition of time series data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Fang, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, X. Using long short-term memory networks to predict energy consumption of air-conditioning systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munem, M.; Bashar, T.R.; Roni, M.H.; Shahriar, M.; Shawkat, T.B.; Rahaman, H. Electric power load forecasting based on multivariate LSTM neural network using Bayesian optimization. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Electric Power and Energy Conference, Virtual, 7–8 December 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.; Dong, Z.Y.; Jia, Y.; Hill, D.J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Short-term residential load forecasting based on LSTM recurrent neural network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 10, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, F.M.; Salem, F.M. Gated RNN: The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) RNN. In Recurrent Neural Networks: From Simple to Gated Architectures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, C.; Flynn, M.D.; Vidal, R.; Reiter, A.; Hager, G.D. Temporal convolutional networks for action segmentation and detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.K.; Nazir, A.; Khalique, N.; Shah, A.S.; Adhikari, N. A new approach to seasonal energy consumption forecasting using temporal convolutional networks. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zou, W.; Zhao, X. Hybrid Time Series Forecasting for Real-Time Electricity Market Demand Using ARIMA-LSTM and Scalable Cloud-Native Architecture. Informatica 2025, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeir, C.; Hyndman, R.J.; Koo, B. A note on the validity of cross-validation for evaluating autoregressive time series prediction. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2018, 120, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, R.; Jia, X.; Su, X.; Xu, Q.; Ning, H.; Zhang, J. Ai-driven multi-objective optimization and decision-making for urban building energy retrofit: Advances, challenges, and systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Oakland, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1965 and 27 December 1965–7 January 1966; Volume 1, pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Conover, W.J. Practical Nonparametric Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; Volume 350. [Google Scholar]

- Himeur, Y.; Alsalemi, A.; Bensaali, F.; Amira, A.; Al-Kababji, A. Recent trends of smart nonintrusive load monitoring in buildings: A review, open challenges, and future directions. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 7124–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, J.; Toshniwal, D. Empirical mode decomposition based deep learning for electricity demand forecasting. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 49144–49156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochi, P. Perspective on challenges and opportunities in integrated electricity-hydrogen market. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 87, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Type | Methods | Key Assumptions | Forecast Horizon | Advantages (+) and Limitations (–) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical models (e.g., [41,43,65,66,67]) | MLR, ARIMA, SARIMA | Linear relationships; stationarity | Daily–monthly | + Interpretable; low computational cost – Performs poorly under non-linearity and high variability |

| ML models (e.g., [47,48,68,69]) | RF, SVR, DT | Feature-driven relationships | Hourly–daily | + Strong non-linear modelling; moderate complexity – Limited temporal memory; typically building-scale |

| Hybrid models (e.g., [51,52,70,71,72]) | ANN–ARIMA; ensemble learners; ARIMA–SVR–PSO; ARIMA–ANN; SVR–FA–ANFIS | Combined linear & non-linear structure | Short-term (hourly) | + Improved accuracy and robustness – High complexity; reduced interpretability |

| Deep learning (e.g., [55,56,64,73,74]) | LSTM, GRU, CNN, Bi-LSTM, RNN, CNN–LSTM–AE, LSTM–GRU | Require large training datasets | 1–6 h (typically) | + Excellent short-term accuracy; captures non-linear temporal dynamics – Data-intensive; weaker long-horizon stability |

| Spatio-temporal DL (e.g., [61,62,75]) | CNN–LSTM, DNN | Dense spatial sensing; spatial–temporal dependency | Short-term | + Captures spatial relationships and temporal patterns – Limited scalability; high data and compute demand |

| Cluster | Model | Horizon | MAE | MSE | RMSE | R2 | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | GRU | 1 | 139.09 | 46,987.36 | 193.97 | 0.971 | 2.58 |

| GRU | 6 | 230.04 | 127,309.73 | 331.97 | 0.918 | 4.26 | |

| GRU | 12 | 295.99 | 203,085.27 | 421.25 | 0.870 | 5.47 | |

| GRU | 24 | 351.28 | 275,144.62 | 493.93 | 0.821 | 6.52 | |

| LSTM | 1 | 152.93 | 46,617.66 | 201.27 | 0.971 | 2.87 | |

| LSTM | 6 | 251.27 | 138,600.17 | 346.26 | 0.913 | 4.67 | |

| LSTM | 12 | 311.80 | 209,038.65 | 429.53 | 0.866 | 5.80 | |

| LSTM | 24 | 361.80 | 277,865.37 | 499.23 | 0.817 | 6.81 | |

| Prophet | 1 | 35.30 | 2934.39 | 48.89 | 0.997 | 0.69 | |

| Prophet | 6 | 55.86 | 5499.54 | 72.30 | 0.988 | 1.23 | |

| Prophet | 12 | 53.85 | 4499.18 | 66.76 | 0.993 | 0.96 | |

| Prophet | 24 | 33.21 | 2242.40 | 40.28 | 0.998 | 0.55 | |

| TCN | 1 | 125.09 | 33,721.42 | 170.99 | 0.978 | 2.34 | |

| TCN | 6 | 238.82 | 139,109.18 | 344.28 | 0.912 | 4.46 | |

| TCN | 12 | 294.05 | 211,262.02 | 426.42 | 0.866 | 5.47 | |

| TCN | 24 | 341.08 | 263,134.79 | 483.13 | 0.828 | 6.39 | |

| Cluster 2 | GRU | 1 | 348.14 | 432,498.51 | 559.62 | 0.925 | 3.15 |

| GRU | 6 | 469.76 | 652,785.47 | 747.14 | 0.883 | 4.14 | |

| GRU | 12 | 561.24 | 828,605.79 | 853.92 | 0.848 | 4.98 | |

| GRU | 24 | 628.74 | 1,010,078.46 | 949.39 | 0.813 | 5.56 | |

| LSTM | 1 | 356.43 | 484,163.96 | 590.96 | 0.916 | 3.21 | |

| LSTM | 6 | 485.32 | 714,935.35 | 772.63 | 0.873 | 4.29 | |

| LSTM | 12 | 560.06 | 821,169.87 | 850.88 | 0.849 | 4.98 | |

| LSTM | 24 | 631.95 | 1,049,037.26 | 967.88 | 0.805 | 5.57 | |

| Prophet | 1 | 153.97 | 38,863.87 | 183.83 | 0.979 | 1.41 | |

| Prophet | 6 | 268.83 | 90,065.09 | 299.39 | 0.865 | 2.76 | |

| Prophet | 12 | 288.82 | 143,068.67 | 351.80 | 0.968 | 2.25 | |

| Prophet | 24 | 162.72 | 74,651.62 | 254.55 | 0.979 | 1.36 | |

| TCN | 1 | 384.60 | 661,896.47 | 640.91 | 0.886 | 3.51 | |

| TCN | 6 | 541.12 | 960,800.04 | 866.89 | 0.830 | 4.81 | |

| TCN | 12 | 605.51 | 1,015,795.69 | 926.17 | 0.811 | 5.34 | |

| TCN | 24 | 650.68 | 1,206,018.53 | 1012.81 | 0.777 | 5.72 | |

| Cluster 3 | GRU | 1 | 80.90 | 29,954.39 | 119.94 | 0.792 | 3.54 |

| GRU | 6 | 134.72 | 109,476.50 | 199.42 | 0.740 | 4.78 | |

| GRU | 12 | 161.39 | 154,886.04 | 232.38 | 0.694 | 5.57 | |

| GRU | 24 | 180.36 | 190,159.07 | 258.16 | 0.674 | 6.19 | |

| LSTM | 1 | 85.25 | 125,815.35 | 170.24 | 0.784 | 6.08 | |

| LSTM | 6 | 106.76 | 135,212.41 | 198.86 | 0.733 | 7.46 | |

| LSTM | 12 | 118.03 | 139,762.63 | 209.75 | 0.702 | 8.40 | |

| LSTM | 24 | 120.71 | 141,269.81 | 219.07 | 0.688 | 8.48 | |

| Prophet | 1 | 33.81 | 3689.77 | 49.22 | 0.893 | 2.31 | |

| Prophet | 6 | 36.12 | 3097.77 | 48.41 | 0.836 | 2.66 | |

| Prophet | 12 | 37.42 | 3677.56 | 53.65 | 0.947 | 2.48 | |

| Prophet | 24 | 28.75 | 1861.39 | 38.28 | 0.957 | 1.93 | |

| TCN | 1 | 76.03 | 193,888.43 | 175.58 | 0.809 | 5.32 | |

| TCN | 6 | 95.62 | 215,352.98 | 207.00 | 0.757 | 6.66 | |

| TCN | 12 | 109.83 | 207,395.99 | 216.53 | 0.729 | 7.76 | |

| TCN | 24 | 118.46 | 182,788.03 | 223.97 | 0.685 | 8.49 |

| Cluster | Horizon (h) | Metric | H-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | 1 | MAE | 5.051 | 0.168 |

| Cluster 1 | 1 | MAPE | 2.051 | 0.562 |

| Cluster 1 | 1 | MSE | 4.699 | 0.195 |

| Cluster 1 | 1 | R2 | 1.541 | 0.673 |

| Cluster 1 | 1 | RMSE | 5.051 | 0.168 |

| Cluster 1 | 6 | MAE | 4.390 | 0.222 |

| Cluster 1 | 6 | MAPE | 2.846 | 0.416 |

| Cluster 1 | 6 | MSE | 4.853 | 0.183 |

| Cluster 1 | 6 | R2 | 2.801 | 0.423 |

| Cluster 1 | 6 | RMSE | 4.853 | 0.183 |

| Cluster 1 | 12 | MAE | 3.949 | 0.267 |

| Cluster 1 | 12 | MAPE | 3.596 | 0.309 |

| Cluster 1 | 12 | MSE | 4.853 | 0.183 |

| Cluster 1 | 12 | R2 | 4.257 | 0.235 |

| Cluster 1 | 12 | RMSE | 4.853 | 0.183 |

| Cluster 1 | 24 | MAE | 5.316 | 0.150 |

| Cluster 1 | 24 | MAPE | 3.596 | 0.309 |

| Cluster 1 | 24 | MSE | 5.515 | 0.138 |

| Cluster 1 | 24 | R2 | 3.265 | 0.353 |

| Cluster 1 | 24 | RMSE | 5.515 | 0.138 |

| Cluster 2 | 1 | MAE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 1 | MAPE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 1 | MSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 1 | R2 | 5.333 | 0.021 |

| Cluster 2 | 1 | RMSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 6 | MAE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 6 | MAPE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 6 | MSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 6 | R2 | 4.083 | 0.043 |

| Cluster 2 | 6 | RMSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 12 | MAE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 12 | MAPE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 12 | MSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 12 | R2 | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 12 | RMSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 24 | MAE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 24 | MAPE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 24 | MSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 24 | R2 | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 2 | 24 | RMSE | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| Cluster 3 | 1 | MAE | 15.007 | 0.020 |

| Cluster 3 | 1 | MAPE | 6.931 | 0.327 |

| Cluster 3 | 1 | MSE | 14.268 | 0.027 |

| Cluster 3 | 1 | R2 | 17.224 | 0.008 |

| Cluster 3 | 1 | RMSE | 14.357 | 0.026 |

| Cluster 3 | 6 | MAE | 14.860 | 0.021 |

| Cluster 3 | 6 | MAPE | 4.759 | 0.575 |

| Cluster 3 | 6 | MSE | 11.837 | 0.066 |

| Cluster 3 | 6 | R2 | 15.103 | 0.019 |

| Cluster 3 | 6 | RMSE | 12.000 | 0.062 |

| Cluster 3 | 12 | MAE | 11.948 | 0.063 |

| Cluster 3 | 12 | MAPE | 5.298 | 0.506 |

| Cluster 3 | 12 | MSE | 11.793 | 0.067 |

| Cluster 3 | 12 | R2 | 8.823 | 0.184 |

| Cluster 3 | 12 | RMSE | 12.429 | 0.053 |

| Cluster 3 | 24 | MAE | 9.591 | 0.143 |

| Cluster 3 | 24 | MAPE | 4.869 | 0.561 |

| Cluster 3 | 24 | MSE | 8.328 | 0.215 |

| Cluster 3 | 24 | R2 | 8.852 | 0.182 |

| Cluster 3 | 24 | RMSE | 8.328 | 0.215 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tiwari, A.; Kukreja, R.; Subramanian, S.; Devkar, A.; Mahabir, R.; Gkountouna, O.; Croitoru, A. Machine Learning for Sustainable Urban Energy Planning: A Comparative Model Analysis. Energies 2026, 19, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010176

Tiwari A, Kukreja R, Subramanian S, Devkar A, Mahabir R, Gkountouna O, Croitoru A. Machine Learning for Sustainable Urban Energy Planning: A Comparative Model Analysis. Energies. 2026; 19(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleTiwari, Abhiraj, Rushil Kukreja, Sanjeev Subramanian, Anush Devkar, Ron Mahabir, Olga Gkountouna, and Arie Croitoru. 2026. "Machine Learning for Sustainable Urban Energy Planning: A Comparative Model Analysis" Energies 19, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010176

APA StyleTiwari, A., Kukreja, R., Subramanian, S., Devkar, A., Mahabir, R., Gkountouna, O., & Croitoru, A. (2026). Machine Learning for Sustainable Urban Energy Planning: A Comparative Model Analysis. Energies, 19(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010176