Research on the Energy Conversion Mechanism of Engine Speed, Turbulence and Combustion Stability Based on Large Eddy Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

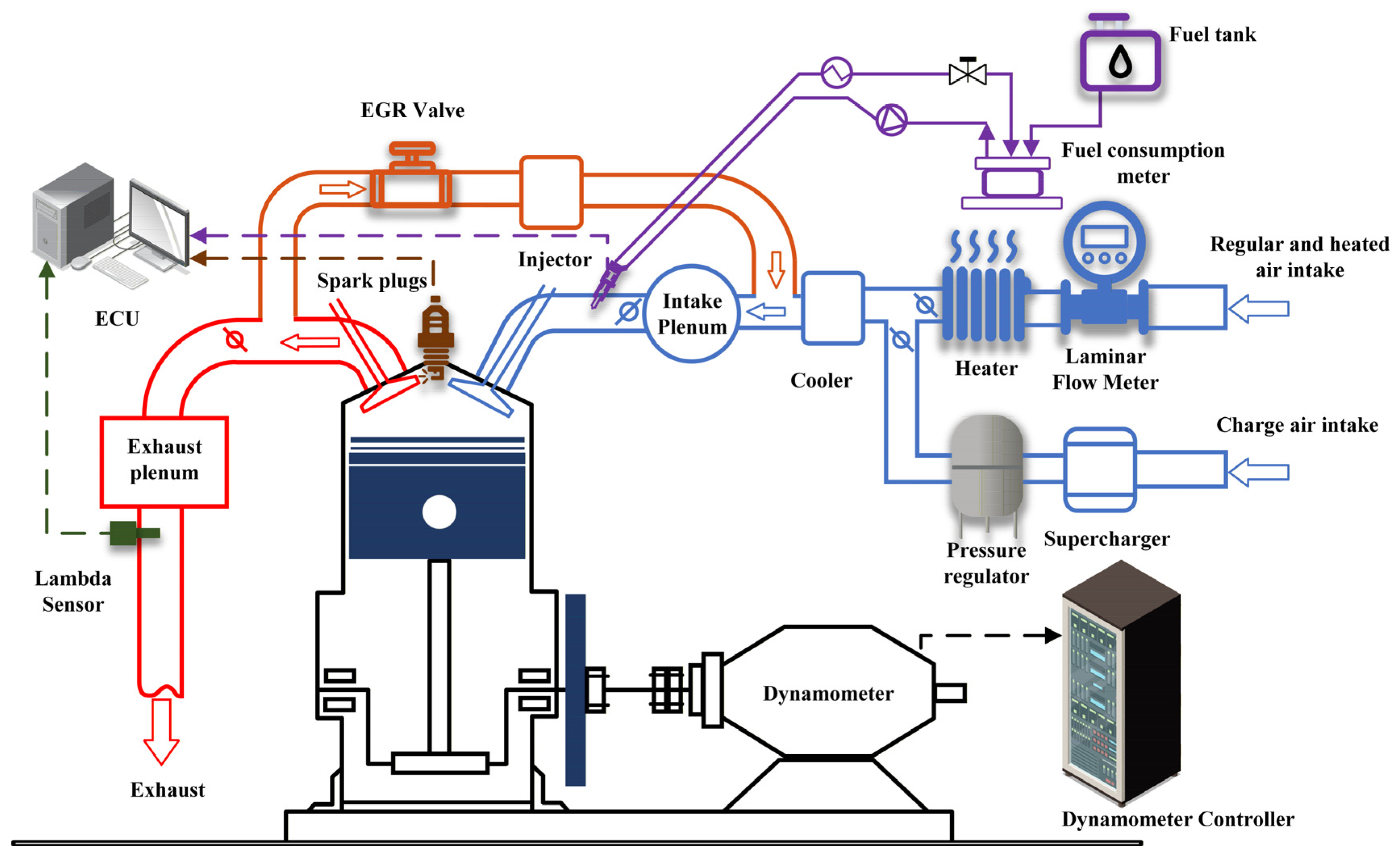

2. Engine Calculation Model and Experimental Setup

2.1. Turbulence and Combustion Simulation Models

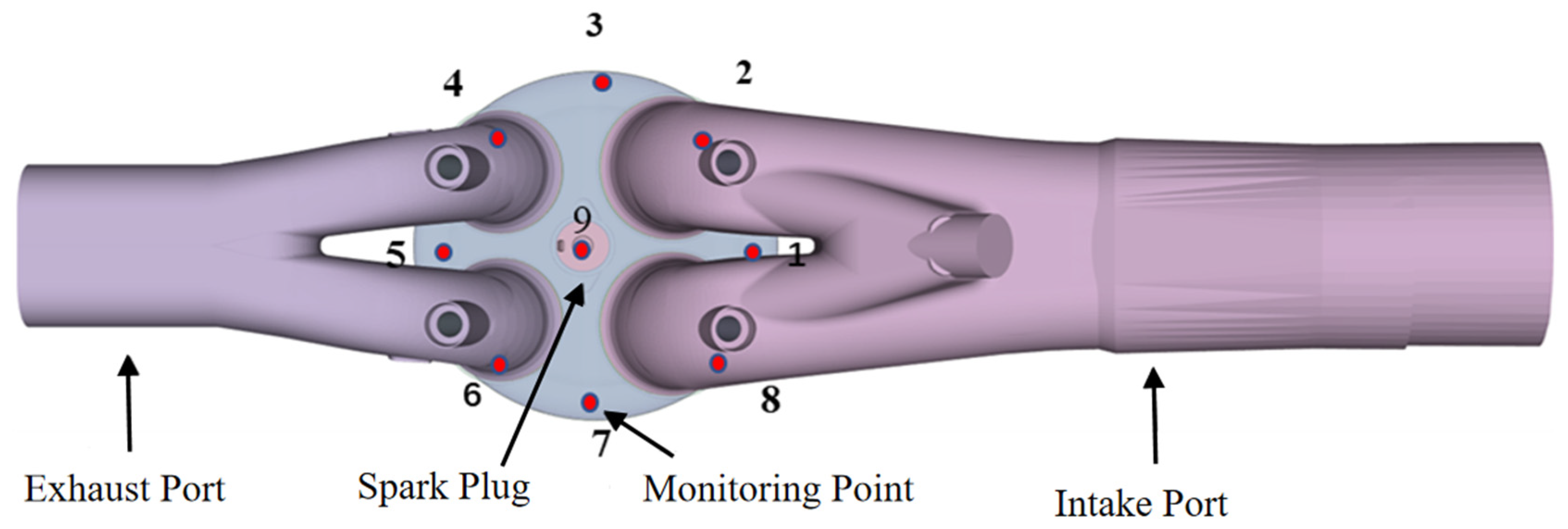

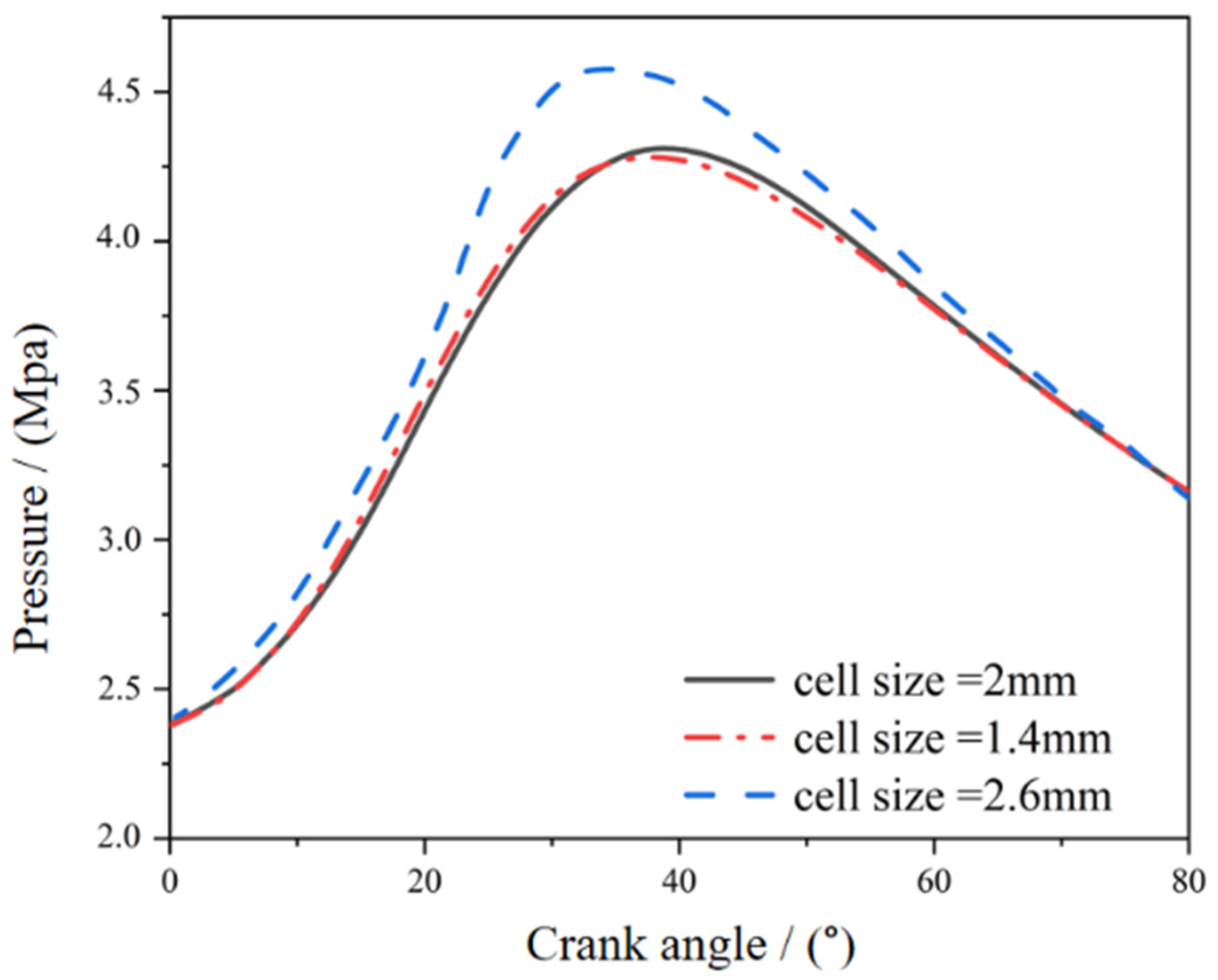

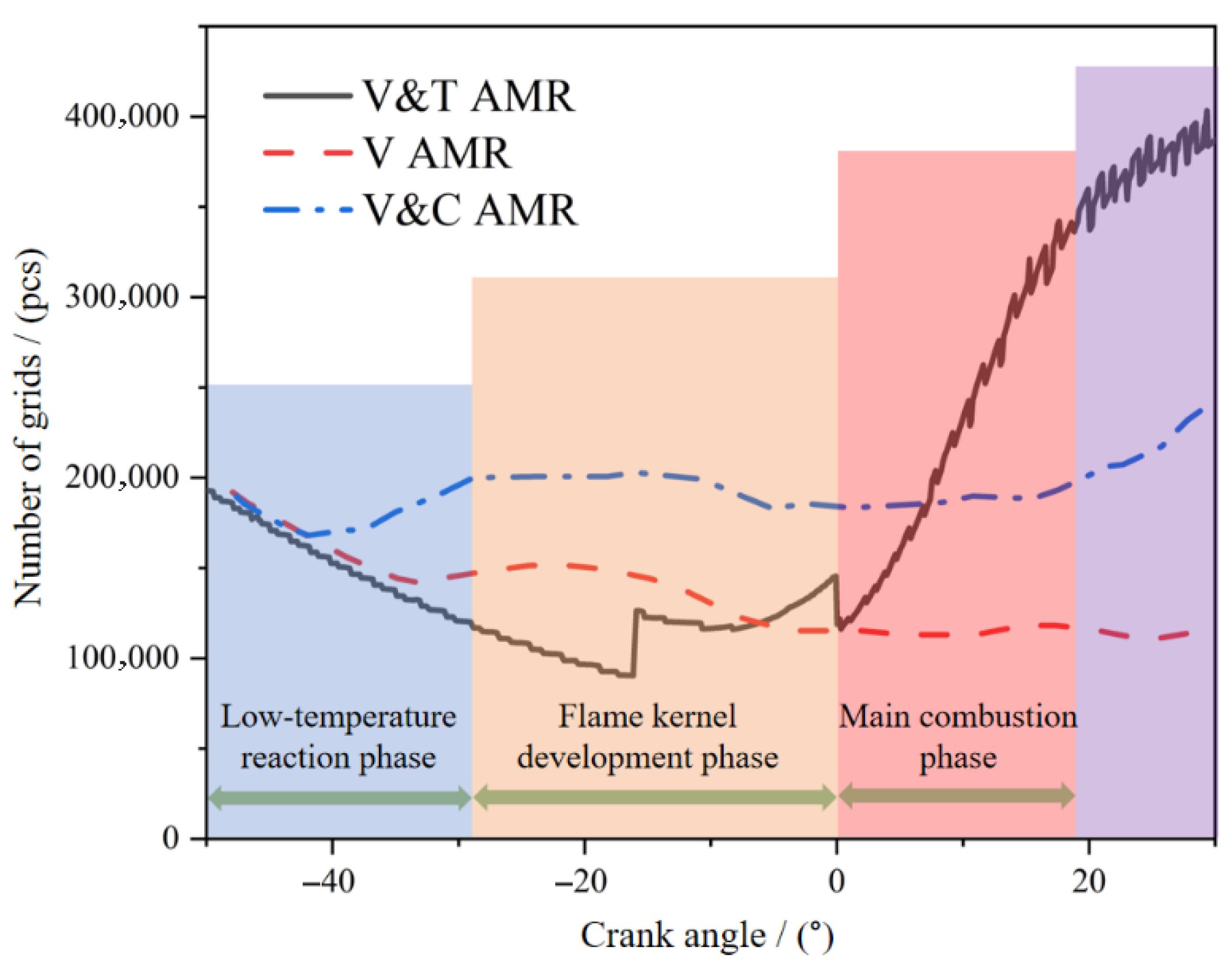

2.2. Engine Simulation Model and Grid Density Selection

2.3. Verification of Numerical Models

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Effect of the Rotation Speed on the CCV

3.2. Static Inducement of CCV in Internal Combustion Engines

3.3. The Dynamic Mechanism of CCV in Internal Combustion Engines

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- CCV Characteristics: Increasing engine speed monotonically reduces the fluctuation of the maximum burst pressure (the maximum of COVP decreased from 14.9% to 9.48%). In contrast, the COVφ exhibits a non-monotonic trend (first decreasing, then increasing). Additionally, a strong negative correlation was observed between the peak pressure and its corresponding crank angle.

- (2)

- Effect of Initial Conditions: High peak pressure cycles are correlated with broader distributions of hot residual gas at ignition, which accelerates the early chemical reaction rate. Conversely, higher engine speeds steepen the fuel concentration gradient from the spark plug to the intake valve. This inhomogeneity in the mixture amplifies the cyclic variability of the combustion phasing.

- (3)

- Turbulence and Flame Propagation: Enhanced turbulence at high speeds promotes early flame kernel development; however, it is insufficient to fully compensate for the reduced physical time per crank angle, resulting in retarded combustion phasing (CA50 delayed from 15 to 22 CAD). Furthermore, the symmetric flow structure directs the flame front evolution, making the intake valve region the primary site for end-gas auto-ignition (knock).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, A.K.; Mounaïm-Rousselle, C.; Brequigny, P.; Dhar, A.; Hespel, C.; Patel, C.; Srivastava, D.K.; Duraisamy, G.; Le Moyne, L.; Sharma, N.; et al. Future of internal combustion engines using sustainable, scalable, and storable E-fuels and biofuels for decarbonizing transport and enabling advanced combustion technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 110, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.H.; Jan Aaldering, L. Strategic intentions to the diffusion of electric mobility paradigm: The case of internal combustion engine vehicle. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyam, A. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel for internal combustion engines: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 82, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, V.; Sridharan, N.V.; Feroskhan, M.; Vaithiyanathan, S.; Subramanian, B.; Tsai, P.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lay, C.-H.; Wang, C.-T.; Ponnusamy, V.K. Biogas production and its utilization in internal combustion engines—A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 186, 518–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hong, C.; Wang, S.; Qiang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiang, J.; Yang, J.; Ji, C. Research on energy management strategies for ammonia-hydrogen internal combustion engine hybrid electrical vehicles. Energy 2025, 334, 137548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Zhu, D.; Deng, J.; Dibble, R.; Dong, G.; Li, L. Advances in ion current detection technology for engine applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2026, 112, 101253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Ouyang, M.; Yang, F. Real-time start of combustion detection based on cylinder pressure signals for compression ignition engines. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 114, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ni, X.; Su, X.; Weng, C.; Yao, C. The effect of ignition intensity and in-cylinder pressure on the knock intensity and detonation formation in internal combustion engines. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 200, 117690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, N.; Beatrice, C.; Vassallo, A.; Pesce, F.; Gessaroli, D.; Biet, C.; Guido, C. Experimental study of cycle-by-cycle variations in a spark ignition internal combustion engine fueled with hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 60, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Tao, C.; Xu, T.; Song, M. The engine knock analysis—An overview. Appl. Energy 2012, 92, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Lappas, P.; Shamekhi, A.-M.; Wang, X.; Mikulski, M. Advancements in detecting combustion events through vibration analysis in internal combustion engines: A literature review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 241, 113539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Kurien, C.; Mittal, M. Computational investigation and analysis of cycle-to-cycle combustion variations in a spark-ignition engine utilizing methane-ammonia blends. Fuel 2025, 386, 134313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakopoulos, C.D.; Rakopoulos, D.C.; Kosmadakis, G.M.; Zannis, T.C.; Kyritsis, D.C. Studying the cyclic variability (CCV) of performance and NO and CO emissions in a methane-run high-speed SI engine via quasi-dimensional turbulent combustion modeling and two CCV influencing mechanisms. Energy 2023, 272, 127042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadekar, S.; Janas, P.; Oevermann, M. Large-eddy simulation study of combustion cyclic variation in a lean-burn spark ignition engine. Appl. Energy 2019, 255, 113812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenstein, T.; Kang, S.; Cai, L.; Bode, M.; Pitsch, H. DNS study of the global heat release rate during early flame kernel development under engine conditions. Combust. Flame 2020, 213, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, S.; Gößnitzer, C.; Lang, M.; Novella, R.; Steiner, H.; Wimmer, A. Turbulent combustion modeling for internal combustion engine CFD: A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 106, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Truffin, K.; Jay, S. Cause-and-effect chain analysis of combustion cyclic variability in a spark-ignition engine using large-eddy simulation, Part I: From tumble compression to flame initiation. Combust. Flame 2024, 267, 113566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Truffin, K.; Jay, S. Cause-and-effect chain analysis of combustion cyclic variability in a spark-ignition engine using large-eddy simulation, Part II: Origins of flow variations from intake. Combust. Flame 2024, 267, 113565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, A.; Iacovano, C.; Fontanesi, S. Large-Eddy simulation of lean and ultra-lean combustion using advanced ignition modelling in a transparent combustion chamber engine. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 115949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Meng, S.; Han, Z.; Dong, G.; Reitz, R.D. Progress in knock combustion modeling of spark ignition engines. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Zhan, Q.; Ji, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, S. Identification, prediction and classification of hydrogen-fueled Wankel rotary engine knock by data-driven based on combustion parameters. Energy 2024, 308, 133029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Feng, L.; Xia, Y. The mechanism and effect factors of the combustion cycle-to-cycle variations in the spark ignition engine. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 4773–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Hou, K.; Duan, X.; Xu, Z. The correlation between intake fluctuation and combustion CCV (cycle-to-cycle variations) on a high speed gasoline engine: A wide range operating condition study. Fuel 2021, 304, 121336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroteaux, F.; Mancaruso, E.; Vaglieco, B.M. Optical and Numerical Investigations on Combustion and OH Radical Behavior Inside an Optical Engine Operating in LTC Combustion Mode. Energies 2023, 16, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Ying, W.; Chen, A.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Qiao, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, X. Study on the Impact of Ammonia–Diesel Dual-Fuel Combustion on Performance of a Medium-Speed Diesel Engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, E. Correlations between cycle-to-cycle variations and combustion parameters of a spark ignition engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2004, 24, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdor, N.; Dulger, M.; Sher, E. Cyclic Variability in Spark Ignition Engines A Literature Survey. SAE Trans. 1994, 24, 1514–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Kaiser, E.; Borée, J.; Noack, B.R.; Thomas, L.; Guilain, S. Cluster-based analysis of cycle-to-cycle variations: Application to internal combustion engines. Exp. Fluids 2014, 55, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.; Tinaut, F.V.; Giménez, B.; Pérez, A. Characterization of cycle-to-cycle variations in a natural gas spark ignition engine. Fuel 2015, 140, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, L.; Liu, T. Numerical Simulation Research on Combustion and Emission Characteristics of Diesel/Ammonia Dual-Fuel Low-Speed Marine Engine. Energies 2024, 17, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimescu, A.; Vaglieco, B.M.; Merola, S.S.; Zollo, V.; De Marinis, R. Conversion of a Small-Size Passenger Car to Hydrogen Fueling: Simulation of CCV and Evaluation of Cylinder Imbalance. Machines 2023, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciupek, B.; Brodzik, Ł.; Frąckowiak, A. Research on Carbon Footprint Reduction During Hydrogen Co-Combustion in a Turbojet Engine. Energies 2024, 17, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfriso, S.; Berni, F.; Fontanesi, S.; D’Adamo, A.; Breda, S.; Teodosio, L.; Frigo, S.; Antonelli, M. Combination of G-Equation and Detailed Chemistry: An application to 3D-CFD hydrogen combustion simulations to predict NOx emissions in reciprocating internal combustion engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 89, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Yeung, P.-K.; Kim, W.-W. Effect of subgrid models on the computed interscale energy transfer in isotropic turbulence. Comput. Fluids 1996, 25, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Feng, S.; Chen, X. Enhancing the ammonia energy proportion of ammonia hydrogen internal combustion engines through oxygen enriched combustion strategy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 172, 150603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Ayala, F.; Keck, J.C. A reduced chemical kinetic model for HCCI combustion of primary reference fuels in a rapid compression machine. Combust. Flame 2003, 133, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurushima, T. A new skeletal PRF kinetic model for HCCI combustion. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2009, 32, 2835–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Yang, W. Effects of Combustion Chamber Shapes on Combustion and Emission Characteristics for the N-Octanol Fueled Compression Ignition Engine. J. Energy Eng. 2022, 148, 04022011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Qiao, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Guan, J.; Wang, R.; Duan, X. The effect of variable enhanced Miller cycle combined with EGR strategy on the cycle-by-cycle variations and performance of high compression ratio engines based on asynchronous valve opening strategy. Energy 2025, 320, 135307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zheng, Z. Effects of Piston Shape on the Performance of a Gasoline Direct Injection Engine. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 34635–34649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Shi, J.; Cheng, Q. Numerical simulation study on cycle-to-cycle variations of diesel-natural gas-hydrogen RCCI engine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 118, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaclerio, F.; Fornarelli, F.; Masurier, J.-B.; Mounaïm-Rousselle, C. Impact of oxygen enrichment on ammonia combustion in spark-ignition engines under partial load conditions. Fuel 2026, 404, 135910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Gong, Y.; Qian, D.; Liu, M.; Ma, H.; Xie, F. Optical investigation of the influence of passive pre-chamber turbulent jet ignition on the combustion characteristics of carbon-free ammonia-hydrogen engines. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 278, 127200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, F.A.M.; Douasbin, Q.; Dounia, O.; Vermorel, O.; Jaravel, T. Flame-turbulence interactions in lean hydrogen flames: Implications for turbulent flame speed and fractal modelling. Combust. Flame 2025, 273, 113926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xiong, Q.; Yi, X.; Zhou, X.; Yang, W.; Liu, L.; Zhao, J. Simulation on enhanced combustion characteristics of lean ammonia by pre-chamber turbulent jet-flame ignition strategy in a medium-speed engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, C.; Gong, W. Influence of In-Cylinder Turbulence Kinetic Energy on the Mixing Uniformity within Gaseous-Fuel Engines under Various Intake Pressure Conditions. Energies 2024, 17, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Fan, M.; Pan, J.; Yang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, H.; Wu, X. Research and evaluation of turbulent jet ignition mode for improving combustion performance of ethanol rotary engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 261, 125067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T.; Chen, F.; Qiu, S.; Wu, D.; Gao, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, C. Research on the Intake Port of a Uniflow Scavenging GDI Opposed-Piston Two-Stroke Engine. Energies 2022, 15, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Ji, C. Effects of N2 dilution on NH3/H2/air combustion using turbulent jet ignition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Liu, J.; Liang, J.; Jia, D.; Wang, R.; Shen, D.; Duan, X. Experimental investigation the effects of Miller cycle coupled with asynchronous intake valves on cycle-to-cycle variations and performance of the SI engine. Energy 2023, 263, 125868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Boundary Conditions | Value |

|---|---|

| Piston | 450 K |

| Cylinder Head | 450 K |

| Cylinder Wall | 450 K |

| Intake Valve Underside | 480 K |

| Intake Valve Seat Angle | 480 K |

| Exhaust Valve Underside | 525 K |

| Exhaust Valve Seat Angle | 525 K |

| Fixed Embedding Area | Encryption Level | Grid Size/(mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Cylinder Wall | 1 | 1 |

| Intake Valve Seat Angle | 2 | 0.5 |

| Exhaust Valve Seat Angle | 1 | 1 |

| Spark Plug | 4 | 0.125 |

| Spark Plug Vicinity | 3 | 0.25 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Bore | 86 mm |

| Stroke | 90 mm |

| Compression ratio | 9.86 |

| Intake pressure | 0.1 Mpa |

| Excess air ratio | 1.0 |

| Ignition timing | 17 CAD bTDC |

| Rotational speed | 3000/4000/5000 (rpm) |

| Intake valve opening | −410 CAD aTDC |

| Intake valve closing | −100 CAD aTDC |

| Exhaust valve opening | 140 CAD aTDC |

| Exhaust valve closing | 370 CAD aTDC |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Molecular formula | C8H18 |

| Octane number | 95 |

| Calorific value | 44.6 |

| Ignition point | 427 °C |

| Speed Conditions | R2 | RMSE | MAE | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3000 rpm | 0.988 | 0.119 | 0.063 | 2.439 |

| 4000 rpm | 0.963 | 0.192 | 0.112 | 5.061 |

| 5000 rpm | 0.997 | 0.037 | 0.023 | 0.924 |

| Average | 0.983 | 0.116 | 0.066 | 2.808 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Cheng, M.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, S.; Pan, M.; Guan, W.; Li, M.; Sang, H. Research on the Energy Conversion Mechanism of Engine Speed, Turbulence and Combustion Stability Based on Large Eddy Simulation. Energies 2026, 19, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010175

Zhang Z, Cheng M, Wang H, Zhou S, Zhang S, Pan M, Guan W, Li M, Sang H. Research on the Energy Conversion Mechanism of Engine Speed, Turbulence and Combustion Stability Based on Large Eddy Simulation. Energies. 2026; 19(1):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010175

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zijian, Milan Cheng, Hui Wang, Shengkai Zhou, Song Zhang, Mingzhang Pan, Wei Guan, Mantian Li, and Hailang Sang. 2026. "Research on the Energy Conversion Mechanism of Engine Speed, Turbulence and Combustion Stability Based on Large Eddy Simulation" Energies 19, no. 1: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010175

APA StyleZhang, Z., Cheng, M., Wang, H., Zhou, S., Zhang, S., Pan, M., Guan, W., Li, M., & Sang, H. (2026). Research on the Energy Conversion Mechanism of Engine Speed, Turbulence and Combustion Stability Based on Large Eddy Simulation. Energies, 19(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010175