1. Introduction

Against the dual backdrop of rising global energy demand and increasing environmental pressures, nuclear energy has gained prominence as a clean, efficient, and stable energy source. As a leading candidate of the Generation IV advanced nuclear reactor systems [

1], molten salt reactors (MSRs) have attracted significant research interest worldwide due to their inherent advantages and broad application prospects, including inherent safety features, high-temperature thermal efficiency, and efficient thorium utilization [

2,

3]. Following the MSRE reactor built and operated by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in the 1960s [

4], the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics (SINAP) in China has independently developed and successfully achieved criticality and full-power operation of the TMSR-LF1 experimental reactor. Research continues to focus on advancing small modular molten salt reactor technologies.

Concurrently, several other countries and institutions are actively engaged in developing liquid-fueled MSRs, including fast-spectrum designs. Notable examples include the 1 MWt graphite-moderated molten salt research reactor at Abilene Christian University, which has recently obtained a construction permit from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) [

5,

6]. Furthermore, Hanyang University in South Korea is developing a natural circulation-based multi-purpose innovative small modular molten salt fast reactor system, conducting both conceptual design and fundamental research on key technologies [

5,

7,

8].

The key technical feature of MSRs is the use of Liquid Nuclear Fuel. The fission material (such as UF4) is dissolved in the molten salt carrier (such as FLiBe), which also acts as a coolant [

5,

9]. It is the main distinction from commercial water-cooled reactors and other advanced reactor designs. The liquid nature of the fuel salt presents significant thermal-hydraulic design challenges, especially in the case of high power density of fuel salt. Firstly, during normal operation, the fuel salt in the core exhibits a very high volumetric heat generation rate. Current experimental MSR designs typically achieve power densities around 20 MW/m

3 or lower [

10], with future designs aimed at exceeding 100 MW/m

3 or more [

11]. This is mainly because increasing power density is one of the best ways to enhance the economic efficiency of MSRs [

10,

12]. Secondly, the fuel salt also acts as the primary coolant, responsible for removing heat from structural components within the core, such as graphite moderator and alloys. Maintaining these materials below their temperature limits is critical for structural integrity, which places high demands and expectations on design accuracy [

12,

13]. Consequently, experimental investigation into the thermal-hydraulic behavior of fluids with internal heat generation is essential for validating flow and heat transfer models, which underpin the design and development of MSRs.

Nevertheless, the simultaneous flow and self-heating characteristics of molten fuel salts represent a unique thermodynamic phenomenon rarely observed in nature, with parallels limited to nuclear fission/fusion, chemical neutralization, or combustion processes. Experimental methodologies capable of replicating internal heat generation in flowing fluids remain scarce. Experimental investigations of internally heated fluids originated in 1962 at UCLA, where alternating current heating of electrolyte aqueous solutions revealed laminar flow temperature profiles consistent with theoretical predictions [

14]. Subsequent studies by Kinney [

15] and Michiyoshi [

16] employed analogous methods but were limited to bulk temperature measurements, with insufficient resolution for turbulent flow wall temperature gradients and wall heat transfer characteristics. Recently, Park [

17] adopted a similar approach by using electrical dissipation in an H

2SO

4 electrolyte solution to generate an internal heat source, investigating secondary flow effects in laminar flow through a horizontal pipe. However, the achieved power density remained relatively low, with a maximum value of only 1.09 MW/m

3. Furthermore, their study did not include a reliable analysis of the power density distribution within the fluid. Notably, no substantive experimental progress has been reported in molten salt systems with volume internal heat sources over the past five decades.

Recent advances in studies of molten salts with internal heat sources have primarily focused on numerical simulations. The group of Politecnico di Milan [

12,

18,

19] conducted comparative COMSOL/FLUENT analyses of FLiBe salt flow in core channels, revealing that conventional Nusselt (Nu) correlations overestimate heat transfer coefficients by up to 70% under internal heating conditions, prompting the development of global correction factors. Similarly, Fiorina [

20] proposed Reynolds-Prandtl (Re-Pr) correction models based on RANS simulations for high-Prandtl (7.5 < Pr < 20) molten salts, introducing enhanced wall functions to quantify volume internal heat source effects on wall heat transfer augmentation. Lecce [

21] advanced modified Nu correction factors via OpenFOAM simulations, demonstrating improved temperature field prediction accuracy for high-Pr molten salts using low-Reynolds turbulence models. These numerical studies lack enough experimental validation due to methodological challenges in replicating volume internal heat sources.

Early studies in the 20th century used alternating current (AC) Joule heating to simulate internal heat sources in fluids. In contrast, recent advances in non-contact microwave heating technology offer a more precise and powerful approach for generating volumetric heat in polar fluids, presenting significant potential for experimental applications. Microwave heating has received widespread attention in chemical engineering and process intensification owing to its advantages of being fast, selective, and volumetric, enabling enhanced reaction rates and yields [

22,

23]. These applications, however, are predominantly designed for batch processing or small-scale continuous flow chemical synthesis, where the primary objective is to achieve intense, localized heating to drive chemical reactions. Consequently, existing microwave reactor designs are not optimized for, nor have they been applied to, the distinct requirements of large-scale thermal-hydraulic experiments for nuclear applications. Such experiments demand the generation of a uniform, high-power-density (MW/m

3 scale) volumetric heat source within meter-long flow channels to accurately simulate conditions in an MSR core. Microwave heating for our purpose is advantageous because it is fast (heating only the reactants and energy loss is less), convenient (microwave power can be adjusted optionally), and environmentally benign (using electric energy for heating and no environmental pollution).

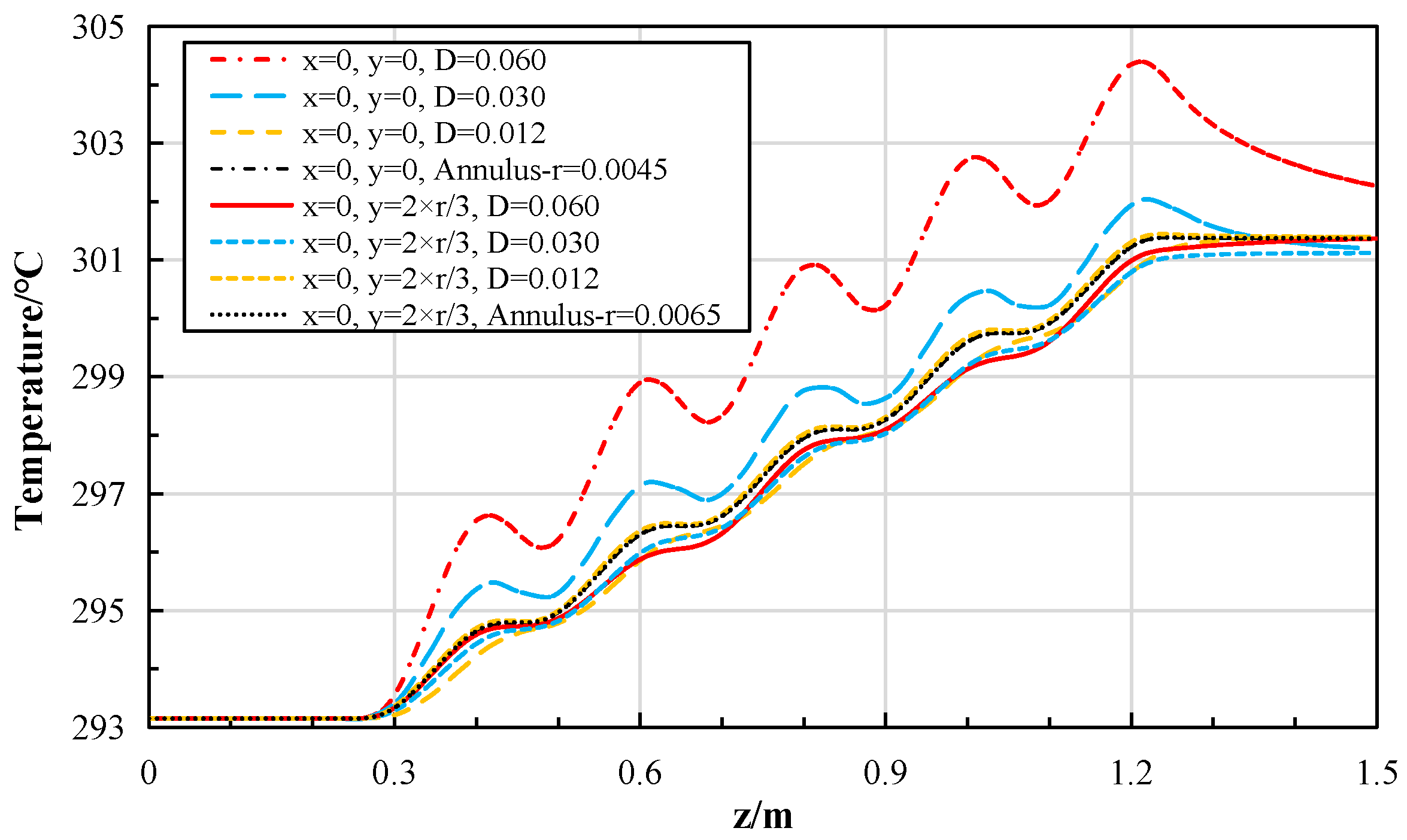

To address this methodological gap, this study proposes an innovative experimental concept for generating a volumetric heat source in fluids using microwave heating. A multi-physics numerical model was developed with COMSOL Multiphysics to validate the feasibility of the approach and to guide the design of experimental parameters. The model further enabled analysis of the inherent non-uniformity in power deposition and its dependence on the fluid geometry. The fundamental novelty of this work lies in the adaptation and numerical investigation of microwave heating specifically for MSR-relevant thermal-hydraulic experimentation. First, it presents the conceptual design and simulation of a system capable of achieving high average power densities (~6.9 MW/m3) relevant to MSR fuel salts. This represents a significant advance over the capabilities of classical AC Joule heating methods, providing a more representative experimental basis for reactor core conditions. Furthermore, the work provides a systematic analysis of power deposition uniformity and demonstrates that channel geometry—such as reduced tube diameter or an annulus—can be actively leveraged as a design parameter to improve temperature field uniformity. This offers a practical strategy to mitigate the inherent non-uniformities of microwave heating for controlled convection experiments. Finally, the design employs a cost-effective array of commercial magnetrons within a segmented cavity, balancing performance, scalability, and practical feasibility for future experimental builds. These results provide a design basis and practical guidance for subsequent experimental investigations into flow and heat transfer in fluids with a volume internal heat generation source.

2. Conceptual Design of the Experimental Setup

Microwaves are a form of electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to a microwave field, polar molecules such as water and nitrate salts undergo high-frequency oscillations. This molecular motion generates heat through friction, enabling rapid, non-contact, and controllable volumetric heating within the fluid. An innovative experimental apparatus was conceptualized and designed based on this principle to study the volume internal heat generation source in fluids using microwave heating.

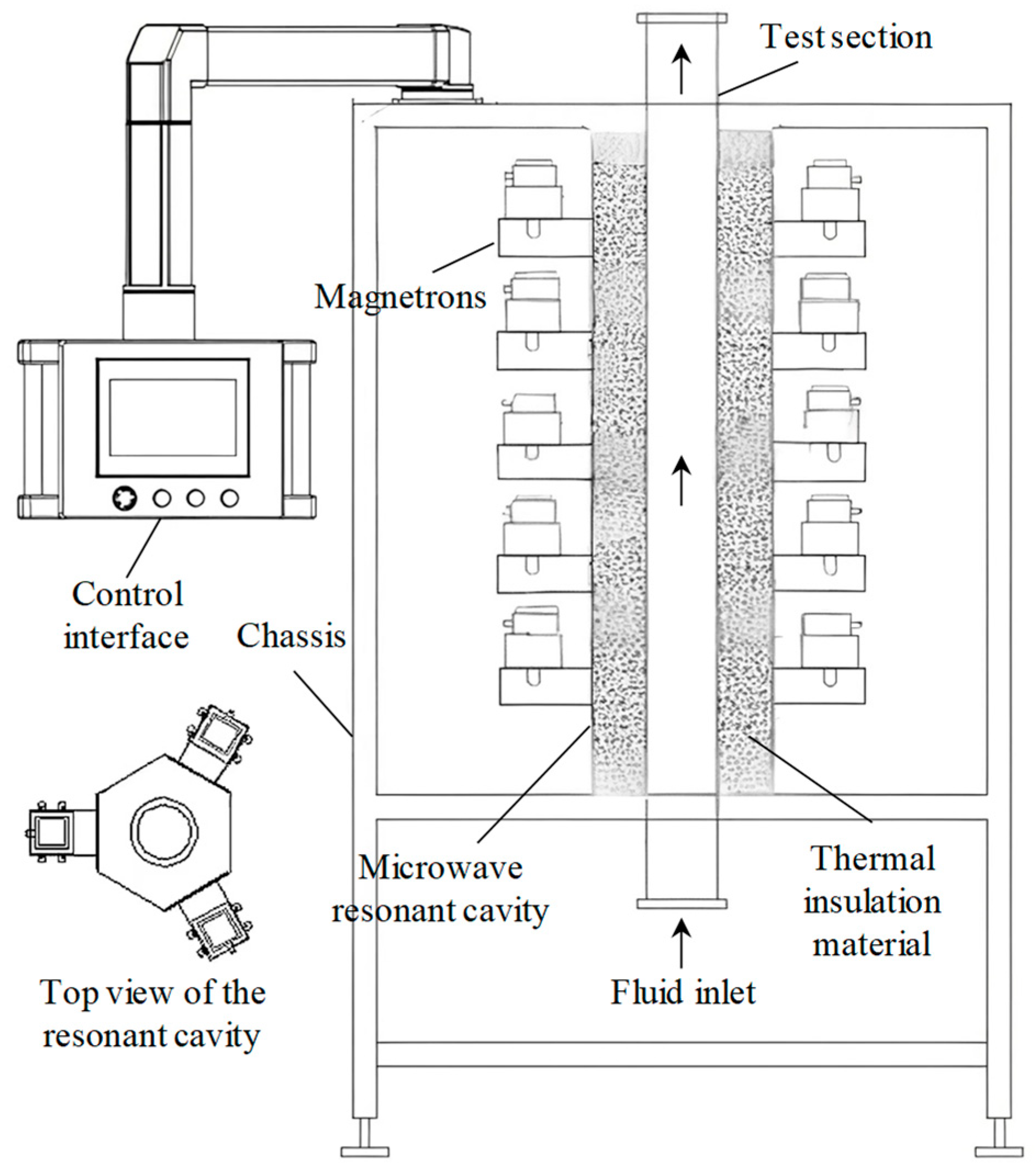

As shown in

Figure 1, the system integrates a microwave resonant cavity, a magnetron array, a test section, and a control interface. The tube of test section has a total length of 1.6 m or more, with a 1-m central zone where microwave energy is focused to create volumetric heating within the molten salt or water flowing through the tube. A critical component of the design is a vertically oriented regular hexagonal prism cavity (height: 1 m; face-to-face distance: 0.278 m). The cavity is engineered to ensure microwave field distribution as uniform as possible. The hexagonal geometry was selected after consideration of alternatives like circular or rectangular cavities. Key design drivers included the need for satisfactory heating uniformity, practical manufacturability, and ease of integrating magnetron ports and instrumentation. The multiple flat facets of the hexagon provide stable mounting surfaces and help promote a blended electromagnetic field pattern conducive to mitigating pronounced hot spots, offering a favorable balance for this experimental application.

The cavity incorporates a multi-tier magnetron configuration, with 1.5 kW magnetrons operating at 2.45 GHz arranged in 5 vertical tiers. Each tier distributes three magnetrons at 120° intervals across adjacent hexagonal facets, fed by waveguide-coupled power transmission. This configuration achieves a total microwave input power of 22.5 kW (15 magnetrons), providing sufficient power density to simulate internal heat generation rates in the reactor core while maintaining operational flexibility for parametric studies. The power density can reach 6.9 MW/m3 under these parameters of heating power, which is close to the volumetric power density of fuel salt in the design of some small modular molten salt reactors.

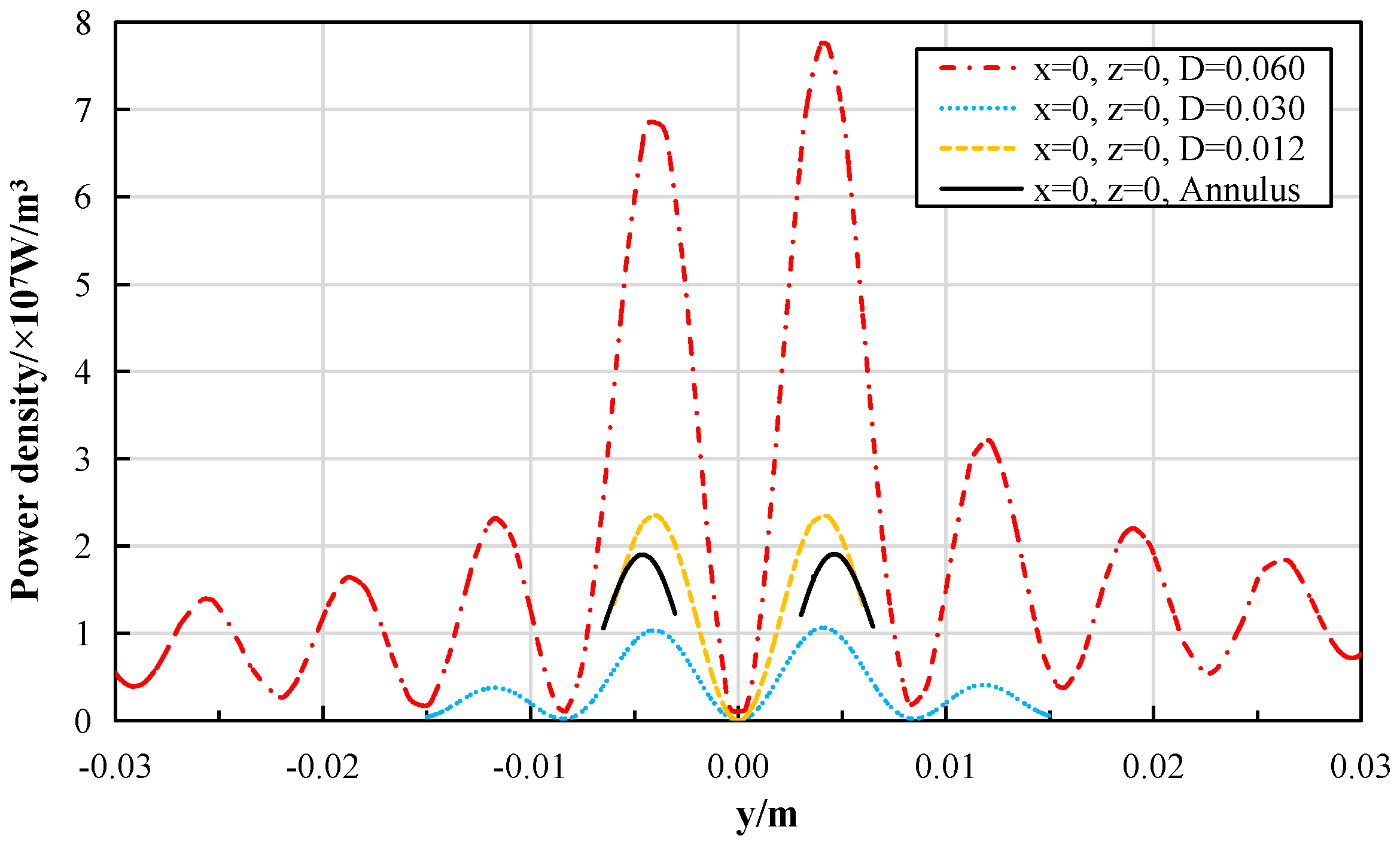

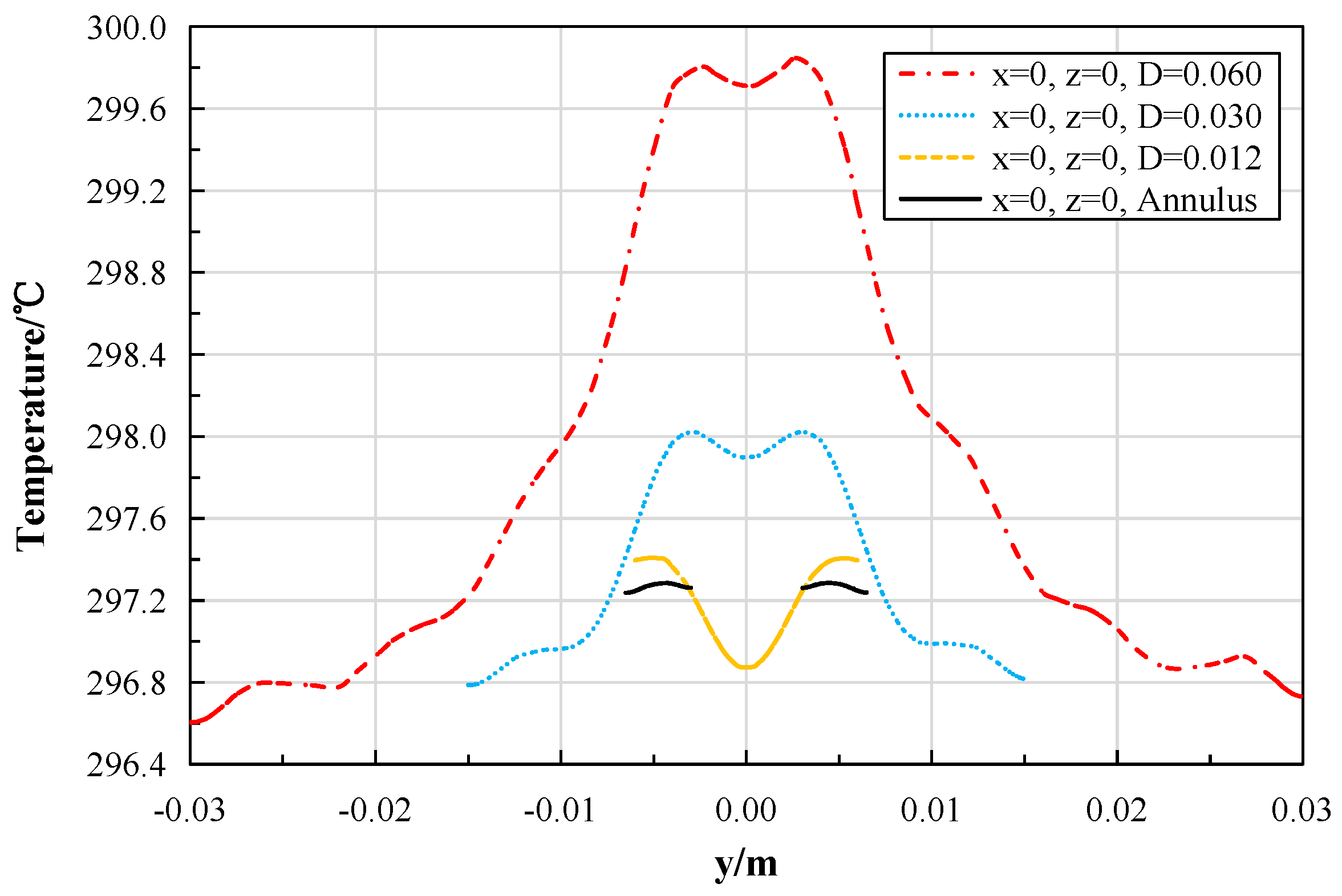

The distribution of the microwave field and the resulting power deposition depend not only on the cavity design but also on the geometry of the heated medium. Therefore, the shape and dimensions of the test section are crucial design parameters. Since typical fuel salt channels in an MSR’s core are often circular or rectangular pipes [

5,

10], the geometry of the test section can be adapted accordingly to meet specific heating performance and experimental objectives. Furthermore, as microwaves reflect off metallic surfaces, the test section must be constructed from non-metallic materials with low microwave absorption, such as quartz or ceramic [

22]. The fluid inside must be polar molecules, like water or nitrate salts, to effectively interact with the microwave. The heating efficiency is ultimately determined by the relative permittivity of fluid [

23].

3. Modeling and Simulation

3.1. Geometric Modeling

Power distribution has a direct effect on temperature distribution and further affects the research on various thermal fluid mechanics behaviors. In the graphite assembly channel of a liquid fuel molten salt reactor, the fission heat source of liquid fuel salt is related to fission nuclide concentration, neutron flux, and flow velocity [

24,

25]. The power in the region near the graphite moderator wall will be higher when the flow velocity is lower or the channel diameter is larger, but the fission power can be considered uniform in the channel with a smaller diameter [

24,

25]. Therefore, designing to obtain a uniformly distributed and sufficiently high microwave heating power density is a key objective in simulating the volume internal heat generation source phenomenon of fuel salt.

In order to obtain a fluid volume internal heat source similar to the fission heat source prototype by microwave simulation, the power density distribution of the volume internal heat source for microwave heating is simulated and optimized by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.4 software for the conceptual design of the experimental setup. One is to change the arrangement of the magnetron array and the size structure of the resonant cavity; the other is to select an appropriate polar fluid.

Common water was preferred as the heated fluid for calculation in this paper, and on this basis, the design of the resonant cavity and waveguide was carried out to establish and validate the proposed microwave heating concept. Water serves as an accessible and well-characterized polar fluid for this initial proof-of-principle and for planned near-future separate-effect experiments aimed at isolating the influence of a volumetric heat source on convective heat transfer mechanisms. It is, however, recognized that direct extrapolation of quantitative results to molten salts (e.g., FLiBe, FLiNaK, nitrate salts) requires careful consideration due to significant differences in dielectric properties (complex permittivity ε′, ε″) governing microwave absorption, and thermophysical properties (Prandtl number Pr, thermal conductivity, etc.) affecting heat transfer. Preliminary experimental tests by our group have demonstrated that ternary nitrate salt, a common simulant with a Prandtl number comparable to some fluoride salts, can be effectively melted and heated by microwaves, achieving a power density approximately 51% of that for water under similar conditions. This confirms the fundamental feasibility of the method for molten salts. A primary obstacle to detailed numerical scaling at this stage is the notable scarcity of reliable data for the complex permittivity of molten salts across relevant temperature ranges. Future work, therefore, necessitates targeted measurements of these properties.

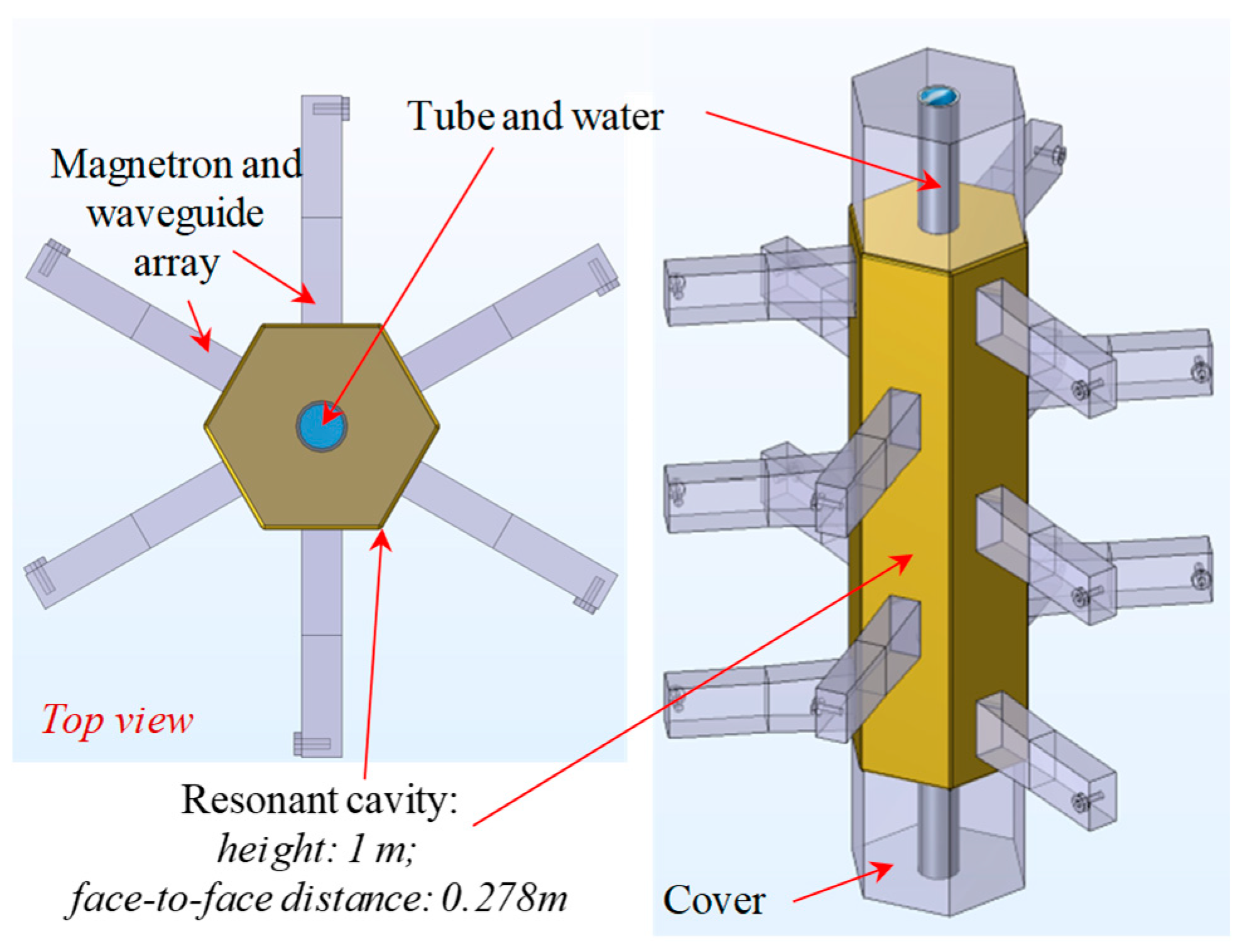

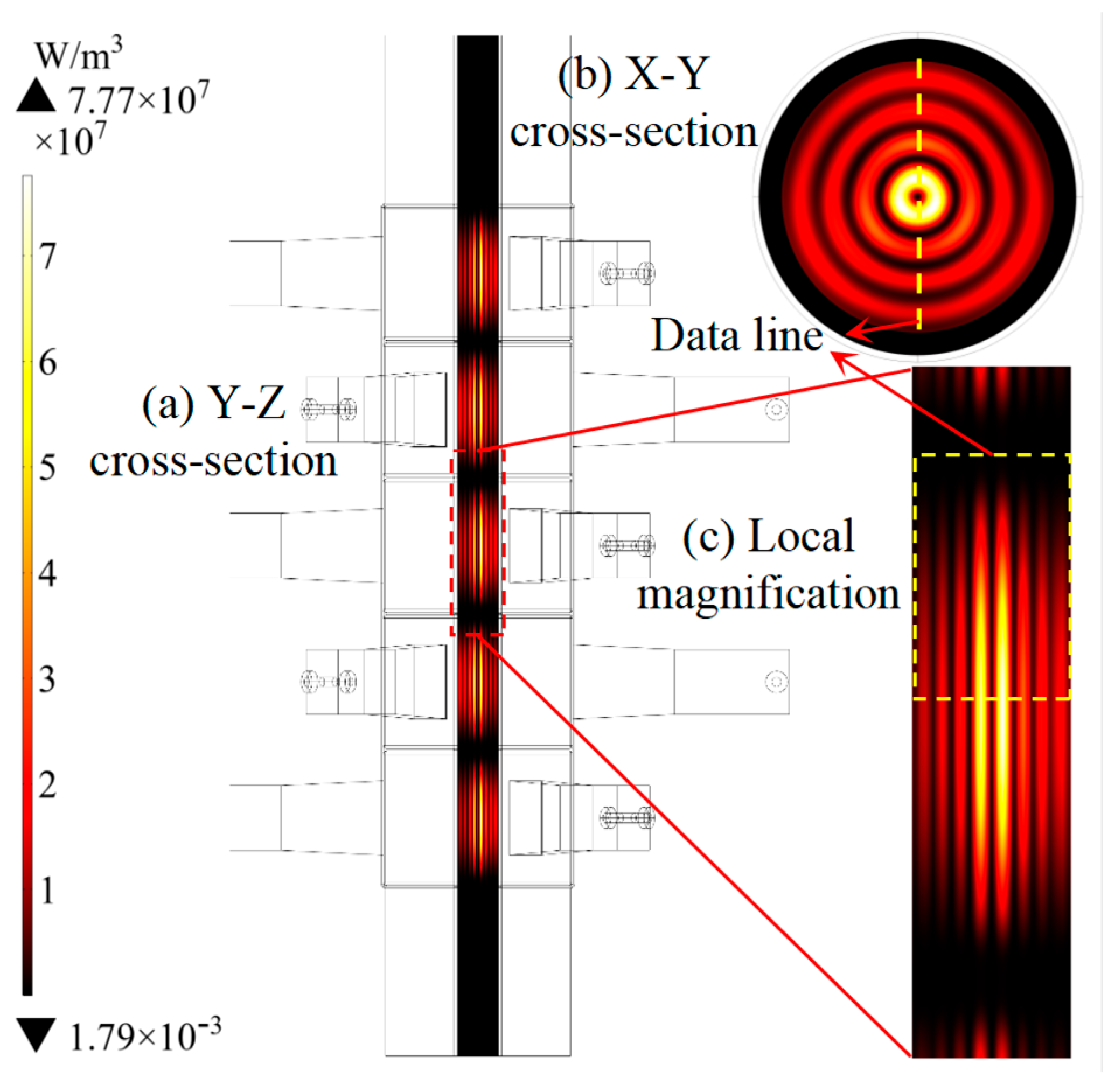

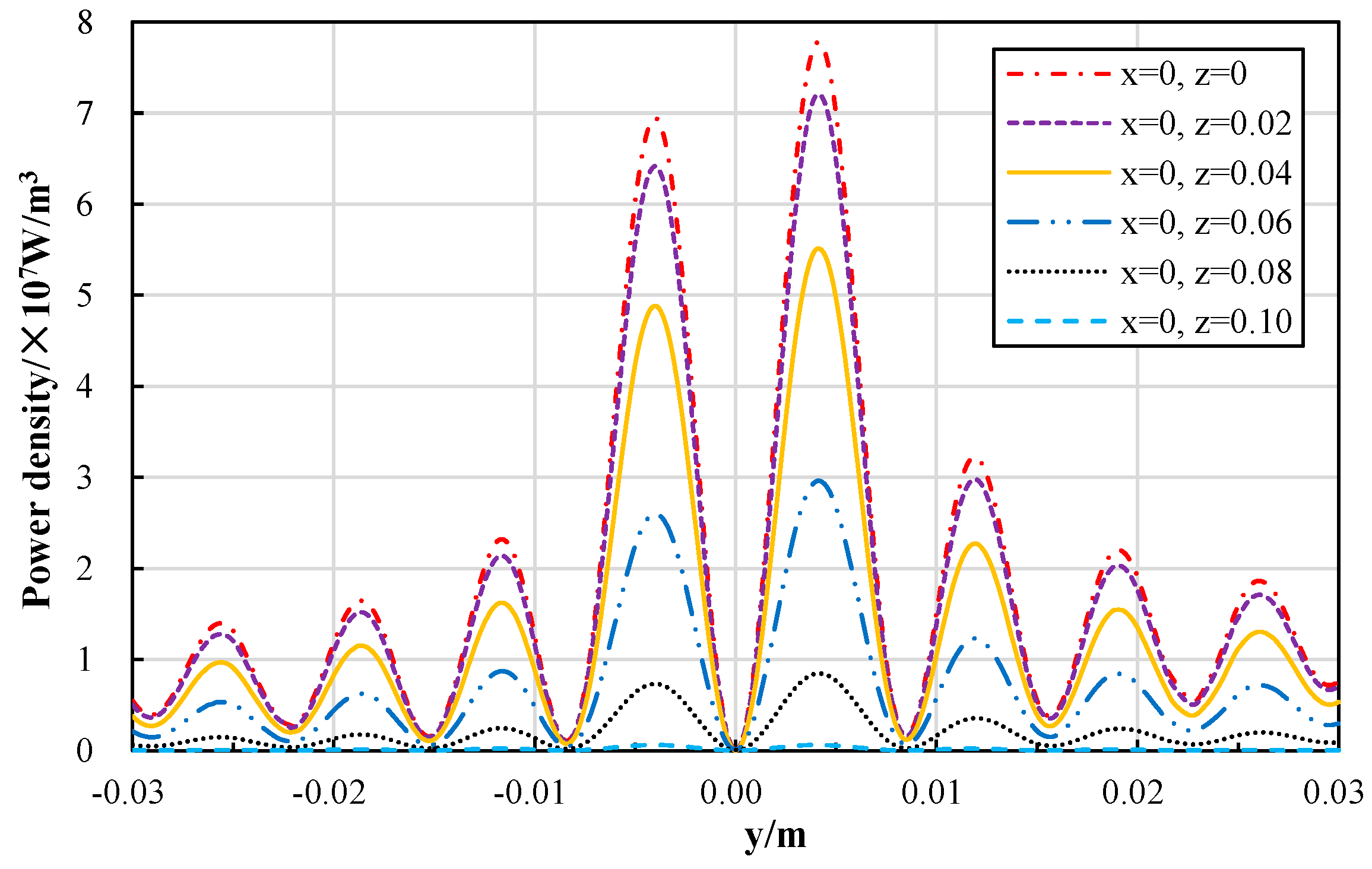

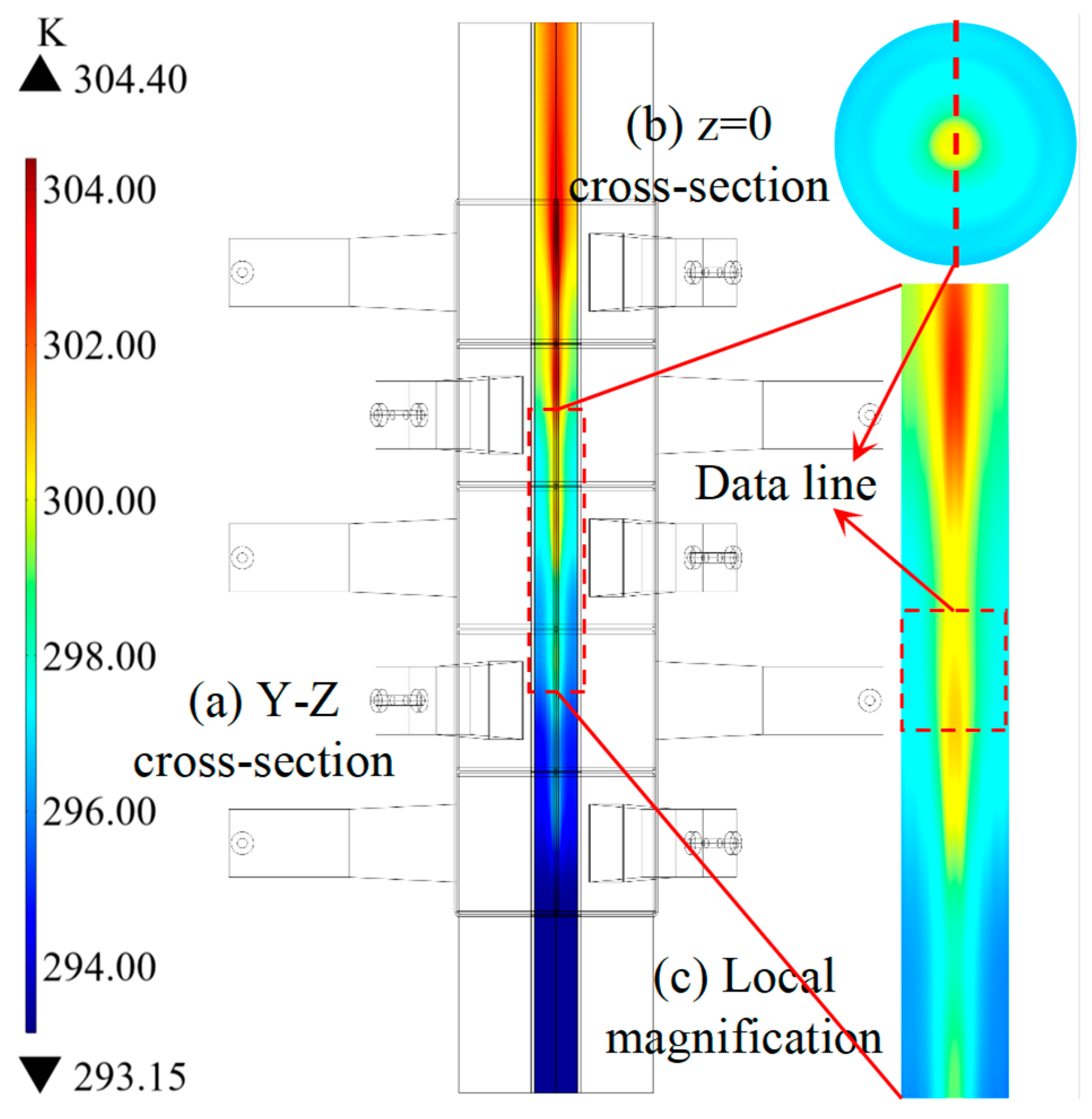

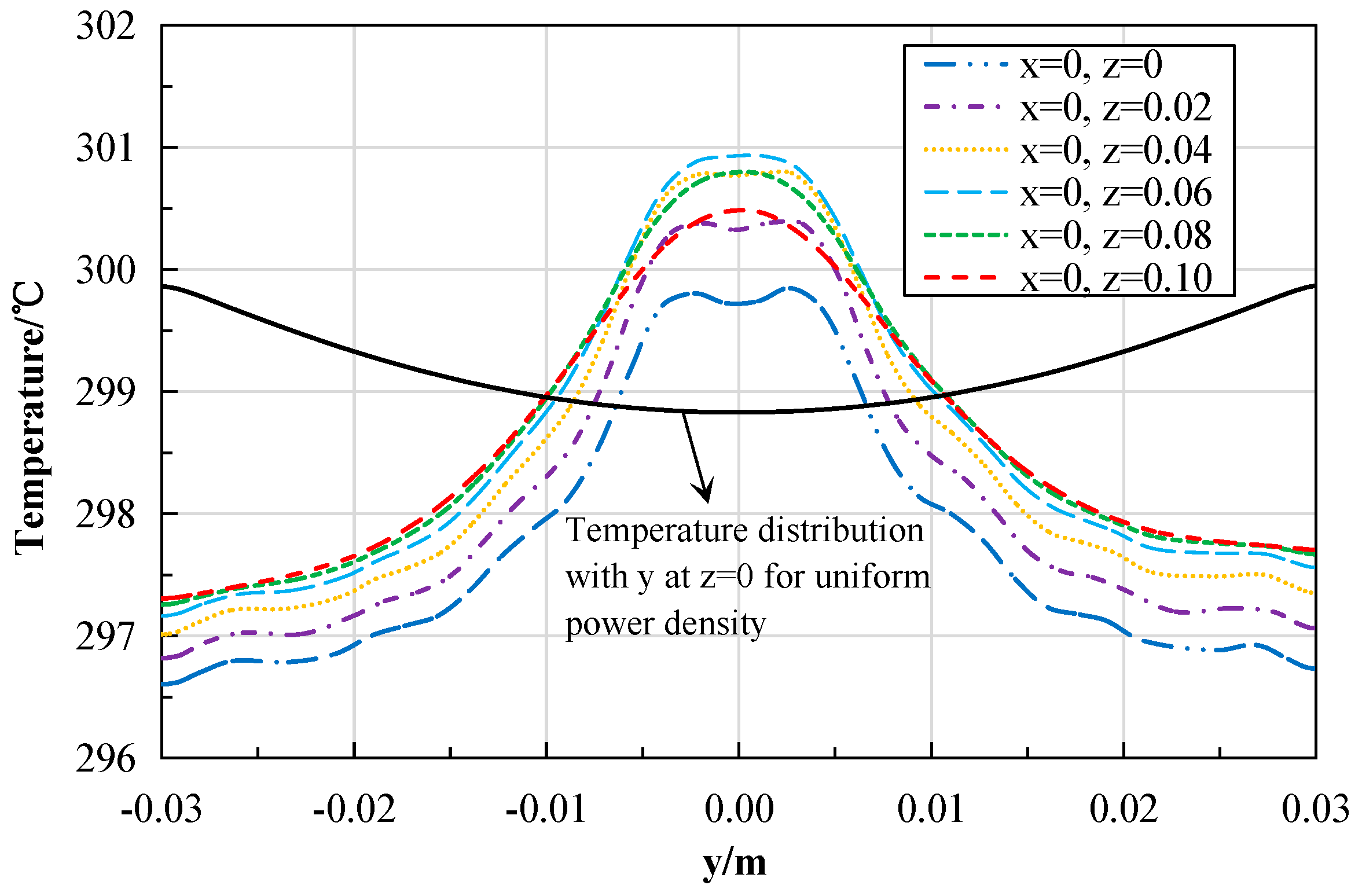

The computational geometry of the experimental setup, as illustrated in

Figure 2, comprises four primary domains: the magnetron and waveguide array, the resonant cavity with its covers, the tube, and the fluid (water). The tube is modeled as a solid domain, while the fluid domain is enclosed within it. The remaining space is defined as an air domain. The covers are essential for safety in the simulation to prevent microwave leakage through the tube openings.

Key geometric structure parameters of the model are summarized in

Table 1. The main resonant cavity has a height of 1 m and is internally subdivided into five relatively independent sub-cavities. Each sub-cavity incorporates three magnetron-waveguide units arranged at 120-degree intervals. Notably, these units are staggered by 60 degrees between adjacent layers. This staggered configuration is implemented to improve the axial uniformity of the power deposition profile along the flow direction. The mechanism involves averaging out the inherent symmetric power pattern of each sub-cavity by rotating it in adjacent layers, thereby preventing the constructive superposition of local non-uniformities. Consequently, a more homogenized heating profile within the fluid can be achieved. All the edges inside the cavity are chamfered with a radius of 5 mm.

3.2. Mathematical Model

The heating process of flowing water within a microwave cavity involves multiphysics computations, encompassing electromagnetic wave propagation, heat transfer, and fluid flow. This is governed by Maxwell’s equations, Fourier’s energy equation, and the Navier–Stokes equations.

In the microwave cavity, water molecules oscillate rapidly under the influence of the electromagnetic field. However, due to microwave attenuation and reflection, the electromagnetic field distribution is non-uniform. Therefore, determining this distribution is the primary step. Maxwell’s equations are solved to compute the electromagnetic field intensity

within the waveguides, cavity, and water, as expressed in Equation (1):

where

is the relative permeability, ∇ represents the gradient operator,

E is the electric field strength,

is the relative permittivity,

is the conductivity,

is the angular frequency,

is the permittivity in vacuum, while

represents the number of waves in free space.

The resulting electromagnetic power dissipation density, which serves as the volumetric heat source, is then calculated by Equation (2):

where

denotes the imaginary part of the relative permittivity.

A perfect electric conductor boundary condition is applied on the outer surfaces of the system, as defined in Equation (3):

where

n represents the normal vector at the interface.

The heat generated by electromagnetic dissipation is transferred according to Fourier’s energy equation, given by Equation (4):

where

k is the thermal conductivity (W/(m·K)),

T is the temperature (K),

ρ is the density (kg/m

3),

Cp is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (J/(kg·K)), and

Qe is the heat source (W). The initial temperature of the water is set to 293.15 K.

In this study, the deionized water flow is modeled as an incompressible Newtonian fluid. The flow in the tube is turbulent, with a Reynolds number of approximately 14,000. The mass conservation and Navier–Stokes equations are employed to describe the fluid flow, as shown in Equations (5) and (6), respectively:

where

is the dynamic viscosity (Pa·s),

u is the velocity vector (m/s),

I is the dimensionless identity matrix,

p is the hydrodynamic pressure (Pa), and

F represents the body force vector (N/m

3). A no-slip boundary condition is applied at the inner wall of the tube, and the pressure is set to atmospheric. The outlet is controlled with a backflow suppression and pressure outlet condition.

3.3. Boundary Conditions and Numerical Setup

Current simulations, performed with water, represent a necessary first step in validating the core design concept and analyzing the fundamental interplay between microwave power deposition, geometry, and resulting temperature fields. The main materials used in the experimental setup include water, a quartz tube, and stainless steel. Their thermophysical properties, such as thermal conductivity, dynamic viscosity, specific heat capacity, and density, vary with temperature. The key parameters adopted in the simulation are provided in

Table 2. The temperature-dependent correlations for the density, heat capacity, dynamic viscosity, and thermal conductivity of water are sourced from the COMSOL Multiphysics built-in material library, valid within the range of 273–373 K. The relative permittivity (

= 78,

= 8) for water is taken from literature [

22] and corresponds to a reference temperature of 298.15 K. Given the simulated bulk temperature rise is moderate (~8 K), the dielectric properties are treated as constant, which is a reasonable simplification for this scoping study. These values facilitate a more accurate analysis and modeling of the heating behavior of deionized water inside the designed microwave cavity.

The flow was modeled as turbulent using the standard k − ε turbulence model with standard wall functions. This approach offers robust convergence for the current analysis, focusing on bulk flow and thermal development. To adequately resolve the near-wall region for potential future heat transfer analysis, a three-layer boundary layer mesh was applied. At the inlet, a fully developed turbulent velocity profile corresponding to the mean velocity of 0.2 m/s was prescribed. The turbulence at the inlet was specified with a medium intensity of 5% and a length scale equal to the hydraulic diameter of the pipe. This configuration aims to minimize inlet effects and the influence of potential mixed convection. The input power of each magnetron was set to its rated value of 1.5 kW. The volumetric heat source term derived from the electromagnetic simulations was applied to simulate microwave heating in the coupled multiphysics computation.

3.4. Grid Independence Verification

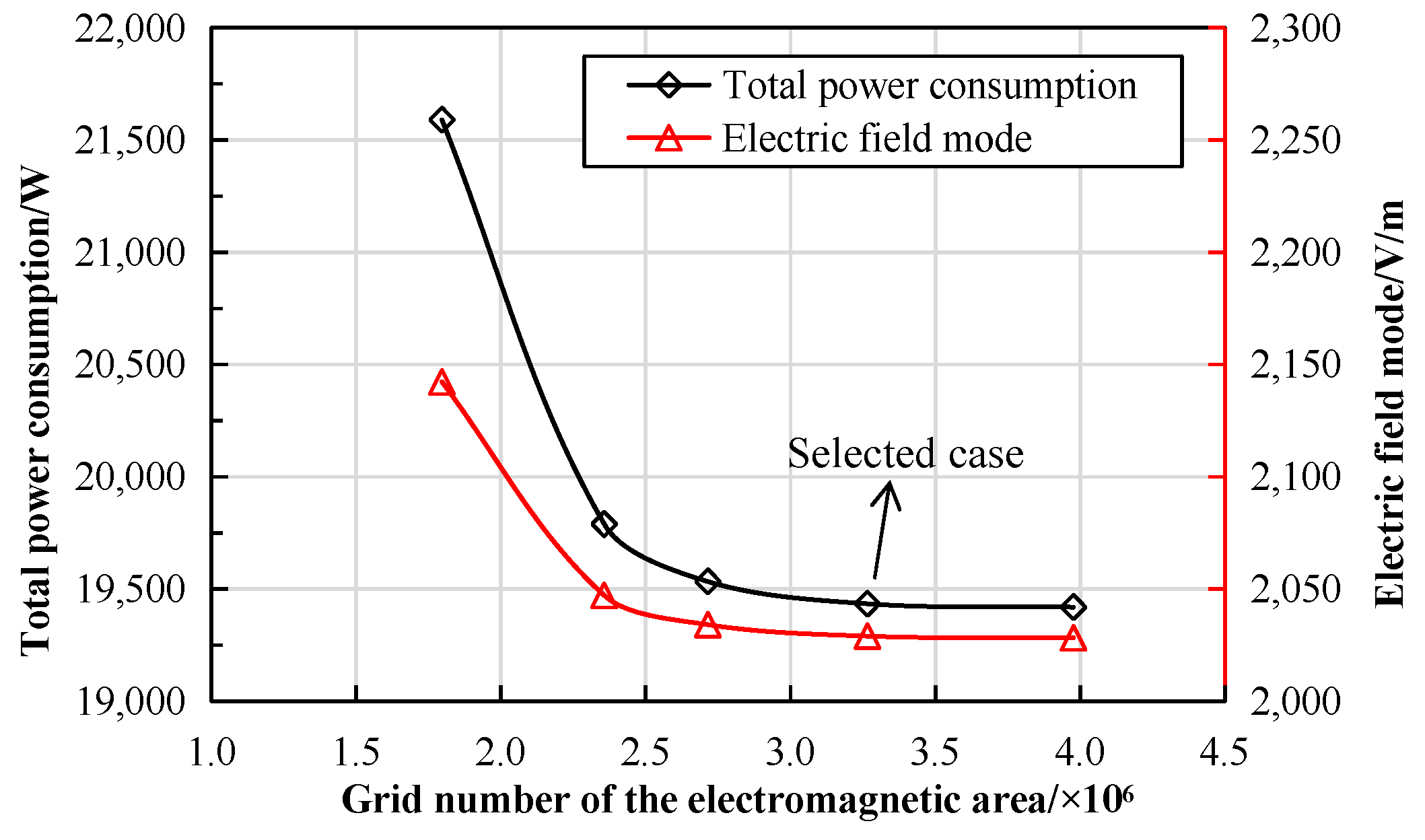

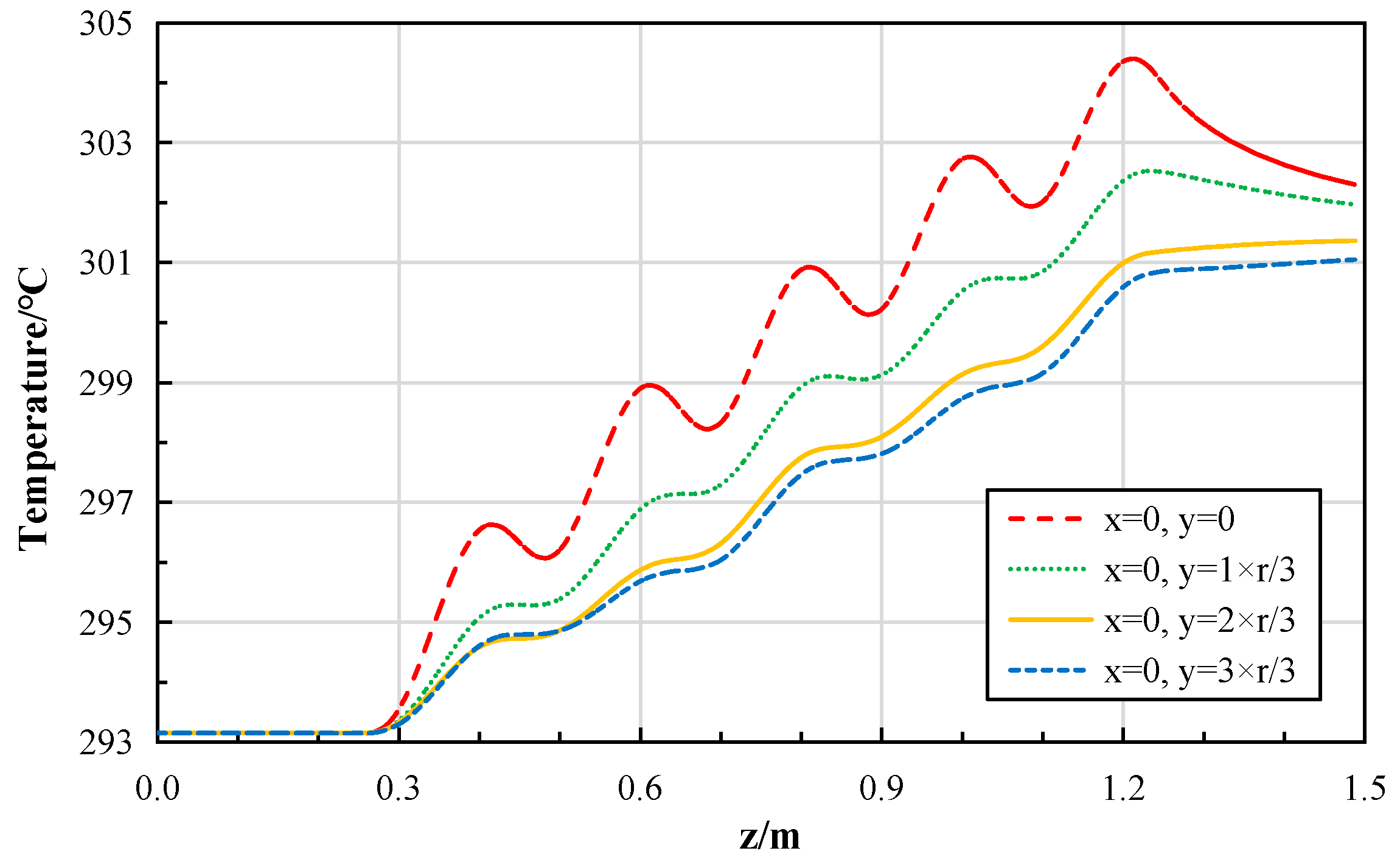

Numerical accuracy and computational cost are strongly influenced by mesh quality and resolution. To ensure sufficient computational precision while maintaining reasonable cost, a comprehensive grid independence study was conducted. This study was performed in two sequential phases: first, for the electromagnetic field simulation alone, and then for the fully coupled electromagnetic-thermal-fluid model. As shown in

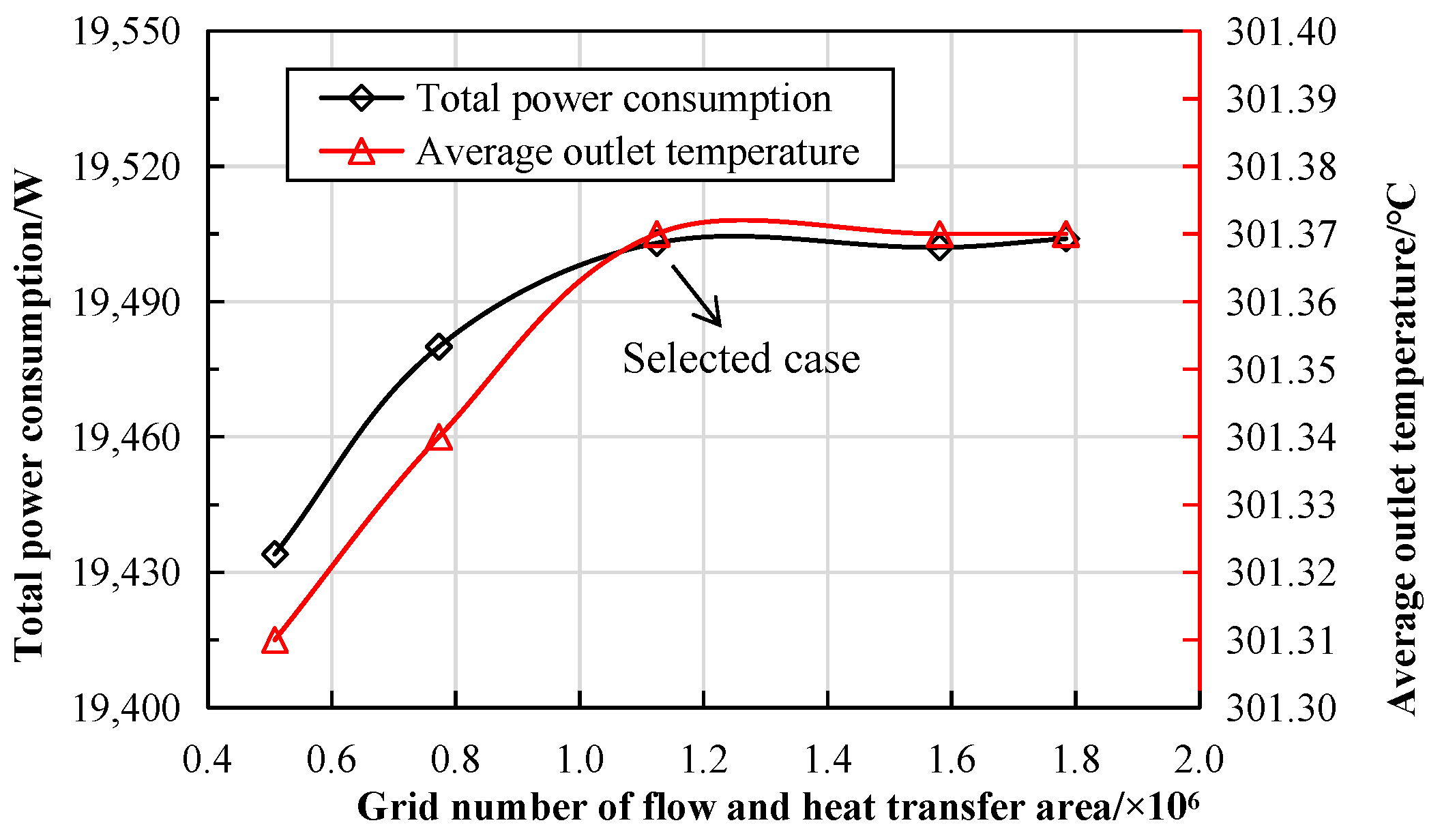

Figure 3, the relative changes in both total power dissipation and the electric field norm diminish as the number of elements in the electromagnetic domain increases. Based on this result, a mesh configuration from the plateau region of these curves was selected for the electromagnetic domain. Subsequently, this selected electromagnetic mesh was retained, and the fluid domain mesh was refined. A three-layer boundary layer mesh (with a growth factor of 1.2) was applied near the tube walls to better capture gradients, and the rest of the fluid domain was further refined.

Figure 4 demonstrates that the relative changes in total power dissipation and outlet mean temperature become negligible with further refinement of the fluid mesh. Integrating the results from both stages of the grid independence analysis, the final mesh configuration, comprising approximately 4.94 million elements in total, was selected for all subsequent results and discussions.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented the conceptual design and numerical validation of an innovative microwave-based system for generating a volumetric heat source in fluids, specifically targeting thermal-hydraulic experiments relevant to liquid-fueled molten salt reactors. The comprehensive multi-physics simulations lead to the following key conclusions:

First, the proposed design, centered around a hexagonal resonant cavity with a multi-tier staggered magnetron array, is numerically demonstrated to be effective. It can generate a high-power-density internal heat source, with an average power density exceeding 6.9 MW/m3, which meets and can be scaled beyond the requirements for simulating MSR fuel salt conditions. Second, a detailed quantitative analysis was conducted using uniformity metrics such as the Coefficient of Variation (COV) and the Max/Min ratio. The results clearly delineate the inherent non-uniformity in microwave power deposition and quantify how turbulent convective flow mitigates this non-uniformity in the temperature field. Third, and most significantly, the study identifies and validates channel geometry as a critical and effective design parameter for managing heating uniformity. By adapting the flow channel cross-section (e.g., reducing the tube diameter or employing an annulus), the temperature uniformity can be drastically improved, achieving a near-uniform thermal field in the annulus case, as evidenced by a temperature COV of less than 0.01. This strategy provides a practical solution to a central challenge in applying microwave heating to controlled convection experiments. Finally, the work discusses the applicability and current limitations regarding the use of water as a simulant fluid and outlines the necessary steps, such as measuring molten salt dielectric properties, to extend this method to direct MSR-relevant experiments.

Future work will primarily focus on the construction and experimental testing of a prototype based on this design to validate the numerical predictions. Concurrently, efforts will be directed towards measuring the complex permittivity of candidate molten salts to enable accurate fluid-specific simulations. The validated experimental platform will then be employed for detailed separate-effect studies, systematically evaluating the impact of a non-uniform volumetric heat source on both forced and natural convection heat transfer processes. These steps are essential for transforming this promising numerical concept into a robust tool for advancing the fundamental understanding of heat transfer in internally heated fluids, with direct implications for next-generation reactor technology.