A Review on Near-Field and Far-Field Wireless Power Transfer Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

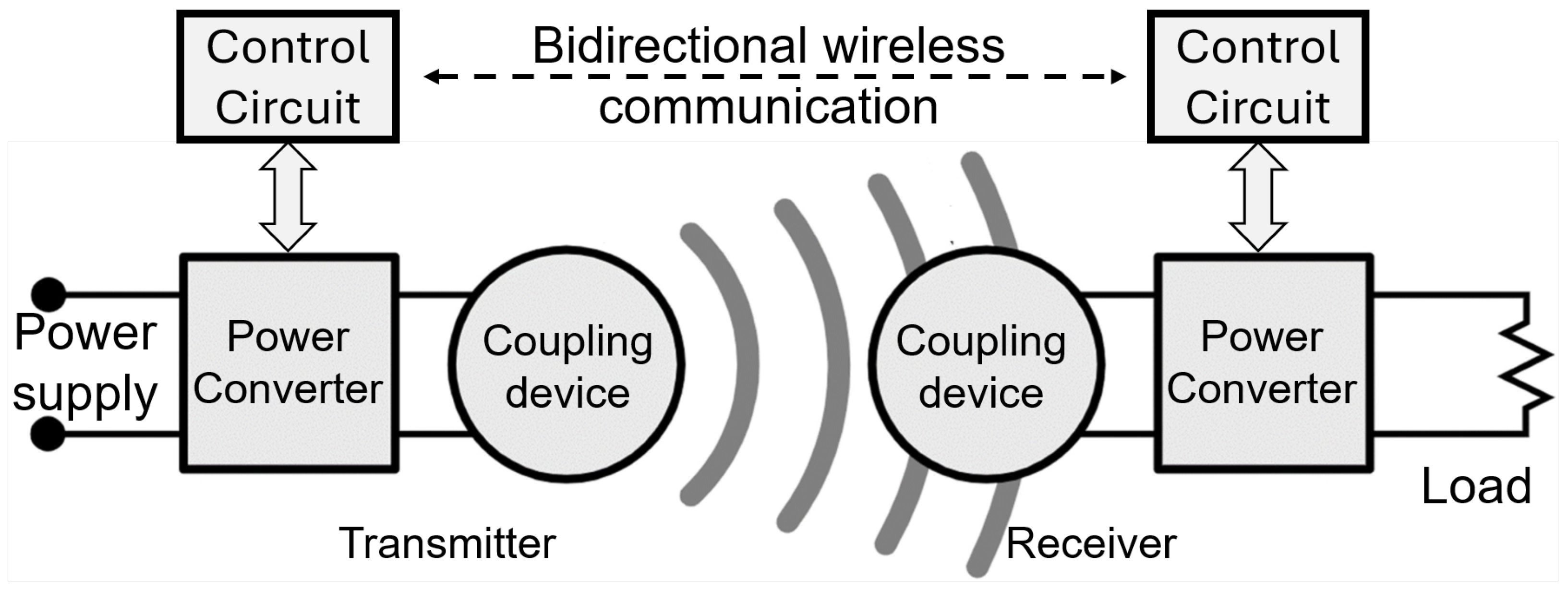

1.2. Wireless Power Transfer in Modern Systems

1.3. Historical Development

1.4. Contributions and Justification of Novelty

- A Novel Classification Framework: Unlike traditional taxonomies that classify solely by frequency, our framework (presented in Section 2) categorizes WPT systems by operational logic, integrating emerging technologies such as AI-optimized adaptive tuning and Parity–Time (PT) symmetric (Quantum) transfer.

- Holistic Technical Comparison: We provide a critical analysis of the design trade-offs between Inductive Power Transfer (IPT) and Capacitive Power Transfer (CPT), specifically addressing voltage stress, misalignment tolerance, and safety compliance.

- Economic and Regulatory Analysis: Beyond the physics, this review evaluates the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) for WPT deployment in automotive and industrial sectors and summarizes the current regulatory landscape (ICNIRP, IEEE) regarding human safety.

- Forward-Looking Research Gaps: We identify specific bottlenecks in current technology, particularly the efficiency limitations of far-field systems and the standardization needs for dynamic EV charging.

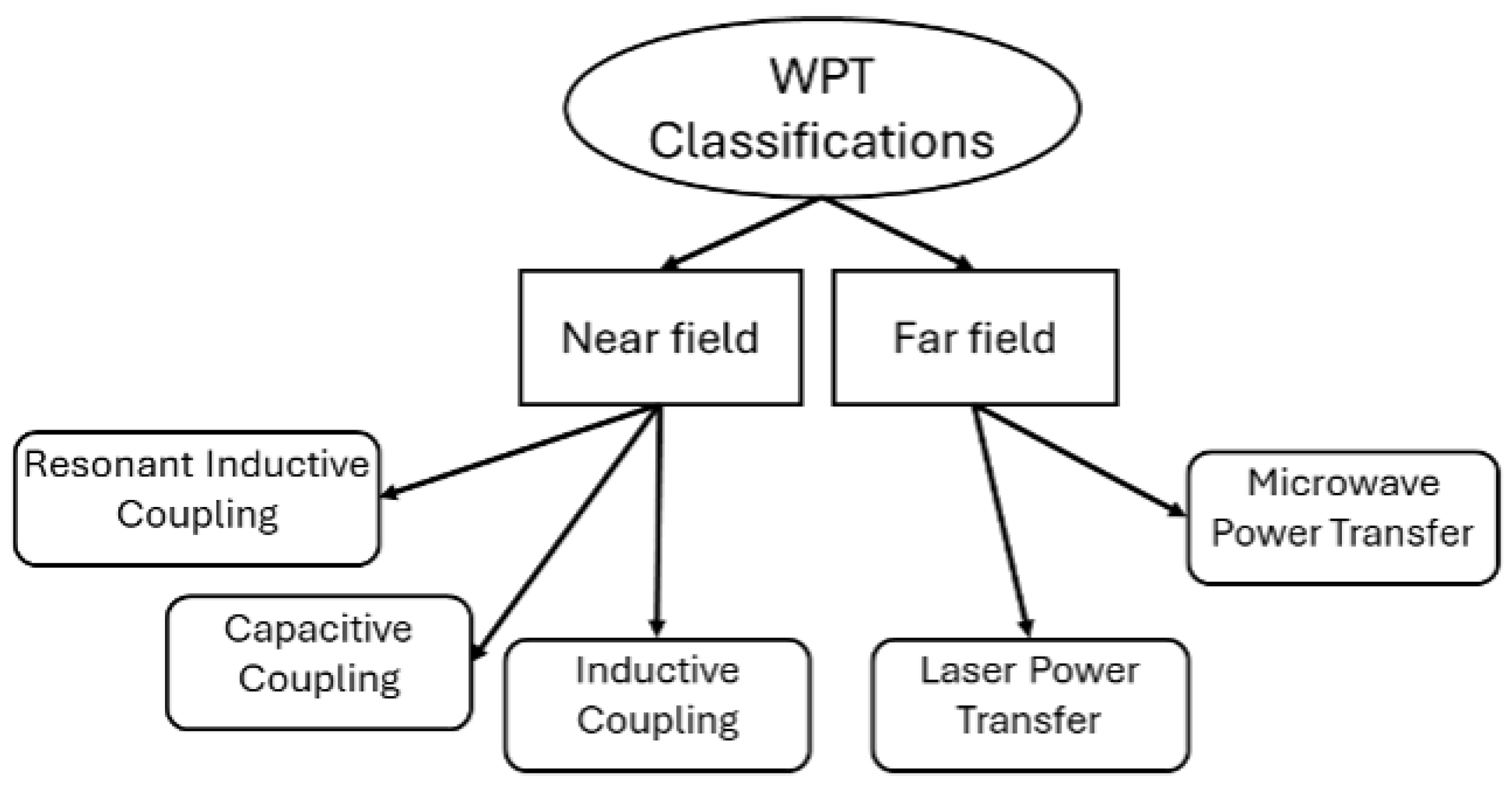

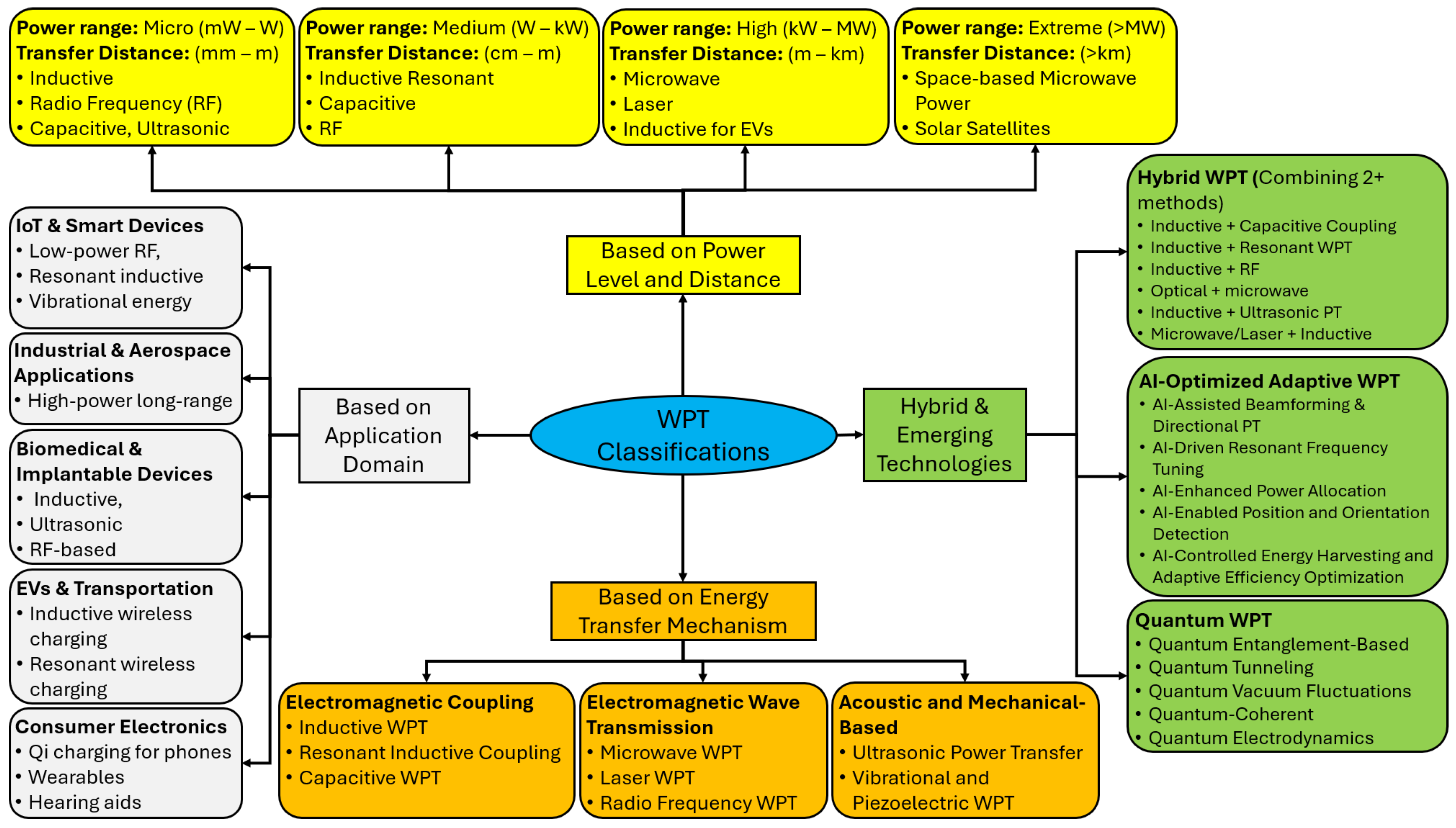

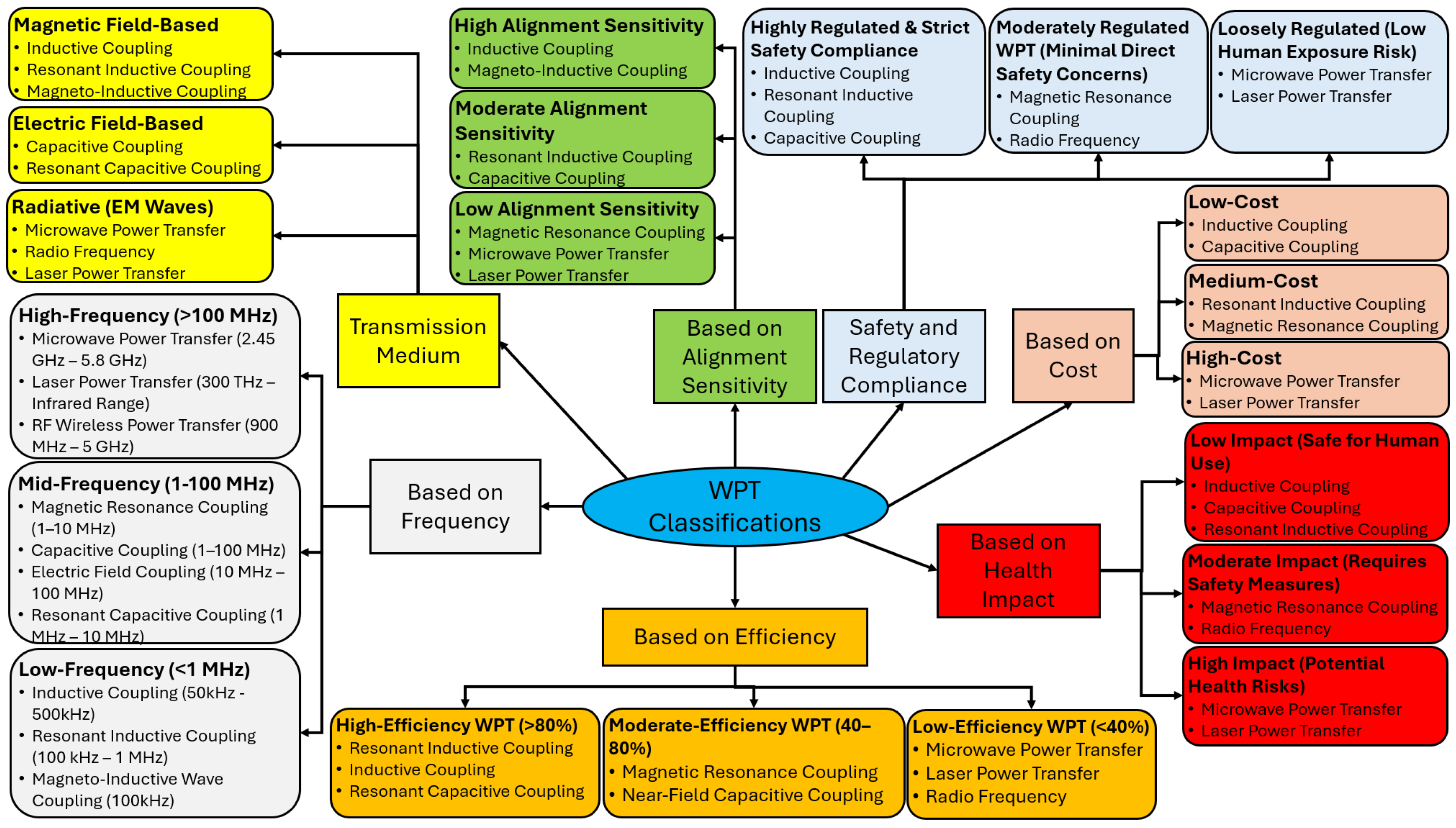

2. Classifications of WPT

2.1. Classical Classifications of WPT

2.2. Novel Classifications of WPT

3. Near-Field and Far-Field WPT Technologies

3.1. Near-Field WPT (Non-Radiative)

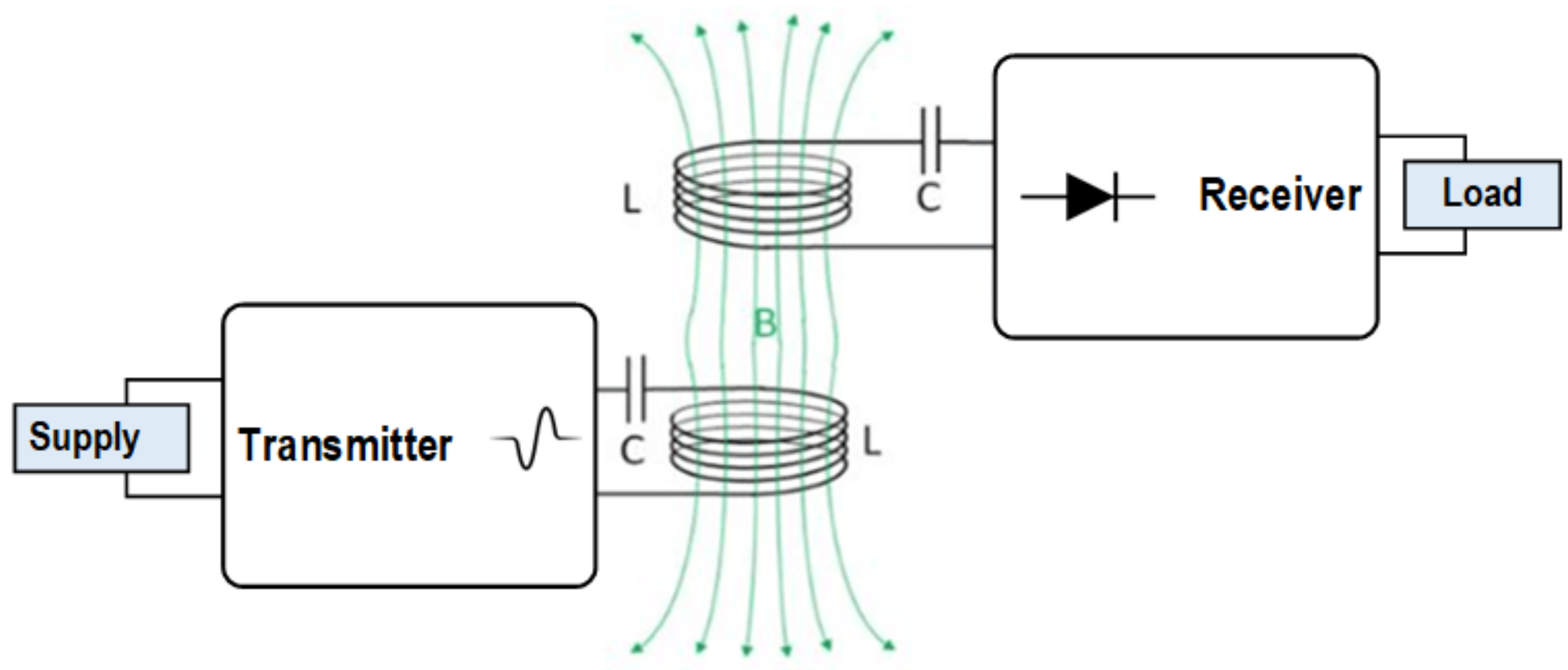

3.1.1. Inductive Coupling Power Transfer (IPT)

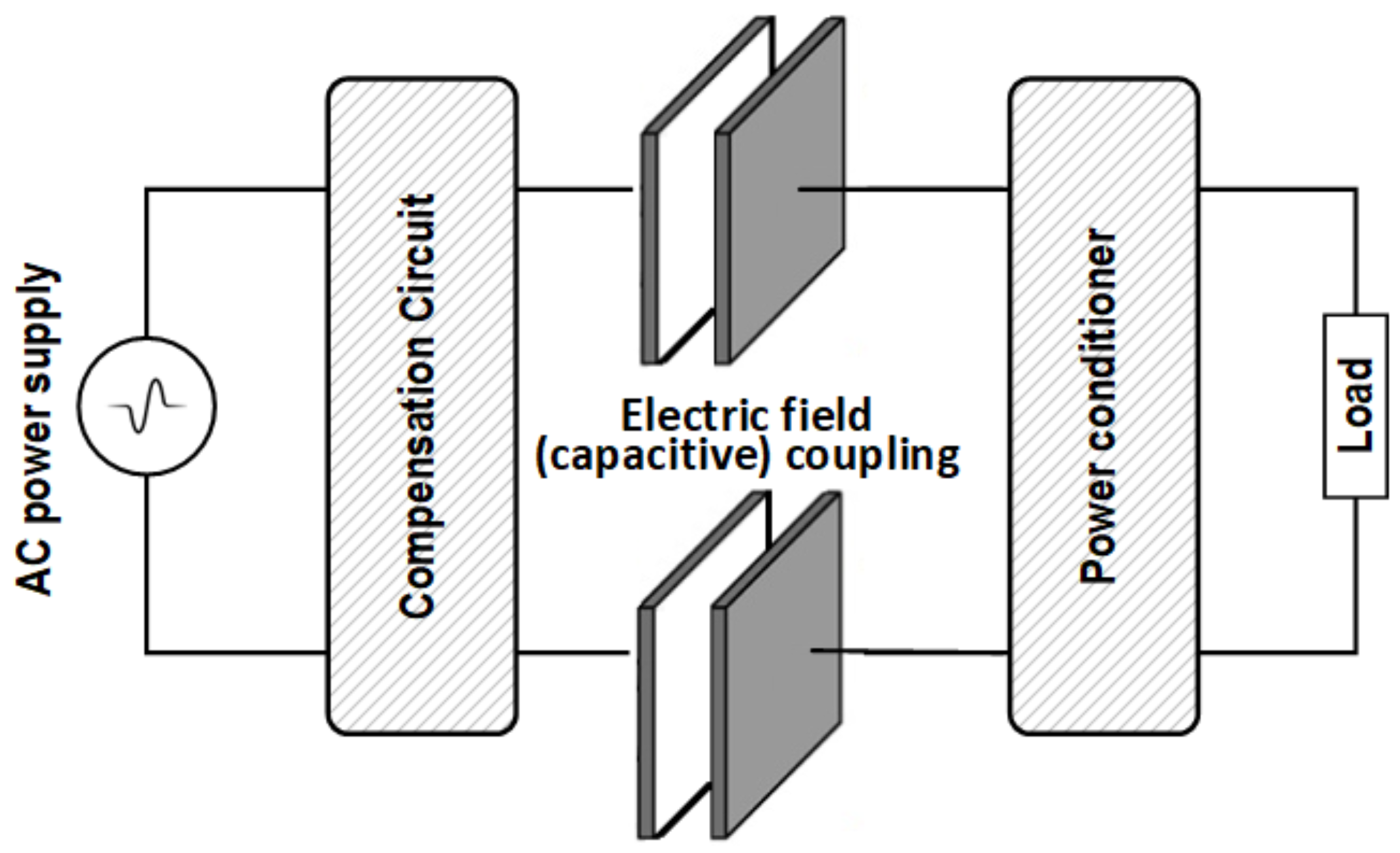

3.1.2. Capacitive Coupling Power Transfer (CPT)

- High Frequencies: Typically in the MHz range (1 MHz–13.56 MHz) to lower the reactance.

- High Voltages: Utilizing step-up transformers or resonant networks to generate kilovolts (kV) across the plates [40].

| Air Gap (mm) | Topology | Power (W) | Freq. (f) | Efficiency () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 180 | LC–LC | 150 | 1.5 MHz | 66.7% [44] |

| 2000 | LC–LC | 216.5 | 1 MHz | 52.2% [45] |

| 150 | LCL-LCL | 1880 | 1 MHz | 85.9% [46] |

| <10 | Modified LLC | 1000 | 250 kHz | 94.0% [47] |

| 110 | Series L | 350 | 6.78 MHz | 70.0% [48] |

| 150 | CLLC-CLLC | 2570 | 1 MHz | 89.3% [49] |

| 150 | LCLC-LCLC | 2400 | 1 MHz | 90.8% [50] |

3.1.3. Comparative Analysis and Design Trade-Offs: IPT vs. CPT

- Advantages: IPT offers high power density and is capable of transferring kilowatts at relatively low frequencies (85 kHz–140 kHz). It is the dominant standard (Qi, SAE J2954 [52]).

- Limitations: The primary drawback of IPT is the generation of eddy currents in foreign metallic objects (coins, keys), necessitating complex Foreign Object Detection (FOD). Furthermore, IPT systems utilize heavy ferrite cores [45].

- Limitations: The primary challenge in CPT is the “Voltage Stress” limitation. Because the coupling capacitance across an air gap is typically very small, the reactance is high, often requiring LC-compensation networks to achieve resonance [48,49]. This introduces safety concerns regarding dielectric breakdown (arcing).

3.2. Far-Field WPT (Radiative)

- High Directivity: Using phased array antennas (for microwaves) or collimated optics (for lasers) to focus the energy into a narrow beam.

- High Frequency: Increasing the frequency (f) allows for smaller transmission apertures, as the beam diffraction is proportional to .

- Laser Power Transfer (LPT): Operates in the optical spectrum (THz range). LPT offers extremely high power density and compact apertures due to the nanometer-scale wavelength but is strictly limited by Line-of-Sight (LoS) requirements and atmospheric attenuation.

- Microwave Power Transfer (MPT): Operates in the Radio Frequency (RF) spectrum (typically 2.45 GHz or 5.8 GHz ISM bands). MPT can penetrate atmospheric conditions like clouds and rain but requires large rectenna arrays to harvest the diffracted beam.

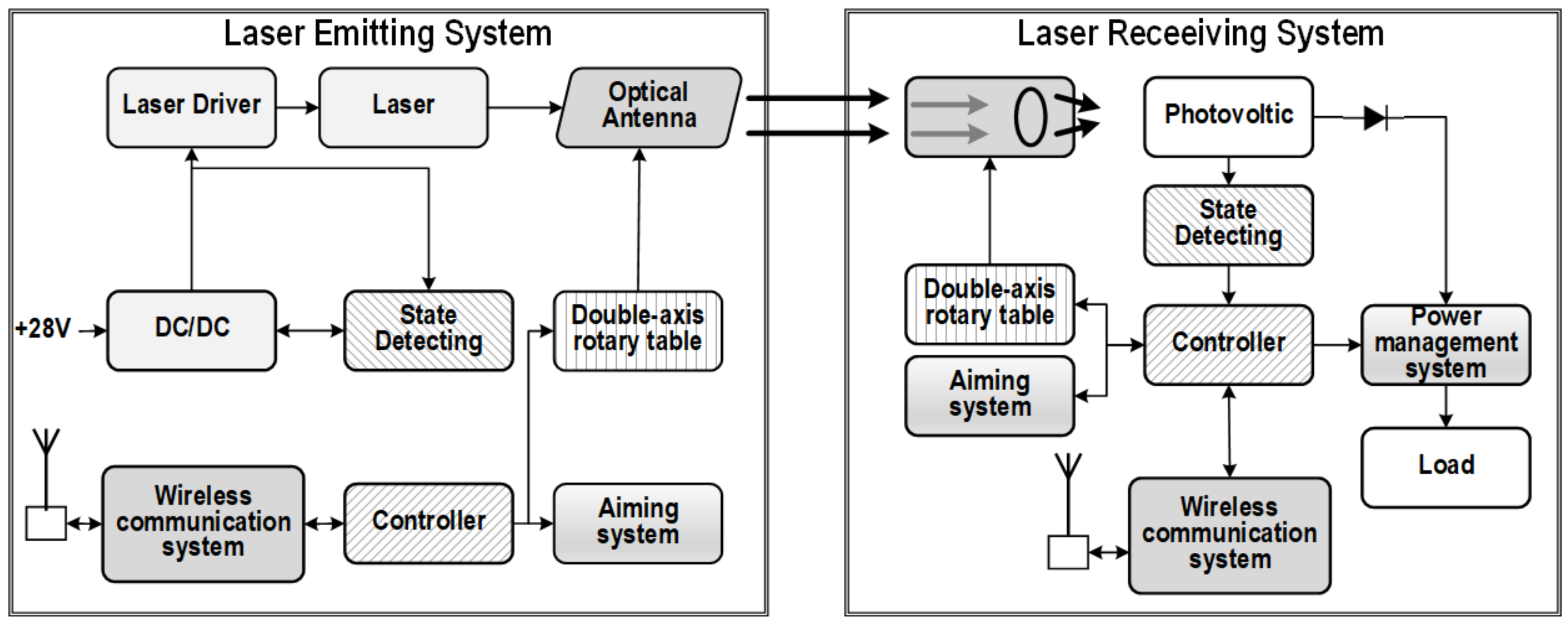

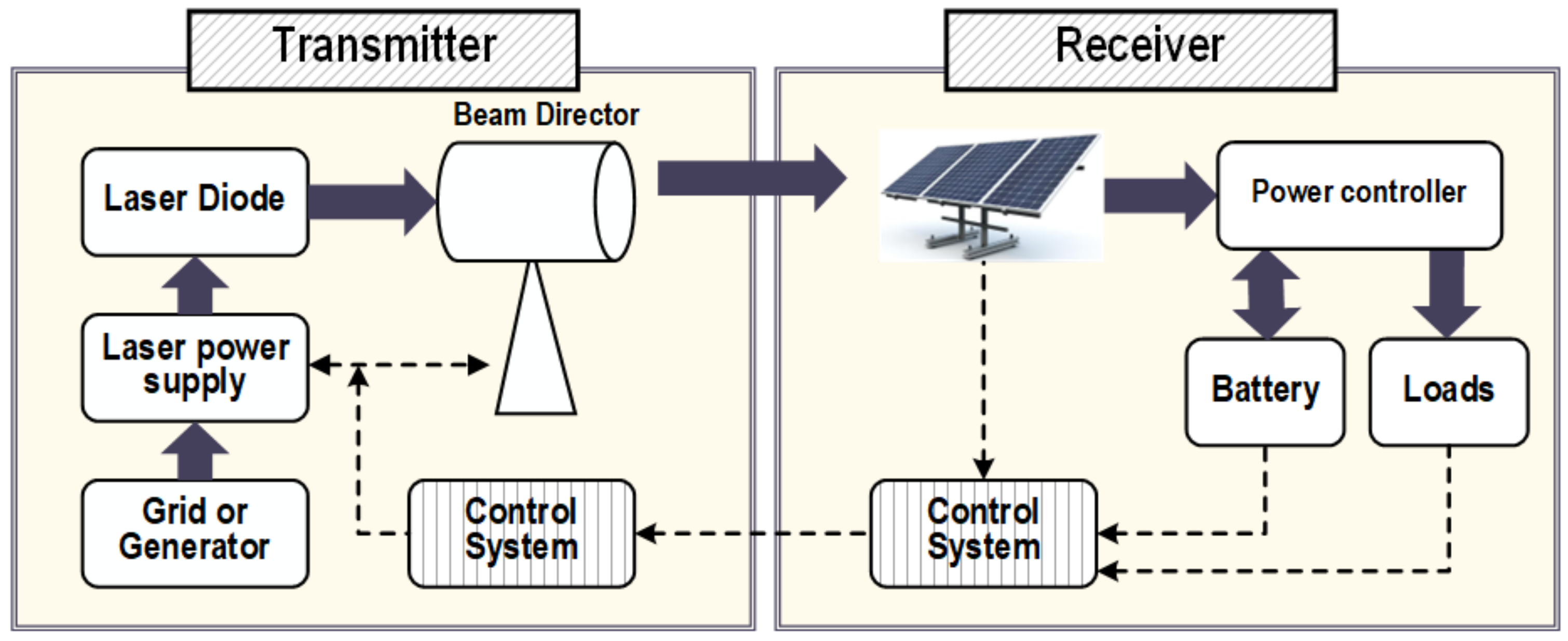

3.2.1. Laser Power Transfer (LPT)

- Laser Source: High-power laser diodes or fiber lasers convert DC power into a coherent beam. While modern solid-state lasers have improved, the “wall-plug efficiency” () typically remains between 40% and 60%, representing a significant thermal management challenge.

- Transmission Medium: Unlike RF waves, laser beams are tightly collimated, minimizing diffraction losses over distance. However, they are highly susceptible to atmospheric attenuation caused by scattering (fog, dust) and absorption (rain), which degrades in outdoor environments.

- PV Receiver: Standard silicon solar cells are inefficient for LPT because they are designed for the broad solar spectrum. High-efficiency LPT systems utilize **monochromatic PV cells** (e.g., Gallium Arsenide—GaAs) tuned specifically to the laser’s wavelength, achieving conversion efficiencies () of 40–60% [57,58].

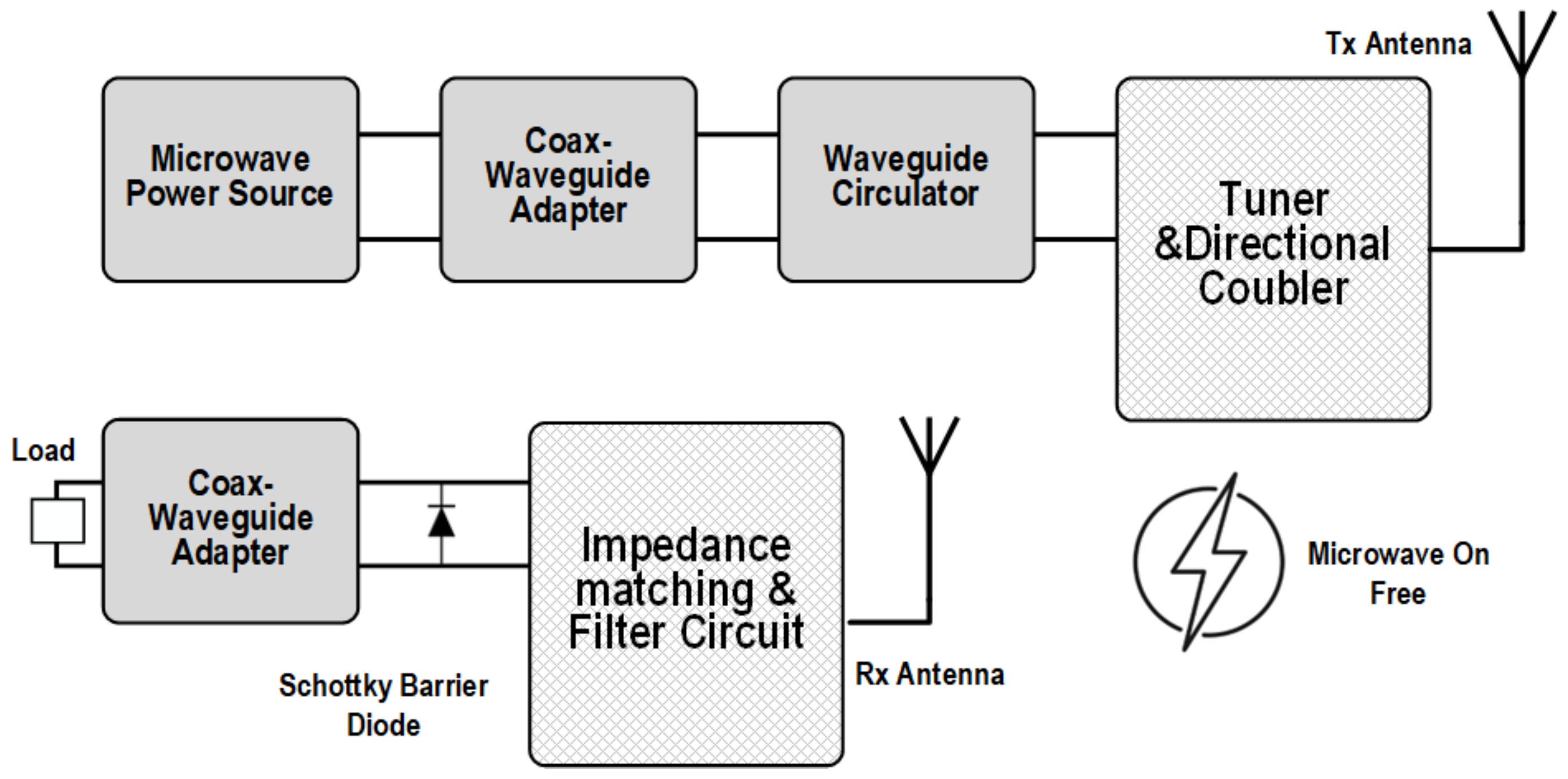

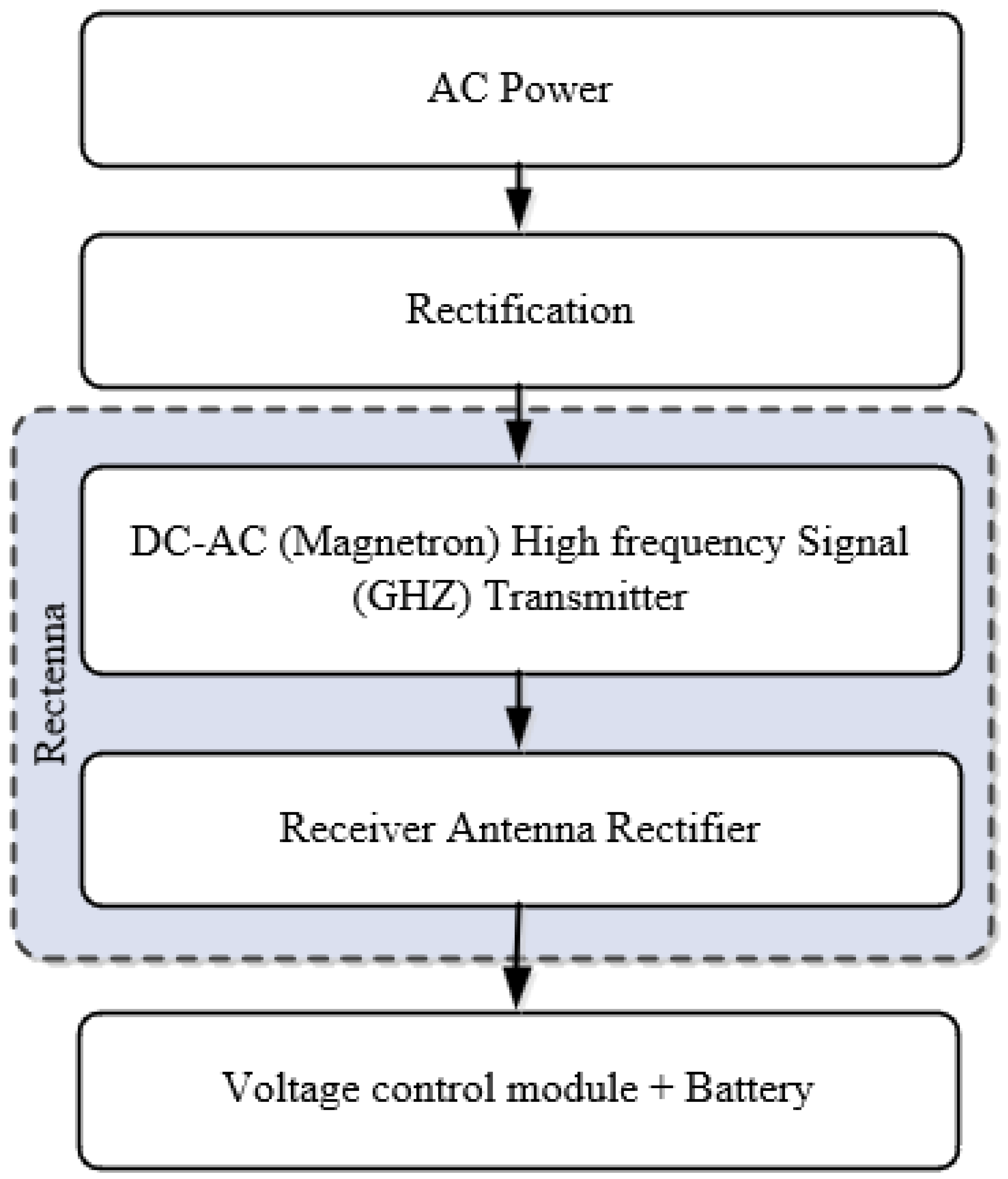

3.2.2. Microwave Power Transfer (MPT)

- Lower Frequencies (e.g., 2.45 GHz): Offer lower atmospheric attenuation and cheaper components but require massive transmission apertures to maintain a focused beam (due to the diffraction limit).

- Higher Frequencies (e.g., 35 GHz–94 GHz): Allow for compact antennas suitable for drones or satellites but suffer from higher switching losses and atmospheric absorption (rain fade) [72].

3.3. Comparison and Selection Criteria: Near-Field vs. Far-Field

- Reactive Near-Field (): Energy is stored in the magnetic or electric field and oscillates between the source and load without radiating into space. This regime (IPT/CPT) allows for high efficiency (>90%) but requires the receiver to be within the “bubble” of stored energy. Field strength decays rapidly at [81].

- Radiative Far-Field (): Energy detaches from the source and propagates as electromagnetic waves. This regime (MPT/LPT) enables long-range transmission but is governed by the Inverse Square Law (), leading to significant path loss unless highly directive beamforming is employed.

3.4. Emerging and Hybrid WPT Classifications

3.4.1. Acoustic and Ultrasonic Power Transfer (UPT)

- Mechanism: The system utilizes piezoelectric transducers (typically PZT ceramics) to convert electrical energy into ultrasonic waves. These waves propagate through a medium (tissue, water, or metal walls) and are reconverted into electricity by a receiver transducer via the direct piezoelectric effect.

- Scientific Advantage: The speed of sound in tissue (≈1540 m/s) is orders of magnitude slower than the speed of light. Consequently, the wavelength () at 1 MHz is roughly 1.5 mm. This allows for the design of millimeter-scale receivers that are highly efficient, whereas an RF antenna at 1 MHz would be meters long. This physics makes UPT dominant for deep-tissue biomedical implants where EM waves are absorbed [82,83,84].

3.4.2. AI-Optimized and Adaptive WPT

- Mechanism: AI-Optimized WPT employs Machine Learning algorithms, specifically Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). These algorithms monitor the input voltage/current waveforms and dynamically tune the variable capacitors in the Impedance Matching Network (IMN).

- Added Value: Unlike look-up tables, AI agents can “predict” the trajectory of an EV or drone, pre-tuning the circuit to maintain Zero Voltage Switching (ZVS) and peak efficiency before the misalignment event occurs [85].

3.4.3. Quantum-Inspired (PT-Symmetric) WPT

- Mechanism: A PT-symmetric system consists of two coupled resonators: one with active gain (negative resistance via operational amplifiers) and one with loss (the load).

- The Physics of “Locking”: Unlike standard resonant coupling where efficiency drops sharply if the distance changes, a PT-symmetric system enters a “broken phase” where the operating frequency automatically splits to match the distance. This allows the system to maintain constant, high efficiency over a varying range without manual frequency tuning or complex feedback loops, theoretically solving the distance-sensitivity problem of magnetic resonance [86].

3.4.4. Quantum and PT-Symmetric WPT

4. Applications of WPT

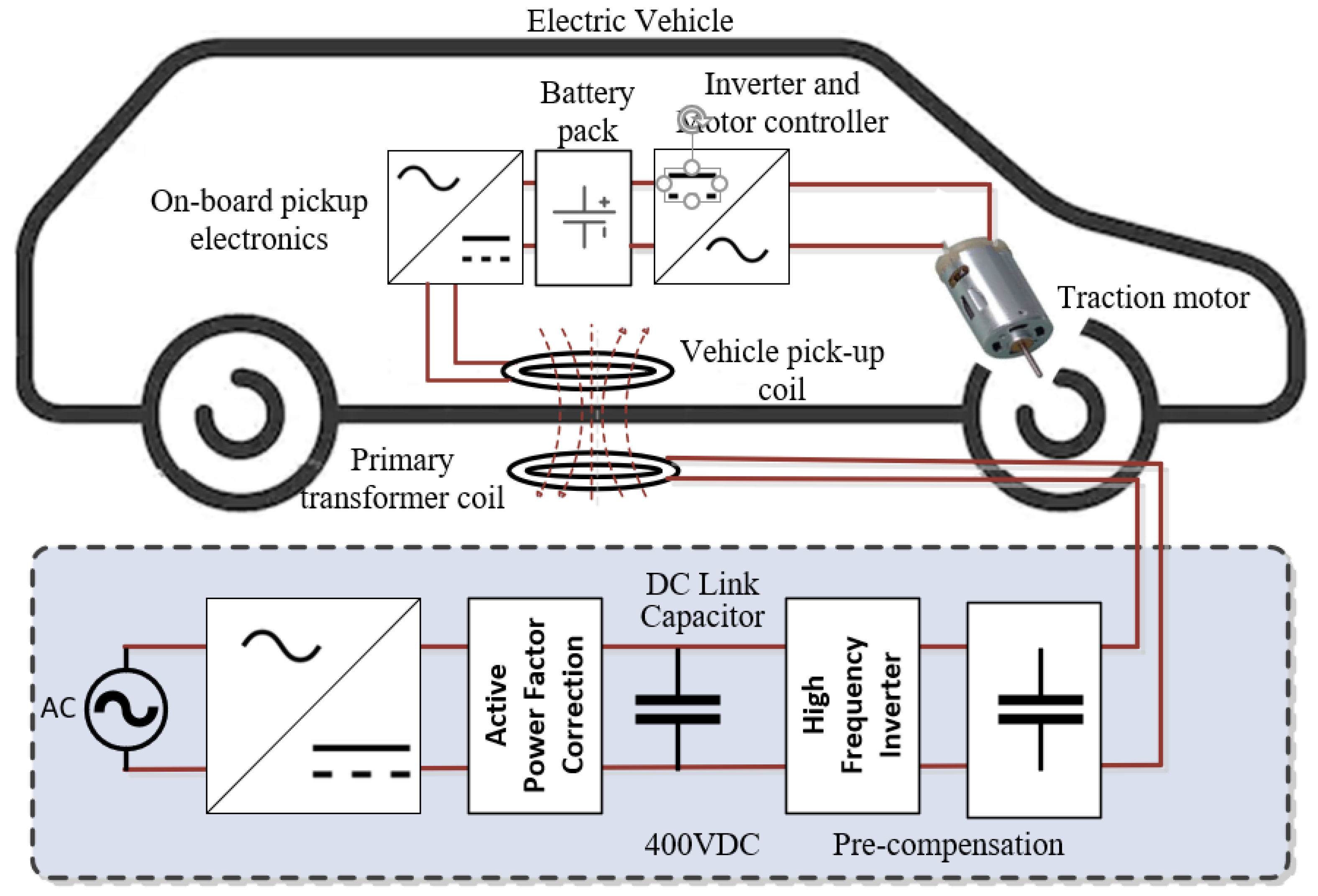

4.1. Automotive Sector (EV Charging)

- Stationary Charging: Governed by the SAE J2954 standard, this technology utilizes resonant inductive coupling at 85 kHz. Systems typically operate at power levels of 3.7 kW (WPT1), 7.7 kW (WPT2), and 11 kW (WPT3), with efficiencies exceeding 90% at air gaps of 100–250 mm. The primary engineering benefit is the facilitation of Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) integration without user intervention, as illustrated in Figure 11.

- Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT): DWPT involves embedding transmitter coils into road infrastructure to power vehicles in motion. While this theoretically allows for infinite range and significantly smaller onboard batteries, it faces substantial challenges regarding infrastructure cost ($1.7 M/km) and the complexity of fast receiver switching between track segments [84,87,88].

4.2. Biomedical Implants and Wearables

- Implantable Devices: For high-power implants like Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVADs) or artificial hearts, Transcutaneous Energy Transfer (TET) systems transfer 5–20 W through the skin. Research focuses on optimizing coil misalignment tolerance and minimizing tissue heating (SAR) to comply with IEEE C95.1 [89] safety limits.

- Miniaturized Sensors: For deep-tissue implants (e.g., pacemakers, neural dust), ultrasonic or low-frequency inductive links are preferred to penetrate tissue with minimal attenuation. These systems eliminate the need for invasive surgical battery replacements, significantly improving patient outcomes [90,91].

4.3. Smart Home and Consumer Electronics

4.4. Wireless Powered Light Rail Vehicle (LRV)

4.5. Space-Based Solar Power (SBSP)

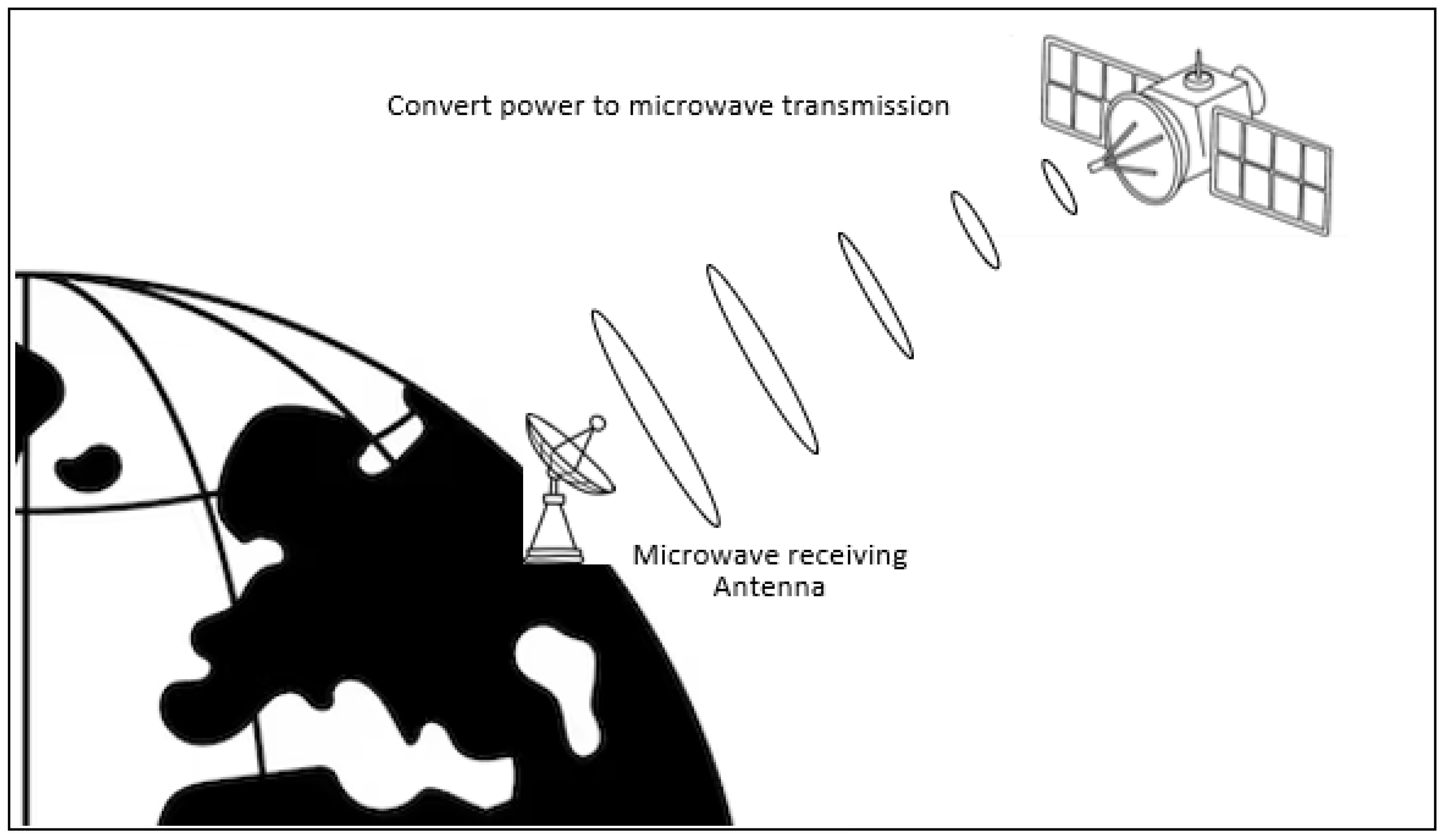

- Transmission Mechanism: As shown in Figure 12, the satellite converts DC power to RF energy, which is focused onto a ground-based “Rectenna” (Rectifying Antenna) array spanning several kilometers.

- Challenges: The primary barriers are the diffraction limit (requiring massive apertures for efficient transmission) and atmospheric attenuation. Current research focuses on improving the RF-to-DC conversion efficiency of rectennas and ensuring beam safety [93].

5. WPT Standards and Interoperability Protocols

5.1. Consumer Electronics Standards

- Qi (Inductive): Operating between 87 and 205 kHz, Qi relies on tight magnetic coupling and in-band communication (load modulation) for feedback control. It currently dominates the smartphone market, offering power profiles from 5 W (Baseline Power Profile) to 15 W (Extended Power Profile).

- Ki (Cordless Kitchen): A newer WPC standard designed for kitchen appliances (blenders, rice cookers) that delivers up to 2.2 kW using near-field induction transmitters embedded in countertops [101].

5.2. Automotive and Infrastructure Standards

- Frequency: A unified operating band at **85 kHz** (81.38–90 kHz) to minimize interference with automotive key fobs and AM radio.

- Power Classes: Defined levels including WPT1 (3.7 kW), WPT2 (7.7 kW), and WPT3 (11 kW), with future extensions for heavy-duty vehicles (WPT4 at 22 kW+).

- Z-Classes (Air Gap): Standards define vertical operating gaps ranging from Z1 (100–150 mm) for sports cars to Z3 (170–250 mm) for SUVs.

6. Analysis of Economic Factors and Policy Implications

6.1. Automotive Sector: The TCO Divergence

- Private Passenger Vehicles (The Convenience Premium): For consumer EVs, WPT is currently a luxury add-on. A stationary 11 kW wireless charging system typically incurs a hardware cost premium of 30–50% compared to a standard wired Level 2 wallbox. This is due to the additional cost of the ground pad (ferrites, litz wire), the vehicle assembly (compensation network), and the safety systems (FOD detection). For the average consumer, this represents a “Convenience Premium” rather than a financial investment.

- Commercial Fleets (The TCO Advantage): For transit buses and logistics trucks, WPT shifts from a luxury to a cost-saving mechanism. A comparative lifecycle analysis of airport shuttle fleets [106] demonstrated that while WPT infrastructure requires high initial investment, it enables battery downsizing. By utilizing high-power opportunity charging (50 kW+) at scheduled stops, buses can operate with smaller, lighter battery packs (reducing vehicle weight by up to 46%). Over a 12-year lifecycle, a wireless bus fleet was projected to cost $44.5 million, compared to $47.3 million for plug-in electric buses and $60.1 million for diesel. The savings are driven by reduced battery replacement costs and the elimination of manual labor for plugging/unplugging.

- Dynamic WPT (The Infrastructure Barrier): While technically feasible, Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) or “charging lanes” faces immense economic hurdles. Recent estimates place the electrification cost of highways between $1.7 million and $3.5 million per kilometer [107]. Consequently, DWPT is currently economically justifiable only for high-density freight corridors where the reduction in onboard battery weight for heavy-duty trucks offsets the massive infrastructure investment.

6.2. Industrial IoT: The “Truck Roll” Economics

- Maintenance vs. Hardware Cost: A battery-powered sensor node is cheap to manufacture ($10–$20) but expensive to maintain. In hazardous or inaccessible environments (e.g., bridge structural health monitoring or mining shafts), the labor cost to deploy a technician to replace a single battery can range from $300 to $600 per visit [108].

- The Payback Period: WPT (specifically RF harvesting or long-range microwave transfer) increases the initial hardware cost of the sensor node. However, by enabling “deploy-and-forget” operation, the technology achieves return on investment (ROI) immediately after avoiding the first required battery replacement cycle.

6.3. Grid Implications and the “Efficiency Tax”

- The Efficiency Gap: Modern resonant inductive systems achieve grid-to-battery efficiencies of 88–93%, roughly 5–7% lower than conductive AC charging.

- Consumer vs. Utility Impact: For an individual EV driver covering 20,000 km/year, this efficiency drop translates to approximately 200–300 kWh of wasted energy annually, costing roughly $40–$50. While negligible for the individual, at a grid scale comprising millions of vehicles, this represents gigawatt-hours of additional load. Policymakers must therefore balance the incentives for WPT (to encourage EV adoption via convenience) with strict minimum efficiency standards (such as those in SAE J2954) to prevent excessive grid strain.

7. Measurement Methods and Performance Evaluation

7.1. Efficiency and Electrical Characterization

- System-Level Efficiency (DC-DC): This encompasses losses in the inverter, resonator coils, and rectifier. Accurate measurement requires **High-Bandwidth Precision Power Analyzers**. These instruments must simultaneously sample voltage and current at high rates (typically >2 MS/s) to capture the harmonic content of the square-wave switching signal. A common error source is the “phase error” in current probes; at high frequencies, even a small phase delay in the probe can lead to massive errors in calculating active power () when the phase angle is near 90°.

- Resonator Efficiency (Coil-to-Coil): To isolate the physics of the magnetic link from the electronics, Vector Network Analyzers (VNAs) are the industry standard. VNAs measure Scattering parameters (S-parameters) [107]. The forward transmission coefficient () is used to derive the link efficiency. While highly precise for characterizing resonance frequency and bandwidth, VNAs typically operate at milliwatt power levels (“small signal”). This is a limitation because it fails to account for “large signal” non-linearities, such as ferrite core saturation or thermal drift that occurs during actual high-power operation [102].

7.2. Magnetic Coupling and Misalignment Tracking

- LCR Meters: For static characterization, LCR meters are used to measure self-inductance (L) and series resistance () at the specific operating frequency. Mutual inductance (M) is derived by measuring the series-aiding and series-opposing inductance of connected coils.

- Reflected Impedance Estimation (DMRI): In active control scenarios, the transmitter controller monitors its own input impedance (). As the receiver moves or misaligns, the reflected impedance changes. Advanced controllers use this data to estimate the coupling coefficient (k) and distance in real time without requiring external optical or mechanical sensors [103].

7.3. Safety (EMF) and Regulatory (EMC) Compliance

- Human Safety (SAR/ICNIRP): To ensure compliance with ICNIRP guidelines, Isotropic Field Probes are used to map the electric (E) and magnetic (H) field strength in the 3D space surrounding the charger. For specific absorption rate (SAR) assessment in biomedical implants, Phantom Models (robotically controlled probes inside a liquid-filled shell mimicking human tissue properties) are used to measure localized energy absorption.

- Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC): To ensure the WPT charger does not interfere with other electronics (like a car’s key fob or radio), radiated emissions are measured in an Anechoic Chamber using wideband antennas and Spectrum Analyzers, strictly following standards such as CISPR 11 [109] (Industrial, Scientific and Medical equipment).

8. Health Impact of WPT

8.1. Near-Field Exposure: Induction and Stimulation

- Magnetic Field Exposure: For Inductive Power Transfer (IPT), the high-current coils generate strong magnetic fields (H-field). Since magnetic fields permeate biological tissue with little attenuation, the primary safety metric is the internal electric field induced within the body, which must remain below thresholds that trigger involuntary nerve response. For high-power applications like EV charging (SAE J2954), shielding (aluminum and ferrite) is mandatory to keep the leakage flux density below the ICNIRP reference level (typically 27 μT for the general public at wireless charging frequencies).

- Active Implantable Medical Devices (AIMD): A critical subset of safety concerns involves interference with pacemakers and defibrillators. Even low-level fields acceptable for the general public can induce voltages in pacemaker leads, potentially disrupting cardiac monitoring. Consequently, WPT chargers often require “keep-out zones” for individuals with implants.

8.2. Far-Field Exposure: Thermal Effects

- Microwave Power Transfer (MPT): Exposure is governed by the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR), measured in Watts per kilogram (W/kg), which quantifies the rate of energy deposition in tissue. As frequency increases (e.g., 2.4 GHz to 28 GHz), the depth of penetration decreases, shifting the concern from deep-tissue heating to skin surface heating. MPT systems typically employ “exclusion zones” or beam-shutoff protocols if a human enters the transmission path to ensure power density remains below limits (e.g., 10 W/m2 for continuous public exposure).

- Laser Power Transfer (LPT): LPT systems operate in the optical or near-infrared spectrum. The human eye is the most vulnerable organ, as the cornea and lens focus the beam onto the retina, causing instantaneous thermal damage even at low power densities. LPT systems are classified under IEC 60825-1 standards and almost universally require Class 1 safety features, such as “virtual guard rings” or active detection systems that cut power within milliseconds if the line-of-sight is interrupted.

9. Conclusions

9.1. Technical Synthesis and Comparative Outcomes

- Near-Field Maturity vs. Constraints: Inductive Power Transfer (IPT) has established itself as the dominant standard for high-power applications (kW range), achieving DC-to-DC system efficiencies exceeding 90% in electric vehicle and consumer electronics sectors. However, its widespread integration is heavily constrained by the weight of ferrite cores and the safety risks associated with metal object heating (Eddy currents). In contrast, Capacitive Power Transfer (CPT) offers a lightweight, lower-cost alternative capable of penetrating metallic barriers, yet it remains limited by high voltage stress on components and lower overall power density (<10 kW typically).

- The Physics of Far-Field Limitations: While radiative technologies (Microwave and Laser) theoretically enable power transmission over kilometer-scale distances, they face a fundamental trade-off between beam safety and transfer efficiency. Current Microwave Power Transfer (MPT) systems struggle to exceed 40% end-to-end efficiency due to conversion losses (RF-to-DC) and diffraction limits. Laser Power Transfer (LPT) offers superior energy density for point-to-point applications but is severely compromised by atmospheric attenuation and strict ocular safety requirements, limiting its reliability in uncontrolled environments.

9.2. Future Research Directions

- Hybrid Compensation Topologies: Developing hybrid LCC-LCC or IPT-CPT coupler structures that combine the high-current capabilities of magnetic coupling with the electric-field advantages of capacitive coupling to improve misalignment tolerance.

- Wide Bandgap (WBG) Integration: The adoption of Gallium Nitride (GaN) and Silicon Carbide (SiC) devices in the inverter stage to push switching frequencies into the MHz range, thereby reducing the size of passive components and enabling higher efficiency in CPT systems.

- AI-Driven Dynamic Control: Moving beyond fixed-frequency tuning by integrating Machine Learning algorithms (such as Reinforcement Learning) to dynamically adjust impedance matching networks in real time. This is essential for maintaining efficiency in dynamic EV charging scenarios where coupling varies continuously.

- Standardization of Metrics: The academic community must adopt unified reporting standards that clearly distinguish between “Coil-to-Coil efficiency” and “System-level efficiency” to prevent misleading performance claims. Furthermore, standardized protocols for measuring biological safety (SAR) in high-power near-field systems are urgently needed to facilitate regulatory approval.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sagar, A.; Jain, N.; Jain, N.; Goyal, R.; Tomar, S.; Sharma, S.; Singh, A. A comprehensive review of the recent development of wireless power transfer technologies for electric vehicle charging systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83703–83751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Gupta, S. WPT techniques based power transmission: A state-of-art review. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kanpur, India, 3–5 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, S.H.; Husin, H.; Zaidin, N.; Razlan, S.S.; Bakar, A.A. Mathematical design of coil parameter for wireless power transfer using NI multisims software. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–23 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 250–254. [Google Scholar]

- Abou Houran, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, W. Design of a cylindrical winding structure for wireless power transfer used in rotatory applications. Electronics 2020, 9, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaisi, W.; El-Bayeh, C.Z. Adaptive control based on radial base function neural network approximation for quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2022 17th Annual System of Systems Engineering Conference (SOSE), Canton, MI, USA, 7–11 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, M.; Gupta, R.; Shrivastava, G. Challenges and Future Directions of Fuzzy System in Healthcare Systems: A Survey. In Soft Computing Techniques in Connected Healthcare Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Krithika, V.; Jeyanthi, R.S.S.; Saranya, K.A.; Saravanakumar, A.J. Wireless power transmission of mobile robot for target tracking. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. 2022, 13, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Hasan, M.A.; Mondal, M.M.; Al-Sharif, M. A comprehensive review of wireless power transfer methods, applications, and challenges. Eng. Rep. 2024, 6, e12951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, J. Safe and secure wireless power transfer networks: Challenges and opportunities in RF-based systems. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2016, 54, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoyeigbo, O.; Igwubor, V.U.; Onuoha, C.N. Wireless power transfer: A review. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 655, p. 012015. [Google Scholar]

- Valone, T. Geoengineering Tesla’s Wireless Power Transmission. Extra Ordinary Sci. Technol. 2017, 31–43. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320335847_Geoengineering_Tesla%27s_Wireless_Power_Transmission (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Schuder, J.C. Powering an artificial heart: Birth of the inductively coupled-radio frequency system in 1960. Artif. Organs 2002, 26, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.C. The history of wireless power transmission. Sol. Energy 1996, 56, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaro, F.; Summerer, L. Peter Glaser lecture: Space and a sustainable 21st century energy system. In Proceedings of the 57th International Astronautical Congress, Valencia, Spain, 2–6 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, B.; Shaker, S.A.; Hossain, M.A. Analysis and Modelling of Basic Wireless Power Transfer Compensation Topology: A Review. In Intelligent Data Analytics for Power and Energy Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 501–515. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Ma, D.; Tang, H. A review of recent trends in wireless power transfer technology and its applications in electric vehicle wireless charging. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurs, A.; Karalis, A.; Moffatt, R.; Cannon, J.D.; Dal Negro, S.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Soljačić, M. Wireless power transfer via strongly coupled magnetic resonances. Science 2007, 317, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Mi, C.C. Wireless power transfer for electric vehicle applications. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2014, 3, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Jin, N. Overview of wireless power transfer for electric vehicle charging. In Proceedings of the 2013 World Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exhibition (EVS27), Barcelona, Spain, 17–20 November 2013; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rim, C.T.; Mi, C. Wireless Power Transfer for Electric Vehicles and Mobile Devices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barbruni, G.L.; Aliberti, F.; De Luca, F.; Di Pascoli, S.; Carrara, F. Miniaturised wireless power transfer systems for neurostimulation: A review. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2020, 14, 1160–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca, E. Wireless Power Transfer: Fundamentals and Technologies; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-D.; Sun, C.; Suh, I.-S. A proposal on wireless power transfer for medical implantable applications based on reviews. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference, Goa, India, 18–21 May 2014; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Mazinani, A.; Noor, M.; Mazinani, O. A review on research challenges limitations and practical solutions for underwater wireless power transfer. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Ma, D.; Sun, L. Applications of wireless power transfer in medicine: State-of-the-art reviews. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, A.; Onar, O.C. A review of high-power wireless power transfer. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Chicago, IL, USA, 22–24 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kuka, S.; Ni, K.; Alkahtani, M. A review of methods and challenges for improvement in efficiency and distance for wireless power transfer applications. Power Electron. Drives 2020, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiku, M.; Eronu, E.; Ashigwuike, E. A review on wireless power transfer: Concepts, implementations, challenges, and mitigation scheme. Niger. J. Technol. 2020, 39, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mi, C.C.; Ma, D.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X. Wireless power transfer—An overview. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 66, 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Ziolkowski, R.W. Far field wireless power transfer for IoT applications enabled by an ultra-compact and highly-efficient Huygens rectenna. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference (WPTC), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 15–19 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 188–191. [Google Scholar]

- Popovic, Z. Near-and far-field wireless power transfer. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th International Conference on Advanced Technologies, Systems and Services in Telecommunications (TELSIKS), Niš, Serbia, 18–20 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhai, X.; Liu, Y. Near-field wireless power transfer for 6G internet of everything mobile networks: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, N. The wireless power transmission: Inductive coupling, radio wave, and resonance coupling. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2012, 1, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, A.A.; Sali, A.; Al-Mutaqqa, H.; Zaidin, N.; Hamsan, H.H.; Hidayat, Z.S. Wireless power transfer via inductive coupling. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. (JTEC) 2018, 10, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nikoletseas, S.; Yang, Y.; Georgiadis, A. Wireless Power Transfer Algorithms, Technologies and Applications in Ad Hoc Communication Networks; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Budhia, M.; Covic, G.A.; Boys, J.T. Design and optimization of circular magnetic structures for lumped inductive power transfer systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2011, 26, 3096–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Onar, O.C.; Chinthavali, M. Grid side regulation of wireless power charging of plug-in electric vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Raleigh, NC, USA, 15–20 September 2012; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 568–575. [Google Scholar]

- Manivannan, P. Qi open wireless charging standard: A wireless technology for the future. Int. J. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2013, 2, 573. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Shi, Y.; Hou, Y.T.; Lou, W. Wireless power transfer and applications to sensor networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2013, 20, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.K.; Masdar, M.N.; Rahim, S.; Ismail, Z.M. Analysis and Design Capacitive Power Transfer (CPT) System for Low Application Using Class-E LCCL Inverter by Investigate Distance between Plates Capacitive. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 1535, p. 012001. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, D.; Hong, S. Effect of coupling between multiple transmitters or multiple receivers on wireless power transfer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 60, 2602–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, S.; Park, J. Impedance matching considering cross coupling for wireless power transfer to multiple receivers. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Wireless Power Transfer (WPT), Denver, CO, USA, 15–16 May 2013; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, Y.; Song, K.; Li, Y. Compensation of cross coupling in multiple-receiver wireless power transfer systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2016, 12, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, F.; Wu, W.; Lin, H.; Mi, C.C. A loosely coupled capacitive power transfer system with LC compensation circuit topology. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 18–22 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Atiyah, N.Q.; Abdullah, A.A.; Hamsan, H.H. The analysis of variation in plate geometry for capacitive power transfer pads utilized in electric vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2018 18th Mediterranean Microwave Symposium (MMS), Istanbul, Turkey, 31 October–2 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lu, F. Review, analysis, and design of four basic CPT topologies and the application of high-order compensation networks. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 6181–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozario, D.; Azeez, N.A.; Williamson, S.S. A modified resonant converter for wireless capacitive power transfer systems used in battery charging applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Dearborn, MI, USA, 27–29 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; Zhang, H.; Mi, C.C. A two-plate capacitive wireless power transfer system for electric vehicle charging applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Agarwal, N.; Behera, B. Power transfer using portable surfaces in capacitively coupled power transfer technology. IET Power Electron. 2016, 9, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, J. Design of robust capacitive power transfer systems using high-frequency resonant inverters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2021, 3, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, F.; Mi, C.C. Research and application of capacitive power transfer system: A review. Electronics 2022, 11, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE J2954; SAE International Approves TIR J2954 for PH/EV Wireless Charging. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2016.

- Deng, J.; Li, S.; Nguyen, T.; Pantic, Z.; Mi, C.C. Development of a high efficiency primary side controlled 7kW wireless power charger. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference (IEVC), Florence, Italy, 17–19 December 2014; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; Zhang, H.; Mi, C.C.; Wang, H.; Cao, M.; Zhang, X. A double-sided LC-compensation circuit for loosely coupled capacitive power transfer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.-G.; Huang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. Capacitive power transfer system with a mixed-resonant topology for constant-current multiple-pickup applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 32, 8778–8786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Song, K.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Z. Analysis and design of hybrid inductive and capacitive wireless power transfer for high-power applications. IET Power Electron. 2018, 11, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Zhou, W. Wireless laser power transmission: A review of recent progress. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 34, 3842–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Y. Distributed laser charging: A wireless power transfer approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 3853–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mulders, J.; Van den Bossche, A.; Rombouts, P. Wireless power transfer: Systems, circuits, standards, and use cases. Sensors 2022, 22, 5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raavi, S.K.; Kuntala, S.S.; Gunturu, V.C.B. An optical wireless power transfer system for rapid charging. In Proceedings of the 2013 Texas Symposium on Wireless and Microwave Circuits and Systems (WMCS), Waco, TX, USA, 4–5 April 2013; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 60825-1:2014; Safety of Laser Products—Part 1: Equipment Classification and Requirements. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Summerer, L.; Purcell, O. Concepts for Wireless Energy Transmission via Laser; Europeans Space Agency (ESA)-Advanced Concepts Team: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2009.

- Blackwell, T.D. Recent demonstrations of laser power beaming at DFRC and MSFC. In AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics: Melville, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 746, pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.; Zuo, W.; Feng, G.; Li, D. Analysis and experiment of the laser wireless energy transmission efficiency based on the receiver of powersphere. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 55340–55351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N.; Takeda, K. Laser energy transmission for a wireless energy supply to robots. Robot. Autom. Constr. 2008, 10, 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Ortabasi, U.; Friedman, H. Powersphere: A photovoltaic cavity converter for wireless power transmission using high power lasers. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE 4th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conference, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 7–12 May 2006; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 1332–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-M.; Choi, J.-S.; Jung, H. Experimental demonstration of underwater optical wireless power transfer using a laser diode. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2018, 16, 080101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wei, X.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Lu, G. Microwave wireless power transmission technology index system and test evaluation methods. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2022, 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Lin, S.; Gao, H.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y. Design of high-efficiency microwave wireless power transmission system. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2016, 58, 1704–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanto, M.S.I.; Ahamed, M.K.; Rabbani, M.G.; Hossain, M.S.; Mizan, M.S.A. Design of rectennas at 7.30 GHz for RF power harvesting. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Telecommunications and Photonics (ICTP), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 21–23 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tissier, J.; Koohestani, M.; Latrach, M. A comparative study of conventional rectifier topologies for Low Power RF Energy Harvesting. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference (WPTC), London, UK, 18–21 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Erman, F.; Koziel, S.; Zyoud, A.; Leifsson, L.; Ullah, U.; Alkaraki, S. Power Transmission for Millimeter-Wave Indoor/Outdoor Wearable IoT Devices Using Grounded Coplanar Waveguide-Fed On-Body Antenna. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 14063–14072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubau, G.; Schwering, F. On the guided propagation of electromagnetic wave beams. IRE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2003, 9, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.D.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, G.H. Preliminary operational aspects of microwave-powered airship drone. Int. J. Micro Air Veh. 2019, 11, 1756829319861368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Q.; Jin, K.; Zhu, X. Directional radiation technique for maximum receiving power in microwave power transmission system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 6376–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Duan, X. Investigation on beam collection efficiency in microwave wireless power transmission. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 2018, 32, 1136–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Jin, K.; Yang, G.; Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z. A 5.8-GHz high-power and high-efficiency rectifier circuit with lateral GaN Schottky diode for wireless power transfer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 35, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.C. The microwave powered helicopter. J. Microw. Power 1966, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.U.; Shanto, M.S.I.; Sharaf, M.F.; Hossain, M.S. Design and analysis of a 35 GHz rectenna system for wireless power transfer to an unmanned air vehicle. Energies 2022, 15, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Wu, F.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Huang, W.; Ma, J. A microwave power transmission experiment based on the near-field focused transmitter. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2019, 18, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criswell, D.R.; Waldron, R.D. Lunar system to supply solar electric power to Earth. In Proceedings of the 25th Intersociety Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, Reno, NV, USA, 12–17 August 1990; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 619–623. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, S.H.; Sali, A.; Abdullah, A.A.; Hamsan, H.H.; Zaidin, N. Performance analysis on dynamic wireless charging for electric vehicle using ferrite core. IIUM Eng. J. 2022, 23, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.A.; Hamsan, H.H.; Yusoff, S.H.; Sali, A. Design of U and I Ferrite Core On Dynamic Wireless Charging for Electric Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–23 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Zaini, S.A.; Hamsan, H.H.; Sali, A.; Abdullah, A.A.; Yusoff, S.H. Design of circular inductive pad couple with magnetic flux density analysis for wireless power transfer in EV. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2021, 23, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liao, M.; He, L.; Lee, C.-K. Parameter Optimization of Wireless Power Transfer Based on Machine Learning. Electronics 2024, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assawaworrarit, S.; Yu, X.; Fan, S. Robust wireless power transfer using a nonlinear parity–time-symmetric circuit. Nature 2017, 546, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishk, A.; Yeap, K.H. Recent Microwave Technologies; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, C.; Erdemir, D.; Arslan, A.; Ceylan, H. Modeling of WPT system for small home appliances. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ICEEE), Adana, Turkey, 9–11 April 2021; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE C95.1; IEEE Standard for Safety Levels With Respect to Human Exposure to Electric, Magnetic, and Electromagnetic Fields, 0 Hz to 300 GHz. Standard IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2019.

- Lunardon, A.; Vladimirova, D.; Boucsein, B. How railway stations can transform urban mobility and the public realm: The stakeholders’ perspective. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Williams, K.; El Khouly, E.; Lu, F.; Mi, C.C. A review of power transfer systems for light rail vehicles: The case for capacitive wireless power transfer. Energies 2023, 16, 5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.I.; Aliberti, F.; De Luca, F.; Di Pascoli, S.; Carrara, F. Near-field wireless power transfer used in biomedical implants: A comprehensive review. IET Power Electron. 2022, 15, 1936–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, F.H. Future with wireless power transfer technology. J. Electr. Electron. Syst. 2018, 7, 1000279. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Lu, D.; Zhang, J. Standardization efforts: The relationship between knowledge dimensions, search processes and innovation outcomes. Technovation 2016, 48, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Javed, N.; Khalid, M. A state of the Art review on Wireless Power Transfer a step towards sustainable mobility. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th IEEE India Council International Conference (INDICON), Roorkee, India, 15–17 December 2017; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, B.; Kwak, J.; Hwang, S.; Lee, D.; Lee, W.; Kim, B. A 15-W triple-mode wireless power transmitting unit with high system efficiency using integrated power amplifier and DC–DC converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 9574–9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabsi, A.; Alshami, H.A.; Alhazmi, O.A.; Eissa, M.E.; Alqahtani, T.A. Wireless power transfer technologies, applications, and future trends: A review. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2024, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Mi, C.C.; Ma, D. A review of wireless power transfer for electric vehicles: Prospects to enhance sustainable mobility. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, A.; Mori, A.; Inamori, M. Analyzation of antenna measurement method for wireless power transmission. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2017–2017 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Penang, Malaysia, 5–8 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 2538–2543. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, P.K.; Nair, S.C.S.; Jose, J.; G., V.; Sreejith, S. Overview of different WPT standards and a simple method to measure EM radiation of an electric vehicle wireless charger. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave and RF Conference (IMARC), Mumbai, India, 13–15 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zucca, M.; Zucca, M.; Delpero, L.; Dondo, G. Assessment of the overall efficiency in WPT stations for electric vehicles. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.; Sharma, A.; Reddy, C.C. An unconventional measurement technique to estimate power transfer efficiency in series–series resonant WPT system using S-parameters. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 8004009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, J.; Longzhao, T.; Zihao, Y.; Lieyue, W.; Guorong, L. A novel distance measurement method based on reflected impedance for resonant wireless power transmission system. In Proceedings of the 2020 Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 29–31 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 61980; Electric Vehicle Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) Systems—Part 1: General Requirements. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 19363; Electrically Propelled Road Vehicles—Magnetic Field Wireless Power Transfer—Safety and Interoperability Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Guo, Z.; Lai, C.S.; Luk, P.; Zhang, X. Techno-economic assessment of wireless charging systems for airport electric shuttle buses. J. Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, D.Z.W.; Tian, Q.; Lin, Y.H. Optimal configuration of dynamic wireless charging facilities considering electric vehicle battery capacity. Transp. Res. Part Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 181, 103376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datalogic. Wireless Charging Reduces Total Cost of Ownership in Industrial Handhelds. In White Paper; Datalogic S.p.A.: Bologna, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CISPR 11:2024; Industrial, Scientific and Medical Equipment—Radio-Frequency Disturbance Characteristics—Limits and Methods of Measurement. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

| Transmitted Power (W) | Efficiency () % | Distance (m) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 40 | 2.00 | [17] |

| 60 | 75 | 0.90 | [35] |

| 3300 | 90 | 0.18 | [19] |

| 5000 | 90 | 0.15 | [36] |

| 2000 | 91 | 0.075 | [37] |

| 6600 | 86 | - | [38] |

| Feature | Inductive Coupling (IPT) | Capacitive Coupling (CPT) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Field | Magnetic Field (H) | Electric Field (E) |

| Transfer Driver | High Current (I) | High Voltage (V) |

| Frequency | Low/Medium (10–200 kHz) | High/Very High (MHz range) |

| Coupler Materials | Litz Wire + Ferrite Cores | Copper/Aluminum Plates |

| Weight & Cost | Heavy/High | Light/Low |

| Foreign Objects | Heats up metal (Eddy Currents) | Sensitive to dielectric changes |

| Safety Concern | Heating of foreign metals | High Voltage Arcing |

| Main Application | EV Charging, Mobile Phones (Qi) | Drones, Low-power IoT |

| Efficiency (%) | Rx Power (W) | Distance (m) | (nm) | Laser Type | PV Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.5 | 7.0 | 15 | 90 | Diode | Si [63] |

| 15.5 | 5.0 | - | 532 | DPSS | Single Crystal Si [64] |

| 17.0 | - | 100 km | 1060 | Fiber | CIS [57] |

| 14.0 | 40.0 | 50 | 808 | Diode | GaAs [65] |

| 14.0 | 19.0 | 3 | 1064 | Nd:YAG | Si [66] |

| 4.0 | 0.008 | 4 | 661 | Diode | Si [67] |

| Transmitted P (W) | Received P (W) | (%) | Freq. (GHz) | Dist. (m) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 10.0 | <10 | 0.915 | 15 | [75] |

| - | 3.44 | 55.0 | 10.0 | 4 | [76] |

| - | 6.40 | 1.3 | 5.8 | 2 | [77] |

| 3000–5000 | 280.0 | <10 | 2.45 | - | [78] |

| 32,000 | 27,000 | 84.0 * | 35.0 | 1500 | [79] |

| 500 | 41.0 | <10 | 5.8 | 10 | [80] |

| Category | Far-Field (Radiative) | Near-Field (Non-Radiative) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | LPT (Laser) | MPT (Microwave) | IPT (Inductive) | CPT (Capacitive) |

| Physics | Photonic Beam | Propagating EM Wave | Magnetic Flux (H) | Electric Field (E) |

| Distance | km range (Line of Sight) | m to km range | Short (mm to cm) | Short (mm to cm) |

| Frequency | Optical (THz) | 2.45 GHz–5.8 GHz | 85 kHz–200 kHz | 1 MHz–13.56 MHz |

| Efficiency | Low (<30%) due to E-O-E conversion | Moderate (<50%) due to path loss | High (>90%) at close range | Moderate (>80%) |

| Alignment | Strict Line-of-Sight required | Beam steering allows flexibility | Sensitive to lateral misalignment | Sensitive; requires plate overlap |

| Safety | High Risk (Eye/Skin damage) | Moderate Risk (RF Heating/SAR) | Low Risk (Localized fields) | Low Risk (Localized fields) |

| Env. Impact | Blocked by fog/rain | Penetrates clouds (Rain fade possible) | Unaffected by non-metals | Sensitive to humidity/water |

| Key App. | Space-to-Earth, Drones | Satellites, IoT Sensors | EV Charging, Mobile | Through-bumper EV, Ind. Automation |

| Standard | Organization | Frequency | Power Level | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qi | WPC | 87–205 kHz | 5 W–15 W | Tightly coupled inductive; dominant mobile standard. |

| AirFuel Resonant | AirFuel Alliance | 6.78 MHz | Up to 50 W | Loose coupling; allows “spatial freedom” and multiple devices. |

| Ki | WPC | ∼20–100 kHz | Up to 2.2 kW | Cordless kitchen appliances; NFC communication. |

| SAE J2954 | SAE International | 85 kHz (Band) | 3.7–11 kW | Stationary EV charging; defines WPT1-3 power classes. |

| IEC 61980 [104] | IEC | 79–90 kHz | Up to 22 kW | General safety/interoperability requirements for EV supply equip. |

| ISO 19363 [105] | ISO | 85 kHz | 3.7–11 kW | Focuses specifically on the Vehicle Assembly (VA) safety/interop. |

| Metric | Instrument/Method | Key Advantage | Key Limitation/Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Efficiency () | Precision Power Analyzer (e.g., Yokogawa) | Captures all losses (switching, core, copper) in real time. | Susceptible to phase-angle errors at low power factors; high cost. |

| Resonator Link () | Vector Network Analyzer (VNA) | Extremely precise frequency sweep and Q-factor analysis. | “Small-signal” measurement ignores ferrite saturation and thermal effects. |

| Mutual Inductance (M) | LCR Meter (Series-aiding method) | Simple, standard verification for coil manufacturing. | Static measurement only; cannot track dynamic movement. |

| Misalignment | Reflected Impedance Estimation (Software) | No external sensors required; enables sensorless control. | Requires complex calibration algorithms; sensitive to metal debris. |

| Radiated Emissions | Spectrum Analyzer + Antenna (in Chamber) | Required for legal certification (FCC/CE compliance). | Expensive infrastructure (Anechoic Chamber) required. |

| Biological Safety | Dosimetric Phantom + E-field Probe | Only method to accurately measure SAR in tissue. | Invasive, slow process; often approximated by simulation (FDTD). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Badawi, A.; Elzein, I.M.; El-bayeh, C.Z.; Alqaisi, W.; Zyoud, A.M.; Ghanem, W. A Review on Near-Field and Far-Field Wireless Power Transfer Technologies. Energies 2026, 19, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010157

Badawi A, Elzein IM, El-bayeh CZ, Alqaisi W, Zyoud AM, Ghanem W. A Review on Near-Field and Far-Field Wireless Power Transfer Technologies. Energies. 2026; 19(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadawi, Ahmed, I. M. Elzein, Claude Ziad El-bayeh, Walid Alqaisi, Alhareth M. Zyoud, and Wasel Ghanem. 2026. "A Review on Near-Field and Far-Field Wireless Power Transfer Technologies" Energies 19, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010157

APA StyleBadawi, A., Elzein, I. M., El-bayeh, C. Z., Alqaisi, W., Zyoud, A. M., & Ghanem, W. (2026). A Review on Near-Field and Far-Field Wireless Power Transfer Technologies. Energies, 19(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010157