Biomethane Yield Modeling Based on Neural Network Approximation: RBF Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Biogas Production and Its Role in Renewable Energy

1.2. Feedstock Types and Challenges of Anaerobic Digestion

1.3. Modeling Needs in Anaerobic Digestion

1.4. Artificial Neural Networks in Biogas Research

1.5. Objective of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

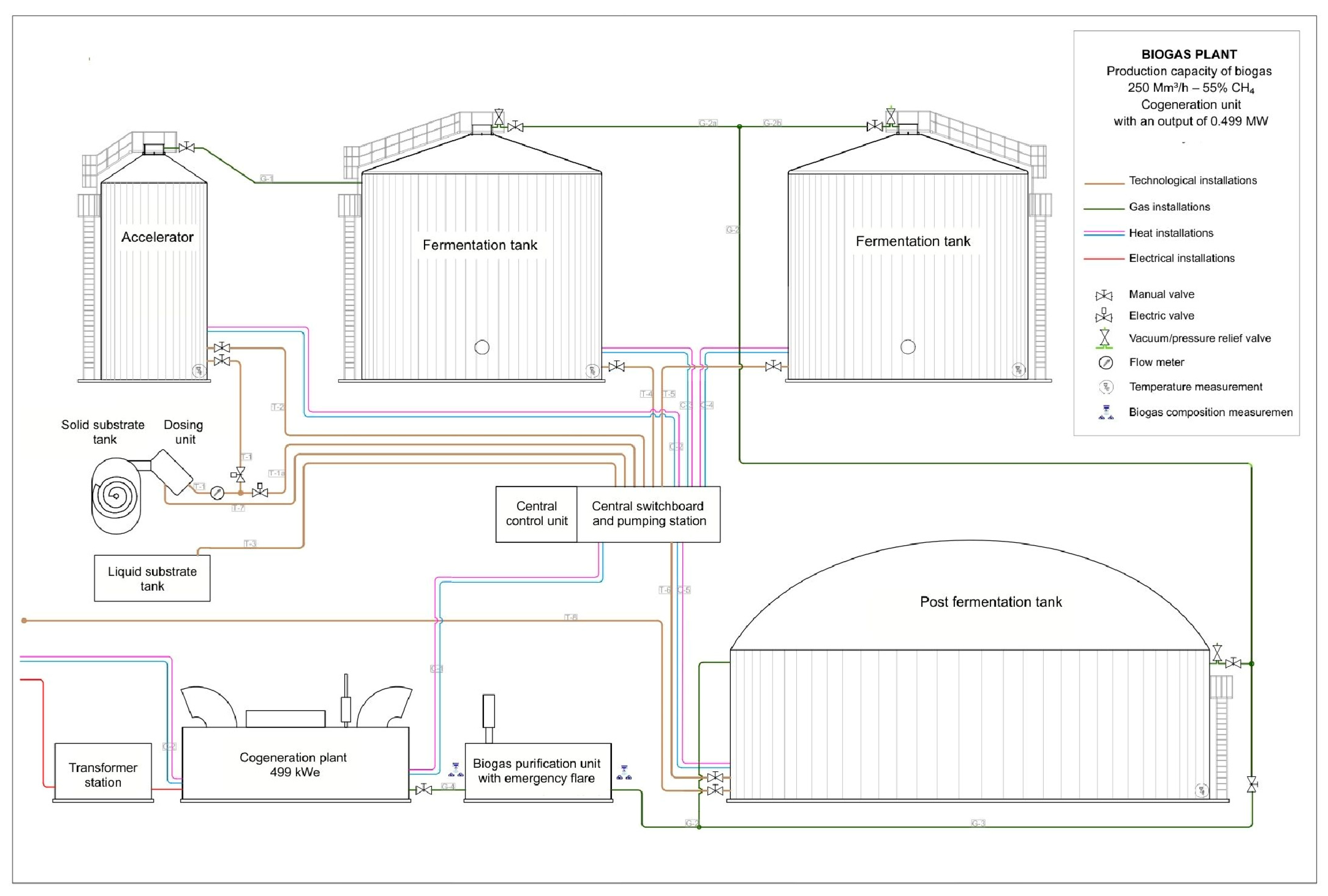

2.1. Description of the Przybroda Biogas Plant

2.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

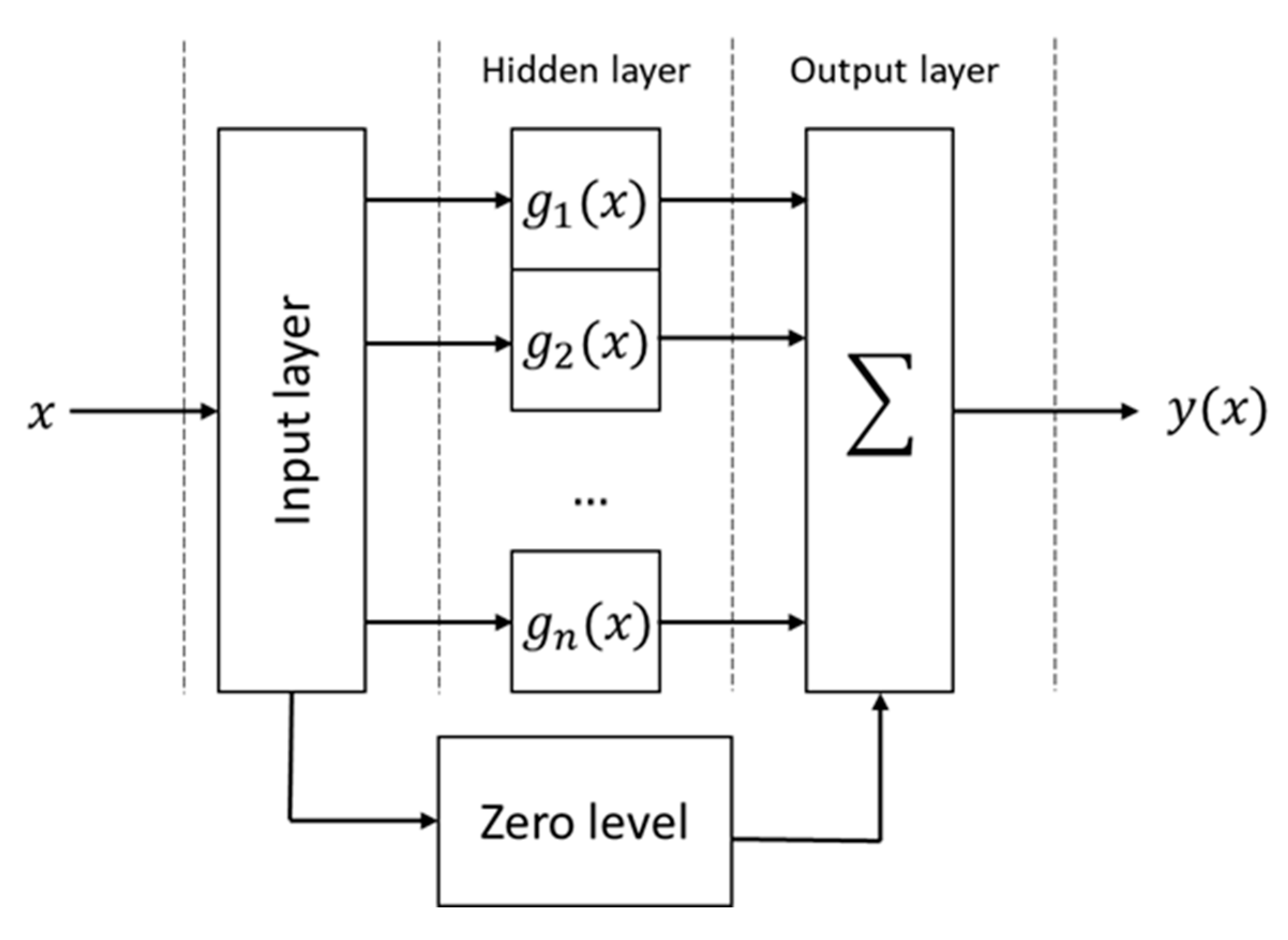

2.3. RBF-NN Model Architecture

2.4. Training Procedure and Model Calibration

2.5. Performance Evaluation (RMSE, R2)

- (1)

- the model based on the temperature, and

- (2)

- the model based on methane fraction.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Data Characteristics and Preprocessing Results

- Temperature dataset (10 points): daily mean digester temperature paired with corresponding methane production.

- Methane-fraction dataset (10 points): measured methane percentage in biogas paired with total biogas flow.

3.2. Model Architecture: Practical Implications

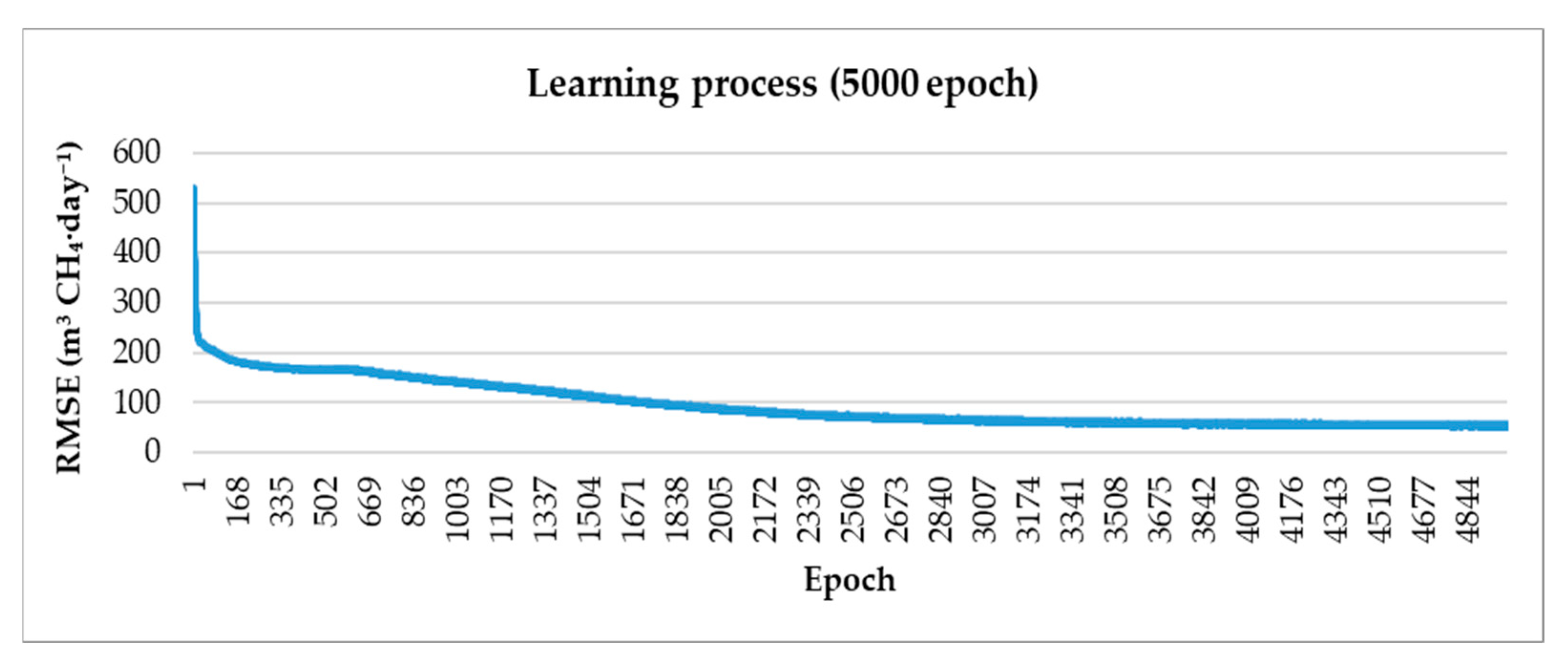

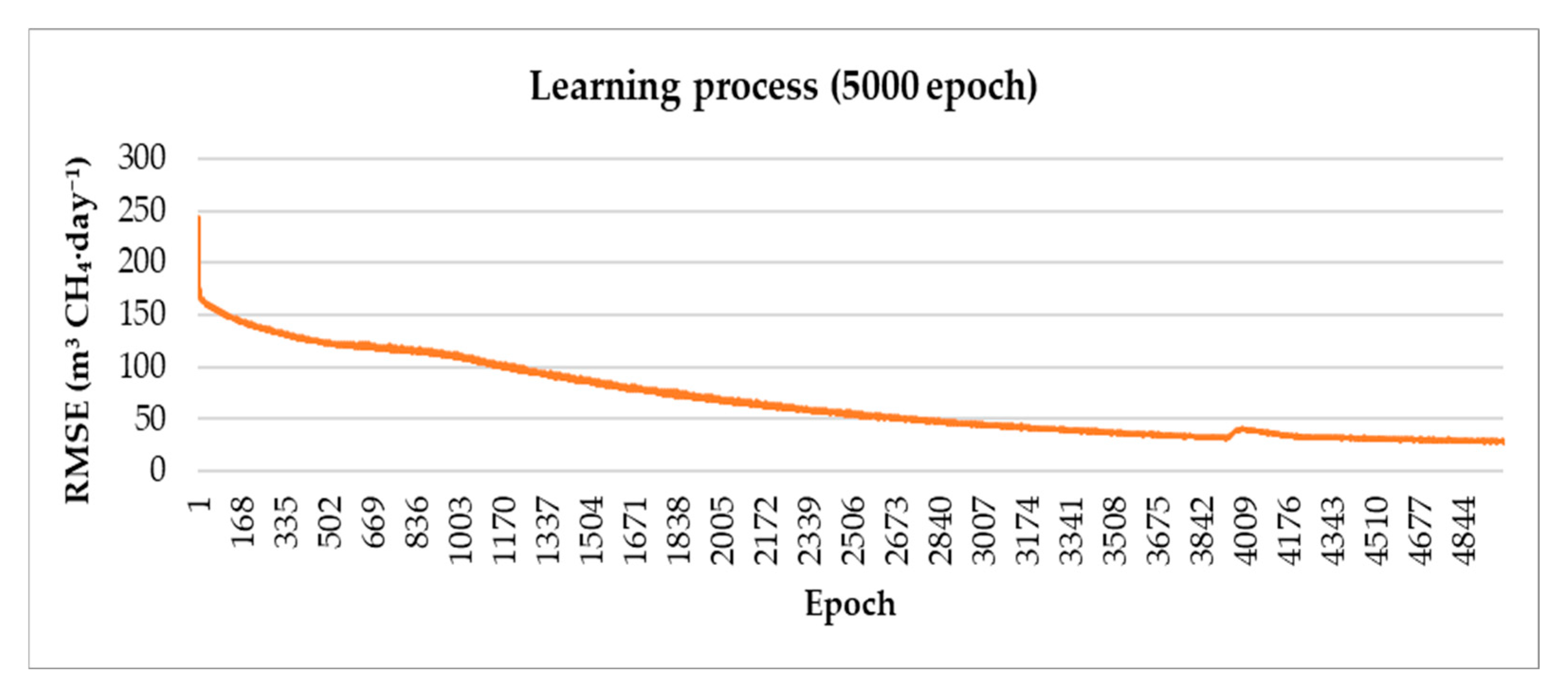

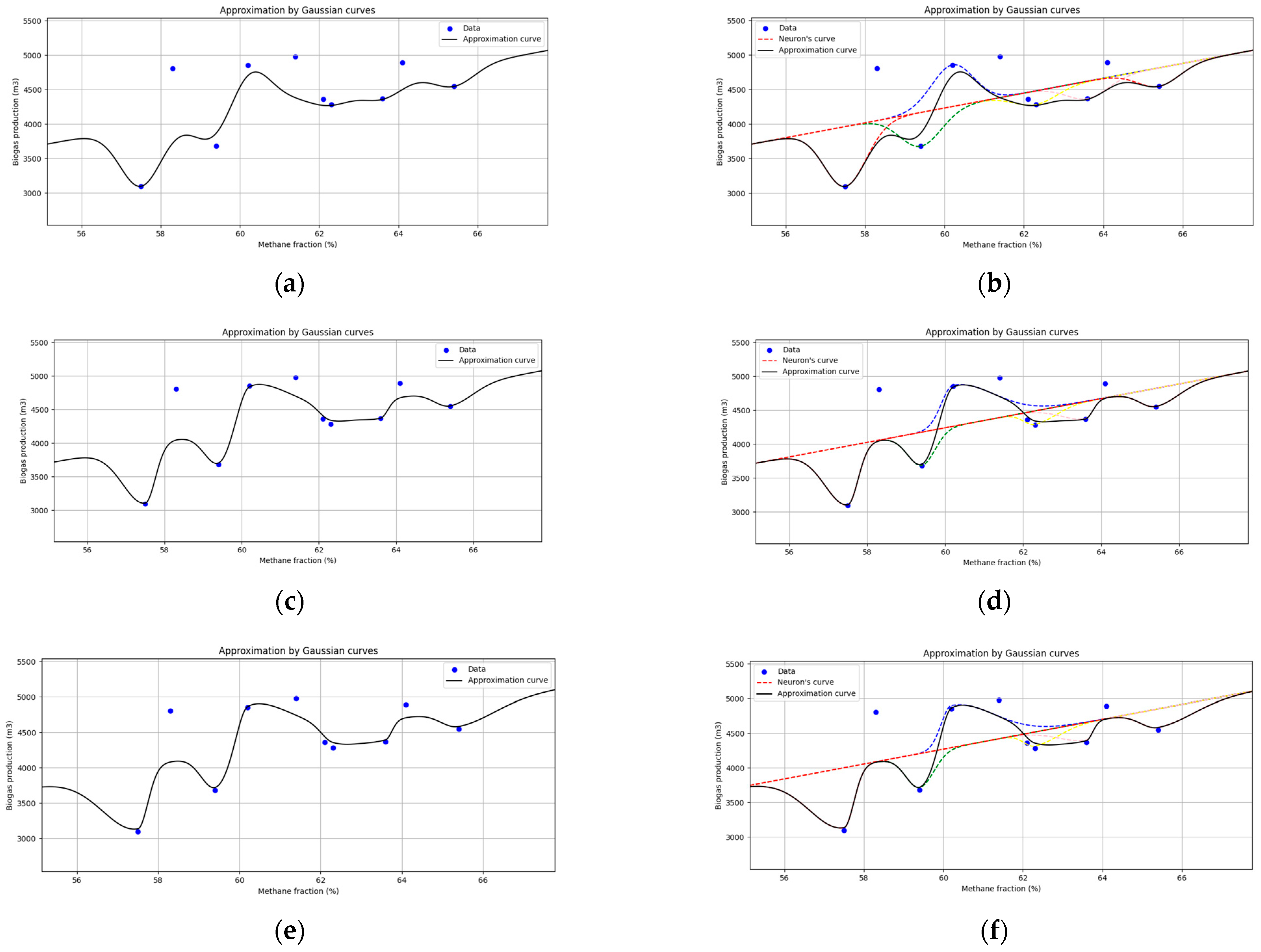

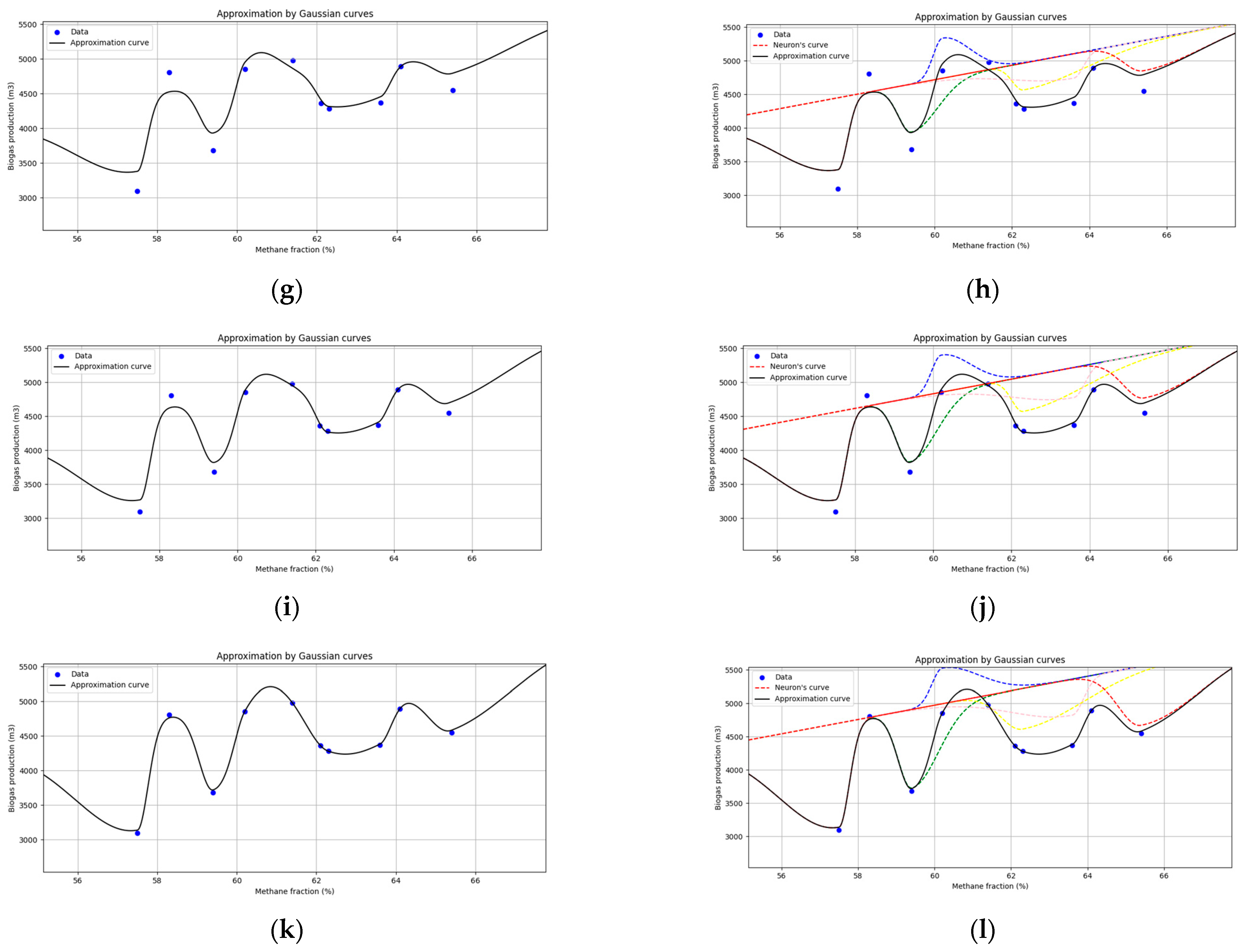

3.3. Training Dynamics and Convergence Behavior

3.4. Model Performance and Comparative Evaluation

3.5. Broader Implications and Applications

- Optimization of the learning process. Depending on the input and output data dimensions, some controlled parameters learn more slowly than others, which can lead to slower learning due to uneven parameter changes or even overlearning. It is necessary to develop an algorithm that would allow fitting the parameters evenly to stabilize learning.

- Optimizing the number of neurons. A large number of neurons leads to an increase in computation without obtaining equivalent utility, while a lack of neurons worsens the accuracy or makes the approximation impossible, so it is necessary to develop a methodology for optimal neuron choice to strike a balance between accuracy and computation. In this case, algorithms that modify the number of neurons directly during the training process are quite popular: adding neurons to a place with a consistently high error and/or removing a ‘dead’ neuron.

- Expanding the number of dimensions. This program is designed for approximation in the 2D space. Accordingly, the code itself needs to be improved for an arbitrary number of input and output parameters for multi-criteria approximation.

3.6. Comparison with Recent Modeling Approaches in the Literature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonathan, A.E.; Agbajor, G.K.; David, O.O.; Egbele, R.; Elemike, E.E.; Hossain, I. Determination and Prediction of Biogas Production Potential from Selected Biomasses as Alternative Renewable Energy Source in Sapele, Nigeria. Renew. Energy 2025, 255, 123802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozakis, S.; Bartoli, A.; Dach, J.; Jędrejek, A.; Kowalczyk-Juśko, A.; Mamica, Ł.; Pochwatka, P.; Pudelko, R.; Shu, K. Policy Impact on Regional Biogas Using a Modular Modeling Tool. Energies 2021, 14, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostetskyi, B.I. Current Trends and Development Prospects in Ukraine. Visnyk Agrar. Sci. 2020, 98, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Scarlat, N.; Dallemand, J.-F.; Fahl, F. Biogas: Developments and Perspectives in Europe. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamarchuk, V.I. Assessment of Biogas Production Potential in the Agricultural Sector of Ukraine. Energetyka Ta Elektr. 2022, 2, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- European Biogas Association (EBA). EBA Statistical Report 2023: Tracking Biogas and Biomethane Deployment Across Europe; European Biogas Association (EBA): Etterbeek, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Appels, L.; Baeyens, J.; Degrève, J.; Dewil, R. Principles and Potential of the Anaerobic Digestion of Waste-Activated Sludge. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm-Nielsen, J.B.; Al Seadi, T.; Oleskowicz-Popiel, P. The Future of Anaerobic Digestion and Biogas Utilization. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5478–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetsenko, I.S.; Yu, H.M. Biogas as an Energy Resource: Problems and Prospects. Sci. News NTUU KPI 2021, 5, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York City, NY, USA, 2015.

- Opryshko, O.; Pasichnyk, N.; Kiktev, N.; Dudnyk, A.; Hutsol, T.; Mudryk, K.; Herbut, P.; Łyszczarz, P.; Kukharets, V. European Green Deal: Satellite Monitoring in the Implementation of the Concept of Agricultural Development in an Urbanized Environment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beila, I.; Hoffstede, U.; Kasten, J.; Beil, M.; Wachendorf, M.; Wijesingha, J. Remote Sensing-Based Long-Term Assessment of Bioenergy Policy Impact on Agricultural Land Cover Change: A Case Study of Biogas in the Weser-Ems Region in Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1003, 180667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witaszek, K.; Herkowiak, M.; Pilarska, A.A.; Czekała, W. Methods of Handling the Cup Plant (Silphium perfoliatum L.) for Energy Production. Energies 2022, 15, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Tan, L.; Kida, K.; Morimura, S.; Sun, Z.-Y.; Tang, Y.-Q. Potential for Reduced Water Consumption in Biorefining of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Bioethanol and Biogas. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2021, 131, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Bai, X.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, S.; Gao, R.; Sun, J. Study on Improving Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Cow Manure and Corn Straw by Fruit and Vegetable Waste: Methane Production and Microbial Community in CSTR Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polishchuk, V.; Shvorov, S.; Voitiuk, V.; Khmelovskyi, V.; Titova, L.; Yeremenko, A.; Zubok, T.; Valiev, T. The Use of Straw Pellets with the Addition of Crude Glycerin for the Intensification of Biogas Production during the Anaerobic Fermentation of Cow Manure. Probl. Reg. Energetics 2025, 2, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablodsky, M.; Shvorov, S.; Polishchuk, V.; Trokhaniak, V.; Valiev, T. Mathematical and Simulation Model for Determining the Technical and Economic Efficiency of the Implementation and Use of Agricultural Waste Conversion Technology into Biogas According to the Seasons of the Year. Energy Autom. 2024, 73, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.A.; Zeshan; Hassan, M. Enhancing Biogas Production through Co-Digestion and Thermal Pretreatment of Wheat Straw and Sunflower Meal. Renew. Energy 2021, 168, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolessa, A.; Goosen, N.J.; Louw, T.M. Probabilistic Simulation of Biogas Production from Anaerobic Co-Digestion Using Anaerobic Digestion Model No. 1: A Case Study on Agricultural Residue. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 192, 108810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablodskiy, M.; Pliuhin, V.; Kucheruk, P. Biomethanogenesis Processes of Bird Droppings Mixtures with Substances Containing Lignin Under the Influence of Physical Fields. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 41st International Conference on Electronics and Nanotechnology (ELNANO), Kyiv, Ukraine, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Romaniuk, W.; Rogovskii, I.; Polishchuk, V.; Titova, L.; Borek, K.; Wardal, W.J.; Shvorov, S.; Dvornyk, Y.; Sivak, I.; Drahniev, S.; et al. Study of Methane Fermentation of Cattle Manure in the Mesophilic Regime with the Addition of Crude Glycerine. Energies 2022, 15, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazizade-Fard, M.; Koupaie, E.H. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Wastewater Sludge and Food Waste: A Machine Learning Approach to Process Modeling and Optimization. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniswamy, D.; Ramesh, G.; Sivasankaran, S.; Kathiravan, N. Optimising Biogas from Food Waste Using a Neural Network Model. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2017, 170, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.M.; Blanco, E.; Borrion, A. Predicting Total Biogas Potential of Food Waste Using the Initial Output of Biogas Potential Tests as Input Data to Train an Artificial Neural Network. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 26, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zoubi, A.I.; Alkhamis, T.M.; Alzoubi, H.A. Optimized Biogas Production from Poultry Manure with Respect to PH, C/N, and Temperature. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcin, M.; Yilmaz, C.; Koyuncu, I.; Tuna, M. Optimization of Solar and Geothermal Energy Assisted Power, Heating and Hydrogen Production Using Field Programmable Gate Arrays and Artificial Neural Networks. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 66, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Li, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yan, B.; Tao, J.; Zhou, S.; Chen, G. The Prediction and Optimization of Biomass Compatibility Ratios by Machine Learning for Enhancing Methane Production in Anaerobic Co-Digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 437, 133071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamichailidou, D.; Alexandridis, A.; Anagnostopoulos, G.; Syriopoulos, G.; Sekkas, O. Modeling Biogas Production from Anaerobic Wastewater Treatment Plants Using Radial Basis Function Networks and Differential Evolution. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 157, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Murray, C.; Sloan, W.T.; You, S. Predicting the Methane Production of Microwave-Pretreated Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste: A Machine Learning Approach. Energy 2025, 328, 136613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Juśko, A.; Pochwatka, P.; Zaborowicz, M.; Czekała, W.; Mazurkiewicz, J.; Mazur, A.; Janczak, D.; Marczuk, A.; Dach, J. Energy Value Estimation of Silages for Substrate in Biogas Plants Using an Artificial Neural Network. Energy 2020, 202, 117729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiewicz, P.; Piotrowski, K.; Ober, J.; Karwot, J. Innovative Artificial Neural Network Approach for Integrated Biogas—Wastewater Treatment System Modelling: Effect of Plant Operating Parameters on Process Intensification. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 124, 109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueguim Kana, E.B.; Oloke, J.K.; Lateef, A.; Adesiyan, M.O. Modeling and Optimization of Biogas Production on Saw Dust and Other Co-Substrates Using Artificial Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm. Renew. Energy 2012, 46, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, H.; Çolak, E.; Başer, V. Forecasting Biogas Potential in Türkiye’s Central Anatolia Region with Artificial Neural Networks and Geographical Information System-Based Analysis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, M.; Mahmoudimehr, J. A Correlation for Optimal Steam-to-Fuel Ratio in a Biogas-Fueled Solid Oxide Fuel Cell with Internal Steam Reforming by Using Artificial Neural Networks. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.V.; Dhar, H.; Kumar, S.; Thalla, A.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Wong, J.W.C. Artificial Neural Network Based Modeling to Evaluate Methane Yield from Biogas in a Laboratory-Scale Anaerobic Bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 217, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.W.; Seo, J.; Kim, K.; Lim, S.J.; Chung, J. Prediction of Biogas Production Rate from Dry Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste: Process-Based Approach vs. Recurrent Neural Network Black-Box Model. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweke, C.N.; Onu, C.E.; Nwabanne, J.T.; Ohale, P.E.; Madiebo, E.M.; Chukwu, M.M. Optimal Pretreatment of Plantain Peel Waste Valorization for Biogas Production: Insights into Neural Network Modeling and Kinetic Analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girmay, H.; Yeneneh, K.; Gopal, R. Comprehensive Analysis and Prediction of Biogas-Diesel Dual-Fuel Combustion in Direct Injection Diesel Engines: Experimental and Artificial Neural Network Approach. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade Cruz, I.; Chuenchart, W.; Long, F.; Surendra, K.C.; Renata Santos Andrade, L.; Bilal, M.; Liu, H.; Tavares Figueiredo, R.; Khanal, S.K.; Fernando Romanholo Ferreira, L. Application of Machine Learning in Anaerobic Digestion: Perspectives and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 345, 126433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallicheruvu, N.K.; Gnanasekaran, S. ANN-Driven Prediction of Optimal Machine Learning Models for Engine Performance in a Dual-Fuel Mode Powered by Biogas and Fish Oil Biodiesel. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 25, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substrate | 2022 [mg] | 2023 [mg] |

|---|---|---|

| Corn silage | 6397.0 | 3842.0 |

| Distillers’ stillage | 4362.0 | 2692.9 |

| Ground corn | 181.0 | – |

| Onion husks | 215.6 | – |

| Cattle manure | 13.5 | – |

| Animal feed unfit for consumption | 15.8 | – |

| Distillery syrup | 194.5 | 1096.0 |

| Cattle slurry | – | 133.3 |

| Total | 11,379.4 | 7764.2 |

| Epoch | 0 | 10 | 50 | 1000 | 2000 | 5000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE temperature approximation | 531 | 291 | 212 | 138 | 87 | 52 |

| RMSE fraction approximation | 244 | 165 | 158 | 110 | 92 | 27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Witaszek, K.; Shvorov, S.; Opryshko, A.; Dudnyk, A.; Zhuk, D.; Łukomska, A.; Dach, J. Biomethane Yield Modeling Based on Neural Network Approximation: RBF Approach. Energies 2026, 19, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010113

Witaszek K, Shvorov S, Opryshko A, Dudnyk A, Zhuk D, Łukomska A, Dach J. Biomethane Yield Modeling Based on Neural Network Approximation: RBF Approach. Energies. 2026; 19(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010113

Chicago/Turabian StyleWitaszek, Kamil, Sergey Shvorov, Aleksey Opryshko, Alla Dudnyk, Denys Zhuk, Aleksandra Łukomska, and Jacek Dach. 2026. "Biomethane Yield Modeling Based on Neural Network Approximation: RBF Approach" Energies 19, no. 1: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010113

APA StyleWitaszek, K., Shvorov, S., Opryshko, A., Dudnyk, A., Zhuk, D., Łukomska, A., & Dach, J. (2026). Biomethane Yield Modeling Based on Neural Network Approximation: RBF Approach. Energies, 19(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010113