Research on Direct Air Capture: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. DAC Principles and Key Technologies

2.1. DAC Principle

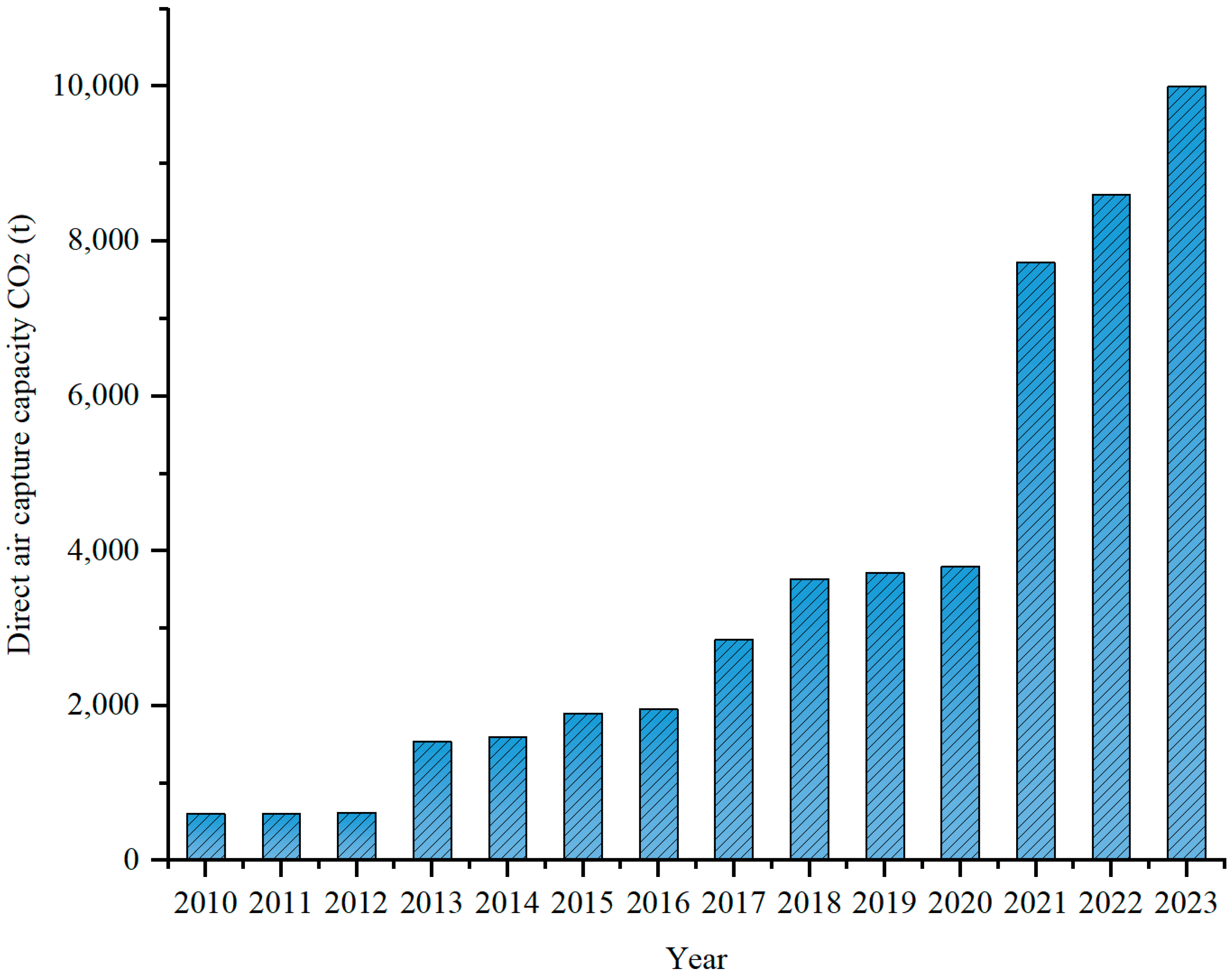

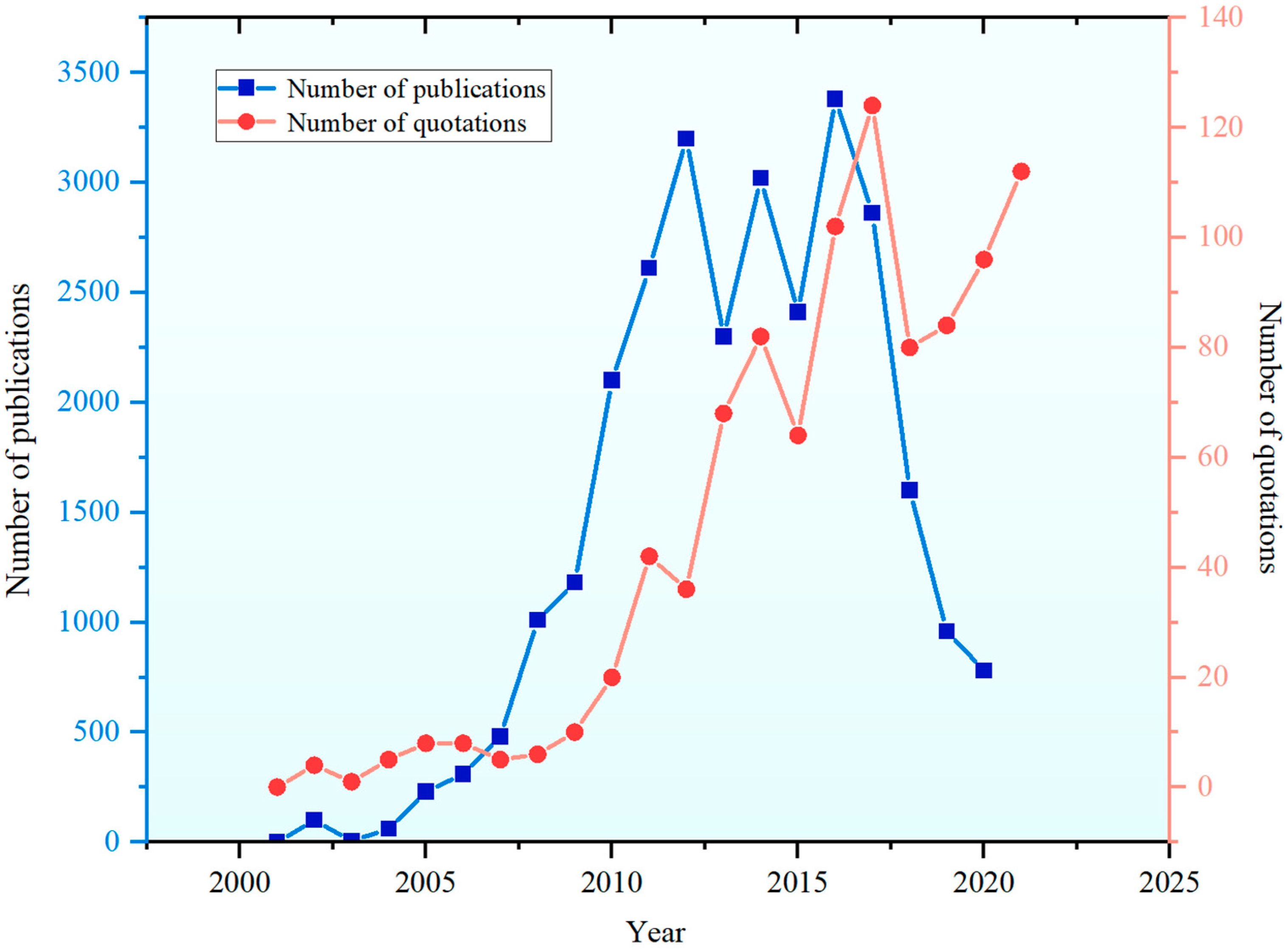

2.2. Key DAC Technologies

2.2.1. Liquid Absorption Method

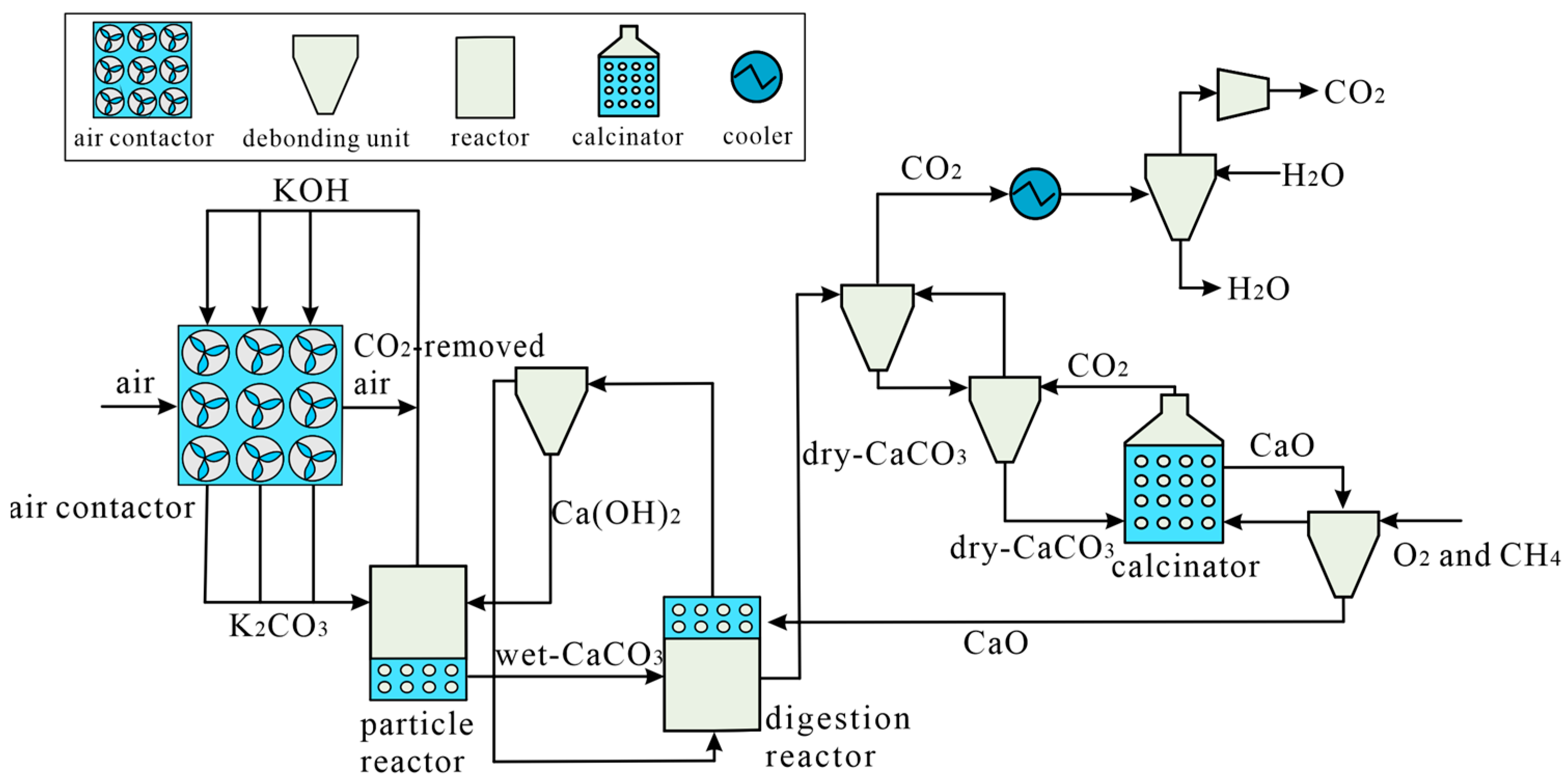

DAC Technology for Alkaline Hydroxide Solutions

Amino Acid Solution DAC Technology

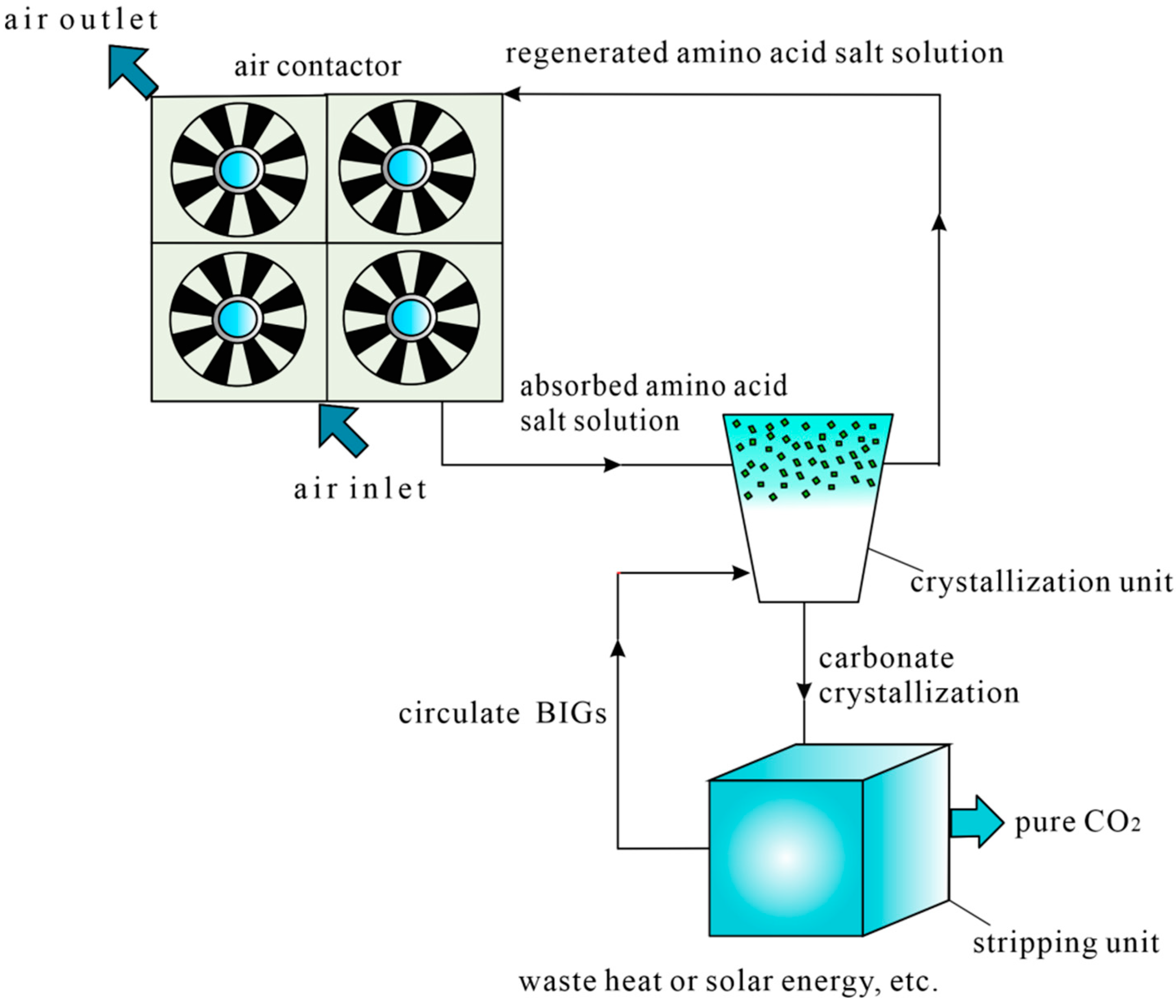

Amino Acid Salt Solution DAC Technology

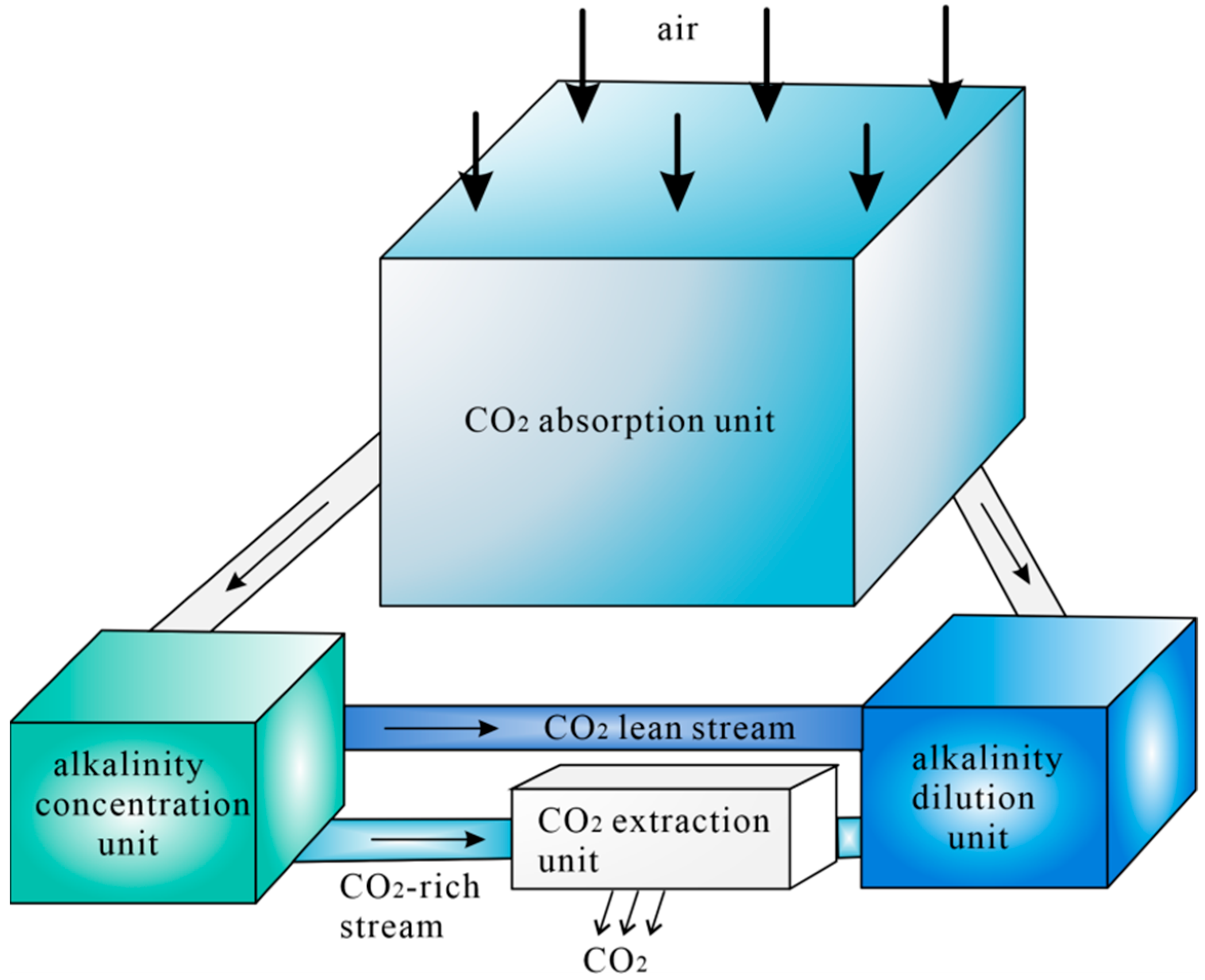

DAC Technology for Alkalinity Concentration Variation

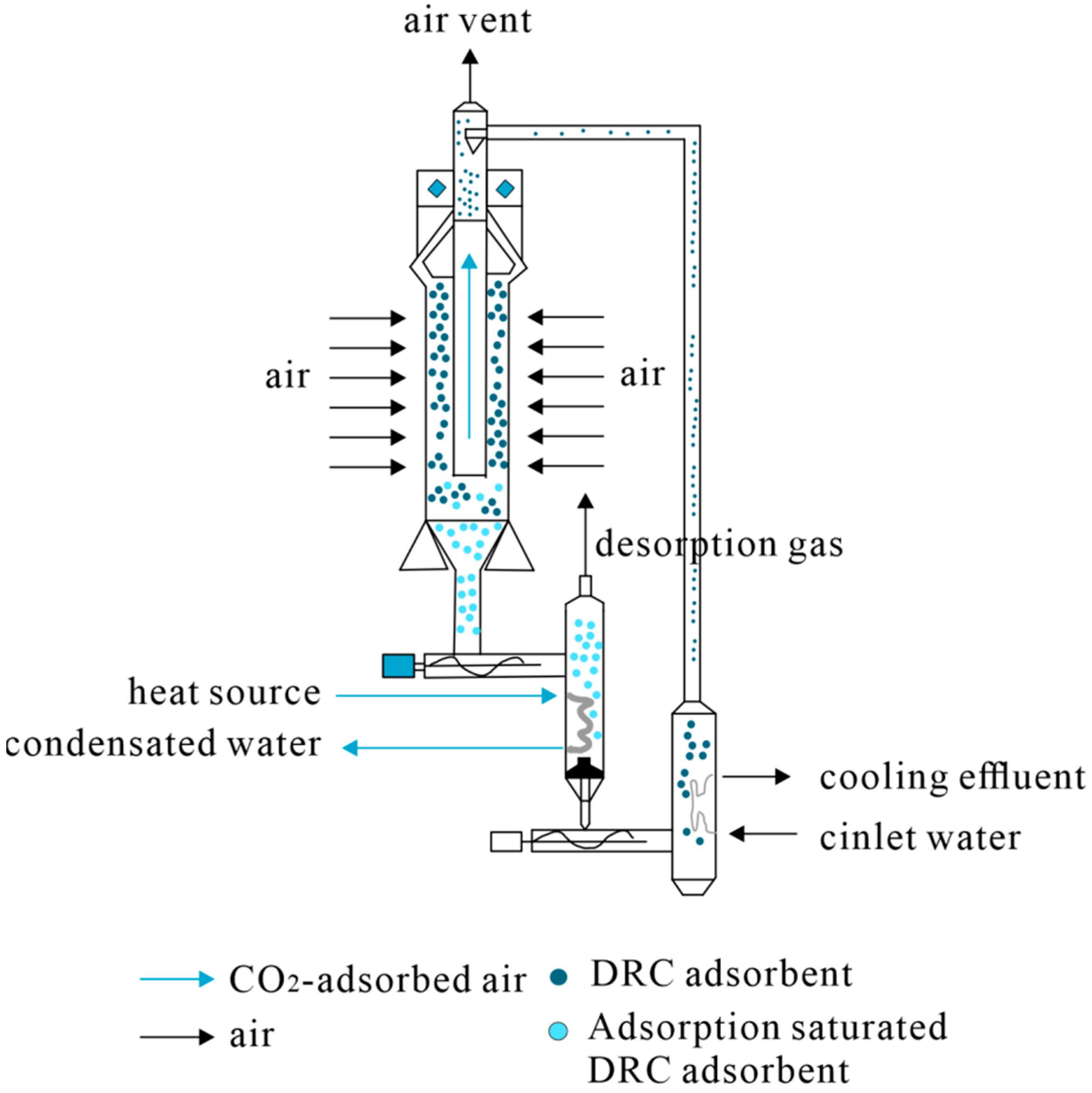

2.2.2. Solid Adsorption Method

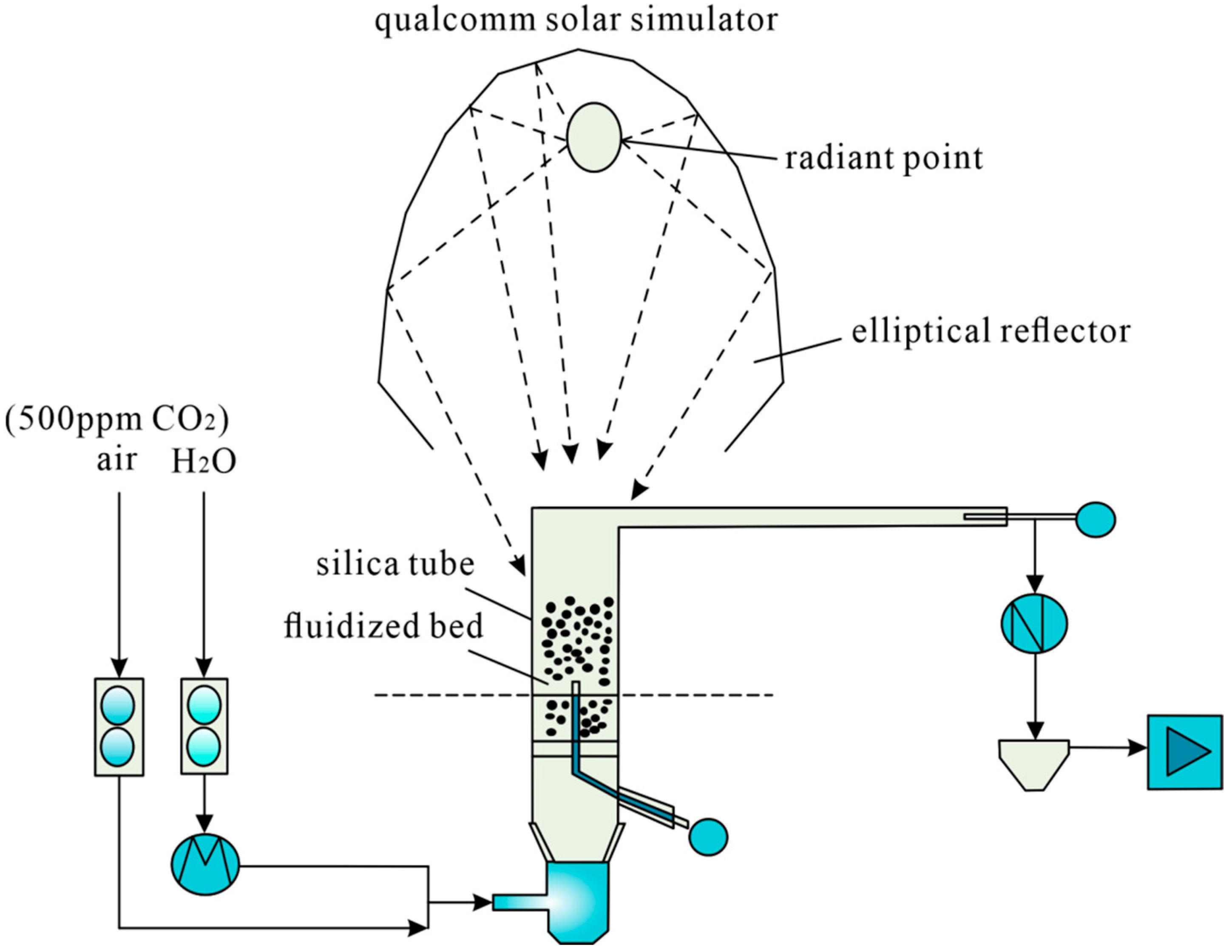

Solid Alkali (Alkali Earth) Metal DAC Technology

Solid-State Amine Adsorption DAC Technology

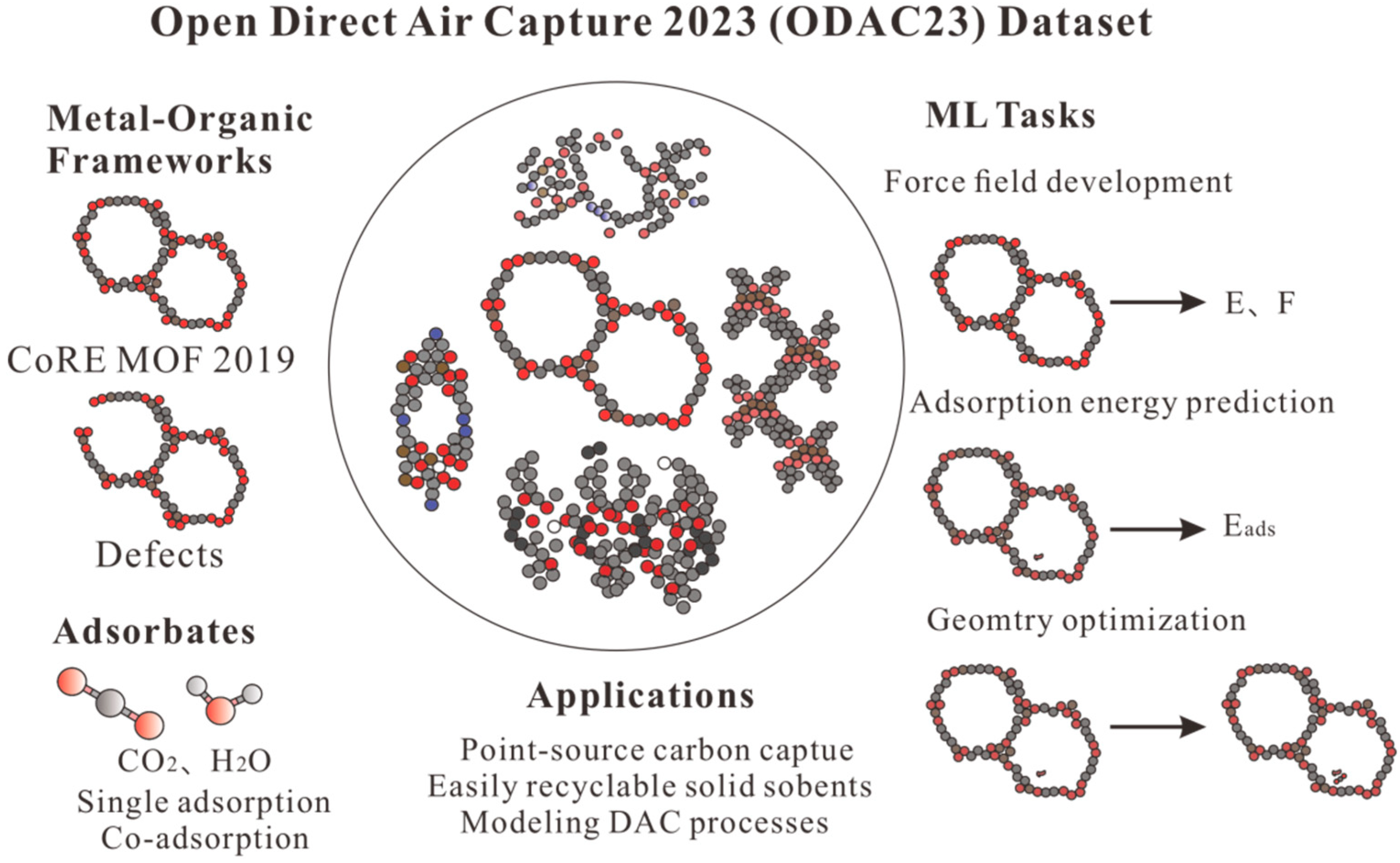

DAC Technology for MOF Materials

Graphene Adsorbent DAC Technology

Activated Carbon Adsorption DAC Technology

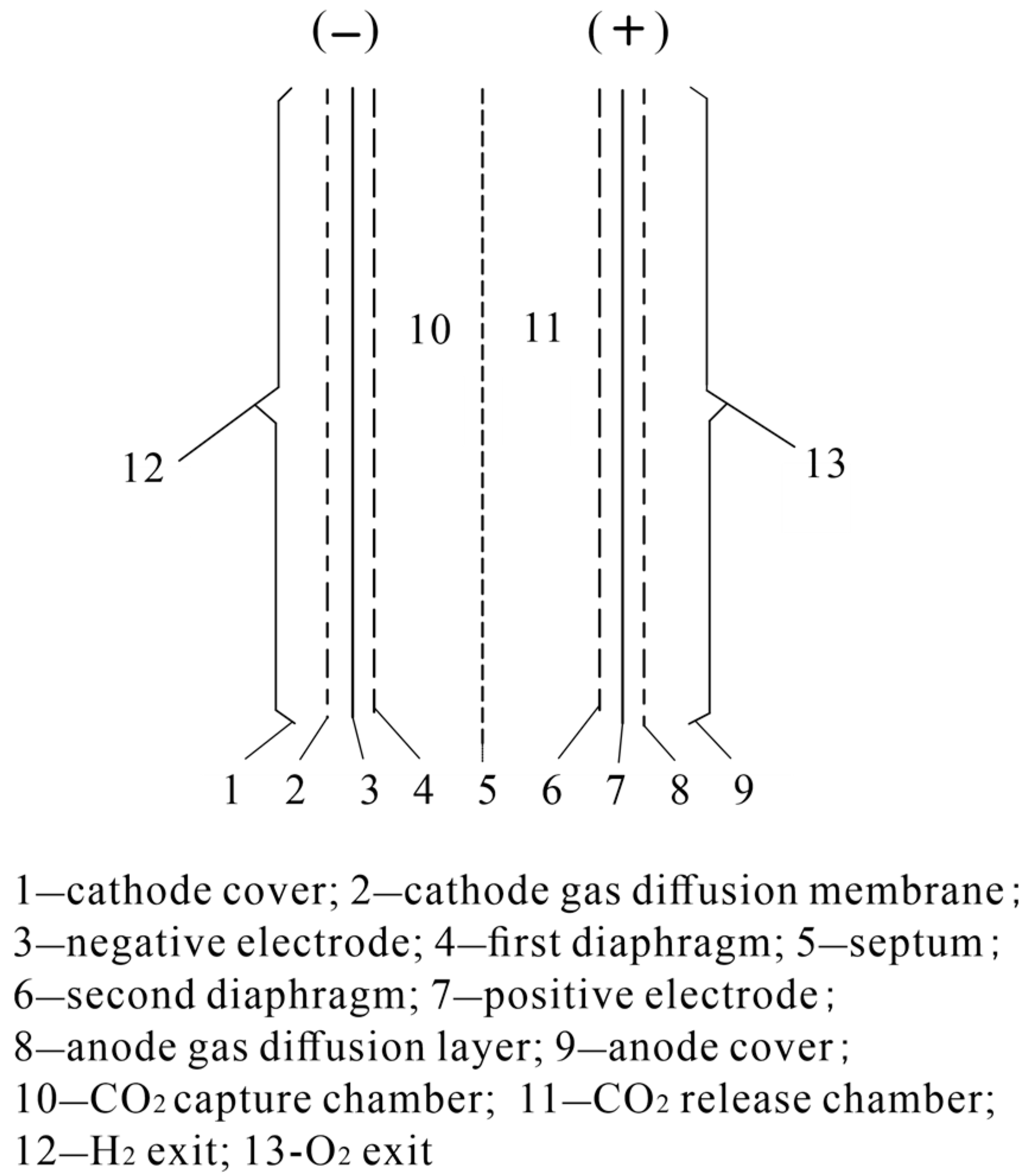

2.2.3. Other DAC Technologies

2.2.4. Comparison of Advantages and Disadvantages of Various DAC Technologies

3. DAC Technology Equipment and Adsorption Materials

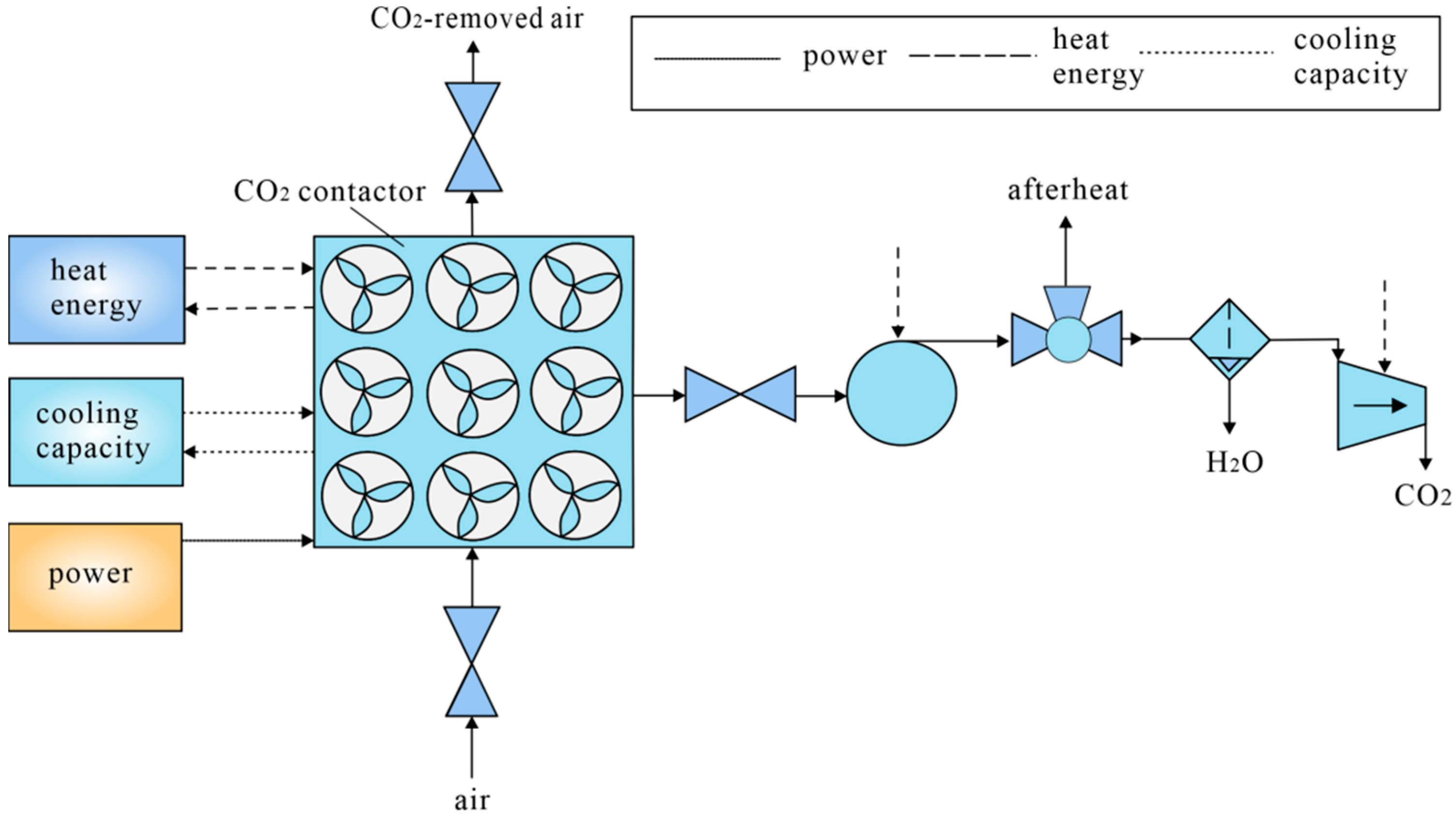

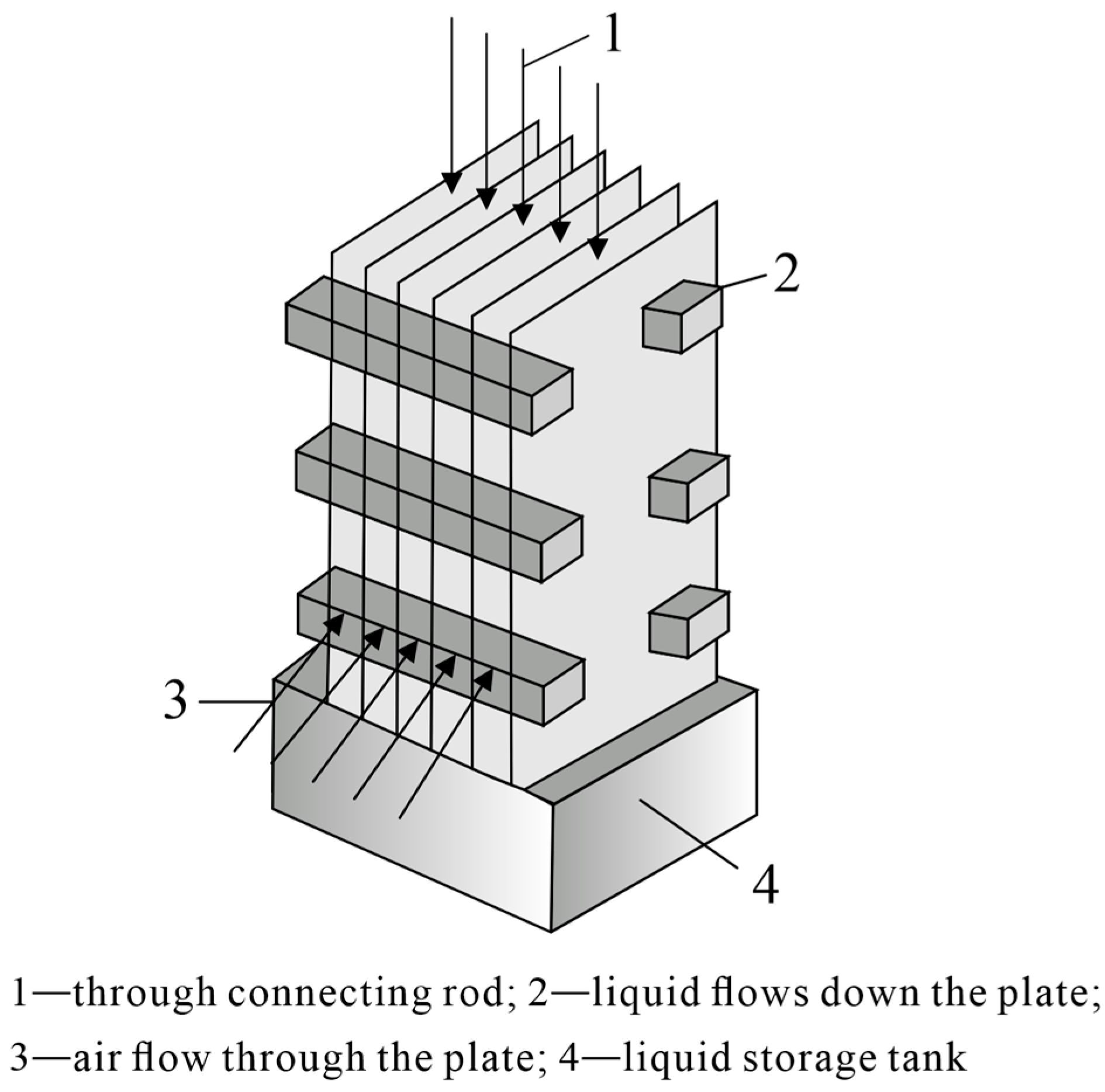

3.1. DAC Technology Equipment

3.2. DAC Adsorption Materials

4. DAC Adsorption Efficiency, Energy Consumption, and Costs

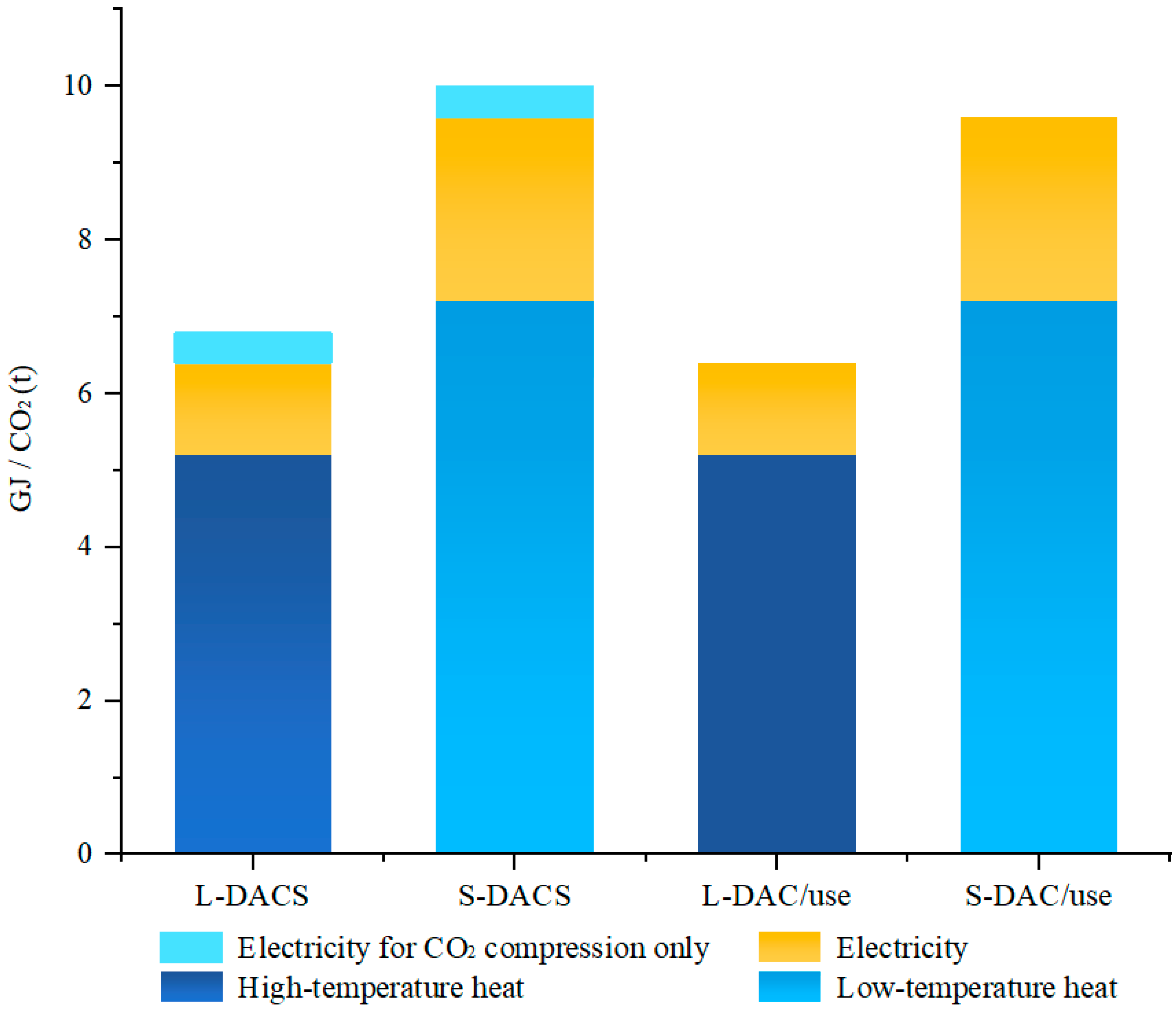

4.1. Adsorption Efficiency and Energy Consumption of DAC

| Parameter | Solid Adsorbent [173] | Liquid Solvent [174] | Analysis and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy requirement (MW) | 126–188 | 315–439 | Solid systems are usually more energy-efficient. |

| Electrical requirements (MW) | 18–35 | 23–52 | Electricity is the core cost for solids, making them price-sensitive. Thermal energy dominates for liquids, so power costs matter less. |

| Thermal energy requirements (MW) | 108–152 | 291–386 | Solid systems are more energy-flexible, able to use low-grade or renewable heat, while liquid systems require high-grade, demanding heat sources. |

| Energy consumption structure | Electricity Combined electrical and thermal consumption | Thermal consumption is the absolute dominant factor. | Cost reduction strategies differ: solids must optimize electricity use, while liquids need affordable, low-carbon heat. |

| Primary energy consumption stages | Adsorption bed forced ventilation, vacuum regeneration, temperature swing | Solution pumping, solvent regeneration (particularly calcination) | The process bottlenecks differ fundamentally: liquids are limited by the thermodynamics of high-temperature calcination, while solids are constrained by mass transfer kinetics. |

| Technology Maturity | mid-to-low | mid-to-high | Liquid solvent technology is more mature but has a high energy ceiling. Solid adsorbent technology is novel with greater optimization potential, but its scalability is uncertain. |

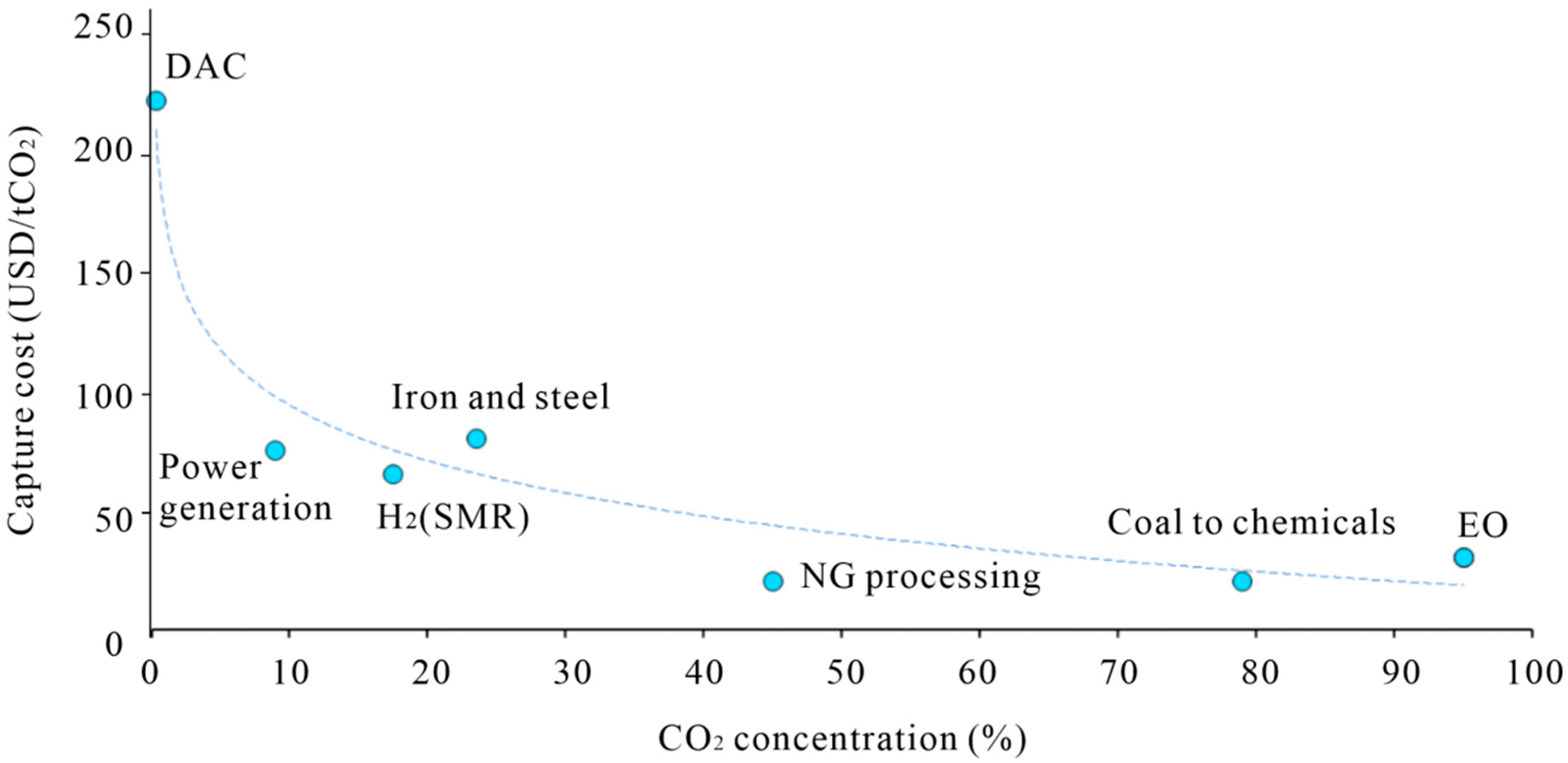

4.2. DAC Costs

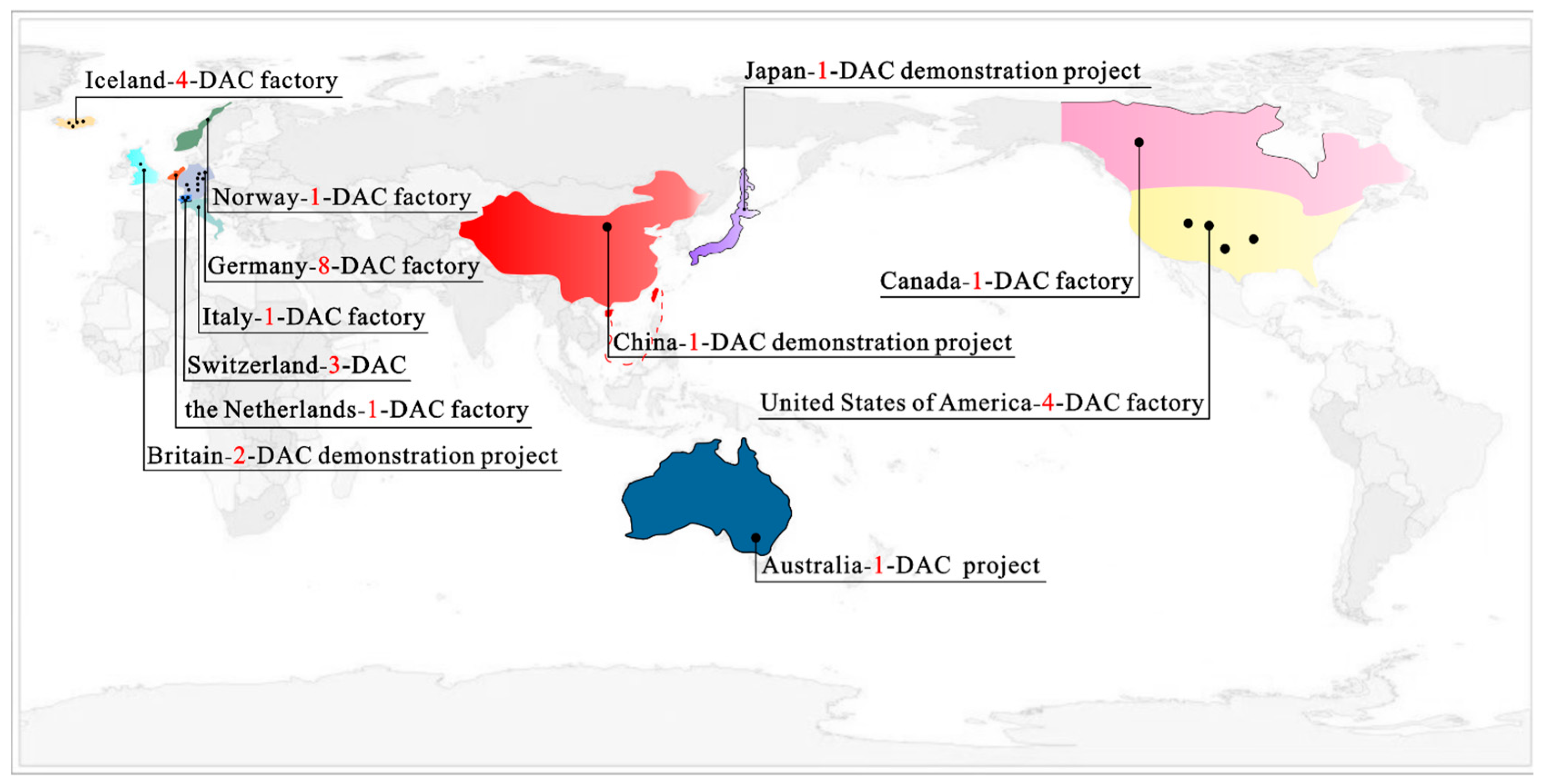

5. Development Status and Industrialization of DAC

5.1. Analytical Methodological Framework

5.2. Global Landscape and Regional Policy Drivers

5.3. Analysis of Key Corporate Players: Technology Pathways and Commercialization Strategies

| Company/Location | Year Founded | Primary Technology | Example Project/Capacity | Commercialization Strategy and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climeworks (Switzerland) [20]. | 2009 | Solid Sorbent | 900 t CO2/year (2017, Switzerland) | Incremental deployment, starting with small-to-medium pilots to validate technology and serve niche markets (e.g., greenhouses, beverages). |

| Carbon Engineering (Canada) [169] | 2009 | Liquid Solvent | Planning megatonne-scale projects | Scale-up path, aiming for low-cost capture directly via large-scale facilities, targeting geological storage. |

| Global Thermostat (New York, NY, USA) [184] | 2010 | Ion-Exchange Sorbent | ≈100 t CO2/plant per year | Multi-project approach, leveraging a differentiated technology and exploring various scales and applications. |

| Susteon (Morrisville, NC, USA) [185] | 2008 | Solid Sorbent (similar to Climework) | Not Applicable (focus on integrated solutions | Business model innovation, focusing on integrated “capture-and-utilization” solutions, complements DACCS pathways. |

5.4. Assessment of Industrialization Level and Key Challenges Discussion

5.5. Summary of Industrialization Status

6. Discussion and Future Perspectives

6.1. DAC and the Energy Industry

6.1.1. DAC and the Traditional Energy Industry

6.1.2. DAC and the New Energy Industry

6.2. DAC and Artificial Intelligence

6.2.1. DAC Challenges and AI Opportunities

6.2.2. Innovative Method 1: High-Throughput Virtual Screening and Molecular-Level Rational Design

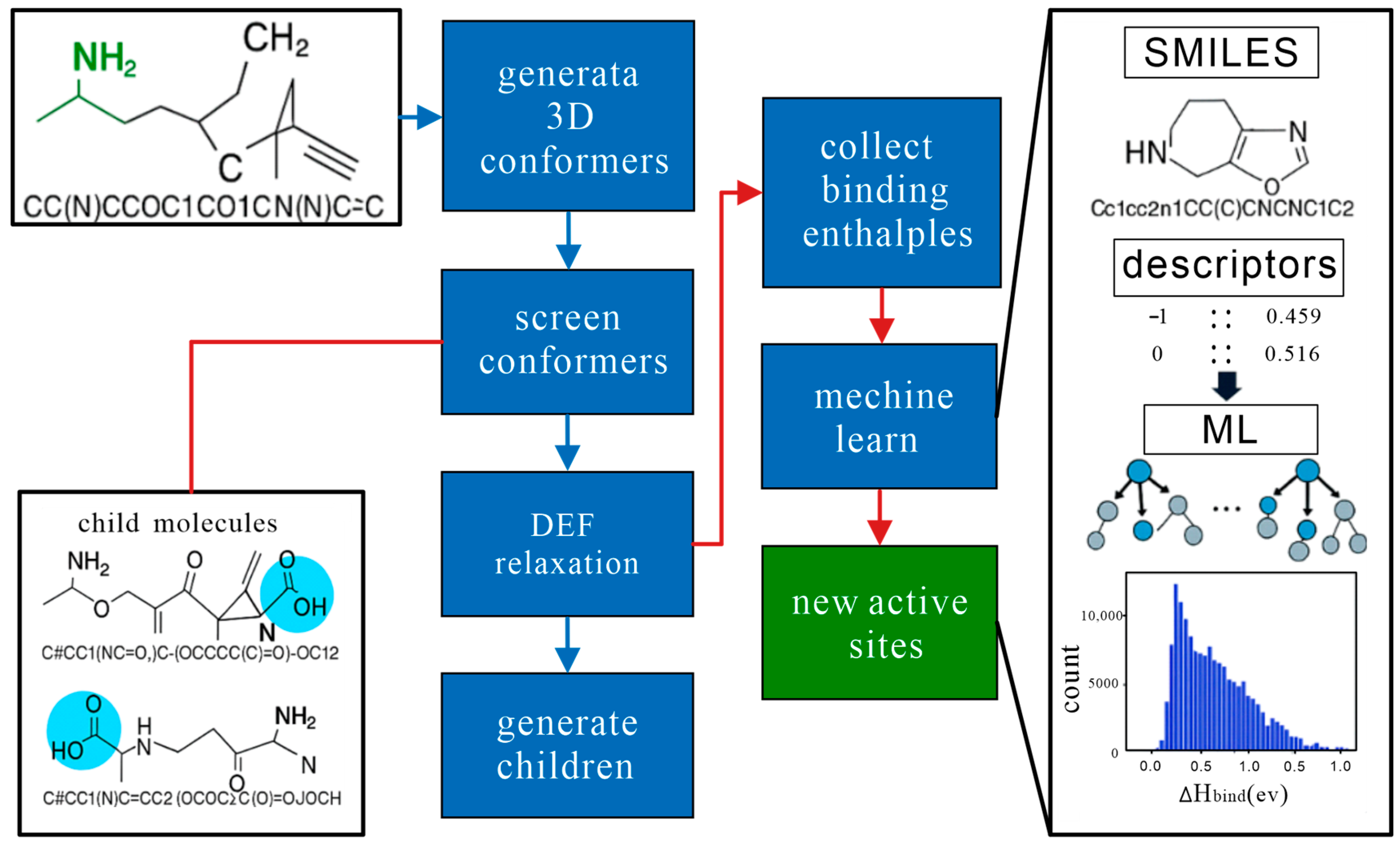

6.2.3. Innovative Method 2: Intelligent Generative and Inverse Design

6.2.4. Paradigm Upgrade: SMART Framework and Closed-Loop R&D

6.2.5. Concluding Remarks and Outlook for AI in DAC

6.3. Lifecycle Environmental Performance and Societal Acceptance

6.3.1. Lifecycle Greenhouse-Gas Balance of DAC

6.3.2. Water Consumption and Water-Related Risks

6.3.3. Land Occupation and Siting

6.3.4. Societal Acceptance and Distributional Aspects of DAC

6.3.5. Policy and Accounting Frameworks Relevant to DAC

6.4. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DAC | Direct Air Capture |

| MOFs | Metal–organic Frameworks |

| DACM | Direct Air Carbonation with Methanation |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| ACSDAC | Alkaline Solution Concentration-based DAC |

| BIGs | Bis-iminoguanidines |

| ACS | Alkalinity Concentration Swing |

| TVSA | Temperature-Vacuum-Swing Adsorption |

| MEA | monoethanolamine |

| COFs | Covalent Organic Frameworks |

| OMS | Open Metal Sites |

| AFS | Amine-functionalized Sites |

| DFMs | Dual-function Materials |

| LISA | Light-induced Swing Adsorption |

| CR-DAC | Continuous Rotating Direct Air Capture |

| DACCS | Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage |

| S-DAC | Solid Sorbent Direct Air Capture |

| L-DAC | Liquid Solvent Direct Air Capture |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| AHA-ILs DAC | Amino Acid Salt-Ionic Liquid Direct Air Capture |

| BECCS | Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CCUS | Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage |

| EOR | Enhanced Oil Recovery |

| TRLs | Technology Readiness Levels |

| GNNs | Graph Neural Networks |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| FF | Force Fields |

| SMART | Scalable Modeling, Artificial Intelligence, Rapid Theoretical Calculations |

| BWDPCs | Biomass-derived Porous Carbons |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

Appendix A

| DAC Technical Designation | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAC technology for alkaline hydroxide solutions | Technologically mature, with a high absorption rate | High regeneration temperature and high energy consumption during regeneration result in significant water loss | [28,32] |

| Amines solution DAC technology | The absorption rate is relatively high | Accompanied by the volatilization of the amine solution, and with relatively low regeneration efficiency | [32] |

| Amino acid salt solution DAC technology | High absorption rate, low regeneration temperature, minimal solvent loss | Energy consumption is relatively high, and capture efficiency varies depending on the amino acid salt solution | [32,69] |

| Alkalinity concentration variation DAC technology | High absorption rate, low regeneration temperature, and energy consumption, suitable for collaboration with seawater desalination research | Capture efficiency correlates with solution concentration techniques, requiring substantial water consumption | [69,109] |

| Solid alkali (alkali earth) metal DAC technology | High adsorption efficiency, good regeneration stability | Regeneration entails higher energy consumption and associated costs | [28] |

| Solid-state amine adsorption DAC technology | Technologically mature, featuring high adsorption rates and low regeneration temperatures | The thermal stability of adsorbents warrants further enhancement | [28] |

| Metal–organic framework materials DAC technology | Offers application advantages at lower temperatures | Capture efficacy is significantly influenced by ambient water content, with relatively high raw material costs | [109] |

| Dewet absorption DAC technology | High adsorption and desorption rates, coupled with low regeneration temperatures and energy consumption | High water consumption with stringent water quality requirements, yielding a low partial pressure of carbon dioxide | [28,32] |

| DAC combined ethaneation technology | Enables simultaneous carbon dioxide capture and conversion, with minimal humidity sensitivity | Requires elevated regeneration temperatures, with catalysts playing a decisive role | [32,109] |

| Light-Induced oscillatory adsorption DAC technology | Low regeneration energy consumption | Requires the incorporation of photoreactive elements within the material | [69] |

| DAC technology for nitrate assimilation in phytoplankton | Low regeneration energy consumption, suitable for seawater applications | Capture efficiency is primarily dependent on microbial activity | [69,109] |

| Material Properties | Material Type | Characteristics | Cost | Renewable Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical adsorption materials | MOFs | Its structure is stable, exhibiting a high specific surface area and porosity, enabling efficient CO2 capture through structural modification | High production costs | Due to its adjustable porosity and moderate regenerative energy |

| Activated carbon | Its large specific surface area and porosity enable low-cost, efficient capture of CO2 | Low cost | Due to the high specific surface area and mild activation, the regeneration energy is low | |

| Silica gel | It is frequently employed for dehumidification and air purification due to its low cost | Low cost | Due to its stable and reusable nature, the regeneration energy is low | |

| Molecular sieve | Adsorption facilitates separation and purification by screening molecular sizes | Moderate cost | High regeneration energy may be attributable to specific adsorption properties | |

| Zeolite | Adsorption capacity can be enhanced through ion exchange and other modification techniques | Moderate cost | Regeneration energy varies according to type and modification method | |

| Mesoporous silica | Despite its high porosity, weak interactions with CO2 result in limited adsorption capacity Consequently, surface modification presents an attractive strategy for improving CO2 capture efficiency in DAC | Low cost | Additional energy is required for surface modification to enhance CO2 capture | |

| Chemical adsorption materials | Alkali metal-based adsorbents | It can capture CO2 and form stable compounds. Its adsorption capacity and selectivity | Due to raw material costs, the expense is moderately high | Due to raw material costs, the expense is moderately high |

| Solid amine adsorbents | Despite the considerable cost associated with desorption, it exhibits a high adsorption rate | Owing to the higher temperatures required, regeneration energy consumption is elevated | Owing to the higher temperatures required, regeneration energy consumption is elevated |

| Capture Capacity | Adsorbent | Desorption Temperature (°C) | Energy Consumption | Cost (USD/tonne) | Scale Assumption | Region Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mt/a | KOH | 900 | 8.81 GJ/t | 94–232 | Medium scale | Standard |

| 1 Mt/a | KOH | 900 | 5.25 GJ/t + 366 kWh/t | 94–232 | Medium scale | Standard |

| 1 Mt/a | KOH | 900 | 1535 kWh/t | 186 | Medium scale | Standard |

| 0.291 t/h | MEA | 123.1 | 1452 kWh/t | 676 | Small scale | Standard |

| 0.36 Mt/a | K2CO3 | 80–100 | 7.5 GJ/t + 694 kWh/t | 135–177 | Small scale | Low-cost regions |

| 3600 t/a | K2CO3 | 80–100 | 7.5 GJ/t + 694 kWh/t | 203–244 | Large scale | Low-cost regions |

| - | CaO | 875 | 2.09 GJ/t | - | Medium scale | Standard |

| - | K2CO3/γ-Al2O3 | 150 | 7.3 GJ/t + 0.27 GJ/t | - | Medium scale | Standard |

| 300 t/a | Amino groups | 100 | 5.4–7.2 GJ/t + 200–300 Wh/t | Expected on a large scale 75 | Small scale | Standard |

| - | Amino polymers | 85–95 | 4.2–5.1 GJ/t + 150–260 Wh/t | <113 | Small scale | Standard |

| - | Amino polymers | 75 | - | ≤50 | Small scale | Standard |

| 140 g/day | Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) | 80, Vacuum | - | 34–350 | Small scale | Standard |

| 166.08 t/h | Wet-activated adsorbents + amine solutions | - | 306 GJ/t | 93.1 | Medium scale | High-efficiency |

| 365 t/a | Wet-activated adsorbents | Wet | 316 kWh/t | 99 | Medium scale | Standard |

| - | Wet-activated adsorbents | 45 | 0.81 GJ/t | 34.68 | Medium scale | Standard |

| - | Amino acid salt solutions/m-BBIG | 60–120 | 8.2 GJ/t | - | Medium scale | Standard |

| - | Amino acid salt solutions/PyBIG | 80–120 | 6.5 GJ/t | - | Medium scale | Standard |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy-Related CO2 Emissions by Fuel Type, 1990–2040 (Billion Metric Tons). In World Energy Outlook 2023; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Erans, M.; Sanz-Pérez, E.S.; Hanak, D.P.; Clulow, Z.; Reiner, D.M.; Mutch, G.A. Direct Air Capture: Process Technology, Techno-Economic and Socio-Political Challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 1360–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Annual Greenhouse Gas Index (AGGI). 2 November 2025. Available online: https://gml.noaa.gov/aggi/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Global Climate Change: Carbon Dioxide. 2 November 2025. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Mauna Loa CO2 Monthly Mean Data. Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML). 2025. Available online: https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- IPCC. AR6 WGI: Greenhouse Gas Lifetimes, Radiative Efficiencies, and Metrics (Chapter 7 Supplementary Material); Applied Science Commons: Geneva, Switzerland; IPCC, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Resources Institute. 4 Charts Explain Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: An IPCC Special Report, Chapter 4: Mitigation and Development Pathways; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Minx, J.C.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Fuss, S.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; Garcia, W.d.O.; Hartmann, J.; et al. Negative Emissions-Part 1: Research Landscape and Synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, S.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; Garcia, W.d.O.; Hartmann, J.; Khanna, T.; et al. Negative Emissions-Part 2: Costs, Potentials and Side Effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Sato, M.; Kharecha, P.; von Schuckmann, K.; Beerling, D.J.; Cao, J.; Marcott, S.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Prather, M.J.; Rohling, E.J.; et al. Young People’s Burden: Requirement of Negative CO2 Emissions. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2017, 8, 577–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Muñoz, R.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Malankowska, M.; Coronas, J. A New Relevant Membrane Application: CO2 Direct Air Capture (DAC). Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Gomes, K.V.; McCormick, C.; Blumanthal, K.; Pisciotta, M.; Wilcox, J. A Review of Direct Air Capture (DAC): Scaling up Commercial Technologies and Innovating for the Future. Prog. Energy 2021, 3, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, M.; Patel, S.; Some, S. Climate Change Mitigation and Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence and Research Gaps. PLoS Clim. 2024, 3, E0000366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Action on Climate and SDGs; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, W.; Xu, R.; Gao, H.; Duan, L. Analysis of the Development of Direct Capture of Carbon Dioxide in the Air from a Patent Perspective. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2023, 29, 86–97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Direct Air Capture—Analysis (Tracking Clean Energy Progress); IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/carbon-capture-utilisation-and-storage/direct-air-capture (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Ozkan, M.; Nayak, S.P.; Ruiz, A.D.; Jiang, W. Current Status and Pillars of Direct Air Capture Technologies. iScience 2022, 25, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodiq, A.; Abdullatif, Y.; Aissa, B.; Ostovar, A.; Nassar, N.; El-Naas, M.; Amhamed, A. A Review on Progress Made in Direct Air Capture of CO2. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 29, 102991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuff, M. Will Sucking Carbon from Air Ever Really Help Tackle Climate Change? New Scientist. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2431089-will-sucking-carbon-from-air-ever-really-help-tackle-climate-change/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Hemmatifar, A.; Kang, J.S.; Ozbek, N.; Tan, K.; Hatton, T.A. Electrochemically Mediated Direct CO2 Capture by Stackable Bipolar Cell. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, E202102533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q. Charged Sorbents for Direct Air Capture: A Commentary. Green Carbon 2024, 2, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, F.; Grimm, A.; Gallucci, F.; van Sint Annaland, M.; Feron, P.H.M. A Comparative Energy and Cost Assessment and Optimization for Direct Air Capture Technologies. Joule 2021, 5, 2047–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochelle, G.T. Amine Scrubbing for CO2 Capture. Science 2009, 325, 1652–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdock, C.R.; Didas, S.A.; Jones, C.W.; Sanz-Pérez, E.S. Direct Capture of CO2 from Ambient Air. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840–11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.W. CO2 Capture from Dilute Gases as a Component of Modern Global Carbon Management. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2011, 2, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, F. Energy and Material Balance of CO2 Capture from Ambient Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 7558–7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolaroff, J.K.; Keith, D.W. Carbon Dioxide Capture from Atmospheric Air Using Sodium Hydroxide Spray. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 2728–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinberg, A.; Bergman, A.M.; Schrag, D.P.; Aziz, M.J. Alkalinity Concentration Swing for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 4439–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinberg, A. Concentrating Alkalinity for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide: Using Osmotic Pressure for Concentration and Separation. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, A.M. Using Capacitive Deionization for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide: Theory and Demonstration of the Bicarbonate-Enriched Alkalinity Concentration Swing. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Lackner, K.S.; Wright, A. Moisture Swing Sorbent for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Ambient Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6670–6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xiao, H.; Azarabadi, H.; Song, J.; Wu, X.; Lackner, K.S.; Chen, X. Sorbents for the Direct Capture of CO2 from Ambient Air. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6984–7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zick, M.E.; Trisukhon, T.; Signorile, M.; Liu, X.; Eastmond, H.; Sharma, S.; Spreng, T.L.; Taylor, J.; Gittins, J.W.; et al. Capturing Carbon Dioxide from Air with Charged Sorbents. Nature 2024, 630, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, A.; McQuillan, R.V.; Alivand, M.S.; Zavabeti, A.; Stevens, G.W.; Mumford, K.A. Direct Air Capture of CO2 Using Green Amino Acid Salts. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 480, 147934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltman, K.; Singh, B.; Hertwich, E.G. Human and Environmental Impact Assessment of Post-Combustion CO2 Capture Focusing on Emissions from Amine-Based Scrubbing Solvents to Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougie, F.; Fan, X. Microwave Regeneration of Monoethanolamine Aqueous Solutions Used for CO2 Capture. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2018, 79, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougie, F.; Iliuta, M.C. Analysis of Regeneration of Sterically Hindered Alkanolamine Aqueous Solutions with and without Activator. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 4746–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Balasubramanian, R. Highly Efficient, Rapid and Selective CO2 Capture by Thermally Treated Graphene Nanosheets. J. CO2 Util. 2016, 13, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsianos, A.; Hamdy, L.B.; Yoo, C.-J.; Lee, J. Drastic Enhancement of Carbon Dioxide Adsorption in Fluoroalkyl-Modified Poly(Allylamine). J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 10827–10837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, J.-T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.T. CO2 Capture (Including Direct Air Capture) and Natural Gas Desulfurization of Amine-Grafted Hierarchical Bimodal Silica. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.S.; Dogan, N.A.; Lim, H.; Yavuz, C.T. Amine Chemistry of Porous CO2 Adsorbents. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 2642–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, R.B.; Kolle, J.M.; Essalah, K.; Tangour, B.; Sayari, A. A Unified Approach to CO2-Amine Reaction Mechanisms. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 26125–26133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.; Choi, W.; Kim, C.; Choi, M. Oxidation-Stable Amine-Containing Adsorbents for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q. Recent Advances in Solid Sorbents for CO2 Capture and New Development Trends. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3478–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, J.; Maeda, N.; Meier, D.M. Review on CO2 Capture Using Amine-Functionalized Materials. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 39520–39530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Reddy, K.S.K.; Singh, S.; Karanikolos, G.N. Recent Advances in Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture and Storage Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 386, 124022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bordejé, E.; González-Olmos, R. Advances in Process Intensification of Direct Air CO2 Capture with Chemical Conversion. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 100, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesiri, R.P.; Knowles, G.P.; Yeasmin, H.; Chaffee, A.L. CO2 Capture from Air Using Pelletized Polyethylenimine-Impregnated MCF Silica. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 3293–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeppert, A.; Zhang, H.; Sen, R.; Prakash, G.K.S.; Olah, G.A. Oxidation-Resistant, Cost-Effective Epoxide-Modified Polyamine Adsorbents for CO2 Capture from Various Sources Including Air. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1712–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didas, S.A.; Choi, S.; Chaikittisilp, W.; Jones, C.W. Amine-Oxide Hybrid Materials for CO2 Capture from Ambient Air. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2680–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeppert, A.; Czaun, M.; Prakash, G.K.S.; Olah, G.A. Air as the Renewable Carbon Source of the Future: An Overview of CO2 Capture from the Atmosphere. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 7833–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Pérez, E.S.; Fernández, A.; Arencibia, A.; Calleja, D.; Sanz, R. Hybrid Amine-Silica Materials: Determination of N Content by 29Si NMR and Application to Direct CO2 Capture from Air. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 373, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, H.; Issa, A.; Rownaghi, A.A.; Rezaei, F. CO2 Capture from Air Using Amine-Functionalized Kaolin-Based Zeolites. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2017, 40, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhong, M.; Konkolewicz, D.; Matyjaszewski, K. Carbon Black Functionalized with Hyperbranched Polymers: Synthesis, Characterization, and Application in Reversible CO2 Capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 6810–6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzuchowski, P.G.; Stefanska, M.; Swiderska, A.; Sieron, L. Hyperbranched Polyglycerols Containing Amine Groups-Synthesis, Characterization and Carbon Dioxide Capture. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 27, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Drese, J.H.; Eisenberger, P.M.; Jones, C.W. Application of Amine-Tethered Solid Sorbents for Direct CO2 Capture from Ambient Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 2420–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikittisilp, W.; Lunn, J.D.; Shantz, D.F.; Jones, C.W. Poly(L-Lysine) Brush-Mesoporous Silica Hybrid Material as a Biomolecule-Based Adsorbent for CO2 Capture from Simulated Flue Gas and Air. Chem. A Eur. J. 2011, 17, 10556–10561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moullec, Y.; Neveux, T.; Al Azki, A.; Broutin, P. Process Modifications for Solvent-Based Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2014, 31, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipp, C.A.; Williams, N.J.; Kidder, M.K.; Custelcean, R.; Holman, K.T. CO2 Capture from Ambient Air by Crystallization with a Guanidine Sorbent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1042–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brethomé, F.M.; Williams, N.J.; Seipp, C.A.; Kidder, M.K.; Custelcean, R. Direct Air Capture of CO2 via Aqueous-Phase Absorption and Crystalline-Phase Release Using Concentrated Solar Power. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custelcean, R.; Williams, N.J.; Garrabrant, K.A.; Agullo, P.; Brethomé, F.M.; Martin, H.J.; Kidder, M.K. Direct Air Capture of CO2 with Aqueous Amino Acids and Solid Bis-Iminoguanidines (BIGs). Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 23338–23346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.; Jiang, K.; Feron, P. Techno-Economic Assessment for CO2 Capture from Air Using a Conventional Liquid-Based Absorption Process. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 539772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, W.M. Explorative Analysis of Advanced Solvent Processes for Energy Efficient Carbon Dioxide Capture by Gas-Liquid Absorption. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2016, 49, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribi, S.; Dubois, L.; De Weireld, G.; Thomas, D. Study of the Post-Combustion CO2 Capture Process by Absorption-Regeneration Using Amine Solvents Applied to Cement Plant Flue Gases with High CO2 Contents. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2019, 90, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldebrant, D.J.; Koech, P.K.; Rousseau, R.; Glezakou, V.-A.; Cantu, D.C.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Zheng, F.; Whyatt, G.; Freeman, C.J. Water-Lean Solvents for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture: Fundamentals, Uncertainties, Opportunities, and Outlook. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9594–9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.J.; Ganesan, A.; Realff, M.J.; Jones, C.W. Direct Air Capture of CO2 Using Poly(ethyleneimine)-Functionalized Expanded Poly(tetrafluoroethylene)/Silica Composite Structured Sorbents. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 40992–41002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, M.; Phillip, W.A. The Future of Seawater Desalination: Energy, Technology, and the Environment. Science 2011, 333, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suss, M.E.; Porada, S.; Sun, X.; Biesheuvel, P.M.; Yoon, J.; Presser, V. Water Desalination via Capacitive Deionization: What Is It and What Can We Expect from It? Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2296–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amshawee, S.; Bin Mohd Yunus, M.Y.; Azoddein, A.A.M.; Hassell, D.G.; Dakhil, I.H.; Keong, L.K. Electrodialysis Desalination for Water and Wastewater: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulshina, V.; Steinfeld, A. CO2 Capture from Air via CaO-Carbonation Using a Solar-Driven Fluidized Bed Reactor: Effect of Temperature and Water Vapor Concentration. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 155, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fang, M.; Wang, T.; Jiang, L. Understandings on Design and Application for Direct Air Capture: From Advanced Sorbents to Thermal Cycles. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 7, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerlein, P.S.; Mansell, J.E.; Ter Laak, T.L.; De Voogt, P. Sorption Behavior of Charged and Neutral Polar Organic Compounds on Solid Phase Extraction Materials: Which Functional Group Governs Sorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.; Blakemore, J.; Milot, R.; Hull, J.; Song, H.; Cai, L. A Visible-Light Water-Splitting Cell with a Photoanode Formed by Co-Deposition of a High-Potential Porphyrin and an Iridium Water-Oxidation Catalyst. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2389–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebald, C.; Wurzbacher, J.A.; Tingaut, P.; Zimmermann, T.; Steinfeld, A. Amine-Based Nanofibrillated Cellulose as Adsorbent for CO2 Capture from Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9101–9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, T.M.; Mason, J.A.; Kong, X.; Bloch, E.D.; Gygi, D.; Dani, A.; Crocellà, V.; Giordanino, F.; Odoh, S.O.; Drisdell, W.S.; et al. Cooperative Insertion of CO2 in Diamine-Appended Metal-Organic Frameworks. Nature 2015, 519, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, V.Y.; Milner, P.J.; Lee, J.; Forse, A.C.; Kim, E.J.; Siegelman, R.L.; McGuirk, C.M.; Zasada, L.B.; Neaton, J.B.; Reimer, J.A.; et al. Cooperative Carbon Dioxide Adsorption in Alcoholamine- and Alkoxyalkylamine-Functionalized Metal-Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 19468–19473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Li, H.; Hanikel, N.; Wang, K.; Yaghi, O.M. Covalent Organic Frameworks for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12989–12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sircar, S.; Golden, T.C.; Rao, M.B. Activated Carbon for Gas Separation and Storage. Carbon 1996, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Reinoso, F.; Molina-Sabio, M. Activated Carbons from Lignocellulosic Materials by Chemical and/or Physical Activation: An Overview. Carbon 1992, 30, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Wu, H.; Yan, X.; Liao, Y.; Li, H. Recent Advances in Intermediate-Temperature CO2 Capture: Materials, Technologies, and Applications. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 90, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sajjadi, B.; Chen, W.-Y.; Chatterjee, R. Ultrasound-Assisted Amine-Functionalized Graphene Oxide for Enhanced CO2 Adsorption. Fuel 2019, 247, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lin, Y.; Hagio, T.; Hu, Y.H. Surface-Microporous Graphene for CO2 Adsorption. Catal. Today 2020, 356, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, S.; Su, H.; Li, D.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, S. Low-cost preferential different amine grafted silica spheres adsorbents for DAC CO2 removal. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 75, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano-Meza, M.; Isaacs-Páez, E.D.; Arjona-Jaime, P.; Chazaro-Ruiz, L.F.; Rangel-Mendez, R. Synthesis and Structural Control of Pillared Graphene Oxide-Chitosan Composites for CO2 Capture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Gan, Z.; Ge, B. CO2 Adsorption Mechanisms and Thermodynamic Analysis on Solid Amine-Based Adsorbents. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 96, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didas, S.A.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Sholl, D.S.; Jones, C.W. Role of Amine Structure on Carbon Dioxide Adsorption from Ultradilute Gas Streams Such as Ambient Air. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 2058–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Sun, S.; Sun, H. Integrated CO2 Capture and Utilization: A Promising Step Contributing to Carbon Neutrality. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 7, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.; Kota, S.; Gao, X.; Katzman, L.; Farrauto, R. Parametric and Laboratory Aging Studies of Direct CO2 Air Capture Simulating Ambient Capture Conditions and Desorption of CO2 on Supported Alkaline Adsorbents. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 6, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, C.; Ebbesen, S.D.; Mogensen, M.; Lackner, K.S. Sustainable Hydrocarbon Fuels by Recycling CO2 and H2O with Renewable or Nuclear Energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Kelemen, P.; Dipple, G.; Renforth, P.; Wilcox, J. Ambient Weathering of Magnesium Oxide for CO2 Removal from Air. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Fan, L. Carbonation-Calcination Cycle Using High Reactivity Calcium Oxide for Carbon Dioxide Separation from Flue Gas. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 4035–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.S.; Hayhurst, A.N. The Effect of CO2 on the Kinetics and Extent of Calcination of Limestone and Dolomite Particles in Fluidized Beds. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1987, 42, 2361–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, K.; Fujimoto, S.; Morita, A.; Kawase, M.; Watanabe, K. Repetitive Carbonation-Calcination Reactions of Ca-Based Sorbents for Efficient CO2 Sorption at Elevated Temperatures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Balen, K. Carbonation Reaction of Lime: Kinetics at Ambient Temperature. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulshina, V.; Hirsch, D.; Mazzotti, M.; Steinfeld, A. CO2 Capture from Air and Coproduction of H2 via the Ca(OH)2-CaCO3 Cycle Using Concentrated Solar Power-Thermodynamic Analysis. Energy 2006, 31, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Legrand, L.; Kuntke, P.; Tedesco, M.; Hamelers, H.V.M. Electrochemical Regeneration of Spent Alkaline Absorbent from Direct Air Capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 8990–8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.R.; Dessì, P.; Cabrera-Codony, A.; Ferrer, I. Indoor CO2 Direct Air Capture and Utilization: Key Strategies towards Carbon Neutrality. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2024, 20, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X. Parametric Study on the Regeneration Heat Requirement of an Amine-Based Solid Adsorbent Process for Post-Combustion Carbon Capture. Appl. Energy 2016, 168, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wargocki, P.; Lian, Z.; Thyregod, C. Effects of Exposure to Carbon Dioxide and Bioeffluents on Perceived Air Quality, Self-Assessed Acute Health Symptoms, and Cognitive Performance. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhabbaz, M.A.; Bollini, P.; Foo, G.S.; Sievers, C.; Jones, C.W. Important Roles of Enthalpic and Entropic Contributions to CO2 Capture from Simulated Flue Gas and Ambient Air Using Mesoporous Silica Grafted Amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13170–13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Ma, J.; Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, D. Design of Alkali Metal Oxide Adsorbent for Direct Air Capture: Identification of Physicochemical Adsorption and Analysis of Regeneration Mechanism. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplow, M. Kinetics of Carbamate Formation and Breakdown. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 6795–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danckwerts, P.V. The Reaction of CO2 with Ethanolamines. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1979, 34, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; He, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S. CO2 Capture and Activation by Superbase/Polyethylene Glycol and Its Subsequent Conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3971–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhah, O.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Chen, Z.; Guillerm, V.; Cairns, A.J.; Adil, K.; Eddaoudi, M. Made-to-Order Metal-Organic Frameworks for Trace Carbon Dioxide Removal and Air Capture. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddaoudi, M.; Kim, J.; Rosi, N.; Vodak, D.; Wachter, J.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Systematic Design of Pore Size and Functionality in Isoreticular MOFs and Their Application in Methane Storage. Science 2002, 295, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, W.S.; Cheun, J.Y.; Kumar, P.S.; Mubashir, M.; Ho, S.H.; Show, P.L.; Ng, E.P. A Review on Conventional and Novel Materials toward Heavy Metal Adsorption in Wastewater Treatment Application. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.R.; Xu, H.J. A Critical Review on Potential Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Adsorptive Carbon Capture Technologies. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.; Liang, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, J. Research Progress on Metal-Organic Framework Composites in Chemical Sensors. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 50, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.Q.; Yu, X.Y.; Tsai, F.C.; Ma, N.; Liu, H.L.; Han, Y.; Li, B. Magnetic MOF for AO7 Removal and Targeted Delivery. Crystals 2018, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, Y. Trace Carbon Dioxide Capture by Metal-Organic Frameworks. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, M.; Akhavi, A.-A.; Coley, W.C. Progress in Carbon Dioxide Capture Materials for Deep Decarbonization. Chem 2022, 8, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhah, O.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Adil, K.; Bhatt, P.M.; Cairns, A.J.; Eddaoudi, M. A Facile Solvent-Free Synthesis Route for the Assembly of a Highly CO2-Selective and H2S-Tolerant NiSIFSIX Metal-Organic Framework. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 13595–13598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Flaig, R.W.; Jiang, H.; Yaghi, O.M. Carbon Capture and Conversion Using Metal-Organic Frameworks and MOF-Based Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2783–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Q. Direct Air Capture of CO2 in Designed Metal-Organic Frameworks at Lab and Pilot Scale. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 9, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmabkhout, Y.; Serna-Guerrero, R.; Sayari, A. Amine-Bearing Mesoporous Silica for CO2 Removal from Dry and Humid Air. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 3695–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cano, Z.P.; Luo, D.; Dou, H.; Yu, A.; Chen, Z. Rational Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Derived Materials for CO2 Capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 20985–21003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Huang, K.; Ding, S.M.; Dai, S. One-Step Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Graphene-like Meso-Macroporous Carbons as High-Performance CO2 Sorbents. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 14567–14571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Huang, S.; Villalobos, L.F. High-Permeance Polymer-Functionalized Single-Layer Graphene Membranes That Surpass the Post-Combustion Carbon Capture Target. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3305–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Mu, Y.; Jin, J.; Chen, J.; Mi, J. Recent Developments and Consideration Issues in Solid Adsorbents for CO2 Capture from Flue Gas. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 2303–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Bai, H.; Wu, B.; Su, F.; Hwang, J.-F. Comparative Study of CO2 Capture by Carbon Nanotubes, Activated Carbons, and Zeolites. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 3050–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coromina, H.M.; Walsh, D.A.; Mokaya, R. Biomass-Derived Activated Carbon with Simultaneously Enhanced CO2 Uptake for Both Pre- and Post-Combustion Capture Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyar, M.S.; Treviño, M.A.A.; Farrauto, R.J. Dual Function Materials for CO2 Capture and Conversion Using Renewable H2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 168–169, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo Bravo, P.; Debecker, D.P. Combining CO2 Capture and Catalytic Conversion to Methane. Waste Biomass Valorization (Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy) 2019, 1, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong-Potter, C.; Abdallah, M.; Sanderson, C. Dual Function Materials (Ru+Na2O/Al2O2) for Direct Air Capture of CO2 and in Situ Catalytic Methanation: The Impact of Realistic Ambient Conditions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 307, 120990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Hatton, T.A. Electrochemical direct air capture of CO2 using neutral red as reversible redox-active material. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.-L.; Wu, Y.-S.; Jiao, Y.-Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, T.; Fang, M.-X.; Zhou, H. Integrated Direct Air Capture and CO2 Utilization of Gas Fertilizer Based on Moisture Swing Adsorption. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2017, 18, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Bailey, J.J.; Huang, Q.; Ke, X.; Wu, C. Potential Photo-Switching Sorbents for CO2 Capture-A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetya, N.; Ladewig, B.P. Dynamic Photo-Switching in Light-Responsive JUC-62 for CO2 Capture. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilm, L.F.B.; Das, M.; Janssen-Müller, D.; Mück-Lichtenfeld, C.; Glorius, F.; Dielmann, F. Photoswitchable Nitrogen Superbases: Using Light for Reversible Carbon Dioxide Capture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, E202112344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wu, Q.; Weng, W.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S. Smart Light-Responsive CO2 Adsorbents for Regulating Strong Active Sites. Acta Chim. Sin. 2020, 78, 1082–1088. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H. Preparation of Photoresponsive CO2 Adsorbent and Study on CO2 Adsorpt. Desorption Perform. 2021, 39, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Xu, X.; Martin, G.J.; Kentish, S.E. Critical Review of Strategies for CO2 Delivery to Large-Scale Microalgae Cultures. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, A.P.; Koyande, A.K.; Chew, K.W.; Ho, S.-H.; Chen, W.-H.; Chang, J.-S.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Banat, F.; Show, P.L. Continuous Cultivation of Microalgae in Photobioreactors as a Source of Renewable Energy: Current Status and Future Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, F. Efficiency, Mechanism, Influencing Factors, and Integrated Technology of Biodegradation for Aromatic Compounds by Microalgae: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathinathan, P.; Parab, H.; Yusoff, R. Photobioreactor Design and Parameters Essential for Algal Cultivation Using Industrial Wastewater: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.L.; Li, M.J.; Martin, G.J.O. Enhancing Direct Air Carbon Capture into Microalgae: A Membrane Sparger Design with Carbonic Anhydrase Integration. Algal Res. 2025, 85, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodium Group. Intellectual Property Rights and Global Direct Air Capture Scale-Up. Rhodium Group. 15 July 2025. Available online: https://www.rhg.com/research/intellectual-property-rights-and-global-direct-air-capture-scale-up (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Wright, A.B.; Lackner, K.S. Removal of Carbon Dioxide from Air. Patent CN101043929A, 26 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.B.; Lackner, K.S.; Peters, E.J. Removal of Oxidized Carbon from Air. Patent CN101128248A, 20 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, D.; Mamaghani, M.; Biglionli, A.; Hart, K.; Haider, M.F. Method and Apparatus for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Patent CN102202766A, 28 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

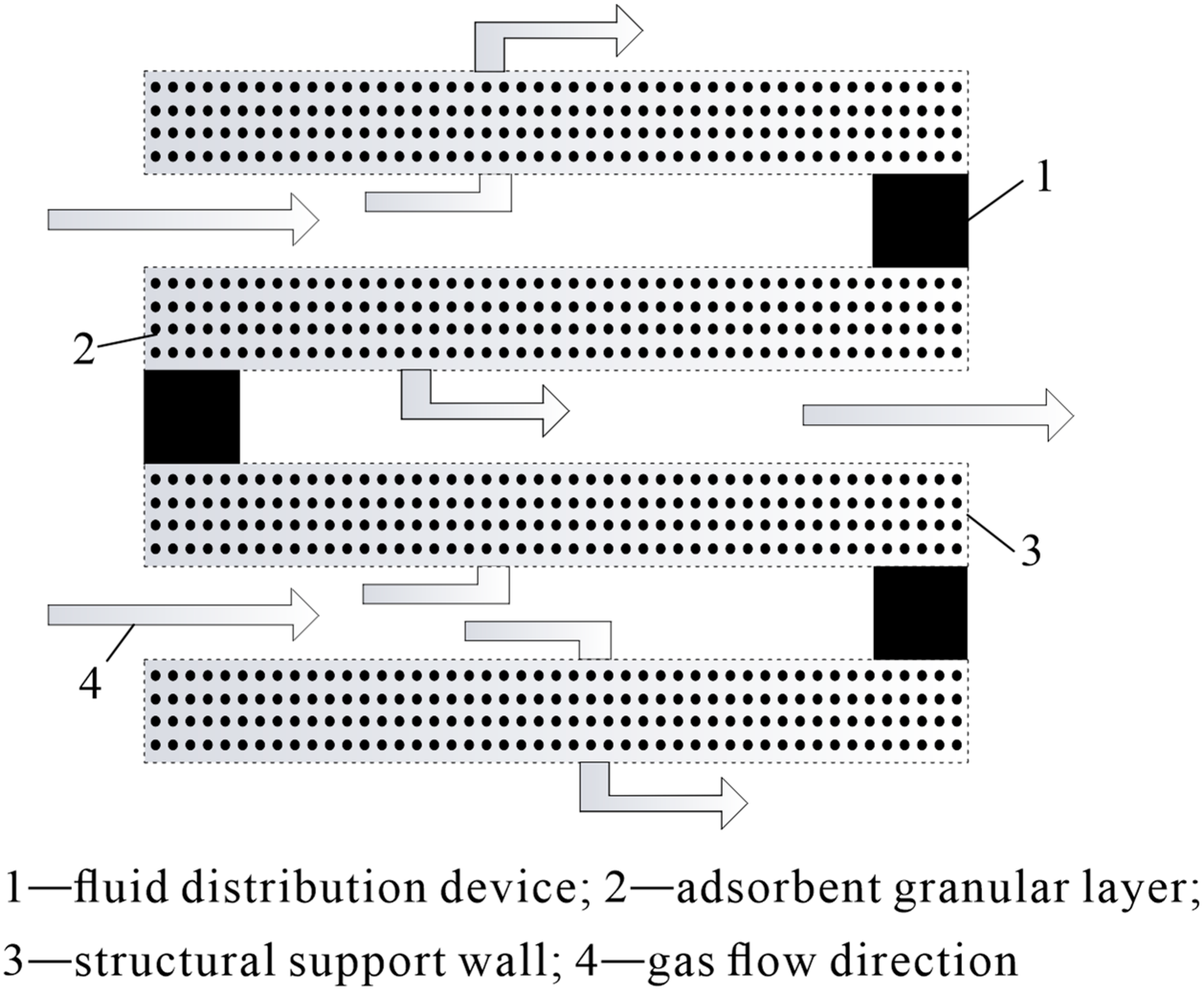

- Gebald, C.; Piatkowski, N.; Ruesch, T.; Wurzbacher, J.A. Low-Pressure Drop Structure of Particle Adsorbent Bed for Adsorption Gas Separation Process (WO 2014/170184 A1); World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gebald, C.; Piaskowski, N.; Luesch, T.; Wurzbacher, J.A. Low-Pressure Drop Structure of a Granular Adsorbent Bed for Gas Separation Process Patent CN105163830B, 9 January 2018.

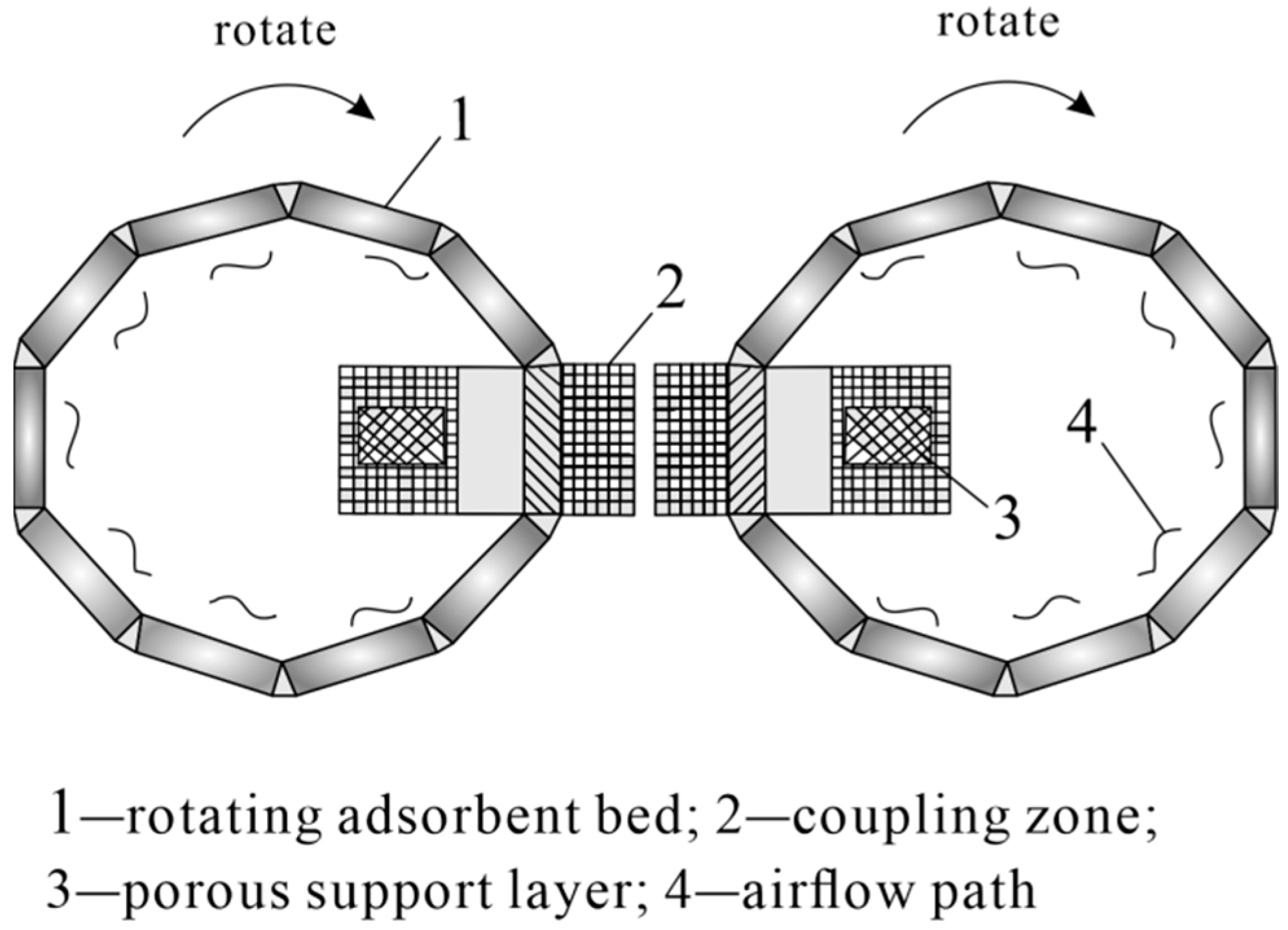

- Eisenberger, P. System for Removing CO2 Rom the Atmosphere Using a Rotating Packed Bed. Patent CN106163636A, 23 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

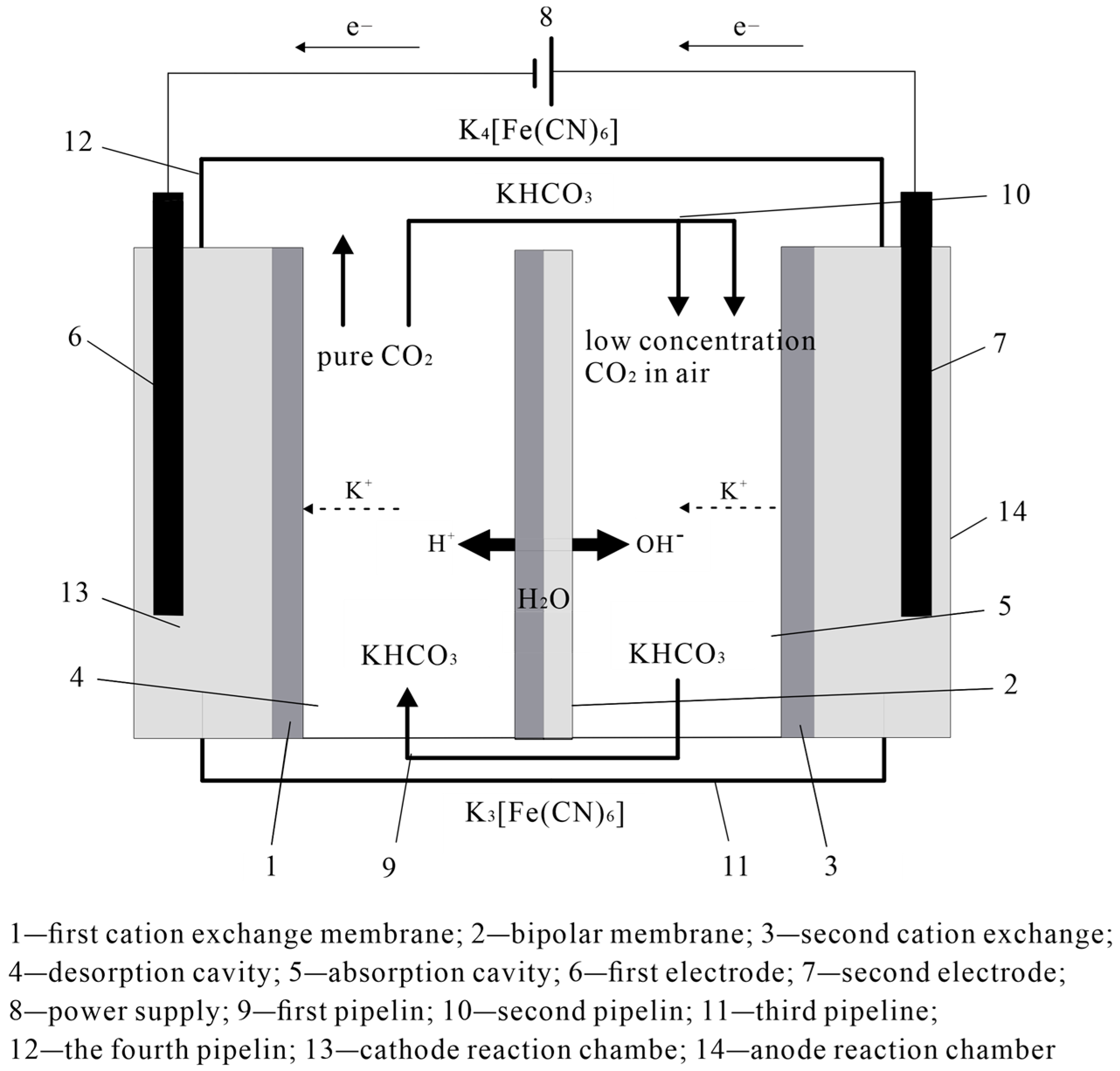

- Deng, S.; Sun, P.; Huang, Y. A Bipolar Membrane Electrodialysis Air Carbon Capture System. Patent CN114307567A, 30 December 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Sun, P.; Huang, Y. Electro-Driven Chemical Carbon Pump Composite Cycle Apparatus and Method for Lean Gas Sources. Patent CN11405231A, 4 February 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Luo, Q.; Cao, Y. Solar-Powered Carbon Dioxide Capture and Recycling System and Method. Patent CN107744722A, 2 March 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Huang, S.; Zhu, J.; Xu, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Q. A Solar-Powered Carbon Dioxide Capture Tower and Method of Operation Thereof. Patent CN111672280A, 20 May 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

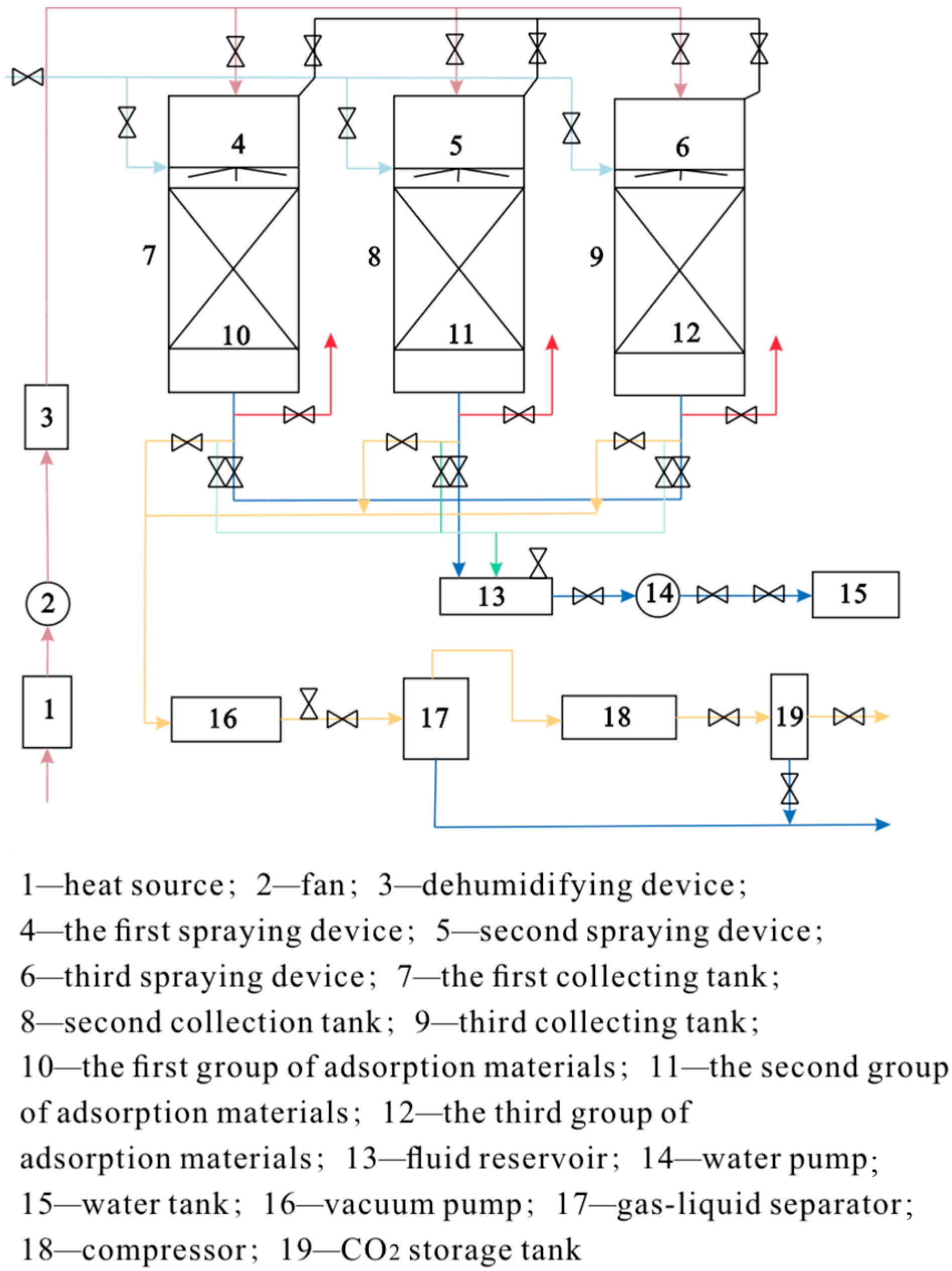

- Li, F.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, P. CO2 Direct Air Capture System and Method Based on Wet-Process Regenerative Adsorption Material. Patent CN114452768A, 3 March 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lei, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, F. A Device and Method for Carbon Dioxide Capture and Purification. Patent CN106552497B, 5 April 2019. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Liu, W.; Xia, Z.; Fang, M. Energy-Saving System and Method for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide with Precise Ion Control. Patent CN114515494A, 20 May 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, F.; Liu, Y. A Device and Method for Directly Capturing Carbon Dioxide from the Air. Patent CN113813746A, 21 December 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Beerling, D.J.; Kantzas, E.P.; Lomas, M.R. Potential for large-scale CO2 removal via enhanced rock weathering with croplands. Nature 2020, 583, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yu, L.; Chong, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, D. A Comprehensive Review on Direct Air Carbon Capture (DAC) Technology by Adsorption: From Fundamentals to Applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322, 119119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, D.G.; Scott, H.S.; Kumar, A.; Zaworotko, M.J. Flue-Gas and Direct-Air Capture of CO2 by Porous Metal-Organic Materials. Philosophical Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20160025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnajjar, H.; Shaker, N.; Naguib, H.; Kandil, U.F.; Ahmed, H.; Farag, A.A. Enhancement of Recycled WPC with Epoxy Nanocomposite Coats. Egypt. J. Chem. 2019, 62, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Q.; Gan, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, G.; Zhao, C. Research Progress on Chemical Absorption Direct Air Capture Technology. Low Carbon Chem. Chem. Eng. 2025, 2, 113–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Lu, B.; Sun, J.; Jiang, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Naguib, H.M.; Hou, G. A Novel Approach to Accelerate the Carbonation of γ-C2S under Atmospheric Pressure: Increasing CO2 Dissolution and Promoting Calcium Ion Leaching via Triethanolamine. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, R.; Gonzalez-Diaz, A.; Rojas-Michaga, M.; Michailos, S.; Pourkashanian, M.; Zhang, X.; Font-Palma, C. Sorption Direct Air Capture with CO2 Utilization. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 95, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Zhang, Z.X.; Yang, X.L. Research Progress on the Coupling Technology of Adsorptive Direct Air Capture and Renewable Energy. Clean Coal Technol. 2025, 31, 33–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.C.; Cui, X.L.; Xing, H. Progress on Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2022, 41, 1152–1162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Low, M.Y.; Barton, L.V.; Pini, R.; Brandani, S. Analytical Review of the Current State of Knowledge of Adsorption Materials and Processes for Direct Air Capture. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 189, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renata, B.; Giuseppe, S.; Marco, M. Process Design and Energy Requirements for the Capture of Carbon Dioxide from Air. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2006, 45, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D. Thermal Economics Study of a NaOH/Ca(OH)2 Dual-Cycle Direct Air Carbon Capture System. Doctoral Dissertation, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Giesen, C.; Meinrenken, C.J.; Kleijn, R. A Life Cycle Assessment Case Study of Coal-Fired Electricity Generation with Humidity Swing Direct Air Capture of CO2 versus MEA-Based Post-Combustion Capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlouw, T.; Treyer, K.; Bauer, C.; Mazzotti, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage with Low-Carbon Energy Sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 11397–11411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.J.; Zhang, K.W.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.Y.; Jin, P.; Liu, Z.Y. Research Progress on Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2024, 43, 2031–2048. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, I.; Wang, R.; Ling-Chin, J.; Roskilly, A.P. Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Integrated Direct Air Carbon Capture: A Techno-Economic Study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 315, 118739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, K.; Ziock, H.J.; Grimes, P. Carbon Dioxide Extraction from Air: Is It An Option? Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL): Los Alamos, NM, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- MacDowell, N.; Florin, N.; Buchard, A.; Hallett, J.; Galindo, A.; Jackson, G.; Adjiman, C.S.; Williams, C.K.; Shah, N.; Fennell, P. An Overview of CO2 Capture Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 7254–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, A.; Tavoni, M. Direct Air Carbon Capture and Sequestration: How It Works and How It Could Contribute to Climate-Change Mitigation. One Earth 2019, 1, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Alherbawi, M.; Okonkwo, E.C.; Al-Ansari, T. Evaluating Negative Emission Technologies in a Circular Carbon Economy: A Holistic Evaluation of Direct Air Capture, Bioenergy Carbon Capture and Storage and Biochar. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 466, 142800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, D.W.; Holmes, G.; St. Angelo, D.; Heidel, K. A Process for Capturing CO2 from the Atmosphere. Joule 2018, 2, 1573–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Song, C.; Miller, B.G.; Scaroni, A.W. Influence of Moisture on CO2 Separation from Gas Mixture by a Nanoporous Adsorbent Based on Polyethylenimine-Modified Molecular Sieve MCM-41. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 8113–8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, H.D.; Moya, C.; Gazzani, M. Direct Air Capture Based on Ionic Liquids: From Molecular Design to Process Assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzig, F.; Breyer, C.; Hilaire, J.; Minx, J.; Peters, G.P.; Socolow, R. The Mutual Dependence of Negative Emission Technologies and Energy Systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridahl, M.; Lehtveer, M. Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS): Global Potential, Investment Preferences, and Deployment Barriers. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 42, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardy, M.; Mac Dowell, N. Can BECCS Deliver Sustainable and Resource Efficient Negative Emissions? Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1389–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, D.W.; Ha-Duong, M.; Stolaroff, J.K. Climate Strategy with CO2 Capture from the Air. Clim. Change 2006, 74, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.R. Pricing CO2 Direct Air Capture. Joule 2019, 3, 1571–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisotti, F.; Hoff, K.A.; Mathisen, A.; Hovland, J. Direct Air Capture (DAC) Deployment: A Review of the Industrial Deployment. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 283, 119416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, M. The Carbon-Sucking Fans of West Texas: It’s Not Enough to Slash Greenhouse Gas Emissions-Experts Say We Need Direct Air Capture. IEEE Spectr. 2021, 58, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppitters, D.; Costa, A.; Chauvy, R. Energy, Exergy, Economic and Environmental (4E) Analysis of Integrated Direct Air Capture and CO2 Methanation under Uncertainty. Fuel 2023, 344, 127969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Direct Air Capture 2022: A Key Technology for Net Zero; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Climeworks AG. Orca Is Climeworks’ Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Removal Plant. Project Webpage, 2021 (Updated 2025). Available online: https://Climeworks.Com/Plant-Orca (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Heirloom Carbon Technologies. Heirloom Unveils America’s First Commercial Direct Air Capture Facility. Company News. 9 November 2023. Available online: https://www.heirloomcarbon.com/news/heirloom-unveils-americas-first-commercial-direct-air-capture-facility (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- World’s First Solar Powered Direct Air Capture Company Launches with First Purchases from Frontier. Company News. 30 June 2022. Available online: https://www.aspiradac.com/dac-company-launches-with-first-purchases-from-frontier (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Technology Centre Mongstad(TCM). Norway Backing Removr’s Efforts to Industrialise Direct Air Capture—Finances Pilot at World-Leading Technology Test Centre. News Release. 28 February 2023. Available online: https://Tcmda.Com/News/Norway-Backing-Removrs-Efforts-to-Industrialise-Direct-Air-Capture-Finances-Pilot-at-World-Leading-Technology-Test-Centre (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Removr. Removr Partners with CO2 Storage Leader Carbfix for Its First Industrial Direct Air Capture Pilot in Iceland. Company News. 16 August 2022. Available online: https://www.removr.com/news/carbfix-partnership (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Trendafilova, P. Global Thermostat Unveils Its Demonstration Direct Air Capture Plant. Carbon Herald. 5 April 2023. Available online: https://carbonherald.com/global-thermostat-unveils-its-demonstration-direct-air-capture-plant/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Cecilia, K. What Will Scale Direct Air Capture? A 75 Percent Price Drop, Report Says. Canary Media. 2023. Available online: https://www.canarymedia.com (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Yafiee, O.A.; Mumtaz, F.; Kumari, P. Direct Air Capture (DAC) vs. Direct Ocean Capture (DOC)—A Perspective on Scale-up Demonstrations and Environmental Relevance to Sustain Decarbonization. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.; Castro-Gomes, J.; Luo, S. The Role of Construction Materials by Accelerated Carbonation in Mitigation of CO2 Considering the Current Climate Status: A Proposal for a New Cement Production Model. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Yan, X.; Zhu, R. A Generative Artificial Intelligence Framework Based on a Molecular Diffusion Model for the Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Carbon Capture. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, A.; Choi, S.; Yu, X.; Brabson, L.M.; Das, A.; Ulissi, Z.; Uyttendaele, M.; Medford, A.J.; Sholl, D.S. The Open DAC 2023 Dataset and Challenges for Sorbent Discovery in Direct Air Capture. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.C.; Kort-Kamp, W.J.M.; Matanovic, I.; Zelenay, P.; Holby, E.F. Design of Amine-Functionalized Materials for Direct Air Capture Using Integrated High-Throughput Calculations and Machine Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.11759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Majumdar, S.; Zhang, X.; Kim, J.; Smit, B. Inverse Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Direct Air Capture of CO2 via Deep Reinforcement Learning. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qu, L.; Ding, H.; Webley, P.; Li, G.K. Distributed Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide by Synergistic Water Harvesting. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, S.; Moosavi, S.M.; Jablonka, K.M.; Ongari, D.; Smit, B. Diversifying Databases of Metal-Organic Frameworks for High-Throughput Computational Screening. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 61004–61014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golze, D.; Hirvensalo, M.; Hernández-León, P.; Aarva, A.; Etula, J.; Susi, T.; Rinke, P.; Laurila, T.; Caro, M.A. Accurate Computational Prediction of Core-Electron Binding Energies in Carbon-Based Materials: A Machine-Learning Model Combining Density-Functional Theory and GW. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 6240–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Huang, T.; Liu, W.; Feng, F.; Japip, S.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S. Design and Prediction of Metal-Organic Framework-Based Mixed Matrix Membranes for CO2 Capture via Machine Learning. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, K.M.; Ai, Q.; Al-Feghali, A.; Badhwar, S.; Bocarsly, J.D.; Bran, A.M.; Bringuier, S.; Brinson, L.C.; Choudhary, K.; Circi, D.; et al. Fourteen Examples of How Large Language Models Can Transform Materials Science and Chemistry: A Reflection on a Large Language Model Hackathon. Digit. Discov. 2023, 2, 1213–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; García-Díez, E.; Garcia, S.; van Der Spek, M. The Impact of Binary Water-CO2 Isotherm Models on the Optimal Performance of Sorbent-based Direct Air Capture Processes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 5377–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- International Energy Agency. Direct Air Capture; IEA: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deutz, S.; Bardow, A. Life-Cycle Assessment of an Industrial Direct Air Capture Process Based on Temperature-Vacuum Swing Adsorption. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.M.; Sandhu, N.K.; McCoy, S.T.; Bergerson, J.A. A Life Cycle Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Direct Air Capture and Fischer-Tropsch Fuel Production. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 3129–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realmonte, G.; Drouet, L.; Gambhir, A.; Glynn, J.; Hawkes, A.; Köberle, A.C.; Tavoni, M. An Inter-Model Assessment of the Role of Direct Air Capture in Deep Mitigation Pathways. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhrman, J.; McJeon, H.; Patel, P.; Doney, S.C.; Shobe, W.M.; Clarens, A.F. Food-Energy-Water Implications of Negative Emissions Technologies in a +1.5 °C Future. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy Innovation: An Introduction to the Concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Congress. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022; Public Law; U.S. Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 117–169. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Union Certification Framework for Carbon Removals; COM(2022) 672 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Direct Air Capture; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

| Methods of Carbon Dioxide Separation | Solid Adsorbent | Liquid Adsorbent |

|---|---|---|

| Energy consumption per unit (GJ/tCO2) | 7.2–9.5 | 5.5–8.8 |

| Proportion of thermal energy consumption (%) | 75–80 | 80–100 |

| Energy consumption per unit (GJ/tCO2) | 7.2–9.5 | 5.5–8.8 |

| Proportion of electricity consumption (%) | 20–25 | 0–20 |

| Regeneration temperature | 80–100 °C | 900 °C |

| Land requirements (km2/MtCO2) | 1.2–1.7 | 0.4 |

| Life-cycle emissions (tCO2 emitted/tCO2 captured) | 0.03–0.91 | 0.1–0.4 |

| Scenario | Energy Source | Scale Assumption | Regional Factors | Indicative Cost (USD/t CO2) | Energy Intensity | Key Risks and Uncertainties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1-Current Baseline DAC | Grid electricity and fossil-based heat; limited access to renewables | Small to medium-scale plants (≈104–105 t CO2/yr) | Fossil-dominated power systems; immature supply chains | 300–600 (sometimes up to 1000 USD/t CO2) | 1500–2500 kWh/t CO2 (≈8–10 GJ/t) | High CAPEX and OPEX; high electricity prices; limited operational experience; low technology maturity |

| S2-Near-term Optimized DAC | Mixed energy (part renewables, part fossil); partial use of waste heat | Medium to large-scale (≈105–106 t CO2/yr) | Emerging renewable regions (Europe, North America, China) | 230–400 | 1200–1800 kWh/t CO2 (≈6–9 GJ/t) | Uncertain pace of cost reduction; limited low-carbon energy supply; evolving policy support |

| S3-Large-scale Low-carbon DAC | Predominantly renewable or nuclear electricity + low-carbon heat (solar/geothermal) | Large commercial plants or clusters (≈106–107 t CO2/yr) | Regions with abundant low-cost renewables and CO2 storage sites (e.g., North Sea, Australia, Middle East) | 200–300 | 800–1500 kWh/t CO2 | Large upfront capital investment; CO2 transport and storage infrastructure; regional siting and permitting constraints |

| S4-Optimistic Future DAC | Fully decarbonized energy systems; integration of waste heat and advanced regeneration | Gigaton-scale deployment (>106 t CO2/yr per cluster); modular mass manufacturing | Regions with strong policy incentives, abundant renewables, and CO2 storage (e.g., U.S., Gulf States, Australia) | 230–540 (policy targets < 100 USD/t CO2 are unlikely near term) | <800–1000 kWh/t CO2 (best-case projections) | Dependence on rapid innovation and subsidies; resource competition (materials, land, water); uncertain long-term policy stability |

| Affiliated Factory | State | Carbon Dioxide Capture Volume t·yr−1 |

|---|---|---|

| Global Thermostat | United States | 500 |

| Global Thermostat | United States | 1000 |

| Global Thermostat | Canada | 365 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 1 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 50 |

| Climeworks | Switzerland | 900 |

| Climeworks | Iceland | 50 |

| Climeworks | Switzerland | 600 |

| Climeworks | Switzerland | 3 |

| Climeworks | Italy | 150 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 3 |

| Climeworks | Netherlands | 3 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 3 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 50 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 50 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 3 |

| Climeworks | Germany | 3 |

| Climeworks | Iceland | 4000 |

| Ordos Test Site | China | Thousand-tonne class |

| MissionZeroTechnologies | United Kingdom | Thousand-tonne class |

| INPEX Hokkaido pilot scheme | Japan | Hundred-tonne class |

| Heirloom Carbon Technologies | United States | 1000 |

| Climeworks | Iceland | 36,000 |

| Removr-Carbfix DAC pilot | Iceland | 300 |

| Removr-industrial pilot at Technology Centre Mongstad (TCM) | Norway | 300 |

| Mission Zero Technologies | United Kingdom | 50 |

| CarbonCapture Inc. -Leo-series DAC module | United States | 500–700 |

| AspiraDAC-pilot DACCUS facility | Australia | ≈365 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, J.; Xu, H. Research on Direct Air Capture: A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 6632. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246632

Zhao Y, Zheng B, Zhang J, Xu H. Research on Direct Air Capture: A Review. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6632. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246632

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yiqing, Bowen Zheng, Jin Zhang, and Hongyang Xu. 2025. "Research on Direct Air Capture: A Review" Energies 18, no. 24: 6632. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246632

APA StyleZhao, Y., Zheng, B., Zhang, J., & Xu, H. (2025). Research on Direct Air Capture: A Review. Energies, 18(24), 6632. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246632