1. Introduction

Rural Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is home to over 700 million people, many of whom live in dispersed settlements connected mainly by secondary or tertiary roads [

1]. While roughly 700,000 km of rural tracks span the region, many communities remain isolated due to transport options being limited and unreliable [

2]. Mobility in these areas is often restricted to walking or informal travel, which severely constrains access [

3].

Rural mobility in SSA supports domestic, agricultural, and service-related activities [

4]. Without dependable transport services, households face heavy time burdens that limit productivity and reinforce poverty. Vehicle use in these regions is restricted by poor road infrastructure; high operating costs; and small, poorly maintained fleets often restricted to main roads [

5]. Intermediate means of transport (IMTs), such as bicycles, animal-drawn carts, and motorcycles, are suitable for trips of up to roughly 40 km but cannot handle longer distances or heavier loads [

6]. Larger vehicles could accommodate these needs but are costly and rarely reach rural settlements.

Light delivery vehicles (LDVs) bridge this gap by carrying heavier loads and providing more flexible access between villages and markets. However, conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles face several challenges in rural SSA. Required maintenance is frequent and costly, while refueling and fluctuating fuel prices further increase operating costs [

7]. Additionally, inefficient and poorly maintained engines contribute significantly to air pollution and carbon emissions, with transport responsible for roughly 10% of total national emissions in major African economies [

8].

Electric vehicles (EVs) offer an attractive alternative to conventional ICE vehicles. These types of vehicles reduce emissions and lowers energy and maintenance costs. However, commercial EVs are often designed for urban markets and include features that increase costs and offer little benefit in rural SSA contexts.

Converting ICE vehicles to EVs provides a practical route to reducing initial investment and extending vehicle lifespan [

9]. It also allows vehicles to be adapted to local conditions, such as rough terrain and limited charging options. By using existing assets, EV conversions support a circular economy that reduces waste, extends vehicle life, and optimises resource use through component selection and local repairability. They also align with sustainable mobility principles by promoting energy-efficient, low-emission transport that improves accessibility, affordability, and operational reliability for rural communities. Beyond these technical and environmental benefits, the conversion process can spur job growth in areas such as local manufacturing, EV conversion workshops, and infrastructure development, helping rural communities participate in the growing global EV market.

The design of EV conversions that perform reliably in rural SSA requires system-level tools to model vehicle performance under local conditions and evaluate design trade-offs. These tools should simulate different configurations across varying road conditions, duty cycles, and payloads to identify well-adapted solutions. Evaluating multiple options before investing resources reduces financial risk. Furthermore, it can guide local workshops and technicians in understanding system interactions that build skills for vehicle maintenance and adaptation.

EV conversion design and performance modelling have been widely studied in literature.

Table 1 summarises key studies and highlights their main contributions. Some studies focus mainly on component selection [

10,

11] or design optimisation [

12,

13], while others emphasise simulations to evaluate performance in terms of energy use, range, or emissions [

14,

15]. However, most existing work is centred around passenger vehicles in urban settings, making them less applicable for rural SSA. Urban studies typically assume established road networks, consistent travel patterns, and accessible charging, whereas rural SSA comprises dispersed villages, poor road conditions, and limited charging access. These differences necessitate dedicated modelling approaches tailored to rural applications.

Very few studies specifically address SSA. For instance, one study investigates converting minibus taxis using drive-cycle data to electrify vehicles for urban passenger transport [

16]. While it demonstrates the feasibility of conversion design, it focusses on urban settings and passenger transport rather than rural delivery or utility applications. Another study presents a ground-up EV design for various applications in SSA [

17]. Although relevant, it does not consider the conversion of existing vehicles, and it does not present a simulation framework to evaluate vehicle performance under realistic rural conditions.

This highlights a clear research gap: few studies investigate EV conversion design and performance evaluation specifically adapted for LDVs in rural SSA, where vehicles must operate reliably over rough terrain and cover long distances between settlements with limited infrastructure. To address this gap, the objectives of this study are to (1) review and compare EV technologies and powertrain configurations to identify a suitable option for LDV conversions in rural SSA; (2) develop a systematic, context-specific methodology for component selection that balances performance, cost, and reliability; and (3) create a simulation-based framework to evaluate and validate vehicle performance under representative rural SSA conditions.

The methodology is demonstrated on the Suzuki Super Carry, a vehicle chosen for its affordability, availability, and suitability for light-duty applications in SSA. While this work is presented on this vehicle, the methodology can be adapted to other conversion projects. The workflow provides a practical tool to guide component selection, model full-vehicle performance, and evaluate energy consumption under representative rural conditions. It demonstrates the feasibility of EV conversions as a sustainable alternative to ICE vehicles while supporting local skill development and promoting broader EV adoption in developing regions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews EV types and powertrain configurations relevant to EV conversions.

Section 3 presents a systematic approach for selecting drivetrain, motor, and battery components. Intermediate calculations and analyses are included here to demonstrate the logical steps in the component selection methodology.

Section 4 describes the simulation framework used to evaluate vehicle performance under representative rural SSA conditions.

Section 5 presents the outputs of the completed simulation, including requirement validation, comparison with commercial alternatives, sensitivity analysis, and scenario-based evaluation.

Section 6 summarises key findings and discusses implications for EV conversions in rural SSA.

2. An Overview of EV Technology

This section provides background on EV technology to support the design and simulation of LDV conversions for rural SSA. An overview of EV types is presented, along with a rationale for selecting the most appropriate type, which guides component selection. A typical battery electric vehicle (BEV) architecture is described, highlighting major components and their inter-relationships for effective simulation. Additionally, four common powertrain configurations are presented, which will later be compared to identify the most suitable option.

2.1. Electric Vehicle Types

EVs can be classified into two main types: those powered only by batteries and those that combine a battery with a separate energy source, such as an ICE or a fuel cell. Each type has distinct advantages and disadvantages, making them suitable for different use cases. The main EV types are listed in

Table 2.

The choice of EV type depends on various operational requirements. Some key considerations for this study include conversion complexity, refuelling or recharging infrastructure availability, environmental impact, and cost. For this study, a BEV is selected due to the following benefits:

Powertrain simplification – Removing the ICE components and avoiding hybridisation simplifies mechanical integration, reduces maintenance needs and minimises control logic complexity.

Lower operational cost – Studies show that BEVs have lower operational costs (recharging, maintenance, etc.) than other EV types, which is critical in cost-sensitive rural applications [

19].

Environmental benefit – BEVs do not combust fossil fuels and therefore produce no tailpipe emissions, aligning with the emissions reduction goal of this study.

2.2. Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) Overview

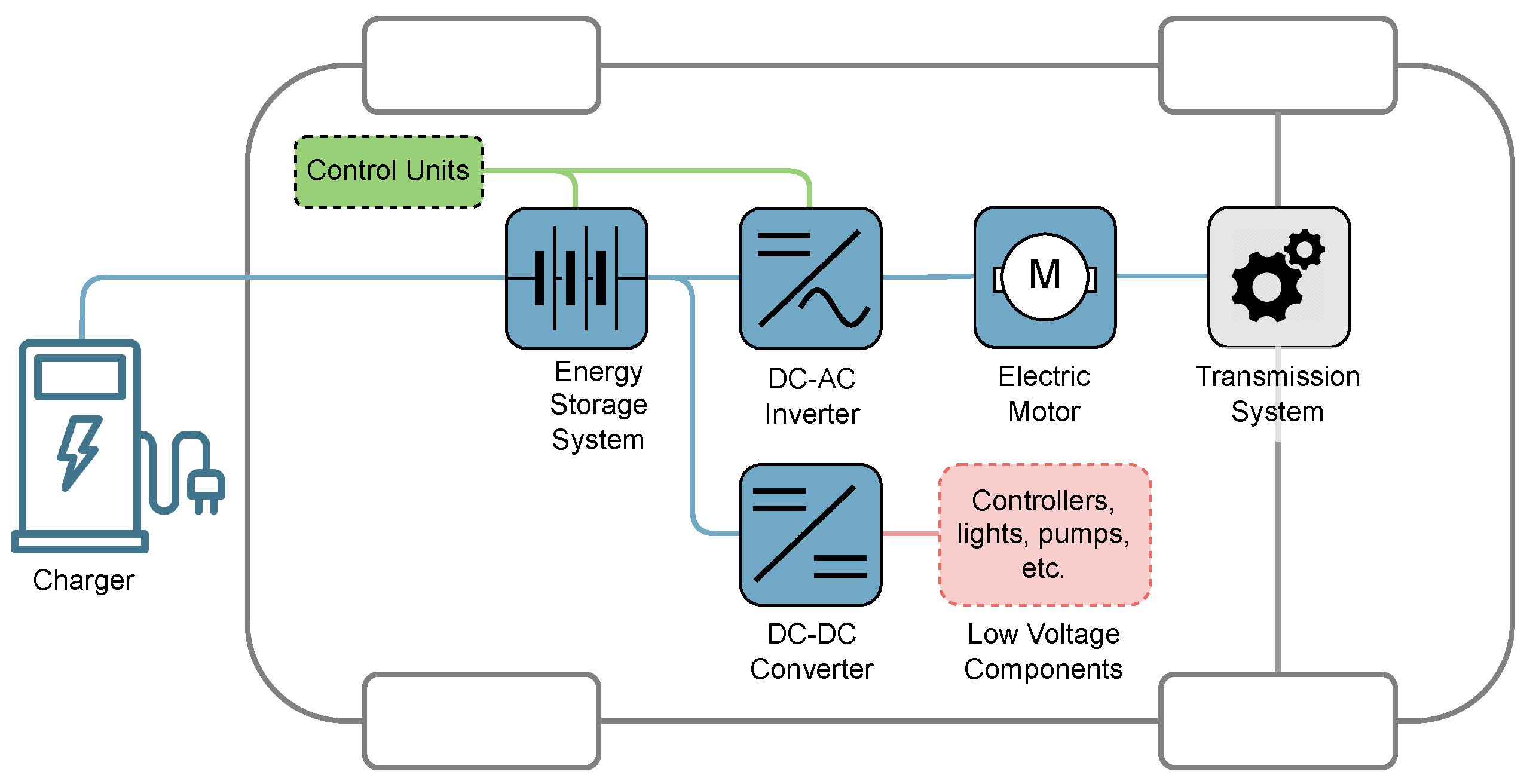

The core architecture of a battery electric vehicle consists of an energy storage system (ESS) that supplies power to the electrical drive system. This drive system typically includes an inverter, an electric motor, and a drivetrain (comprising a transmission unit, differential, and axles) to deliver mechanical energy to the wheels for propulsion [

20].

Figure 1 illustrates a system-level overview of a typical BEV.

The energy storage system, usually a high-voltage (HV) lithium-ion battery pack [

21], stores electrical energy and supplies direct current (DC) power to the rest of the vehicle. Its capacity predominantly determines vehicle range. In the drive system, DC power is first routed through the inverter to convert it into alternating current (AC) required for the motor, which also controls the motor torque and speed [

22]. The rotational torque generated by the motor is transmitted to the vehicle’s wheels via the drivetrain. In most BEVs, the drivetrain is simplified to a single-speed transmission connected to a differential and axles [

23].

The DC–DC converter steps the HV battery output down to a lower voltage, typically 12 to 48 volts, to power auxiliary systems such as lighting, climate control, and other electronics. Some BEVs include a thermal management system to cool the battery and power electronics, ensuring safe and efficient operation.

Charging of the ESS may occur through either AC or DC input. In AC charging, an on-board charger is used to convert AC supplied from the grid to DC for the ESS. Alternatively, DC charging supplies power directly to the battery for faster energy transfer. However, this requires an external charging station capable of delivering regulated high-voltage DC power and is typically more expensive.

When designing a BEV conversion, all of these components and subsystems must be carefully considered to ensure compatibility, efficiency, and safety. Conversions are constrained by the original ICE vehicle’s physical layout, weight distribution, and mechanical interfaces, so careful planning of component placement and integration is critical.

2.3. Powertrain Configurations

The powertrain of a BEV includes all components involved in generating and delivering power to the wheels for vehicle propulsion, typically including the high-voltage battery, inverter, electric motor, transmission, and differential. Various powertrain configurations exist and should be selected based on the specific conversion application requirements, such as packaging constraints, conversion effort, cost, and efficiency targets.

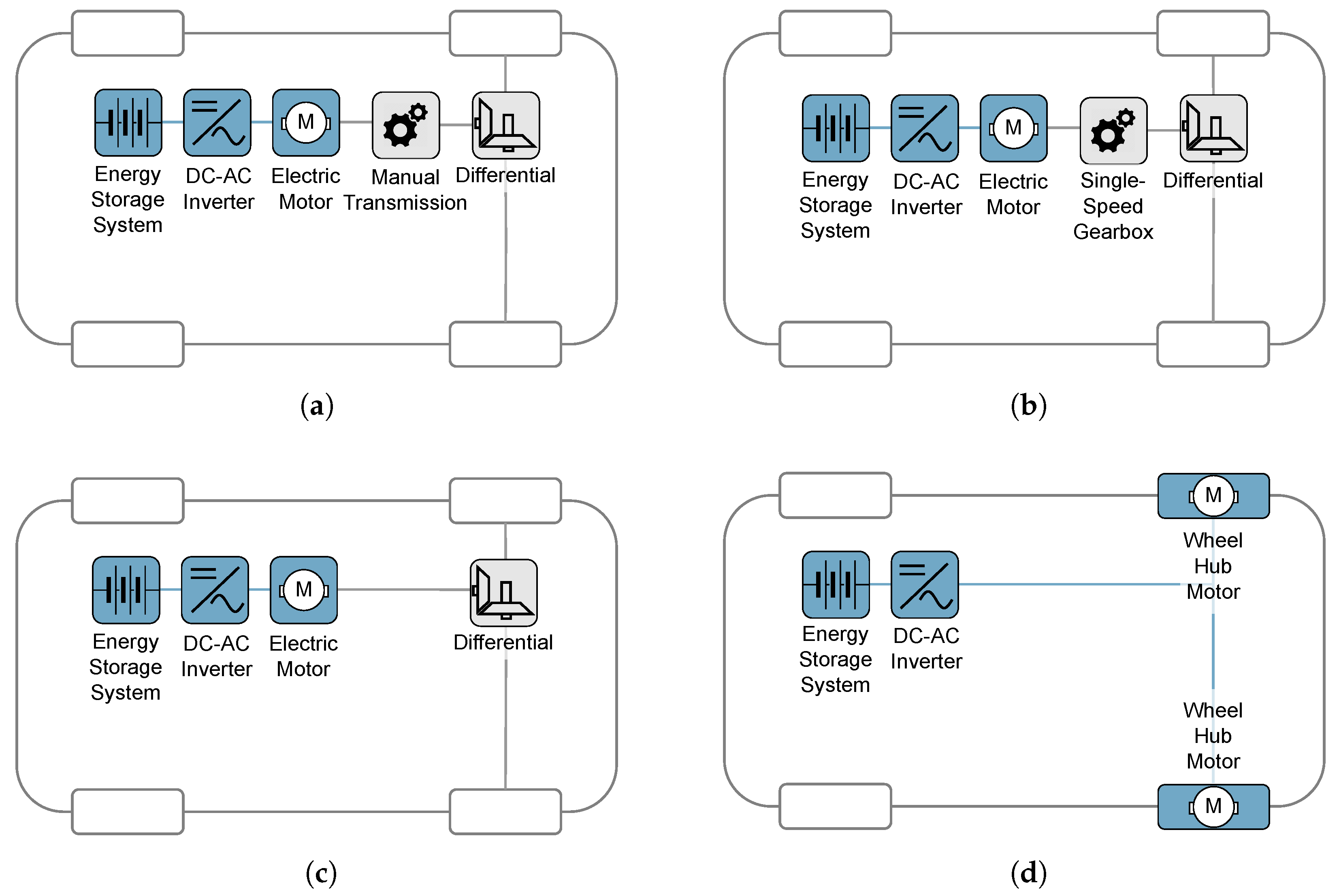

Figure 2 illustrates four common powertrain configurations for a converted rear-wheel-drive BEV.

Figure 2a represents a configuration in which the ICE is replaced by an electric motor, while the original manual transmission (MT) and differential are retained. This approach minimises conversion effort, but the added weight of the transmission and the inefficiencies associated with gear shifting can lead to increased energy consumption.

Figure 2b shows a single-speed reduction gearbox instead of the manual transmission, reducing driveline losses and driver interaction. In

Figure 2c, the motor is directly coupled to the differential through a propeller shaft. This layout further improves efficiency by eliminating the intermediate gearbox. However, achieving the desired torque-speed characteristic may require differential modifications, which can increase cost.

Figure 2d shows each rear wheel being driven independently by its own motor, removing the need for any gearbox or differential. This is a simple and efficient solution, but wheel-hub motors (WHMs) are generally expensive and could present long-term reliability challenges due to vibrations [

24].

3. Powertrain Design and Selection

This section outlines the methodology for selecting the components of a battery electric vehicle conversion for light commercial applications in rural SSA. The approach begins with an analysis of performance requirements using a representative drive cycle. These requirements guide the selection of the electric motor, inverter, drivetrain, and battery system.

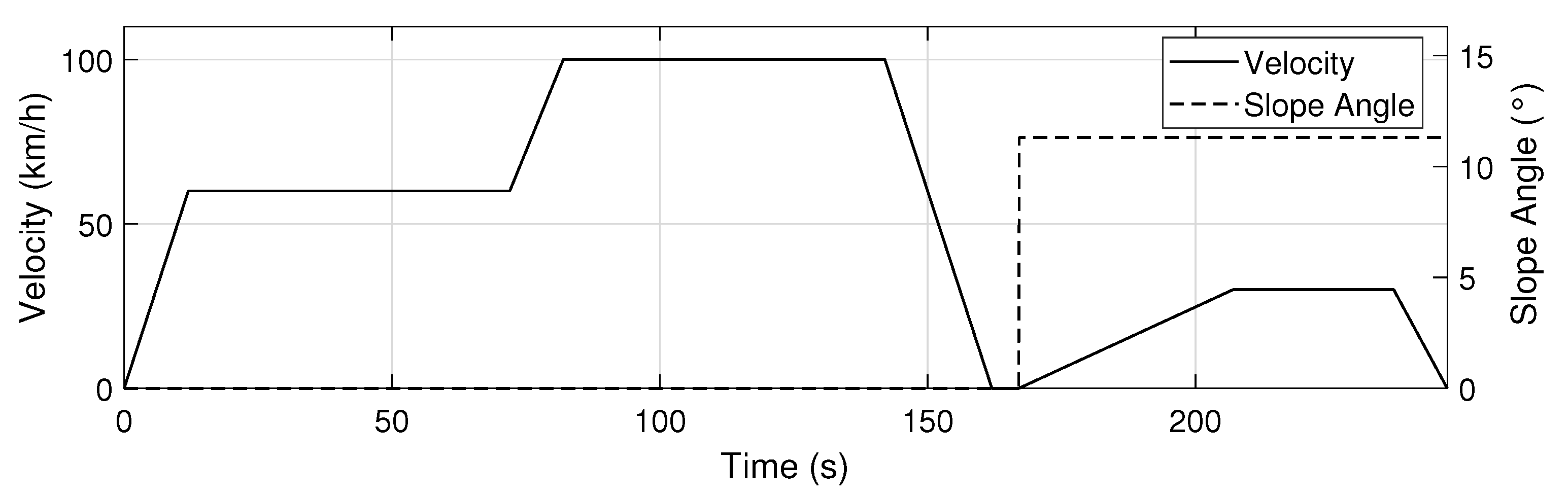

3.1. Drive-Cycle Requirement

To size and select the electric drive and energy storage systems, a representative drive cycle must be established that captures the demands of typical driving. The BEV is designed to closely match the driving characteristics of the original Suzuki Super Carry to preserve the vehicle’s intended usability and load-carrying performance without over-sizing components. Where specific data was unavailable, requirements were derived from similarly classed vehicles and conservatively adjusted to ensure realistic performance targets. The dynamic performance requirements are summarised in

Table 3 and form the basis of a generalised drive cycle used for the analysis of performance requirements.

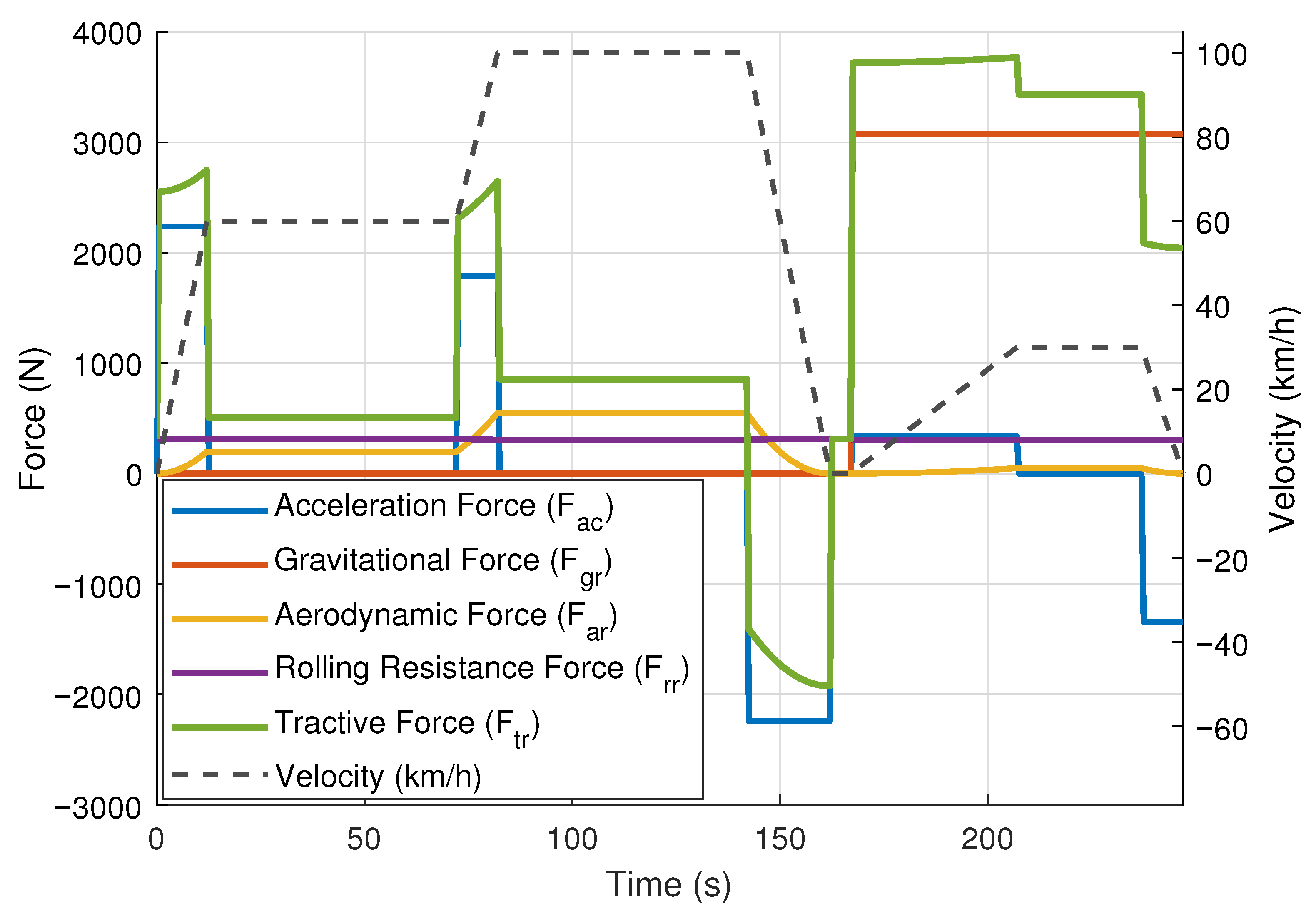

Figure 3 shows the resulting drive cycle.

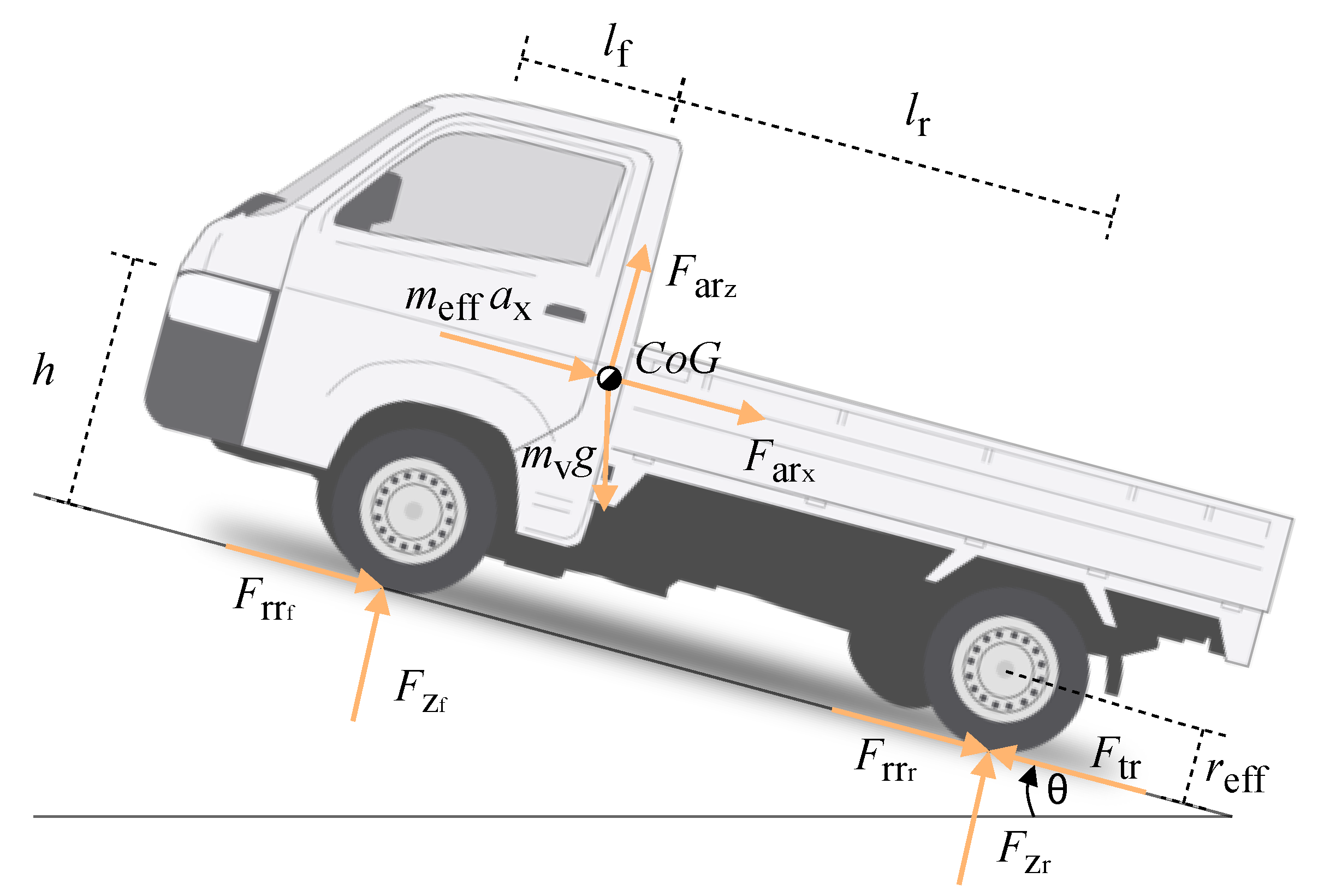

3.2. Dynamic Vehicle Model

To determine the peak power, torque, and speed required at the wheels of the vehicle for the defined drive cycle, a model for the longitudinal dynamics of the vehicle is developed. This model estimates the total tractive force required at the wheels by accounting for key external forces, such as rolling resistance, aerodynamic resistance, gravitational forces on inclines, and inertial forces during acceleration. The vehicle is assumed to have a symmetrical weight distribution about the longitudinal axis, enabling the use of a simplified half-vehicle model. To reflect the Suzuki Super Carry’s rear-wheel-drive layout, the tractive force is assumed to act on the rear wheels. The analysis assumes that motion occurs in a straight line, excluding lateral forces to focus on primary propulsion and braking dynamics. A free-body diagram of the longitudinal forces acting on the vehicle is illustrated in

Figure 4.

To calculate the tractive force at the rear wheels needed for each segment of the drive cycle, the net longitudinal force balance is expressed using Newton’s second law:

where

represents the net tractive force for a rear-wheel-drive vehicle (positive for propulsion and negative for braking);

and

are the front and rear rolling resistance forces;

is aerodynamic drag;

is the vehicle’s mass; and

is the effective mass of the vehicle, which includes the rotational inertia of the wheels and axles. For a vehicle with rotational components of inertia (

) and an effective wheel radius of

, the effective mass can be expressed as

The gravitational force is captured by

. The rolling resistance forces are modelled as

where

is the rolling resistance coefficient (RRC) and

is the normal force on the front (

) or rear (

) wheels. During acceleration and braking, weight shifts between the axles, affecting the normal forces and, therefore, the rolling resistance forces. To determine

, moments are taken about the front and rear tire–road contact points and can be expressed as

where

and

are the distances from the vehicle’s centre of gravity to the front and rear axles, respectively;

h is the height of the centre of gravity above the ground;

is the distance to the opposite axle (

for

and

for

); and

is a sign factor (

for front and

for rear).

The aerodynamic resistance forces are given by

where

is the air density,

is the vehicle’s frontal area,

is the longitudinal velocity, and

is the aerodynamic coefficient for direction

k (

for drag and

for lift).

Once the tractive force is known, the required power, torque, and speed at the motor can be calculated using the effective wheel radius (

), drivetrain gear ratio (

), and drivetrain efficiency (

), expressed as follows:

These parameters define the motor’s ability to meet the vehicle’s dynamic performance requirements.

The overall drivetrain efficiency is determined by the combined losses of all mechanical components between the motor and the wheels, such as the gearbox and differential. It is expressed as the product of the individual component efficiencies:

3.3. Vehicle Force Analysis

Before selecting the components of the powertrain, the dynamic model is used to simulate the vehicle’s response to the drive cycle, quantifying the effect of external forces and the resulting required power, torque, and speed at the wheels. The model and drive cycle are implemented in MATLAB (2024b) and Simulink to generate time-series data.

Table 4 lists the parameters of the vehicle used in the simulation.

Figure 5 illustrates the key forces acting on the vehicle over the drive cycle. In the 0–60 km/h acceleration segment, the acceleration force is the main contributor, accounting for approximately 85% of the total tractive force. During constant-velocity driving, the rolling resistance and aerodynamic drag are the primary resistances. On the incline segment, the gravitational force is the dominant factor, substantially increasing the total tractive force demand on the motor.

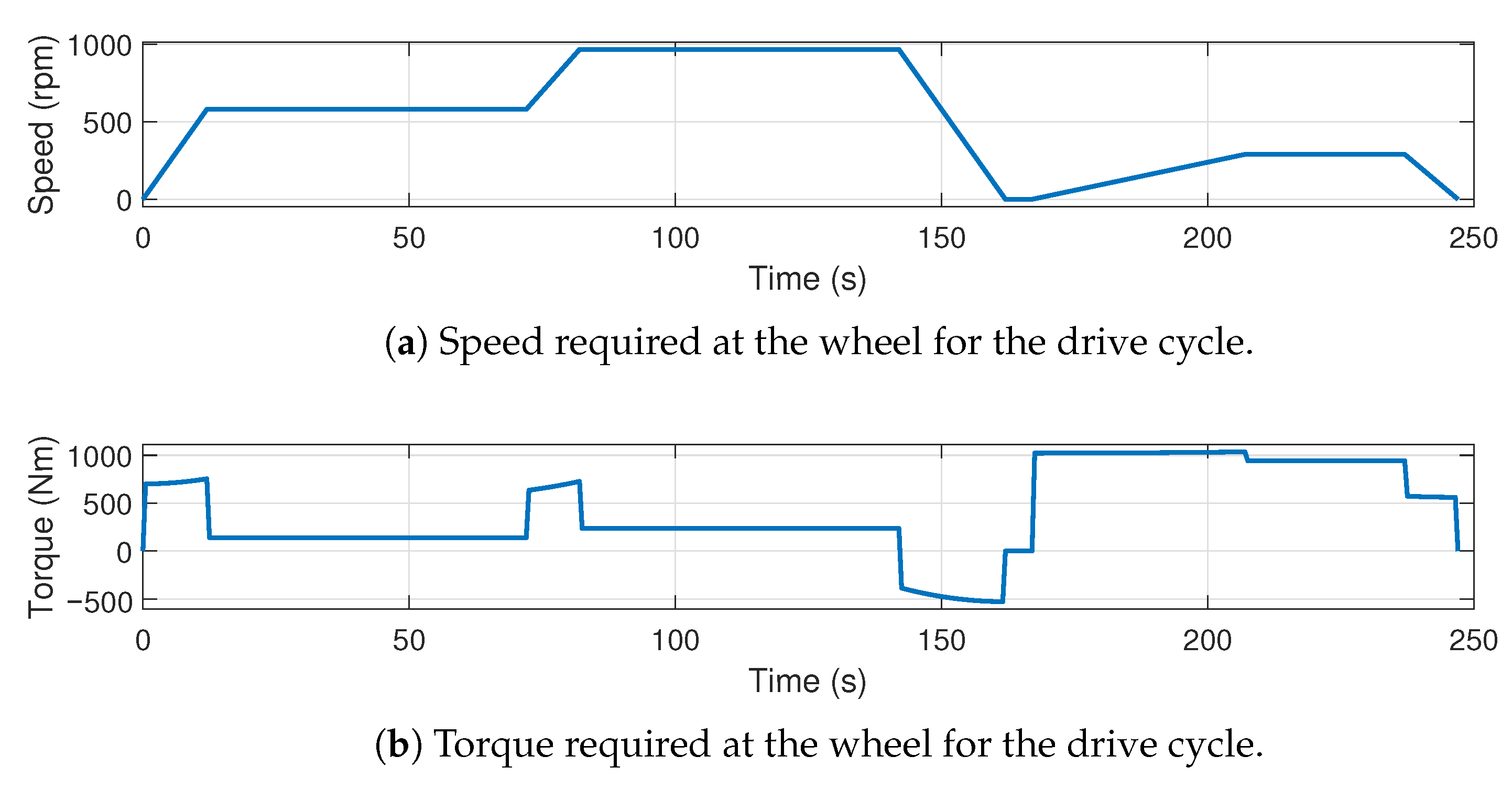

The corresponding speed, torque, and power demands at the wheels are illustrated in

Figure 6.

The plots show that a maximum torque of approximately 1036 Nm occurs during acceleration on an incline, while a maximum power of approximately 73 kW is reached during high-speed acceleration when both torque and speed are high.

In the following sections, the drivetrain will be parametrised, and these simulations will be used to derive the electric motor’s performance requirements.

3.4. Drivetrain Options and Performance Implications

The drivetrain configuration directly affects the electric motor’s performance requirements, as well as the overall conversion complexity, cost, and reliability. This section compares the drivetrain layouts introduced in

Section 2.3 and evaluates their influence on motor sizing and suitability for rural SSA.

In this study, drivetrain efficiency is defined as the combined efficiency of the primary mechanical components, including the gearbox (where applicable) and the differential. Minor losses from secondary components, such as propeller shafts, universal joints, and bearings, are excluded, as the purpose of this analysis is to determine high-level motor performance requirements. These secondary losses are typically small relative to primary drivetrain losses and do not influence motor sizing at this stage of the design process.

3.4.1. Manual Transmission

Retaining the existing manual transmission is an attractive option for conversion applications, as it minimises mechanical modifications and allows for reuse of existing components. The overall MT efficiency is influenced by several factors, such as gearing losses, bearing losses, and sealing losses [

23]. Literature from Machado et al. [

27] defines an average efficiency range of 92% <

< 97% for a manual transmission. For this study, the lower boundary of 92% is used to account for wear in older vehicles. In this configuration, differential efficiency is assumed to be 96% (detailed in

Section 3.4.3), giving a total efficiency of 88%.

The gear selection strategy is simplified to align with the drive-cycle segments. The gear for each segment is chosen to minimise performance requirements of the motor. Second gear is used throughout flat-road acceleration and highway cruising, while first gear is applied for the start of the steep hill to ensure sufficient torque. The chosen gears and their justifications are summarised in

Table 5. While this does not represent a complete shifting strategy, the simplified approach is sufficient for defining motor requirements in this study.

Regenerative braking in an MT configuration can be limited by the selected gear. During a braking event, the gear position is usually kept constant to ensure safety, but the motor may reach its torque limit before the required braking demand is met, reducing energy recuperation [

28].

3.4.2. Single-Speed Gearbox

The gear ratio of the single-speed gearbox (SSG) is selected to meet torque and speed requirements for acceleration, gradability, and maximum vehicle speed. At this stage of the design process, only the requirements at the wheel are defined; therefore, the SSG ratio is selected to establish a baseline for determining motor torque and speed capabilities. For this analysis, the specifications of the EV-TorqueBox are used [

29], including helical planetary gears and a reduction ratio of 1.9:1. It achieves an efficiency of 95%, resulting in a total drivetrain efficiency of approximately 91% when combined with the differential. This ratio may be revisited during motor selection to ensure alignment with vehicle requirements.

Regenerative braking is simpler with a fixed ratio compared to the MT configuration, but its effectiveness is dependant on optimal motor sizing.

3.4.3. Direct Differential Coupling

A typical differential consists of two sets of bevel gears, where one set transmits power from the propeller shaft to a crown bearing, determining the final ratio, while the other set transmits power from the crown bearing to the individual wheel axes. A study by Tan et al. [

30] shows that a maximum efficiency of 98.2% can be achieved for such gears. For this analysis, the combined efficiency of the two bevel gear sets is assumed to be 96%.

For the direct differential coupling (DDC) configuration, only the final drive ratio is available to influence wheel torque and speed. The ratio is increased from its original 3.7:1 to 6.1:1 to reduce the torque demand on the motor. This ratio is a reasonable initial design point based on typical differential options available in the local market at the time of this study. As with the SSG configuration, this ratio may be refined once the motor options are evaluated.

3.4.4. Wheel-Hub Motors

The WHM configuration eliminates the need for a gearbox or differential, improving overall powertrain efficiency and freeing space within the vehicle chassis [

24]. Despite these advantages, WHMs are not widely adopted due to challenges including braking integration, thermal management, and high torque demands.

With no intermediate transmission, the WHM’s power, torque, and speed requirements are similar to those experienced at the wheels. As a result, gear ratio and drivetrain efficiency are not considered in this analysis.

3.4.5. Drivetrain Performance Analysis

The overall drivetrain gear ratio and efficiency of each configuration used in Equations (6)–(8) are listed in

Table 6. These values are used to configure the simulation model to determine the motor’s performance requirements.

Figure 7 illustrates the performance results for each drivetrain configuration over the drive cycle. The MT configuration achieves the highest vehicle speeds but demands the lowest torque at the motor; however, this outcome is sensitive to the gear-shifting strategy. The SSG and DDC configurations show similar performance demands due to their closely matched gear ratios, though the DDC configuration benefits from reduced power losses due to its single-gearbox design. The WHM configuration requires substantially higher torque from the motor while operating at lower overall speeds. It should be noted that in the WHM configuration, a motor is mounted at each rear wheel; therefore, the torque and power shown in the plots are shared between the two motors.

These results illustrate how the drivetrain architecture directly influences motor performance requirements. In the following section, the peak and continuous demands extracted from these results are used to select an appropriate motor based on the torque-speed and power-speed characteristics.

3.5. Electric Motor Technologies and Selection

3.5.1. Electric Motor Technologies

Electric vehicles use several types of electric motors depending on the application, ranging from small electric carts to full-size vehicles. The most commonly used machines are DC motors, permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs), induction motors (IMs), and switched reluctance motors (SRMs). Each motor type exhibits distinct characteristics that influence its suitability for a given application. Some of the main characteristics are power density, efficiency over the operational speed range, affordability, reliability, technical maturity, and controllability [

31,

32].

Table 7 provides a comparative summary of these motor types.

For this study, a PMSM is selected based on its high power density and exceptional efficiency. Due to the limited space in a converted vehicle, a compact motor is required that can deliver sufficient torque at lower volume and weight. Additionally, the high efficiency of a PMSM makes it suitable for longer driving ranges, which is particularly advantageous for rural delivery applications with extended routes and limited charging infrastructure.

3.5.2. Electric Motor Performance Requirements

An appropriate PMSM is selected for each drivetrain configuration based on the performance requirements from

Section 3.4.5. Electric motors have peak and continuous ratings. Peak power and torque are the maximum outputs sustainable for short periods (e.g., 30 s) before overheating occurs, typically used during events like acceleration. Continuous power and torque are operating levels that the motor can maintain for longer periods without thermal overload and are based here on the cruising segment at 100 km/h. The motor must meet both to ensure adequate performance.

Table 8 lists the selected motor options used to benchmark the drivetrain configurations. Although the final motor choice depends on availability, these models provide a realistic basis for comparing layouts.

Figure 8 presents the characteristic curves for the selected motor options. The plots mark the peak and continuous operating points to illustrate that each motor meets the performance requirement for its drivetrain configuration.

3.5.3. Electric Motor and Drivetrain Selection

We compare the motor and drivetrain configurations based on several characteristics, namely weight, conversion simplicity, affordability, energy efficiency, reliability, and maintenance. Retaining the MT allows for the use of a smaller motor, reducing cost and simplifying the conversion, since most of the existing drivetrain is kept but with reduced energy efficiency and higher maintenance demands due to clutch and gearbox wear. In contrast, both the SSG and DDC configurations require additional mechanical modifications, which could increase cost. The SSG improves energy efficiency and reliability by eliminating gear shifting, but this comes at the cost of a higher conversion complexity due to the required structural and integration work. Modifying the differential to closely match the performance of the SSG configuration can be less expensive and improves energy efficiency due to the reduced number of drivetrain components. The WHM configuration potentially offers the most efficient solution by removing drivetrain components, but the increased unsprung mass degrades ride comfort and handling stability and increases exposure of the motor to road shocks and debris [

35]. These facts raise concern with respect to long-term reliability and maintenance needs, especially in the rougher terrain of rural areas.

Based on the evaluation, the DDC configuration demonstrates the best overall performance and is therefore selected as the final motor and drivetrain layout. The final drivetrain layout is illustrated in

Figure 9.

The motor placement is based largely on available space, but weight distribution and serviceability are also considered. Shafts 1 through 4 are linked by universal joints, with shaft 2 incorporating a slip joint to allow for longitudinal movement and supported by a bearing. Power is transmitted to the rear wheels through the differential assembly and rear axles (shafts 5 and 6).

A more conservative water-cooled motor is chosen to ensure reliable operation over a range of ambient conditions. The specifications for the selected motor are given in

Table 9.

This choice accounts for potential overloading and elevated thermal stresses that may occur in hotter climates, such as desert regions in SSA. While an air-cooled motor would be sufficient in specific regions, the diversity of climate conditions warrants this conservative approach. The selected motor still satisfies the speed, torque, and power requirement, but comes with trade-offs of increased weight and cost.

3.5.4. Inverter Selection

Inverters come in many different topologies, using different components and output modulation techniques [

37]. In many cases, motor suppliers recommend compatible inverter models that suit their motors and simplify integration. If no recommendation is given, the inverter must be chosen to match the battery pack and motor voltage and provide sufficient current for the motor’s peak- and continuous-current requirements.

For this study, the inverter recommended by the supplier is used, and its specifications are listed in

Table 10.

3.6. Battery Technologies and Selection

3.6.1. Battery Technologies

The selection of battery technology is critical to the performance, range, and power capabilities of EVs. In recent years, lithium-ion batteries have become the dominant option for EVs, replacing more conventional battery types such as lead-acid and nickel-based chemistries. At the same time, several promising chemistries are being explored as next-generation solutions, including advanced lithium-based systems, solid-state designs, aqueous systems, and metal-ion technologies (e.g., sodium-ion and zinc-ion).

A comprehensive study by Zhao et al. [

39] evaluates several battery technologies with several technical and environmental aspects. Lithium-ion battery technologies achieve the highest overall score, particularly due to their superior reliability and cycle life, reducing the risk of premature replacement. Lithium-ion batteries are also relatively affordable compared to other chemistries, which is important, given that the battery pack is one of the most expensive components in an EV [

40]. Furthermore, lithium-ion batteries show exceptional safety, an essential characteristic for vehicle applications. These characteristics make lithium-ion batteries a practical choice for rural delivery applications, where cost, durability, and dependable performance are critical.

Several lithium-ion chemistries exist, such as lithium cobalt oxide (

), lithium manganese oxide (

), and lithium iron phosphate (

), each with distinct characteristics [

41]. For this study, the lithium iron phosphate (LFP) chemistry is chosen based on its affordability and local availability. This battery chemistry is also generally regarded for its robustness, extended cycle life, excellent thermal stability, and safety.

3.6.2. Battery Performance Requirements

The battery power requirement is primarily determined by the motor power demand and adjusted to account for losses in the motor and inverter. The motor’s power demand is based on the peak and continuous power required during the drive cycle, as shown in

Figure 8c. Efficiencies are derived from the component supplier specifications. Since motor and inverter efficiencies vary with operating conditions, a conservative value is assumed to ensure the battery power requirement is not underestimated. The battery must also supply auxiliary loads. In this study, auxiliary systems, such as lighting, pumps, and control electronics, draw power through the DC/DC converter. An average load of 1 kW is added to account for these losses [

42]. The required battery power (

) can be expressed as

where

and

are the efficiencies of the motor and inverter, respectively, and

is the auxiliary load.

Table 11 lists the parameters and values used for this calculation.

The minimum usable battery capacity is determined by the target vehicle range and average energy consumption. For this study, a minimum range of 100 km is assumed to reflect typical distances between distribution centres and rural villages [

43]. The energy consumption is estimated based on the median of the WLTP-rated efficiency of comparable EV vans [

44], with an added margin to account for rural unpaved roads. This yields an approximation of 0.25 kWh/km, which is used for preliminary design.

Battery capacity specifications are typically expressed as Start-of-Life (SoL) capacity, which is the total energy available when the battery is new. The SoL capacity is selected to ensure that the vehicle can achieve the target range over the full operational life of the battery. This requires accounting for battery degradation, which reduces usable capacity over time, and depth-of-discharge, which prevents excessive deep cycling that could accelerate ageing. The required SoL capacity (

) can be calculated as

where

is the average energy consumption,

is the maximum depth of discharge, and

is the degradation over the operational life of the battery. The parameters and values are listed in

Table 12.

3.6.3. Battery Selection

The battery selected for this conversion consists of three LFP battery packs that are connected in series to form a battery system with characteristics shown in

Table 13. The battery exceeds the capacity requirement but is selected for its availability.

With component selection complete, the chosen components are implemented in a simulation framework. The following section presents the simulation model used to evaluate the vehicle performance under representative operating conditions.

4. Simulation Model

Building on the preliminary analysis and component selection, this section presents a detailed simulation model of the converted vehicle. While the vehicle dynamics from the previous section are kept, the selected drivetrain, motor, and battery components are now modelled in detail to better represent their behaviour and allow for validation of the final design. The following subsections describe the implementation of each subsystem within the model.

4.1. Overview of the Simulation Model

The simulation model implements a forward-facing, longitudinal vehicle simulation. In this approach, the drive cycle provides a target velocity that is compared to the simulated velocity within a driver model. The resulting accelerator and braking commands are the primary inputs to the powertrain. These commands are used by the inverter and electric motor model to output a corresponding torque. The torque is passed through the drivetrain model, which accounts for drivetrain losses and gear ratios before being applied in the vehicle dynamics to calculate the resulting acceleration, velocity, and position.

A braking system is included to balance regenerative and friction braking based on the selected braking strategy. The electrical system includes a DC–DC converter model to account for auxiliary power consumption and a battery model that captures the voltage behaviour, state of charge (SOC), and energy transfer during operation.

The model inputs consist of the target velocity from the drive cycle and environmental conditions such as road grade, ambient temperature, and wind speed. Component-level parameters, such as motor efficiency maps, drivetrain losses, battery characteristics, and vehicle mass properties, define the black-box behaviour of each subsystem. The model outputs the vehicle speed, torque, and power over time, with total energy consumption used as the primary performance metric.

4.2. Driver Model

The driver model is responsible for keeping the simulated vehicle velocity close to the reference velocity defined by the drive cycle. The main purpose is not to replicate realistic human driving behaviour but to generate acceleration and braking commands so that the vehicle follows the target velocity profile for performance evaluation.

A proportional-integral (PI) controller is used to model the driver due to its simplicity and ease of implementation. The controller calculates the velocity error, defined as the difference between the reference and simulated velocity. A positive error produces an acceleration command, while a negative error produces a braking command. Both commands are normalised from fully released (0) to fully pressed (1). The controller gains are tuned to minimise deviation between the reference and simulated velocity.

4.3. Drivetrain Model

In the preliminary analysis, drivetrain efficiency and effective rotational mass are considered at a high level. For the detailed simulation, minor mechanical losses and rotational inertias from secondary components, as illustrated in

Figure 9, are included to more accurately represent the drivetrain. The drivetrain parameters used in the simulation are listed in

Table 14.

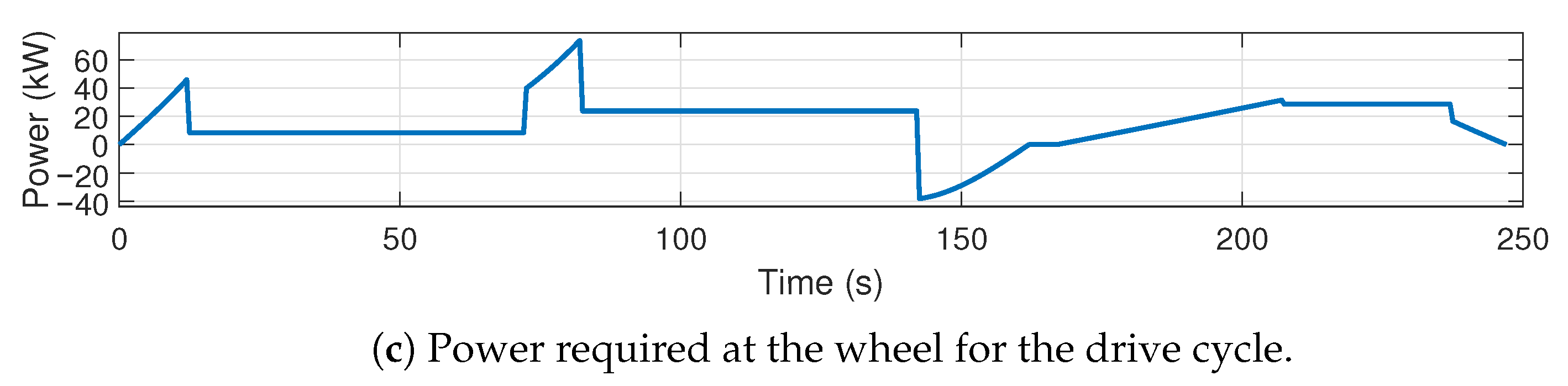

4.4. Electric Motor and Inverter Model

The electric motor is modelled using datasets from the supplier, which include a torque-speed curve, which defines the maximum torque over the speed range, and an efficiency map, which provides efficiency as a function of torque and speed, as illustrated in

Figure 10a. The efficiency map shows a lower peak torque than the motor is capable of, which is due to the inverter’s peak RMS current of 300 A limiting the motor’s power output.

The inverter is similarly modelled based on test reports from the manufacturer [

46], with its efficiency captured and converted to a torque-speed map over the operating range of the motor, as shown in

Figure 10b. The inverter efficiency varies with current and output frequency, with conduction and switching losses being the primary factors [

47], ranging from 80% to 95% under normal operating conditions.

In the simulation, the requested torque is determined based on the pedal position and limited by both the inverter and motor’s torque-speed curves. These datasets are implemented in the simulation through lookup tables, which allow the model to calculate the electrical power drawn from the battery at each time step. By combining the motor and inverter models, the simulation captures realistic behaviour, including energy losses and peak power constraints, ensuring an accurate representation across the full operating range.

4.5. Battery Model

The lithium-ion battery cell is modelled using the Thevenin equivalent circuit model (ECM) to determine the output voltage and SOC. This approach balances accuracy and computational efficiency, making it suitable for EV simulations [

48]. The model is shown in

Figure 11 and consists of an open-circuit voltage (

); an internal resistance (

) that accounts for ohmic losses; and an RC pair capturing the dynamic electrochemical behaviour—specifically, the transient response due to charge transfer and diffusion processes at the electrode–electrolyte interface [

49]. A single RC pair is chosen to simplify parameter estimation and reduce computational effort, though higher order models could improve accuracy.

The terminal voltage (

) is described as

The RC-pair dynamics are given by

The SOC is estimated using the ampere-hour integral method and defined as

where

is the state of charge at time

, and

is the nominal capacity of the cell. In a simulation environment, where sensor errors are not prevalent, this method for calculating the SOC is suitable. The model parameters of

,

,

, and

vary with the SOC and temperature. The parameter values are obtained from literature on LFP battery cells similar to those used in this study [

50].

4.6. Braking Model

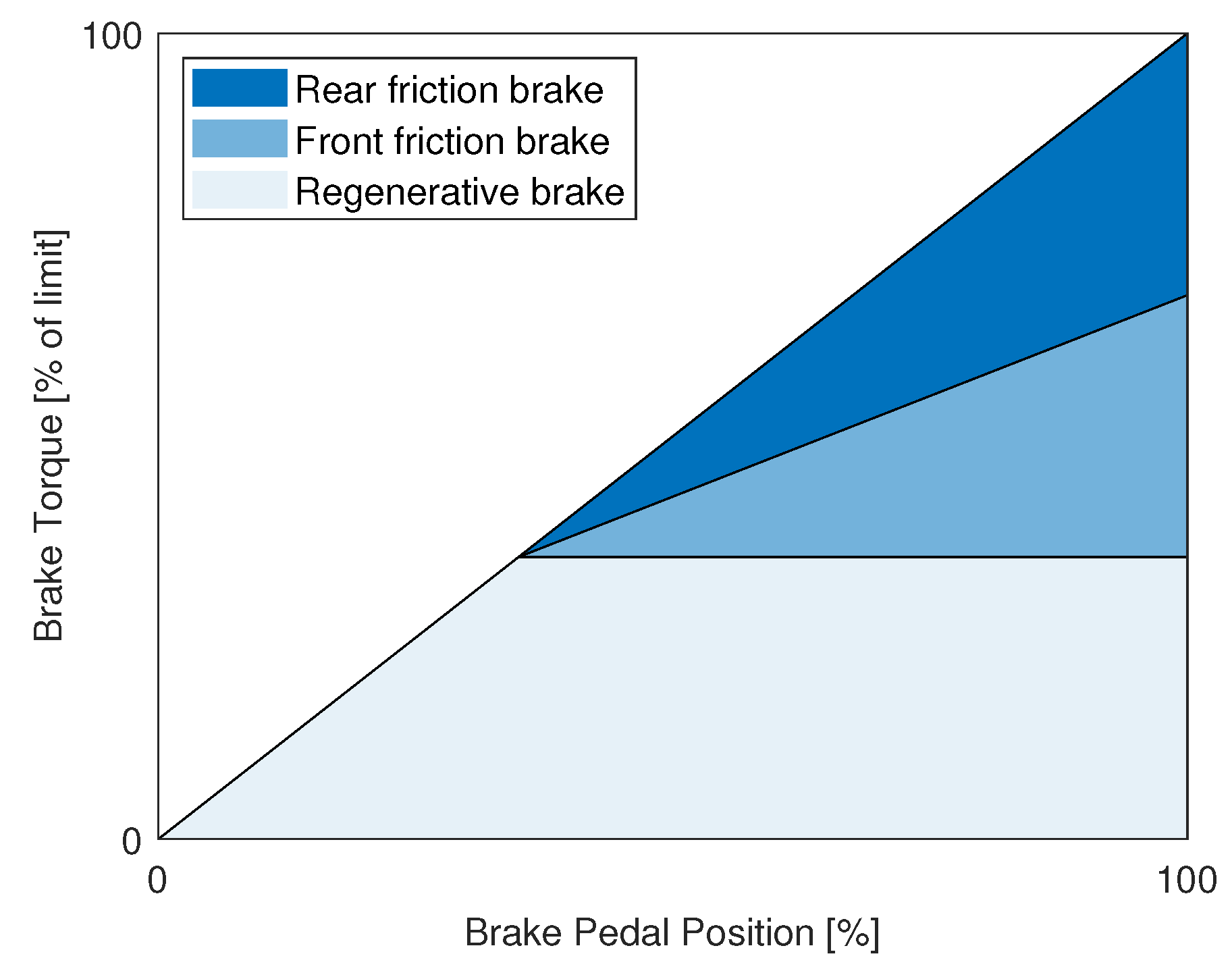

The vehicle retains the original hydraulic friction brakes and integrates regenerative braking through the motor for energy recuperation. In a serial braking distribution strategy, as shown in

Figure 12, the brake-pedal command first requests regenerative torque until the limit of the electric motor is reached, at which point the mechanical brakes provide additional torque. This approach shows higher energy recuperation compared to a parallel system, where regenerative and mechanical torques are applied simultaneously [

51].

In the simulation model, the brake-pedal command drives both regenerative and friction braking linearly. The braking system is constrained by the maximum braking torque (

) that can be applied before wheel slip occurs and is described as

where

is the tyre–road adhesion coefficient, typically around 0.8 for dry asphalt and concrete surfaces [

52]. This strategy allows for system-level analysis without detailed mechanical models or control algorithms.

4.7. Auxiliary System Model

Auxiliary systems can significantly impact energy consumption and should be accounted for in the model. Since replicating their exact operational conditions is challenging, the losses are approximated based on the auxiliary components installed in the converted vehicle. These values are derived from supplier datasheets and literature [

52]. A list of these components and their respective energy consumption can be found in

Table 15.

The DC–DC converter is modelled at a conservative constant efficiency of 93% based on supplier data. Charging of the auxiliary battery is excluded from the model, as it is assumed to be fully charged at startup.

5. Results

The EV conversion model is simulated to evaluate performance using drive-cycle benchmarking, sensitivity analysis, and a representative scenario-based simulation. Energy consumption is the key evaluation metric, as it quantifies the vehicle’s efficiency and operational feasibility. These results establish a performance baseline while providing insights into how environmental and design factors influence overall efficiency.

5.1. Validation of Requirements

The drive cycle defined in

Section 3.1 is simulated using the full vehicle model to validate whether the complete conversion is capable of meeting the performance requirements from

Table 3. The results confirm that the vehicle can achieve a maximum velocity of 100 km/h and satisfies the acceleration demands on level ground and on the maximum slope of 11.3°. In terms of performance, the vehicle accelerates from 0 to 60 km/h in 8 s, from 60 to 100 km/h in 7 s, and from 0 to 30 km/h on a slope in 31 s. This performance is achieved while the powertrain components remain within their operating limits. Overall, the simulated conversion meets all the baseline performance requirements.

5.2. Performance Comparison

The conversion performance is evaluated using the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP). The WLTP is a standardised test cycle developed using real-world driving data from around the world. The aim of the WLTP is to be used as a global test cycle so that carbon emissions and fuel/energy consumption values are comparable worldwide. The WLTP Class 3a drive cycle is suitable for vehicles with a power-to-mass ratio exceeding 34 W/kg and maximum speeds below 120 km/h [

53], which is appropriate for this study. This WLTP cycle is divided into four segments with varying average speeds—low, medium, high, and extra high—as illustrated in

Figure 13.

The simulated velocity is compared to the reference WLTP velocity profile using the Root-Mean-Squared Error (RMSE) to quantify the alignment accuracy. The RMSE measures the average magnitude of velocity deviations [

54] and is calculated as

The RMSE is 0.3893 km/h, indicating high fidelity to the WLTP cycle. Comparable EV simulation studies rarely report RMSE values for cycle-speed matching, and no widely accepted benchmark exists for this metric. An error of this magnitude represents a deviation of well under 1% across typical operating speeds and is sufficiently low to support the reliability of the simulation results.

The WLTP range is the maximum distance an EV can travel on a single charge based on a standardised test. It is calculated by dividing the usable battery capacity by the measured energy consumption across two consecutive cycles [

55].

Table 16 compares the Suzuki Super Carry conversion with seven similarly classed electric vans, focussing on battery capacity, power, torque, WLTP range, and WLTP energy consumption. Data is sourced from manufacturer specifications, while the converted vehicle data is from the simulation results.

Figure 14 illustrates the relationship between the battery capacity and WLTP range for the selected vehicles.

The Suzuki Super Carry conversion’s consumption of 217 Wh/km aligns closely with vehicles like the Mercedes-Benz EQT 200 Long (218 Wh/km) and the Volkswagen e-Crafter (207 Wh/km). However, its range-to-capacity ratio slightly underperforms compared to some peers, such as the Nissan Townstar EV (285 km, 45 kWh) and the Ford e-Tourneo Courier (266 km, 43.6 kWh), which achieve a greater range with a smaller battery. The discrepancy is largely due to the conversion nature of the vehicle, with components not optimally integrated, leading to increased weight and powertrain inefficiencies. Additionally, the Suzuki’s less streamlined body increases energy consumption, particularly at higher speeds, further limiting the range when compared to purpose-built commercial EVs.

Overall, the EV conversion demonstrates energy consumption similar to that of several commercial electric vans, though its range is somewhat shorter relative to its battery capacity.

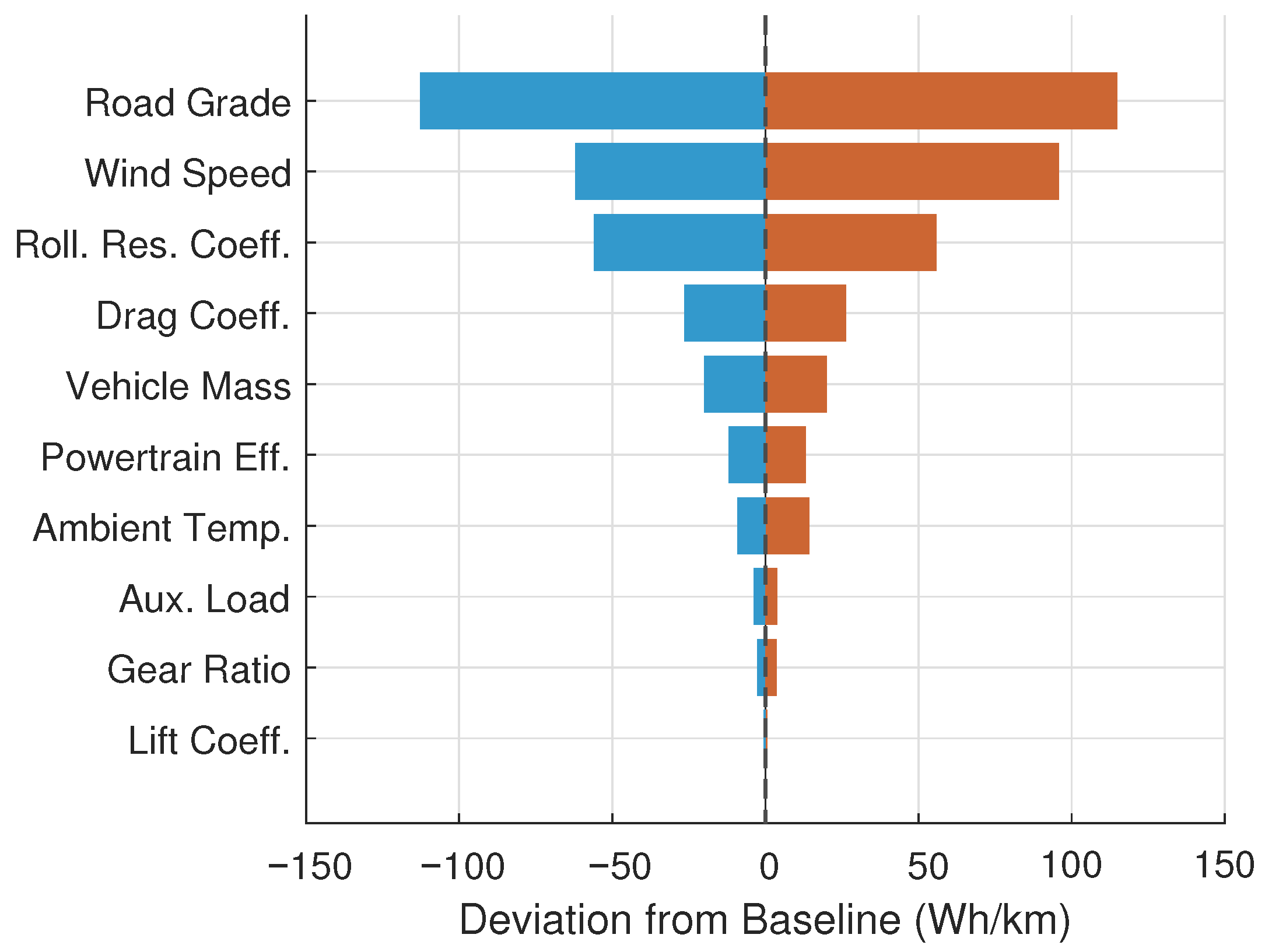

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis aims to identify which environmental and design factors most strongly influence vehicle energy consumption. This allows for an informed refinement of model accuracy and design improvement by focussing on the most influential parameters. A one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach is applied, where each input parameter (

) is varied individually while keeping all others constant at their baseline values, i.e.,

[

28]. Sensitivity cases

and

represent the upper and lower boundaries of each parameter and are combined into input vectors

and

. The change in output is quantified as

The parameter ranges are chosen to be symmetric around the baseline and kept within realistic operating ranges to reflect real-world conditions. The output differences are visualised using a tornado diagram, where each bar represents a change in energy consumption as a parameter is shifted from its lower to upper boundary.

There are numerous factors that influence the vehicle’s energy consumption, including vehicle design, driver behaviour, and the environment. For this analysis, a set of parameters is selected based on their expected impact and availability in the model. These factors are listed in

Table 17 and include the baseline, as well as the upper and lower boundaries. The environmental factor ranges reflect real-world operating conditions, while design factor ranges capture uncertainties in vehicle modelling and component performance.

The sensitivity analysis is conducted using the WLTP drive cycle (see

Section 5.2), as it covers a versatile speed profile and provides a representative range of operating conditions.

Figure 15 illustrates the tornado plot for the environmental and vehicle design factors.

Among the environmental factors, road grade, wind speed, and rolling resistance have the largest impact. Road grade has a significant effect, with a ±115 Wh/km shift from slopes of −3% to 3%. This highlights the importance of road grade as a critical consideration for route planning in SSA’s varied terrain.

A 30 km/h tailwind reduces energy consumption by about 62 Wh/km, while a 30 km/h headwind increases it by just below 100 Wh/km. The effect of wind speed increases sharply at higher speeds, reflecting the exponential relationship between aerodynamic drag and relative speed. Exponential sensitivity means that extreme wind conditions can significantly influence real-world operation.

Rolling resistance shows a similarly strong influence, with energy use varying by ±55 Wh/km when varying the coefficient from 0.005 to 0.035. This indicates that road surface characteristics can strongly influence energy use, which is important for rural SSA, where many roads are unpaved.

Ambient temperature has a moderate effect. Lower temperatures increase energy use due to higher battery resistance and denser air, while higher temperatures reduce both. However, higher temperatures may reduce powertrain performance due to thermal derating and should be considered in hot climates.

For vehicle-related factors, the strongest influences on energy consumption come from aerodynamic drag, vehicle mass, and powertrain efficiency. Varying the drag coefficient between 0.35 and 0.55 changes energy consumption by ±26 Wh/km, while the lift coefficient has a negligible impact of less than 1 Wh/km. This demonstrates the importance of aerodynamics in vehicle design, though body modifications to improve aerodynamics in conversion applications are often limited by structural and cost constraints.

Vehicle mass causes a linear shift of ±20 Wh/km per ±250 kg, highlighting the benefit of lightweight design and load management in delivery applications. Variations in powertrain efficiency shift energy use by around ±12 Wh/km, emphasising that maintaining high component efficiency through design, calibration, and maintenance can yield energy savings. Auxiliary loads contribute modestly, shifting energy use by about ±4 Wh/km across the studied range. The gear ratio has a relatively minor influence but remains important to torque and speed performance.

5.4. Scenario-Based Performance Evaluation for SSA Conditions

The sensitivity analysis in

Section 5.3 isolates the effect of individual parameters on energy consumption. However, vehicle operation is characterised by the variation of several factors simultaneously. To capture these combined influences, representative operating scenarios are defined and simulated. Each scenario combines road characteristics, the drive cycle, and grade conditions into a use case that reflects rural SSA to allow for performance evaluation in practical operating environments.

Three use cases are considered to represent shorter, medium, and longer trips. Short trips correspond to local-access transport within villages or farms, typically at lower speeds. Medium trips represent regional transport between villages, local markets, or clinics. Longer trips correspond to remote-access transport to distant villages, where reliability and range are critical.

Vehicle performance is simulated using standardised drive cycles representative of the defined scenarios. The Artemis Urban cycle is applied to reflect lower speed operation and frequent stop–start behaviour. The Artemis Rural cycle is used to capture mixed-speed driving with steady-state segments. The Highway Fuel Economy Test (HWFET) cycle represents higher cruising speeds for longer-distance travel.

To isolate the effects of road conditions and terrain, only the rolling resistance coefficient and road slope are varied, while other parameters identified in the sensitivity analysis are kept at their baseline values. Vehicle mass is fixed to the gross vehicle weight (GVW) to simulate the worst-case load condition, reflecting a fully utilised vehicle in the rural transport context. This approach provides a clear evaluation of how terrain characteristics alone influence vehicle performance in SSA.

Table 18 shows the simulation input parameters and ranges, excluding the three drive cycles described previously.

A Monte Carlo framework is implemented to capture the variability in operating conditions. For each scenario, the key parameters are randomly sampled from a uniform distribution over the defined ranges. Each sampled parameter set is applied to the vehicle model, and the corresponding drive cycle is simulated once to determine the energy consumption for that run. This process is repeated for a sample size of 1000 runs per case, from which the average energy consumption is determined for each case, illustrating the vehicle’s capabilities across the defined use cases.

Figure 16 summarises the simulation results for average energy consumption for the different scenarios.

The results show that energy consumption increases with scenario type, rising by roughly 40–60 Wh/km from local access to remote trips for both paved and dirt roads, largely due to higher average speeds that raise aerodynamic losses. Dirt roads nearly triple energy use compared to paved roads, highlighting the dominant influence of rolling resistance on unpaved surfaces. Slope further affects energy use, with uphill segments increasing average consumption by roughly 120–150 Wh/km across both paved and dirt roads, while downhill segments reduce consumption, with an added benefit from regenerative braking. Using the usable battery capacity of 51.4 kWh, these energy consumption values correspond to average ranges of around 294 km on paved roads and 83 km on dirt roads for a fully loaded vehicle during local-access trips, which should comfortably meet typical village and farm transport needs. For regional and remote trips, average ranges are roughly 244 km and 223 km on paved roads and 81 km and 78 km on dirt roads, respectively, indicating that longer, high-speed operations place greater demand on the battery.

The results provide a practical benchmark for operational planning, showing where the vehicle is well suited, where energy use is elevated, and the potential need for route planning or payload management on longer trips. Overall, the vehicle exhibits predictable performance across all considered SSA use cases.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and applied a simulation-based framework to evaluate the performance of an EV conversion for rural SSA. By combining WLTP benchmarking, sensitivity analysis, and scenario-based simulations, the vehicle’s energy consumption and range were assessed under representative conditions.

The results demonstrate that the EV conversion achieves energy consumption comparable to that of several commercial electric vans, though its range is somewhat reduced relative to its battery capacity. The sensitivity analysis confirmed that road grade, aerodynamic drag, and rolling resistance are the dominant drivers of variability in energy use. Scenario-based evaluation further showed that the vehicle is well suited for local-access trips, where energy consumption is low and the vehicle can reliably meet typical daily travel needs within rural villages and farms. For regional and remote transport, energy demands increase due to higher speeds, but the vehicle can still perform adequately for many use cases with appropriate planning.

While the simulation provides a high-level evaluation, several limitations must be acknowledged. The half-vehicle model does not account for lateral dynamics, wheel slip, or turning. The drag coefficient is an approximation, and the rolling resistance is simplified as a constant value. These simplifications may lead to under- or overestimations of energy consumption, particularly over longer drive cycles.

From a practical perspective, the stock Suzuki Super Carry is not designed for rough off-road terrain, which could require additional modifications, such as off-road wheels. Given the diversity of climates across SSA, including high temperatures, humidity, and dusty conditions, vehicles may require further adaptations depending on the specific environment. Different base vehicles may be considered for higher payloads, although this could increase cost. Furthermore, high component costs, particularly for motors and batteries imported into SSA, could limit real-world adoption, especially in lower income rural areas. The charging solution for the converted vehicle is designed for AC grid connection, which is widely available compared to DC charging. However, roughly 600 million people in SSA lack reliable electricity access [

59], which could limit adoption in some regions. A deployment strategy must be planned to address these infrastructural constraints.

Future work should focus on refinement of the simulation model, real-world validation of results, inclusion of dynamic terrain effects, and exploration of additional vehicle models. Other important aspects include planning for rural electrification, the integration of alternative charging solutions, and the scaling of conversions to meet regional mobility needs.

These findings establish a benchmark for the performance of light delivery vehicle conversions in rural SSA and highlight the viability of EV conversions as a way to expand sustainable mobility. The study demonstrates how simulation-based design tools can guide vehicle modifications, support the development of local technical skill, and inform decisions about energy use and range under representative conditions. Ultimately, this approach supports the wider adoption of affordable, sustainable, and locally adaptable EV solutions across diverse rural contexts.