1. Introduction

The development of offshore wind farms (OWFs) has accelerated significantly since the commissioning of Vindeby in Denmark in 1991, marking the world’s first offshore wind installation, with a total capacity of 4 MW [

1], as shown in

Figure 1. This stands in great contrast to the OWFs built today, such as Hornsee-2, with an installed capacity of 1.3 GW (

Figure 1).

Since then, global offshore wind capacity has expanded rapidly, reaching approximately 117 GW by 2023, and is projected to grow to 234 GW by 2030 [

2,

3], as shown in

Figure 2. This growth is driven by the global transition to renewable energy, with over 50 countries now operating offshore wind assets across all continents [

3].

Commercial wind turbines have undergone significant evolution, with single units now capable of reaching up to 14 MW in rated power. In comparison, prototypes are being tested at 18 MW, and future concepts envision capacities of up to 22 MW [

5,

6].

In general, considering the Baltic Sea, it is evident that from the perspective of grid companies, midterm trends are shifting from the awarded few GW wind farms to more than 10 GW of power generation, with a further outlook of a few tens of GW in the future [

7].

However, this rapid expansion presents significant technological and operational challenges. Considering countries’ ambitions to achieve up to 50% of power generation from offshore wind farms in the future and to ensure a reliable power supply, it is necessary to place greater emphasis on the accreditation and technical verification of proposed and future technological choices and solutions.

In particular, due to the extremely high demand for upscaling, current technological solutions pose a significant risk to design and manufacturing, installation, quality assurance, and technical end-verification. This may pose risks to the reliability of offshore wind farm power generation and to investment returns. As noted in [

8,

9], the power cables in an offshore wind farm are critical assets in terms of failure frequency and severity.

Therefore, the authors will continue in this contribution a discussion on technical reliability challenges for OWF power cables, having in mind

- (a)

The very fast-changing world of OWF developments;

- (b)

That since the discussion started in 2019 by some of the authors on this topic, not many solutions have been proposed to the critical issues in [

10,

11,

12,

13];

- (c)

That, e.g., at the last Cigré 2024 biennial meeting, the Working Group B1 Insulated Cables Conference, presented a total of 85 papers, of which only one contribution was partially dedicated to the topic of OWF cables.

Field experience indicates that approximately 12% of newly installed cable circuits fail their initial acceptance testing, with the vast majority of failures occurring at joints and terminations. In most cases, these problems are linked to workmanship issues during assembly rather than to design limitations (about 80%). This situation is much more remarkable and worrisome because, when considering the total costs of a wind farm, the offshore cables, including offshore cable laying, account for less than 20% of the total capital costs [

1,

2,

3,

5].

Most problems are due to poor workmanship during cable installation and assembly, including [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]

- (a)

Incorrect mounting dimensions;

- (b)

Use of inappropriate materials and/or tools;

- (c)

Missing and/or incorrectly installed parts that distribute the electric field in joints and terminations, e.g., insulating tapes, spacers, fillers, defective deflectors, semiconductor materials, and so on.

It is evident from the above discussion that quality control is needed at all stages of cable design, manufacturing, installation, and operation. One of the most essential methods to ensure the desired quality is testing the equipment at various stages of the cable’s life. In particular, site acceptance testing (SAT) should be carefully designed and executed.

At present, the most common tests are

- (a)

A 24 h soak test at the nominal operating (network) voltage (U0) for export cables and/or inter-array cables;

- (b)

VLF (very low frequency) voltage-withstand tests on individual IAC sections.

These tests do not provide a complete picture of the equipment’s condition, and they should be supplemented by comprehensive PD (partial discharge) detection or localization. At present, there are two widely used approaches for partial discharge testing:

- (a)

AC resonance testing (ACRT);

- (b)

Damped AC testing (DAC).

The ACRT test has been used for a long time and has proven very useful for testing land cables. On the other hand, the DAC approach has been used for about 20 years and shows substantial growth in applications, especially in offshore cable installations.

Since there are no universally agreed-upon testing procedures for offshore power cables, the authors undertook a comprehensive comparison of all site acceptance testing methods applicable to submarine cables. The findings of this study are reported in the following sections of this paper.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 contains an introduction to the role of power cables in an offshore wind farm design. In particular, the statistics on cable failures are compared with those of other wind farm components.

Section 3 reviews the available cable testing methods with an emphasis on key considerations for selecting appropriate SAT methodologies for both export and inter-array cables.

Section 4 describes cable testing techniques. The emphasis is on illustrating the main differences among the test methods currently used to test OWF cable systems.

The following two chapters are devoted to a detailed analysis of the available test methods for the export and the inter-array cables.

Section 5 deals with export cables and concentrates on the comparison of the two primary PD testing methods, ACRT and DAC. Comparison includes such parameters as cost and manpower, electromagnetic background noise interference, and the possibility of cable damage during the test.

Section 6 deals with inter-array cables. As in the previous chapter, key testing parameters for ACRT and DAC PD testing methods are compared, including PD localization along the entire cable length.

2. Offshore Wind Farm Power Cables

Most offshore wind farms have a typical configuration in which wind turbines, each of several MW, are connected by inter-array cables in strings, and all strings are connected to one or more offshore substations (OSSs). Currently, the state of the art is at 66 kV, with an expected transition to 132 kV as turbines continue to scale up. The connection of the OSS to the onshore grid is accomplished via one or more export cables (mainly in the 220 kV or 275 kV range), as shown in

Figure 3.

In [

6], an extensive discussion is provided on all matters related to failures of both the export and inter-array cables, as shown in

Figure 4. Also, recommendations have been made for quality assurance of OWF cable systems. Moreover, since the 2021 discussion about the basic risk factors of cable failures at the OWF, there has been little progress in addressing those problems [

10].

According to Reference [

10], the severity and frequency of failures of the export and inter-array cables are reported to be the highest compared to other offshore wind farm components, such as wind turbine foundations, transformers, generators, and switchgear.

It is reported in [

6] that over the past 20 years, power cable failures have accounted for up to 80% of total financial losses and OWF insurance claims worldwide. Failure to apply proper preventive measures may result in

- (a)

Randomness of the solutions used to dictate by the optimization of prices and schedules;

- (b)

Numerous disputes regarding compensation for improper technical workmanship or defects during the warranty period;

- (c)

Unacceptable lack of reliability requirements due to the low level of quality assurance in the design, production, transportation, and installation processes.

Based on the expectations of the on-site acceptance test, this article discusses the fundamental aspects of achieving higher reliability and, consequently, lower failure costs for inter-array and export power cable connections in offshore wind farms.

According to [

9], for inter-array and export cables used in OWFs, four main failure modes can be distinguished: 46% incorrect installation, 31% manufacturing irregularities, 15% ineffective cable design, and 8% external damage (see

Figure 5).

The same reference also reports that challenging conditions at sea can affect not only the failure rate but also the time required to repair a failure, thereby causing variations in the resulting downtime. Based on past data analysis, the average downtime due to inter-array cable failures and repairs was 38 days, and the average downtime due to export cable failures and repairs was 62 days [

9].

The above discussion is based on the existing feedback from midsize WTGs of a few hundred MWs and inter-array cables, with voltage ratings of 33 kV and 66 kV. Considering the above statistics, there is no doubt that the causes of these problems must be examined in relation to the reasons for cable failures.

It is expected that, if nothing is performed, the problems with cable failures will worsen, as the voltage levels will soon double to 132 kV for the inter-array cables. New wind farms will be installed at greater depths by transitioning to floating wind farms.

Therefore, in the following sections, the technical aspects of quality assurance for site acceptance testing (SAT) for both OWF export and inter-array cables will be discussed.

3. Testing Considerations

The export (EC) and inter-array (IAC) cable systems at offshore wind farms (OWFs) present distinct challenges during post-installation testing due to their physical and electrical characteristics.

Export cables, typically rated between 220 kV and 275 kV, span distances from several tens of kilometers. These lengths result in very high cable capacitance—often exceeding 20 µF—which, in turn, requires substantial reactive power to energize using conventional alternating current (AC) test systems. The size and power demands of these systems make conventional AC resonant test systems’ site acceptance testing (SAT) impractical for export cables.

Inter-array cables, generally rated up to 66 kV, connect clusters of wind turbines (typically 5 to 10) in string configurations to the offshore substation. While individual IAC segments may be only 1–4 km long, even longer lengths can be applied, allowing the full length of a complete string to extend up to 15–20 km. Testing these strings in their entirety is logistically complex due to limited access and space constraints on the WTG or offshore substation platforms. As with export cables, conventional AC testing systems are often unsuitable due to their large footprint, weight, and power requirements. Moreover, it is technologically impossible to conduct dedicated tests (monitored by accurate partial discharge measurement) during on-site acceptance tests.

Due to these limitations, some developers opt for simplified or minimal SAT approaches, driven by time, cost, and logistical constraints. Common practices include

- (a)

Performing a 24 h soak test at the nominal operating (network) voltage (U0) for export cables and/or inter-array cables;

- (b)

Using VLF (very low frequency) voltage withstand tests on individual IAC sections;

- (c)

Omitting comprehensive PD (partial discharge) detection or localization.

This automatically generates a risk for quality assurance for the OWF operation. To address these concerns,

Table 1 and

Table 2 outline key considerations for selecting appropriate SAT methodologies for both export and inter-array cables. These include

- (a)

The complexity of the offshore logistics (weather, access, vessel availability);

- (b)

The need for high diagnostic sensitivity, especially in detecting and locating defects in accessories such as joints and terminations;

- (c)

Time- and cost-efficiency of test execution;

- (d)

The trade-off between system compactness and test performance.

A best-practice approach to SAT should be based not solely on regulatory minimums but also on what is technically feasible, logistically efficient, and diagnostically meaningful. Testing strategies must be selected with a focus on long-term reliability, ensuring that defects introduced during manufacturing, transport, or installation can be identified and corrected before the system is energized.

Currently, to reduce the cost of ensuring quality after installation, e.g., by reducing the SAT criteria to minimum possible, some subcontractors impose a defect notification period (DNP) on their clients. DNP is an agreed-upon, short-term period within which the client must notify the subcontractor of detected defects.

In the case of warranties that involve quality or performance over an extended period, the DNP often covers the repair or replacement of defects noticed shortly after installation.

The DNP could be a procedural requirement for enforcing warranty rights, but it does not guarantee quality. Of course, this approach does not meet the reliability expectations that owners of investment properties have in offshore wind farms.

Regarding the requirements for post-installation testing and quality assurance, [

10,

11,

12,

13] point out that special attention should be paid to long sections of the offshore export power cables. However, these publications do not provide any concrete suggestions, see

Table 1 and

Table 2, for example, on

- (a)

How can the required power be generated on-site, high voltages to overstress long cable circuits, e.g., those with lengths of 50 to 120 km or capacitive loads greater than 15 µF [

12,

13]?

- (b)

How can partial discharge (PD) events be accurately detected and localized in long cable systems [

12,

13]?

- (c)

What criteria apply for adequate quality assurance of newly installed or in-service cable circuits [

12,

13]?

According to IEC standards, an alternative to the overvoltage test is a 24 h voltage-withstand test at a power frequency of 50 or 60 Hz and at the normal operating voltage Uo.

It is recognized that this solution has limited value in detecting potential weaknesses in a newly installed cable system due to the lack of stress, particularly the inability to detect partial discharge.

It is known that repair costs for long cable installations, especially offshore, are high [

8,

9,

12,

13]. Therefore, a proper quality assurance process must be agreed upon, including typical characteristics of long offshore cable systems:

- (a)

The need to conduct PD tests of the entire cable section (turntable) at the factory before shipping it for on-site installation;

- (b)

The presence of pre-installed (factory-installed) joints;

- (c)

The presence of joints installed on-site at sea;

- (d)

Accessibility and space constraints that affect access to the offshore cable;

- (e)

The impossibility of conducting distributed partial discharge tests on individual connectors of the submarine cable.

In the following sections, we will examine the performance of various testing technologies—exceptionally damped AC (DAC) and AC resonant (ACRT) methods—and evaluate their effectiveness in offshore applications. Special attention will be paid to testing reliability, partial discharge detection, diagnostic capability, and overall suitability for the long-length cable systems.

It should be noted that, although there are several references on the application of the DAC methodology for long-length AC cable lines [

6,

7,

13,

16], only one publication [

17] describes AC resonant testing (ACRT) for cable lines with a long length.

4. OWF Power Cables Testing Technologies

To ensure the long-term performance of the offshore wind farm (OWF) cable systems, it is essential to apply suitable high-voltage testing technologies after installation. Over the past two decades, several testing methods have been developed and standardized to verify the insulation integrity and operational readiness of long, high-voltage power cable systems.

Among these, two prominent techniques recognized in international and national recommendations [

10,

11,

12,

13,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] and industry practice are

- (a)

AC Resonant Testing (ACRT)—Continuous AC voltage testing at frequencies between 20 and 300 Hz;

- (b)

Damped AC Testing (DAC)—Application of damped resonant voltage signals within the same frequency range.

Figure 6 illustrates the main differences among the test methods described above. Both methods have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Regarding the similarities in the results of both voltage testing methods on the same type of insulation defects, the following statements can be made [

10,

11,

12,

13,

21,

22,

29]:

- (a)

There is no significant diversity between the partial discharge inception voltage (PDIV) and partial discharge extinction voltage (PDEV).

- (b)

Between detectable partial discharge levels, no differences have been reported.

- (c)

DAC cycles make the occurrence of partial discharges in relation to the DAC voltage decay visible, providing more information about the partial discharge pattern.

- (d)

At the maximum voltage level, there is no effect of diversity in the voltage stresses in kV/mm. The damaging effect of the DAC test voltage is lower than that of AC stress due to DAC voltage decay.

- (e)

There is no significant diversity for dielectric losses as measured at similar test voltage levels and voltage frequencies in the range of 10–300 Hz.

- (f)

The development of various on-site power cable testing methods [

5] over the past two decades has provided parameters for repeatable quality control (see

Table 3).

Considering the fundamental aspects of quality assurance of the OWF export cables, several testing and diagnostic parameters have been developed over the past few decades for post-installation testing of power cables [

11,

12], as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Referring to

Table 4 and based on the authors’ extensive worldwide experience in successfully testing power cables using the SAT method in hundreds of different installations with voltages up to 275 kV,

Table 5 summarizes the recommended testing parameters.

5. Technical Comparison of Testing Methods of OWF Export Cables

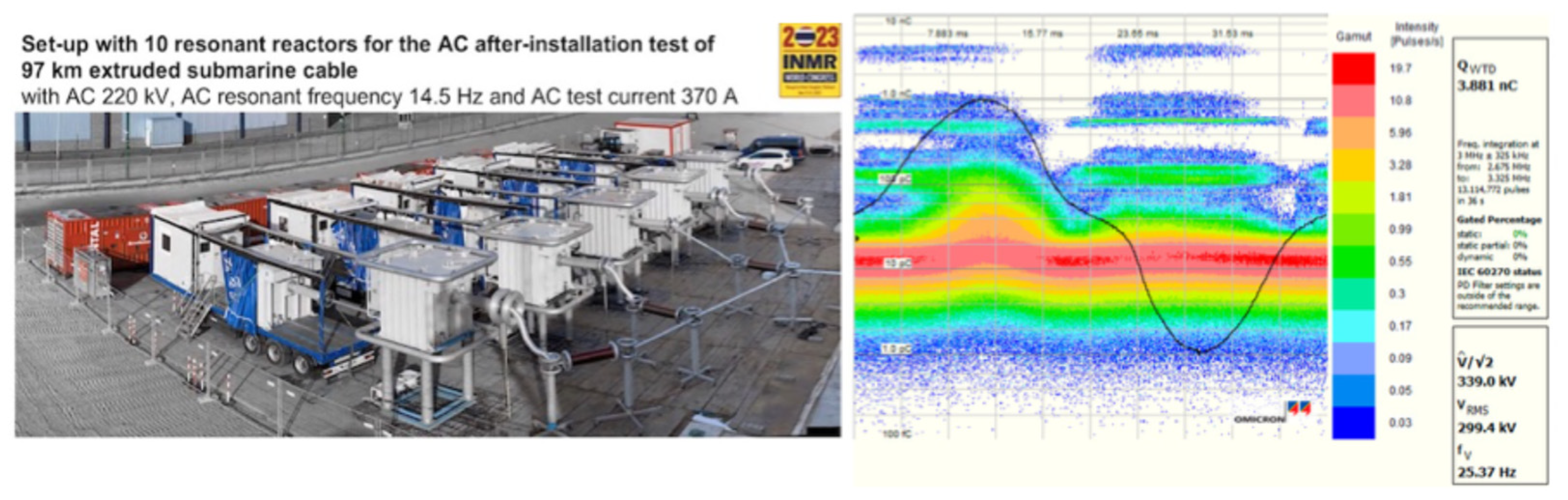

AC resonant testing (ACRT) is not easy to apply. It does not provide a clear picture of the possible presence of PD activity over long lengths, which are typical for OWF export cables, as shown in

Figure 7.

As a result, the following conclusions for testing EXC systems using ACRT can be made

- (a)

Very high effort regarding time, costs, and manpower to set up and to energize the test object;

- (b)

Lack of possibility to detect and to localize discharging defects in the complete cable system due to very high electromagnetic background noise (see

Figure 7);

- (c)

High destructiveness to the cable system due to the continuous character of the AC high over-voltage;

- (d)

Very low price/performance ratio for developers and contractors.

Site acceptance testing of very long cable lengths using the damped AC (DAC) method is a straightforward and easy-to-apply approach. It provides a clear picture of PD activities, as shown in

Figure 8. As a result, the following conclusions for testing EC systems using DAC can be made:

- (a)

Low effort regarding time, costs, power demand, and manpower due to the very compact test system;

- (b)

Possibility to detect and to localize discharging defects in the complete cable system due to very low electromagnetic background noise interference;

- (c)

No destructiveness to the cable system due to the damped character of the AC high over-voltage stress and PD monitored test.

Considering the fundamental aspects of quality assurance for OWF export cables, several testing and diagnostic parameters have been developed over the past few decades, following the implementation of the post-installation testing for power cables [

10,

11,

12,

13], as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Based on the above discussion, several essential aspects were selected and analyzed from a quality assurance perspective for newly installed OWF export cable circuits to support decisions on the advantages and disadvantages, risks, and impacts of all possible SAT methods for OWF export cables.

Based on the above multi-criteria comparison, damped AC testing appears to be the most appropriate and effective SAT method for export cables with lengths exceeding 30 km, and it is undoubtedly suitable for typical lengths of 80–120 km. It meets both the technical and logistical demands of offshore applications, with a robust assessment of cable condition before commissioning. In contrast, both ACRT and soak testing fail to provide sufficient diagnostic resolution or practical deployment flexibility for long offshore cable systems.

6. Technical Comparison of Testing Methods of OWF Inter-Array Cables

Site acceptance testing of IAC using AC resonant testing (ACRT) is not straightforward or easy to use. It does not provide a clear picture of PD activities (see

Figure 9). As a result, the following conclusions for testing IAC systems using ACRT can be made:

- (a)

PD-monitored testing, including localization of a complete cable string, is not possible due to a lack of sufficient power and the presence of high EM interference.

- (b)

Very high effort regarding time, costs, and manpower due to the considerably large size and number of the systems needed to energize a power cable.

- (c)

No possibility to detect and to localize discharging defects in the complete IAC strings due to very high electromagnetic background noise.

- (d)

High destructiveness to the cable system due to the continuous character of the AC high over-voltage.

- (e)

Very low price/performance ratio for developers and contractors.

Site acceptance testing of inter-array cables for an OWF using the damped AC (DAC) method is straightforward. It provides a clear picture of PD activities, as shown in

Figure 10. As a result, the following conclusions for testing IAC systems using DAC can be made:

- (a)

PD-monitored testing, including localization of discharges in a complete cable string, is possible.

- (b)

Low effort regarding time, costs, and manpower due to a very compact solution needed to energize a power cable.

- (c)

Possibility to detect and to localize discharging defects in the complete cable system due to very low electromagnetic background noise.

- (d)

Due to the damped character of the AC high over-voltage stress and PD monitored test, there is no destructiveness to the cable system.

To support decisions on the advantages and disadvantages, risks, and impacts of all possible site acceptance testing methods for offshore wind farm inter-array cables, several key aspects were selected based on the above discussion and analyzed from the perspective of quality assurance of newly installed OWF interconnect circuits. It compares the most common testing methods applied to the IAC systems:

- (a)

Damped AC (DAC) Testing;

- (b)

Very Low Frequency (VLF) Testing—Sinusoidal or cosine-rectangular at 0.1 Hz;

- (c)

Soak Testing at U0.

Each method is evaluated based on its technical capabilities, diagnostic performance, suitability for offshore deployment, and impact on testing logistics.

Table 12,

Table 13,

Table 14,

Table 15 and

Table 16 summarize the analysis of each technical aspect.

Based on the detailed technical evaluation of various testing methods for inter-array cables and strings considered by different OWF projects, it can be concluded that both VLF and ACRT lag in these areas and are primarily suited to simpler, shorter, or onshore applications. Soak testing is not considered meaningful for SAT in any modern OWF context. The most suitable SAT method is damped AC (10–300 Hz) with sensitive PD detection and localization (see

Table 4).

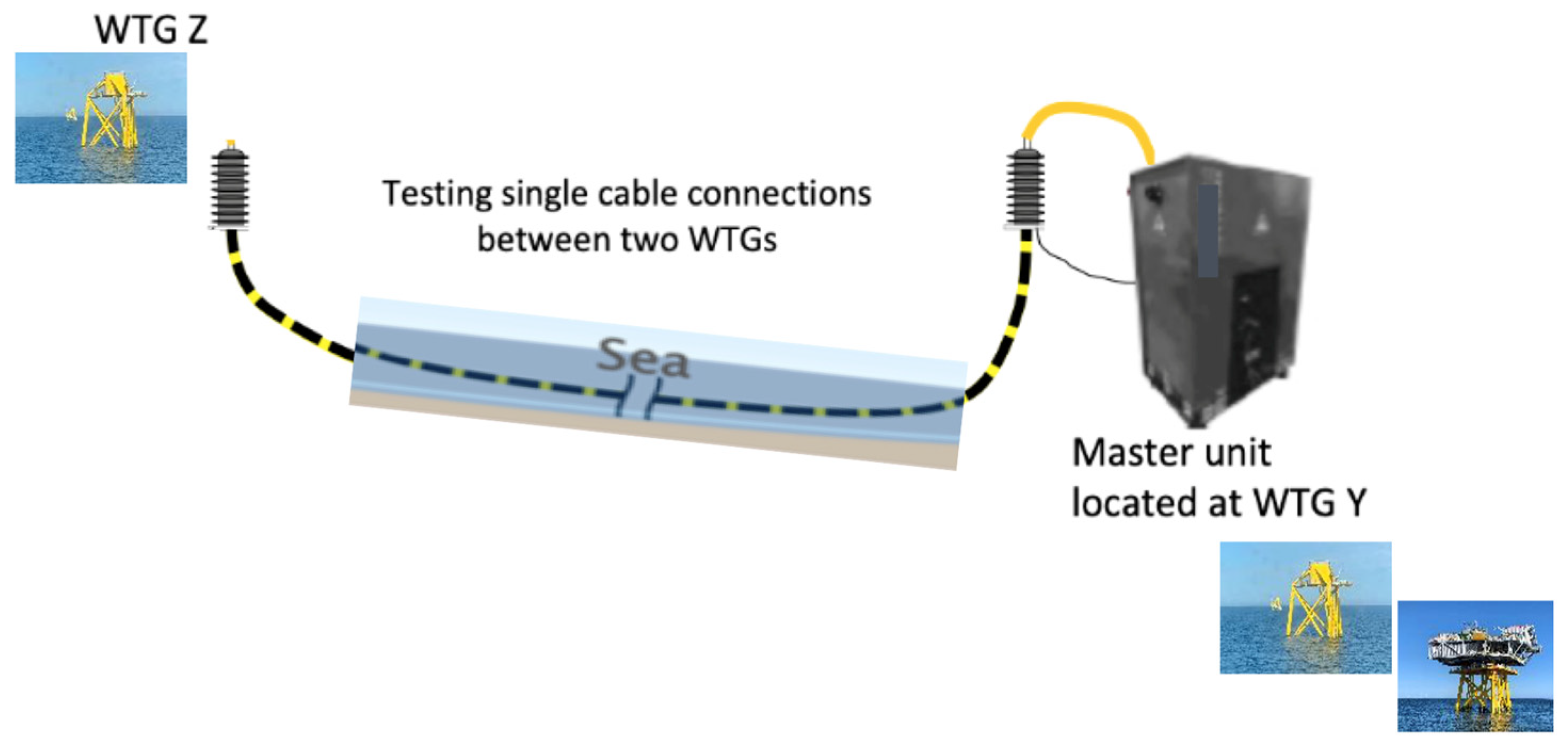

In recent international projects where damped AC (DAC) with partial discharge (PD)-monitored testing has been applied, it has been observed that moving away from the conventional testing of single cable sections (between individual WTGs), as shown in

Figure 11, to testing of a complete IAC string, as shown in

Figure 12 (e.g., from the offshore substation to the last WTG in the string), has the following advantages (see

Table 17):

- (a)

Testing full strings allows verification of all components under real operating configurations.

- (b)

The number of required tests is reduced by up to 80%, significantly decreasing preparation, execution time, and costs.

- (c)

Complete strings yield more representative condition data, valuable for future condition-based maintenance (CBM) strategies.

A detailed comparison in

Table 17 confirms that complete string testing provides a reduction in test count and improved coverage of the complete IAC connections.

Being combined with sensitive PD detection, as shown in

Table 4, it offers not only superior technical reliability, but also considerable logistical and economic advantages, which could be annotated to emphasize the reduction in test count and improved coverage.

The comparison of the available SAT methods confirms that DAC is the most effective and practical approach for verifying the integrity of the OWF inter-array cable systems. It enables full-string diagnosis, supports offshore operation, and offers reliable partial discharge detection and localization. In contrast, VLF, ACRT, and soak testing are limited either by equipment constraints or diagnostic capabilities and are less suitable for large-scale OWF projects.

7. Discussion

AC resonance testing (ACRT) voltage is acknowledged as the testing method that best represents breakdown voltage and partial discharge levels in cables under normal operating conditions.

However, its benefits are significantly compromised by the heavy, bulky units, which are impractical for offshore applications. Several testing methods have been proposed and well-studied as alternatives to on-site resonance AC voltage testing. The 24 h soak testing and the DC voltage testing are not the preferred testing methods nowadays due to their apparent drawbacks.

VLF and DAC are two popular methods, each with its own advantages and disadvantages in voltage withstand testing. To reveal weaknesses in the cable system that might not be detected during voltage withstand testing, additional diagnostics, such as dielectric losses and partial discharge measurements, are increasingly performed during on-site testing.

When it comes to voltage testing with partial discharge measurement (which is increasingly indispensable), DAC demonstrates its superiority because its measured PD parameters (PDIV, PD amplitude, etc.) are closer to those obtained under AC voltage testing. Along with its higher capabilities in testing long lengths of cable, DAC is the best solution for testing inter-array cables.

Therefore, some cable manufacturers recommend using a DAC for on-site testing of long cable systems as an alternative to the heavy and costly resonance AC voltage source. Regarding test parameters, they acknowledge [

28] as a compilation of industry experience on the subject and therefore recommend following its guidelines for site acceptance testing (SAT) and condition-based maintenance (CBM), as presented in

Table 18.

Moreover:

- (a)

If for VLF testing, frequencies will be considered between 0.1 and 0.01 Hz, the field stress should be limited to a maximum of 10 kV/mm or lower. Some industry standards recommend compensating for the lower testing field stress by increasing the testing time to 90 min or more.

- (b)

If any, the pass/fail criterion for PD testing should be independent of the chosen method (AC, VLF, or DAC). The recommendation is that there be no detectable PD at 1.5 Uo.

8. Conclusions

The discussion of this paper has been summarized in

Table 19 for export cables and in

Table 20 for inter-array cables. Summarizing the following conclusions can be made:

Analysis presented in this paper confirms that export and inter-array cables are the most critical components in terms of failure frequency and severity in offshore wind farms. Their technical characteristics, installation environment, and operational importance necessitate dedicated site acceptance testing (SAT) procedures to ensure long-term reliability and mitigate the high costs of repairs and downtime.

A comparative evaluation of available SAT methods shows that soak testing provides limited diagnostic information. In contrast, AC resonant testing faces significant practical constraints for long offshore cable systems, including export cables above 30 km and inter-array cables above 10 km.

Damped AC (DAC) testing has been demonstrated to be the most suitable SAT method for long export and inter-array cables. Its advantages include compact test equipment, low logistical requirements, and the ability to provide sensitive (see

Table 4), non-destructive diagnostics, including standardized partial discharge detection and localization along the full cable length. DAC is particularly effective for export cables longer than 30 km (typically 80–120 km) and inter-array strings exceeding approximately 20 km, where conventional methods are impractical.

However, where practical, the ARCT should not be abandoned, as it has proven its worth over a long history of applications in the land cable installations.