1. Introduction

DC circuit breakers (CBs) are widely used in HVDC and MVDC circuits where safety and reliability are key requirements. The absence of natural current zero-crossing in these circuits significantly increases the demands placed on switching equipment. Evolving legislation and standards for designers and manufacturers of fast CBs require the development of newer product solutions. Enhanced reliability is achieved through continuous improvement of CB designs and manufacturing technologies, as well as through the introduction of redundant operation standards to protect critical circuits.

Depending on the arc-extinguishing method used in CBs, it may be advisable to connect them in series, in parallel, or in a mixed configuration. For semiconductor-based switches, connecting multiple devices in series enables adaptation to higher-rated voltages [

1,

2]. Due to their availability, robustness, and switching speed, IGBT transistors are most commonly employed in such designs [

3,

4,

5,

6]. In [

7], a switch comprising three SiC ETO thyristors connected in parallel was developed and tested in a 4.5 kV/200 A circuit. In [

8], a hybrid switch design incorporating both IGBT transistors and IGCT thyristors in the turn-off stage was presented. Several hybrid switch variants are discussed in [

9,

10]. A mixed configuration was investigated in [

6], where two parallel branches were each composed of two series-connected IGBTs. The parallel operation of SF

6-based switches was analyzed in [

11], which focused on methods for predicting their behavior during interruption. Additionally, Ref. [

12] examined a concept in which a single commutation branch served multiple main circuits connected in parallel. The literature predominantly addresses multi-device configurations either for purely semiconductor-based switches or for auxiliary branches in hybrid systems.

The complexity, dimensions, and cost of a switch or its prototype depend on the application. Available solutions for hybrid fast CBs employing parallel, series, or mixed connections usually do not provide comprehensive information, particularly regarding design methodology and experimental validation.

This paper analyzes the performance of one of the more common hybrid DC CBs using the forced commutation method (FCM) [

13,

14,

15]. A parallel connection of this type of CB with another identical one, and with a conventional magnetic blow-out CB, was investigated. Previous studies only addressed isolated breaker operation, whereas the present work introduces and validates a coordinated parallel configuration of hybrid FCM-based DC breakers, identifying counter-current interaction limits, optimal commutation parameters, and experimental thresholds for non-intrusive sensor response. Each device was assumed to operate independently, necessitating the integration of two current sensors, one per breaker. This paper analyzes the GP counter-current circuit to investigate how inductance LK and capacitance CK affect the shape, duration, and amplitude of the counter-current half-wave. The study identifies the optimal resonant frequency for the GP to prevent the spontaneous opening of circuit breakers during parallel operation, specifically in forced-commutation systems.

2. Hybrid CB with the FCM

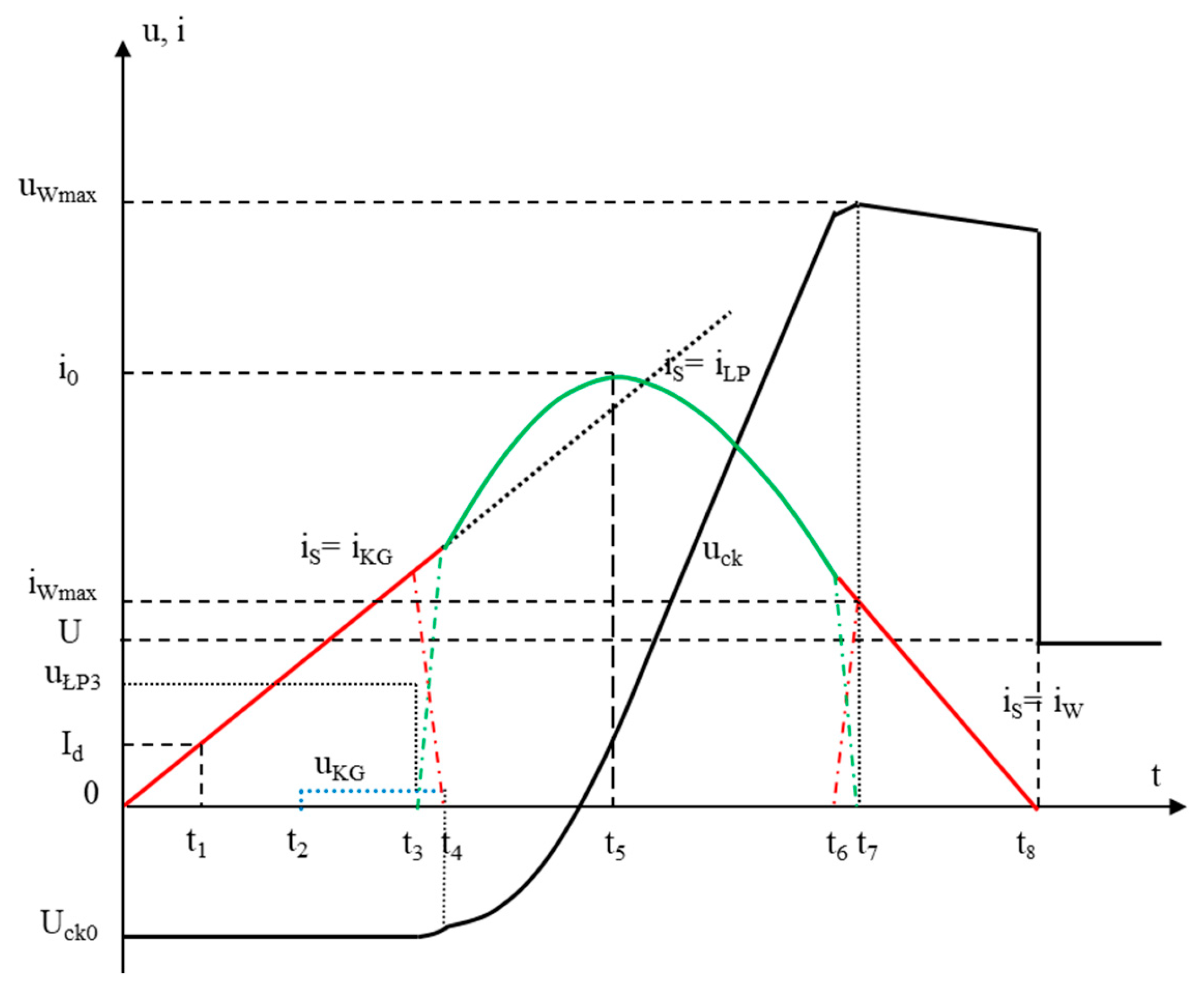

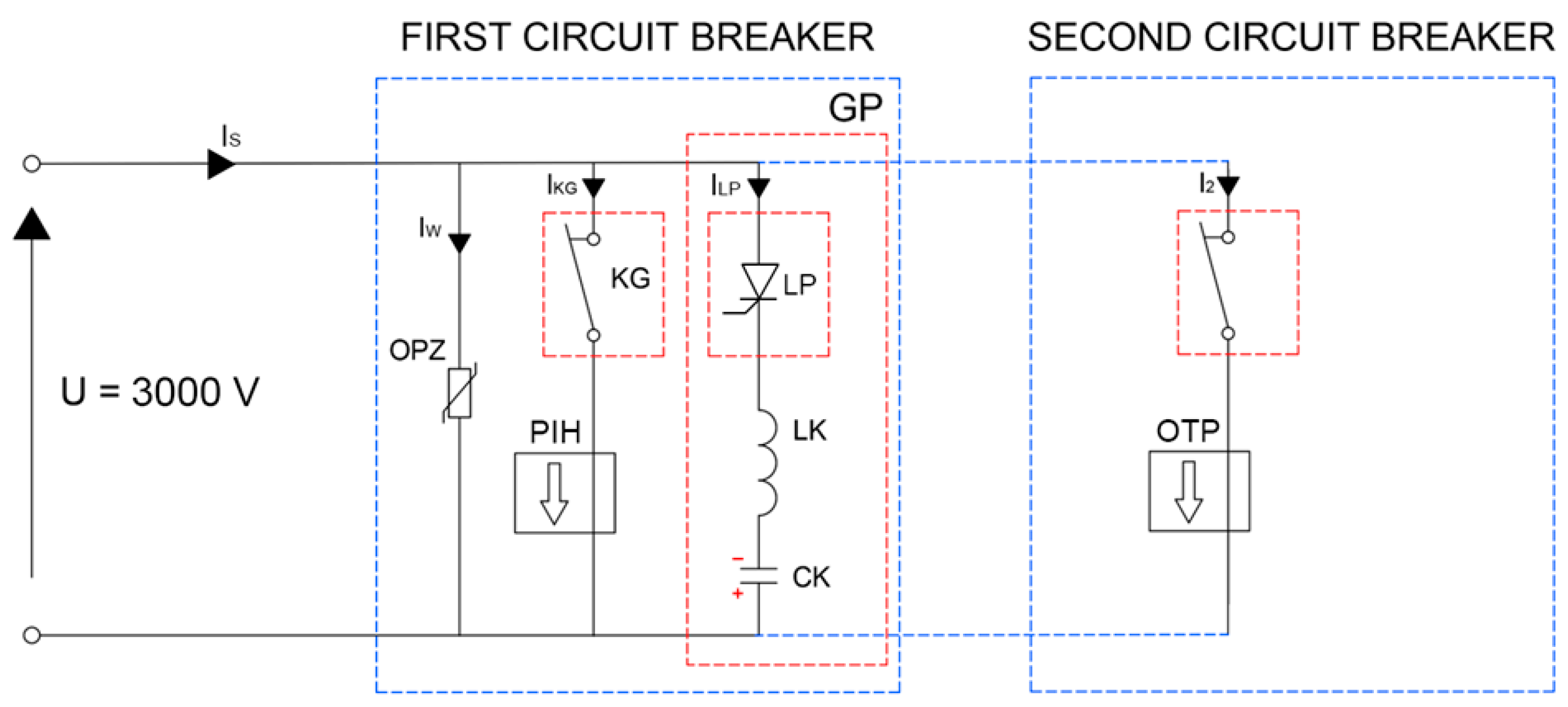

In DC systems, magnetic blow-out CBs are the type most commonly operated in parallel. A distinct group of DC CBs is represented by switches that employ the FCM, which is also referred to as counter-current (CC) switching. These are ultra-fast hybrid CBs, typically configured as vacuum-thyristor, vacuum-transistor, or all-vacuum designs. A general connection diagram of a vacuum-thyristor hybrid CB using FCM is shown in

Figure 1.

In FCM-based CBs, the interruption is achieved by generating an oppositely directed current pulse, referred to as the CC. Its source is a series-connected inductor LK and commutation capacitor CK. The CC circuit is activated by a semiconductor device LP, which, together with LK and CK, forms the CC generator GP. The switching unit KG, equipped with a vacuum interrupter, is responsible for closing and opening the main circuit. Proper synchronization of KG and LP is a necessary condition for correct CB operation.

Based on the circuit diagram in

Figure 1, the short-circuit current breaking is analyzed. The process of interrupting the short-circuit current is shown in

Figure 2. At the moment t

0, KG is closed and short-circuit current I

S = I

KG starts to flow. The supply voltage is assumed to be U = 3000 VDC.

At the moment t

1, when the PIH sensor detects the short-circuit current I

S, the KG opens, resulting in the appearance of arc voltage on its contacts at the moment t

2. Then, after a fixed time from the range (1 ÷ 4) ms, required to restore the recovery strength, at time t

3, the LP is closed, and the I

LP current begins to flow. In this case, Equations (1) and (2), describing the process of the first current commutation, are applicable:

At the moment t

4, when the I

KG current reaches zero, I

S is equal to the following (3):

The maximum short-circuit current that can be interrupted by the CBs is limited to the maximum value of the current I

LP generated by the GP. The current I

LP is equal to the following (4):

where U

k—capacitor voltage CK, ω

o—natural oscillation frequency of the circuit, α—dumping factor, and L

K—GP inductance.

After the CK has been recharged, to discharge the energy accumulated in the circuit at time t6, at voltage uWmax, the OPZ varistor is activated, which, after a certain time, ends the conduction of the LP at time t7. The OPZ itself switches off at the moment t8, which is also the end of the switching process.

For the CBs with the FCM, shown in

Figure 1, which can be used in the railway power supply in Poland, the expected short-circuit current is I

exp = (15 ÷ 45) kA, the time constant of the short-circuit circuit is τ = (15 ÷ 50) ms, and the maximum value of the current is I

LPmax = (10 ÷ 20) kA, and they depend on the GP parameters and the resistance of all connections.

3. Evaluation of Parallel Operation of Fast DC CBs

For fast CBs using FCM, the standards governing parallel operation are not straightforward. Although this configuration can improve overall system reliability, it does not eliminate all risks. In parallel operation, the main current splits into two branches. If the circuit breakers must remain modular and operate independently, each CB requires an individual current sensor, in this case, a PIH sensor. As a result, the total current will be doubled, exceeding the threshold at which an automatic interruption sequence is initiated. To limit the negative thermal effects resulting from the flow of this current through the circuit, the current tripping value must be reduced. Another consideration involves the effects of closing and opening FCM-based CBs during parallel operation. In particular, attention must be given to the influence of the generated CC on the behavior of a CB connected in parallel, especially with respect to its current sensor response.

For this purpose, parallel operation was analyzed in two variants:

Parallel operation of the FCM-based CB and the magnetic blow-out CB (

Figure 3).

Parallel operation of two identical FCM-based CBs (

Figure 4).

For both variants, the supply voltages of U = 3000 VDC and IS = 1000 A were assumed. In the initial state, regardless of the variant, both CBs are closed, and their tripping current is set to Id = 1500 A.

3.1. Parallel Operation of the CB Using the FCM and a Magnetic Blow-Out CB

The diagram for the circuit under consideration is shown in

Figure 3. It allows two different circuit-breaking methods to be combined, utilizing the advantages of both.

When the first CB is forced to trip, a current ILP will be generated, the value of which will be proportional to the short-circuit current IS. The second circuit breaker remains closed. In this case, IS is equal to the following (5):

Since these CBs operate in parallel, opening one of them causes the current I

KG to be taken over by the closed second CB. Hence, the current flowing is described by the following Equation (6):

If we conduct the same test, but for a short-circuit current limited to 10 kA flowing through the circuit in

Figure 3, the I

LP will not exceed the following:

In this case, due to the time required for CBs using the FCM to break the short circuit, the CB with magnetic blow-out should not trip automatically. However, this will depend on the time of occurrence t

LP of the I

LP in the main circuit and the time required for the t

OTP magnetic blow-out CBs to detect the short circuit. The relationship between these times should be as follows:

3.2. Parallel Operation of Two CBs Using the FCM

The schematic diagram for the circuit under consideration is shown in

Figure 4.

At the moment of turn-off of the first CB, the I

LP will be generated, the value of which will be proportional to the current I

S. In this case, I

S is equal to the following (9):

The current of the main branch I

KG, as in variant one, is taken over by the closed second CB. The current described by the equation flows in the circuit. Hence, we have the following:

For an I

S limited to 10 kA flowing through the circuit in

Figure 4, the I

LP will not exceed the following:

In this case, the PIH2 current sensor of the second CB will detect the ILPmax generated by the first CB, even during normal switching operations, especially during non-current opening. Both CBs belong to the group of ultra-fast CBs, and hence, their PIH current sensors are extremely sensitive. Since the CBs are assumed to operate independently, the second CB will treat the ILPmax as a short circuit and initiate the breaking procedure. This will cause both CBs to open, even though there is no actual short circuit in the circuit. This situation is unacceptable during the operation of traction vehicles, and one solution is to use current sensors that can detect and transmit information about the type of current flowing: rated, short-circuit, or counter-current of the second CB. To determine the basis for the design of this type of current sensor, it is necessary to have knowledge of the formation of ILP and the influence of switching circuit parameters on the breaking capacity. For this purpose, simulation tests were conducted, the results of which are shown in the next chapter.

4. Analysis of GP Circuit Parameters

4.1. The Influence of the GP Frequency

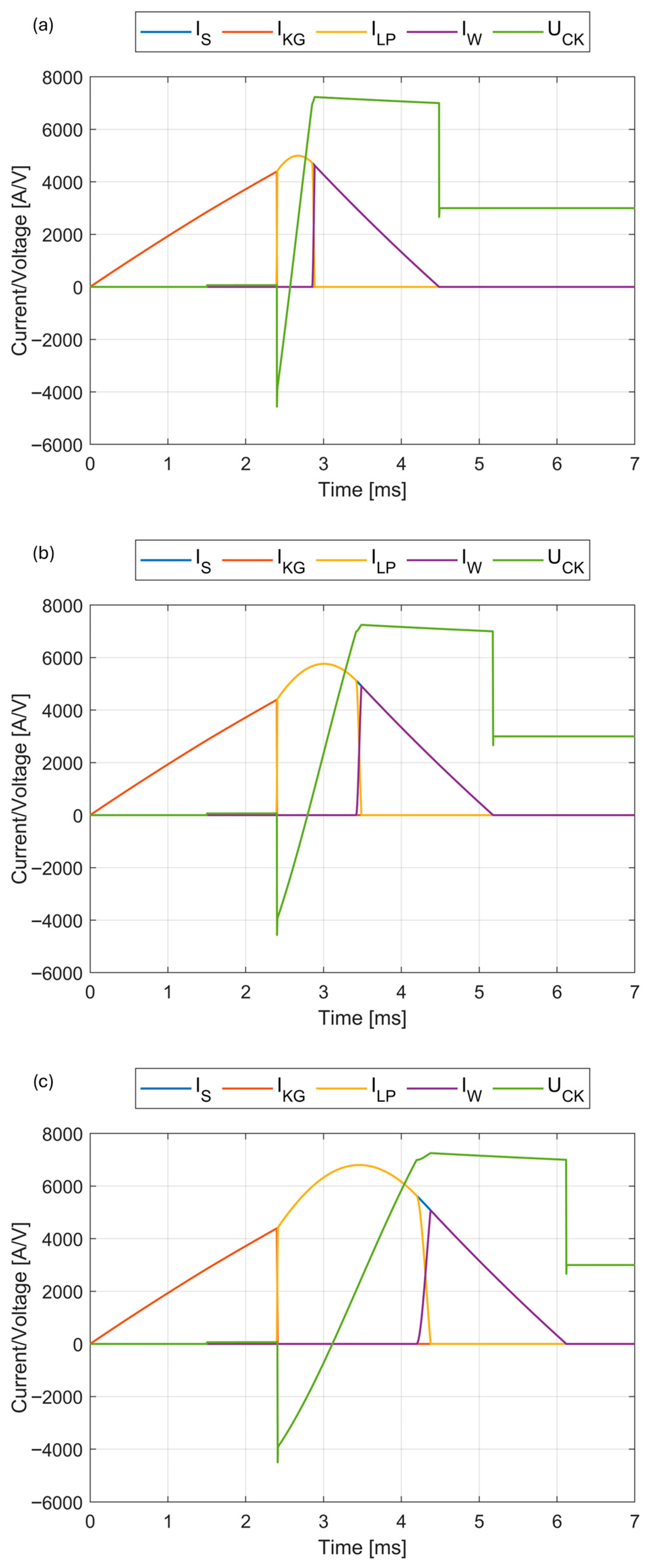

The primary objective of the research was to determine the possibility of parallel operation of hybrid CBs and to identify any negative phenomena that may occur in such cooperation. If the GP is used to supply additional energy, it is necessary to determine how its parameters affect the braking process.

To perform such an analysis, it is necessary to understand the waveforms during short-circuit breaking. For this purpose, a model of this type of device was created in Matlab Simulink 2024b software, and then its operation was assessed for selected GP parameters. Three frequencies f were assumed, (1.6; 5; 10) kHz, for which the CK and LK values were selected to shape the I

LP, as shown in

Table 1.

The breaking process was tested in a 3 kV DC circuit for a short circuit with a τ = 15 ms and an expected short-circuit current of Iexp = 30 kA. Hence, the short-circuit current rate is 2 A/µs.

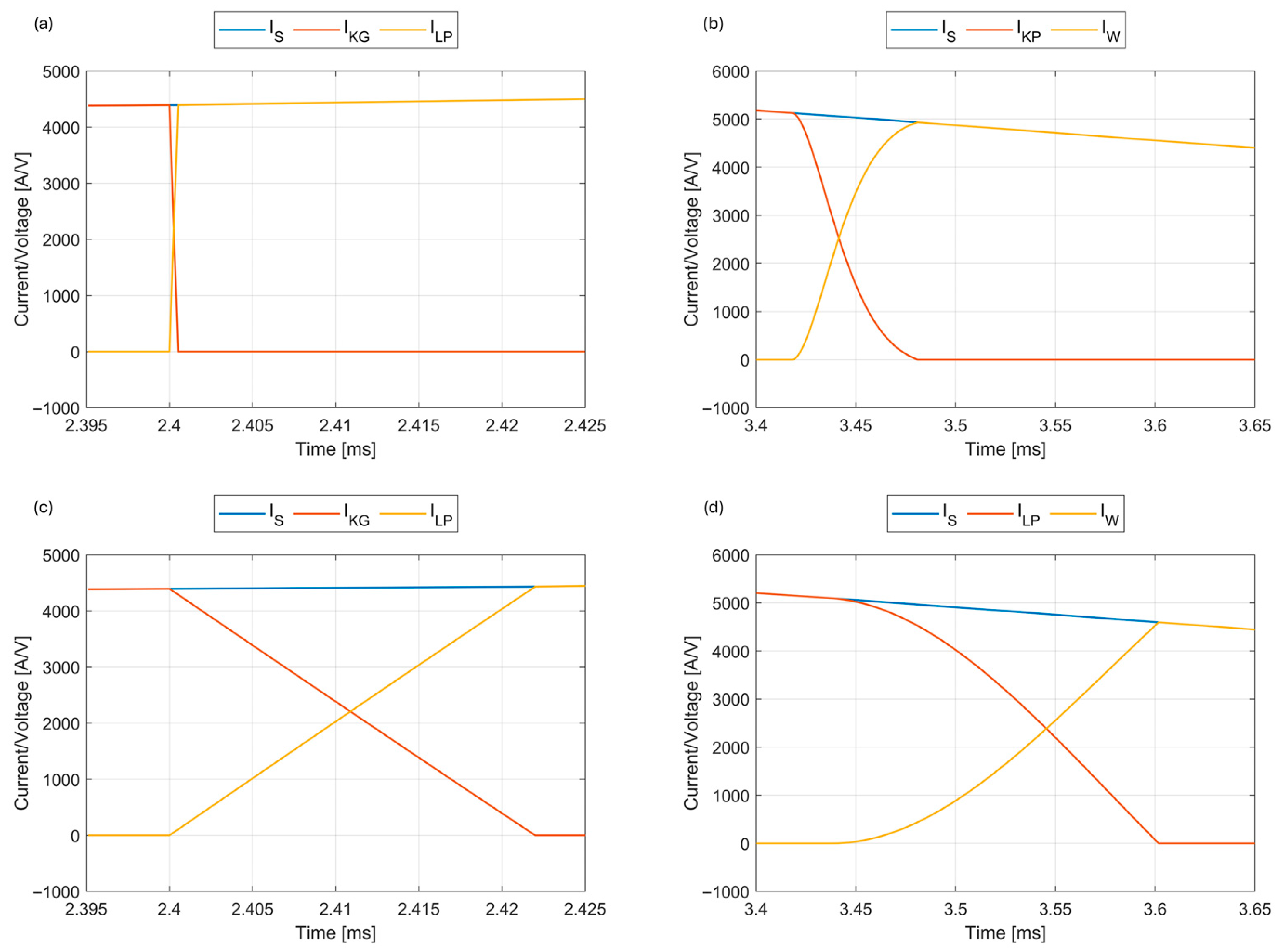

The simulations were divided into two groups, A and B. In sample A, the frequency was reduced by increasing both the inductance of the LK and the capacitance of the CK. Then, the effect of changing the parameter of only one element on the behavior of the GP during short-circuit breaking was checked. The waveforms obtained for cases A1 ÷ A3 are shown in

Figure 5.

The obtained waveforms indicate that each of the CB variants was able to switch off a short circuit characterized by τ = 15 ms and I

exp = 30 kA. Comparing the results with each other, the GP conduction times are different and equal to approximately 500 µs, 1 ms, and 2 ms. The current amplitude I

0 in this circuit was (5; 5,8; 6.8) kA. This means that for a f = 1.6 kHz, the greatest safety margin and the ability to disconnect a short-circuit current with a higher initial rate were obtained. However, the higher amplitude of current requires more energy to be stored in the CK. Considering the operation of the OPZ (

Figure 1), an increase in f causes a slight increase in its conduction time, which is caused only by the extension of the current commutation time from the GP. However, the amount of energy dissipated on the OPZ changes significantly, reaching 26 kJ at f = 10.2 kHz and 33.5 kJ at f = 1.6 kHz. From the point of view of the OPZ reliability, the CB variant with the GP with a higher frequency is more advantageous.

4.2. The Influence of GP Inductance

In the second variant B (

Table 1), the waveforms for three frequencies, f = (1.6; 5; 10) kHz, were checked, but this time the capacitance of the CK and the voltage U

ck were constant, and the value of the LK was changed within the range LK = (0.48; 2; 20) µH. This allowed the above-mentioned frequency values to be determined. The GP parameters assumed for this part of the study are shown in

Table 1, part B, and the waveforms obtained are shown in

Figure 6. The waveform for CK = 500 µF, LK = 2 µH is shown in

Figure 5b.

The most noticeable changes are in the rate of current takeover in the KG–GP and GP–OPZ circuits, which are shown in

Figure 7.

With inductance Lk = 0.48 µH, the current rate when the GP turns on is 8500 A/µs and can be achieved by using a mechanical device. Increasing this inductance more than 40 times reduces this slope by the same ratio, because for Lk = 20 µH, a slope of 197 A/µs was obtained. Considered further, in the case of the Lk = 0.48 µH, the current rising rate during the second current commutation from GP to OPZ is 83 A/µs and decreases to 32 A/µs for variant B3. In addition, lower current rates result in a reduction of the maximum current value in the OPZ, which means that the energy dissipated is equal to 27 kJ (for Lk = 20 µH) and decreases for Lk = 0.48 µH, where it is equal to 31 kJ, with the same conduction time.

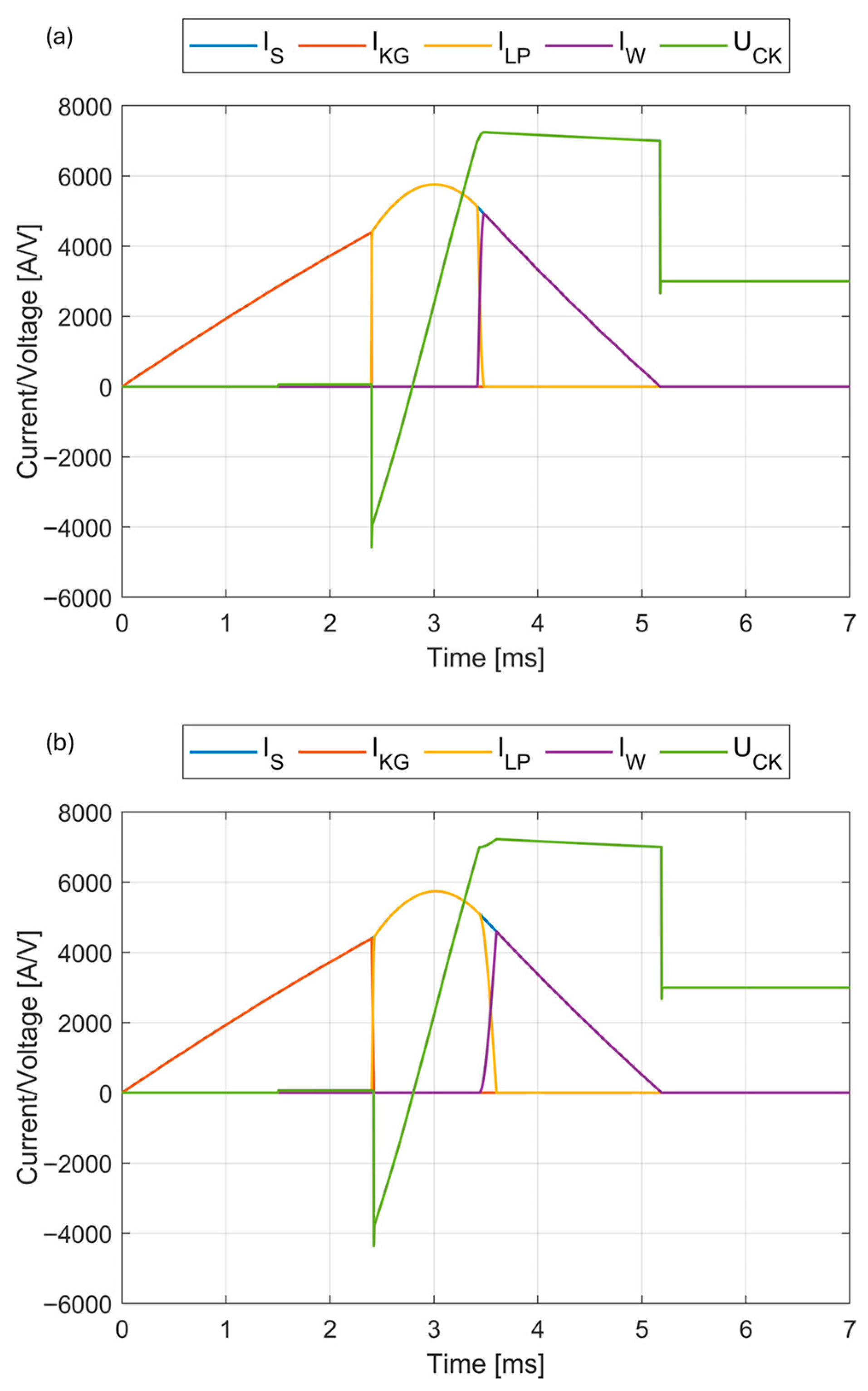

4.3. The Effect of ILP on the PIH Sensor

In the case of a non-current opening of the CB with FCM connected in parallel with another CB that is in the closed state, the ILP pulse by the GP will be generated. Its amplitude and duration will depend on the parameters of the GP, but above all on the parallel circuit parameters, in which the resistance of the connections and the contact resistance of the second CB, as well as the resistance and inductance of the cables, must be taken into account. In this way, an equivalent circuit will be created, shorting the GP, composed of the resistance Rp and inductance Lp.

To assess the impact of parameters R

p and L

p, simulations were performed using variants A1 to A3 (

Table 1) as the basic CB. At this stage, the type of the second CB is irrelevant, even though the inductance of the DC CB with magnetic blow-out coil, which is approximately (5 ÷ 15) µH, will contribute significantly to the total inductance of the circuit under consideration. The calculations were performed for three variants, D1 ÷ D3, and the assumed values are shown in

Table 2.

The counter-current waveforms obtained for the three basic CB A1 ÷ A3 connected in parallel with circuits D1 ÷ D3 are shown in

Figure 8a–c.

An increase in the resistance and inductance of the shorting circuit (

Table 2) of the CB under consideration reduces the amplitude of the I

LP, while extending its duration. The highest amplitude was recorded for the CB equipped with a GP operating at frequency f = 1.6 kHz, reaching slightly over 25 kA with a duration of 4.6 ms. When L

p and R

p of the parallel circuit were increased, the amplitude decreased to 16 kA, whereas the duration of I

LP increased to 6.7 ms. As shown in the waveforms in

Figure 8, duration is comparable to, or exceeds, the total short-circuit breaking time.

For the CB with a GP frequency of f = 10.2 kHz, ILP reaches approximately 15 kA with a duration of only 1.6 ms for case D1. After increasing Rp and Lp, the amplitude dropped below 10 kA and the duration extended to 3 ms.

The results obtained indicate that each CB configuration provides sufficient protection for the load. However, the influence of each GP circuit on the other breaker during non-current opening varies significantly. Therefore, understanding these relationships is essential when designing FCM-based CBs intended for later independent parallel operation, enabling designers to implement such configurations without complications.

5. Experimental Validation

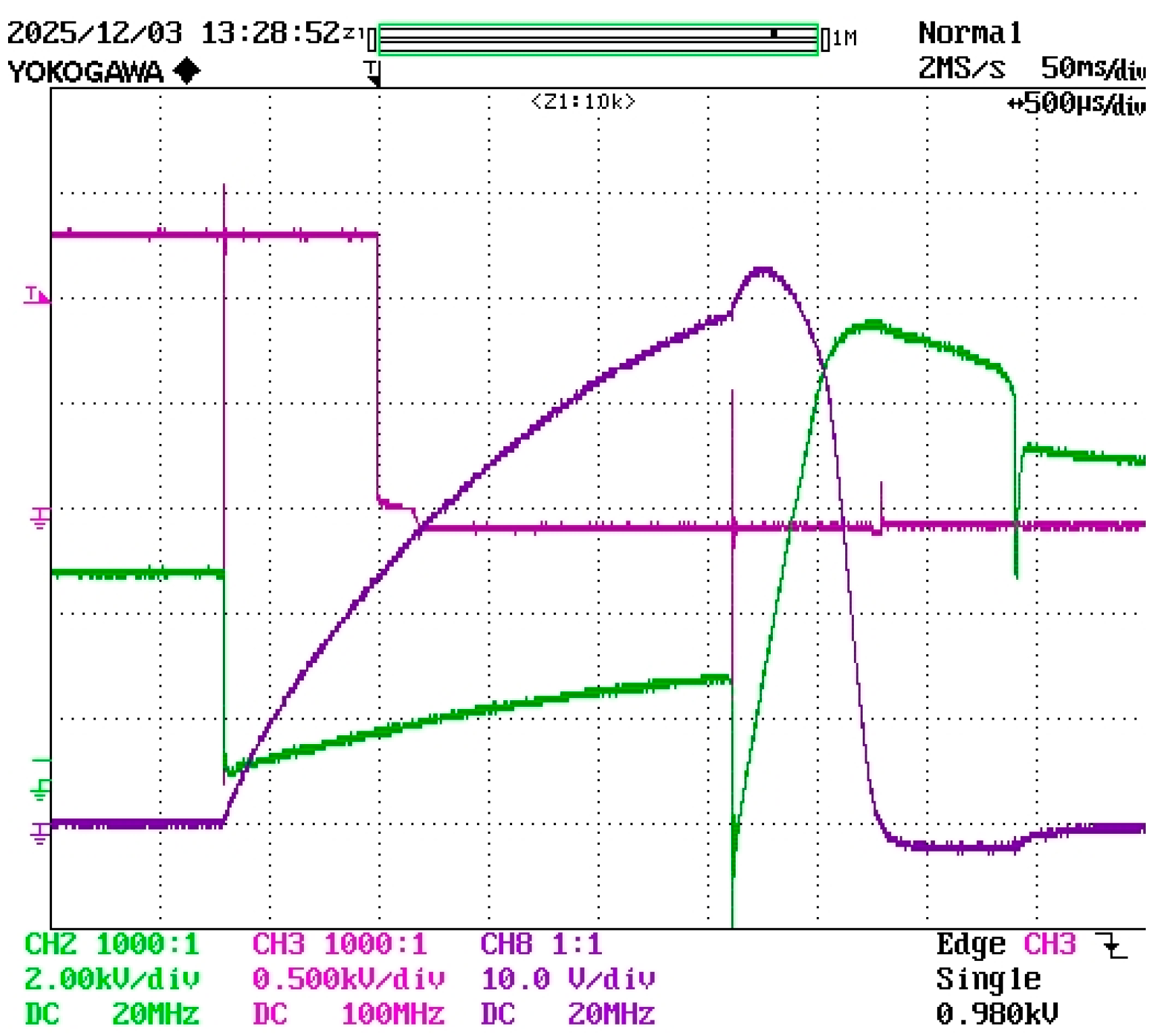

To confirm the correctness of the simulated interruption waveforms, an experimental test stand was developed in accordance with the procedures and performance criteria specified in standard [

17]. The laboratory setup reproduced the operating conditions of the FCM-based CB, including a 3.9 kV DC source, and a load configuration enabling the achievement of a prospective fault current of I

exp = 45 kA with a time constant τ = 15 ms. The captured waveforms are presented in

Figure 9. These short-circuit parameters represent the current rise rate of approximately 3 A/µs.

The FCM-based CB was subjected to a controlled rise in fault current up to the prospective value. Interruption occurred within approximately 2.5 ms, with short-circuit current effectively reduced from 45 kA to 5 kA. The overvoltage measured on the OPZ reached 9.1 kV.

The results confirmed that the FCM-based CB is capable of breaking the shortened circuits and reducing the prospective short-circuit current. Further enhancement of its performance is possible by improving the KG drive, thereby increasing its speed and reducing reaction time.

6. Discussion

This paper demonstrates the capability of limiting the expected short-circuit current by employing a hybrid FCM-based CB for DC circuit interruption. The feasibility of coordination between this breaker and two additional devices, a second FCM-based CB and a conventional magnetic blow-out CB, was examined. The objective of such coordination was to enhance the flexibility and applicability of the proposed design across a wider range of system configurations.

It was observed that, in this mode of cooperation, the generated ILP half-wave closes through the current path of the second CB, which may result in unintended and undesired tripping. It was shown that coordination with a magnetic blow-out CB is feasible, provided that the duration of the ILP current tLP remains shorter than the current sensor over-threshold protection response time tOTP.

In the case of parallel operation of two identical FCM-based CBs, the likelihood of unintended tripping increases, since the closed breaker interprets the ILPmax pulse as a fault current. Therefore, the paper identifies the influence of individual GP components on the amplitude and duration of ILP. It has been demonstrated that selecting a GP operating at f = 10.2 kHz is advantageous in terms of coordination between FCM-based CBs, both when paired with an identical breaker and when operating alongside a magnetic blow-out CB. An additional benefit of this configuration is the improved operating conditions of the OPZ varistor.

As shown in

Table 3, the FCM-based CB combines the fast interruption characteristics typically associated with fully semiconductor-based solutions with the low thermal stress and negligible contact erosion of vacuum technology. In contrast, the magnetic blow-out CB exhibits the longest total interruption time and the highest arc energy, which directly translates into elevated maintenance requirements and reduced environmental neutrality due to plasma emission. The NCM-based CB matches the FCM solution in speed but demonstrates significantly higher susceptibility to overvoltage, making it less suitable for parallel coordination in DC systems with steep di/dt ratios.

7. Conclusions

For reliable parallel coordination, the CC generator should operate in the frequency range of (8 ÷ 12) kHz. This configuration prevents undesired tripping during CC flow while maintaining the breaking capability and reduces the prospective fault current from 45 kA to 5 kA within approximately 2 ms.

The obtained results confirm that the hybrid FCM-based CB provides effective limitation of short-circuit current while ensuring compatibility with both a conventional magnetic blow-out CB and an identical FCM-based unit, enabling practical application in modular and parallel DC protection architectures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ł.N. and M.R.; methodology, Ł.N. and M.R.; software, M.R.; validation, Ł.N., P.B. and M.R.; formal analysis, Ł.N.; investigation, M.R.; resources, M.R.; data curation, P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Ł.N. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, Ł.N. and M.R.; visualization, Ł.N. and M.R.; supervision, P.B.; project administration, Ł.N.; funding acquisition, P.B., Ł.N. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CB | Circuit-breaker |

| FCM | Forced commutation method |

| CC | Counter-current |

References

- Feng, L.; Gou, R.; Zhuo, F.; Yang, X.; Zhang, F. Development of a 10kV solid-state DC circuit breaker based on press-pack IGBT for VSC-HVDC system. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 8th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC-ECCE Asia), Hefei, China, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 2371–2377. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.S.; Kang, H.W.; Rhee, J.H.; Lee, K.A. Hybrid Z-Source Circuit Breaker with Thomson Coil for MVDC. Energies 2024, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempkes, M.; Roth, I.; Gaudreau, M. Solid-state circuit breakers for medium voltage DC power. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Electric Ship Technologies Symposium, Alexandria, VA, USA, 10–13 April 2011; pp. 254–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Ming, W.; Ugalde-Loo, C.E.; Liang, J. A Low-Loss Integrated Circuit Breaker for HVDC Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.A.; Lee, J.-G.; Amir, F.; Lee, B.-W. A Novel Model of HVDC Hybrid-Type Superconducting Circuit Breaker and Its Performance Analysis for Limiting and Breaking DC Fault Currents. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015, 25, 5603009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Pei, X.; Niu, L.; Feehally, T.; Wilson, P.; Gu, C.; Zeng, X. A solid-state circuit breaker for DC system using series and parallel connected IGBTs. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 139, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Woodley, R.; Song, X.; Sen, S.; Zhao, X.; Huang, A.Q. High current medium voltage solid state circuit breaker using paralleled 15 kV SiC ETO. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 4–8 March 2018; pp. 1706–1709. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Chen, Z.; Lv, G.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, R. A Novel Mixture Solid-State Switch Based on IGCT With High Capacity and IGBT with High Turn-off Ability for Hybrid DC Breakers. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 4485–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Demetriades, G.D. A Survey on Hybrid Circuit-Breaker Topologies. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2015, 30, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Wheeler, P.; Castellazzi, A.; Watson, A.J.; Effah, F. Semiconductor Devices in Solid-State/Hybrid Circuit Breakers: Current Status and Future Trends. Energies 2017, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiermeier, H.; Raysaha, R.B. Evolving Fault and Parallel Switching for SF6 Circuit Breakers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 35, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Yin, J.; Wei, T.; Li, J.; Zhu, J.; Ye, Z. A New Design of MP-HDCCB Topology Based on Hybrid Switching Device. Energies 2022, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, P.; Rodak, M.; Sienicki, A.; Panev, B.; Mateos, F.; Siemko, A. Ultrafast, Redundant, and Unpolarized DC Energy Extraction Systems for the Protection of Superconducting Magnet Circuits. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 9895–9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Ł.; Borkowski, P. Development and application of PIKH type current sensors to prevent improper opening of parallel connected DC vacuum circuit breakers. Energies 2024, 17, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Ł.; Borkowski, P.; Rojek, A. The influence of the design and method of short-circuit current measurement on the possibility of parallel operation of high-speed circuit breakers. Arch. Electr. Eng. 2025, 74, 827–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, F. Ultraszybkie Wyłączanie Silnoprądowych Obwodów Prądu Stałego. Habilitation Thesis, Politechnika Łódzka, Łódź, Poland, 2010. Volume 396. [Google Scholar]

- PN-EN 60077-1:2018; Railway Applications: Electric Equipment for Rolling Stock—Part 1: General Service Conditions and General Rules. Polish Committee for Standardization (PKN): Warsaw, Poland, 2018.

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).