1. Introduction

With the rapid development of industrialization, climate change has become increasingly severe, and carbon emission control has been recognized as a critical global task [

1]. On 24 September 2025, President Xi Jinping announced China’s new Nationally Determined Contributions, aiming to reduce the net greenhouse gas emissions by 7% to 10% from peak levels by 2035, with efforts to achieve even greater reductions [

2]. To meet this goal, a transition is required from a traditional energy structure dominated by fossil fuels to a new green energy system based largely on renewable sources such as wind and solar power [

3].

However, the intermittency and volatility inherent in renewable energy sources have introduced significant operational risks, thereby posing formidable challenges to the secure and stable operation of current power systems. Specifically, traditional power generation units are not only required to enhance their regulation capabilities, but the large-scale integration of renewable energy also induces fluctuations in grid frequency and voltage. This necessitates the power system to possess the capacity for rapid and wide-range adjustments as well as frequent start-stop operations [

4]. Against this backdrop, the flexibility retrofit of conventional thermal power units—recognized as the backbone of China’s energy supply system—has emerged as an indispensable strategic measure [

5].

Current flexibility retrofit technologies for thermal power units can be primarily categorized into two types. The first type involves modifications to unit components, such as the low-pressure cylinder zero-output retrofit [

6] and high back-pressure retrofit [

7]. The second type entails the integration of thermal-electric decoupling devices, including batteries, electric boilers, and hot water storage tanks [

8]. The integration of energy storage technology with coal-fired power plants has been widely recognized as an effective solution to enhance the plant’s flexibility. However, not all energy storage technologies are suitable for integrating with coal-fired power plants [

9]. For example, pumped hydro storage is subject to geographical constraints [

10] and the efficiency, economic performance and stability of compressed gas energy storage systems [

11,

12,

13] remain to be verified in practical applications.

The high investment costs and unsolved safety issues act as barriers to the large-scale deployment of electrochemical and chemical energy storage technologies [

14]. Compared with the mentioned technologies, TES is an economically efficient option to improve the flexibility of coal-fired power plants [

15].

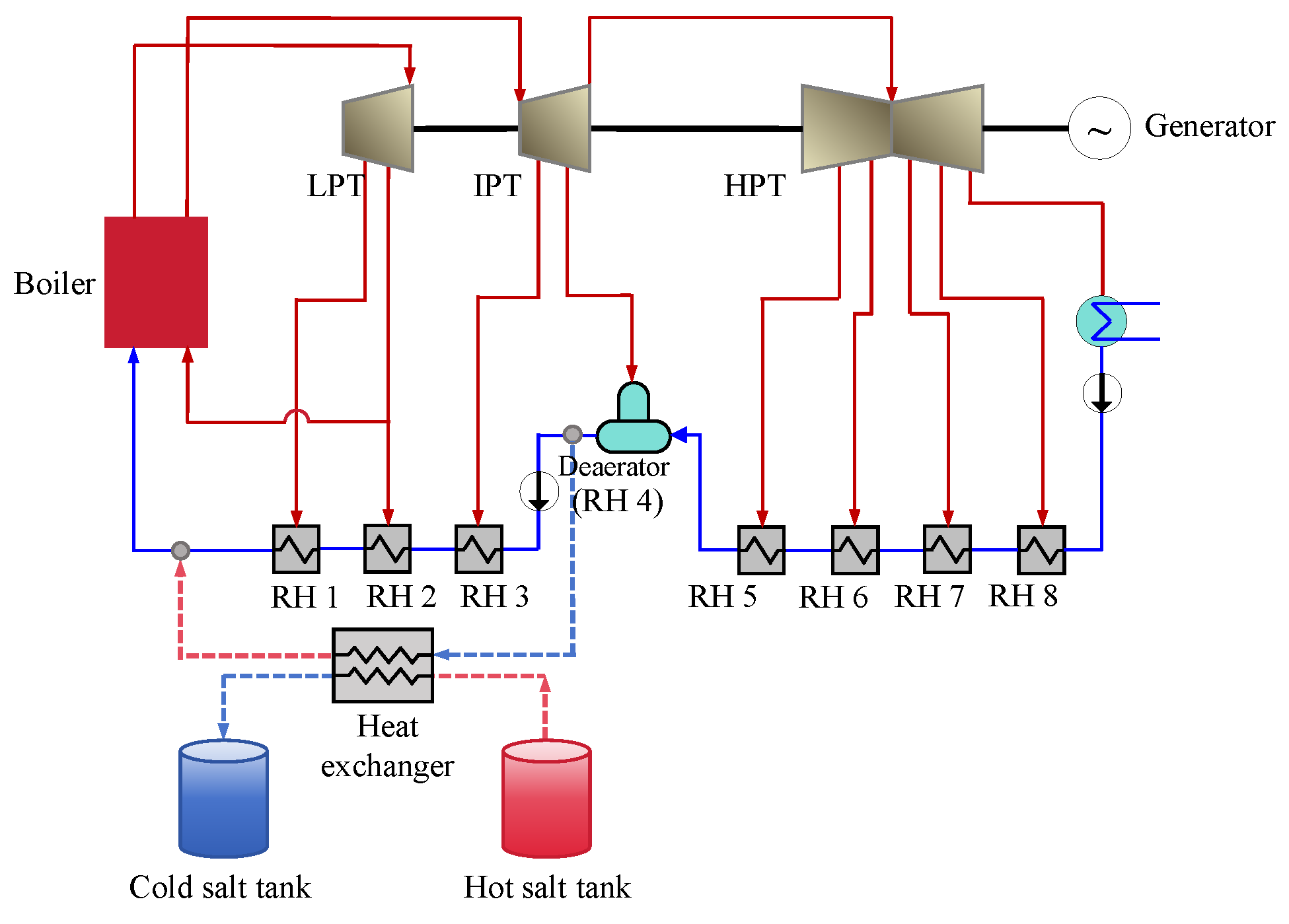

The operating temperatures of commonly used TES technologies is presented in

Table 1. Among different thermal storage media, molten salt is outstanding because of its high heat capacity, low cost and compatibility with operating temperature ranges. It is regarded as a feasible option to enhance the flexibility of coal-fired power plants.

Historically, molten salt has been predominantly applied in concentrated solar power (CSP) systems [

16]. Recent studies have demonstrated that molten salt exhibits high heat exchange efficiency with steam and excellent operational flexibility, endowing it with high compatibility with thermal power units. Consequently, extensive research efforts have been devoted to investigating the integration of molten salt thermal energy storage systems with thermal power plants. For example, Luo et al. [

17] developed a molten salt TES coupled system for a 300 MW subcritical unit and conducted in-depth research on key equipment selection and operational strategies. Li et al. [

18] optimized the thermal performance of a system coupled with molten salt TES by examining variations in key parameters such as main steam pressure and high-pressure feedwater temperature. Miao et al. [

19] and Wang et al. [

20] established systems incorporating electric heating and steam extraction for molten salt storage, performing exergy analysis and peak-shaving assessments. Zhang et al. [

21] proposed a scheme using high-temperature flue gas and superheated steam to jointly heat molten salt, effectively avoiding pinch point temperature limitations and reducing irreversible heat transfer losses, thereby validating the improvement in unit ramp rate.

In addition to theoretical studies, pioneering demonstration projects have also been developed in recent years [

22]. For instance, a molten salt TES system was integrated into a 600 MW subcritical coal-fired power plant in Longshan to enhance its operational flexibility [

23]. Nevertheless, several practical challenges remain unresolved. Currently, multiple charging and discharging schemes are available for molten salt TES systems, and the optimal configuration tends to vary with the type of molten salt employed. Furthermore, no comprehensive study has systematically compared the round-trip efficiency of different integrated power generation systems. To address this research gap, this study selects a 660 MW ultra-supercritical coal-fired unit as the research object. A thermodynamic model incorporating a molten salt TES unit is established using the THERMOFLEX 31 platform. While existing studies [

24,

25,

26] typically examine charging and discharging processes of the molten salt TES separately, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of their charging-discharging strategy combinations. This study aims to provide theoretical support and engineering references for the flexibility retrofitting of coal-fired power units.

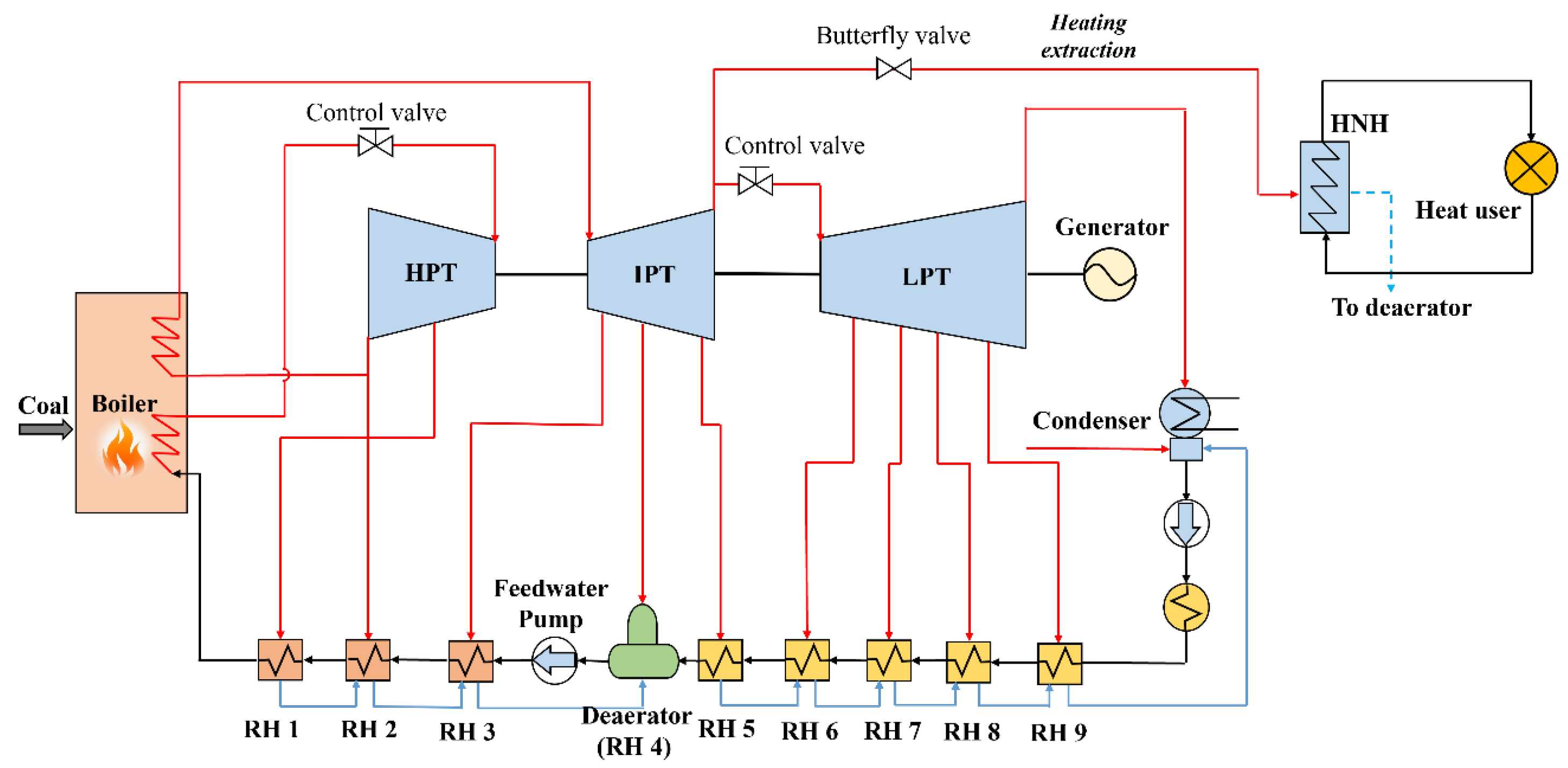

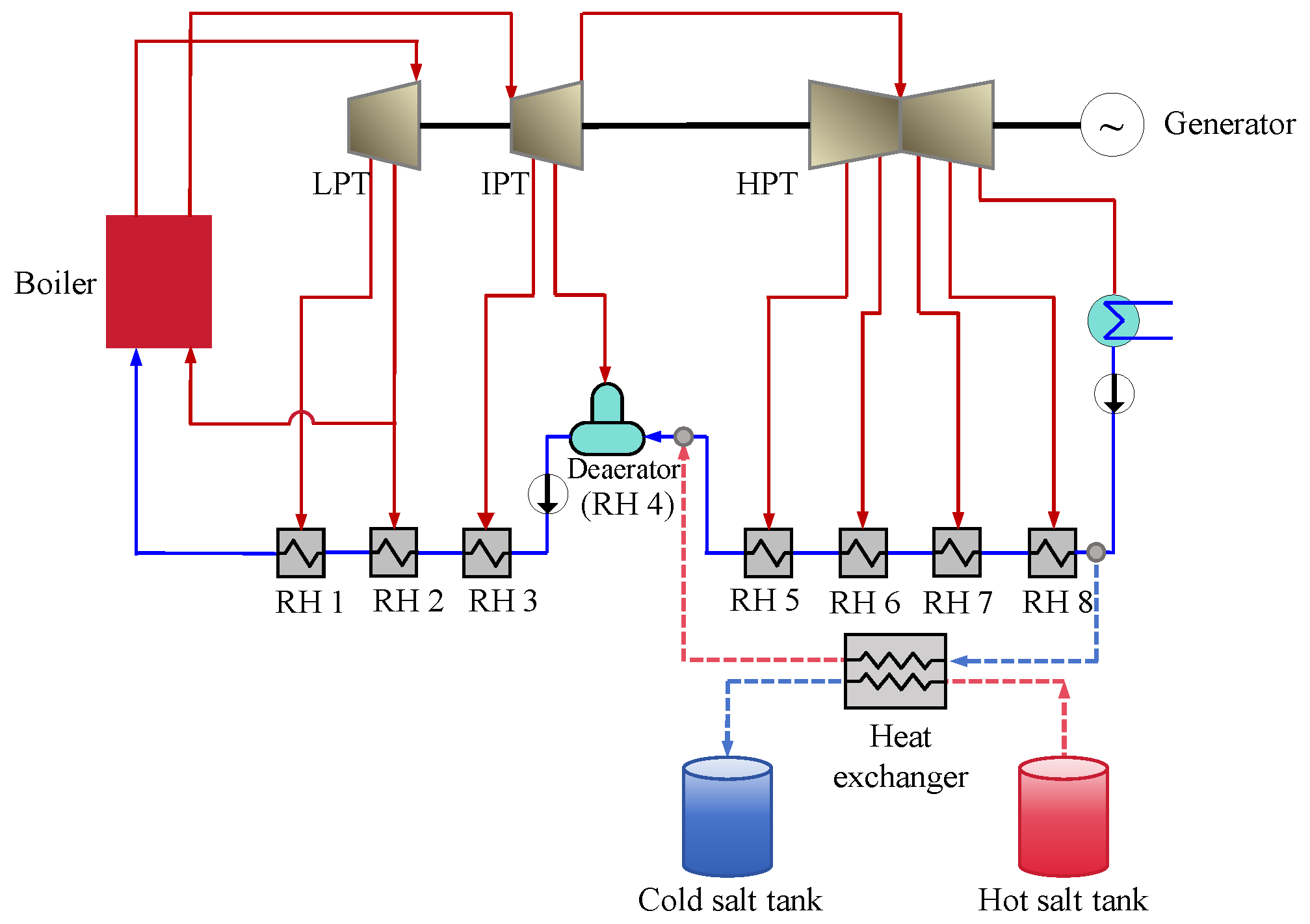

3. Multiple Integration Schemes for Molten Salt Thermal Energy Storage Systems, System Overview

3.1. System Description

The integration of a molten salt thermal energy storage (TES) system with thermal power units is primarily realized through three technical pathways: electric heating, steam extraction heating, and waste heat recovery. However, waste heat recovery is rarely employed in practical engineering applications, mainly due to the relatively low temperature of waste heat sources. This low-temperature characteristic leads to inferior energy density, necessitates a large-scale system configuration, and results in limited energy utilization efficiency. Consequently, this study focuses on the two technically feasible pathways, namely steam extraction heating and electric heating.

All schemes were analyzed under the peak-shaving boundary condition of 30% minimum stable combustion load of the boiler. During the discharging process at 50% THA, 75% THA, and 100% THA, the thermal energy stored in high-temperature molten salt was utilized to heat the feedwater or condensate within the turbine system. This heating process not only effectively improves the thermal cycle efficiency of the unit and enhances its power generation capacity but also enables additional power output, thereby facilitating peak-shaving operations.

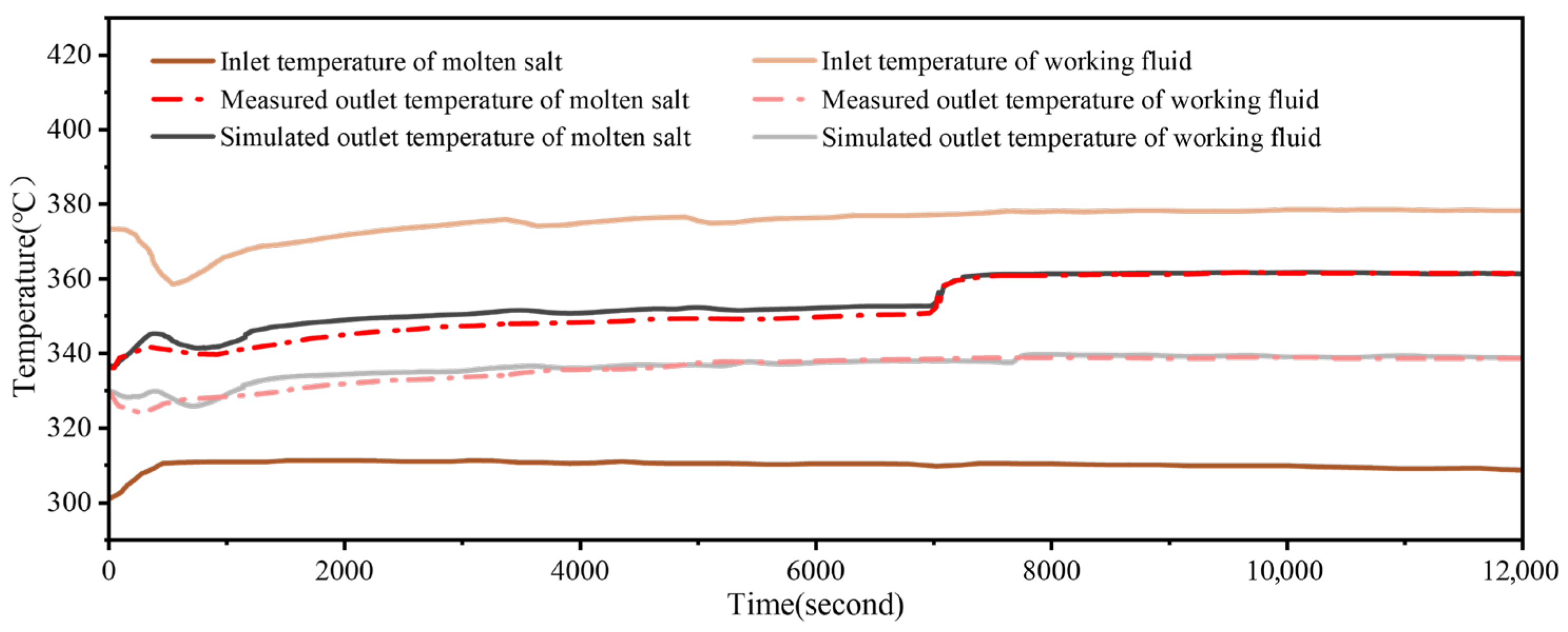

The implementation of this technical approach is favored by the advantages of ternary molten salt, including a wide operating temperature range, excellent thermal stability, and favorable economic performance. Thus, ternary molten salt was selected as the storage medium in this study, and its thermophysical properties are listed in

Table 4. Based on these inherent characteristics, four representative charging schemes and four discharging schemes were designed.

It should be noted that the ternary molten salt system undergoes slight thermal decomposition when the temperature exceeds 427 °C and is prone to solidification at excessively low temperatures, which may lead to flow blockage. To avoid these potential issues, the operating temperature of the high-temperature molten salt tank was set at 390 °C, while that of the low-temperature tank was maintained at 190 °C. During the system modeling process, pipeline pressure drops, resistance losses, and heat dissipation effects on thermal performance were not taken into account.

3.2. Thermal Storage Schemes and Thermodynamic Calculation

To more accurately determine the optimal steam extraction location for molten salt heating, the power output difference before and after thermal storage was fixed at 30 MW for all schemes, and the molten salt flow rate was uniformly set to 600 t/h. The integrated systems corresponding to the four thermal storage schemes under the 30% THA condition are illustrated in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, with the specific processes described as follows:

(1) Scheme C1

Under 30% THA conditions, the molten salt heating process in this scheme involves three stages. First, 150 t/h of main steam (6.40 MPa, 600 °C) is extracted within safe operational limits of the boiler and turbine. The steam is cooled to 450 °C using cooling water, and then exchanges heat with molten salt in Heat Exchanger 1. Here, 625.8 t/h of molten salt is heated from 273.5 °C to 370.1 °C.

The cooled steam is then split into two streams. One stream, comprising 130 t/h of steam at 1.85 MPa and 208.4 °C, is mixed with the cold reheat steam (1.83 MPa, 413 °C, 339.3 t/h) and returned to the turbine for work production. The other stream (39.8 t/h, 6.38 MPa, 279.6 °C) undergoes a second heat exchange with molten salt in the condenser, where latent heat is utilized to heat the molten salt from 206.9 °C to 273.5 °C. The steam is condensed into water (6.28 MPa, 278.5 °C, 39.8 t/h).

Finally, the condensate water and molten salt undergo a third heat exchange in Heat Exchanger 2. The molten salt is heated from 190 °C to 206.9 °C. The heated condensate water is pressurized and cooled to form high-pressure condensate (6.26 MPa, 195 °C, 39.8 t/h), which is fed into the turbine’s high-pressure feedwater system via Heater 3.

(2) Scheme C2

Under 30% THA conditions, 150 t/h of reheat steam (1.50 MPa, 580 °C) is first extracted. This steam is desuperheated and depressurized using high-pressure condensate from the pump after the deaerator, resulting in 220.6 t/h of modified steam (1.50 MPa, 450 °C). This steam then exchanges heat with 85.04 t/h of molten salt in Heat Exchanger 3, heating the molten salt from 190 °C to 390 °C. The steam after heat exchange (1.48 MPa, 380 °C) is depressurized and returned to the low-pressure cylinder for work production.

(3) Scheme C3

Under 30% THA conditions, a small amount of steam (5.29 MPa, 600 °C, 150 t/h) is extracted from the main steam pipeline and used as the heat source. The steam is cooled to 450 °C and then directed to Heat Exchanger 1, where it heats 301 t/h of molten salt from 190 °C to 390 °C. The steam after heat exchange (6.43 MPa, 280.1 °C) passes through an expansion valve and is merged into the cold reheat steam pipeline before returning to the turbine.

(4) Scheme C4

Under 30% THA conditions, 30 MW of surplus electricity generated by the generator is used to power an electric heater. This heater raises the temperature of 372.4 t/h of molten salt from 190 °C to 390 °C. The system flow diagram corresponding to this thermal storage process is shown in

Figure 4.

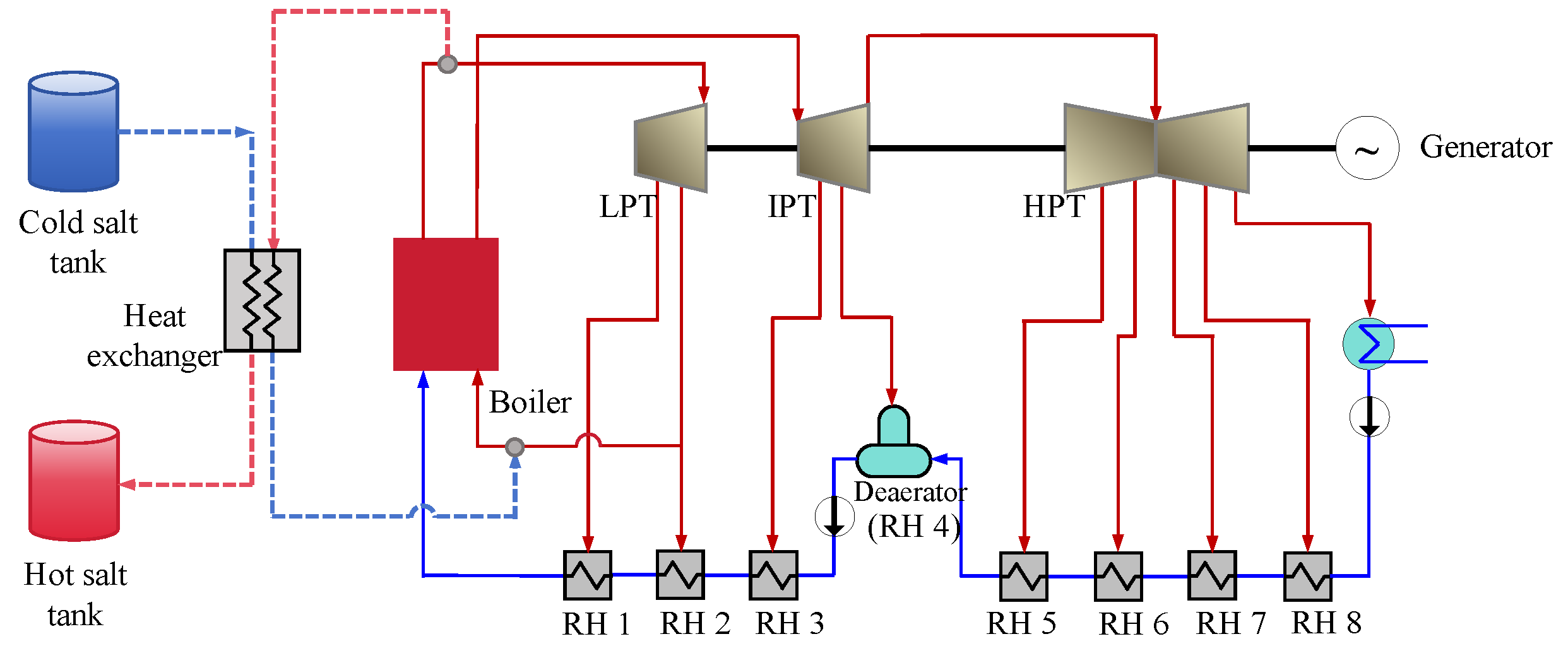

3.3. Discharging Schemes and Thermodynamic Calculations

To accurately compare the effects of different discharging schemes, the water flow rate for absorbing heat from molten salt was fixed at 100 t/h, and the temperature of the high-temperature molten salt was set to 390 °C—the upper limit of its operational range. The system flow diagrams for the four discharging schemes under the 100% THA condition are shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, with the specific processes described as follows:

(1) Scheme S1

Under 100% THA conditions, molten salt from the high-temperature tank is used as the heating medium. A bypass flow of 100 t/h of feedwater (1.30 MPa, 187 °C) is extracted after the deaerator. Its pressure is increased to 31.21 MPa using a booster pump. The water is heated to 300 °C by the high-temperature molten salt and is subsequently merged with the main boiler feedwater prior to being fed into the boiler, while the cooled molten salt is recycled back to the cold salt tank.

(2) Scheme S2

Under full-load (100% THA) conditions, 100 t/h of low-pressure condensate (0.27 MPa, 33.4 °C) is extracted downstream of the condenser pump. High-temperature molten salt serves as the heat source to heat this water to 150 °C and the water is then delivered to the deaerator.

(3) Scheme S3

Under 100% THA conditions, 100 t/h of bypass deaerated water (1.30 MPa, 187 °C) is extracted. After being pressurized by a booster pump, it is heated to 281.1 °C through heat exchange with high-temperature molten salt. It is further heated in a steam generator and a second heat exchanger to form high-temperature steam. The resulting steam (6.48 MPa, 365.5 °C) is merged into the cold reheat steam line and enters the boiler for work production.

(4) Scheme S4

Under 100% THA conditions, a bypass flow of deaerated water (1.30 MPa, 187 °C) is extracted. This water passes through two heat exchangers and one steam generator, where it absorbs heat from the high-temperature molten salt. It is gradually heated to the target parameters (0.52 MPa, 270.5 °C) to form medium-temperature steam, which is then directed to the low-pressure cylinder of the turbine for expansion and work production.

5. Results

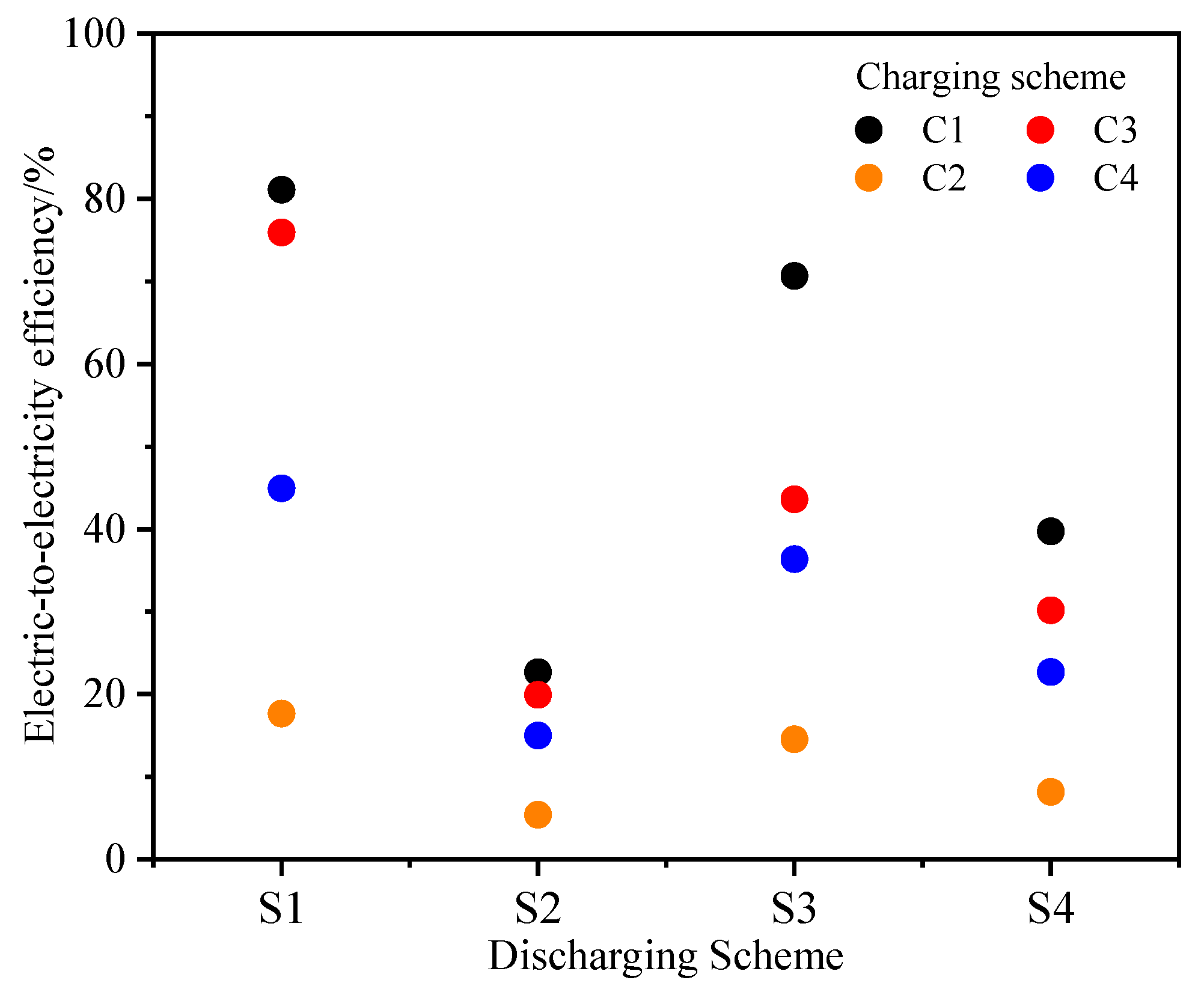

5.1. Efficiency

In the selection of different schemes, key parameters of each combined scheme must be observed and summarized. These parameters primarily include the round-trip efficiency, the thermal output power of the molten salt (

Qs) under discharging conditions, the pressure of steam/water (

p), and the inlet/outlet temperatures (

T_1.1,

T_1.2) of the heat exchangers or steam generators. This study was conducted with a fixed peak-shaving depth of 30 MW for various energy storage schemes and their corresponding discharging schemes. For the discharging process, a uniform water flow rate of 100 t/h was set to absorb heat from the high-temperature molten salt. The key parameters for each combined scheme under 100% THA discharging conditions are presented in

Figure 10.

(1) Thermal Storage Scheme with the Highest Round-Trip Efficiency

As shown in

Figure 10, scheme C1 is identified as the thermal storage scheme with the highest round-trip efficiency. The reasons are as follows. Firstly, the main steam possesses high temperature and pressure, containing substantial thermal energy. When this steam is utilized to heat the molten salt, the stored heat is more concentrated and stable. Furthermore, the main steam undergoes condensation during the heating process, which releases a significant amount of latent heat. Secondly, the condensed water is directly returned to the high-pressure heater, allowing it to be integrated into the regenerative cycle, thereby enhancing the overall heat recovery efficiency of the system. In contrast, the main steam used in scheme C3 does not fully condense, preventing complete utilization of its thermal energy. The steam temperature extracted from the hot reheat section in scheme C2 is also relatively lower. Introducing this waste heat into the intermediate/low-pressure system can lead to reduced heat transfer efficiency due to the smaller temperature difference. Additionally, scheme C4 involves the conversion of electrical energy to thermal energy, which incurs additional energy losses.

(2) Discharging Scheme with the Highest Round-Trip Efficiency

As shown in

Figure 10, scheme S1 is identified as the discharging scheme with the highest round-trip efficiency. The reasons are as follows. Firstly, the energy utilization in scheme S1 is more rational. This scheme allows heat to be reintroduced into the thermal cycle at an earlier stage. At the boiler feedwater stage, the water temperature is relatively low. Absorbing the same amount of heat results in a greater enthalpy rise, thereby elevating the energy level of the working fluid entering the boiler. This reduces heat loss and significantly improves the overall round-trip efficiency of the system. Secondly, compared to other schemes, the water is heated at a relatively lower temperature in this scheme. The temperature difference with the molten salt is relatively smaller, leading to fewer irreversible losses during the heat transfer process.

Lower return temperatures are observed in schemes S3 and S4, indicating a lower grade of thermal energy utilization where a portion of the thermal energy cannot be effectively recovered. Although scheme S2 can utilize some low-grade waste heat, the large temperature difference involved in absorbing heat from the low-temperature cooling water after the condenser and returning it to the deaerator significantly reduces thermal efficiency. Moreover, it requires longer pipelines and more equipment for transportation and heating, which increases system complexity and energy losses. Although scheme S1 demonstrates the highest efficiency, the efficiency of S3 is only slightly lower. Therefore, it is necessary to compare these two schemes further by considering other evaluation indicators.

(3) Combined scheme with the best round-trip efficiency

As shown in

Figure 10, the combined scheme C1-S1 achieves the highest round-trip efficiency of 81.11%. The round-trip efficiency of the combined scheme C3-S1 is 75.93%, which is 5.18% lower than that of C1-S1. The scheme C1-S3 ranks next, with an efficiency of 70.68%. The round-trip efficiencies of other combined schemes are considerably lower than these two. Since the difference between C1-S1 and C3-S1 is relatively small, further comparison and analysis using other evaluation indicators are required to better determine and select the optimal scheme.

5.2. Energy Storage Capacity

Based on the daily load curve of the Luxi region in Shandong Province, the charge duration was designed to be 6 h. Under the premise that the discharging schemes remained consistent and a uniform peak-shaving depth of 30 MW was maintained for all charging schemes, the energy storage capacities of schemes C1, C2, C3, and C4 under charging conditions were calculated. The results are presented in

Table 5.

Firstly, according to the data in

Table 5, the thermal storage capacities of schemes C1 and C3 are 1.64 times and 1.46 times that of scheme C4, respectively, under the same peak-shaving requirement. This difference is primarily attributed to the distinct energy conversion pathways. In schemes C1 and C2, charging is achieved by extracting main steam. The thermal energy contained in the steam is directly transferred and stored in the high-temperature molten salt through a heat exchange process. In contrast, scheme C4 requires the steam energy to first drive the turbo-generator to produce electricity. This electricity is then converted back into thermal energy to heat the molten salt. Since the thermal-to-electrical conversion efficiency of steam turbines is typically only about 40%, the overall efficiency of scheme C4, which undergoes multiple “thermal–electrical–thermal” conversions, is lower than the direct “thermal–thermal” conversion method using steam extraction. Consequently, its heat storage capacity is significantly reduced.

Furthermore, the energy storage capacities of C1 and C3 are 3.09 times and 2.76 times that of C2, respectively. This phenomenon occurs because the reheat steam used in C2 has a relatively low pressure (only 1.5 MPa), making it difficult to effectively utilize its latent heat of phase change. This scheme requires the steam to be desuperheated and depressurized before being condensed and returned to the water-steam system after heat exchange. This process is accompanied by significant condensate heat loss, resulting in poor overall thermal storage performance. Additionally, the storage capacity of scheme C1 is also greater than that of scheme C3. This is because the main steam used in scheme C3 does not undergo complete condensation, preventing the full utilization of its thermal energy. Therefore, scheme C1 is identified as the optimal choice for energy storage capacity.

5.3. Peak Shaving Depth and Peak Power Generation

To evaluate the impact of different combined schemes on the load regulation range of the power plant, the peak-shaving depth and peak power generation of various combinations based on charging schemes C1 and C3 were calculated and analyzed, as shown in

Figure 11.

It can be observed that the peak-shaving depth of scheme C1 is 1.47 times greater than that of C3, indicating that C1 contributes more significantly to reducing boiler load. During heat discharge, scheme S3 achieves the highest peak power generation, which is 3.97, 12.53, and 1.87 times that of schemes S1, S2, and S4, respectively. This demonstrates that S3 generates the largest amount of additional electricity by utilizing the heat stored in the molten salt TES, making it the most effective during peak electricity demand periods.

5.4. Exergy Loss and Thermal Efficiency

To further identify the optimal scheme, the exergy loss and thermal efficiency of three combined schemes were calculated, as summarized in

Table 6. Since the heat discharge process involves relatively straightforward heat transfer with fewer energy conversion stages, the associated exergy loss is small. In contrast, the heat charging process includes multiple complex heat transfer and energy conversion steps, which are highly irreversible and lead to greater exergy loss. Therefore, only the exergy loss during charging was calculated and compared.

As shown in

Table 6, scheme C1 exhibits the lowest exergy loss. Although schemes C1, C2, and C3 all use steam extraction to heat molten salt, the largest exergy loss on the steam side occurs during condensation. However, in schemes C2 and C3, the condensation heat is used for internal heat exchange within the unit rather than for heating molten salt, so the corresponding exergy benefit is not obtained by the molten salt. As a result, the overall exergy loss in these schemes is higher than that of C1. Among all schemes, C4 exhibits the highest exergy loss, nearly twice that of C1, primarily because electrical heating, which involves high-grade energy, also leads to significant exergy loss. Thus, from the perspective of energy quality, scheme C1 is more efficient than C3. As presented in

Table 6, the thermal efficiencies of the three combined schemes are similar, but their exergy losses differ considerably. In terms of energy quantity, the thermal efficiencies of combined schemes C1-S1 and C3-S1 are both above 47%, whereas the thermal efficiency of C1-S3 is 45.96% due to differences in the heat discharge strategy.

Additionally,

Figure 12 provides a multidimensional comparison of the three combined schemes based on different performance indicators. It is highlighted that the combined scheme C1-S1 offers advantages in economic performance, operational flexibility, and deep peak-shaving capability. However, a trade-off exists in terms of additional power generation. Overall, the proposed C1-S1 combination is considered to be of significant practical value.

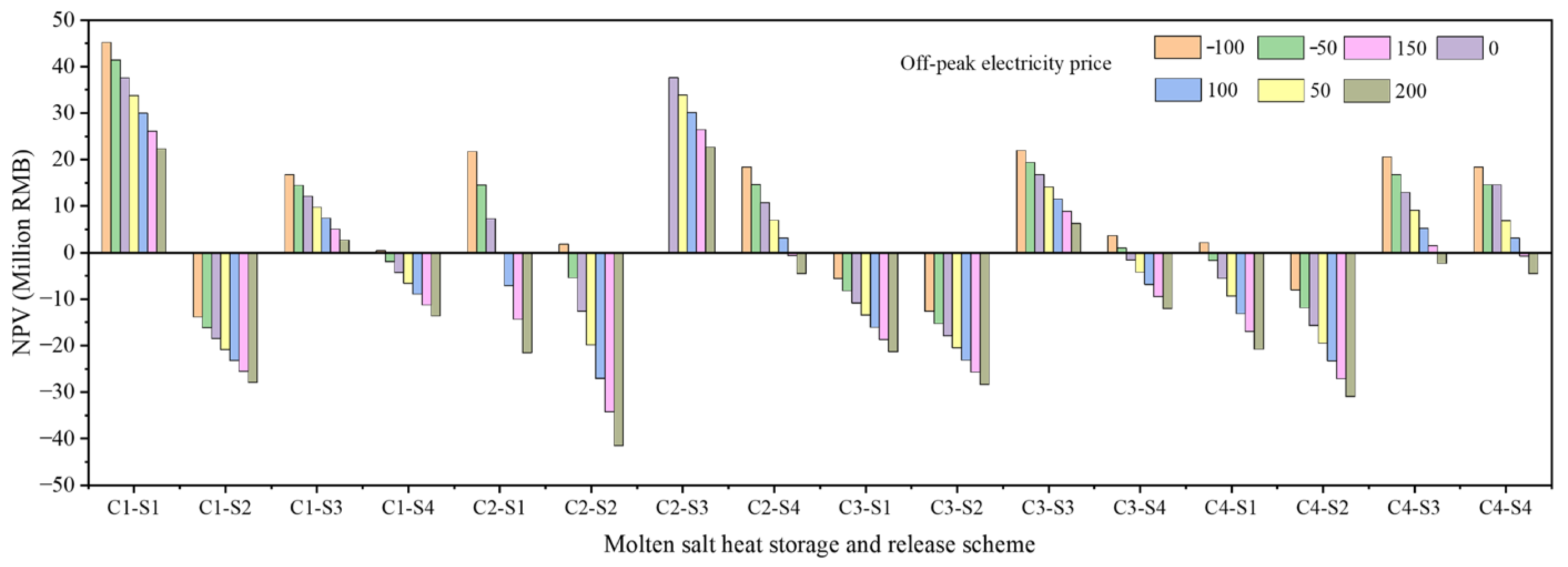

5.5. Economic Analysis

In addition to thermodynamic analysis, a comprehensive economic analysis should also be conducted for the molten salt thermal storage system. The charge duration, discharge duration, and operation mode of different molten salt charge and discharge system configurations can be determined based on parameters such as their charge and discharge power. With the annual charge and discharge period calculated as 240 days, and the off-peak electricity price and peak electricity price set at 0 RMB/(MWh) and 900 RMB/(MWh, respectively, the annual profit, investment cost, and payback period corresponding to each configuration can be obtained, as shown in

Figure 13.

As can be seen from

Figure 13, S3 and S4 have a relatively significant impact on the cost of the molten salt energy storage system, while the overall investment costs of all schemes are not substantially different. Since the off-peak electricity price is set to 0 RMB/(MWh), the revenue of the coal fired power plant mainly depends on the discharge capacity of the molten salt energy storage system. Due to the minimum discharge capacity under Scheme S2, its annual revenue is the lowest and the payback period is also the longest. Among all configurations, C1-S1 exhibits the best economic performance, enabling the power plant to achieve an annual income of 4.86 million RMB. Based on the economic analysis, molten salt thermal storage technology demonstrates favorable economic benefits in the electricity market and can bring considerable economic returns to power plants.

Sensitivity of Off-Peak Electricity Prices

As the variation in off-peak electricity prices can affect the economic viability of power plants, this paper analyzes the sensitivity of off-peak electricity prices to NPV and payback period. The results are shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

As the off-peak electricity price increases, a gradual downward trend is observed in the net present values (NPV) of power plants equipped with different molten salt energy storage system configurations. Correspondingly, a progressive upward trend is exhibited by the payback periods of these power plants.

For the configurations of C1-S2, C3-S1, C3-S2 and C4-S2, negative NPVs are maintained even when the off-peak electricity price decreases to −100 RMB/MWh. This outcome demonstrates that these retrofit schemes lack economic viability. Similarly, low economic efficiency is verified in the retrofit schemes of C1-S4, C2-S2, C1-S2, C3-S4 and C4-S1.

The C1-S1 configuration is confirmed as the most economically optimal retrofit scheme. Even when the off-peak electricity price rises to 200 RMB/MWh, an NPV of 45.15 million RMB is still achieved by the power plant, and a payback period of 4.85 years is recorded under this scenario.

6. Conclusions

This study focuses on a 660 MW coal-fired unit, and multiple schemes are investigated for integrating a molten salt energy storage system to enhance its deep peak-shaving capacity and operational flexibility. Through the construction of sixteen charging-discharging combinations and a comprehensive evaluation using a simulation model from multiple perspectives—including round-trip efficiency, peak-shaving performance, exergy efficiency, and thermal efficiency—the following core conclusions are drawn:

(1) The coupling of a molten salt TES is demonstrated to effectively achieve thermoelectric decoupling in thermal power units, significantly enhancing their flexibility in responding to load variations. Concurrently, this technology broadens the unit’s peak-shaving range. Not only is the deep peak-shaving capability strengthened, but the response to grid peak loads is also improved. This provides favorable conditions for accommodating a greater share of fluctuating renewable energy.

(2) During the discharging process, the scheme that utilizes high-temperature molten salt to heat the feedwater bypassing the high-pressure heaters demonstrates superior overall performance compared to other alternatives. This superiority is evident in both the increase in power generation output and the control of exergy loss.

(3) Among all scheme combinations, C1-S1 exhibits the most optimal comprehensive performance. This in turn brings about the most significant enhancement to power plant operations, with the scheme attaining both round-trip efficiency and equivalent round-trip efficiency in excess of 80%, alongside the lowest energy loss. A thermal storage capacity of 294.34 MWh is achieved, while the system exergy loss is limited to 6258 kW.

Besides regular power generation, coal-fired power plants also need to undertake auxiliary services such as frequency regulation. The existing steady-state model cannot meet the requirement of “real-time control accuracy”. Therefore, dynamic modeling will be supplemented in the future. In addition, the heating capacity and power generation capacity of coal-fired units will be affected by the integration of the molten salt storage systems. Therefore, we will consider further coupling other equipment to enhance the operation capacity of power plants in future work, such as electric boilers and compressed air energy storage equipment. Furthermore, comprehensive sensitivity analysis is planned for our subsequent research. This analysis will cover critical factors including energy storage system parameters and the amplitude of electricity price fluctuations.