Naphtha Production via Catalytic Hydrotreatment of Refined Residual Lipids: Validation in Industrially Relevant Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

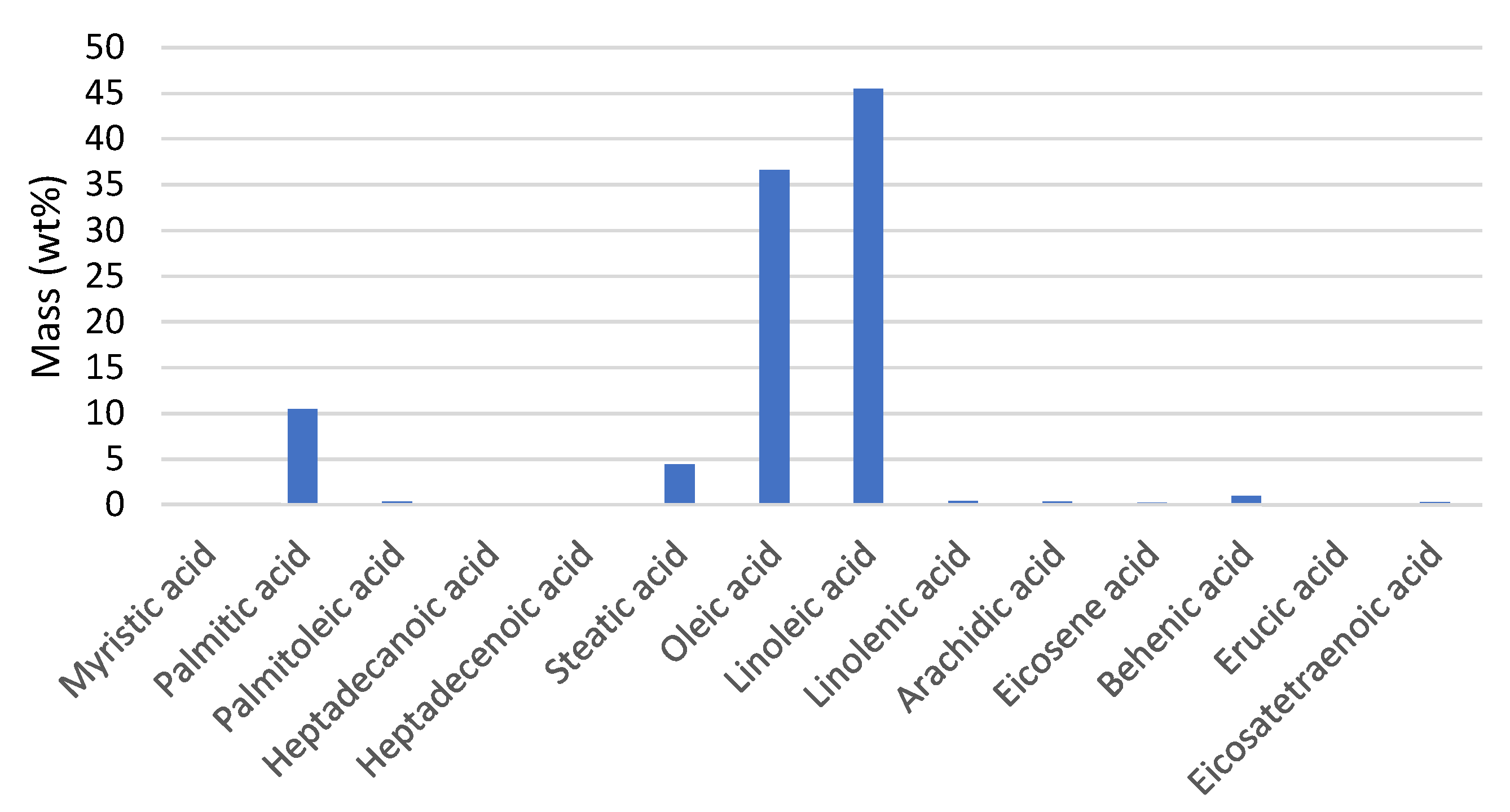

2.1. Feedstock-WCO

| Properties | Units | WCOs | Refined WCOs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 288 K | g/ml | 0.921 | 0.922 |

| Sulfur | wppm | 23.9 | 14.4 (523 1) |

| Hydrogen | wt% | 11.92 | 11.87 |

| Carbon | wt% | 77.64 | 77.47 |

| Nitrogen | wppm | 165.5 | 26.3 (46 1) |

| Oxygen | wt% | 10.4 | 10.6 |

| Water dissolved | wt% | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| TAN | mgKOH/g | 7.53 | 0.45 |

| Viscosity at 313 K | cSts | 34.42 | 34.13 |

| H/C ratio | - | 0.153 | 0.152 |

| O/C ratio | - | 0.133 | 0.133 |

| HHV | MJ/kg | 41.06 | 41.09 |

| Pour point | K | - | 267 |

| CFPP | K | 299 | 293 |

| Simulated Distil. Curve | |||

| IBO | K | 818 | 693 |

| 10 wt% | K | 819 | 847 |

| 30 wt% | K | 877 | 878 |

| 50 wt% | K | 884 | 885 |

| 70 wt% | K | 888 | 888 |

| 90 wt% | K | 890 | 891 |

| 95 wt% | K | 892 | 897 |

| FBP | K | 992 | 998 |

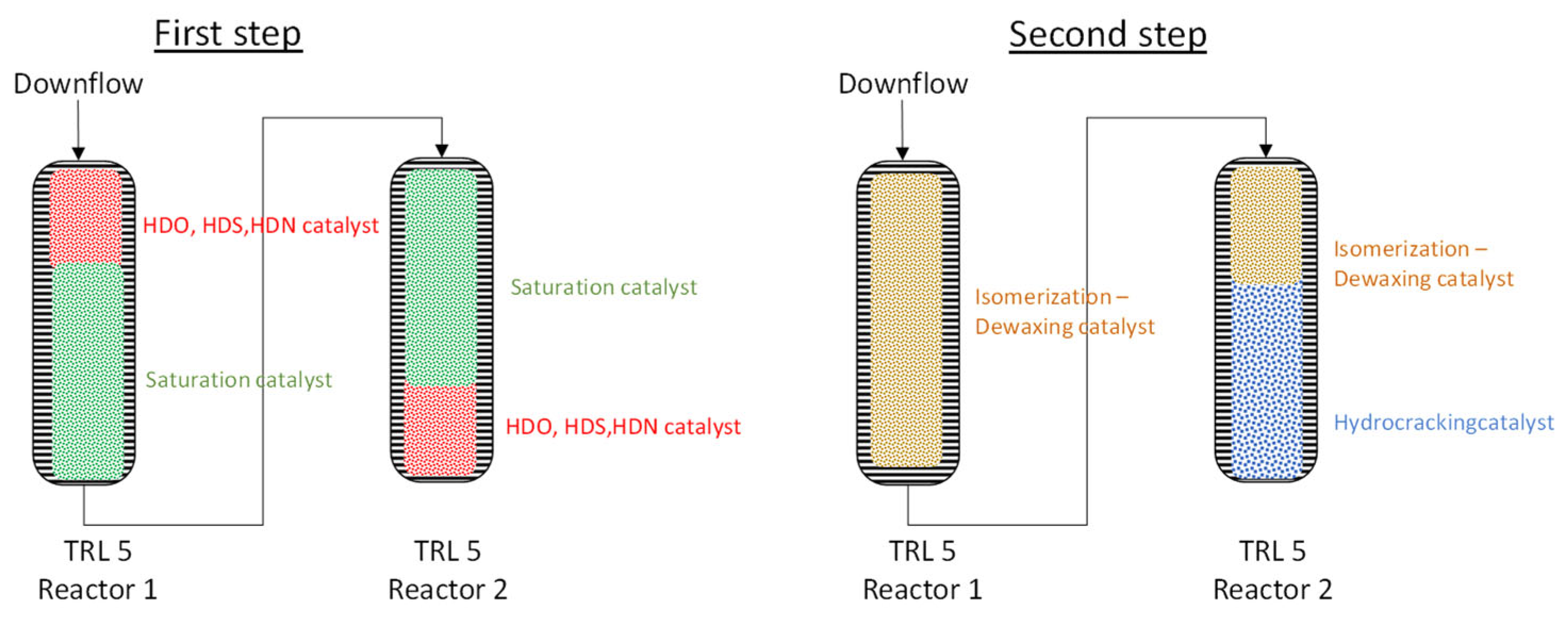

2.2. Catalyst

2.3. Analysis

| Analysis | Methods | Accuracy | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | ASTM D-4052 | 0.0002 g/ml | [22] |

| SIM-DIS | ASTM D-7169 | 4 °C | [23] |

| C content | LECO ASTM D-5291 | 0.60 wt% | [24] |

| H content | LECO ASTM D-5291 | 0.20 wt% | [24] |

| S content | XRFS analyzer ASTM D-4294 | 3 wt% | [25] |

| N content | ASTM D-4629 | 3 wt% | [26] |

| Water content | ASTM D-6304 or ASTM E-203 | 5 and 3 wt% | [20,27] |

| TAN | ASTM D-664 | 5% | [28] |

| Kinematic viscosity | ASTM D445 | 0.3% | [29] |

| Cetane index | ASTM D-976 | Calculated by SIMDIS | [30] |

| Pour point | ASTM D-97 | 3 °C | [31] |

| Micro carbon residue (MCR) | ASTM D4530 | 1% | [32] |

| CFPP | EN116 | 1 °C | [33] |

2.4. Testing Infrastructure

2.5. Experimental Procedure

| Parameters | Units | Cond. 1 | Cond. 2 | Cond. 3 | Cond. 4 | Cond. 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | K | 603 | 633 | 633 | 663 | 663 |

| Pressure | MPa | 10.34 | 10.34 | 10.34 | 13.78 | 13.78 |

| Hydrogen/oil ratio | scfb | 5000 | 5000 | 5000 | 5000 | 5000 |

| LHSV | h−1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.33 |

| Duration | DOS 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

3. Results

3.1. WCO Evaluation

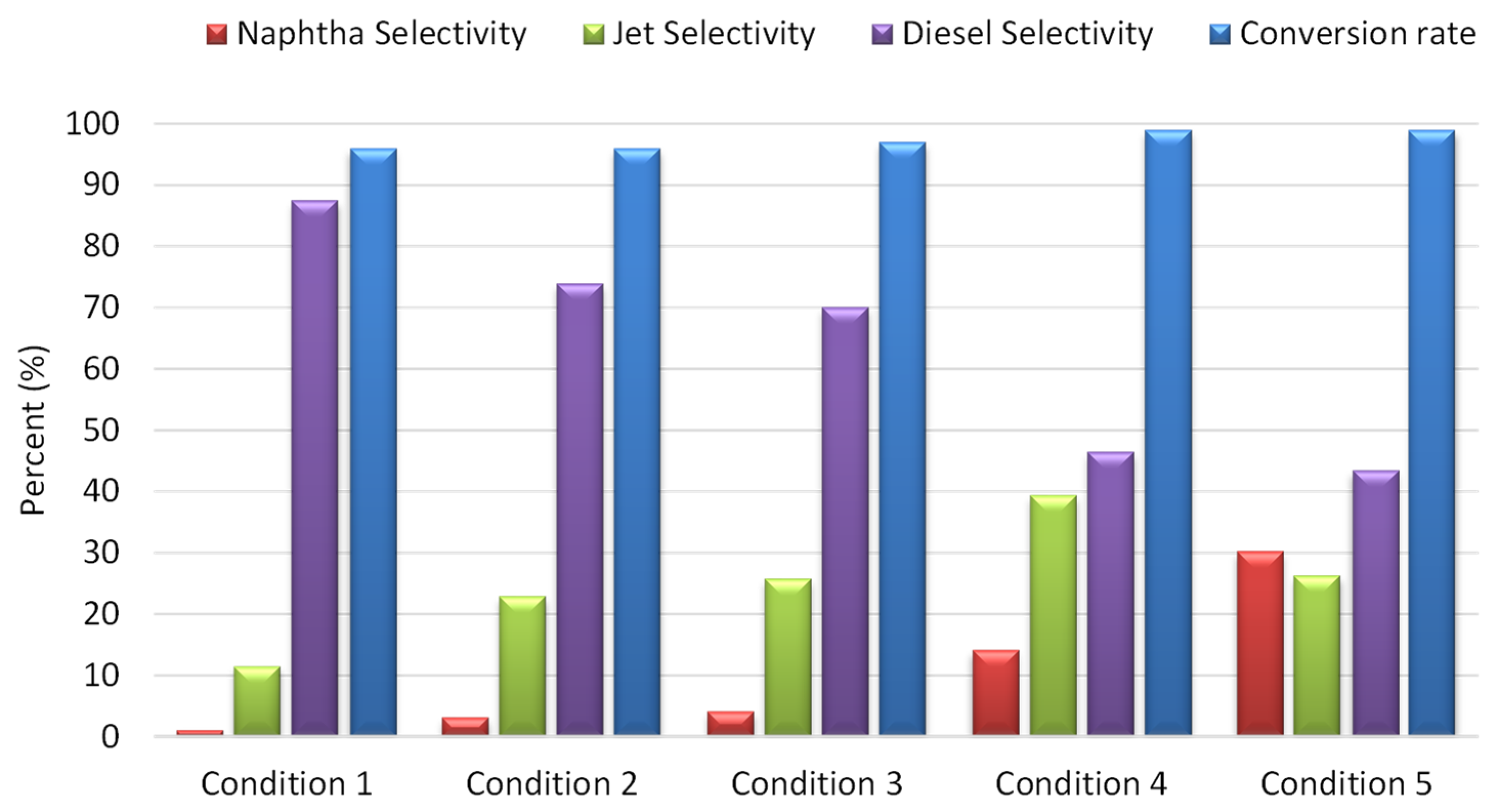

3.2. Experimental Results from Process Optimization

| Gases/wt% | Cond. 1 | Cond. 2 | Cond. 3 | Cond. 4 | Cond. 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 90.705 | - | 90.423 | 86.641 | 85.371 |

| Methane | 1.045 | - | 0.000 | 3.998 | 4.981 |

| Ethane | 0.376 | - | 0.000 | 0.570 | 0.641 |

| Propane | 2.277 | - | 2.559 | 2.869 | 2.646 |

| Isobutane | 0.014 | - | 0.094 | 0.510 | 0.000 |

| N-Butane | 0.023 | - | 0.073 | 0.352 | 0.399 |

| Isopentane | 0.001 | - | 0.027 | 0.219 | 0.237 |

| N-Pentane | 0.003 | - | 0.018 | 0.119 | 0.116 |

| Carbon Dioxide | 1.304 | - | 0.000 | 0.767 | 0.619 |

| Carbon Monoxide | 0.055 | - | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.061 |

| Hydrogen Sulfide | 0.029 | - | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.020 |

- Condition 1: Naphtha yields = 2 wt%, jet yields = 10 wt%, diesel yields = 84 wt%;

- Condition 2: Naphtha yields = 3 wt%, jet yields = 22 wt%, diesel yields = 71 wt%;

- Condition 3: Naphtha yields = 4 wt%, jet yields = 27 wt%, diesel yields = 66 wt%;

- Condition 4: Naphtha yields = 17 wt%, jet yields = 37 wt%, diesel yields = 45 wt%;

- Condition 5: Naphtha yields = 34 wt%, jet yields = 23 wt%, diesel yields = 42 wt%.

| Properties | Units | Cond. 1 | Cond. 2 | Cond. 3 | Cond. 4 | Cond. 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 288 K | g/ml | 0.789 | 0.787 | 0.786 | 0.777 | 0.747 |

| Sulfur | wppm | 4.94 | 5.12 | 22.50 | 2.70 | 12 |

| Hydrogen | wt% | 15.05 | - | 15.04 | 15.08 | 14.90 |

| Carbon | wt% | 84.95 | - | 84.9 | 84.89 | 85.05 |

| Oxygen | wppm | 0.00 | - | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Nitrogen | wt% | 0.30 | - | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Water dissolved | wt% | 0.001 | - | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Aqueous phase | v/v % | 8.05 | 7.95 | 8.77 | 9.72 | 9.39 |

| TAN | mgKOH/g | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Viscosity at 313 K | cSts | 3.853 | - | 3.454 | 2.425 | 1.352 |

| HHV | MJ/kg | 47.38 | - | 47.35 | 47.39 | 47.236 |

| CFPP | K | 294 | - | 292 | 267 | 255 |

| Flash point | K | 390 | - | 364 | 318 | <284 |

| Hydrogen consumption | Sl/l feed 1 | 351 | - | 401 | 417 | 420 |

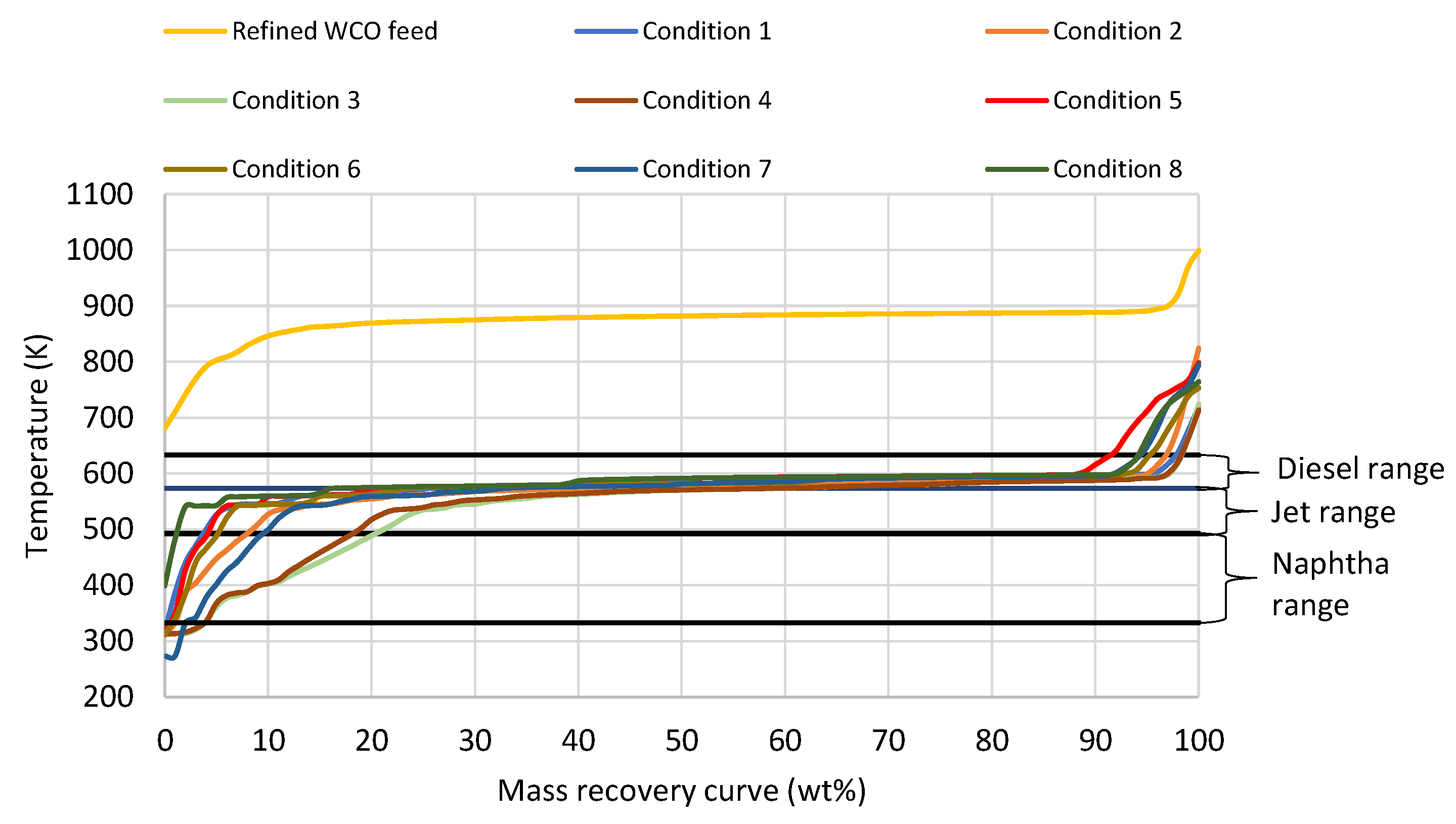

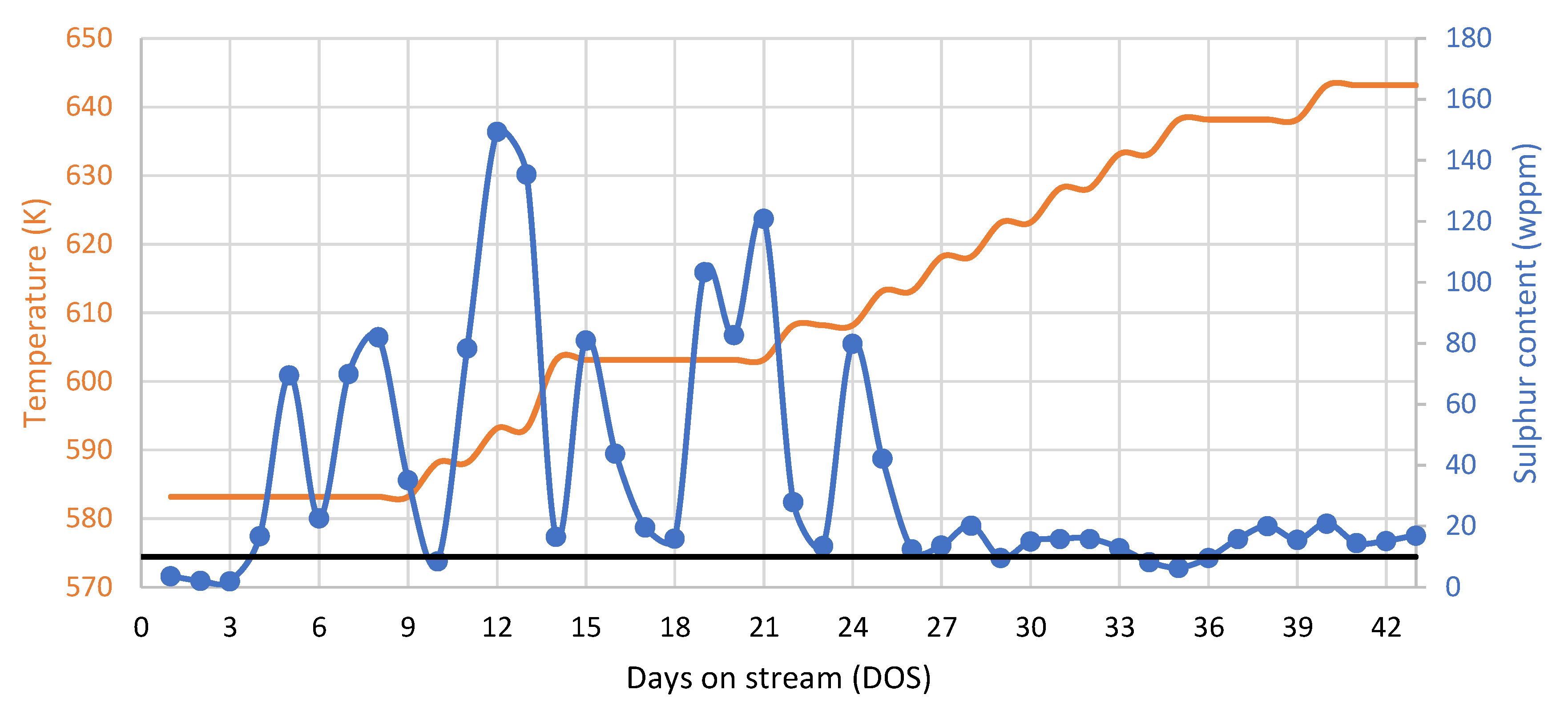

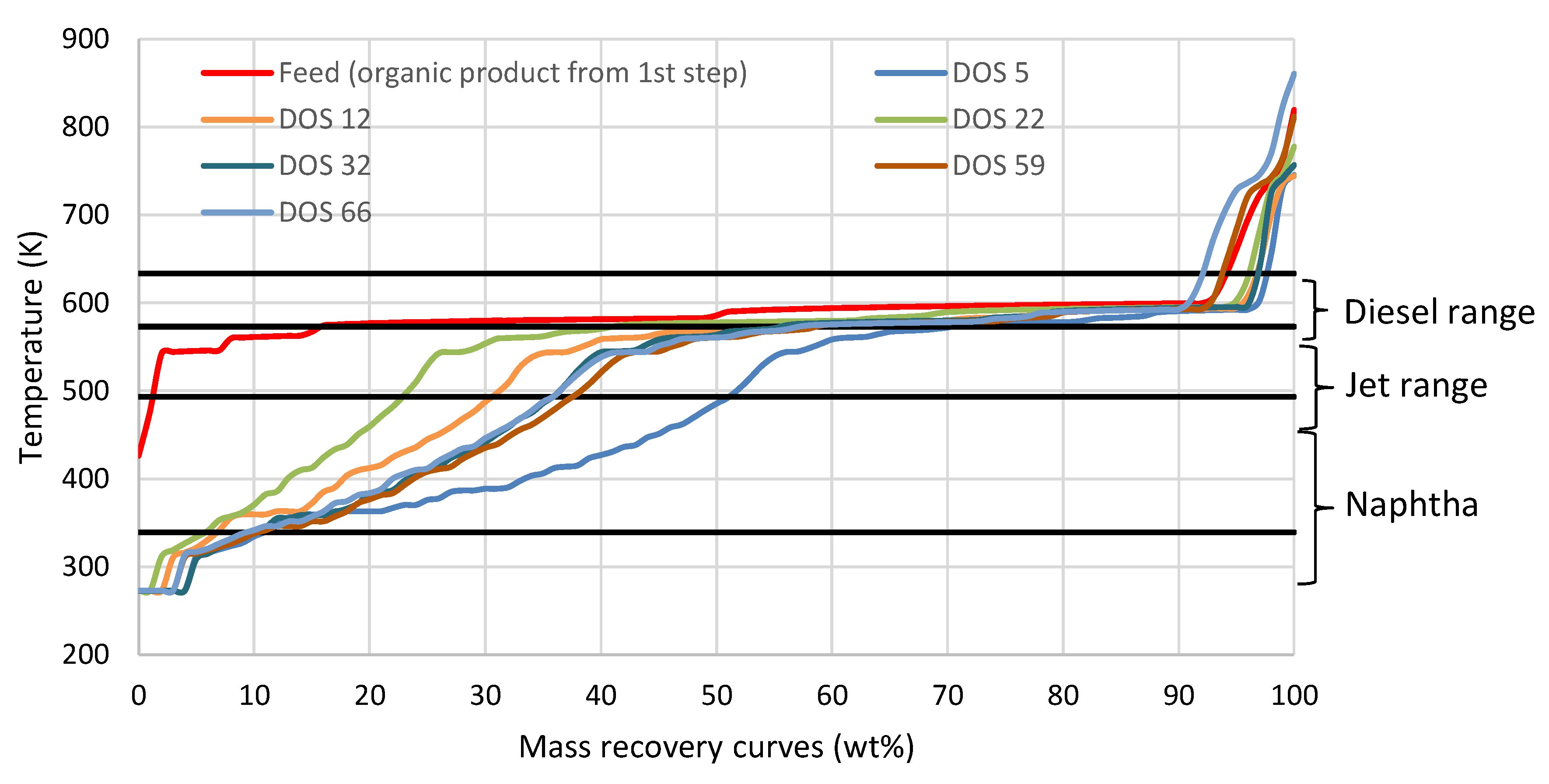

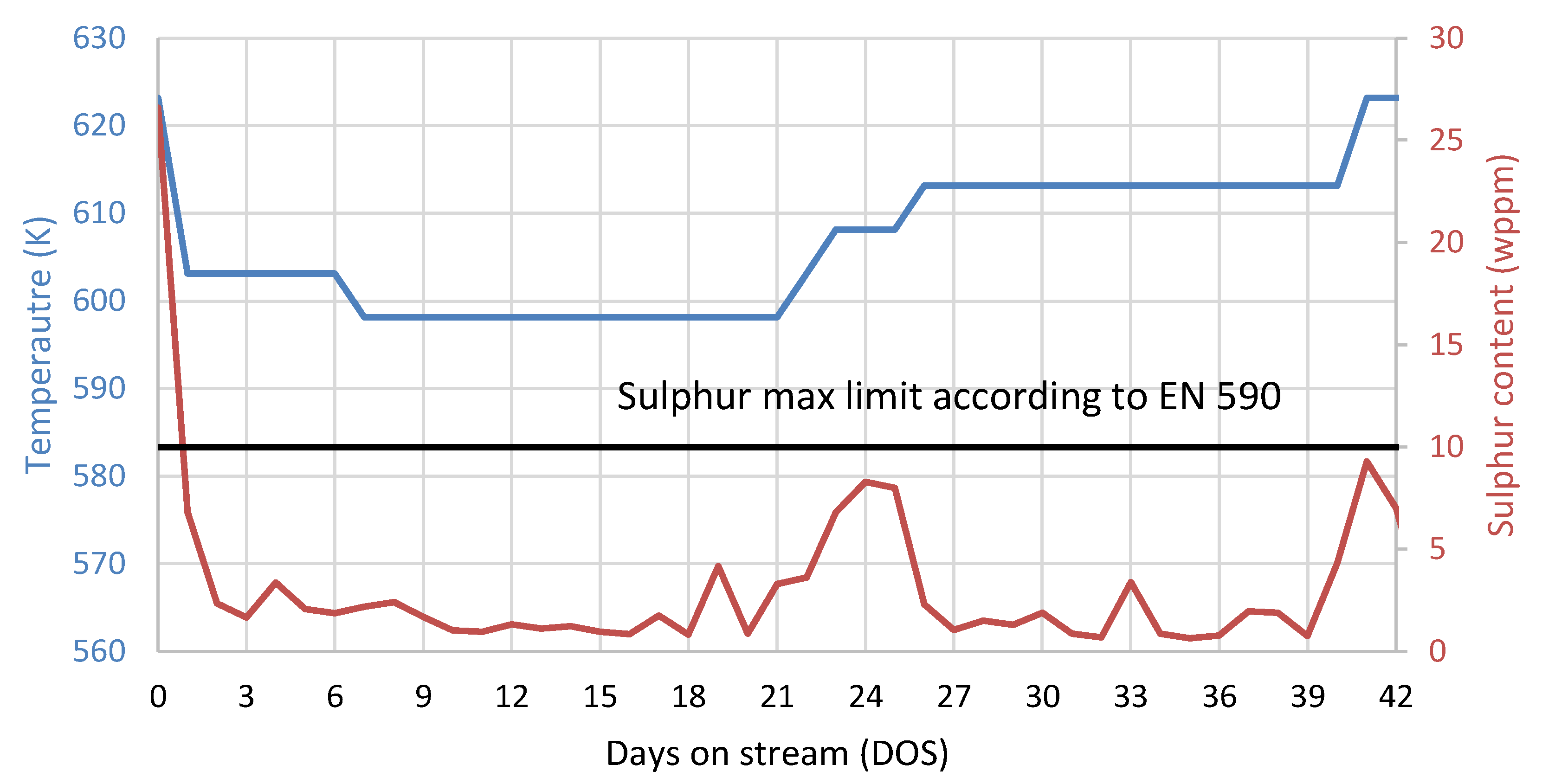

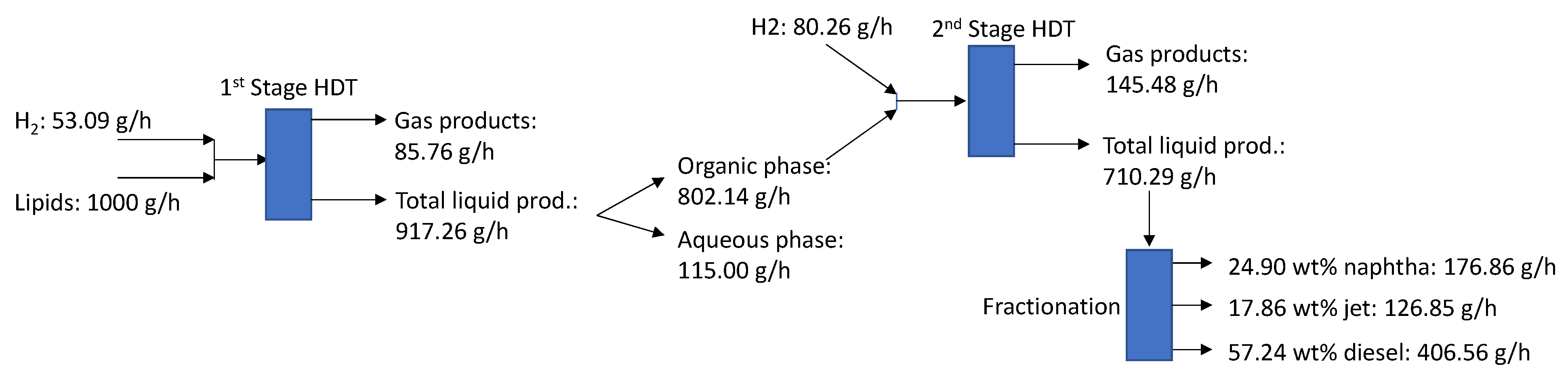

3.3. Demonstration and Validation of the Technology in Industrially Relevant Large-Scale Pilot Plant

| Parameters | Temp. Reactor 1 (K) | Temp. Reactor 2 (K) | Pressure (MPa) | LHSV (h−1) | H2/Oil Ratio (Scfb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition 1 | 603 | 603 | 10.34 | 0.40 | 5000 |

| Condition 2 | 623 | 623 | 10.34 | 0.40 | 5000 |

| Condition 3 | 633 | 633 | 10.34 | 0.35 | 5000 |

| Condition 4 | 633 | 643 | 10.34 | 0.35 | 5000 |

| Condition 5 | 573 | 573 | 10.34 | 0.6 | 5000 |

| Condition 6 | 573 | 613 | 10.34 | 0.6 | 5000 |

| Condition 7 | 573 | 633 | 10.34 | 0.5 | 5000 |

| Condition 8 | 573 | 633 | 10.34 | 0.3 | 5000 |

3.4. Fuel Quality Evaluation

| Properties | Units | Method | EN 590 Diesel | Commercial Diesel | e-Diesel | 10% Blend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 288 K | g/mL | EN ISO 12185 [56] | 0.8200–0.8450 | 0.8267 | 0.7878 | 0.8228 |

| Flash point | K | EN ISO 2719 [57] | >328 | 332 | 414 | 335 |

| Total sulfur | ppm-w | EN ISO 20846 [58] | <10 | 7.8 | 0.4 | 7.2 |

| Kinematic viscosity at 313 K | cSt | EN ISO 3104 [59] | 2–4.5 | 2.728 | 3.981 | 2.927 |

| Cetane index | EN ISO 4264 [60] | >46 | 56.9 | 96.7 | 60.1 | |

| Cetane number | EN ISO 5165 [61] | >51 | 57.2 | >77.1 | 57.9 | |

| Carbon residue on 10% dist.res | % w/w | EN ISO 10370 [62] | <0.3 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Copper strip corros.,3 h 223 K | EN ISO 2160 [63] | Class 1a | Class 1a | Class 1a | Class 1a | |

| Water (K-F) in products | ppm-w | EN ISO 12937 [64] | <200 | 130 | 68 | 98 |

| Ash | % w/w | EN ISO 6245 [65] | <0.01 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| C.F.P.P. 1 | K | EN 116 [33] | >278 | 267 | 286 | 269 |

| Total contamination | mg/Kg | EN 12662 [66] | <24 | 15.1 | 11.6 | 14.0 |

| Oxidation stability | h | EN 15751 [67] | >20 | >20 | >20 | >20 |

| Polyaromatic hydrocarbons | % w/w | EN 12916 [68] | <8 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 1.7 |

| Lubricity, c.w.s.d. 1.4 213 K | μm | EN ISO 12156-1 [69] | <460 | 320 | 620 | 340 |

| 95 v/v % recovered | K | EN ISO 3405 [70] | <633.1 | 631.2 | 603.2 | 630.5 |

| Recovered at 523 K | v/v % | EN ISO 3405 [70] | <338.1 | 308.3 | 273.1 | 304.0 |

| Recovered at 623 K | v/v % | EN ISO 3405 [70] | >358 | 365.8 | >368.1 | 366.4 |

| Properties | Units | Method | Jet A1 Specifications | Commercial Jet | e-Jet | Blend (90/10 v/v % Commercial Jet/e-Jet Fraction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 288 K | g/mL | ASTM D4052 [22] | 0.7750–0.8400 | 0.7979 | 0.7743 | 0.7955 |

| I.B.P. | K | ASTM D86 [71] | 423.2 | 487.3 | 425.7 | |

| 10 v/v % recovered | K | ASTM D86 [71] | <478.1 | 445.1 | 508.6 | 446.7 |

| 50 v/v % recovered | K | ASTM D86 [71] | 472.2 | 531.9 | 475.8 | |

| 90 v/v % recovered | K | ASTM D86 [71] | 509.7 | 551.6 | 520.4 | |

| F.B.P. | K | ASTM D86 [71] | <573.1 | 527.4 | 560.5 | 539.9 |

| Residue | v/v % | ASTM D86 [71] | <1.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Loss | v/v % | ASTM D86 [71] | <1.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Saybolt Color | ASTM D156 [72] | 30 | 30 | 30 | ||

| Appearance | VISUAL | Clear & Bright | Clear & Bright | Clear & Bright | Clear & Bright | |

| Flash point (Tag) | K | ASTM D56 [73] | >311.1 | 314.1 | 367.1 | 315.1 |

| Copper strip corros.,2 h-373 K | ASTM D130 [74] | Class 1a-Class 1b | Class 1a | Class 1a | Class 1a | |

| Total sulfur | % w/w | ASTM D4294 [25] | <0.3 | 0.100 | 0.0003 | 0.096 |

| Total acidity | mg KOH/g | ASTM D3243 [75] | <0.015 | 0.0026 | 0.0220 | 0.0030 |

| Mercaptan Sulfur | % w/w | ASTM D3277 [76] | <0.003 | 0.0010 | 0.0003 | 0.0007 |

| Existent gum | mg/100 mL | ASTM D381 [77] | <7 | 2.1 | 1.4 | |

| FIA/aromatics | v/v % | ASTM D1319 [78] | <25 | 15.9 | 1.5 | 15.6 |

| Net heat of combustion | Mj/kg | ASTM D3338 [79] | 43.31 | 44.06 | 43.35 | |

| Freezing point | K | ASTM D2386 [80] | <226 | 223 | 266 | 234 |

| Kinematic viscosity at 253 K | cSt | ASTM D445 [29] | <8 | 4.200 | 1.297 | |

| Smoke point | mm | ASTM D1322 [81] | >18 | 23.0 | >50 | 26.3 |

| Test temperature | K | ASTM D3241 [82] | 533.1 | 533.1 | 533.1 | 533.1 |

| Change in pressure drop | mm Hg | ASTM D3241 [82] | <25 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Interferometric Tube rating | nm | ASTM D3241 [82] | <85 | 18 | 21 | |

| Naphthalenes | v/v % | ASTM D1840 [83] | <3 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 0.69 |

| Microseparometer rating (MSEP-A) | ASTM D3948 [84] | >70 | 87 | 92 | 90 | |

| Specific conductivity | pS/m | ASTM D2624 [85] | 50–600 | 500 | 1 | 343 |

| Particulate matter | mg/L | ASTM D5452 [86] | <1 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Cum. channel particle counts ≥ 4 μm | IP 565/ISO 4406 [87,88] | 149.0/14 | 176.1/15 | 131.6/14 | ||

| Cum. channel particle counts ≥ 6 μm | IP 565/ISO 4406 [87,88] | 48.0/13 | 84.9/14 | 10.3/11 | ||

| Cum. channel particle counts ≥ 14 μm | IP 565/ISO 4406 [87,88] | 2.0/08 | 24.6/12 | 0.9/07 | ||

| Cum. channel particle counts ≥ 21 μm | IP 565/ISO 4406 [87,88] | 1.0/06 | 11.3/11 | 0.3/06 | ||

| Cum. channel particle counts ≥ 25 μm | IP 565/ISO 4406 [87,88] | 0.0/06 | 6.3/10 | 0.2/05 | ||

| Cum. channel particle counts ≥ 30 μm | IP 565/ISO 4406 [87,88] | 0.0/04 | 3.2/09 | 0.1/05 |

| Properties | Units | Method | EN 228 Gasoline Specifications | Commercial Gasoline | e-Naphtha | Blend (90/10 v/v % Commercial Gasoline/e-Naphtha Fraction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 288 K | g/ml | EN ISO 12185 [56] | 0.7200–0.7750 | 0.7469 | 0.7277 | 0.7456 |

| Vapor pressure at 310.9 K-Mini | kPa | EN-13016-1 [91] | 45-60 | 57.6 | 11.9 | 52.9 |

| Total sulfur | ppm-w | EN ISO 20846 [58] | <10 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Research octane number, RON | EN ISO 5164 [92] | >95 | 96.8 | <40.0 | 92.2 | |

| Motor octane number, MON | EN ISO 5163 [93] | >85 | 86.5 | <40.0 | 84.4 | |

| Copper strip corros.,3 h-323 K | EN ISO 2160 [63] | Class 1 | Class 1a | Class 1a | Class 1a | |

| Existent gum (solvent washed) | mg/100 mL | EN ISO 6246 [94] | <5 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Benzene | v/v % | EN ISO 22854 [95] | <1 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.82 |

| Aromatics | v/v % | EN ISO 22854 [95] | <35 | 33.2 | 3.1 | 30.6 |

| Olefins | v/v % | EN ISO 22854 [95] | <18 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Bio-methanol | v/v % | EN ISO 22854 [95] | <3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Bio-ethanol | v/v % | EN ISO 22854 [95] | <5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Bio-ether > 5C (MTBE-ETBE-TAME) | v/v % | EN ISO 22854 [95] | 13.2 | 0.0 | 11.9 | |

| Oxygen content | w/w % | EN ISO 22854 [95] | <2.7 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Appearance | VISUAL | Clear & Bright | Clear & Bright | Clear & Bright | Clear & Bright | |

| Color | VISUAL | Undyed | Undyed | Undyed | Undyed | |

| I.B.P. | K | EN ISO 3405 [70] | 307.6 | 349.3 | 307.7 | |

| F.B.P. | K | EN ISO 3405 [70] | <483 | 452.6 | 500.4 | 464.5 |

| Evaporated at 343.1 K | v/v % | EN ISO 3405 [70] | 20–48 | 33.2 | 0.0 | 28.3 |

| Evaporated at 373.1 K | v/v % | EN ISO 3405 [70] | 46–71 | 61.4 | 4.4 | 56.2 |

| Evaporated at 423.1 K | v/v % | EN ISO 3405 [70] | >75 | 91.6 | 56.9 | 88.7 |

| Residue | v/v % | EN ISO 3405 [70] | <2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- A pretreatment process for WCOs was developed, improving their quality prior to catalytic hydrotreatment in terms of acidity and water content reduction.

- The severity of the hydrotreating process significantly affected the yields of the expected fuels.

- Higher naphtha yields were observed at an operating temperature of 663 K, pressure of 13.78 MPa and liquid hourly space velocity of 0.33 h−1, leading to 34 wt% naphtha, 23 wt% jet and 42 wt% diesel boiling range hydrocarbons.

- The process was successfully scaled up to the large-scale (TRL-5) hydrotreatment plant.

- The produced fractions were characterized and compared with the fossil fuel standards for diesel, gasoline and Jet A1.

- The blend of e-diesel with fossil diesel (at 10/90 v/v %) meets all specifications for commercial diesel and could be characterized as a high-quality alternative advanced e-diesel fuel.

- The e-jet fraction met the specifications for Jet A1, with the exception of the freezing point, which can be improved with the addition of an extra cyclization step in the process or with the use of freezing point improvers (additives).

- The blend of e-naphtha with fossil gasoline (at 10 v/v %) met almost all specifications, with the exclusion of the octane number; however, this drawback can be overcome with the use of some octane boosters or octane additives.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CERTH | Centre for Research & Technology Hellas |

| CFPP | Cold Filter Plugging Point |

| CPERI | Chemical Process & Energy Resources Institute |

| DCO | Decarboxylation/Decarbonylation |

| DMDS | Dimethyl Disulfide |

| DOS | Days On Stream |

| DP | Drop Pressure |

| FBP | Final Boiling Point |

| FFA | Free Fatty Acids |

| GC | Gas Chromatograph |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| HDN | Hydrodenitrogenation |

| HDO | Hydro-Deoxygenation |

| HDS | Hydrodesulfurization |

| HDT | Hydrotreatment |

| HTL | Hydrothermal Liquefaction |

| HVO | Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil |

| HVV | High Heating Value |

| I.D. | Inlet Diameter |

| IBP | Initial Boiling Point |

| LAGO | Light Atmospheric Gas Oil |

| LHSV | Liquid Hourly Space Velocity |

| MCR | Micro Carbon Residue |

| MSEP-A | Microseparometer rating |

| MTBE | Methyl Tert-Butyl Ether |

| NiMo | Nickel–Molybdenum Catalyst |

| SAF | Sustainable Aviation Fuels |

| SIM-DIS | Simulated Distillation |

| TAN | Total Acid Number |

| TBA | Tetra-Butyl-Amine |

| TCC | Thermochemical Conversion Technologies |

| TRL 3 | Technology Readiness Level 3 |

| TRL 5 | Technology Readiness Level 5 |

| ULSD | Ultra-Low-Sulfur Diesel |

| WCOs | Waste Cooking Oils |

| XRFS | X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometer |

References

- Concawe. Environmental Science for European Refining, Aramco. In E-Fuels: A Technoeconomic Assessment of European Domestic Production and Imports Towards (2050) Report No. 17/22; Concawe: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaik, B.P.; Misra, R.D. Effect of reaction pathway and operating parameters on the deoxygenation of vegetable oils to produce diesel range hydrocarbon fuels: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewtrakulchai, N.; Chanpee, S.; Jadsadajerm, S.; Wongrerkdee, S.; Manatura, K.; Eiad-Ua, A. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of polystyrene waste and maize stover combined with KOH activation to develop nanoporous carbon as catalyst support for catalytic hydrotreating of palm oil. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2024, 7, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezergianni, S.; Dimitriadis, A.; Chrysikou, L.P. Quality and sustainability comparison of one- vs. two-step catalytic hydroprocessing of waste cooking oil. Fuel 2014, 118, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Han, J.; Huang, Q.; Shen, H.; Lei, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, F. Catalytic Hydrodeoxygenation of Methyl Stearate and Microbial Lipids to Diesel-Range Alkanes over Pd/HPA-SiO2 Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 17440−17450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cabello, M.; García, I.; Papadaki, A.; Tsouko, E.; Koutinas, A.; Dorado, M. Biodiesel production using microbial lipids derived from food waste discarded by catering services. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Chrysikou, L.P.; Kokkalis, A.I.; Doufas, L.I.; Bezergianni, S. Animal fats valorization to green transportations fuels: From concept to industrially relevant scale validation. Waste Manag. 2022, 143, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galadima, A.; Masudi, A.; Muraza, O. Towards sustainable catalysts in hydrodeoxygenation of algae-derived oils: A critical review. Mol. Catal. 2022, 523, 112131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhao, B.; Tang, S.; Yang, X. Hydrotreating lipids for aviation biofuels derived from extraction of wet and dry algae. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, J.; Yang, C.; Qiu, Q.; Yan, Q.; Li, R.; Wang, B.; Wu, J.; Ding, Y. Recent Developments in Commercial Processes for Refining Bio-Feedstocks to Renewable Diesel. BioEnergy Res. 2018, 11, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Bertoa, R.; Kousoulidou, M.; Clairotte, M.; Giechaskiel, B.; Nuottimäki, J.; Sarjovaara, T.; Lonza, L. Impact of HVO blends on modern diesel passenger cars emissions during real world operation. Fuel 2019, 235, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarazi, Y.S.; Abu Talib, A.R.; Yu, J.; Gires, E.; Ghafir, M.F.A.; Lucas, J.; Yusaf, T. Effects of biofuel on engines performance and emission characteristics: A review. Energy 2022, 238, 121910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiong, M.C.; Chong, C.T.; Ng, J.-H.; Lam, S.S.; Tran, M.-V.; Chong, W.W.F.; Jaafar, M.N.M.; Valera-Medina, A. Liquid biofuels production and emissions performance in gas turbines: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 173, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mupondwa, E.; Tabil, L. Technoeconomic analysis of biojet fuel production from camelina at commercial scale: Case of Canadian Prairies. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, M.; Park, G.; Kim, E.; Song, H.; Jung, S.; Park, Y.-K.; Tsang, Y.F.; Lee, J.; Kwon, E.E. Chemicals and fuels from lipid-containing biomass: A comprehensive exploration. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 75, 108418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prussi, M.; Padella, M.; Konti, A.; Lonza, L. Advanced Alternative Fuels: Technolgy Development Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanatip, E.; Chansiriwat, W.; Palalerd, S.; Khunphonoi, R.; Kumsaen, T.; Wantala, K. Light biofuel production from waste cooking oil via pyrolytic catalysis cracking over modified Thai dolomite catalysts. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2022, 5, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN 14104; Fat and Oil Derivates–Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME)–Determination of Acid Value. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- CC 17-95; Soap in Oil, Titrimetric Method: The Titrimetric Method Determines the Alkalinity of the Test Sample as Sodium Oleate. AOCS: Champaign, IL, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D6304; Standard Test Method for Determination of Water in Petroleum Products, Lubricating Oils, and Additives by Coulometric Karl Fischer Titration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Kosma, I.; Bezergianni, S.; Chrysikou, L.P. Residual Lipids Pretreatment Towards Renewable Fuels. Energies 2025, 18, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D-4052; Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density, and API Gravity of Liquids by Digital Density Meter. Designation: D4052-22; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D-7169-23; Standard Test Method for Boiling Point Distribution of Samples with Residues such as Crude Oils and Atmospheric and Vacuum Residues by High Temperature Gas Chromatography. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D-5291; Standard Test Methods for Instrumental Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Nitrogen in Petroleum Products and Lubricants. Designation: D5291-21; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D-4294-21; Standard Test Method for Sulfur in Petroleum and Petroleum Products by Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D4629; Standard Test Method for Trace Nitrogen in Liquid Hydrocarbons by Syringe/Inlet Oxidative Combustion and Chemiluminescence Detection. Designation: D4629-17; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM E-203-16; Standard Test Method for Water Using Volumetric Karl Fischer Titration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM D-664; Standard Test Method for Acid Number of Petroleum Products by Potentiometric Titration. Designation: D664-18; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D-445-21; Standard Test Method for Kinematic Viscosity of Transparent and Opaque Liquids (and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D-976-06; Standard Test Method for Calculated Cetane Index of Distillate Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006.

- ASTM D-97; Standard Test Method for Pour Point of Petroleum Products. Designation: D97-02; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002.

- ASTM D4530; Standard Test Method for Determination of Carbon Residue (Micro Method). Designation: D4530-15 (Reapproved 2020); ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- SIST EN 116:2015; Diesel and Domestic Heating Fuels—Determination of Cold Filter Plugging Point—Stepwise Cooling Bath Method. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Channiwala, S.; Parikh, P. A unified correlation for estimating HHV of solid, liquid and gaseous fuels. Fuel 2002, 81, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Chrysikou, L.P.; Meletidis, G.; Terzis, G.; Auersvald, M.; Kubička, D.; Bezergianni, S. Bio-based refinery intermediate production via hydrodeoxygenation of fast pyrolysis bio-oil. Renew. Energy 2021, 168, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Bergvall, N.; Johansson, A.-C.; Sandström, L.; Bezergianni, S.; Tourlakidis, N.; Meca, L.; Kukula, P.; Raymakers, L. Biomass conversion via ablative fast pyrolysis and hydroprocessing towards refinery integration: Industrially relevant scale validation. Fuel 2023, 332, 126153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Remón, J.; Jiang, Z.; Matharu, A.S.; Hu, C. Tuning the selectivity of natural oils and fatty acids/esters deoxygenation to biofuels and fatty alcohols: A review. Green Energy Environ. 2023, 8, 722–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymann, P.A.; Lahiri, P. Co-Processing Renewables in a Hydrocracker; PTQ Catalysis; Digital Refining: Croydon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mäki-Arvela, P.; Martínez-Klimov, M.; Murzin, D.Y. Hydroconversion of fatty acids and vegetable oils for production of jet fuels. Fuel 2021, 306, 121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-K.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Wang, W.-C. The production of renewable aviation fuel from waste cooking oil. Part II: Catalytic hydro-cracking/isomerization of hydro-processed alkanes into jet fuel range products. Renew. Energy 2020, 157, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Zhang, A. Optimization of aviation kerosene from one-step hydrotreatment of catalytic Jatropha oil over SDBS-Pt/SAPO-11 by response surface methodology. Renew. Energy 2019, 139, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Wang, W.-C. Direct conversion of glyceride-based oil into renewable jet fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 132, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporan, E.; Edwards, T.; Shafer, L.; DeWitt, M.J.; Klingshirn, C.; Zabarnick, S.; West, Z.; Striebich, R.; Graham, J.; Klein, J. Chemical, Thermal Stability, Seal Swell, and Emissions Studies of Alternative Jet Fuels. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaev, M.; Landau, M.V.; Vidruk-Nehemya, R.; Koukouliev, V.; Zarchin, R.; Herskowitz, M. Conversion of vegetable oils on Pt/Al2O3/SAPO-11 to diesel and jet fuels containing aromatics. Fuel 2015, 161, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.H.; Reksowardojo, I.K.; Soerawidjaja, T.H.; Pham, D.N.; Fujita, O. The sooting tendency of aviation biofuels and jet range paraffins: Effects of adding aromatics, carbon chain length of normal paraffins, and fraction of branched paraffins. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2018, 190, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7566-22; Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuel Containing Synthesized Hydrocarbons. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- EN 590:2009; Automotive Fuels—Diesel-Requirements and Test Methods. BSI: London, UK, 2009. Available online: http://www.envirochem.hu/www.envirochem.hu/documents/EN_590_2009_hhV05.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Zhang, K.; Hu, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhao, G.; Ren, L.; Nie, H.; Han, W. Hydrocarbon-conversion reaction and new paraffin-kinetic model during straight-run gas oil (SRGO) hydrotreating. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2024, 2, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Long, F.; Jiang, J.; Li, F.; Zhai, Q.; Wang, F.; Liu, P.; Li, J. Integrated catalytic conversion of waste triglycerides to liquid hydrocarbons for aviation biofuels. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, D.; Haider, M.S.; Rosendahl, L.A. Catalytic upgrading of hydrothermal liquefaction biocrudes: Different challenges for different feedstocks. Renew. Energy 2019, 141, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier, S.; Alkilde, O.F.; Chopra, R.; Gabrielsen, J.; Grubb, M. Hydroprocessing of Renewable Feedstocks—Challenges and Solutions; Haldor Topsoe: Lyngby, Denmark, 2020; Available online: https://info.topsoe.com/hubfs/kp-assets/0306.2019_RBU_Hydroprocessing%20of%20renewable%20feedstocks_A4_White_Paper_Lay2_Rev0.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Kim, M.Y.; Kim, J.-K.; Lee, M.-E.; Lee, S.; Choi, M. Maximizing Biojet Fuel Production from Triglyceride: Importance of the Hydrocracking Catalyst and Separate Deoxygenation/Hydrocracking Steps. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 6256–6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Why, E.S.K.; Ong, H.C.; Lee, H.V.; Chen, W.-H.; Asikin-Mijan, N.; Varman, M. Conversion of bio-jet fuel from palm kernel oil and its blending effect with jet A-1 fuel. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 243, 11431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Seljak, T.; Vihar, R.; Baškovič, U.Ž.; Dimaratos, A.; Bezergianni, S.; Samaras, Z.; Katrašnik, T. Improving PM-NOx trade-off with paraffinic fuels: A study towards diesel engine optimization with HVO. Fuel 2020, 265, 116921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Clean Transportation. The European Commission’s Renewable Energy Proposal for 2030; International Council on Clean Transportation: Washinton, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 12185:2024; Crude Petroleum, Petroleum Products and Related Products—Determination of Density—Laboratory Density Meter with an Oscillating U-Tube Sensor. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 2719:2016; Determination of Flash Point—Pensky-Martens Closed Cup Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 20846:2019; Petroleum Products—Determination of Sulfur Content of Automotive Fuels—Ultraviolet Fluorescence Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 3104:2020; Petroleum Products—Transparent and Opaque Liquids—Determination of Kinematic Viscosity and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 4264:2018; Petroleum Products—Calculation of Cetane Index of Middle-Distillate Fuels by the Four-Variable Equation. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 5165:2020; Petroleum Products—Determination of the Ignition Quality of Diesel Fuels—Cetane Engine Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 10370:2014; Petroleum Products—Determination of Carbon Residue—Micro Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 2160:1998; Petroleum Products—Corrosiveness to Copper—Copper Strip Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- ISO 12937:2000; Petroleum Products—Determination of Water—Coulometric Karl Fischer Titration Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- ISO 6245:2001; Petroleum Products—Determination of Ash. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- SIST EN 12662-1:2024; Liquid Petroleum Products—Determination of Total Contamination—Part 1: Middle Distillates and Diesel Fuels. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- SIST EN 15751:2014; Automotive Fuels—Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Fuel and Blends with Diesel Fuel—Determination of Oxidation Stability by Accelerated Oxidation Method. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- EN 12916:2019/prA1; Petroleum Products—Determination of Aromatic Hydrocarbon Types in Middle Distillates—High Performance Liquid Chromatography Method with Refractive Index Detection. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- ISO 12156-1:2023; Diesel Fuel—Assessment of Lubricity Using the High-Frequency Reciprocating Rig (HFRR) Part 1: Test Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 3405:2019; Petroleum and Related Products from Natural or Synthetic Sources—Determination of Distillation Characteristics at Atmospheric Pressure. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ASTM D86-23ae2; Standard Test Method for Distillation of Petroleum Products and Liquid Fuels at Atmospheric Pressure. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D156-23; Standard Test Method for Saybolt Color of Petroleum Products (Saybolt Chromometer Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D56-21a; Standard Test Method for Flash Point by Tag Closed Cup Tester. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D130-19; Standard Test Method for Corrosiveness to Copper from Petroleum Products by Copper Strip Test. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D3243-77; Method of Test for Flash-Point of Aviation Turbine Fuels by Setaflash Closed Tester. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1977.

- ASTM D3277-95e1; Standard Test Methods for Moisture Content of Oil-Impregnated Cellulosic Insulation. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D381-22; Standard Test Method for Gum Content in Fuels by Jet Evaporation. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D1319-20a; Standard Test Method for Hydrocarbon Types in Liquid Petroleum Products by Fluorescent Indicator Adsorption. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D3338/D3338M-20a; Standard Test Method for Estimation of Net Heat of Combustion of Aviation Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D2386-19; Standard Test Method for Freezing Point of Aviation Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D1322-22; Standard Test Method for Smoke Point of Kerosene and Aviation Turbine Fuel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D3241-20c; Standard Test Method for Thermal Oxidation Stability of Aviation Turbine Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D1840-22; Standard Test Method for Naphthalene Hydrocarbons in Aviation Turbine Fuels by Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D3948-22; Standard Test Method for Determining Water Separation Characteristics of Aviation Turbine Fuels by Portable Separometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D2624-22; Standard Test Methods for Electrical Conductivity of Aviation and Distillate Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D5452-20; Standard Test Method for Particulate Contamination in Aviation Fuels by Laboratory Filtration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Method IP 565; Determination of the Level of Cleanliness of Aviation Turbine Fuel—Portable Automatic Particle Counter Method. Method adopted/last revised. Energy Institute: London, UK, 2013.

- ISO 4406; Hydraulic Fluid Power—Fluids—Method for Coding the Level of Contamination by Solid Particles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- EN 228:2008; Automotive Fuels—Unleaded petrol—Requirements and Test Methods. BSI: London, UK, 2008. Available online: http://www.envirochem.hu/www.envirochem.hu/documents/EN_228_benzin_JBg37.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Xiang, H.; Xin, R.; Prasongthum, N.; Natewong, P.; Sooknoi, T.; Wang, J.; Reubroycharoen, P.; Fan, X. Catalytic conversion of bioethanol to value-added chemicals and fuels: A review. Resour. Chem. Mater. 2022, 1, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIST EN 13016-1:2024; Liquid Petroleum Products—Vapour Pressure—Part 1: Determination of Air Saturated Vapour Pressure (ASVP) and Calculated Dry Vapour Pressure Equivalent (DVPE). CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- ISO 5164:2014; Petroleum Products—Determination of Knock Characteristics of Motor Fuels—Research Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 5163:2014; Petroleum Products—Determination of Knock Characteristics of Motor and Aviation Fuels—Motor Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 6246:2017; Petroleum Products—Gum Content of Fuels—Jet Evaporation Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 22854:2021; Liquid Petroleum Products—Determination of Hydrocarbon Types and Oxygenates in Automotive-Motor Gasoline and in Ethanol (E85) Automotive Fuel—Multidimensional Gas Chromatography Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitriadis, A.; Chrysikou, L.P.; Kosma, I.; Georgantas, D.; Nanaki, E.; Anatolaki, C.; Kiartzis, S.; Bezergianni, S. Naphtha Production via Catalytic Hydrotreatment of Refined Residual Lipids: Validation in Industrially Relevant Scale. Energies 2025, 18, 6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246586

Dimitriadis A, Chrysikou LP, Kosma I, Georgantas D, Nanaki E, Anatolaki C, Kiartzis S, Bezergianni S. Naphtha Production via Catalytic Hydrotreatment of Refined Residual Lipids: Validation in Industrially Relevant Scale. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246586

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitriadis, Athanasios, Loukia P. Chrysikou, Ioanna Kosma, Dimitrios Georgantas, Evanthia Nanaki, Chrysa Anatolaki, Spyros Kiartzis, and Stella Bezergianni. 2025. "Naphtha Production via Catalytic Hydrotreatment of Refined Residual Lipids: Validation in Industrially Relevant Scale" Energies 18, no. 24: 6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246586

APA StyleDimitriadis, A., Chrysikou, L. P., Kosma, I., Georgantas, D., Nanaki, E., Anatolaki, C., Kiartzis, S., & Bezergianni, S. (2025). Naphtha Production via Catalytic Hydrotreatment of Refined Residual Lipids: Validation in Industrially Relevant Scale. Energies, 18(24), 6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246586