1. Introduction

The increasing penetration of variable renewable energy sources—such as wind and solar—has intensified the need for operational flexibility to ensure power system stability. To balance real-time fluctuations in supply and demand, grid operators are increasingly turning to demand-side resources. Among these, industrial electricity consumers represent a promising, yet underutilized, source of flexibility. Energy-intensive sectors with partially controllable processes—such as cement manufacturing—are particularly well-positioned to contribute to this effort while pursuing energy cost reductions and decarbonization goals.

The cement industry alone accounts for 7–8% of global anthropogenic CO

2 emissions and nearly 7% of global industrial energy use [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Within the production chain, subsystems such as raw milling exhibit intrinsic flexibility due to their decoupling from the continuous kiln operation via intermediate silos. However, leveraging this potential in practice requires advanced decision-support tools capable of reconciling operational constraints with the volatility of electricity markets.

While demand-side response programs offer a framework for incentivizing flexible industrial consumption, their implementation in continuous-flow environments remains challenging. Production schedules must satisfy strict requirements, including minimum machine uptime/downtime, inventory management, and uninterrupted material flow. Optimization-based methods are essential for identifying technically feasible and economically attractive scheduling adjustments.

This study proposes a two-stage mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) framework to support market-responsive scheduling in cement manufacturing. The first stage determines a cost-optimal production schedule for the raw milling subsystem using day-ahead electricity prices. The second stage evaluates deviations from this baseline to provide upward and downward reserve capacity in Spain’s tertiary regulation market (manual Frequency Restoration Reserve, mFRR).

The methodology is validated through a real-world case study of a Spanish Portland cement plant. Using actual operational data and electricity market prices from 2023, the framework analyzes 19 asset configurations that combine photovoltaic generation and battery energy storage systems. The results quantify potential electricity cost savings, flexibility revenues, and investment payback times.

Beyond cost savings, unlocking this industrial flexibility generates significant social and systemic value. The literature highlights the “Merit Order Effect” of demand response: active industrial participation displaces expensive marginal generators—typically thermal units—thereby reducing the market clearing price for all consumers [

5]. Furthermore, energy-intensive industries can provide substantial tertiary reserve capacity, avoiding the startup of open-cycle gas turbines and deferring grid investment costs [

6]. In high-renewable scenarios, shifting consumption is essential to reduce curtailment [

7] and avoids emissions associated with fossil-fuel-based balancing, with potential reductions of up to 188 tons of CO

2/day observed in similar industrial contexts [

8]. Thus, the proposed framework validates a dual-value proposition: economic efficiency for the industry and decarbonization support for the grid.

In view of these challenges and opportunities, this study makes the following contributions:

A two-stage MILP framework integrating cost-optimal production scheduling with short-term flexibility valuation under real market signals.

A techno-economic assessment of 19 PV and BESS configurations, quantifying cost savings, flexibility revenues, and simple payback periods.

Operational guidance for industrial stakeholders on monetizing demand-side flexibility with minimal disruption to production processes.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on industrial demand-side flexibility, with a focus on the cement sector.

Section 3 introduces the case study context.

Section 4 presents the two-stage optimization framework.

Section 5 describes the simulation setup.

Section 6 discusses the results, and

Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Literature Review

Industrial demand-side response (DSR) is increasingly recognized as a critical enabler of power system flexibility, with heavy industrial loads identified as a dominant source of technical potential [

9,

10]. Numerous optimization-based approaches—including heuristics, model predictive control, and mathematical programming—have been developed to align industrial consumption with market signals while ensuring operational feasibility [

11,

12]. Recent meta-analyses indicate that industrial sites equipped with batteries significantly outperform residential ones in up-regulation success rates [

13], while specific case studies, such as those by Zahari et al. [

14], demonstrate that implementing demand response strategies like peak shaving via hybrid solar PV and BESS in food manufacturing can significantly optimize energy use and sustainability.

While this study focuses on centralized optimization strategies, the recent literature has also explored decentralized frameworks using game theory and evolutionary game theory to manage the complexity of renewable integration [

15]. These approaches address challenges in generation planning, bidding strategies, and demand response by modeling dynamic interactions and strategy evolution via Stackelberg games or replicator dynamics. Such multi-agent perspectives offer valuable insights into market equilibrium, complementing the facility-centric view of centralized scheduling.

Narrowing the focus to the cement sector, manufacturing processes present significant short-term flexibility potential due to their high energy intensity and modularity. Specifically, raw milling and grinding stages are decoupled from the continuous kiln operation through intermediate silos, enabling load shifting and schedule rescheduling [

16,

17]. Building on this foundation, Rombouts [

18] demonstrated that 24% of electricity use is shiftable in a european cement plant, though flexibility was not financially monetized in their analysis. Parejo-Guzmán et al. [

19] achieved an 11% reduction in energy costs for Spanish clinker production using genetic algorithms, while Lu et al. [

20] showed that coupling onsite PV with battery storage and load flexibility in heavy industries, such as cement plants, could reduce electricity costs by up to 80% while achieving 100% renewable energy integration. Zhang and Parisio [

21] developed a distributed MILP-based model predictive control (MPC) to coordinate flexible assets for providing flexibility services to distribution networks.

Despite these advances, the practical implementation of MPC and advanced scheduling in complex industrial environments faces persistent challenges documented in recent literature. Key barriers include the complexity of integrating production scheduling with mixed continuous-discrete dynamics and a lack of validation in specialized industrial setups [

22,

23,

24]. Furthermore, high computational costs often hinder real-time performance for large-scale problems, while the strict requirement for continuous high-quality data and model validation remains a significant operational hurdle [

22,

25]. Additionally, few studies jointly optimize production schedules and flexibility participation under real-time electricity market signals, often overlooking the synergy between production planning and storage assets.

To address these gaps, this study proposes a two-stage MILP framework that explicitly couples the non-linear operational constraints of raw milling—such as minimum up/down times and silo inventory buffering—with the specific fast-response requirements of the Spanish mFRR market (12.5-min activation time and marginal pricing) [

26]. Unlike generic control approaches, this formulation isolates the synergistic value of co-optimizing heavy industrial loads with BESS, demonstrating how storage assets unlock balancing market participation that is otherwise technically challenging for standalone mills due to ramping limits. By quantifying the cost of deviating from a cost-optimal baseline and comparing it to expected revenues, the framework offers an actionable methodology for integrating industrial flexibility into power system operations.

3. Industrial Context and Problem Description

This section situates the proposed optimization framework within the operational context of a real Portland cement manufacturing facility in Spain. It outlines the production process, identifies subsystems relevant to energy flexibility, introduces the energy assets under consideration, and clarifies the optimization objectives and market setting. Together, these elements define the scope and practical relevance of the study.

3.1. Overview of the Cement Manufacturing Process

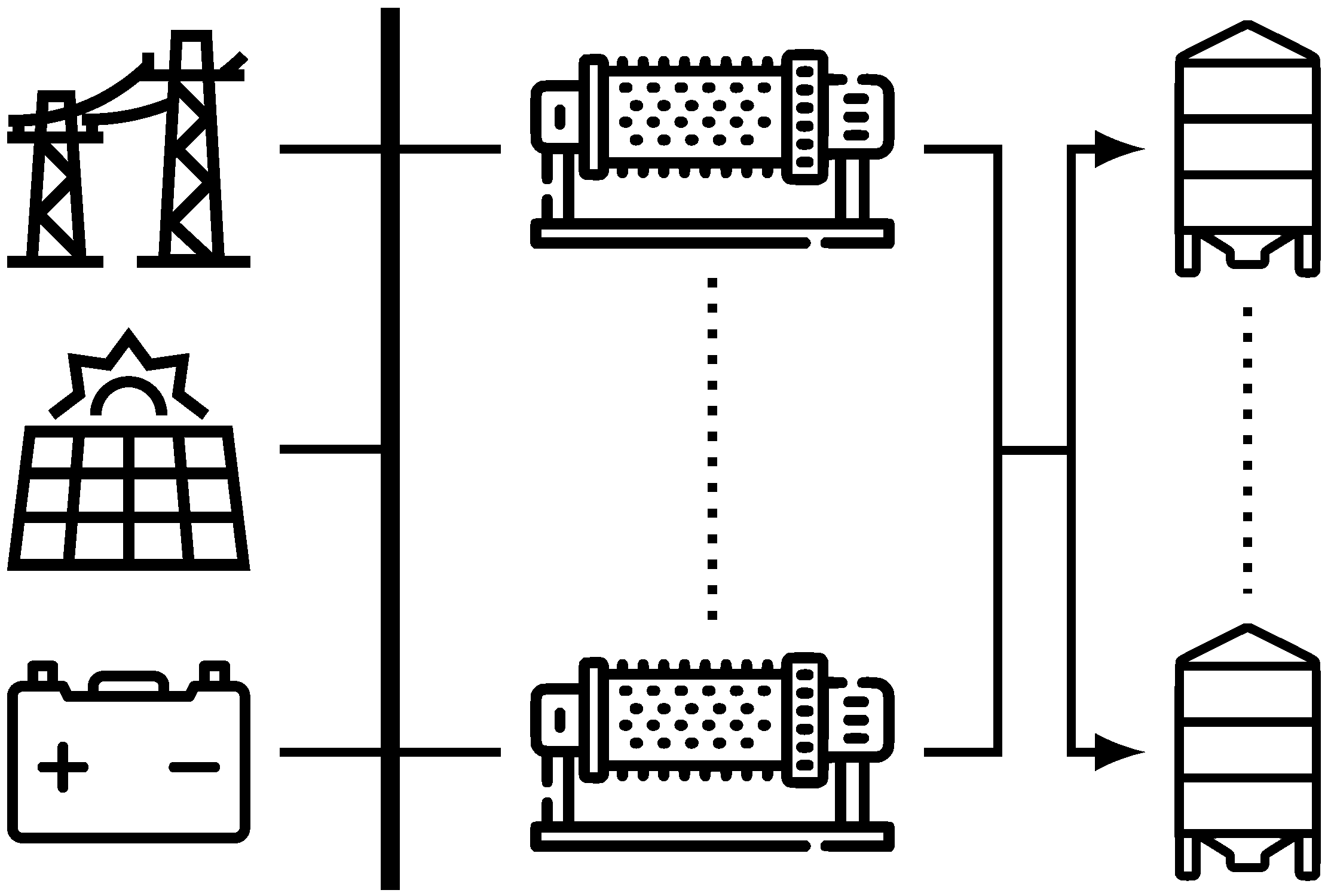

Portland cement production is a highly energy-intensive process comprising two main stages: (i) clinker production and (ii) cement grinding. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the clinker production stage involves the extraction and processing of raw materials (primarily limestone and clay), which are crushed, dried, and finely ground into a homogeneous raw meal. This meal is temporarily stored in silos before being fed to the kiln, where it is sintered at temperatures between 1400 °C to 1500 °C [

27] to form clinker. The hot clinker is then cooled and stored.

In the second stage, the clinker is mixed with gypsum and other additives and ground into cement with the desired physical and chemical properties. The final product is stored in silos for subsequent distribution.

3.2. Identifying Flexibility Potential

While thermal energy dominates the kiln process, electricity is the critical energy carrier for the grinding subsystem. Energy costs can represent 30–40% of total production costs in cement manufacturing [

8], with the milling stage accounting for approximately 35–40% of total electricity consumption [

16]. In European markets, cement mills have been identified as prime candidates for Demand-Side Management due to their high specific electricity costs relative to gross value added [

6], making even marginal efficiency gains financially significant.

Within this context, the raw meal preparation stage—highlighted in

Figure 1—offers the greatest potential for operational flexibility. This subsystem accounts for approximately 30% to 35% of total site electricity consumption and is effectively decoupled from the continuous kiln operation via an intermediate storage silo.

In contrast, the kiln must operate continuously under stringent thermal conditions, leaving limited flexibility. Similarly, the cement grinding phase is constrained by limited storage capacity and volatile product demand, making it less suitable for short-term rescheduling.

3.3. Energy Assets and Infrastructure Considered

This study models the following key infrastructure components within the raw meal preparation stage:

Raw Mill: A single mill with a rated power of 6 , operating in binary on/off states. It represents the facility’s principal flexible electrical load and is part of the existing infrastructure.

Raw Meal Silo: A large silo with a storage capacity of 15,000 t, enabling temporal decoupling between raw meal production and kiln feeding.

Prospective PV and Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS): Several hypothetical configurations of on-site photovoltaic generation and battery storage are introduced for techno-economic evaluation. These range from 1 to 6 (or 6 ) and, although not currently installed, they are assessed to explore their potential for enhancing operational flexibility and reducing electricity costs.

Together, these components support a comprehensive evaluation of strategies combining load scheduling, storage dispatch, and renewable energy integration.

3.4. Optimization Goals and Scope

The analysis adopts a two-stage optimization framework implemented over a rolling time horizon ranging from 24 to 168 h, with an hourly resolution. The primary decision variables include:

Mill Operation: Binary scheduling of the raw mill’s on/off status.

Silo Inventory Management: Balancing of raw meal stocks to buffer production and demand.

PV and BESS Dispatch: Hourly control of battery charging/discharging and allocation of PV generation between self-consumption and grid import.

These decisions are evaluated in two consecutive stages:

Stage 1—Cost Minimization: Determines a baseline production schedule that minimizes electricity costs using day-ahead prices, while satisfying all technical and operational constraints. This stage represents standard energy-aware scheduling from a price-taker perspective.

Stage 2—Flexibility Evaluation: Starting from the baseline, this stage quantifies the cost of offering load flexibility (e.g., MW at time ) to Spain’s tertiary regulation market (mFRR). It identifies feasible deviations that preserve production reliability and estimates the net economic gain from balancing market revenues relative to the additional cost incurred.

This dual-stage formulation enables the plant to remain operationally robust while dynamically capturing short-term market opportunities.

3.5. Balancing Market Context

Spain’s electricity market is structured into several layers, including long-term forward contracts, the day-ahead and intra-day spot markets, and ancillary services markets. Balancing services are further divided into three categories: primary (frequency containment reserve, FCR), secondary (automatic frequency restoration reserve, aFRR), and tertiary (manual frequency restoration reserve, mFRR) regulation [

28].

This study specifically targets the mFRR segment, which is governed in Spain by Operating Procedure (P.O.) 7.3 [

26]. Unlike automatic reserves, mFRR is manually activated, making it particularly suitable for industrial loads that require a brief lead time to adjust setpoints. The regulation mandates a Full Activation Time (FAT) of 12.5 min and a minimum bid size of 1 MW [

26]. These technical requirements are compatible with the fast-ramping capabilities of raw mills and battery storage systems, offering a practical window for rescheduling production or shifting loads.

Economically, the market operates on a marginal pricing scheme (pay-as-cleared), where activated energy is remunerated at the marginal price of the corresponding quarter-hour period. While the current analysis focuses on the Spanish context, the national system is in the process of integrating into the European MARI platform (Manually Activated Reserves Initiative). This transition will standardize products and allow Spanish industrial flexibility to compete cross-border [

26], reinforcing the scalability and future relevance of the proposed flexibility model beyond local regulatory specifics.

By aligning the physical flexibility of the raw mill with these standard operational requirements of the mFRR market, the proposed methodology establishes a viable path for industrial facilities to participate in electricity markets beyond traditional procurement—enhancing both economic performance and grid reliability.

With the industrial and market context established, the next section formalizes the optimization models used in the two-stage methodology.

4. Methodology

This section presents the methodological framework developed to identify, quantify, and monetize short-term flexibility in the operation of a cement plant. The approach is structured into two sequential stages. Stage 1 computes an optimal production schedule that minimizes electricity procurement costs under technical and operational constraints. Stage 2 assesses the economic viability of deviating from this baseline schedule to provide flexibility services in the electricity balancing market. Both stages are formulated as mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problems.

4.1. Stage 1—Optimal Production Scheduling

Stage 1 determines a cost-optimal baseline schedule for the raw milling subsystem of the plant. This schedule serves as the reference for evaluating market-responsive flexibility in Stage 2. All inputs—including day-ahead electricity prices, photovoltaic (PV) generation forecasts, and process demand—are treated as deterministic. Although stochastic formulations are relevant, they are considered outside the scope of this study.

The MILP is solved over a rolling planning horizon with hourly resolution, allowing for dynamic adjustments in response to updated forecasts or operational data.

4.1.1. System Scope

Figure 2 illustrates the modeled subsystem, which includes raw mills, silos, PV installations, battery energy storage systems (BESS), and a connection to the public grid. Although the case study focuses on a single unit of each component, the model is general and scalable to multi-unit configurations. The optimization goal is to satisfy kiln demand

at each time step while minimizing electricity purchases from the grid.

4.1.2. Model Components

Index Sets:

: Time periods in the planning horizon (e.g., hourly), with step size .

: Set of raw milling units.

Key Parameters:

[€/MWh]: Day-ahead electricity price.

[MW]: Forecasted PV generation at time t.

[MW], [t/h]: Rated power and throughput of mill k.

[t]: Inventory bounds for silo connected to mill k.

[MWh]: BESS energy capacity.

[MW]: BESS maximum charging and discharging rates.

[h]: Minimum on/off durations for mill k.

[MW]: Maximum grid import capacity.

4.1.3. Objective Function

The optimization objective is to minimize electricity procurement costs from the grid:

Only grid purchases contribute to the cost function. PV generation and battery discharges are considered free; grid exports do not yield revenue in this formulation.

4.1.4. Constraints

Unless otherwise noted, all constraints apply to each time step and each mill .

- (1)

Silo material balance:

This equation governs inventory evolution. When mill k is active, it produces material at a rate , which is added to the silo. At the same time, material is withdrawn from the silo to meet the process demand .

- (2)

Power balance:

This constraint ensures that total power supply—comprising grid import, battery discharge, and PV generation—matches consumption, which includes grid export, battery charging, and mill operation.

- (3)

Silo inventory limits:

Each silo must operate within its defined storage capacity bounds to preserve material buffering and avoid overflow or depletion.

- (4)

Demand coverage:

This constraint guarantees that the cumulative inventory across all silos is sufficient to meet the hourly kiln demand . If needed, the total demand can be disaggregated across mills as .

- (5)

Battery dynamics and operating limits:

The state of charge (SOC) evolves based on the net energy flow. Constraint (6b) ensures that the SOC remains within the usable energy window, considering a minimum depth of discharge (DoD). Power limits constrain instantaneous charging and discharging capabilities. The initial condition is:

- (6)

Grid import limit:

This constraint enforces the grid connection’s maximum import capacity, preventing overload.

- (7)

Minimum mill uptime and downtime:

These constraints ensure that once a mill is turned on (or off), it must remain in that state for a minimum number of consecutive hours, reducing wear and tear and reflecting operational stability requirements.

4.1.5. Solution and Interpretation

The MILP defined by (1)–(8) is solved using commercial (e.g., Gurobi) or open-source (e.g., SCIP) solvers. The output is a cost-optimal baseline schedule:

with associated total electricity cost

. This solution serves as input to the flexibility optimization in Stage 2.

Table 1 summarizes all key symbols used in the Stage 1 formulation.

4.2. Stage 2—Flexibility Evaluation

The second stage evaluates whether the cement plant can profitably deviate from its cost-optimal baseline schedule in order to provide short-term flexibility in the Spanish tertiary regulation market (manual Frequency Restoration Reserve, mFRR). This is achieved by simulating enforced load deviations and quantifying the tradeoff between balancing market revenue and the cost of deviating from the baseline.

Table 2 summarizes the notation specific to this flexibility evaluation model.

4.2.1. Conceptual Overview

Flexibility is modeled as a forced, single-period deviation at a specific activation time . A power shift is imposed: positive for upward regulation (load reduction), negative for downward regulation (load increase). The optimization problem is then re-solved for the remaining time horizon, subject to technical feasibility and energy neutrality constraints.

4.2.2. Modified Constraints

The Stage 2 model inherits all structural constraints from Stage 1, with the following modifications to reflect the activation of flexibility:

Frozen pre-activation decisions: For all periods

, key variables are fixed to their baseline values:

This ensures that the past operational history is preserved and only post- behavior is re-optimized.

Enforced deviation at activation: At time

, the grid import is modified relative to the baseline:

Energy neutrality: Over the full horizon, total energy imported from the grid must remain close to the baseline value

, within symmetric or asymmetric tolerance bounds:

This prevents unrealistic net load shifts across the planning period and ensures alignment with physical energy use.

Unlike pre- variables, post- mill operating hours and inventory trajectories are allowed to adjust in order to recover from the deviation, as long as all constraints remain satisfied.

4.2.3. Flexibility Cost and Profitability

The cost of the re-optimized schedule under deviation is denoted

, and the flexibility cost is:

A flexibility offer is profitable if the revenue earned in the mFRR market exceeds the incurred cost:

where

is the market clearing price for upward (

) or downward (

) reserve.

The corresponding break-even spread is given by:

This metric provides a useful benchmark—market prices above this spread indicate profitable transactions.

4.2.4. Implementation Workflow

The flexibility assessment is implemented over a rolling horizon and multiple scenarios, following this process:

Select candidate activation times and deviation values for simulation.

For each pair:

Fix pre- variables to baseline values.

Enforce the deviation at time .

Re-solve the MILP for the remaining horizon.

Compute the flexibility cost .

Compare the result with expected mFRR prices to determine profitability.

This second stage complements the baseline scheduling developed in Stage 1 by enabling economically rational and technically feasible participation in balancing markets. The following section applies the full methodology to a real-world cement manufacturing facility in Spain.

5. Case Study—Application to a Spanish Portland Cement Plant

This section demonstrates the practical application of the proposed methodology to a medium-sized Portland cement plant in Spain. The analysis draws on real operational data, electricity market prices, and technical parameters provided by the plant operator and project collaborators. The objective is to assess the techno-economic potential of flexibility using the two-stage optimization framework outlined in

Section 4.

The section is organized as follows. First, we describe the energy-relevant infrastructure of the facility. Then, we introduce the input data and scenario matrix, along with the rationale for selecting two representative months from 2023. Finally, we present the simulation design and evaluation approach.

5.1. Plant Description

The facility operates a single raw milling line that consumes approximately 6 MW of electricity when running at full capacity. At this load, the mill produces raw meal at a rate of 360 t/h. Milled material is stored in a silo with a total capacity of 15,000 t, and a minimum inventory threshold of 9000 t is maintained to ensure at least six hours of uninterrupted kiln feeding during mill downtime.

While the plant currently relies exclusively on grid electricity, it is actively evaluating the integration of on-site generation and storage technologies to enhance operational flexibility and reduce energy costs. Specifically, two technology types are considered:

Photovoltaic (PV) array: Ground-mounted, with installed capacities ranging from 1 to 6 MWp.

Battery Energy Storage System (BESS): Lithium-ion systems with capacities from 1 to 6 MWh, rated at 1C with an 80% usable depth-of-discharge.

All scenarios respect the plant’s contracted maximum grid import limit of 21 MW.

5.2. Data Sources

The simulation relies on real-world input data from the following sources:

Day-ahead prices (

): Hourly electricity prices for April and June 2023 from the OMIE market. To replicate real-world operational conditions within the rolling horizon strategy, the immediate 24-h window utilizes realized market prices (as they are deterministically known at the time of decision-making), whereas the extended planning horizon relies on price forecasts generated by Fortia’s proprietary algorithm [

29] to optimize long-term inventory management.

Balancing market prices (): Upward and downward mFRR clearing prices published by Red Eléctrica de España (REE).

PV generation (): Estimated using clear-sky irradiance data from the PVGIS database, based on the plant’s geographical coordinates.

Process demand and constraints: The kiln requires a relatively stable raw meal supply of 240 t/h, with values and constraints confirmed by plant personnel.

All time series are synchronized to Central European Time (UTC + 1) to avoid discontinuities due to daylight saving changes.

5.3. Scenario Matrix

A total of 19 technology configurations are simulated, including the current setup without PV or BESS. Each scenario is labeled MXY, where X denotes photovoltaic (PV) capacity in megawatts peak (MWp), and Y denotes battery energy storage system (BESS) capacity in megawatt-hours (MWh). The matrix encompasses PV-only, BESS-only, and combined PV + BESS configurations.

To limit model complexity while capturing scale effects, only matched PV + BESS combinations (M11, M22, …, M66) were simulated, representing balanced deployments of generation and storage.

The full set of simulated configurations is summarized in

Table 3, which also describes the purpose and classification of each scenario type.

5.4. Simulation Design

5.4.1. Planning Horizon and Rolling Strategy

Each simulation spans a 30-day period in either April or June 2023, using hourly resolution. A rolling-horizon implementation is applied to reflect realistic plant operations and market participation:

At midnight each day, Stage 1 computes a 7-day (168-h) baseline schedule based on updated forecasts.

Stage 2 evaluates flexibility transactions for the first 24 h of that window, testing MW.

The planning horizon then advances by one day, and the procedure repeats.

5.4.2. Solver and Computation Time

All models are implemented in PySCIPOpt 4.3.0 [

30,

31] and solved using

SCIP 8.0.3 with default settings. Average runtimes were:

In total, over 4250 MILP instances were solved across all scenario-month combinations, with an aggregate runtime of approximately 3.3 h.

With the case study design and assumptions established, the next section presents the results of the simulations and discusses key operational and economic insights across the tested configurations.

6. Results and Discussion

This section presents the numerical results of applying the two-stage baseline-and-flexibility framework to the Spanish cement plant. It evaluates the model’s outputs across several dimensions, providing a comprehensive picture of flexibility performance, techno-economic impact, and investment viability.

The discussion is structured into five parts: (1) illustrative examples of flexibility transactions, (2) aggregated economic performance, (3) availability of flexible hours and success rates, (4) electricity cost savings from asset-driven scheduling, and (5) investment payback period estimates.

6.1. Illustrative Flexibility Transactions

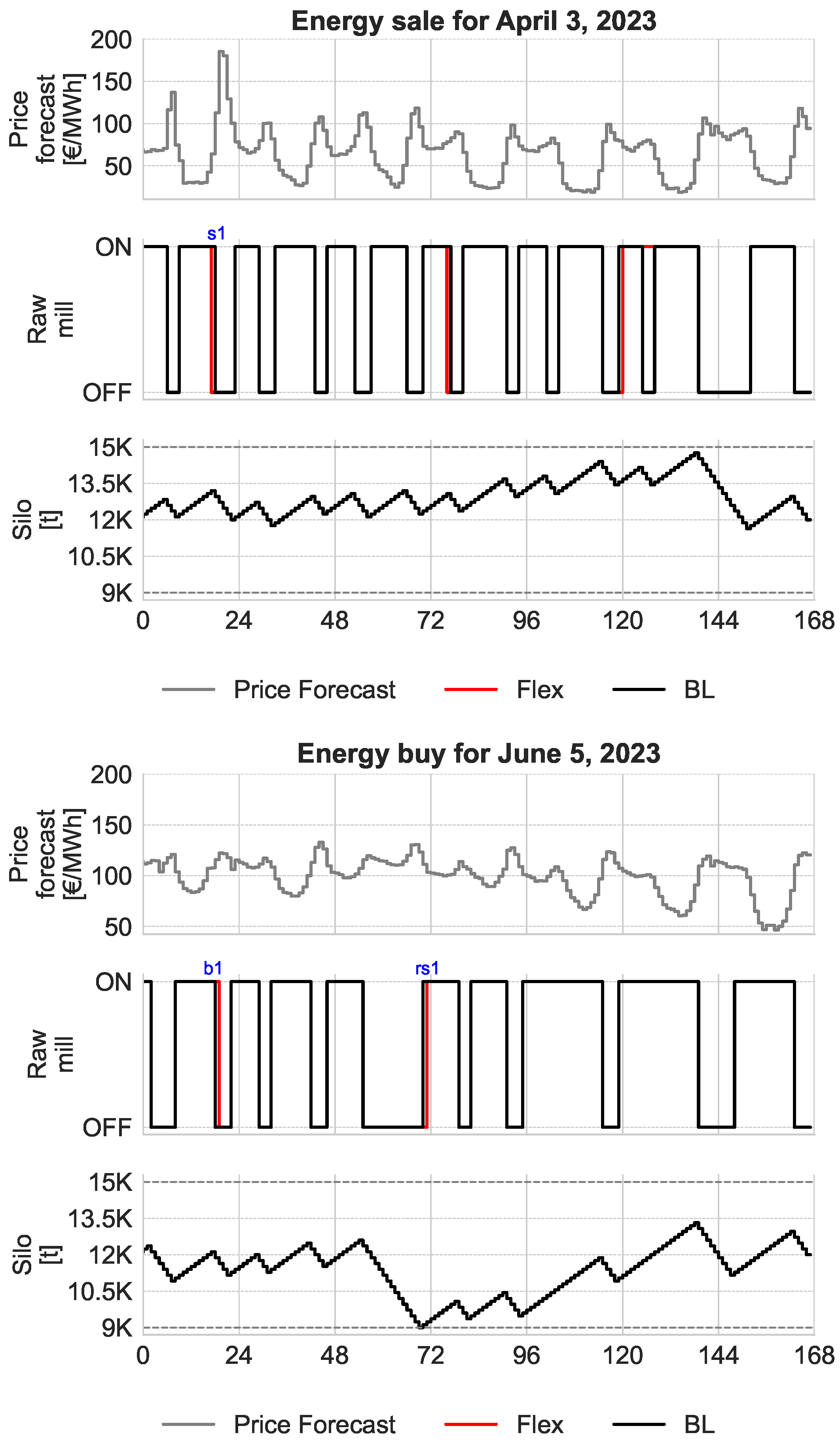

To demonstrate how the methodology operates in practice,

Figure 4 shows two representative examples where the model identifies profitable deviations from the baseline schedule. These reflect actual market opportunities in April and June 2023.

In the first case (top), the mill temporarily reduces load in response to a tertiary market (mFRR up) signal, capitalizing on a high price spread between the day-ahead and balancing markets. In the second (bottom), it increases consumption during a period of system overgeneration, helping the grid absorb excess supply at low cost.

Each plot consists of three layers: forecasted day-ahead prices (top), raw mill status (middle), and silo inventory (bottom). Notably, the flexibility actions are placed at the edges of production blocks, minimizing disruption to process continuity and respecting minimum uptime/downtime constraints.

In both cases, profitability hinges on whether the marginal revenue (or savings) exceeds the operational cost of deviating from the optimized schedule. This is reflected in the

Table 4 and

Table 5.

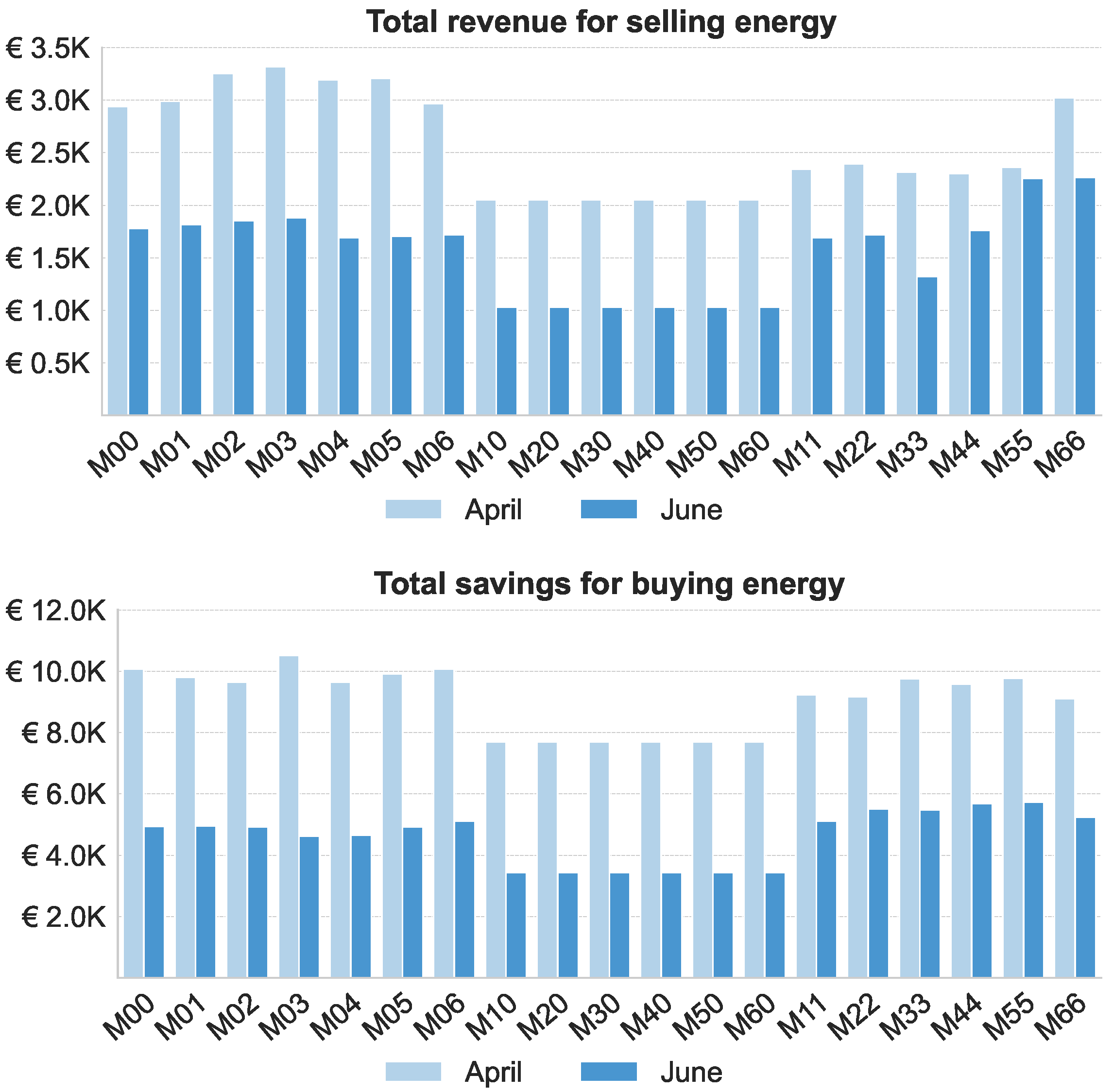

6.2. Aggregate Economic Performance

Figure 5 aggregates monthly revenues from all profitable flexibility transactions, by scenario and market direction.

Downward regulation (buying electricity) is consistently more profitable than upward regulation. This reflects both the frequency of activation and the magnitude of price spreads—particularly during midday PV overgeneration.

Battery-enhanced scenarios achieve higher revenues than PV-only cases, since BESS enable time-shifting and fast response to market events.

April outperforms June, demonstrating the influence of market seasonality on flexibility value.

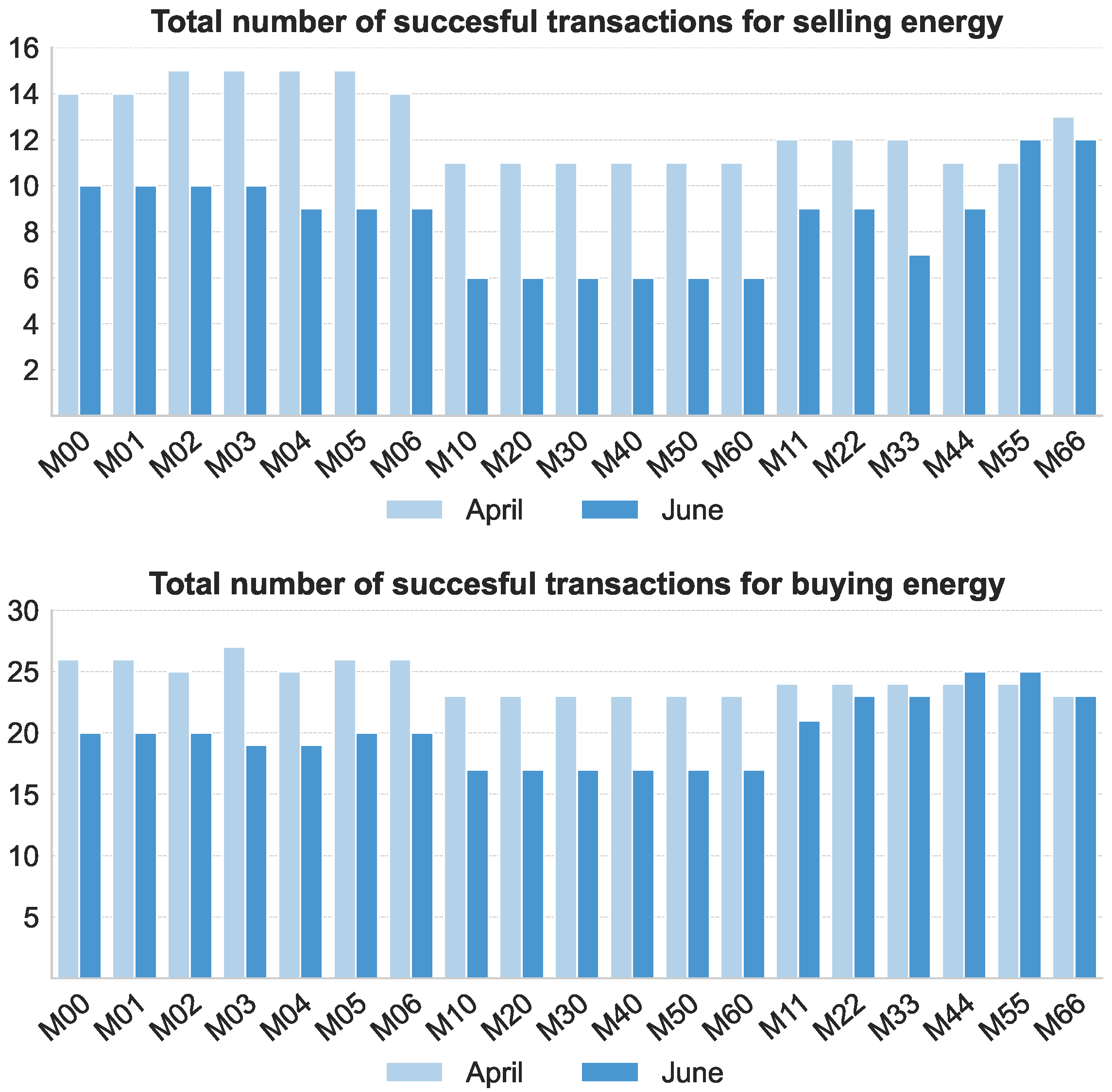

6.3. Availability of Flexible Hours and Success Rates

Flexibility depends on both technical feasibility and economic opportunity.

Figure 6 presents the average number of hours per day in which a technically feasible flexibility action could be scheduled—i.e., hours where a load deviation (positive or negative) can be implemented without violating process or asset constraints.

Buying flexibility is more prevalent than selling, with technical feasibility observed in 2.0–2.7 h/day versus 0.7–2.5 h/day, respectively.

This asymmetry stems from easier ramp-up operations (e.g., activating raw mills or charging batteries) and looser constraints on load increases compared to curtailments.

Battery systems notably expand the set of technically feasible hours for both regulation directions by enabling temporal decoupling. In contrast, PV systems have limited impact on short-term flexibility availability, as they mainly influence baseline cost optimization rather than moment-to-moment scheduling headroom.

However, not all technically feasible actions are economically worthwhile.

Figure 7 shows the number of successful transactions —i.e., actions that are both feasible and profitable after comparing balancing market prices against the cost of deviating from the optimized baseline schedule.

This difference highlights that market signals play a decisive role in monetizing flexibility. Increasing consumption during overgeneration periods (buying) tends to offer more consistent and higher spreads, especially when combined with the operational ease of ramping up equipment or charging batteries.

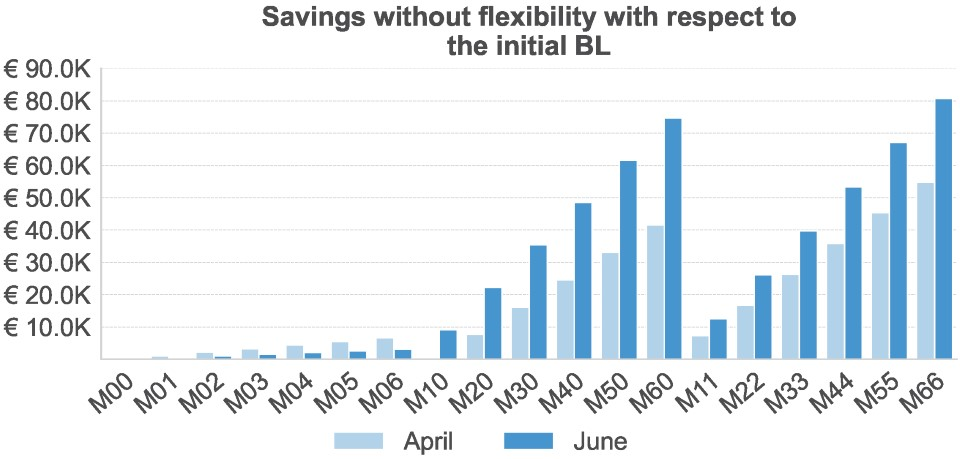

6.4. Savings from Optimized Baseline Scheduling

Flexibility revenues are only part of the economic benefit. Energy assets also enable more efficient baseline scheduling.

Figure 8 compares each scenario’s total electricity cost against the no-asset reference case.

PV systems offer significant cost reductions by directly displacing grid imports during sunny hours.

BESS units allow intra-day arbitrage—charging during low-price periods and discharging during peaks—but offer modest savings on their own.

Combined PV + BESS scenarios yield the greatest cost reductions, although diminishing returns appear at higher capacities.

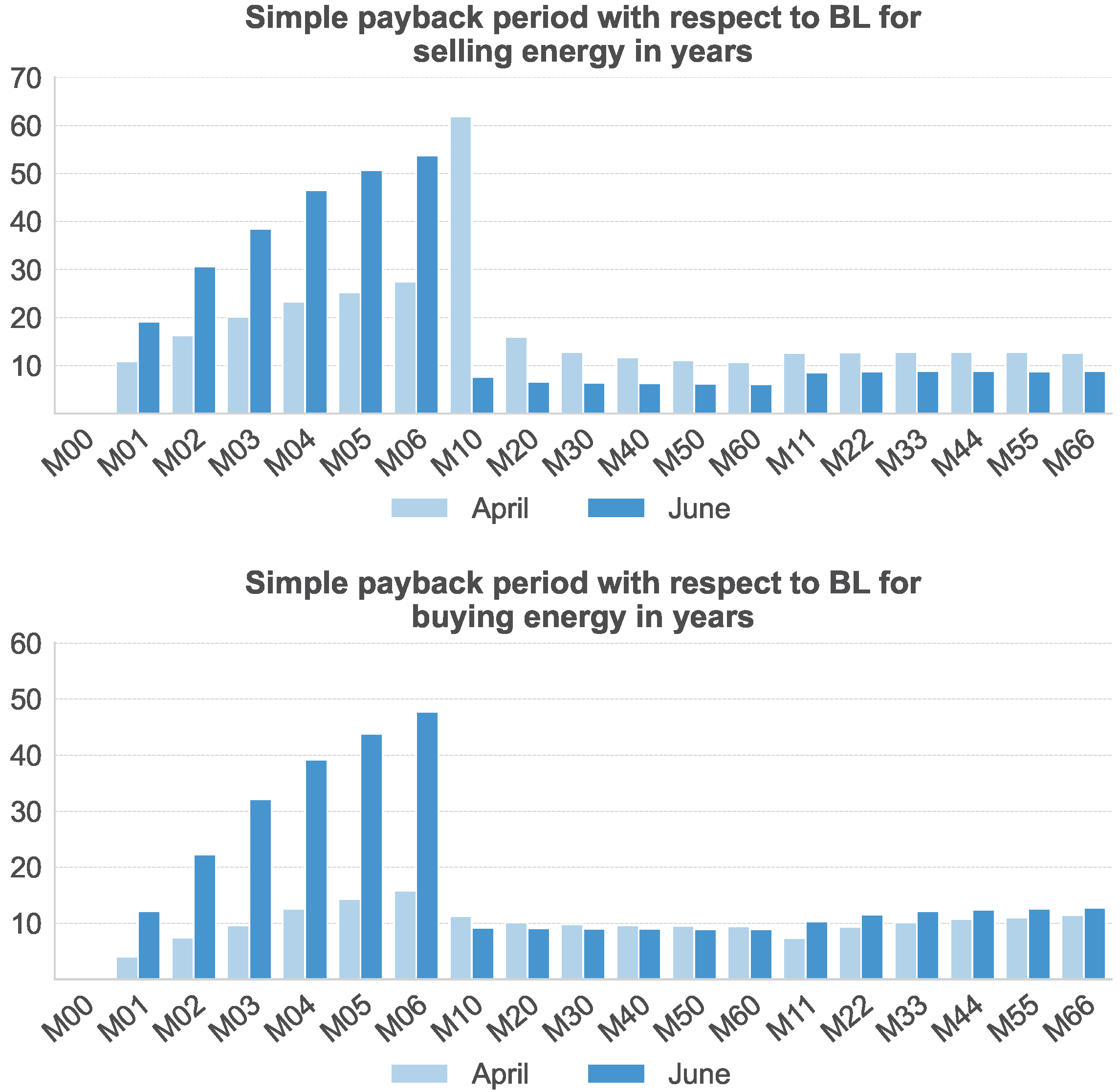

6.5. Investment Payback Period

Figure 9 estimates payback periods using CAPEX assumptions from Lazard [

32]:

PV: 934,500 €/

BESS: 530,885 €/

Annual savings are computed as 12 times the monthly total (baseline savings + flexibility revenues). This yields:

PV-only systems: 7–12 year paybacks, depending on market conditions and asset size.

PV + BESS combinations: 5–7 years in optimal configurations, especially during high-spread periods (e.g., April).

6.6. Economic Relevance in a High-Renewable Context

While Day-Ahead optimization (Stage 1) currently yields the majority of cost savings, relying solely on this strategy exposes the plant to long-term revenue erosion due to the structural evolution of the electricity market. Empirical data from the Spanish market (MIBEL) demonstrates a growing “cannibalization effect”, where high solar penetration significantly depresses spot prices during peak generation hours. Notably, a 1% increase in solar penetration has been shown to reduce solar capture rates by

€/

[

33].

As renewable capacities expand toward 2030 targets, day-ahead arbitrage spreads are projected to shrink, potentially rendering simple shifting strategies financially unviable in this market [

34]. In contrast, balancing markets (Stage 2) are expected to retain high volatility due to the intrinsic intermittency of the generation mix [

35]. Consequently, developing the capability to participate in mFRR acts as a strategic hedge, diversifying revenue streams and ensuring financial robustness in a decarbonized, high-volatility grid environment. Flexibility revenues thus constitute a future-proof complementary income stream, expected to increase as balancing requirements grow.

6.7. Scalability and Generalizability

Addressing the scalability of the proposed framework is essential, as MILP formulations are theoretically NP-hard and computational complexity typically scales non-linearly with the number of binary variables. However, recent literature indicates that deterministic formulations remain highly tractable for operational timeframes. For instance, Caprara et al. [

36] demonstrated that for flexibility aggregators, scaling from 6 to 200 industrial units increased solution times from

s to only

s, confirming that the proposed model can accommodate multiple milling lines without violating operational decision windows.

Beyond computational performance, the framework exhibits high functional generalizability across different industrial sectors and market structures. In a recent comparative analysis [

37], this core MILP formulation was successfully adapted to model an Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) steel plant participating in the continuous intraday market. That study confirmed that the mathematical structure can accommodate distinct process dynamics (batch operations vs. continuous milling) and alternative regulatory regimes with minimal adaptation, validating the model’s applicability to broader energy-intensive industries.

This efficiency validates the design choice of a deterministic framework as the core benchmarking tool. While Robust Optimization or Stochastic Programming offer theoretical advantages for handling uncertainty, they drastically increase model dimensionality. Moretti et al. [

38] note that robust counterparts grow rapidly with the number of uncertain parameters, leading to convergence failures in complex industrial setups unless advanced decomposition techniques (e.g., Benders decomposition) are employed [

39]. Therefore, this study prioritizes a fast, scalable deterministic model to validate the economic concept, establishing a solid foundation upon which future stochastic layers can be applied using aggregation techniques [

40].

6.8. Synthesis of Findings and Limitations

To synthesize the techno-economic analysis, the key operational insights and constraints identified in the case study are summarized below. These findings validate the proposed framework while highlighting specific boundary conditions for implementation.

Baseline cost savings. The Stage 1 model consistently achieved reduction in electricity costs by scheduling mill operation during low-price hours, maximizing PV self-consumption, and exploiting silo storage for demand buffering.

Viable market-based flexibility. Stage 2 identified profitable flexibility opportunities in 18–30% of simulated hours. Monthly revenues ranged from €500 to €800, depending on market conditions and asset configuration.

Added value of battery storage. BESS improved flexibility outcomes by enabling larger deviations, increasing the number of accepted bids, and lowering the marginal cost of schedule adjustments.

Favorable investment metrics. A combined configuration of 1 MWp PV and 1 MWh BESS achieved a simple payback of 6–8 years under April 2023 price conditions, validating the economic viability of the proposed strategy.

Synergistic asset contributions. PV systems reliably reduced baseline costs, while BESS provided temporal flexibility. Together, they yielded superior outcomes compared to either asset alone.

Asymmetric flexibility. Technically feasible buying actions (e.g., load increases) were more frequent than selling, and also more likely to be economically successful. This reflects both market asymmetries and the operational ease of up-ramping in process systems.

Primary value from scheduling. The bulk of the economic gains originated from improved baseline scheduling. Flexibility revenues provided an important but secondary source of value.

While the framework demonstrates strong performance, several simplifying assumptions must be noted:

Deterministic inputs. All simulations assumed perfect foresight for electricity prices, solar generation, and process demand. Forecast uncertainty was not modeled.

No asset degradation. The economic evaluation did not account for equipment degradation—particularly battery cycling costs or wear-and-tear on raw mills.

Price-taker assumption. The plant was assumed to operate without influencing market prices, which may not hold in low-liquidity periods or smaller balancing markets.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This study presented a computationally efficient methodology to unlock short-term flexibility in industrial electricity consumption, bridging the gap between production planning and balancing market participation. By applying a two-stage MILP framework to a Spanish cement plant, the results demonstrate that energy-intensive industries can evolve from passive consumers to active grid assets. The integration of photovoltaic systems and battery energy storage was shown to not only reduce baseline electricity costs but also enable profitable participation in the mFRR market, with investment payback periods as low as six years in favorable scenarios.

The analysis confirms that while baseline scheduling drives the majority of economic savings, flexibility services provide a critical high-value revenue stream that hedges against market volatility. Furthermore, the ability to provide symmetric reserve capacity generates significant systemic value, contributing to grid stability and decarbonization by displacing fossil-fuel-based regulation.

Future research will focus on overcoming the limitations of the current deterministic approach. Priority will be placed on integrating Robust Optimization techniques to address forecast uncertainty, as explored in a recent work [

41] which demonstrated that risk-aware scheduling can significantly reduce expected costs while maintaining stability. Additionally, the framework will be evolved into a hierarchical closed-loop MPC system. By leveraging BESS dynamics to compensate for the mill’s slower response, such an approach will address real-time intra-hour disturbances and unlock participation in faster automated markets.

In conclusion, by combining intelligent scheduling with on-site energy assets, cement manufacturers can secure a dual advantage: enhancing their own economic competitiveness while supporting the transition to a reliable, renewable-dominated power system.

Author Contributions

S.R.-I.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Validation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. E.B.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—Review and Editing. A.M.-C.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization. S.S.-R.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. F.A.F.-E.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The work was supported by the CARTIF Technology Centre (Smart Grid Area).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Fortia Energía. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of Fortia Energía.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Fortia Energía for providing the related information on the Industrial Case Study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5 to enhance readability and improve language clarity. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Nomenclature

| Variables | |

| Power purchased from the grid at time t [. |

| Power exported to the grid at time t [. |

| Power generated by the PV system at time t [. |

| , | Battery charge/discharge power at time t [. |

| Binary on/off status of mill k at time t. |

| Inventory in silo of mill k at time t [. |

| Battery state of charge at time t [. |

| Total electricity procurement cost over the planning horizon [€]. |

| Electricity cost of the baseline schedule [€]. |

| Electricity cost of the flexibility-adjusted schedule [€]. |

| Incremental cost from deviating the baseline schedule [€]. |

| Enforced power deviation in the balancing market [. |

| Total process demand for raw meal at time t [. |

| Portion of withdrawn from silo k [. |

| Constants/Parameters | |

| Day-ahead electricity price at time t [. |

| , | Upward/downward mFRR price at time [. |

| Required spread for flexibility profitability at time [. |

| Rated power consumption of mill k [. |

| Material throughput of mill k [. |

| , | Minimum and maximum inventory in silo k [. |

| Battery energy capacity [. |

| , | Maximum battery charge/discharge power [. |

| Maximum allowed grid import power [. |

| Battery depth of discharge [dimensionless]. |

| Initial battery state of charge [. |

| , | Minimum on/off durations for mill k [. |

| Total baseline grid energy imported [. |

| , | Lower and upper bounds for total energy deviation [dimensionless]. |

| Sets and Indices | |

| t | Time period index. |

| Activation time for flexibility. |

| Set of time periods in the planning horizon. |

| Set of raw milling units. |

| Set of candidate activation hours. |

References

- IEA. Cement Technology Roadmap Plots Path to Cutting CO2 Emissions 24% by 2050. 2018. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/technology-roadmap-low-carbon-transition-in-the-cement-industry (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- RTÉ. Concrete: The World’s Third Largest CO2 Emitter. 2021. Available online: https://www.rte.ie/news/world/2021/1031/1256726-concrete-co2-emitter/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Rodgers, L. Climate Change: The Massive CO2 Emitter You May Not Know About. 2018. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-46455844 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Niranjan, A. Fixing Concrete’s Carbon Footprint. 2022. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/concrete-cement-climate-carbon-footprint/a-60588204 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Ramin, D.; Spinelli, S.; Brusaferri, A. Demand-side management via optimal production scheduling in power-intensive industries: The case of metal casting process. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.; Borggrefe, F. The potential of demand-side management in energy-intensive industries for electricity markets in Germany. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orths, A.; Anderson, C.L.; Brown, T.; Mulhern, J.; Pudjianto, D.; Ernst, B.; O‘Malley, M.; McCalley, J.; Strbac, G. Flexibility from Energy Systems Integration: Supporting Synergies Among Sectors. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2019, 17, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossie, A.T.; Khatiwada, D.; Palm, B.; Bekele, G. Energy demand flexibility potential in cement industries: How does it contribute to energy supply security and environmental sustainability? Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollert, K.E. Demand response aggregators as institutional entrepreneurs in the European electricity market. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 353, 131501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierri, E.; Schulze, C.; Herrmann, C.; Thiede, S. Integrated methodology to assess the energy flexibility potential in the process industry. Procedia CIRP 2020, 90, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, A.; Koolen, D.; Crijns-Graus, W.; van den Broek, M.; Worrell, E. The Demand Response Potential in a Decarbonising Iron and Steel Industry: A Review of Flexible Steelmaking. SSRN 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4472250 (accessed on 25 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, B.; Xu, F.Y.; Lai, L.L.; Yang, C.; Lu, S.; Li, D. A model of Demand Response scheduling for cement plant. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), San Diego, CA, USA, 5–8 October 2014; pp. 3042–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiguzel, E. Global Cement Industry Outlook: Trends and Forecasts. 2024. Available online: https://worldcementassociation.org/blog/news/global-cement-industry-outlook-trends-and-forecasts (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Zahari, N.E.M.; Mokhlis, H.; Mubarak, H.; Mansor, N.N.; Sulaima, M.F.; Ramasamy, A.K.; Zulkapli, M.F.; Ja’Apar, M.A.; Jaafar, M.; Marsadek, M.B. Integrating Solar PV, Battery Storage, and Demand Response for Industrial Peak Shaving: A Systematic Review on Strategy, Challenges and Case Study in Malaysian Food Manufacturing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 106832–106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yu, F.; Huang, P.; Liu, G.; Zhang, M.; Sun, R. Game-theoretic evolution in renewable energy systems: Advancing sustainable energy management and decision optimization in decentralized power markets. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 217, 115776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, D. Opportunities for Energy Efficiency and Demand Response in the California Cement Industry; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7856f8vn (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Lee, E.; Baek, K.; Kim, J. Evaluation of Demand Response Potential Flexibility in the Industry Based on a Data-Driven Approach. Energies 2020, 13, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, M. Flexible Electricity Use in the Cement Industry: Laying the Foundation for a Not so Concrete Future. Master’s Thesis, Utrech University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. Available online: https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/39926 (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Parejo Guzmán, M.; Navarrete Rubia, B.; Mora Peris, P.; Alfalla-Luque, R. Methodological development for the optimisation of electricity cost in cement factories: The use of artificial intelligence in process variables. Electr. Eng. 2022, 104, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Thomson, C.J.; Wang, S.; Rahbari, A.; McArthur, L.; Liu, A.; Pye, J. Decarbonising heavy industry operations with low-cost onsite photovoltaics and battery storage. Sol. Energy 2025, 281, 114104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Parisio, A. Distributed control of flexible assets in distribution networks considering personal usage plans. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 42, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, S.; Fernández, D.; Pozo, C.; Folgado, R.; Jiménez, L.; Boer, D. Scheduling optimization and risk analysis for energy-intensive industries under uncertain electricity market to facilitate financial planning. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 174, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Qiu, Z. Review of Power Market Optimization Strategies Based on Industrial Load Flexibility. Energies 2025, 18, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, A. The State of the Art in Model Predictive Control Application for Demand Response. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2022, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, B.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Lv, C.; Xu, X.; Liu, J. A Review of Industrial Load Flexibility Enhancement for Demand-Response Interaction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Eléctrica de España. Operating Procedure 7.3: Tertiary Regulation; Red Eléctrica de España (REE): Alcobendas, Madrid, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Y.; Mazumdar, B.; Ghosh, P. Thermal energy consumption and its conservation for a cement production unit. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 26, 200111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Eléctrica de España. Operation of the Electricity System. 2023. Available online: https://www.ree.es/en/operation (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Sebastián, C.; González-Guillén, C.E.; Juan, J. An adaptive standardisation model for Day-Ahead electricity price forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.02610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, S.; Miltenberger, M.; Pedroso, J.P.; Rehfeldt, D.; Schwarz, R.; Serrano, F. PySCIPOpt: Mathematical Programming in Python with the SCIP Optimization Suite. In Mathematical Software—ICMS 2016, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, Berlin, Germany, 11–14 July 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestuzheva, K.; Besançon, M.; Chen, W.K.; Chmiela, A.; Donkiewicz, T.; van Doornmalen, J.; Eifler, L.; Gaul, O.; Gamrath, G.; Gleixner, A.; et al. The SCIP Optimization Suite 8.0; ZIB-Report 21-41; Zuse Institute Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0297-zib-85309 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Lazard. 2023 Levelized Cost of Energy. 2023. Available online: https://www.lazard.com/research-insights/2023-levelized-cost-of-energyplus/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Peña, J.I.; Rodríguez, R.; Mayoral, S. Cannibalization, depredation, and market remuneration of power plants. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovas, P.; Gudzius, S.; Jonaitis, A.; Konstantinaviciute, I.; Bobinaite, V.; Gudziute, S.; Giedraitis, G. Price Cannibalization Effect on Long-Term Electricity Prices and Profitability of Renewables in the Baltic States. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, D.P.; Marques, A.C.; Damette, O. The role of electricity flows and renewable electricity production in the behaviour of electricity prices in Spain. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, A.; Barja-Martinez, S.; Aragüés-Peñalba, M.; Bullich-Massagué, E. Flexibility Service for Balance Responsible Parties’ Industrial Customers: A Day-Ahead Cost Optimization Approach Using Price Forecasting. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 81188–81203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Innocenti, S.; Baeyens, E.; Martín-Crespo, A.; Saludes-Rodil, S.; Frechoso, F. A Comparative Analysis of Electricity Consumption Flexibility in Different Industrial Plant Configurations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2411.09279. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, L.; Martelli, E.; Manzolini, G. An efficient robust optimization model for the unit commitment and dispatch of multi-energy systems and microgrids. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 113859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Su, L. Robust optimization for a steel production planning problem with uncertain demand and product substitution. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 165, 106569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Cesena, E.A.; Mancarella, P. Energy Systems Integration in Smart Districts: Robust Optimisation of Multi-Energy Flows in Integrated Electricity, Heat and Gas Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Innocenti, S.; Baeyens, E.; Frechoso, F.; Martín-Crespo, A.; Saludes-Rodil, S. A robust optimization framework for flexible industrial energy scheduling: Application to a cement plant with market participation. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 4570–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic of Portland cement production. The highlighted raw meal preparation stage is decoupled from kiln operation and offers flexibility potential.

Figure 1.

Schematic of Portland cement production. The highlighted raw meal preparation stage is decoupled from kiln operation and offers flexibility potential.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the modeled production subsystem, including raw mills, silos, PV generation, BESS, and grid connection. The model supports scalability to multi-unit scenarios.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the modeled production subsystem, including raw mills, silos, PV generation, BESS, and grid connection. The model supports scalability to multi-unit scenarios.

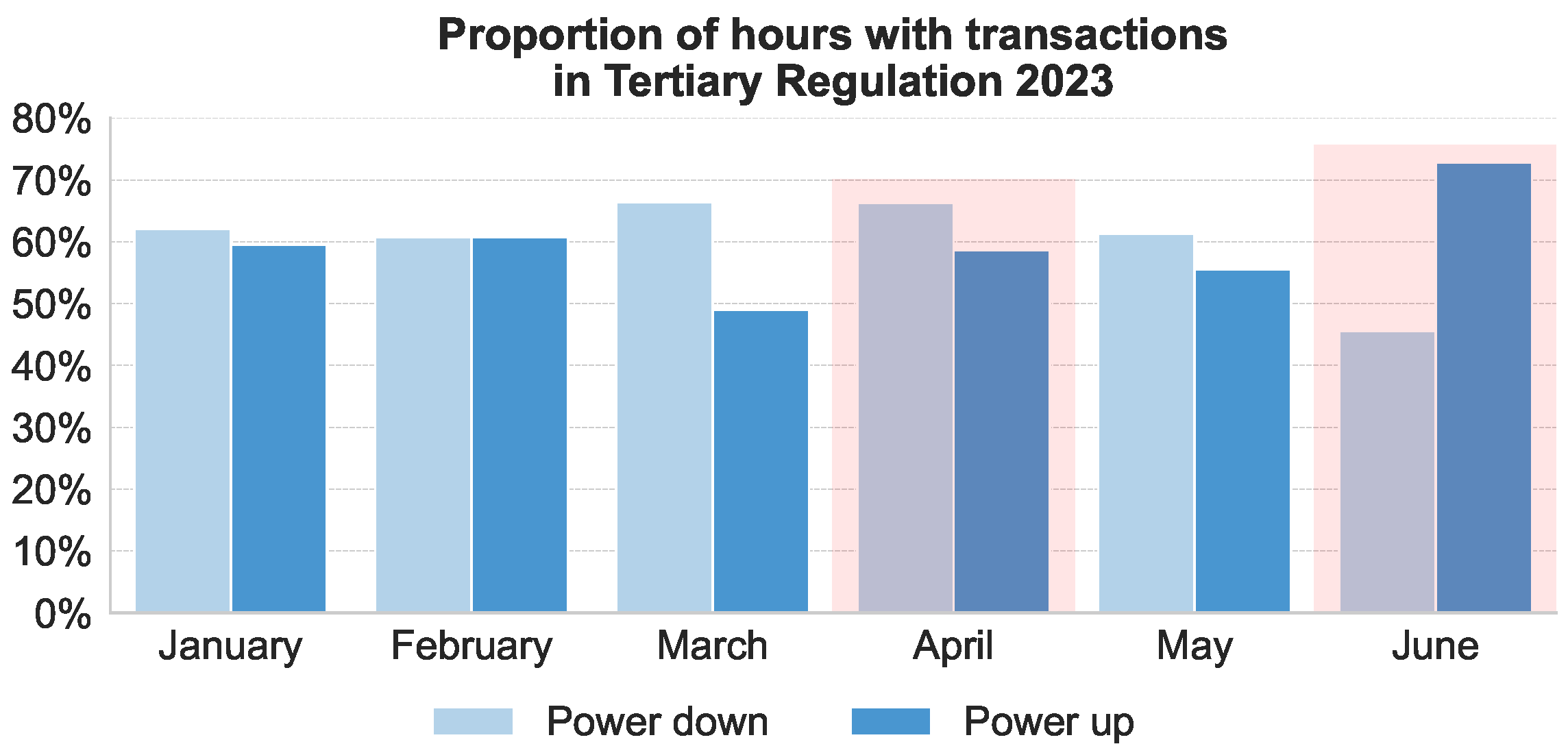

Figure 3.

Top: Share of hours with activation in the tertiary regulation (mFRR) market in 2023, disaggregated by direction (upward = load reduction, downward = load increase). Bottom: Corresponding average price spreads (€/MWh) between day-ahead and balancing markets, reflecting the financial incentive for flexible participation. April shows high activation and high spread levels; June shows reduced opportunities dominated by downward regulation.

Figure 3.

Top: Share of hours with activation in the tertiary regulation (mFRR) market in 2023, disaggregated by direction (upward = load reduction, downward = load increase). Bottom: Corresponding average price spreads (€/MWh) between day-ahead and balancing markets, reflecting the financial incentive for flexible participation. April shows high activation and high spread levels; June shows reduced opportunities dominated by downward regulation.

Figure 4.

Top: Selling electricity via load reduction (3 April 2023). Bottom: Buying electricity via load increase (5 June 2023). Black: baseline schedule. Red: flexibility-adjusted schedule.

Figure 4.

Top: Selling electricity via load reduction (3 April 2023). Bottom: Buying electricity via load increase (5 June 2023). Black: baseline schedule. Red: flexibility-adjusted schedule.

Figure 5.

Monthly profits from flexibility provision in the tertiary regulation market. Top: Selling (upward). Bottom: Buying (downward). Batteries significantly enhance revenues across scenarios.

Figure 5.

Monthly profits from flexibility provision in the tertiary regulation market. Top: Selling (upward). Bottom: Buying (downward). Batteries significantly enhance revenues across scenarios.

Figure 6.

Average daily hours with technically feasible flexibility actions. Battery storage increases flexibility windows across scenarios.

Figure 6.

Average daily hours with technically feasible flexibility actions. Battery storage increases flexibility windows across scenarios.

Figure 7.

Monthly accepted (i.e., technically and economically viable) flexibility transactions. More buying actions are accepted due to favorable market spreads and fewer operational constraints.

Figure 7.

Monthly accepted (i.e., technically and economically viable) flexibility transactions. More buying actions are accepted due to favorable market spreads and fewer operational constraints.

Figure 8.

Electricity cost savings from improved baseline scheduling, relative to the reference case (M00). PV dominates cost avoidance; BESS provides complementary returns.

Figure 8.

Electricity cost savings from improved baseline scheduling, relative to the reference case (M00). PV dominates cost avoidance; BESS provides complementary returns.

Figure 9.

Estimated investment payback periods. Best outcomes occur in PV + BESS configurations under favorable market conditions.

Figure 9.

Estimated investment payback periods. Best outcomes occur in PV + BESS configurations under favorable market conditions.

Table 1.

Key notation used in the Stage 1 optimization model.

Table 1.

Key notation used in the Stage 1 optimization model.

| Symbol | Description | Unit/Type |

|---|

| Time periods in planning horizon | index set |

| Raw milling units | index set |

| On/off status of mill k | binary |

| Inventory in silo k | [t] |

| Grid import/export power | [MW] |

| BESS charging/discharging power | [MW] |

| BESS state of charge | [MWh] |

| Day-ahead electricity price | [€/MWh] |

| PV generation | [MW] |

| , | Power and throughput of mill k | [MW], [t/h] |

| Silo inventory limits | [t] |

| Battery capacity | [MWh] |

| BESS power limits | [MW] |

| Min. uptime/downtime | [h] |

| Max grid import capacity | [MW] |

| , | Total and per-silo process demand | [t/h] |

| Total electricity cost | [€] |

Table 2.

Notation specific to the flexibility evaluation model (Stage 2).

Table 2.

Notation specific to the flexibility evaluation model (Stage 2).

| Symbol | Description | Unit/Type |

|---|

| Activation hour for flexibility provision | [h] (index) |

| Enforced power deviation at time | [MW] |

| Baseline grid import at time | [MW] |

| Baseline inventory for mill k at time | [t] |

| Cost of the baseline schedule (Stage 1) | [€] |

| Cost of the flexibility-adjusted schedule | [€] |

| Flexibility cost: | [€] |

| Upward regulation price (load reduction) | [€/MWh] |

| Downward regulation price (load increase) | [€/MWh] |

| Minimum break-even price spread | [€/MWh] |

| Total energy purchased under baseline | [MWh] |

| Energy deviation tolerances | [0–1] |

Table 3.

Technology configurations simulated in the case study. Scenario code MXY indicates PV capacity X (MWp) and BESS capacity Y (MWh).

Table 3.

Technology configurations simulated in the case study. Scenario code MXY indicates PV capacity X (MWp) and BESS capacity Y (MWh).

| Scenario Code(s) | PV Capacity (MWp) | BESS Capacity (MWh) | Configuration Type | Purpose |

|---|

| M00 | 0 | 0 | No PV, no BESS | Reference case |

| M10–M60 | 1–6 | 0 | PV only | RES scale-up analysis |

| M01–M06 | 0 | 1–6 | BESS only | Storage-only evaluation |

| M11, M22, …, M66 | 1–6 | 1–6 (diagonal only) | PV + BESS | Balanced combined strategies |

Table 4.

Profitability analysis for selling energy in the tertiary regulation market on 3 April 2023. The row highlighted in gray indicates the selected transaction (highest profit).

Table 4.

Profitability analysis for selling energy in the tertiary regulation market on 3 April 2023. The row highlighted in gray indicates the selected transaction (highest profit).

| Hour () | Day-Ahead Price | mFRR Price | Spread | Power Sold | Revenue | Flex Cost | Profit |

|---|

| [] | [] | [] | [] | [MW] | [€] | [€] | [€] |

|---|

| 1 | 68.97 | 84.35 | 15.38 | | 92.25 | 45.00 | 47.25 |

| 7 | 70.48 | 92.80 | 22.32 | | 133.90 | 35.90 | 98.00 |

| 11 | 55.89 | – | – | | – | 123.50 | – |

|

19 | 64.10 | 97.28 | 33.18 | | 199.01 | 74.20 | 124.87 |

Table 5.

Profitability analysis for purchasing energy in the tertiary regulation market on 5 June 2023. The row highlighted in gray indicates the selected transaction (highest net benefit).

Table 5.

Profitability analysis for purchasing energy in the tertiary regulation market on 5 June 2023. The row highlighted in gray indicates the selected transaction (highest net benefit).

| Hour () | Day-Ahead Price | mFRR Price | Spread | Power Bought | Savings | Flex Cost | Net Benefit |

|---|

| [] | [] | [] | [] | [MW] | [€] | [€] | [€] |

|---|

| 4 | 114.99 | – | – | 6 | – | 23.50 | – |

| 8 | 117.89 | 61.99 | 55.90 | 6 | 354.02 | 59.50 | 294.52 |

|

20 | 115.77 | 45.56 | 70.21 | 6 | 421.24 | 28.10 | 393.14 |

| 23 | 117.63 | 60.77 | 56.86 | 6 | 341.16 | 39.30 | 301.86 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).