Quantifying Swirl Number Effects on Recirculation Zones and Vortex Dynamics in a Dual-Swirl Combustor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Formulation

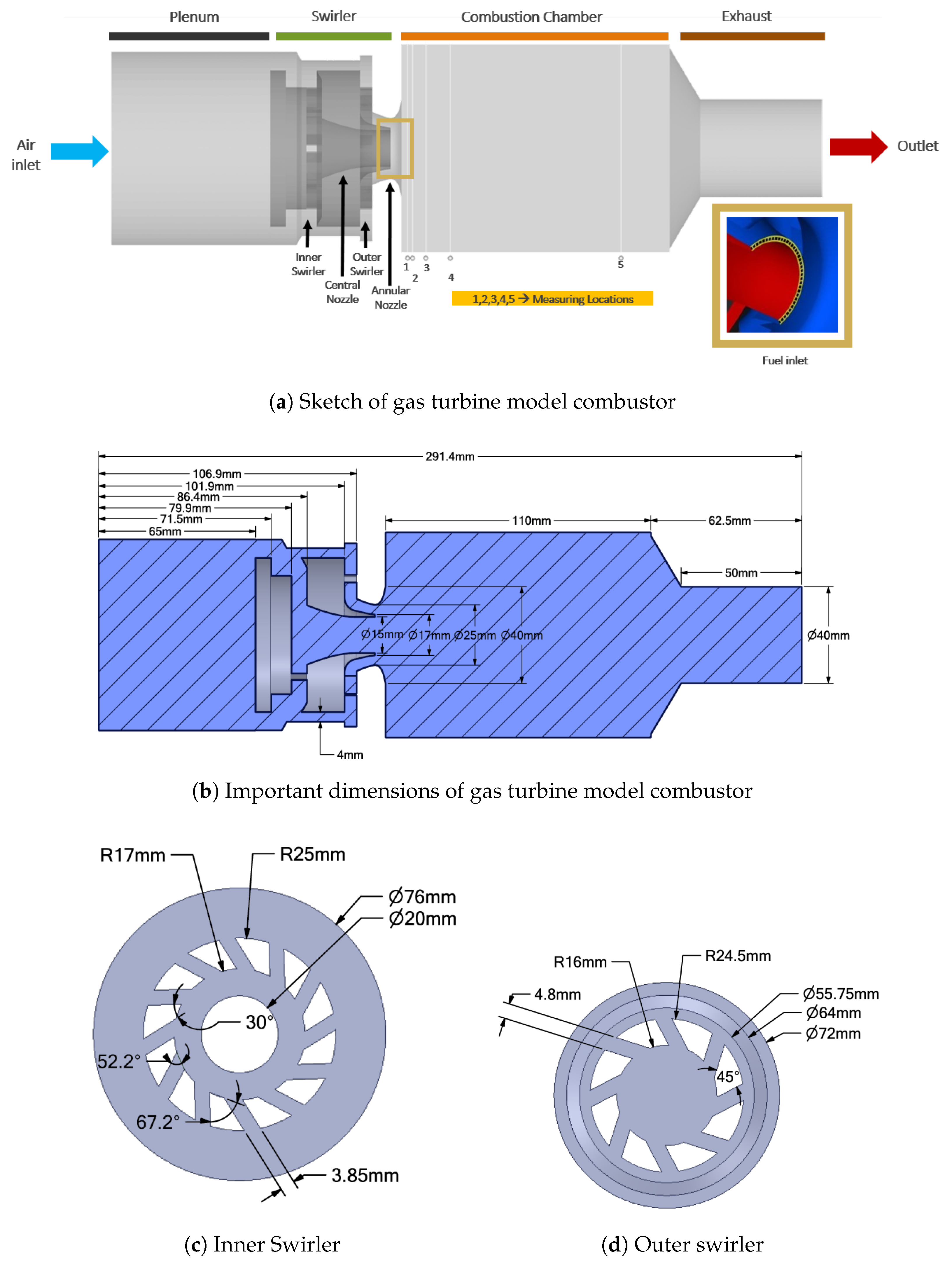

2.1. Computational Setup

2.2. Numerical Setup

2.2.1. Shear Stress Transport

2.2.2. Detached Eddy Simulation Model (DES)

2.2.3. Scale Adaptive Simulation Model (SAS)

2.2.4. Large Eddy Simulation

2.3. Mesh Generation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Part 1: Numerical Investigation of Turbulence Models

3.1.1. General Flow Structure

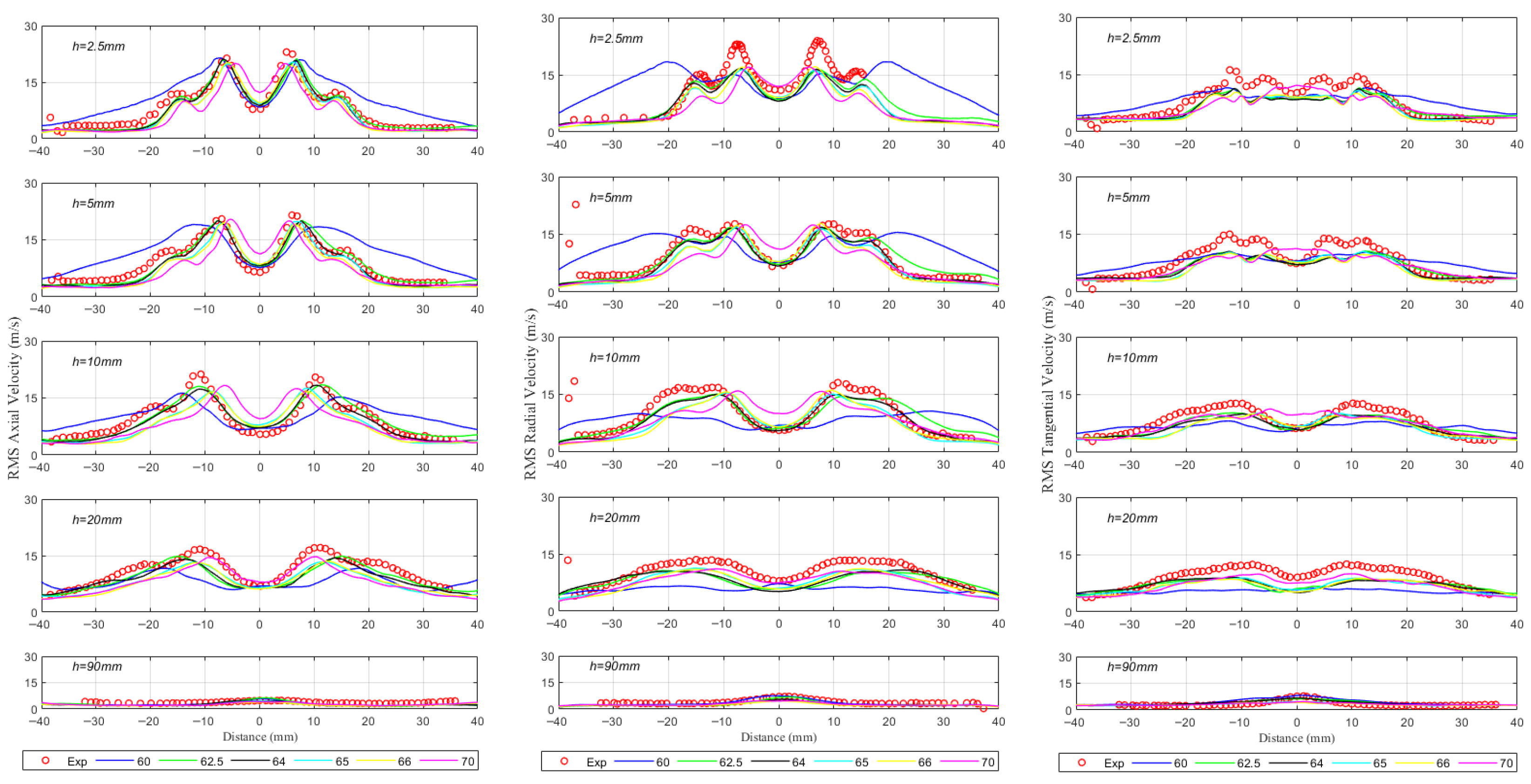

3.1.2. Time-Averaged and RMS Measurements

3.2. Part 2: Effect of Swirl Number on Flow Dynamics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Syred, N.; Beér, J. Combustion in swirling flows: A review. Combust. Flame 1974, 23, 143–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Lilley, D.G.; Syred, N. Swirl flows. In Tunbridge Wells; Abacus Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chterev, I.; Emerson, B.; Lieuwen, T. Velocity and stretch characteristics at the leading edge of an aerodynamically stabilized flame. Combust. Flame 2018, 193, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.; Beér, J. Flow in the wake of bluff-body flame stabilizers. Symp. (Int.) Combust. 1971, 13, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovich, S. The structure of vortex breakdown. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1978, 10, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudier, M. Vortex breakdown: Observations and explanations. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 1988, 25, 189–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucca-Negro, O.; O’Doherty, T. Vortex breakdown: A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2001, 27, 431–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syred, N. A review of oscillation mechanisms and the role of the precessing vortex core (PVC) in swirl combustion systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2006, 32, 93–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdabadi, P.; Griffiths, A.; Syred, N. Characterization of the PVC phenomena in the exhaust of a cyclone dust separator. Exp. Fluids 1994, 17, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacleto, P.; Fernandes, E.; Heitor, M.; Shtork, S. Swirl flow structure and flame characteristics in a model lean premixed combustor. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2003, 175, 1369–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Boxx, I.; Meier, W.; Slabaugh, C.D. Coupled interactions of a helical precessing vortex core and the central recirculation bubble in a swirl flame at elevated power density. Combust. Flame 2019, 202, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberleithner, K.; Terhaar, S.; Rukes, L.; Oliver Paschereit, C. Why nonuniform density suppresses the precessing vortex core. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2013, 135, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Lartigue, G.; Poinsot, T.; Meier, U.; Bérat, C. Studies of mean and unsteady flow in a swirled combustor using experiments, acoustic analysis, and large eddy simulations. Combust. Flame 2005, 141, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, J.; McLaughlin, D. Experiments on the instabilities of a swirling jet. Phys. Fluids 1994, 6, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, I.K.; Honnery, D.; Soria, J. Axial plus tangential entry swirling jet. Exp. Fluids 2010, 48, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudier, M.; Keller, J. Recirculation in swirling flow-a manifestation of vortex breakdown. AIAA J. 1985, 23, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altgeld, H.; Jones, W.; Wilhelmi, J. Velocity measurements in a confined swirl driven recirculating flow. Exp. Fluids 1983, 1, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, R.; Naughton, J. Experimental study of incompressible jets with different initial swirl distributions: Mean results. AIAA J. 2005, 43, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, D.G.; Smith, P.J.; Smoot, L. Modeling of swirl in turbulent flow systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 1986, 12, 163–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Kleiser, L. Large-eddy simulation of vortex breakdown in compressible swirling jet flow. Comput. Fluids 2008, 37, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberleithner, K.; Sieber, M.; Nayeri, C.N.; Paschereit, C.O.; Petz, C.; Hege, H.C.; Noack, B.R.; Wygnanski, I. Three-dimensional coherent structures in a swirling jet undergoing vortex breakdown: Stability analysis and empirical mode construction. J. Fluid Mech. 2011, 679, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanoverberghe, K.P.; Van Den Bulck, E.V.; Tummers, M.J. Confined annular swirling jet combustion. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2003, 175, 545–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanierschot, M. Fluid Mechanics and Control of Annular Jets With and Without Swirl. Ph.D. Thesis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yellugari, K.; Villalva Gomez, R.; Gutmark, E. Effects of Swirl Number and Central Rod on Flow in a Lean Premixed Swirl Combustor. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2025, 197, 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Maxworthy, T. An experimental investigation of swirling jets. J. Fluid Mech. 2005, 525, 115–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Li, J.; Jin, W.; Yuan, L.; Yao, Q. Numerical investigation on the influence of swirl number to high-temperature zone evolution and outlet temperature distribution in multi-stage combustor. Fuel 2025, 381, 133264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widenhorn, A.; Noll, B.; Aigner, M. Numerical characterization of a gas turbine model combustor. In High Performance Computing in Science and Engineering’09; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Weigand, P.; Meier, W.; Duan, X.R.; Stricker, W.; Aigner, M. Investigations of swirl flames in a gas turbine model combustor: I. Flow field, structures, temperature, and species distributions. Combust. Flame 2006, 144, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, D.C. Turbulence Modeling for CFD; DCW industries: La Canada, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Strelets, M. Detached eddy simulation of massively separated flows. In Proceedings of the 39th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 8–11 January 2001; p. 879. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, B.; Schütz, H.; Aigner, M. Numerical simulation of high-frequency flow instabilities near an airblast atomizer. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, New Orleans, LA, USA, 4–7 June 2001; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 78514, p. V002T02A008. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.; Egorov, Y. A scale adaptive simulation model using two-equation models. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 10–13 January 2005; p. 1095. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoud, F.; Ducros, F. Subgrid-scale stress modelling based on the square of the velocity gradient tensor. Flow Turbul. Combust. 1999, 62, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palulli, R.; Dybe, S.; Zhang, K.; Güthe, F.; Alemela, P.R.; Paschereit, C.O.; Duwig, C. Characterisation of non-premixed, swirl-stabilised, wet hydrogen/air flame using large eddy simulation. Fuel 2023, 350, 128710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strempfl, P.; Dounia, O.; Laera, D.; Poinsot, T. Effects of mixing assumptions and models for LES of hydrogen-fueled rotating detonation engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, S.; Mercier, R.; Fiorina, B. Controlling the resolved flame thickness of non-premixed flames in LES with filtered tabulated chemistry. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Shen, Y.; Palulli, R.; Ghobadian, A.; Nouri, J.; Duwig, C. Combustion characteristics of steam-diluted decomposed ammonia in multiple-nozzle direct injection burner. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 16083–16099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehole, H.A.H.; Mehdi, G.; Riaz, R.; Maqsood, A. Investigation of Sustainable Combustion Processes of the Industrial Gas Turbine Injector. Processes 2025, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluent, A. Fluent 14.0 User’s Guide; Ansys Fluent Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent flows. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widenhorn, A.; Noll, B.; Aigner, M. Accurate boundary conditions for the numerical simulation of thermoacoustic phenomena in gas-turbine combustion chambers. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Barcelona, Spain, 8–11 May 2006; Volume 42363, pp. 347–356. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1.256 g/s | Mass flow rate at fuel inlet | |

| 19.74 g/s | Mass flow rate at air inlet |

| Loc. | Method | Axial Velocity (m/s) | Radial Velocity (m/s) | Tangential Velocity (m/s) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Max | Mean Center | RMS Max | RMS Center | Mean Max | Mean Center | RMS Max | RMS Center | Mean Max | Mean Center | RMS Max | RMS Center | ||

| 2.5 mm | Exp | 35.44 | −16.84 | 22.98 | 7.86 | 22.79 | −0.13 | 23.94 | 10.95 | 30.04 | 0.52 | 16.15 | 10.20 |

| LES | 36.07 | −15.97 | 20.66 | 9.42 | 16.80 | −0.13 | 16.42 | 8.89 | 29.98 | 0.20 | 10.87 | 8.81 | |

| SAS | 35.56 | −15.51 | 20.92 | 9.57 | 16.68 | 0.72 | 16.43 | 8.69 | 28.61 | −0.36 | 11.16 | 9.14 | |

| DES | 37.97 | −15.19 | 20.33 | 9.32 | 15.85 | −0.36 | 16.33 | 9.17 | 29.89 | −0.28 | 10.75 | 9.19 | |

| SST | 31.11 | −13.58 | 14.69 | 6.49 | 21.17 | −0.24 | 11.45 | 4.60 | 28.04 | −0.23 | 9.85 | 4.63 | |

| 5 mm | Exp | 38.47 | −16.50 | 21.49 | 6.45 | 24.99 | 1.95 | 22.75 | 6.93 | 23.93 | 0.00 | 15.00 | 7.42 |

| LES | 32.33 | −15.94 | 20.21 | 8.69 | 14.26 | −0.11 | 17.00 | 7.75 | 23.22 | 0.32 | 10.57 | 7.38 | |

| SAS | 32.86 | −15.38 | 21.04 | 8.34 | 14.74 | 0.77 | 16.72 | 7.17 | 22.47 | −0.62 | 10.72 | 7.63 | |

| DES | 33.01 | −15.15 | 19.77 | 8.46 | 13.68 | −0.33 | 16.93 | 7.95 | 24.10 | −0.07 | 10.54 | 7.89 | |

| SST | 28.37 | −14.45 | 14.64 | 6.11 | 18.33 | −0.13 | 12.34 | 3.04 | 20.62 | −0.13 | 8.99 | 3.04 | |

| 10 mm | Exp | 34.40 | −16.04 | 21.25 | 5.47 | 11.46 | 0.90 | 18.46 | 5.68 | 20.77 | 0.52 | 12.76 | 6.24 |

| LES | 26.73 | −13.31 | 17.72 | 7.73 | 8.76 | −0.27 | 15.14 | 6.65 | 16.92 | −0.29 | 9.95 | 6.55 | |

| SAS | 27.08 | −13.84 | 18.23 | 7.11 | 10.51 | −0.11 | 15.14 | 6.28 | 16.34 | −0.43 | 10.22 | 6.27 | |

| DES | 28.03 | −12.88 | 17.56 | 7.91 | 9.23 | 0.35 | 15.41 | 6.68 | 17.92 | 0.30 | 10.15 | 6.76 | |

| SST | 25.70 | −15.41 | 13.49 | 5.42 | 12.16 | −0.07 | 11.27 | 1.70 | 14.58 | −0.07 | 7.07 | 1.72 | |

| 20 mm | Exp | 25.80 | −15.40 | 17.12 | 6.90 | 7.22 | −0.38 | 13.51 | 7.95 | 18.03 | 0.52 | 12.47 | 9.03 |

| LES | 18.29 | −10.06 | 14.40 | 6.10 | 5.97 | −0.53 | 10.78 | 5.07 | 10.65 | −0.45 | 8.97 | 5.46 | |

| SAS | 18.08 | −10.79 | 13.67 | 6.11 | 5.95 | −1.72 | 10.83 | 5.13 | 11.12 | −0.12 | 8.77 | 5.88 | |

| DES | 19.25 | −9.39 | 13.38 | 6.49 | 4.98 | 0.11 | 11.28 | 6.05 | 11.40 | −0.19 | 8.86 | 5.82 | |

| SST | 18.53 | −14.31 | 11.08 | 4.49 | 3.13 | −0.25 | 7.32 | 2.48 | 10.46 | 0.13 | 4.57 | 2.21 | |

| 90 mm | Exp | 11.52 | 11.18 | 4.86 | 4.86 | 0.23 | −0.26 | 7.12 | 7.07 | 10.94 | −2.05 | 7.82 | 7.66 |

| LES | 7.81 | 7.59 | 5.04 | 4.97 | 1.59 | −0.85 | 5.27 | 5.07 | 7.49 | −2.69 | 4.85 | 4.48 | |

| SAS | 7.54 | 7.44 | 5.51 | 5.39 | 1.15 | −0.53 | 5.40 | 5.32 | 6.75 | 0.94 | 5.66 | 5.65 | |

| DES | 6.18 | 6.16 | 4.48 | 4.48 | 1.59 | 0.26 | 4.58 | 4.44 | 6.46 | −0.65 | 4.64 | 4.64 | |

| SST | 3.81 | 3.60 | 2.63 | 1.89 | 1.43 | −0.23 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 5.16 | −0.39 | 2.65 | 0.52 | |

| Swirl Number | Geometric Modification | Vane Angle |

|---|---|---|

| 0.94 | Mod-1 | 60° |

| 0.88 | Mod-2 | 62.5° |

| 0.86 | Mod-3 | 64° |

| 0.787 | Mod-4 | 65° |

| 0.793 | Mod-5 | 66° |

| 0.7 | Mod-6 | 70° |

| Loc. | Angle | Axial Velocity (m/s) | Radial Velocity (m/s) | Tangential Velocity (m/s) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Max | Mean Center | RMS Max | RMS Center | Mean Max | Mean Center | RMS Max | RMS Center | Mean Max | Mean Center | RMS Max | RMS Center | ||

| 2.5 mm | Exp | 35.44 | −16.84 | 22.98 | 7.86 | 22.79 | −0.13 | 23.94 | 10.95 | 30.04 | 0.52 | 16.15 | 10.20 |

| 60° | 19.69 | −13.04 | 21.43 | 8.39 | 24.69 | 0.43 | 18.45 | 8.75 | 21.18 | −1.74 | 11.51 | 9.06 | |

| 62.5° | 32.24 | −15.50 | 21.26 | 8.86 | 18.75 | 0.21 | 16.62 | 8.53 | 28.47 | 0.30 | 11.48 | 8.61 | |

| 64° | 33.49 | −15.74 | 21.14 | 8.88 | 17.24 | −0.50 | 16.69 | 8.10 | 28.81 | −0.24 | 11.37 | 8.41 | |

| 65° | 37.97 | −15.19 | 20.33 | 9.32 | 15.85 | −0.36 | 16.33 | 9.17 | 29.89 | −0.28 | 10.75 | 9.19 | |

| 66° | 37.94 | −15.83 | 20.19 | 9.59 | 16.00 | −0.20 | 17.15 | 9.03 | 30.10 | −0.07 | 10.35 | 9.07 | |

| 70° | 44.04 | −9.46 | 20.00 | 12.23 | 11.24 | 0.03 | 17.06 | 12.00 | 31.06 | −1.06 | 12.13 | 12.12 | |

| 10 mm | Exp | 38.47 | −16.50 | 21.49 | 6.45 | 24.99 | 1.95 | 22.75 | 6.93 | 23.93 | 0.00 | 15.00 | 7.42 |

| 60° | 10.79 | −11.52 | 19.03 | 7.72 | 17.95 | −0.07 | 15.52 | 7.76 | 13.88 | −1.76 | 10.33 | 8.07 | |

| 62.5° | 29.38 | −14.85 | 20.16 | 8.12 | 15.90 | 0.15 | 16.72 | 7.21 | 22.12 | 0.01 | 10.65 | 7.05 | |

| 64° | 30.53 | −15.10 | 20.00 | 8.23 | 14.39 | −0.39 | 16.88 | 6.79 | 22.20 | −0.02 | 10.56 | 7.19 | |

| 65° | 33.01 | −15.15 | 19.77 | 8.46 | 13.68 | −0.33 | 16.93 | 7.95 | 24.10 | −0.07 | 10.54 | 7.89 | |

| 66° | 33.23 | −15.62 | 19.66 | 8.59 | 12.28 | −0.01 | 17.82 | 7.91 | 23.46 | −0.64 | 10.10 | 7.68 | |

| 70° | 39.38 | −10.51 | 20.38 | 11.27 | 8.92 | −0.18 | 17.52 | 11.20 | 24.73 | −0.20 | 11.28 | 11.28 | |

| 15 mm | Exp | 34.40 | −16.04 | 21.25 | 5.47 | 11.46 | 0.90 | 18.46 | 5.68 | 20.77 | 0.52 | 12.76 | 6.24 |

| 60° | 6.18 | −8.63 | 16.28 | 7.06 | 7.73 | −0.45 | 10.66 | 6.98 | 8.55 | −1.42 | 8.17 | 6.20 | |

| 62.5° | 23.83 | −12.44 | 18.49 | 7.42 | 10.08 | 0.42 | 15.10 | 6.16 | 15.42 | −0.96 | 10.27 | 5.91 | |

| 64° | 24.47 | −12.72 | 18.33 | 7.13 | 9.91 | −0.03 | 15.02 | 5.61 | 15.34 | 0.15 | 10.01 | 5.96 | |

| 65° | 28.03 | −12.88 | 17.56 | 7.91 | 9.23 | 0.35 | 15.41 | 6.68 | 17.92 | 0.30 | 10.15 | 6.76 | |

| 66° | 27.87 | −12.20 | 16.67 | 7.52 | 7.99 | 0.19 | 16.08 | 6.52 | 17.30 | −0.03 | 9.99 | 6.69 | |

| 70° | 31.38 | −9.05 | 18.31 | 9.55 | 5.90 | −0.07 | 15.91 | 10.06 | 17.57 | 0.84 | 11.27 | 9.78 | |

| 20 mm | Exp | 25.80 | −15.40 | 17.12 | 6.90 | 7.22 | −0.38 | 13.51 | 7.95 | 18.03 | 0.52 | 12.47 | 9.03 |

| 60° | 10.34 | −6.27 | 11.65 | 6.94 | 1.26 | −1.19 | 7.22 | 7.20 | 8.61 | −0.73 | 6.19 | 5.69 | |

| 62.5° | 16.27 | −8.35 | 14.87 | 6.39 | 6.20 | −0.43 | 10.63 | 5.91 | 10.07 | −0.90 | 8.87 | 6.11 | |

| 64° | 15.99 | −9.42 | 14.39 | 6.54 | 6.12 | 0.47 | 10.79 | 5.17 | 9.97 | −0.41 | 8.99 | 5.00 | |

| 65° | 19.25 | −9.39 | 13.38 | 6.49 | 4.98 | 0.11 | 11.28 | 6.05 | 11.40 | −0.19 | 8.86 | 5.82 | |

| 66° | 20.26 | −9.76 | 13.57 | 6.16 | 6.43 | 0.25 | 11.13 | 5.80 | 11.31 | −0.40 | 8.74 | 5.17 | |

| 70° | 21.30 | −6.57 | 14.71 | 7.99 | 7.66 | −0.80 | 11.08 | 7.45 | 13.24 | 0.08 | 9.94 | 7.55 | |

| 90 mm | Exp | 11.52 | 11.18 | 4.86 | 4.86 | 0.23 | −0.26 | 7.12 | 7.07 | 10.94 | −2.05 | 7.82 | 7.66 |

| 60° | 6.71 | 6.59 | 5.76 | 5.75 | 1.58 | 1.08 | 7.50 | 7.47 | 8.42 | 1.48 | 8.21 | 8.07 | |

| 62.5° | 8.71 | 8.68 | 6.36 | 6.22 | 1.58 | −1.24 | 6.84 | 6.60 | 8.32 | −1.51 | 6.29 | 6.23 | |

| 64° | 6.39 | 6.38 | 4.86 | 4.54 | 1.08 | 0.64 | 5.61 | 5.49 | 6.91 | −0.39 | 6.73 | 6.73 | |

| 65° | 6.18 | 6.16 | 4.48 | 4.48 | 1.59 | 0.26 | 4.58 | 4.44 | 6.46 | −0.65 | 4.64 | 4.64 | |

| 66° | 5.60 | 5.59 | 3.85 | 3.80 | 1.51 | 1.47 | 4.54 | 4.51 | 5.82 | 0.28 | 4.18 | 4.18 | |

| 70° | 5.93 | 5.93 | 4.17 | 4.10 | 0.95 | 0.15 | 4.76 | 4.58 | 5.71 | 0.12 | 4.67 | 4.56 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sehole, H.A.H.; Mehdi, G.; Riaz, R.; Jabbar, A.U.; Maqsood, A.; De Giorgi, M.G. Quantifying Swirl Number Effects on Recirculation Zones and Vortex Dynamics in a Dual-Swirl Combustor. Energies 2025, 18, 6568. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246568

Sehole HAH, Mehdi G, Riaz R, Jabbar AU, Maqsood A, De Giorgi MG. Quantifying Swirl Number Effects on Recirculation Zones and Vortex Dynamics in a Dual-Swirl Combustor. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6568. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246568

Chicago/Turabian StyleSehole, Hafiz Ali Haider, Ghazanfar Mehdi, Rizwan Riaz, Absaar Ul Jabbar, Adnan Maqsood, and Maria Grazia De Giorgi. 2025. "Quantifying Swirl Number Effects on Recirculation Zones and Vortex Dynamics in a Dual-Swirl Combustor" Energies 18, no. 24: 6568. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246568

APA StyleSehole, H. A. H., Mehdi, G., Riaz, R., Jabbar, A. U., Maqsood, A., & De Giorgi, M. G. (2025). Quantifying Swirl Number Effects on Recirculation Zones and Vortex Dynamics in a Dual-Swirl Combustor. Energies, 18(24), 6568. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246568