Economic and Efficiency Impacts of Repartition Keys in Renewable Energy Communities: A Simulation-Based Analysis for the Portuguese Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Key of Repartition Under Portuguese Regulation

2.1. KoRs with Static Coefficients

2.2. KoRs with Dynamic Coefficients

2.3. Hybrid KoRs

3. Methodology

3.1. Community Scenarios and Participant Configuration

Storage Systems Characterization

3.2. Energy Storage Management Strategy

3.3. Data Profiles

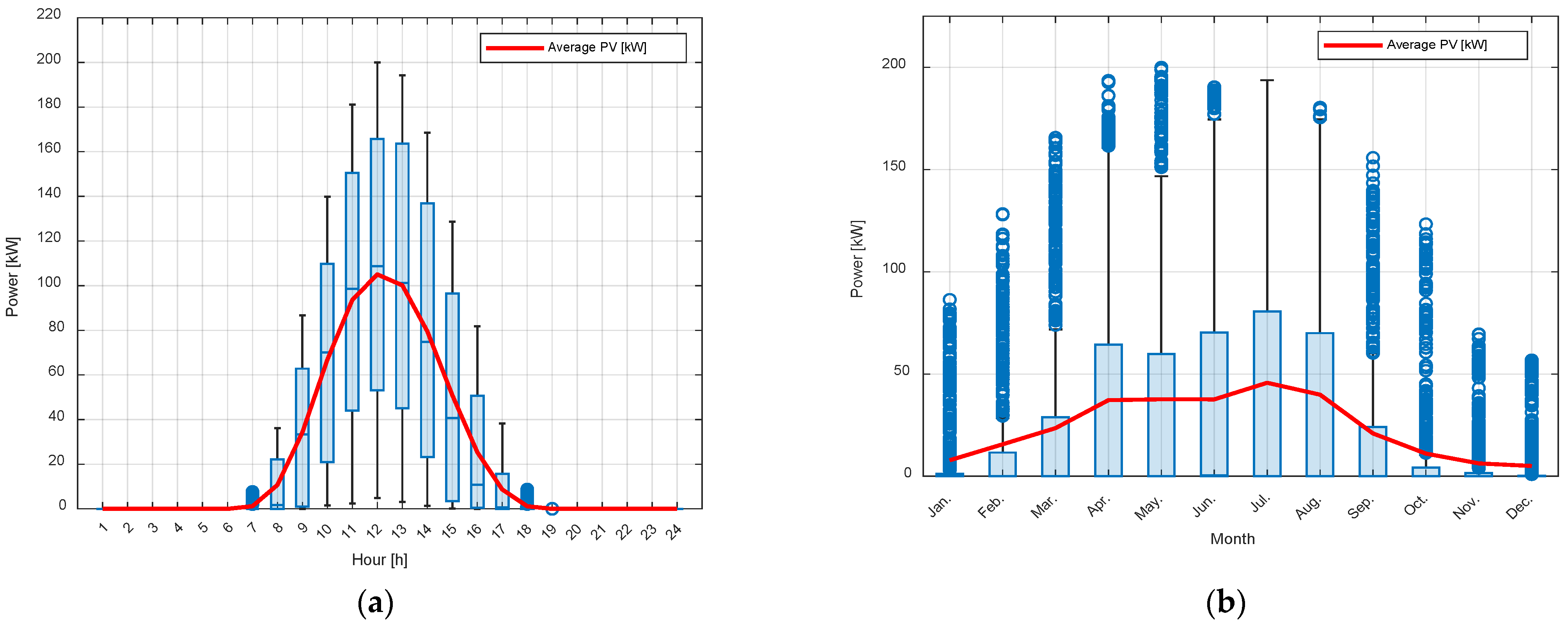

3.3.1. PV Profiles

3.3.2. Load Profiles

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

3.4.1. Annual Savings

3.4.2. Savings per Kilowatt-Hour

3.4.3. Payback Period

3.4.4. Self-Sufficiency Ratio (SSR) and Self-Consumption Ratio (SCR)

3.4.5. Energy Storage Systems State of Health (SOH)

4. Simulation Results

- A small-scale scenario involving 3 randomly selected participants from the dataset of 30 participants;

- A large-scale scenario comprising the entire set of 30 participants.

- Without storage systems;

- With stationary batteries only (without EVs);

- With full storage systems integration (with stationary batteries and EVs).

4.1. Small-Scale Community Scenario

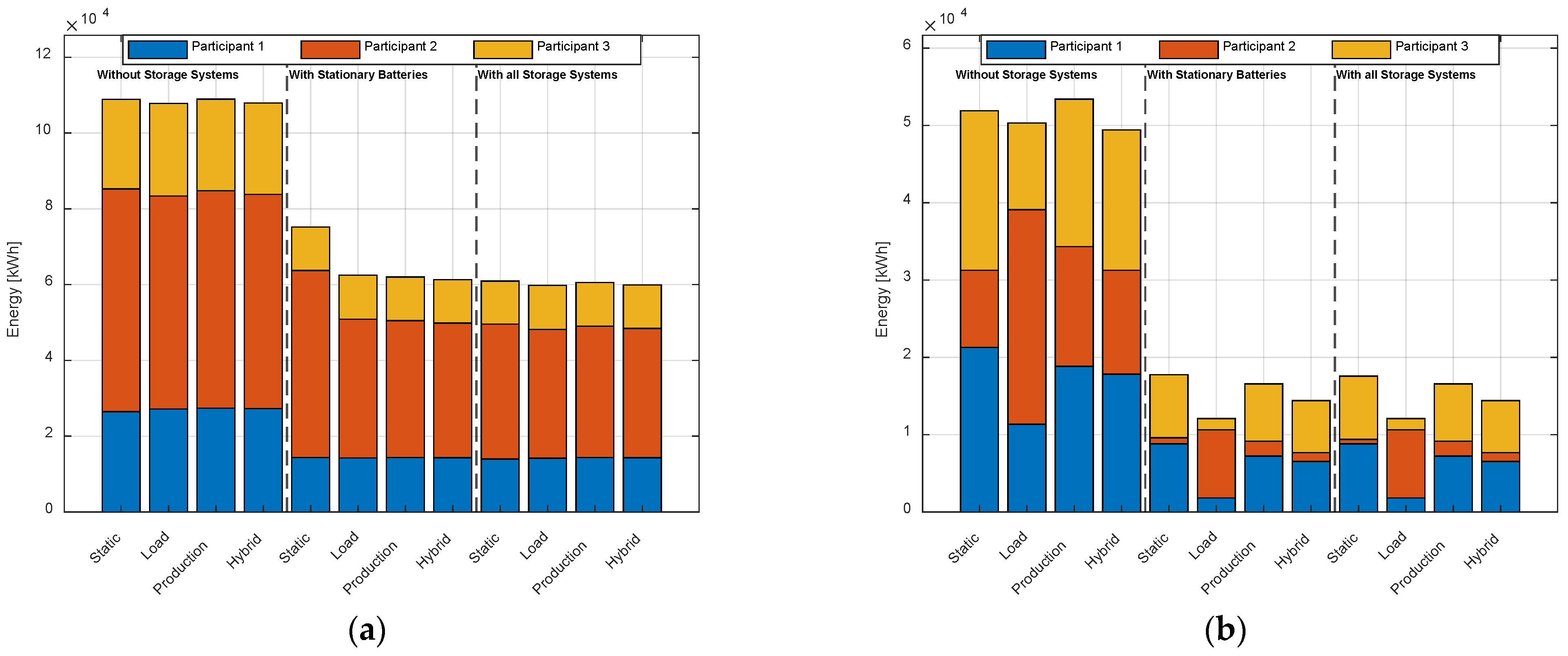

4.1.1. Without Storage Systems

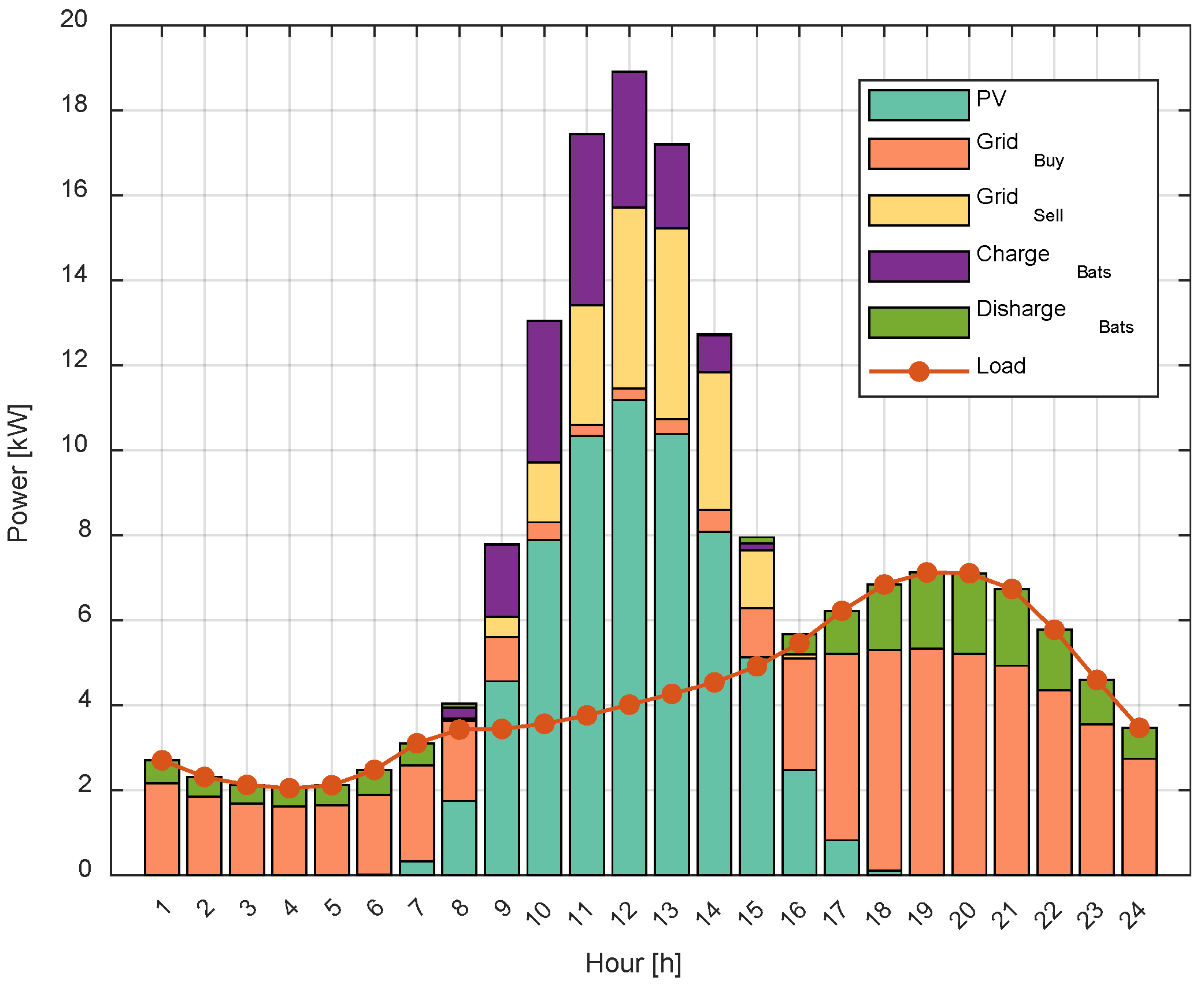

4.1.2. With Stationary Batteries

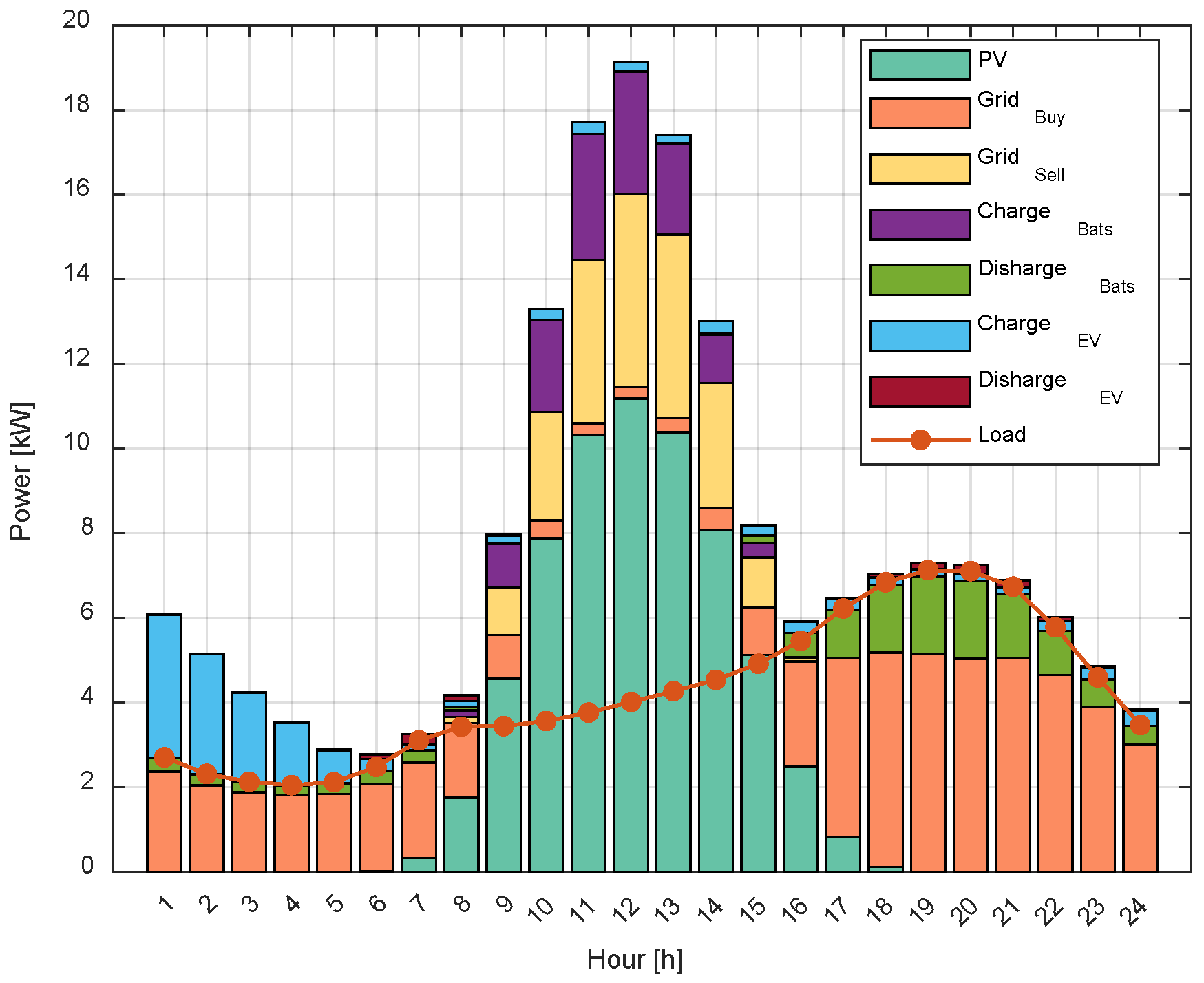

4.1.3. With Stationary Batteries and Electric Vehicles

4.1.4. Results Analysis and Discussion

4.2. Large-Scale Community Scenario

4.2.1. Without Storage Systems

4.2.2. With Stationary Batteries

4.2.3. With Stationary Batteries and Electric Vehicles

4.2.4. Results Analysis and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement. In Proceedings of the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UNFCCC, Paris, France, 30 November–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Msigwa, G.; Yang, M.; Osman, A.I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.S. Strategies to Achieve a Carbon Neutral Society: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2277–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M. Assessing Energy Trilemma-Related Policies: The World’s Large Energy User Evidence. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowicz, J.; Lyulyov, O.; Miskiewicz, R. Clean and Affordable Energy within Sustainable Development Goals: The Role of Governance Digitalization. Energies 2022, 15, 9571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.; Marques, C.; Pombo, J.; Mariano, S.; Calado, M.D.R. Optimal Sizing of Renewable Energy Communities: A Multiple Swarms Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization Approach. Energies 2023, 16, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Bousoño, A.; Sierra, J. Empowering Citizens for Energy Communities in the European Union. In An Agenda for Sustainable Development Research; World Sustainability Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Clean Energy for All Europeans; European Union, Ed.; Publications Office: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Council Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity and Amending Directive 2012/27/EU; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Council Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Recast); European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; D’angola, A. A Review of Renewable Energy Communities: Concepts, Scope, Progress, Challenges, and Recommendations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.P.D.; Pombo, J.A.N.; Mariano, S.J.P.S.; Calado, M.R.A. Plug-and-Play Framework for Assessment of Renewable Energy Community Strategies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 29811–29829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustika, A.D.; Rigo-Mariani, R.; Debusschere, V.; Pachurka, A. A Two-Stage Management Strategy for the Optimal Operation and Billing in an Energy Community with Collective Self-Consumption. Appl. Energy 2022, 310, 118484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, A.; Neumann, C.; Manner, H. Exploring Sharing Coefficients in Energy Communities: A Simulation-Based Study. Energy Build. 2023, 297, 113447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Energy of the European Commission. Energy Sharing for Energy Communities—A Reference Guide; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Repubblica Italiana. Decreto Legislativo 8 Novembre 2021, n. 199—Attuazione della Direttiva (UE) 2018/2001 del Parlamento Europeo e del Consiglio, del 11 Dicembre 2018, sulla Promozione dell’uso Dell’energia da Fonti Rinnovabili; Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- República Portuguesa. Decreto-Lei n.o 162/2019 de 25 de Outubro—Estabelece o Regime Jurídico Aplicável Ao Autoconsumo de Energia Elétrica; Presidency of the Council of Ministers: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Frieden, D.; Tuerk, A.; Antunes, A.R.; Athanasios, V.; Chronis, A.G.; D’herbemont, S.; Kirac, M.; Marouço, R.; Neumann, C.; Catalayud, E.P.; et al. Are We on the Right Track? Collective Self-Consumption and Energy Communities in the European Union. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- República Portuguesa. Decreto-Lei n.o 15/2022 de 14 de Janeiro—Estabelece a Organização e o Funcionamento Do Sistema Elétrico Nacional; Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno, J.Á.; Llera-Sastresa, E.; Scarpellini, S. A Heuristic Approach to the Decision-Making Process of Energy Prosumers in a Circular Economy. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawinkler, A.; Breitenecker, R.J.; Maresch, D. Heuristic Decision-Making in the Green Energy Context:Bringing Together Simple Rules and Data-Driven Mathematical Optimization. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, V.; Janik, P.; Jasinski, M.; Guerrero, J.M.; Leonowicz, Z. Microgrid Energy Management Using Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithms. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 134, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Neagu, B.C.; Grigoras, G.; Scarlatache, F.; Gavrilas, M. A Metaheuristic Algorithm for Flexible Energy Storage Management in Residential Electricity Distribution Grids. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga Palou, J.T.; Serrano González, J.; Riquelme Santos, J.M. Estimation of Energy Distribution Coefficients in Collective Self-Consumption Using Meta-Heuristic Optimization Techniques. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosic, A.; Stadler, M.; Mansoor, M.; Zellinger, M. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Based Optimization Strategies for Renewable Energy Communities. Energy 2021, 237, 121559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Barkouki, B.; Laamim, M.; Rochd, A.; Chang, J.W.; Benazzouz, A.; Ouassaid, M.; Kang, M.; Jeong, H. An Economic Dispatch for a Shared Energy Storage System Using MILP Optimization: A Case Study of a Moroccan Microgrid. Energies 2023, 16, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. AI-Driven Battery Ageing Prediction with Distributed Renewable Community and E-Mobility Energy Sharing. Renew. Energy 2024, 225, 120280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jnr, B.A. Enabling Sustainable Energy Sharing and Tracking for Rural Energy Communities in Emerging Economies. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, P.; Nunes, H.; Pombo, J.; Calado, M.D.R.; Mariano, S. Daily Operation Optimization of a Hybrid Energy System Considering a Short-Term Electricity Price Forecast Scheme. Energies 2019, 12, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Soares, J.; Limmer, S.; Aliyan, E.; Faia, R.; Lezama, F.; Ramos, S.; Vale, Z. Community-Based Energy Sharing Using Game Theory Approaches for Benefit Distribution. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems Applications to Power Systems (ISAP), Budapest, Hungary, 16–19 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, A.Y.; Li, P.; Ding, M. Optimized Shared Energy Storage in a Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading Market: Two-Stage Strategic Model Regards Bargaining and Evolutionary Game Theory. Renew. Energy 2024, 224, 120190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Vale, Z. Costless Renewable Energy Distribution Model Based on Cooperative Game Theory for Energy Communities Considering Its Members’ Active Contributions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Wang, S.; Lv, Y.; Mu, R.; Fo, J.; Zhang, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, C. Domain Knowledge-Enhanced Graph Reinforcement Learning Method for Volt/Var Control in Distribution Networks. Appl. Energy 2025, 398, 126409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengyuan, W.; Fengzhang, L.; Chengshan, W.; Yunqiang, L.; Ranfeng, M.; Jiacheng, F.; Lukun, G. Collaborative Configuration Optimization of Soft Open Points and Distributed Multi-Energy Stations with Spatiotemporal Coordination and Complementarity. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 13, 2086–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, F.; Fo, J.; Lv, Y.; Wang, C. Two-Stage Spatiotemporal Decoupling Configuration of SOP and Multi-Level Electric-Hydrogen Hybrid Energy Storage Based on Feature Extraction for Distribution Networks with Ultra-High DG Penetration. Appl. Energy 2025, 398, 126438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Hakvoort, R.A.; Lukszo, Z. Cost Allocation in Integrated Community Energy Systems—Performance Assessment. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuto, F.D.; Lanzini, A. Energy-Sharing Mechanisms for Energy Community Members under Different Asset Ownership Schemes and User Demand Profiles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzanic, M.; Capuder, T. Is Dynamic Energy Sharing Really Necessary? The Case Study of Collective Renewable Self-Consumers in Croatia. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES Conference on Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Middle East, ISGT Middle East, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12–15 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ogando-Martínez, A.; García-Santiago, X.; Díaz García, S.; Echevarría Camarero, F.; Blázquez Gil, G.; Carrasco Ortega, P. Optimization of Energy Allocation Strategies in Spanish Collective Self-Consumption Photovoltaic Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissan 2025 Nissan LEAF Features: Range, Charging, Battery & More. Available online: https://www.nissanusa.com/vehicles/electric-cars/2025-leaf/features.html (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Malya, P.P.; Fiorini, L.; Rouhani, M.; Aiello, M. Electric Vehicles as Distribution Grid Batteries: A Reality Check. Energy Inform. 2021, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Woo, J.R.; Kwak, K. Unlocking Peak Shaving: How EV Driver Heterogeneity Shapes V2G Potential. Energy 2025, 329, 136773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Joint Research Centre Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS). Available online: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wilcox, S.; Marion, W. Users Manual for TMY3 Data Sets (Revised); National Renewable Energy Lab.: Golden, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso-Burgos, Á.; Ribó-Pérez, D.; Alcázar-Ortega, M.; Gómez-Navarro, T. Local Energy Communities in Spain: Economic Implications of the New Tariff and Variable Coefficients. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, H.; Lopes, R.A.; Martins, J.; Silva, F.N.; Fialho, L.; Bilo, N. Assessment of Energy Sharing Coefficients under the New Portuguese Renewable Energy Communities Regulation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, A.; Vahidinasab, V.; Aghaei, J. Enabling Vehicle-to-Grid and Grid-to-Vehicle Transactions via a Robust Home Energy Management System by Considering Battery Aging. In Proceedings of the SEST 2021—4th International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies, Vaasa, Finland, 6–8 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Technology | Lithium-Ion |

| Storage Capacity | 30 kWh |

| Maximum Number of Cycles ) | 4000 |

| Replacement Cost | €5000 |

| Depth of Discharge | 0.8 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Model | Nissan Leaf e+ (2025) |

| Battery Technology | Lithium-Ion |

| Storage Capacity | 60 kWh |

| Maximum Number of Cycles () | 4000 |

| Replacement Cost | €10,000 |

| Depth of Discharge | 0.8 |

| Metrics | Annual Savings (€) | Savings per kWh (€) | Payback Period | SSR | SCR | Grid Buy | Grid Sell | SOH Bats | SOH EVs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoRs | ||||||||||

| Static KoR | 3061.9 | 0.0205 | 11.27 | 0.436 | 0.269 | 1.09 × 105 | 5.19 × 104 | - | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Load | 3141.1 | 0.0211 | 10.98 | 0.448 | 0.276 | 1.08 × 105 | 5.03 × 104 | - | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Production | 3058.7 | 0.0205 | 11.28 | 0.436 | 0.269 | 1.09 × 105 | 5.34 × 104 | - | - | |

| Hybrid KoR-Production/Load | 3133.3 | 0.0210 | 11.01 | 0.447 | 0.276 | 1.08 × 105 | 4.94 × 104 | - | - | |

| Metrics | Annual Savings (€) | Savings per kWh (€) | Payback Period | SSR | SCR | Grid Buy (kWh) | Grid Sell (kWh) | SOH Bats (%) | SOH EVs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoRs | ||||||||||

| Static KoR | 6856.7 | 0.0460 | 5.03 | 0.803 | 0.496 | 7.52 × 104 | 1.78 × 104 | 96.03 | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Load | 8198.4 | 0.0550 | 4.21 | 0.940 | 0.581 | 6.25 × 104 | 1.21 × 104 | 94.74 | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Production | 8306.9 | 0.0557 | 4.15 | 0.946 | 0.584 | 6.20 × 104 | 1.66 × 104 | 94.57 | - | |

| Hybrid KoR-Production/Load | 8351.2 | 0.0560 | 4.13 | 0.953 | 0.588 | 6.13 × 104 | 1.44 × 104 | 94.61 | - | |

| Metrics | Annual Savings (€) | Savings per kWh (€) | Payback Period | SSR | SCR | Grid Buy (kWh) | Grid SELL (kWh) | SOH Bats (%) | SOH EVs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoRs | ||||||||||

| Static KoR | 8481.4 | 0.0569 | 4.07 | 0.958 | 0.591 | 6.09 × 104 | 1.76 × 104 | 94.55 | 99.92 | |

| Dynamic KoR-Load | 8557.3 | 0.0574 | 4.03 | 0.970 | 0.599 | 5.98 × 104 | 1.21 × 104 | 94.59 | 99.92 | |

| Dynamic KoR-Production | 8503.9 | 0.0571 | 4.06 | 0.961 | 0.594 | 6.06 × 104 | 1.66 × 104 | 94.57 | 99.92 | |

| Hybrid KoR-Production/Load | 8546.7 | 0.0573 | 4.04 | 0.969 | 0.598 | 5.99 × 104 | 1.44 × 104 | 94.61 | 99.92 | |

| Metrics | Annual Savings (€) | Savings per kWh (€) | Payback Period | SSR (%) | SCR (%) | Grid Buy (kWh) | Grid Sell (kWh) | SOH Bats (%) | SOH EVs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoRs | ||||||||||

| Static KoR | 22,463.7 | 0.0190 | 15.36 | 0.245 | 0.343 | 8.90 × 105 | 5.54 × 105 | - | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Load | 22,559.4 | 0.0191 | 15.29 | 0.247 | 0.345 | 8.89 × 105 | 5.46 × 105 | - | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Production | 22,435.7 | 0.0190 | 15.38 | 0.245 | 0.343 | 8.91 × 105 | 5.69 × 105 | - | - | |

| Hybrid KoR-Production/Load | 22,725.2 | 0.0193 | 15.18 | 0.249 | 0.348 | 8.87 × 105 | 5.51 × 105 | - | - | |

| Metrics | Annual Savings (€) | Savings per kWh (€) | Payback Period | SSR | SCR | Grid Buy (kWh) | Grid Sell (kWh) | SOH Bats (%) | SOH EVs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoRs | ||||||||||

| Static KoR | 60,684.6 | 0.0514 | 5.69 | 0.534 | 0.747 | 5.50 × 105 | 2.18 × 105 | 96.05 | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Load | 64,385.8 | 0.0546 | 5.36 | 0.563 | 0.787 | 5.16 × 105 | 1.94 × 105 | 95.68 | - | |

| Dynamic KoR-Production | 64,865.8 | 0.0550 | 5.32 | 0.565 | 0.791 | 5.13 × 105 | 2.18 × 105 | 95.63 | - | |

| Hybrid KoR-Production/Load | 65,029.9 | 0.0551 | 5.31 | 0.567 | 0.794 | 5.11 × 105 | 2.06 × 105 | 95.64 | - | |

| Metrics | Annual Savings (€) | Savings per kWh (€) | Payback Period | SSR | SCR | Grid Buy | Grid Sell | SOH Bats (%) | SOH EVs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoRs | ||||||||||

| Static KoR | 65,721.3 | 0.0557 | 5.25 | 0.570 | 0.798 | 5.07 × 105 | 2.16 × 105 | 95.63 | 99.96 | |

| Dynamic KoR-Load | 65,910.8 | 0.0559 | 5.23 | 0.572 | 0.800 | 5.05 × 105 | 1.94 × 105 | 95.63 | 99.96 | |

| Dynamic KoR-Production | 65,797.9 | 0.0558 | 5.24 | 0.571 | 0.799 | 5.07 × 105 | 2.18 × 105 | 95.63 | 99.96 | |

| Hybrid KoR-Production/Load | 65,955.8 | 0.0559 | 5.23 | 0.573 | 0.801 | 5.04 × 105 | 2.06 × 105 | 95.64 | 99.96 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faria, J.; Figueira, J.; Pombo, J.; Mariano, S.; Calado, M. Economic and Efficiency Impacts of Repartition Keys in Renewable Energy Communities: A Simulation-Based Analysis for the Portuguese Context. Energies 2025, 18, 6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246567

Faria J, Figueira J, Pombo J, Mariano S, Calado M. Economic and Efficiency Impacts of Repartition Keys in Renewable Energy Communities: A Simulation-Based Analysis for the Portuguese Context. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246567

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaria, João, Joana Figueira, José Pombo, Sílvio Mariano, and Maria Calado. 2025. "Economic and Efficiency Impacts of Repartition Keys in Renewable Energy Communities: A Simulation-Based Analysis for the Portuguese Context" Energies 18, no. 24: 6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246567

APA StyleFaria, J., Figueira, J., Pombo, J., Mariano, S., & Calado, M. (2025). Economic and Efficiency Impacts of Repartition Keys in Renewable Energy Communities: A Simulation-Based Analysis for the Portuguese Context. Energies, 18(24), 6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246567