Investigation on Multi-Load Reaction Characteristics and Field Synergy of a Diesel Engine SCR System Based on an Eley-Rideal and Langmuir-Hinshelwood Dual-Mechanism Coupled Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Method and Data Accuracy

2.2. Experimental Equipment

2.3. Urea Injection Control

2.4. Data Acquisition

2.5. Simulation Physics Model and Basic Reaction Equation

2.5.1. Physics Model

2.5.2. Energy Model

2.5.3. Pressure Drop Model

2.5.4. Simulation Simplification Assumption

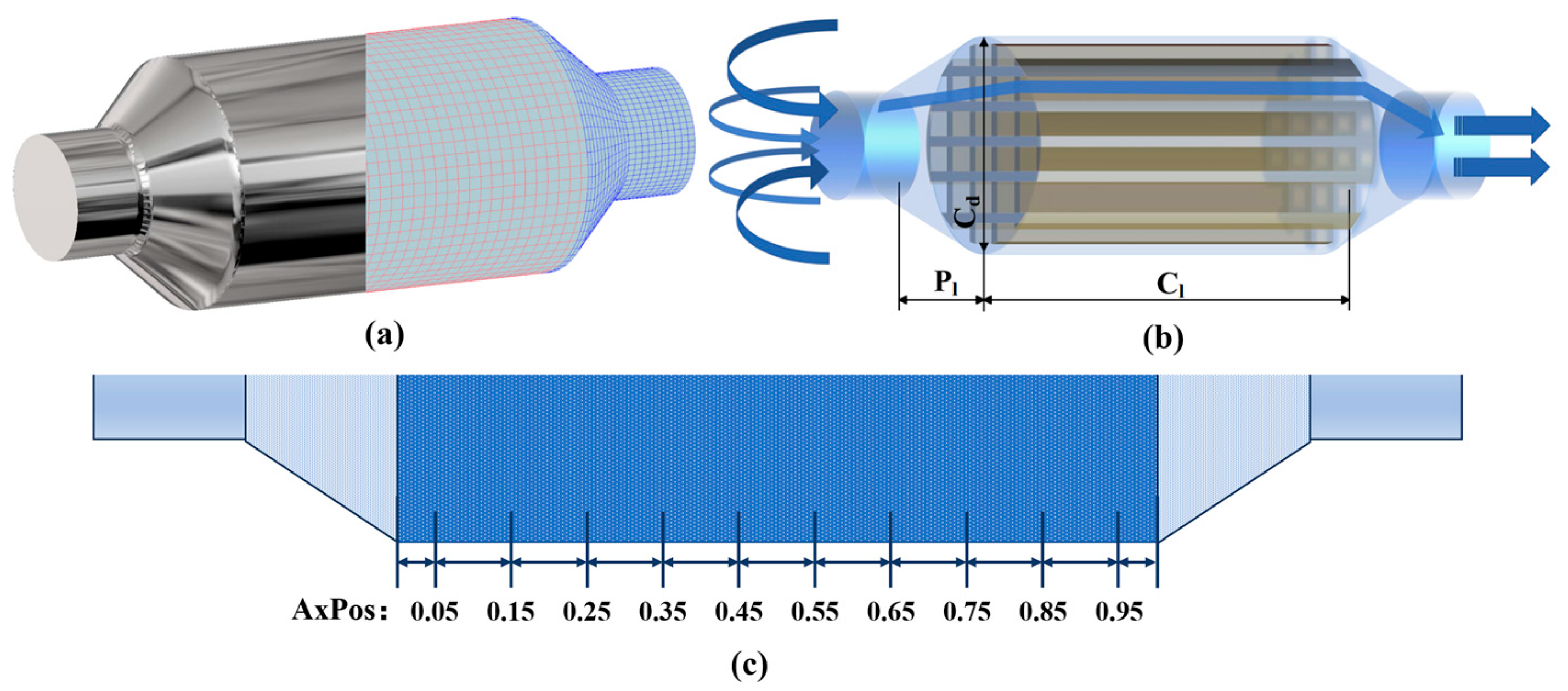

2.6. Grids Independence Analysis

2.7. Construction of Reaction Mechanism and Verification of Model

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Boundary and Initial Conditions Setting

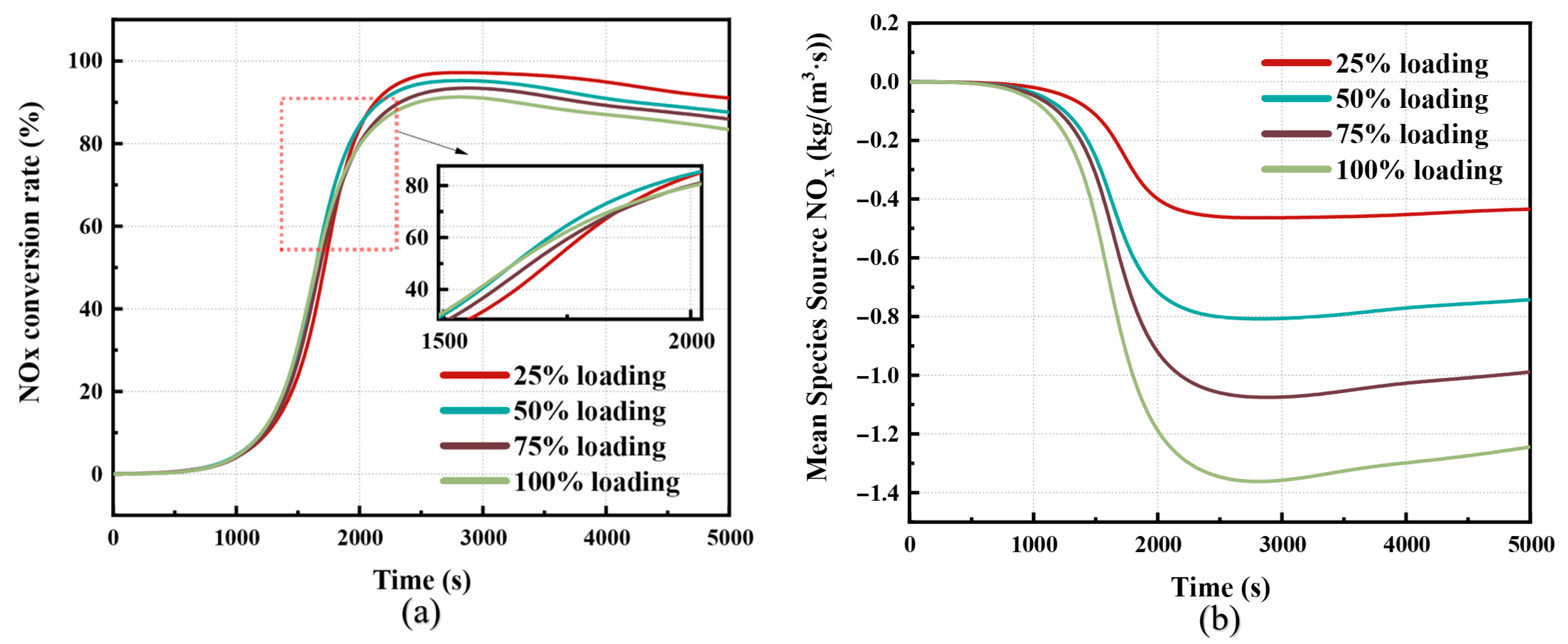

3.2. Analysis of SCR Catalytic Characteristics

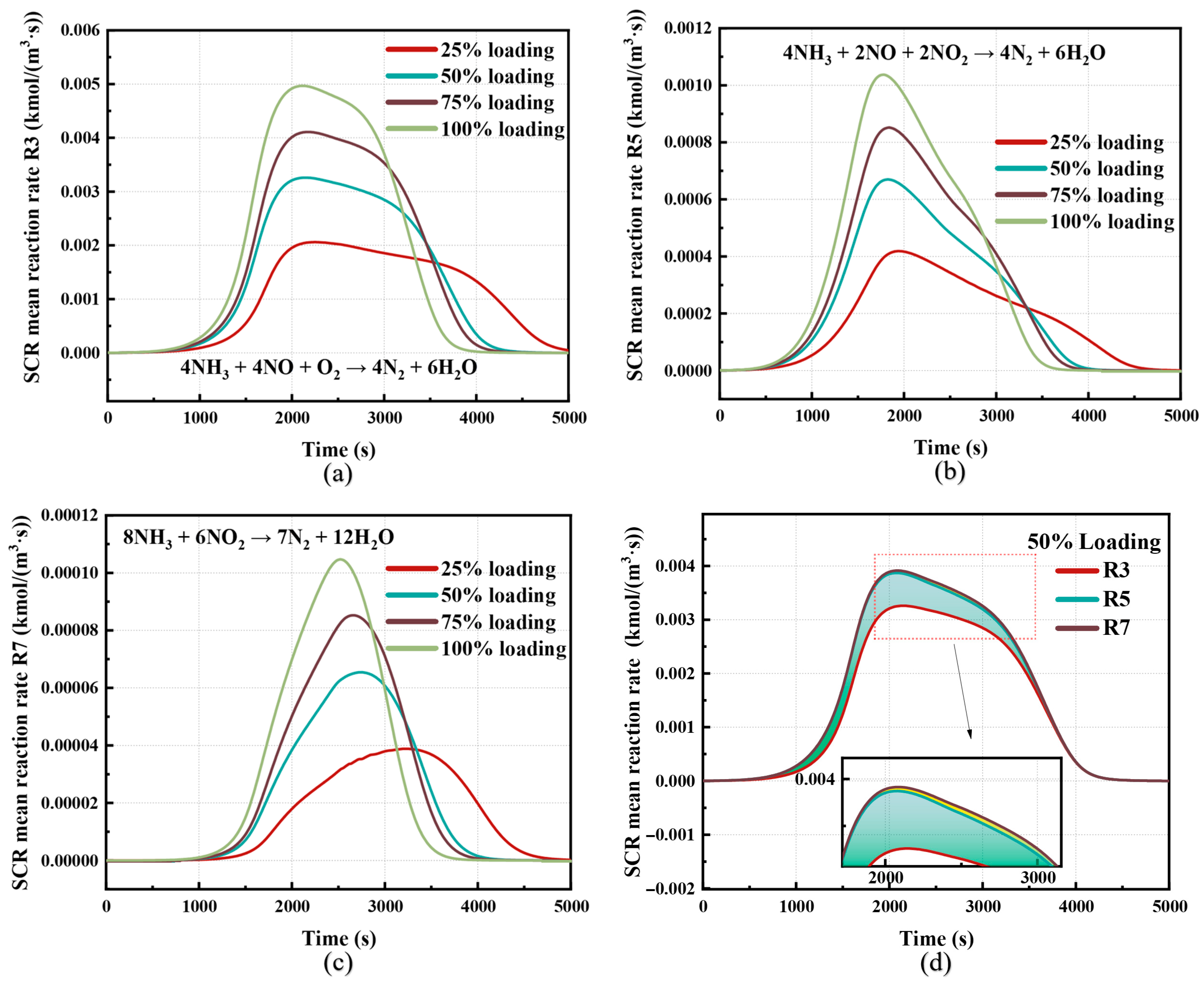

3.3. Analysis of Dual Mechanism Dynamic Reaction Process

3.4. Analysis of NH3 Loading Situation

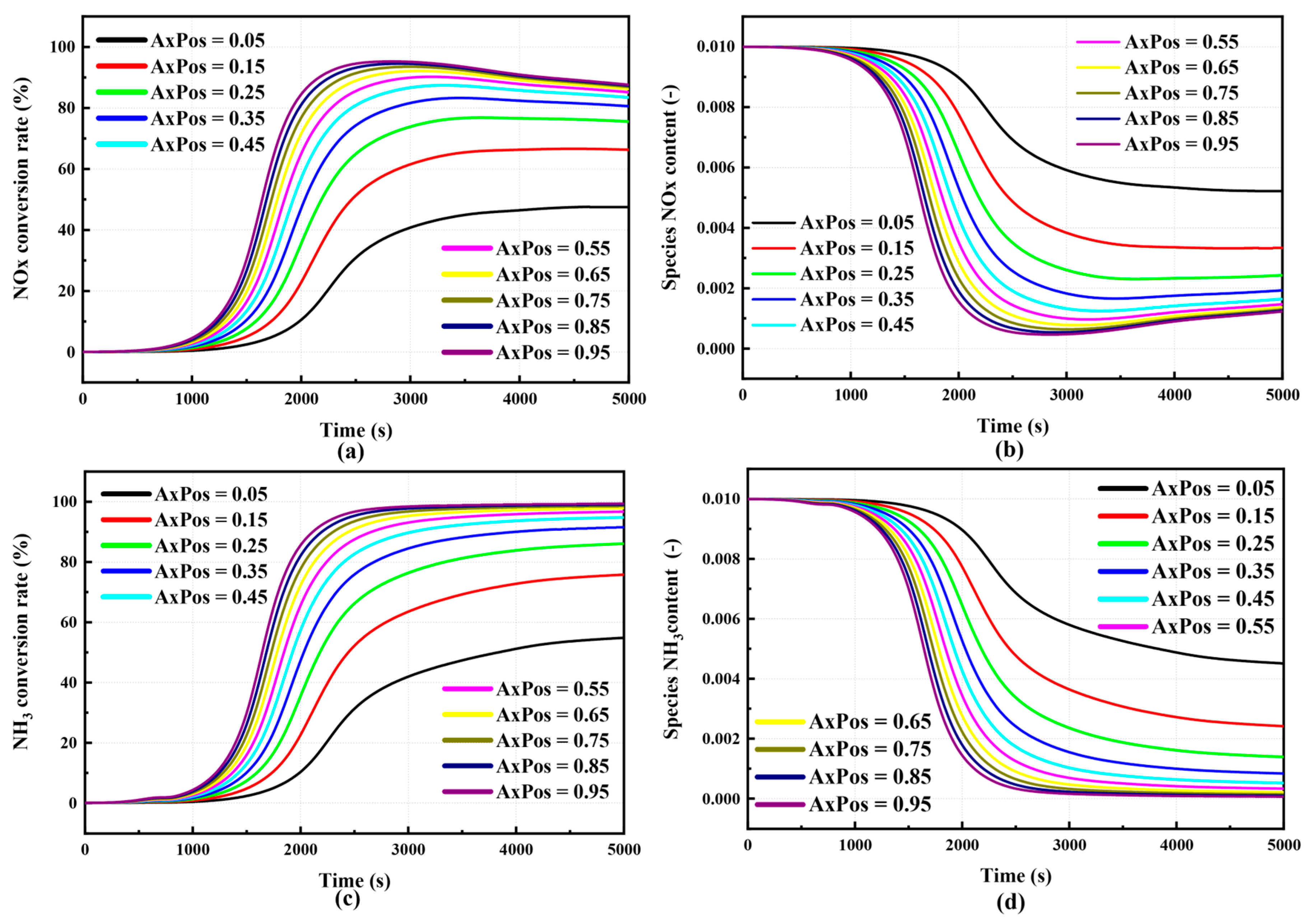

3.4.1. Analysis of SCR Catalytic Efficiency of Different AxPos

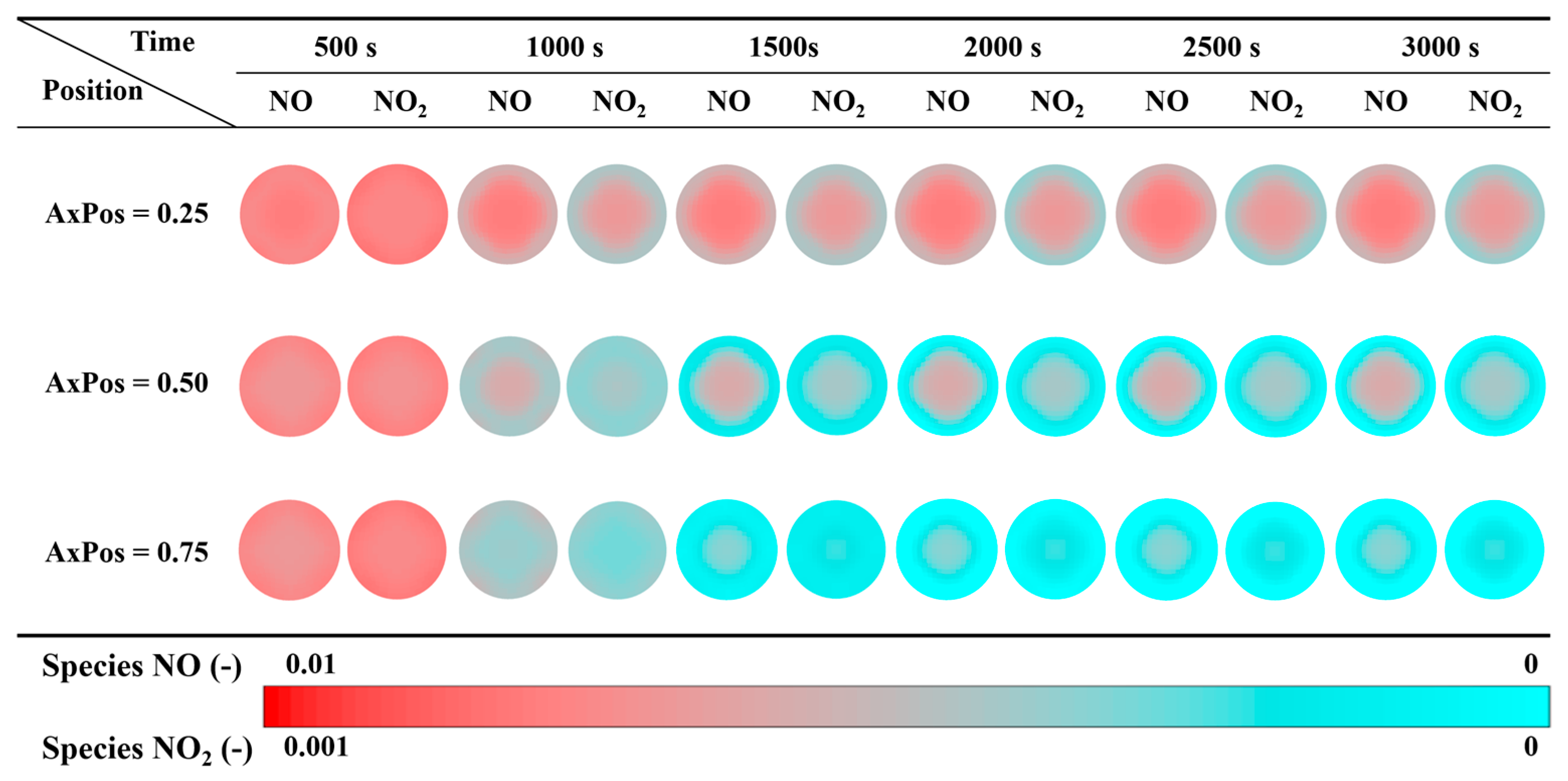

3.4.2. Performance of Species Concentration Field

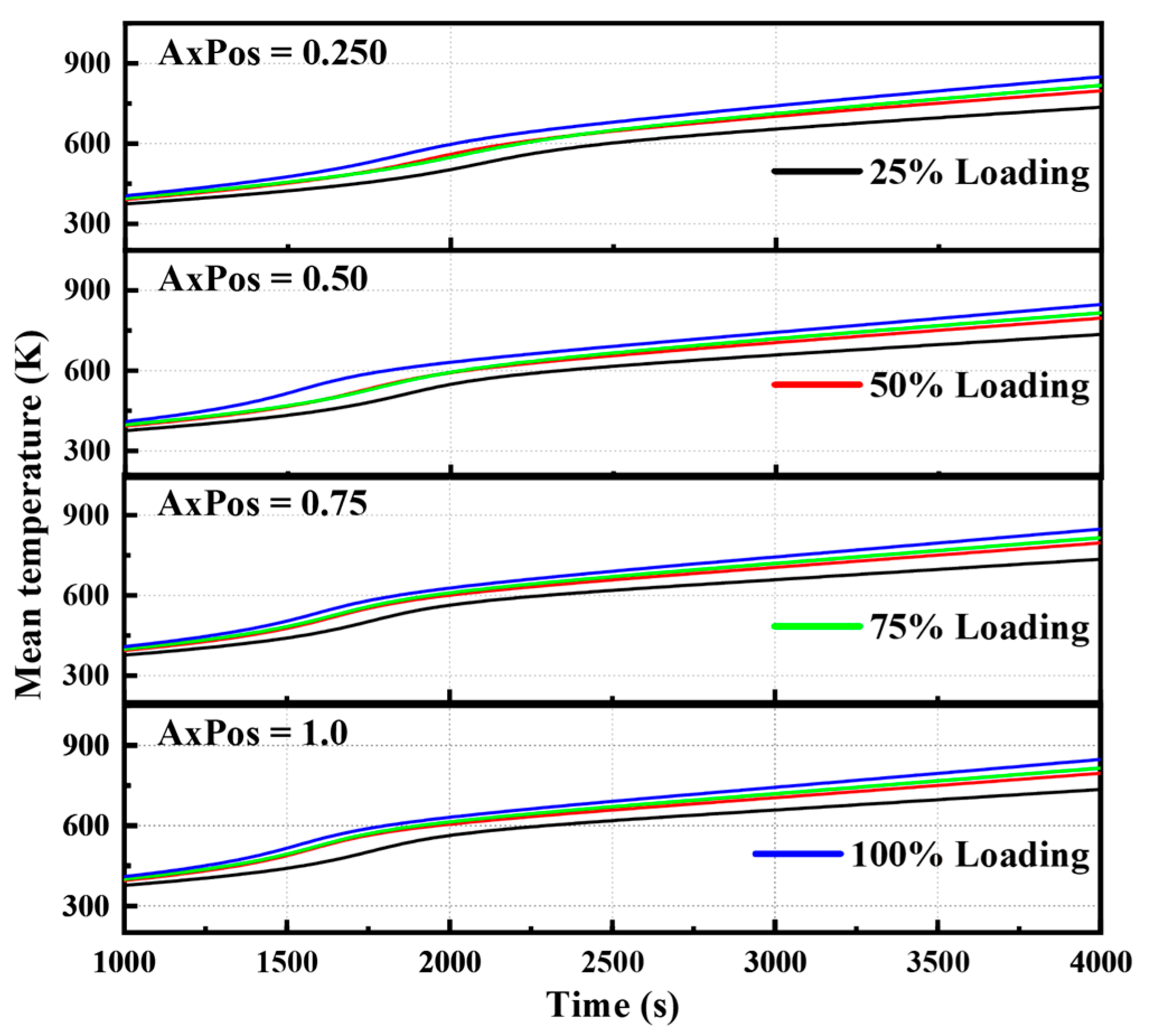

3.5. Analysis of SCR Temperature Characteristics

3.5.1. Temperature Variation Characteristics of Catalysts

3.5.2. Temperature Field Distribution of Catalyst

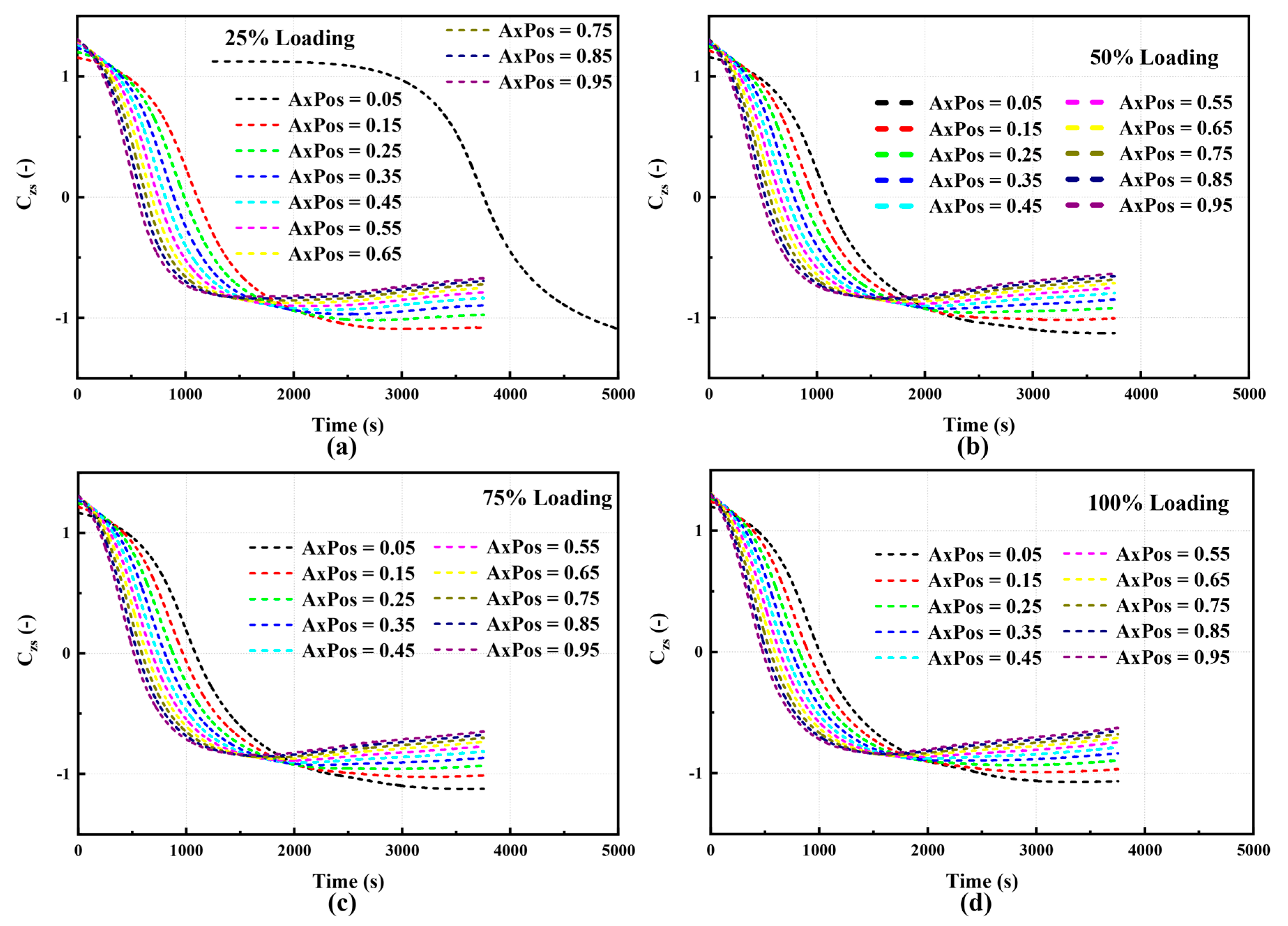

3.6. Field Synergy Analysis of Concentration Temperature

3.6.1. Field Synergy Method

3.6.2. Building Field Synergy Method

3.6.3. Results of Field Synergy Analysis

4. Conclusions

- The exhaust temperature and flow rate are key factors affecting the catalytic characteristics of SCR systems. The high temperature caused by high load will accelerate the ignition rate, while low load relies on long residence time to improve catalytic efficiency.

- NH3 loading and NOx concentration were synergistically regulated by load and axial position, the concentration and conversion efficiency were higher in the front-end region, while lower in the rear-end region due to mass transfer lag, showing obvious spatial gradient and reaction coupling characteristics.

- The catalyst temperature evolution was jointly determined by load and axial position. High load and rear-end positions produced a significant heat accumulation effect, resulting in higher temperature rise rates and final temperatures, which enhance the reaction kinetics process.

- The field synergy analysis showed that a strong negative correlation was maintained across the entire load range. Axial consistency was enhanced with the increase in load, and the synergy curves tended to overlap from dispersion. This indicated that heat-mass coupling and transport were more matched under medium and high loads, and the reaction zone was more stable. Specifically, temperature led with a large time lag at 25% load; the time lag was significantly shortened at 50% load; near synchronization was achieved at 75% load; and a slight NOx lead appeared at 100% load.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ponce, J.; Barbier, A.; Palau, C.E.; Guardiola, C. A novel approach in constructing virtual real driving emission trips through genetic algorithm optimization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemitallah, M.A.; Nabhan, M.A.; Alowaifeer, M.; Haeruman, A.; Alzahrani, F.; Habib, M.A.; Elshafei, M.; Abouheaf, M.I.; Aliyu, M.; Alfarraj, M. Artificial intelligence for control and optimization of boilers’ performance and emissions: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 138109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isles, P.D.F. A random forest approach to improve estimates of tributary nutrient loading. Water Res. 2024, 248, 120876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, S.; Dinesha, P.; Dasari, H. Cu/BEA catalysts for the selective catalytic reduction of engine-out NOx emissions: Experimental and kinetic investigations. Fuel 2024, 357, 130041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkinahamira, F.; Sun, S.; Zhu, R. Core-shell In/H-Beta@Ce catalyst with enhanced sulfur and water tolerance for selective catalytic reduction of NOx by CH4. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, W.; Song, X.; Hua, Y.; Liu, C.; Lian, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, C. Effect of cerium-zirconium oxide-loaded red mud on the selective catalytic reduction of NO in downhole diesel vehicle exhaust. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 368, 125690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyna, M.; Legutko, P.; Marzec, M.; Sojka, Z. Influence of zeolite framework, copper speciation, and water on NO2 and N2O formation during NH3-SCR. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 361, 124632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, M.; Suharbiansah, R.S.R.; Góra-Marek, K.; Rotko, M.; Ruszak, M.; Fernadi Lukman, M.; Palčić, A.; Denecke, R.; Bertmer, M.; Grams, J.; et al. NH3-SCR-DeNOx Activity of Cu-Containing Commercial Zeolite Y. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 17075–17085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, M.; Osorio Hernández, A. Selective Catalytic Reduction of Nitrogen Oxides with Hydrogen (H2-SCR-DeNOx) over Platinum-Based Catalysts. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202400977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemoto, M.; Fujinuma, H.; Sugawara, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Iyoki, K.; Okubo, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Wakihara, T. Superior low temperature activity over α-MnO2/β-MnOOH catalyst for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with ammonia. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 35498–35504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkhaneh, S.; Latifi, S.M.; Kashi, E.; Salehirad, A. Promotional effects of cerium and titanium on NiMn2O4 for selective catalytic reduction of NO by NH3. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2023, 21, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushar, M.S.H.K.; Mannan, M.I.; Azmain, A. Exhaust gas after treatment using air preheating and selective catalytic reduction by urea to reduce NOx in diesel engine. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Choi, Y.; Park, G.; Jang, I.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Choi, Y. Investigation on the reduction in unburned ammonia and nitrogen oxide emissions from ammonia direct injection SI engine by using SCR after-treatment system. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttignol, F.; Garbujo, A.; Biasi, P.; Kröcher, O.; Ferri, D. N2O Activation and NO Adsorption Control the Simultaneous Conversion of N2O and NO Using NH3 over Fe-ZSM-5. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 8978–8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedagiri, P.; Martin, L.J.; Varuvel, E.G. Characterization of urea SCR using Taguchi technique and computational methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 11988–11999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendrich, M.; Scheuer, A.; Hayes, R.E.; Votsmeier, M. Unified mechanistic model for Standard SCR, Fast SCR, and NO2 SCR over a copper chabazite catalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 222, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, J.D.; Votsmeier, M.; Grönbeck, H. Influence of aluminium distribution on the diffusion mechanisms and pairing of Cu(NH3)2+ complexes in Cu-CHA. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samosir, B.F.; Quach, N.Y.; Chul, O.K.; Lim, O. NOx emissions prediction in diesel engines: A deep neural network approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfaoui, J.; Ghorbel, A.; Petitto, C.; Delahay, G. New SCR Catalysts Based on Mn Supported on Simple or Mixed Aerogel Oxides: Effect of Sulfates Addition. Catal. Lett. 2024, 155, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, A.; Fidowicz, K.; Rutkowska, M.; Kowalczyk, A.; Michalik, M.; Chmielarz, L. Low-temperature NO conversion with NH3 over cerium-doped MWW derivatives activated with copper species. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 1456–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, M.; Mollá Robles, A.; Rotko, M.; Vuong, T.H.; Lei, H.; Lavrič, Ž.; Grilc, M.; Lukman, M.F.; Valiullin, R.; Bertmer, M.; et al. Unraveling the NH3-SCR-DeNOx Mechanism of Cu-SSZ-13 Variants by Spectroscopic and Transient Techniques. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202400198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE J1939; Recommended Practice for Data Communication in Heavy Duty Vehicle Networks. Society of Automotive Engineers: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018.

- DIN 70070; Road Vehicles—Diagnostic Communication with Road Vehicles—Electrical and Signal Characteristics of Diagnostic Communication. German Institute for Standardization (DIN): Berlin, Germany, 2001.

- Luo, J.B.; Xu, H.X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.H.; Tie, Y.H.; Li, M.S.; Yang, D.Y. The research on dynamic performance of single channel selective catalytic reduction system with different shapes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhong, W.; Mao, C.; Xu, Y.; Lu, K.; Ye, Y.; Guan, W.; Pan, M.; Tan, D. Multi-objective optimization of Fe-based SCR catalyst on the NOx conversion efficiency for a diesel engine based on FGRA-ANN/RF. Energy 2024, 294, 130899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhong, W.; Pan, M.; Yin, Z.; Lu, K. Multi-objective optimization of structural parameters of SCR system under Eley-Rideal reaction mechanism based on machine learning coupled with response surface methodology. Fuel Process. Technol. 2024, 265, 108141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lian, L.; Kong, D.; Zhao, Y. Recent advances in sulfur poisoning of selective catalytic reduction (SCR) denitration catalysts. Fuel 2024, 365, 131126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guan, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Chen, G.; Guo, R.; Pan, W.; Wu, J.; Li, F.; Ren, J. The impact of catalyst structure and morphology on the catalytic performance in NH3-SCR reaction: A review. Fuel 2024, 361, 130541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daya, R.; Deka, D.J.; Goswami, A.; Menon, U.; Trandal, D.; Partridge, W.P.; Joshi, S.Y. A redox model for NO oxidation, NH3 oxidation and high temperature standard SCR over Cu-SSZ-13. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 328, 122524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xie, F.; Chen, H. A temporal discretization and spatial integration SCR model with dual temperature-related parameters. Fuel 2024, 367, 131405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Sun, F.; Du, J.; Li, Y. Experimental investigation of NOx emissions and SCR optimization in hydrogen internal combustion engines under full-range operating conditions. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 123, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Kang, H.; Wang, N.; Chu, W.; Li, L. Mechanistic insights into the cobalt promotion on low-temperature NH3-SCR reactivity of Cu/SSZ-13. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 315, 123617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Shen, X.; Shen, B. A simulation study on NOx reduction efficiency in SCR catalysts utilizing a modern C3-CNN algorithm. Fuel 2024, 363, 130985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Sun, H.; Hong, Z.; He, C.; Toyao, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Chen, H. Bifunctional mechanism for low-temperature Methanol-SCR on H-FER zeolite doped by trace amount of cobalt. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2025, 696, 120201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Jia, Z.; Xu, S.; Chen, G.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, C. Influence and correlation analysis of urea injection method and mixer combination on SCR performance. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2025, 217, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Xue, J.; Su, X.; Chen, J.; Qiao, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Du, X. Selective NH3 trapping as the enabler for efficient bifunctional catalysis of NH3-SCR and CO oxidation reactions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 375, 125430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Lee, S.; Jang, J.; Na, S.; Choi, G.; Choi, M.; Park, Y. Performance optimization of static mixer in urea-SCR system considering flow and turbulence characteristics. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, X.; Li, Z.; Tao, Y.; Xue, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ran, J.; Rac, V.; Rakić, V. Electrothermal alloy embedded V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalyst for NH3-SCR with promising wide operating temperature window. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 159, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Qian, Y.; Gong, Z.; Meng, S.; Wei, X.; Ma, B. The impact of energy flow on catalytic behavior in advanced DOC+SCR emission control systems. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 143, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Li, Z. Optimal Design and Experimental Study of Tightly Coupled SCR Mixers for Diesel Engines. Energy Eng. 2024, 121, 2893–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, T.Y. Reconstruction of flow and temperature fields of exhaust gas flow for enhancing the energy harvesting performance of a thermoelectric generator. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, J.; Lv, J.; Xu, W.; Tan, D.; Jiang, F.; Huang, H. Investigation on the effects of non-uniform porosity catalyst on SCR characteristic based on the field synergy analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Shi, W.; Jing, J.; Dong, Z.; Yuan, J.; Qu, L. An artificial intelligence strategy for multi-objective optimization of Urea-SCR for vehicle diesel engine by RSM-VIKOR. Energy 2025, 317, 134667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Engine type | Six-cylinder, four-stroke, direct-injection, water-cooled, electronically controlled diesel engine | – |

| Bore/stroke | 113 × 140 | mm |

| Compression ratio | 17.5: 1 | – |

| Displacement | 8.4 | L |

| Rated power | 206 | kW |

| Rated speed | 2200 | r·min−1 |

| Maximum torque | 1100 | N·m |

| Subsystem | Parameter | Setpoint/Limit | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intake system | Pressure drop | ≤4 (calibration point) | kPa |

| Intercooler pressure loss | ≤11 (calibration point) | kPa | |

| Charge-air temperature after intercooler | 49 ± 2 (calibration point) | °C | |

| Cooling system | Jacket water temperature | 88 ± 5 | °C |

| Fuel system | Fuel temperature | 37 ± 2 | °C |

| Fuel type | Diesel, sulfur ≤ 50 | ppm | |

| Exhaust system | Exhaust back pressure | ≤16 (calibration point) | kPa |

| Maximum exhaust temperature | ≤650 | °C |

| Measured Item | Instrument/Model | Manufacturer | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine power | Control test bench | AVL (Graz, Austria) | 10–2500 kW | – |

| Fuel consumption | Fuel consumption meter | AVL | 0.5–500 L/h | ±0.05 L/h |

| Smoke opacity | Filter paper smoke meter | AVL | 0–10 FSN | ±0.05 FSN |

| Intake air mass flow | Air flow meter | ABB (Zurich, Switzerland) | 0–200 kg/min | ±0.1 kg/min |

| Gas temperature | Temperature sensor | AVL | 0–1000 °C | ±1 °C |

| Exhaust gas concentration | Gas analyzer | Continental (Hanover, Germany) | 0–5000 ppm | ±10 ppm |

| Parameters | Abbreviation | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier diameter | Cd | 320 | mm |

| Carrier length | Cl | 600 | mm |

| Side pipe length | Pl | 60 | mm |

| Catalytic pore density | CPSI | 400 | 1/in2 |

| Borehole width | Bw | 1.2 | mm |

| Wall thickness | Wt | 0.165 | mm |

| Washcoat thickness | Wct | 0.0165 | mm |

| Reaction Type | Reaction Equation | Reaction Model |

|---|---|---|

| NH3 adsorption | R1: NH3 + S → NH3(S) | |

| NH3 desorption | R2: NH3(S) → NH3 + S | |

| Standard SCR reaction | R3: 4NH3 + 4NO + O2 → 4N2 + 6H2O | |

| R4: 4NH3(S) + 4NO + O2 → 4N2 + 6H2O | ||

| Fast SCR reaction | R5: 4NH3 + 2NO + 2NO2 → 4N2 + 6H2O | |

| R6: 4NH3(S) + 2NO + 2NO2 → 4N2 + 6H2O | ||

| NO2-SCR reaction | R7: 8NH3 + 6NO2 → 7N2 + 12H2O | |

| R8: 8NH3(S) + 6NO2 → 7N2 + 12H2O |

| Parameters | 25% Load | 50% Load | 75% Load | 100% Load |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOx concentration (ppm) | 1218 | 1131 | 1054 | 1124 |

| O2 concentration (%) | 16.16 | 15.06 | 14.56 | 13.69 |

| CO2 concentration (%) | 3.60 | 4.38 | 4.75 | 5.37 |

| H2O concentration (%) | 3.13 | 3.12 | 3.11 | 3.11 |

| Velocity inlet (m/s) | 11.50 | 20.51 | 27.84 | 36.05 |

| Exhaust flow (kg/s) | 0.63 | 1.12 | 1.52 | 1.97 |

| Exhaust temperature (°C) | 225 | 320 | 350 | 400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nian, M.; Liao, J.; Zhong, W.; Zheng, L.; Luo, S.; Zhang, H. Investigation on Multi-Load Reaction Characteristics and Field Synergy of a Diesel Engine SCR System Based on an Eley-Rideal and Langmuir-Hinshelwood Dual-Mechanism Coupled Model. Energies 2025, 18, 6571. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246571

Nian M, Liao J, Zhong W, Zheng L, Luo S, Zhang H. Investigation on Multi-Load Reaction Characteristics and Field Synergy of a Diesel Engine SCR System Based on an Eley-Rideal and Langmuir-Hinshelwood Dual-Mechanism Coupled Model. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6571. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246571

Chicago/Turabian StyleNian, Muxin, Jingyang Liao, Weihuang Zhong, Linfeng Zheng, Shengfeng Luo, and Haichuan Zhang. 2025. "Investigation on Multi-Load Reaction Characteristics and Field Synergy of a Diesel Engine SCR System Based on an Eley-Rideal and Langmuir-Hinshelwood Dual-Mechanism Coupled Model" Energies 18, no. 24: 6571. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246571

APA StyleNian, M., Liao, J., Zhong, W., Zheng, L., Luo, S., & Zhang, H. (2025). Investigation on Multi-Load Reaction Characteristics and Field Synergy of a Diesel Engine SCR System Based on an Eley-Rideal and Langmuir-Hinshelwood Dual-Mechanism Coupled Model. Energies, 18(24), 6571. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246571