Effects of Localized Overheating on the Particle Size Distribution and Morphology of Impurities in Transformer Oil

Abstract

1. Introduction

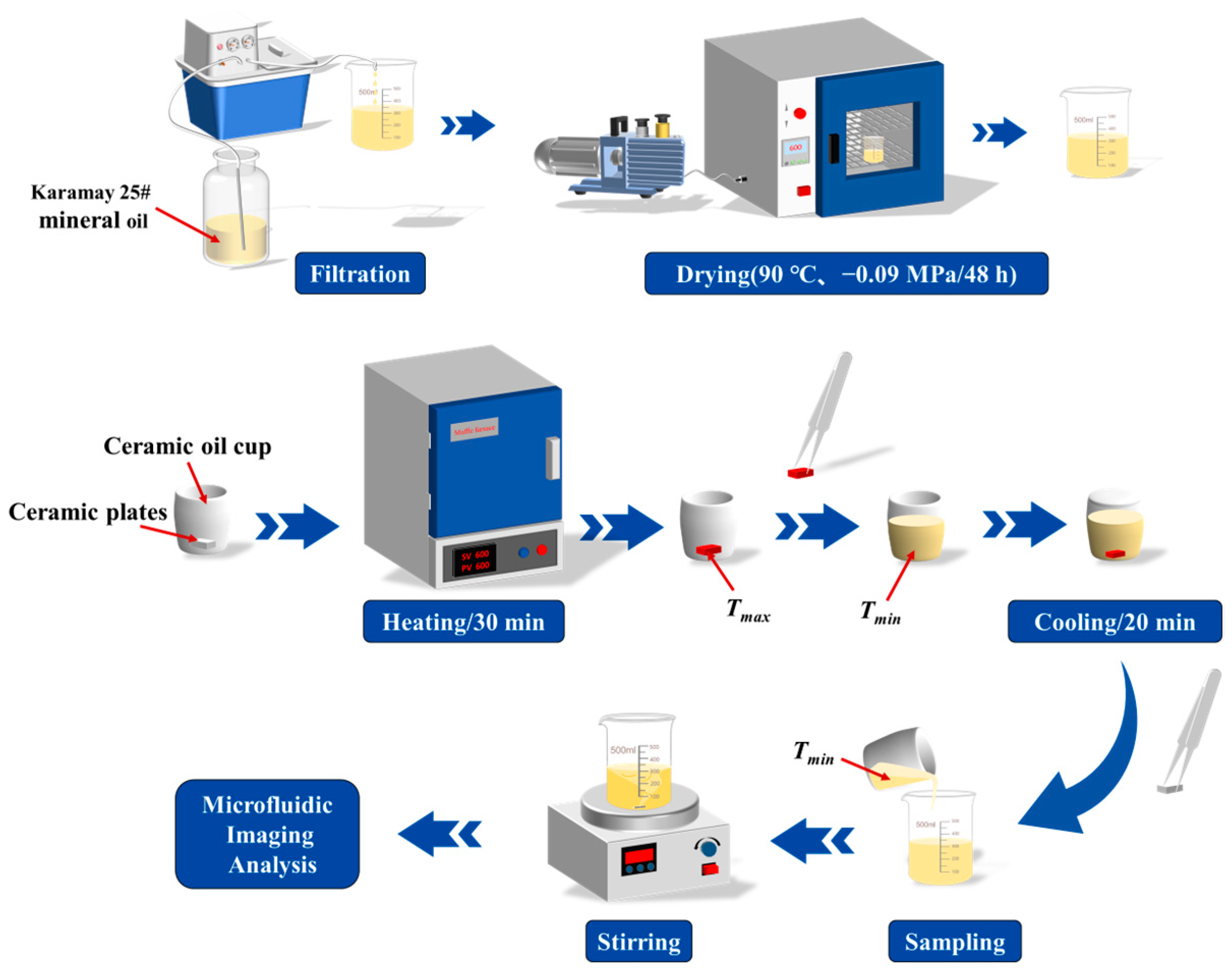

2. Localized Overheating Experiment of Insulating Oil and Impurity Particle Detection

2.1. Localized Overheating Experiment of Insulating Oil

2.2. Impurity Particle Testing and Characteristic Parameter Extraction in Oil

3. Analysis of Characteristic Parameters of Impurity Particles in Insulating Oil

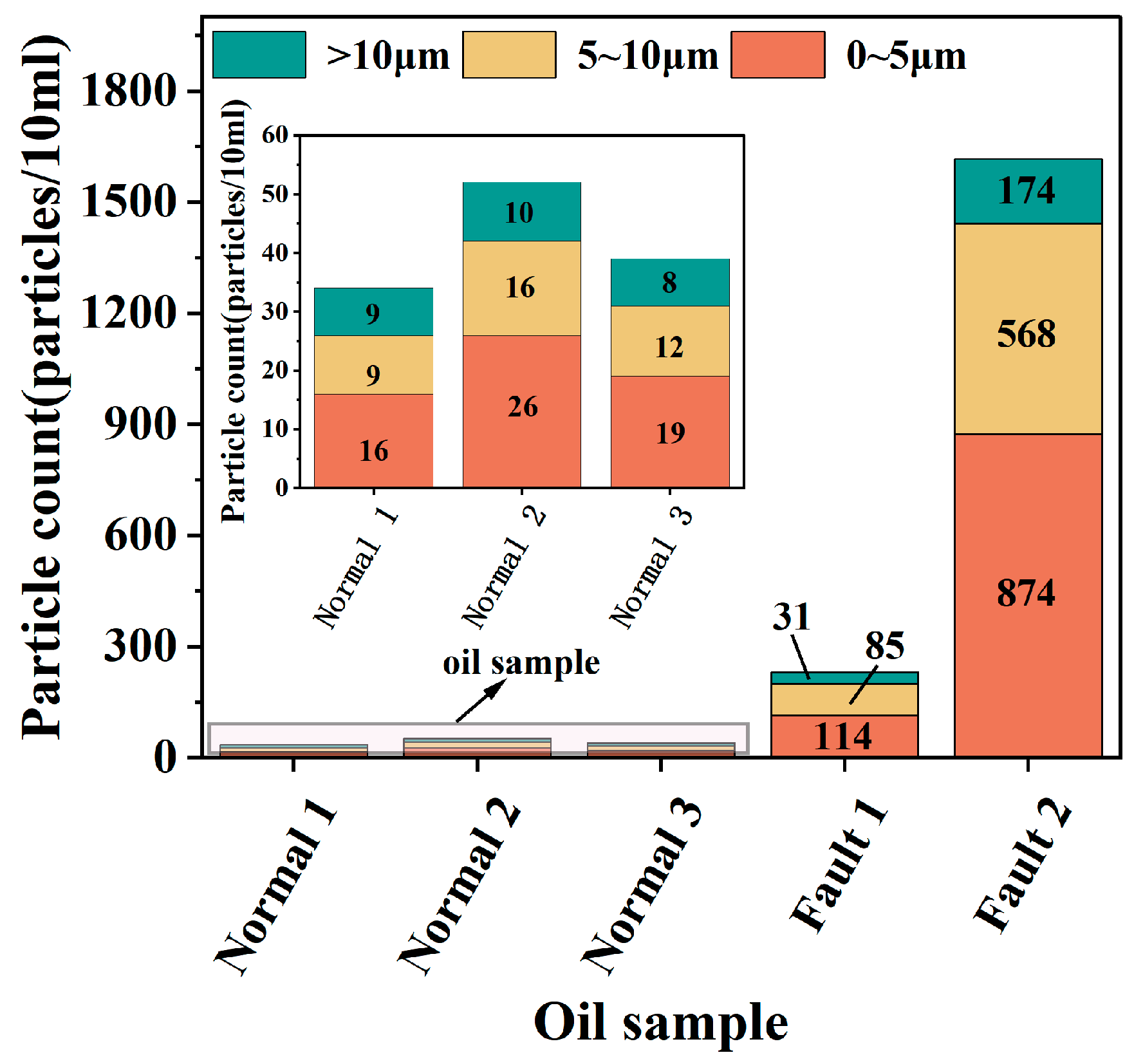

3.1. Number of Particles

3.2. Particle Size Distribution

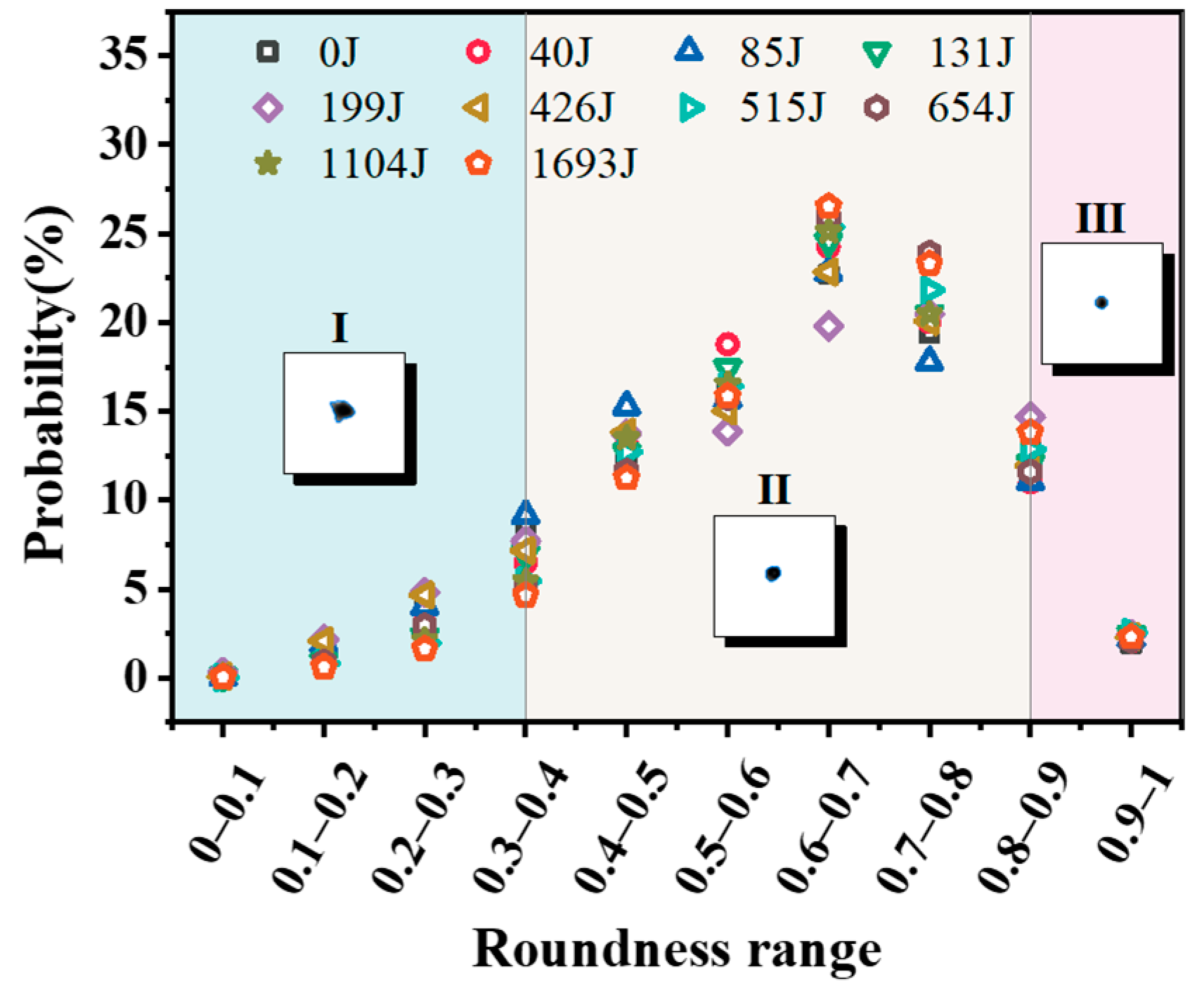

3.3. Particle Shape

4. Field Oil Sample Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivanov, G.; Spasova, A.; Mateev, V.; Marinova, I. Applied Complex Diagnostics and Monitoring of Special Power Transformers. Energies 2023, 16, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Chen, S.; Lu, B.; Huang, Y. Study on transformer fault diagnosis based on improved deep residual shrinkage network and optimized residual variational autoencoder. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Cui, Y.; Long, J.; Ren, F.; Ji, S.; Wang, S. An Experimental Study of the Sweep Frequency Impedance Method on the Winding Deformation of an Onsite Power Transformer. Energies 2020, 13, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Sheng, G.; Yan, Y.; Dai, J.; Jiang, X. Prediction of Dissolved Gas Concentrations in Transformer Oil Based on the KPCA-FFOA-GRNN Model. Energies 2018, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P. Box-plot-SA-BP: Fault Diagnostic Model for Multi-feature Transformer DGA. Power Syst. Big Data 2023, 26, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P. Application of probabilistic neural network with fruit fly optimization algorithm in power transformer fault diagnosis. Power Syst. Big Data 2018, 21, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60422:2013; Mineral Insulating Oils in Electrical Equipment–Supervision and Maintenance Guidance. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 4406:2021; Hydraulic Fluid Power—Fluids Method for Coding the Level of Contamination by Solid Particles. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Feng, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhao, X.; Yang, L. Research on Generation Mechanism of Carbon Particles in Natural Ester and Mineral Oil and Their Impact on Electrical Properties. High Volt. Appar. 2025, 61, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Chen, G.; Yan, X.; Hao, J.; Liao, R. Molecular pyrolysis process and gas production characteristics of 3-element mixed insulation oil under thermal fault. High Volt. 2022, 7, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, J.; Xue, Z.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Z.; Fang, J. Adhesion characteristics of carbon particles on the surface of epoxy resin in insulating oil under DC electric field and influencing factors. High Volt. 2025, 10, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Feng, H.; Fang, Y.; Chen, W.; Han, K. Formation and diffusion characteristics of carbon black in insulating oil under multiple breakdown. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd China International Youth Conference on Electrical Engineering (CIYCEE), Chengdu, China, 15–17 December 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 60599:2007; Mineral Oil-Filled Electrical Equipment In Service—Guidance on the Interpretation of Dissolved and Free Gases Analysis. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Gong, P.; Wang, Z. Causes, types and influencing factors of coke formation in petroleum processing. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2016, 35, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchie, M.; Kozako, M.; Hikita, M.; Sasaki, E. Modeling of early stage partial discharge and overheating degradation of paper-oil insulation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2014, 21, 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60076-2; Power Transformers–Part 2: Temperature Rise for Liquid-Immersed Transformers. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Sharma, D.K.; King, D.; Oma, P.; Merchant, C. Micro-flow imaging: Flow microscopy applied to sub-visible particulate analysis in protein formulations. AAPS J. 2010, 12, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strehl, R.; Rombach-Riegraf, V.; Diez, M.; Egodage, K.; Bluemel, M.; Jeschke, M.; Koulov, A.V. Discrimination between silicone oil droplets and protein aggregates in biopharmaceuticals: A novel multiparametric image filter for sub-visible particles in microflow imaging analysis. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liaw, A.; Chen, Y.M.; Su, Y.; Skomski, D. Convolutional neural networks enable highly accurate and automated subvisible particulate classification of biopharmaceuticals. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11500:2022; Hydraulic Fluid Power—Determination of the Particulate Contamination Level of a Liquid Sample by Light Obscuration Counting Using the Light-Extinction Principle. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, X.; Dong, Z.; Zhong, J.; Wang, X. Study on the generation of carbon particles in oil and its effect on the breakdown characteristics of oil-paper insulation. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2023, 18, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9276-6:2008; Representation of results of particle size analysis—Part 6: Descriptive and quantitative representation of particle shape and morphology. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Bullard, J.W.; Garboczi, E.J. Defining shape measures for 3D star-shaped particles: Sphericity, roundness, and dimensions. Powder Technol. 2013, 249, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Song, S.; Shi, Q. Non-equilibrium thermodynamic analysis of quasi-static granular flows. Acta Phys. Sin. 2014, 63, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, C. Some theorems on the free energies of crystal surfaces. Phys. Rev. 1951, 82, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Wang, K.; Yang, L.; Liao, R. Study on the testing method of carbon particles in insulating oil based on microflow imaging. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Karamay 25# | Parameter | Karamay 25# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pour point/°C | −45 | Dielectric loss factor (90 °C) | 0.005 |

| Kinematic viscosity (40 °C)/(mm2/s) | ≤12 | Breakdown voltage (kV/mm) | ≥28 |

| Density (20 °C)/(kg/m2) | 895 | Flash point/°C | 135 |

| Temperature/°C | Mass/g | Heat/J |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 0.265 | 13 |

| 1.325 | 63 | |

| 3.445 | 162 | |

| 100 | 0.265 | 17 |

| 1.325 | 85 | |

| 3.445 | 221 | |

| 140 | 0.265 | 26 |

| 1.325 | 131 | |

| 3.445 | 339 | |

| 200 | 0.265 | 40 |

| 1.325 | 199 | |

| 3.445 | 515 | |

| 400 | 0.265 | 85 |

| 1.325 | 426 | |

| 3.445 | 1104 | |

| 800 | 0.265 | 131 |

| 1.325 | 654 | |

| 3.445 | 1693 |

| Temperature/°C | Heat/J | Number (Particles/10 mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 13 | 161 |

| 63 | 165 | |

| 162 | 163 | |

| 100 | 17 | 162 |

| 85 | 158 | |

| 221 | 165 | |

| 140 | 26 | 212 |

| 131 | 254 | |

| 339 | 309 | |

| 200 | 40 | 269 |

| 199 | 533 | |

| 515 | 866 | |

| 400 | 85 | 374 |

| 426 | 741 | |

| 1104 | 1802 | |

| 800 | 131 | 441 |

| 654 | 988 | |

| 1693 | 2997 |

| Model Parameters | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t-Test Results | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 146.732 | / | 1.686 | 0.136 |

| Tmax | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.057 | 0.956 |

| Qoil | 1.578 | 0.991 | 17.038 | <0.01 |

| R2 | 0.978 | |||

| Serial Number | Voltage Level | Model | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal 1 | 110 kV | SZ11-63000/110 | Normal operation |

| Normal 2 | 220 kV | SFPSZ10-180000/220 | Normal operation |

| Normal 3 | 500 kV | ODFS20-334000/500 | Normal operation |

| Fault 1 | 1000 kV | BKDF-240000/1000 | Low temperature overheating |

| Fault 2 | 500 kV | EFPH 8557 | High temperature overheating |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, S.; Liao, R.; Yang, L.; Chen, C.; Yu, X. Effects of Localized Overheating on the Particle Size Distribution and Morphology of Impurities in Transformer Oil. Energies 2025, 18, 6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246566

Feng S, Liao R, Yang L, Chen C, Yu X. Effects of Localized Overheating on the Particle Size Distribution and Morphology of Impurities in Transformer Oil. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246566

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Shangquan, Ruijin Liao, Lijun Yang, Chen Chen, and Xinxi Yu. 2025. "Effects of Localized Overheating on the Particle Size Distribution and Morphology of Impurities in Transformer Oil" Energies 18, no. 24: 6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246566

APA StyleFeng, S., Liao, R., Yang, L., Chen, C., & Yu, X. (2025). Effects of Localized Overheating on the Particle Size Distribution and Morphology of Impurities in Transformer Oil. Energies, 18(24), 6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246566