The increasing penetration of renewable energy sources in electric power systems has posed significant operational challenges, particularly with respect to frequency stability. Technologies such as wind and photovoltaic generation do not provide synchronous inertia to the system, leading to a reduction in effective inertia and, consequently, an increase in the rate of change of frequency (RoCoF) during disturbances. This decline in the system’s ability to withstand frequency variations compromises the security and reliability of power supply, especially in systems with a high share of renewable generation and low inertia.

In this context, battery energy storage systems (BESS) employing inertia emulation strategies have emerged as a viable solution to mitigate the adverse effects of reduced inertia. Through appropriate control of their frequency response, BESS can provide immediate dynamic support, stabilizing frequency in the initial moments following a disturbance and reducing the RoCoF. However, to maximize their technical and economic effectiveness, it is essential to determine their optimal placement and sizing within the power system.

This article addresses the issue of optimal placement and sizing of BESS with inertia emulation to enhance frequency stability in low-inertia power systems. A methodology is proposed based on (specify the specific method, e.g., metaheuristic algorithms, mathematical programming, modal analysis, etc.), which enables the determination of the optimal location and capacity of BESS, considering both technical and economic criteria. Through simulations on a representative test system, the impact of the placement and sizing strategy on frequency stability is evaluated, providing guidelines for the efficient integration of BESS into grids with high penetration of renewable generation.

1.1. Related Works

The integration of BESS into modern power grids has been the focus of numerous studies proposing innovative control strategies and optimization methods to enhance system performance and stability. In ref. [

1], a control strategy combining adaptive droop control with an adaptive state of charge (SoC) recovery mechanism for primary frequency regulation (PFR) was presented, improving frequency stability and reducing mechanical stress on conventional generating units. In ref. [

2], a hierarchical control scheme was introduced, integrating BESS SoC into frequency regulation through a multilevel strategy, with its effectiveness validated using Hardware-in-the-Loop testing. In ref. [

3], a secondary frequency control strategy based on the degree of participation of BESS was proposed, utilizing a fuzzy logic inference system and a quadratic programming algorithm to optimize task allocation. In ref. [

4], a load frequency control (LFC) strategy was presented, incorporating detailed dynamic models of wind turbines, HVDC systems, BESS, and synchronous generators, demonstrating significant improvements in frequency stability. In ref. [

5], a control strategy for hybrid energy storage systems was developed, integrating BESS and pumped hydro energy storage to enhance PFR in grids with high renewable penetration. Finally, in ref. [

6], the role of BESS in providing additional inertial support in grids with high renewable energy penetration was investigated, emphasizing the importance of optimal BESS sizing to balance costs and stability benefits. These studies underscore the fundamental role of BESS in improving frequency regulation and the stability of modern power grids, especially in contexts of high renewable energy penetration.

The integration of BESS in microgrids and isolated systems has been extensively studied, with various control strategies proposed to enhance frequency regulation and system stability. In ref. [

7], a control strategy was presented that integrates SoC management with load frequency control in isolated microgrids, using a shifted droop control mechanism that dynamically adjusts BESS operation based on five distinct SoC scenarios, thereby improving system stability and SoC management. In ref. [

8], a frequency control strategy for isolated greenhouses was proposed, integrating BESS and Light-Emitting Diode lighting loads, using a two-stage control that combines the fast response of BESS and Light-Emitting Diode lighting loads with frequency restoration via diesel generators. In ref. [

9], a multifunctional adaptive control strategy was introduced for energy management and voltage-frequency regulation in isolated microgrids composed of photovoltaic (PV) units, BESS, and hybrid PV/BESS units, integrating decentralized and distributed control for optimal performance. In ref. [

10], an integrated multifunctional control scheme was presented for stand-alone BESS in synchronous generator-based microgrids, highlighting the use of a state of charge-based adaptive high-pass filter for frequency regulation and unbalanced load compensation. In ref. [

11], a reserve-based frequency support strategy for BESS in isolated residential microgrids was proposed, introducing a reserve control layer within the conventional LFC architecture to improve frequency stability during emergency conditions. Finally, in ref. [

12], a control framework for voltage and frequency regulation in weak grids with wind turbines, PV, and BESS was presented, utilizing a fixed-time containment control strategy that enables BESS to simultaneously regulate voltage and frequency while maintaining SoC balance. These studies highlight the importance of advanced and adaptive control strategies for the effective integration of BESS in microgrids and isolated systems, enhancing system stability and efficiency.

The integration of BESS with renewable energy sources has been extensively studied to enhance frequency stability in low-inertia systems. In ref. [

13], a methodology was proposed to mitigate over-frequency events through optimal BESS allocation in wind-dominated systems, using a Particle Swarm Optimization-based model. In ref. [

14], the role of BESS in improving frequency response in low-inertia, solar-dominated systems was investigated, integrating inertia response and PFR strategies within the traditional LFC framework. In ref. [

15], a virtual inertia control approach was presented, incorporating a coordinated SoC recovery mechanism with secondary frequency control of generators, optimizing battery utilization and reducing BESS energy consumption by 36%. In ref. [

16], the use of energy storage systems, including superconducting magnetic energy storage and BESS, was explored to improve frequency response in wind-dominated grids, demonstrating that the combination of superconducting magnetic energy storage and BESS reduced system costs by 76.9% compared to BESS-only solutions. In ref. [

17], a strategy for optimal BESS sizing and placement in high wind penetration systems was proposed, integrating model predictive control (MPC) for coordinated frequency and voltage regulation. In ref. [

18], a coordinated control strategy between variable-speed wind turbines and BESS was investigated to enhance fast frequency response, using a SoC-based adaptive droop control. In ref. [

19], a control strategy was presented to mitigate torsional vibrations in doubly-fed induction generators using a BESS-based damper, improving torsional damping and maintaining frequency stability. In ref. [

20], a model predictive control MPC-based strategy was developed to enable a hybrid wind farm and BESS unit to provide fast frequency regulation, validated through Hardware-in-the-Loop simulations. Finally, ref. [

21] presents a coordinated control strategy for a voltage-source-converter-based high-voltage direct current-connected wind farms with a BESS for providing frequency support.

The optimization of BESS for participation in energy markets and grid stability has been widely explored in various studies. In ref. [

22], the economic viability of residential PV-BESS installations was evaluated, highlighting the importance of storage sizing and self-consumption for profitability, particularly in systems with a capacity factor ≥ 18%. In ref. [

23], a revenue stacking model was proposed that combines fast frequency regulation with participation in the Italian balancing market, enhancing efficiency and investment returns by 13%. In ref. [

24], the financial viability of BESS in households with dynamic electricity contracts in the Netherlands was analyzed, concluding that the gradual phase-out of net metering negatively affects BESS profitability. In ref. [

25], a reinforcement learning framework was presented for adaptive BESS scheduling in dynamic markets, demonstrating greater profitability and resilience to price fluctuations compared to traditional methods. In ref. [

26], a probabilistic forecasting framework for BESS SoC under primary frequency control was developed, employing multi-attention recurrent neural networks to enhance prediction accuracy and reliability. In ref. [

27], a setpoint frequency control method was introduced to integrate renewable energy sources, optimizing BESS operation and reducing grid balancing costs. These studies underscore the crucial role of BESS in improving profitability, grid stability, and the efficient integration of renewable energy into energy markets.

Control strategies for BESS have been essential in improving the stability of power systems. In ref. [

28], a real-time optimal control method was presented that enables the simultaneous provision of primary frequency control and local voltage regulation by dynamically adjusting active and reactive power setpoints, with its effectiveness validated on a utility-scale BESS at EPFL, Lausanne. In ref. [

29], a self-adaptive control strategy was proposed that classifies disturbances into step and small continuous types, introducing two models to prevent frequency degradation and ensure SoC recovery, demonstrating improvements in frequency stability and long-term economic operation. Meanwhile, ref. [

30] developed a contingency reserve assessment framework for fast frequency response across multiple large-scale BESS, using genetic algorithms to optimize reserves and enhance grid resilience under high renewable penetration. As for ref. [

31], a methodology was presented to determine the required BESS capacity in the Korean power system to compensate for reduced inertia under high renewable penetration scenarios, highlighting the effectiveness of BESS in frequency control. In ref. [

32], a rule-based programming algorithm was introduced for BESS management in prosumers, optimizing energy flows with lower computational costs and demonstrating scalability for renewable energy communities.

The integration of BESS into grid infrastructures and industrial energy systems has proven essential for enhancing stability and energy efficiency. In ref. [

33], the use of BESS to mitigate transmission congestion in the Brazilian Interconnected System was analyzed, highlighting its potential to improve grid flexibility, albeit with challenges related to high comparative costs. Meanwhile, ref. [

34] explored the application of BESS in the Puducherry Smart Grid to reduce demand peaks through a Model Predictive Control strategy, achieving a 20% reduction in peak demand and improvements in voltage stability. In ref. [

35], an integrated industrial power supply system was developed, combining renewable sources, carbon capture and storage, and BESS, resulting in a 59.78% reduction in carbon emissions and emphasizing the need for policy incentives to ensure economic feasibility. Finally, ref. [

36] proposed an optimization model for BESS sizing in microgrids, employing mixed-integer linear programming and Benders decomposition, ensuring frequency stability by integrating transient dynamics into the model. These studies underscore the importance of BESS in improving energy infrastructure, integrating renewable energy, and supporting industrial sustainability.

Other control and optimization strategies for BESS have been proposed to improve frequency stability and economic viability in modern power systems. In ref. [

37], a shared-use leasing strategy for distributed BESS in joint energy and frequency control ancillary services markets was proposed, demonstrating economic benefits for both owners and users. In ref. [

38], an optimal configuration method with opportunity constraints for BESS in networks with high integration of variable renewable energy was developed, enhancing both frequency stability and economic feasibility. In ref. [

39], a Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop simulation approach was introduced to evaluate the fast frequency response of BESS, employing an advanced frequency detection algorithm that improves accuracy and robustness. In ref. [

40], the effectiveness of BESS in improving frequency stability in islanded networks with high renewable penetration was investigated using Particle Swarm Optimization to tune control parameters. In ref. [

41], a risk-preference-based optimization model for user-side BESS configuration was presented, balancing economic viability and operational stability. In ref. [

42], a methodology for optimal placement of frequency regulation energy storage systems was introduced, enhancing frequency recovery in modern networks. In ref. [

43], an optimization approach for BESS placement and sizing was developed using metaheuristic algorithms such as PSO, Firefly Algorithm, and Bat Algorithm, showing improvements in frequency stability. In ref. [

44], a control strategy for grid-following and grid-forming inverters in microgrids integrated with solar energy and BESS was presented, improving grid stability and frequency response. Lastly, ref. [

45] proposed a mixed-integer linear programming model to optimize the sizing of renewable energy communities, enhancing energy self-management and sustainability. These studies underscore the importance of BESS integration for frequency stability, economic viability, and sustainable energy management in modern power grids.

The article ref. [

46] proposes a novel optimization algorithm called the Binary Random Dynamic Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm to determine the optimal location and sizing of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in power distribution networks. The study’s main contribution lies in enhancing the existing Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm by integrating a Binary Search Algorithm and a Random High-Speed Jumping strategy to improve both exploration and exploitation capabilities. This hybridization allows for faster convergence and avoidance of local optima. The method was tested on the IEEE 33-bus network, minimizing a multi-objective function that includes active power losses, total harmonic distortion, and voltage deviation. Results demonstrated that Binary Random Dynamic Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm achieves 2–4% lower line losses and shorter computation time compared to traditional metaheuristics like PSO, HHO, and standard Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm, showing its superior efficiency, robustness, and accuracy for EVCS placement and planning.

Energy Storage Systems are presented as a key solution to mitigate the intermittency of renewable energies and strengthen grid resilience. Among their technologies, batteries stand out by providing emergency backup, black-start capability, and regulation services. Various studies show that ESS balance supply and demand, enable response to extreme events (heat waves, floods, typhoons), and ensure continuity of critical demand, albeit at additional costs. Despite their high initial investment, ESS provide multiple benefits: energy backup, load leveling, improvement of supply quality and reliability, reduced vulnerabilities, and support for the transition toward more efficient and productive decentralized grids [

47].

The article [

48] analyzes the operation of the Chinese electricity market under a dual scheme, where regulated and deregulated transactions coexist under high wind energy penetration. Its main contribution lies in defining and classifying the so-called “unbalanced funds,” proposing detailed calculation formulas that cover cases of congestion, mismatches between generation and consumption, low-voltage users, purchasing agents, and, in particular, those arising from the coexistence of regulated and deregulated markets. To this end, it develops a market clearing model based on DC power flow with security, ramping, and contract constraints, validated through simulations on the IEEE-39 bus system using real data from a Chinese province. The results show that high wind participation amplifies unbalanced funds due to renewable dispatch priority and its mismatch with demand curves, leading to financial and equity distortions in the market. In this context, although this study does not directly address storage systems, its conclusions are highly relevant to BESS, as these can mitigate imbalances caused by wind intermittency by storing surpluses and releasing them during deficit periods, thereby helping to reduce unbalanced funds, improve the match between generation and demand, and strengthen the stability and reliability of the electricity market.

1.2. Main Contributions

Previous studies have extensively examined BESS technologies, their interaction with power systems, and their role in providing ancillary services. However, a significant knowledge gap remains: no prior work has assessed, in an integrated manner, how the location and sizing of RoCoF-based inertia-emulating BESS influence the overall frequency dynamics of the system, particularly when jointly considering critical metrics such as Nadir, Zenith, RoCoF, and steady-state frequency. Existing contributions typically address synthetic inertia control, BESS optimization, or frequency performance indicators in isolation; yet, there is no methodological framework that simultaneously incorporates inertia emulation, multi-metric frequency assessment, and the optimal spatial and capacity allocation of BESS within the grid. Accordingly, the contributions of this work are as follows:

A BESS model that emulates inertia based on the system’s RoCoF is implemented, with the aim of evaluating its impact on key frequency metrics.

The impact of BESS placement and sizing on the dynamic behavior of frequency is assessed, jointly considering the metrics of Nadir, Zenith, steady-state frequency, and RoCoF.

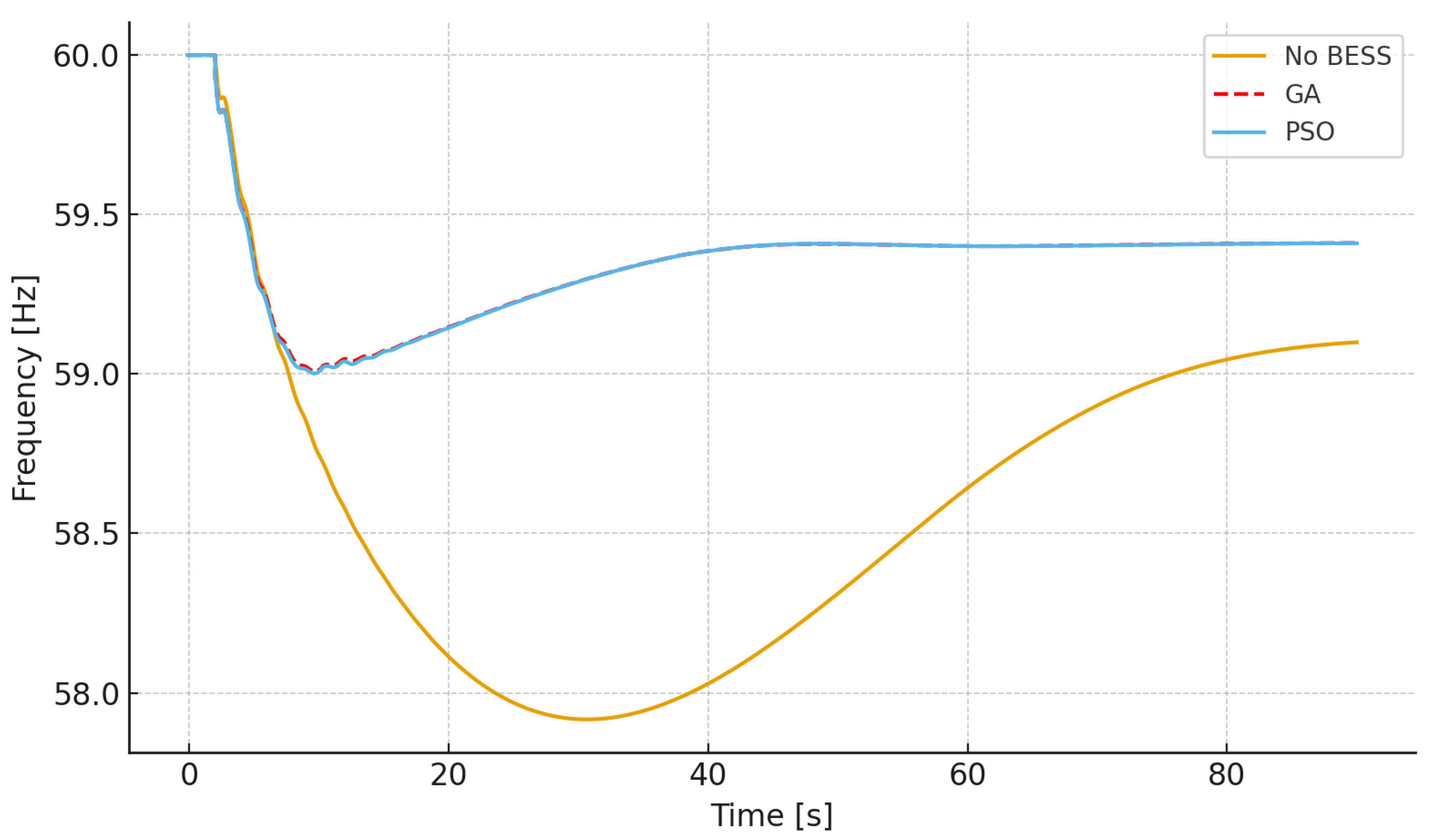

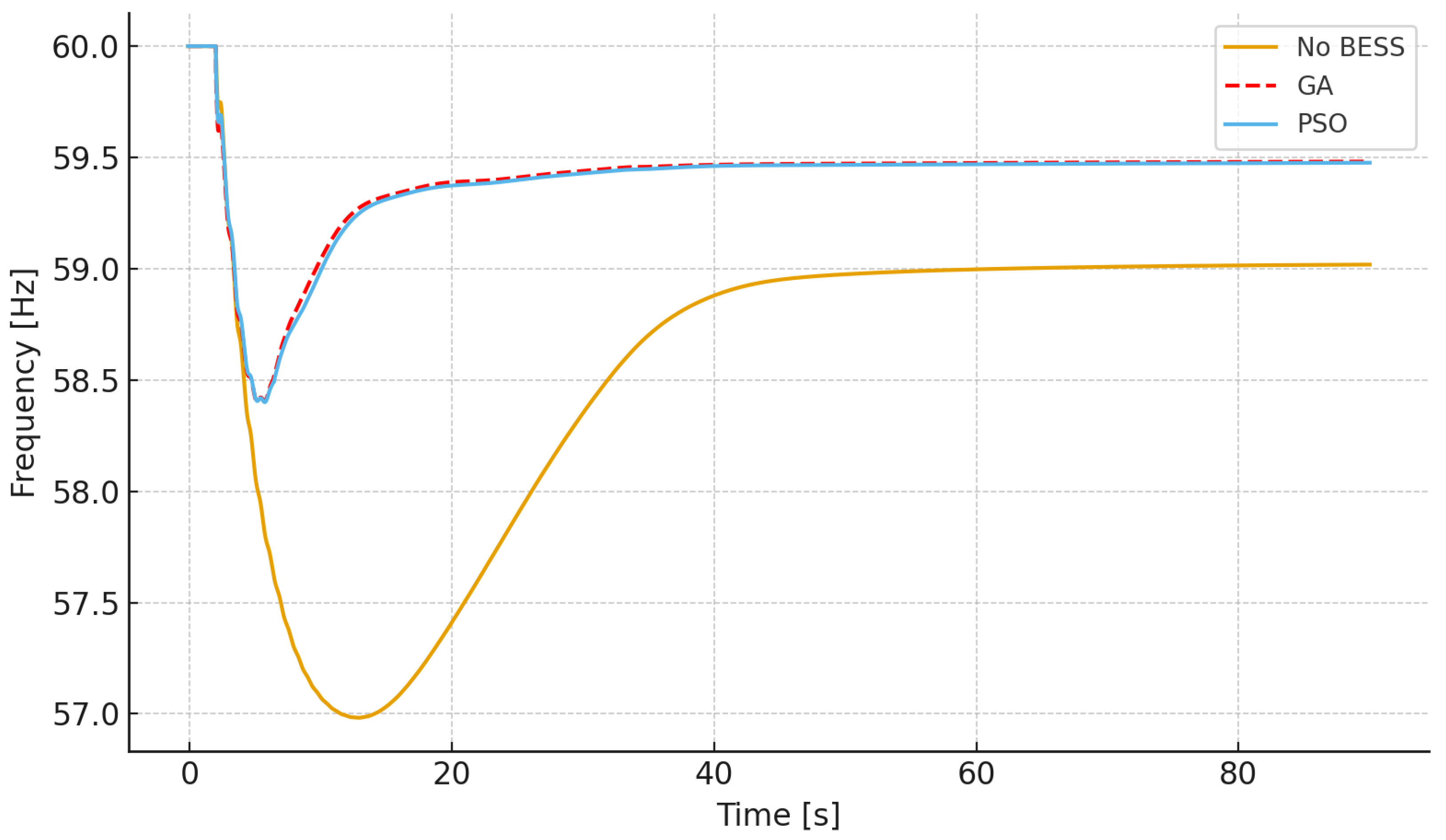

Two heuristic optimization techniques—Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithm (GA)—are implemented and compared to determine the optimal placement and sizing of RoCoF-based inertia-emulating BESS within the power grid.

This article presents an original approach that differs from comparable methods through the simultaneous integration of inertia modeling based on the RoCoF and the joint optimization of BESS placement and sizing using PSO and GA.

Traditional BESS sizing methods, such as those based on mixed-integer linear programming [

36], MPC [

34], or hierarchical predictive control strategies [

17], primarily address frequency regulation from a control or energy management perspective, without explicitly considering synthetic inertia response derived from the frequency derivative. Other metaheuristic approaches, such as PSO, the Firefly Algorithm [

43], or the Bat Algorithm [

43], have focused mainly on optimizing power or location parameters, without incorporating combined dynamic metrics such as Nadir, Zenith, RoCoF, and steady-state frequency.

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of selected studies that address optimal siting and sizing of BESS for frequency stability enhancement. It highlights the strategies used (e.g., metaheuristics, predictive control, mixed-integer linear programming, their application contexts (such as low-inertia systems, high renewable penetration, and microgrids), and the main contributions regarding frequency metrics like RoCoF, Nadir, and steady-state frequency. The proposed article is included for reference, emphasizing its novel approach to jointly optimizing BESS placement and capacity while emulating synthetic inertia based on RoCoF.

This work is organized as follows:

Section 1.3 presents fundamental concepts related to the need for virtual inertia in power systems and analyzes the impact of decreasing system inertia.

Section 1.4 reviews different approaches to inertia in power systems, including strategies for virtual inertia implementation. In

Section 1.5, the implemented model for the BESS system is described, along with the control loop designed for inertia emulation.

Section 2 details the methodology employed in the study.

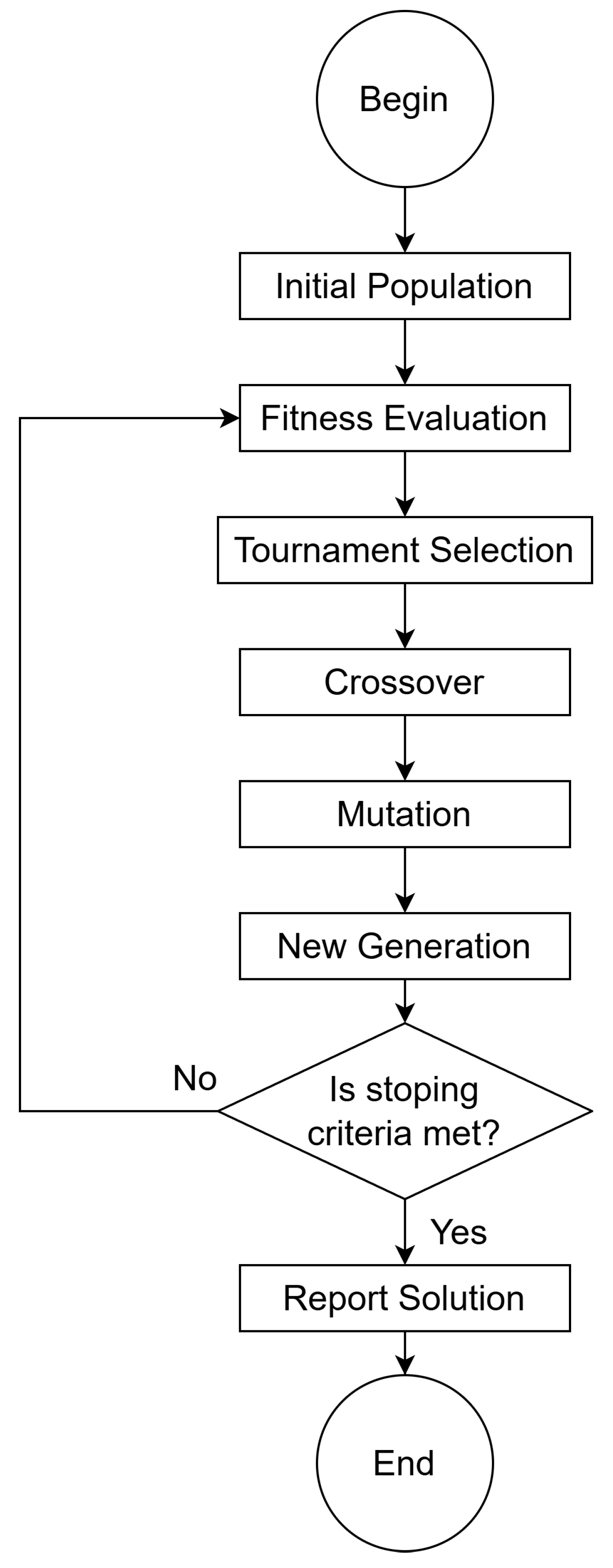

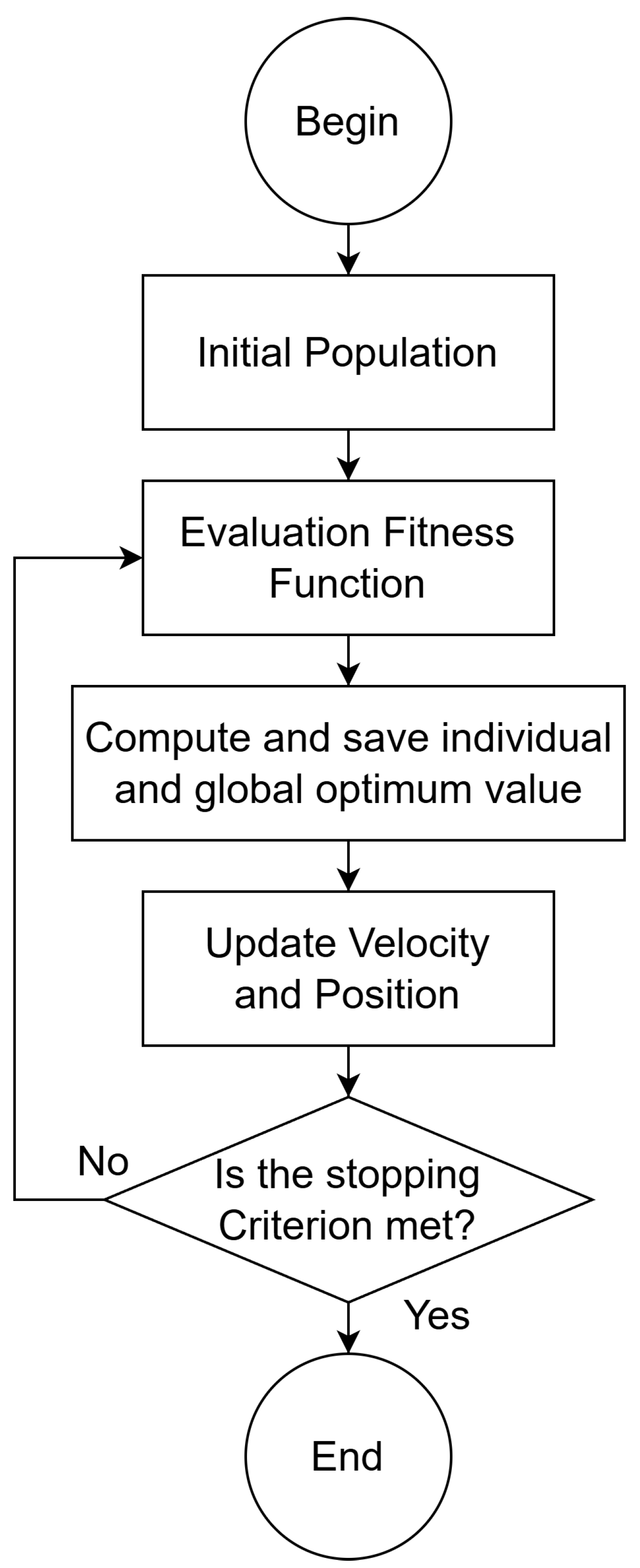

Section 3 explains the optimal placement and sizing of the BESS within the power system, highlighting the implementation of GA and PSO techniques.

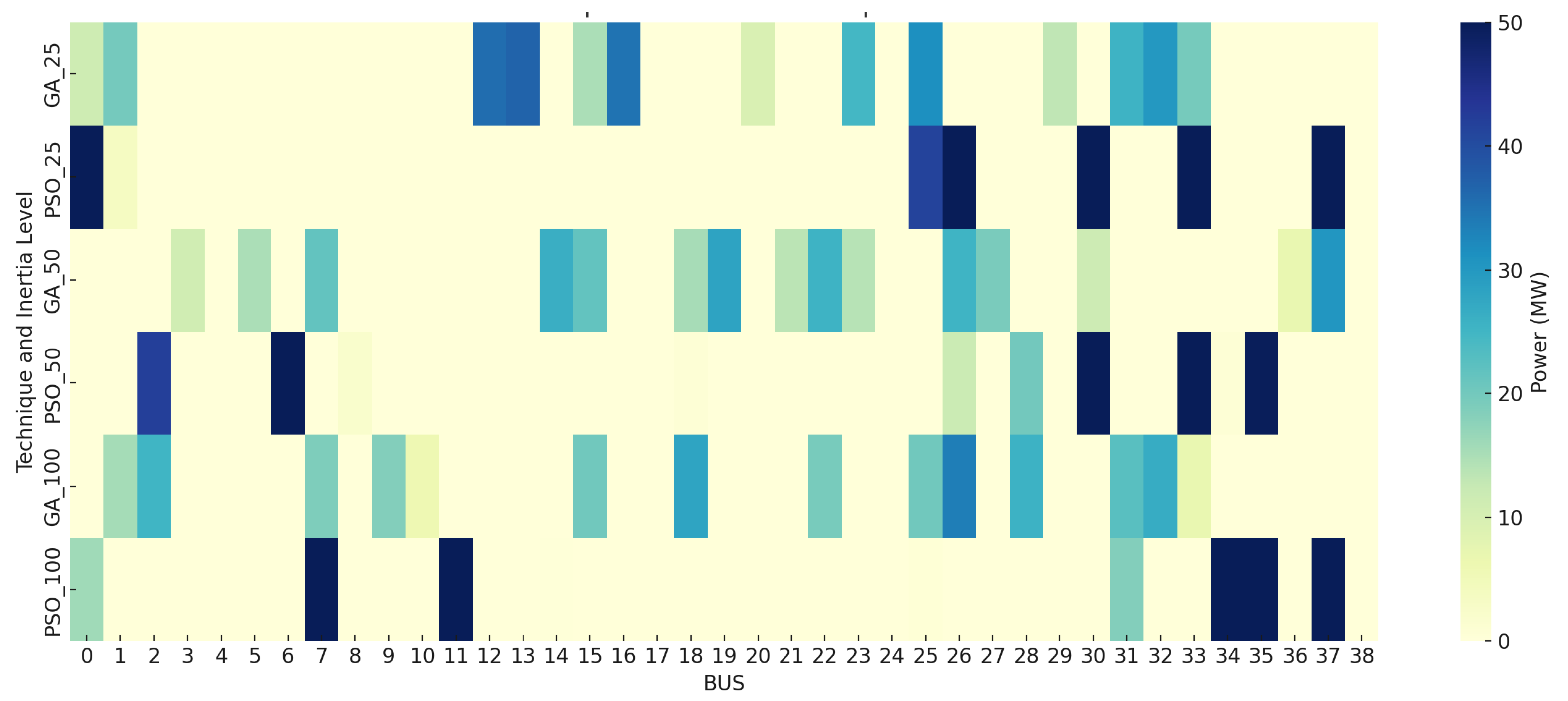

Section 4 presents the results obtained from applying GA and PSO to the optimization problem under various inertia scenarios.

Section 5 presents the discussion.

Section 5.5 presents limitations and implementation challenges.

Section 5.6 explains the practical implementation.

Section 5.7 explains the theoretical-practical integration. Finally,

Section 6 presents the conclusions of the study.

1.3. Need for Virtual Inertia in Power Systems

Traditionally, inertia in electric power systems has been directly dependent on rotating machines and on the electromagnetic coupling between their rotating masses and the electrical grid [

49]. With the integration of power electronic interfaces, a decoupling occurs between generators, rotating loads, and the grid, which prevents the kinetic energy stored in their rotating masses from mitigating transients in the system [

50]. As a result, it becomes necessary to define methodologies that enable the grid to maintain inertia levels

H such that the magnitude of frequency deviation is minimized during generation-load imbalances.

In this way, the system dynamics would exhibit a slower and more damped response, increasing the critical clearing times for fault removal and allowing sufficient margins to perform switching actions to counteract active power imbalances caused by faults or events such as the loss of transmission lines, generation units, loads, etc. [

50].

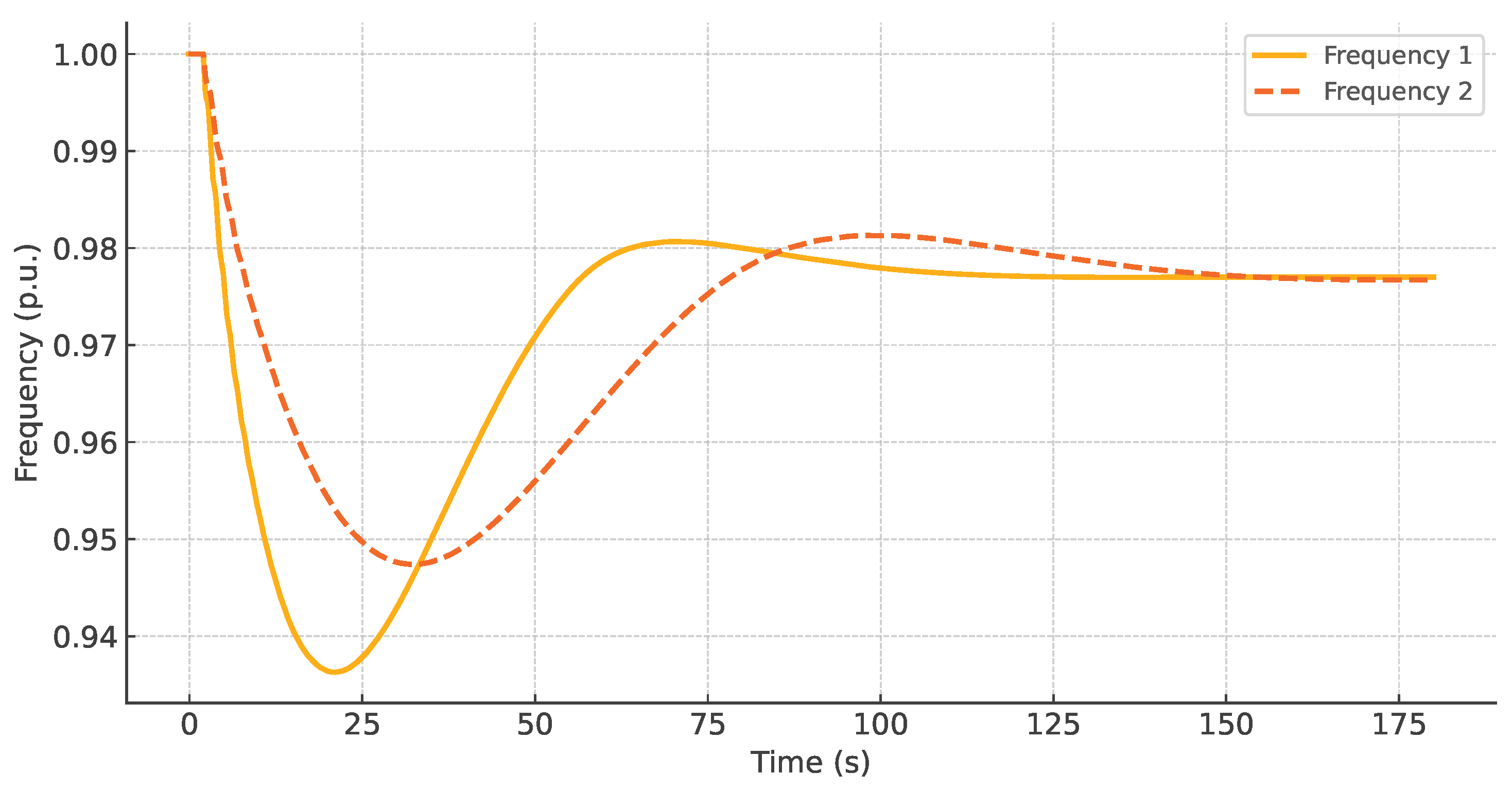

Figure 1 illustrates how frequency is affected by changes in system inertia levels. The curve labeled Frequency 1 corresponds to the IEEE 39-bus system with a 50% loss of inertia, while the curve labeled Frequency 2 represents the same system operating with 100% of its original inertia. A generation-load imbalance results in frequency excursions, and this imbalance is initially counteracted by the system’s inertia

, as expressed in Equation (

1), where the inertia

of each generator is defined in Equation (

2) [

50].

where

is the kinetic energy of the generator,

J the moment of inertia,

the total system power,

the nominal system frequency, and

the power of each generator.

The RoCoF is the instantaneous rate of change of frequency following an imbalance in the system caused by a disturbance. Generation loss, sudden load disconnection, and islanding operation are examples of such disturbances.

The initial

, assuming zero load damping [

50], is expressed as follows in Equation (

3):

where

is the size of the contingency (lost MW),

H is the system inertia (MW-seconds),

is the frequency at the time of the disturbance (Hz), and

is the rate of change of frequency (Hz/s).

A slow-response scenario for RoCoF, within the range of seconds to minutes, is associated with the inertia provided by synchronous generators along with their governors, which help to reduce the RoCoF. Enhancing grid inertia control within this physical time frame could be naturally achieved through the use of synchronous condensers. On the other hand, a fast-response scenario for RoCoF control could involve the rapid injection of energy, either by increasing generation or reducing load.

Inverter-Based Power Sources (IBPS), such as wind, solar, batteries, supercapacitors, and flywheels, can provide a fast frequency response. However, these devices inherently lack an inertial response, making a control loop that enables energy delivery proportional to changes in system speed or frequency necessary.

These limitations in the system’s inertial response motivate the review of inertia emulation techniques, which are presented in the following section.

1.5. Battery Energy Storage Systems

Figure 3 presents the BESS system architecture used in this analysis. It comprises a battery, a charge controller that ensures charging and discharging remain within defined boundaries, and measurement units tasked with tracking key electrical variables such as voltage, real and reactive power, and frequency. At the core of the control scheme is a PQ controller, which governs the flow of real and reactive power to and from the BESS [

43].

The regulation of active power is managed via the signal, while determines the reactive power. These references are transmitted to a PWM-based power converter through the charge controller, which facilitates the power exchange in accordance with the PQ controller’s commands.

The control system also incorporates a frequency control loop, designed to modify the active power reference delivered to the PQ controller in response to frequency deviations in the grid and a preset droop characteristic. This frequency regulation mechanism is depicted in

Figure 2. For the purposes of this work, the battery model assumes that its output voltage is a function of its SoC, internal resistance, and nominal capacity (Cbat). With battery capacity treated as a constant, the model follows a standard equation relating terminal voltage to SoC and battery current [

43].

where

represents the terminal voltage of the battery, while

denotes the State of Charge. The variable

I corresponds to the battery current, and

is the internal resistance. The maximum voltage,

, indicates the voltage level when the battery is fully charged, whereas

refers to the voltage when the battery is fully discharged.

Figure 3 illustrates the control architecture of a BESS, designed to regulate the injection of active and reactive power, as well as to participate in frequency control of an electrical grid. The system begins with the measurement of key electrical variables such as AC voltage (AC Voltage Measurement), active and reactive power (PQ Measurement), and system frequency (Frequency Measurement). The measured frequency feeds the frequency control block, which compares the measured frequency with a reference and generates an active power adjustment signal (

). This signal, along with the voltage and power measurements, is processed by the power controller (PQ Control), which calculates the required active (

) and reactive (

) current references for the operation of the BESS.

Simultaneously, the battery model provides internal information about the storage system, including cell voltage (), cell current (), and state of charge (SOC). These parameters are used by the charge controller (Charge Controller), which integrates the current references and the battery conditions to generate efficient operating commands. Finally, these references are sent to the PWM converter, which regulates the BESS energy output to the electrical grid.

The diagram in

Figure 4 presents the control scheme designed to emulate inertia in a BESS, contributing to frequency support in the electrical grid. The system receives the measured frequency signal

as input, from which the time derivative

is calculated using a differentiator block weighted by a gain

K. This signal represents the RoCoF, a critical variable under contingency conditions. To mitigate the effect of potential high-frequency noise, the derivative signal is processed through a first-order filter with gain

and time constant

T, thereby obtaining the signal

, which provides a smoothed estimate of the RoCoF.

The output of the filter is subsequently amplified by a gain

, generating a proportional signal that represents the synthetic inertial response power to be delivered by the BESS. In parallel, the measured frequency signal is also used to calculate the deviation from its nominal value, scaled by a gain

, enabling a control action proportional to the frequency error. Both signals—the one corresponding to the RoCoF and the one for frequency error—are combined along with a compensation constant

, ultimately generating the active power reference signal

. This reference is used to control the power that the BESS must inject or absorb, thereby emulating the effect of inertia. The gains have been set manually, and their values are presented in

Table 2.

As the battery supplies energy to the grid, the

SoC value decreases. The

SoC under discharge conditions can be estimated using Equation (

9):

where

is the state of charge of the battery at time

t,

is the initial state of charge expressed as a percentage,

I is the measured charge/discharge current in amperes (A),

t is the time measured in seconds (s), and

is the battery capacity in ampere-hours (Ah).

With the BESS model defined, the next step is to structure the optimization methodology that will enable the assessment of its optimal placement and sizing within the power system.