1. Introduction

The stability and operational reliability of a power system depend heavily on the performance and integrity of its transmission network. Any disruption within transmission lines can significantly affect the continuity of the electrical supply, potentially leading to widespread blackouts and economic losses. These transmission lines, while essential, are prone to various types of short-circuit faults, both symmetrical and asymmetrical, which threaten the secure delivery of electrical energy across the grid [

1]. Such faults often arise from natural hazards such as storms or lightning, insulation failures, equipment failures, or human error, all of which require immediate attention to prevent prolonged outages and equipment damage [

2].

As modern power grids evolve with the integration of distributed energy resources (DERs), automation systems, and wide-area monitoring technologies, the need for accurate and real-time fault diagnosis has become increasingly critical [

3,

4]. The effectiveness of fault identification and classification depends largely on the quality and diversity of the underlying dataset. In practice, data sets must encompass a wide array of operational scenarios, including different loading conditions, types of fault, resistance levels, and system topologies. Without capturing such variability, diagnostic models may fail to generalize when deployed in actual grid environments. Therefore, developing realistic and comprehensive datasets that closely reflect practical network behavior is fundamental to advancing fault diagnosis capabilities in contemporary power systems.

Despite notable advancements in the application of machine learning and deep learning for power system fault analysis, many existing studies suffer from a lack of realistic data representation. Several works rely on public or simplified data sets that often exclude critical parameters such as fluctuating active/reactive power flows, unbalanced operating conditions, and variable fault resistances [

5,

6,

7]. Moreover, a significant number of approaches address fault classification and location identification as separate problems, each requiring independent models or sequential processing pipelines [

5,

8]. While effective in controlled settings, these methods introduce computational inefficiencies and hinder scalability for real-time grid monitoring applications.

This research addresses the above limitations by advocating for an integrated approach. A unified framework capable of simultaneously detecting faults, classifying their types, and estimating their locations not only reduces computational overhead but also improves consistency and responsiveness. To make such a model reliable, it must be trained on data that realistically captures fault behavior across a broad spectrum of grid conditions. This motivation drives the need for an advanced model architecture and a robust dataset reflecting real-world network dynamics.

In this paper, we introduce a novel deep learning framework that unifies three essential tasks, fault detection, fault type classification, and fault location identification, into a single cohesive model. This multi-task learning (MTL) model, referred to as MTL-AttentionNet, is designed to enhance both performance and efficiency in power system fault analysis. The key contributions are:

Dataset generation: A comprehensive dataset is generated using the IEEE 39–Bus transmission system in DIgSILENT PowerFactory, incorporating diverse fault scenarios, probabilistic load variations (), a wide range of fault resistances (0–50 ), and spatially distributed fault locations (10% to 90% of line length). This realistic simulation setup captures the stochastic behavior of power systems and provides a robust foundation for developing and evaluating fault diagnosis models under practical grid conditions.

Unified multi-task framework: We propose a multi-task deep learning framework for end-to-end fault diagnosis in power systems, simultaneously addressing fault detection, classification, and location. The model integrates shared hierarchical feature extraction with task-specific adaptive branches, explicitly leveraging cross-task dependencies to enhance diagnostic accuracy and computational efficiency.

Raw signal-based feature learning: Unlike traditional ML approaches that depend on manual feature engineering, our framework leverages raw three-phase voltage and current samples from a single post-fault instant for fault diagnosis. This eliminates the need for complex signal processing or high-frequency time-series inputs, streamlining the modeling process and enhancing computational efficiency without sacrificing diagnostic accuracy.

Comprehensive benchmarking: We benchmark the proposed MTL-AttentionNet against state-of-the-art methods and baselines, including Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). Across detection, classification, and location, the framework consistently outperforms these baselines, demonstrating robustness, superior diagnostic accuracy, and adaptability in diverse fault scenarios and network conditions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews existing research related to fault diagnosis in power systems.

Section 3 outlines the fault scenario simulation and dataset development process using the IEEE 39–Bus system.

Section 4 introduces the MTL methodology and the formulation of the model.

Section 5 presents the proposed attention-enhanced MTL framework, including architectural design and feature engineering.

Section 6 reports experimental results, performance evaluation, and comparative analysis with baseline models. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes the key contributions and concludes the study.

2. Review of Existing Works

A broad spectrum of fault diagnosis methods has been explored in transmission and distribution networks, each offering unique advantages and encountering specific limitations. Conventional techniques often rely on impedance-based estimation or traveling-wave analysis to detect and classify faults [

9,

10].

Although traveling-wave-based approaches can be accurate for high-resistance faults, they typically require higher sampling rates, fast data synchronization, and advanced communication infrastructure factors that can pose practical challenges [

9,

11]. Impedance-based methods, on the other hand, are comparatively straightforward but may become less accurate in the presence of high fault impedances or complex lateral branches [

12,

13]. Wavelet transform-based solutions have also gained traction by effectively capturing and analyzing transient fault signals across multiple frequency bands; however, their computational load can become significant, especially when dealing with large-scale systems or higher decomposition levels [

14,

15,

16]. Knowledge-based and expert system approaches have been proposed to leverage heuristic rules and historical data, but their robustness diminishes if the system deviates from previously observed operating conditions [

17].

Over time, the increasing accessibility of higher-fidelity data, enabled by intelligent electronic devices, phasor measurement units (PMUs), and real-time digital simulators, has led to a surge in data-centric methods for fault diagnosis [

4,

18,

19]. Researchers have begun integrating machine learning (ML) algorithms such as support vector machines (SVMs), artificial neural networks (ANNs), and deep learning architectures to classify and localize faults efficiently. In many cases, these ML-based methods demonstrate impressive classification accuracies exceeding 95%, with some even approaching or surpassing 99% [

5,

20,

21]. However, their reliance on either specialized hardware (e.g., PMUs) [

5,

6] or computationally intensive hybrid feature extraction has limited their adoption in broader, real-world settings [

5,

22]. Moreover, several studies emphasize that although deep learning models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or hybrid CNN-LSTM techniques achieve high accuracy for fault classification, they often either do not tackle fault location or address it with limited precision [

8,

23,

24,

25]. In addition, the training datasets in some of these studies originate from relatively small or simplified networks, thus raising questions about scalability and real-world applicability [

20,

26,

27].

Another common limitation is the discrepancy between simulation-heavy datasets and practical field conditions. Although certain works incorporate noise or data augmentation to mimic real scenarios [

18,

25,

28], many still fall short in accounting for the full complexity of large-scale networks with varying load demand, and uncertain fault resistance [

25,

29,

30]. Even when advanced ML models, such as explainable CNNs or spatiotemporal graph networks, are developed for fault classification and localization, they often demand substantial computational resources or extensive instrumentation to achieve their reported accuracy [

18,

30]. Likewise, approaches using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems often outperform standard neural networks but at the cost of higher computational overhead, making real-time deployment challenging [

20]. These constraints highlight the necessity for more efficient, scalable, and data-driven solutions that address both fault classification and precise fault location under realistic, large-scale operating conditions.

In recent years, multi-task learning (MTL) has also gained momentum in various power system applications, leveraging the interrelatedness of multiple tasks to enhance overall performance. For instance, an MTL-based framework employing a logistic low-ranked dirty model has been proposed for fault detection in PMU data, enabling improvements by exploiting shared features among different network locations [

31]. In the context of smart grids, MTL has further been adopted for building load forecasting, where predicting both load and temperature simultaneously yields superior predictive accuracy compared to single-task approaches [

32]. These advances highlight the versatility of MTL in addressing complex, high-dimensional power system problems. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, no existing study applies MTL for fault identification, type classification, and location within a unified framework, despite the potential benefits of jointly optimizing these interconnected tasks in large-scale and dynamic networks.

3. Fault Scenario Simulation and Dataset Development

3.1. IEEE 39–Bus System Setup and Load Variation

The IEEE 39–Bus test system, depicted in

Figure 1, was selected as the reference network for fault simulation due to its realistic complexity and widespread use in transmission system studies [

33]. The system comprises multiple generators, transformers, and loads interconnected through transmission lines, offering a dynamic environment for modeling fault scenarios across diverse operational conditions.

Fault simulations were performed using DIgSILENT PowerFactory operating in engine mode, coupled with automated Python (v3.7) scripts. This integration enabled systematic variation in load conditions, fault injection, simulation control, and data extraction in an efficient and reproducible manner. To reflect real-world grid variability, active (P) and reactive (Q) loads at each bus were probabilistically perturbed using a normal distribution with a standard deviation of approximately around their nominal values. This approach ensured that the network remained operationally feasible while exhibiting realistic operating point fluctuations.

3.2. Fault Scenario Configuration and Data Generation

Fault scenarios were comprehensively designed to include typical conditions encountered in practical power systems, encompassing single-phase-to-ground faults, two-phase faults, two-phase-to-ground faults, three-phase-to-ground faults, and no-fault conditions. For each transmission line in the IEEE 39–bus network, these fault types were simulated at multiple points along the line, covering fault locations from 10% to 90% of the line length. To capture the effects of varying fault severities, fault resistances were randomized between 0 and 50 across different scenarios. Each case was labeled with its corresponding fault type and location class, and, over all iterations, the procedure covered faults and healthy conditions on all transmission lines of the IEEE 39–bus system.

A total of 86,676 samples were generated, covering both faulted and healthy conditions under diverse operating scenarios. The complete distribution of fault types and sample counts is summarized in

Table 1, providing a balanced dataset for robust machine learning model development.

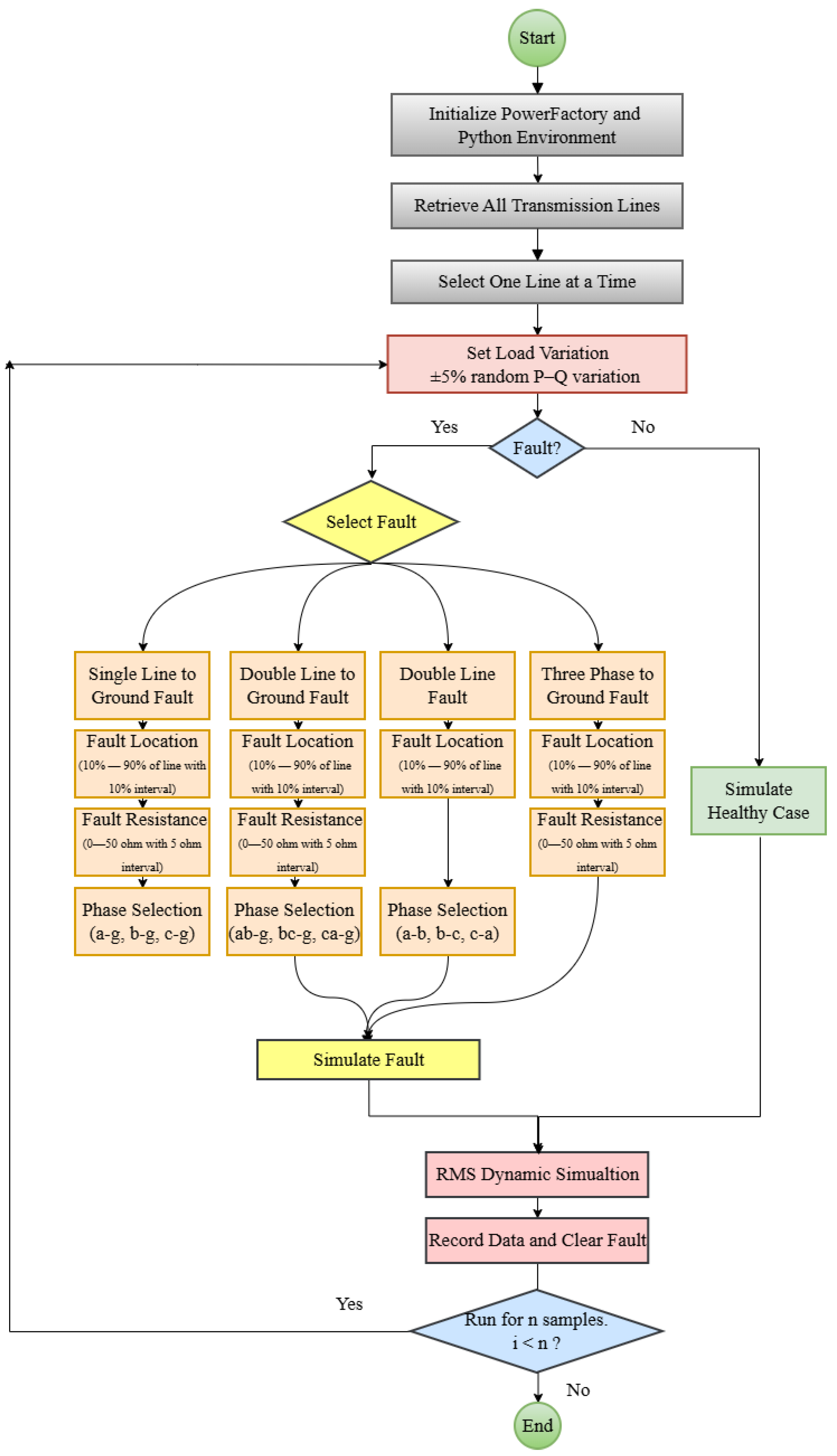

As shown in

Figure 2, the training dataset is generated through an automated co-simulation loop between DIgSILENT PowerFactory and Python. The script first initializes the PowerFactory environment, retrieves the list of all transmission lines, and in each iteration selects one line while perturbing the bus loads around their nominal values using the probabilistic

P–Q variation described in

Section 3.1. Each RMS dynamic simulation is executed over a fixed time window with identical start and end times for all scenarios. Within this window, the fault (when present) is always applied at the same instant under the selected operating condition. The routine then decides whether to simulate a faulted or healthy (no-fault) operating condition. For faulted cases, the algorithm gradually selects the fault type (SLG, LL, LLG, or three-phase-to-ground), the affected phase(s), the fault location along the line (10–90% of the line length), and the fault resistance (0–50

) for each line. An RMS simulation is executed for the selected scenario, and data from both ends of the line are recorded to form one labeled sample comprising the electrical measurements and the associated fault/no-fault label, fault type, and location class. This process is repeated for all transmission lines and across multiple operating conditions until the full dataset of 86,676 samples is obtained.

For each simulated case, the input feature set consists of electrical measurements obtained from both terminal buses of the selected transmission line. Specifically, the model uses the three-phase voltages and three-phase line currents (magnitudes and phase angles) recorded at the two line ends. These features capture phase-wise asymmetries and magnitude variations essential for fault identification and fault type classification. For the fault location task, the shared features are enhanced with line-level contextual information, including an encoded line identifier, the symmetrical-component voltages (positive, negative, and zero sequence) at both line ends, and the phase-angle measurements of the three-phase voltages. This results in a compact but informative feature representation tailored to each task within the MTL framework.

5. Proposed Model

5.1. Overall Architecture of the Proposed Framework

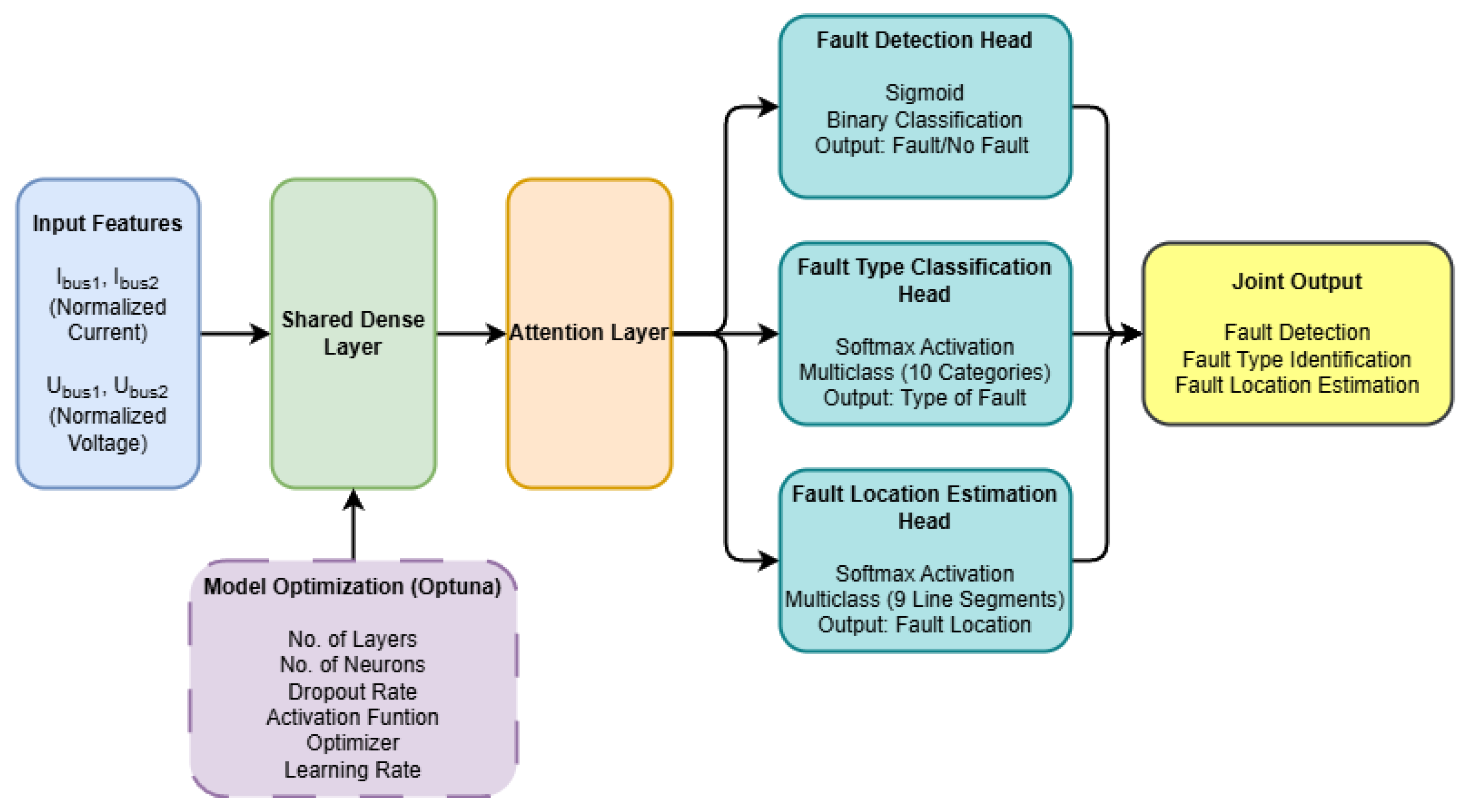

The proposed framework is designed to simultaneously address three critical tasks in transmission line fault diagnosis: fault identification, fault type classification, and fault location estimation. This integrated approach is rooted in the principles of multi-task learning (MTL), which facilitates shared feature representation while allowing task-specific outputs.

At the core of the model lies a shared representation module that processes fundamental electrical measurements, including three-phase currents and bus voltages. These shared features capture essential dynamics of the power system and serve as the input to an initial stack of dense layers, followed by dropout regularization. This part of the network is responsible for learning general patterns associated with power system behavior under various conditions, including healthy states and fault events. To further refine feature relevance, an attention mechanism is introduced after the shared dense layers. This mechanism assigns adaptive weights to different input features based on their contextual importance, enabling the model to emphasize measurements that are most indicative of fault presence, type, or location.

Following the attention-enhanced representation, the network branches into three task-specific output layers:

A binary classification head using a sigmoid activation function to determine whether a fault has occurred.

A multi-class softmax classifier for identifying the specific type of fault.

A second multi-class softmax classifier for estimating the location of the fault along the affected transmission line, expressed as discrete segments (e.g., 10% to 90% of line length).

This architecture allows shared learning of common fault features while preserving the flexibility to handle the unique demands of each task. By jointly modeling these tasks, the network benefits from shared gradient flows, where improvements in one task can positively influence the learning of another. This synergy not only boosts overall model performance but also facilitates practical deployment in real-time environments by eliminating the need for separate models for each diagnostic stage. The complete architecture is illustrated in

Figure 4, highlighting the flow of information from shared input layers to task-specific outputs.

5.2. Task Formulation

Effective feature selection is critical in building robust machine learning models, particularly when the goal is to simultaneously address multiple tasks. In this study, fault identification, fault type classification, and fault location estimation are formulated as three interrelated tasks, each drawing from a common pool of electrical measurements while also benefiting from task-specific information.

The shared encoder receives the three-phase voltage and current measurements from both line ends, while the location head additionally incorporates the encoded line identifier and sequence-component and phase-angle features to resolve spatially close fault locations.

Fault Identification relies on global indicators that differentiate healthy and faulty states. Key features include sudden changes in current magnitude or significant deviations in voltages, which signal the presence of a disturbance in the system.

Fault Type Classification relies on phase-wise differences in the measured quantities. The model receives the three-phase voltages and line currents at both ends of the selected line, which encode how each fault type distorts the balance between phases. For example, single-line-to-ground faults mainly affect one phase and its corresponding return current, whereas double-line and three-phase faults produce more symmetric but higher-magnitude changes across multiple phases. By learning patterns in inter-phase magnitude ratios and angle differences at the two line ends, the shared representation can reliably distinguish among the ten fault categories.

Fault Location Estimation additionally depends on line-specific contextual information. In this task, the shared electrical features are augmented with auxiliary inputs, including the encoded line identifier and the fault-type label, so that the model knows on which transmission line the event occurs and what kind of disturbance is present. This extra context helps disambiguate spatially adjacent locations that may exhibit very similar voltage and current signatures, enabling the location head to refine its prediction among the nine distance classes along the faulted line.

Thus, the shared feature set provides a common representation of the instantaneous electrical state, while each task head exploits a different subset of these signals and contextual variables tailored to its diagnostic goal.

5.3. Attention Mechanism

In the proposed MTL-AttentionNet, attention is applied on top of the shared latent representation rather than directly on the raw voltages and currents. Let denote the output of the shared dense layer (with units in this work), which represents nonlinear combinations of the original measurements at both ends of the line. To account for the fact that not all latent dimensions contribute equally to fault diagnosis, we employ a feature-wise (channel) attention mechanism with a single attention head.

The attention module first computes an intermediate score vector

where

and

are learnable parameters. These scores are then normalized using the softmax function to obtain attention coefficients

which satisfy

and

. The attended shared representation is obtained by element-wise reweighting,

and

is subsequently fed to the three task-specific heads for fault detection, fault type classification, and fault location estimation. This design corresponds to a single-head, feature-wise attention layer (channel attention) acting on a static feature vector.

From a power-system perspective, each component of captures a latent pattern constructed from the underlying features (e.g., phase imbalances, asymmetries between line terminals, or magnitude/angle combinations). The attention layer learns which of these latent patterns are most informative for the diagnosis tasks and amplifies them, while suppressing less relevant dimensions. In this way, the attention module acts as a learned feature-selection or gating mechanism on top of the shared representation.

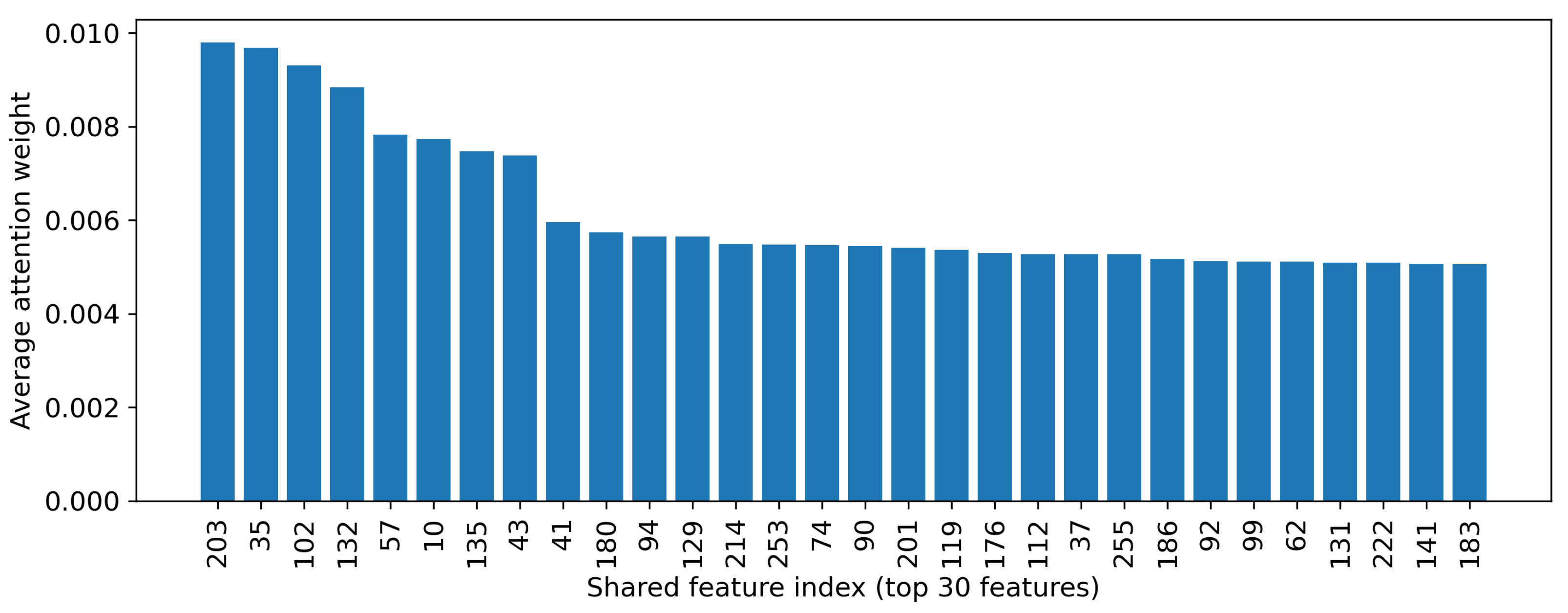

To analyze the behavior of the attention mechanism, we examined the attention coefficients on the test set.

Figure 5 illustrates the average attention weights of the shared latent features, sorted by importance, and highlights the top 30 dimensions. The distribution is clearly non-uniform: a relatively small subset of latent features receives higher attention weights, whereas many dimensions are assigned near-zero values. This indicates that the attention module concentrates the model’s capacity on a compact set of informative latent features derived from the measured voltages and currents, rather than treating all dimensions equally.

5.4. Hyperparameter Tuning with Optuna

Model optimization was performed using Optuna, an automated framework for hyperparameter tuning. Key parameters—such as hidden layer count, neuron size, dropout rate, activation type, and learning rate—were systematically explored within predefined ranges to identify the most effective configuration.

In each trial, Optuna instantiated an attention-based MTL model with sampled hyperparameters and evaluated its performance using the aggregated validation loss across fault detection, classification, and location tasks. This multi-objective approach ensured balanced optimization across all outputs.

Using adaptive sampling and early stopping, Optuna efficiently converged to an optimal configuration, minimizing manual intervention. The best-performing model, retrained on the full dataset, achieved the lowest validation loss and demonstrated strong generalization for complex fault diagnosis scenarios. The final configuration is presented in

Table 2.

6. Results and Performance

6.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

The experimental evaluation was conducted using a dataset comprising labeled transmission line scenarios, encompassing both normal operating states and various fault conditions. To ensure reliable model training and performance assessment, the dataset was divided into three distinct subsets: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. This division was performed in a two-step procedure: initially separating the training portion from a 30% holdout set, and subsequently dividing the holdout set equally into validation and test sets.

Model training and evaluation were carried out on a Windows 64-bit platform equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-8750H CPU (2.20 GHz), 16 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060 GPU with 6 GB GDDR6 memory. The implementation used TensorFlow 2.x with Keras for model development, while Optuna was used to automate hyperparameter optimization.

To assess the model’s performance in fault detection, type classification, and location estimation, standard classification metrics were employed. These included accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, and F1-score, which are particularly useful in the presence of class imbalance. Confusion matrices were additionally examined to evaluate the distribution of correct and incorrect predictions across classes. Definitions and mathematical formulations of the evaluation metrics are presented in

Table 3.

6.2. Fault Detection Results

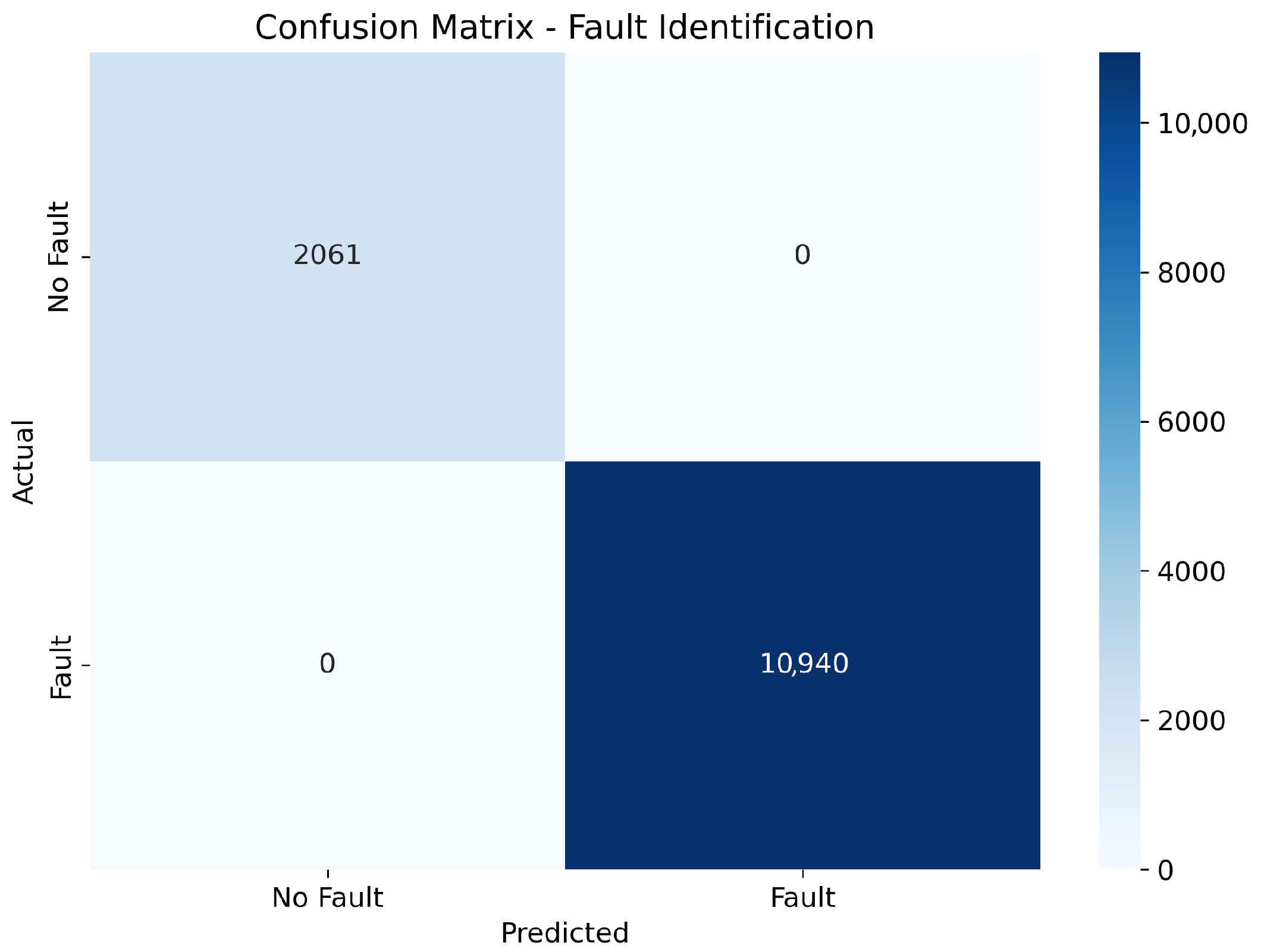

The proposed MTL framework demonstrated excellent fault detection capability, reliably distinguishing between normal and faulty conditions. Treated as a binary classification problem, this task leveraged shared features comprising three-phase voltages and currents from both line ends, serving as the initial stage of the hierarchical fault analysis.

The model achieved an overall accuracy of 100% in fault identification. The confusion matrix (

Figure 6) confirms perfect classification, with no false positives or false negatives recorded. Precision, recall, and F1-score values of 1.000 across both classes further highlight the model’s robustness and generalization ability.

6.3. Fault Type Classification Performance

The second task in the proposed MTL framework addresses fault type classification, formulated as a ten-class problem encompassing various fault scenarios, including single-phase-to-ground, two-phase, two-phase-to-ground, and three-phase-to-ground faults. Utilizing the shared representations extracted during fault detection, the model refines its decision boundaries to accurately assign each detected fault to its corresponding class.

The confusion matrix in

Figure 7 confirms the high reliability of the classification task, with only minor confusion between neighboring fault types. The numeric class indices (0–10) in this figure follow the fault category mapping given in

Table 1. Notably, A-B phase-to-ground faults exhibit slight misclassification with other line-to-ground faults, attributed to inherent similarities.

Class-wise performance metrics summarized in

Table 4 reveal consistently high precision, recall, and specificity across all categories. Several fault types, including B-phase-to-ground, B-C-phase-to-ground, and three-phase-to-ground faults, achieved perfect scores across all evaluation metrics. Slightly lower, though still excellent, performance was observed for A-B and C-A phase faults, likely due to waveform overlaps in high-resistance or partial-load conditions. The weighted average F1-score reached 0.9998, demonstrating the robustness of the model even under complex and overlapping fault scenarios.

6.4. Fault Location Identification

The final task within the proposed MTL framework addresses fault localization along transmission lines, formulated as a multi-class classification problem across nine location classes (from 10% to 90% of line length). The model leverages shared features such as three-phase voltages and currents, along with task-specific inputs including line identifiers and fault types, emulating real-world hierarchical protection schemes.

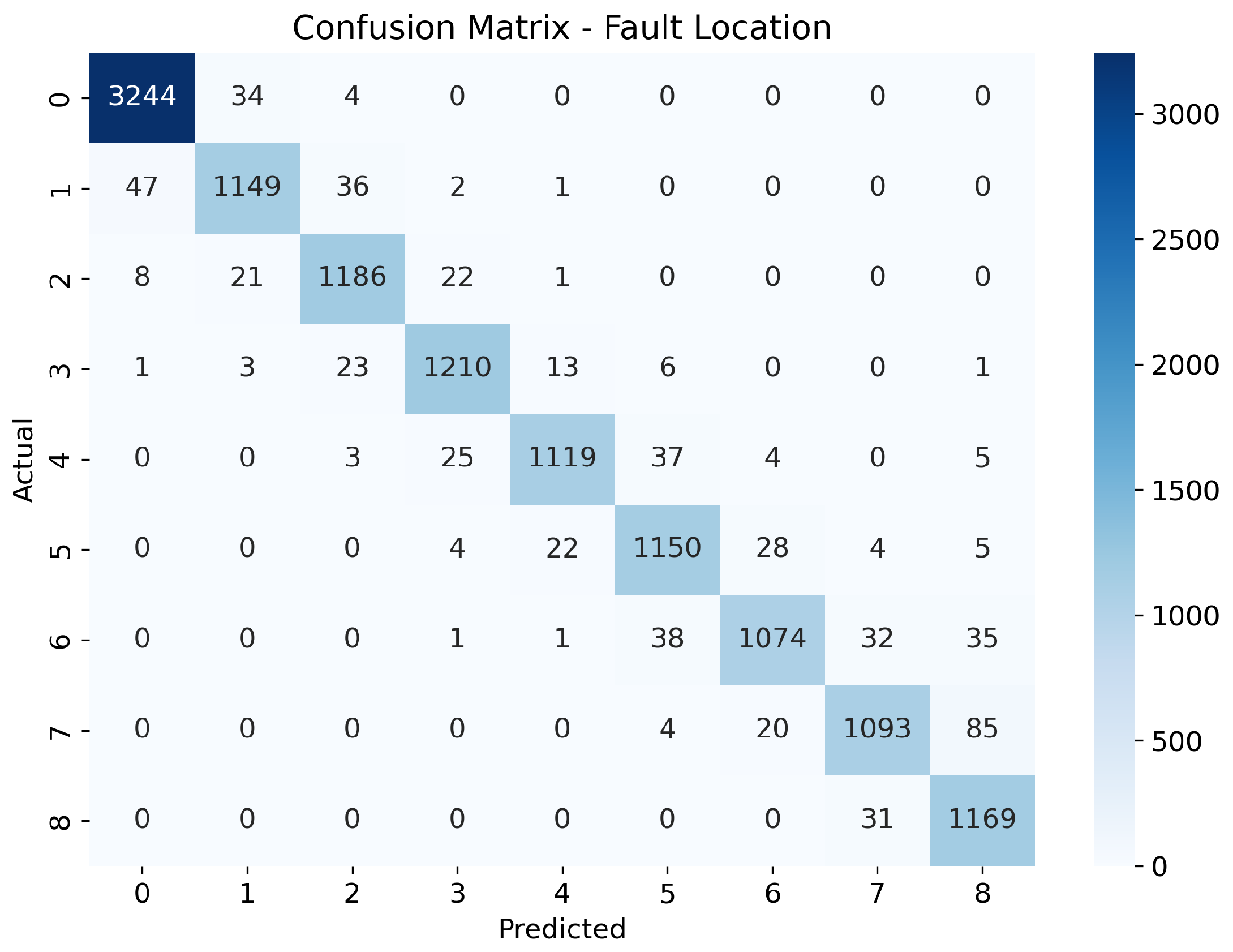

The confusion matrix in

Figure 8 demonstrates that most faults are accurately classified, with only minor confusion between neighboring segments, as expected due to gradual electrical transitions along lines. The model achieves an overall fault location accuracy of 98.82%, as summarized in

Table 5. Higher F1-scores are observed for locations nearer to the sending end (e.g., 10%, 30%, and 40% segments), while marginally lower performance occurs toward the receiving end (e.g., 80% and 90%), where signal attenuation and reflections increase. A closer inspection of the 154 misclassified samples from 13,001 test samples shows that they are predominantly associated with higher fault resistances (e.g.,

) near these end segments, where the RMS voltage and current patterns of adjacent location classes become particularly similar.

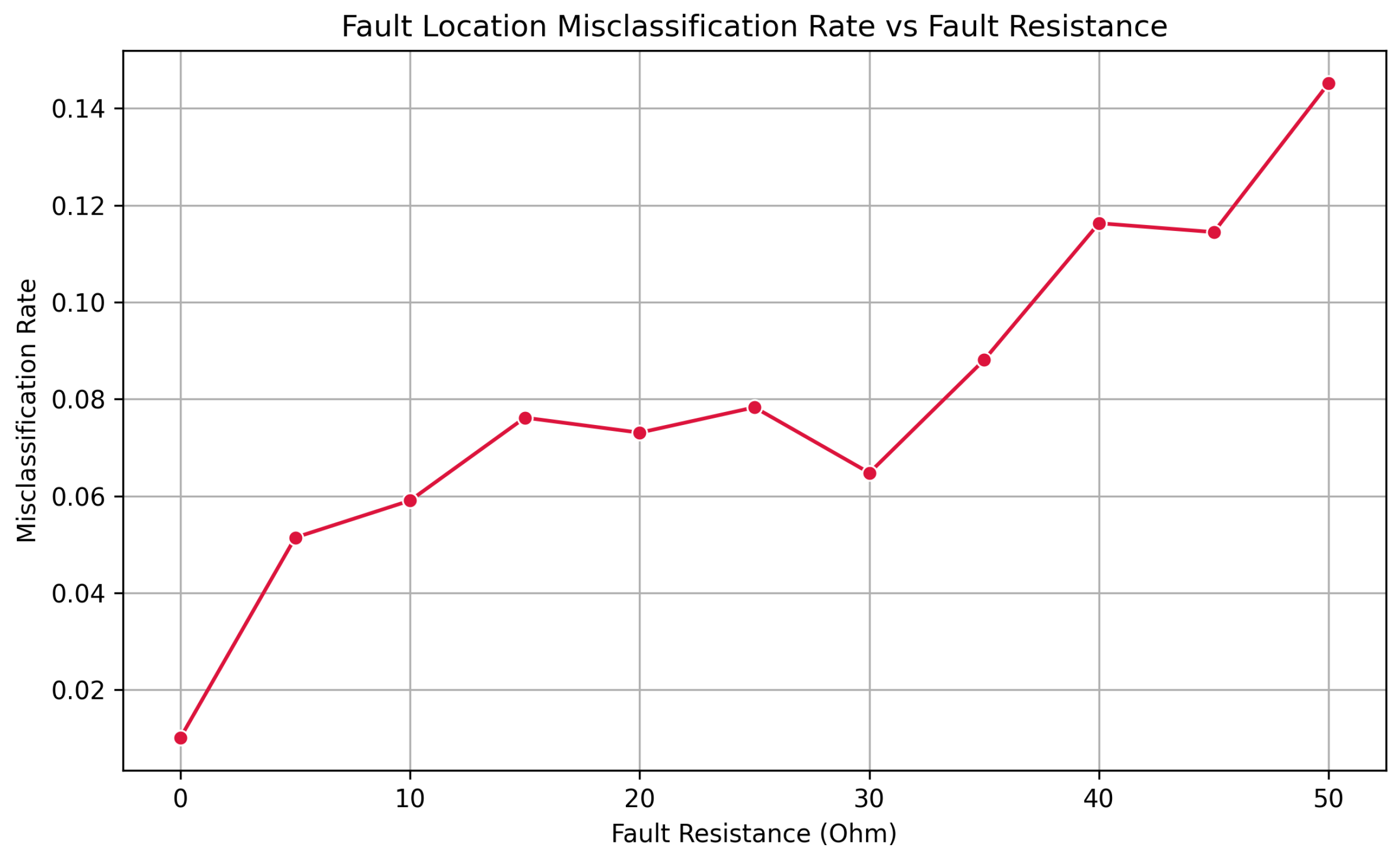

An additional evaluation of fault resistance impact is illustrated in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. Location accuracy remains near perfect for faults with low resistance but gradually declines as resistance exceeds 30

. This degradation, typical in protective relaying, results from weaker fault signatures at high resistances, underscoring the challenge of detecting high-impedance faults under noisy conditions.

Despite these variations, the proposed MTL model maintains strong localization capability, suggesting its practical utility for real-time fault isolation and system protection.

6.5. Comparative Analysis

Recent studies in fault classification and location have explored a wide range of ML and DL architectures with impressive reported accuracy, though system configurations and evaluation setups vary widely. For instance, Nawaz et al. [

18] implemented eight classical ML models on a three-terminal 735 kV line and used 12,350 simulated faults generated in Simulink. Their best-performing model, Logistic Regression, achieved 99.97% classification accuracy, though fault location was not addressed. In another study, Fang et al. [

30] proposed a multitask CNN trained on 20 kHz-sampled voltage and current waveforms from a 200 km, 220 kV line. Their model achieved 99.85% classification accuracy and 98.02% location accuracy. However, the reliance on high-resolution pre- and post-fault time-series data from a single-circuit TL model limits the generalizability and real-time applicability of the approach, as such high sampling rates are costly in both computation and data collection.

Other notable works have employed a variety of network types and features, generally balancing between accuracy and practical complexity. Onaolapo et al. [

35] used MLP-ANN models on a 400 kV, 29-bus GB system, leveraging windowed V/I ratios across fault stages and attaining 1% to 3% location error based on fault type. Belagoune et al. [

36] adopted multitask LSTMs on the Kundur 4-Machine Two-Area system with 84-dimensional phasor inputs, reaching classification accuracy of 99.93%. Chen et al. [

37] employed a convolutional sparse autoencoder trained on half-cycle waveform data from a high-voltage TL and reported 99.74% accuracy in fault classification.

In contrast, our proposed MTL-AttentionNet delivers a competitive performance of 99.99% fault classification accuracy and 98.82% fault location accuracy on the complex IEEE 39-bus system. The model processes only single-sampled post-fault data and leverages a unified multitask architecture with shared feature extraction and task-specific branches. This design reduces dependency on dense time-series data, improving scalability for real-time applications. A comparison with existing singular task-based models is provided in

Table 6.

To provide additional perspective, two baseline algorithms, SVM and MLP, were evaluated under identical dataset conditions and task formulations, with their architectures and hyperparameters tuned on the validation set to provide competitive baselines. As shown in

Table 7, the MLP achieved a fault classification accuracy of 99.98%, closely approaching that of the proposed MTL-AttentionNet. However, its performance on fault location estimation dropped to 94.52%. SVM underperformed across all tasks, with a notably low location estimation accuracy of 84.47%.

In general, while previous work exhibits high performance under specific conditions, many are constrained by the complexity of their feature engineering pipelines, system configurations, or data requirements. The proposed MTL-AttentionNet addresses these limitations through the inclusion of probabilistic load variations and a wide range of fault resistances to strengthen the applicability of the model to real-world fault analysis.

6.6. Statistical Robustness and Practical Considerations

To assess the robustness of the proposed MTL-AttentionNet beyond a single training run, a stability analysis was performed over

independent runs with different random seeds. For each run, the model was trained on the same train/validation splits and evaluated on the held-out test set (

= 13,001 samples). The resulting test accuracies were then summarized by their mean and standard deviation across the five runs. As reported in

Table 8, all three tasks exhibit consistently high performance, with fault identification and fault type classification showing negligible variability across runs and fault location estimation maintaining a high mean accuracy with low variance. Specifically, the mean ± standard deviation of test accuracy over the five runs is

% for fault identification,

% for fault type classification, and

% for fault location estimation.

In addition, we report 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the test-set accuracies of the final selected model, computed using a binomial proportion model with

= 13,001 test samples. The resulting accuracies and 95% CIs are

% (CI:

%) for fault identification,

% (CI:

%) for fault type classification, and

% (CI:

%) for fault location estimation (

Table 8). The narrow confidence intervals and small standard deviations reflect both the large size of the test set and the stability of the optimization process, indicating that the reported performance is statistically robust and not the result of a single favourable initialization.

From an implementation perspective, the proposed MTL-AttentionNet contains 173,845 trainable parameters, corresponding to approximately MB of weights in 32-bit floating-point representation. To obtain an indicative measure of computational cost, the average inference latency for a single forward pass was evaluated on a CPU-only environment (no GPU acceleration). On this experimental setup, the mean inference time per sample was approximately 61 ms over 500 repeated predictions. While these numbers are hardware-dependent and may vary across platforms, they suggest that the model has a modest memory footprint and an inference latency that is compatible with practical deployment in digital substations or dedicated embedded controllers, especially when implemented on modern industrial hardware or optimized with standard edge-inference tools.

6.7. Discussion, Limitations, and Future Work

The results in

Section 6.5 show that the proposed MTL-AttentionNet can accurately diagnose faults across three complementary tasks using a single unified architecture. Fault detection and fault type classification both achieve near-perfect accuracy, while fault location estimation attains high performance even for high-resistance faults and different line lengths. The attention analysis further indicates that the model concentrates on a small subset of latent features derived from the three-phase voltages and currents, suggesting that the attention layer effectively acts as a data-driven feature selection and gating mechanism within the shared representation.

Despite these strengths, several assumptions constrain the current scope. First, each sample is constructed from a single post-fault RMS snapshot of three-phase voltages and currents at the two line terminals, taken at a fixed instant after fault inception and before clearing. This phasor-based view is consistent with PMU/IED protection, but it does not explicitly exploit temporal dynamics, which may be important for the most challenging location cases on long lines and under very high fault resistance. Second, the framework assumes three-phase measurements at both ends of each line, as provided in modern digital substations; long-distance lines with only single-end measurements would require retraining on one-terminal features or additional estimation steps.

These aspects suggest several directions for future work. Extending the architecture to sequence models that process short time windows of phasor or waveform data, adapting the framework to single-end measurement scenarios, and adding further deep-learning and capacity-matched single-task baselines on the same dataset would provide a more comprehensive assessment of multi-task learning benefits. In addition, validating the approach on other benchmark networks and, ultimately, on field PMU data will be important to confirm its robustness and practical applicability in real transmission systems.

7. Conclusions

This study proposed a unified deep learning framework based on multi-task learning (MTL) for fault diagnosis in power transmission systems. The MTL-AttentionNet model integrates shared feature representations, task-specific branches, and an attention mechanism to capture both global and task-specific fault characteristics, enhancing prediction accuracy and model robustness.

Experimental evaluations demonstrated that the proposed model achieves high accuracy in fault detection and fault type classification, while maintaining strong performance in fault location estimation, even under challenging conditions such as high-resistance faults. Comparative analysis with benchmark machine learning and deep learning methods further confirmed the superiority of the proposed model in diagnostic precision.

By consolidating three critical diagnostic tasks into a single architecture, the MTL-AttentionNet framework demonstrates practical efficiency and reduced system complexity for PMU-like transmission-grid data. While the present study focuses on the IEEE 39-bus network, the diverse training scenarios, incorporating varying load conditions, line lengths, fault resistances, and fault locations, indicate that the approach is well-suited for extension to other networks. In future work, we plan to validate the framework on additional benchmark systems and field PMU datasets, and to investigate real-time implementations for intelligent substation automation, grid monitoring, and smart grid resilience applications.